The European University Spinout Boom That's Reshaping Venture Capital

There's something happening in Europe's university labs that venture capitalists can't ignore anymore. While everyone obsesses over AI in Silicon Valley, European researchers are building deep tech companies that solve real, complex problems, and investors are finally paying attention.

In 2025, something shifted. Not just incrementally, but meaningfully. According to recent data from TechCrunch, 76 university-born companies from across Europe have either hit

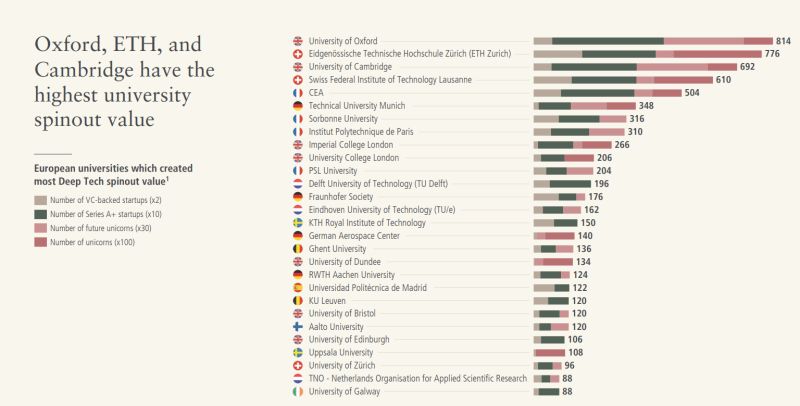

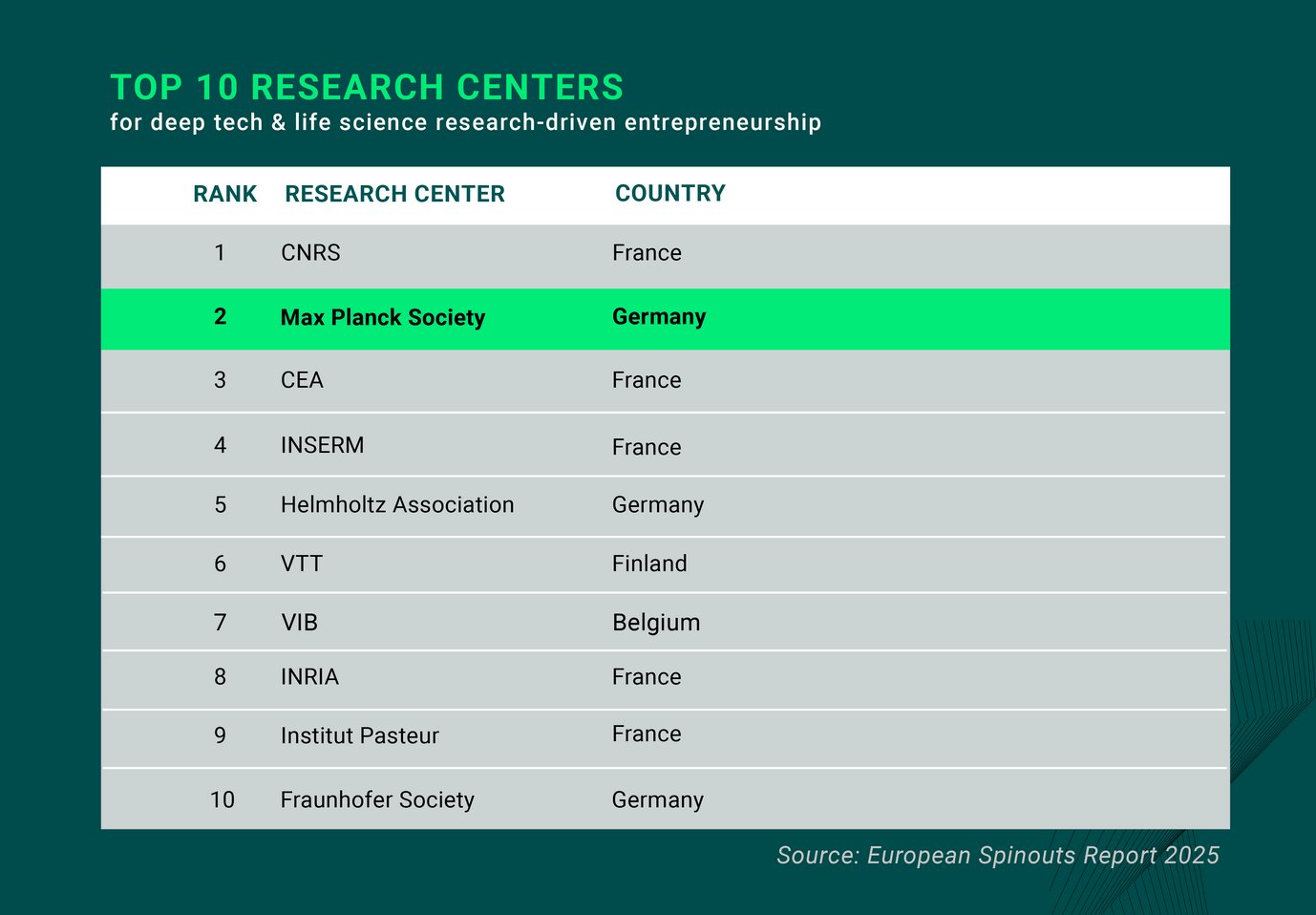

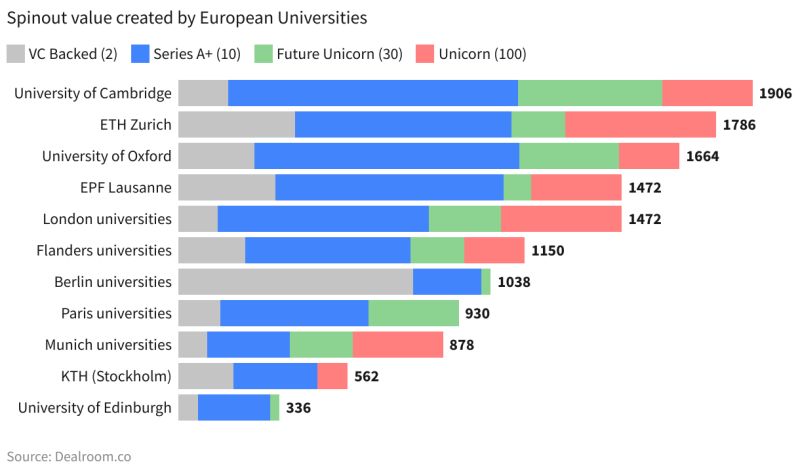

What's particularly striking is the sheer breadth of success. These aren't all coming from Cambridge or Oxford anymore, though those universities still dominate. They're emerging from Technical Universities in Copenhagen, research institutions in Zurich, and cutting-edge labs across Germany, France, and the Nordic countries. The ecosystem is maturing, deepening, and most importantly, producing exits that rival anything Silicon Valley can claim in specialized, mission-critical sectors.

