Introduction: The Wyden Siren and America's Surveillance Paradox

There's a strange phenomenon in American politics that's become almost predictable. A senior lawmaker with access to the nation's most classified secrets holds a press conference, issues a vaguely ominous warning about government overreach, and then refuses to explain what they actually know. The public watches, waits, and wonders if something serious is happening behind closed doors.

This has happened repeatedly over the past 15 years, and it's happened so consistently that observers have given it a name: the "Wyden siren."

Senator Ron Wyden, the longest-serving member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, has perfected this particular art form. In recent years, he's sent cryptic warnings about secret surveillance programs, unauthorized intelligence gathering, and what he describes as unconstitutional government activities. The catches? He can't tell you what he's talking about. The information is classified. Even most other lawmakers aren't allowed to know the details.

This creates a fascinating and troubling dynamic. Here's a senior official of the U.S. government, tasked with oversight of the intelligence community, essentially saying "something wrong is happening, but I legally cannot tell you what it is." It's accountability theater mixed with genuine constitutional concern, and it reveals something fundamental about how American surveillance actually works versus how the public believes it works.

In 2025, as surveillance technologies become more sophisticated and the gap between classified and public knowledge widens, understanding this dynamic matters. Not because Wyden is necessarily right about every concern (though his track record suggests paying attention to his warnings is wise), but because it exposes how little visibility citizens actually have into what their government does in their name.

This article explores the landscape of government surveillance, the role of oversight mechanisms, the historical pattern of warnings followed by revelations, and what it all means for privacy and accountability in an increasingly digital world. We'll examine specific cases, understand how classification works, and consider what citizens should know about the gap between official transparency and actual government operations.

TL; DR

- Surveillance Oversight Gap: Senior Intelligence Committee members like Wyden have access to classified programs but legal restrictions prevent them from sharing critical details with the public or most colleagues

- Historical Pattern: Wyden's vague warnings have preceded major revelations, including the Snowden disclosures about NSA phone records and FBI demands for tech company data

- Classification Problem: The government classifies so much information that genuine oversight becomes difficult and public accountability nearly impossible

- Privacy vs. Security Trade-off: Intelligence agencies argue secrecy protects operations; civil liberties groups argue it enables unchecked abuse

- Technology Acceleration: Modern surveillance capabilities (AI analysis, metadata collection, backdoor demands) far exceed public understanding or legal frameworks

