Introduction: From Trash to Sonic Art

When you finish a disposable vape cartridge, you're tossing out far more than flavored nicotine vapor. You're throwing away a lithium-ion battery, a precision circuit board, a plastic case, a pressure sensor, and a handful of other components that could theoretically live a second life. Millions of these devices end up in landfills every year, contributing to a growing e-waste crisis that few people talk about outside of environmental circles.

But what if that dead vape could play music?

That's exactly what a group of makers and artists in New York City set out to discover. The Vape Synth project, created by academics and tinkerers working under the collective name Paper Bag Team, takes discarded Elf Bar vaporizers and transforms them into functional digital musical instruments. The concept sounds absurd—and it's meant to be. By wrapping serious environmental critique in a layer of deliberate silliness, the team makes both hacking and sustainability feel accessible rather than preachy.

The result is a device that still looks like a vape cartridge from the outside, complete with a mouthpiece you'd recognize. But inside, it's been gutted and rewired. A small speaker nestles among an array of programmable buttons and lights. When you draw breath through the mouthpiece, you're not inhaling anything. Instead, you're activating a low-pressure sensor that triggers an oscillator circuit. Different button combinations produce different tones. The sounds are deliberately chaotic—screechy, unpredictable, and intentionally goofy.

This isn't just a novelty project or art school performance piece. It's a genuine statement about e-waste, right-to-repair, maker culture, and how we think about technology as disposable. It sits at the intersection of environmental consciousness and creative expression, proving that the trash of our consumer culture can be reclaimed as the canvas of artistic experimentation.

Over the past year, the Vape Synth has appeared at maker fairs, hacker conferences, and open hardware summits. The team has published detailed instructions on Instructables, run workshops across the country, and demonstrated that with basic electronics knowledge and a willingness to solder something unconventional, almost anyone can hack a dead vape into an instrument.

This article explores the Vape Synth project in depth: the story behind it, how it actually works, what it means for e-waste activism, the broader maker culture that enabled it, and what lessons it holds for the future of sustainable electronics and DIY creation.

TL; DR

- Dead vapes are being hacked into playable synthesizers by NYC-based makers using the Vape Synth project, turning e-waste into musical instruments

- The hack repurposes the vape's existing pressure sensor and battery, using breath to trigger oscillators and buttons to select different tones

- Paper Bag Team deliberately embraces silly aesthetics to make environmental and right-to-repair activism more approachable and fun rather than preachy

- Vape recycling is almost nonexistent in the US, meaning millions of devices with functional batteries and circuits end up in landfills annually

- The project has sparked a broader maker movement, with workshops, conferences, and public instruction guides encouraging others to hack their own vape synths

Elf Bar and Puff Bar lead the disposable vape market, capturing a significant portion of sales. Estimated data.

The E-Waste Crisis Behind the Joke

Disposable vape devices represent one of the fastest-growing streams of electronic waste in the United States. When the FDA forced Juul—once the dominant player in the vaping market—to pull its products from shelves, it created a vacuum that was immediately filled by dozens of disposable alternatives. Brands with names like Elf Bar, Lost Mary, Hyppe, and Puff Bar flooded convenience stores, gas stations, and online retailers worldwide.

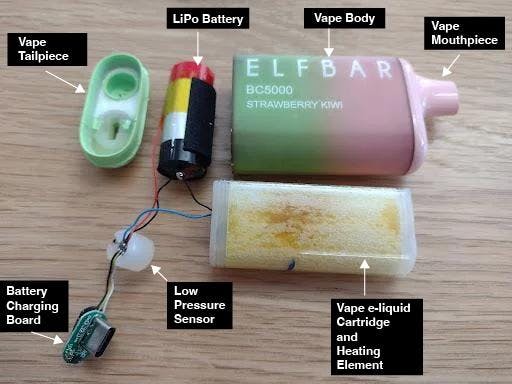

Unlike traditional cigarettes, which are designed to be consumed and discarded, vape devices contain sophisticated electronics. Inside each cartridge you'll find a rechargeable lithium-ion battery (the same type that powers smartphones), a circuit board capable of regulating temperature and power output, a pressure sensor that detects when you inhale, a heating coil made from stainless steel or nichrome wire, and plastic housing assembled with adhesive and sometimes welded seams.

The problem is scale. These devices sell in the hundreds of millions. The US vape market was valued at over $15 billion in 2023 and continues to grow despite regulatory challenges. Each device typically lasts between 2,000 and 10,000 puffs—anywhere from a few days to a few weeks depending on usage patterns—before the battery depletes and the device becomes non-functional.

Vape recycling infrastructure barely exists. The devices are too small for standard e-waste collection programs, too contaminated with nicotine residue for conventional processing, and too fragmented across hundreds of manufacturers for coordinated recycling efforts. Retailers have no legal obligation to accept dead devices. Manufacturers don't run take-back programs in most regions. As a result, the vast majority of spent vapes simply become trash.

Environmental organizations have begun documenting the scale of the problem. Used vape devices litter beaches, clog storm drains, and accumulate in landfills where their lithium-ion batteries pose fire risks. The batteries can spontaneously ignite when compressed by heavy machinery, causing unexpected fires in waste facilities. The plastic casings break down into microplastics. The metal components persist in soil for decades.

For environmental activists, disposable vapes represent a particularly frustrating example of planned obsolescence and the throwaway electronics culture. Unlike phones or laptops, which consumers typically keep for years, vapes are designed to be abandoned almost immediately after purchase. There's no upgrade path, no trade-in program, no second-hand market—just straight to the landfill.

This context—the enormous waste stream, the lack of recycling solutions, the environmental toxicity—is what makes the Vape Synth project interesting. Rather than approaching the problem with earnest despair or trite "reduce, reuse, recycle" messaging, the creators decided to make it weird and funny.

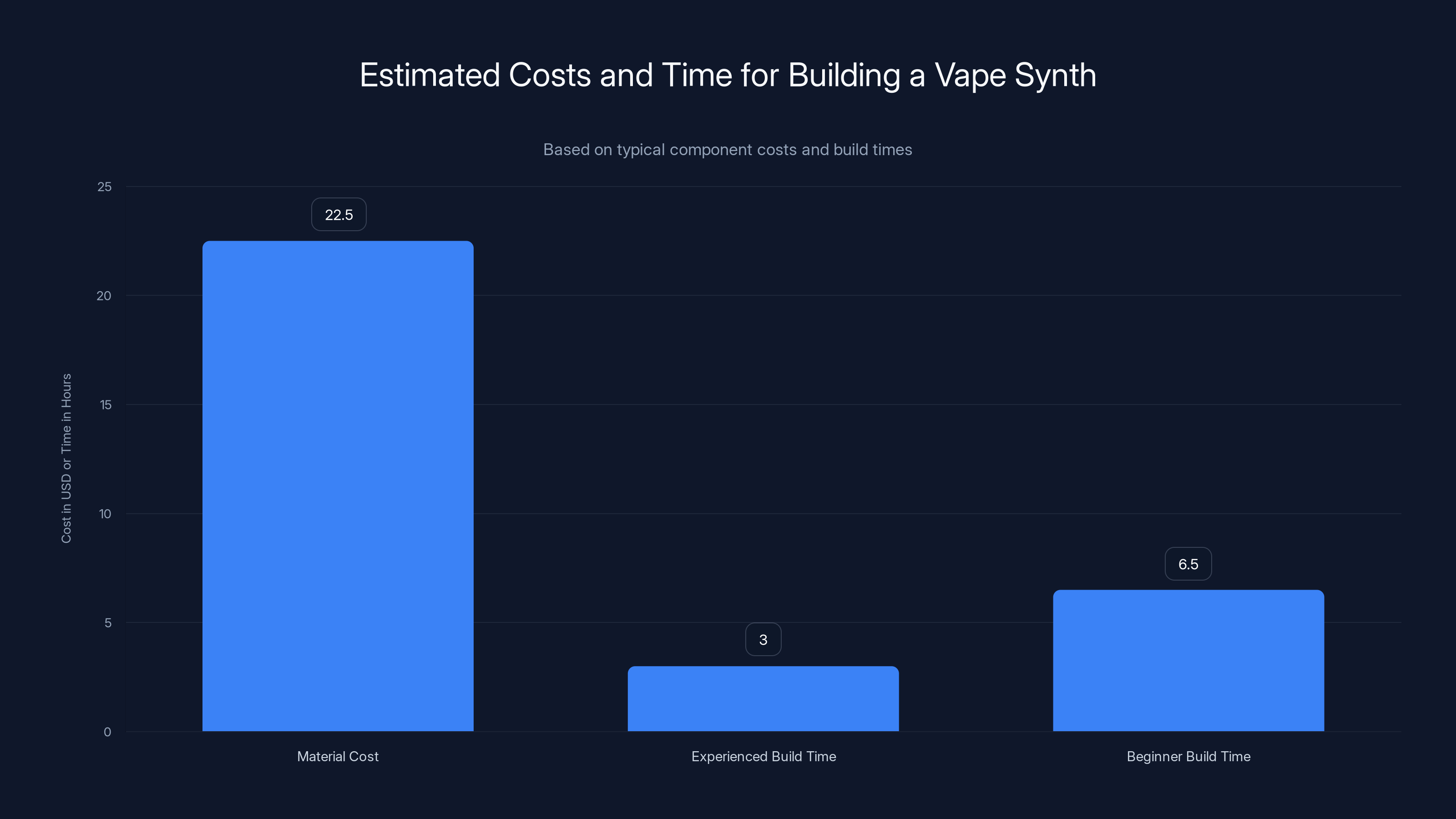

Building a Vape Synth typically costs $15-30 and takes 2-4 hours for experienced builders or 5-8 hours for beginners. Estimated data.

