How Mill Closed the Amazon and Whole Foods Deal: The Startup Strategy Behind a Food Waste Revolution

Matt Rogers didn't set out to change how America handles garbage. But somewhere between building the Nest thermostat at Google and founding Mill with Harry Tannenbaum, the problem of food waste started looking less like an environmental nuisance and more like a massive market opportunity.

That opportunity just got real. Mill announced it's deploying commercial-scale food waste bins in every Whole Foods store across the United States, with rollout beginning in 2027. This isn't a small pilot. This is Amazon and Whole Foods committing to a nationwide infrastructure shift, powered by a startup that most people have never heard of.

But here's what makes this deal interesting beyond the headlines: it's a masterclass in startup strategy. How you build a product, where you start, and how you think about revenue diversification can determine whether you end up with a footnote or a movement. Mill's journey from consumer gadget to enterprise solution tells us something important about what happens when you think like a platform builder instead of a product person.

The story starts at home. The company launched residential food waste bins that grind and dehydrate kitchen scraps. They're elegant. They work. Kids find them delightful. But Rogers and Tannenbaum always knew this was just the opening act. The real business was always upstream, in commercial kitchens, retail spaces, and eventually, municipalities. The Whole Foods deal represents that transition.

What sealed it? An AI system that can predict which food will spoil before it hits a customer's cart, as detailed in Axios.

The Consumer Foundation: Why Mill Started in Homes

Starting with consumers wasn't accidental for Mill. Rogers is deliberate about strategy, shaped by decades at Apple and Google. When you look at most startups that pivot from B2C to B2B, you see a pattern: they stumble into enterprise almost by accident, or they plan it poorly.

Mill did neither.

"Starting in consumer was very intentional because you build the proof points, you build the data, the brand, loyalty," Rogers explained. This statement matters because it reveals how Rogers thinks about business architecture. He didn't build a product and then ask, "Who might buy this?" He built a platform and strategically chose which market segment would validate it first.

Consumer hardware is brutal. You have to nail user experience, build manufacturing logistics, handle logistics and returns, and create a product that people actually want to use repeatedly. There's nowhere to hide. If your bins jam, if they smell, if the app is confusing, consumers will tell you immediately and leave you negative reviews on Amazon.

But that brutality creates something valuable: proof points. When Whole Foods executives walked into their own homes and saw Mill bins working quietly in kitchens, they weren't evaluating a Power Point deck. They were evaluating a product they'd lived with. They knew it worked. They understood what it did.

This is arguably the most underrated part of B2B sales strategy. Enterprise buyers want proof. They want to see the product working, ideally in their own environment or in someone they trust. The consumer market gave Mill that credibility.

Moreover, the consumer phase generated data. Every time someone puts food waste in a Mill bin, the company learns something. What foods rot fastest? What time of day do people use the product most? What patterns emerge across thousands of households? This data became part of the product moat. It trained the AI that would eventually sell the commercial version.

Rogers also understood brand building. Nest thermostats became status symbols in certain circles. People wanted them because they looked good and worked well. Mill cultivated a similar perception: this is a well-designed product for people who care. When you're pitching enterprise solutions later, you're not selling a strange startup. You're selling the company that made those elegant boxes people keep in their kitchens.

