The FCC's Unexpected Challenge to Late-Night Entertainment

January 2025 brought a surprising regulatory shift that caught the media world off guard. The Federal Communications Commission issued guidance suggesting that long-protected late-night and daytime talk shows may no longer automatically qualify for exemptions under broadcast television's equal-time rule. If you've been watching cable news, you probably caught headlines about this. But the real story is far more nuanced, with implications that stretch well beyond which political candidates get airtime on Jimmy Kimmel.

Here's what's actually happening: For decades, shows like The Tonight Show, The View, and Late Show have operated under the assumption that they're exempt from the FCC's equal-time requirements because they're considered bona fide news programming. The equal-time rule itself is straightforward in principle. When a broadcast station gives airtime to one political candidate, it must provide comparable time to opposing candidates who request it. It's a fairness doctrine descendant designed to prevent broadcasters from using the public's airwaves to unfairly promote one candidate over another.

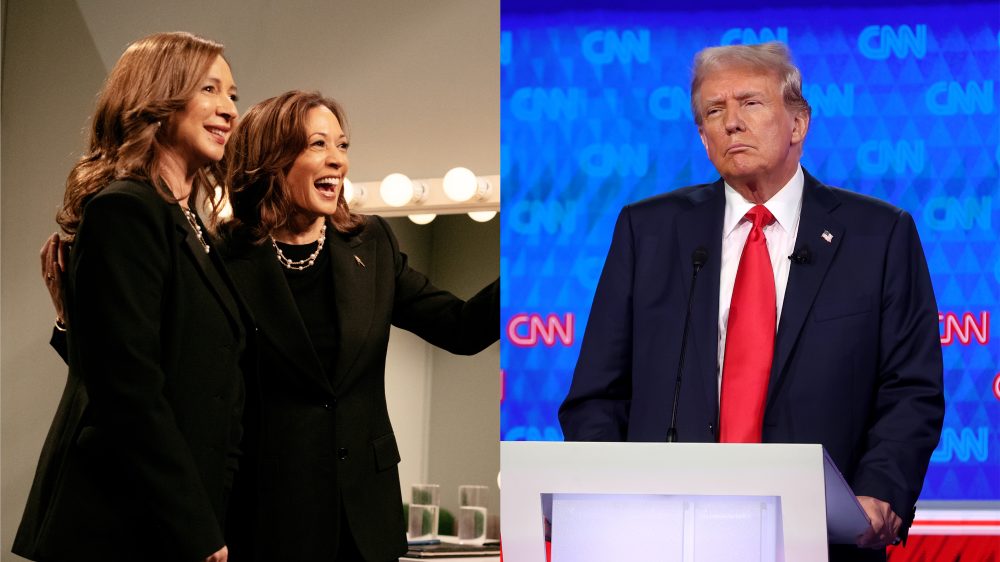

But here's where the nuance enters. Entertainment talk shows have historically been treated differently than hard news broadcasts. A 2006 FCC decision specifically exempted The Tonight Show with Jay Leno's interview segment from equal-time requirements. Everyone from the networks to the FCC itself treated this as settled law for nearly two decades. Then Brendan Carr took over as FCC chair in the Trump administration, and the ground shifted.

The FCC's January 2025 public notice doesn't directly ban talk shows from the exemption. Instead, it casts doubt on the 2006 ruling and essentially tells broadcasters they can no longer assume their interview shows qualify for the exemption. If a station wants protection from equal-time requirements, it now needs to file a petition with the FCC and prove its show deserves the exemption. This shift represents a significant regulatory reinterpretation that could force major changes in how networks book guests.

The practical impact is potentially enormous. Talk shows are built on editorial discretion. Producers book guests because they're newsworthy, entertaining, controversial, or relevant to current events. Under strict equal-time enforcement, a show that books a Republican candidate for an extended interview could face pressure to book opposing Democratic candidates with similar prominence. This logic extends beyond candidates to controversial figures, activists, and political personalities who might benefit from airtime.

Understanding the Equal-Time Rule and Its Long History

The equal-time rule didn't emerge from nowhere. It's rooted in the idea that broadcast spectrum is a finite public resource, and the FCC grants licenses to use it with specific obligations attached. Congress decided that broadcast stations shouldn't be allowed to use this public resource to unfairly promote certain political candidates over others.

The rule itself, formally called the Equal Opportunities Rule, applies specifically to radio and television broadcast stations. Cable networks like CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News don't have to follow it because they don't use public spectrum in the traditional sense. This is a critical distinction that many people miss. MSNBC can book left-leaning guests all day long without violating equal-time rules. HBO can do the same. But ABC, NBC, and CBS broadcast stations are bound by these restrictions.

When a station gives a political candidate broadcast time, the rule requires the station to make comparable time available to opposing candidates. The key word is comparable. It's not about exact minutes or identical placement. A candidate who appears at 8 PM doesn't necessarily get another 8 PM slot. But the time should be reasonably similar in terms of reach and audience size.

There's an important distinction between candidates and other political figures. The rule applies to legally qualified candidates for public office. That means someone running for president, governor, or city council is covered. Political commentators, partisan figures, and activists who aren't running for office operate in a grayer area. The rule is specifically about candidate elections, not about balancing overall political viewpoints on air.