Meet Paper Bag Team: The Creators Behind the Hack

The Vape Synth emerged from the collision of three different people's expertise and interests. Kari Love is a professor at New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, where she teaches courses on making and creative technology. David Rios also teaches at ITP, specifically in the realm of new musical interfaces and experimental instruments. Shuang Cai is a Ph.D. student at Cornell University who also teaches at both Cornell and NYU, with a focus on electronics, sustainability, and tinkering culture.

None of them vape. None of them were trying to create a hit product or start a company. They're self-described salvage hoarders—people who collect broken electronics, waste materials, and discarded components because they see creative potential in them. They work under the collective moniker Paper Bag Team, a reference to the deliberately low-fi, lo-tech aesthetic of their projects.

The story of the Vape Synth began, somewhat accidentally, when a student came to Love with a specific request: they wanted to build a miniature fog machine. Love's immediate thought was that you could probably hack a vape to do this. She took one apart—just to explore the architecture—but the student never followed up on the project. Love was left with a disassembled vaporizer sitting on her desk, components spread out, reverse-engineered in her mind.

When she mentioned this to Rios, who had been teaching about designing new musical interfaces, something clicked. Why not turn the vape into a musical instrument? The pressure sensor was already there. The battery was already there. The plastic case could be modified. It was a perfect found-object for experimentation.

