Why Brits Fear Online Privacy But Trust the Wrong Apps

There's a disconnect happening right now in British bedrooms, offices, and coffee shops across the country. People are genuinely worried about their online privacy. They think about it. They stress about it. They're installing VPNs, changing passwords, adjusting privacy settings. But here's the thing—they're often protecting themselves against the wrong threats using the wrong tools.

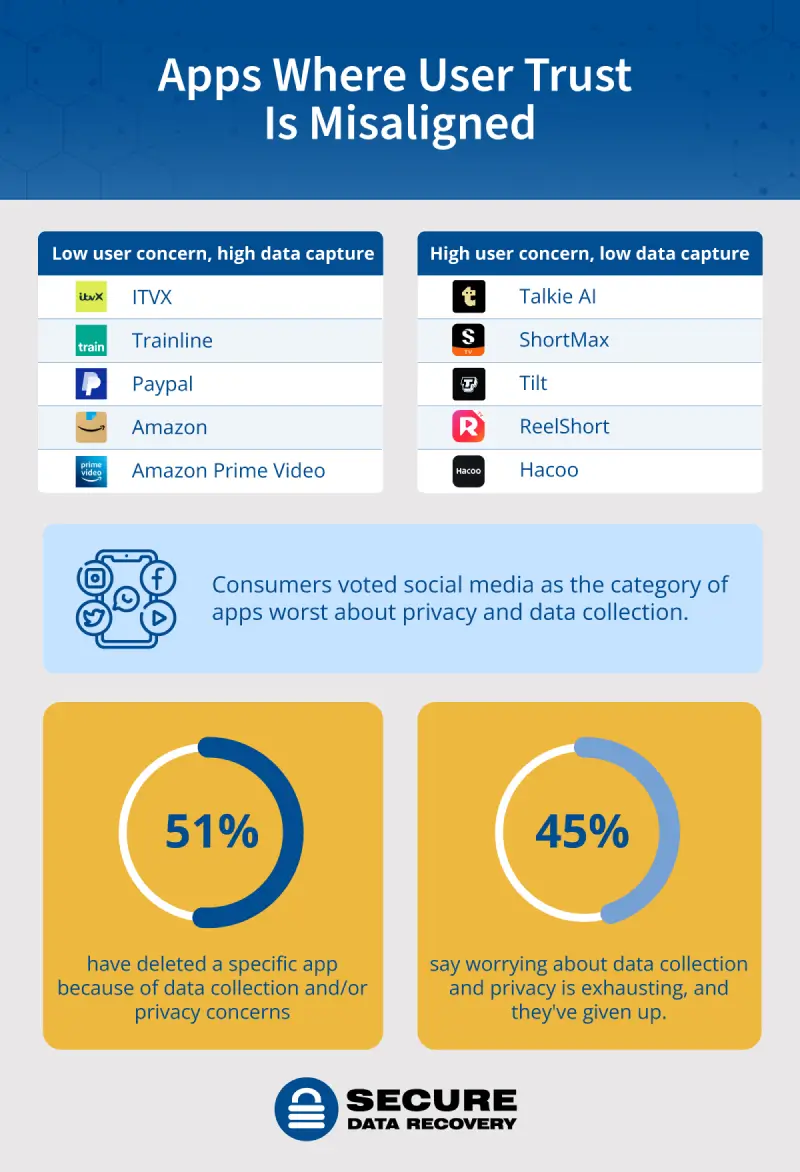

A major study from Proton revealed something genuinely unsettling: most UK users have their privacy concerns completely backwards. They're anxious about services that actually take privacy seriously, while trusting apps that openly collect and monetize their personal data. It's not stupidity. It's a knowledge gap that tech companies have deliberately created.

This matters because privacy isn't just about paranoia or theory anymore. We're talking about real money, real manipulation, and real control over your digital life. When you misunderstand which apps protect you and which ones exploit you, you're making worse decisions across the board. Your VPN becomes less useful. Your password manager becomes riskier. Your entire digital hygiene strategy falls apart.

Let's dig into what the research actually found, why people got it so wrong, and most importantly, how you can actually protect yourself in 2025.

TL; DR

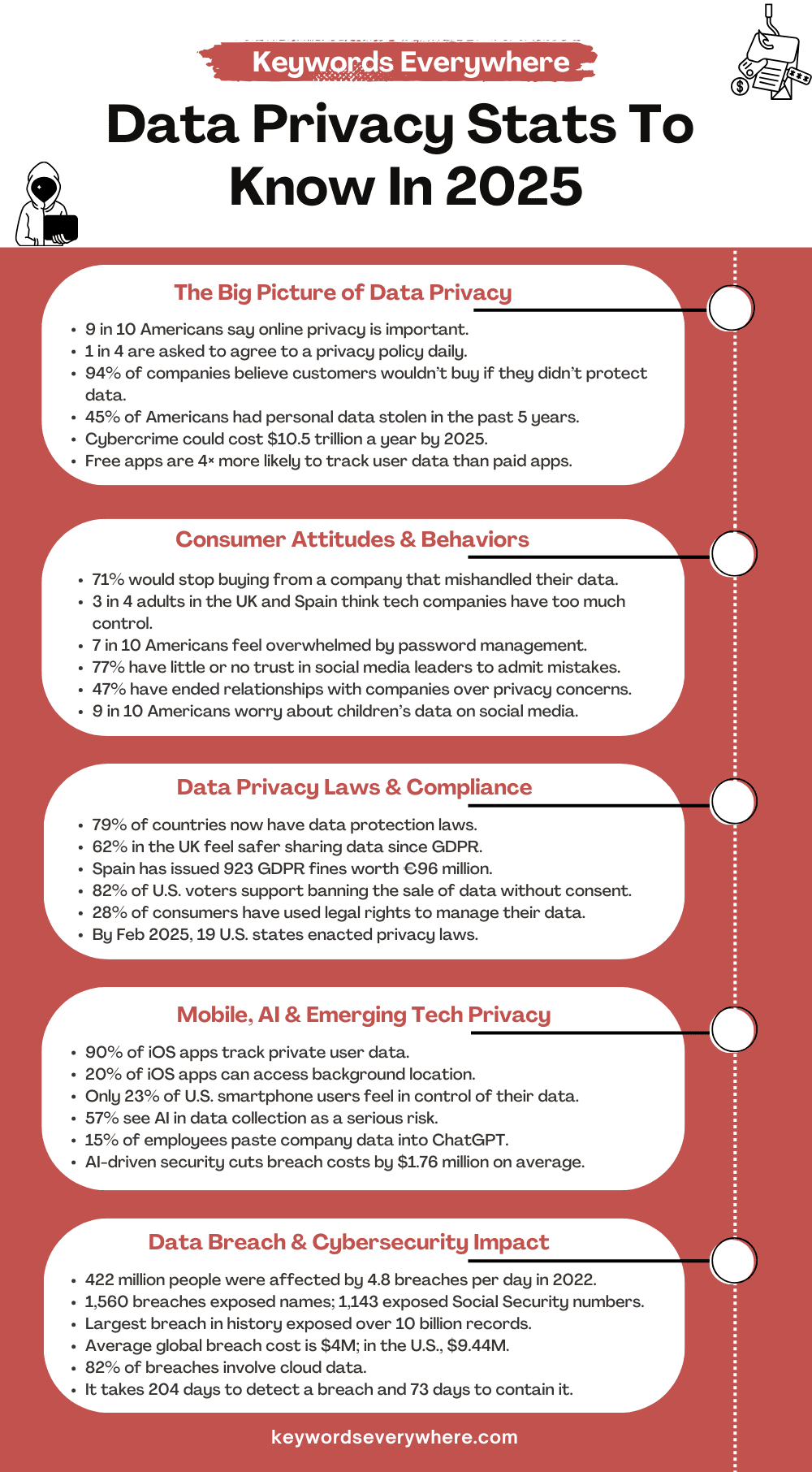

- Privacy paradox is real: 73% of UK users claim to care about privacy, but 2 in 3 trust apps that explicitly sell data

- Wrong trust equation: WhatsApp (encrypted end-to-end) rated as less trustworthy than TikTok and Instagram (data harvesting machines)

- The knowledge problem: Most users can't distinguish between encrypted messaging and data collection, making informed decisions impossible

