Apple's Lockdown Mode Defeats FBI: What Journalists Need to Know [2025]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation ran into a wall. They had a warrant, they had the device, and they had legal authority to access the data. But they couldn't get in.

In January 2025, FBI agents executed a search warrant at the Virginia home of Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson as part of an investigation into a Pentagon contractor accused of leaking classified information. They seized her iPhone 13, two MacBook Pro laptops, a portable hard drive, a voice recorder, and a smartwatch. What happened next revealed something critical about digital security in America: a feature most people have never heard of just proved stronger than the most powerful law enforcement agency in the world.

Apple's Lockdown Mode protected Natanson's iPhone so effectively that the FBI's elite forensics team, the Computer Analysis Response Team (CART), couldn't extract a single piece of data from it. But the agents found another way. They forced Natanson to unlock her work MacBook Pro using her fingerprint, gaining access to her encrypted Signal messages and a contact list of 1,100 government sources.

This case sits at the intersection of three things Americans care about deeply: privacy, national security, and press freedom. It raises uncomfortable questions about what happens when personal security clashes with law enforcement authority, and what it means when a supposedly unbreakable security feature meets a legal warrant.

Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of device security in America.

Understanding the Case: How an FBI Search Became a Privacy Flashpoint

The sequence of events matters because it reveals exactly how strong Lockdown Mode is and exactly what law enforcement can still force through.

On January 14, 2025, FBI agents arrived at Natanson's home with a search warrant tied to a Pentagon leak investigation. Natanson is a national security reporter who covers the Defense Department, and someone in that world apparently leaked classified documents. The investigation wasn't about her reporting, but they wanted her communications to identify their source.

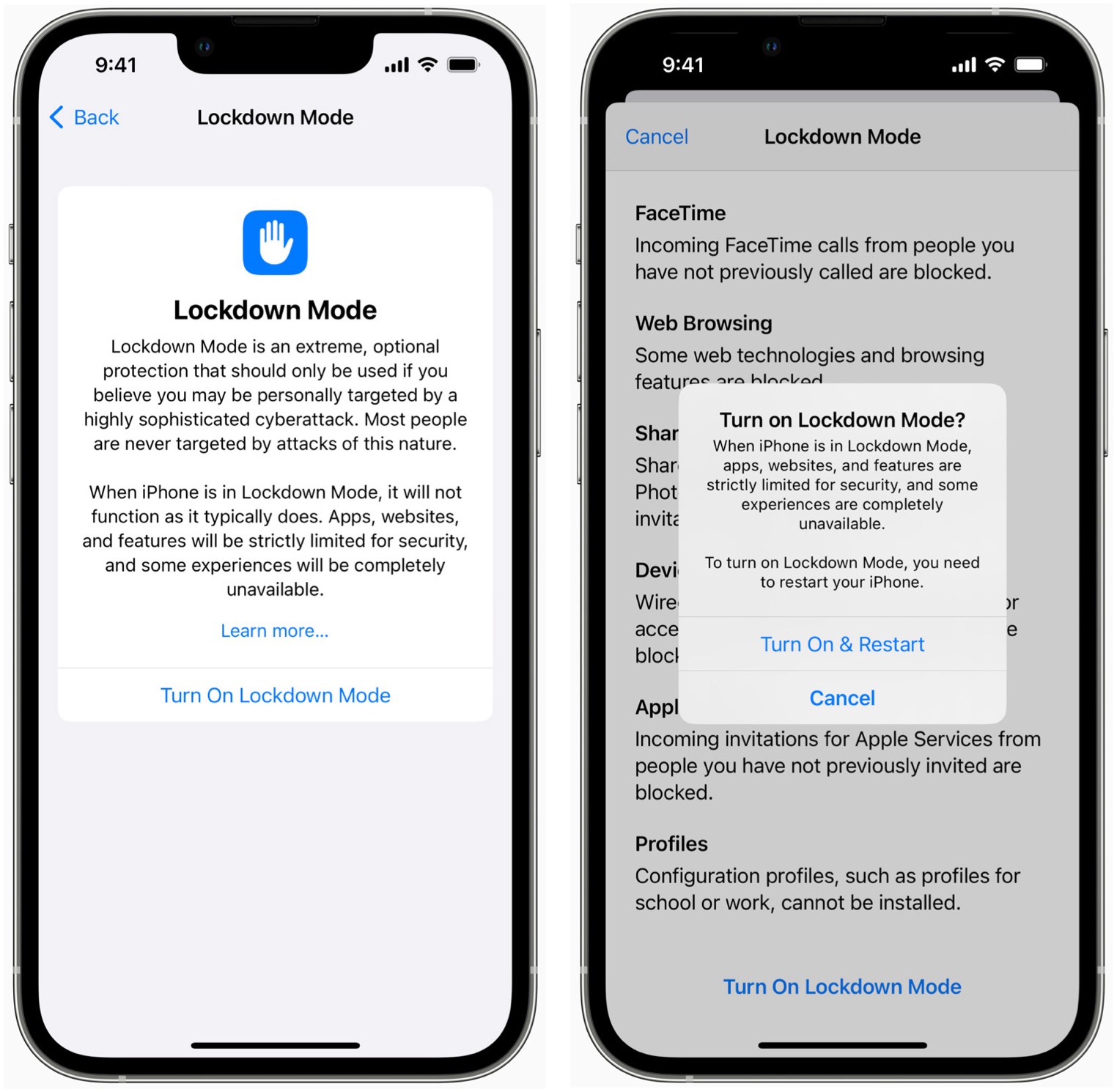

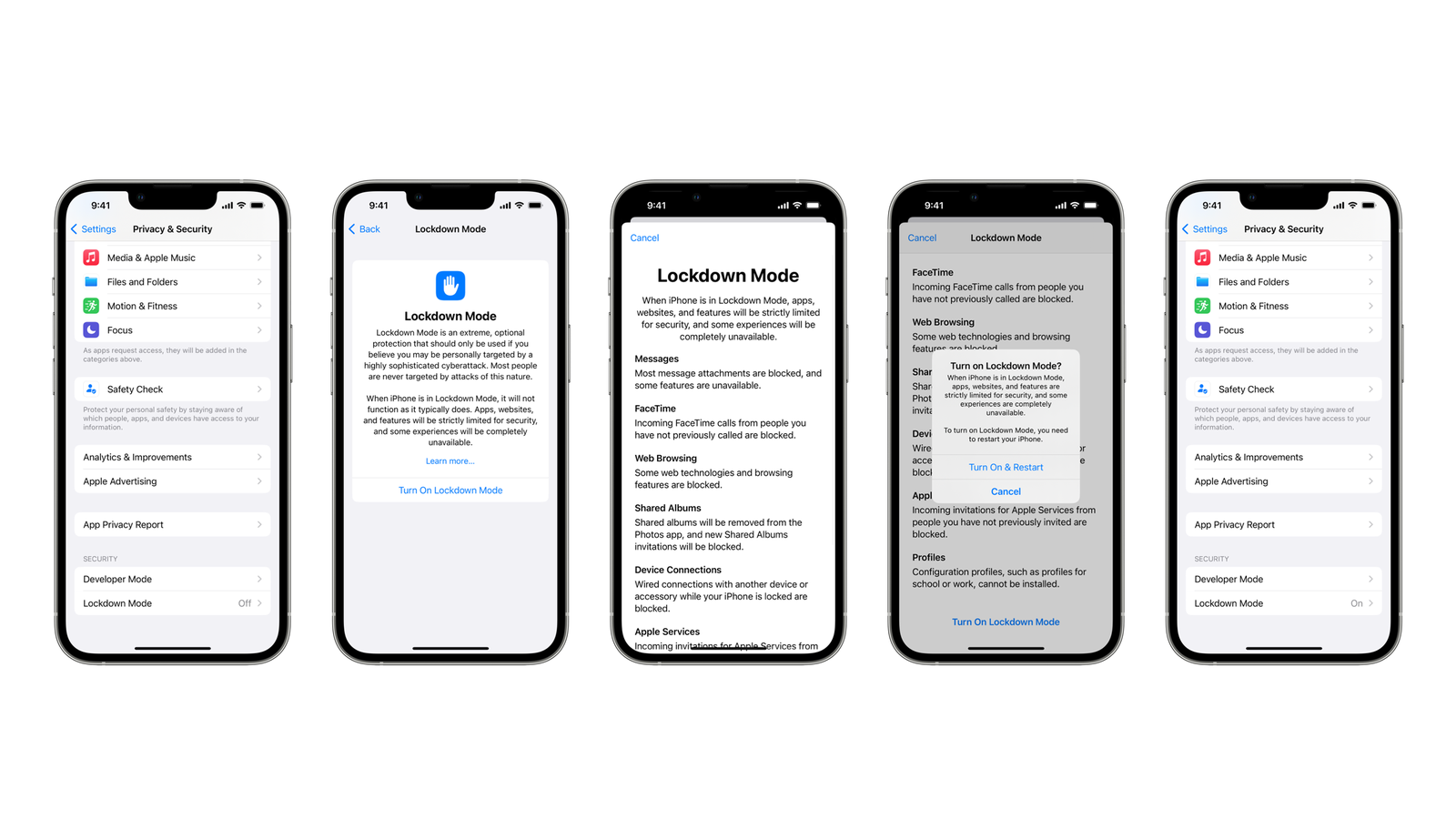

When agents searched her home, they found the iPhone 13 powered on and charging. The screen displayed a single message: the device was in Lockdown Mode. They also found two MacBook Pro laptops, one belonging to the Washington Post and one personally owned by Natanson. One was powered off. The other, owned by the Post, was powered on but locked, sitting in a backpack in the kitchen.

