Government Censorship of ICE Critics: How Tech Platforms Enable Suppression [2025]

Imagine you're part of a community group helping people avoid immigration enforcement operations. You share information about ICE checkpoints, post legal resources, organize mutual aid. Then, without warning, your Facebook group vanishes. Your posts disappear. The encrypted messaging app you trusted suddenly becomes a target of federal investigation.

This isn't hypothetical anymore. It's happening right now, and it reveals something troubling about how tech companies respond to government pressure.

Over the past year, Trump administration officials have been systematically targeting tech platforms with demands to remove content about Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations. The justification cited: officer safety. The reality: a coordinated campaign to suppress speech that documents government activity and organizes community response.

What makes this situation uniquely dangerous isn't just government overreach. It's that platforms are complying. Not because they're legally required to. Not because court orders demand it. But because government pressure works when platforms don't push back.

Recent lawsuits paint a picture of regulatory coercion. Pam Bondi, the Attorney General, and Kristi Noem, the Department of Homeland Security Secretary, have allegedly pressured major tech companies to remove content without proper legal authority. They've demanded deletion of apps from app stores. They've threatened consequences for news outlets reporting on ICE operations. They've even investigated encrypted messaging services.

And the platforms have largely complied.

This article breaks down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what legal experts say companies should do differently. Because the decisions tech companies make right now will shape whether the First Amendment survives government pressure intact.

TL; DR

- Government officials are using regulatory authority to pressure platforms into removing ICE-related content without court orders, according to lawsuits filed by FIRE and EFF

- Tech platforms are complying even when they could refuse, removing apps, deleting groups, and cooperating with unsubstantiated takedown demands

- The legal barrier is high for government to censor speech unless it directly incites violence or constitutes a true threat, yet platforms ignore this standard

- Tactics include threatening app store rejections, targeting encrypted apps, and pressuring platforms with implicit consequences for non-compliance

- Users are increasingly vulnerable because platforms aren't transparently challenging requests or notifying users before complying with demands

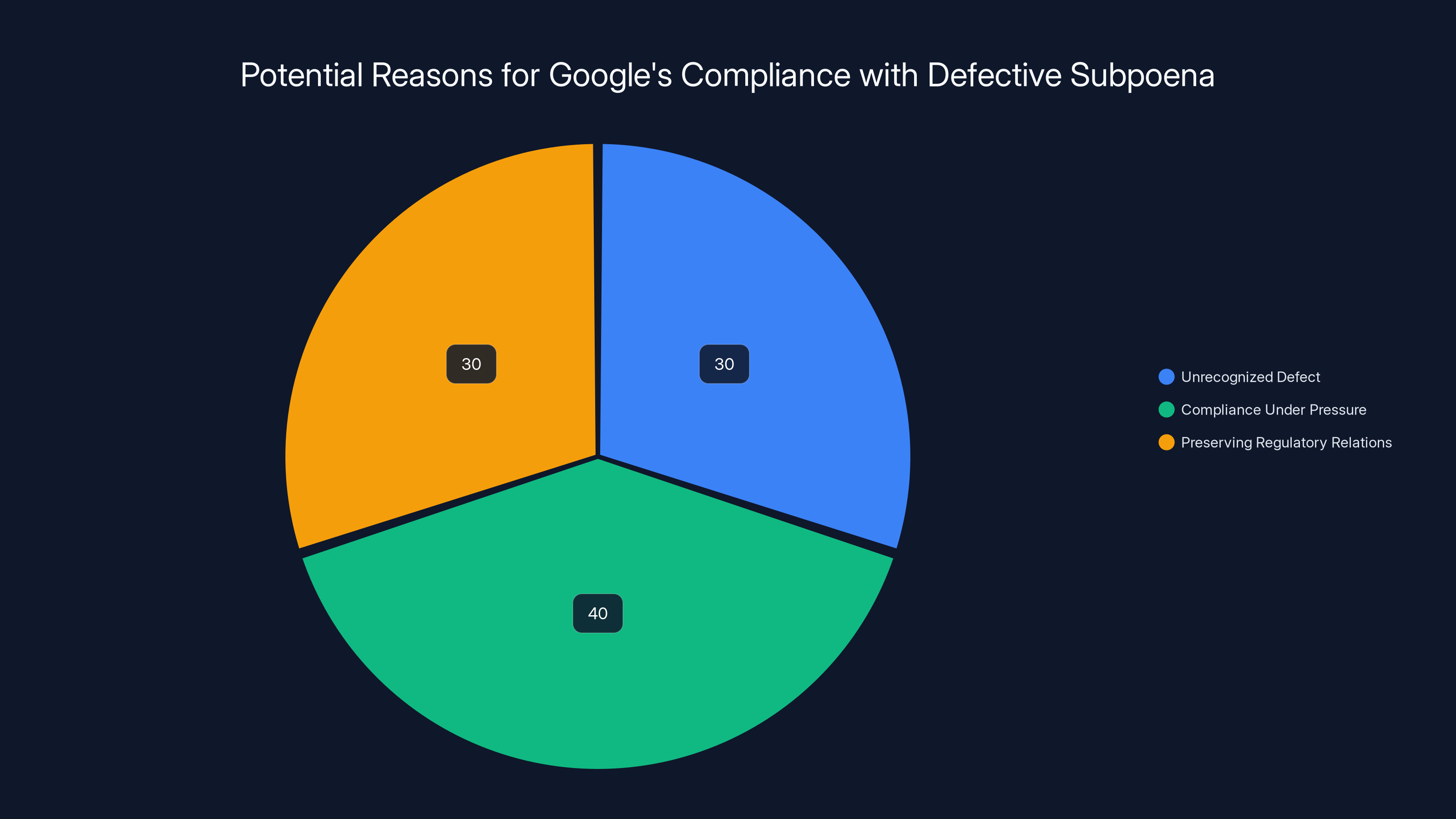

Estimated data suggests Google's compliance with a defective subpoena may be due to pressure, unrecognized defects, or regulatory considerations.

Understanding the Government Pressure Campaign Against ICE Critics

The censorship campaign didn't start with a formal policy announcement. It emerged gradually through regulatory pressure, threatened enforcement actions, and implicit consequences.

DHS officials began systematically contacting tech platforms in early 2025. The pattern was clear: any content that documents ICE operations, helps people avoid enforcement, or criticizes immigration enforcement became a target. The government framed this as protecting officer safety and preventing "doxing" of federal agents.

The problem is that legitimate documentation of government activity isn't doxing. Sharing information about ICE checkpoint locations, immigration raid patterns, or enforcement procedures is journalism, activism, and constitutionally protected speech. Yet platforms started removing this content anyway.

One particularly egregious example: Apple removed an app called ICEBlock from its App Store in October. The app's sole function was to help users document ICE encounters and know their legal rights. No violence. No threats. Just practical information.

When the developer challenged the removal, DHS requested more time to respond. As of March, the case remained unresolved. That's the pattern we're seeing repeatedly: government makes a demand, platforms comply, and users lose access to information with no meaningful recourse.

Meta faced pressure regarding a Chicago-based Facebook group with 100,000 members focused on ICE monitoring. DHS demanded the group be deleted. The group violated no platform policies, incited no violence, and served community members seeking to understand immigration enforcement in their neighborhoods.

Google received a subpoena that was so vague it left critical sections literally blank. Yet Google complied anyway, handing over user information without pushing back on the incomplete legal demand.

Even encrypted apps aren't safe. FBI Director Kash Patel announced an investigation into Signal chats used by Minnesota residents to track ICE activity. This signals that the pressure campaign extends beyond public platforms into encrypted communication, a development that should alarm anyone concerned with privacy and free speech.

What ties these incidents together isn't explicit legal authority. It's implicit threat. Government officials can impose regulatory consequences, conduct investigations, and threaten enforcement actions. Platforms face pressure that's subtle but unmistakable: comply with our demands or face regulatory scrutiny.