- VPN misconceptions: People think VPNs solve privacy, but use them to access blocked content instead of protecting data

- The real cost: Companies exploit this confusion to harvest billions in behavioral data annually

- Bottom line: Privacy protection requires understanding what data you're actually giving away and to whom

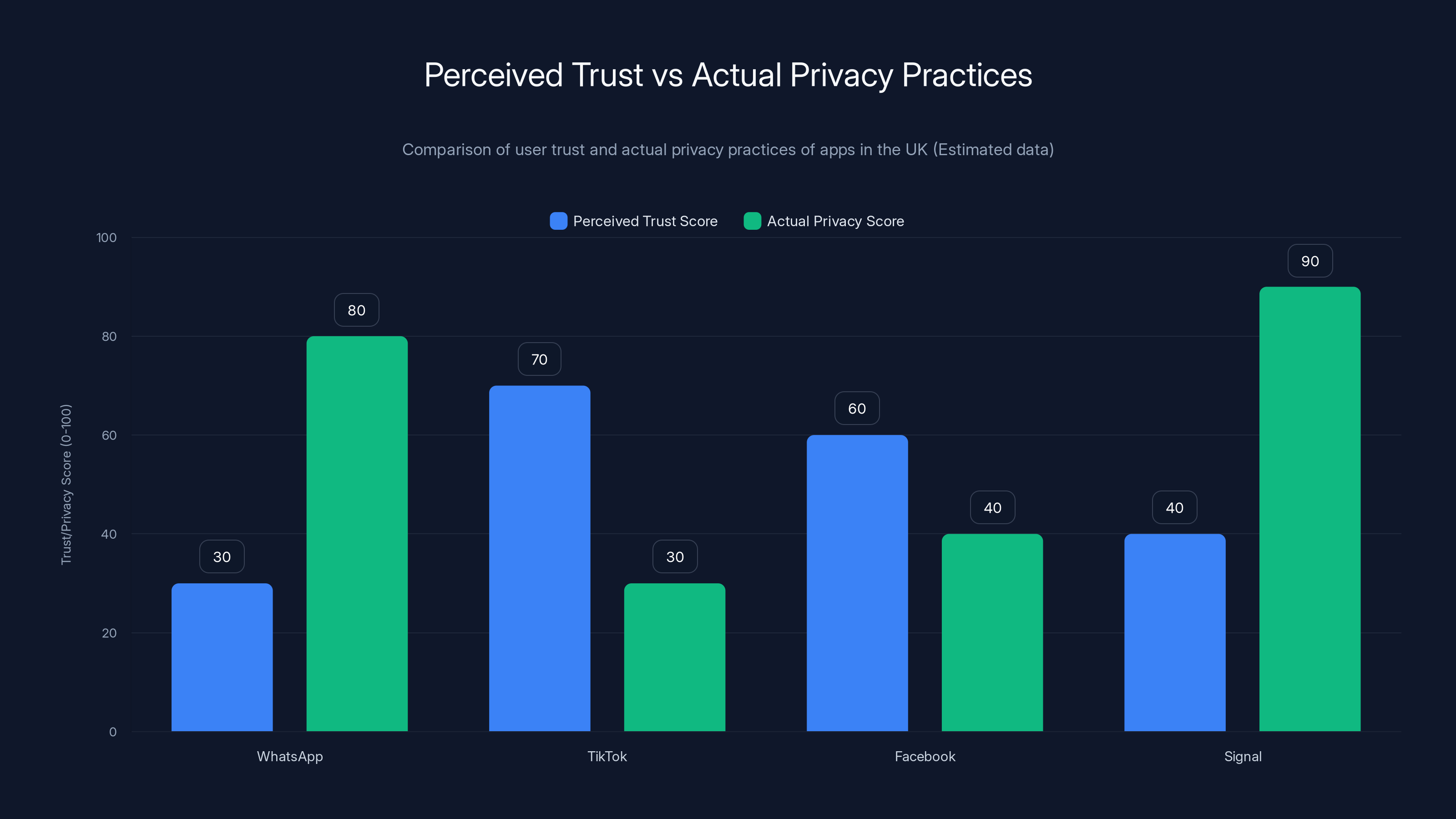

Survey reveals a paradox: apps with strong privacy measures like WhatsApp and Signal are trusted less than those with weaker privacy practices like Instagram and TikTok.