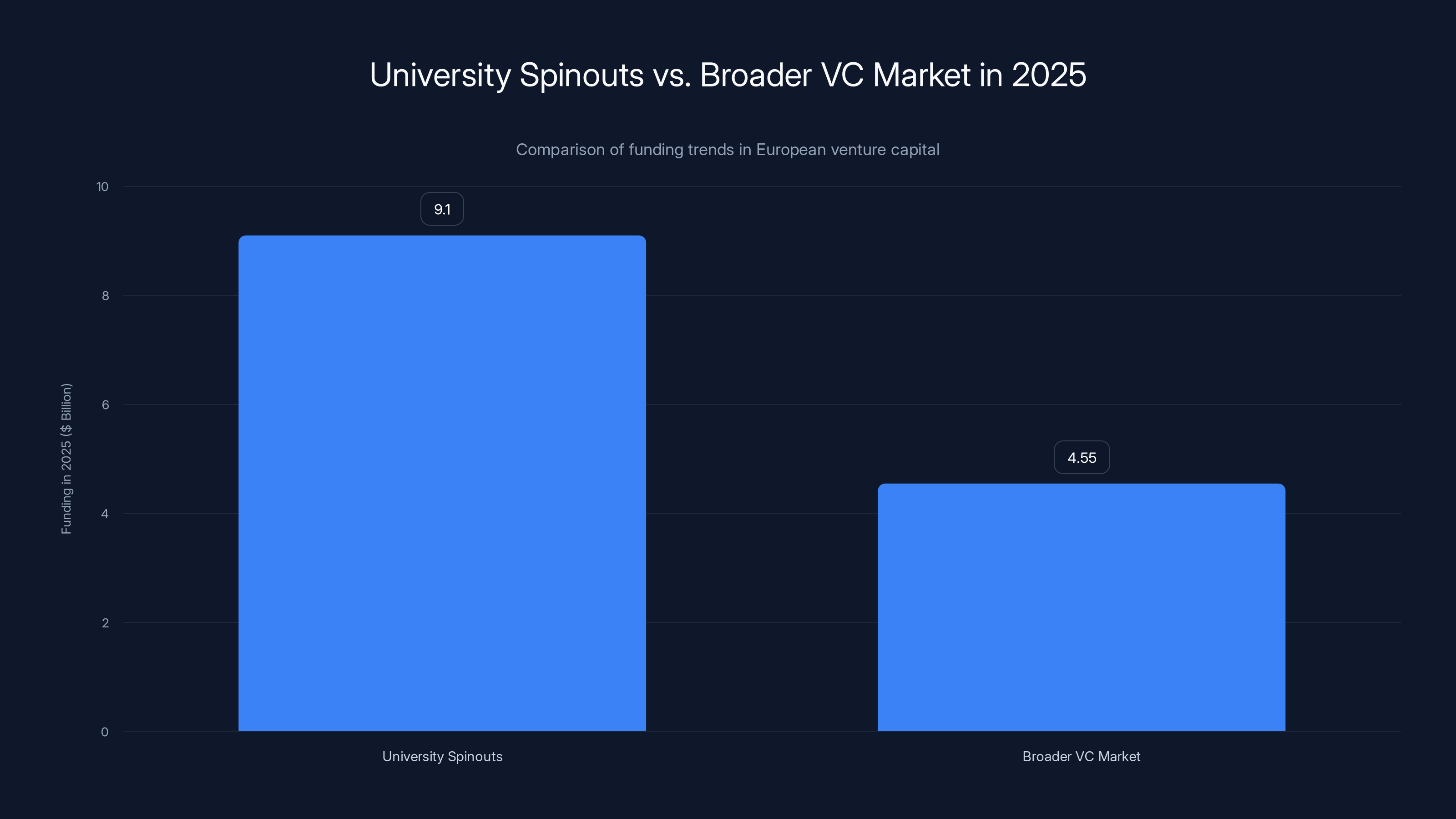

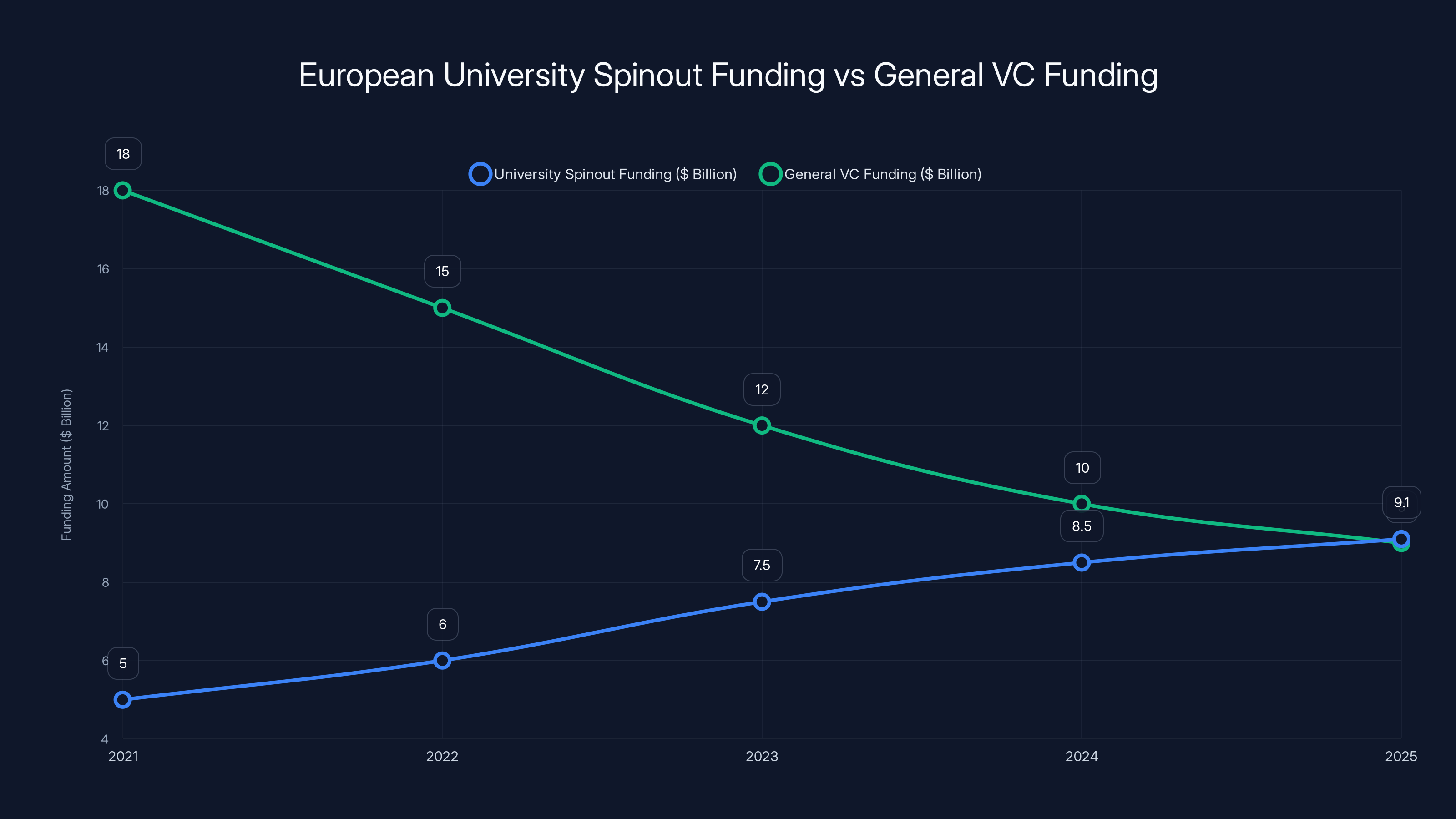

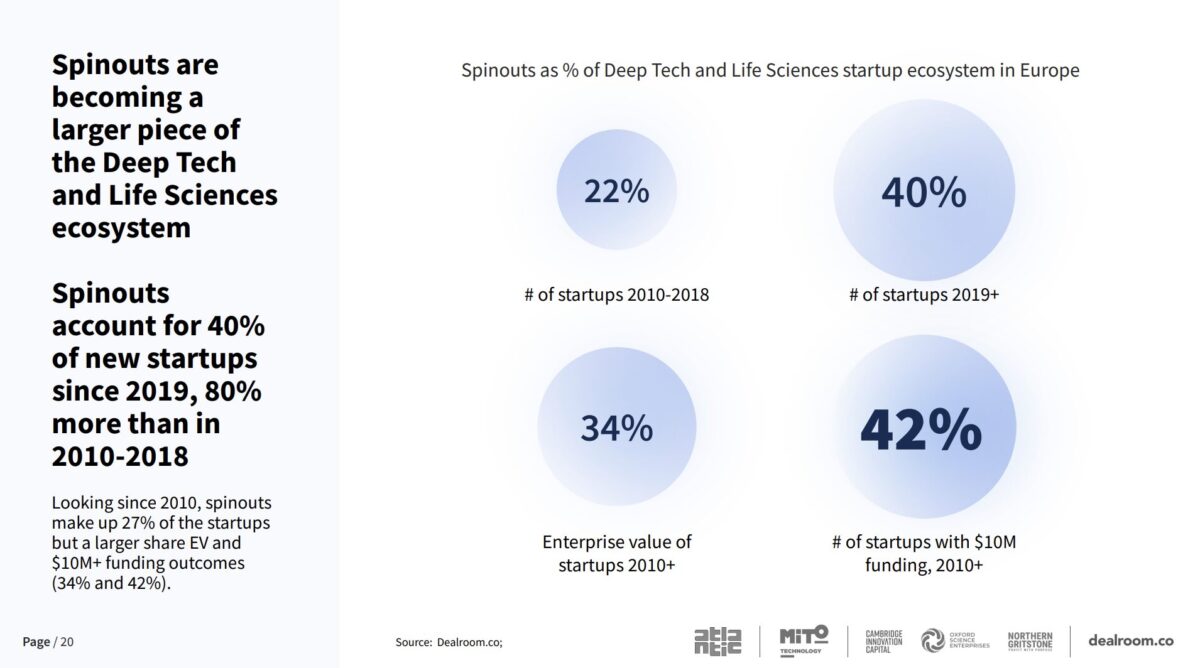

The numbers tell the story more clearly than any pitch deck ever could. European university spinouts in deep tech and life sciences are on track to raise approximately $9.1 billion in 2025, approaching an all-time high. Meanwhile, general VC funding across Europe has collapsed nearly 50% from its 2021 peak. That's the real story here. While the broader European startup ecosystem has cooled dramatically, university spinouts are heating up. Investors aren't chasing trendy consumer apps or another marketplace. They're backing founders with Ph Ds, solid IP, defensible technology, and proof of concept built in university labs.

Why does this matter beyond venture returns? Because Europe has been underestimating its deep tech advantage for years. The continent has world-class research institutions, brilliant scientists who historically left for America, and massive unfunded potential outside the traditional startup corridors. What's changed isn't the quality of research. It's the infrastructure finally catching up.

TL; DR

- 76 European university spinouts reached 100M+ revenue in 2025, proving academic tech is a reliable exit pathway

- $9.1 billion raised by deep tech spinouts in 2025 (near all-time high) versus 50% decline in overall European VC funding

- Top universities remain Cambridge, Oxford, and ETH Zurich, but new hubs in Nordic countries and Germany are producing breakout companies

- Six major exits over $1B in 2025 alone, including acquisitions like Ion Q's purchase of Oxford Ionics

- New dedicated funds emerged in 2025 targeting university spinouts specifically, with €60M+ in capital committed to underexplored regions

In 2025, university spinouts raised approximately $9.1 billion, significantly outpacing the broader VC market, which saw a 50% decline. Estimated data for broader market.

Understanding University Spinouts: What They Are and Why They Matter

A university spinout isn't just a startup founded by someone who attended university. That would be almost every startup. A true spinout is a company built directly from academic research, intellectual property, or technology developed within a university or research institution. The founders are often researchers themselves, sometimes faculty members, and the core technology comes straight from the lab.

This matters because spinouts have built-in advantages that regular startups don't. They have peer-reviewed research backing their claims. They have patents filed before launch. They have scientific credibility that's difficult to fake. When a Cambridge spinout says its quantum computing algorithm outperforms competitors, it's not marketing speak. It's testable, often published in reputable journals, and often backed by years of research investment from the university itself.

