Introduction: When Science Meets Sound

Imagine walking into a concert hall and seeing a henge built entirely of fiddles, or a chaotic triangle that transforms invisible electromagnetic radiation into haunting melodies. Sound impossible? That's exactly what's happening at Georgia Tech's annual Guthman Musical Instrument Competition, one of the most fascinating and unconventional events in the intersection of music, engineering, and artistic innovation.

For nearly three decades, this competition has been quietly revolutionizing how we think about musical instruments. It's not about perfecting the piano or creating a better guitar. Instead, the Guthman Competition invites inventors, engineers, and artists from around the world to submit entirely new instruments of their own design, competing for $10,000 in prizes and the prestige of being recognized as someone who fundamentally changed what music can be.

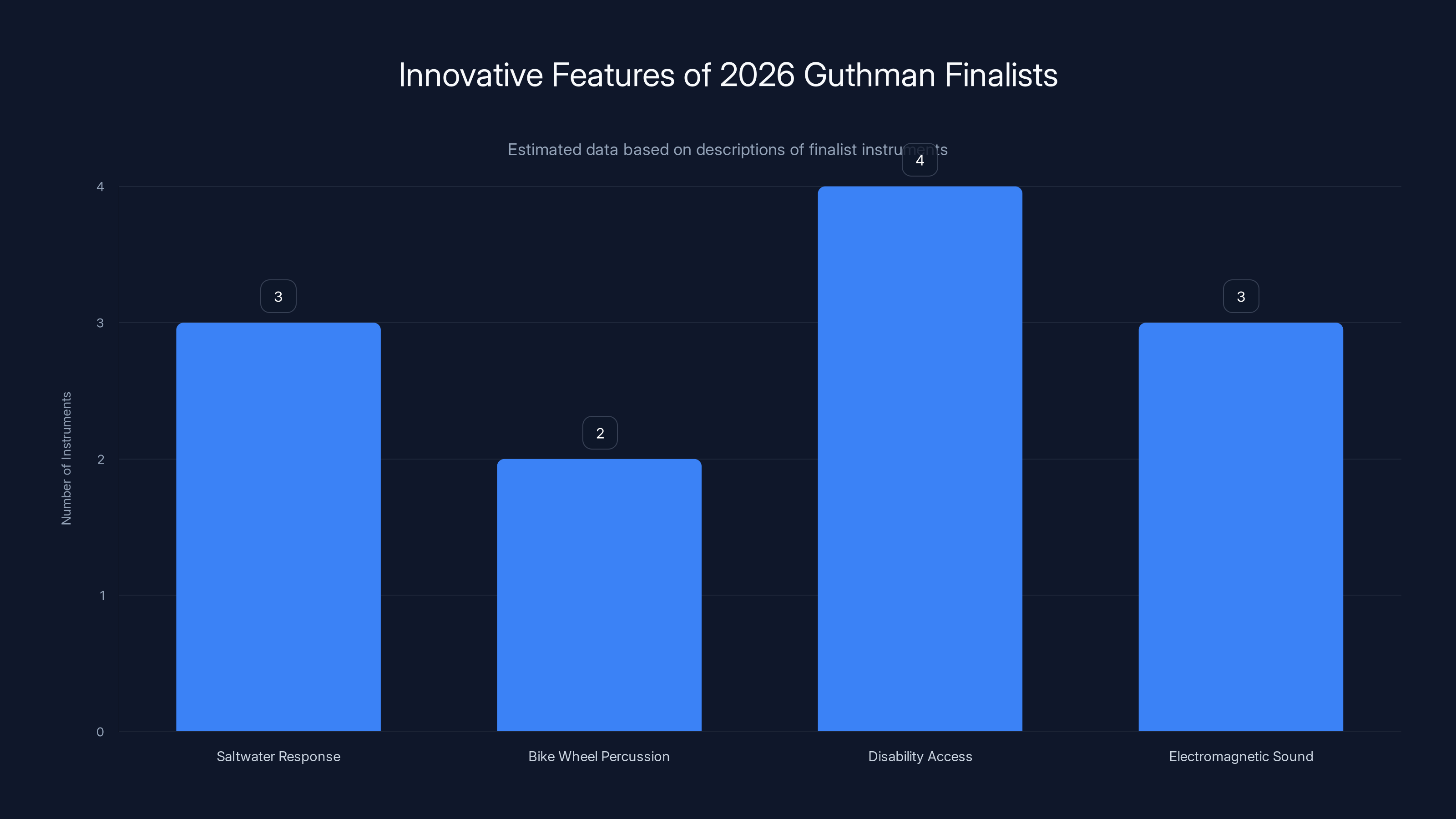

The 2026 finalists represent something remarkable: a collection of oddballs, visionaries, and technical wizards who've decided that traditional instruments are limiting. They've created instruments that respond to saltwater, transform bike wheels into percussion, enable musicians with disabilities to perform professionally, and literally make the invisible audible. These aren't incremental improvements. They're category-busting innovations that force us to reconsider what an instrument even is.

What makes this competition so important isn't just the creativity on display. It's what these instruments reveal about where music is heading. As technology becomes more accessible, as DIY electronics get cheaper, as 3D printing democratizes manufacturing, we're entering an era where anyone with an idea and some determination can build an instrument. The Guthman finalists are leading the charge, showing what's possible when you refuse to accept that a piano must have 88 keys, or that a drum must be made of wood and leather.

This article dives deep into the 2026 finalists, exploring the technical innovation, artistic vision, and sheer audacity behind each creation. We'll look at what makes these instruments special, how they work, why they matter, and what they tell us about the future of music itself.

TL; DR

- 28 years of innovation: The Guthman Competition has been discovering boundary-pushing instruments since 1998, with past winners now working at major companies

- 2026 finalists are wild: Entries range from Fiddle Henge (a playable henge of spinning fiddles) to the Demon Box (a triangle that converts EMF radiation into music)

- Accessibility meets invention: The Masterpiece is an RFID-enabled synth designed specifically for musicians with disabilities, proving innovation can be inclusive

- Commercial viability: The Demon Box is already available for purchase at $999, showing some inventions can bridge art and commerce

- Winner announcement March 14: A competition concert will determine which finalist takes home the $10,000 prize and recognition from the music world