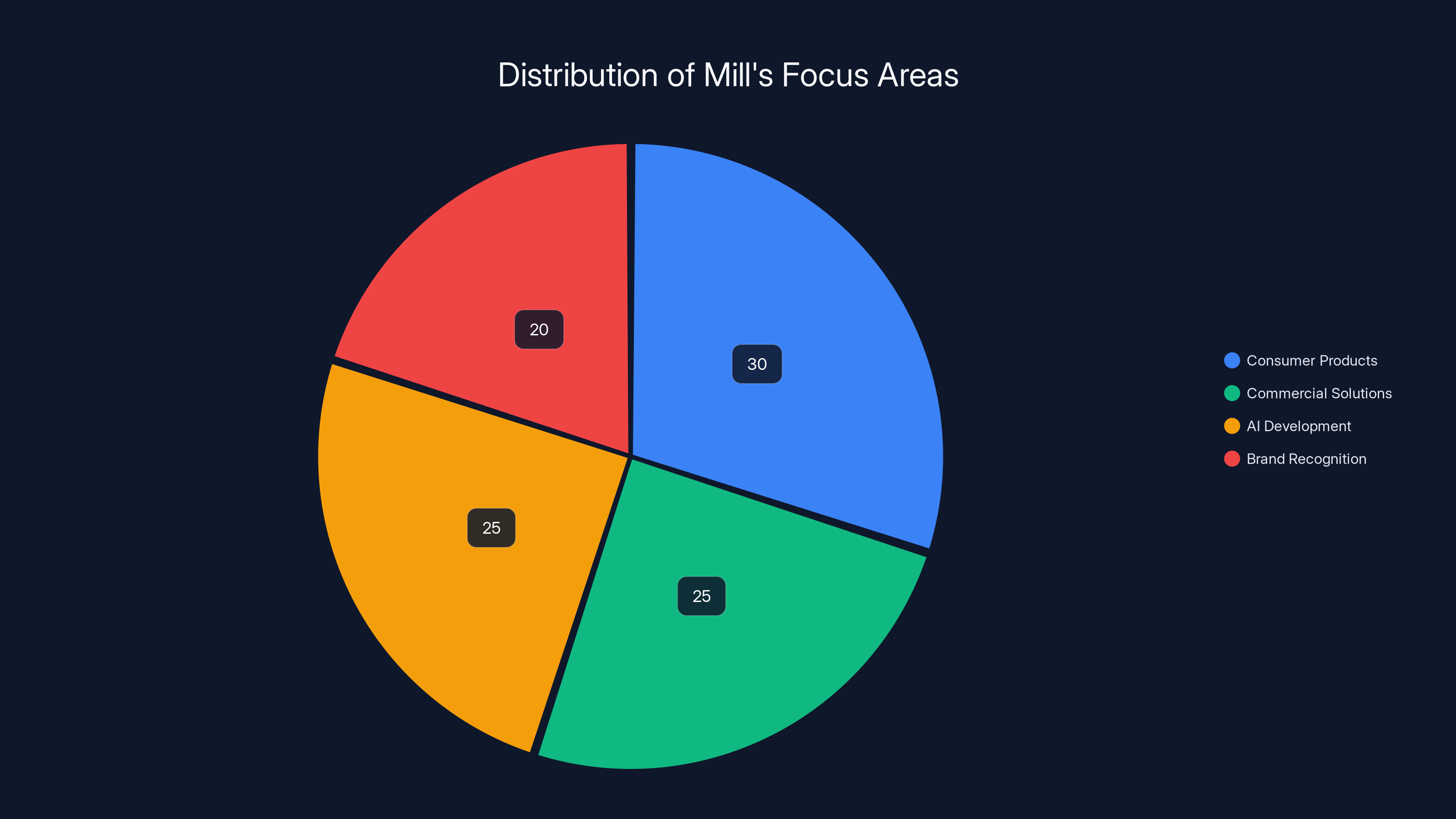

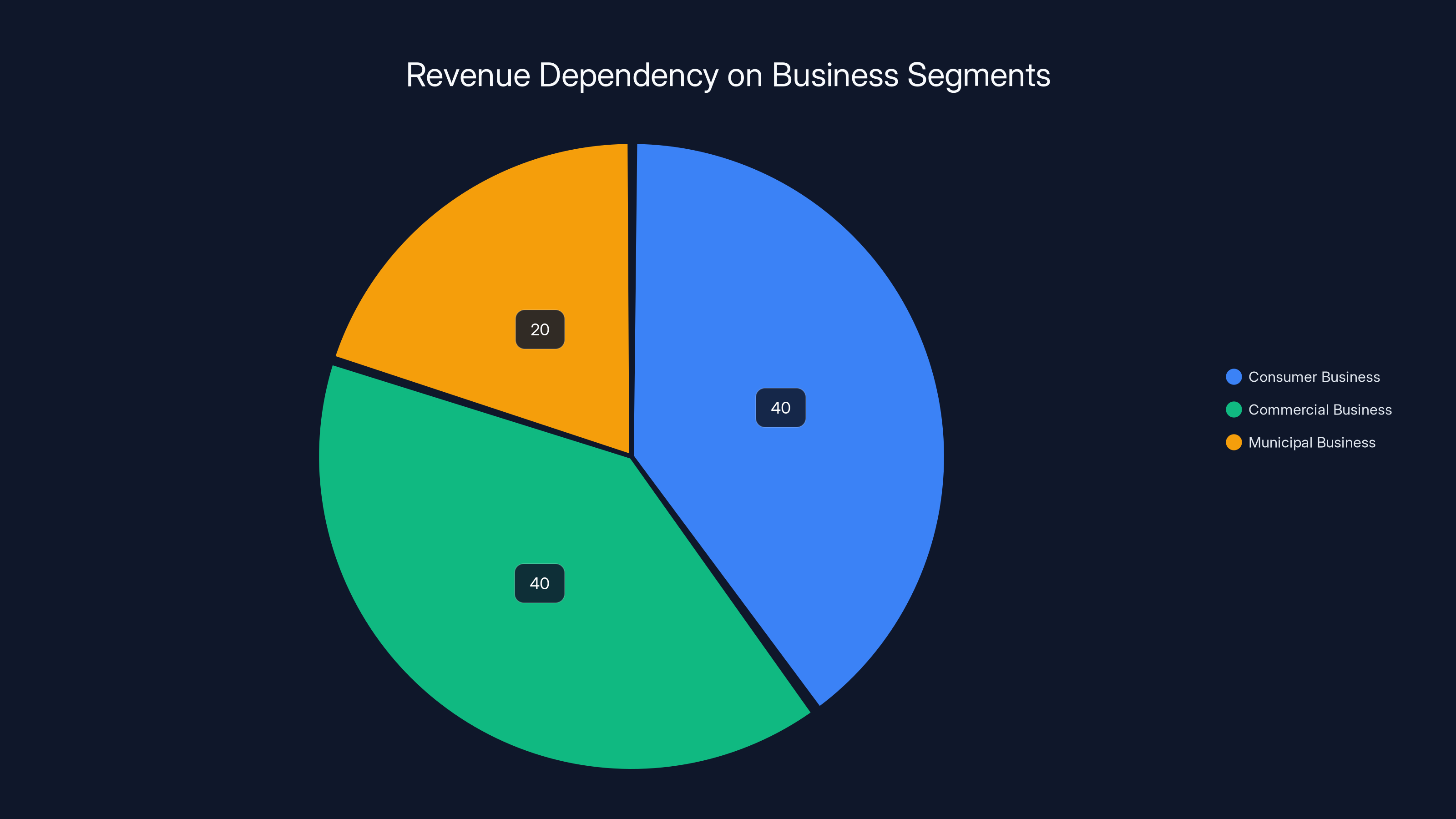

Mill's focus is distributed across consumer products, commercial solutions, AI development, and brand recognition. Estimated data based on content.

The Enterprise Sales Strategy: Turning Customers Into Advocates

Rogers had a realization at some point: if enough senior leaders at his target customers already owned Mill bins at home, selling them on a commercial solution becomes much easier.

"It's actually kind of our enterprise sales strategy," he said. "We have conversations with senior leadership at our various ideal customers, and if they haven't had Mill at home yet, we say, 'Hey, try Mill at home, see what your family thinks.' It is a surefire way of getting folks excited."

This is brilliant, and it's worth understanding why. Most enterprise sales processes are disconnected from actual user experience. A CTO or VP of Operations gets pitched on metrics and ROI. They evaluate spreadsheets and case studies. Sometimes they never actually use the product themselves before committing.

Mill inverted this. They seeded their target customers with consumer products first. Why would executives at Whole Foods care about food waste bins? Maybe they wouldn't have. But executives at Whole Foods who use Mill bins at home? They've already convinced themselves.