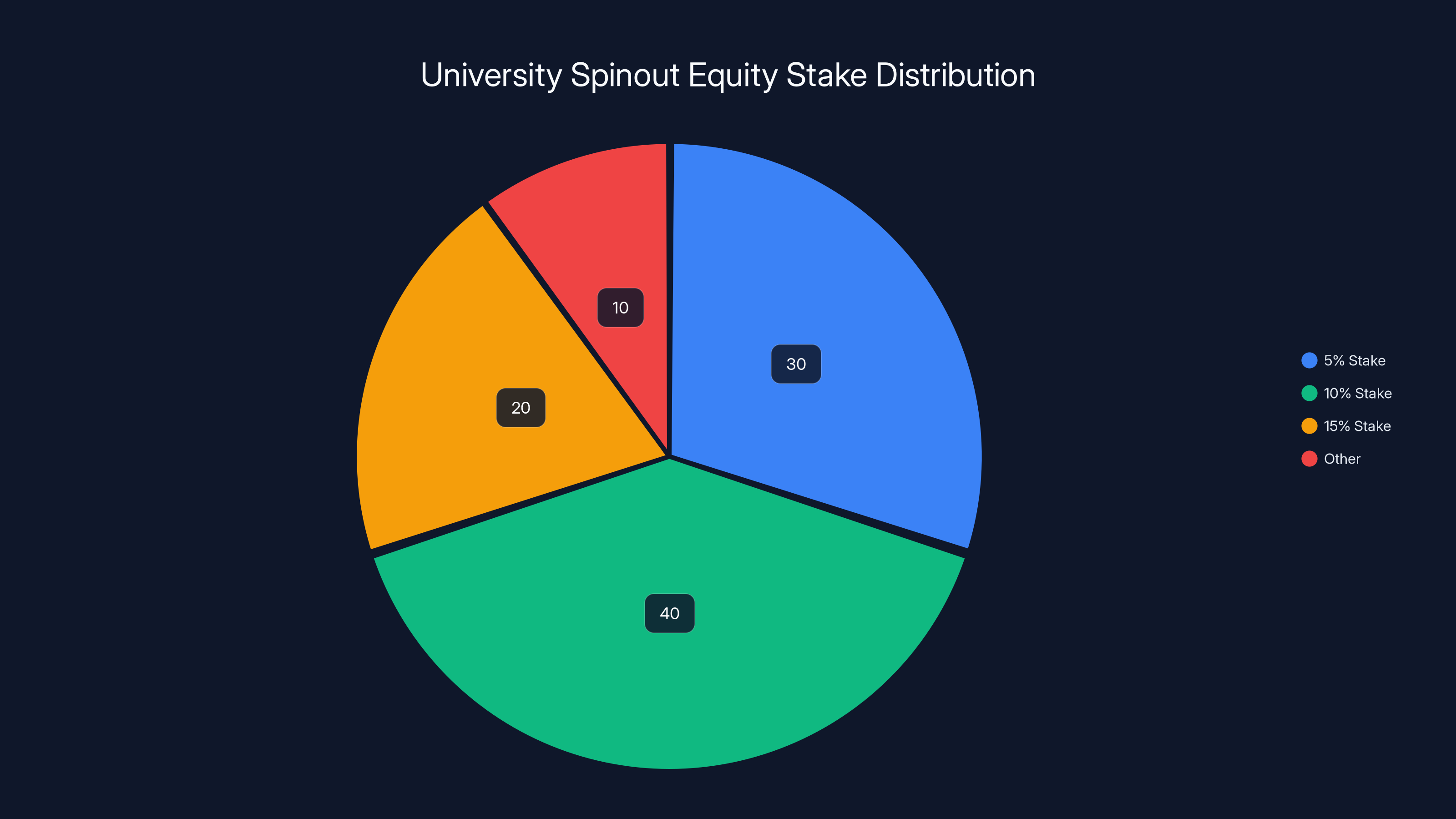

The structure also matters. Universities historically take equity stakes in spinouts, typically 5% to 15%, meaning the institution has aligned incentives to support the company's success. This creates an ongoing relationship between the lab and the commercial venture. As the company scales, it often maintains access to the original research team, stays connected to university resources, and can tap into the institution's credibility and networks.

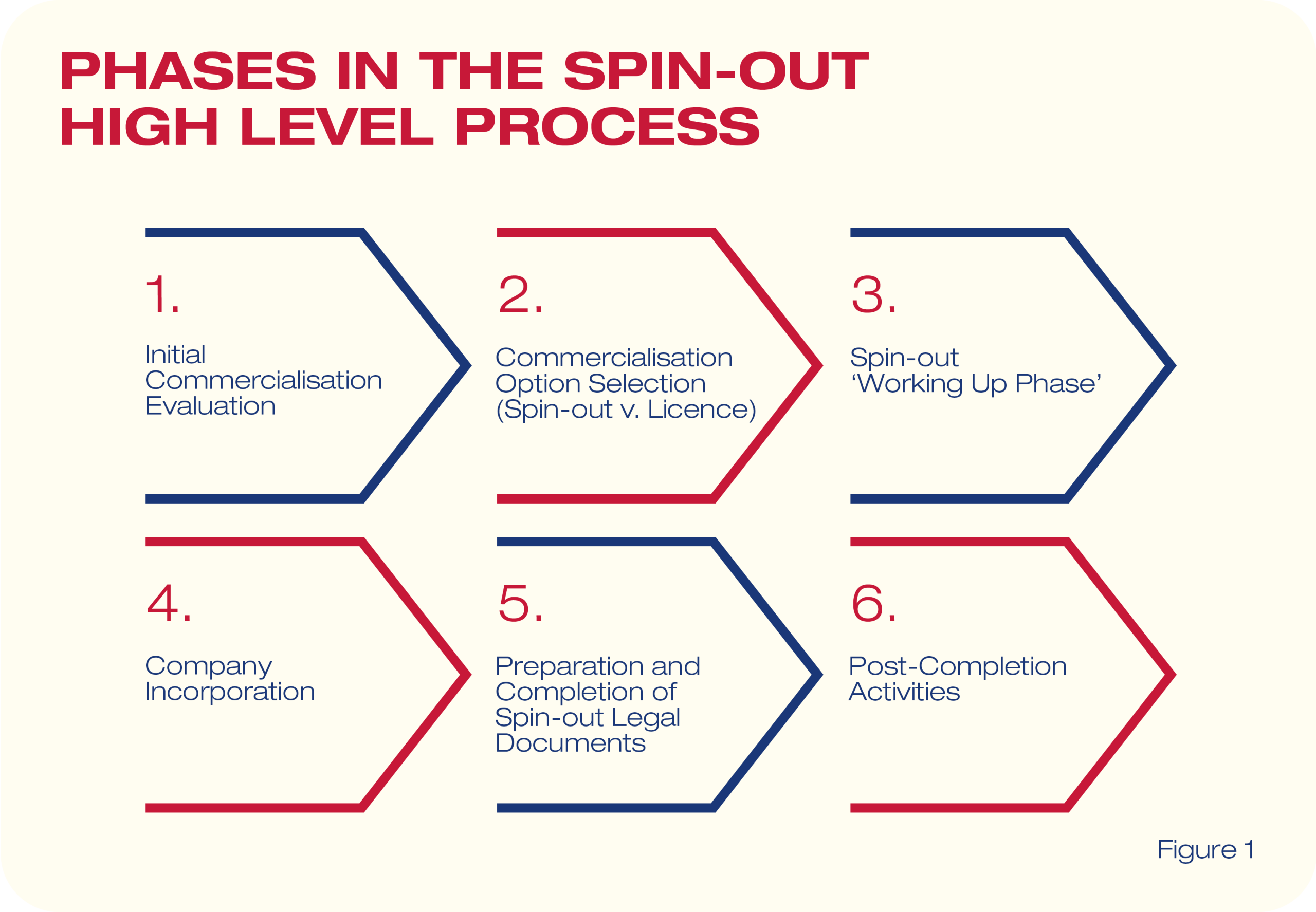

What's changed recently is the professionalization of this process. Ten years ago, university spinouts happened almost by accident. A researcher decided to commercialize their work, left the lab, and cobbled together funding. Now, universities have dedicated commercialization offices, structured IP transfer processes, and increasingly, dedicated venture funds supporting their spinouts specifically. This professionalization has compressed timelines and improved outcomes dramatically.

The sectors matter too. University spinouts aren't primarily software companies. They're concentrated in deep tech areas where sustained research investment creates real moats: quantum computing, advanced materials, biotech, aerospace, energy tech, semiconductor manufacturing. These are sectors where having published research, patent portfolios, and credibility actually reduces investor risk compared to a founder with a gut feeling and a pitch deck.

This fundamental difference explains why university spinouts attract different capital than traditional startups. Investors backing university spinouts are often sophisticated, technical, and willing to wait longer for returns because the risk profile is genuinely different. A quantum computing spinout with five years of peer-reviewed research and ten patents has a different risk profile than a mobile app startup with a clever idea and a founder with no technical background.

Estimated data shows university spinout funding rising to $9.1 billion by 2025, while general VC funding declines by nearly 50% from its 2021 peak.

The European Advantage: Why Deep Tech Thrives on This Continent

Europe doesn't compete with Silicon Valley on speed. It never has, and it never will. Silicon Valley moves fast, breaks things, and pivots based on market trends. That's not Europe's strength.

Europe's advantage is sustained, deep, expensive research. The continent has centuries of scientific tradition, world-class research institutions funded by governments that actually believe science matters, and a culture that respects expertise and deep technical knowledge. When a European university funds a biotech lab for 15 years without expecting quarterly results, that's when breakthroughs happen.

