Google Recovers Deleted Nest Videos: What This Means for Your Privacy [2025]

You delete a video. It's gone. That's what you think, anyway.

But in February 2025, investigators working the Nancy Guthrie abduction case discovered something unsettling: Google's Nest doorbell camera had captured footage of someone tampering with the camera, even though the user wasn't paying for cloud storage. The video had supposedly been deleted three hours after recording, following Google's free tier policy. Yet nine days later, authorities recovered it anyway.

This case shattered a common misconception about cloud storage and digital privacy. It revealed a gap between what companies tell users and what actually happens to data behind the scenes. More importantly, it raised hard questions about how long deleted data actually persists, who can access it, and whether consumers have any real control over their digital footprints.

If you're using any cloud-connected security camera—and millions of people are—this matters to you. The technical details are murky, but the implications are crystal clear: nothing you upload to the cloud is ever truly gone.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what you can actually do about it.

TL; DR

- Google recovered Nest footage 9 days after automatic deletion in a criminal investigation, despite the user not paying for extended storage

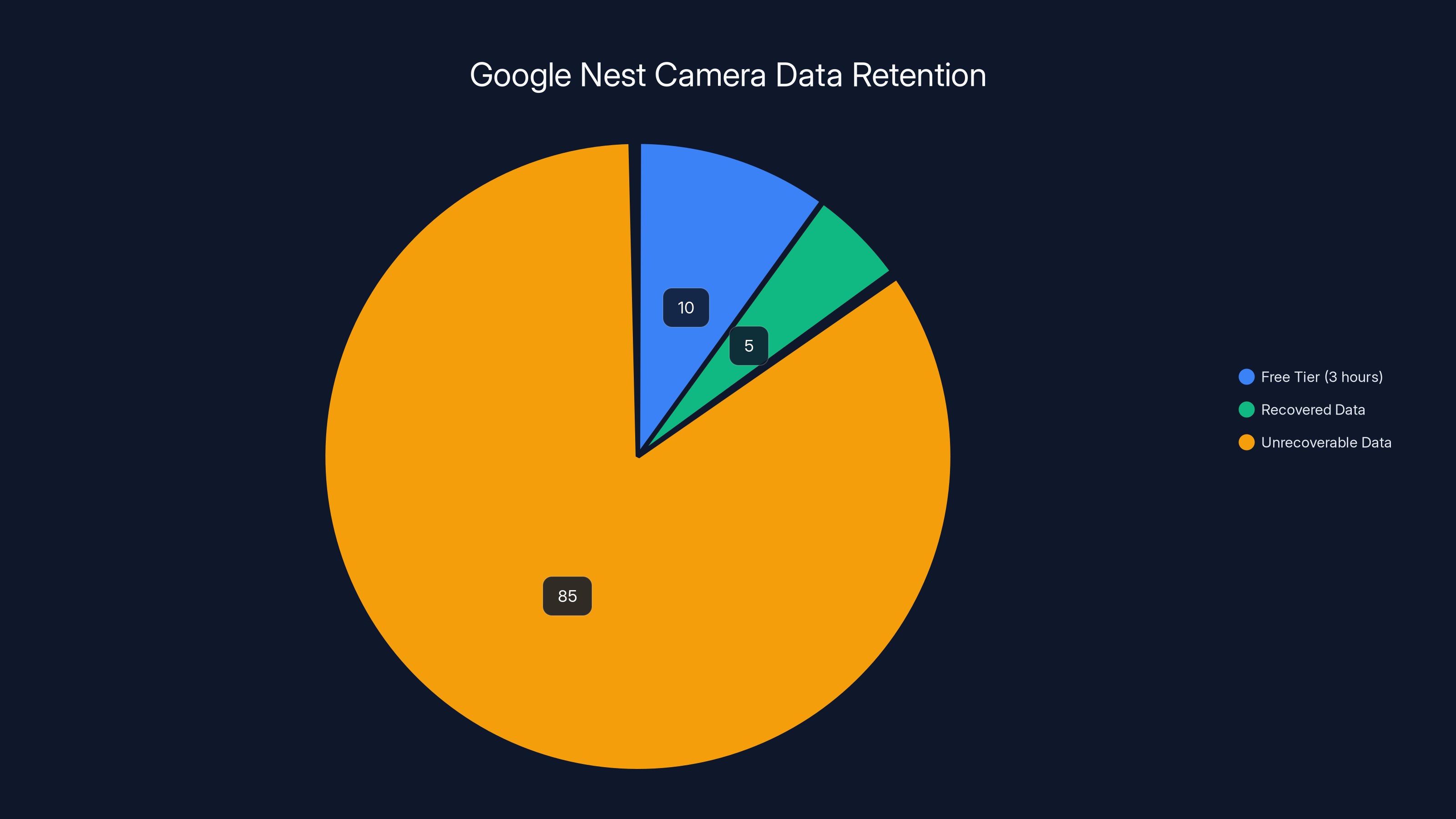

- Free Nest users get only 3 hours of cloud storage, but deleted data may persist in backend systems for much longer

- Google's data retention policy lacks transparency, and the company hasn't clarified how long deleted videos are actually stored

- The technical explanation: Videos deleted from user access don't disappear immediately from backend infrastructure; they're often compressed and gradually overwritten

- Your privacy implication: Cloud-stored footage is recoverable by Google (and authorities with access) long after you think it's deleted