The agents took everything to FBI headquarters in Washington, DC. That's when they hit the wall with the iPhone. According to a court filing by the government, "Because the iPhone was in Lockdown Mode, CART could not extract that device." No data. No messages. No contact information. Nothing. The FBI's specialized forensics team, which regularly cracks phones that ordinary people can't access, simply couldn't penetrate this one.

But they had better luck with the MacBook Pro. According to the FBI's own declaration, when agents "presented Natanson with her open laptop" and explained they had authority under the warrant to use her biometrics, they asked her to place her index finger on the fingerprint reader. She reportedly told them she doesn't use biometrics on her devices. They insisted, under the warrant's authority. Her fingerprint unlocked the laptop immediately.

Inside that laptop, investigators found what they were after: Signal messages and her entire contact database of government sources. The Post later told the court that her Signal account contained messages with over 1,100 current and former government employees, many of them sources for her reporting.

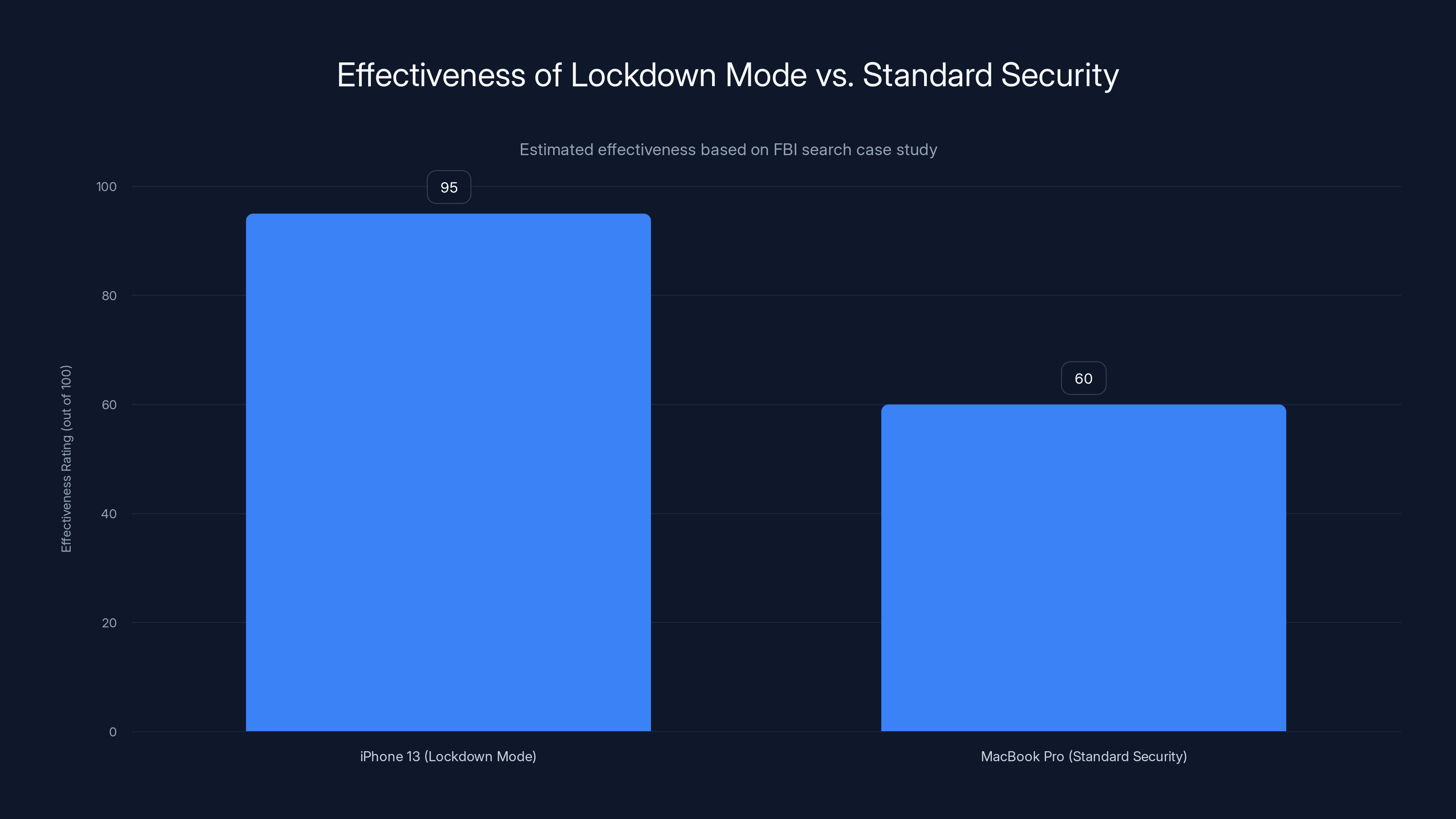

This is the core paradox of the case: one device protected by Lockdown Mode proved absolutely secure against federal law enforcement. Another device, protected only by standard encryption and a password, was opened using the reporter's own biometrics. The question isn't whether the FBI is good at what they do. It's what that tells us about security, rights, and the limits of both.

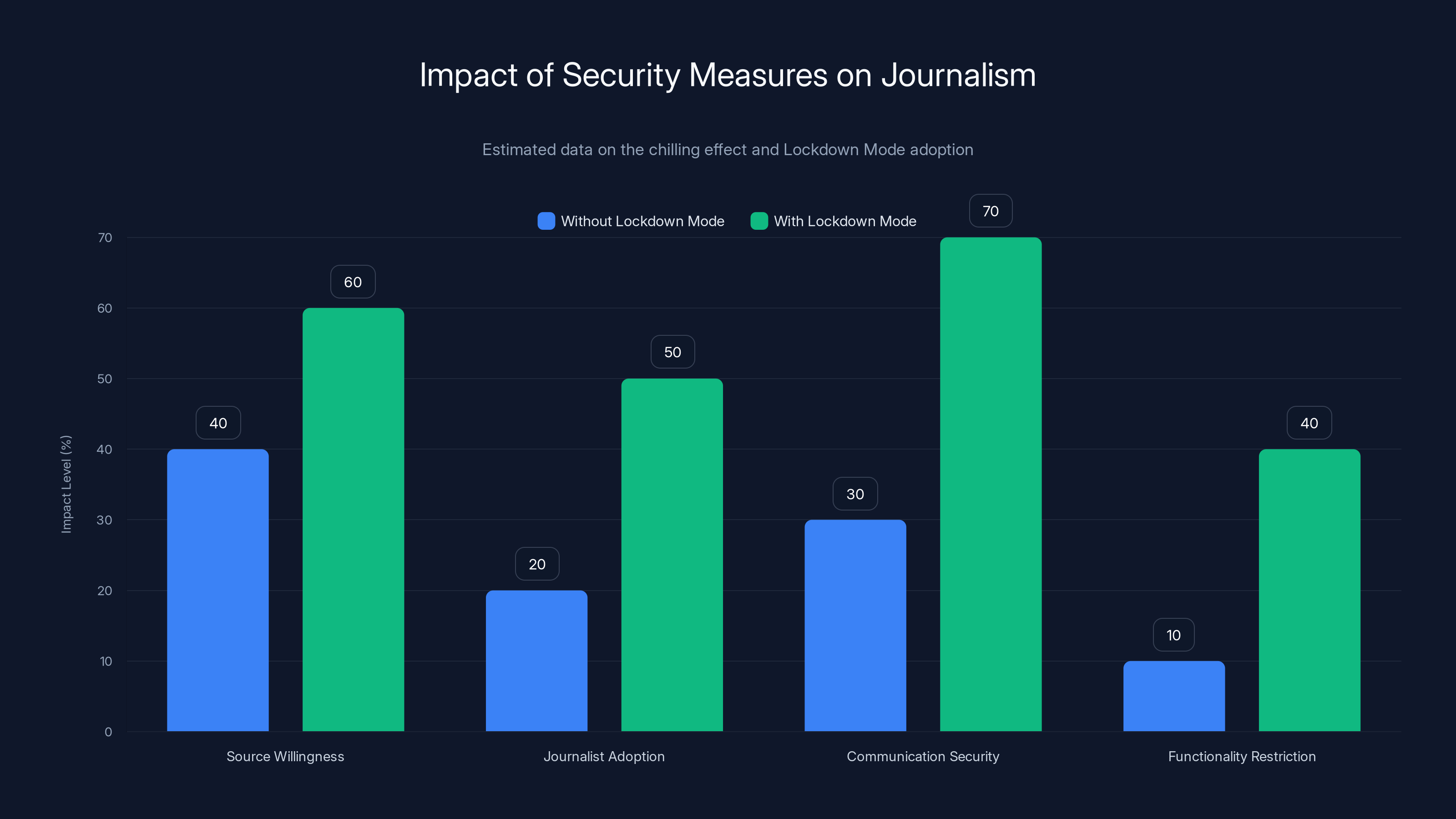

Lockdown Mode proved highly effective, while comprehensive security across devices is crucial. Estimated data based on case insights.

