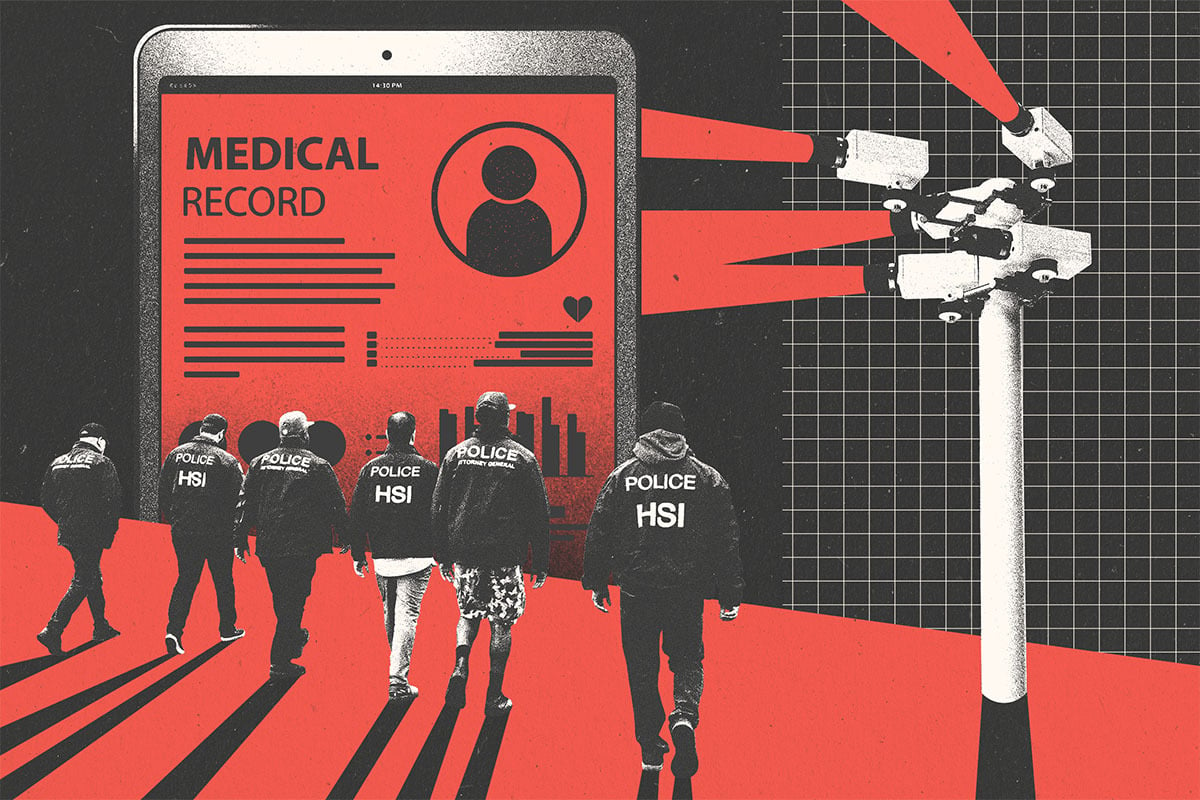

How Google Handed Over a Student Journalist's Personal Data to ICE: The Full Story [2025]

Let me start with something that should make you uncomfortable. A tech company you probably use every day just handed over your personal information—your address, your financial data, your phone number—to a government agency. Without a judge's approval. Without telling you it happened. And the person it happened to wasn't even a criminal suspect. She was a student. A journalist. Someone who attended a protest.

This isn't hypothetical. This is what happened to Amandla Thomas-Johnson, a British student and journalist at Cornell University, when she attended a pro-Palestinian protest in 2024.

Google didn't hesitate. The tech giant complied with an administrative subpoena issued by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and turned over everything: her usernames, physical address, phone numbers, subscriber information, IP addresses, and—this is the part that really matters—her credit card and bank account numbers.

The subpoena came with a gag order. Meaning Google legally couldn't tell her what happened. She found out when ICE showed up.

Here's what you need to understand about this case: it's not an isolated incident. It's a pattern. And it reveals something deeply broken about how tech companies handle government requests, how little protection administrative subpoenas actually require, and what it means when surveillance tools get turned toward people who simply exercise their right to protest.

This article digs into everything that happened, why it matters, and what it means for your privacy right now.

TL; DR

- Google complied with an ICE subpoena that didn't require judicial approval, handing over extensive personal and financial data about student journalist Amandla Thomas-Johnson, as detailed by The Intercept.

- Administrative subpoenas are uniquely powerful because agencies issue them directly without court oversight, and tech companies aren't legally required to comply, as explained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- The pattern is expanding to target people critical of the Trump administration, including anonymous activists documenting ICE activity, as reported by CBS News.

- Major tech companies are cooperating with ICE requests despite lacking legal obligation to do so, as noted in BBC News.

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation demands change, calling on companies to challenge unlawful demands and notify users before handing over data, as outlined in their open letter.