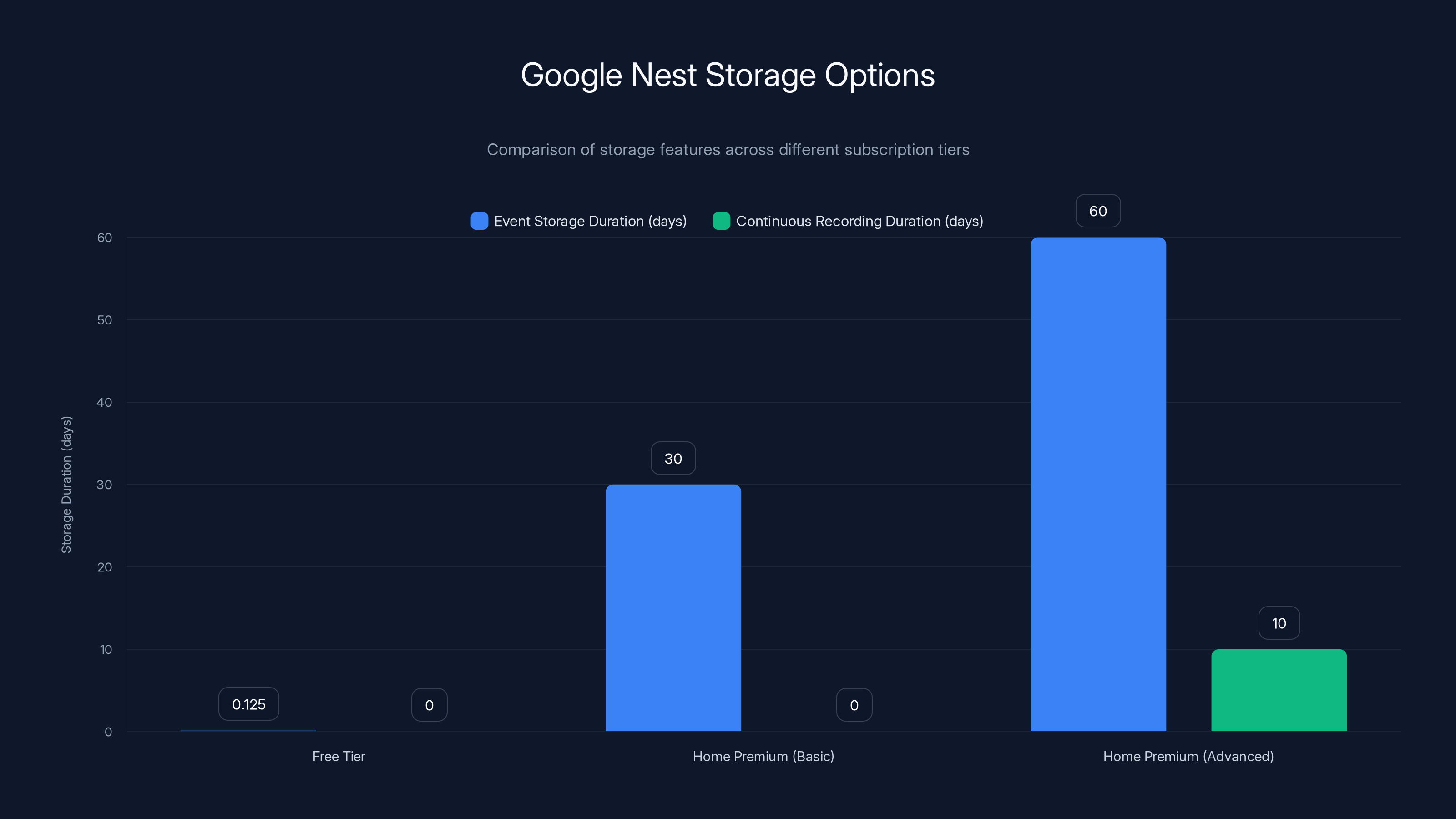

The Free Tier offers only 3 hours of event storage, while Home Premium tiers provide significantly longer durations, with the Advanced tier including 10 days of continuous recording.

What Happened in the Nancy Guthrie Case

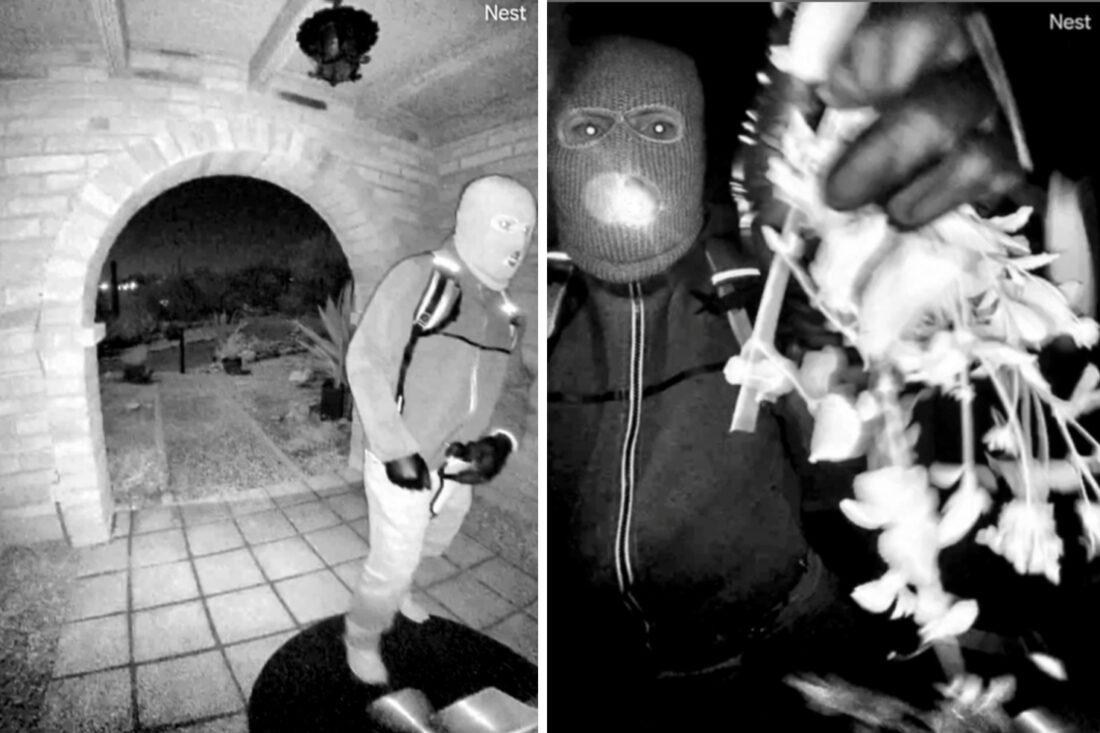

On the morning of February 1, 2025, Nancy Guthrie was abducted from her home in a high-profile case that quickly attracted national attention. Investigators initially reported a critical setback: the Nest doorbell camera at her residence hadn't captured footage of the crime because her account wasn't subscribed to any paid storage tier.

That's standard for Google's free offering. Without a subscription, Nest records "events" for just three hours. After that window closes, the footage disappears from your account permanently. No access, no recovery option, no way to upgrade and retrieve old content.

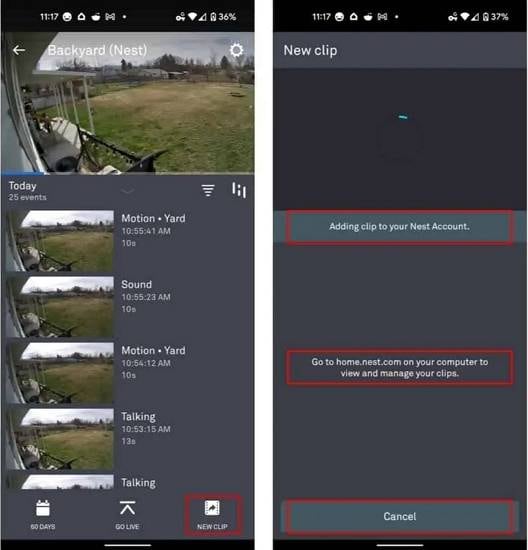

But then something unexpected happened. On February 10—nine days after the abduction—law enforcement released video showing a masked individual approaching Guthrie's door. In one clip, the person notices the doorbell camera, places their hand over the lens, and appears to pull on the mounting bracket. In a second clip, they attempt to drape a plant over the camera to obstruct the view.

Where did this footage come from? According to investigators' statements, it was "recovered from residual data located in backend systems." Those videos had been automatically deleted from Guthrie's access nine days prior, yet Google engineers had been able to retrieve them.