Understanding the Privacy Paradox in the UK

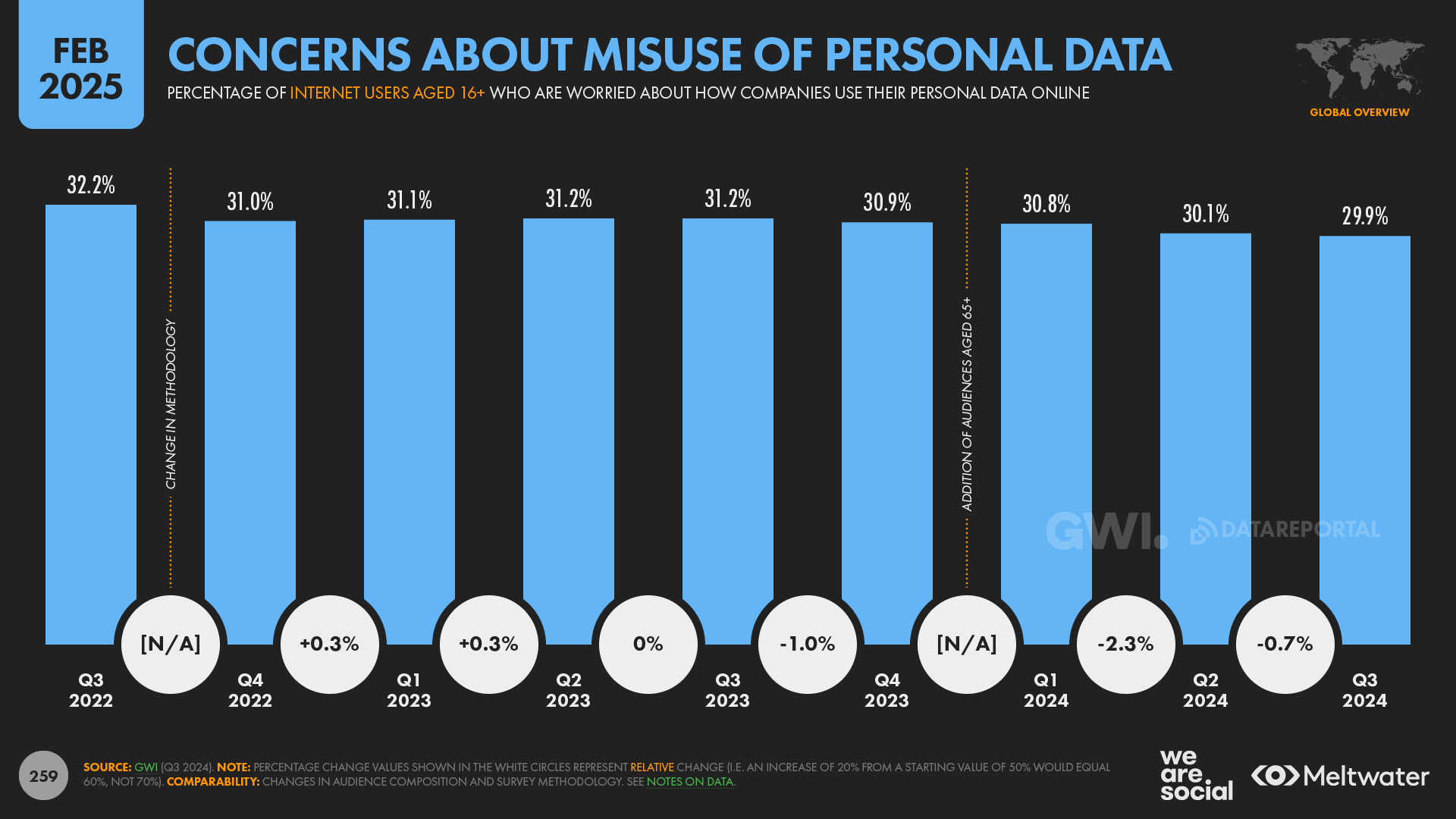

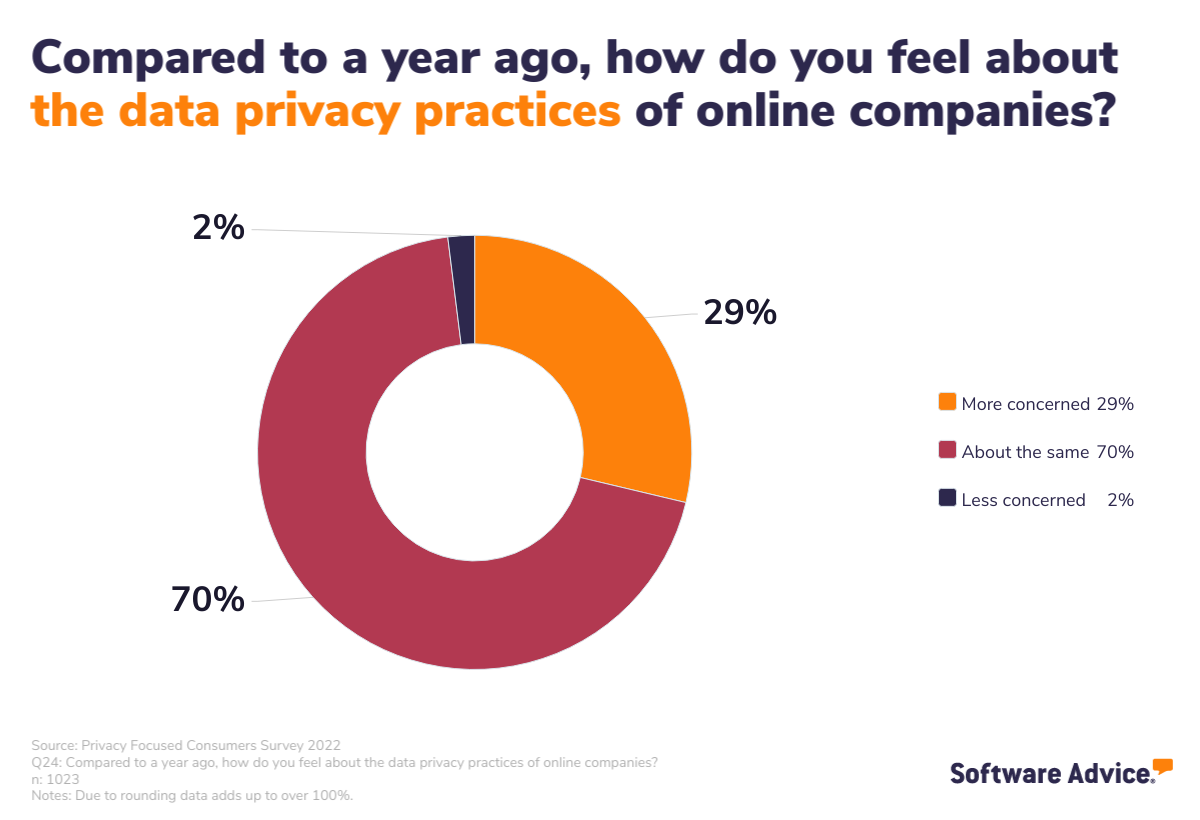

The privacy paradox isn't new, but the 2025 data from Proton shows it's worse than we thought in Britain. People genuinely care about privacy—surveys consistently show 70%+ say it matters to them. But when you watch what people actually do, the gap becomes stunning.

This gap exists because privacy is abstract. You can't see the data flowing from your phone to server farms in Virginia or Beijing. You can't watch TikTok extract your viewing patterns, scroll speed, pause duration, and behavioral signals. You can't observe Facebook building a psychological profile of you across the entire internet. It's invisible, which makes it feel less real than security threats you can imagine like hackers stealing your password.

The British research specifically tested this. They asked people to rate how much they trust various apps with their personal data. Then they looked at the actual privacy policies, encryption practices, and data collection behaviors. The rankings were inverted from reality.

People perceived encrypted messaging apps as suspicious. They perceived data harvesting services as trustworthy. One user described WhatsApp—which literally cannot read your messages even if forced by law—as risky. Meanwhile, TikTok, which has admitted in court filings to accessing clipboard data, location history, and behavioral analytics, was rated as fine.

This isn't individual failure. This is systematic confusion created by contradictory signals. TikTok's slick interface and open-sourced privacy policy creates an illusion of transparency. WhatsApp's corporate ownership by Meta (which profits from selling ads based on data collection) creates an assumption it must be corrupt.

The reality is backwards. WhatsApp's encryption means Meta literally cannot see your conversations. TikTok's 500 million daily active users represent a goldmine of behavioral data that drives one of the world's most sophisticated advertising networks.

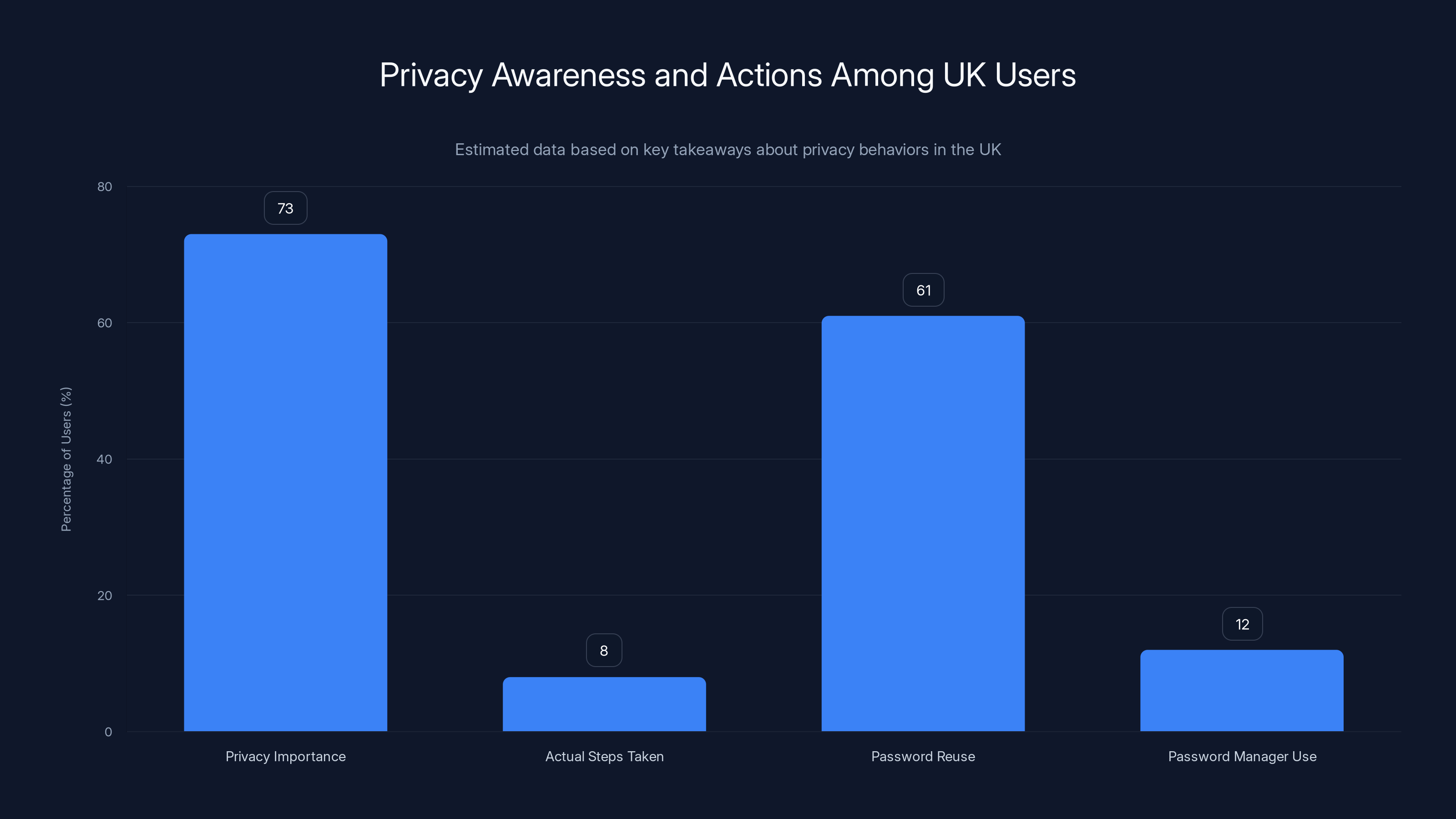

The chart highlights that 61% of UK users reuse passwords across sites, while only 12% use password managers and 34% have enabled two-factor authentication.