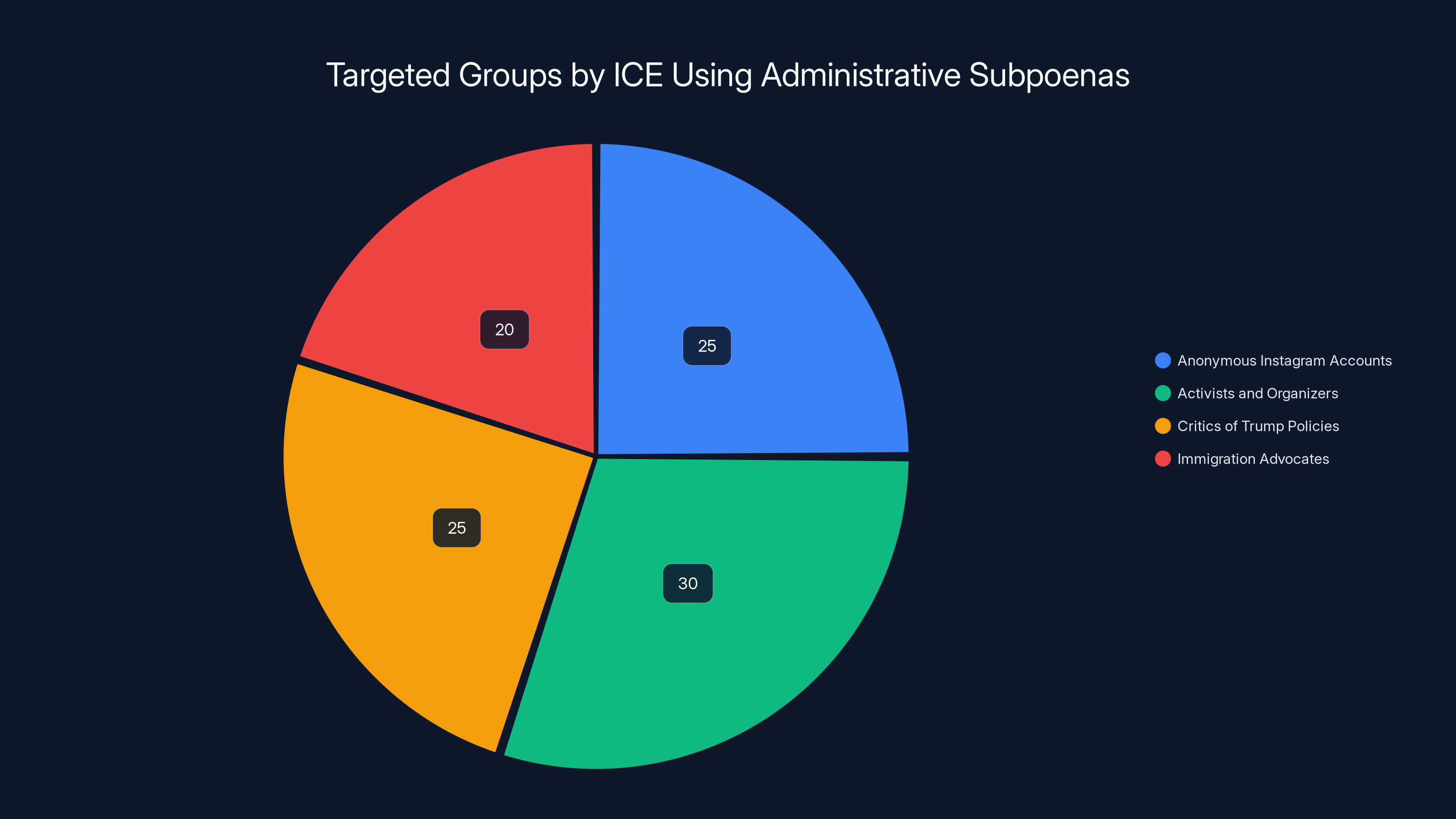

Estimated data shows activists and organizers are the most targeted group by ICE, followed closely by anonymous accounts and critics of Trump policies.

What Exactly Happened to Amandla Thomas-Johnson

Amandla Thomas-Johnson is 23 years old. She's British. She came to the United States on a student visa to attend Cornell University in New York. By most measures, she's exactly the kind of person immigration systems are designed to support: a talented international student pursuing higher education.

In 2024, she attended a pro-Palestinian protest while on campus. It wasn't a lengthy occupation. It wasn't illegal. She was there briefly, exercising her right to free assembly and free speech. Nothing more.

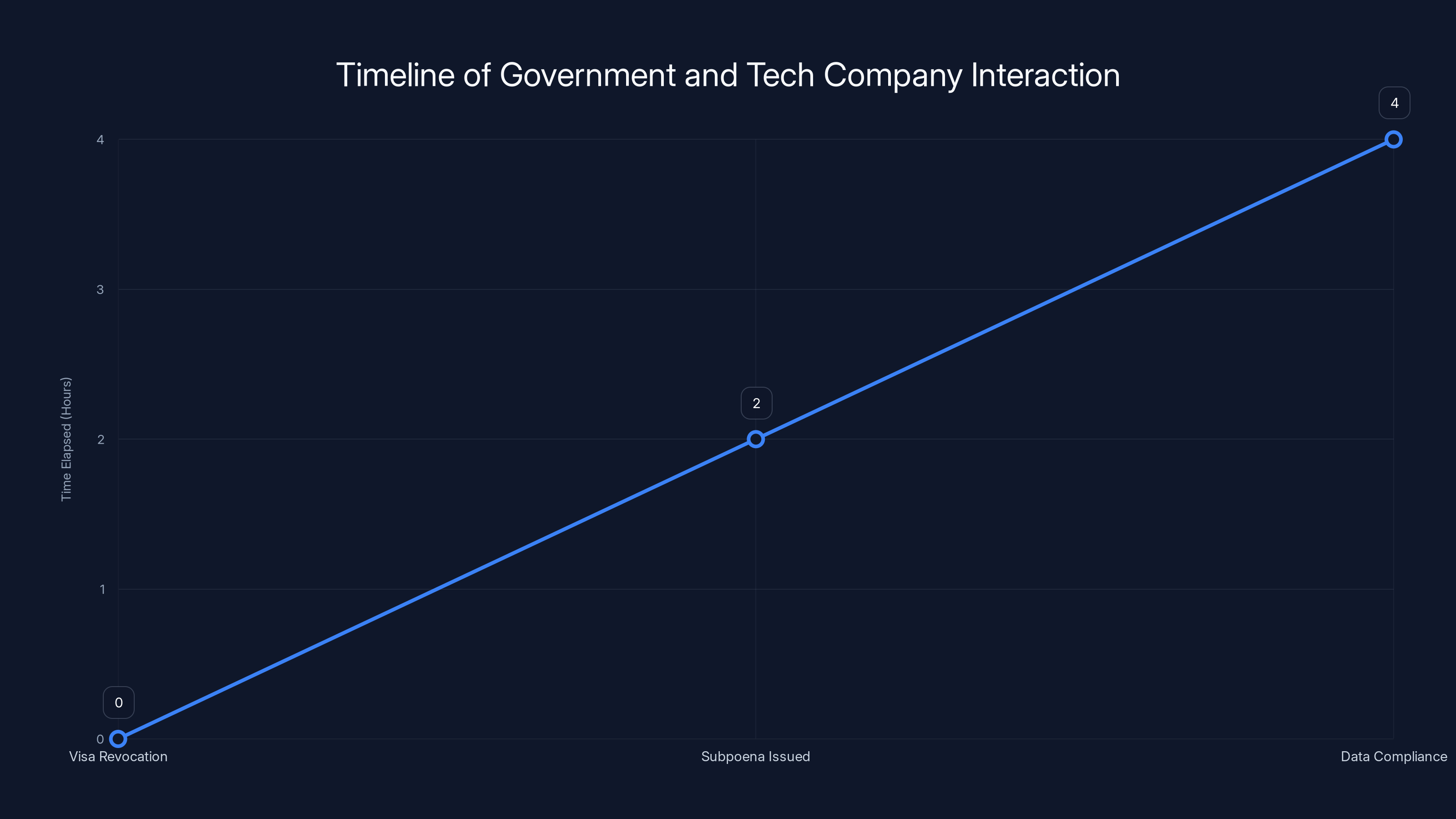

Then, without warning or explanation, Cornell informed her that the U.S. government had revoked her student visa. The revocation came down the way government decisions sometimes do: with official finality but no clear reasoning. Within two hours of that notification, ICE issued an administrative subpoena demanding her data.

Two hours.

Google responded by handing over everything. They didn't challenge it. They didn't notify Thomas-Johnson. They didn't ask for a court order. They just complied. The subpoena included an explicit gag order, which meant Google couldn't legally tell her what was happening.

She learned about the data handover the same way most people learn about things like this: after the fact, through investigative journalism. The Intercept broke the story in early 2025, detailing exactly what Google had turned over and the timeline of events.

What Google provided went far beyond basic identifiers. The company handed over her full Google account history metadata, including every service she'd used. Financial data. Phone numbers. Subscriber information. IP addresses. Multiple identifiers tied to her account. Bank and credit card information.

Technically, administrative subpoenas can't compel companies to hand over email contents, search histories, or precise location data. But metadata? They can demand that. And metadata is deceptively powerful. Metadata paints a picture of someone's life: when they accessed their account, where from, what services they used, financial patterns. It's less granular than content, but it's often more revealing.