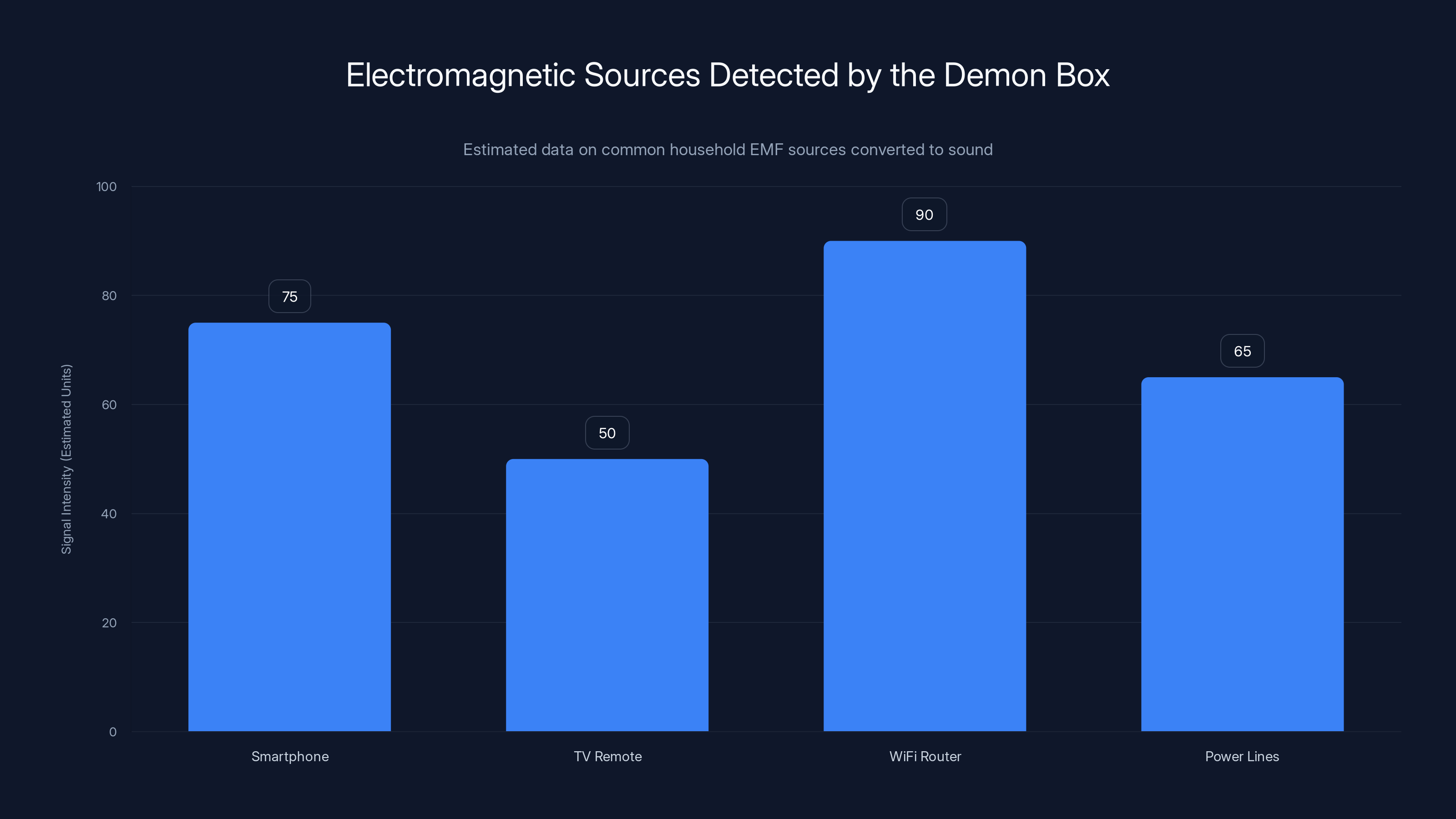

The Demon Box converts electromagnetic signals from common household devices into audible sound, with WiFi routers typically emitting the strongest signals. Estimated data.

The Guthman Competition: 28 Years of Musical Rebellion

Georgia Tech's Guthman Musical Instrument Competition isn't your typical music contest. There are no performances of Chopin or Mozart. No classical virtuosos proving their technical mastery. Instead, it's an annual gathering of inventors who've decided to ask one fundamental question: what if we started from scratch?

Established in the late 1990s, the competition emerged from a simple premise. Musical instruments, like any technology, evolve through incremental improvement and radical reinvention. We've perfected the violin over centuries, but what happens when you ask someone to invent a completely new instrument from the ground up? What would they create? And more importantly, would anyone want to play it?

The answer, it turns out, is yes. Spectacularly yes.

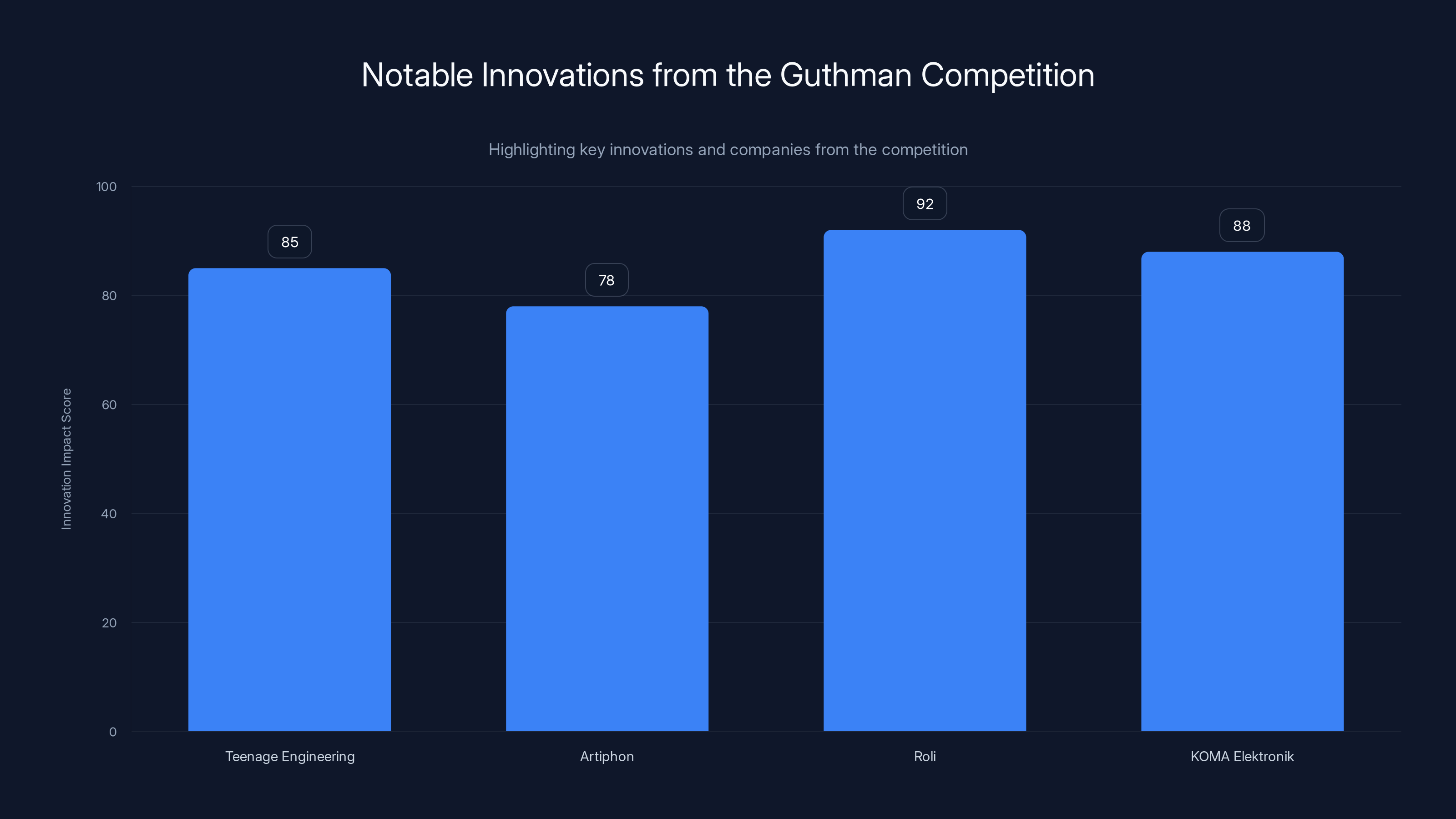

Over nearly three decades, the Guthman Competition has launched careers and changed the music technology landscape. Past finalists include founding members of Teenage Engineering, the Stockholm-based synthesizer company known for innovative, affordable electronic music instruments. The competition also discovered Artiphon, whose founders created hybrid instruments that blend traditional and digital music-making. And Roli, another former finalist, went on to produce the Seaboard, a keyboard that revolutionized how musicians interact with electronic instruments by adding expressive touch controls.