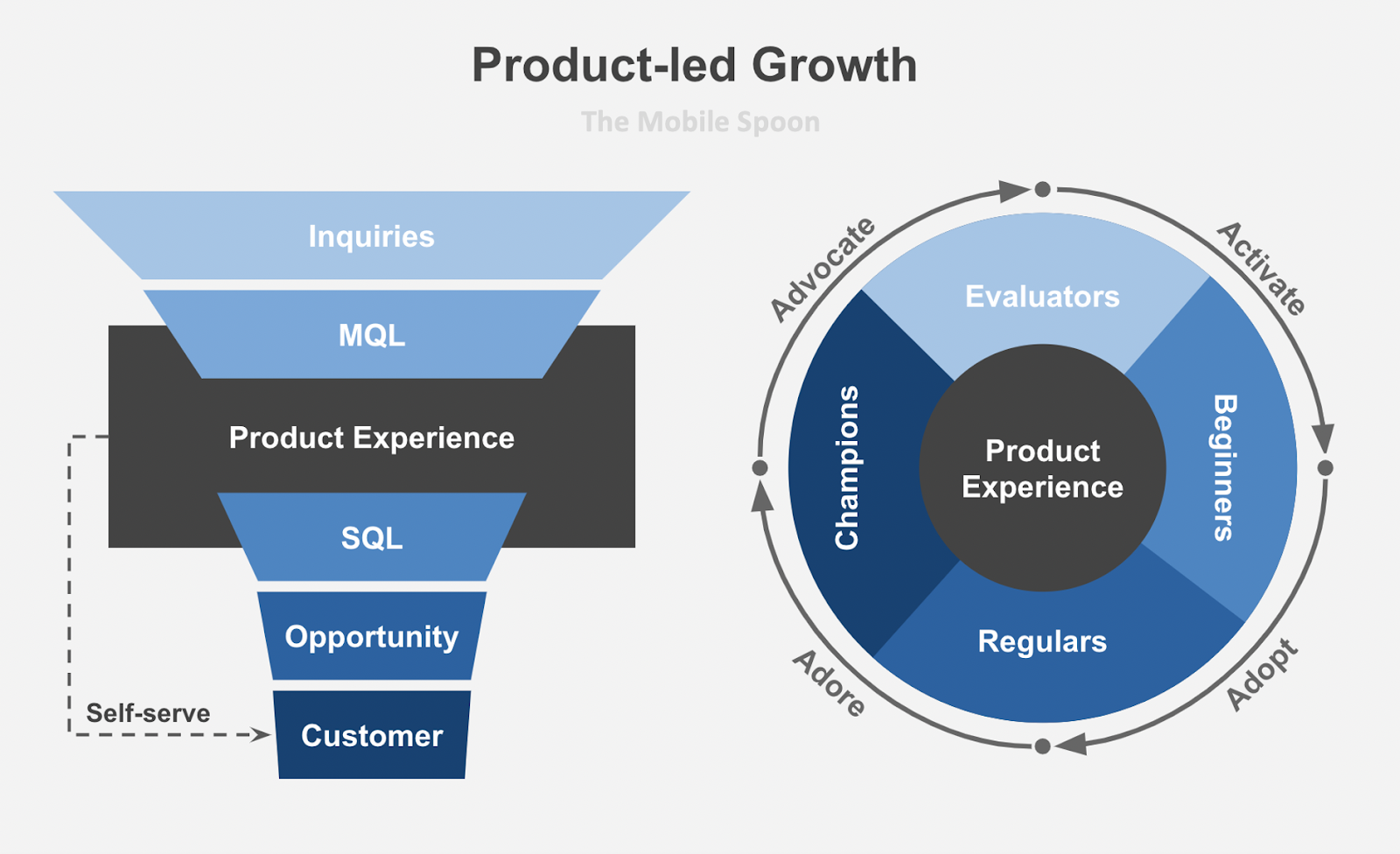

This approach has a name in venture capital circles: product-led growth meets enterprise sales. You're using the product itself as the sales engine.

The timeline tells the story. Mill began conversations with Whole Foods about a year before the deal became public. That's not a typical enterprise sales cycle. Most deals take 6-12 months. This one took longer because it wasn't just negotiation. It was product refinement based on feedback.

During this period, Whole Foods trialed the consumer version of Mill bins in some stores. The company wasn't just evaluating technology. They were testing logistics, learning about user adoption, and understanding the operational realities of deploying this hardware across hundreds of locations.

Mill used that feedback to build the commercial version. Every store has different layouts. Whole Foods produce departments have different configurations. The bin that works in someone's kitchen needs significant modification to work behind a grocery store counter where speed and efficiency are critical.

This is where most startups fail. They build a product for one market and try to force it into another. Mill did the opposite. They listened, iterated, and built the enterprise version with customer feedback baked in.