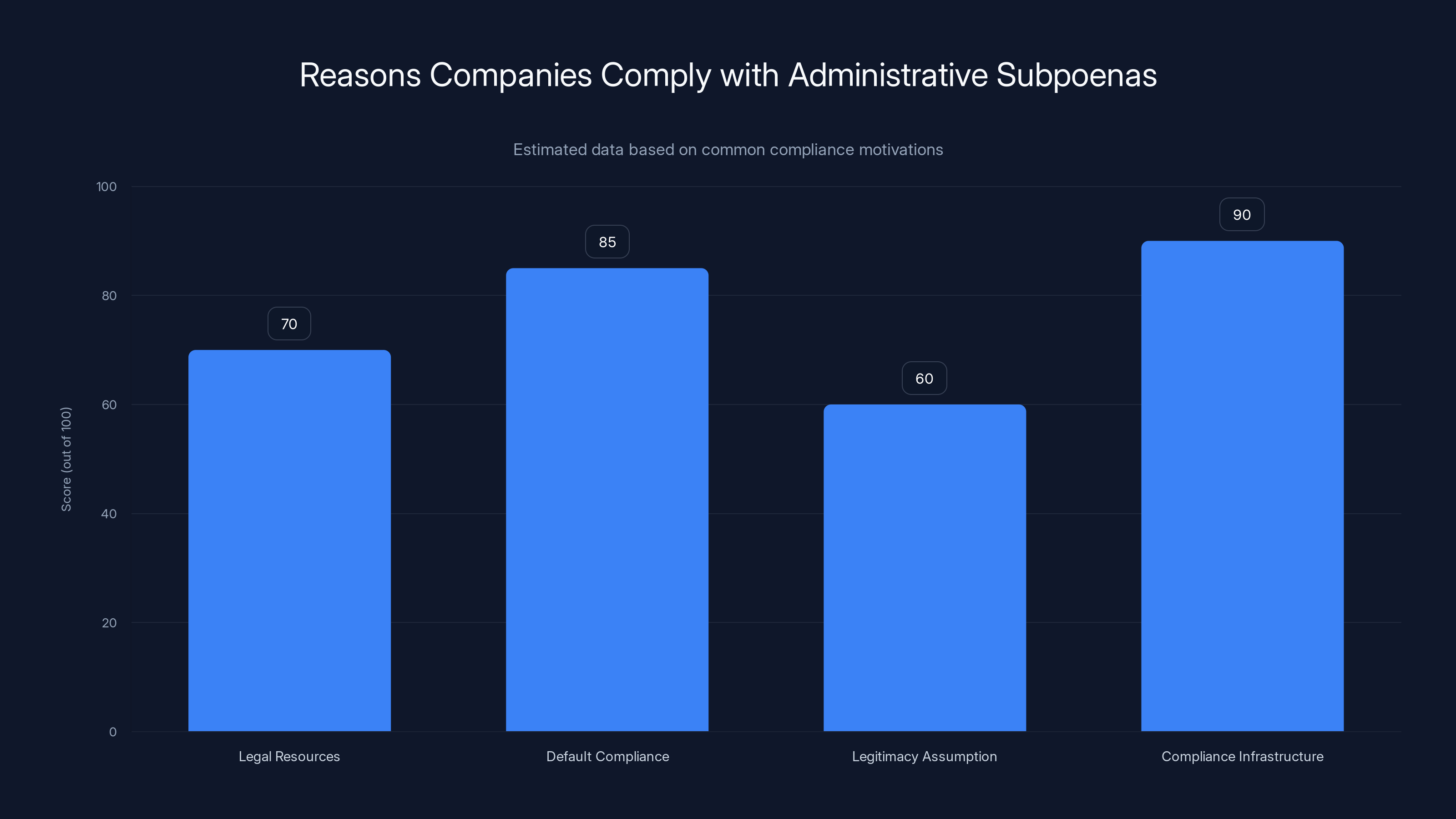

Companies often comply with administrative subpoenas due to existing compliance infrastructure and the default mode of compliance, despite not being legally required. (Estimated data)

Understanding Administrative Subpoenas: The Legal Tool Nobody Talks About

Here's what most people don't understand about administrative subpoenas: they're fundamentally different from typical legal requests in ways that matter enormously.

When law enforcement wants your data in a criminal investigation, they usually need a warrant. A warrant requires showing a judge probable cause that a crime occurred and that the evidence sought relates to that crime. There's oversight. There's a neutral party. There's documented reasoning.

Administrative subpoenas don't work that way.

A federal agency—like ICE, which operates under the Department of Homeland Security—can issue an administrative subpoena directly. No judge required. No judicial review. No requirement to prove probable cause. The agency simply decides it wants information and issues the demand.

This power exists because Congress thought some government agencies needed the ability to move quickly to gather information for administrative purposes. Fair enough in theory. But in practice, it creates a system where government agencies have unilateral authority to demand private data with almost no oversight.

Here's what administrative subpoenas can demand: metadata, identifiers, basic account information. Phone numbers, email addresses, usernames, IP addresses, subscriber information, payment methods. Anything that identifies who someone is and what services they've used.

Here's what they can't demand: the contents of communications, search history, location data (with some nuance), or other content-based information. That requires an actual warrant.

But there's a massive caveat: tech companies aren't legally required to comply with administrative subpoenas at all. Unlike court-ordered warrants, which companies must comply with or face contempt charges, administrative subpoenas are technically voluntary. Companies can refuse. They can challenge them. They can demand that agencies get proper judicial authority.

Google didn't refuse. Google didn't challenge. Google didn't demand a warrant.

Google just complied.

Why did Google comply? The company didn't publicly explain its reasoning. But there are some possibilities. Maybe compliance is easier than fighting. Maybe Google's legal team assessed the risk of non-compliance as higher than the risk of complying. Maybe there's an assumption in Silicon Valley that government requests, even questionable ones, should be treated as legitimate.

Whatever the reason, Google's decision to comply set precedent. It signaled that these requests work. That agencies don't need warrants. That metadata is up for grabs.

The Broader Pattern: ICE Is Targeting Activists, Journalists, and Critics

The Thomas-Johnson case isn't unique. It's the most recent visible example of a much larger pattern.

ICE and other government agencies have been using administrative subpoenas to target people who criticize the Trump administration, document ICE activity, or organize politically. The Washington Post's reporting revealed requests targeting:

- Anonymous Instagram accounts that share information about ICE locations and raid activity

- Activists and organizers involved in various protest movements

- People who criticize Trump policies on social media

- Immigration advocates who document government overreach

This isn't theoretical. It's happening right now. And the pattern suggests a deliberate strategy: use administrative subpoenas to identify and track people who are politically inconvenient to the administration.

What makes this particularly alarming is the scope. If you attended a protest, posted about it on social media, and used a Google product while doing so, you could theoretically be targeted. If you documented an ICE raid on Instagram, you could be de-anonymized. If you criticized government policy publicly, you're potentially in the crosshairs.

The power to surveil is the power to chill. When people know the government can identify them through their online activity, they self-censor. They stop documenting abuses. They stop organizing. They stop exercising rights that are supposed to be protected.