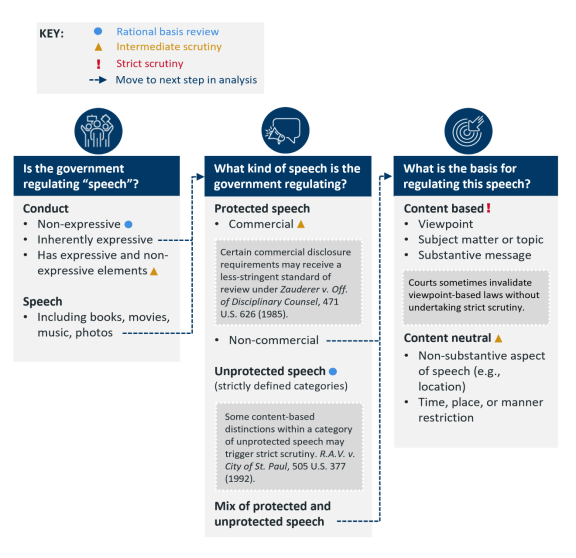

The Legal Framework: Why Government Can't Legally Censor This Speech

First Amendment law sets a clear bar for government censorship. The speech must either directly incite imminent violence or constitute a true threat. Everything else receives protection.

Documenting government activity? Protected.

Organizing community response? Protected.

Sharing legal information? Protected.

Raising public awareness? Protected.

This standard comes from decades of Supreme Court precedent. Brandenburg v. Ohio established that government can only suppress speech that is likely to incite imminent lawless action. Subsequent cases consistently held that documenting government activity, even critical documentation, receives strong First Amendment protection.

Yet the government is using a different standard: officer safety and preventing doxing. These aren't legal justifications for suppressing speech. They're regulatory concerns that might justify other measures, but not systematic removal of protected expression.

Here's the critical distinction: saying "don't confront ICE agents" is protected speech. Sharing a checkpoint location so people can avoid it is protected speech. Criticizing immigration enforcement is protected speech. None of this comes close to inciting imminent violence.

The challenge is that platforms don't have to comply with government demands without court orders. Federal law requires platforms to respond to subpoenas only when they're properly issued by courts. Regulatory agencies can request compliance, but requests aren't orders. Threats aren't legal authority.

Yet platforms are treating government requests with the deference normally reserved for court orders. This creates what legal experts call regulatory coercion: the government doesn't explicitly order removal, but the threat of regulatory consequences makes refusal practically impossible.

Pam Bondi's position as Attorney General gives her formal authority over certain matters. But First Amendment rights are specifically protected from executive control. The Justice Department can't suppress speech it dislikes merely because it's Attorney General.

Kristi Noem's role at DHS gives her oversight of immigration enforcement, but that authority doesn't extend to suppressing speech about immigration. The entire point of the First Amendment is that government can't control what citizens say about government activity.

Yet this is exactly what's happening. DHS is exercising authority it doesn't technically possess by leveraging implicit threat. Platforms could refuse these demands, and courts would likely find the demands unconstitutional. But platforms are complying before that legal battle occurs.

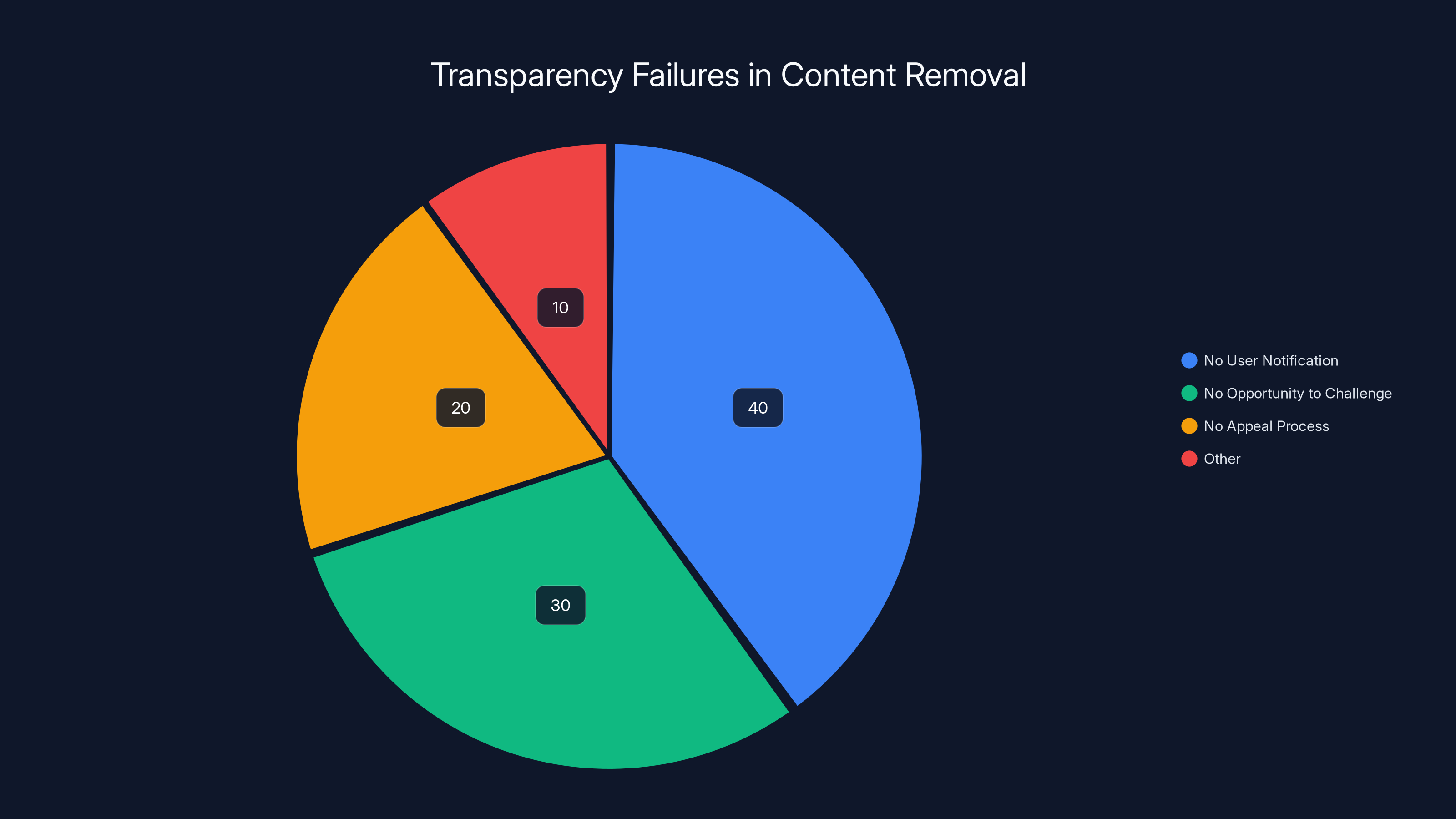

Estimated data suggests that the majority of transparency failures involve no user notification, followed by lack of opportunity to challenge and appeal processes.

How Platforms Are Enabling Censorship Through Compliance

Platforms aren't passive actors being forced into censorship. They're actively choosing compliance, and that choice reveals something important about how they balance user protection against government pressure.

Meta's removal of the Chicago Facebook group set a precedent. The group had 100,000 members, real community value, and no policy violations. Yet when DHS made the demand, Meta deleted it. No transparent process. No user notification in advance. No opportunity for the community to appeal.

Apple's App Store rejection of ICEBlock was similarly unilateral. The app served a legitimate purpose: helping users document their rights during ICE encounters. Yet Apple, facing pressure from federal officials, removed it from the store. The developer couldn't understand why because Apple's rejection reasons were vague.

Google's compliance with the incomplete subpoena is perhaps most revealing. The subpoena left blanks, contained unclear requests, and lacked the specificity required for valid legal process. A competent legal team should have rejected it or requested clarification. Instead, Google handed over user information.

The pattern suggests platforms are treating government requests differently than they treat user requests. When users complain about content, platforms require clear policy violations and often defer removal. When government complains, platforms remove content based on vague allegations of officer endangerment.

This disparity reveals that platforms aren't actually considering First Amendment implications. They're calculating regulatory risk. If DHS can make your App Store approval harder, regulate your data practices, or initiate investigations, compliance becomes rational business decision rather than legal requirement.

Notification practices make this worse. Some platforms have policies requiring user notification before complying with government requests, giving users opportunity to legally challenge removal. Yet in ICE-related takedowns, users often learn about removal only after it's complete.

Signal's experience shows that even companies committed to privacy aren't immune to pressure. When FBI opened an investigation into Signal chats used for ICE monitoring, the implicit message was clear: even encryption doesn't protect you from government scrutiny.

The deeper problem is that platforms have positioned themselves as inevitable censors. They remove content for terms of service violations daily. Extending that removal capability to government requests feels like a natural extension rather than a dramatic shift in policy.

But there's a crucial difference. Terms of service are policies companies can change and users can challenge. Government censorship, when imposed unconstitutionally, violates constitutional rights. Platforms shouldn't treat these identically.