Last year, KOMA Elektronik won the competition with the Chromaplane, a hybrid instrument that combines traditional organ-like functionality with modern synthesis capabilities. The fact that a small German company could win global recognition and prestige demonstrates what the Guthman Competition really offers: visibility and credibility in a field where both matter tremendously.

What sets the Guthman apart from other music competitions is its explicit focus on novelty and innovation rather than musicianship. You don't need to be a virtuoso to enter. In fact, many finalists aren't trained musicians at all. They're engineers, artists, programmers, and tinkerers who've decided to apply their skills to creating something entirely new. This democratization of instrument invention is part of what makes the competition so vital to the future of music.

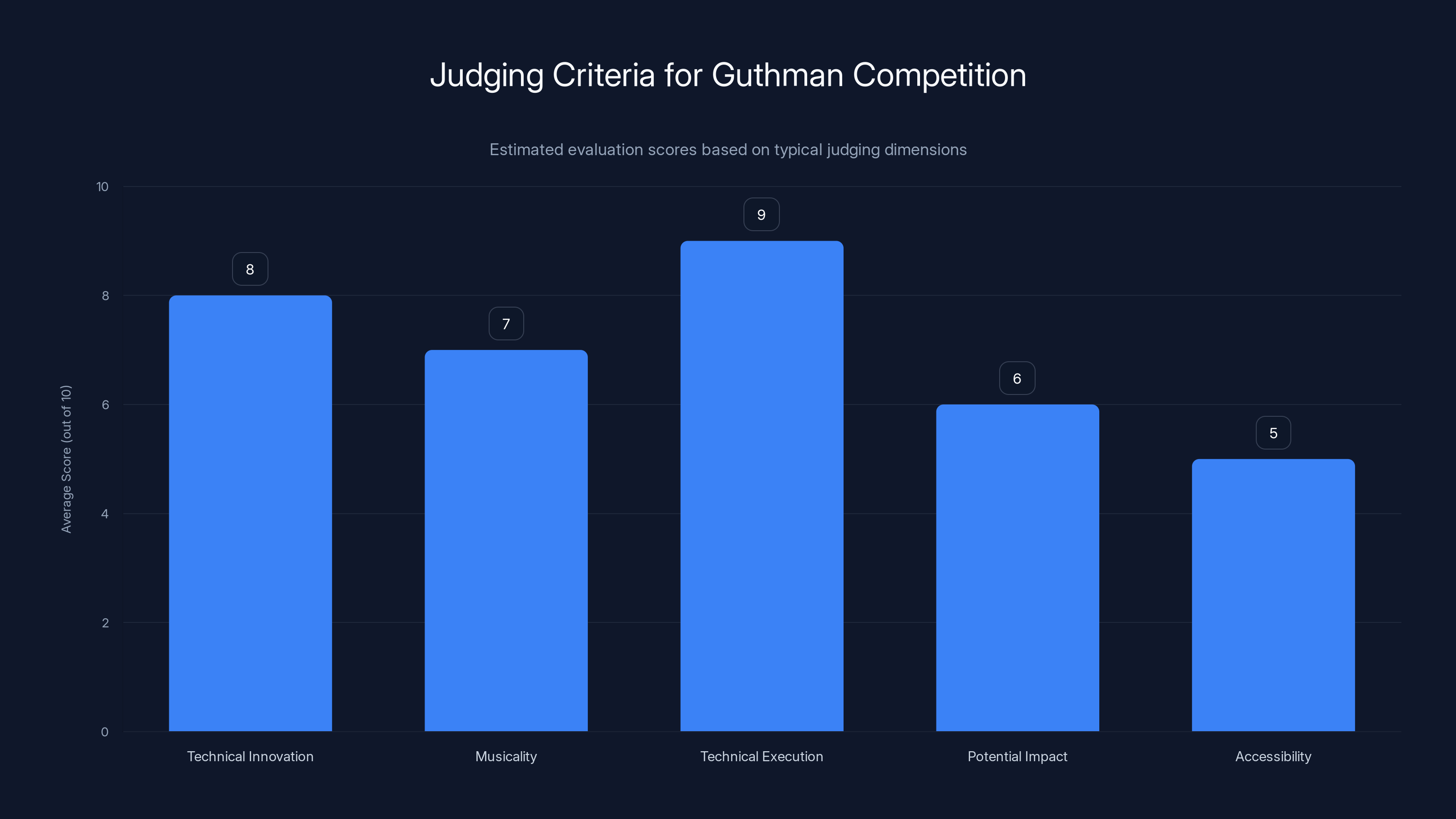

The competition accepts submissions from anyone, anywhere. Each year, the Georgia Tech team reviews hundreds of entries, selecting roughly 10 finalists who are invited to perform their instruments at a competition concert. Judges—typically including musicians, engineers, and music industry professionals—evaluate each instrument based on innovation, musicality, technical execution, and potential impact.

The prize structure reflects the competition's values. The $10,000 grand prize isn't enormous by startup standards, but it's enough to cover manufacturing costs, refine a prototype, or fund early production runs. More valuable than the money is the recognition. Winning or even reaching the finals at Guthman carries real prestige in musical instrument circles. It's a stamp of approval from a respected institution, a signal that you've created something that experts believe matters.

Estimated data showing typical emphasis on technical execution and innovation in the Guthman Competition judging criteria.

Fiddle Henge: When Stonehenge Meets the String Section

Let's start with the most visually striking finalist: Fiddle Henge. Yes, it is literally what the name suggests—a henge made of fiddles.