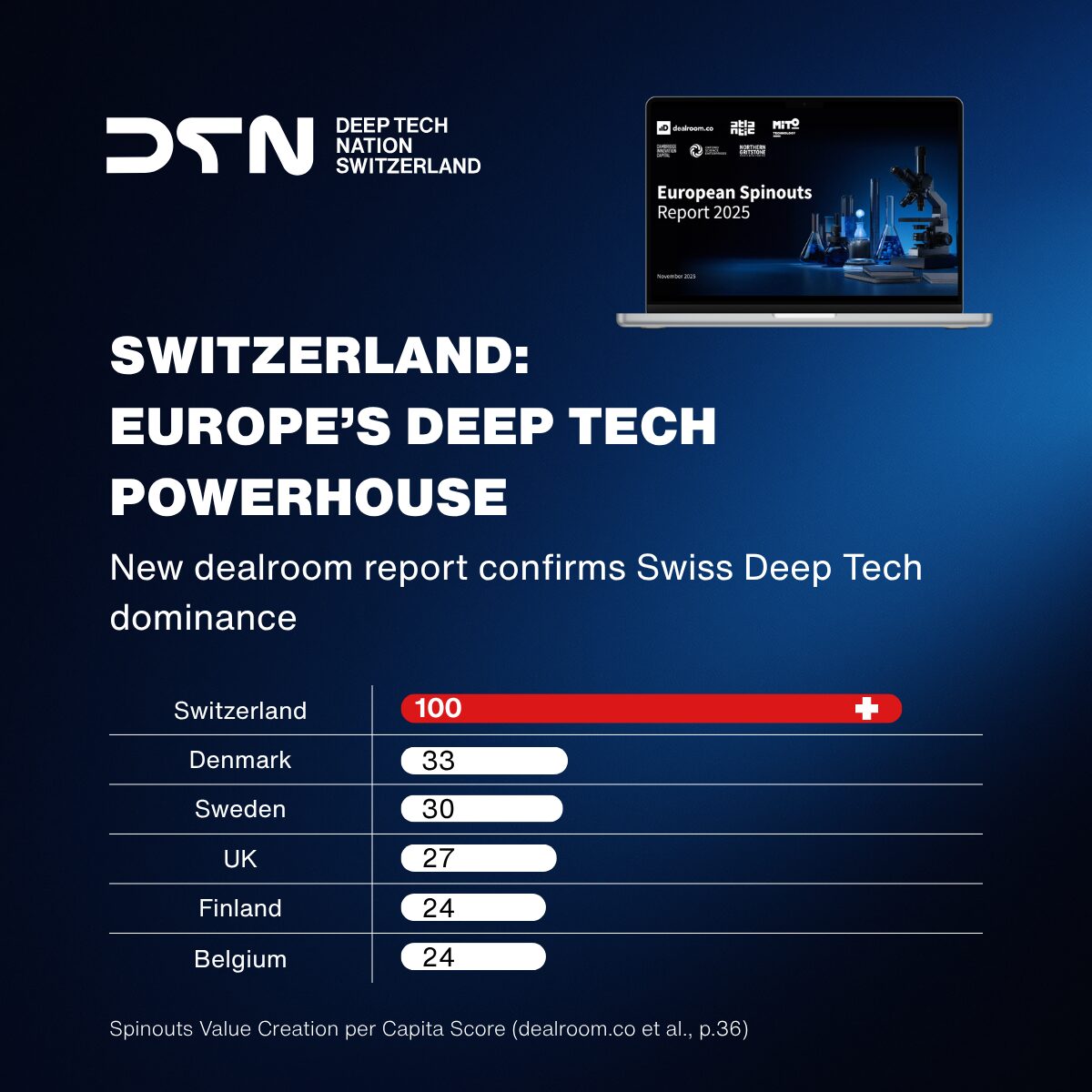

The institutions themselves are extraordinary. ETH Zurich consistently ranks in the top five universities globally for research output and has produced spinouts in quantum computing, semiconductors, and advanced materials that rival anything coming out of MIT or Stanford. The University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory has been producing physics breakthroughs since the 1870s, and that continuous research pipeline has birthed dozens of successful spinouts in deep tech.

But it goes deeper than prestige. Europe has several structural advantages for deep tech specifically. First, regulatory environment. In sectors like autonomous systems, quantum computing, and semiconductors, Europe's careful regulatory approach means companies founded there can navigate complex oversight earlier and more effectively. A drone company starting in Europe understands regulations that will eventually apply globally. That's an advantage when scaling internationally.

Second, specialization. While Silicon Valley spreads capital across every conceivable sector, European investors and institutions have gone deep in specific areas. There are clusters of quantum computing expertise around Zurich and the Netherlands. Biotech concentration around Cambridge and Basel. Semiconductor research centered in Germany and the Netherlands. This clustering means better talent recruitment, more knowledge transfer between companies, and easier access to domain expertise.

Third, patient capital. European investors and universities accept longer timelines to profitability. A quantum computing spinout might not generate revenue for seven years. An American VC fund would get antsy. European institutions, often with longer fund timelines and government backing, can wait. This allows founders to focus on building genuinely transformative technology rather than hitting aggressive revenue targets.

Finally, cost structure. While salaries for senior researchers in Europe are sometimes lower than in Silicon Valley, the cost of living and operational expenses are generally lower. This means founding teams can bootstrap longer or stretch seed funding further. A team of five Ph Ds can start a deep tech company in a European city for far less capital than the same team would need in Palo Alto.

The 2025 Breakout: How University Spinouts Outpaced Market Trends

The year 2025 presents a fascinating paradox in European venture capital. The broader ecosystem struggled. Overall VC funding declined nearly 50% from peak. Many traditional venture funds faced pressures to return capital to LPs without major exits. The narrative around European tech became pessimistic.

Except for university spinouts. That specific segment kept accelerating.

The numbers are stark. European deep tech and life sciences spinouts raised approximately $9.1 billion in 2025, approaching the all-time high. Compare that to the broader market decline and you see a clear flight to safety by sophisticated investors. When capital gets scarce, it concentrates in the safest bets. For VCs, university spinouts with Ph D founders, proven research, and complex technical moats suddenly look much safer than a Series B consumer app with unclear unit economics.

What changed to make 2025 special? Several factors aligned simultaneously.

First, the exit window opened. Six university spinouts delivered acquisitions or significant exits exceeding $1 billion in value during 2025 alone. Oxford Ionics being acquired by the American company Ion Q for a reported premium represented the kind of validation that ripples through investor psyches. When a UK-based quantum computing spinout exits to a major US player at a substantial valuation, every other university spinout in quantum computing becomes more fundable. Exits create exits.

Second, new funds emerged specifically targeting the spinout space. Two new vehicles reached inaugural closes in 2025, both explicitly focused on university spinouts. PSV Hafnium, based in Denmark, closed its first fund at €60 million (approximately $71 million), oversubscribed, with explicit focus on Nordic deep tech. U2V (University 2 Ventures), with offices across Berlin, London, and Aachen, completed its first closing targeting similar capital for university spinouts across continental Europe. These funds represented institutional validation that the spinout model works.

Third, the model proved repeatable. Early pioneers like Cambridge Innovation Capital and Oxford Science Enterprises have now fully matured, generated returns, and exited some portfolio companies successfully. Their success created a playbook. Universities saw it worked. New fund managers saw the returns were real. The path became less experimental and more systematic.

Fourth, capital composition shifted. Historically, European spinouts relied heavily on European investors. In 2025, nearly 50% of late-stage funding for deep tech spinouts came from outside Europe, predominantly from the United States. American VCs, unable to find enough compelling opportunities domestically due to market saturation and competition, increasingly looked to Europe for deep tech deals. This influx of patient, sophisticated capital from established American firms accelerated growth.

Finally, the broader tech narrative shifted toward fundamentals. During the 2016-2021 boom, investor appetite was vast and undiscriminating. Any startup with a compelling narrative and a coachable founder could raise capital. By 2025, that changed. Investors wanted defensible technology, real IP moats, and proven business models. University spinouts, by definition, have stronger IP positions than most startups. This alignment of investor preferences with spinout characteristics was fortuitous timing.

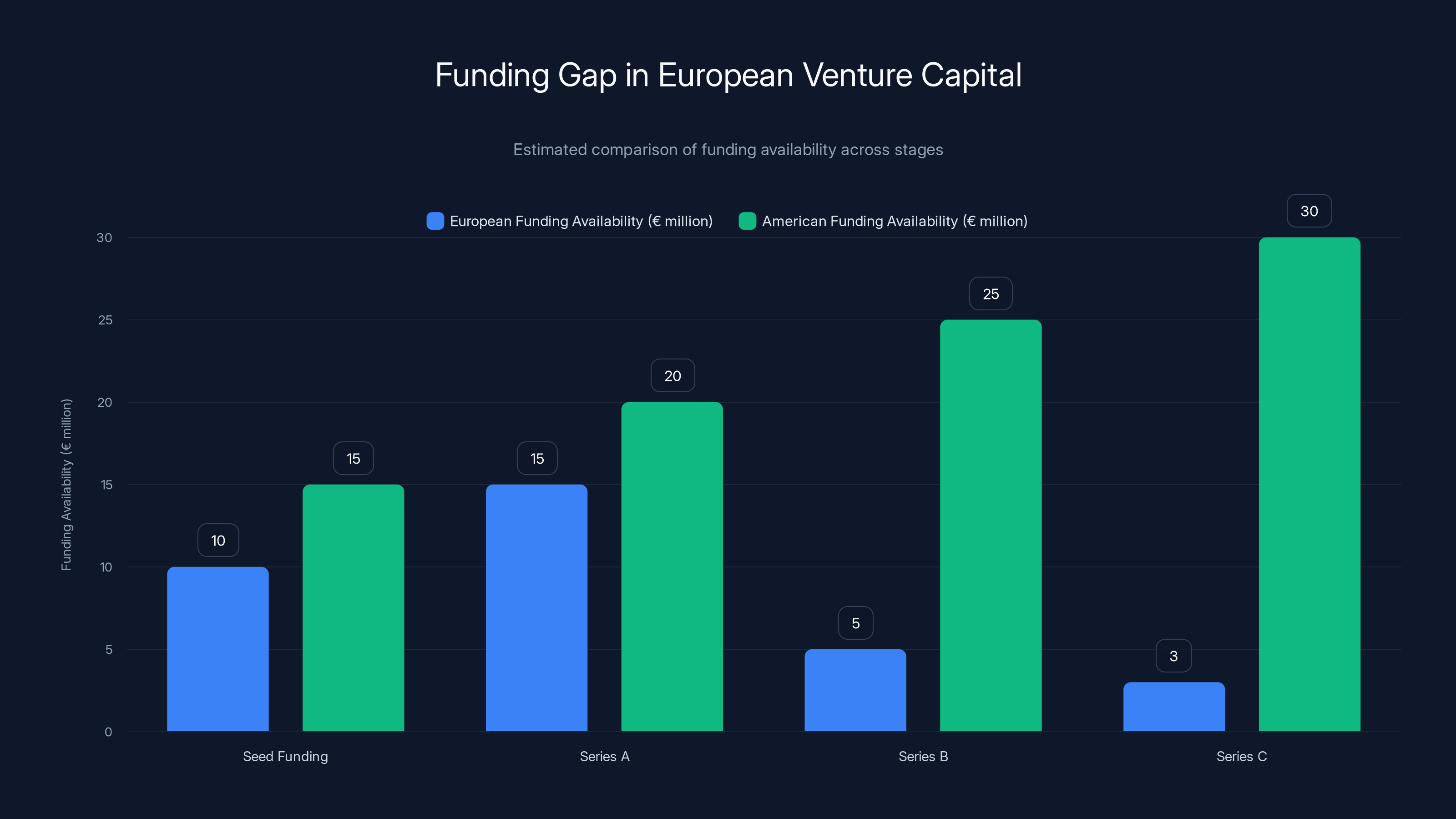

Estimated data shows a significant gap in Series B and C funding availability between European and American venture capital, highlighting the challenge for European spinouts seeking growth capital.