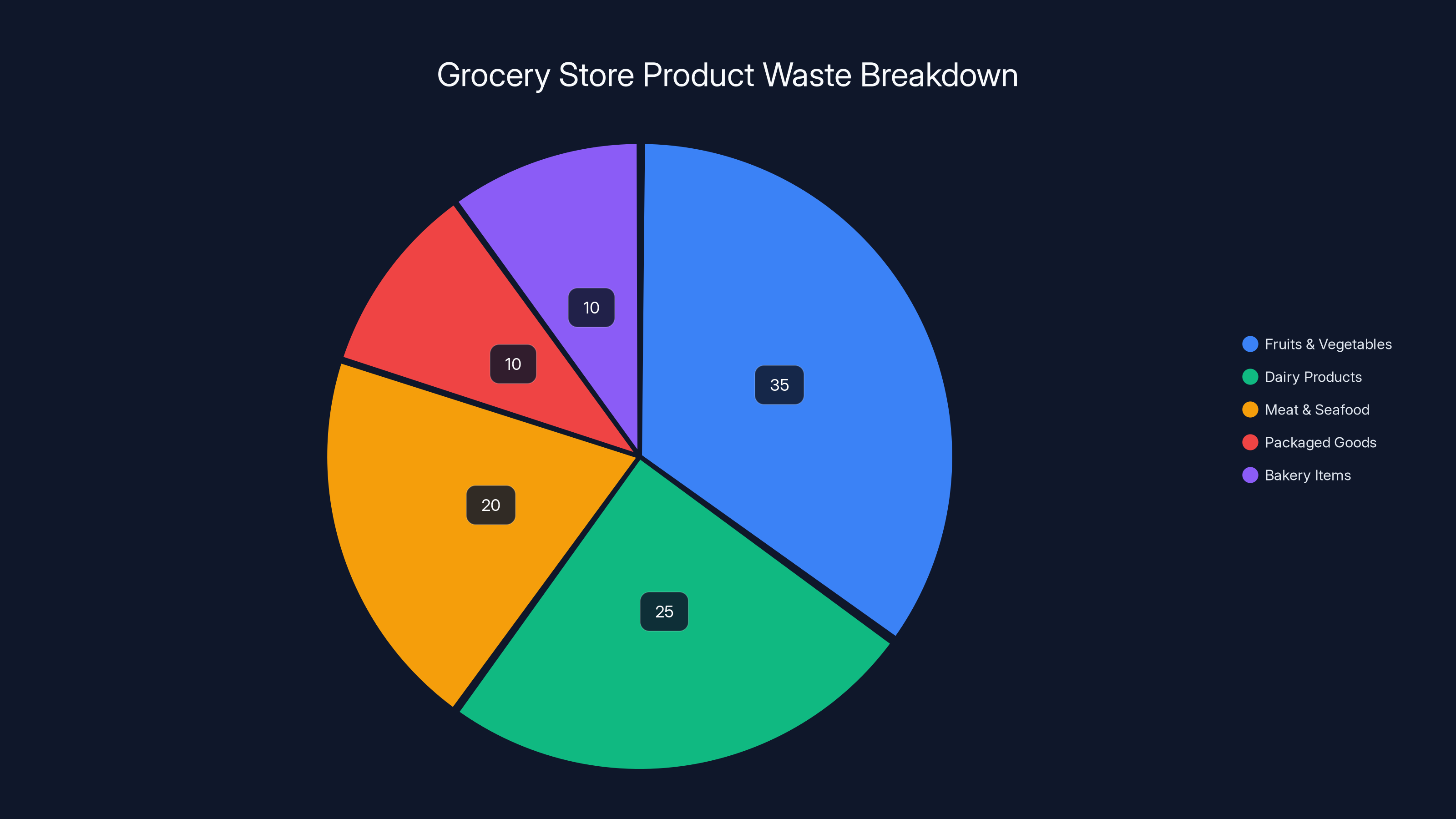

Estimated data shows that fruits and vegetables account for the largest portion of waste costs in grocery stores, followed by dairy products. Estimated data.

The AI Breakthrough: Shrinkage Prediction and the Race Against Spoilage

Here's where the story gets technically interesting. Mill built an AI system that can predict which food will spoil before it spoils.