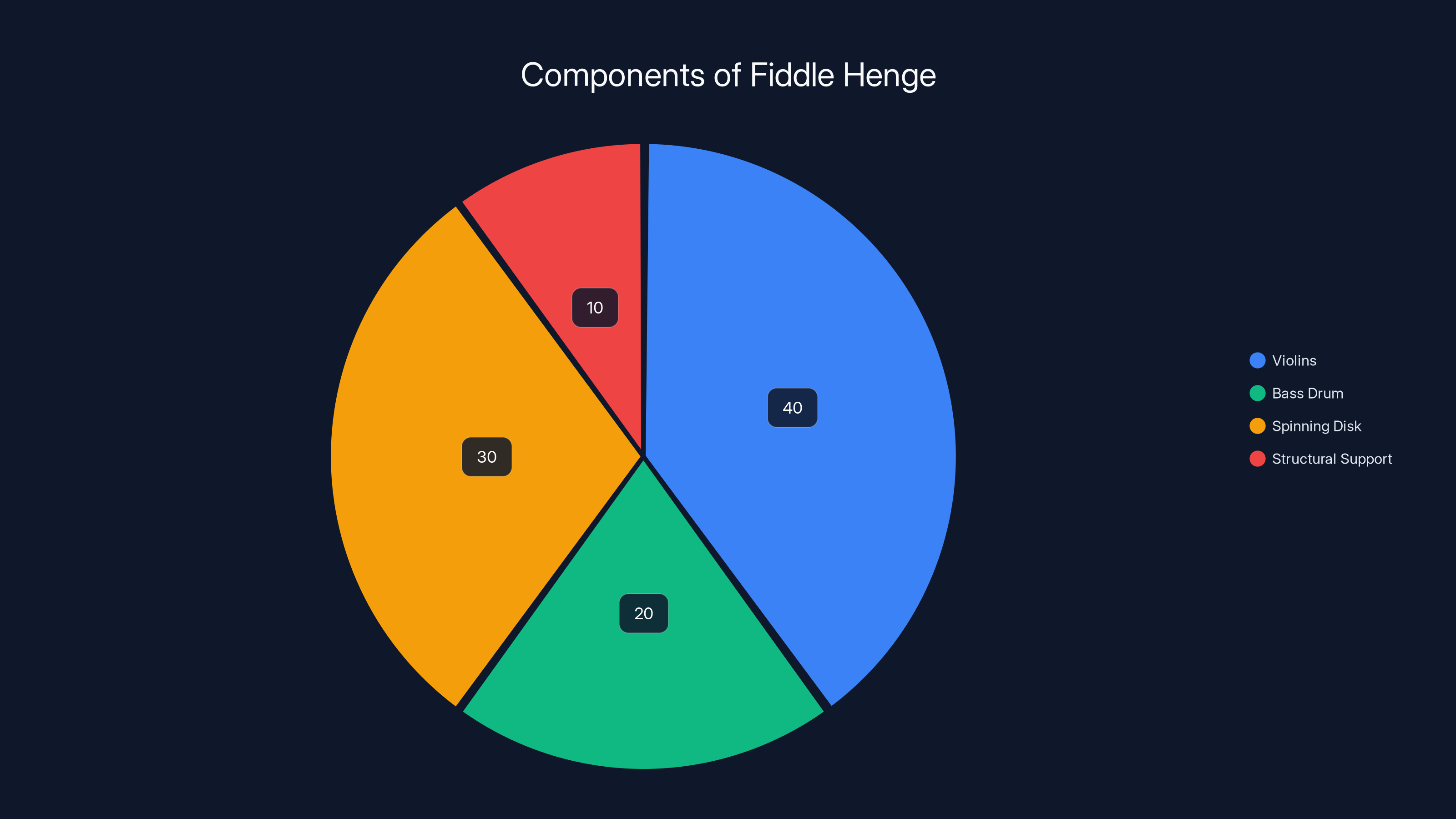

Fiddle Henge is pure sculptural audacity. Four green violins are mounted vertically to a bass drum in a henge-like formation. But here's where it gets clever: instead of a musician playing each violin individually with a bow, a spinning disk (think of it like a record player made of strings) rotates through the henge, creating friction with the violin strings and producing sound. The faster it spins, the higher the pitch. The angle at which it contacts the strings shapes the timbre.

The concept is deceptively simple but technically ingenious. Traditional violins rely on a cellist or violinist controlling the bow manually. With Fiddle Henge, the physics of rotation and friction become the bow. This means one operator can effectively play multiple instruments simultaneously, creating layered textures and harmonic possibilities that would be impossible for a single human with two hands.

What makes Fiddle Henge particularly interesting is how it challenges our assumptions about what defines an instrument. A violin typically assumes human ergonomics—it needs to be held under a chin, played with a specific bow technique, controlled by trained hands. Fiddle Henge abandons all of those assumptions. It doesn't care about ergonomics because it's not designed for a human to hold. It doesn't require traditional bow technique because friction does the work. It's a violin deconstructed and reassembled into something entirely new.

The aesthetic is equally important. By arranging the fiddles in a henge formation, the creator adds a layer of visual theater to the performance. Audiences don't just hear the instrument; they see it. The spinning disk becomes choreography. The arrangement becomes sculpture. The performance becomes a multimedia event.

From a technical perspective, Fiddle Henge demonstrates how constraint breeds creativity. By limiting itself to familiar components (standard violins, a spinning mechanism), the creator forced themselves to find novel ways to make music. This kind of thinking—taking existing technologies and recombining them in unexpected ways—is foundational to musical innovation.

The Demon Box: Making the Invisible Audible

If Fiddle Henge is about visual spectacle, the Demon Box is about sonic revelation. And it might be the most genuinely bizarre invention on this year's finalist list.

The Demon Box is a triangle. Not metaphorically—literally a triangular instrument shaped roughly like a triangle of evil, as one description delightfully put it. But unlike a traditional triangle (the percussion instrument), the Demon Box doesn't produce sound through hitting or striking. Instead, it does something that sounds like science fiction: it converts electromagnetic radiation into music.

Yes, invisible EMF radiation—the kind emanating from your smartphone, your television remote, your Wi Fi router—becomes audible sound when you play the Demon Box. Literally invisible waves become music you can hear. It's like the instrument is detecting the electromagnetic ghosts in the room and giving them voice.

Here's how it actually works: the Demon Box contains sensors that detect electromagnetic fields in the environment. Your phone is constantly pulsing with signals. Your TV remote broadcasts infrared. Power lines hum with 60 Hz AC current. Your Wi Fi router blasts data through the air. All of this invisible electromagnetic noise is happening around you constantly, but you've never heard it because human ears can't detect it. The Demon Box fixes that. It converts the frequency and intensity of electromagnetic signals into MIDI data and control voltage—the digital language that synthesizers understand.

This is genuinely innovative from both a technical and conceptual perspective. On the technical side, building stable electromagnetic sensors that can reliably detect and convert environmental EMF signals is non-trivial engineering. The device needs to differentiate between different types of radiation, handle varying signal strengths, and convert analog electromagnetic data into digital MIDI/CV information that's musically meaningful.

On the conceptual side, the Demon Box asks a fascinating question: what if all this invisible electromagnetic pollution could be repurposed as raw material for music? It's a form of found-sound composition, but instead of finding sounds in the natural world (like field recordings of rain or traffic), you're finding sounds in the electromagnetic spectrum. You're literally playing the world's background radiation.

What's particularly clever is that the Demon Box isn't just a standalone instrument. Because it outputs MIDI and CV, it can control other synthesizers. A performer could stand in a coffee shop or office building, and the signals from smartphones, laptops, and other electronics around them would become the control data for a modular synthesizer. You're performing with the ambient electromagnetic signature of your location.

The Demon Box is also notable because it's already a commercial product. Unlike most finalists, which exist in prototype form, you can actually buy a Demon Box right now. This is significant because it proves that experimental instruments aren't just academic exercises or art pieces. They can have real commercial appeal. Someone looked at this device that plays the electromagnetic spectrum and thought, "I want to buy this. I want to make music with this." And Eternal Research believes enough people will agree to manufacture and sell it.