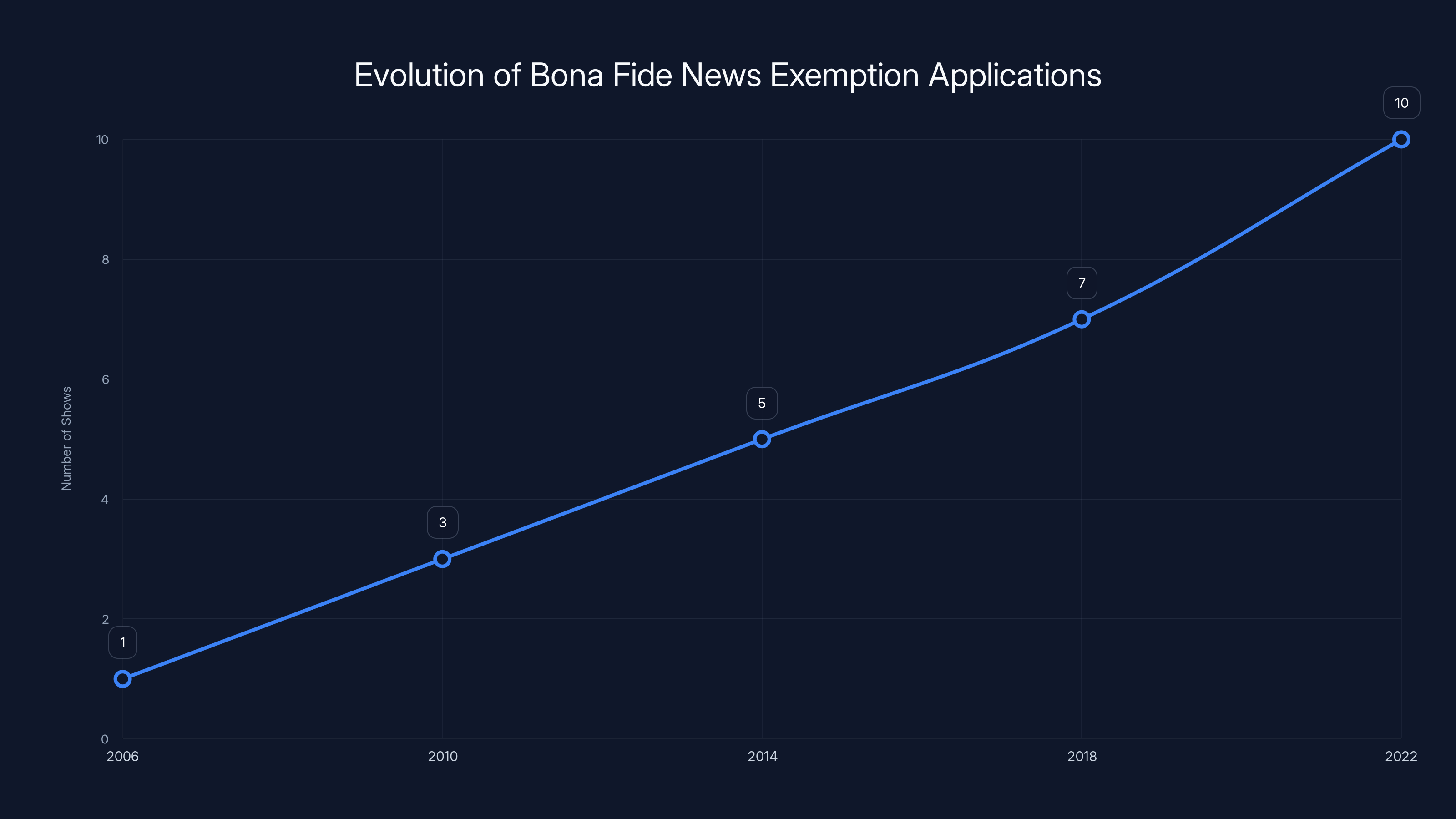

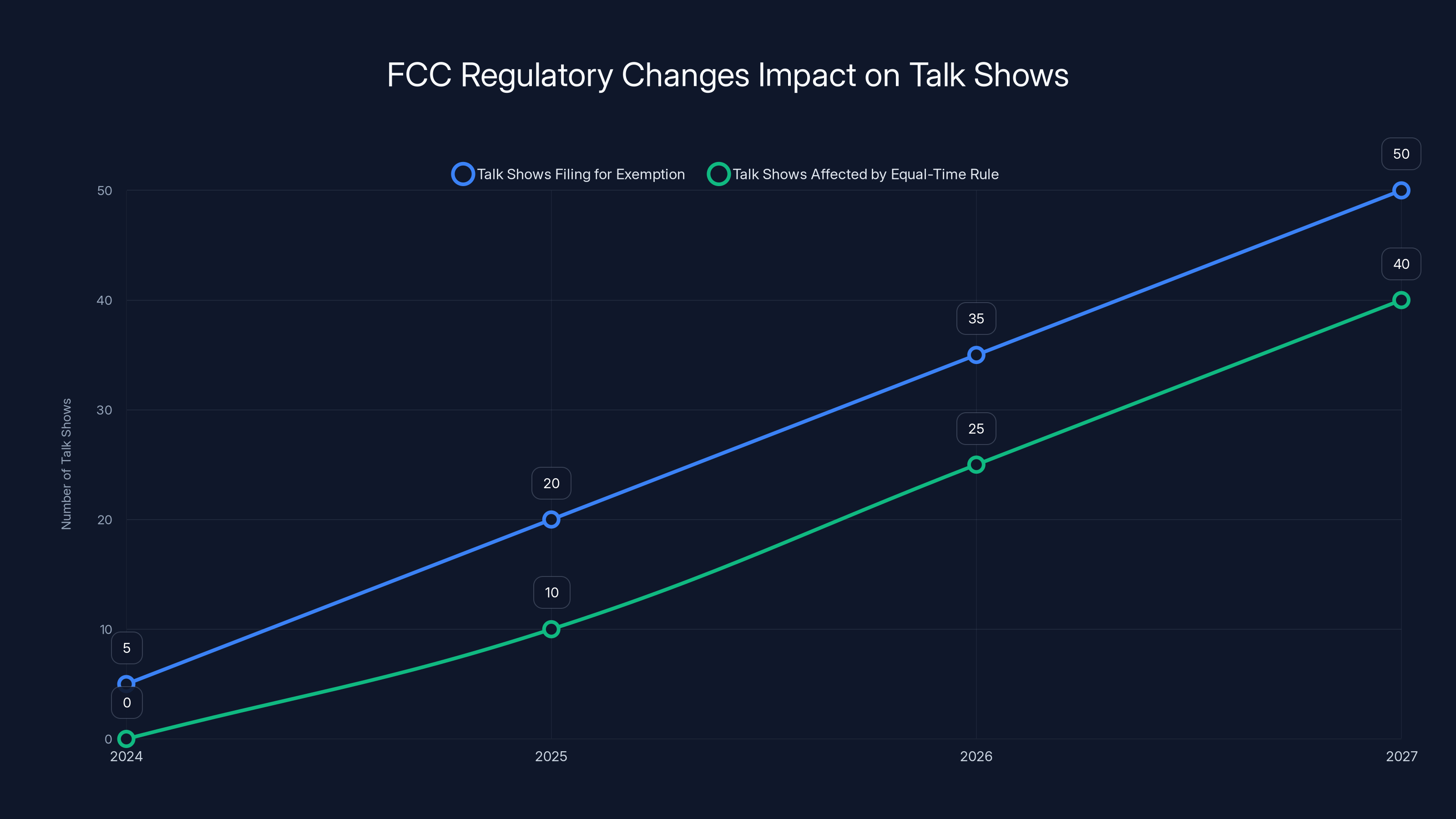

The application of the bona fide news exemption expanded from 2006 to 2022, with more shows qualifying over time. (Estimated data)

The Bona Fide News Exemption That Changed Everything

Here's where the whole situation gets interesting. The FCC recognized from the beginning that applying strict equal-time rules to all broadcast content would be paralyzing. If every political reference triggered equal-time obligations, newsrooms couldn't function. A news anchor couldn't report that a candidate committed a crime without booking the candidate to respond. News programming would grind to a halt under that interpretation.

So the FCC created an exemption. Appearances by candidates on bona fide newscasts, news interview programs, certain news documentaries, and coverage of bona fide news events are exempt from equal-time requirements. This exemption has been the industry standard for decades.

Bona fide is the key word here. It's a legal term of art that means genuine or legitimate. The FCC's 2022 guidance explained that bona fide news programs are distinguished by their purpose. They're created to inform the public about news and current events. The programming decisions are made based on newsworthiness, not political favoritism.

In 2006, the FCC's Media Bureau made a specific ruling about The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. The bureau determined that the interview portion of the show qualified for the bona fide news exemption. This wasn't a blanket ruling applying to all talk shows. It was specific to how Leno's show operated. The show regularly interviewed newsworthy figures and public officials. The interview segment served an informational purpose. Based on that analysis, the show qualified for the exemption.

For nearly 20 years, the industry interpreted this decision as establishing a precedent. If The Tonight Show qualified, then logically The Late Show, Late Night with Seth Meyers, The View, and similar programs would also qualify. Networks operated under this assumption. The FCC didn't challenge it. Candidates and their campaigns worked within this framework.

Then everything changed. In September 2024, Brendan Carr, the new FCC chair, publicly questioned whether shows like The View should qualify for the exemption. He suggested that entertainment programming might not meet the bona fide news standard. This was more than casual commentary. It was a signal that the FCC was reconsidering the established framework.

The January 2025 FCC Guidance and Its Ambiguities

The FCC's January 2025 public notice is carefully worded, and that careful wording matters. The agency doesn't say talk shows are banned from the exemption. It doesn't formally overturn the 2006 decision. Instead, the notice says something more insidious: the FCC has not been presented with evidence that any currently airing late-night or daytime talk show qualifies for the exemption.

This language is significant. It essentially invalidates two decades of industry practice without formally changing the rules. The FCC is claiming that the 2006 decision was always narrow and fact-specific. Each show has to prove its own qualification. The industry's interpretation that established a precedent was incorrect. Networks now operate under uncertainty.

The notice encourages programs and stations to file petitions if they want formal assurance that equal-time requirements don't apply to them. This puts the burden on broadcasters to prove their shows deserve exemptions. Networks would have to justify why their programs qualify as bona fide news despite their entertainment focus.

Here's where things get genuinely complicated. The FCC's definition of bona fide news programming is inherently subjective. Yes, news judgment should be based on newsworthiness. But what makes something newsworthy is never perfectly clear. A comedy bit about a politician is that news? Is it entertainment? Is it both?

The View, for example, blends news discussion with lifestyle topics and entertainment. The show books politicians for interviews, but it also books celebrities, authors, and activists. Is that bona fide news programming? A reasonable person could argue either way. Late-night shows include comedy monologues about political news alongside interviews with newsmakers. Are they primarily news or entertainment?