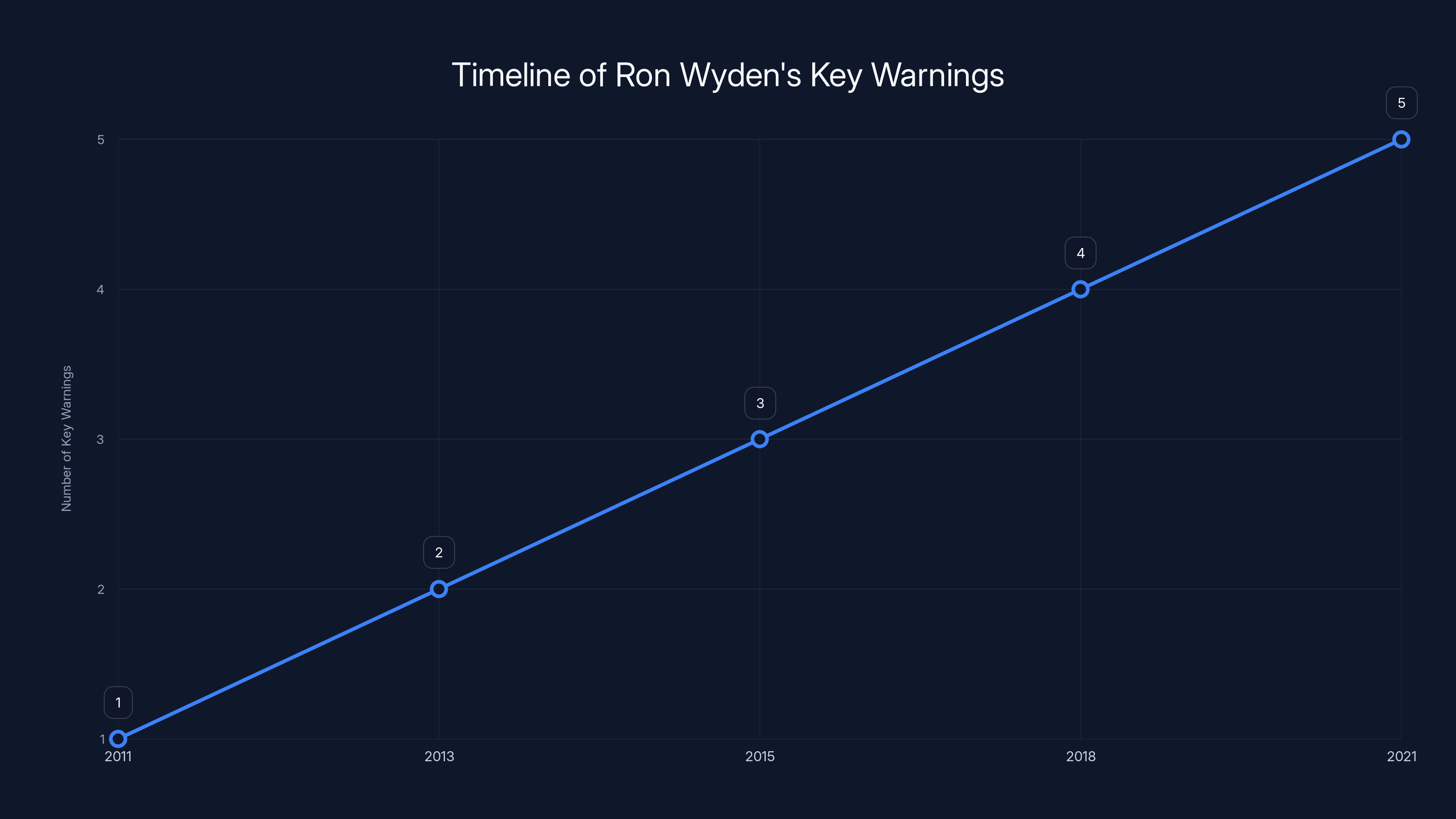

Estimated data shows a steady increase in the number of key warnings issued by Ron Wyden, highlighting his consistent vigilance on intelligence and privacy issues.

Who Is Ron Wyden and Why His Warnings Matter

Ron Wyden isn't your typical alarm-sounding senator. He's not a newcomer to politics, nor is he some conspiracy theorist operating on the fringe of credibility. Since entering the Senate in 1996, Wyden has established himself as one of the chamber's most knowledgeable voices on intelligence and technology policy. More importantly, he has legitimate access to information most people will never see.

As the top Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee, Wyden receives briefings on ongoing classified operations. He reads highly classified reports about cyber intelligence, surveillance methods, and government programs that remain invisible to the public. This access is both his power and his constraint. It makes him one of the few people who actually knows what's happening. It also means he's bound by law not to disclose specifics.

His record of warnings followed by revelations is what makes observers pay attention. In 2011, Wyden cryptically warned about a "gap between what the public thinks the law says and what the American government secretly thinks the law says" regarding the Patriot Act. Two years later, Edward Snowden leaked NSA documents proving Wyden was right. The government had indeed developed a secret legal interpretation of the Patriot Act that allowed mass phone record collection.

That 2011 warning was vague enough that most people missed it. But intelligence experts and civil liberties organizations recognized the pattern. Wyden was essentially saying "the government is interpreting laws in ways the public doesn't know about and wouldn't approve of, but I can't tell you exactly how."

He's done this repeatedly. In recent years, he's warned about federal authorities secretly demanding push notification data from Apple and Google. He's highlighted how the government collects the actual contents of Americans' communications. He's flagged reports he says contain "shocking details" about national security threats that agencies refuse to declassify.