The Guthman Competition has been a launchpad for innovative companies like Roli and Teenage Engineering, scoring high on innovation impact. (Estimated data)

The Amphibian Modules: Saltwater as Interface

Electronic music typically involves cables. You patch a synthesizer by connecting cables between modules—output to input, creating signal flow and transforming sound. It's tactile, visual, and deeply embedded in synthesizer culture. So what if you replaced cables with saltwater?

That's the core concept behind Amphibian Modules. Instead of patch cables, you use water. Saltwater conducts electricity, so it can carry control voltage signals between modules. You're literally patching your synthesizer by adding more salt water to create conductive bridges between different components.

This is audacious for several reasons. First, it's technically challenging. Water conductivity varies based on salt concentration, temperature, and chemical composition. Getting consistent, reliable electrical connection through a water medium requires careful engineering. You need to account for variations in conductivity and ensure the signal isn't degraded by the medium itself.

Second, it's conceptually powerful. Saltwater has associations with life, oceans, and organic processes. By making it the primary interface for controlling sound, the Amphibian Modules suggest a kind of musical ecosystem where the flow of salt water becomes the flow of musical information. It's not just functional; it's poetic.

Third, it creates a completely different user experience. Traditional patching happens in two dimensions—you're moving cables around on a flat panel. Amphibian Modules operates in three dimensions. You're managing the level and flow of saltwater, which changes based on gravity, evaporation, and chemical processes. Playing becomes a kind of environmental manipulation.

The technical implementation likely involves waterproof electrode connections, careful isolation of electrical components, and possibly some form of conductivity sensing to monitor the signal strength. It's the kind of problem that makes electronic engineers groan and smile simultaneously—straightforward in concept but thorny in execution.

The Gajveena: Bridging Continents and Traditions

The Gajveena represents a different kind of innovation: cultural synthesis. It combines a double bass (a Western orchestral instrument) with the traditional Indian veena, an ancient plucked string instrument with deep roots in classical Indian music.

What makes this interesting isn't just that it's a mashup of two instruments. Musical instrument fusion happens all the time. What's interesting is the intentionality behind it. The Gajveena isn't trying to create something new by accident; it's trying to create a genuine bridge between two distinct musical traditions.

The veena is one of the oldest stringed instruments in the world, with a history stretching back thousands of years. It's tuned using a system based on ragas—melodic frameworks that define scales, note relationships, and expressive techniques specific to Indian classical music. The double bass is a product of Western orchestral tradition, with its own tuning systems, repertoire, and techniques.

On paper, combining them seems absurd. The tuning systems don't align. The playing techniques are incompatible. The cultural associations are entirely different. But the Gajveena takes that apparent incompatibility as a starting point for creation. By physically linking these two instruments, it asks: what happens when these traditions speak to each other? What's possible in the spaces between them?

From a technical perspective, the Gajveena probably involves carefully integrating the resonating chambers, bridge systems, and string configurations of both instruments into a single playable form. This isn't trivial. The acoustic properties of each instrument depend on precise geometric relationships. Combine them incorrectly and you get neither instrument's best qualities—just mud.

But when it works, the Gajveena creates something genuinely new. A musician trained in both traditions (or willing to learn) could navigate between Western and Indian classical techniques, using the same instrument to access both musical universes. It's a physical manifestation of musical globalism.

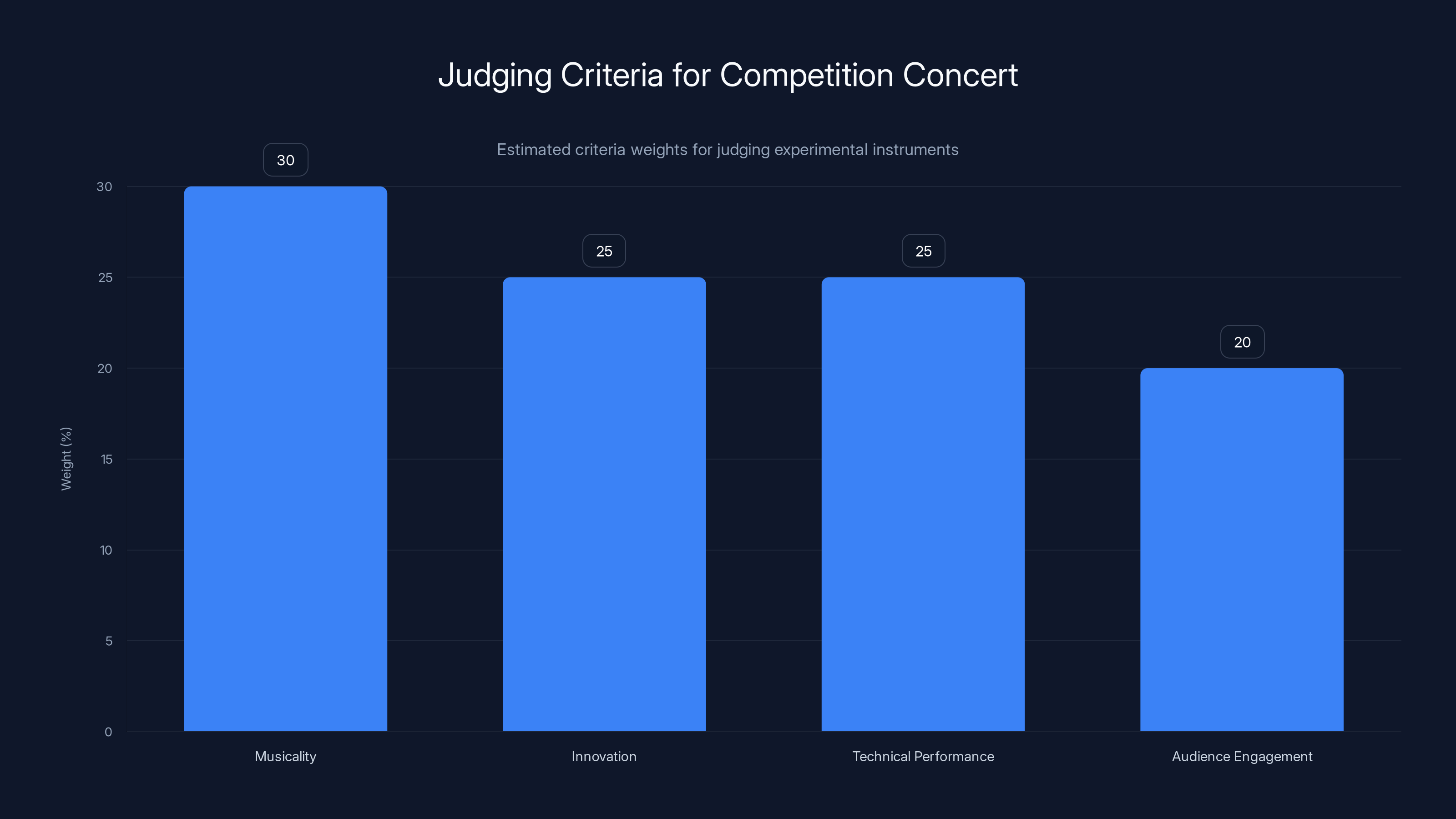

Judges likely weigh musicality most heavily, followed by innovation and technical performance. Audience engagement is also a key factor. Estimated data based on typical judging processes.