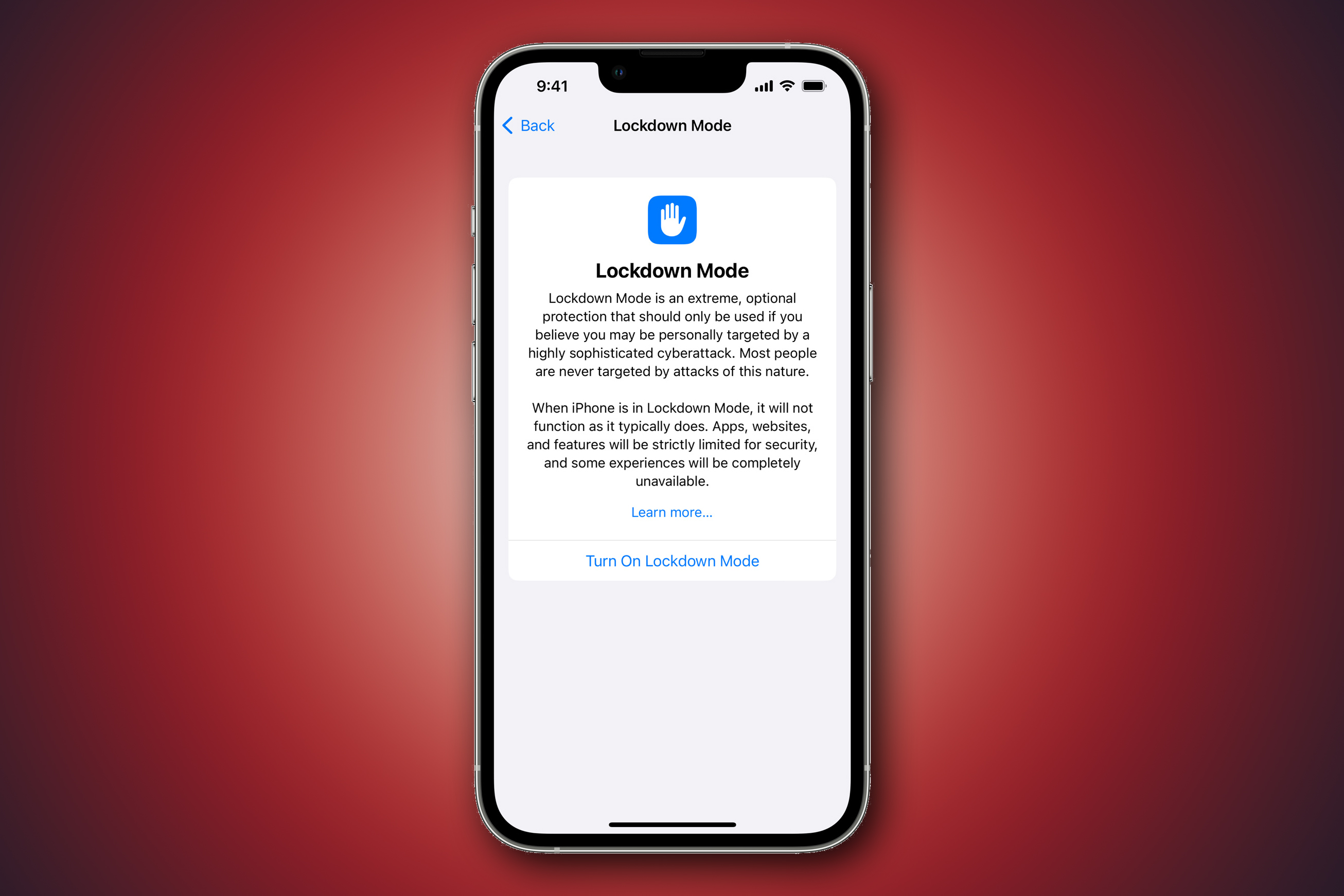

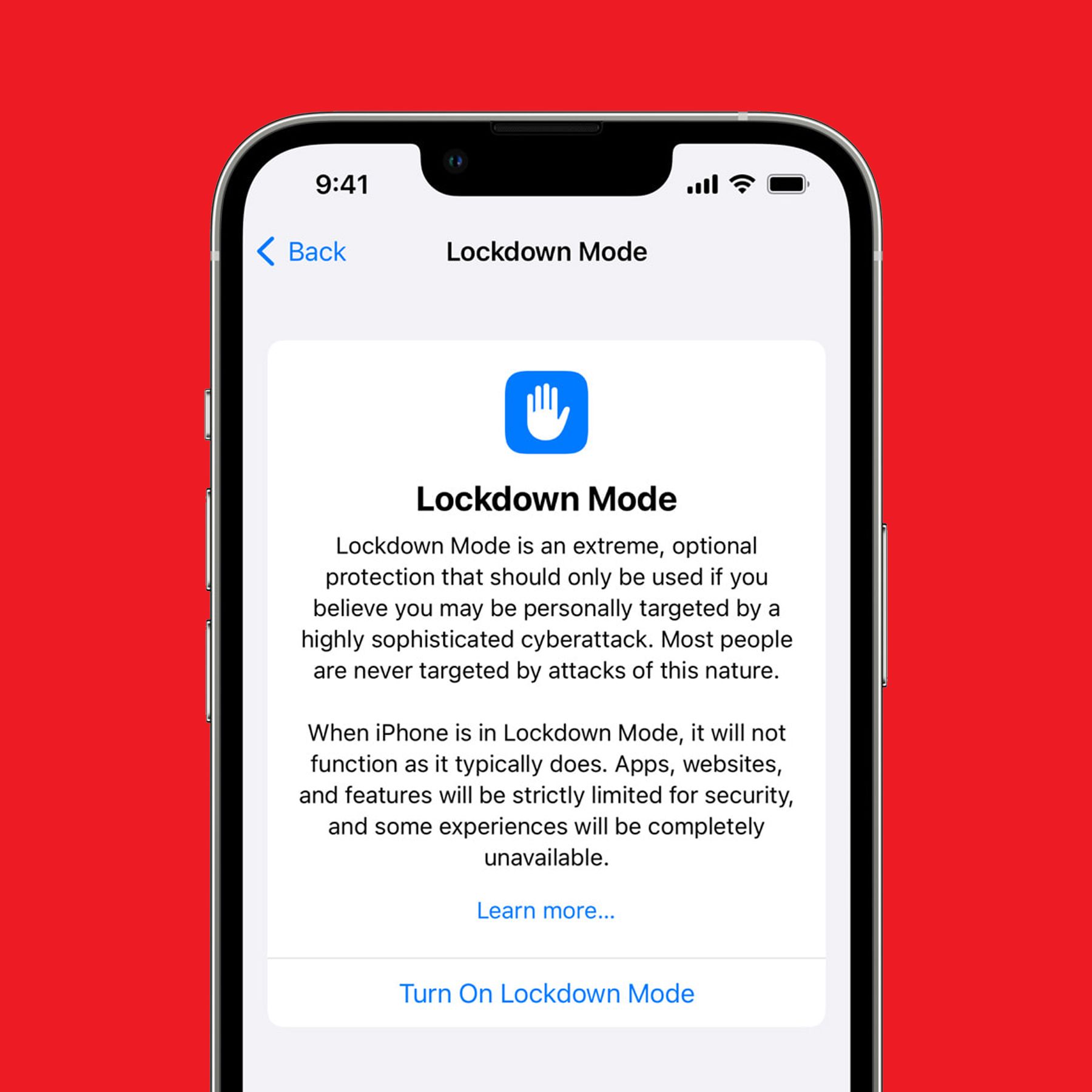

What is Lockdown Mode? A Security Feature Built for Targeted Threats

Most iPhone users have never heard of Lockdown Mode. Apple doesn't advertise it prominently. It's not enabled by default. It's not designed for ordinary people. Lockdown Mode exists for a very specific category of users: people who might be targeted by sophisticated mercenary spyware.

Apple introduced Lockdown Mode in 2022, initially in response to revelations about Pegasus spyware, a tool developed by NSO Group that governments use to surveil journalists, dissidents, human rights lawyers, and activists. Pegasus doesn't work through stupid mistakes or weak passwords. It exploits previously unknown security vulnerabilities, called zero-day exploits, that neither Apple nor anyone else knew existed. A government can pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to NSO Group for access to Pegasus, then deploy it against a specific person.

Lockdown Mode is Apple's answer to this threat. The feature restricts functionality dramatically to close potential attack vectors. When you enable it, your iPhone works differently. Fundamentally differently.

Here's what changes: Most types of message attachments stop working. If someone sends you a photo, document, or video through Messages, your phone won't download it. FaceTime calls from people you haven't contacted in the past 30 days are blocked entirely. Web browsing becomes more restrictive. Websites can't use certain advanced browser technologies that could potentially be exploited. You can't share photos with certain apps. Wired connections to a computer become more limited. Apple Watch pairing is restricted. Configuration profiles stop installing automatically.

The list goes on. And it's intentional. Apple is deliberately making the phone less capable to make it much harder to attack. The tradeoff is functionality. You get security at the cost of convenience.

You can still use your phone. You can still make calls, send texts, browse the web. But the experience is narrower. Some apps that usually work smoothly might behave differently. Features you rely on might be unavailable. This is by design. Apple is betting that if you need Lockdown Mode, the restriction is worth it.

Enabling Lockdown Mode requires deliberate action. You open Settings, navigate to Privacy & Security, scroll down to Lockdown Mode, and turn it on. The same process works on iPad and Mac. Most users never even look for it. But for journalists, activists, dissidents, and others at risk of targeted surveillance, it's a nuclear option for device security.

The question the Natanson case raises is simpler but more profound: if Lockdown Mode can defeat the FBI's forensics team, what does that mean for government authority, press freedom, and the balance between surveillance and privacy in America?