These gray areas suggest that the FCC's new approach will require case-by-case determinations. Networks won't know for certain whether their shows qualify unless the FCC reviews them. This creates regulatory uncertainty that could influence editorial decisions.

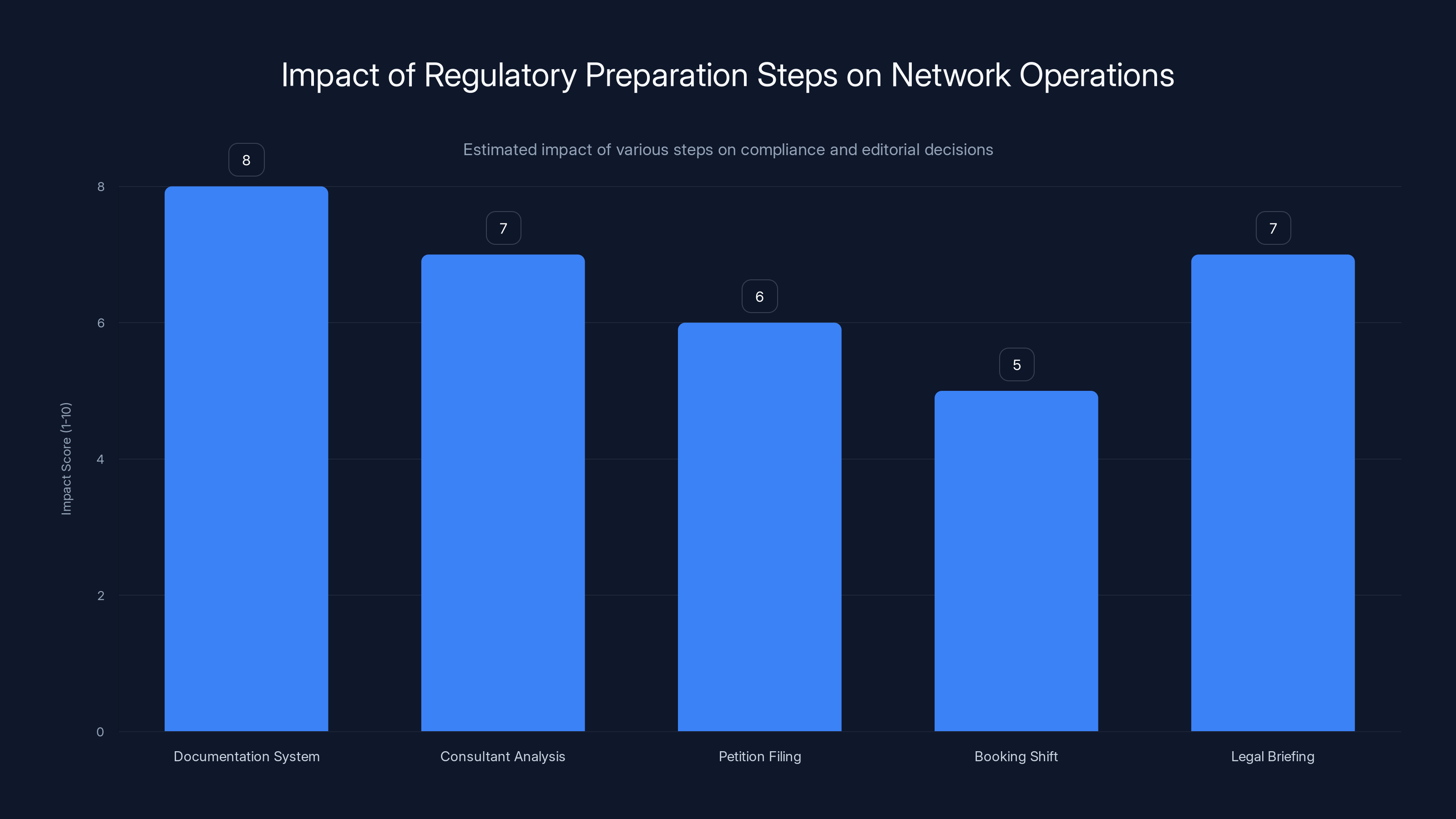

Estimated data suggests that creating a documentation system and legal briefings have the highest impact on compliance and editorial decisions, with scores of 8 and 7 respectively.

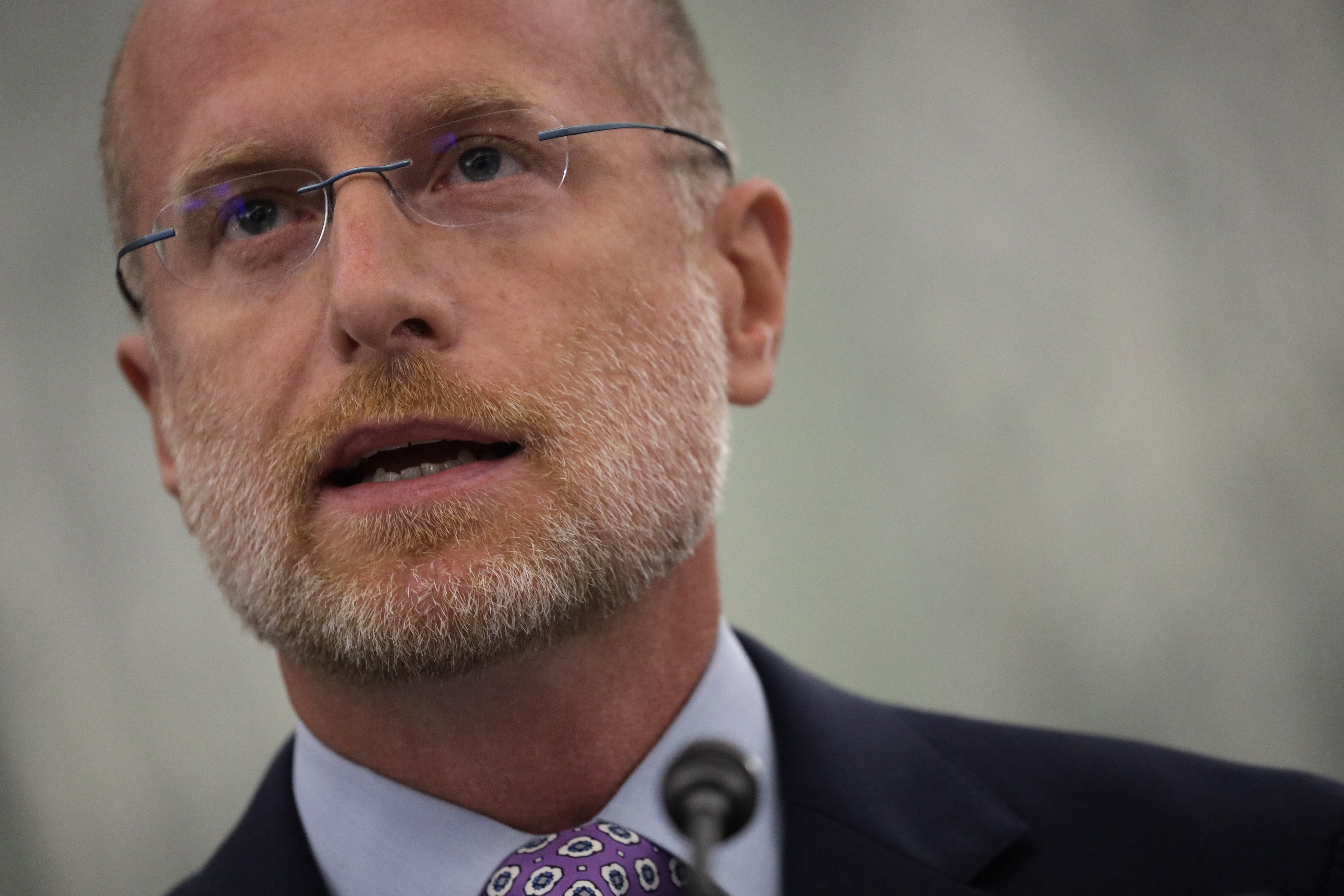

Why Brendan Carr's Leadership Matters to This Story

Understanding Brendan Carr is crucial to understanding why this regulatory shift happened. Carr was appointed as FCC chair by Trump in 2024, and he brought a specific ideological orientation to the position. He's a vocal critic of what he describes as liberal bias in mainstream media. He's publicly stated that the FCC has been too passive in addressing what he views as unfair partisan content on broadcast television.