The Lethelium: Bikes, Harps, and Percussion Fusion

The Lethelium demonstrates how everyday objects can become musical raw material. It's constructed from a bike wheel, transformed into a hybrid steel drum and harp.

Bike wheels are circular, geometric, and structurally elegant. They have natural resonance properties—hit one and it rings. The Lethelium takes that ringing and amplifies it through harp-like string configurations. You're essentially creating acoustic resonance chambers out of repurposed bike parts.

This kind of instrument design—using found or repurposed materials—has roots in experimental music history. Harry Partch, a 20th-century American composer, built many of his instruments from everyday materials. The Lethelium follows that tradition, asking: why buy expensive materials when the world is full of fascinating objects that already have acoustic properties?

The practical benefit is cost and sustainability. Bike wheels are cheap and abundant. Transforming them into instruments is a form of creative recycling. But the artistic benefit is equally important. There's something powerful about an instrument made from something that previously had a completely different purpose. It tells a story about resourcefulness and imagination.

From a player's perspective, instruments made from unexpected materials often have unexpected sonic characteristics. A steel drum made from a bike wheel might have harmonic quirks that a traditional steel drum doesn't have. Those quirks become part of the voice of the instrument. They're features, not bugs.

The Masterpiece: Accessibility Through Innovation

Whereas most finalists prioritize novelty or technical innovation, the Masterpiece leads with accessibility. It's an open-source RFID-enabled synthesizer explicitly designed for musicians with disabilities.

Traditional synthesizer interfaces assume standard human embodiment. Keyboards require fine finger motor control. Patch cables require two hands and precise coordination. Knobs and sliders assume the ability to reach, grasp, and rotate. None of these assumptions hold for all musicians. Someone with limited hand mobility, coordination differences, or other disabilities might find traditional synthesizers inaccessible or frustrating to use.

The Masterpiece addresses this by using RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) technology. RFID tags are small chips that emit a unique ID when scanned. By placing RFID tags at different positions around the instrument, a musician can control parameters simply by moving an RFID reader. There's no fine motor control required. No complex coordinate system. Just move the reader over different zones, and the instrument responds.

The genius here is accessibility through technology, not accommodation. The Masterpiece doesn't require a disabled musician to adapt to a synthesizer designed for able-bodied players. Instead, it's specifically designed around different ways of interacting with sound. It's genuinely inclusive design, not an afterthought.

Being open-source is crucial. It means other builders and musicians can study how it works, modify it for specific needs, and contribute improvements. One musician might need buttons instead of RFID scanning; another might need voice controls. With an open-source design, those variations can be created, shared, and built upon.

Estimated data shows diverse innovations among 2026 finalists, with a notable focus on accessibility and unique sound production methods.

The Innovation Ecosystem: How These Instruments Happen

Creating instruments like these requires specific conditions. You need technical knowledge (electronics, acoustics, mechanics), artistic vision (what should this sound like?), and usually some form of financial support (prototyping is expensive).

Many of the finalists likely came from academic or institutional backgrounds. Universities increasingly support experimental music research. They have maker spaces, 3D printers, electronics labs, and access to expertise across disciplines. A student with an idea can collaborate with engineers, artists, and musicians to bring it to life.

The 2026 finalists also benefit from the democratization of hardware. A decade ago, building a custom synthesizer required specialized knowledge and expensive components. Now, platforms like Arduino and Raspberry Pi make digital electronics accessible. 3D printing makes custom mechanical components affordable. Open-source software handles the complex digital signal processing.

This accessibility is crucial. It lowers the barrier to entry for exactly the kind of creative people who create Guthman finalists. Someone with a great idea but limited resources can now prototype it without needing venture capital or institutional backing.

That said, creating a competitive finalist still requires dedication. Each instrument represents hundreds of hours of design, iteration, prototyping, and refinement. The creators have spent considerable time thinking about their sonic goals, their technical constraints, and how to bridge the gap between concept and reality.

The Musicality Question: Can These Actually Play Music?

It's a fair question, and it gets to something important: is an instrument judged by its novelty or its musicality?

The answer, based on how the Guthman Competition works, is both. An instrument can be technically innovative but musically uninteresting. Conversely, an instrument can be wonderfully musical but not particularly novel. The winners tend to be instruments that achieve both.

Fiddle Henge, for example, is visually striking, but does it make beautiful music? Does it enable expressive, nuanced playing? Those are separate questions from whether the concept is clever. A great experimental instrument should do both. It should be innovative in concept but also capable of genuinely interesting music-making.

The Demon Box is interesting here because it works in a musical context. Yes, the concept is wild—playing with electromagnetic radiation. But does it enable musicians to create meaningful compositions? The fact that it outputs MIDI and CV means a trained electronic musician can use it to control sophisticated sounds. It's not just a novelty; it's a new interface for creative control.

Similarly, the Masterpiece isn't just about accessibility. It also needs to be a genuinely capable synthesizer. Being accessible is necessary but not sufficient. It also has to enable musicians to express themselves sonically.

This balance—between innovation and musicality, between concept and execution—is what separates Guthman finalists from countless experimental instruments that never get beyond proof-of-concept.

Fiddle Henge consists of 40% violins, 20% bass drum, 30% spinning disk, and 10% structural support, highlighting its unique design. Estimated data.

From Prototype to Product: The Commercial Path

Most experimental instruments live in the realm of art or academic research. They get played once at a festival or conference, then disappear. But the most successful ones find a path to commercial viability.

The Demon Box is a clear example. It started as an experimental idea, was refined into a playable instrument, and eventually evolved into a commercial product. Eternal Research decided there was enough interest from experimental musicians and synthesizer enthusiasts to justify manufacturing and selling it at $999.

That price point is interesting. It's not cheap, but it's not wildly expensive for a specialized instrument. It positions the Demon Box as accessible to serious hobbyists and professional musicians, but not impulse-purchase territory. The price signals that this is a real instrument for real music-making, not a novelty gimmick.

For other finalists, the path to commercialization would be different. Fiddle Henge probably won't be mass-produced, but a builder could create limited runs for experimental music venues and avant-garde performers. The Masterpiece's open-source nature means it might never have a single commercial distributor. Instead, individuals and institutions might build their own versions, potentially with modifications for specific users.

The Lethelium and Gajveena could theoretically find boutique markets. There are small but passionate communities around experimental and world music instruments. Concert halls, experimental music ensembles, and world music groups might commission custom instruments or seek them out.

The Judging Criteria: What Makes a Winner?

How does a panel of experts decide which experimental instrument is "best" when they're all so different?

The Guthman judges typically consider several dimensions:

Innovation: How genuinely novel is the instrument? Does it introduce concepts or techniques that don't exist elsewhere? Fiddle Henge is innovative because it's a new way to interface with violins. The Demon Box is innovative because converting EMF to music is a conceptual leap.

Musicality: Can it actually make interesting music? Is it an instrument a musician would want to play, or is it just a concept? The innovation is meaningless if the resulting sounds aren't compelling.

