The Day Microsoft Handed the FBI the Keys to Your Encrypted Data

It happened quietly. No press release. No warning to customers. Last year, the FBI showed up at Microsoft's door with a warrant, asking for something most tech companies have historically resisted with every ounce of their corporate legal firepower: encryption keys. Microsoft handed them over.

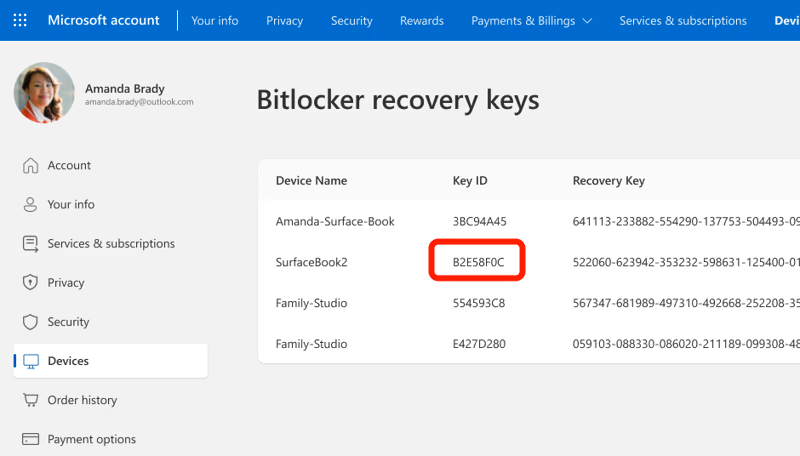

The case involved three laptops in Guam, tied to an investigation into potential fraud involving COVID unemployment assistance. But here's the thing that keeps privacy advocates awake at night—this wasn't some extraordinary exception or a one-time anomaly. Microsoft confirmed to Forbes that it "does provide BitLocker recovery keys if it receives a valid legal order." Translation: if you're using Windows and you've chosen Microsoft's cloud storage for your encryption keys, the company will hand them over to the government whenever it gets a warrant.

This is a seismic shift in how the world's largest software company thinks about user privacy. And it's different from anything we've seen before in the tech industry.

Let me explain why this matters. Encryption isn't theoretical—it's the difference between your private messages staying private and your bank account details sitting in a government folder. For years, major tech companies have taken a hardline stance on this issue. Apple famously refused to help the FBI crack into the San Bernardino shooter's iPhone in 2016, triggering a showdown that lasted months. Google and Facebook backed Apple. Microsoft initially supported that position too, even if less vocally than some others.

But that was then. This is now.

Understanding BitLocker: What's Actually Happening Here

Before we get into the implications, let's understand what BitLocker is and why Microsoft's decision matters so much.

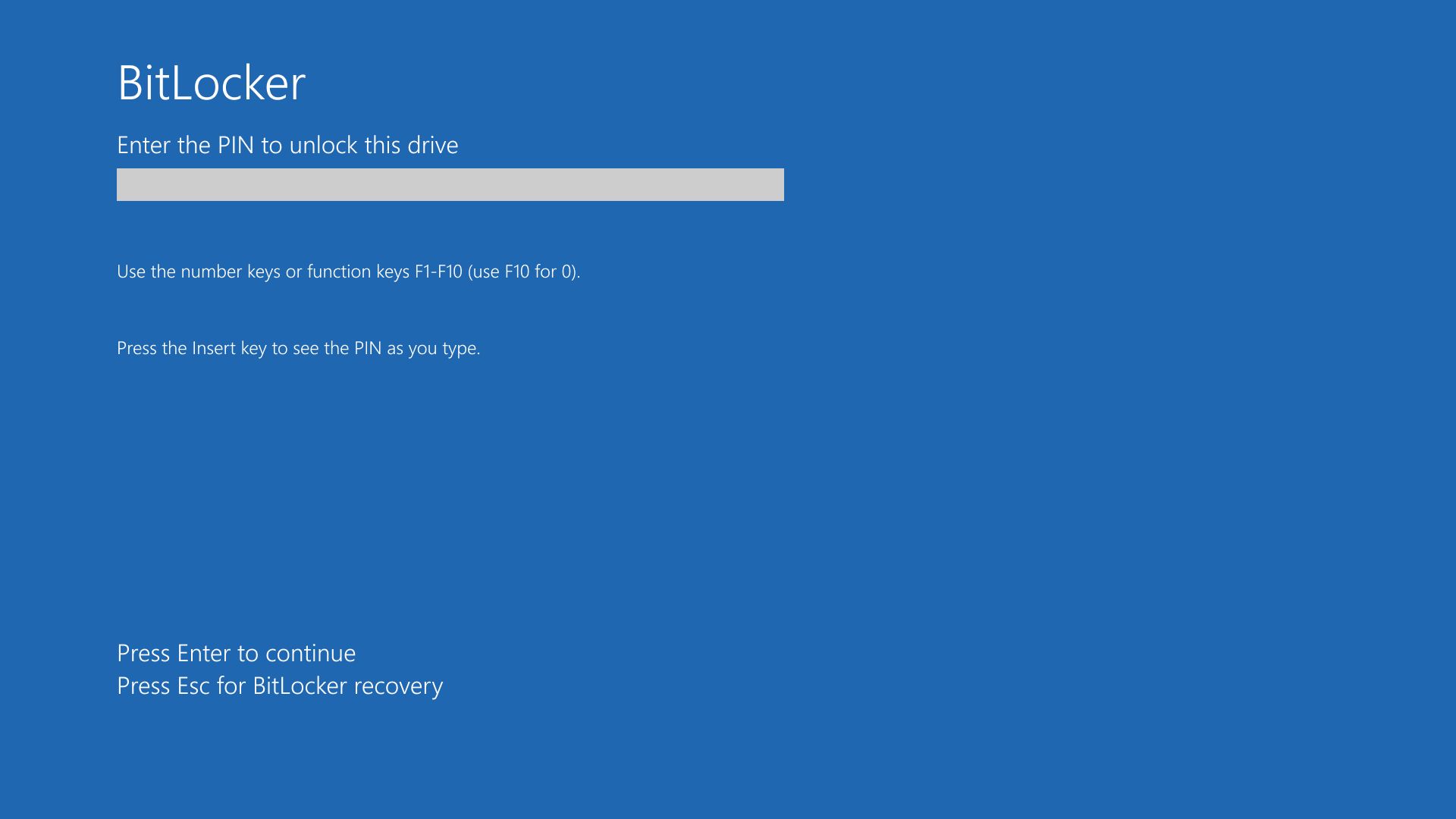

BitLocker is Windows' built-in full-disk encryption tool. It's not some niche security feature—it ships with Windows Pro, Enterprise, and Education editions. If you're using Windows 10 or 11 on a work laptop, BitLocker is probably encrypting your hard drive right now.