The Role of Regulatory Authority in Pressuring Platforms

Understanding how regulatory authority becomes a coercion tool requires looking at the agencies involved and their power over platforms.

The Department of Homeland Security regulates immigration technology, data practices, and security protocols for systems handling sensitive information. This regulatory authority is real and consequential. DHS can impose fines, restrict government contracts, and require operational changes.

The Attorney General's office oversees law enforcement, has prosecutorial power, and controls regulatory enforcement. Bondi's position gives her formal power to initiate investigations, bring charges, and regulate companies' behavior.

When these officials make "requests" to platforms, the requests carry implicit threat. Refuse and face regulatory scrutiny. Comply and avoid legal conflict.

Facebook, Google, and Apple are all companies that do business with government. They have government contracts, handle sensitive data, and operate in regulated spaces. The regulatory authority these officials wield is real.

It's not like someone threatening you privately. It's institutional power being deployed against companies that depend on remaining in government's good graces.

This is why the FIRE lawsuit specifically alleges coercion rather than direct censorship. The legal claim is that government is using its regulatory authority to achieve what it couldn't achieve directly: suppression of protected speech through private intermediaries.

The lawsuit names both Bondi and Noem personally and in their official capacities. This allows claims both that they exceeded their authority and that the agencies they lead did so.

EFF's FOIA lawsuit requests government emails with platforms to expose exactly what officials said and how pressure was applied. These communications will likely reveal that officials emphasized regulatory consequences, threatened enforcement, or suggested that non-compliance would have negative implications for platforms' legal status.

Once those communications are exposed, courts will need to determine whether suggestions crossed the line from permissible government persuasion to unconstitutional coercion. The distinction is important: government can persuade companies to follow law. Government can't coerce them into unconstitutional action.

Platforms could push back by requiring actual court orders for content removal and making government go through formal legal process. This would separate legitimate law enforcement needs from regulatory overreach. It would also protect users by ensuring judicial oversight of censorship demands.

Instead, platforms are treating regulatory requests with more deference than formal legal process requires. This is backwards. Informal requests should trigger more skepticism, not less.

Case Study: The ICEBlock App Removal and What It Reveals

The ICEBlock app tells a revealing story about how the censorship campaign actually works in practice.

ICEBlock was a straightforward tool. It allowed users to document encounters with ICE agents, understand their legal rights during those encounters, and share information with their communities. The app included:

- Clear information about constitutional rights during immigration enforcement actions

- Templates for documenting encounters

- Legal resources and contact information for immigration attorneys

- Community features for sharing safety information

None of this incited violence. None of this endangered officers. It provided practical information that communities needed.

Apple removed the app in October 2024 from the App Store. The removal notice was vague, citing unspecified policy violations. The developer, facing an unclear rejection reason, couldn't effectively respond or improve the app.

When the developer challenged the removal legally, government officials requested time to respond to the case. They asked for extensions. They moved slowly. What they didn't do is defend the removal based on actual policy violations or legal authority.

That delay is itself revealing. If government had clear legal grounds for the removal, officials would defend them. Instead, delay suggests uncertainty about whether the removal could be legally justified.

The suit likely alleged that Apple violated the developer's First Amendment rights by removing content-based speech in response to government pressure. Apple's removal of the app effectively prevented users from accessing information the app contained.

This case establishes important precedent. It shows that app stores aren't neutral platforms but distribution gatekeepers with power to suppress speech. When those gatekeepers respond to government pressure by removing apps, users lose access to protected speech without due process.

It also shows that government officials understand their actions are legally vulnerable. If they were confident in their legal authority, they wouldn't delay and request extensions in court.

The case potentially exposes how exactly the pressure was applied. Discovery in litigation will reveal communications between Apple and DHS. These communications will show whether officials explicitly demanded removal or used more subtle pressure.

Other companies have faced similar situations with different results. Signal's refusal to comply with government pressure is notable. Unlike Meta and Google, Signal hasn't visibly caved to demands. This suggests that resistance is possible and that platforms do have leverage to refuse.

The question for other app store operators and platforms is whether they'll follow Meta and Google's compliance model or Signal's resistance model. The legal and business case for resistance is actually stronger than many companies realize.

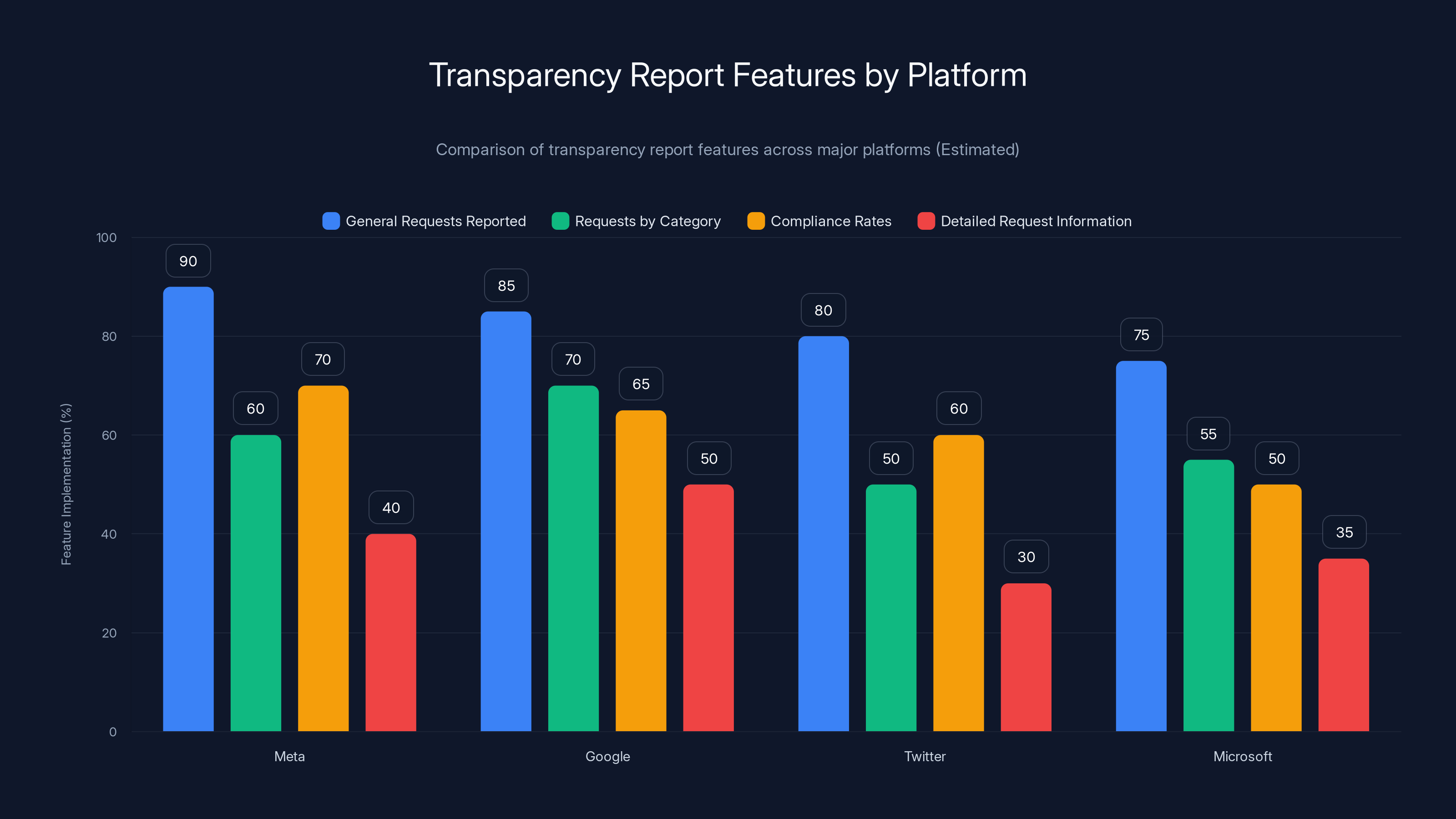

Estimated data shows that while most platforms report general requests, fewer provide detailed request information. More granular transparency is essential for accountability.