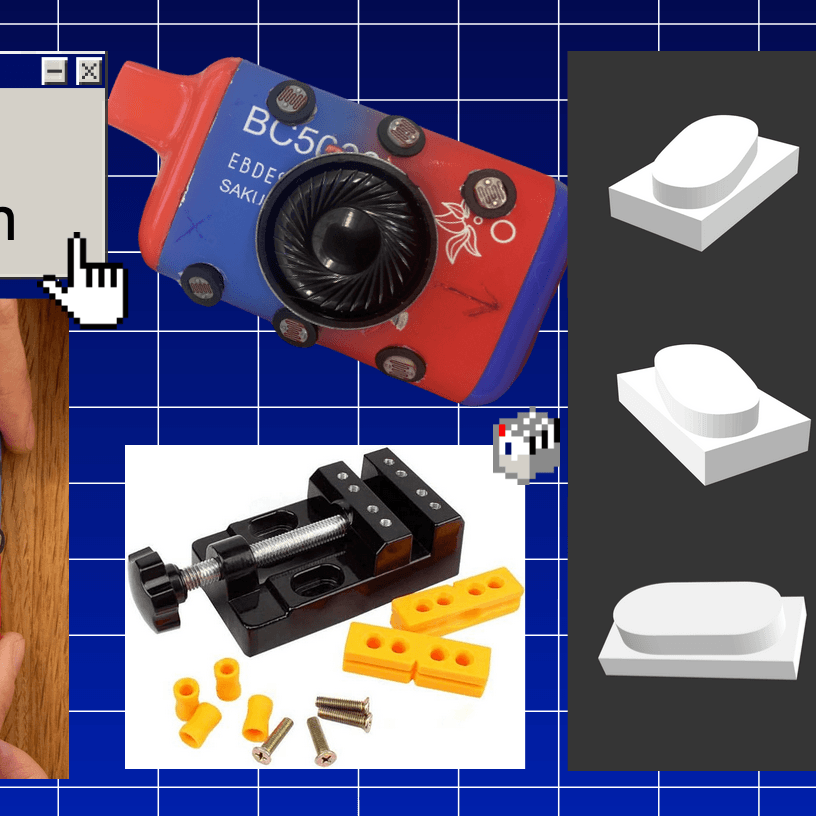

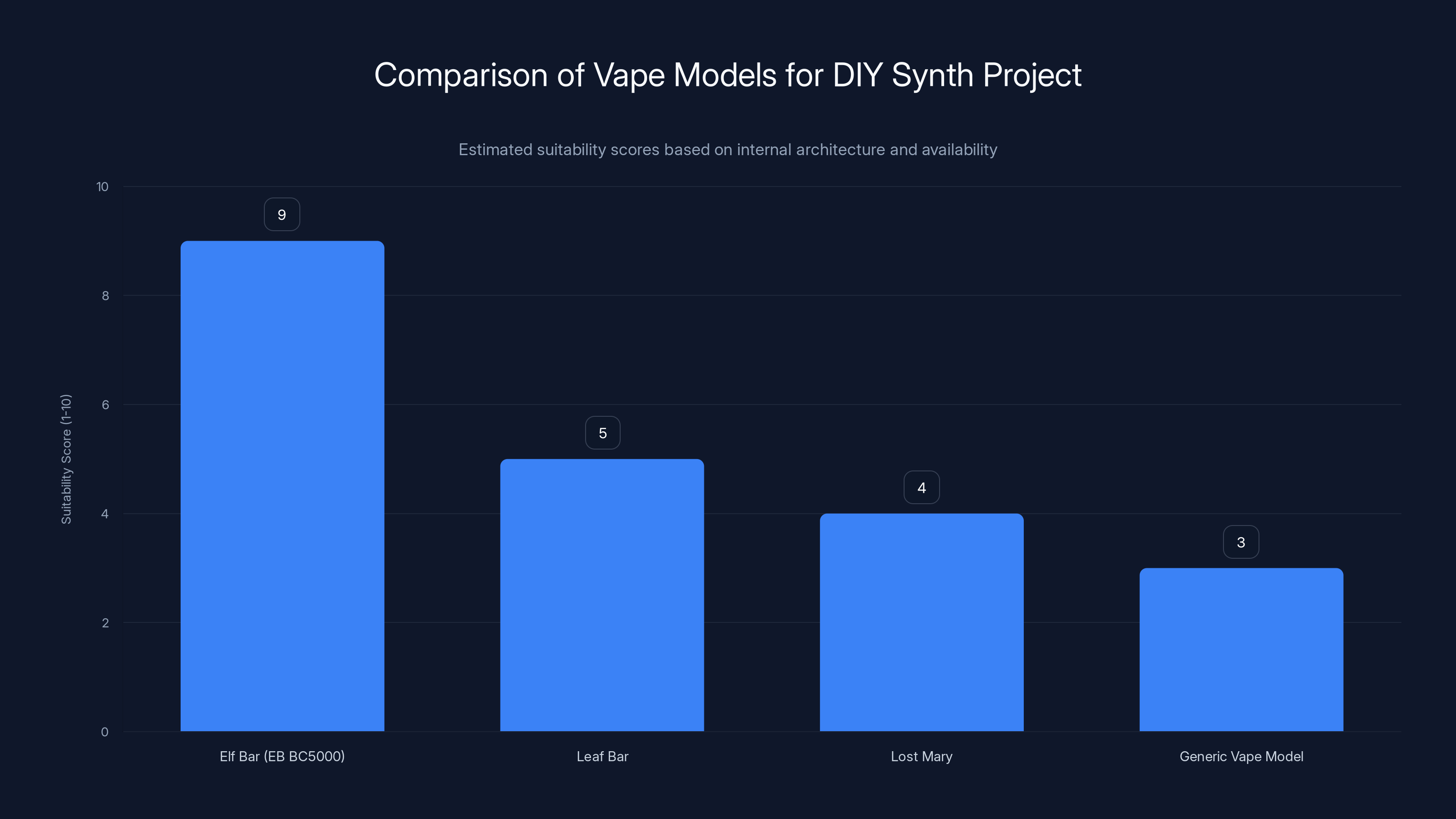

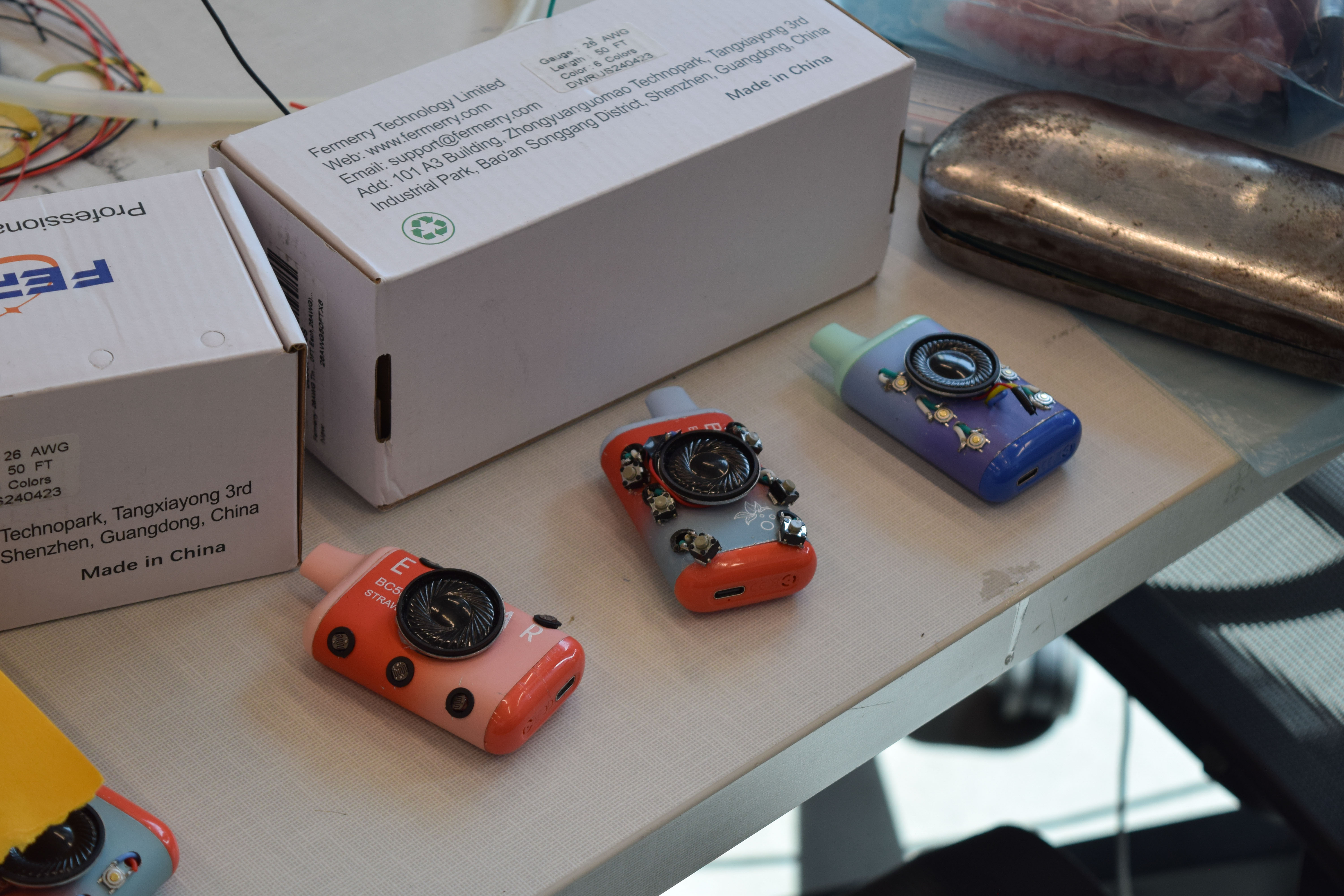

When they brought Cai into the conversation—a fellow maker with deep knowledge of electronics and a genuine passion for thinking creatively about waste—the project took shape. The three of them began experimenting with different circuit designs, button configurations, and sound synthesis approaches. They tested various vape models, settling on the Elf Bar as the ideal candidate because of its internal architecture and popularity in the US market.

Their inspiration came from an unexpected place: a philosophy articulated by hacker Andrew Quitmeyer called the "Bubble Punk" approach. The core idea is simple but profound: if you're trying to get people excited about serious issues like waste reduction, sustainability, and environmental justice, making it goofy and silly actually makes it work better. People are more likely to engage with a project that makes them laugh. Earnestness can feel preachy. Humor feels inviting.

As Cai explained in their talks about the project, this is "upstream salvage." The goal isn't to position the Vape Synth as a complete solution to the e-waste crisis—it's not. Making a few thousand musical instruments out of vapes doesn't solve the problem of millions of devices entering landfills. Rather, the project is designed to draw attention to the issue and encourage creative action on the same scale. It's consciousness-raising disguised as a joke.

The Anatomy of a Vape Synth: How It Actually Works

To understand how a dead vape becomes a playable instrument, you need to know what's actually inside one. Strip away the plastic casing and the marketing packaging, and you're looking at a surprisingly sophisticated piece of electronics.

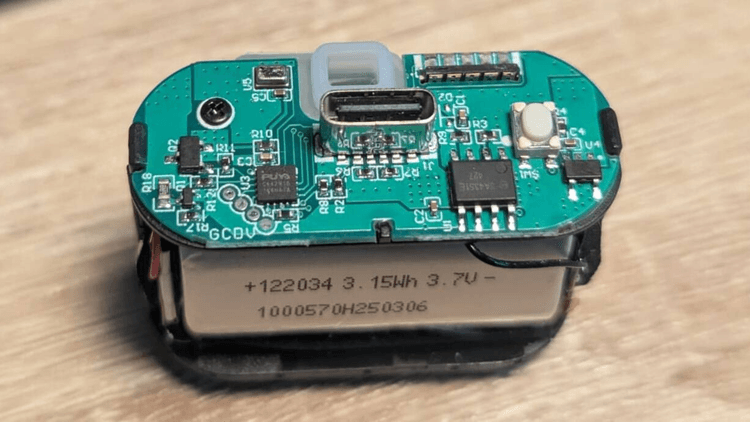

At the heart of most vape devices is a lithium-ion battery—typically a single 18650 cell or a multi-cell configuration, depending on the model. This provides the power that heats the coil and runs all the circuitry. Connected to the battery is a charging circuit with built-in protection against overcharging and over-discharging. In most cases, there's a small LED indicator that shows charging status. Most modern vapes are charged via USB-C, which means the charging circuit includes a USB controller.

The heating circuit is where the actual vaporization happens. A resistive coil (made from nichrome wire or similar material) is connected to a power supply circuit that can regulate the current flowing through it. As current flows, the coil heats to somewhere between 200 and 400 degrees Celsius, hot enough to vaporize the nicotine liquid but not so hot that it combusts.

Then there's the pressure sensor—the component that the Vape Synth exploits. When you inhale on a vape, you're creating negative pressure (lower air pressure inside your mouth than outside). This change in air pressure is detected by the sensor, which sends a signal to the circuit board saying "activate the coil." It's a simple but elegant design that allows the device to turn on only when you're actually using it, saving battery life and preventing accidental activation.

The genius of the Vape Synth hack is that it repurposes this exact sensor for a completely different purpose. Instead of triggering a heating coil, sucking on the mouthpiece triggers an oscillator—an electronic circuit that produces a continuous tone at a specific frequency. Pressing physical buttons changes which oscillator frequency is active. The result is a crude but functional synthesizer.

The circuit board that Paper Bag Team adds to the hack includes several key components. There's a microcontroller—typically an Arduino or similar platform—that reads input from the pressure sensor and the button array. This microcontroller generates square-wave or triangle-wave signals at various frequencies. These signals feed into a small amplifier, which drives a tiny speaker (usually 8-16 ohms, salvaged from old electronics or purchased cheaply).

The buttons typically include selections for different "instruments" (different waveforms or frequency sets), octave up/down controls to expand the musical range, and maybe a few effects parameters. Some versions include photoresistors—sensors that respond to light—mounted on the exterior of the case, allowing you to adjust parameters by blocking and unblocking light.

The whole assembly fits back into the original vape case. The speaker mount is carefully positioned so it doesn't rattle. The buttons are drilled through the plastic in ergonomic locations. The pressure sensor is repositioned closer to the mouthpiece to ensure it activates easily. Everything is wired to the small circuit board, which itself is powered by the vape's original battery.

Sounds-wise, the Vape Synth produces deliberately poor-quality audio. The tones are harsh, slightly metallic, and prone to aliasing artifacts (digital distortion that creates "false" frequencies). The sound has been compared to a dying rabbit, a swarm of flies hitting an electric fence, and the internal screaming of a synthesizer having an existential crisis. This aesthetic choice is intentional—it's anti-beautiful in a way that makes the project more conceptually interesting.

Love, Rios, and Cai have already begun working on a second generation of the hack that includes a wider pitch range, more sophisticated oscillator circuits, and the ability to function as a MIDI controller. This would allow the Vape Synth to trigger external synthesizers or digital audio workstations on a computer, giving it real musical potential beyond the deliberate absurdity of the original.