Cambridge, Oxford, and ETH Zurich: The Established Powerhouses

If you're mapping European spinout geography, three institutions still dominate the landscape and will for the foreseeable future: Cambridge, Oxford, and ETH Zurich.

Cambridge has established itself as essentially the MIT of Europe, with a spinout ecosystem so mature that it functions almost like a venture fund itself. The university's technology transfer office doesn't just facilitate spinouts; it actively recruits talented researchers, helps them frame commercial applications of their work, and connects them with advisors and early investors. The university's endowment and treasury have made strategic venture investments, further aligning the institution with spinout success.

What makes Cambridge particularly powerful is breadth combined with depth. The university produces spinouts across quantum computing (Xanadu), biotechnology (numerous), advanced materials (multiple), and semiconductor-adjacent fields. The university isn't just a single point of deep research; it's an institution where multiple research clusters achieve world-leading status independently. A researcher coming out of Cambridge's physics department has credibility in quantum. Someone from the medical sciences division has credibility in biotech. This breadth means more founders, more startup formation, and more probability of significant exits.

Oxford operates similarly but with slightly different strengths. Oxford's spinout ecosystem is similarly mature and well-supported, with several notable differences. First, Oxford has deeper historical strength in basic science and pure research, which sometimes translates to more foundational breakthroughs that take longer to commercialize. Second, Oxford tends to produce more life sciences and medical research spinouts relative to physics or computer science spinouts. Third, Oxford has been particularly successful at supporting spinouts through the medium-term where many innovative companies struggle: the Series B to Series D stage where capital requirements increase but product-market fit isn't yet obvious.

ETH Zurich brings different characteristics to the powerhouse triumvirate. The Swiss institution is deeply strong in physics, engineering, and materials science. The spinouts emerging from ETH tend to be in robotics, advanced materials, semiconductors, and quantum technologies. Unlike Cambridge and Oxford, which operate in the UK's relatively dense cluster of venture capital, ETH exists in Switzerland's smaller but highly sophisticated investor ecosystem. This sometimes means ETH spinouts attract different capital sources: family offices, strategic corporate investors from Switzerland's pharma and manufacturing sectors, and European VCs with Swiss anchors.

Together, these three institutions account for a meaningful percentage of all high-value European spinout exits. But increasingly, their dominance is less about being the only places where great research happens and more about being the most professionalized at converting research into ventures.

The real story of 2025 is that other universities are learning the playbook. Technical University of Denmark, where PSV Hafnium itself originated, is becoming a meaningful spinout generator. ETH's German research satellites and collaborations are strengthening spinout generation in Germany. Imperial College London, historically less visible in spinout narratives than Cambridge or Oxford, is producing increasingly significant exits. KTH in Sweden, Delft in the Netherlands, and others are improving their conversion rates from research to successful ventures.

This decentralization is healthy. It reduces dependency on three institutions and creates more opportunities for researchers outside the Oxbridge ecosystem to build significant companies.

The Nordic Surge: Emerging Hubs Creating Alternative Pathways

The most interesting story in European university spinouts isn't what's happening at Cambridge. It's what's happening in Copenhagen, Helsinki, Stockholm, and across the Nordic region.

The Nordic countries have always had strong research institutions and high quality of life that attracts talented researchers. What changed recently is the infrastructure specifically supporting spinout conversion. The emergence of PSV Hafnium is partially notable because of its capital size, but more importantly because it represents explicit institutional recognition that Nordic research institutions hold substantial untapped potential.

Denmark's Technical University, where PSV Hafnium originated, exemplifies this. DTU has world-class research across energy technology, materials science, and advanced manufacturing. Historically, founders graduating from DTU often moved to Copenhagen's venture ecosystem or left Denmark entirely. Now DTU is actively building commercial pathways for its own research. The university established formal technology transfer processes, recruited experienced startup mentors, and created structured connections between lab research and capital. The result is more spinout formation directly from campus.

But Denmark is just one part of the Nordic story. Finland has exceptional strength in semiconductor research and advanced materials, concentrated around the University of Turku and other institutions. One PSV Hafnium investment, Sisu Semi, exemplifies the opportunity. Sisu Semi leveraged a decade of research at University of Turku in surface cleaning technology for semiconductor manufacturing. The company is addressing a critical manufacturing step with technology that's genuinely differentiated because of its research lineage. Without the decade of academic research, this company couldn't exist. With it, it has a technical moat competitors can't match.

Sweden, through KTH and other institutions, has deep expertise in materials science, energy tech, and systems engineering. Norwegian research institutions, though smaller, concentrate on specialized areas like advanced manufacturing and marine technology. These aren't areas attracting massive venture capital narratives, but they're areas where research-backed companies can build sustainable, profitable, lower-profile businesses.

What makes the Nordic story interesting for the broader European ecosystem is that it proves the spinout model works outside the Oxbridge bubble. You don't need to be at the world's most famous university to create a successful spinout. You need quality research, technical founders willing to commercialize it, and sufficient capital infrastructure. These conditions are increasingly present across Nordic universities.

The strategic advantage for investors backing Nordic spinouts is portfolio diversification by geography and sector. While Cambridge produces quantum computing spinouts, Nordic institutions are producing semiconductor technology, advanced materials, and energy tech. Spreading capital across geographies also reduces concentration risk. If all your spinout bets are in the UK, you're exposed to UK policy changes, local talent competition, and market concentration. Nordic diversification reduces that risk while accessing undervalued deal flow.

The bigger picture is that the Nordic success story is creating a template for other emerging hubs. If Denmark and Finland can build sustainable spinout ecosystems, so can other regions with strong research institutions. This decentralization of spinout generation is strengthening European deep tech broadly.

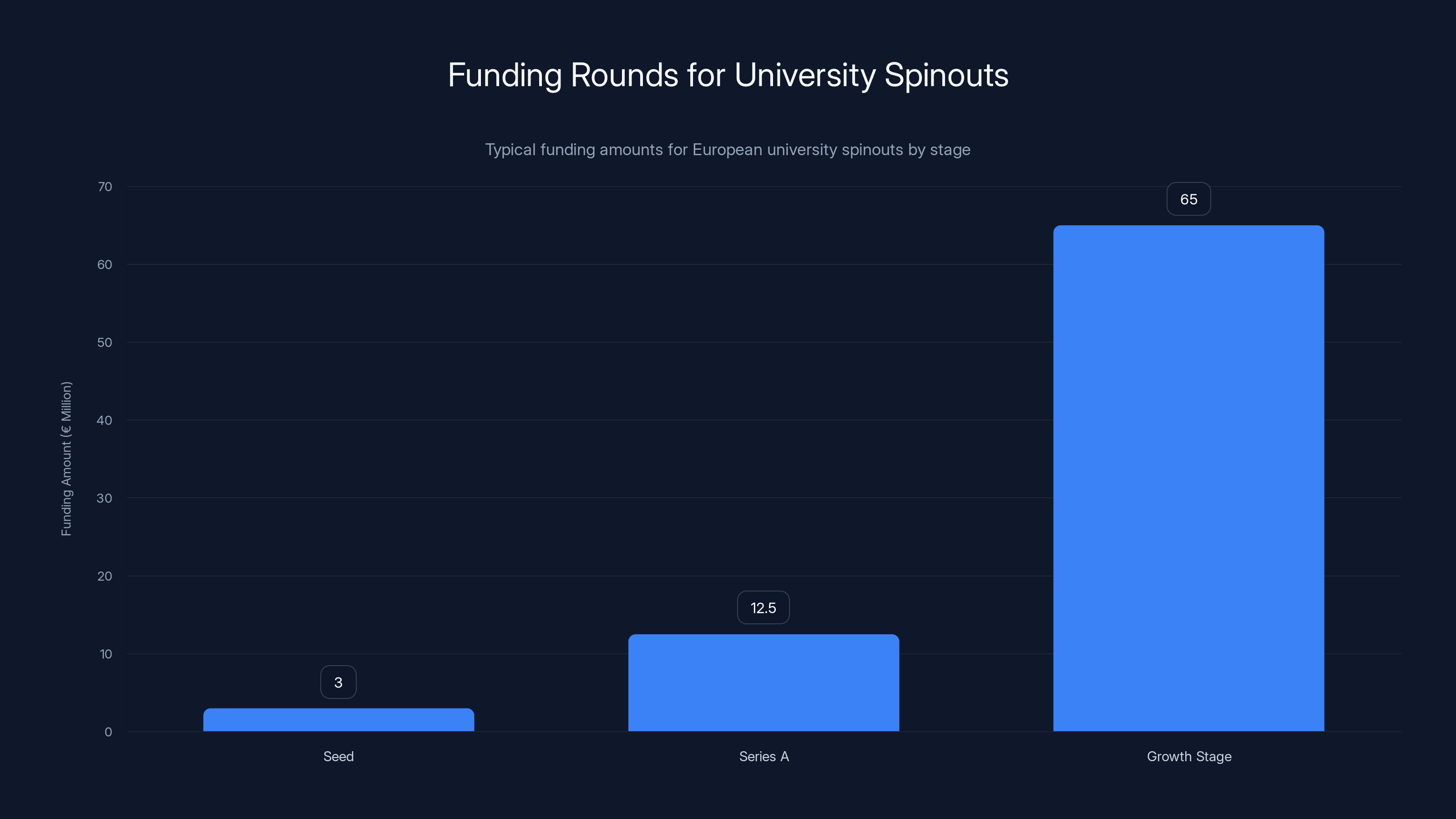

University spinouts typically raise €1-5 million in seed rounds, €5-20 million in Series A, and €30-100 million in growth-stage funding. Estimated data based on typical ranges.