The CIA's response to his latest concerns is revealing. They called it "ironic but unsurprising that Senator Wyden is unhappy," framing his oversight as a "badge of honor" for the agency. This dismissive tone suggests tension between those conducting operations and those tasked with checking them.

What makes Wyden's warnings significant isn't necessarily that he's always right (though his track record suggests he usually is). It's that he represents a structural problem in how America handles surveillance: the people with the most knowledge face legal barriers to transparency, while the public operates with incomplete information.

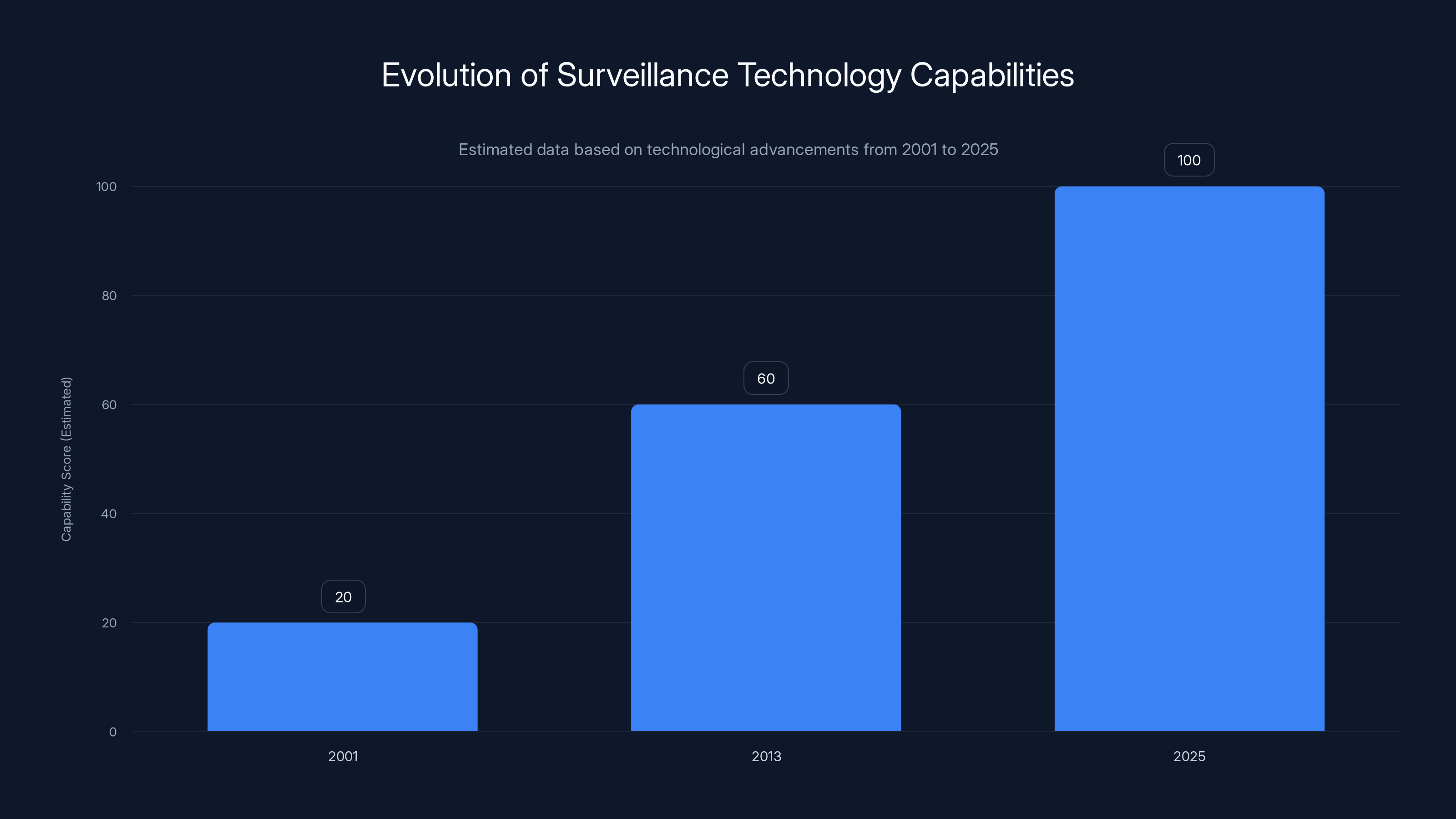

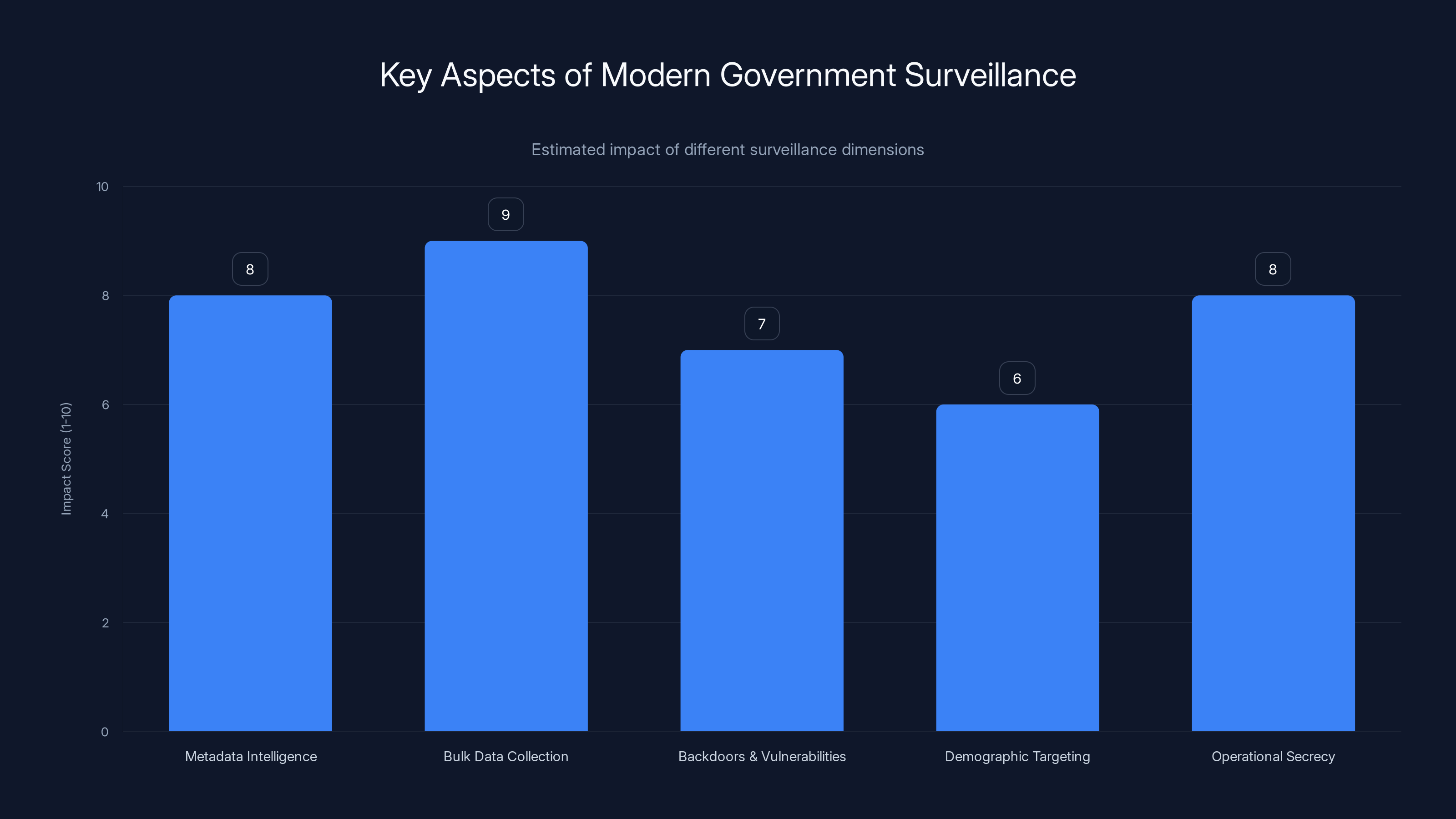

Surveillance technology capabilities have significantly increased from 2001 to 2025, with AI and metadata analysis enhancing data exploitation. Estimated data.