Runable is estimated to score high in automation features and ease of use, making it a valuable tool for creative projects. Estimated data.

Building Your Own: The Instructables Guide and Accessibility

One of the most important aspects of the Vape Synth project is that it's not gatekept. Paper Bag Team could have kept the hack proprietary, only demonstrating it at conferences and gallery installations. Instead, they published comprehensive step-by-step instructions on Instructables, one of the internet's largest DIY and maker platforms.

The Instructables guide walks you through the entire process: finding a suitable vape cartridge, safely disassembling it while handling the residual nicotine, sourcing the necessary components (a circuit board, a microcontroller, a speaker, buttons, solder, and wire), and reassembling everything into the final working instrument.

The team specifically recommends using the Elf Bar model (also known as the EB BC5000) because of its internal architecture and availability. They note that while similar devices like the Leaf Bar or Lost Mary might theoretically work, their slightly different internal dimensions make the hack more difficult and the instructions less applicable. This specificity is actually helpful—it gives people a clear target rather than asking them to figure out which of hundreds of similar devices would work best.

The assembly process itself isn't particularly complicated if you have basic soldering skills. You need to:

- Prepare the vape cartridge: Put on nitrile gloves (nicotine absorbs through skin), remove the battery by carefully prying apart the case, and clean off any remaining liquid

- Drill holes and mount components: Determine where buttons will be mounted, where the speaker will fit, and carefully drill holes without damaging the pressure sensor

- Build the circuit board: Solder the microcontroller, oscillator circuits, amplifier, and speaker together following the provided schematic

- Integrate with the vape's battery: Wire the new circuit to use the existing lithium-ion battery as the power source

- Program the microcontroller: Upload the firmware (freely available from the Instructables page) that defines which button combinations produce which sounds

- Reassemble and test: Carefully fit everything back into the plastic case and test that all buttons and the pressure sensor work correctly

The estimated build time is around 2-4 hours for someone with moderate electronics experience. Someone completely new to soldering might need 5-8 hours, including the time to learn basic technique. The cost of components (assuming you already have a soldering iron and basic tools) is roughly $15-30, far less than purchasing a commercial synthesizer.

Paper Bag Team has also run numerous workshops at maker events and conferences, including the 2025 Low Tech Electronics Faire and NYC Resistor, a famous hacker collective in Brooklyn. These in-person sessions serve multiple purposes. They remove barriers to entry—you don't have to figure out sourcing materials or troubleshooting soldering problems alone. They create community around the project. And they democratize the knowledge, ensuring that the skills and ideas aren't locked away in academic spaces.

David Rios emphasizes that a major goal of these workshops is to combat the sense of helplessness that many people feel around electronics. "People feel just completely unempowered to do anything," Rios says. "Even the most basic thing of just popping the lid open to see what's in there. You don't even have to touch it. It can be fun and easy and you can hopefully apply that to your other e-waste, or at least get interested."

This is crucial. Most people grow up treating electronics as sealed black boxes. You buy them, you use them, and when they break, you throw them away or take them to Best Buy's recycling program. The idea that you could open one up, understand its internals, and repurpose it feels transgressive or impossible. The Vape Synth project deliberately demystifies this—it shows that with basic tools and instructions, you can do something creative and meaningful with technology that would otherwise be waste.

The Broader Maker Culture Context

The Vape Synth didn't emerge in a vacuum. It's the product of a specific culture and ecosystem: the maker movement, which has been flourishing for roughly fifteen years.

The modern maker movement traces its roots to publications like "Make Magazine" (founded in 2005) and the physical spaces called "Tech Shops" and "hackerspaces" that proliferated in the 2000s and 2010s. The core philosophy is democratization of technology. Instead of technology being something that corporations design and consumers passively use, makers believe that anyone with curiosity and access to tools can design, build, repair, and modify technology themselves.

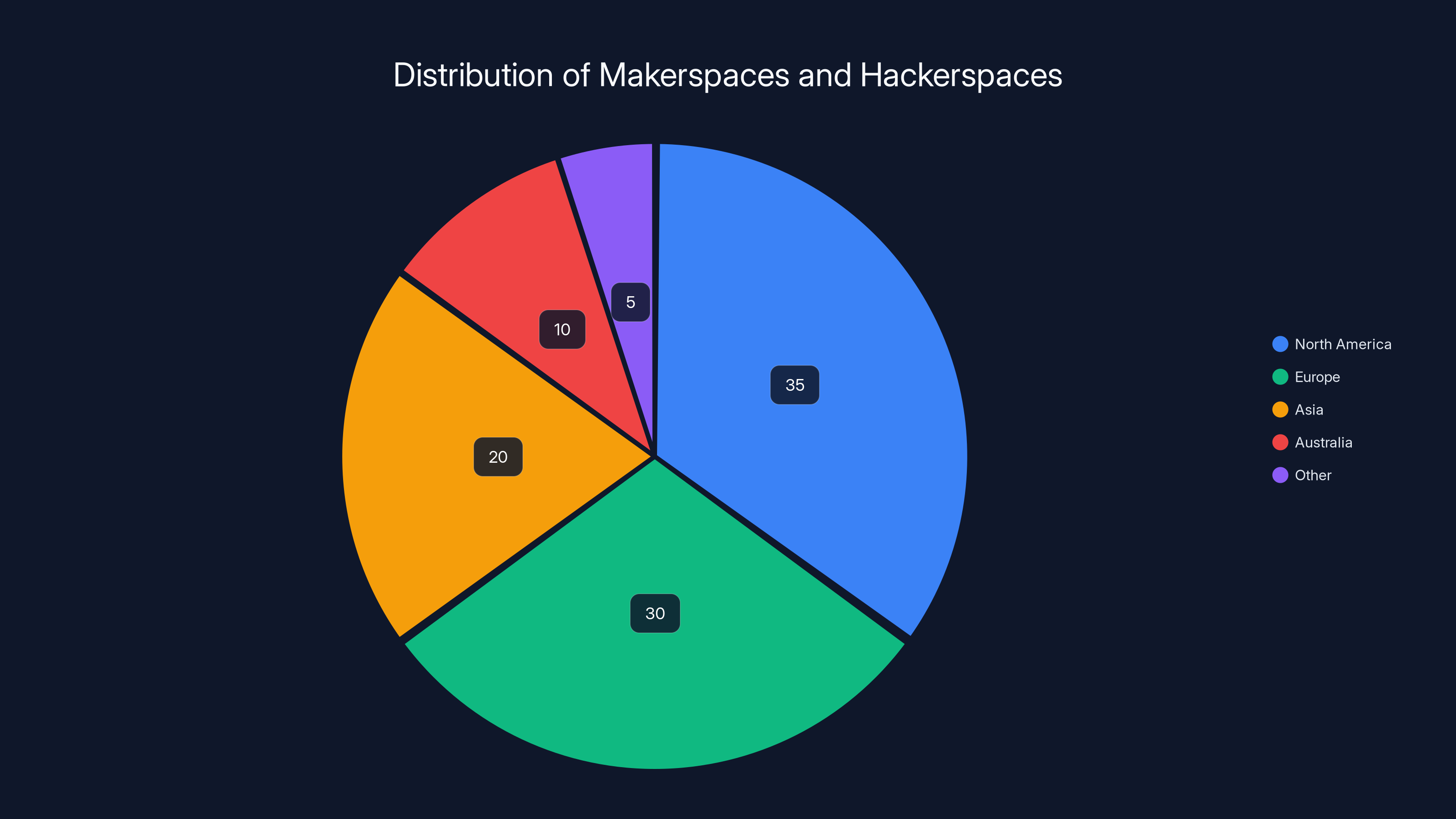

This culture has concrete instantiations in cities worldwide. In New York alone, there are several established hackerspaces including NYC Resistor, where the Vape Synth workshops have taken place. In Brooklyn, Artisan's Asylum provides tools and community. Across the US and internationally, similar spaces exist—makerspaces, community workshops, art hacker collectives. These aren't companies. They're membership-based collectives where people pay dues (usually $50-200 per month) for access to tools like soldering irons, 3D printers, laser cutters, electronics components, machine tools, and most importantly, community and knowledge-sharing.

Within this ecosystem, there's a strong strand of environmental consciousness and right-to-repair activism. Louis Rossmann, a famous electronics repair advocate, has spent years fighting for legislation that would force device manufacturers to provide spare parts and repair documentation. Right-to-Repair laws have begun passing in various jurisdictions, starting with New York's Digital Right to Repair Act (which applies to electronics). Organizations like iFixit catalog repair manuals for consumer devices, proving that fixing things is often easier than buying new ones if you just have access to information.

The Vape Synth sits comfortably within this culture. It's simultaneously art, activism, and education. It's a project about making, about environmental responsibility, about fighting against planned obsolescence, and about showing people that they have agency over technology rather than being passive consumers.