Before becoming chair, Carr had already pressured broadcasters on political programming issues. He threatened ABC's The View with equal-time rule enforcement and called for Jimmy Kimmel's suspension over comedy segments. These weren't idle comments. They were public demonstrations of his willingness to use FCC authority as a lever to influence content decisions.

Carr has also been characterized as undermining the FCC's traditional independence from the White House. The commission has historically maintained a degree of autonomy from political pressure. Career staff members made determinations based on regulatory law and precedent, not political loyalty. Carr's approach has been more directly aligned with the administration's policy goals.

The equal-time rule guidance appears to fit this pattern. Conservative groups have long complained about what they describe as liberal bias in late-night television and daytime talk shows. They argue these programs give disproportionate attention to Democratic candidates and causes while marginalizing Republican voices. The Center for American Rights, a conservative organization, celebrated the FCC's January notice as a victory against what they call left-wing entertainment shows masquerading as news.

Carr has been responsive to these complaints. He revived FCC complaints against CBS, ABC, and NBC stations that had been dismissed during the Biden administration. These complaints alleged bias in political programming. The complaints don't allege specific violations of the equal-time rule. They allege a pattern of unfair coverage. By reviving these complaints and issuing guidance that casts doubt on talk show exemptions, Carr is sending a message to broadcasters: change your guest booking practices or face regulatory scrutiny.

The Counter-Argument from FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez

The FCC isn't unanimous on this issue. Anna Gomez, the sole Democratic commissioner, issued a sharp response to the January guidance. She labeled it misleading and accused the FCC of misrepresenting its own rules and precedents.

Gomez's fundamental argument is that nothing substantive has changed. The FCC hasn't adopted new regulations. It hasn't issued new policy at the commission level. The Media Bureau's 2006 decision remains in place. The bona fide news exemption remains in place. What Carr has done is issue guidance that contradicts how the industry has understood and applied these rules for two decades.

This distinction matters legally. The FCC is an agency with specific authority granted by Congress. When the FCC makes binding determinations, it typically follows formal processes. It issues regulations that go through notice-and-comment procedures. It votes on policies at the commission level. Courts defer to these formal regulatory determinations based on administrative law principles.

But guidance is different. Guidance documents provide the FCC's interpretation of existing rules. They don't have the same legal force as regulations. An agency can contradict its previous guidance if it provides reasons for doing so. But if previous guidance was based on statutory interpretation, changing it requires stronger justification.

Gomez essentially argues that Carr is using guidance to accomplish what he couldn't do through formal regulation. He's telling broadcasters that their long-standing understanding of the exemption is wrong without going through the formal process of changing the rule. This creates a kind of regulatory coercion. Broadcasters might comply with the new guidance even though it lacks formal legal standing, simply to avoid FCC enforcement actions.

Gomez also raises a free speech concern. She argues that broadcasters have constitutional rights to exercise editorial discretion. The First Amendment protects their right to choose which guests to book, what stories to cover, and how to frame issues. If the FCC is pressuring them to change these decisions based on political considerations, that's potentially a constitutional problem.

The Practical Impact on Late-Night and Daytime Programming

So what happens in the real world if the FCC enforces stricter interpretations of equal-time rules on talk shows? The impacts would ripple through broadcasting in significant ways.

First, networks would face difficult choices about how aggressively to book political figures. If booking a Republican candidate for an in-depth interview triggers equal-time obligations to Democrats, networks might book political figures less often. They might shift toward interviewing celebrities, authors, and activists instead, since equal-time rules don't apply to non-candidates.

This would particularly affect shows that pride themselves on news-making interviews. The View has broken news through candidate interviews. Late-night shows occasionally attract newsmakers for significant interviews. These shows might reduce this kind of content if it creates regulatory compliance headaches.

Second, networks would need robust documentation of their editorial processes. If the FCC challenges whether a show qualifies for the exemption, networks would need to prove that booking decisions were based on newsworthiness, not political bias. This means documenting why certain guests were booked, why others weren't, and what editorial standards guided these decisions. Some networks might create formal policies to reduce vulnerability to challenge.

Third, the cost of compliance would increase. Networks might need legal reviews of guest bookings to ensure they're not creating equal-time obligations. Producers would need training on equal-time requirements. The administrative burden alone could reshape production decisions.

Fourth, there's a potential chilling effect on controversial programming. If political discussion becomes more legally fraught, some networks might avoid the most contentious topics. They might reduce coverage of election cycles or controversial political events because the legal complexity isn't worth it. This would reduce the amount of serious political discussion on television.

Following the FCC's 2025 guidance, the number of talk shows filing for exemption is projected to increase significantly, alongside a rise in those affected by the equal-time rule. Estimated data.

How Talk Shows Actually Book Guests in Reality

To understand what the FCC's guidance really threatens, it helps to understand how talk shows actually operate. These aren't news divisions. They're entertainment productions with different goals and standards than news programming.

A late-night show books guests for entertainment value, audience appeal, and relevance to current events. The booking team considers whether a guest is promoting a movie, writing a book, launching a campaign, or offering a unique perspective on current news. They think about whether an interview will be entertaining, informative, or both.

Guest booking is fundamentally about creating good television. Producers want guests who are articulate, willing to be challenged, capable of interesting conversation, and appealing to the show's audience. A politician might get booked because they're charismatic, because they've made news that day, or because they have a compelling story to tell.

Political affiliation is one factor among many, but it's not usually the primary consideration. A show might book a Republican politician one week and a Democratic politician the next week because both are newsworthy or relevant. The booking pattern reflects news cycles and guest availability as much as editorial preference.

The problem with equal-time rules in this context is that they force an artificial symmetry. They assume that if you book one politician, you must balance it with another. But talk shows don't operate on that principle. They operate on news judgment. If a particular politician is newsworthy this week, they get booked. If nobody particularly newsworthy and available the next week, they don't.

Equal-time rules were designed for news programming, where you're covering political events comprehensively. They make less sense in entertainment programming where the focus is on individual personalities and current moments, not comprehensive coverage of political campaigns.

The Conservative Group's Perspective and Political Motivation

The Center for American Rights, a conservative organization, has been instrumental in pushing the FCC on this issue. The group filed complaints against ABC, NBC, and CBS for what it alleges is biased political coverage. These complaints were dismissed during the Biden administration but revived by Carr in January 2025.

The group's framing is that late-night and daytime talk shows are masquerading as news programming to escape equal-time rules. They argue that these shows are actually partisan propaganda dressed up in entertainment clothing. They describe them as DNC-TV, suggesting they're essentially Democratic National Committee media outlets.

This narrative resonates with a significant segment of the conservative media ecosystem. There's genuine concern among some conservatives that mainstream broadcast television is biased against Republican candidates and causes. Research on this is mixed. Some studies show late-night hosts make more jokes about Republicans than Democrats, but joke frequency doesn't necessarily correlate with bias in guest booking or news coverage.

The Center for American Rights' strategy is to use equal-time rules as a lever to change content. By arguing that talk shows should comply with equal-time requirements, they're essentially arguing for forced balance in guest bookings. From their perspective, this would result in more Republican politicians and conservative voices on shows that they believe are currently too liberal.

From the networks' perspective, this is threatening. It suggests that regulatory pressure could be applied to force content changes based on political complaints. If a conservative group can convince the FCC that equal-time rules apply to talk shows, those groups could file complaints any time a show books a Democratic candidate without immediately booking a Republican alternative. This becomes a mechanism for weaponizing regulation against content that certain political groups dislike.

The Distinction Between Cable and Broadcast: Why It Matters

An important context that often gets lost in this discussion is that the equal-time rule doesn't apply uniformly to all television. It applies specifically to broadcast stations that use FCC-licensed spectrum. Cable networks operate under different rules.

CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, and other cable networks don't have to follow equal-time requirements. They can program however they want without worrying about balancing political viewpoints. This is a crucial distinction. If equal-time rules become more onerous on broadcast networks, we'd see an interesting reversal: broadcast television would become more constrained in its editorial freedom while cable news remains unconstrained.