The Snowden Disclosures: When Classified Warnings Became Public Reality

Edward Snowden's 2013 revelations didn't appear in a vacuum. They vindicated years of warnings from people like Wyden who couldn't speak freely about what they knew. Understanding the Snowden releases provides crucial context for why classified warnings matter.

The NSA, through its bulk collection programs, was gathering phone records for hundreds of millions of Americans. Not the contents of calls, but metadata: who called whom, when, and for how long. The government justified this through a secret interpretation of the Patriot Act's Section 215, which allowed collection of business records "relevant" to national security investigations.

The secret interpretation was the key. Publicly, the Patriot Act was supposed to require that targeted surveillance be justified by reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. Secretly, the government had decided that Section 215 allowed the NSA to collect all phone records in bulk, then search through them looking for suspicious patterns.

This was precisely what Wyden had hinted at years earlier. The law, as the public understood it, didn't authorize mass surveillance. The law, as the government secretly interpreted it, absolutely did. That gap between public understanding and classified practice became the centerpiece of the Snowden revelations.

The impact was massive. Congress passed the Freedom Act in 2015, which formally ended the NSA's bulk phone record collection program. But the damage to public trust was already done. Millions of Americans learned that their government had been collecting their communications metadata at scale, authorized by secret interpretations of public law, with minimal oversight from courts or Congress.

What's crucial here is that the Snowden revelations didn't reveal some new capability the government had suddenly developed. They exposed a gap between law and practice that had existed for years. Wyden and a handful of other lawmakers had known about it. They couldn't tell the public. The system designed to protect oversight had failed to prevent abuse.

Classification and the Accountability Problem

Here's the fundamental challenge: you cannot have democratic accountability for activities that are classified. If the government keeps something secret, the people can't vote on it, journalists can't investigate it, and citizens can't organize against it. The only oversight available is through elected officials with security clearances, and those officials face legal restrictions on what they can communicate.