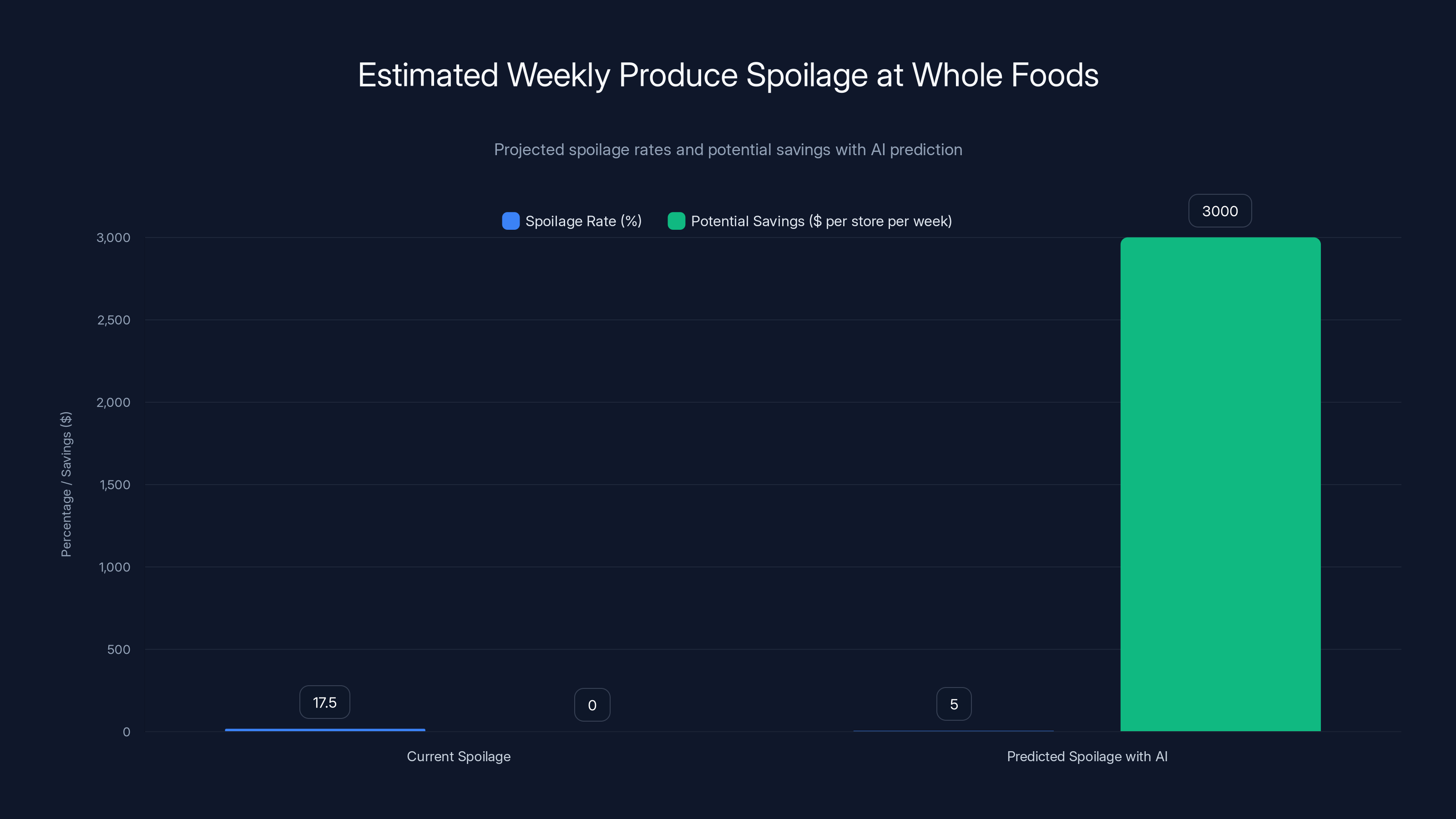

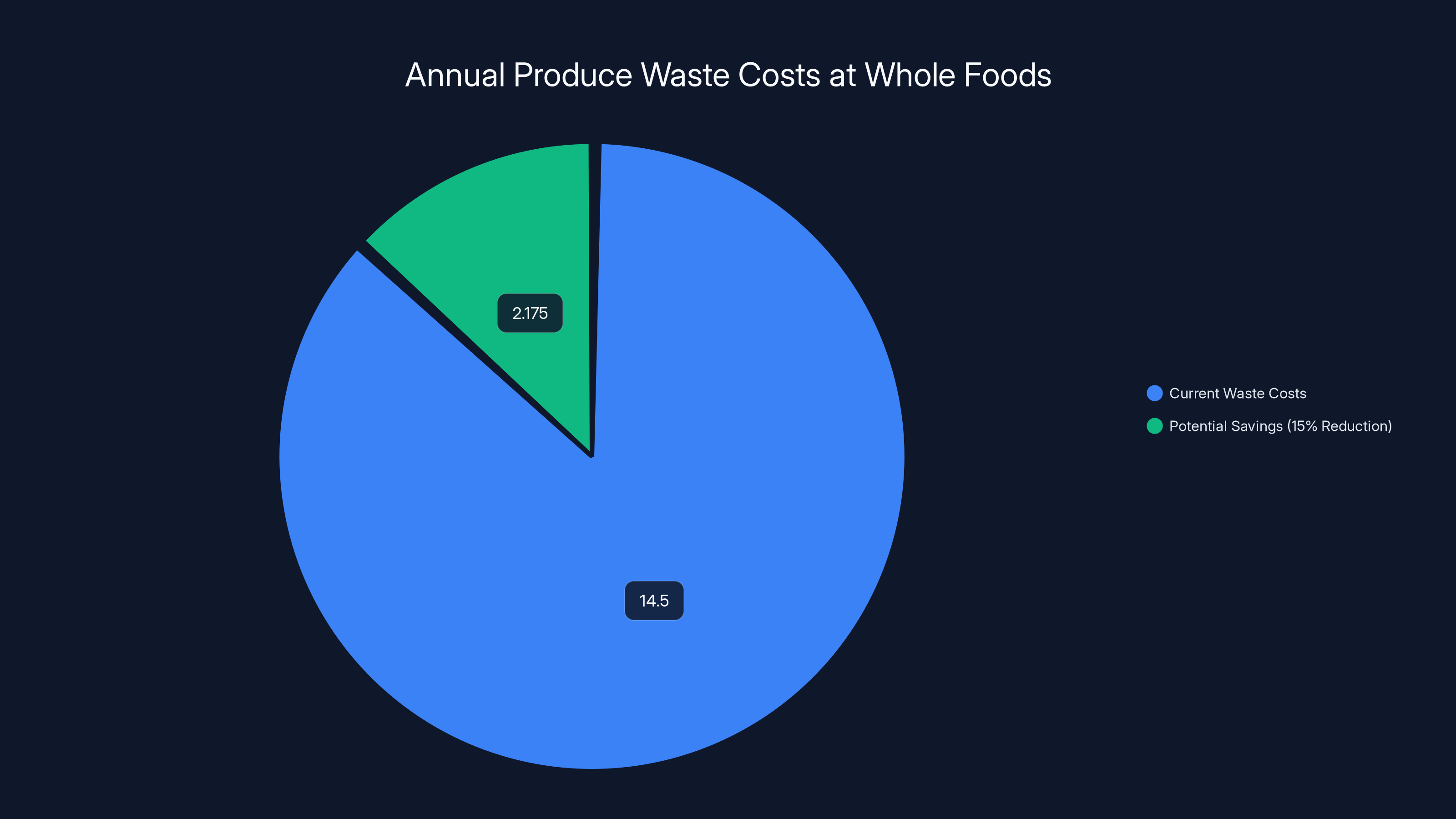

This matters enormously to grocery stores. The industry calls it "shrink," and it's massive. A single Whole Foods store might lose 15-20% of its produce to spoilage each week. That's thousands of dollars per location, per week, compounded across hundreds of stores nationwide.

If Mill's system could predict spoilage accurately, it could save Whole Foods millions of dollars annually. This wasn't about environmental responsibility anymore. This was about margin.

Rogers explained how AI made this possible. When Mill and Rogers built Nest Cameras at Google, teaching the system to recognize people and packages took dozens of engineers, a massive budget, and over a year of development. Computer vision was hard. You had to hand-code most of the logic. The machine learning models were brittle and required constant refinement.

Today, with large language models and transformer architectures, the same problem is tractable. Mill needed a handful of engineers and significantly less time to build a system that could analyze food images, sensor data, and historical patterns to predict spoilage.

The system works roughly like this: when food waste enters a Mill bin, cameras and sensors capture images and data about the items. The AI analyzes visual cues (color changes, texture, mold growth), weight and decomposition speed, and contextual information (how long the item sat, what type of produce it is). Using this data, the model can estimate whether that food should have been sold already.

Over thousands of transactions, the model learns patterns specific to each Whole Foods location. What spoils fastest in Texas might differ from what spoils fastest in New England. The system adapts.

But here's the clever part: this data flows upstream. Mill can analyze what's coming into waste bins across all Whole Foods stores and tell the company, "You're ordering too much of this item. It consistently spoils before customers buy it." This moves the needle from reactive waste management to proactive inventory optimization.

The technical achievement here is significant, but the business insight is more important. Rogers recognized that advances in large language models fundamentally changed the ROI calculation for this type of solution. It became possible to build something that actually solves a real problem at a price point that enterprise customers could justify.

Where waste savings might be calculated as:

For Whole Foods, this could mean hundreds of millions of dollars saved across their store network annually. That math makes the deal possible.

The Strategic Insight: Diversification Over Dependency

One of Rogers' most important reflections came from his time at Apple. He recalled the iPod era, when Apple was almost entirely dependent on iPod revenue. The iPod represented something like 70% of the company's total revenue.

That's a dangerous position. When your entire business depends on one product, you're one competitor away from irrelevance. Motorola was working on smartphones. If they'd gotten there first, if they'd done it well, Apple could have been crushed.

Steve Jobs recognized this and pushed hard on the iPhone project. Not because the iPhone was obviously going to be successful (it wasn't obvious at the time), but because Apple needed another leg of the stool.

Mill took this lesson seriously. The company is building three distinct business segments:

Consumer business: Mill bins for households. The addressable market is millions of homes across developed countries. Margins might be lower per unit, but volume and recurring revenue matter.

Commercial business: Grocery stores, restaurants, food service operations. This is where Whole Foods comes in. The TAM (total addressable market) is smaller per location, but the per-unit revenue and margin are significantly higher.

Municipal business: City waste management. This is nascent, but Rogers indicated the company is actively working on it. Municipalities have budgets for waste management and incentives to reduce landfill costs.

This diversification serves multiple purposes. It reduces dependency on any single customer or channel. It allows the company to monetize different aspects of the same technology. And it gives them flexibility in pricing and product development.

If Whole Foods represented 50% of revenue, the company would be fragile. If Whole Foods decided to build their own solution, or switched to a competitor, Mill would face an existential crisis. By building multiple legs, Mill creates resilience.