This actually raises questions about the fairness of the system itself. Cable news networks can be as politically biased as they want. But broadcast networks, which theoretically have more public interest obligations, would face regulatory pressure to maintain balance. Over time, this could drive more sophisticated political programming to cable, while broadcast remains more entertainment-focused and less politically adventurous.

The irony is that cable news often engages in more overtly partisan programming than entertainment talk shows. Fox News, MSNBC, and CNN all have shows with clear ideological orientations. But they don't face equal-time pressures because they use cable distribution, not public spectrum.

Broadcasters probably don't appreciate this irony. They're being pressured on guest booking in ways that cable networks aren't. This regulatory disparity could reshape the television landscape over time.

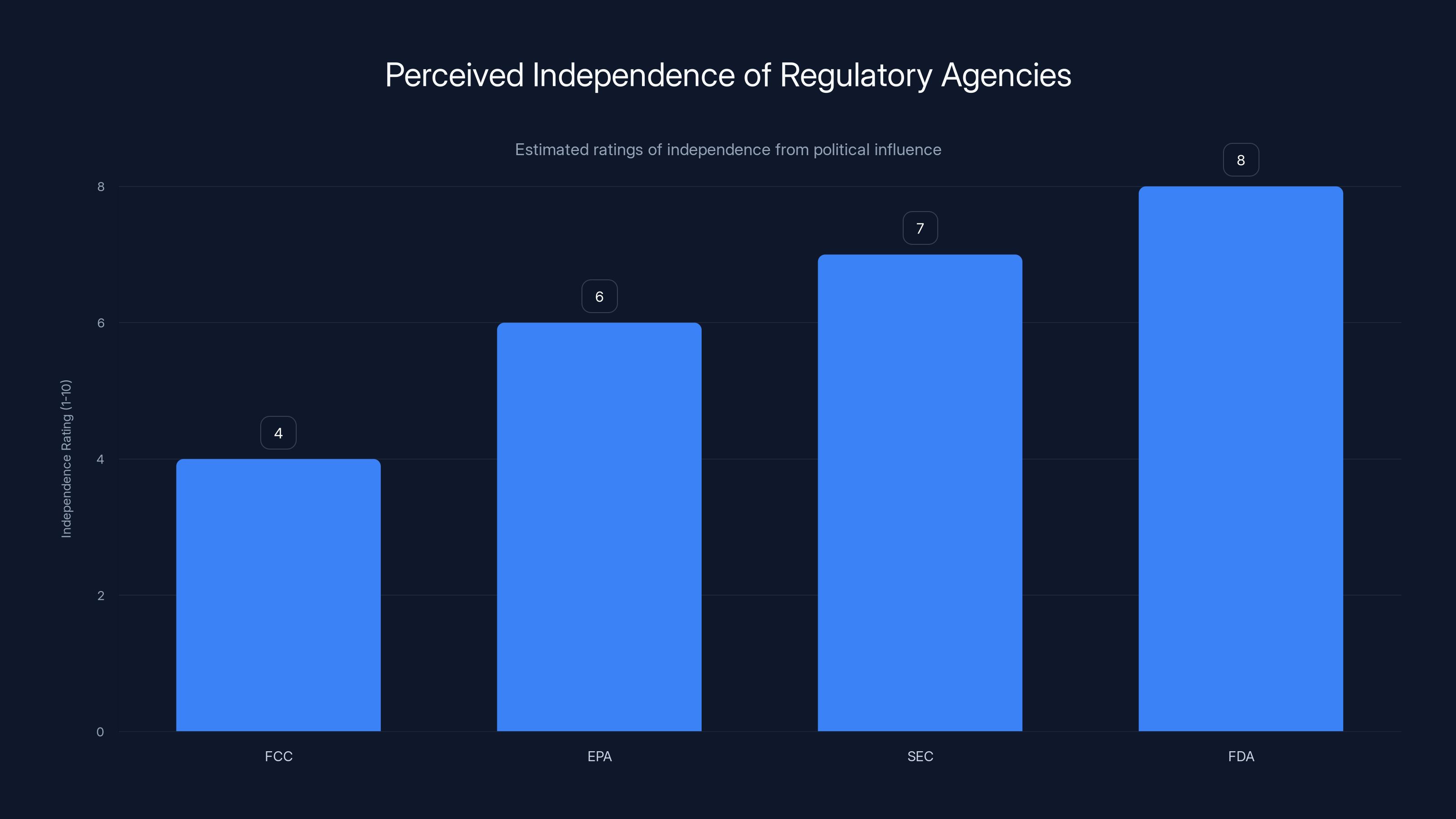

Estimated data suggests varying levels of perceived independence among regulatory agencies, with the FCC rated lower due to political influence concerns.

Constitutional and Free Speech Implications

Underlying all of this is a genuine constitutional question: Does the FCC have authority to force content changes on broadcast television based on political considerations?

The Supreme Court has historically given the FCC broad authority to regulate broadcast television in the public interest. The reasoning is that broadcast spectrum is limited and publicly owned, so the FCC can impose requirements that wouldn't apply to other media. This is why cable networks can avoid equal-time rules while broadcast networks can't.

But there are limits. The Supreme Court has also recognized that the First Amendment applies to broadcast television. The government can't regulate broadcast content in ways that are pretextual for censoring disfavored speech. If the FCC is applying equal-time rules selectively based on political content, that might violate First Amendment principles.

Gomez's argument essentially makes this point. She contends that the FCC is using regulatory authority as a tool to suppress criticism of those in power. That's constitutionally problematic. The FCC should regulate based on neutral principles applied consistently, not based on the political content of programming.

This gets at something fundamental: when does regulatory authority become political control? If the FCC is pressuring broadcasters to change guest bookings based on complaints from political groups, that crosses a line. Regulation is supposed to enforce public interest standards. It's not supposed to police political speech on behalf of one political faction.

Broadcasters have argued this for years. They claim that editorial discretion is a fundamental right. The courts have generally agreed, at least to a point. But the scope of FCC authority over broadcast content remains unsettled in many ways.

What the FCC's Ambiguous Guidance Actually Accomplishes

One way to interpret the FCC's January guidance is as a brilliant move in political messaging. By issuing guidance that's vague and suggestive rather than definitive, the FCC creates regulatory uncertainty without formally changing rules. Networks can't rely on the 2006 decision anymore, but they also don't know what would pass FCC review. This uncertainty itself is pressure.

If a network wants to book a controversial political figure, staff members might now question whether this will create equal-time problems. Legal departments might flag guest bookings for review. Producers might self-censor to avoid potential issues. None of this requires the FCC to actually enforce anything. The threat of enforcement is sufficient to change behavior.

This is sometimes called regulatory jawboning. The agency doesn't formally regulate. It suggests, threatens, or indicates concerns. The regulated entities respond by changing behavior to avoid potential problems. It's a less formal but often effective tool of regulatory control.

The question is whether this is legitimate governance. Some would argue it's appropriate regulatory communication. Others would argue it's coercive and lacks proper procedural legitimacy. It's a genuinely contested issue in administrative law.

What's clear is that networks are now in a more difficult position. They could file petitions with the FCC to get formal determinations about whether their shows qualify for the exemption. But that process takes time and involves risk. Or they could self-regulate by changing booking practices to avoid potential problems. Many will probably choose the latter.

The Precedent This Sets for Future Regulation

Regardless of whether you think the FCC's approach here is good or bad policy, it sets an important precedent. It shows that regulatory agencies can use ambiguous guidance to reshape industry practice without formal rule changes. It shows that political pressure can drive regulatory action. It shows that formal deference to precedent can be abandoned through reinterpretation.

This precedent applies beyond this specific situation. Future FCC chairs or other regulators could use similar tactics. If a different administration found different aspects of broadcast programming problematic, they could issue similar guidance casting doubt on precedent. This could create a pendulum effect where regulatory interpretation swings based on political leadership changes.

Broadcasters have institutional reasons to want more stability. They invest in programming based on assumptions about regulatory requirements. If those assumptions change regularly based on political winds, it creates chaos. It makes programming decisions riskier and more complex.