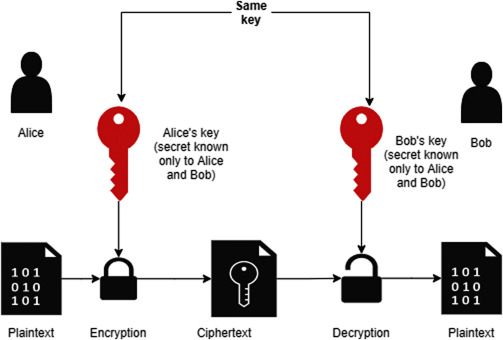

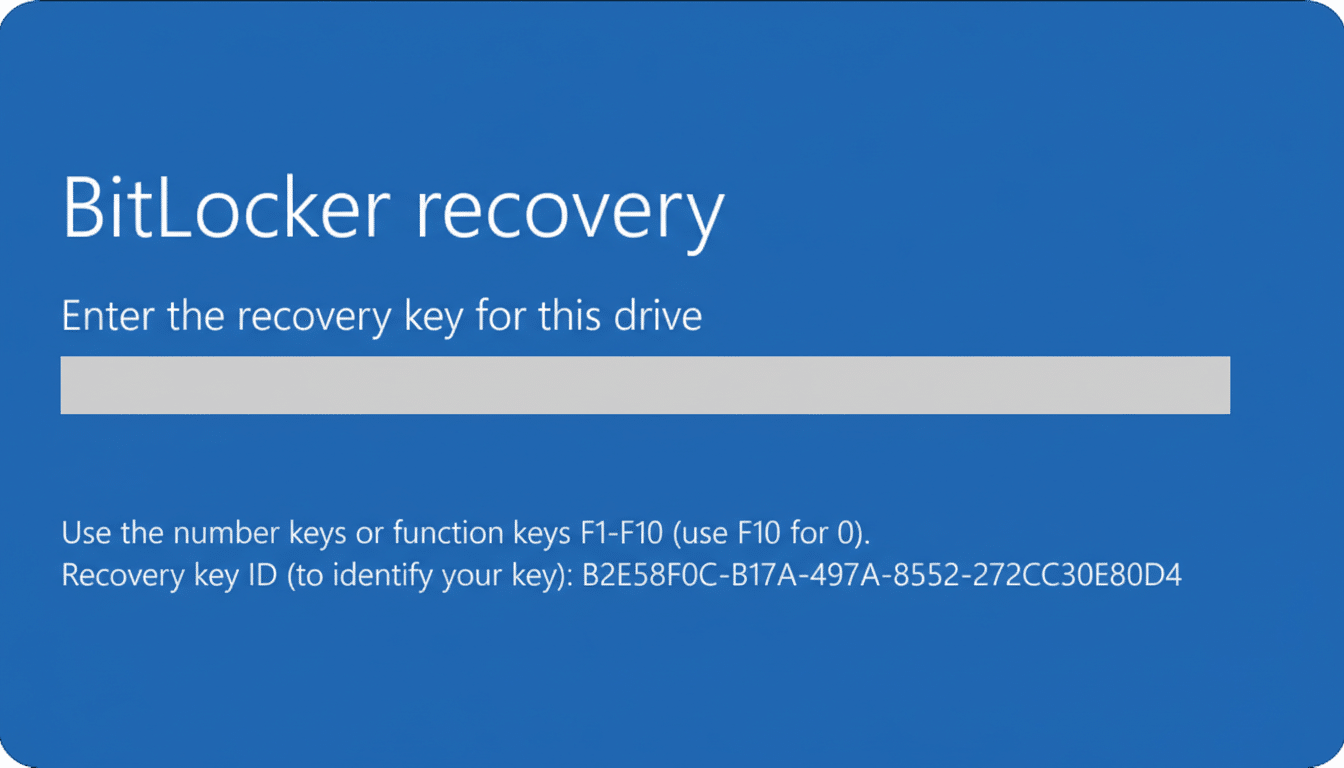

Here's how it works: when you enable BitLocker, it generates an encryption key. This key is mathematically complex—essentially a massive number that would take longer than the age of the universe to guess through brute force. Without this key, your hard drive is useless. Even if someone steals your laptop and removes the drive, the data is just unreadable noise.

The problem is that encryption keys need to be stored somewhere. You can't just carry them in your head. Microsoft offers customers two options: store the key locally on your device (where Microsoft can't access it), or store it in Microsoft's cloud (where Microsoft can access it, and apparently, will give it to the government).

Most users don't think about this choice. They either don't know it exists, or they choose Microsoft's cloud storage because it's convenient. If you lose your password, if your device crashes, if you forget your PIN—cloud storage means you can recover your encrypted data. No key stored in the cloud means you're locked out forever. That's not a trivial problem.

So Microsoft created a recovery option. They keep a copy of your encryption key in their servers. You can retrieve it if you need it. Convenient.

Turns out, the FBI can retrieve it too.