The Facebook Group Targeting: What 100,000 Member Communities Tell Us

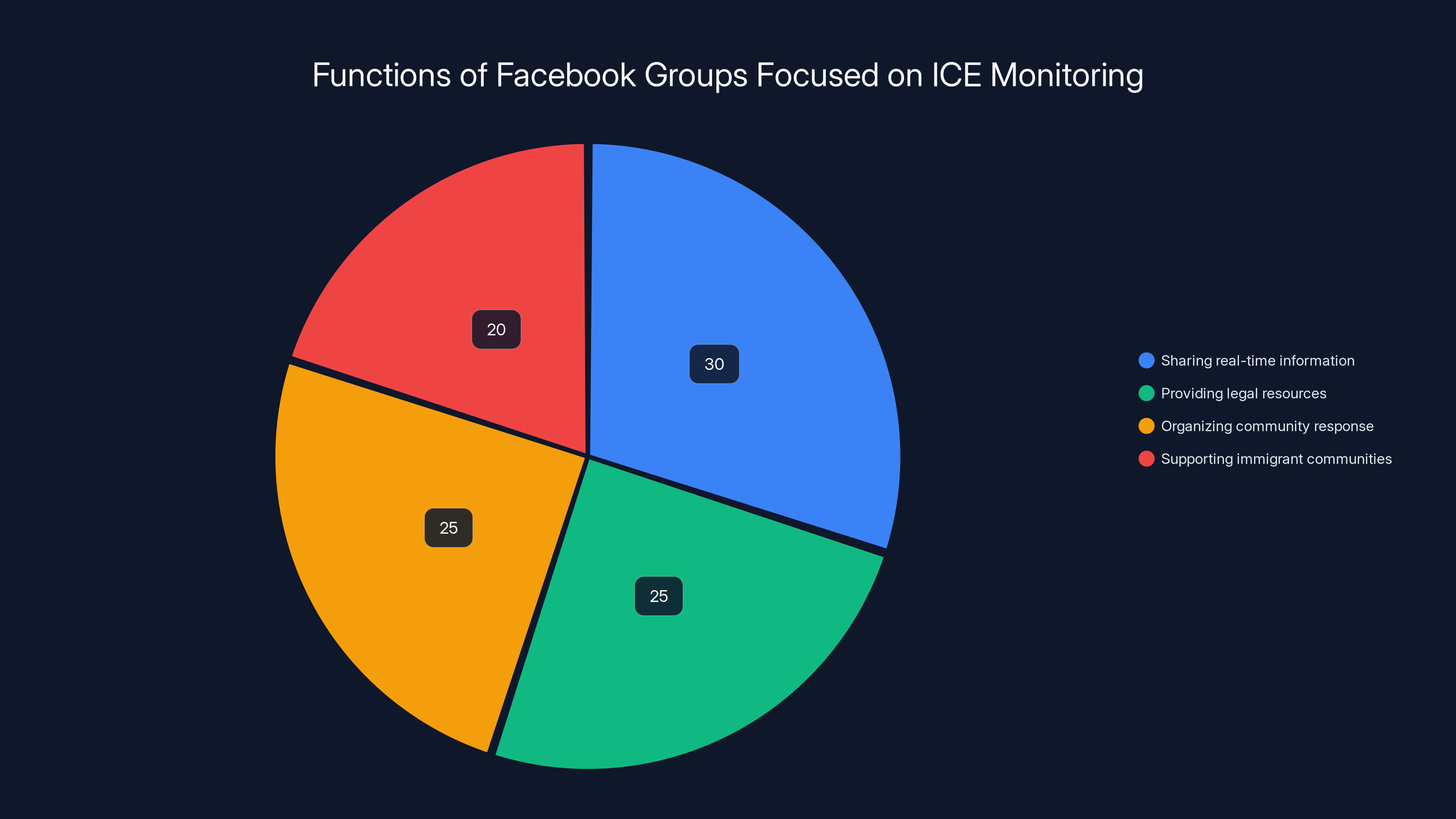

The Chicago-based Facebook group targeted by DHS tells us something important about government's actual goals. This wasn't targeting a fringe extremist community. This was targeting a legitimate community resource with 100,000 members.

Facebook groups focused on ICE monitoring typically serve several functions:

- Sharing real-time information about ICE checkpoints and enforcement operations

- Providing legal resources and rights information

- Organizing community response to enforcement actions

- Supporting immigrant communities in navigating legal systems

These groups don't coordinate violence. They don't incite illegal action. They provide information and community support.

The fact that DHS demanded removal of a 100,000-member group suggests that government's concern isn't actually about officer safety or doxing. It's about public awareness of ICE operations.

When governments become concerned about public awareness of their activities, that's a signal that censorship is the actual goal rather than a side effect. Democratic societies depend on public knowledge of government actions.

Meta's compliance with the demand is particularly significant because Facebook has explicit policies around government requests. The company publishes transparency reports showing how many requests it receives and how it responds.

Yet in this case, Meta apparently didn't follow its own published standards. There's no indication the community was notified before deletion. There's no indication users could challenge the removal. There's no indication the removal was appealed to Facebook's Oversight Board.

For communities relying on Facebook for organization and communication, sudden deletion is devastating. The 100,000 members lost access to the network they used for mutual aid, information sharing, and community coordination.

This is why the lawsuits name the specific companies and the specific takedowns. Courts need to understand not just that removal happened, but what the removal cost communities and whether it served legitimate government interests or suppressed protected speech.

The group's size matters legally too. A 100,000-member group clearly serves community needs. Removal of such a large community isn't narrow tailoring to a specific harm. It's broad suppression of speech reaching many people.

It also suggests the demand came from high-level officials rather than individual agents. Large platforms make significant decisions about major communities at senior levels. A 100,000-member group wouldn't be deleted at lower levels without escalation.

This points to Bondi and Noem specifically, who have the authority to demand such actions. Lower-level officials wouldn't typically reach out to Meta about removing a specific group. They'd work through standard reporting channels.

Google's Subpoena Compliance and the Blank Sections Problem

Google's compliance with an incomplete subpoena exposes a critical vulnerability in how platforms handle legal requests.

Subpoenas are supposed to be specific. They're supposed to clearly identify what information is being requested, why it's needed, and from whom it's being sought. Vague subpoenas can be challenged and are often considered defective.

Yet the subpoena Google received had blank sections. Critical identifying information was missing. The request lacked the specificity required for valid legal process.

Competent platform counsel should have responded: "Your request is incomplete. Please clarify what information you're seeking and provide valid legal authority."

Instead, Google complied. It handed over user information based on a legally defective request.

This reveals several possibilities:

- Google's legal team didn't recognize the subpoena as defective

- Google recognized the defect but complied anyway due to pressure

- Google deliberately looked past the defect to preserve regulatory relations

None of these possibilities reflect well on platform responsibility to users. If platforms aren't carefully reviewing government legal requests, they're failing their fiduciary duty to protect user data and privacy.

The blank sections likely contained fields for:

- Specific individuals being targeted

- The legal basis for the request

- The investigation the request supported

- The time period covered

- The specific content being sought

Without this information, the request was legally incomplete. Google couldn't even determine whether the request was lawfully issued or whether the information sought was actually relevant to government's stated purpose.

This is where EFF's FOIA lawsuit becomes critical. By obtaining communications between Google and government, EFF will expose how the request was framed and what pressure surrounded it.

It's possible that the blank sections were intentional. Perhaps government knew the full details would weaken the legal justification, so partial request was designed to pressure compliance without full disclosure.

It's also possible that the person drafting the subpoena was incompetent or in a hurry. But that doesn't excuse Google's compliance. Incomplete legal requests should trigger careful review, not automatic handover of user data.

Platforms should adopt stricter policies:

- Require complete, specific legal requests before responding

- Challenge ambiguous or incomplete requests

- Notify users whenever legally possible before complying

- Publish quarterly reports on government requests and compliance rates

- Establish dedicated legal teams focused on protecting user rights

Google's compliance with the incomplete request suggests these protections aren't currently in place or aren't being enforced.

Signal, Encryption, and the Scope of Pressure Campaign

FBI Director Kash Patel's announcement of an investigation into Signal chats used by Minnesota residents to track ICE activity represents a significant escalation.

This moves beyond pressure on platforms to suppress content. This is investigation of encrypted communication itself. The message is clear: even if you move to encrypted platforms, government will investigate your activity.

Signal's encryption is specifically designed to prevent Signal employees from accessing user messages. Signal doesn't have a "backdoor" that lets law enforcement read messages. The encryption is end-to-end, meaning only the communicating parties can read the messages.

Yet Patel's investigation suggests this protection doesn't matter. Government will investigate anyway.