For viewers and the public, the implications are less clear. On one hand, regulatory uncertainty could reduce the amount of political programming available. On the other hand, it could also increase diversity of political viewpoints if it forces networks to book broader ranges of guests. The ultimate outcome depends on how the FCC interprets and enforces the guidance.

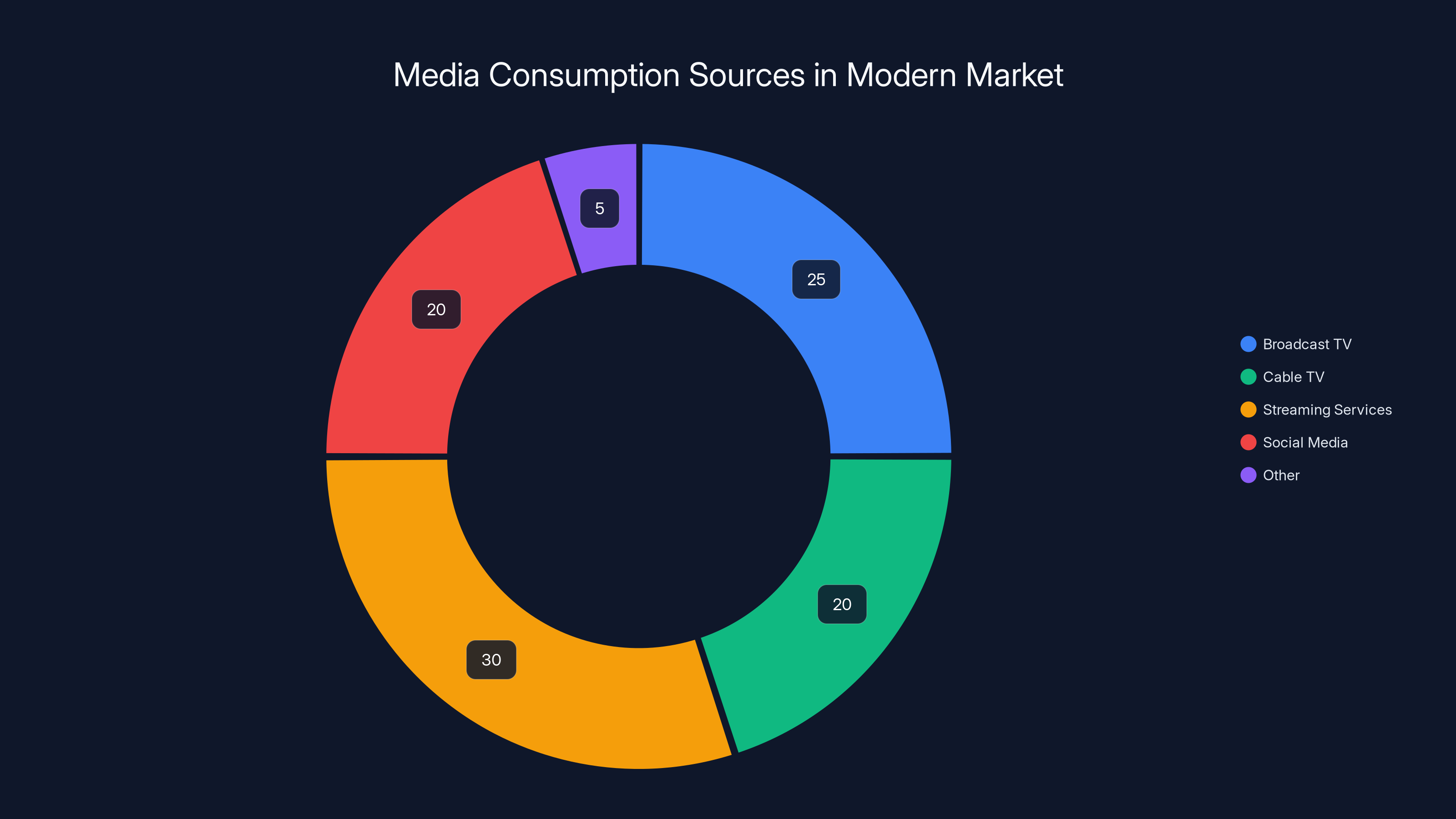

Estimated data shows streaming services and social media now capture a significant portion of viewership, reflecting increased competition in the media landscape.

The Role of Viewer Choice and Market Competition

One argument in all of this is often overlooked: the role of market competition and viewer choice. In the 1980s, when equal-time rules were more strictly enforced, the regulatory concern was that broadcasters had monopoly power. There were only a few television stations in each market. Viewers couldn't easily find alternative sources of information.

Today, that's completely different. Viewers have hundreds of channels plus streaming services plus social media. If they don't like The View's guest selection, they can watch another show. If they think late-night is too liberal, they can skip it and watch cable news instead. The information environment is vastly more competitive than it was when equal-time rules were created.

This raises a question about whether equal-time rules remain necessary in the modern media landscape. Market competition might provide better protection against unfair practices than regulatory mandates. If a show is too obviously biased, viewership suffers. Advertisers follow audiences. Networks respond to the market incentive.

But it's also true that broadcast television remains culturally significant. Network broadcasts reach larger and more diverse audiences than niche cable channels. If broadcast networks skew their content in particular directions, that has cultural impact even if viewer choice is technically available.

This tension between market forces and regulatory requirements remains unresolved. The FCC's guidance doesn't fully address it. Presumably, if networks comply with equal-time requirements and book more balanced guest rosters, they believe they'll reach the same audiences. But they might lose audience share to cable alternatives that don't have equal-time constraints. This is an actual risk that networks face.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/debate-moderators-56a605ad5f9b58b7d0df83ea.jpg)

The Likely Outcome: Uncertain Enforcement and Strategic Adaptation

Predicting how this plays out is difficult, but patterns suggest a few likely scenarios. First, the FCC probably won't formally overturn the 2006 decision or issue clear new rules. The legal and political costs would be too high. Instead, the ambiguous guidance will persist. Networks will gradually adapt by changing practices incrementally.

Second, some networks might file petitions seeking formal determinations about whether their shows qualify for exemptions. The FCC would then have to make specific rulings. These rulings would likely consider how frequently shows book political candidates, whether they book candidates from both parties, and whether programming decisions are based on newsworthiness or political bias.

Third, the most likely adaptation is that shows will book fewer political candidates and more celebrities, authors, and activists. This reduces regulatory risk while maintaining entertainment value. Political discussion will shift more toward cable news, where hosts can be more overtly partisan without equal-time concerns.

Fourth, if there's significant litigation, courts would ultimately decide whether the FCC's approach is permissible. A court might rule that the guidance is arbitrary, that it violates First Amendment principles, or that it exceeds the FCC's authority. Or courts might defer to the FCC's interpretation of its own rules. This outcome is genuinely unpredictable.

Fifth, the next change in political leadership could reverse this entirely. A future FCC chair could issue guidance saying that late-night shows clearly qualify for the exemption based on decades of practice. The pendulum could swing back.

Broader Questions About Regulatory Independence and Political Pressure

Step back from the specific equal-time rule issue, and there's a larger concern about regulatory capture and political influence. The FCC is supposed to be an independent agency. That means it makes decisions based on law and precedent, not political pressure. But the history of this particular issue suggests the FCC might not be operating as truly independent.

Brendan Carr was explicitly selected because he's ideologically aligned with Trump's media criticism. He's already demonstrated willingness to follow political leadership. The equal-time guidance appears responsive to complaints from conservative political groups. This doesn't look like independent regulatory decision-making. It looks like political leverage disguised as regulation.

This matters because if regulatory agencies are captured by political interests, they become tools for controlling content rather than protectors of public interest. In a democracy, we expect regulatory agencies to be somewhat insulated from direct political pressure. That's not always perfectly honored in practice, but the principle matters.

FCC commissioners are technically supposed to serve fixed terms that don't align perfectly with presidential terms. The idea is that no single president can reshape the commission entirely. But this only works if commissioners maintain independence. If chairs actively implement partisan political agendas, the protections break down.

From a governance perspective, this raises serious concerns. It suggests that regulatory agencies might be vulnerable to political manipulation in ways that undermine their institutional independence. That has implications far beyond the equal-time rule.