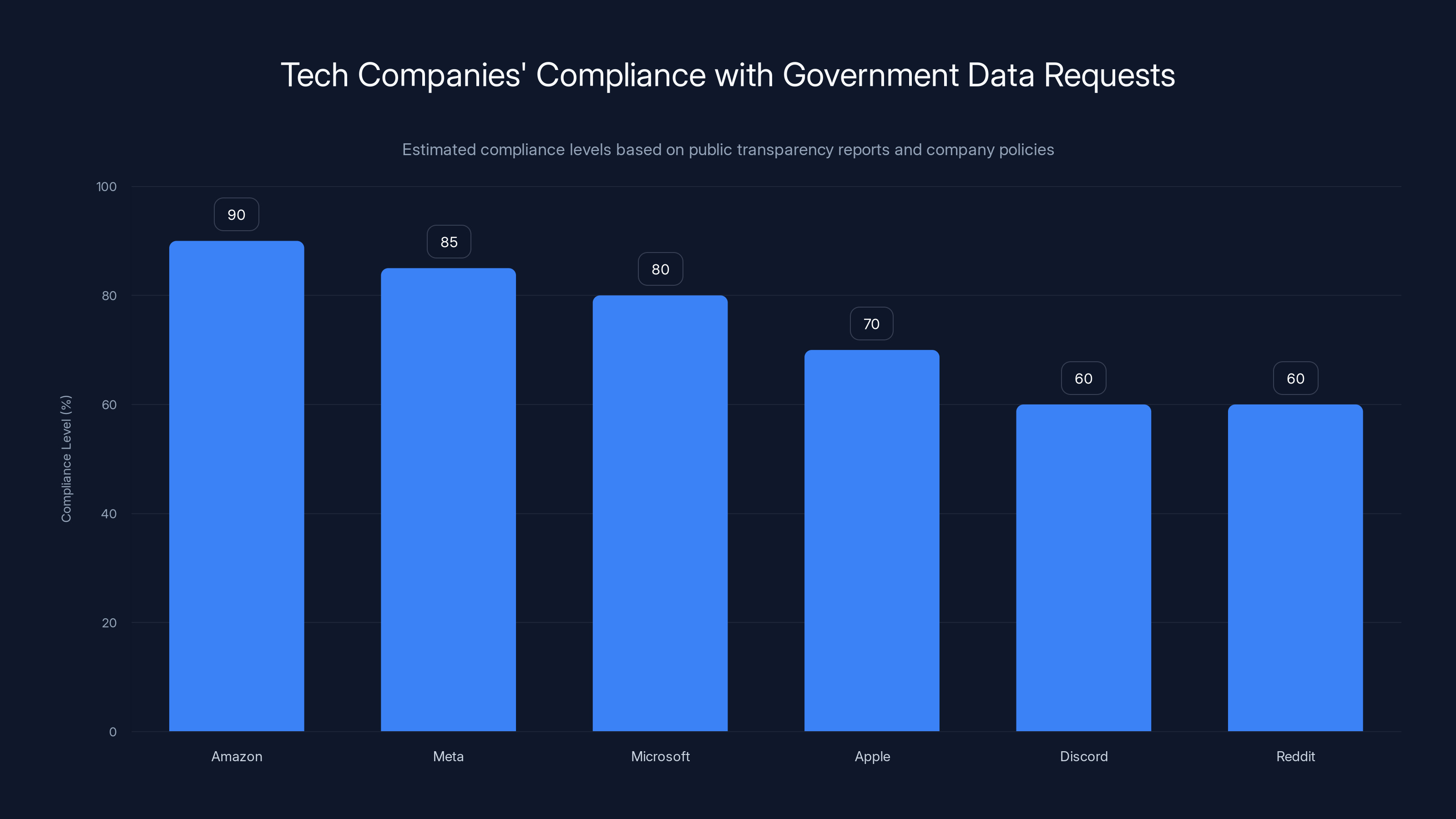

The Electronic Frontier Foundation sent a detailed letter to major tech companies in early 2025 calling this out explicitly. The letter was addressed to Amazon, Apple, Discord, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Reddit. The EFF's core argument: your companies are complying with unlawful surveillance demands.

The letter wasn't polite corporate language. It was direct: "Based on our contact with targeted users, we are deeply concerned your companies are failing to challenge unlawful surveillance and defend user privacy and speech."

The EFF made three specific demands:

- Stop giving data to the Department of Homeland Security in response to administrative subpoenas unless the agency first gets judicial confirmation that the demands aren't unlawful

- Notify users about demands for their information with meaningful time to challenge the requests themselves

- Be transparent about the volume and nature of these requests through transparency reports

These are reasonable demands. They're not asking companies to break the law. They're asking companies to uphold civil liberties by refusing to participate in surveillance that bypasses normal legal processes.