The investigation doesn't reveal exactly how this recovery worked or how much effort it required. Early reports suggested it took "several days" for Google to recover the data. Whether Google acted voluntarily or required a court order remains unclear, though the company's cooperation suggests it was willing to help without legal compulsion.

From an investigative perspective, this recovery was invaluable. The footage became key evidence, and releasing it to the public potentially helped identify suspects. From a privacy perspective, though, it raised uncomfortable questions that Google still hasn't adequately answered.

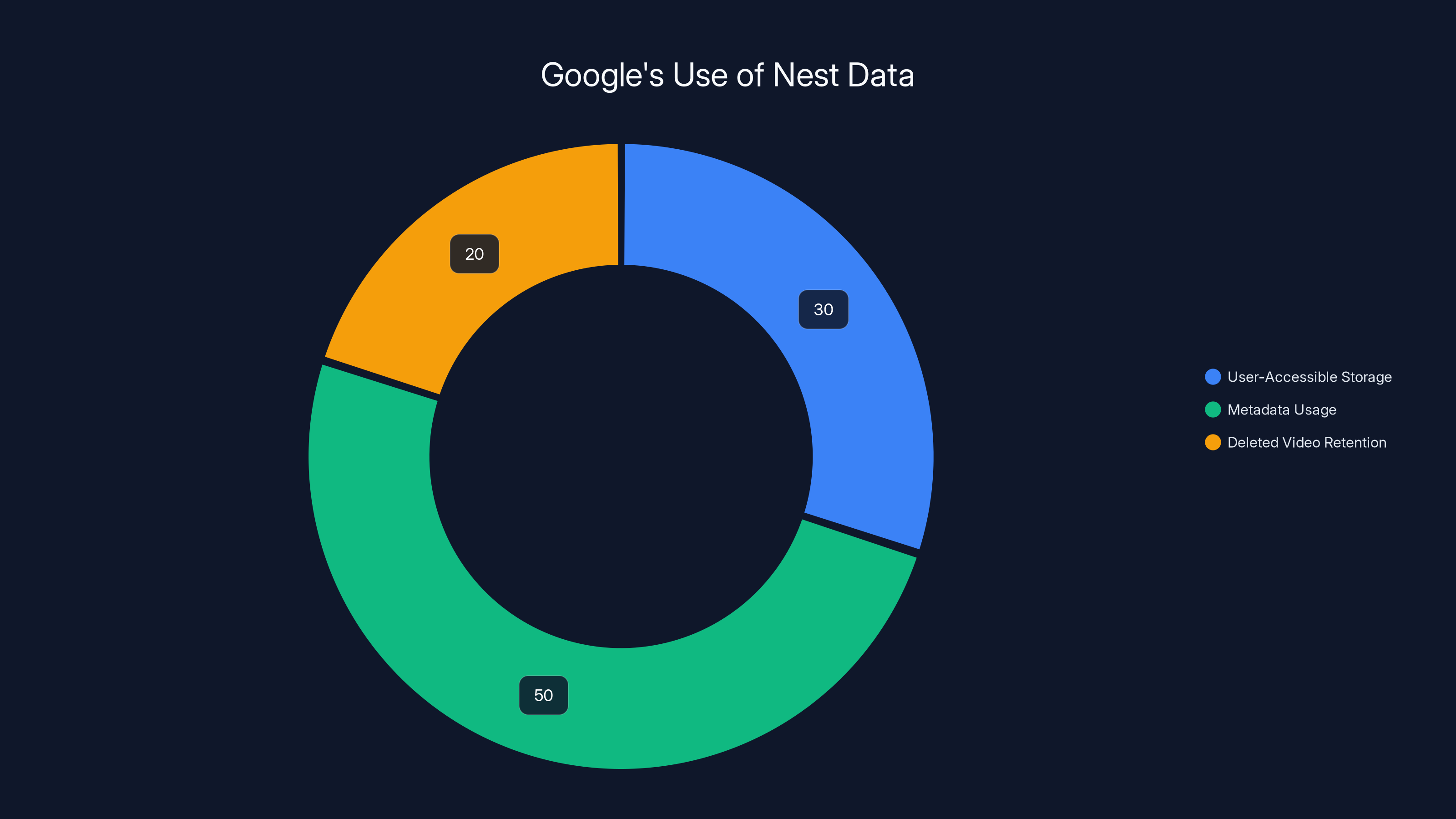

Estimated data shows that while user-accessible storage is limited, metadata is heavily utilized by Google, and deleted video retention remains a concern. Estimated data.

How Google's Nest Storage Actually Works

Understanding the technical reality requires understanding Google's current storage tiering system, which the company restructured recently around its Home Premium subscription service.

Here's what you get at each level:

Free Tier: This is what most Nest users have. Google records "events"—moments when the camera detects motion or sound—for three hours. After 180 minutes, those events are deleted from your account. You can watch live footage in real-time, but there's no archive. The three-hour window is short by design. It's meant to catch immediate issues, not provide ongoing surveillance. Many users don't realize this limitation until they need footage from hours earlier.

Home Premium (Basic): At $10 per month, you get 30 days of stored events. This means motion-triggered clips are retained for a month instead of three hours. It's better, but still event-only. You're not getting continuous 24/7 recording.

Home Premium (Advanced): At $20 per month, you upgrade to 60 days of event history plus 10 days of continuous full video. This is where you start getting actual surveillance-grade capability, but it's still limited compared to traditional security systems.

The thing is, many people assume "deleted" means the data is gone. Physically, somewhere in Google's data centers, your video file is destroyed. But that's not how cloud infrastructure works at scale.

When you're running massive data centers processing petabytes of video daily, deleting data immediately is expensive and inefficient. Instead, Google likely uses a tiered approach. When your three-hour window expires, your video becomes inaccessible to you—it's deleted from the user-facing layer. But in Google's backend infrastructure, the data probably lingers.

It might be compressed, moved to slower storage tiers, or consolidated with other data. The original file isn't immediately overwritten. Data only gets truly destroyed when the storage block it occupies is needed for new data. Until that happens, it's technically recoverable. This is standard practice in enterprise-grade storage systems, not something unique to Google.

The Guthrie case suggests Google's residual data might persist far longer than the three-hour user window. Whether it's days, weeks, or months isn't public information. Google hasn't disclosed this. When we asked, representatives didn't address the substance of the question.

The Technical Reality Behind Data Deletion

This is where the story gets less about consumer privacy and more about how data actually works at planetary scale.

When you delete a file on your laptop, it's not truly gone either. The operating system marks the disk space as "available" and removes the filename from the directory, but the file's actual data persists until that space is overwritten by something else. Experienced data recovery specialists know this. They can often resurrect deleted files from consumer devices months or years later, even after the deletion seems permanent.

Cloud storage works on the same principle, just with more infrastructure complexity.