The "Bubble Punk" philosophy that inspired the Vape Synth also has roots in maker culture and hacker ethics. The idea of deliberately introducing humor, absurdity, and play into activist work comes from traditions of culture jamming, tactical media, and artistic protest. By making something funny, you bypass people's defenses. Environmental activism can feel heavy and guilt-inducing. Music-making and play are joyful. Combining the two—a project that's about environmental awareness but expresses itself through sound art and silly humor—makes it something people actually want to engage with.

The academic context matters too. ITP at NYU is specifically designed to encourage this kind of interdisciplinary, creative, socially conscious work. It's not a traditional engineering program. It attracts artists, musicians, designers, and activists who want to engage with technology critically. The program actively encourages students to build things that are weird, that question assumptions, that make people think. The Vape Synth is exactly the kind of project an ITP faculty member would likely develop and support.

The Elf Bar (EB BC5000) is highly recommended for the DIY Vape Synth project due to its optimal internal architecture and availability. Estimated data based on project requirements.

The Sound Aesthetic: Deliberately Terrible Audio

One thing that immediately strikes anyone hearing the Vape Synth for the first time is that it sounds awful. Not in the endearing way that vintage synthesizers sound. Not in the lo-fi way that bedroom pop producers intentionally embrace. The Vape Synth sounds like an electronics store's alarm system having a seizure. It's piercing, chaotic, and difficult to listen to for extended periods.

This is deliberate. The project doesn't aspire to be a musical instrument in the traditional sense. Nobody is going to record a beautiful piece of music on a Vape Synth. Instead, the harsh, unpleasant sound quality is part of the artistic statement. It emphasizes that the point isn't music-making—it's about the hack, the concept, the reuse of materials, and the activism implicit in the project.

The specific sounds produced depend on the circuit design. The most basic version generates square waves at different frequencies based on which buttons are pressed. Square waves are inherently harsh—they're the "Atari 2600" sound, the 8-bit video game aesthetic. More sophisticated versions might include sawtooth waves or triangle waves, which are slightly less grating but still metallic and electronic.

Alias artifacts also contribute to the distinctive sound. When you're generating digital tones at relatively low sample rates (which a simple Arduino-based circuit does), you inevitably produce aliasing—false frequencies that shouldn't exist. This creates a kind of digital distortion, almost like the sound is glitching or corrupting itself in real-time. It's genuinely unsettling to listen to, which is part of the charm.

Love mentions that the team is already planning a second-generation Vape Synth that will include better oscillator circuits, perhaps even a small SD card for playing back sampled sounds. But they're deliberately keeping the sound quality intentionally limited. The point isn't to create a high-fidelity instrument. The point is to create something that sounds like what it is: an experimental hack repurposing a waste product.

In this sense, the Vape Synth echoes traditions of noise music, circuit bending, and lo-fi experimental music. Artists like Merzbow have spent decades creating music from sounds that most people would consider unmusical—industrial noise, distortion, corruption, feedback. The Vape Synth sits in a similar tradition, using unpleasant sounds to make a statement about technology, waste, and creative agency.

E-Waste Activism and the Vape Problem

The Vape Synth project is ultimately rooted in e-waste activism, specifically focused on the massive problem of disposable vapes. To understand why Paper Bag Team considers this such an important issue, you need to understand the scale and implications of the vape e-waste crisis.

Disposable vape devices have become ubiquitous in a remarkably short timeframe. A decade ago, they barely existed. Today, they're sold in virtually every convenience store in America. The market has exploded partly because of regulatory gaps—disposable devices exist in a strange space where the FDA regulates them as tobacco products but enforcement is sporadic and many brands simply operate in gray areas or move faster than regulation can catch up.

The result is that vapes have become the fastest-growing consumer electronics product in some regions. Studies suggest that the average teenager in urban areas sees vape advertisements far more frequently than cigarette ads (which are heavily regulated). The devices are cheap to produce, profitable to sell, and highly addictive because the nicotine concentrations are often very high.

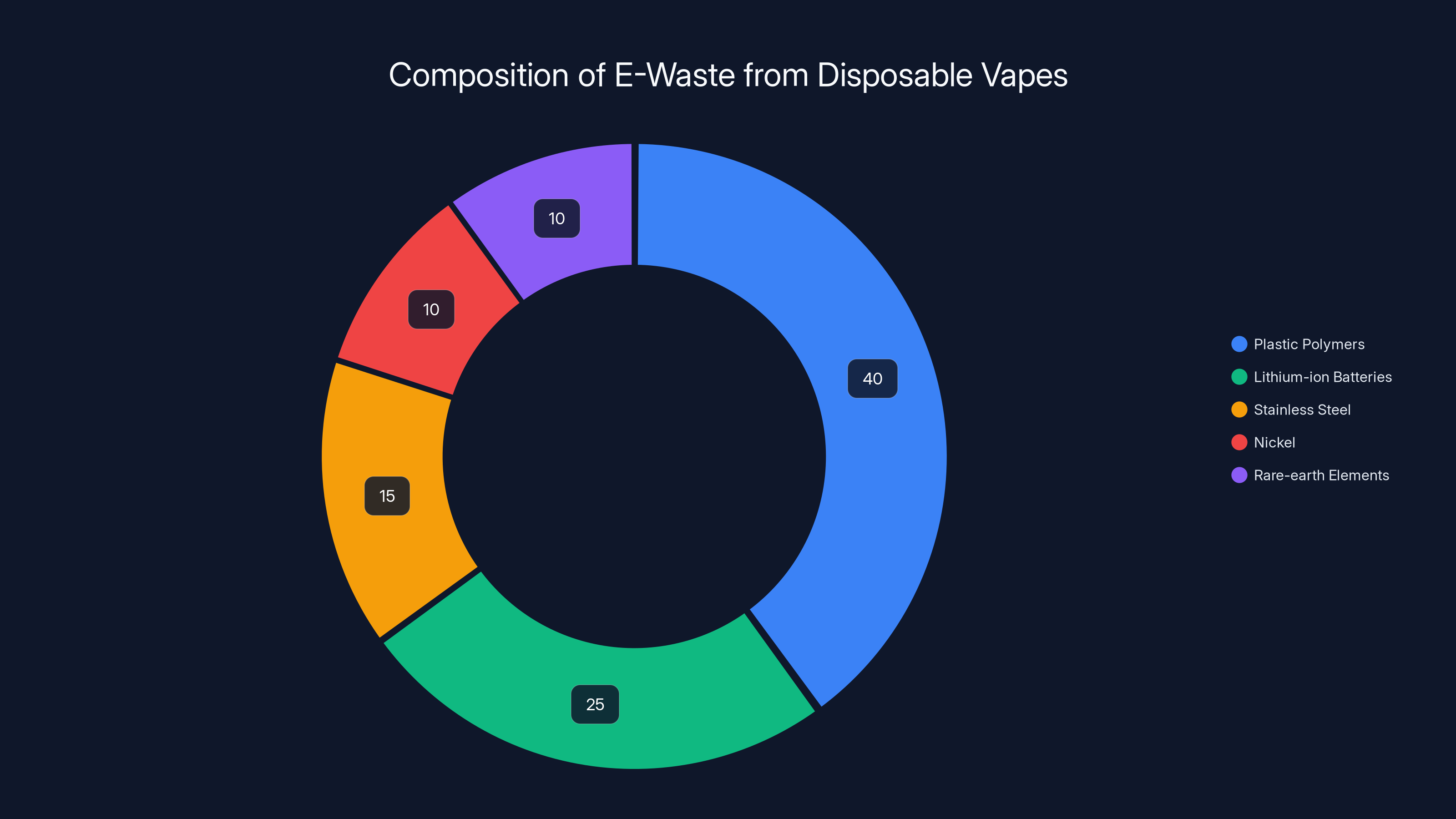

From an e-waste perspective, this is a disaster. Each device contains materials that are either toxic, valuable, or both: lithium-ion batteries, rare-earth elements in some circuits, plastic polymers that take centuries to decompose, stainless steel and nickel in heating elements. When millions of devices end up in landfills or trash incinerators, you've got a significant environmental problem.

Lithium-ion batteries pose a particular hazard. In normal use, they're safe. But when crushed, shorted, or exposed to high temperatures, they can ignite. In landfills and waste processing facilities, heavy machinery inevitably crushes devices, and the resulting battery failures can cause fires. Waste facilities have reported unexplained fires that investigators later traced to lithium-ion battery failures from vape devices in the trash. In incinerators, the heat can also trigger battery failures. These fires are difficult to extinguish and produce toxic smoke.

Then there's the nicotine itself. Residual nicotine in spent vape devices can leach into soil and water. Nicotine is toxic to many aquatic organisms and can accumulate in ecosystems. The plastic case typically breaks down into microplastics, which are now recognized as a pervasive environmental contaminant affecting everything from soil microbes to fish to birds.