What the Proton Research Actually Revealed

Proton, the Swiss-based privacy company, surveyed thousands of UK residents about which apps they trust with personal information. The results broke down into clear patterns that should worry anyone about digital literacy.

When asked about messaging apps specifically, responses were illuminating. WhatsApp—which uses end-to-end encryption by default on all messages—was rated by only 37% of respondents as trustworthy. Signal, which is open-source and literally cannot access your messages, came in at 32%. These are the two most private messaging options available.

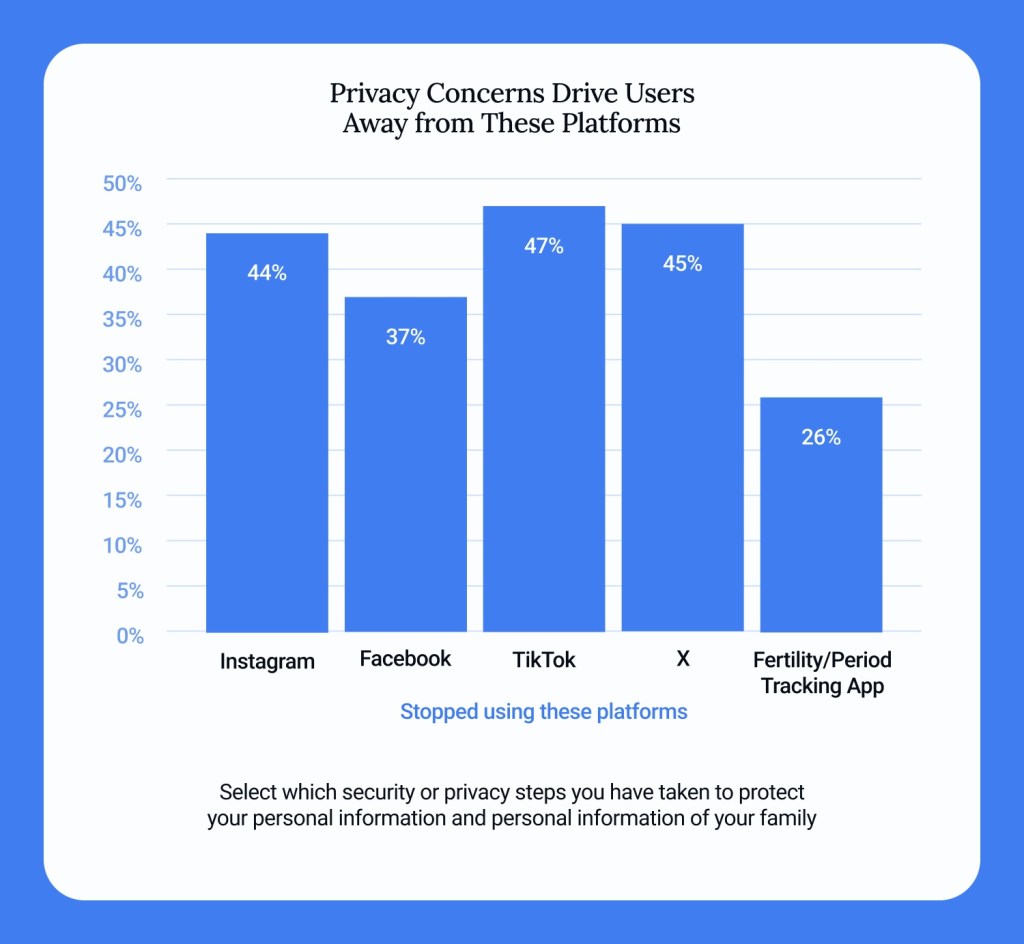

Contrast that with Instagram (65% trust), TikTok (48% trust), and Facebook (41% trust). Now here's the problem: Instagram is owned by Meta, which admits in its transparency reports to storing your messages, your location data, your contacts, your behavioral patterns, and your social graph. TikTok's algorithm requires constant monitoring of every action you take. Facebook's entire business model is built on harvesting personal data.

So users are rating services that spy on them as more trustworthy than services that literally cannot spy on them. That's not caution. That's the opposite of how trust should work.

The research also measured what people thought privacy actually meant. Most respondents defined it narrowly: not getting hacked, or maybe not having strangers see their photos. Almost none understood that privacy also encompasses how your behavior is tracked, how your attention is manipulated, or how your data is used to exclude you from opportunities.

One particularly telling finding: when shown the actual privacy policies of major apps (without the app name attached), people rated them accurately. They understood the risks. But when the brand was visible, their assessment shifted. Brand trust overrode data understanding. Apple's privacy marketing message actually worked so well that people trusted Apple even in scenarios where they shouldn't. Meta's privacy theater (the public "we care about you" messaging) also distorted people's judgment.

The Trust Inversion Problem

Why do UK users trust the wrong apps? The answer involves psychology, marketing, interface design, and genuine confusion about what privacy actually means in practice.

First, there's the interface honesty problem. TikTok and Instagram show you exactly what they're doing: recommending videos, showing you ads, connecting you to creators. The process is visible. You see the input (your engagement) and output (recommendations). This visibility creates a false sense of transparency. You know what they're doing, so you feel like you have control.

End-to-end encrypted apps like WhatsApp and Signal do the opposite. They're opaque. You send a message, it's encrypted, and you have no idea how the cryptographic process works. That opacity—even though it protects you—creates distrust. If you can't see the mechanism, it must be hiding something.

Second, there's the brand narrative problem. Meta spends billions on marketing and public relations. It has built a narrative that it "cares about privacy" even while its business model requires invading it. This contradiction doesn't matter because the PR message reaches people before the reality does. TikTok faces regulatory scrutiny, which paradoxically can increase its appeal among younger users (forbidden fruit effect).

Meanwhile, WhatsApp changed its privacy policy to align with Meta's data practices, and people abandoned it in droves. Signal couldn't explain its security through marketing because security, by nature, is invisible. You can't show people a feature they can't see.

Third, there's the asymmetric information problem. When you use TikTok, the company knows exactly how much data it's collecting because it built the infrastructure. When you use Signal, the company knows nothing about your behavior because of encryption. But the average user doesn't understand this asymmetry. They assume the company knows more about security than it does.

It creates perverse incentives. A company that wants to be trusted needs to be transparent about its data collection practices. Companies that are opaque (either through encryption or policy darkness) seem less trustworthy. Encryption looks like secrecy. Transparency looks like honesty.

Estimated data shows a significant discrepancy between perceived trust and actual privacy practices among popular apps in the UK. Users tend to trust apps with poor privacy practices more than those with strong encryption.