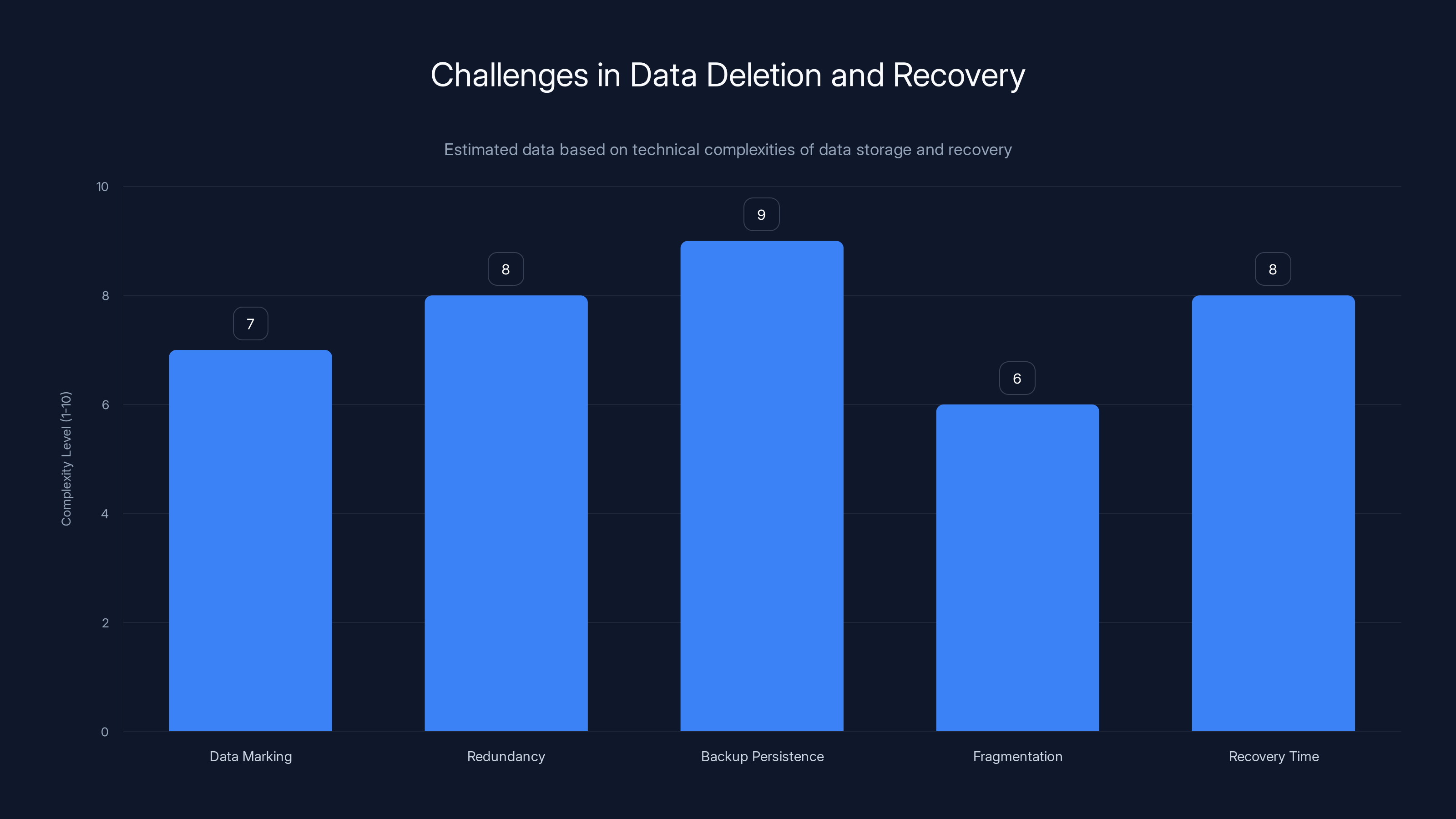

Google's data centers use massive storage clusters—think thousands of hard drives or solid-state drives networked together. These clusters employ striping, redundancy, and error correction. The RAID protocols that protect your data also make it harder to delete completely. If your video is stored across multiple physical drives for redundancy (which it almost certainly is), you can't just delete one copy and call it done.

Moreover, Google likely maintains backup copies. Enterprise data storage requires redundancy for disaster recovery. If Google loses a data center to fire or hardware failure, it needs to restore customer data from backups. Those backups probably persist longer than the original data.

There's also the question of data fragmentation. When files are deleted and new data is written, fragmentation occurs. Forensic recovery tools can reassemble deleted data even after it's been partially overwritten. Google's engineers, with direct access to the storage infrastructure, would have tools that make this recovery trivial.

Some reports about the Guthrie case mentioned it took "several days" to recover the data. That timeline makes sense. Even with direct access, finding the right data in massive backend systems takes time. Engineers need to identify which storage clusters contain footage from the relevant time window, extract that data, validate it, and prepare it for investigators. If Google's deletion process adds complications—maybe the data is compressed, encrypted, or stored in an unusual location—recovery takes longer.

But here's the critical point: none of this recovery was technically difficult for Google. The company didn't need to crack encryption or perform sophisticated forensics. It simply accessed its own backend systems and retrieved data that was still there.

The real questions are about policy and ethics. Does Google proactively delete data after a certain period? Probably. How long does it keep residual data? Unknown. Under what circumstances will Google cooperate with law enforcement? The Guthrie case suggests willingly, but there's no clear standard.

Data deletion involves multiple challenges including redundancy and backup persistence, making complete data removal complex. Estimated data.

Google's Stated Privacy Policies and the Reality Gap

This is where things get frustrating for consumers. Google's public statements about Nest storage don't directly address the scenario that occurred in the Guthrie case.

When users sign up for Nest, they see documentation that says free storage is "three hours of event history." That's technically true for user-accessible storage. But nowhere does Google explain what happens to that data afterward. The public-facing policy creates the impression that the data is gone, period.

Google's privacy documentation is similarly vague on data retention for deleted videos. The company states it doesn't use personal videos from Nest to train AI models, which is reassuring. But it does use metadata: "We may use your inputs, including prompts and feedback, usage, and outputs from interactions with AI features to further research, tune, and train Google's generative models."

Translated to plain English: Google isn't using your actual video to train Gemini or other AI. But it's using everything else. Your interaction patterns, the time of day you check footage, how you interact with the AI-powered features of the Nest app—all of that feeds into Google's model training.

The irony is almost painful. If Google were actively training AI models on video data, there'd be a business incentive to keep deleted videos around. But Google says it doesn't do that. So theoretically, deleted footage just costs the company money to store. Yet the Guthrie case suggests Google stores it anyway.

Why? The most charitable explanation is that Google's data deletion architecture is genuinely complex. The company probably has compliance standards that require eventual destruction of user data, but the actual mechanics of purging it completely from distributed systems is harder than users realize. Data gets backed up, replicated, compressed, and moved to cheaper storage tiers. By the time all those copies are finally destroyed, months or years might have passed.