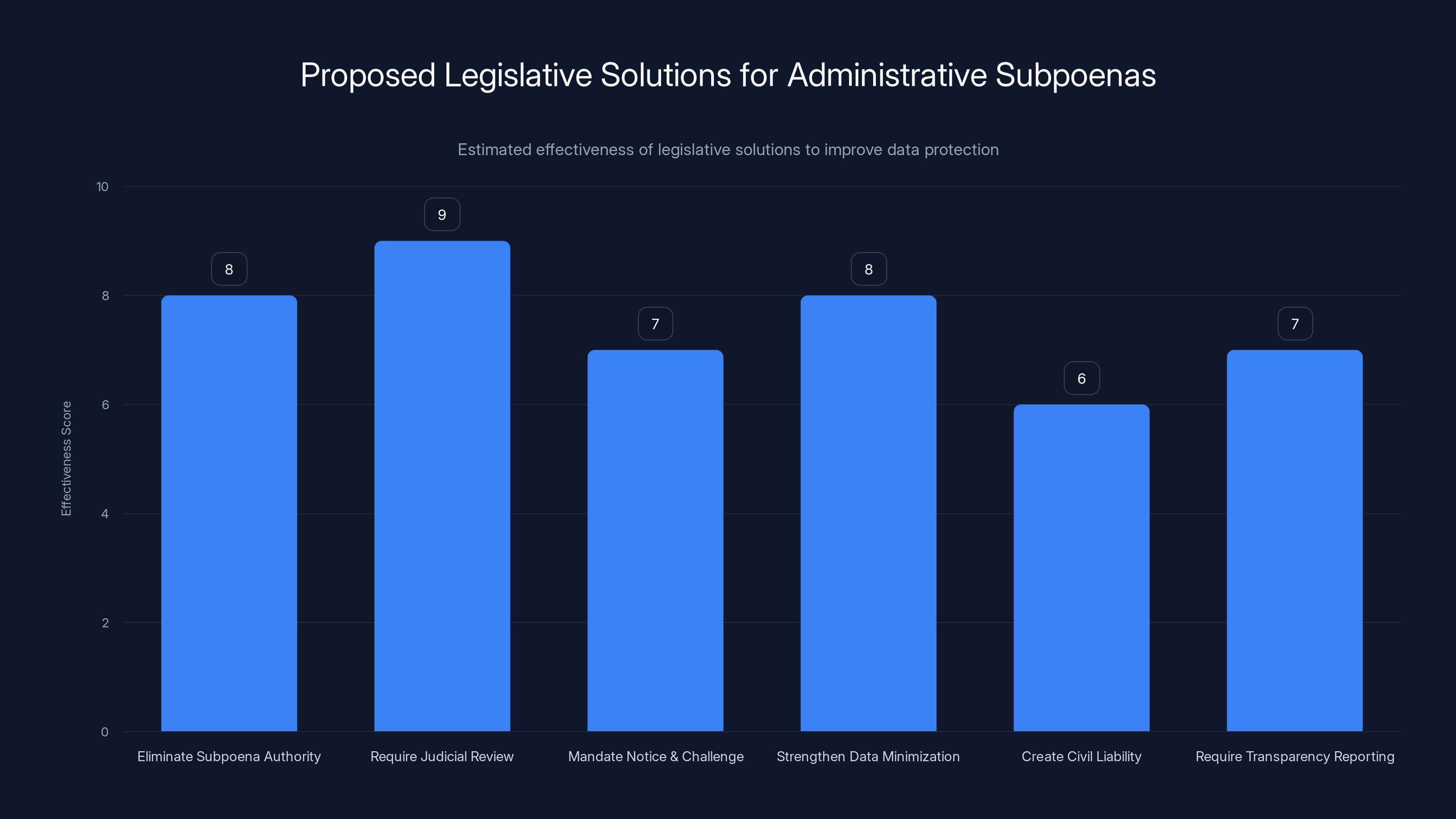

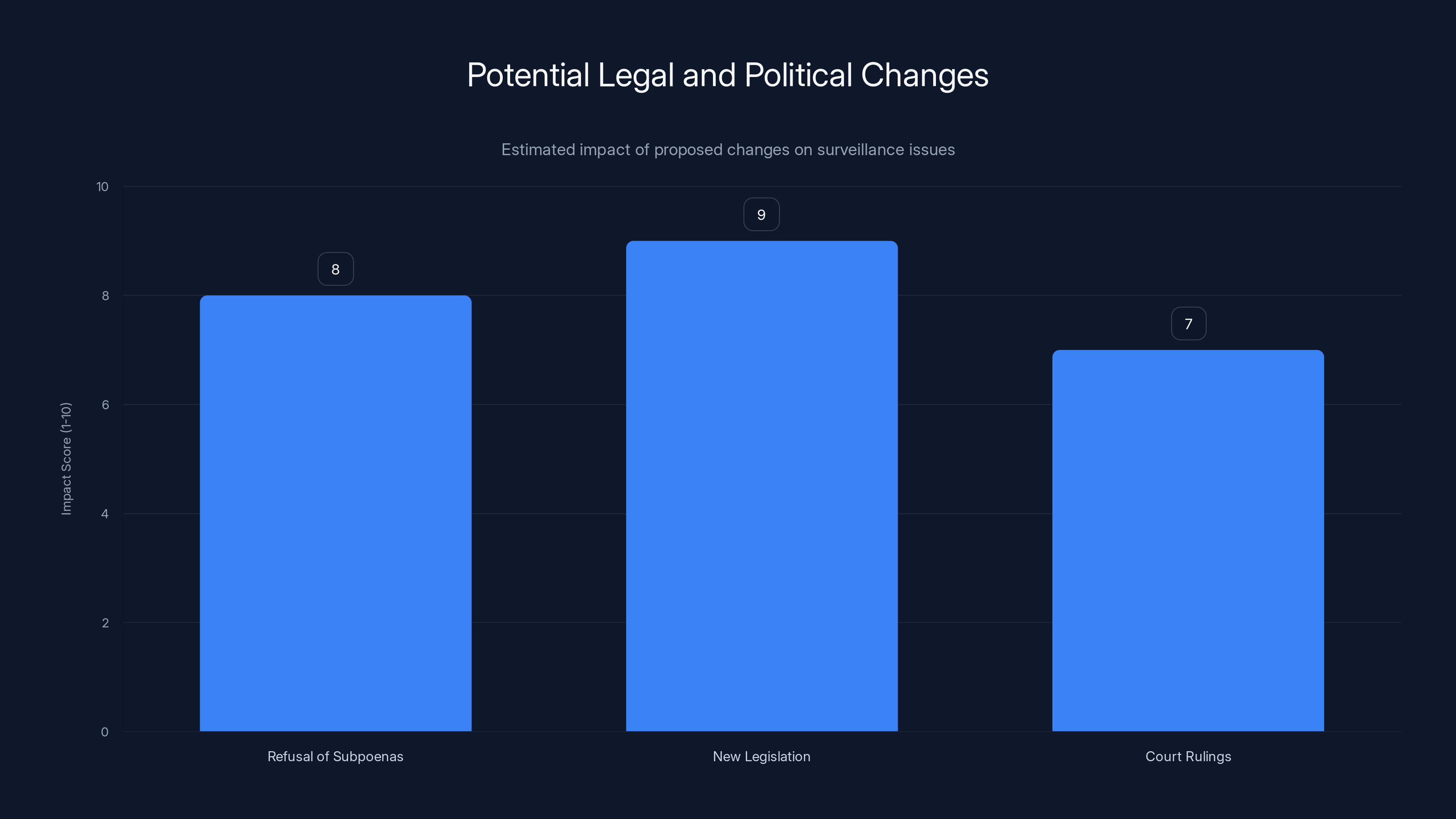

Estimated effectiveness scores suggest requiring judicial review and eliminating subpoena authority could be the most impactful legislative solutions. Estimated data.

Why Tech Companies Keep Complying: The Economics of Compliance vs. Resistance

Let's be pragmatic about this. Why would Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and other major platforms comply with these requests when they're not legally required to?

There are several factors at play.

First, compliance is easier than resistance. Challenging a government request requires legal resources, time, and institutional will. It means saying no to a federal agency. Most companies prefer not to antagonize government. Compliance is frictionless.

Second, there's no meaningful penalty for compliance. If Google hands over data and violates someone's privacy, who sues? The individual affected? They'd need to know about it first, which the gag order prevents. They'd need legal resources to mount a case. And they'd need to prove damages. Meanwhile, if Google refuses a government request and gets fined or faces other legal consequences, that directly impacts the bottom line.

Third, there's an assumption of legitimacy. When a government agency makes a request, there's a tendency in institutions to treat it as inherently valid. The agency says it needs the data. The request is documented. It must be legal, or the company would have heard about it, right? This assumption is deeply flawed, but it's pervasive.

Fourth, there's compliance infrastructure already built. Google, Microsoft, and other platforms receive thousands of government requests every year. They have entire legal teams and processes dedicated to handling these requests. There's institutional momentum. The machinery of compliance is already running.

Fifth, the liability calculus favors compliance. If Google complies and someone gets hurt, the responsibility rests with the government agency, right? If Google refuses and the government claims it's obstructing justice or breaking the law, suddenly Google is liable. From a pure legal risk perspective, compliance looks safer.

But here's what's missing from that analysis: the broader harm. When tech companies consistently comply with surveillance requests, they enable government overreach. They make targeting activists cheaper and easier. They signal that dissent will be monitored and documented.

One company standing alone against government surveillance probably gets crushed. But if Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta all refused to comply with administrative subpoenas without judicial review, the landscape would change overnight. The government couldn't sue all of them. It couldn't practically pressure all of them. The legal burden would shift.

But that would require coordinated action. And big tech doesn't do that.

The Timeline: How Fast This Happened

One detail in this case bears emphasizing because it reveals something important about the relationship between government agencies and tech companies.