Privacy Concerns vs. Privacy Actions: The Gap

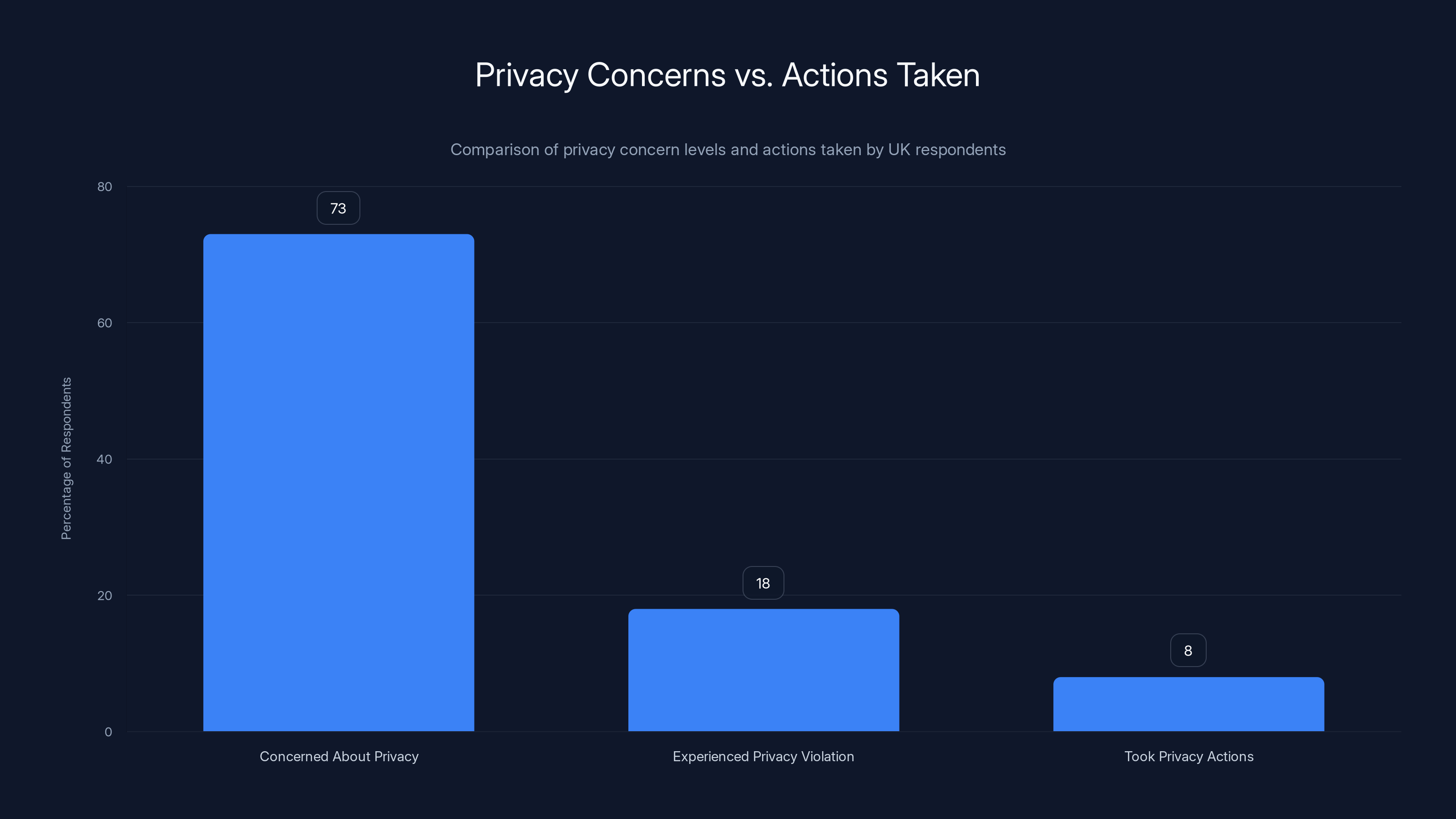

The British research revealed a massive chasm between what people say they care about and what they actually do to protect themselves.

When asked directly, 73% of UK respondents said online privacy was important to them. When asked if they'd experienced a privacy violation (data breach, identity theft, stolen data), only 18% had reported incidents. When asked what actions they'd taken in the past month to protect privacy, the number dropped to 8%.

This isn't because people don't care. It's because privacy protection is effortful. Changing privacy settings requires navigating confusing menus. Understanding your data rights requires reading legal documents. Installing a VPN adds a step to every internet session. Learning which apps to trust requires time and expertise.

Most people default to hoping nothing bad will happen. They've developed a kind of privacy learned helplessness: the belief that their individual choices don't matter, so why try?

But here's where it gets interesting. The research also showed that when people did take action, they often took the wrong action. They installed VPNs primarily to access blocked content (52% of VPN users), not to protect their data (28%). They assumed a VPN would make them completely anonymous (87% thought this), when in reality a VPN just hides your IP address—your behavior is still visible to the sites you visit.

They changed passwords—a good practice—but used the same password across multiple accounts (61%), eliminating much of the benefit. They said they trusted privacy-focused brands but continued using mainstream platforms because of network effects (WhatsApp for family group chats, Instagram for staying connected with friends).

The actions people took were often security theater. They created the feeling of protection without providing actual protection. A VPN makes you feel secure. Changing your password makes you feel careful. But if you're still using a mainstream email service that profiles you, syncing location data, and allowing apps to track your behavior, those security moves barely register against your actual exposure.

How Data Collection Actually Works: What Most People Miss

Understanding why people trust the wrong apps requires understanding how modern data collection actually works. Most people's mental model is completely wrong.

People think of data collection like this: You use an app, the app stores your information, and if the company wants to spy on you, they look at your stored information. This model makes them worry about hacking (someone stealing the stored data) but not about collection itself (the process of gathering data in the first place).

Reality is different. Modern data collection works like this: Every action you take is logged. Every interaction, pause, swipe, and scroll is timestamped. Every app you open, every site you visit, every person you message, every search you perform—all of it is captured. The data isn't stored because it's valuable. It's captured because capturing it is valuable.

That data flows into machine learning systems that learn to predict what you'll do next. These models identify patterns you don't even know you have. Your political leanings, your financial stability, your mental health state, your romantic status—all of these can be inferred from behavioral data with disturbing accuracy.

For instance, TikTok's recommendation algorithm doesn't just learn what videos you watch. It learns what makes you pause, what makes you rewatch, what time of day you're most engaged, how long you're willing to watch content you're not interested in if the next video might grab you. It learns your psychological vulnerabilities and how to exploit them.

Facebook's model does something similar across multiple platforms. It tracks you on Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. It also tracks you through third-party websites using the Facebook Pixel (a tracking code on 40% of the web). It links this data to your identity, creating a profile that would require thousands of hours for a human to assemble, but which an AI assembles in seconds.

The privacy violation isn't storing this information. It's creating it. The harm isn't what happens to the stored data. It's what happens to you when you're treated as a prediction target instead of a person.

UK users don't understand this model because it's invisible and complex. They're still thinking in terms of the old privacy paradigm: keep your secrets. They're not thinking about the new paradigm: don't create behavioral patterns that can be sold to the highest bidder.