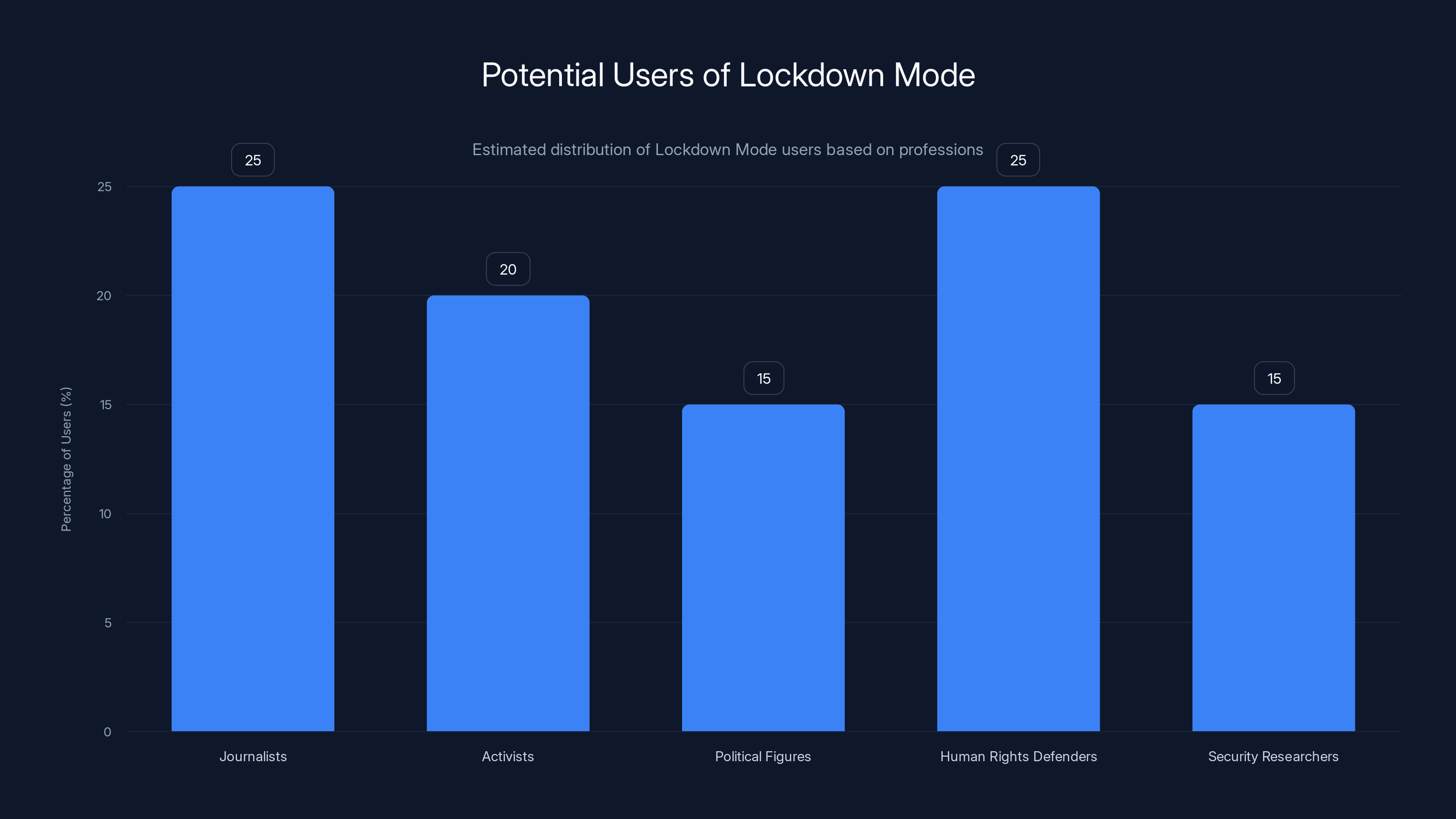

Estimated data shows that journalists and human rights defenders are the primary users of Lockdown Mode, each making up about 25% of the user base.

The FBI's Forensics Team: Why CART Couldn't Crack the iPhone

The Computer Analysis Response Team is not a normal computer repair shop. CART is a specialized unit within the FBI dedicated to one task: extracting data from devices that normal people can't access. They have tools that don't exist in the commercial market. They have access to zero-day exploits, proprietary forensics software, and techniques developed over decades.

When police or federal agents seize a phone, they typically send it to CART. CART has cracked older iPhones. They've extracted data from Android phones. They have success rates that would shock most people. If you have a normal iPhone with a normal passcode, CART can probably get in.

But Lockdown Mode is different. The filing states that after taking the iPhone to the FBI's Washington field office, CART "began processing each device to preserve the information therein." They worked on it. They tried their techniques, their exploits, their tools. And they got nothing.

The declaration by FBI Assistant Director Roman Rozhavsky explains: "Because the iPhone was in Lockdown Mode, CART could not extract that device." The statement is surprisingly straightforward. No excuses. No promises to keep trying. Just a flat statement: we tried, Lockdown Mode stopped us, we stopped trying.

Later, Rozhavsky added that the FBI "has paused any further efforts to extract this device because of the Court's Standstill Order." That's the legal hold placed by the magistrate judge telling the government to stop searching devices while the court decided whether they had to be returned.

But the real message is in what came before: the FBI paused efforts because of the court order, but the implication is clear. Without that court order, would they have continued? Maybe. But the declaration suggests they may not have expected continued efforts to succeed. Lockdown Mode proved sufficient to stop CART's initial attempts, and CART apparently didn't think they had a viable path forward.

This is significant for one reason: the FBI doesn't usually give up on extracting data. CART is aggressive, creative, and equipped with tools most companies don't even know exist. If CART hit a wall with Lockdown Mode, it suggests Apple built something genuinely resistant to the most sophisticated forensic techniques available to American law enforcement.

How the FBI Got Into the MacBook: Biometric Authority Under the Fourth Amendment

The iPhone situation is dramatic. But the MacBook situation is legally fascinating, and in some ways more troubling.

According to the search warrant, the FBI had specific authority to use a person's biometrics to unlock devices. This is a technical reading of Fourth Amendment law that most people don't realize exists. The warrant didn't require Natanson to provide passwords, passcodes, or encryption keys. But it did authorize agents to use her fingerprints, facial recognition, or other biological identifiers to unlock devices.

This is actually a deliberate legal distinction. In 2014, a federal appeals court ruled that the Fifth Amendment (which protects you from self-incrimination) covers passwords and encryption keys. You can't be compelled to reveal them. But a federal magistrate judge in Northern California ruled in 2017 that biometrics are different. Your fingerprint is not protected by the Fifth Amendment in the same way, because a fingerprint is a physical characteristic, not knowledge that exists in your mind.

The logic is: you can be forced to submit to a breathalyzer test. You can be forced to provide a blood sample for DNA. Similarly, you can be forced to provide a fingerprint or face the camera for facial recognition unlock. The key difference in the legal framework is whether you're being compelled to provide information that exists in your brain versus information that exists on your body.

When the FBI presented this authority to Natanson, they told her she had no choice. Natanson allegedly said she doesn't use biometrics on her devices. The FBI told her she must try anyway, in accordance with the warrant's authority. An agent "assisted" her in applying her right index finger to the fingerprint reader. It unlocked immediately.

The FBI's own declaration includes an interesting detail: "Natanson misled investigators about the devices that were seized. She misrepresented to officers that the devices could not be unlocked with biometrics, possibly in order to prevent the Government from reviewing materials within the scope of the search warrant."

This is a critical claim. Natanson said her devices couldn't be unlocked with biometrics. But when the FBI applied her fingerprint, the device unlocked immediately. Either Natanson was lying, or she genuinely didn't know her own device had that capability. The FBI assumes the former. The implication is serious: if a witness misleads federal agents executing a search warrant, that's a potential crime.

But the legal principle is clear under current law: the government can compel you to place your finger on a scanner in ways they cannot compel you to reveal a password. This distinction will shape how law enforcement investigates journalists, activists, and ordinary people for years to come.

The iPhone 13 in Lockdown Mode was significantly more secure, preventing FBI access, while the MacBook Pro with standard security was accessed using biometrics. Estimated data based on case details.

The Signal Messages: Why the Laptop Mattered More Than the iPhone

The FBI's real target wasn't the iPhone's abstract data. It was specific information: Signal messages exchanged between Natanson and her sources. Signal is an encrypted messaging app used by journalists, activists, security researchers, and anyone who wants truly private communication. Messages on Signal aren't stored on Apple's servers. They're stored on your device.

According to the Post, Natanson's Signal account contained a contact list of over 1,100 current and former government employees. Some of them were sources for her reporting on Pentagon issues. The FBI wanted to see which of those 1,100 people Natanson had communicated with recently, and what they said.

This is the value of the iPhone to federal investigators: it's where Signal stores its data. Get access to the iPhone, identify recent contacts, see what information was shared. And the FBI would have done exactly that if Lockdown Mode hadn't stopped them.

But they got into the MacBook, and the MacBook also contained Signal. Once they unlocked it with Natanson's fingerprint, they could access the exact same messaging history. The FBI's declaration states they "were able to view at least some of them on her work laptop." The specific phrase "at least some of them" suggests they didn't get everything, or they faced some limitation accessing historical messages. But they got enough to identify recent communications.

This raises an important point about digital security: having one secure device isn't enough if you have multiple devices. The iPhone was Fort Knox. The MacBook was paper. Once the FBI got through the MacBook, the iPhone became secondary. They had already obtained what they wanted.

For journalists specifically, this is a crucial lesson. The Post owns devices. Natanson owns devices. If the Post's device is less secure than Natanson's iPhone, the FBI's path of least resistance goes through the Post's device. And once they're in, your personal security on another device becomes less relevant.

Digital Rights in a Security-Conscious World: What This Case Reveals

The Natanson case reveals a deep tension in modern America. We have the ability to make devices essentially unbreakable. Apple proved that with Lockdown Mode. But we also have a legal system that says law enforcement with a warrant has broad authority to search devices and access communications.

Lockdown Mode created a situation that law enforcement hasn't really encountered before: a feature so effective that the FBI's elite forensics team couldn't overcome it. Historically, digital security and law enforcement haven't had to face this directly. When law enforcement wanted to search a device, companies found ways to help them. Apple and Samsung didn't make it impossible. They made it difficult, sure, but not impossible.