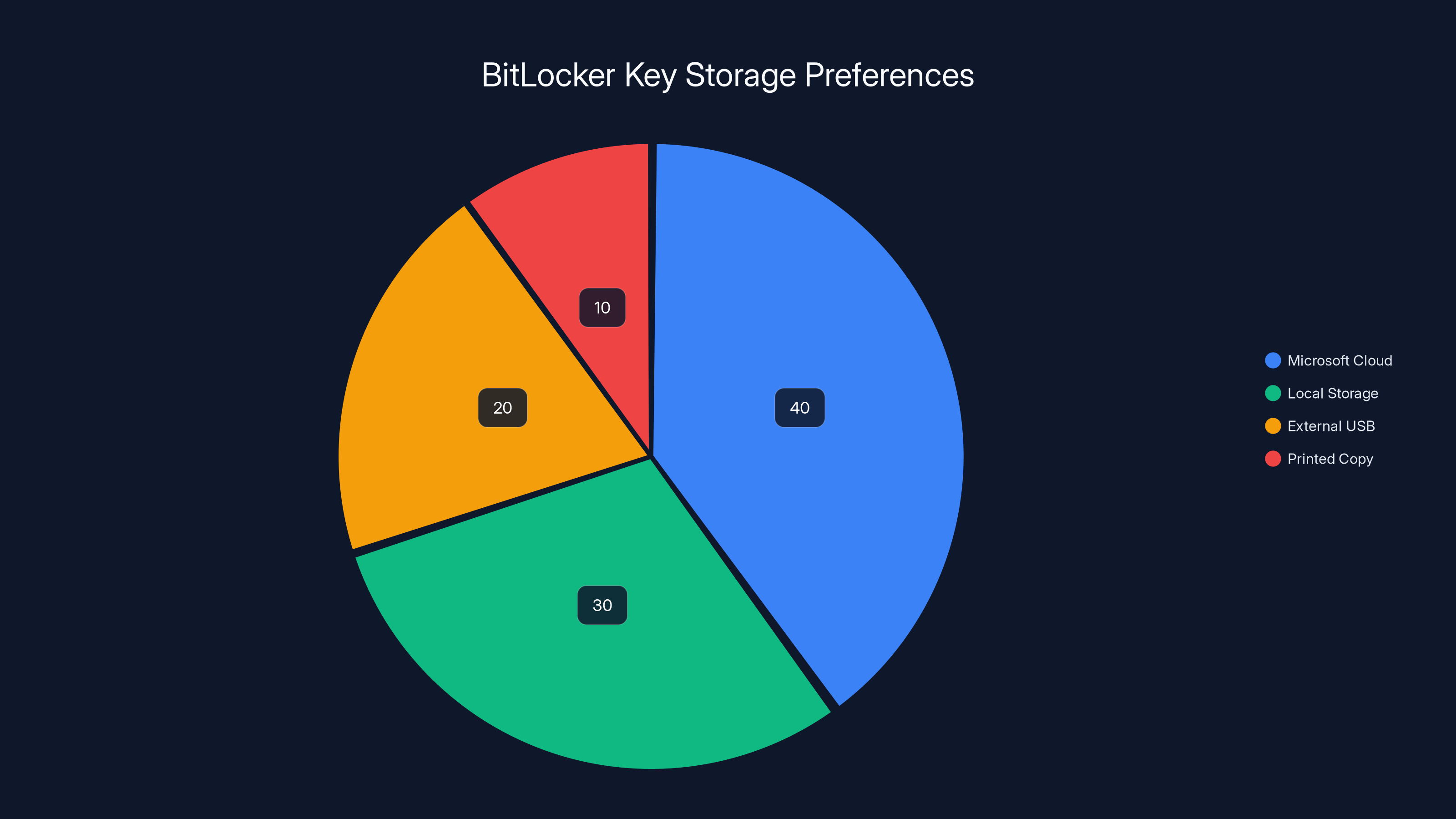

Estimated data shows that 40% of users store their BitLocker recovery keys in Microsoft's cloud, while 30% prefer local storage, 20% use external USB drives, and 10% opt for printed copies.

The Legal Framework: How Warrants Actually Work

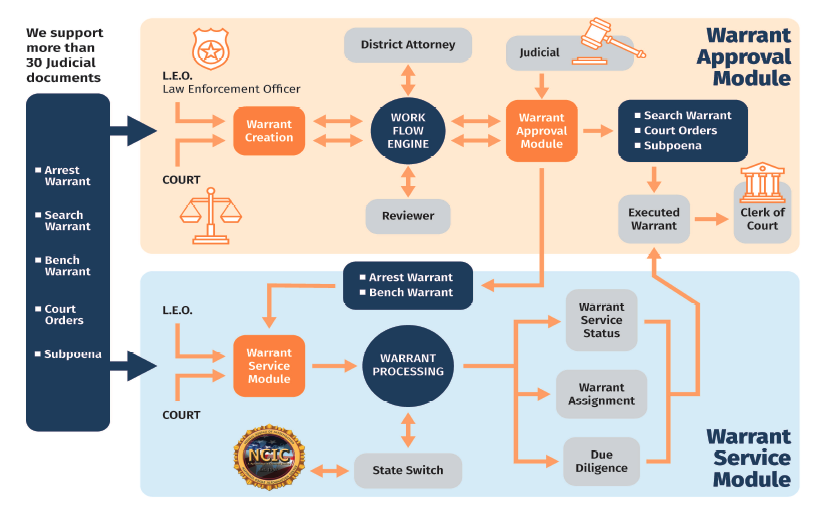

Microsoft's spokesperson Charles Chamberlayne told The Verge that the company is legally required to produce the keys when presented with a valid legal order. This is technically true, but it obscures a more important question: what does "valid" actually mean?

When law enforcement wants access to customer data, they don't just ask nicely. They go to a judge and request a warrant. The Fourth Amendment theoretically protects Americans from unreasonable searches and seizures. A warrant is supposed to be the mechanism that ensures law enforcement isn't just fishing through your private data on a whim.

However, warrants have become increasingly easy to obtain. The legal standard is low: law enforcement needs to show "probable cause" that a crime has occurred and that the search will turn up evidence. "Probable cause" is looser than it sounds. It doesn't mean "we're pretty sure." It means something closer to "we have a reasonable basis to believe."

In the Guam unemployment fraud case, law enforcement apparently met that standard. The FBI said it needed access to data on three specific devices to investigate potential fraud. A judge agreed. Microsoft complied.

But here's where it gets concerning. The fact that a warrant exists doesn't mean the warrant was appropriate, thorough, or narrowly scoped. A warrant for "all data on three laptops" is vastly different from a warrant for "correspondence related to unemployment claims from January 2021." One is a fishing expedition. The other is targeted.

We don't know the specifics of the Guam warrant. But the concern from privacy advocates isn't really about that particular case. It's about the precedent.

The Precedent Problem: Why This Decision Matters Globally

Jennifer Granick, surveillance and cybersecurity counsel at the ACLU, made a stark observation to Forbes: "Foreign governments with questionable human rights records" may now expect Microsoft to hand over encryption keys to customer data.

This is the real nightmare scenario. The United States government, despite its flaws, operates within a constitutional framework with some checks and balances. If the FBI acts egregiously, citizens can sue. Congressional oversight exists. The judiciary can push back.

Many other governments have no such limitations.

Consider authoritarian regimes that use data access to crack down on political dissidents. Or countries where "national security" is an excuse for investigating anyone the government doesn't like. Once you establish that Microsoft will hand over encryption keys to any government with a warrant, you've created a template.

China's government can get a warrant. Russia's government can get a warrant. Hungary's government can get a warrant. Venezuela's government can get a warrant.

All of them can now point to Microsoft's decision in the U.S. and say: "You did it for America. You'll do it for us too."

This is why Senator Ron Wyden called it "irresponsible" for companies to "secretly turn over users' encryption keys." The word "secretly" is crucial here. Most users didn't know this could happen. Microsoft didn't publicize the fact that it would hand over encryption keys to law enforcement. It only acknowledged this policy when Forbes asked directly.