The U.S. food waste market is projected to grow from

Product Design and the Nest Legacy

There's something to be said for the fact that Rogers and Tannenbaum both come from Nest, which was later acquired by Google. Nest wasn't just a smart thermostat company. It was a design company that happened to make hardware.

The original Nest Thermostat was beautiful. It was a circle. It lit up when you approached it. It became the thing people wanted not because they desperately needed a smart thermostat, but because owning one signaled something: you cared about design, you were early to technology, you were the kind of person who upgraded their home.

Mill bins carry this DNA. They're not industrial-looking waste disposal units. They're designed objects. They have thoughtful touches. My kids found them fun to use, which tells you something important: the product experience is intentional, not accidental.

This matters for enterprise sales too. When Whole Foods executives see a Mill bin, they're not just seeing a functional object. They're seeing evidence of design thinking and product rigor. It signals that the team understands user experience, not just engineering.

In enterprise software, this is rare. Most B2B products have UX that feels like an afterthought. Mill took the consumer-first design philosophy and brought it to commercial hardware.

The Economics of Food Waste in Retail

Whole Foods is a high-end grocer. Their margins are tighter than other retailers in some categories, particularly produce. The cost to store fresh produce is high. Spoilage represents pure loss.

Here's the approximate economics:

- Average Whole Foods store: 40,000-60,000 square feet

- Produce section: 8,000-12,000 square feet

- Daily produce waste: 200-400 pounds

- Annual produce waste per store: 73,000-146,000 pounds

- Average produce margin: 25-35%

- Cost of waste per store annually: 40,000 (conservative estimate)

Across 500+ Whole Foods locations, that's

Add to this the logistics cost of hauling waste to landfills, the tipping fees (which vary by location but can be $50-100 per ton), and environmental compliance costs, and suddenly Mill's solution addresses multiple layers of economic pain.

But there's also a reputational component. Whole Foods and Amazon have positioned themselves as environmentally conscious companies. Visible waste reduction is a marketing asset. Being able to say, "We've reduced our produce waste by 20% through AI-powered optimization," is the kind of sustainability story that resonates with customers and investors.

Estimated data shows that AI prediction could reduce spoilage from 17.5% to 5%, potentially saving Whole Foods $3,000 per store weekly. Estimated data.

The Technical Stack: Sensors, Vision, and Real-Time Inference

Under the hood, Mill's commercial bin is a fairly sophisticated piece of hardware engineering. It needs to:

- Capture visual data: Multiple cameras at different angles to get a complete picture of what's being disposed of

- Collect sensor data: Weight, temperature, humidity, chemical composition (optional, advanced models)

- Process locally: The system can't rely on cloud connectivity. Stores need the bin to function even with poor internet

- Run inference: The AI model that predicts spoilage and categorizes waste runs on edge hardware inside the bin

- Aggregate data: Send useful insights back to Mill and Whole Foods without creating privacy or bandwidth issues

This is more complex than a consumer device. It's rugged hardware designed for commercial use, with uptime requirements that rival point-of-sale systems.

Rogers mentioned that advances in LLMs were crucial. This likely means Mill is using modern transformer-based architectures rather than hand-crafted computer vision pipelines. This has several advantages:

- Faster training: You can fine-tune a pre-trained vision transformer on Whole Foods-specific data much faster than training from scratch

- Robustness: Models trained on diverse data are less brittle. They handle edge cases better

- Adaptability: As Whole Foods introduces new products or seasons change produce mix, the model can adapt with relatively little new training data

- Explainability: You can ask the model why it made a particular decision, which matters for retail operations

The engineering here is solid, but it's not bleeding-edge in the way people usually think about AI startups. It's well-executed application of existing technology.

Market Timing and the Food Waste Opportunity

Mill's emergence and growth coincide with several converging trends:

Regulatory pressure: Many states and cities now mandate waste reduction and diversion from landfills. California requires 75% waste diversion by 2025. This creates artificial demand for waste management solutions.

Labor costs: Handling food waste is labor-intensive. It's sticky, smelly, and requires regular haulage. Automation appeals to retailers dealing with tight labor markets and rising wages.

AI capability: Five years ago, the spoilage prediction system Mill built would have been far more expensive to develop and run. Today, it's economical.

Sustainability marketing: The rise of ESG metrics and corporate sustainability goals creates internal demand for waste reduction solutions, even if the economic case is marginal.

Supply chain fragility: Recent years have highlighted supply chain vulnerabilities. Reducing waste and improving inventory visibility became strategic priorities for large retailers.

Mill surfed these waves skillfully. They weren't inventing the need. They were building a solution that happened to address multiple pain points simultaneously.

Estimated data shows a balanced revenue distribution strategy across consumer, commercial, and municipal segments, reducing dependency on any single source.

The Whole Foods Rollout: Complexity at Scale

Deploying a new piece of hardware across 500+ locations is not trivial. Whole Foods doesn't just flip a switch and install Mill bins everywhere. There's a carefully orchestrated process:

Phase 1 (2027-2028): Roll out to select regions and test operational integration. This is where Mill learns how their system works in actual retail environments.

Phase 2 (2028-2029): Expand to all stores, refining processes and training staff based on learnings from Phase 1.

Phase 3 (ongoing): Optimize the system, introduce new features, and expand into adjacent services.

Each store needs installation, staff training, integration with POS systems, and data pipeline setup. The logistics alone are substantial.

But for Mill, this is the opportunity. Once the system is live in hundreds of stores, they accumulate massive amounts of data about food waste patterns. That data becomes a competitive moat. A competitor entering the market would need to build similar models from scratch.

Moreover, each deployed unit becomes a recurring revenue stream. Mill likely has a service fee model where Whole Foods pays monthly for hardware, maintenance, and access to the data analytics platform.

The Amazon Influence: Capital and Credibility

Whole Foods is owned by Amazon. This changes the dynamics of the deal. Amazon has massive resources, sophisticated supply chain knowledge, and strategic interests in sustainability and automation.

Amazon's involvement provides multiple benefits to Mill:

- Capital: If needed, Amazon can provide growth capital without Mill having to fundraise at higher valuations

- Logistics network: Amazon's fulfillment and logistics network can potentially support Mill's distribution

- Data infrastructure: Amazon Web Services can support Mill's data processing and analytics

- Strategic alignment: Amazon's push toward carbon neutrality aligns with Mill's value proposition

- Future expansion: The Whole Foods deal might be the opening for broader Amazon logistics integration

Whole Foods also benefits from Amazon's analytics and optimization. Amazon is obsessive about metrics. They'll immediately start measuring the impact of Mill bins on spoilage rates, cost per pound, and operational efficiency.