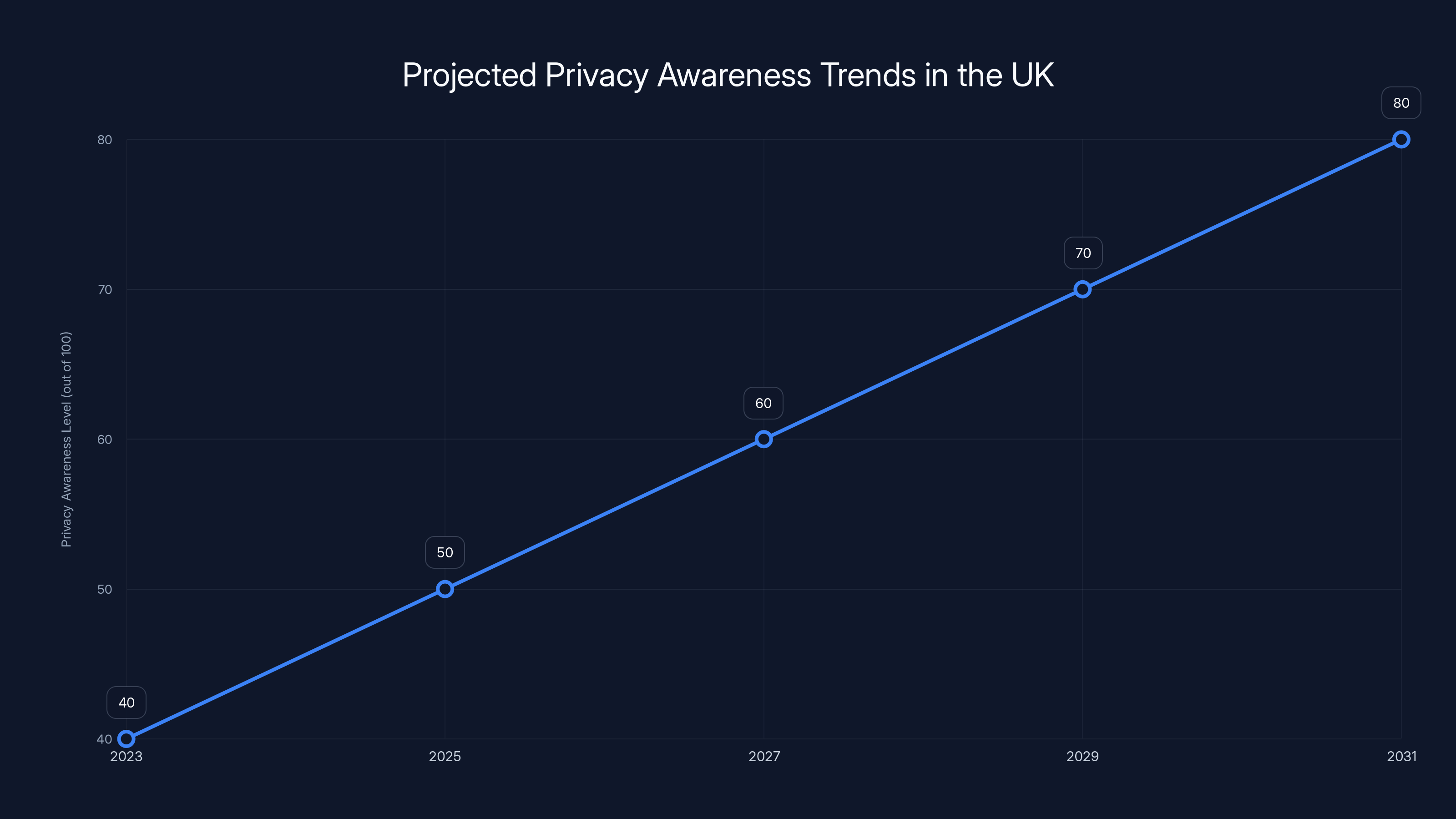

Estimated data suggests privacy awareness in the UK will gradually increase due to regulatory changes, technological advancements, and societal shifts.

The VPN Misconception Problem

VPNs have become the UK's favorite privacy solution. The research showed that VPN adoption has roughly doubled every two years since 2018. People see VPNs as privacy panaceas—install one, become invisible, problem solved.

The reality is messier and way less protective than people think.

A VPN (Virtual Private Network) masks your IP address. That's it. It's the internet equivalent of wearing a disguise—people can't see where you're calling from, but they can still hear everything you say and learn everything about you from your behavior.

When you use a VPN to visit a website, the website doesn't know your real IP address. But it knows everything else. It knows your device fingerprint (browser, plugins, fonts, resolution). It knows your behavior on their site. If you log in, it knows your identity. If you engage with content, they learn your preferences. The VPN didn't protect any of that.

Moreover—and this is crucial—you're just shifting your trust. With a regular internet connection, your internet service provider (ISP) can see your traffic (unless you use HTTPS, which most sites do now). With a VPN, your VPN provider can see your traffic. You've traded one third party for another.

The research found that most UK VPN users couldn't name their VPN provider's privacy policy. They downloaded the free version or grabbed one from a list, assuming all VPNs were equivalent. In reality, some VPN providers are themselves data harvesters. A few are operated by Chinese companies with close ties to the government. Others keep traffic logs that can be subpoenaed.

The worst part: people believe the VPN solves their privacy problem, so they stop thinking about privacy. They use the VPN and then continue with all the data-exposing behaviors. They log into Google on one tab while using the VPN on another (defeating the purpose). They enable location services. They sync their cloud backups. They don't use two-factor authentication. They assume the VPN has their back.

For British users, this is particularly problematic because the UK's Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) gives law enforcement broad surveillance powers. A VPN provides some protection against ISP surveillance, but not against warrant-based access. Understanding what a VPN does and doesn't do matters for actual security.

The Encryption Literacy Crisis

One of the starkest findings from the research: most UK users couldn't explain what encryption is or does.

When researchers explained that WhatsApp uses end-to-end encryption, respondents assumed this meant WhatsApp encrypted the data when it arrived at their servers—meaning WhatsApp employees could theoretically read it. They didn't understand that end-to-end means the encryption happens on your phone before leaving it, and the decryption happens on the recipient's phone. WhatsApp gets encrypted data it literally cannot decrypt even if it wanted to.

This single misunderstanding explains why users trust the wrong apps. They think encryption means the company might read your data later. They don't understand it means the company can't read your data ever.

Signal had even worse comprehension. Most people said they'd heard of it but assumed it was some kind of esoteric security tool for paranoid people or cybercriminals. The fact that it's actually designed for average people protecting everyday privacy didn't change their perception.

Meanwhile, they trusted apps that use ordinary HTTPS encryption—the same encryption that protects your banking. They assumed anything on the internet with a lock icon (standard HTTPS) was somehow private. They didn't understand that HTTPS encrypts your data in transit but the server still stores it, still logs it, still analyzes it.

This literacy gap is by design. Tech companies that profit from data collection have zero incentive to educate users about encryption. In fact, they actively lobby against strong encryption. Meanwhile, companies that actually protect privacy (small, non-profitable ventures like Signal) can't afford massive education campaigns.

Users are left to navigate with incomplete information. The research showed that young people (18-24) did slightly better at understanding encryption than older people (55+), but the difference wasn't dramatic. Understanding encryption requires education, and nobody's providing it systematically.

The chart highlights a significant gap between the high level of privacy concern (73%) and the low percentage of respondents taking action (8%). Estimated data.

App Permissions and What People Actually Consent To

Here's another eye-opening finding: most UK users don't read app permissions.

When installing an app, iOS shows a permissions request: "TikTok wants access to your camera." Most users just tap allow. Android users have a better system where permissions appear in settings, but most never look.

The research asked users what permissions they'd granted to the apps on their phones. Most had a vague idea. They knew social media apps had location access. They sort of remembered giving Instagram permission to use their camera. But they couldn't list all permissions, and more importantly, they didn't understand why apps needed those permissions.

Why does TikTok need location access if it's just a video app? To serve location-based ads and to collect movement data. Why does Spotify need full contact access? To improve its social features, but also to create a network graph of who knows whom, which is valuable data in itself.

When shown the full permission list for popular apps without the app name, users were shocked. They didn't realize they'd granted these permissions. But when the app name was visible, they rationalized it. "Well, if TikTok wants my location, they probably have a good reason."

This highlights how brand trust overrides data literacy. People don't actually know what they're consenting to, they don't understand why, and they rationalize it when confronted with the reality. This is a recipe for data exploitation.

The research also found that users who switched from Android to iPhone often thought they were getting more privacy (Apple's messaging does emphasize privacy). In reality, they were just getting different privacy violations from a different company. They trusted Apple's privacy claims more than Android's openness because Apple's marketing was better.

The Regional Differences in Privacy Awareness

The Proton study tested awareness across multiple countries. The UK results were particularly interesting when compared to other European nations.

Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) showed significantly higher privacy literacy. Users there were better at identifying which apps actually protected their data. They were more skeptical of corporate privacy claims. They were more likely to use encrypted communication.

The likely explanation: European regulation (specifically GDPR in EU countries) has forced companies to be more transparent about data collection. European users have been educated about their privacy rights through regulation. They've seen enforcement (GDPR fines to tech companies) that makes privacy regulations feel real rather than theoretical.

The UK, despite being geographically close to Europe, showed more privacy literacy before Brexit but the gap has widened since. Post-Brexit UK regulation has been slower to implement, and companies haven't faced the same enforcement pressures.

Mexico, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand showed patterns more similar to the UK. These countries have privacy regulations, but enforcement is weaker and company compliance messaging is sparser. Users knew they should care about privacy but had less clear information about how and why.

The US showed the worst privacy awareness. This makes sense given that US regulation is minimal and companies have essentially no legal requirements to limit data collection beyond specific sectors like healthcare and finance. American users were most likely to trust mainstream tech platforms and least likely to have heard of privacy-focused alternatives.

This geographic variance matters because it shows privacy awareness is teachable. When regulation forces transparency and enforcement backs it up, people learn. When companies are free to collect without limitation and government doesn't enforce transparency, people remain confused.

Despite 73% of UK users acknowledging the importance of privacy, only 8% take action, and 61% reuse passwords. Estimated data highlights a significant gap in privacy practices.