The core issue that Paper Bag Team is highlighting is that this entire waste stream exists because of deliberate product design choices by manufacturers. Vape devices could theoretically be designed to be refillable, repairable, or recyclable. Some devices (like traditional Juul pods) are technically refillable, though it's against the terms of service. But the disposable models are designed specifically to be thrown away.

This is where the right-to-repair angle becomes political. Why are these devices designed to be disposable? Because it maximizes manufacturer revenue. You make a device that lasts a week, and you've got a customer returning every week to buy another one. You make a device that lasts a year and is repairable, and you've got a customer returning once a year. The business model depends on disposability.

The Vape Synth doesn't solve this problem. Paper Bag Team is very explicit about this. Making a few thousand vape synths doesn't address the millions of devices in landfills. But the project does two important things: it demonstrates that these devices aren't waste, that they have latent potential, and it draws attention to the issue in a way that's memorable and engaging.

Disposable vapes contribute significantly to e-waste, with plastics and lithium-ion batteries making up the largest share. Estimated data highlights the environmental impact.

Workshops, Conferences, and Community Building

What's remarkable about the Vape Synth is that it didn't remain a one-off academic art project. Instead, Paper Bag Team actively worked to scale the idea through workshops, public demonstrations, and community engagement.

The 2025 Low Tech Electronics Faire was one major venue. This event, which happens annually in different cities, celebrates deliberately low-tech, low-power, and accessible electronics projects. It's the opposite of CES or other high-tech expos. It features e-ink displays, hand-crank generators, analog computers, and other projects that are explicitly anti-hype. The Vape Synth workshop at the faire had dozens of attendees who assembled their own instruments, learned basic soldering, and engaged with the underlying concepts about waste and creativity.

NYC Resistor, the hackerspace where another workshop was held, has been a node in the global maker/hacker network since its founding in 2007. It hosts weekly meetups, maintains thousands of dollars worth of tools, and has trained hundreds of people in electronics, woodworking, 3D design, and other maker skills. Having the Vape Synth workshop at this venue ensured that it reached an audience primed to understand the cultural and technical significance of the project.

The decision to publish on Instructables was strategic. Instructables is one of the most-visited DIY websites globally, with millions of registered users and projects spanning from cooking to electronics to fashion. By publishing the Vape Synth guide there, Paper Bag Team ensured that anyone with a Google search could find complete instructions. No gatekeeping, no paywalls, no registration requirements beyond what Instructables requires.

Rios emphasizes the importance of removing barriers to participation. He notes that many people never even consider tinkering with electronics because they've been taught that it's dangerous, complicated, or reserved for "technical people." By showing that opening a vape, understanding its components, and rewiring it is achievable, the project helps people develop confidence in their ability to engage with technology more broadly.

This is actually a significant goal of broader maker culture. Researchers have studied "maker confidence"—the sense that an individual is capable of building and modifying technology. People with high maker confidence are more likely to attempt repairs, to DIY projects, to question planned obsolescence, and to think critically about technology. They're also more likely to be interested in STEM education and careers. By running these workshops, Paper Bag Team isn't just making a few vape synths—they're increasing maker confidence in their participants.

The workshops also build community in a concrete way. Making something together creates bonds. The people at a Vape Synth workshop interact with each other, help troubleshoot each other's projects, and leave with a sense of accomplishment. Some of them will go on to explore more electronics projects. Some might join the local hackerspace. The ripple effects are impossible to quantify but clearly significant.

Musical Interfaces and Experimental Instruments

The Vape Synth sits within a longer history of experimental and unconventional musical instruments. This is particularly relevant because David Rios teaches about new musical interfaces, and his expertise directly influenced how the project developed.

Experimental music has a rich tradition of using found objects and unconventional instruments. John Cage famously prepared pianos by placing objects on the strings, creating a completely new sound palette. Yoko Ono designed instruction-based pieces where the audience created the music. Harry Partch built instruments from trash and scrap metal. More recently, artists like Heather Kelley have created instruments from air pollution, from beams of light, from human bodies. The Vape Synth fits into this tradition of pushing what "instruments" can be and what kind of sounds are worth making.

From a pure interface design perspective, the Vape Synth is interesting because it repurposes an existing interface (the inhale-based activation of a vape) for a new purpose. This is actually a sophisticated design move. Instead of creating a completely new interface (like a keypad or a touch screen), the designers kept the existing affordance—the breath-activated mouthpiece—and mapped it to a different function. This makes the instrument intuitive to use in one sense (you already know how to suck on a vape) while simultaneously disorienting in another sense (you're getting sound instead of nicotine, which violates expectation).

The button array adds another layer of interaction. Typical synthesizers might have knobs, sliders, or keys. The Vape Synth has buttons because that's what fits in the constrained form factor. The buttons are typically small and somewhat fiddly to press, which again creates a particular aesthetic—playing it is slightly awkward and requires concentration in a way that traditional instruments might not.

This gets at something important in experimental music circles: constraint breeds creativity. If you give someone unlimited resources and perfect tools, they might create something technically proficient but artistically uninteresting. If you give someone a trash vape, some salvaged components, and the challenge of fitting everything into a tiny space, you might get something genuinely novel and conceptually rich.

Rios mentions that a future version will be able to function as a MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) controller. MIDI is a protocol that allows electronic instruments to communicate with each other and with computers. If a Vape Synth can output MIDI, then it could control professional synthesizers, music production software, or even orchestra instruments. This opens up the possibility of the Vape Synth being used in actual musical compositions, not just as a conceptual art piece.

Some experimental musicians have already begun incorporating vape-based instruments into performances. The novelty factor is part of the appeal, but so is the genuine sonic character. The harsh, glitchy sounds of a Vape Synth can be layered into experimental electronic music in ways that sound intentional rather than accidental. There's also a conceptual richness—performing with an instrument made from waste material, inherently making a statement about consumption and throwaway culture.

Estimated data shows North America and Europe as leading regions in the global distribution of makerspaces, reflecting the strong maker culture presence in these areas.

The Second Generation: What's Coming Next

Paper Bag Team isn't resting on the success of the original Vape Synth. They're actively developing a second generation that addresses some of the limitations of the first version while maintaining the conceptual integrity of the project.

The main improvements they're planning include:

Enhanced sound synthesis: The first-generation Vape Synth produces relatively simple square and triangle waves. The second generation will include more sophisticated oscillator circuits, possibly sawtooth waves, PWM (pulse-width modulation) capabilities, and maybe even simple subtractive synthesis with filter modules. The sound won't be "good," necessarily, but it will have more tonal variety and more expressive potential.

Wider pitch range: The original version is somewhat limited in frequency range, making it difficult to play melodies across a wide span. The second generation will have octave switching and maybe even a wider frequency range per octave.

MIDI output: This is huge. If the Vape Synth can output MIDI data, then it becomes not just an instrument in itself but a controller for other instruments and software. You could use it to trigger samples in a DAW, control synthesizers, or create complex arrangements by layering its MIDI output with other instruments.

Effects processing: Reverb, delay, distortion, and other effects could make the sound more interesting and less purely abrasive. Though there's a question about whether adding effects compromises the conceptual purity of the project.

Improved ergonomics: The buttons on the first generation are small and sometimes difficult to use. The second version will optimize button placement and size for more comfortable playing.

Battery life improvements: The original mostly uses the vape's existing battery. A second generation could include additional power management and maybe even a small USB power option so it can be played indefinitely rather than until the battery depletes.

Love, Rios, and Cai are also considering scalability. Could there be a kit version? Could they work with makerspaces to distribute plans and components? Could educational institutions integrate Vape Synth-building into curricula around electronics, sustainability, or creative technology?

There's also the question of how the project scales internationally. The instructions currently assume access to Elf Bar devices (which are extremely common in the US and many other countries), but different regions have different popular vape brands. Could the hack be adapted for other devices? Could Paper Bag Team publish region-specific guides?

Longer-term, there's potential for the Vape Synth to become a platform for musical creativity. Just as modular synthesizers allow musicians to patch together different modules to create unique sounds, perhaps the Vape Synth platform could evolve to allow different circuit boards, different sensor configurations, different output options. The form factor—the vape cartridge itself—could become a standardized housing for different kinds of experimental instruments.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

There are some interesting legal questions hovering around the Vape Synth project, though they haven't been a major focus of the team's work.

First, there's the question of intellectual property around the vape device itself. When you take apart an Elf Bar and modify it, are you violating any patents or design rights held by the manufacturer? Technically, maybe. In practice, the manufacturers of disposable vapes have much bigger problems than people turning their devices into musical instruments. They're dealing with regulatory pressure from the FDA, lawsuits from public health organizations, and enormous amounts of counterfeit products in the market. A few people hacking vapes into synths registers as essentially zero priority.