Deep Tech Sectors Dominating Spinout Valuations

Not all spinouts are created equal. The ones reaching billion-dollar valuations are concentrated in specific sectors where research depth creates defensible competitive advantages. Understanding which sectors are producing breakout spinouts helps explain where future capital will flow and why certain universities outperform others.

Quantum computing stands out as the most prominent deep tech spinout sector. Multiple European quantum computing spinouts have achieved unicorn status, and several are in advanced funding rounds approaching potential exits. What quantum computing has that other sectors sometimes lack is a clear narrative about future importance combined with genuine technical barriers to entry. You cannot build a competitive quantum computer without years of physics research. This inherent moat makes quantum computing naturally suited to research-founded companies. Universities with quantum research programs produce spinouts; those spinouts attract capital; capital creates more competition, driving innovation.

Aerospace and advanced manufacturing spinouts represent another dominant category. Companies like Isar Aerospace (rocket manufacturing) and others in this space benefit from the massive complexity and regulatory requirements of aerospace. A spinout can't compete in traditional commercial aviation, but in new launch services, advanced satellite propulsion, or specialized manufacturing, university-backed companies with deep technical expertise are actually advantaged over traditional aerospace contractors.

Biotech and life sciences spinouts are probably the largest category by number, if not always by individual valuations. European biotech has a long history of university spinouts, particularly from Cambridge and other UK institutions. The sector benefits from long development timelines (10-15 years to commercialization) and high regulatory barriers, both of which suit research-backed founding teams more than traditional entrepreneurs. European biotech spinouts are increasingly competing with American biotech at the highest levels, particularly in drug discovery and advanced therapeutics.

Semiconductor and materials science spinouts are emerging more recently but growing rapidly. Advanced semiconductor manufacturing, semiconductor materials, and semiconductor design tools are all areas where European universities have deep research but historically lacked commercialization infrastructure. As capital flows to semiconductors, spinouts in this area are receiving increased attention. Companies addressing specific semiconductor manufacturing challenges with university-derived technology are well-positioned.

Robotics and autonomous systems represent another significant category. European universities, particularly in Germany and Switzerland, have strong robotics research. Spinouts in this sector can serve industrial automation, surgical robotics, and autonomous systems markets. The combination of hardware complexity and software sophistication makes these naturally suited to university spinouts with multidisciplinary research backing.

The sector concentration matters for understanding future trends. Capital flowing into spinouts isn't evenly distributed. It concentrates where research depth exists and where technical barriers protect against competition. A biotech spinout from Cambridge faces less direct competition from consumer software startups because the sectors are completely different. This natural segmentation is healthy for spinout sustainability.

The Capital Structure Shift: How Funding Patterns Have Changed

Historically, European spinouts were funded entirely or predominantly by European investors. Venture capital was geographically segmented. American funds focused on America. European funds focused on Europe. Australian funds focused on Australia. This segmentation protected nascent venture ecosystems from being entirely dominated by foreign capital.

That structure is shifting, particularly for university spinouts. Nearly 50% of late-stage funding for European deep tech spinouts now comes from outside Europe, predominantly from American venture capital firms. This represents both opportunity and risk.

The opportunity is clear: access to patient, experienced capital. American firms like Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia, and others have deep expertise in deep tech. They have international networks, downstream capital relationships with growth-stage investors, and experience taking companies through multiple funding rounds. For a European spinout founder, access to that capital can be genuinely valuable, particularly when scaling globally.

The risk is equally real: capital flight and value leakage. When American investors take large stakes in European spinouts, subsequent funding rounds may come from America, potentially diluting European investors and reducing capital accumulation in Europe. As spinouts scale, some may relocate operational headquarters to the US to be closer to capital and talent. This creates a leak in European value creation. A spinout may originate in Europe but deliver returns to American investors.

This is not unique to spinouts. It's a broader European venture challenge. Europe generates great ideas and research but struggles to retain capital and value as companies scale. The spinout space is simply a microcosm of this larger issue.

What's interesting about 2025 specifically is the emergence of new European funds explicitly addressing this gap. PSV Hafnium and U2V are both attempting to build European capital pools for spinout funding, keeping more capital within the European ecosystem. If successful, these funds could shift the capital composition back toward more European dominance in spinout funding.

The capital structure also matters for founder dynamics. Early-stage spinout funding historically came from university-affiliated funds or government grants. As spinouts scale, they increasingly need traditional venture capital. Venture capital comes with expectations around governance, timelines to exit, and return requirements. University founders accustomed to research-driven timelines sometimes chafe against VC demands for aggressive scaling. Smart investors recognize this and adjust their approach. Experienced spinout investors understand that research-backed companies sometimes need more patience than traditional startups.

The composition of syndicate investors is also shifting. Early spinout rounds increasingly include corporate venture capital from strategic buyers. A semiconductor materials company getting capital from semiconductor manufacturers. A biotech spinout getting capital from pharma companies. These strategic investments accelerate learning about the market and often de-risk the eventual acquisition. They're not always the best outcomes for founders seeking maximum returns, but they're increasingly common.

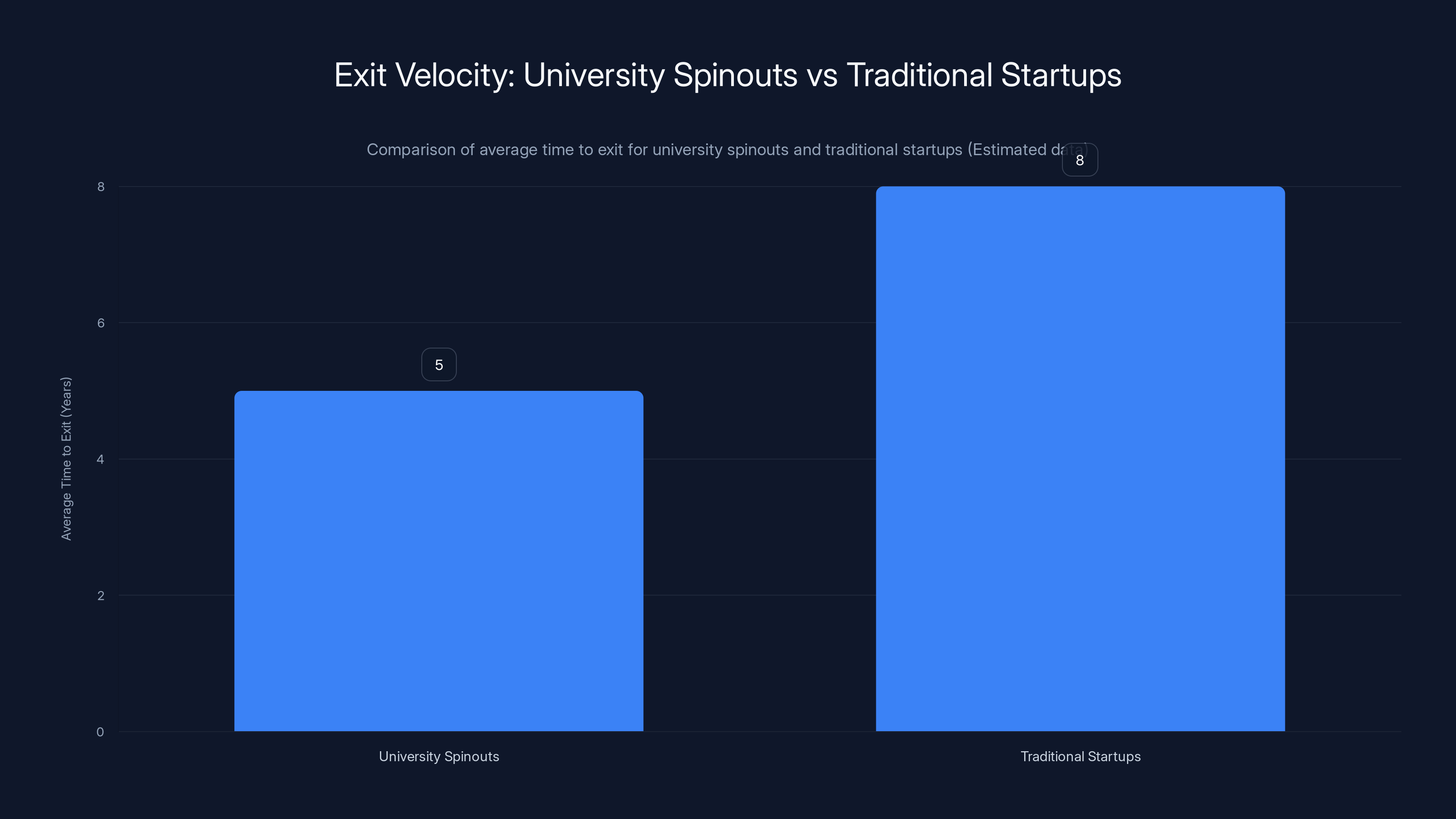

University spinouts typically reach acquisition or IPO stages faster, averaging 5 years compared to 8 years for traditional startups. Estimated data highlights structural advantages in IP and regulatory pathways.

Exit Velocity: Why University Spinouts Exit Faster Than Traditional Startups

One of the most striking patterns in the 2025 spinout data is exit velocity. University spinouts reach acquisition or IPO stages faster than comparable non-spinout companies. This isn't luck. It's structural.

The research foundation creates defensible IP. Acquiring companies know that a spinout comes with not just the founder team but also patents, published research, and technical validation. Buying a spinout often means acquiring IP that would take years to develop independently. This value is immediately obvious to strategic acquirers. Corporations looking to build capabilities quickly often prefer acquiring spinouts to developing technology internally.

The founder quality also matters. Spinout founders are typically Ph D researchers with deep expertise in their specific field. They're not first-time entrepreneurs with an intuition about market opportunity. They're domain experts who understand the technical landscape deeply. Acquiring companies value this expertise highly because it reduces execution risk. The team coming with the acquisition understands the problem space and the technical solutions at a level that takes competitors years to develop.

The time-to-product is often shorter. A spinout doesn't need to discover what technology to build. The technology already exists from research. Spinout teams need to productize and commercialize, but they're not discovering the underlying science. This compresses development timelines substantially compared to startups building technology from scratch.