This accomplishes something important: it creates chilling effect. Users who know their encrypted communications are being investigated feel pressure to stop using those tools or to self-censor what they say.

For the Minnesota residents using Signal to track ICE, the investigation sends a message: your protected activity isn't actually protected. Law enforcement can investigate you anyway.

Signal's response to pressure is notably different from Meta and Google's response. Signal hasn't complied with demands to build backdoors or provide encryption keys. Signal hasn't removed its app from the App Store.

Signal's resistance is based partly on technical reality: Signal's encryption is designed to be unbreakable. But it's also based on principle: Signal is committed to user privacy and won't compromise that for government convenience.

The investigation doesn't change this. It might delay Patel's case by tying up law enforcement resources. But it won't force Signal to compromise encryption or provide user data it can't access.

This makes the Signal case important for understanding why platform resistance matters. When platforms resist pressure consistently, government eventually stops asking or accepts that some requests can't be complied with.

When platforms comply inconsistently, government learns that pressure works. Meta and Google's compliance with ICE-related takedowns teaches government that continued pressure will yield continued compliance.

For platforms considering how to handle government pressure, Signal's example is instructive. Resistance is possible. It doesn't require special technical skills like Signal's unbreakable encryption. It just requires being willing to say no.

Doing so might trigger investigation or regulatory scrutiny. But accepting government censorship demands has costs too. Users lose trust. Platforms lose credibility as protectors of free expression. And once compliance establishes precedent, pressure only increases.

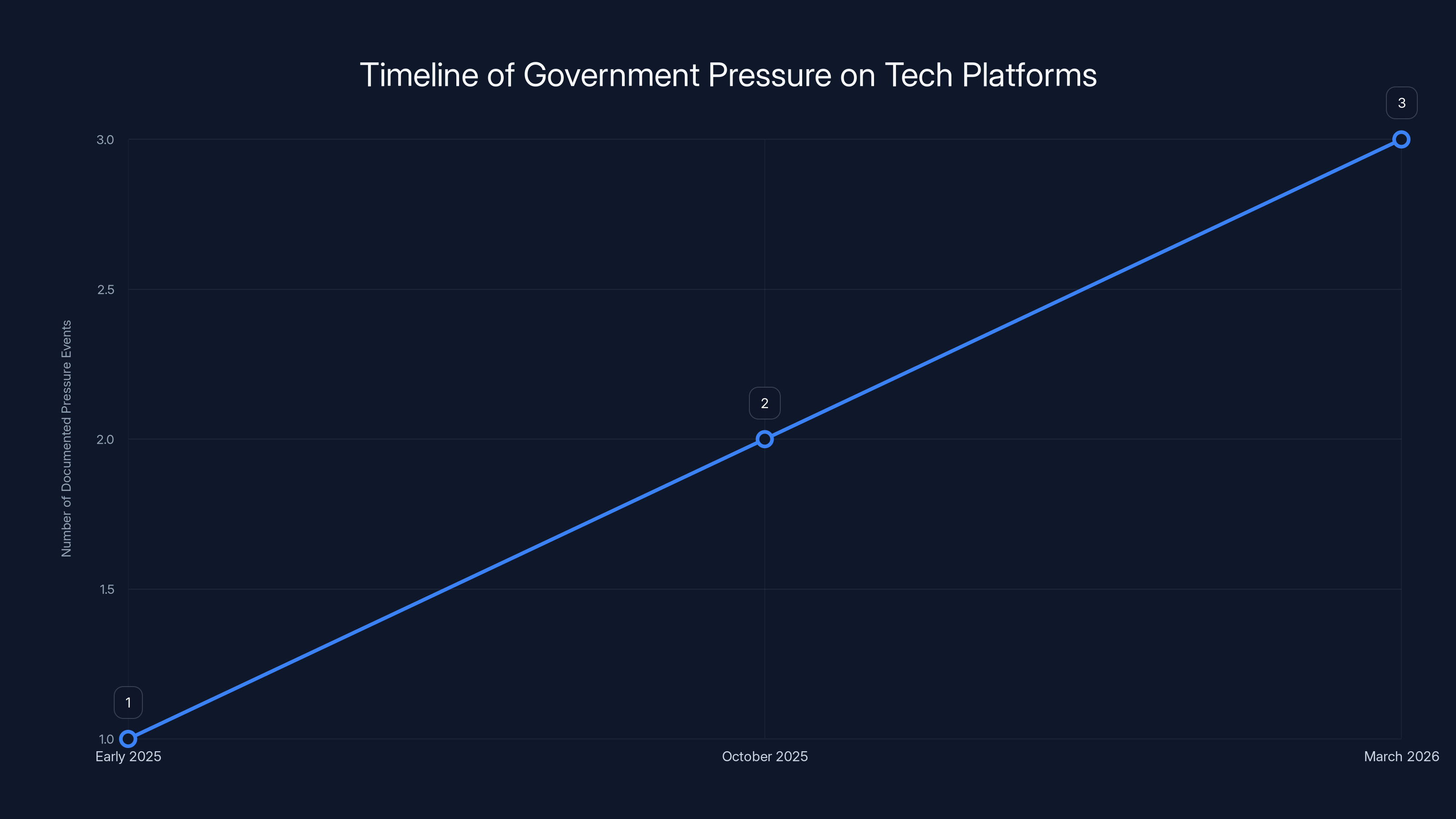

The timeline illustrates the gradual increase in government pressure on tech platforms, starting in early 2025 and continuing with significant events like app removals and subpoenas. Estimated data.

Transparency Failures: When Users Don't Know Content Was Removed

One of the most troubling aspects of the ICE censorship campaign is that users often don't know their content has been removed or why.

Most major platforms claim to have transparency practices. They promise to notify users when content is removed. They claim to give users opportunity to challenge removal.

Yet in the ICE-related takedowns, these promises aren't being kept.

Users of the deleted Chicago Facebook group didn't get advance notice. They woke up to find their community gone. No explanation. No opportunity to challenge. No appeal process.

ICEBlock users who downloaded the app didn't get notice that it was being removed from the App Store. They just couldn't find it when they looked for updates.

This violates the transparency standards platforms claim to uphold.

Meta publishes government request transparency reports. Google does the same. These reports show that major platforms do get substantial government requests and that they publish data about government's censorship demands.

But these same platforms are apparently making exceptions for ICE-related content without going through normal transparency processes.

This suggests either:

- Platforms are treating government pressure as different from normal legal requests

- Platforms are treating content that government calls "threats to officer safety" differently from other content

- Platforms have informal understandings with government about removal that bypass formal transparency processes

Any of these possibilities is concerning from a user protection perspective.

The solution is straightforward: platforms should maintain consistent transparency practices regardless of who the government is or what issue is involved. Every user notification policy should apply equally. Every appeal process should be available.

Platforms could also increase transparency by:

- Publishing aggregate data on government requests by category (ICE-related vs. other)

- Listing specific groups/pages/apps removed at government request

- Describing the legal basis government provided

- Detailing when requests lacked clear legal authority

- Reporting when platforms challenged government requests

This would immediately expose whether government is using legitimate legal process or coercion. It would also pressure platforms to maintain higher standards since their practices would be visible.

The Freedom of Information Act Litigation: Exposing Government Pressure

The Electronic Frontier Foundation's FOIA lawsuit filed last fall is potentially the most important development in exposing the censorship campaign.

FOIA requires federal agencies to release records when citizens request them. It applies to communications between government and private entities about government business.

EFF's lawsuit targets the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Customs and Border Patrol. The request seeks all emails and communications between these agencies and tech platforms about takedown demands.

These communications will reveal:

- Exactly what officials said to platform executives

- Whether officials threatened regulatory consequences

- What justifications were provided for removal requests

- How pressure was applied

- Whether officials acknowledged legal weakness of removal requests

- What platforms said in response

Once these communications are public, courts will be able to judge whether government crossed the line from legitimate persuasion to unconstitutional coercion.

EFF Senior Staff Attorney Mario Trujillo told us the case is expected to move slowly, as FOIA litigation typically does. But the organization is confident it can win access to these records.

What makes this case urgent is that ICE activity is escalating and delays in addressing censorship concerns could irreparably harm free speech at a critical moment. Every month of delay means more communities lose access to ICE monitoring resources. More people lose access to legal information. More organized response becomes harder.

Meanwhile, government learns that pressure works. Each time a platform complies, officials become more confident that the next demand will also be met.