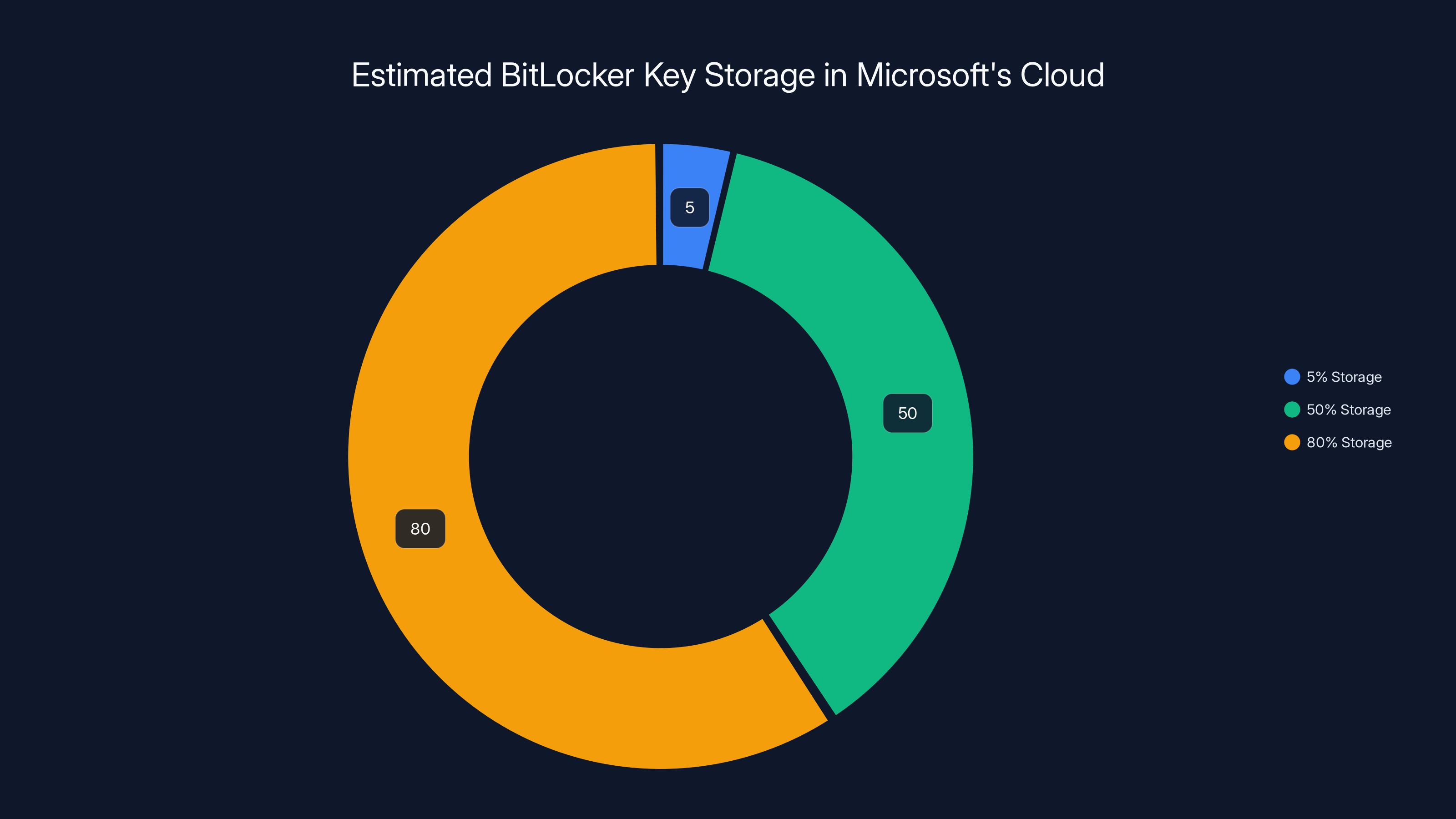

Estimated data shows potential distribution of BitLocker users storing recovery keys in Microsoft's cloud, highlighting the impact of different storage levels on user privacy.

The Bigger Context: Current Administration and ICE

The timing of this revelation is worth considering. Privacy advocates like the ACLU have noted that the current administration and ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) have shown what they characterize as "little respect for data security or the rule of law."

This isn't partisan rhetoric. It's documented concern. ICE has a history of mass data collection, including accessing location data without warrants, collecting DNA without consent, and accessing driver's license photos without authorization. If you're an immigration enforcement agency with a questionable track record on civil liberties, and suddenly you can get warrants for encryption keys, that's a powerful new tool.

Consider what could happen: an immigration officer could potentially obtain encryption keys to access communications and documents of someone suspected of being undocumented. Or a dissident whose family members are in another country. Or anyone the administration deems a security threat.

The concern isn't abstract. Data access has real consequences for real people.

Apple's Stand vs. Microsoft's Collapse: A Tale of Two Tech Giants

The contrast is stark. In 2016, Apple refused the FBI's demands to create a backdoor into the San Bernardino shooter's iPhone. Tim Cook made a public stand. He wrote about it. He fought. Other tech companies backed him up.

Nine years later, Microsoft is handing over the digital equivalent without much public acknowledgment.

Why the difference? There are a few theories. Apple sells consumer devices and has built much of its brand identity around privacy. The San Bernardino case was high-profile and put Apple in the position of defender of civil liberties. That's marketing gold.

Microsoft is different. It's primarily an enterprise company. Windows is used by governments, corporations, and organizations worldwide. Taking a hardline stance against government data access could cost them contracts. When the FBI comes calling, they're not just a customer—they're potentially a major customer.

There's also a technical difference. BitLocker recovery keys are something Microsoft stores centrally. Creating a backdoor in encryption technology is different from handing over something you already have. One feels proactive (creating a security vulnerability). The other feels reactive (complying with a warrant).

But this distinction matters less than the outcome. Both scenarios result in law enforcement getting access to encrypted data.

The Technical Reality: Why "Cloud Storage" Is the Problem

Microsoft's statement that "customers can choose to store their encryption keys locally" is technically true but practically misleading. Yes, you can choose. But how many Windows users actually know this option exists? How many understand what it means?

The default behavior for most users is cloud storage. It's convenient. It works. It takes no technical knowledge.

Choosing local-only storage requires knowing the option exists, understanding the implications, and being comfortable with the idea that if you lose your password, your data might be permanently inaccessible.

This is a classic security vs. usability tradeoff. Microsoft chose the side that generates less customer support calls. But it also chose the side that makes government data access easier.

There's a deeper issue here too. The existence of the recovery key itself is a vulnerability. Even if stored locally, the key exists somewhere on your device. The very act of generating a recovery mechanism creates a potential point of failure. Some security experts argue that truly secure encryption shouldn't have any recovery option. If you lose the key, the data is gone forever. That's the price of security.

But for consumer products, that's unacceptable. Users forget passwords. Devices fail. People move on from old devices. The ability to recover access is a necessary feature, not a bug.

Microsoft found a middle ground: generate recovery keys that let users regain access without giving Microsoft (or anyone else) the ability to access their data. Then it decided to also store copies of those keys in its own servers.

That decision has come back to haunt them.