Cornell notified Thomas-Johnson that her visa had been revoked.

Within two hours, ICE issued an administrative subpoena.

Within some unknown timeframe after that, Google complied.

Two hours. That's the time window between government action and the demand for data. This suggests coordination, or at minimum, an extraordinarily efficient targeting process.

How did ICE even know to request Thomas-Johnson's data? How did they connect her to a Google account so quickly? Were they monitoring the protest in real-time? Were they tracking who attended through facial recognition or other surveillance technology? Did Cornell provide them with information about students involved in the protest?

These questions aren't answered in the reporting, but they point to a larger truth: this didn't happen in isolation. The speed and efficiency suggest a systematic process, not a one-off request.

It suggests that when the government wants to surveil someone, the machinery is already in place. When they want data from tech companies, compliance is expected and swift.

The timeline shows a rapid sequence of events, with only two hours between visa revocation and subpoena issuance, and an estimated additional two hours for data compliance. Estimated data.

What Happens to the Data Once It's Handed Over

This is where the story gets darker.

When Google handed over Thomas-Johnson's information, she immediately became a more legible target. ICE had her address. They had her phone number. They had her financial information. They had technical identifiers that connected multiple accounts and devices to her.

With that data, ICE could:

- Build a comprehensive profile of her contacts, movements, and activities

- Cross-reference her information with other databases

- Identify associates by looking at shared IP addresses, payment methods, or account patterns

- Track future activity if they monitor the accounts in question

- Make determinations about her visa status, deportation eligibility, or legal status with comprehensive knowledge of her digital life

The data doesn't just answer a question. It creates a foundation for ongoing surveillance.

And because the subpoena included a gag order, Google couldn't tell her any of this was happening. She had no opportunity to challenge the request, appeal the government's decision, or even understand why her data was being sought.

From a civil liberties perspective, this is precisely backwards. Someone targeted for surveillance should have the maximum opportunity to defend themselves. Instead, they have zero opportunity. The system is entirely opaque from the target's perspective.

The Constitutional Questions Nobody's Asking Loudly Enough

Let's step back and think about constitutional principles.

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. It requires that "no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

Administrative subpoenas bypass this requirement. There's no probable cause. There's no oath. There's no particular description. There's just an agency saying it wants information.

The argument defenders of administrative subpoenas make is that the Fourth Amendment applies to "searches," and asking for metadata from a third party (Google) isn't technically a search. It's a third-party disclosure. The company consents to provide it because the company isn't the target of the government's investigation; the individual is.

But this argument collapses when you think about it for more than a few seconds. If the government can compel third parties to reveal everything they know about you without judicial oversight, the Fourth Amendment protection becomes meaningless. It's not protecting your privacy; it's just adding a step.

The First Amendment problems are equally serious. When the government uses surveillance and de-anonymization tools to target protesters, journalists, and activists, it chills speech. People know they might be identified. They know their financial data, their contacts, their locations might be given to government agents. Rationally, some people choose silence.

That's not free speech. That's surveillance-induced conformity.

The Fifth Amendment provides due process rights. Administrative subpoenas, issued without notice and paired with gag orders, deny the affected party any process at all. Due process requires the ability to be heard, to challenge evidence, to defend yourself. Administrative subpoenas do the opposite. They're inherently secret from the perspective of the person they target.

No one is saying these arguments are being seriously litigated right now. Some civil rights organizations are pushing back, but these cases take years. By the time a court rules on the constitutionality of administrative subpoenas, thousands of people will have been surveilled.

Estimated data suggests Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft have high compliance levels with government data requests, while Discord and Reddit show lower compliance due to civil liberties awareness.

How Other Tech Companies Responded (And What That Means)

Google isn't alone in this. The Electronic Frontier Foundation's letter was addressed to seven companies: Amazon, Apple, Discord, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Reddit.

These aren't companies that communicate privately with government agencies. They're large, sophisticated firms with massive compliance operations and institutional memory. They know what they're doing.

Amazon, for instance, hosts ICE's cloud infrastructure. Amazon Web Services is a critical platform for federal agencies, including ICE. That puts Amazon in a uniquely complicated position. If Amazon refused to comply with administrative subpoenas for data, would ICE threaten to pull their contract? Probably not explicitly, but the threat would be implicit.

Meta has been cooperative with government requests for years. Meta's own transparency reports show thousands of government data requests annually, and the company complies with the vast majority of them. The company has argued that it challenges requests when it believes they're improper, but the bar for "improper" seems remarkably low.

Microsoft positions itself as business-friendly and regulation-friendly. Compliance with government requests fits that brand positioning. Resistance would mean friction with customers and regulators.

Discord, Reddit, and Apple are slightly different. Discord and Reddit serve communities that skew toward civil liberties consciousness. There's more internal awareness that compliance with surveillance requests is politically fraught. But compliance is still the default.

Apple has made limited privacy commitments, but Apple also manufactures in China and has made substantial accommodations to Chinese government censorship demands. The company's commitment to privacy is selective and geographically contingent.

What's notable is that none of these companies have publicly committed to refusing administrative subpoenas without judicial review. None have committed to notifying users when their data is requested. None have made transparency a priority.

The EFF's letter demands all three. As of early 2025, major tech companies have not meaningfully responded to those demands.

The Visa Revocation Question: Due Process Denied

One element of the Thomas-Johnson case deserves more scrutiny than it typically gets: the visa revocation itself.

She attended a protest. Cornell notified her that her visa was revoked. There's no public record of any hearing, any opportunity to respond, any explanation of what she did wrong.

Visa revocation is a federal power, handled by the State Department and ICE. The process for revoking a student visa for misconduct typically includes some opportunity for the student to defend themselves. It's supposed to be fair and transparent.

But in this case, it appears to have been neither.

This raises a distinct set of questions about immigration enforcement and student rights. International students are in a precarious position legally. Their presence in the United States is contingent on maintaining proper visa status and following university rules. Attending a protest might violate university rules, depending on university policy and the nature of the protest. But it shouldn't automatically justify visa revocation.

Yet the government apparently decided it did.

The speed is telling. The decision to revoke her visa came quickly, suggesting either that the decision was made in real-time during the protest or that the government had already decided to target her for other reasons (her journalism, her activism, her identity as a British national at a Palestinian solidarity event).

Student visas are particularly vulnerable to government abuse because students are dependent on the government for their legal status. They can't just leave. They can't just refuse to answer questions or resist government surveillance. Their future in the country depends on complying with whatever the government demands.

This makes students a particularly important group to protect in surveillance contexts. Instead, they're particularly vulnerable.

Estimated data: New legislation and refusal of subpoenas could have the highest impact on reducing surveillance issues.

What Journalists and Activists Need to Know Right Now

If you're a journalist, an activist, or someone who plans to exercise your First Amendment rights, here's what the Thomas-Johnson case teaches you:

Your data is not protected by administrative subpoena standards. Tech companies can hand over your personal information to government agencies without a court order, without notice to you, and without opportunity for you to challenge it.

Your location is vulnerable. IP addresses, device identifiers, and payment information create a technical fingerprint that can place you at specific times and locations. The government can use this to document who attended protests, who visited certain places, who was in proximity to certain events.