The less charitable explanation is that Google keeps deleted data because it can, and because law enforcement cooperation is a feature, not a bug. The company benefits from being known as helpful to investigators. It strengthens relationships with government agencies. It also demonstrates to users that Nest is "secure"—after all, if law enforcement can recover deleted footage, so can you if needed.

Except you can't. That's the asymmetry. Google employees with backend access and law enforcement with legal authority can retrieve your deleted data. You, the account holder, cannot.

When we asked Google directly about the circumstances under which deleted videos might be recovered, representatives didn't respond. That silence is telling. If Google's data deletion process were transparent and user-friendly, the company would explain it proudly. The fact that it's unclear suggests Google itself isn't entirely confident in how to defend the current system.

Why This Matters Beyond Criminal Investigations

The Guthrie case is compelling, but it's easy to dismiss as an edge case: of course law enforcement should be able to recover deleted evidence in a serious crime. That's reasonable. But the implications extend far beyond this one investigation.

Consider a different scenario. You're in a contentious divorce. Your ex-spouse's lawyer subpoenas footage from your Nest camera, hoping to find evidence that contradicts your version of events. Or you're a political activist and authorities want to see who visited your home. Or you're involved in a dispute with a neighbor, and their lawyer demands camera footage from your property, arguing it's relevant to a civil case.

In all these scenarios, the fact that Google can retrieve deleted footage becomes a tool for other people to use against you. You thought you deleted the video. The deletion was intentional. But the data persists, and someone with legal leverage can access it.

This also creates a precedent. Once law enforcement knows Google will cooperate in serious cases, they'll ask more often. They'll broaden what counts as serious. A property crime becomes serious enough to request data recovery. A civil dispute escalates when lawyers realize they can request deleted footage. The circle expands.

There's also a psychological dimension. Right now, if you know your video is stored only for three hours, you might feel okay deleting it. You believe it's truly gone. But if you knew that Google retains deletable footage for months in backend systems, you might behave differently. You might be more cautious about what you record. You might not set up a doorbell camera at all.

Companies benefit from the perception of deletion even when deletion isn't real. Nest customers feel like they're using a privacy-respecting service because they know deletion is automatic and user data isn't used for AI training. But the underlying reality is more complicated. Google's infrastructure isn't designed for genuine user privacy; it's designed for operational efficiency and compliance with law enforcement requests.

Neither of those goals is inherently evil, but they're not the same as actually protecting user privacy.

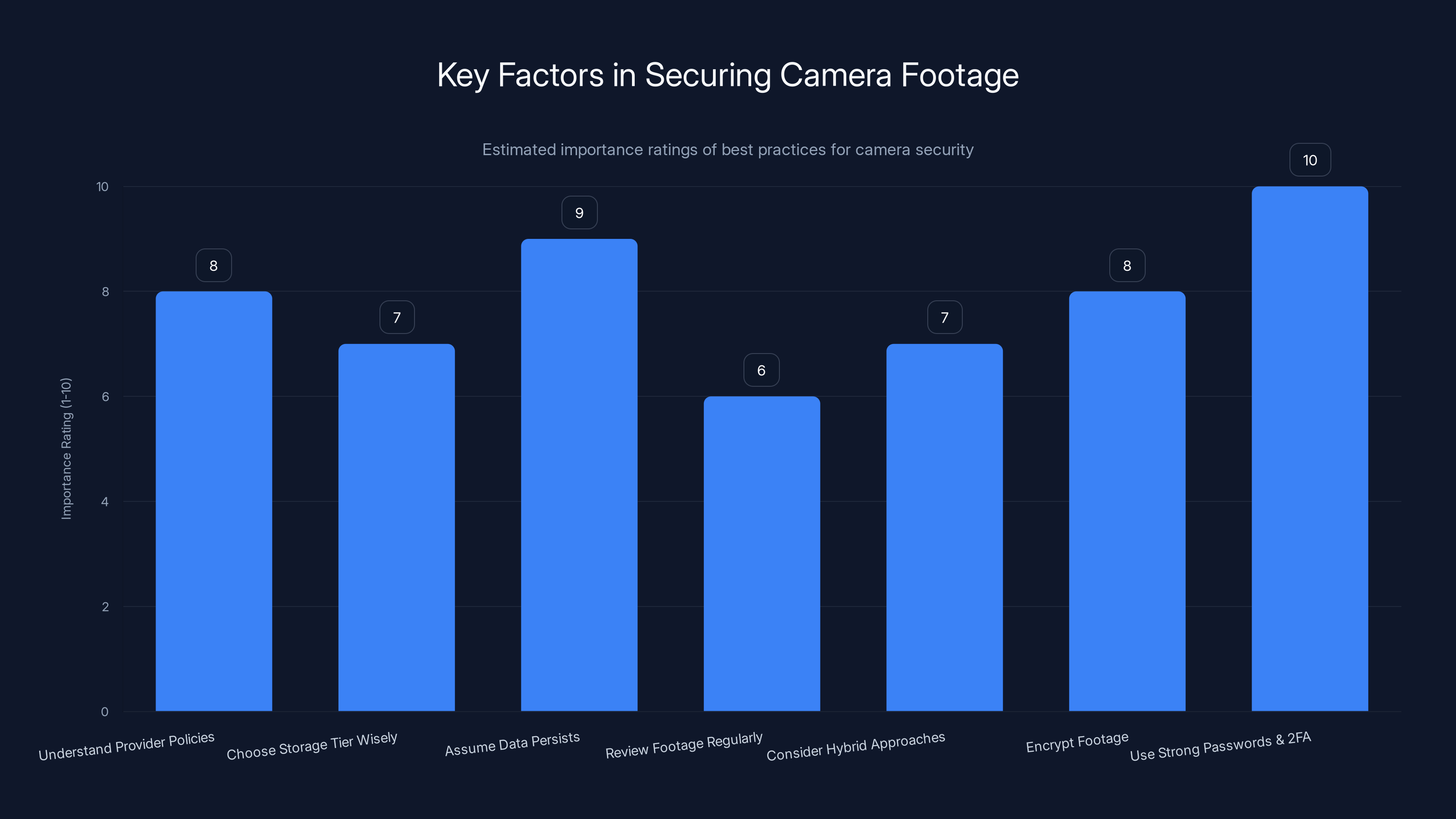

Using strong passwords and two-factor authentication (2FA) is rated as the most important practice for securing camera footage, followed by assuming data persists and understanding provider policies. Estimated data.

How Data Backups and Redundancy Create Persistence

To truly understand why deleted data sticks around, you need to grasp how enterprise storage is architected.

Google doesn't operate a single data center. It has dozens globally. Footage from Guthrie's doorbell likely exists in at least three physical locations automatically. That's standard redundancy: if one site fails, your data isn't lost.

But redundancy creates a deletion problem. When you delete a file, you need to delete it from all three locations. If those locations are in different geographic regions and managed by different systems, coordinating deletion is complex. There might be eventual consistency delays. Data might be replicated in transit when deletion commands are issued, creating temporary copies. Backup systems might have already backed up the pre-deletion version.