Lockdown Mode changes that calculation. It makes it impossible. Or at least, so far, the FBI hasn't found a way through.

This creates several implications: First, Lockdown Mode validates the entire premise of strong encryption. For years, law enforcement and national security officials have argued that unbreakable encryption is bad for society because it hinders investigations. Lockdown Mode doesn't solve encrypted communications (those were already encrypted), but it makes the device that stores them impenetrable. It proves encryption works.

Second, it creates unequal security. If you enable Lockdown Mode on your iPhone but use a weaker password on your MacBook, you've created a security chain with a weak link. The FBI found that weak link and exploited it. This isn't a flaw in Lockdown Mode. It's a reality of using multiple devices.

Third, it raises questions about compelled biometric unlocking. The FBI obtained access to the MacBook specifically because the warrant authorized them to use Natanson's biometrics. If Lockdown Mode had been enabled on the MacBook too, could they force her to unlock it the same way? Probably yes, under current law. If so, Lockdown Mode doesn't solve the biometric problem. It just makes it irrelevant if you have multiple devices.

Finally, it highlights something uncomfortable about press freedom and security. Natanson is a journalist protecting sources. Those sources could face serious consequences if identified. The FBI's investigation wasn't about Natanson herself—she wasn't the target. She was the path to finding who leaked classified information. But that path goes through her sources.

When the FBI executes a search warrant on a journalist's home, seizes her devices, and extracts her communications, it affects press freedom in America. Journalists need to communicate with sources confidentially. If sources know the government can obtain those communications with a warrant, they become less willing to talk. The chilling effect on journalism is real.

Lockdown Mode would have prevented this entirely. The iPhone was protected. The information stayed private. But the MacBook wasn't, and through the MacBook, the government got what it needed.

Estimated data suggests that while Lockdown Mode increases communication security and source willingness, it also introduces functionality restrictions that could hinder journalistic work.

Comparing iPhone Security to MacBook Security: Why the Same Company's Devices Differ

Apple makes both iPhones and Macs, but their security models are fundamentally different. This is surprising given that they use similar chip architecture and operating systems. But the differences are significant and deliberate.

The iPhone has always been more security-focused than the Mac. This is partly historical. When the iPhone launched in 2007, security was a core design principle. Users don't run system maintenance on iPhones. You can't install arbitrary files. You can't modify the operating system. Apps are sandboxed and restricted. The phone is designed so users can't shoot themselves in the foot from a security perspective.

Macs, by contrast, are personal computers. Users expect to be able to install software, modify settings, access the file system, and have control. Security on a Mac is more about protecting against external threats than preventing users from making poor choices.

Biometric unlocking works differently on both systems. On an iPhone, Touch ID (fingerprint) or Face ID (facial recognition) can unlock the device and give you access to everything inside. On a Mac, biometric unlock is more limited. It can unlock the device, but accessing sensitive information might require an additional password or authentication.

In Natanson's case, her fingerprint was enough to fully unlock the MacBook Pro. That's because the device was in a default state. Someone could set it up so biometric unlock requires additional authentication for sensitive files, but that's not standard.

Lockdown Mode is also different between devices. On iPhone and iPad, it's a comprehensive feature that restricts many functions simultaneously. On a Mac, Lockdown Mode exists but operates differently. Macs don't have the same app ecosystem or message attachment system as iPhones, so the restrictions are necessarily different.

The practical implication is clear: if you enable Lockdown Mode on your iPhone, you still need to secure your other devices separately. There's no single button that makes all your devices Fort Knox. You have to treat each device independently.

This created the exact vulnerability the FBI exploited. The iPhone was protected. The MacBook wasn't. One secure device doesn't protect you if another device with the same information is less secure.

Why Journalists Are Vulnerable: The Nature of Source Protection in Digital Age

Journalists like Natanson operate in a fundamentally different security environment than ordinary people. They're not protecting their own privacy. They're protecting the privacy of their sources.

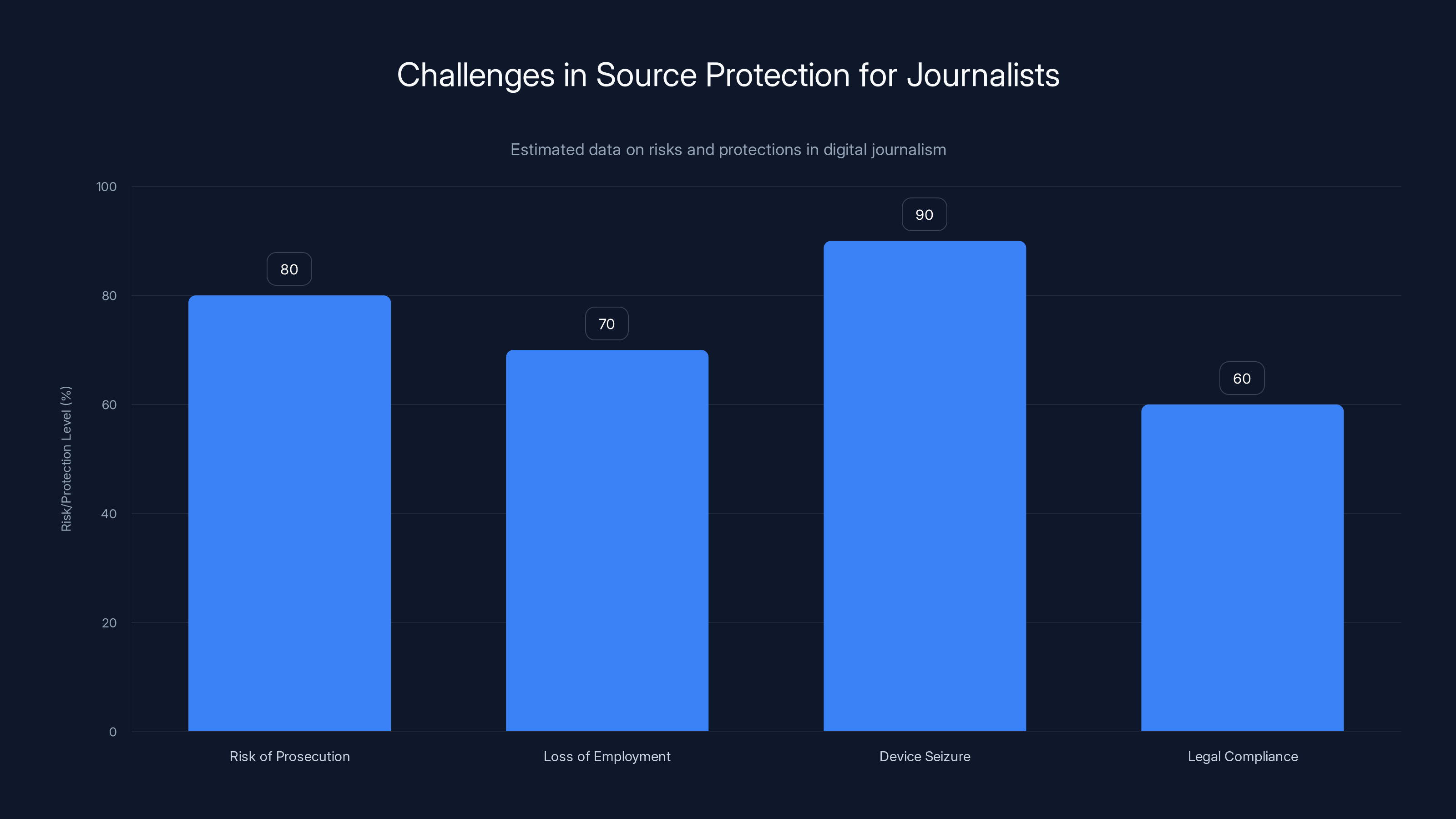

When Natanson reports on Pentagon leaks, she's working with someone inside government who's taking risks to provide information to the public. That source could face criminal prosecution, loss of employment, destruction of career, or worse. The source is trusting Natanson to keep them confidential.

From the government's perspective, Natanson isn't the criminal. The person who leaked classified documents is. But the only way to find that person is to look at Natanson's communications. So they execute a warrant on her home and seize her devices.

This puts journalists in an impossible position. They're legally required to help investigators when a warrant is presented. But helping investigators means potentially exposing sources. The journalist's preferred response is to refuse, claim reporter's privilege, and let the courts decide. But the warrant can force compliance even if the journalist argues it violates press freedom.

Lockdown Mode changes the calculus slightly. If a journalist enables Lockdown Mode on their personal device, at least that device becomes inaccessible even with a warrant. The iPhone becomes essentially private space that the government can't access even with legal authority. This is what happened in Natanson's case.

But this only works if the journalist uses the personal device and not work devices. The Post owns devices, and the Post might not have the same security posture as a personally owned device. If a journalist does reporting on a company laptop, that device might not have Lockdown Mode enabled. Once the government gets that device, the reporting is exposed.

For national security journalists specifically, this is critical. The Post's own disclosure in court filings revealed that investigators accessed Natanson's Signal account and potentially her contact list of 1,100 sources through her work MacBook. Those sources are now potentially identifiable to the government. If any of them is the actual leaker, the investigation moves forward. But even if none of them are the leaker, their names are now in an FBI database.

This is why Natanson's case matters beyond just device security. It's about the vulnerability of journalism in America. Journalists are increasingly under scrutiny. The Trump administration and previous administrations have both investigated leaks aggressively. Journalists need tools to protect sources. Lockdown Mode is one such tool, but only if used correctly and only on the right devices.