But Trujillo noted something important: when government was actually challenged in court regarding attempts to unmask anonymous Facebook group administrators, government quickly withdrew the requests. The fact that they withdrew suggests officials weren't confident they could defend the requests in court.

This is what legal advocates call an "acknowledgement that the Trump administration, when actually challenged in court, wasn't even willing to defend itself."

It means that much of the government's pressure campaign depends on platforms not pushing back. Once platforms do push back, government has to choose between:

- Going to court and defending the request legally

- Withdrawing the request

Government chose withdrawal rather than legal defense. That's important. It suggests the legal authority doesn't actually exist.

For platforms, this is actionable. They could view continued government pressure as evidence that resistance works when attempted. Platforms could become a first line of defense, requiring officials to get court orders before complying with any requests.

What Platforms Should Be Doing: Best Practices for Resisting Pressure

Current platform behavior reveals that many companies are treating government requests with more deference than law requires. They could do significantly better at protecting users.

First, platforms should require valid court orders for all content removal based on government requests. Not subpoenas. Not regulatory requests. Not informal pressure. Court orders issued by judges who've reviewed the request and found sufficient legal basis.

This single change would immediately protect users by ensuring judicial oversight. It would also give platforms legal ground to refuse requests that government can't convince a judge to support.

Second, platforms should notify users before complying with removal requests whenever legally possible. Some requests include confidentiality orders preventing notification, but many don't. Users deserve opportunity to challenge censorship through legal process.

Third, platforms should publish detailed transparency reports breaking down government requests by type, whether requests included valid court orders, what portion of requests platforms complied with, and whether platforms challenged any requests.

Fourth, platforms should establish dedicated legal teams focused on protecting user rights when they conflict with government pressure. These teams should have authority to refuse requests they believe are legally invalid or unconstitutional.

Fifth, platforms should develop policies treating speech-suppressing requests differently from other government requests. Content removal requires higher standards of evidence than fraud investigation or national security requests.

Sixth, platforms should join advocacy organizations and amicus briefs in cases challenging unconstitutional government pressure. Platforms have incentive to establish legal precedent limiting government power to coerce censorship.

Seventh, platforms should educate users about their rights and about platform policies protecting those rights. When users know they have recourse, they're more likely to challenge wrongful removal.

None of these practices are unusual or unreasonable. Many platforms claim to follow some of them already. The problem is that ICE-related takedowns show these practices aren't being consistently applied.

Signal demonstrates that some platforms are willing to resist pressure. Meta and Google demonstrate that resistance is possible but not inevitable. The question for other platforms is which example they'll follow.

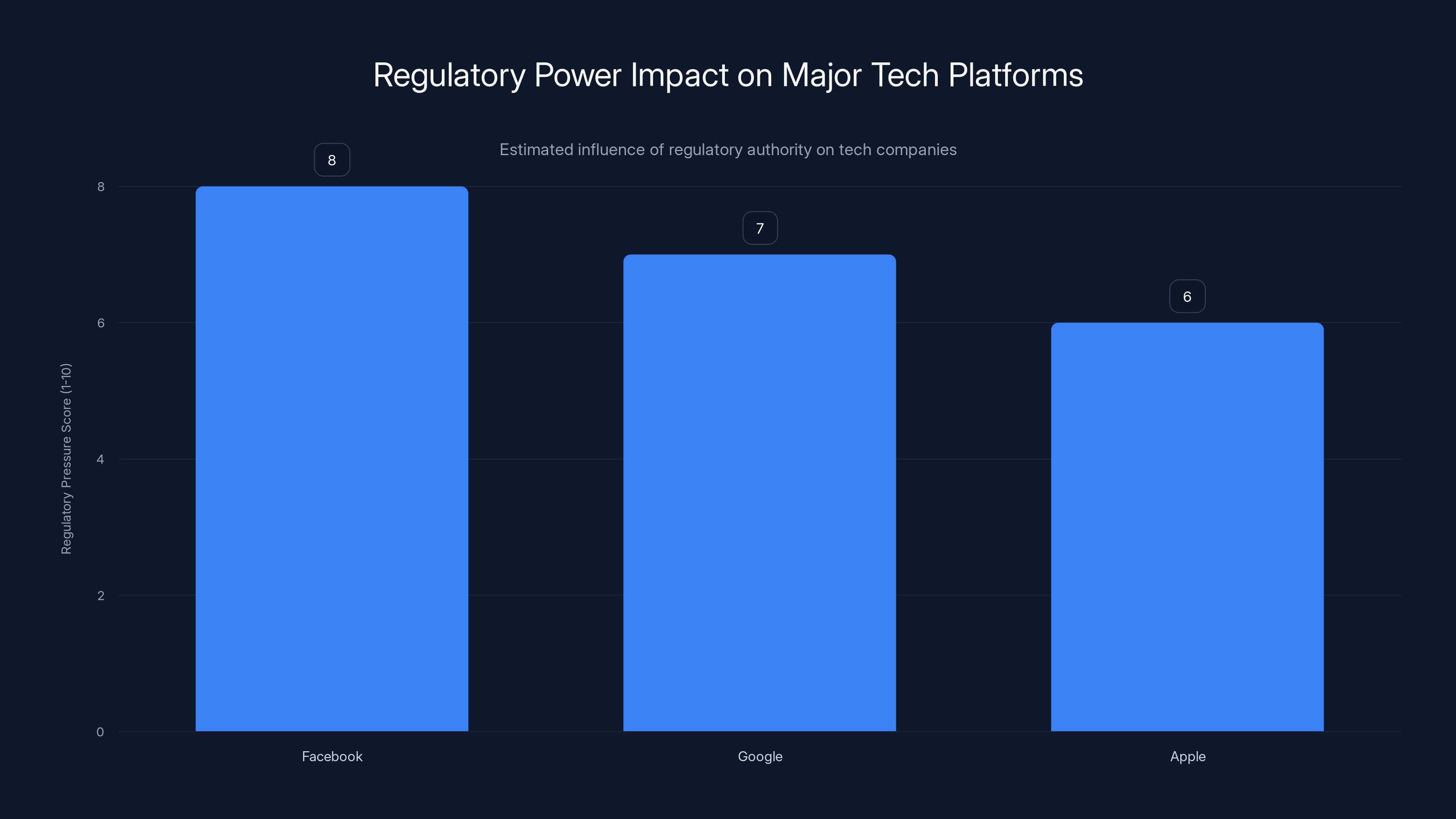

Estimated data showing the relative regulatory pressure on major tech platforms, with Facebook facing the highest pressure due to its extensive data handling and government contracts.

The Broader Implications: Democracy, Information Access, and Speech

The ICE censorship campaign isn't just about immigration enforcement. It's about establishing precedent for government control of information.

Once government successfully pressures platforms into removing ICE-related content without court orders, what's to stop it from doing the same for other topics? What's to stop censorship of:

- Content criticizing other government agencies

- Information about police enforcement activities

- Community organizing and protest information

- Whistleblower communications

- Research into government programs

- Media reporting on government activities

Each of these categories involves information government might prefer to suppress. Each could be justified with claims about safety or security similar to the "officer safety" justification for ICE censorship.

The precedent being set is whether platforms will automatically comply with government pressure or whether they'll require legal process and judicial oversight.

This is fundamentally about the balance of power. When government can control what information citizens access without proving its case to a court, government has power incompatible with democracy.

Democracy depends on citizens having access to information about what government is doing. If government can prevent that information from circulating, citizens become unable to make informed decisions or hold government accountable.

The framers understood this, which is why the First Amendment exists. The framers worried specifically about government power to control information, so they wrote a constitutional provision explicitly limiting that power.

The ICE censorship campaign tests whether that protection still functions. Platforms are currently failing the test by complying with pressure instead of defending user speech rights.

But courts might not. The lawsuits being filed by FIRE and EFF give courts opportunity to clarify that government can't achieve through regulatory pressure what it can't achieve directly through law.

For citizens who care about free speech and democracy, the ICE cases are important test cases. How courts rule on them will shape whether government can censor protected speech through platform pressure or whether the First Amendment still provides meaningful protection.

Legal Arguments in FIRE's Lawsuit: Why Coercion Matters

FIRE's lawsuit against Bondi and Noem advances sophisticated legal arguments about coercion and First Amendment rights.

The core claim is that government is using its regulatory authority to coerce private platforms into censoring protected speech. This is unconstitutional even if the platforms are private companies, because it violates the First Amendment rights of users.

The Supreme Court established in New York Times v. Sullivan that governments can't achieve through pressure on newspapers what they can't achieve directly. When government uses its power to threaten private entities with consequences for not suppressing speech, that's unconstitutional coercion.