The regulatory pathway is often clearer. Particularly in biotech, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices, spinouts emerging from university research have often already navigated some regulatory hurdles. Published research establishes safety and efficacy parameters. Regulatory agencies are somewhat familiar with the work. The path to commercialization, while still long, is less uncertain than a startup with novel technology claiming efficacy.

This faster exit timeline creates a flywheel. Early spinout exits validate the model. Later spinouts can point to successful precedents. Capital flows faster because proven exits reduce investor anxiety. More capital enables more spinout formation. More spinouts produce more exits. The system reinforces itself once it reaches a critical mass.

Six major spinout exits exceeding $1 billion in value during 2025 created this validation effect. Each exit proved the model works. Each acquisition price-point established valuation benchmarks for similar spinouts. This means later spinouts in similar sectors can potentially raise capital at higher valuations because comparable exits established the precedent.

The other side of faster exits is founder dynamics. When a spinout exits quickly, often five to seven years after founding, founders are still relatively early in their career arc. They're not necessarily ready to settle. Some become serial entrepreneurs, starting follow-on spinouts. Others join VC firms or become advisors to other spinouts. This creates a talent cycle where the system produces mentors, advisors, and future founders who understand the spinout model deeply because they've lived it.

Growth Capital Challenges: The Persistent Gap in European Venture Funding

Amid all the optimism about spinout success, one structural problem remains unsolved: growth capital availability. While early-stage spinout funding has become more accessible and late-stage acquisition opportunities have opened up, the middle ground remains challenging.

A spinout typically progresses through funding stages: initial university investment and grants, seed funding from specialized spinout investors or university-affiliated funds, Series A from venture firms, Series B and C for scaling, and then either acquisition or IPO. The problem emerges most acutely in Series B and C rounds.

At Series B, capital requirements jump substantially. A spinout that raised €5 million in Series A might need €20-30 million in Series B to properly scale operations. At this stage, the company needs to prove product-market fit and begin scaling across international markets. American investors and American capital markets are well-equipped to provide this capital. European capital markets are less developed at this stage.

Many European venture firms have smaller funds or longer deployment timelines that make Series B and C participation less attractive. When growth-stage capital becomes scarce, spinouts often seek American investors even when they'd prefer to maintain European capital composition. This creates the capital flight dynamic discussed earlier: European-founded companies increasingly seeking American capital because American firms have larger growth-stage funds.

Government initiatives have attempted to address this gap. The European Investment Bank, development finance institutions, and European governments have created growth capital programs. These programs help but don't fully solve the problem. A €50 million government growth fund might make 2-3 meaningful investments per year. At that rate, the capital isn't keeping pace with spinout demand.

One structural challenge is that European limited partners (pension funds, insurance companies, endowments) have historically been more conservative in venture capital allocation than American counterparts. American pension funds might allocate 5% of portfolios to venture. European institutional investors often allocate 1-2%. This limits the total capital pool available for growth-stage investing. Even as awareness of spinout success grows, the underlying investor base willing to allocate capital to venture capital funds hasn't expanded proportionally.

This isn't unique to spinouts. It's a broader European venture challenge. But for spinouts specifically, it's particularly acute because they often need more capital to scale than traditional software companies. A quantum computing spinout scaling internationally needs more capital than a Saa S startup with similar revenue growth rates.

Smart spinout teams recognize this and plan for it. They maintain relationships with American venture investors from early stages, understanding that growth capital may require external capital injection. Some spinouts are structured to be attractive to acquisitions before the growth capital challenge becomes acute. Others actively plan for international expansion and capital needs as part of their funding strategy.

The most sophisticated spinouts are increasingly looking at alternative capital structures. Some are exploring debt financing from growth-focused lenders. Others are seeking strategic corporate investors who provide both capital and distribution. A few are even exploring staying private longer than traditional startups, using revenue and strategic partnerships to fund growth rather than aggressive venture capital.

Universities typically hold equity stakes in spinouts ranging from 5% to 15%, aligning their interests with the spinout's success. (Estimated data)

The Role of University Support Infrastructure in Spinout Success

A spinout's success isn't determined solely by the quality of research or the founders' ambition. The surrounding infrastructure—the university support systems, technology transfer offices, and ecosystem resources—significantly impacts outcomes.

Universities that have invested heavily in spinout infrastructure produce more successful companies. This includes dedicated technology transfer offices with experienced staff, not just administrators. It includes mentorship programs connecting spinout founders with experienced entrepreneurs and investors. It includes formal IP licensing processes that are transparent and fair. It includes early-stage funding or investment from university-affiliated funds. And increasingly, it includes connections with specialized spinout-focused investors.

Cambridge exemplifies this. The university has built a comprehensive support infrastructure for spinouts. The technology transfer office actively identifies commercializable research. The university's venture fund provides seed capital. The university's advisory networks connect spinout founders with experienced mentors. The result is a high volume of spinouts with relatively high success rates compared to general startup ecosystems.

Universities without this infrastructure produce less successful spinouts. Researchers with excellent technology but without support navigating startup formation, IP licensing, early funding, and scaling challenges often fail to build sustainable companies. They might reach Series A but struggle to scale without guidance. The technology might be excellent, but the business execution suffers.

The best-performing universities have also made key structural decisions around IP ownership and equity allocation. When universities take too large an equity stake in spinouts (sometimes 15-20%), it can complicate later capital raising. Investors may be hesitant to put capital into companies where the university retains large equity stakes. The university might have divergent interests around exit timing or strategic direction.

The most effective universities have found a balance: taking modest equity stakes (5-10%), accepting lower returns to themselves to enable better spinout outcomes. This is counterintuitive from a financial standpoint—universities could maximize returns by taking larger equity stakes—but it improves the overall spinout ecosystem and actually generates better long-term returns for the institution through the stronger companies it produces.

The other critical infrastructure element is human capital. Universities that have built strong networks of serial entrepreneurs, venture investors, and corporate executives willing to advise spinout founders create better outcomes. Founders benefit tremendously from advisors who have built and scaled companies before. Access to that experience is often more valuable than incremental capital.

Geography also matters within this infrastructure analysis. Universities in ecosystems with dense startup activity (Cambridge, Oxford, Zurich) benefit from local access to venture capital, specialized service providers, and peer companies. Universities in more isolated regions must build more of this infrastructure internally or create digital connections to distant resources. The most successful emerging spinout hubs are deliberately building this infrastructure despite geographic isolation.

Sector Deep Dives: Where Spinout Capital Is Concentrating

Quantum Computing: The Sector Everyone Is Watching

Quantum computing has become the marquee spinout sector, attracting capital and attention disproportionate to current revenue but proportionate to future potential. Multiple European quantum computing spinouts have achieved unicorn status, and the sector continues attracting capital aggressively.

What makes quantum computing particularly suitable for spinouts is that the technology is fundamentally derivative of academic research. Quantum computers aren't something companies figure out through trial and error in a startup garage. They require deep understanding of quantum physics, years of research into qubit stability, error correction algorithms, and hardware engineering. This depth of research prerequisite naturally favors companies emerging from university labs where this research has been ongoing.

European quantum computing spinouts are competitive globally. Companies emerging from ETH Zurich, Cambridge, and other institutions are competing with American and Chinese quantum initiatives at the highest levels. Some are focused on hardware (building actual quantum computers), others on software and quantum algorithms, and others on applications of quantum computing to specific problems. This diversity of approach is healthy for the sector.

The sector remains pre-revenue for most companies. Despite billion-dollar valuations, very few quantum computing spinouts generate meaningful revenue. They're funded on the thesis that quantum computing will become important in the future, and these companies will be critical infrastructure. This is venture capital betting on profound technological transitions.

Biotech and Life Sciences: Building Real Revenues

Biotech spinouts operate differently from quantum computing spinouts. While quantum computing is pre-revenue, many biotech spinouts generate meaningful revenue during early venture stages. Some biotech spinouts provide research services or tools to other biotech companies. Others are developing therapeutics or diagnostics with longer paths to commercialization but more obvious near-term revenue potential.

European biotech spinouts are increasingly competitive with American biotech on innovation metrics. Academic biotech research in Europe is world-class. Spinouts emerging from this research inherit that quality. The challenge, as discussed, is growth capital. American biotech companies often attract larger capital pools, enabling faster scaling. European biotech spinouts sometimes move slowly to market relative to American competitors simply because capital availability is more constrained.

The sector has also seen important shifts in funding sources. Pharmaceutical companies increasingly fund early-stage biotech spinouts through corporate venture programs. These relationships can be symbiotic: the spinout gets capital and potential acquirer, the pharma company gets early access to innovative research.

Advanced Materials and Semiconductors: An Emerging Opportunity

Advanced materials and semiconductor manufacturing represents the newest major spinout growth area. European universities have exceptional materials science research but historically lacked strong commercialization infrastructure. This gap is closing. As semiconductor supply chains become strategically important and countries invest in domestic semiconductor capacity, opportunities for spinouts addressing specific manufacturing challenges are opening up.

The capital requirements in this sector are higher than in biotech or software, and timelines to meaningful revenue are longer. But defensibility is exceptional. A spinout with unique semiconductor manufacturing technology protected by patents can build sustainable competitive advantages. Some semiconductor materials and process spinouts are achieving meaningful valuations based on strong IP positions, even before building large revenues.

International Dynamics: How European Spinouts Compete Globally

European spinouts increasingly compete globally, not just within Europe. This global competition dynamic shapes strategy, funding, and outcomes.

In deep tech sectors like quantum computing and advanced materials, competition is inherently global. A quantum computing company in Switzerland competes with quantum computing companies in America, Canada, and China. The competition isn't local. This means European spinouts must be able to raise international capital, recruit international talent, and operate globally from early stages.

European spinouts have both advantages and disadvantages in this global competition. Advantages include access to world-class research, quality engineers and scientists, and supportive regulatory environments in many sectors. Disadvantages include smaller home markets, later-stage capital scarcity, and less developed acquisition market relative to America.

Many European spinouts address this by targeting America aggressively. They raise capital partially from American investors, recruit some leadership from America, and plan for eventual relocation of headquarters to America if acquisition opportunities arise. This is pragmatic but represents a loss of value to the European ecosystem.