Technical Execution: Is it well-built? Does it work reliably? Can it be reproduced or iterated? A brilliant concept that falls apart after five minutes of playing isn't competitive.

Potential Impact: Does this instrument point toward a future direction for music? Does it suggest possibilities that other inventors might explore? Does it change how people think about music-making?

Accessibility: Related to the Masterpiece, but also broader—does this instrument expand the circle of who can make music? Does it lower barriers or create new possibilities for expression?

The judges have to weigh these dimensions against each other. An instrument might be incredibly innovative but hard to play. Another might be more intuitive and musical but less conceptually groundbreaking. Part of the competition's value is watching judges navigate these tradeoffs and ultimately choose the instruments they believe matter most.

Historical Context: Where Experimental Instruments Come From

The Guthman finalists didn't emerge from nowhere. They're part of a long history of musical innovation and experimentation.

In the early 20th century, composers like Luigi Russolo and John Cage expanded what counts as music by incorporating non-traditional sound sources. Russolo's Art of Noises literally argued that industrial sounds could be musical material. Cage created instruments like the prepared piano (a standard piano with objects placed on its strings) that transformed the instrument into something entirely new.

Electronic music in the 1960s and 70s generated another wave of instrument innovation. The Moog synthesizer, Buchla, and ARP instruments didn't just produce new sounds—they created entirely new interfaces for musical control. Instead of playing keys on a keyboard, you could patch cables between modules, creating signal flows that shaped sound.

More recently, experimental music has become increasingly interdisciplinary. Artists bring expertise from electronics, software, mechanics, physics, and other fields into music-making. The result is instruments that might have seemed impossible or absurd even a decade ago.

The Guthman Competition sits in this tradition. It's not inventing the concept of experimental instruments. It's recognizing and celebrating the best contemporary examples of inventors pushing the boundaries of what instruments can be.

The Role of Academic Institutions

Georgia Tech hosting this competition is significant. Universities have become crucial incubators for experimental music research and development.

Universities have resources: maker spaces, labs, faculty expertise across disciplines, and financial support for research. They have permission to experiment and fail without immediate commercial pressure. A music student can spend a semester building a weird instrument and call it academic research. In the commercial world, that's wasted time. In academia, it's exploration.

Georgia Tech's emphasis on this competition signals that experimental instrument design is valued as legitimate scholarship. It's not a frivolous side project. It's serious creative and technical work deserving of institutional support and recognition.

Other universities have similar programs. MIT has its Media Lab, which includes experimental music research. Dartmouth has its Digital Music lab. But Georgia Tech's explicit, annual competition demonstrates a sustained commitment to instrument innovation as central to the institution's mission.

This matters for the finalists too. Being selected for a Georgia Tech competition carries academic credibility. It signals to potential employers, collaborators, and investors that you're serious about this work. It's the difference between "I built a weird instrument" and "I'm a Georgia Tech Guthman finalist." The latter opens doors.

The Community of Experimental Musicians

These instruments don't exist in isolation. There's a growing community of experimental musicians, instrument builders, and sound artists who follow the Guthman Competition and similar events.

This community includes concert venues that specialize in experimental music, festivals focused on new instruments and techniques, and networks of musicians who actively seek out new sonic possibilities. It includes record labels that release music made on experimental instruments. It includes academies and centers of electronic music like IRCAM in Paris or the Institute of Electronic Music and Acoustics in Graz, Austria.

The Guthman Competition serves as a nexus for this community. It's where new instruments get discovered and celebrated. It's where builders get exposure to potential collaborators, performers, and supporters. It's where the ideas that will shape experimental music for the next few years originate.

Participants in this community tend to share certain values: a belief that tradition is important but not restrictive, that experimentation is worthwhile even when it fails, that making music is fundamentally about exploring possibilities, and that anyone with dedication can create new instruments.

Looking Forward: What These Instruments Tell Us About Music

The 2026 finalists point toward several trends in experimental music and instrument design.

Integration of Technology and Physicality: Most finalists combine digital and mechanical elements. The Demon Box uses electromagnetic sensors and MIDI output. Fiddle Henge uses a mechanical spinning disk to create friction. The Amphibian Modules uses saltwater as an interface. These instruments refuse to be purely electronic or purely acoustic. They're hybrids that leverage both possibilities.

Accessibility and Inclusivity: The prominence of the Masterpiece signals that experimental music is increasingly focused on expanding access and inclusion. Future instruments will probably continue this trend, creating tools that let more people, with different abilities, participate in music-making.

Conceptual Innovation: The Demon Box especially demonstrates that the innovation isn't just sonic. It's conceptual. The instrument works because the idea—making invisible electromagnetic radiation audible—is compelling. This suggests future instruments will focus as much on new ideas as on new techniques.

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration: Nearly all finalists involve expertise from multiple fields. Musicians working with engineers, artists working with programmers, traditional instrument makers working with digital designers. This interdisciplinarity seems essential.

Affordability and Accessibility of Tools: 3D printing, Arduino, open-source software—these tools make instrument building more accessible. Future finalists will probably push even further in leveraging cheap, available technology to create remarkable instruments.

The Competition Concert and Judging Process

On March 14th, the finalists will perform at a competition concert. This is where the instruments prove themselves in a live setting. Anyone can submit an innovative design, but can it actually work when played in front of an audience?

The concert becomes a high-stakes performance. The Gajveena needs to actually blend the two musical traditions convincingly. Fiddle Henge needs to produce compelling music, not just curious sounds. The Demon Box needs to respond to its electromagnetic environment and create something listeners find interesting.

Performing experimental instruments live is challenging. You don't have the luxury of edits or retakes. Technical failures become part of the performance. But that's also part of the appeal. Live experimental music has an edge and unpredictability that recorded music can't capture. You never quite know what will happen, and that uncertainty is part of the listening experience.

After the performances, judges will deliberate and select a winner. That winner receives $10,000 and the prestigious Guthman designation. But equally important, they get exposure. Media coverage, word-of-mouth publicity, and the attention of musicians, composers, and institutions interested in experimental work. For many winners, that visibility is more valuable than the prize money.

Why This Matters: The Bigger Picture

You might ask: why does this matter? Why should anyone care about experimental instruments when there are countless traditional instruments that make beautiful music?

The answer is about the future. Every instrument that exists today was once experimental. The piano was radical when it was invented. The electric guitar seemed like a heresy to acoustic purists. The synthesizer was thought of as a novelty that would never replace real instruments. Yet all of these instruments became foundational to music.

The instruments at the Guthman Competition are tomorrow's standards. The concepts they introduce—new interfaces, new ways of thinking about sound, new approaches to accessibility—will ripple outward. Other builders will iterate on these ideas. Composers will write for these instruments. Musicians will integrate them into established genres. What seems wild and experimental in 2026 might be commonplace in 2036.

More broadly, experimental instruments represent a fundamental human impulse: to explore, to create, to push boundaries. Music is one of our oldest and most essential technologies. That we continue to innovate and experiment with it suggests something important about human nature. We're not satisfied with the status quo. We want to find new possibilities, ask new questions, and discover what hasn't been discovered.