Second, there's the question of the original nicotine product. The instructions explicitly warn people to wear gloves because nicotine can be absorbed through skin. This is accurate—nicotine is toxic and has been used as pesticide. But by creating an instrument that looks and functions like a vape (you literally suck on the mouthpiece), could the Vape Synth be mistaken for an actual nicotine device? This seems like a non-issue in practice, especially since the devices are clearly labeled and demonstrated, but it's theoretically in a gray area.

More broadly, there are regulatory questions about e-waste and DIY modification. In some jurisdictions, opening up electronic devices and modifying them might technically violate warranty terms or terms of service. However, the right-to-repair movement has been pushing back against these restrictions, arguing that users should have the legal right to modify their own devices. No court has actually taken issue with the Vape Synth project, and it's unlikely anyone would given the relatively trivial scale.

The FDA's oversight of vape devices is also relevant here. The FDA has regulatory authority over vapes as tobacco products, but they focus on the nicotine-containing aspect, marketing claims, and sale to minors. Hacking a vape into a musical instrument and removing the nicotine probably falls completely outside their jurisdiction.

The Vape Synth team hasn't spent much energy on legal considerations, partly because the project is so conceptually clear and benign. They're not trying to create competition for commercial synthesizers. They're not trying to sell anything. They're not encouraging the manufacture or distribution of vape devices—quite the opposite. They're turning waste into art. This is generally seen favorably by legal and ethical frameworks.

If anything, the Vape Synth might have positive legal implications. If regulators ever crack down on disposable vapes (which some jurisdictions are considering), they might view hacking projects like this as evidence that people care about and can repurpose these devices, reducing the pure waste problem. It's a small thing, but potentially useful in the policy space.

The Intersection of Art, Activism, and Community

What makes the Vape Synth project genuinely significant is how it bridges art, activism, and community building without being heavy-handed about any of those dimensions.

As art, it's interesting. The aesthetic is deliberately strange—an instrument that looks like a vape, sounds like a malfunctioning synthesizer, and plays through the repeated gesture of sucking on a mouthpiece. There's something conceptually rich about that. It comments on consumption, waste, technology, music, and bodily gesture all at once. Artists are already integrating it into performances and installations.

As activism, it's effective because it's not preachy. It doesn't lecture about e-waste or sustainability. Instead, it demonstrates—through play and creativity—that these devices have value beyond their original purpose. It shows that waste materials can be repurposed creatively. And it implicitly critiques the throwaway culture that designed these devices to be discarded after brief use.

As community building, it's powerful. Every workshop creates a new network of people who know each other, who've made something together, who understand electronics a little better, who feel more confident tinkering with technology. Those people become vectors for spreading maker culture and sustainability consciousness to their friends, families, schools, and workplaces.

The "Bubble Punk" philosophy that inspired the project—making serious issues funny and approachable—has proven effective. Environmental activism can feel overwhelming. Sustainability can feel guilt-inducing. But making a weird musical instrument? That feels fun. And that's actually more likely to change people's behavior than guilt or despair.

This is something organizational psychologists and social scientists have noted repeatedly: movements that combine play and seriousness, humor and integrity, are more successful at creating lasting cultural change. The Vape Synth exemplifies this. It's serious about waste. It's serious about right-to-repair. It's serious about creative agency and maker culture. But it's also genuinely funny and delightful.

Educational Value and STEM Engagement

One of the most underrated aspects of the Vape Synth project is its educational potential. Paper Bag Team and their collaborators recognize that the project can teach multiple valuable skills and concepts, from electronics to music to environmental science to critical thinking about technology.

From an electronics education perspective, building a Vape Synth requires understanding:

Circuit design: How oscillators work, how amplifiers function, how sensors interface with microcontrollers, how power distribution works in a circuit. These are fundamental concepts in electrical engineering that students typically learn through textbooks and breadboard experiments. Learning them through the context of building an actual, functional device is far more effective than abstract study.

Soldering and assembly: Physical skills that are valuable in any electronics work. Proper soldering technique prevents cold joints and component failure. Understanding electrical safety (knowing not to solder near flammable materials, understanding voltage and current hazards) is essential knowledge.

Programming: The Vape Synth requires uploading firmware to a microcontroller. This introduces participants to the Arduino platform, to basic programming concepts, to debugging. These skills transfer to broader computer science education.

Problem-solving: When something doesn't work—a button doesn't register, a frequency is wrong, the speaker produces no sound—participants have to troubleshoot. This develops critical thinking and systematic debugging skills.

From a music and audio perspective:

How sound synthesis works: Instead of learning about oscillators and waveforms in a music production course, you're building the physical circuit that generates the waveforms. The understanding is embodied rather than abstract.

Interface design: Why do certain controls affect certain parameters? How does the physical affordance of the device relate to how it's played? These are questions that come up naturally when building an instrument.

Sonic creativity: Using limited tools to create interesting sounds. This is a constraint-based design challenge that mirrors real creative work.

From an environmental and critical thinking perspective:

E-waste awareness: Actually handling and learning the components of a disposable device makes the waste problem concrete rather than abstract.

Right-to-repair: By hacking a device, you learn that manufacturers intentionally hide designs and make products hard to repair. This raises critical questions about corporate practices and planned obsolescence.

Creative resistance: The project models how to engage with serious problems through creativity rather than just passive concern. It's a form of cultural activism through making.

Educators at various levels have begun integrating Vape Synth projects into curricula. High school electronics clubs use it as a capstone project. Art schools use it in classes about artists who use found materials. Environmental science courses use it as a case study in waste reduction and creative reuse.

Scaling the Movement: Can This Approach Work for Other E-Waste?

One question that naturally emerges from the success of the Vape Synth is whether this approach can scale to other e-waste products. Could you hack dead smartwatches into something? Could dead smartphones be turned into art pieces or functional devices? Could the "Bubble Punk" philosophy apply to other waste streams?

The Vape Synth is particularly well-suited to hacking because of specific design features: it has a built-in battery, a usable form factor, a sensor that can be repurposed, and it's simple enough internally that modifications are feasible with basic tools. Not all e-waste has these properties.

Smartphones, for example, are incredibly dense with complex components, tightly integrated to the point where removing one component often breaks others. They'd be harder to hack without destroying them. Smartwatches might be more feasible, but the economics are different—people might be incentivized to repair them rather than hack them, since they're expensive and still useful in their original form.

But there are other waste products that might work well. Dead vape devices are universal—so are dead USB charging cables, broken headphones, defunct e-readers, failed fitness trackers. Each could potentially be hacked into something interesting. A broken phone screen could become a light diffuser for an art installation. A defunct e-reader could be the basis for a digital art display. The scaffolding for these projects would be different, but the philosophy would remain the same.

What the Vape Synth demonstrates is that creative, playful hacking projects can draw attention to e-waste while simultaneously democratizing electronics skills and building community. Scaling this to other products wouldn't necessarily mean replicating the Vape Synth format. It would mean adopting the underlying principles: find waste products with interesting affordances, design hacks that are achievable for non-experts, make the project fun and slightly absurd rather than earnest and guilt-inducing, publish instructions freely, and run community workshops to spread knowledge and skills.

Some cities and organizations are beginning to do this. The Los Angeles-based electronics recycling nonprofit is considering hack-and-hacks projects (workshops where people hack discarded electronics). Makerspaces worldwide are developing projects around repurposing local e-waste streams. The Vape Synth isn't the end of this movement—it's an early exemplar showing what becomes possible when art, activism, engineering, and community converge.

The Future of DIY Hacking and Sustainability

The Vape Synth exists at an inflection point in how society relates to technology and waste. Several trends suggest that this kind of project will become increasingly important and increasingly visible.

First, e-waste is becoming impossible to ignore. Projections suggest that global electronic waste will reach 75 million tons annually by 2030. This is already exceeding annual plastic waste in some measures. Regulations are tightening—the EU's Right to Repair directive is pushing manufacturers toward modularity. Consumers are increasingly aware of planned obsolescence and actively seeking repair alternatives.

Second, maker culture and DIY electronics have become democratized. Platforms like Arduino, Raspberry Pi, and Adafruit have made microcontrollers accessible and cheap. Online tutorials and communities make learning electronics possible for anyone with an internet connection. Hackerspaces and makerspaces exist in most major cities. The barrier to entry has collapsed.

Third, there's growing cultural interest in questioning consumerism and corporate control over technology. The right-to-repair movement has become politically mainstream. Sustainability isn't just an environmentalist niche—it's becoming expected of corporations. Cultural criticism of planned obsolescence and throwaway culture is increasing.

The Vape Synth is positioned perfectly at the convergence of these trends. It's a project that would have been almost impossible fifteen years ago (no accessible microcontrollers, no global maker community, less awareness of e-waste) and will likely be far more common in the next decade.

FAQ

What exactly is a Vape Synth?