Add to this the question of how Google handles data writes. Most databases use write-ahead logging. Data is written to a log first, then to permanent storage. This creates temporary copies. If your video file gets deleted, the log entry might persist for a while. It's not the actual video anymore, but it's metadata that could lead to recovery.

Google also almost certainly uses object storage systems like its own Google Cloud Storage. These systems are designed for massive scale and immutability. Adding data is easy. Deleting data is hard because the system prioritizes consistency and durability over fast deletion. There are lifecycle policies that can automatically delete old objects, but those policies typically have delays. An object might be marked for deletion and then actually removed only after 30 days, allowing recovery in the interim.

Finally, there's the practical question of who manages deletion. If Nest is a separate product from Google Cloud, there might be handoffs between teams. Nest might tell Google Cloud to delete footage, but Cloud has its own deletion schedules and policies. The request queues up. Days or weeks pass before execution.

All of this happens transparently to users. You think you delete a video; Nest confirms the deletion instantly. But behind that confirmation, a cascade of distributed systems needs to coordinate. Perfect immediate deletion is expensive and slow. Approximate deletion with eventual consistency is cheaper and faster. So that's what companies do.

The Guthrie case simply exposed this normal operation. When authorities asked Google to retrieve deleted data, the company looked in the places where residual copies naturally accumulate. They found it.

Comparing Nest to Alternative Security Solutions

If cloud storage concerns you, what are your alternatives?

Local Storage Options: Traditional DVR systems record directly to hard drives in your home. The footage never touches the internet. This is genuinely more private in one sense—no company has access to your data. But it's less private in another sense: thieves can steal the DVR and destroy evidence, exactly as happened in the Guthrie case. The perpetrators destroyed the camera itself, but if there had been a local DVR, they could have smashed that too.

NAS-Based Systems: Network-attached storage boxes let you record security camera footage to your home network. Companies like Synology and QNAP make NAS devices that support security camera integrations. You maintain full control of the data. It never goes to the cloud. But you're responsible for backups, security patches, and making sure the system is actually running. Most people don't maintain this adequately.

Hybrid Approaches: Some newer systems offer local buffering with optional cloud backup. The camera records locally, and you can optionally push clips to cloud storage. This gives you the best of both worlds, but it's more expensive and complex to set up.

Privacy-Focused Cloud Services: There are smaller companies offering encrypted cloud storage specifically for security footage. Companies like Wyze and Eufy position themselves as privacy-conscious alternatives to Google and Amazon. But they're smaller, and their long-term data retention policies are often equally vague.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: most security camera users choose cloud solutions because they're convenient. You don't need to manage hardware, set up backups, or maintain systems. It just works. The tradeoff is that a corporation has access to your footage, and that footage might persist longer than you think.

The Guthrie case made that tradeoff visible. The question now is whether users will change their behavior in response. Probably not widely. Convenience usually wins. But if you care about privacy, the local storage route is worth considering despite its complexity.

Estimated data retention periods show that backend systems may retain data longer than user-accessible periods. (Estimated data)

The Legal and Ethical Questions Around Data Recovery

From a legal perspective, the Guthrie case clarifies something important: data you've deleted and can no longer access might still be admissible in court if law enforcement can recover it.

This has interesting implications. If you delete incriminating footage from your Nest camera, you might think you've destroyed evidence. But investigators could potentially recover it anyway. This could cut both directions: in civil disputes, it prevents bad actors from hiding evidence through deletion; in privacy invasions, it means you can't actually delete surveillance footage even when you want to.

The ethical question is thornier. Should Google have recovered the data without being compelled by court order? The company apparently did it voluntarily. On one hand, it helped solve a serious crime. On the other hand, it established a precedent that Google will cooperate without legal process if the case seems important enough.

Who decides what's important enough? Google's general counsel? Public pressure? Law enforcement's request? There's no transparency here. If the Guthrie case had been less high-profile, would Google still have recovered the data? What if someone requests data recovery for a property crime, or a civil dispute, or a political investigation?

There's also the question of consent. When you sign up for Nest, you're consenting to Google's terms of service, which mention that the company may comply with legal requests. But you're not consenting specifically to data recovery for investigation assistance. You're not being told that deleted data can be recovered. That information is material to your consent. Without it, your agreement to the terms is uninformed.

From a policy perspective, several approaches are possible. Google could transparently disclose how long deleted data persists and under what circumstances it will cooperate with authorities. The company could establish clear standards: only serious felonies, only with court orders, only with specific judicial review. Or Google could actually delete data immediately when users delete it, regardless of the operational costs.

As of now, none of these approaches is in place. Google remains deliberately vague, maintaining flexibility to cooperate with authorities while preserving plausible deniability about data retention.

What Google Has Actually Said (and Not Said) About This

When news of the Guthrie case broke, various outlets reached out to Google for comment. The company has been characteristically careful in its responses.

Google confirmed that it recovered the footage and provided it to investigators. That's public knowledge. But when asked about its general data retention policies, the company's statement became vaguer. Google representatives noted that it "complies with law enforcement requests in accordance with applicable law and legal process," which is non-committal to the point of meaninglessness. All companies say this.

When specifically asked how long deleted data persists in Google's backend systems, representatives didn't answer. There was no statement, no clarification, no timeline. This silence is notable. It suggests that either Google doesn't have a clear answer (which would indicate poor data governance on the company's part) or Google prefers not to disclose the answer (which would be intentional opacity).

Google also hasn't clarified whether users can request recovery of their own deleted footage. Can you call up Google support and say "I deleted a video by accident three months ago, can you recover it?" Presumably, you cannot, at least not for free. Google probably reserves this capability for serious investigations. But this creates an asymmetry: the company can recover your deleted data, but you cannot.

When Google announced its Gemini-powered smart home update late in 2024, we specifically asked whether the company would disclose detailed retention policies for videos. Representatives avoided the question entirely. This is Google's playbook: when asked about data retention, deflect. When asked specifically about deleted data, offer no response. When asked under what circumstances the company will cooperate with authorities, cite legal compliance without elaborating.

The company's public statements about Nest privacy focus entirely on the positive: your videos aren't used to train AI, they're encrypted in transit, they're stored securely. All true, probably. But none of it addresses the core issue: can Google retrieve videos you've deleted, and will it do so voluntarily or under legal compulsion?

Those are the questions that matter. And Google isn't answering them.

In the Nancy Guthrie case, 85% of the data was initially unrecoverable due to the free tier's limitations, but 5% was unexpectedly recovered, highlighting privacy and data retention issues. Estimated data.

Implications for Other Cloud Services

The Guthrie case doesn't uniquely implicate Google. Every major cloud provider faces the same technical realities and business pressures.

Amazon's Ring doorbell cameras work similarly: free users get a limited history window, paid users get longer storage, and deleted footage might persist in backend systems. Amazon has an even larger law enforcement partnership program than Google. Ring actively works with police departments across the country, providing footage to investigators. The company's willingness to cooperate is explicit and documented.