This creates accountability but also opportunity. If the system works as promised, Amazon will want to scale it. If it works really well, they might want to deploy it across other business units.

Whole Foods incurs approximately

Building Revenue Streams Beyond the Deal

The Whole Foods deal is significant, but Rogers is clear that Mill isn't building a single-customer business. They're building a platform with multiple revenue streams.

Hardware sales: Selling bins to retail chains, restaurants, and institutions

Service revenue: Monthly fees for data analytics, optimization recommendations, and system maintenance

Data licensing: Anonymized insights about food waste patterns, supply chain optimization, and demand forecasting

Feed sales: The food waste becomes feed for egg producers and other livestock operations, creating revenue from the material itself

Carbon credits: As regulatory frameworks evolve, diverting waste from landfills generates carbon credits that can be monetized

This multi-leg approach means that even if hardware margins compress (as often happens in manufacturing), the company has other ways to grow revenue per unit.

Consider this simplified model:

- Bin hardware: $15,000 one-time

- Monthly service fee: $500-1,000 per location

- Data licensing (per store): $200-500 monthly

- Feed material value: $50-200 per ton

For a chain with 500 locations, this could represent $3-6 million in annual recurring revenue, plus millions more in one-time hardware sales.

The Competitive Landscape and Why Mill Wins

Mill isn't operating in a vacuum. There are other companies working on food waste, sustainability, and waste management. But Mill has several advantages:

Brand recognition: They're known for the consumer product. When enterprise customers think of food waste solutions, Mill comes to mind first.

Technical capability: The AI system isn't commodity. It's a competitive advantage built on years of consumer data and feedback.

Pedigree: Rogers and Tannenbaum come from Nest, which gives them credibility in hardware and design.

Capital: They've raised venture funding and clearly have the resources to execute at scale.

Focus: While other companies chase multiple sustainability angles, Mill is hyper-focused on food waste.

The competitive advantage isn't unassailable. A well-funded competitor with AI expertise could replicate the core technology. But they'd need to rebuild the brand, accumulate the data, and convince enterprise customers. That takes years.

Mill has time. The Whole Foods deal buys them runway and cash flow to expand before serious competition arrives.

Lessons for Other Hardware Startups

Mill's path offers lessons for any hardware startup trying to scale:

1. Start small and deliberate: Mill started in consumer because it made sense strategically, not because it was easy. The consumer market validated the concept and built the data foundation.

2. Plan for scale from the beginning: Rogers and Tannenbaum weren't opportunists who stumbled into enterprise. They planned a B2C foundation that would eventually support B2B scale.

3. Use product as the sales tool: Instead of chasing enterprise deals with salespeople, Mill seeded their target customers with consumer products. The product sold itself.

4. Build multiple revenue streams: Depending on one customer or channel is fragile. Mill built commercial, consumer, and municipal businesses to reduce risk.

5. Leverage advances in AI and ML: Rogers was explicit that modern LLMs made their AI capabilities economical. Hardware startups need to think about what becomes possible with new AI techniques.

6. Design matters: Coming from Nest, Rogers understood that industrial design and user experience aren't luxuries. They're part of the product value proposition.

7. Recruit the right people: Having founders with Google and Nest backgrounds gives them credibility and deep product knowledge. Who you hire shapes what you can build.

The Path to Profitability and Scale

Mill is still private. We don't know their exact revenue or profitability. But we can estimate the unit economics:

If Whole Foods represents 500 stores at

For the company to be valuable (beyond the enterprise value already created by the Whole Foods deal), they need to prove they can scale beyond Whole Foods without depending on Amazon/Whole Foods indefinitely.

This is where the municipal business comes in. Cities and municipalities are increasingly focused on waste reduction. If Mill can land major city contracts, they unlock a different customer profile with longer contracts and less price sensitivity.

Consumer business, meanwhile, generates data and brand value that subsidizes the commercial expansion. It's a flywheel: consumer revenue funds growth, consumer data improves the commercial product, commercial success funds consumer marketing.

The Bigger Picture: Food Waste as Infrastructure

Step back and the Whole Foods deal looks like something bigger than a single customer win. It looks like the beginning of a new infrastructure category.

Right now, food waste is handled by sanitation companies. It's a cost center, not a strategic asset. Whole Foods dumped hundreds of thousands of pounds of produce weekly into trucks that took it to landfills. It was invisible.

Mill is making food waste visible, measurable, and optimizable. They're treating it as data, not garbage.

If this approach scales (which the Whole Foods deal suggests it will), food waste becomes something different. It becomes a category like "inventory optimization" or "supply chain analytics." It becomes a line item on retail balance sheets, tracked and managed like every other input.

This is how infrastructure gets built. Someone identifies a massive inefficiency. They build a tool to address it. The tool catches on. Suddenly what was invisible becomes standard practice.

Mill is trying to be that infrastructure. The Whole Foods deal is the proof of concept.

Looking Ahead: The Next Frontier

Rogers indicated that Mill is working on municipal waste management. This is interesting because municipalities represent a different customer profile with different incentives.

A grocery store cares about reducing costs. A city cares about diverting waste from landfills, reducing environmental impact, and managing budgets. The sales process is different. The regulatory environment is different. The data they care about is different.

But the underlying technology is the same. If Mill can prove the system works at scale in municipal waste facilities, that's a dramatically larger market. Every city in the developed world manages food waste. Even a small percentage of adoption would be transformative.

The consumer business will likely remain, but it becomes a lead generation tool and data source rather than the primary revenue driver. The commercial and municipal businesses are where the scale is.

Rogers' references to "building legs on the stool" and the iPod strategy suggest he's thinking 10 years out, not 3 years. This isn't a company optimizing for Series D valuation. This is a company building to last.

The Verdict: What This Deal Means

The Whole Foods agreement is significant for three reasons:

First, it's economically real. This isn't a pilot or a gesture toward sustainability. This is Amazon and Whole Foods committing resources to deploy hardware across hundreds of locations. That commitment wouldn't happen unless the ROI math was solid.

Second, it validates the strategy. Mill proved that starting in consumer, building brand, accumulating data, and transitioning to enterprise works. Other hardware startups will study this playbook.