The Guthman Competition celebrates that impulse. It says: your weird idea matters. Your unconventional approach is valuable. Your experimental instrument might change music. That's powerful validation for creators who are working outside traditional structures.

Conclusion: From Fiddle Henge to the Future

Georgia Tech's 2026 Guthman finalists represent something remarkable: the frontier of musical innovation. These aren't incremental improvements. They're genuine category-busting creations that force us to reconsider what music can be, who can make it, and how we interact with it.

Fiddle Henge shows that you can deconstruct a familiar instrument and reassemble it into something entirely new. The Demon Box reveals that invisible environmental signals can become musical material. The Masterpiece proves that accessibility and innovation can be unified, not competing values. The Amphibian Modules and Lethelium demonstrate that everyday objects and natural materials can be transformed into sophisticated instruments. The Gajveena bridges continents and traditions, suggesting that musical innovation is global and collaborative.

Together, these instruments tell a story about where music is heading. It's a future where technology and physicality coexist. Where innovation serves inclusion and accessibility. Where concepts matter as much as execution. Where anyone with dedication and imagination can create instruments that deserve to be heard.

The competition concert on March 14th will determine which of these instruments the judges believe matters most. But in a deeper sense, all of them already matter. They're all expanding what's possible in music. They're all proving that experimentation is alive and well. They're all showing that the future of music will be stranger, more inclusive, and more creative than the past.

For anyone interested in music, technology, or creative innovation, the Guthman Competition is essential watching. It's where you see the next generation of instruments being born. It's where you witness the future of music taking its first steps. And it's where you remember that human creativity, when combined with technical skill and bold vision, can still produce something genuinely, audaciously new.

The winner will be announced on March 14th. But regardless of who takes the prize, everyone watching will have glimpsed what's possible when someone decides that existing instruments aren't enough—that music deserves new voices, new approaches, and new possibilities. And in that realization lies the true value of the Guthman Competition.

FAQ

What is the Guthman Musical Instrument Competition?

The Guthman Musical Instrument Competition is Georgia Tech's annual awards program that invites inventors and musicians from around the world to submit original musical instruments for evaluation and performance. Established nearly 30 years ago, it's recognized as one of the premier competitions for experimental and innovative instrument design, offering $10,000 in prizes and significant prestige within the experimental music community.

How does the Guthman Competition work?

The competition operates through an annual submission process where inventors submit designs and prototypes of new instruments. Georgia Tech staff and advisors review submissions and select approximately 10 finalists. These finalists are invited to perform their instruments at a competition concert, where judges evaluate them based on innovation, musicality, technical execution, and potential impact. A winner is selected at the conclusion of the concert, receiving the prize and widespread recognition.

What are the judging criteria for instruments at the competition?

Judges typically evaluate instruments across several dimensions: technical innovation (how genuinely novel is the concept), musicality (can it actually make interesting music), technical execution (is it well-built and reliable), potential impact (does it suggest future directions for music), and accessibility (does it expand possibilities for who can make music). The judges weigh these factors differently for each instrument, looking for those that excel across multiple dimensions.

Who can submit instruments to the Guthman Competition?

The competition is open to inventors, musicians, engineers, and artists from anywhere in the world. Participants don't need to be professional musicians or formally trained in music—many finalists come from engineering, art, or other non-musical backgrounds. The only requirement is having created an original musical instrument and being able to demonstrate it at the competition concert.

What happened to past Guthman winners and finalists?

Many past finalists and winners have gone on to significant careers in music technology. Finalists have included founding members of companies like Teenage Engineering, Artiphon, and Roli, all of which became influential manufacturers of modern musical instruments. Winners like KOMA Elektronik have used the competition's prestige to build successful commercial businesses. For many participants, the recognition and visibility from the Guthman Competition is transformative for their careers.

Why does an academic institution like Georgia Tech host this competition?

Georgia Tech supports experimental instrument design as legitimate research and creative work. Universities provide essential resources (labs, maker spaces, technical expertise) and institutional credibility that enable experimental musicians and builders to pursue innovative projects. By hosting the competition annually, Georgia Tech signals that instrument innovation is valued as serious scholarship and worthy of support, attracting talented inventors and fostering a community of experimental musicians.

Are these experimental instruments ever commercially produced?

Some finalists and winners do reach commercial production. The Demon Box, created by Eternal Research, is available for purchase at $999. Other finalists might receive commissions from concert halls or experimental music ensembles. Many remain limited runs or custom instruments. The Masterpiece's open-source design means people can build their own versions. Commercial viability varies, but some experimental instruments do successfully transition from prototype to product.

How do these experimental instruments contribute to music more broadly?

Experimental instruments represent the frontier of musical innovation. Many instruments considered traditional today were once radical experiments. The piano, electric guitar, and synthesizer all emerged from experimentation and skepticism. By developing new interfaces, sound sources, and ways of making music, experimental instruments influence the musical instruments and techniques that become mainstream. They also expand access to music-making, suggest new compositional possibilities, and keep music alive as an evolving, innovative practice.

When is the 2026 competition concert?

The 2026 Guthman Musical Instrument Competition concert is scheduled for Saturday, March 14th. At this performance, the finalists will demonstrate their instruments, and judges will evaluate and select the winner. The competition concert is a crucial moment where experimental instruments prove themselves in live performance before an audience and expert judges.

How can I stay updated on the competition and experimental instruments?

Georgia Tech maintains information about the Guthman Competition on its official website and announces winners and finalists through press releases and media coverage. Following experimental music venues, academic institutions with music programs, and music technology publications provides ongoing coverage of instrument innovation. The experimental music community actively shares information about competitions, new instruments, and upcoming performances through festivals, concert series, and online communities dedicated to electronic and experimental music.

This article was created to provide comprehensive insights into Georgia Tech's Guthman Musical Instrument Competition and the remarkable 2026 finalists who are pushing the boundaries of what instruments can be.

Key Takeaways

- The Guthman Competition has discovered boundary-pushing instruments for 28 years, with past winners now founding major music tech companies like Teenage Engineering and Artiphon

- 2026 finalists include Fiddle Henge (spinning violin henge), Demon Box (EMF-to-music converter at $999), and Masterpiece (RFID synthesizer for musicians with disabilities)

- These instruments represent innovation across multiple dimensions: conceptual novelty, technical execution, accessibility, and commercial viability

- Experimental instruments are reaching mainstream relevance as 3D printing, Arduino, and open-source tools democratize instrument building

- The competition highlights how universities, maker spaces, and institutional support enable radical musical innovation that wouldn't exist otherwise

Related Articles

- Vape Synth: How Hackers Turn E-Waste Into Music [2025]

- Mandy, Indiana URGH Album Review: Why This Record Matters [2025]

- Spotify's About the Song Feature: What You Need to Know [2025]

- M83's Dead Cities, Red Seas & Lost Ghosts: The Post-Rock Masterpiece You Need to Hear [2025]

- Deezer's AI Music Detection Tool Goes Commercial [2025]

- Roland TR-1000 Drum Machine: Ultimate Guide [2025]

![Georgia Tech's Guthman Competition: The Future of Experimental Instruments [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/georgia-tech-s-guthman-competition-the-future-of-experimenta/image-1-1771088775954.jpg)