Apple's Home Kit Secure Video offers similar tiered storage. Microsoft's cloud services have comparable architectures. None of these companies has publicly disclosed detailed data retention policies for deleted content. None has specified under what circumstances they'll cooperate with authorities or whether users can request recovery of their own deleted data.

This suggests the Guthrie case is exposing a systematic issue, not a Google-specific problem. Across the cloud security camera industry, deleted footage probably persists longer than users realize. Every major provider probably has the technical capability to recover it. The question is whether they will.

For users, this creates a dilemma. Security cameras are genuinely useful. They deter theft, help identify intruders, and create evidence if something goes wrong. But they also create persistent records that you don't fully control. Choosing to use cloud-based cameras means accepting this risk, even if companies aren't transparent about it.

The only real alternative is local storage, which comes with its own risks and inconveniences. Or you forgo cameras entirely and accept the security loss.

None of these options is perfect. But at least they involve conscious tradeoffs rather than naive assumptions about deletion.

Best Practices for Securing Your Own Camera Footage

If you do use cloud security cameras, you can minimize risks through several practical steps.

1. Understand Your Provider's Actual Policies: Don't just read the marketing material. Look for technical documentation, privacy FAQs, and data retention specifications. If they're not available, that's a red flag. Email the company directly with specific questions about data retention after deletion. Their reluctance to answer tells you something.

2. Choose Your Storage Tier Deliberately: The cheapest option (free tier) often comes with the shortest retention windows. If you want longer storage, upgrade. But understand exactly what you're paying for: event-based recording versus continuous, number of days retained, backup redundancy. Don't assume higher prices mean better privacy. They usually just mean longer data retention, which is different.

3. Assume Deleted Data Persists: Plan accordingly. Don't record anything you'd be uncomfortable with Google, Amazon, or law enforcement seeing. Don't rely on deletion as a privacy mechanism. If you have sensitive information you need to hide, don't put it in a cloud camera's view.

4. Review Footage Regularly: If something happens you don't want recorded, you need to delete it while the data is still in your user-accessible window. After three hours for Google's free tier, you're relying on the company's actual deletion process, which is opaque.

5. Consider Hybrid Approaches: Use a local NAS for continuous recording and supplement with a cloud camera for remote access when you're traveling. This way, sensitive footage stays local while you maintain the convenience of cloud backup.

6. Encrypt if Possible: Some systems allow you to encrypt footage before uploading. This is better than nothing, though companies can presumably still recover encrypted data and decrypt it server-side if they have the keys.

7. Use Strong Passwords and 2FA: The biggest risk to your camera footage is probably unauthorized access to your account, not the company itself retrieving data. A hacked account is a real security vulnerability.

8. Read the Privacy Policy Updates: Companies update their terms regularly. Policy changes might expand when they'll cooperate with law enforcement or how long they'll retain data. You won't know if you don't read updates.

None of these steps is bulletproof. But they reflect the reality that cloud services involve tradeoffs between convenience and control. Understanding those tradeoffs is the first step toward managing them.

The Broader Conversation About Digital Privacy

The Guthrie case touches on something bigger than just security cameras. It's part of a broader erosion of the line between private and public, between deletion and persistence.

We live in an age of comprehensive digital recording. Phones record video. Doorbells record video. Cars record video. Stores record video. Governments record video. The question isn't whether you're being recorded—you are, constantly. The question is what happens to that data.

For decades, digital privacy advocates warned about this. They said data collection was expanding, storage was getting cheaper, and deletion was becoming impossible. For decades, companies and governments said these warnings were overblown. Your data is safe. We take privacy seriously. Deletion works as advertised.

The Guthrie case is evidence that the warnings were right. Not because Google did anything technically surprising—the company's actions were perfectly reasonable from an infrastructure perspective. But because it proved that deletion is more fragile than people assumed.

This has political implications. In democracies, citizens rely on the ability to keep their home private. A recording of your doorbell means recordings of who visits you: activists, lawyers, journalists, friends, family. If governments can access those recordings through court orders or even voluntary cooperation, they have information about your associations. Associations are protected speech in the US and many other democracies. Surveillance of associations is the opposite of privacy.

It also has commercial implications. Companies get smarter about what data to request. A lawyer representing someone in a divorce now knows they can request Nest footage. An insurance company investigating a claim knows it can request camera footage. A marketer trying to understand consumers knows there are millions of cameras recording consumer behavior in public spaces.

Over time, the assumption that you can delete something from the internet dies. It becomes understood that everything is permanent, recoverable, and potentially accessible to anyone with enough leverage. That understanding changes behavior. People record less, share less, move around less. The panopticon becomes not just a metaphor but a lived reality.

The Guthrie case is a small step in that direction. One video recovered from one deleted incident. But it's representative of larger trends. Understanding the technical reality—that deleted doesn't mean gone—is the first step toward demanding better policies and building different systems.

Looking Forward: What Might Change

Several developments could reshape the landscape of camera data and privacy.

Regulatory Pressure: Governments, particularly in Europe, are increasingly skeptical of how tech companies handle data. The GDPR includes a "right to be forgotten," though implementation is incomplete. Future regulations might require companies to actually delete data on schedule rather than merely removing user access. This would force architectural changes at Google and other companies.

Litigation: If someone sued Google arguing that the company's vague deletion policies constitute deceptive advertising, the company might be forced to either clarify its practices or change them. Class action suits have reshaped tech company behavior before.

Reputation Pressure: If the Guthrie case sparks broader awareness of how cameras work, consumers might demand transparency. Companies that clearly disclose data retention policies and deletion procedures might gain market share versus competitors that remain opaque.

Technical Solutions: Researchers are developing better encryption, better ephemeral storage, and better systems for distributed data deletion. These technologies are expensive and complex, but they exist. If enough users demand them, companies will implement them.

Market Alternatives: Startups might build security camera systems that actually provide the privacy users think they're getting. Companies like Wyze are positioning themselves as privacy-focused. If they gain significant market share, it'll force incumbents to improve.

None of these is guaranteed. It's entirely possible the Guthrie case becomes a footnote, the market forgets about the issue, and camera data retention remains opaque. That's actually the most likely outcome. Privacy concerns have a short shelf life in the public consciousness.

But the possibility exists for change. The technical capability to delete data truly and completely exists. The regulatory framework to require it exists. What's missing is the political will and consumer demand. The Guthrie case might be the spark that ignites that will.

Or it might just be a remarkable story about one high-profile case where deleted footage was recovered. Time will tell.

Practical Scenarios: Where This Matters Most

To make this abstract issue concrete, consider how deleted camera data might actually affect real people in real situations.

Scenario 1: Domestic Violence: Someone escapes an abusive relationship and moves to a safe house. The abuser's lawyer, during custody proceedings, requests doorbell camera footage from the survivor's new home. If that footage was deleted but recoverable, it could reveal the survivor's address and associates to the abuser. The deletion was supposed to provide privacy and safety. The recovery undermines both.