Third, it establishes infrastructure. Once these bins are live and generating data, Mill has created a network effect. They know how food waste patterns differ by region, season, and store type. That knowledge becomes an advantage in the next market they enter.

For Mill, this deal probably represents a 5-10x jump in valuation. But more importantly, it represents a shift from "promising startup" to "enterprise infrastructure company." That's worth far more than the valuation bump.

Rogers and Tannenbaum haven't made it yet. They still need to prove they can execute at scale, maintain customer satisfaction, and grow profitably. But they've cleared a massive hurdle. They've landed the kind of enterprise customer that changes everything.

Final Thoughts: Patience as Strategy

One thing stands out about Mill's path: the company was willing to wait. They built the consumer product first even though it meant slower revenue growth. They took time to iterate with Whole Foods even though they probably could have closed a quicker deal with a less demanding customer.

This patience paid off. Instead of building a business around a single customer who might become a source of dependency, they built a business where that customer is one leg of a diversified revenue stream.

In the startup world, we celebrate speed. Move fast, break things, iterate quickly. But Mill's story suggests that sometimes, the right move is to build slowly, build carefully, and build with an eye toward the long term.

The Whole Foods deal is impressive. But what's more impressive is the clarity of vision that led to it.

FAQ

What is Mill and what problem does it solve?

Mill is a food waste management startup that develops AI-powered bins for both consumer and commercial use. The company's core mission is to reduce food waste by grinding and dehydrating organic matter, while using artificial intelligence to predict food spoilage before it happens. In commercial settings like Whole Foods, Mill bins analyze which produce items should have been sold before they were discarded, helping retailers optimize inventory and reduce waste-related losses.

How does Mill's AI spoilage prediction system work?

Mill's system uses multiple sensors and cameras inside the commercial bins to capture visual and physical data about food being disposed of. Machine learning models trained on years of consumer data analyze this information to estimate whether food items spoiled prematurely. The system learns location-specific patterns about which produce types spoil fastest in different regions and seasons, then feeds this intelligence back to retailers to help them order more accurately and reduce waste. The development of large language models made this approach economically viable because it dramatically reduced the time and engineering resources needed to train effective computer vision systems.

Why did Mill start with consumer products before moving to commercial solutions?

Mill co-founder Matt Rogers made a deliberate strategic choice to begin with household bins rather than going straight to enterprise. This approach built proof points that could convince enterprise customers, generated valuable data from thousands of households to train AI models, established brand recognition and consumer loyalty, and created a pool of executives at target companies who personally owned Mill bins and could advocate internally. Starting in consumer essentially created organic demand that made closing enterprise deals like Whole Foods significantly easier.

What economic impact does the Whole Foods deal represent for Mill?

Whole Foods stores waste an estimated

How does Mill's business model create diversification and reduce risk?

Rogers was explicit about learning from his Apple experience, where iPod revenue represented 70% of company income, creating dangerous dependency. Mill deliberately built three distinct business segments: consumer hardware, commercial installation, and municipal waste management. This diversification means the company isn't fragile if any single customer relationship changes, allows monetization of the same technology in different markets with different margins, and provides flexibility to invest in new opportunities without threatening core business.

What competitive advantages does Mill have in the food waste management market?

Mill benefits from several defensible advantages: established brand recognition from the consumer product, years of accumulated data about food waste patterns that inform AI model training, hardware and design expertise from founders' Google Nest background, sufficient venture capital to execute at scale, and intense focus on food waste rather than scattered sustainability efforts. While a competitor could theoretically replicate the core technology, rebuilding brand, accumulating comparable data, and convincing enterprise customers takes years, giving Mill significant lead time.

How might the Amazon and Whole Foods ownership structure affect Mill's future?

While Whole Foods is owned by Amazon, this relationship creates multiple advantages for Mill: access to Amazon's capital and logistics infrastructure, potential integration with AWS for data processing, alignment with Amazon's carbon neutrality goals, and the possibility that a successful Whole Foods deployment could lead to expansion into other Amazon business units. The relationship provides credibility and resources but also means that Mill must continue proving value to a sophisticated, metrics-driven owner like Amazon.

What is Mill's path to profitability and long-term sustainability?

Based on available information, Mill generates revenue through hardware sales (estimated

Why is food waste infrastructure becoming increasingly important to major retailers?

Multiple forces converge to make food waste a strategic concern: state and local regulations now mandate waste diversion rates (California requires 75% by 2025), labor costs for waste handling continue rising, AI capability now enables economical predictive systems, corporate sustainability goals and ESG metrics create internal demand for visible waste reduction, and recent supply chain fragility has made waste reduction and inventory visibility strategic priorities. Mill's solution addresses all these concerns simultaneously, making adoption attractive even before considering unit economics.

What lessons from Mill's strategy could apply to other hardware startups?

Mill demonstrates several reproducible principles: starting deliberately in a specific market segment that builds long-term advantages, planning for scale to multiple customer types from the beginning rather than pivoting reactively, using product excellence as the primary sales tool rather than relying on salespeople, building multiple revenue streams to reduce dependency on single customers, leveraging advances in AI and ML to make previously uneconomical applications viable, understanding that industrial design and user experience are competitive advantages, and hiring founders and teams with deep expertise in adjacent domains. Rogers' explicit references to learning from his Apple and Nest experience suggest that domain expertise and clear long-term vision matter as much as execution speed.

Key Takeaways

- Mill's strategic pivot from consumer to enterprise markets was deliberately planned from Series A, not opportunistic

- Starting in consumer hardware built proof points, accumulated AI training data, and established brand recognition that made enterprise sales easier

- AI advances in large language models reduced the engineering effort for spoilage prediction from Google-scale resources to a small team

- Whole Foods deal addresses $9-20 million annual waste across 500+ locations, creating clear ROI within months

- Deliberate business diversification across consumer, commercial, and municipal segments prevents dangerous customer dependency

Related Articles

- Quordle Hints & Answers Today: Strategy Guide [2025]

- NYT Connections: Complete Hints, Answers & Winning Strategy [2025]

- NYT Strands Hints & Answers for Thursday, December 25 [2025]

- Apple Pauses Texas App Store Changes After Age Verification Court Block [2025]

- How Much RAM Do You Actually Need? A 2025 Deep Dive [2025]

- JBL Bar 500MK2 Soundbar Review: Compact Atmos Power [2025]

![How Mill Closed the Amazon and Whole Foods Deal [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-mill-closed-the-amazon-and-whole-foods-deal-2025/image-1-1766592728289.jpg)