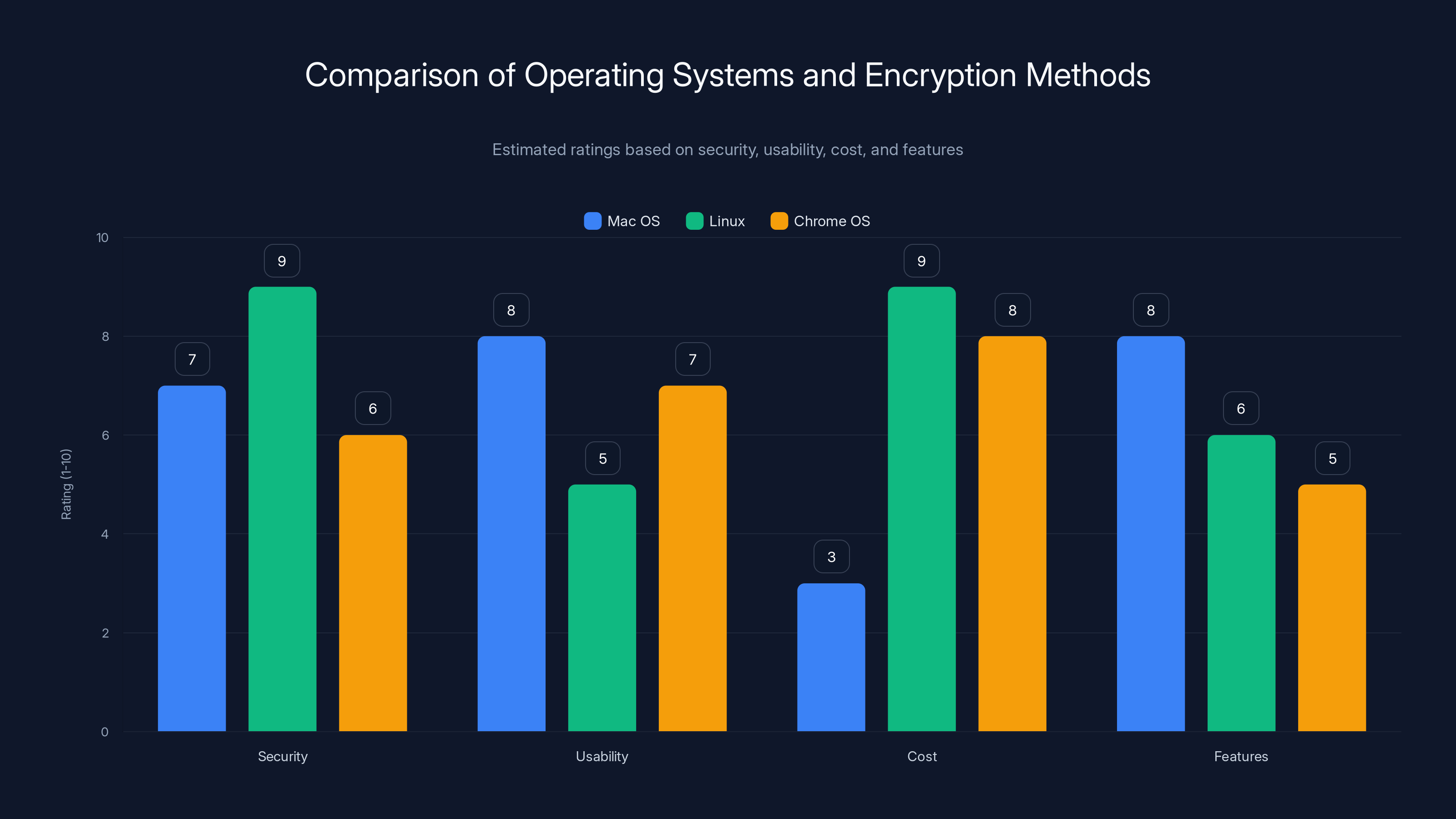

Estimated data shows Linux as the most secure but less user-friendly. Mac OS offers a balance of usability and features, while Chrome OS is cost-effective but limited in functionality.

What We Don't Know: The Information Gap

Here's what's frustrating about this entire situation: we don't know the details. We know Microsoft handed over BitLocker recovery keys to the FBI in at least one case. We don't know:

How many times this has happened. Microsoft hasn't disclosed the number of key handovers to law enforcement. It could be dozens, or it could be hundreds. We're flying blind.

What the warrants actually said. Were they narrowly scoped? Or did law enforcement ask for broad access? The specifics matter enormously for evaluating whether this was an appropriate use of government power.

What percentage of BitLocker users store keys in Microsoft's cloud. If it's 5%, that's one impact. If it's 80%, that's another. We don't have this data.

Whether other companies do the same thing. Does Google hand over Chrome OS encryption keys? Does Apple hand over iCloud encryption keys? We don't know, because companies don't volunteer this information.

This information gap itself is a problem. Users can't make informed decisions about where to store their data if they don't understand the risks. Companies can hide behind "we comply with legal orders" without being transparent about how often that happens or under what circumstances.

The Transparency Paradox: Why Companies Don't Talk About This

Companies hate talking about government data requests. It's bad for business. It makes customers nervous. It raises uncomfortable questions about what governments are really doing with access to private data.

Microsoft only acknowledged its BitLocker key handover policy when Forbes specifically asked about it. If Forbes hadn't asked, we might never have known.

This is why privacy advocates push for transparency reports. Companies like Google, Apple, and Microsoft publish annual reports on government data requests. But even these reports are limited. Companies report the number of requests, but not usually what happened with those requests or how successful they were at accessing data.

The result is a fog of opacity. Users are left guessing. Privacy advocates are left speculating. Journalists are left chasing rumors.

Meanwhile, government agencies are quietly using legal tools to access data that users thought was secure.

The Encryption Debate: A War Without Resolution

Microsoft's decision sits at the center of one of the most contentious debates in technology policy: should encryption have backdoors for law enforcement?

Law enforcement says yes. They argue that encryption prevents them from investigating crimes. If a suspected terrorist's laptop is encrypted, and the terrorist won't give up the password, law enforcement has no way to access evidence. They want tech companies to build backdoors—tools that let authorized law enforcement access encrypted data.

Cryptographers and privacy advocates say absolutely not. They argue that any backdoor that law enforcement can use, criminals and foreign governments can eventually exploit. Strong encryption is like a lock that only works one way. Once you add a backdoor, you've weakened the lock for everyone.

Microsoft's decision doesn't directly address this debate. BitLocker doesn't have a backdoor. But by storing recovery keys in its cloud, Microsoft created something almost as useful to law enforcement—a central repository of keys that can be accessed with a legal order.

It's a clever workaround to the encryption debate. No backdoor in the encryption itself. Just convenient key storage that happens to be accessible to the government.