Your financial information reveals patterns. Credit card and bank account data shows what you buy, where you travel, who you interact with. Combined with other data, it creates a comprehensive picture of your life and associations.

Anonymity is fragile. If you document ICE raids on an anonymous account, that anonymity can be pierced by a simple administrative subpoena to the company hosting your account. You could be de-anonymized without knowing it's happening.

Gag orders prevent you from defending yourself. When a company receives an administrative subpoena with a gag order, you may never learn that your data was demanded. You can't hire a lawyer to fight it. You can't appeal. You find out after the fact.

International students are particularly exposed. If you're on a visa that depends on maintaining good relations with the government or the institution, your ability to resist surveillance and government demands is severely limited.

What can you do?

First, understand that the problem isn't necessarily Google's compliance with this particular request. The problem is the system that allows administrative subpoenas to bypass judicial oversight. The immediate problem is that tech companies have not committed to challenging these requests or notifying users.

Second, support organizations pushing back on this. The American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and other civil rights groups are working on legislative and legal challenges to administrative surveillance powers. Your voice and support matter.

Third, understand your own exposure. Use privacy tools. Use VPNs if you're concerned about IP logging. Don't store financial information with companies unless necessary. Understand that any data you provide to a tech company can potentially be subpoenaed.

Fourth, consider the companies you use. This doesn't mean you need to abandon Google or other major platforms; they're often essential for work and communication. But be aware of the trade-offs. Consider where you store sensitive information. Consider what you share, what you search for, what you document.

The Role of Universities in Surveillance

One actor in this story deserves particular scrutiny: Cornell University.

It's not clear from public reporting exactly how ICE learned about Thomas-Johnson or obtained enough information about her to target her so quickly. But universities are obvious pressure points. Students register with universities. Their visa status is verified through university systems. Their on-campus activities are documented.

If ICE coordinated with Cornell—asking the university to identify students involved in the protest, for example—that would explain the timing. Cornell might have provided names, addresses, and other identifying information that ICE then used as a basis for administrative subpoenas.

Universities occupy an interesting position. They're educational institutions, but they're also compliance systems. They verify student visa status for the government. They're responsible for ensuring international students follow the law. They're accountable to government in ways domestic students aren't.

What are universities' obligations when government agencies request student information? Do universities have to comply with administrative subpoenas? Are universities supposed to notify students when their information is requested?

These questions aren't clearly answered. Different universities have different policies. Some have strong student privacy advocates who push back on government requests. Others are more cooperative with law enforcement.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: universities have incentives to cooperate with government. They depend on federal funding, federal student loan programs, and federal research funding. If a university refuses to cooperate with ICE, that relationship could suffer.

Students at American universities should understand that their institutions are not unconditional advocates for their rights. Universities are also gatekeepers for law enforcement and immigration authorities.

The Transparency Question: What We Don't Know

One thing this case makes clear is how little we know about government surveillance requests to tech companies.

Google publishes a transparency report. It includes aggregate data about government requests. The company reports that it received hundreds of thousands of government requests for user data in 2024. But the report doesn't break down requests by type. It doesn't distinguish between warrants, subpoenas, administrative subpoenas, and other forms of request.

It doesn't tell you how many times the government successfully de-anonymized activists. How many times administrative subpoenas were used to target protesters. How many journalists were identified through data handovers.

The EFF's letter specifically demanded better transparency. Companies should report, the EFF argued, on the volume and nature of administrative subpoena requests. They should distinguish between different types of requests and different outcomes. They should be transparent about how often they challenge government demands versus comply.

Without that information, we're flying blind. We know about the Thomas-Johnson case because The Intercept reported on it. But how many similar cases happen without media attention?

The burden of transparency shouldn't fall on investigative journalists to expose every surveillance abuse. It should fall on tech companies and government agencies to be forthcoming about how surveillance systems are used.

Right now, they're not.

Legislative Solutions: What Would Actually Fix This

A real solution to this problem would require legislative action. Congress would need to pass new laws restricting how administrative subpoenas work or requiring stronger protections for data subjects.

Possible legislative approaches:

Eliminate administrative subpoena authority for immigration-related surveillance. Congress could pass a law saying that ICE and related agencies can't use administrative subpoenas to surveil people or gather data about their activities. They'd need actual warrants for those purposes, which would require showing probable cause to a judge.

Require judicial review before compliance. Congress could mandate that tech companies refuse to comply with administrative subpoenas unless the government first gets a judge to confirm that the subpoena is legal and constitutional. This flips the burden—the government has to prove its request is legitimate before companies hand over data.

Mandate notice and opportunity to challenge. Congress could require that people who are the subject of administrative subpoenas be notified within a set timeframe (say, 30 days) so they can seek legal help to challenge the request. The notification period could be extended for law enforcement reasons, but complete secrecy shouldn't be automatic.

Strengthen data minimization requirements. Congress could require that administrative subpoenas be as specific as possible about what data is being sought and why. A blanket request for "all data associated with this account" shouldn't be allowed. Agencies would need to justify each category of data they're seeking.

Create civil liability for unlawful requests. Congress could establish that individuals harmed by unlawful administrative subpoenas can sue the government for damages. This would create incentive to be careful about how these powers are used.

Require transparency reporting. Congress could mandate that government agencies report annually on how many administrative subpoenas they issue, to which companies, for what purposes, and what fraction are challenged or denied. This transparency would create accountability.

Are any of these solutions likely to pass? Not immediately. The Trump administration appears to support expansive use of immigration enforcement power, which includes surveillance authority. Congress is currently controlled by Republicans, and administrative subpoena power has been used by multiple administrations for various purposes.

But the legal landscape is starting to shift. Civil rights organizations are challenging these powers in court. The momentum for privacy protection is growing, particularly after visible cases like Thomas-Johnson's. It's not a guaranteed path to change, but change is possible.

International Implications: What This Means Beyond the US

The fact that Thomas-Johnson is British is not incidental to this story.

International students, international visitors, and people with family abroad are all affected by this surveillance. If you're not a U.S. citizen, you're in a more precarious legal position. Your visa status is contingent. Your ability to challenge government demands is limited.

But beyond that, this case has international implications. It suggests that the U.S. government is willing to surveil, de-anonymize, and target people based on their political beliefs and protest activity. That's a message to international journalists, activists, and students: if you come to the United States, your data is not safe. Your political activity will be documented. Your associations will be revealed.

Countries like China are watching this. China's surveillance apparatus is vast and well-known. But the U.S. is supposed to operate under constitutional protections and rule of law. When the U.S. government uses surveillance tools to target political dissent, it undermines the moral authority that the U.S. claims when criticizing other countries' surveillance practices.

It also affects international trust in U.S. tech companies. If you're a foreign national, would you feel safe storing data with Google, Microsoft, or Amazon knowing that those companies will hand over your personal information to immigration authorities without a warrant?

That's not a technical problem that can be fixed with encryption. That's a governance problem. It requires changing how the U.S. government uses surveillance authority.

What Comes Next: The Legal and Political Landscape

As of early 2025, the Thomas-Johnson case is not the subject of ongoing litigation. She would have to file suit herself to challenge what happened. That would require finding a lawyer, understanding her legal rights as a British national in the U.S., and being willing to take on the government and a major tech company.