Password Practices and Authentication Reality

The research also examined how UK users handle authentication—mostly passwords, though increasingly biometric options.

Password practices were predictably bad. The research's survey found that 61% of UK users reported using the same password across multiple sites. Only 7% actually used unique, complex passwords for every account. Most people use a password they can remember (which means it's weak) or a variation (which means it's guessable).

When confronted with this reality, people rationalize it. "My password is long enough, it doesn't need to be complex." "Hackers don't target normal people like me." "I have a system for my passwords." These are all false comfort strategies.

The irony is that password reuse is exponentially more dangerous than weak passwords. A weak password on one site is a problem for that site. A reused password means that if any one of the sites gets hacked—and site breaches happen constantly—the attacker can try that password on your email, your banking, your social media.

Password managers solve this problem completely. They can generate truly random passwords, remember them, and autofill them. The research found only 12% of UK users employ password managers. Of those, most didn't trust them with sensitive accounts like banking or email, defeating much of the purpose.

The barrier to adoption isn't technical. It's psychological. Password managers seem like an extra step, even though they actually save time. They seem risky (putting all your passwords in one place), even though they're far safer than password reuse. They seem unnecessary until you experience a data breach.

Two-factor authentication (requiring a second verification method beyond your password) showed similar patterns. Only 34% of UK users had enabled it on important accounts. Among those who had, most used SMS (text message) authentication, which is surprisingly vulnerable. Only 8% used authenticator apps, which are far more secure.

The research highlighted that people's authentication practices create a risk pyramid. The most commonly used authentication method (weak password) is the least secure. The most secure methods (complex passwords plus authenticator app plus hardware keys) are used by fewer than 3% of the population.

The Corporate Responsibility Problem

One angle the research didn't explore deeply but deserves attention: the question of why UK users trust the wrong apps isn't really a user problem. It's a corporate problem.

Tech companies benefit from privacy confusion. If everyone understood that TikTok harvests behavioral data, they'd use it less or demand more privacy protections. If everyone understood that WhatsApp can't read their messages, they'd find Meta's data practices less concerning.

Companies actively work to maintain this confusion. They sponsor research that emphasizes the value of personalization (which requires data collection). They lobby against regulation that would force transparency. They use privacy-washing—making modest privacy improvements while continuing massive data collection.

Meta is instructive here. They repeatedly commit to privacy improvements while their business fundamentally requires data collection. They can't actually prioritize privacy without destroying their business model. So they create the perception of privacy progress while continuing surveillance.

Meanwhile, Signal and other privacy-first services operate at a loss. They can't afford to educate users because they don't have a revenue model. Users who do find them often complain that Signal has fewer features than WhatsApp (which is true—Signal refuses to add features that require data collection).

This creates a prisoner's dilemma. Individual users making rational choices (use the feature-rich app, assume privacy protection is overblown) leads to collectively irrational outcomes (widespread loss of privacy). A user switching to Signal is inconvenient. A billion users staying on WhatsApp maintains Meta's surveillance infrastructure.

The research implicitly highlights this: you can't solve a system problem through individual education. Users can't trust the right apps if the wrong apps have billions in marketing budgets and the right apps have none.

What Actually Protects You: The Real Strategy

Given that most UK users misunderstand privacy and trust the wrong apps, what actually works?

First, you need to accept that privacy in 2025 isn't about secrecy. It's about control. You can't prevent data collection entirely—the infrastructure requires it. But you can control who collects it and what they do with it.

This means: understand your threat model. Are you worried about your ISP? A VPN helps. Are you worried about websites tracking you? Browser extensions (uBlock Origin, Privacy Badger) help. Are you worried about your phone manufacturer tracking you? Change your phone settings. Are you worried about corporate surveillance? You probably should be, but no single tool fixes this.

Second, you need to realize that tools are not substitutes for understanding. A VPN without understanding what it protects is security theater. A password manager without unique passwords is incomplete. An encrypted chat app while posting your location on Instagram is pointless.

The strategy that actually works: use encrypted messaging for sensitive communication (Signal or Telegram), keep your location services off by default, use a password manager with unique passwords, enable two-factor authentication on important accounts, use a browser that doesn't track you (Brave or Firefox configured properly), periodically audit what permissions you've granted apps, and recognize that on open platforms (Instagram, TikTok, Twitter), you cannot expect privacy.

This isn't paranoia. It's matching your behavior to your actual exposure.

The Role of Regulation: How Rules Change Behavior

The research showed that privacy awareness is highest in jurisdictions with strong privacy regulation and enforcement. This matters for UK policy.

GDPR in the EU didn't magically make privacy better. But it did force transparency. Companies had to tell users what data they collected, why, and how long they kept it. It gave users rights to access and delete their data. Most importantly, it demonstrated enforcement through significant fines.

When Meta was fined 1.2 billion euros for privacy violations, it sent a message: privacy matters legally, not just morally. That message changed how companies behaved and how users thought about privacy.

The UK has its own data protection laws (the Data Protection Act 2018), but enforcement has been inconsistent. The Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) has smaller budgets than GDPR enforcement bodies and has pursued fewer major cases.

This difference in enforcement explains some of the privacy literacy gap between the UK and the EU. EU users learned through regulation that privacy is enforceable. UK users learned... less.

The research implies a policy recommendation: enforcement matters more than rules. Strong laws that aren't enforced don't change behavior. Moderate laws that are enforced change everything.

The Future of Privacy Awareness in the UK

There are small signs of change. The Online Safety Bill (becoming law in 2024-2025) will regulate tech platforms in the UK, forcing greater transparency about recommendation algorithms and content moderation. This won't directly improve privacy, but transparency requirements often increase awareness.

Gen Z shows slightly better privacy literacy than millennials. They've grown up watching privacy breaches, data harvesting scandals, and tech backlash. They're more skeptical of corporate claims. But they're also growing up in an environment where privacy has already been compromised, so their skepticism comes with resignation.

Artificial intelligence will change privacy dynamics. Behavioral data that's currently used for advertising will increasingly be used for other purposes: insurance pricing, credit decisions, employment vetting, government surveillance. This will make privacy violation consequences more obvious. When you're denied a loan because an algorithm decided you're high-risk based on your location data, the abstract privacy concern becomes concrete.

Privacy-first technology is improving. Differential privacy (a mathematical technique for adding noise to datasets to protect individuals while maintaining aggregate statistics) is becoming more practical. Federated learning (training AI models on device rather than centralizing data) is improving. Homomorphic encryption (computing on encrypted data) is becoming faster. These technologies might eventually make privacy protection easier.

But none of this happens automatically. The research suggests that privacy awareness in the UK will remain poor until either: regulation forces transparency, companies voluntarily prioritize privacy (unlikely while profiting from data), or users develop literacy (slow and unequal). The most likely scenario is a combination: growing regulation, slow education, and increasing privacy violations that make the consequences undeniable.

Moving Forward: What UK Users Can Do Right Now

The research is valuable not as an indictment but as a diagnosis. If most UK users trust the wrong apps, that's because the information environment is designed to confuse them. But armed with understanding, you can make better choices.

Start with your personal data inventory. What apps do you use? What permissions have you granted them? What data are they collecting? Most people can't answer these questions for more than 2-3 apps. Spend an hour going through every app on your phone, checking permissions, understanding what data you've given away.

Next, assess your communication. For messages with people you care about where privacy matters, use Signal. For general messaging where privacy doesn't matter, WhatsApp is fine (despite Meta's data collection, your actual messages are encrypted). For social media and public communication, accept that you have no privacy.

Implement a password manager this week. Seriously. Spend 20 minutes installing one, migrating your important passwords, and you've immediately improved your security by orders of magnitude. This is the single highest-impact thing most people can do.

Configure your phone's privacy settings. Both iOS and Android have these menus. Turn off location sharing for most apps. Turn off microphone access for everything except your phone app. Turn off contacts unless genuinely needed. Turn off photos for everything except camera and messenger apps.

Think about your threat model. Are you worried about advertising companies knowing your interests? That's easy to prevent (limit app permissions, use ad blockers). Are you worried about government surveillance? Harder to prevent but possible (strong encryption, VPN if you have jurisdiction concerns). Are you worried about your ISP tracking you? VPN helps. Most people conflate these threats and buy a VPN hoping it solves everything. Understanding what you're actually protecting yourself against improves your choices.