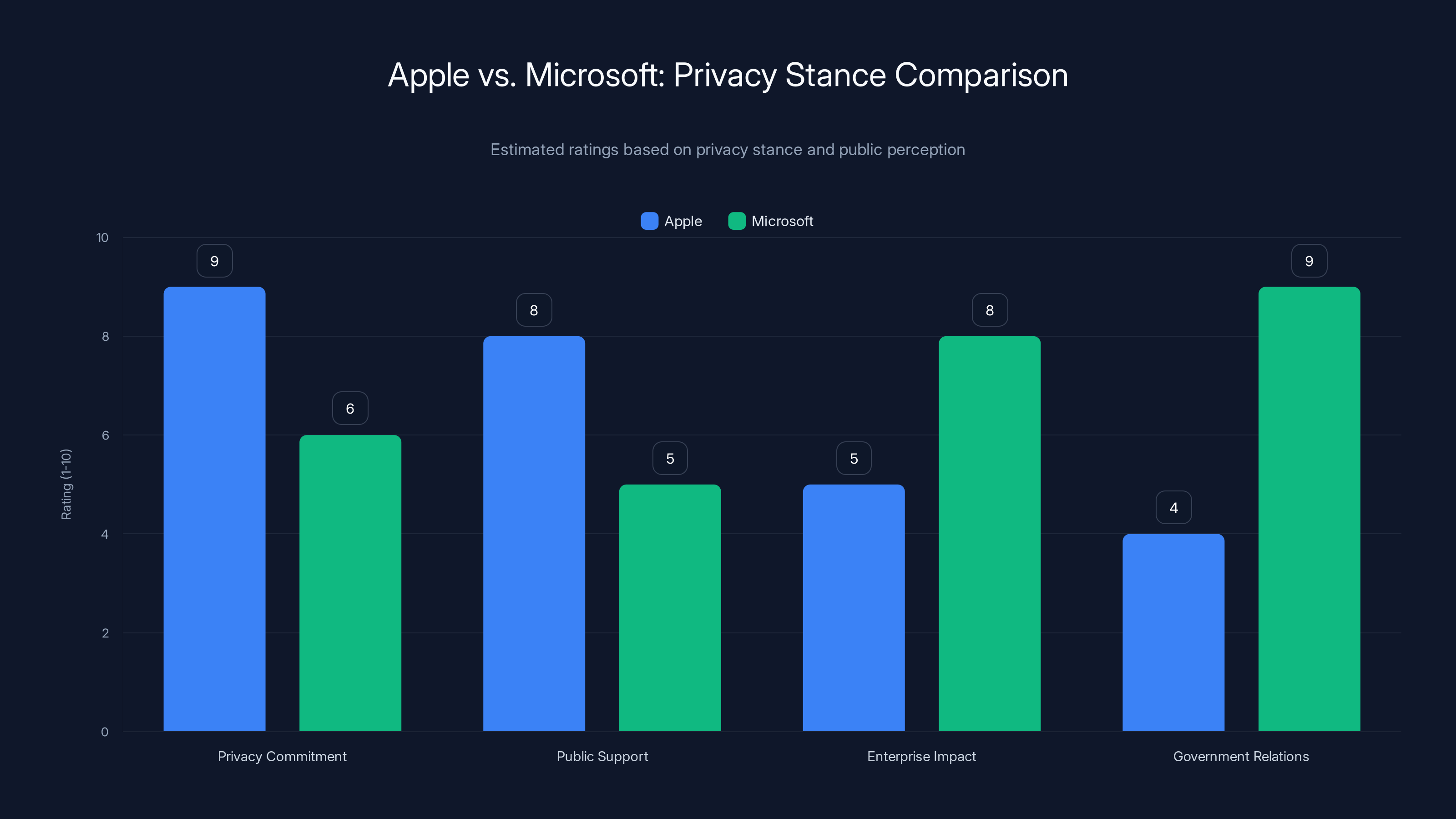

Apple scores higher in privacy commitment and public support, while Microsoft excels in enterprise impact and government relations. Estimated data based on company actions and public perception.

International Implications: The Global Privacy Collapse

Microsoft is a global company. Windows is used in virtually every country. BitLocker is a global service.

If Microsoft hands over encryption keys to the U.S. government, what stops other governments from demanding the same?

This isn't theoretical. The European Union has been pushing for encryption backdoors under the guise of "combating child exploitation." China explicitly requires backdoors for government surveillance. Russia has laws requiring companies to store data locally and provide access to security services.

Once you establish that encryption keys can be handed over to government, you've given every government a precedent to work with. Even if Microsoft wanted to refuse some governments, they'd struggle to justify it. "We hand over keys to the FBI but not to your security service" invites accusations of bias, selective compliance, or political favoritism.

The practical result? Most governments will likely demand equal treatment. Microsoft will have to choose: hand over keys to everyone, or hand over keys to no one.

Given that they've already started handing over keys to the U.S. government, they've likely made their choice.

What This Means for Regular Users: The Practical Impact

If you're a Windows user, what should you do?

First, understand your options. When you enable BitLocker, you can choose where to store your recovery key. Microsoft will store it in the cloud by default, making it accessible to law enforcement with a warrant. You can choose to store it locally instead, writing it down and keeping it somewhere safe, or saving it to an external drive.

Second, consider your threat model. If you're primarily worried about ordinary criminals stealing your laptop, cloud key storage is probably fine. If you're worried about government surveillance—whether because of your activism, your nationality, your immigration status, or your work—local key storage is better.

Third, be aware that choosing local storage carries risks. If you lose the key and forget your password, your data might be permanently inaccessible. There's no recovery option. This is the price of security.

Fourth, consider using third-party encryption tools on top of BitLocker. Something like VeraCrypt or encrypted containers can provide an additional layer of encryption that Microsoft doesn't have keys to. This is more cumbersome but offers stronger privacy guarantees.

Fifth, think about what data you're actually encrypting. Full-disk encryption protects everything on your drive. If you only need to protect sensitive files, you might consider encrypting just those files rather than the entire disk.

The Alternatives: Other Operating Systems and Encryption Methods

If Windows makes you uncomfortable, what are your alternatives?

Mac OS includes FileVault, Apple's disk encryption system. But Apple also stores recovery keys, and Apple has a documented history of complying with law enforcement requests, though they've been more privacy-conscious than Microsoft in recent years.

Linux doesn't include built-in disk encryption in the same way, but you can use tools like LUKS (Linux Unified Key Setup) for full-disk encryption. The advantage here is that you control the keys entirely—no company stores them in the cloud.

Chromebooks use Chrome OS, which has different encryption approaches depending on whether you're using your work account or personal account. Enterprise Chrome OS devices may also have recovery keys accessible to administrators.

The hard truth is that choosing a more secure operating system comes with tradeoffs. Linux requires more technical knowledge. Macs are expensive. Chrome OS is limited in functionality.