The most successful European spinouts are increasingly staying headquartered in Europe while building global operations. This is becoming possible because technology enables distributed teams, and European bases can be advantageous for certain sectors. A quantum computing company in Switzerland can recruit talent globally while maintaining European headquarters.

The global dynamics also matter for exit outcomes. An American acquirer might pay differently for European spinouts than European acquirers might. American technology companies often view European spinouts as strategic assets adding to their research and development capabilities. European corporate acquirers sometimes view spinouts as competitive threats rather than acquisition targets. This dynamic affects the attractiveness of various exit pathways.

The Future: Trends Shaping the Next Phase of European Spinout Growth

The spinout ecosystem is still relatively young in maturity. Even institutions like Cambridge and Oxford have only been deliberately creating spinouts for 15-20 years at scale. The ecosystem will evolve substantially in the coming years.

One clear trend is geographic diversification. As mentioned, spinout generation is spreading beyond Cambridge and Oxford to other universities and regions. This diversification will accelerate. Universities seeing peers' spinout success will invest in commercialization infrastructure. More geographic areas will produce successful spinouts, reducing dependency on a few elite institutions.

Second, sector evolution. Deep tech sectors evolving rapidly will become increasingly suitable for spinout models. Climate tech, for instance, involves complex engineering and research prerequisites well-suited to university spinouts. Similarly, biotechnology applications are expanding into areas like synthetic biology where research depth is essential. Spinouts will continue concentrating in sectors where academic research provides defensible advantages.

Third, capital pool growth. As awareness of spinout success grows, limited partners will allocate more capital to spinout-focused funds. This is already happening. Over time, dedicated spinout capital will become less scarce, reducing the growth capital gap.

Fourth, talent dynamics. As successful founders exit and become investors or advisors, knowledge about spinout dynamics will spread. More talented people will understand the opportunity. The quality of spinout founding teams should improve as the ecosystem matures.

Fifth, internationalization of talent. European universities will increasingly recruit researchers and faculty from globally. Some of these international researchers will become spinout founders, bringing diverse perspectives and networks. This could accelerate spinout quality and global competition.

Sixth, regulatory evolution. Regulations affecting deep tech sectors are evolving rapidly. Semiconductor regulations, AI regulations, quantum computing security frameworks—all are in flux. Universities and spinouts that help shape these regulations while building compliant businesses will have advantages.

Finally, ecosystem coordination. Universities are increasingly coordinating with each other to build broader European ecosystems. Regional networks of universities, connecting research across institutions, could enable spinouts benefiting from research across multiple universities. This coordination could unlock opportunities where single-university research wasn't sufficient.

Practical Implications for Investors, Founders, and Institutions

For investors considering spinout opportunities, the key takeaway is that spinouts now warrant dedicated attention and capital allocation. The historical assumption that spinouts were riskier than traditional startups because they might be too focused on research is outdated. The exit data from 2025 proves spinouts are genuine opportunities. Building dedicated expertise in spinout investment is worthwhile.

For founders evaluating entrepreneurship, spinouts now represent a legitimate path with clear advantages. If you're a researcher with strong IP, building a spinout might be more advantageous than joining an existing company or continuing academic research. The infrastructure supporting spinouts is now sophisticated enough to support serious company building.

For universities, the message is clear: investment in commercialization infrastructure pays off. Universities seeing peer spinout success should invest in technology transfer, mentorship, and early-stage capital. The long-term returns to the institution exceed the costs.

For policymakers, the spinout story suggests that investment in research infrastructure and university support systems pays dividends in company creation and economic value. European governments supporting university research and spinout ecosystems are making strategic investments that compound over time.

FAQ

What is a university spinout?

A university spinout is a company founded to commercialize intellectual property, technology, or research developed within a university or research institution. Unlike regular startups founded by individuals who attended university, spinouts have core technology and often founders emerging directly from academic research. Spinouts typically retain some connection to their parent university through equity stakes and ongoing access to research resources.

Why are European university spinouts becoming so valuable?

European spinouts are producing significant exits because they combine world-class research with increasingly sophisticated commercialization infrastructure. Universities like Cambridge and Oxford have spent years building support systems for spinouts. Deep tech sectors like quantum computing and semiconductors inherently require research depth that spinouts provide through their academic origins. Additionally, sophisticated investors now recognize that research-backed companies have stronger IP protection and lower technology risk than traditional startups.

How much funding do university spinouts typically raise?

Funding amounts vary dramatically by sector and company stage. Early-stage spinouts might raise €1-5 million in seed rounds. Series A rounds typically range from €5-20 million. Growth-stage funding varies widely, with some spinouts raising €30-100 million or more. The variation depends on sector (biotech typically requires more capital), technical complexity, and market opportunity. In 2025, European deep tech spinouts collectively raised approximately €9.1 billion.

Which universities produce the most successful spinouts?

Cambridge, Oxford, and ETH Zurich historically dominate European spinout success, producing multiple unicorns and near-unicorns. However, other institutions like Imperial College London, Technical University of Denmark, and others are increasingly producing successful spinouts. Success depends less on university prestige than on the presence of strong research programs, dedicated commercialization infrastructure, and capital ecosystem support.

What sectors produce the most valuable spinouts?

Quantum computing, advanced materials, semiconductors, biotech, and aerospace represent the sectors producing the most valuable spinouts. These sectors share characteristics that favor spinouts: deep research prerequisites, defensible intellectual property, and long timelines to commercialization. Software spinouts are less common because software doesn't require the same level of fundamental research advantage.

How do spinouts differ from traditional venture-backed startups?

Spinouts differ fundamentally in their origin, IP position, founding team, and timelines. Spinouts emerge from research with existing intellectual property. Founding teams typically have deep domain expertise from academic backgrounds. Timelines to meaningful product are often longer but more certain because technology has been proven through research. Traditional startups often move faster but with higher technology risk.

What is holding back European spinout growth?

The primary constraint is growth capital availability. While seed and Series A capital for spinouts has become accessible, Series B and later-stage funding remains challenging in Europe. Nearly 50% of late-stage spinout funding comes from outside Europe, creating capital leakage. Additionally, some universities still lack sophisticated commercialization infrastructure, limiting spinout quantity and quality in those regions.

Are spinout exits increasing or decreasing?

Spinout exits are increasing. Six major spinout exits exceeding $1 billion occurred in 2025 alone. More importantly, the infrastructure supporting exits has become more sophisticated, with more experienced investors, clearer acquisition pathways, and greater strategic interest from corporate acquirers in acquiring spinout technology.

Should early-stage researchers consider starting spinouts?

Yes, if the research is sufficiently advanced and commercially relevant. Starting a spinout provides access to specialized capital, mentorship, and infrastructure specifically designed to support researcher entrepreneurs. Universities now have processes making IP licensing straightforward. The main requirement is that research is defensible and addresses a meaningful market opportunity. Researchers with strong IP and entrepreneurial interests should explore spinout options with their university's technology transfer office.

How will spinout funding evolve in coming years?

Spinout funding is likely to grow substantially as more capital pools allocate to dedicated spinout funds, as universities outside elite institutions build commercialization infrastructure, and as successful exits validate the model further. Growth capital availability is likely to improve gradually as European capital pools recognize spinout opportunity. Geographic diversification of spinout generation will accelerate, reducing concentration in a few elite institutions.

Closing: Why European Spinouts Matter Beyond Just Capital Returns

The rise of European university spinouts matters for reasons extending beyond venture capital returns and startup economics. It represents a fundamental shift in how Europe is organizing its competitive advantages in technology and innovation.

For decades, Europe's strength in research existed somewhat separately from its entrepreneurial economy. World-class research happened in universities. Entrepreneurship happened in startups. The connection between the two wasn't systematic. Researchers published papers. Entrepreneurs built companies. Knowledge flowed between these worlds, but slowly and inefficiently.

University spinouts are systematizing that connection. They're creating mechanisms where research naturally converts to commercial ventures. They're enabling researchers to build companies without abandoning research. They're creating pathways where academic excellence translates directly to economic value.

This matters because technology leadership requires both research excellence and entrepreneurial execution. A country can have outstanding research but lose economic benefit if that research doesn't convert to companies and products. Europe's risk historically was precisely this: world-class research that didn't translate to economic value and technology leadership.

Spinouts address this risk directly. They're creating a pipeline where research excellence in European institutions naturally produces companies, capital returns, and economic value. The fact that 76 spinouts have reached billion-dollar valuations or $100 million revenue suggests this pipeline is working.

The other reason spinouts matter is talent. Historically, talented researchers and engineers had to choose between careers in academia or careers in entrepreneurship. Spinouts blur this distinction. A researcher can build a company while maintaining research connections. An entrepreneur can lead a company while accessing cutting-edge research. This flexibility probably improves talent outcomes by allowing careers spanning both domains.

Finally, spinouts matter for Europe's future technology independence. In strategic sectors like semiconductors, quantum computing, and advanced materials, Europe needs indigenous technology companies building domestic capability. Spinouts, by definition, emerge from European research. They're building European technology. Supporting spinout ecosystems is one of the most direct ways Europe can build strategic technology independence in critical sectors.

The 2025 milestone of 76 spinouts reaching unicorn status or $100 million revenue isn't just a venture capital statistic. It's validation that this ecosystem is working, that Europe's research advantage is converting to economic value, and that the future of European tech innovation is increasingly driven by university spinouts building transformative companies from academic research. This transition from research-heavy, entrepreneurship-light economy toward a more balanced innovation ecosystem is arguably Europe's most important technology trend.

Key Takeaways

- 76 European university spinouts achieved 100M+ revenue in 2025, proving spinouts are reliable exit vehicles

- University spinouts raised $9.1 billion in 2025, nearly all-time high, while general European VC funding declined 50%

- Cambridge, Oxford, and ETH Zurich dominate but Nordic hubs like Technical University of Denmark are emerging as alternative spinout centers

- Nearly 50% of late-stage spinout funding now comes from American VCs, revealing capital flight risk and the need for European growth capital

- Quantum computing, biotech, and semiconductor spinouts dominate due to defensible research-based IP that creates competitive moats

![European Deep Tech Spinouts: How 76 University Companies Became Unicorns [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/european-deep-tech-spinouts-how-76-university-companies-beca/image-1-1767119821365.jpg)