A Vape Synth is a functional musical synthesizer created by modifying a dead disposable vape cartridge, typically an Elf Bar. The hack repurposes the vape's existing battery and pressure sensor while adding a microcontroller, oscillator circuits, buttons, and a small speaker. When you suck on the mouthpiece, you activate the pressure sensor which triggers audio tone generation. Different buttons select different pitch ranges or sound parameters.

How does the pressure sensor work in the hack?

Vape devices include a pressure sensor that normally detects when you're inhaling and activates the heating element. The Vape Synth hack repurposes this same sensor but instead of triggering a heating coil, it triggers an oscillator circuit that generates audio frequencies. By varying how hard you suck, you can subtly adjust pitch, giving you expressive control similar to playing a wind instrument.

How much does it cost to build a Vape Synth?

If you already have a soldering iron and basic tools, the material cost is roughly $15-30 in components (microcontroller, speaker, buttons, wire, solder). You need to source a used Elf Bar vape cartridge (which you can find discarded almost anywhere or purchase cheaply secondhand). The main costs are your time (2-4 hours for experienced builders, 5-8 hours for beginners) and potentially workshop fees if you're building at a hackerspace or makerspace rather than at home.

Is it legal to hack a disposable vape?

Yes, in the United States and most countries, hacking a vape device that you own is legal. Since you're removing it from its original use entirely (extracting it from nicotine delivery and converting it to an instrument), you're not violating FDA regulations or trademark laws. Right-to-repair principles support your legal right to modify devices you own. The key is that you're not manufacturing or distributing vapes—you're hacking waste into art.

What does a Vape Synth actually sound like?

Intentionally terrible. The sounds are harsh, piercing, and chaotic—often described as resembling a dying rabbit, a swarm of insects hitting an electric fence, or the internal screaming of a synthesizer. This is deliberate. The poor sound quality is part of the artistic concept rather than a bug. The second-generation version in development will have better tonal range and sound quality while maintaining the intentionally experimental aesthetic.

Can I turn a Vape Synth into a MIDI controller?

Yes, and the second-generation version being developed will have built-in MIDI output. With MIDI capability, a Vape Synth can control professional synthesizers, music production software, or other instruments. This would significantly expand the musical possibilities while maintaining the conceptual integrity of the project—you're still playing an instrument made from repurposed waste, but now it can integrate into serious musical work rather than existing as pure conceptual art.

Where can I find instructions to build my own?

Paper Bag Team has published comprehensive step-by-step instructions on Instructables, the world's largest DIY platform. Search for "Vape Synth" and you'll find the full guide with circuit diagrams, component lists, firmware code, and detailed assembly instructions. The instructions are free and open-source. Additionally, workshops are periodically held at makerspaces and conferences like the Low Tech Electronics Faire.

How does this relate to right-to-repair and e-waste activism?

The Vape Synth is explicitly designed to be an activist project that draws attention to the e-waste crisis caused by disposable vapes while simultaneously demonstrating that these devices have latent value rather than being pure garbage. By showing that waste materials can be creatively repurposed, the project challenges the throwaway culture of consumer electronics. It also exemplifies right-to-repair principles by showing that consumers can modify and improve devices rather than passively accepting them as sealed black boxes from manufacturers.

What makes the Vape Synth different from other musical hacks or circuit-bending projects?

The Vape Synth combines several elements: it repurposes a ubiquitous waste product, it embraces deliberately poor-quality sound as part of its artistic statement, it emphasizes accessibility through free public instructions and community workshops, and it frames the hack as an activist statement about e-waste and planned obsolescence. While circuit-bending (the practice of modifying consumer electronics to create new sounds) has a long history, the Vape Synth explicitly centers on waste, sustainability, and community education in ways most other projects don't.

Who created the Vape Synth project?

The Vape Synth was created by Paper Bag Team, a collective of three makers and academics: Kari Love (professor at NYU's Interactive Telecommunications Program), David Rios (also at ITP, specializing in new musical interfaces), and Shuang Cai (Ph.D. student at Cornell University who teaches at both Cornell and NYU). All three are self-described salvage hoarders and makers who work at the intersection of art, technology, education, and environmental activism.

Conclusion: The Vape Synth as Cultural Statement

The Vape Synth is deceptively simple on the surface. It's a joke, a performance piece, a musical hack. But dig deeper and you find something more significant: a coherent statement about how we relate to technology, waste, creativity, and community in the early twenty-first century.

On the most basic level, it works as intended. A dead vape becomes a playable musical instrument. The hack demonstrates that waste materials contain latent value. But the project's real significance extends far beyond that single achievement.

The Vape Synth challenges the assumption that technology must be treated as sealed black boxes that consumers passively use and passively discard. By opening up a device, understanding its components, and repurposing those components for a new creative purpose, the project demonstrates that consumers have agency. You're not powerless in the face of planned obsolescence. You have the tools and knowledge to act.

The deliberate embrace of silliness and poor audio quality is also philosophically important. Environmental activism can feel overwhelming, guilt-inducing, and joyless. The Vape Synth proves that you can care deeply about waste and sustainability while also laughing, playing, and having fun. In fact, play might be more effective at creating cultural change than earnestness. People are more likely to engage with ideas and communities when there's joy involved.

The decision to publish freely, run public workshops, and position the project as open-source and accessible is equally significant. This isn't gatekept knowledge or proprietary IP. It's freely available to anyone with basic electronics skills and access to tools. Every person who builds a Vape Synth gains skills, confidence, and connection to community. They become more likely to repair other devices, to question planned obsolescence, to engage creatively with technology.

The Vape Synth also sits within larger conversations about regulation, corporate responsibility, and consumer rights. As disposable vapes flood landfills and governments begin considering bans or new regulations, projects like this demonstrate that these devices aren't purely waste. People care enough to hack them, repurpose them, and build artistic and musical projects from them. This could theoretically influence policy conversations, though the project's creators are modest about any such aspirations.

Looking forward, the Vape Synth suggests a direction for maker culture, environmental activism, and art practice. It's not about developing perfect solutions or perfectly efficient systems. It's about combining technical creativity with social consciousness, about making activism joyful and accessible, about building community around shared values. If similar projects emerge for other waste streams—hacked smartwatches, repurposed headphones, artistic installations from dead electronics—it would represent a genuine cultural shift in how we treat technology and waste.

The immediate future likely includes a second-generation Vape Synth with improved sound quality and MIDI capabilities. The medium-term future probably includes these instruments appearing in experimental music performances, in maker fairs globally, and in educational curricula around electronics and sustainability. The longer-term future is harder to predict, but clearly the project has struck something culturally resonant. People are interested in it. They want to build them. They want to perform with them. They want to engage with the ideas it represents.

In the end, the Vape Synth is a hack, a performance, an art project, an educational tool, and a statement about technology and waste all at once. It proves that what we call garbage often contains unrealized potential. It demonstrates that ordinary people can understand and modify technology if given access to knowledge and tools. And it shows that making the world better doesn't require grim sacrifice or guilt—it can be fun, creative, and joyful. That might be the most important message of all.

Try Runable For Free

If you're interested in experimenting with creative projects, automation, and turning ideas into reality quickly, Runable helps you build and prototype concepts with AI-powered automation. Whether you're documenting your DIY projects, creating presentations about maker culture, or generating reports on your hacking experiments, Runable's AI agents can accelerate your workflow. Start at just $9/month and explore how automation can enhance your creative practice.

Key Takeaways

- The Vape Synth project transforms dead disposable vape cartridges into functional musical instruments by repurposing the existing battery, pressure sensor, and form factor

- Created by Paper Bag Team (Kari Love, David Rios, and Shuang Cai), the project uses 'Bubble Punk' philosophy to make serious environmental activism fun and accessible rather than preachy

- Comprehensive free instructions published on Instructables enable anyone with basic soldering skills to build their own Vape Synth for $15-30 in components

- The project exemplifies the right-to-repair movement and maker culture, challenging planned obsolescence by proving waste materials have creative potential

- With workshops globally and growing adoption by experimental musicians, the Vape Synth demonstrates how combining art, activism, and community can create meaningful cultural change

Related Articles

- Mandy, Indiana URGH Album Review: Why This Record Matters [2025]

- Redwood Materials $425M Series E: Google's Bet on AI Energy Storage [2025]

- Obvious Ventures Fund Five: The $360M Bet on Planetary Impact [2026]

- Why Bad Laptops Actually Improve Your Life: The Case for Trash Hardware [2025]

- Korg Phase8: The Hybrid Synthesizer Redefining Acoustic Sound [2025]

- Right-to-Repair Battle: How the Repair Act Could Change Car Ownership [2025]

![Vape Synth: How Hackers Turn E-Waste Into Music [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/vape-synth-how-hackers-turn-e-waste-into-music-2025/image-1-1770723462984.png)