FIRE's complaint detailed multiple instances where government allegedly:

- Threatened to reject or remove apps from app stores

- Demanded deletion of community groups

- Demanded removal of content

- Attempted to unmask anonymous users

- Investigated encrypted communication about ICE activity

Each of these demands allegedly came with implied threat that non-compliance would result in regulatory consequences.

The legal distinction between permissible government persuasion and impermissible coercion turns on the specificity and credibility of threatened consequences.

If government says "we think this is illegal, please remove it," that's persuasion. Companies can refuse.

If government says "if you don't remove this, we'll investigate your company, reject your app, or impose regulatory penalties," that's closer to coercion. Especially when the threat-maker has actual power to impose those consequences.

Bondi and Noem have that power. Bondi as Attorney General can authorize investigations. Noem as DHS Secretary can impose regulatory consequences. When they make "requests," companies understand the requests come with implicit threat of regulatory retaliation.

FIRE's lawsuit alleges that this implicit threat is actually explicit coercion and that it violates the First Amendment rights of platform users even though the platforms themselves are private companies.

This is a complex legal theory, but it has Supreme Court precedent. The Court has held that governments can't circumvent constitutional protections by delegating suppression to private entities.

The strength of FIRE's case depends partly on evidence of what Bondi and Noem actually said to platform executives. If government merely requested removal, that's permissible. If government threatened consequences for non-compliance, that's coercion.

The EFF's FOIA lawsuit will expose this evidence. Once the communications are public, courts will know what pressure was actually applied.

Timing: Why This Campaign Started Now

The timing of the censorship campaign is important. Why did this escalate in early 2025 specifically?

Several factors converge:

First, Trump administration took office with explicitly hardline immigration positions. ICE operations have increased. Enforcement activity has become more visible and more aggressive.

Second, communities have become more organized at monitoring and resisting ICE. The Chicago Facebook group alone had 100,000 members. This represents real organizational capacity that government wants to disrupt.

Third, Trump administration appears to have decided that suppressing information about ICE operations would reduce public opposition to enforcement. By preventing news of ICE raids, checkpoints, and enforcement operations from spreading, government might reduce organized community response.

Fourth, new officials in key positions (Bondi at Justice, Noem at DHS) apparently viewed executive power to suppress speech as legitimate tool of enforcement. They moved quickly to use pressure on platforms.

Fifth, platforms may have signaled willingness to comply with certain requests in private conversations. Once officials sensed willingness, they scaled up demands.

The campaign isn't random. It's deliberate enforcement of immigration policy through information control.

This is why timing matters for legal claims. Courts need to understand that government's stated justifications (officer safety, preventing doxing) are pretexts for the actual goal (suppressing public awareness of ICE operations).

The volume and breadth of removal requests suggests systematic campaign rather than isolated incidents. That pattern strengthens the case that government is using regulatory authority to suppress disfavored speech rather than protecting specific harms.

It also explains why communities relying on platforms for organizing are increasingly vulnerable. The campaign suggests government will continue and likely intensify pressure if platforms keep complying.

Estimated data shows that sharing real-time information is the most common activity in ICE monitoring Facebook groups, followed by providing legal resources and organizing community responses.

Platforms as Gatekeepers: The Power to Suppress Without Courts

Underlying all of this is a fundamental question about platform power: should private companies be able to suppress protected speech even if government can't?

Platforms argue they have right to enforce community standards and remove violative content. They point to terms of service that users agree to. They claim editorial discretion similar to newspapers.

But platforms are different from newspapers. Newspapers are explicitly editorial. Readers expect editorial judgment. Platforms claim to be neutral distribution systems, not editors.

Moreover, platforms have power incomparably greater than newspapers. Facebook reaches billions of people. A newspaper reaches thousands. When Facebook removes your content, you lose access to that audience globally. You can't quickly move to another platform of equivalent reach.

This gatekeeping power is partly natural monopoly: there aren't viable alternatives to Facebook for reaching billions. It's partly network effects: the platform is valuable because everyone's on it, so everyone stays even if service worsens.

Given this power, questions about platform responsibility for suppressing speech become more important.

When platforms remove speech, they're not just exercising editorial judgment. They're controlling what billions of people can access. That's power approaching government's.

If platforms use that power to comply with government censorship demands, they're effectively creating government censorship without judicial oversight.

Some scholars argue platforms should be treated as "common carriers" with responsibility to carry all speech (except truly harmful content). Others argue platforms should be treated as publishers with editorial rights.

Most likely answer is platforms are both: they have publisher's right to remove genuinely harmful content (violence, illegal activity, harassment) but carrier's responsibility to treat users equally and to resist government pressure for purely political speech suppression.

Under this framework, removing ICE-related content would generally violate platform responsibility. The content is protected speech about government activity, not genuinely harmful content.

The lawsuits essentially argue that platforms should acknowledge this responsibility. They're asserting that platforms can't hide behind terms of service while complying with unconstitutional government pressure.

What Success Looks Like: Possible Outcomes of Ongoing Litigation

Several legal cases will determine what outcome is possible and what precedent gets established.

If courts side with FIRE and EFF, they'll likely establish that government can't use regulatory authority to coerce private platforms into suppressing protected speech. Bondi and Noem might face personal liability. Platforms might be required to restore deleted content and notify users of government demands.

Government would lose power to pressure platforms into censorship without going to court first.

If courts side with government, they'll establish that regulatory authority can be used to pressure platforms into compliance with government demands. Officials wouldn't need court orders. Platforms could be sanctioned for not complying with informal requests.

Government would gain power to control online information by threatening regulatory consequences.

Most likely outcome is something between these extremes. Courts will probably establish that:

- Government can request compliance with valid legal process

- Government cannot use regulatory authority to threaten non-compliant platforms

- Platforms must treat government requests with same rigor as any legal request

- Platforms should require court orders for content removal

- Some types of content (incitement to violence, true threats) don't require court process

- Content about government activity requires higher legal standard

This middle ground would allow government to suppress genuinely harmful speech while preventing suppression of protected political speech.

For platforms, success means:

- Clear legal authority to refuse government requests lacking proper legal process

- Established practice of requiring court orders for content removal

- Legal standing to challenge coercive government pressure

- User trust that platforms will protect speech rights

For users and advocates, success means:

- Access to information about government activity

- Ability to organize community response without fear of platform deletion

- Transparency about government censorship demands

- Due process before content removal

The litigation will likely take years. Courts move slowly. But the cases will establish legal precedent affecting all future government censorship attempts.

Meanwhile, communities continue losing access to ICE monitoring resources. The case for platform resistance strengthens with each demand government makes.

The Role of Transparency Reports: How Platforms Can Protect Users

One underutilized tool for protecting users is transparency about government censorship demands.

Most major platforms publish transparency reports showing how many government requests they receive and how many they comply with. These reports cover things like:

- Total government requests

- Requests broken down by country

- Requests for user data vs. content removal

- Compliance rates

But the reports typically lack detail about specific requests. They don't show:

- Which agencies made requests

- Which content was removed

- Whether requests included valid legal authority

- Whether platforms challenged requests

- Whether requests were politically motivated

More detailed transparency could illuminate censorship campaigns like the one targeting ICE-related content.

If Meta's transparency report broke down requests by category and identified that ICE-related requests had unusually high compliance rate, the pattern would become visible. If Google reported that subpoenas for ICE-related content had lower specificity than other subpoenas, anomaly would be apparent.

Transparency isn't a complete solution. It doesn't stop government from making demands. But it creates accountability.

Platforms that hide government pressure by not reporting it implicitly sanction that pressure. Platforms that transparently report government demands create pressure on government to justify those demands.

Some platforms have started publishing more detailed transparency reports. A few now report specific categories like "immigration enforcement" separately. But most still lump all government requests together.

For platforms serious about protecting users, more granular transparency is essential. It would:

- Create public visibility for government censorship patterns

- Allow researchers to study coercion campaigns

- Provide evidence for litigation challenging unconstitutional demands

- Build user trust by showing what pressure platforms resist

- Create accountability for both government and platforms

The irony is that government is using secret pressure campaigns while platforms maintain public image of independence. Transparency would disrupt this dynamic.

Once users learn that platforms are complying with government censorship demands, users would demand change. Platforms would face pressure from both government (to comply) and users (to resist).

Given this, platforms benefit from keeping government pressure secret. Transparency creates accountability they want to avoid.