But broader legal challenges are underway. Civil rights groups have filed suits challenging ICE's use of administrative subpoenas. Those cases will take years to litigate. In the meantime, the government will continue to use these powers.

Politically, the conversation is starting to shift. Major tech companies are facing pressure to be more transparent and more protective of user privacy. The European Union has strict data protection laws that constrain how companies operate. The U.S. doesn't have equivalent laws, but the conversation is moving in that direction.

What would meaningful change look like? Companies committing to refuse administrative subpoenas without judicial review. Congress passing new legislation constraining immigration enforcement surveillance. Courts ruling that administrative subpoenas violate the Fourth Amendment when used to target speech and protest activity.

None of that is guaranteed to happen. But the Thomas-Johnson case has shown that the current system is broken. It's failed to protect a student journalist who did nothing illegal. It's failed to constrain government surveillance power. It's failed to hold tech companies accountable for complying with questionable requests.

Fix those failures, and you fix a substantial chunk of the surveillance problem in the U.S.

FAQ

What is an administrative subpoena?

An administrative subpoena is a legal demand for information issued directly by a federal agency without requiring approval from a judge or court. Unlike a warrant, which requires showing probable cause to a judge, an administrative subpoena can be issued based solely on an agency's determination that it needs the information. While companies aren't legally required to comply with administrative subpoenas, most do.

How is an administrative subpoena different from a warrant?

A warrant requires judicial approval and a showing of probable cause that a crime occurred. An administrative subpoena requires neither. A warrant can be challenged in court and must be executed with reasonable particularity. An administrative subpoena can be issued broadly and is often accompanied by gag orders that prevent companies from notifying the affected person. Additionally, people subject to warrants have the right to challenge them; people targeted by administrative subpoenas often don't know they've been issued.

Why did Google comply with the administrative subpoena?

Google is not legally required to comply with administrative subpoenas, but the company chose to do so without publicly explaining its reasoning. Companies often comply because resistance requires legal resources and institutional will to oppose government agencies, compliance is the default mode, there's an assumption that government requests are legitimate, and the company's existing compliance infrastructure makes it easier to say yes than no.

What data did ICE obtain through the subpoena?

Google provided usernames, physical address, phone numbers, subscriber information and identities, IP addresses, and credit card and bank account numbers linked to the account. While administrative subpoenas can't compel companies to turn over email contents or search histories, they can demand metadata and identifiable information, which is what ICE received in this case.

Can companies refuse to comply with administrative subpoenas?

Yes, tech companies can legally refuse to comply with administrative subpoenas. Companies are not under the same legal obligation to comply as they are with court-ordered warrants. However, most major tech companies treat administrative subpoenas as routine requests and comply without challenging them. The Electronic Frontier Foundation argues that companies should refuse compliance unless the government first obtains judicial approval.

What rights did Amandla Thomas-Johnson have to challenge the subpoena?

Thomas-Johnson had virtually no rights to challenge the subpoena. The subpoena included a gag order that prevented Google from notifying her that her data was being requested. She didn't learn about the government's demand until the story was reported by The Intercept. By the time she knew what had happened, her data had already been handed over and was in government possession. Without knowing about the subpoena, she couldn't hire a lawyer to challenge it or participate in any legal process.

What can tech companies do to protect user privacy?

According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, tech companies should commit to challenging administrative subpoenas in court before complying, require that the government obtain judicial approval before data is turned over, notify affected users about data requests with meaningful time to challenge the subpoenas themselves, and provide transparency about the volume and nature of government data requests through detailed transparency reports.

Can international students be targeted through administrative subpoenas?

Yes, international students are particularly vulnerable because their visa status gives the government additional leverage. An international student can't simply refuse to cooperate with government requests because that could result in visa revocation and deportation. Additionally, international students may not understand their legal rights in the U.S. and may have limited access to legal assistance to challenge government surveillance.

What is the difference between data content and metadata?

Data content includes the actual substance of communications, like the text of emails or search queries you perform. Metadata includes information about communications and account usage, like IP addresses, phone numbers, payment methods, and account activity patterns. Administrative subpoenas can demand metadata but not content, though metadata is often more revealing of a person's patterns, associations, and locations than content alone.

What should people do to protect themselves from surveillance?

Understand your exposure, use privacy tools like VPNs when concerned about IP logging, be thoughtful about what data you store with which companies, consider using encrypted communications for sensitive discussions, support organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation that are challenging surveillance powers, and understand that no perfect solution exists under the current system—the real solution requires legislative and legal change.

Conclusion: The Urgent Need for Change

The Amandla Thomas-Johnson case is a window into how surveillance actually works in the United States in 2025.

It's not dramatic or theatrical. There are no dramatic raids. The government doesn't announce what it's doing. A student attends a protest. A visa is revoked. A subpoena is issued. A tech company complies. The person finds out through a news story.

What makes it so dangerous is how normal it feels. How routine. How unexceptional.

This is the kind of surveillance that chills speech. Not because people are consciously thinking about it when they decide whether to protest, but because at some level, everyone knows the risk exists. Everyone knows their data is not protected by law. Everyone knows that political activity can be documented and used against them.

What needs to change is structural.

First, Congress needs to pass laws constraining administrative subpoena authority for surveillance purposes. Immigration enforcement is important, but it can happen through legitimate, judicially-overseen legal processes. It doesn't need to bypass the courts.

Second, tech companies need to commit to refusing administrative subpoenas without judicial review. That commitment is voluntary right now, and it's not happening. Companies need to make the choice to protect privacy even when it means friction with government.

Third, we need better transparency. We need to know how often this happens, how many people are targeted, what happens to the data once it's obtained. Sunshine is supposed to be the best disinfectant, but surveillance works in darkness.

Fourth, courts need to start ruling that administrative subpoenas, at least in the context of surveillance and de-anonymization, violate constitutional protections against unreasonable searches.

None of this will happen overnight. But the Thomas-Johnson case shows why it's urgent.

She did nothing wrong. She exercised her constitutional rights. She paid for the education. She followed the law.

And the government surveilled her anyway, and a tech company made it easy.

That's not a system designed for freedom. That's a system designed for control.

Change requires recognizing that difference. And acting on it.

Key Takeaways

- Google handed over extensive personal and financial data to ICE without a judge's approval, demonstrating how administrative subpoenas bypass constitutional protections

- Administrative subpoenas allow federal agencies to demand data directly without judicial oversight, and tech companies aren't legally required to comply but do anyway

- The surveillance pattern targets protesters, activists, and people critical of the Trump administration, using de-anonymization and data collection to chill free speech

- Tech companies have not committed to challenging these requests or notifying users, and gag orders prevent surveillance targets from defending themselves

- Meaningful change requires legislative action to constrain administrative subpoena authority, corporate commitment to refuse unlawful requests, and court rulings protecting constitutional rights

Related Articles

- ICE Out of Our Faces Act: Facial Recognition Ban Explained [2025]

- Apple's Lockdown Mode Defeats FBI: What Journalists Need to Know [2025]

- ICE Domestic Terrorists Database: The First Amendment Crisis [2025]

- Telegram Russia Restrictions: Government Slowdown & Blocked Access [2025]

- ICE Office Expansion Across America: What You Need to Know [2025]

- How to Cancel Discord Nitro: Age Verification & Privacy Concerns [2025]