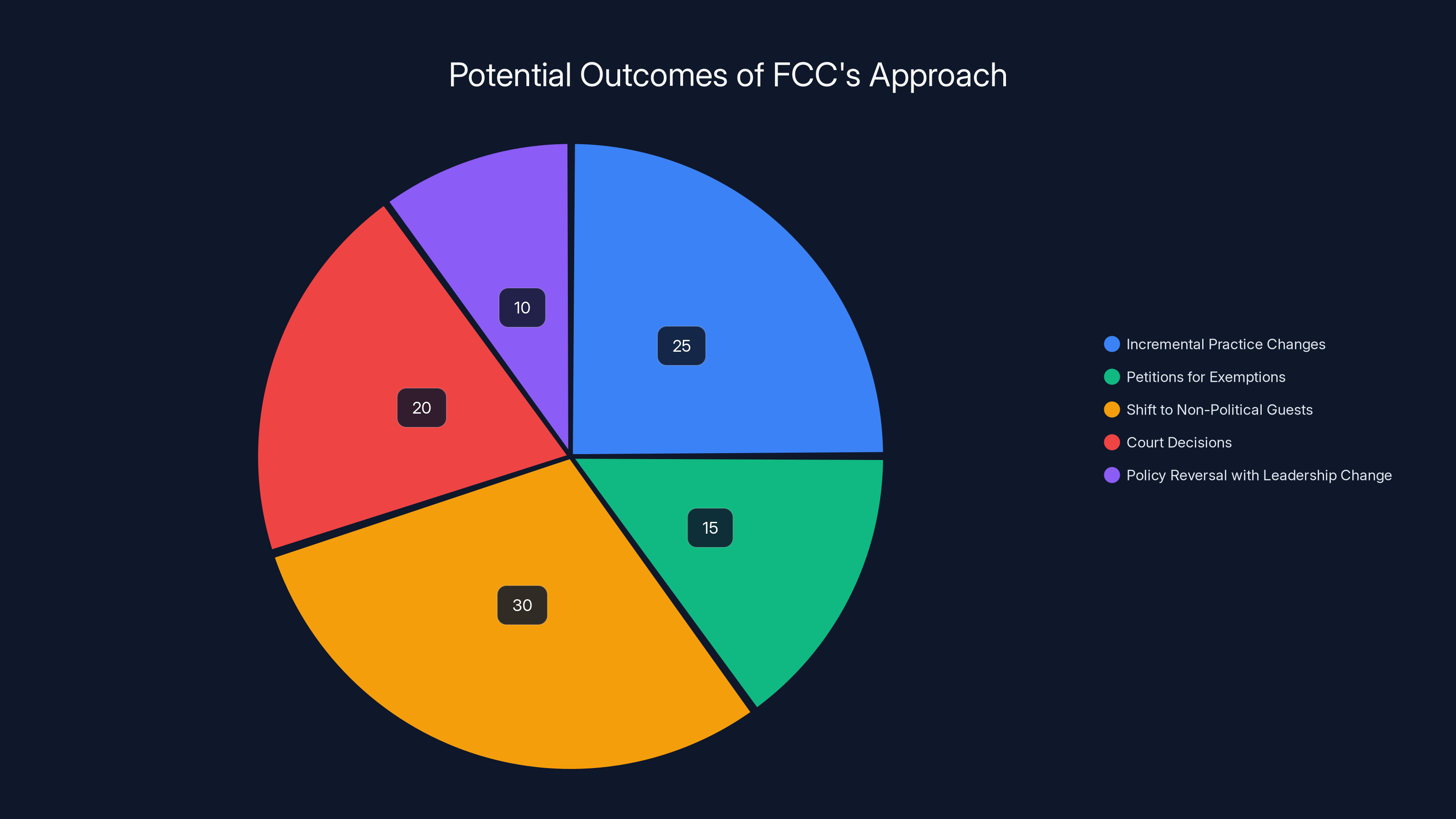

Estimated data suggests that the most likely adaptation is a shift to booking non-political guests (30%), followed by incremental changes in network practices (25%).

What This Means for the Future of Broadcast Television

The equal-time rule guidance is one battle in a larger war over the future of broadcast television. For decades, broadcast networks have been under regulatory obligations that cable networks don't face. This has made traditional broadcast less attractive for certain kinds of programming. News, for example, is increasingly a cable domain because cable doesn't have equal-time constraints.

If the FCC tightens equal-time enforcement, this trend will accelerate. More serious political programming will migrate to cable. Broadcast television will become increasingly entertainment-focused. Network news operations, already diminished, might shrink further.

This has cultural implications. Network broadcasts reach larger and more diverse audiences than cable niche programming. If substantive political discussion moves primarily to cable, the median viewer might encounter less serious political content. Instead, they'd get entertainment programming on broadcast and politically partisan programming on cable.

There's also a reverse possibility: networks might challenge the equal-time rule in court. They might argue that modern media landscape makes broadcast equal-time requirements unnecessary, or that the FCC's reinterpretation violates First Amendment principles. A successful constitutional challenge could upend the entire regime.

But challenging the FCC on this is risky. Networks depend on FCC approval for spectrum licenses. Challenging regulatory authority could create hostile relationships that carry other consequences. So most networks will probably adapt quietly rather than fight directly.

The International Perspective: How Other Democracies Handle This

It's worth noting how other democracies approach similar issues. Many countries have rules requiring balance in political coverage during election periods. But most democracies exempt entertainment programming from these requirements. The reasoning is similar to what critics of the FCC's guidance argue: entertainment programming isn't news, so equal-time rules don't logically apply.

The European Union, for example, has rules requiring broadcaster impartiality in news programming. But these don't typically extend to entertainment or opinion programming. Canada has similar approaches. The principle is that regulations should target news and current affairs, where factual claims are being made and public understanding is directly affected.

Entertainment programming operates under different standards. Audiences understand that comedy is subjective. Guest selection in entertainment shows is expected to reflect the show's character and audience appeal. Equal-time rules make less sense in that context.

The FCC's approach is actually an outlier internationally. It's trying to extend political balance requirements to entertainment programming in ways most democracies don't. This might suggest that either the FCC is overreaching or that other democracies are missing important regulatory tools. That's a genuine question without obvious answers.

Practical Steps Networks Might Take to Prepare

If you're running a broadcast network, what would you do in response to this guidance? The practical steps are worth considering because they reveal how regulatory uncertainty reshapes behavior.

First, you'd probably create a documentation system for guest booking decisions. You'd want to demonstrate that selections are based on newsworthiness and audience appeal, not political bias. You'd document why specific guests were booked and why alternatives weren't. This creates a defensible record if the FCC challenges your exemption.

Second, you'd hire consultants to analyze your booking patterns. You'd want to understand whether your guest roster shows obvious partisan tilt. You'd want to know this before the FCC analyzes it. If there are problems, you'd address them voluntarily rather than wait for regulatory action.

Third, you might file a petition seeking formal confirmation that your show qualifies for the exemption. This would be expensive and time-consuming, but it would provide certainty. You'd know where you stood rather than operating under regulatory ambiguity.

Fourth, you'd probably reduce political candidate bookings somewhat. You'd shift toward celebrities, authors, and activists. This reduces regulatory risk and still provides interesting programming.

Fifth, you'd brief your legal team and producers on equal-time principles. You'd ensure everyone understands the regulatory environment and the need to document editorial decisions.

These steps increase compliance costs and complexity. They also change editorial decisions. That's exactly what regulatory pressure accomplishes, even without formal enforcement.

The Flip Side: Why Networks Might Fight This

But networks might also decide to fight this, or at least to resist. There are reasons why they might view the FCC guidance as overreach worth challenging.

First, networks have First Amendment rights. They can argue that guest booking is editorial discretion protected by the First Amendment. Courts have recognized that editorial discretion is fundamental to journalism and entertainment alike. The FCC shouldn't be able to override this without clear statutory authority and proper procedure.

Second, networks can argue that the FCC's guidance contradicts settled law. The 2006 decision was made through formal process. If the FCC wants to overturn it, that requires formal regulatory action. Informal guidance shouldn't be sufficient to overturn precedent. This is an administrative law argument about proper regulatory procedure.