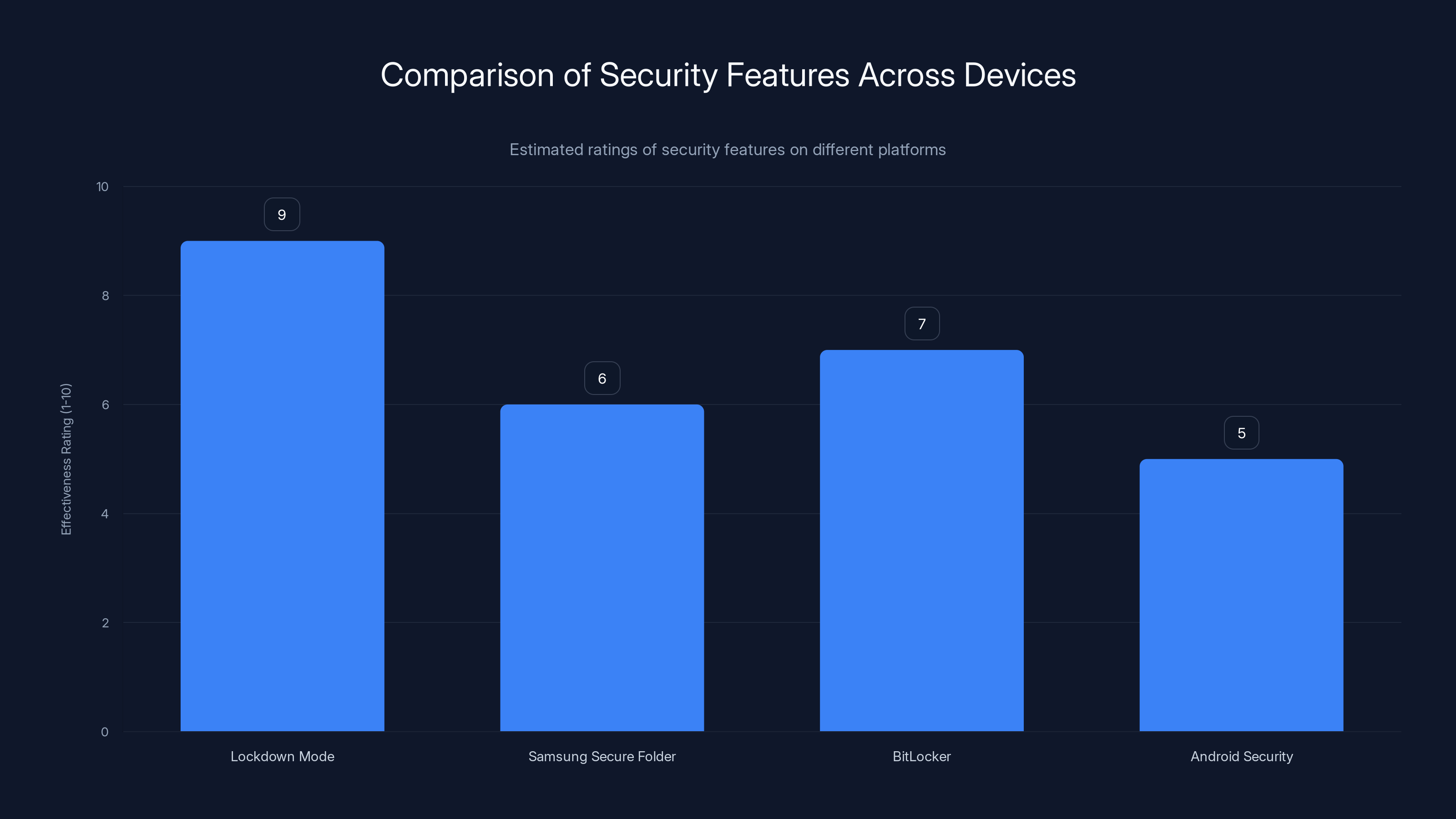

Lockdown Mode stands out with the highest security effectiveness rating due to its comprehensive approach, surpassing other features like Samsung's Secure Folder and BitLocker. (Estimated data)

The Legal Authority Behind Search Warrants: Fourth Amendment and Device Access

The search warrant executed at Natanson's home was authorized under the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. The government has the right to search when they have probable cause that a crime has been committed and they obtain a warrant from a judge.

The warrant in this case was specific. It authorized agents to search for communications related to the Pentagon leak investigation. It authorized seizure of devices that might contain those communications. And critically, it authorized the use of biometrics to unlock those devices.

This last authorization is where law and technology intersect in complex ways. The Fourth Amendment has been interpreted by courts to allow government access to electronic devices when there's a warrant. But how far does that access extend?

For passwords and encryption keys, courts have generally ruled that you can't be compelled to provide them because they exist in your mind. This is the difference between the Fifth Amendment (self-incrimination) and biometric data. Your password is protected knowledge. Your fingerprint is not.

But there's a practical question: what if you forget your password? What if you don't use biometrics and the government can't unlock your device? Can they compel you to unlock it through other means?

This is where Lockdown Mode becomes legally interesting. The FBI couldn't compel Natanson to disclose her iPhone's password because the Fifth Amendment protects that. But they also couldn't use biometric unlock because the device was in Lockdown Mode. So they hit a wall. The warrant authorized access, but they had no legal mechanism to actually obtain it.

For the MacBook, they had biometric authorization, and it worked. Natanson allegedly said she doesn't use biometrics, but the warrant authorized the attempt anyway.

The legal principle here is developing in real time. As security features become more sophisticated, law enforcement needs to adapt their strategies. Warrants now need to specifically authorize biometric unlocking. Search strategies need to account for devices that might have multiple layers of protection.

One unresolved question: if the iPhone had also been protected by biometric unlock with Lockdown Mode enabled, could the FBI force Natanson to unlock it? Legal scholarship suggests yes, under current law. You can be compelled to submit to a fingerprint. But Lockdown Mode might provide additional protection even if the fingerprint succeeds. That's untested.

Press Freedom Implications: The Chilling Effect on Journalism

The Natanson case sits at a critical intersection: press freedom and national security. These values sometimes conflict, and when they do, the resolution is usually complex and uncomfortable.

When the FBI seizes a journalist's devices and extracts communications with sources, it has consequences for journalism itself. Sources become less willing to communicate. They know the government might obtain those communications with a warrant. If they're already taking a risk by leaking classified information, adding the risk that their identity will be revealed to federal investigators makes leaking less attractive.

This is the chilling effect. It's well-documented in journalism and constitutional law. When journalists and sources fear government surveillance, journalism suffers. Important information that should be public stays hidden because sources won't provide it.

Lockdown Mode potentially changes this dynamic. If a journalist uses Lockdown Mode on their personal device, at least some of their communications are protected even from government warrants. This gives sources slightly more confidence that their communications will stay private.

But this only works if journalists actually use Lockdown Mode. And they need to use it consistently, on all devices, for all communications. In practice, that's not always feasible. Journalists work on company laptops. They check email on multiple phones. They sync data across devices. A complete Lockdown Mode strategy would require discipline that even security-conscious people don't always maintain.

Additionally, Lockdown Mode restricts functionality. FaceTime calls from new contacts are blocked. Message attachments don't work. Some apps misbehave. For a journalist who needs to receive tips from sources, these restrictions could be frustrating. A source who wants to send a photo, video, or document might not be able to if the journalist is using Lockdown Mode.

So there's a real tradeoff: security versus accessibility. The more secure your device, the less able you are to receive certain types of information. For journalism, that's a meaningful constraint.

The broader press freedom question is whether the government should be able to access a journalist's devices with a warrant at all. Some countries and some legal systems recognize strong journalist privilege. The United States has limited journalist privilege, and it's often overridden by criminal investigations.

The Natanson case didn't result in charges against Natanson herself. She's not accused of a crime. But the government wanted her device data to investigate someone else's crime. The question of whether that's justified is a matter of legitimate debate. Strong press freedom advocates would say the government shouldn't be able to search a journalist's devices even with a warrant, because it inevitably chills journalism. Law enforcement would say they need access because crime investigation sometimes requires it.

Lockdown Mode doesn't resolve this debate. But it does give journalists one tool to protect themselves: the ability to make their devices essentially inaccessible even to government investigators with warrants. Whether that's good policy is a question society will be debating for years.

Journalists face significant risks in protecting sources, with high potential for device seizure and prosecution. Lockdown Mode offers some protection. (Estimated data)

Biometric Security: Why Fingerprints Failed and What That Teaches Us

One of the most revealing details in the FBI's declaration is how quickly Natanson's fingerprint unlocked the MacBook Pro. The agent applied her index finger to the reader, and the device unlocked immediately. No error messages. No attempts. Just instant access.

This reveals something important about biometric security: it's not actually that secure once your biometric is available. Your fingerprint isn't secret. You leave fingerprints on everything you touch. Your face is visible to anyone who sees you. Your voice can be recorded. These are biological identifiers, not secrets.

Biometric security works by saying: if you prove you're you (through your biometric), you should have access. It's convenient. You don't need to remember a password. You can't forget your fingerprint. It works reasonably well for personal devices where you're trying to prevent strangers from accessing your phone if you lose it.

But biometric security fails dramatically when someone with legal authority forces you to use your biometric against your will. A police officer can't force you to reveal your password (Fifth Amendment). But they can force you to let them scan your fingerprint. That's been the legal distinction for years.

The Natanson case proves why this distinction is problematic. The fingerprint access was complete and instantaneous. She couldn't have refused without facing potential legal consequences for obstructing a search warrant. So biometric security became essentially no security against government investigation.

This doesn't mean biometric security is useless. It means biometric security is useful only against non-authorized threats. If someone tries to unlock your phone when you don't want them to, Face ID might stop them. But if a government agent with a warrant tells you to unlock your phone biometrically, biometrics provide no protection.

For users trying to secure their devices against multiple threats (thieves, hackers, family members, and government investigators), the calculus is complicated. Biometrics help with the first three. They don't help with the last one if the government has a warrant.