Scenario 2: Activists and Protesters: Someone hosts meetings for a political or social group in their home. They delete the doorbell footage regularly to protect their guests' privacy. Authorities investigating the group request recovered footage, learning the identities of everyone who visited. The deletion was meant to protect people. Recovery reveals them.

Scenario 3: Medical Visits: Someone receives sensitive medical equipment deliveries or home visits from healthcare providers. They delete the footage for privacy. An insurance company or employer requests the data as part of an investigation. The deletion was supposed to be private. Recovery makes it public.

Scenario 4: Financial Transactions: A small business receives cash deliveries or expensive shipments. They delete doorbell footage regularly. A competitor or rival requests the footage through legal discovery in a civil dispute. The deletion was meant to protect business operations. Recovery exposes them.

Scenario 5: Accidental Recording: Someone records something sensitive, realizes it, and deletes it. An ex-partner or rival requests recovery. The deletion was intentional and understandable. Recovery ignores the person's explicit intent.

In each scenario, the expectation is that deletion means something is gone. The reality is that recovery is possible, and people with legal leverage or official authority can access it. That gap between expectation and reality is where privacy violations happen.

The Guthrie case is arguably the only scenario where recovery serves an important public interest. A serious crime was potentially solved because of recovered footage. That's valuable. But it's also rare. Most requests for recovered data serve individual, corporate, or government interests that don't align with public good.

Recognizing these scenarios is the first step toward demanding better policies and building better systems.

FAQ

What is cloud storage data retention, and how does it work with security cameras?

Cloud storage data retention refers to how long a service provider keeps your data after you've uploaded it. For security cameras, this typically means how long video footage is stored after recording. Nest free users get three hours of accessible history, but the data may persist longer in backend systems even after you can't access it. Most companies use tiered storage, moving data to slower, cheaper systems over time, which naturally extends how long it can be recovered.

Can Google recover deleted Nest footage for all users, or only in criminal investigations?

Google can technically recover deleted Nest footage from its backend systems, but the company hasn't disclosed clear criteria for when it will do so. In the Guthrie case, Google appears to have cooperated voluntarily, though it's unclear whether this required a court order or was done as a goodwill gesture. For regular users, Google doesn't offer self-service recovery of deleted footage, even if you upgrade to a paid plan after deletion. The company's policies on this are not publicly transparent.

How does data actually persist after deletion in cloud systems?

When data is deleted from a cloud system, it typically becomes inaccessible to the user immediately, but the physical data remains on storage devices until that storage space is needed for new data. Cloud infrastructure uses redundancy and backups, which means multiple copies exist across different locations. Deleting one copy doesn't immediately delete all copies. Additionally, data is often compressed, encrypted, or combined with other data, making it complex to purge completely. Enterprise systems may take weeks or months to fully overwrite deleted data.

What's the difference between "deleted" and actually destroyed in cloud storage?

Deleted means you can't access it anymore, and the company has marked it for removal. Destroyed means the physical storage space has been overwritten with new data, making recovery practically impossible without forensic techniques. For users, deletion happens instantly when you press delete. Destruction happens gradually, over days, weeks, or longer, as the company's systems naturally overwrite old data. Companies can choose to accelerate destruction, but it's expensive and operationally complex, so most don't.

Should I use local storage instead of cloud cameras if I'm concerned about privacy?

Local storage via a NAS or DVR gives you physical control of footage and keeps data off company servers. However, it requires more technical setup, active maintenance, backup management, and is vulnerable to physical theft or destruction, as happened in the Guthrie case. Cloud storage is more convenient and reliable but means a company has access to your data. A hybrid approach—local continuous recording plus cloud backup for remote access—might offer the best balance. Choose based on your threat model: what are you actually trying to protect against?

Will deleted Nest footage ever be truly gone, or should I assume it's permanent?

Based on the Guthrie case, you should assume deleted Nest footage might persist in Google's systems for days, weeks, or longer, and could potentially be recovered by Google, law enforcement, or others with sufficient legal authority and technical access. Google hasn't disclosed how long it retains residual data, so there's no way to know when it's truly gone. Plan your privacy assuming deleted footage might not be deleted, and avoid recording anything you'd be uncomfortable with authorities eventually seeing.

What should I do if I want to use a security camera but also protect my privacy?

First, understand your camera provider's actual data retention policies—read technical documentation, not just marketing material. Second, choose your storage tier based on your real needs. Third, assume deleted data might persist and plan accordingly. Fourth, consider local storage supplemented with cloud for remote access. Fifth, use strong authentication to prevent account hacking. Sixth, review the privacy policy regularly for changes. Finally, recognize that using a cloud camera involves tradeoffs between convenience and privacy. Be intentional about making that tradeoff rather than assuming you have privacy you don't actually have.

Key Takeaways

The Nancy Guthrie case revealed a critical gap between how users think cloud security cameras work and how they actually work. Your understanding of deletion—that it means the data is gone—is probably wrong. Here's what you need to know.

First, deleted Nest footage might persist in Google's backend systems far longer than the three-hour user window. The company recovered footage nine days after deletion in the Guthrie case, suggesting residual data persists significantly longer than advertised.

Second, deletion creates an asymmetry: you can't recover your deleted footage, but Google can. Law enforcement probably can too. This means Google, governments, competitors, and litigants all have more access to your data than you do, even after you've deleted it.

Third, Google hasn't been transparent about how long residual data persists or under what circumstances the company will cooperate with authorities to recover it. The company's silence on these questions suggests either poor data governance or intentional opacity.

Fourth, this isn't unique to Google. Every major cloud provider faces the same technical realities. Amazon Ring, Apple Home Kit, and others probably have similar persistent data. It's how distributed cloud infrastructure works at scale.

Fifth, you have practical alternatives: local NAS storage, hybrid approaches combining local and cloud, or switching to privacy-focused competitors. None is perfect, but each involves conscious tradeoffs rather than naive assumptions.

Sixth, privacy implications extend beyond security cameras. If governments can request recovered data, they can map associations, identify activists, and monitor behavior. The Guthrie case is admirable in its result (helping solve a serious crime), but it sets a precedent that will likely extend to less sympathetic cases.

Finally, the technical capability to delete data truly and completely exists. The regulatory framework to require it exists. What's missing is consumer demand and political will. If you care about privacy, demanding transparency from your camera provider is the first step.

The Guthrie case is a reminder that in the age of cloud storage, nothing is ever truly deleted. Plan your privacy accordingly.

Related Articles

- VPN Trust Initiative: New Annual Audit Rules [2025]

- Why Brits Fear Online Privacy But Trust the Wrong Apps [2025]

- Microsoft Handed FBI Encryption Keys: What This Means for Your Data [2025]

- Ring and Watch Duty Partner on Wildfire Tracking [2025]

- California's DROP Platform: Delete Your Data From 500+ Brokers [2025]

![Google Recovers Deleted Nest Videos: What This Means for Your Privacy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-recovers-deleted-nest-videos-what-this-means-for-your/image-1-1770842205456.jpg)