There's no perfect solution. Every operating system represents a compromise between security, usability, cost, and features.

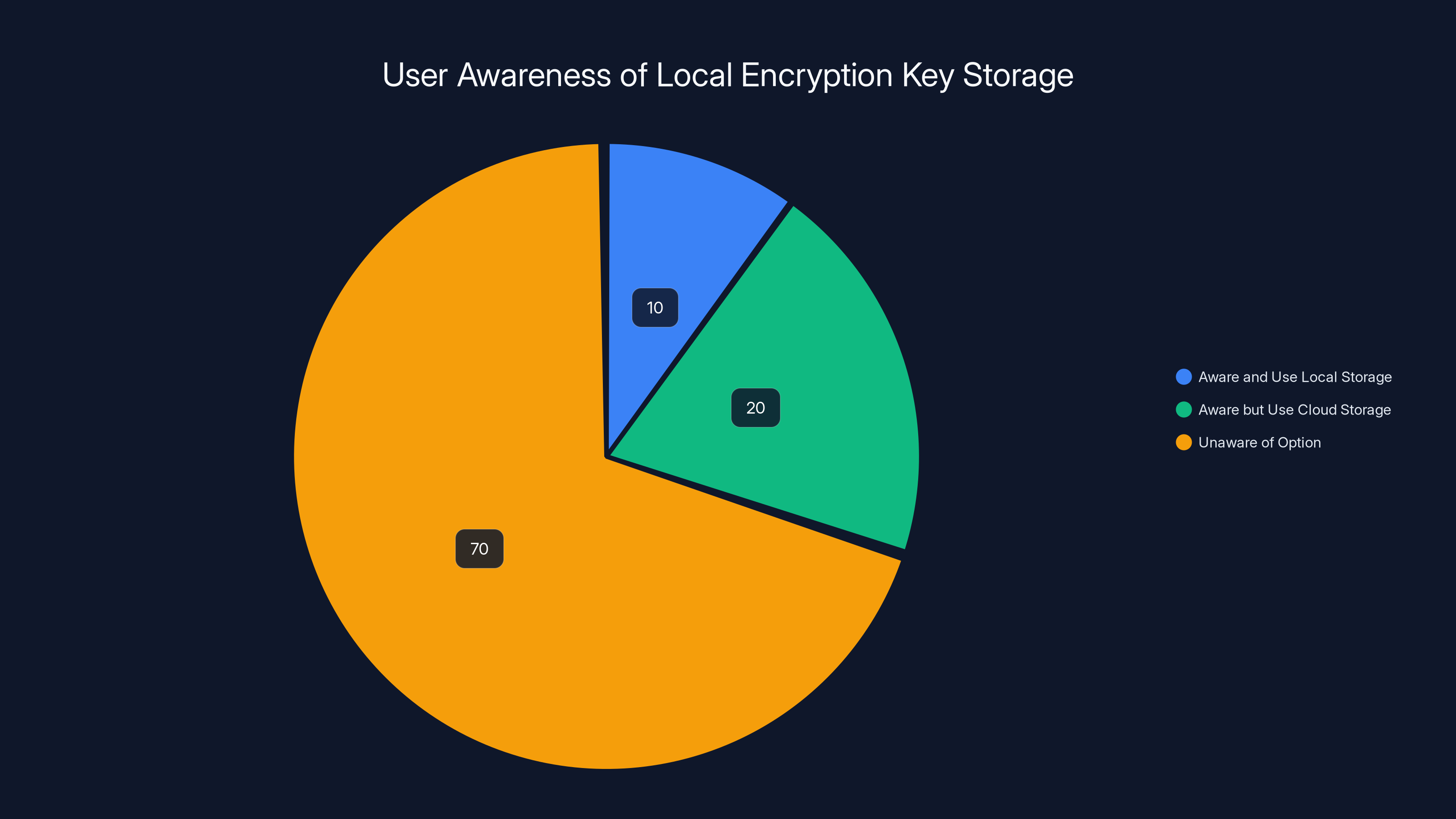

Estimated data suggests that a majority of users (70%) are unaware of the option to store encryption keys locally, highlighting a significant gap in user knowledge and preference for cloud storage.

Corporate and Enterprise Implications: A Nightmare for Sensitive Data

For enterprises, this revelation has serious implications. Many corporations use Windows and BitLocker for sensitive data. They assume that encryption keeps data private from law enforcement.

Now they know that assumption is wrong.

A corporation processing customer data, trade secrets, or proprietary research might have assumed that BitLocker provided ironclad protection. If they're storing BitLocker recovery keys in Microsoft's cloud (which many do, for convenience), then law enforcement can access that data with a warrant.

For companies in regulated industries—finance, healthcare, legal—this could have compliance implications. If regulations require that sensitive data be protected with encryption that only the company can access, then cloud-stored recovery keys might violate those requirements.

For companies operating internationally, the implications are even worse. If data stored in the U.S. can be accessed by the U.S. government, and the company has customers in Europe, that violates GDPR (the European General Data Protection Regulation), which restricts where customer data can be stored and who can access it.

The upshot: enterprises need to audit their BitLocker deployments and verify where recovery keys are stored. If they're in Microsoft's cloud, companies might need to change their policies to require local-only key storage.

The Security Industry's Response: Quiet Disappointment

Security researchers haven't erupted in outrage—at least not publicly. Most have been relatively measured in their response.

Part of this is because the situation is legally and technically complex. Microsoft isn't technically creating a backdoor or weakening encryption. It's complying with a legal process to provide something it already has access to.

But part of it is also resigned acceptance. Security experts have long known that any key recovery mechanism is a potential vulnerability. They've warned about this for years. The fact that Microsoft would eventually hand over recovery keys to law enforcement wasn't surprising—it was inevitable.

The debate in security circles is now focused on whether key recovery is worth the risk. Is convenience—being able to recover access if you forget your password—worth the possibility of government access?

For consumer products, most experts think yes. People will lose passwords. They'll have hardware failures. They'll forget PINs. Some recovery mechanism is necessary.

But for high-security environments, the answer is no. If you're protecting state secrets, trade secrets, or information that could get people killed, convenience doesn't matter. Security does. And that requires accepting that if you lose the key, the data is gone forever.

The Legislative Response: What Congress Isn't Doing

You'd expect that a revelation like this—a major tech company handing encryption keys to the government—would trigger legislative action.

It hasn't. Congress remains divided on encryption policy. Some members want to mandate backdoors so law enforcement can access encrypted data more easily. Others want to protect encryption from government interference. Most just don't understand the issue well enough to have a strong position.

Senator Ron Wyden called Microsoft's actions irresponsible, but he's one voice. Most of Congress is silent.

This silence is its own kind of answer. Without legislative protection, companies like Microsoft will make their own decisions about government data access based on legal compliance and business considerations. The result is decisions that favor law enforcement convenience over user privacy.