This is why Lockdown Mode is effective where biometrics alone aren't. Lockdown Mode can't be bypassed by any single factor, including biometrics. It works by restricting functionality so thoroughly that even if you get in the device, there's less to extract. The data is harder to reach because the attack surface is reduced.

What Lockdown Mode Protects (And What It Doesn't)

It's important to be clear about what Lockdown Mode actually does and doesn't do. It's not a complete solution to all security problems. It's a specific tool designed for a specific threat: sophisticated mercenary spyware.

Lockdown Mode reduces the attack surface, makes exploitation harder, and restricts features that are frequently used as attack vectors. But it doesn't encrypt your data differently. It doesn't change the encryption algorithm. It doesn't make your password stronger. What it does is limit ways that an attacker can get to the encryption, and limit what they can do if they somehow do get to the data.

For example, message attachments are blocked in Lockdown Mode. That's because message attachments are often how spyware gets installed. Someone sends you what looks like an innocent photo, but it's actually malicious code designed to exploit a vulnerability. Lockdown Mode prevents that avenue of attack.

But if you receive a message from someone you haven't contacted in 30 days, Lockdown Mode blocks the FaceTime call. This is because some spyware used FaceTime calls as an attack vector. By blocking these calls, Lockdown Mode reduces exposure to that specific attack.

None of this matters if the government has a warrant and physical access to your device. The government's threat model is different from a sophisticated attacker's model. The government has legal authority. They can compel you to help them access your device. Lockdown Mode protects against mercenary spyware. It doesn't protect against legal search warrants.

The Natanson case proves this. Lockdown Mode kept the FBI out of her iPhone. But they got into her MacBook, and they got the information they wanted. Lockdown Mode didn't ultimately protect her source information from government access. It just made the government work slightly harder by forcing them to access a different device.

For privacy-conscious users, the lesson is clear: Lockdown Mode is useful, but it's not a complete solution. You need multiple layers of security. You need to secure all your devices, not just one. You need good password practices. You need to think about the different threats you face and plan accordingly.

For security researchers and privacy advocates, the Natanson case validates that Lockdown Mode works as advertised. The FBI's best forensics team couldn't crack it. That's worth knowing, even if it doesn't solve every security problem.

The Pentagon Leak Investigation: Why This Case Matters Beyond Device Security

The background to the Natanson case is important because it contextualizes why the FBI wanted access so badly. Someone at the Pentagon leaked classified information to the public. That's a serious crime. It could compromise military operations, endanger sources, or harm national security.

The leak wasn't Natanson's doing. She didn't steal the documents. She reported on them, which is her job as a journalist. But the government wanted to know where the documents came from. The leak could be from a low-level analyst, a high-ranking official, or anyone in between.

This is the government's legitimate law enforcement interest. They need to find who's leaking and stop them. From that perspective, getting access to Natanson's communications is reasonable. She might know the source. Even if she doesn't, her communications might reveal the source's identity or show who was talking to her.

From a journalist's perspective, the situation is different. Natanson's job is to report news, not help the government identify sources. Even if she knows who the source is, she has a professional and ethical obligation to keep them confidential. Providing source information to the government, even under legal compulsion, violates the basic social contract between journalists and their sources.

But there's a third perspective: the source's perspective. The source leaked the documents for reasons they believed justified it. Maybe they thought the public needed to know information that was being kept secret. Maybe they thought government action was illegal or unethical. Maybe they wanted to expose waste or misconduct. Whatever their motivation, they took a significant risk.

If the government can access a journalist's communications and identify the source, the source faces serious consequences: criminal prosecution, imprisonment, destruction of career, financial ruin. This is why sources insist on confidentiality. Without it, they wouldn't leak anything.

The Natanson case shows that Lockdown Mode can protect sources at least partially. If the iPhone had been the only device, the FBI would have zero information about sources. But because she also used a less secure MacBook, they got access anyway.

For the Pentagon leak investigation specifically, the accessibility of Natanson's work MacBook Pro meant the government could move forward. They saw communications, identified potential sources, and could pursue the investigation. Lockdown Mode on her personal iPhone became irrelevant.

This teaches an important lesson for journalists in national security reporting: consistency matters. One secure device doesn't protect you if another device with the same information is less secure. The government will take the path of least resistance. If that path leads to your unencrypted work device, your protection on your personal device doesn't matter.

Comparing Lockdown Mode to Other Security Features: How It Stands Alone

Security features on phones have evolved significantly over the past decade. Most smartphones now have encryption, biometric unlock, and various levels of app sandboxing. But Lockdown Mode is uniquely restrictive.

Samsung phones have secure folders, which allow you to create a separate encrypted space on your device. But this isn't the same as Lockdown Mode. A secure folder restricts access to specific apps or data, but the rest of the phone functions normally. Vulnerabilities in the main operating system could still be exploited.

Windows PCs have BitLocker encryption, which encrypts the hard drive. But encryption at rest (when the device is off) is different from protection while the device is powered on. Once the device is unlocked, encryption is less relevant.

Google's Android has various security features, including sandboxing, but it doesn't have an equivalent to Lockdown Mode. Android allows more flexibility, which is part of its design philosophy, but it also means the device is more exposed to potential attacks.

Lockdown Mode is different because it's not just one feature. It's a comprehensive re-architecture of how the device operates. It limits multiple attack vectors simultaneously. It's not just encryption or just sandboxing or just biometric security. It's all of these together, plus severe functional restrictions.

The cost of this comprehensive security is functionality. Apps don't work the same way. Features are unavailable. The user experience is degraded. This is why Lockdown Mode is designed only for people who need it desperately. For most users, the restrictions would be unacceptable.

But for journalists, activists, dissidents, and others at high risk of targeted surveillance, the restrictions are worth accepting. Lockdown Mode proved in the Natanson case that it works. The FBI, with all their resources and tools, couldn't access the iPhone. That's validation that a comprehensive, restrictive security posture actually delivers on its promise.

How Law Enforcement Will Adapt: Future Implications of Lockdown Mode's Effectiveness

The Natanson case reveals something uncomfortable for law enforcement: their tools have limits. For years, law enforcement has become increasingly sophisticated at accessing devices. New exploits are discovered, purchased, and deployed. Tech companies patch them, but new ones emerge.

But Lockdown Mode appears to be ahead of the curve. It's not just about patching known vulnerabilities. It's about reducing the attack surface so much that there are fewer vulnerabilities to exploit.

How will law enforcement adapt? They'll probably do what they did in the Natanson case: find another device. If your iPhone is Fort Knox but your MacBook is ordinary, investigators will get into your MacBook. If all your devices are secure, they'll try to get information from your cloud backup, your email provider, or your contacts.

Law enforcement might also lobby for backdoors. For years, the FBI and other agencies have argued that strong encryption, and security features like Lockdown Mode, should have backdoors for law enforcement. Apple consistently refuses. If Lockdown Mode becomes widespread among journalists and activists, the political pressure for backdoors might increase.

Another possibility is legal adaptation. As Lockdown Mode becomes more common, courts might issue warrants that specifically account for it. They might authorize broader searches of other devices to compensate. They might require companies to create new tools or provide assistance that circumvents security features.

Finally, law enforcement might focus more on human intelligence. Instead of trying to crack devices, they might pay informants, conduct surveillance, or develop sources within organizations. This is actually common in national security investigations. Finding who leaked might not require accessing a journalist's device at all. It might just require good old-fashioned detective work.

The bigger implication is that technology and law enforcement will continue to dance this dance. Technology companies push for better security. Law enforcement pushes back. Legislation gets proposed. Court cases set precedents. And users find themselves caught in the middle, trying to maintain privacy while complying with legal authority.

Lessons for Journalists, Activists, and Privacy-Conscious Users

The Natanson case provides several clear lessons for people trying to protect their communications and sources from government access.

First, use Lockdown Mode on personal devices. If you're doing sensitive work, especially journalism or activism, enable Lockdown Mode on your iPhone. Yes, you'll lose some functionality. But you gain real protection against forensic tools. The FBI couldn't access Natanson's iPhone. Your personal device can be similarly protected.

Second, treat work devices differently. Don't use work devices for sensitive communications if you can avoid it. If you must use work devices, understand that your employer might have access to them, and law enforcement with a warrant almost certainly can. Don't assume corporate security is the same as personal security.

Third, use encrypted messaging for sensitive communications. Signal is industry standard for journalists. It's encrypted end-to-end, meaning messages are encrypted on your device and decrypted only on the recipient's device. Even if someone accesses your device, old messages might be protected (depending on Signal's backup settings).

Fourth, understand the limits of any single security feature. Lockdown Mode protected Natanson's iPhone, but the FBI accessed her information through another device. Security is a system, not a single feature. You need strong passwords, encrypted messaging, multiple secure devices, and good operational security practices.

Fifth, recognize that you might not have a choice. Natanson had a warrant executed at her home. She was compelled to help unlock devices. You can't always prevent law enforcement access, especially if you have a warrant against you. But you can make it harder, slower, and more legally contentious.

Finally, understand the press freedom implications. For journalists specifically, the stakes are higher. Sources need to know that their communications will be protected. Using strong security isn't just personal preference. It's a professional responsibility to sources who risk everything to provide information.

The Broader Security Landscape: Where Lockdown Mode Fits in 2025

In 2025, digital security is more important and more complex than ever. Geopolitical tensions have increased. Disinformation is everywhere. Cyber espionage is routine. Corporate data theft is common. Government surveillance is real.

Against this backdrop, Lockdown Mode is one tool among many. It's not a universal solution. It doesn't solve online phishing (social engineering remains one of the most effective attack vectors). It doesn't protect you if you voluntarily give someone your password. It doesn't protect your email account if someone gets your password through other means.