Finally, recognize that privacy is ultimately a social problem requiring social solutions. Individual choices matter, but they're not sufficient. We need regulation that forces transparency. We need companies that profit from privacy instead of its violation. We need cultural shifts about whether surveillance-based advertising is acceptable. The research shows that until these broader changes happen, individual privacy will remain difficult.

FAQ

What does end-to-end encryption actually mean?

End-to-end encryption means your message is scrambled on your device before it leaves, and can only be unscrambled on the recipient's device. The service provider—WhatsApp, Signal, iMessage—literally cannot read your message even if forced by law enforcement. This is different from regular encryption (like HTTPS on websites), where the company receives unencrypted data after it travels through their servers. WhatsApp's end-to-end encryption is on by default for all messages and calls.

Why should I trust Signal over WhatsApp if most people use WhatsApp?

Signal is better for privacy because it's designed solely for that purpose—the company doesn't profit from your data and has no financial incentive to compromise your security. WhatsApp is owned by Meta, which profits from personal data and behavioral targeting. However, WhatsApp's messages are encrypted so Meta can't read them specifically. The privacy difference is in what data WhatsApp collects about your usage patterns (who you talk to, when, how often), not in your message content. Both are secure for message content, but Signal respects more of your overall privacy.

Is a free VPN just as good as a paid VPN?

Not usually. Free VPNs often monetize by selling your data to advertisers—defeating the purpose of using a VPN for privacy. Some are operated by companies with questionable practices or connections to governments. Paid VPNs have revenue models that don't depend on exploiting users. However, paid VPNs still only hide your IP address. They don't protect you from website tracking if you're logged in, don't hide your activity from your ISP (if they've subpoenaed your VPN provider), and don't prevent malware. A VPN is one tool in a privacy toolkit, not a complete solution.

Should I worry about my phone's microphone being accessed without my permission?

You should be aware of it as a possibility, but practical unauthorized access is rare—it would require an app with explicit microphone permission, which most apps don't request unless needed. A bigger concern is apps that have microphone permission but use it for purposes beyond what you'd expect. Some apps record ambient noise to understand your environment without explicitly documenting it. You can't prevent this perfectly, but you can minimize it by revoking microphone access for apps that don't genuinely need it. Check your phone settings and audit app permissions regularly.

Why do companies like Meta and Google want my data if I'm not paying them?

Because your behavioral data is incredibly valuable to advertisers who will pay billions for access to it. When you're not paying money for a service, the service is monetizing something you are giving up—your attention, your behavior, your personal information. Meta doesn't charge you for Facebook or Instagram because advertisers pay Meta far more than you would pay for those services. Your attention and data are the product being sold, not the service itself. This is sometimes stated as "if you're not paying for it, you're the product."

How do I know if my data has been part of a breach?

You can check databases like Have I Been Pwned (haveibeenpwned.com) by entering your email address. If your email appears in a breach database, that means your data was compromised in that incident. If you find your email in a breach, change your password for that service and any others that use the same password. Consider enabling two-factor authentication on that account. Keep in mind that breach databases aren't comprehensive—many breaches go undiscovered or unreported, so absence from these databases doesn't mean your data is safe.

Should I turn off all location services on my phone to protect my privacy?

Turning off all location services breaks some phone functionality you might want (navigation, finding lost devices, location-based reminders). Instead, disable location access on an app-by-app basis—turn it off for every app except those that genuinely need it (maps, navigation apps, and maybe one or two others). Most apps request location permission even though they don't actually need it. In your phone settings, you can set location permissions to "while using" the app instead of always, which is more protective than allowing continuous background access.

Is Safari more private than Chrome?

Safari has better default privacy settings than Chrome out of the box. Safari doesn't track you across websites (by default) and doesn't build a profile linked to your Google account. However, Firefox (properly configured) and Brave are even more private than Safari. The key difference is that Chrome is made by Google, which benefits from tracking you. Safari is made by Apple, which benefits from selling iPhones, not from knowing what websites you visit. Your choice of browser matters, but your choice of extensions (ad blockers, tracker blockers) matters more.

Can a VPN really make me completely anonymous online?

No. A VPN hides your IP address, but it doesn't hide your identity if you're logged into accounts (email, social media, etc.). If you use a VPN to access Facebook while logged in, Facebook still knows who you are. A VPN also doesn't hide your device fingerprint—browsers can identify you through browser fingerprinting even without cookies. Complete anonymity online requires much more than a VPN. It would require using a completely separate device, separate internet connection, separate identity, separate browser profile, and careful behavior to not link yourself to your actual identity through your actions.

Key Takeaways

- British users profoundly misunderstand which apps protect their privacy and which exploit it, with many trusting data-harvesting apps while distrusting encrypted services

- Privacy concerns are high (73% say it's important) but action is low (8% have taken actual steps), revealing a significant knowledge gap

- End-to-end encryption is widely misunderstood, with most users assuming it means companies might access their data later rather than understanding it prevents access entirely

- VPNs have become a false privacy solution, with most users employing them to access blocked content rather than protect data, and misunderstanding what they actually protect

- Regional variations show privacy awareness is highest where regulation is strong (Scandinavia) and enforcement is active, suggesting policy and education matter more than individual choices

- Password practices are dangerously poor, with 61% of UK users reusing passwords across sites, while only 12% use password managers

- Brand trust consistently overrides data literacy, with people's assessment of app trustworthiness changing dramatically when the company name is revealed

- Privacy protection requires understanding your actual threat model and using appropriate tools for each threat, rather than assuming one solution solves everything

- Real privacy strategy involves encrypting sensitive communication, using a password manager, enabling two-factor authentication, controlling app permissions, and accepting that public platforms offer no privacy

- The UK is behind other developed nations in privacy literacy due to weaker regulation and enforcement compared to the EU, suggesting policy changes could meaningfully improve awareness

Conclusion: From Confusion to Understanding

The Proton research delivers a clear message: UK privacy is paradoxical. People care, but they don't understand what privacy actually means or how to achieve it. They take actions that feel protective but provide limited benefit. They trust the wrong apps because they've internalized marketing messages instead of data reality.

But this isn't a permanent condition. Privacy literacy is teachable. The data proves it. Users in regions with stronger regulation understand privacy better. Users who take time to understand encryption and threat models make better choices. Users with access to better defaults (like Apple's privacy messaging or Firefox's privacy focus) end up more protected even if they don't fully understand why.

The path forward has multiple components. Technology companies that profit from data collection will never voluntarily educate users about privacy unless forced by regulation. Policymakers need to continue strengthening UK privacy law and enforcement. Educators need to incorporate digital literacy into school curricula. Users need to recognize that privacy is their responsibility and that the information environment is actively designed to confuse them.

Most immediately, if you're a UK user, audit what you're actually sharing with whom. Understand that TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook are advertising companies that harvest behavioral data, not entertainment platforms that happen to show ads. Understand that WhatsApp, Signal, and iMessage keep your message content private from the company itself. Understand that a VPN only hides your IP address. Understand that your password reuse is your biggest personal security vulnerability.

Privacy isn't binary. You don't need to choose between total privacy (which is impossible) and total exposure (which most people have). You need to choose a privacy level that matches your threat model, understand what tools actually protect against what threats, and implement a consistent strategy rather than random security theater.

The research shows most UK users haven't made this choice. They're stuck in confusion, trusting apps they shouldn't and distrusting apps they should trust. But understanding the confusion is the first step toward moving beyond it. Now that you know why British users trust the wrong apps, you can decide not to be one of them.

Related Articles

- Encrypt Your Windows PC Without Sharing Keys With Microsoft [2025]

- I Tested a VPN for 24 Hours. Here's What Actually Happened [2025]

- Best VPN Under $3/Month: Advanced Features for Less [2025]

- Best VPN Services 2025: Tested, Reviewed, and Ranked [2025]

- Panera Bread Data Breach: 14 Million Records Exposed [2025]

- Windscribe VPN Review: Security, Speed, and Quirky Design [2025]

![Why Brits Fear Online Privacy But Trust the Wrong Apps [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-brits-fear-online-privacy-but-trust-the-wrong-apps-2025/image-1-1769686576870.jpg)