But user trust is what makes platforms valuable. Users trust Facebook to carry their messages. Users trust Google to find information. If users learn platforms are secretly complying with government censorship, that trust erodes.

For platforms playing long game, transparency about government pressure might actually protect brand value. Companies that visibly resist unconstitutional government demands gain user trust. Companies that secretly comply lose credibility once pressure is exposed.

Moving Forward: What Communities Can Do

While litigation proceeds and platforms resist or capitulate to government pressure, communities need practical strategies for protecting their information sharing and organizing.

First, diversify platforms. Don't rely solely on Facebook or Google for community organizing. Use multiple platforms so a single removal doesn't eliminate your network.

Second, document everything. Save copies of all community content, member lists, organizing information. If platforms remove your community, you'll have evidence and archive.

Third, know your rights. Most platforms have appeal processes for content removal. Understand these processes and use them when government forces removals.

Fourth, contact digital rights organizations when you experience removal. FIRE, EFF, ACLU, and other groups have resources for challenging unconstitutional censorship. They may be able to help legally.

Fifth, use tools specifically designed for privacy and resilience. Encrypted messaging apps, self-hosted community platforms, decentralized networks. These provide protection platforms can't guarantee.

Sixth, organize with platforms. Community pressure can force platforms to adopt better practices. If enough users demand transparency about government requests, platforms will provide it.

Seventh, support litigation challenging government censorship. Organizations like FIRE and EFF rely on public support for funding. Contributing to these organizations supports the legal work defending free speech.

Eighth, engage in political advocacy. Pressure elected representatives to constrain agency authority to pressure platforms. Support candidates who defend free speech rights.

Ninth, build redundancy into organizing infrastructure. If one app is removed, have backup communication methods. If one platform disappears, have established presence elsewhere.

Tenth, think critically about what information actually needs protection. Government censorship of ICE monitoring information is wrong, but information is more secure when it's public and widely distributed than when it's secret and concentrated.

These strategies won't stop government censorship entirely. But they make communities more resilient when censorship occurs.

FAQ

What is government censorship of protected speech?

Government censorship occurs when government authorities suppress speech without going through constitutional legal process. Protected speech includes information about government activity, political organizing, and criticism of government policies. When government prevents this speech without proving to a court that it directly incites violence or constitutes a true threat, that's unconstitutional censorship even if the actual suppression is carried out by private platforms.

How does the regulatory pressure campaign work in practice?

Regulatory officials with authority over platforms make demands that content be removed, often citing officer safety or doxing concerns. They imply that non-compliance will result in regulatory consequences like app store rejections, enforcement actions, or investigations. Platforms, understanding these implicit threats, comply even without valid court orders. The pressure works because government has real regulatory power, making refusal risky even if it might be legally defensible.

What are the First Amendment implications of platform compliance?

When platforms remove protected speech at government's request, they effectively create government censorship without judicial oversight. The First Amendment protects speech about government activity with narrow exceptions for incitement and true threats. Content helping communities understand and avoid ICE operations falls within protected speech. Platform compliance with removal demands violates these constitutional protections even though platforms are private companies subject to different rules than government.

Why haven't courts stopped the censorship campaign already?

Litigation is slow. The ICEBlock removal case was filed months ago and remains unresolved because government requested extensions to respond. The FOIA lawsuit seeking communications between government and platforms will take additional years to resolve. Meanwhile, content removal continues. Courts will eventually address whether government pressure is unconstitutional, but the delay means communities lose access to resources while legal cases proceed.

What can individual users do if their content is removed by government demand?

First, understand that removal at government request is different from normal platform enforcement. Document the removal and the government demand that caused it if possible. Contact digital rights organizations like FIRE, EFF, or ACLU that can provide legal support. Use the platform's appeal process. Consider pursuing litigation if removal caused significant harm. Most importantly, build diverse community presence so a single removal doesn't eliminate your network.

Can platforms legally refuse government removal requests?

Yes. Platforms can require valid court orders before removing content. Regulatory requests and threats don't have legal force without court oversight. Signal refused government pressure to build encryption backdoors and faced no legal consequences. Other platforms could do the same by treating government requests with skepticism and requiring judicial authorization. The legal framework supports platform resistance even if business pressures encourage compliance.

What precedent would courts establish if they rule against government censorship?

Courts could establish that government cannot use regulatory authority to coerce private platforms into suppressing protected speech. This would require government to go through formal legal process, get court orders, and prove that speech meets narrow legal standards for permissible censorship. It would also establish that platforms have affirmative duty to protect user speech rights rather than automatically complying with government pressure. This precedent would apply beyond ICE to all government censorship attempts.

How does this censorship campaign differ from normal government requests for content removal?

Normal government requests go through established legal channels with specific legal authority. They target genuinely harmful content like child exploitation or incitement to violence. The ICE censorship campaign uses vague justifications (officer safety, doxing), lacks valid court process, and targets protected political speech. It's systematic rather than isolated and uses implicit threats rather than formal legal authority. These differences suggest the campaign is about suppressing disfavored speech rather than addressing genuine harms.

What role does platform business models play in determining compliance with censorship demands?

Platforms dependent on government contracts or regulatory approval are more vulnerable to pressure. Platforms like Meta and Google with significant government business have more to lose from regulatory conflict. Signal, which doesn't take government contracts or advertiser money, can more easily resist pressure. This suggests that platform independence depends partly on business model. Users concerned about free speech should prefer platforms with business models that don't depend on government goodwill.

What happens if government wins these legal cases?

If courts side with government, officials would gain power to pressure platforms into censorship without court orders. Government could suppress any speech by threatening regulatory consequences. Free speech protection would depend on platforms' willingness to resist pressure, not on legal rights. This would fundamentally shift power toward government and away from protected speech. It would establish precedent allowing government to censor political opponents, critical media, and community organizing efforts through regulatory pressure on platforms.

Conclusion: The Stakes of Digital Censorship

The ICE censorship campaign reveals something critical about how power flows through digital infrastructure. Government can't directly censor platform users without facing constitutional barriers. But government can pressure platform companies into doing the censoring on government's behalf.

When this pressure succeeds because platforms don't push back, government learns it can control information by threatening regulatory consequences. When this pressure fails because platforms resist, government has to choose between accepting the speech or going to court to justify censorship.

The outcomes of ongoing litigation will shape which pattern becomes normal.

For now, communities are losing access to resources they depended on. Facebook groups with 100,000 members disappear. Apps that documented rights information vanish from app stores. Encrypted messaging platforms become investigation targets. Users learn that platforms can't be trusted to protect their speech.

This has real consequences. Communities lose organizing capacity. Information goes underground where fewer people access it. People at risk from enforcement lose access to information that could protect them.

But the legal cases also show that resistance is possible. Signal continues operating without making concessions. Government withdrew attempts to unmask anonymous users when actually challenged in court. Courts have tools to stop unconstitutional pressure if platforms force the issue.

The decisions platforms make now will determine whether digital speech is protected by law and principle or controlled by government through regulatory intimidation.

For users, the message is clear: don't passively accept platform compliance with censorship demands. Know your rights. Support organizations defending free speech. Build alternative infrastructure. Document censorship. And pressure platforms to resist government demands that lack proper legal authority.

Free speech survives not because it's automatic but because people fight for it. Digital speech is no exception.

Key Takeaways

- Government officials are using regulatory authority to pressure platforms into removing ICE-related content without court orders, violating constitutional speech protections

- Tech platforms like Meta and Google are complying with removal demands despite lacking clear legal authority, enabling censorship without judicial oversight

- First Amendment law protects speech documenting government activity and community organizing, yet platforms are removing this protected speech

- Legal cases by FIRE and EFF challenge government coercion and seek to expose communications showing how pressure was applied

- Platforms could resist pressure by requiring court orders and maintaining consistent transparency policies, but most are not doing so

Related Articles

- India's New Deepfake Rules: What Platforms Must Know [2026]

- ExpressVPN ISO Certifications & Data Security [2025]

- 6.8 Billion Email Addresses Leaked: What You Need to Know [2025]

- How ICE Shifted From Visible Raids to Underground Terror in Minneapolis [2025]

- OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads, Warns of 'Facebook' Path [2025]

- Telegram Blocked in Russia: How Citizens Are Fighting Back With VPNs [2025]

![Government Censorship of ICE Critics: How Tech Platforms Enable Suppression [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/government-censorship-of-ice-critics-how-tech-platforms-enab/image-1-1770986362304.jpg)