Third, networks can argue that the FCC lacks jurisdiction. If entertainment talk shows are primarily entertainment rather than news, do equal-time rules even apply? The FCC would need to establish that these shows are engaged in political broadcasting in ways that trigger regulation. That's not obviously true for shows that book a wide variety of guests for entertainment purposes.

Fourth, networks might argue that the guidance violates the Administrative Procedure Act. The APA requires agencies to follow proper procedures when making regulatory determinations. If the FCC is trying to overturn precedent through informal guidance rather than formal regulation, that might violate APA requirements.

Fifth, networks could argue that selective enforcement is unconstitutional. If the FCC only applies these rules to broadcast networks and not cable, and if the application is based on political pressure from particular groups, that might constitute selective enforcement based on viewpoint. That could violate equal protection or due process principles.

These arguments aren't slam dunks. The FCC has significant authority over broadcast regulation. But they're plausible legal positions that networks could pursue if they chose to fight.

The Inevitability of Regulatory Capture in Political Contexts

One broader theme that emerges from all of this is that regulatory agencies are never truly independent from politics. That's not cynical realism. It's just how systems work. Regulatory agencies are created by political branches. Their budgets depend on political approval. Their leadership is appointed through political processes. Expecting them to be completely isolated from politics is unrealistic.

What matters is the degree of independence. Some agencies maintain strong independence through professional culture, statutory protections, and institutional norms. Others become more directly responsive to political interests. The FCC seems to be moving in the latter direction under current leadership.

This is partly because of individuals like Brendan Carr who are explicitly political appointees. It's also partly because Congress has become more polarized and more interested in regulatory accountability to particular political factions. The whole regulatory environment has become more political.

Over time, this might reshape the media landscape significantly. If regulatory agencies can be used to pressure broadcasters, then content decisions will be influenced by which political faction controls the FCC. That's not an independent regulatory system. That's political control of media through regulatory mechanisms.

Whether that's normatively good or bad depends partly on whether the political faction in control is making decisions you agree with. But the structural problem remains: independent regulatory authority is being compromised by political pressure.

Where This Goes From Here

The most likely scenario is that this issue will develop unevenly. Some networks will change practices voluntarily to reduce regulatory risk. Others will file petitions seeking clarity. The FCC will issue rulings on specific shows. Some of those rulings will be appealed to courts. Over several years, a more concrete framework will emerge.

But the fundamental question will remain unsettled: Does the FCC have authority to enforce equal-time rules on entertainment programming? That question probably won't be definitively answered until courts get involved.

In the meantime, networks will operate under uncertainty. They'll make programming decisions based partly on legal calculations rather than pure editorial judgment. That's the real impact of this guidance: it introduces political and regulatory considerations into decisions that were previously made primarily on editorial grounds.

For viewers, the implications are mixed. They might see different kinds of programming. Whether that's good or bad depends on your perspective. If you think late-night shows needed more balance in guest booking, this might seem like a positive development. If you think entertainment programming should be free from political regulation, this seems like overreach. Both perspectives have merit.

What's clear is that we're in a period of flux on broadcast regulation. The ground rules that have guided the industry for decades are being questioned. What replaces those rules remains to be seen. But the disruption will have measurable impacts on what gets programmed and how networks make decisions.

FAQ

What is the FCC's equal-time rule and why does it matter?

The equal-time rule, formally called the Equal Opportunities Rule, requires broadcast television stations to provide comparable airtime to opposing political candidates when one candidate receives broadcast time. This applies specifically to FCC-licensed broadcast stations that use public spectrum. The rule matters because it's designed to prevent broadcasters from using publicly owned spectrum to unfairly promote certain candidates over others, maintaining fairness in election coverage.

Why do late-night talk shows think they've been exempt from equal-time rules?

A 2006 FCC decision ruled that The Tonight Show with Jay Leno's interview segment qualified for the bona fide news exemption, meaning it didn't have to comply with equal-time requirements. The industry interpreted this narrowly as establishing a precedent that entertainment talk shows with news interview elements could also qualify for the exemption. For nearly 20 years, networks operated under this assumption without FCC challenge.

What changed in January 2025 with the FCC's guidance?

FCC chair Brendan Carr issued guidance suggesting that the 2006 decision was narrower than the industry understood and that currently airing late-night and daytime talk shows haven't been proven to qualify for the exemption. The FCC encouraged networks to file petitions if they want formal confirmation of their exemption status. This introduced regulatory uncertainty where networks previously felt protected by established precedent.

What does the FCC actually want from talk show networks?

The FCC isn't explicitly demanding anything specific. Instead, the guidance creates pressure by casting doubt on previous assumptions. The implicit message is that networks might face equal-time compliance obligations if they book political candidates. This could incentivize networks to either change guest booking practices or go through formal petition processes to secure their exemption status.

How does this affect cable news networks like CNN or MSNBC?

Cable news networks aren't subject to equal-time rules because they don't use FCC-licensed broadcast spectrum. They can program however they want without worrying about balancing political viewpoints. This creates a regulatory disparity where broadcast networks face more constraints than cable networks, potentially shifting more serious political programming to cable channels.

What would happen if networks don't comply with equal-time rules?

Non-compliance could result in FCC enforcement actions, fines, or challenges to broadcast license renewals. However, the current situation is ambiguous because the FCC hasn't formally declared talk shows subject to equal-time requirements. Networks are essentially guessing about what compliance requires. This ambiguity itself creates pressure for compliance even without formal enforcement.

Can networks legally challenge the FCC's new interpretation?

Yes, networks could argue that the FCC guidance misinterprets existing law, violates the Administrative Procedure Act by attempting to overturn precedent through informal guidance, or violates First Amendment principles by pressuring editorial decisions. However, challenging the FCC is risky because networks depend on FCC approval for spectrum licenses. Courts might also defer to FCC regulatory expertise, making victory uncertain.

What's the difference between the FCC's authority over broadcast and cable television?

The FCC has broader authority over broadcast television because broadcast uses publicly owned spectrum that's licensed by the FCC. Cable television isn't licensed in the same way, so the FCC has less direct regulatory authority. This justifies different rules for different types of television, but it also creates disparities where cable can be more partisan than broadcast.

How do other democracies handle equal-time rules for entertainment programming?

Most democracies have political balance requirements for news programming during election periods, but they generally exempt entertainment programming from these requirements. The reasoning is that entertainment isn't news, so equal-time logic doesn't apply. The FCC's approach of extending balance requirements to entertainment shows is relatively unusual internationally.

What happens if courts get involved in this dispute?

Courts could rule on whether the FCC's guidance is legally proper, whether it violates First Amendment rights, whether the FCC properly followed administrative procedures, or whether equal-time rules apply to entertainment programming at all. A successful court challenge could overturn the guidance or expand it. Ultimately, courts would likely decide what rules actually apply, but this could take years of litigation.

Key Takeaways from the Equal-Time Rule Controversy

The FCC's January 2025 guidance represents a significant reinterpretation of broadcast regulatory authority, shifting assumptions that have governed the industry for nearly two decades. Brendan Carr's FCC is using ambiguous guidance to create pressure for editorial changes without formal rule changes, which raises important questions about regulatory independence and political influence. Networks face a choice between adapting guest booking practices voluntarily, filing formal petitions for exemption confirmation, or challenging the FCC's authority through legal action. The outcome will likely reshape the media landscape by pushing more serious political programming toward cable networks while potentially changing the character of broadcast entertainment. Ultimately, this controversy reflects broader tensions between regulatory authority, First Amendment protections, and the role of government in mediating media content in democratic societies.

Related Articles

- Porn Taxes & Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Battle [2025]

- Porn Taxes and Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Crisis [2025]

- Verizon's 365-Day Phone Lock: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Setapp Mobile iOS Store Shutdown: What It Means for App Distribution [2026]

- Verizon's Visible Outage Credits: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Trump Mobile FTC Investigation: False Advertising Claims & Political Pressure [2025]

![FCC Equal-Time Rule & Late-Night Talk Shows Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fcc-equal-time-rule-late-night-talk-shows-explained-2025/image-1-1769033254262.jpg)