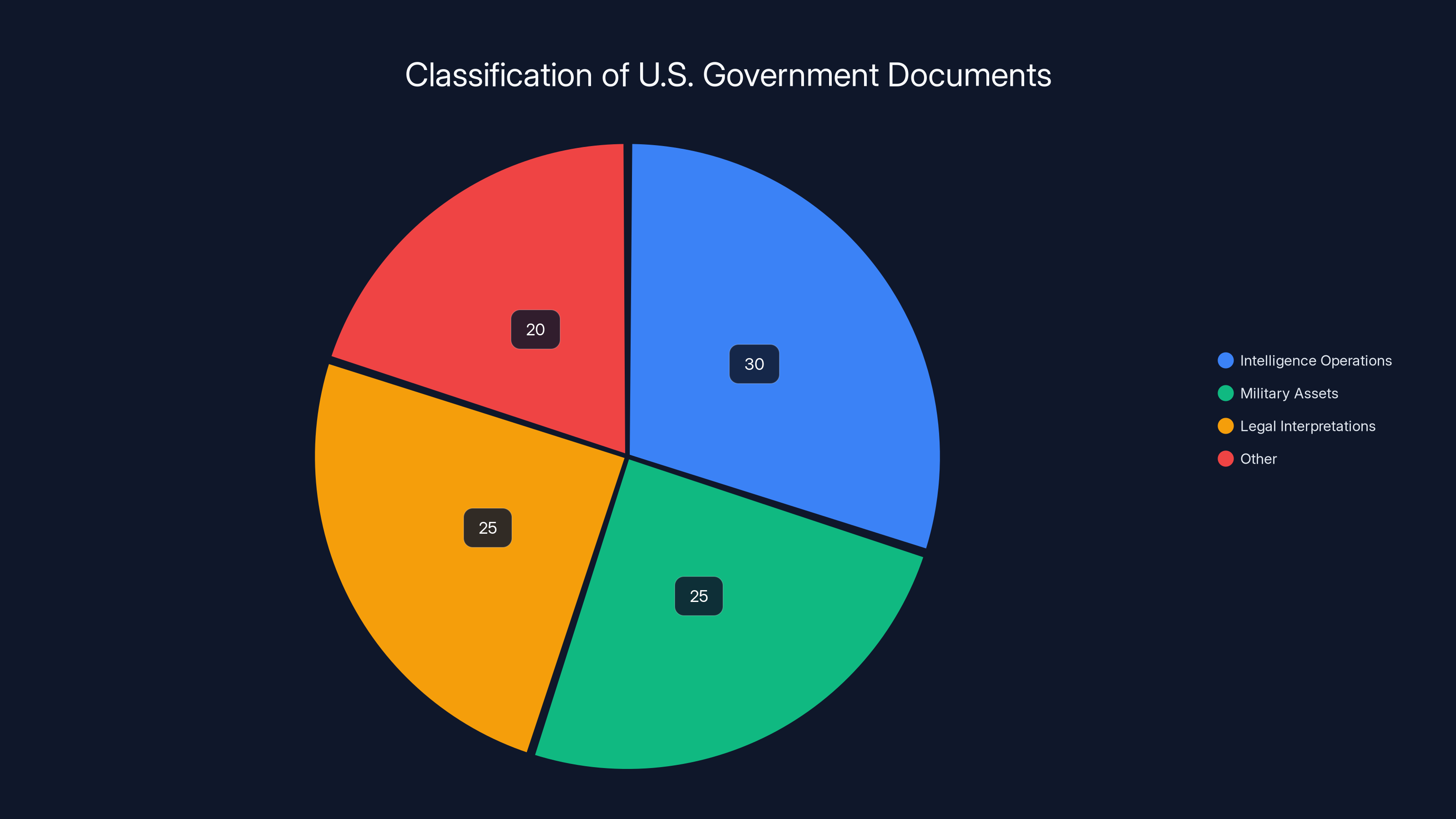

The U.S. government classifies an enormous amount of information. In recent years, the government has classified over 50 million documents annually. Some of this makes sense: details about sources and methods in ongoing intelligence operations, the locations of military assets, etc. But much of it involves information about the government's interpretation of laws, the scope of its own authorities, and the legal justifications for programs that affect American citizens.

Wyden isn't alone in recognizing this problem. Multiple reforms have attempted to address it. The Intelligence Authorization Act has required some classified programs to be disclosed in summary form to Congress. The executive branch has declassified documents about past programs like COINTELPRO and MKUltra, though typically only after public pressure or legal actions.

But the gap remains. Current surveillance programs operate under classified legal interpretations. When agencies decide to collect certain types of communications or data, they often do so under secret law. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which approves some surveillance operations, functions entirely in secret. Even summaries of its decisions are often classified.

This creates a system where:

- The public knows less than they should: Major surveillance programs operate under secret legal authorities that citizens don't consent to because they don't know about them

- Oversight is inadequate: Even classified oversight through Congress can't be fully effective if information is compartmentalized and lawmakers can't discuss findings

- Technology moves faster than policy: New surveillance capabilities (AI-powered analysis, backdoor demands, metadata exploitation) emerge faster than legal frameworks can address them

- Agencies can define their own authorities: When interpretations are secret, agencies have significant latitude to interpret laws broadly

Wyden's warnings highlight this precise problem. He can't tell the public what's wrong. He can flag that something is wrong. But he can't catalyze the public debate and democratic response that would be necessary to address it.