If you believe encryption should be protected from government backdoors, you probably want Congress to pass legislation that explicitly protects it. If you believe law enforcement needs access to encrypted data, you might want legislation that mandates cooperation from tech companies.

Instead, we're getting neither. We're getting the worst outcome: no clear rules, so companies make decisions in a vacuum, usually tilting toward law enforcement to avoid conflict.

The Future of Encryption: Where We're Headed

Look at the trends and it's hard not to be pessimistic about privacy.

Governments worldwide are pushing for encryption backdoors or key recovery mechanisms. Tech companies are, by and large, complying. Users don't understand the implications and can't be expected to make sophisticated security decisions.

The likely future is one where encryption exists, but the government has keys to everything. We'll have the appearance of privacy without the reality of it.

Some jurisdictions might go further. The European Union, under pressure from law enforcement, might mandate that tech companies build mechanisms to allow rapid decryption on demand. This would effectively eliminate strong encryption as a practical matter.

Other jurisdictions might embrace encryption as a tool of surveillance. China's government already requires backdoors in encryption. Russia is moving in that direction. Eventually, we might see a world where "strong encryption" is something only governments possess, while ordinary citizens have encryption that's accessible to their own government and potentially others.

The alternative future—one where encryption is truly private, with no government keys, no recovery mechanisms, no backdoors—seems less likely with each passing year.

Microsoft's decision to hand over BitLocker keys is a step down the first path. It's a small step, but it's a step toward a future where privacy is negotiable.

Key Takeaways and Calls to Action

So what's the bottom line here?

Microsoft stores BitLocker recovery keys in its cloud. It handed over keys to the FBI when presented with a warrant. This is legal, but it represents a significant privacy risk.

If you use Windows and care about privacy, you should consider storing BitLocker recovery keys locally instead of in Microsoft's cloud. This makes key recovery inconvenient but eliminates Microsoft's ability to hand over your keys.

If you're an enterprise, you should audit your BitLocker deployment and consider whether cloud key storage aligns with your security policies.

If you care about privacy broadly, you should be aware that this is how the system works. Tech companies comply with legal orders. Without legal protections for encryption, companies will hand over keys whenever the government asks.

The solution isn't to blame Microsoft or demand that they defy the law. They're complying with legal warrants. The solution is legislation that protects encryption as a fundamental tool for privacy, limiting government access even through legal mechanisms.

Until that happens, assume that any encryption key stored with a company can be accessed by law enforcement. Plan your security accordingly.

FAQ

What is BitLocker and how does it protect my data?

BitLocker is Windows' built-in full-disk encryption technology that encrypts everything on your hard drive using a complex mathematical key. Without the correct key, your data is unreadable and inaccessible, even if someone physically steals your device. It's enabled by default on Windows Pro, Enterprise, and Education editions and provides protection against unauthorized access to your files, passwords, and personal information.

Can I prevent Microsoft from accessing my BitLocker recovery key?

Yes, you can store your BitLocker recovery key locally on your device or on external storage instead of in Microsoft's cloud. When you set up BitLocker, you're given the option to save your recovery key to a file, print it, or store it on an external USB drive. This prevents Microsoft from having access to your key, though it means you're responsible for keeping that key safe and secure.

How does the government obtain encryption keys with a warrant?

Law enforcement can obtain a warrant from a judge by demonstrating probable cause that a crime has been committed and that evidence of that crime exists on a specific device. When Microsoft receives a valid warrant, it's legally required to comply and provide the requested encryption keys if they're stored on Microsoft's servers. The warrant process is supposed to provide judicial oversight, though critics argue that the standard for issuing warrants is often too low.

What does this mean for my privacy if I store files on Microsoft OneDrive or other cloud services?

If you store files encrypted with BitLocker and the recovery key in Microsoft's cloud, law enforcement can potentially access that key with a warrant and decrypt your files. However, if you use end-to-end encryption where only you have the key, Microsoft's cloud storage can't help law enforcement decrypt your files. The difference depends on what type of encryption and key storage you've chosen.

Are other operating systems like Mac or Linux safer from government data access?

Mac and Linux have their own encryption tools and vulnerabilities. Apple's FileVault also stores recovery keys and likely complies with government warrants. Linux distributions using LUKS encryption give users more control over key storage, but security ultimately depends on where you choose to store your keys. No operating system is immune to legal processes like warrants, though some give users more control over key location than others.

Should I stop using Windows because of this?

Not necessarily, but you should be aware of your options. If you use Windows, you can choose to store BitLocker keys locally instead of in Microsoft's cloud. This eliminates Microsoft's ability to hand over your keys but requires you to manage those keys carefully. The choice depends on your specific threat model and whether the potential privacy risk outweighs Windows' convenience and compatibility for your use case.

What can companies do to protect customer data from government access?

Companies should audit where their encryption keys are stored and migrate sensitive keys to local storage rather than cloud storage. They should also implement additional layers of encryption beyond operating system encryption, use end-to-end encryption where applicable, and maintain clear data retention and access policies. For highly sensitive data, some organizations use on-premises encryption tools that the company, not a cloud provider, controls completely.

How often does Microsoft actually hand over BitLocker keys to law enforcement?

Microsoft hasn't publicly disclosed how many times it has complied with key requests. The company publishes general transparency reports on government data requests, but these don't specifically break down BitLocker key handovers. This lack of transparency makes it impossible for users to understand how frequently this access occurs or under what circumstances.

Is encryption with a recovery mechanism less secure than encryption without one?

Yes, technically. Encryption without any recovery mechanism is theoretically more secure because there's no pathway to access the data if you lose the key. However, recovery mechanisms are practically necessary for consumer devices because people forget passwords and devices fail. The question becomes where the recovery key is stored and who has access to it. Keys stored locally in your control are more secure than keys stored on company servers.

What should I do if I'm concerned about government surveillance?

Start by understanding where your encryption keys are stored and who has access to them. Move BitLocker keys to local storage. Consider using additional encryption layers beyond operating system encryption for highly sensitive data. Be aware that even strong encryption can be undermined if your device is compromised or if you're compelled to surrender your password. For maximum privacy, assume that any data stored with a company can be accessed by government with a legal order.

Related Articles

- TikTok's Immigration Status Data Collection Explained [2025]

- Microsoft BitLocker Encryption Keys FBI Access [2025]

- Smart Device End-of-Life Disclosure: Why Laws Matter [2025]

- Jen Easterly Leads RSA Conference Into AI Security Era [2025]

- Why "Catch a Cheater" Spyware Apps Aren't Legal (Even If You Think They Are) [2025]

- Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]

![Microsoft Handed FBI Encryption Keys: What This Means for Your Data [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-handed-fbi-encryption-keys-what-this-means-for-you/image-1-1769295950927.jpg)