But what Lockdown Mode does do is create a fortress. If your device is in Lockdown Mode, and someone wants to access your data, they have very few options. They can't exploit a software vulnerability easily (the attack surface is reduced). They can't install malware through message attachments (they're blocked). They can't exploit browser technologies (restricted). They can't social engineer you into clicking a link that installs spyware (fewer attack vectors exist).

What they can do is force you to unlock the device with biometrics (if you have a warrant). Or they can force you to reveal your password (though Fifth Amendment protections might apply). Or they can get information from your cloud backup, your email provider, or other sources.

But the barrier to entry is high. For casual adversaries, casual hackers, and even sophisticated targeted attackers, Lockdown Mode provides meaningful protection. For government investigators with a warrant, it's harder but not impossible (they just have to try a different approach).

In the broader security landscape, Lockdown Mode represents a shift in how security is conceptualized. It's not just about strong passwords and encryption anymore. It's about architectural changes to the device itself. It's about restricting features to reduce risk. It's about accepting that convenience and security are often in tension, and choosing security.

Other companies will likely develop similar features. Google might introduce something similar on Android. Microsoft might enhance Windows security in comparable ways. The industry is moving toward the idea that comprehensive security requires comprehensive restrictions.

For users, the landscape is becoming segmented. There are high-security devices for people who need them, ordinary devices for most people, and increasingly, a middle ground where more security features become standard.

The Natanson case accelerates this segmentation. Now journalists, activists, and security researchers know that Lockdown Mode works. That knowledge will drive adoption. And as adoption increases, other features will follow. Device security in the coming years will probably look quite different from how it looks today.

FAQ

What is Lockdown Mode and who should use it?

Lockdown Mode is a comprehensive security feature in iOS, iPadOS, and macOS that restricts functionality to reduce the device's vulnerability to sophisticated targeted spyware. It's designed specifically for people who, because of who they are or what they do, might be targeted by highly sophisticated cyber attacks. This includes journalists, activists, political figures, human rights defenders, and security researchers. Most ordinary users don't need it because it significantly restricts convenience (blocking message attachments, limiting FaceTime, restricting website technologies).

How did the FBI access Hannah Natanson's communications if her iPhone was protected?

The FBI couldn't access the iPhone because it was protected by Lockdown Mode. However, they accessed her MacBook Pro using her biometric fingerprint, which the search warrant authorized. The MacBook contained Signal messages and a contact list of over 1,100 government sources. This demonstrates a critical security principle: one secure device doesn't protect you if you have multiple devices with the same sensitive information and only some of them are secure.

Why can law enforcement use biometrics to unlock devices but not passwords?

Under current U.S. law, the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination applies differently to passwords and biometrics. A password exists in your mind and is protected as knowledge you can't be compelled to reveal. Biometric data (fingerprints, facial features) is a physical characteristic, similar to a blood sample or DNA swab. Courts have ruled that you can be compelled to provide biometrics just as you can be compelled to provide physical evidence. This distinction is controversial but currently the law in most jurisdictions.

Does Lockdown Mode protect against all types of threats?

Lockdown Mode is specifically designed to protect against sophisticated mercenary spyware like Pegasus. It's less effective against other threats like phishing attacks, social engineering, poor password practices, or weak cloud backups. It also doesn't protect against legal searches with warrants (though it can make such searches more difficult). Lockdown Mode is one layer of a comprehensive security strategy, not a complete solution.

How does Apple's Lockdown Mode compare to other security features like biometric unlocking or encryption?

Lockdown Mode is more comprehensive than individual security features. Biometric unlocking is convenient but can be bypassed if someone forces you to use your biometric with a warrant. Encryption protects data from external attackers but not from someone who unlocks your device. Lockdown Mode combines multiple protective approaches simultaneously (restricted attack surface, limited message attachments, browser limitations, restricted app access). It works best when combined with strong passwords and encrypted messaging.

What are the practical limitations of using Lockdown Mode as a journalist or activist?

Lockdown Mode significantly reduces device functionality. FaceTime calls from new contacts are blocked, message attachments won't download, some apps misbehave, and web browsing is restricted. For journalists, this creates obstacles to receiving tips and information from sources. Sources might want to send documents, photos, or videos, but Lockdown Mode blocks these. This creates a tradeoff between security and accessibility that each user must evaluate based on their threat model.

Can Lockdown Mode prevent law enforcement access to devices?

Lockdown Mode prevents law enforcement from using standard forensic tools to extract data (as demonstrated by the FBI's inability to access Natanson's iPhone). However, law enforcement with a warrant can still compel you to unlock a device using biometrics or potentially your password. The key difference is that Lockdown Mode removes the path of least resistance. Investigators must either force biometric unlocking or find another device, rather than using forensic extraction tools.

What is the significance of the Natanson case for press freedom in America?

The case demonstrates both the potential and limitations of strong security for protecting sources. Lockdown Mode on Natanson's iPhone would have been completely inaccessible to the FBI, but her work MacBook Pro was not. This reveals that consistent security across all devices is necessary for real protection. For journalists specifically, it highlights the tension between national security investigations and press freedom. Sources need confidence that their communications will be protected, but government investigations sometimes require accessing those communications.

Conclusion: What the Natanson Case Means for Digital Security and Privacy

The case of Hannah Natanson and her seized devices reveals something genuinely important about digital security in 2025. For the first time in recent memory, we have concrete proof that a consumer security feature defeated the FBI's elite forensics team. That's significant. That's the kind of data point that security researchers and privacy advocates will cite for years.

But the case also reveals the limits of any single security measure. Lockdown Mode protected one device completely. But the reporter had multiple devices, and at least one of them was significantly less secure. Through that less secure device, the FBI obtained the information they wanted.

This creates practical lessons for journalists and security-conscious people: you can't secure just one device and consider yourself protected. You need comprehensive security across all your devices. You need encrypted messaging. You need good password practices. You need to think systematically about your threat model and design your security accordingly.

It also creates policy questions. Should the government have the ability to access a journalist's devices even with a warrant? Should biometric locks be bypassed while password locks aren't? Should national security investigations override press freedom protections? These are genuine policy debates, and the Natanson case will inform them.

From Apple's perspective, the case validates Lockdown Mode. The feature worked exactly as intended. It protected against forensic extraction. The FBI acknowledged they couldn't bypass it. That's exactly what Apple designed it to do. It also provides valuable real-world evidence of effectiveness, which will help Apple market Lockdown Mode to the people who need it most.

From the FBI's perspective, the case reveals the challenges of a security-conscious world. Criminals, terrorists, and bad actors increasingly use strong security tools. This makes investigation harder. The FBI will continue to push for backdoors or weaker security standards. Companies will resist. The tension will continue.

For sources and whistleblowers, the case has mixed implications. On one hand, Lockdown Mode demonstrated real protection. A device in Lockdown Mode is genuinely difficult for law enforcement to access. That's positive. On the other hand, the case also shows that one protected device might not be enough if you have other devices with the same information. The practical implication is clear: commitment to security has to be comprehensive. You can't do it halfway.

Looking forward, we'll likely see more cases like this. As Lockdown Mode and similar security features become more common, law enforcement will encounter them more frequently. Some agencies are already developing new tools and techniques to address strong security. Some are lobbying for legal changes. Some are adjusting investigation strategies to focus on weaker targets or alternative evidence sources.

The security landscape is fundamentally changing. Technology companies are building stronger protections. Law enforcement is pushing back. Users are caught in the middle, trying to balance privacy and convenience, security and accessibility.

The Natanson case is a data point in this larger story. It proves that strong security works. It also proves that strong security can be undermined by inconsistent practices across multiple devices. Most importantly, it reminds us that digital security in 2025 is not just a technical problem. It's a legal problem, a political problem, and a press freedom problem. The implications extend far beyond device forensics.

For anyone working with sensitive information, the lesson is straightforward: take security seriously. Enable Lockdown Mode. Use encrypted messaging. Secure all your devices, not just one. Understand the threats you face. Design your security strategy accordingly. And recognize that even strong security might not be unbreakable against determined law enforcement. But making access harder, slower, and more legally contentious is the whole point.

The FBI couldn't crack Hannah Natanson's iPhone. That's a win for security. But they got the information they wanted anyway, through another device. That's a reminder that comprehensive security requires thinking beyond any single device or feature. In the end, security is a system, and a system is only as strong as its weakest link.

Key Takeaways

- Apple's Lockdown Mode successfully prevented the FBI's Computer Analysis Response Team from extracting data from an iPhone, proving the security feature works against sophisticated forensics tools

- Biometric unlock authority under search warrants allowed the FBI to access a MacBook Pro, demonstrating that government agents can compel biometric authentication even when passwords are protected

- Consistent security across multiple devices is critical—protecting one device while leaving others vulnerable allows law enforcement to access sensitive information through weaker devices

- Journalists and activists benefit significantly from Lockdown Mode, but its restrictions on functionality (blocked attachments, limited FaceTime, reduced app features) create tradeoffs in usability

- The case highlights ongoing tensions between press freedom and national security investigations, with implications for source protection and the constitutional right to communicate confidentially

Related Articles

- ICE Domestic Terrorists Database: The First Amendment Crisis [2025]

- Switzerland's Data Retention Law: Privacy Crisis [2025]

- Apple Pay Unusual Activity Scam: How to Spot Fake Messages [2025]

- How DHS Uses Administrative Subpoenas to Target Critics [2025]

- France's VPN Ban for Minors: Digital Control or Privacy Destruction [2025]

- France's VPN Ban for Under-15s: What You Need to Know [2025]

![Apple's Lockdown Mode Defeats FBI: What Journalists Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-s-lockdown-mode-defeats-fbi-what-journalists-need-to-k/image-1-1770246623347.jpg)