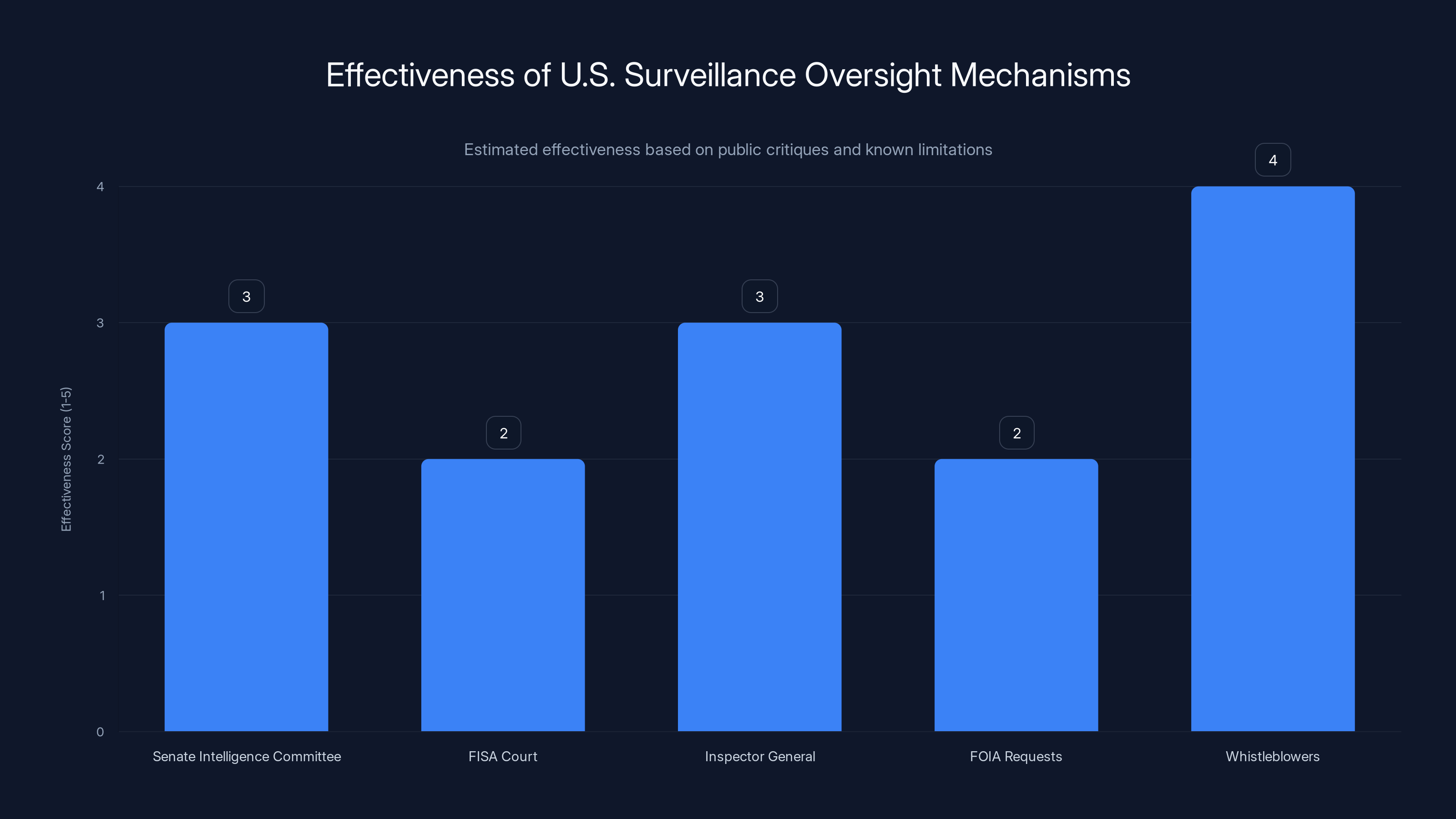

Estimated data suggests that whistleblowers are slightly more effective at revealing surveillance overreach compared to formal oversight mechanisms, which face significant limitations.

Secret Legal Interpretations: When the Law Means Something Different Than You Think

One of the most troubling patterns Wyden has highlighted is how the government develops secret legal interpretations of public laws. These interpretations can be radically different from what the law's text seems to say, and they can authorize surveillance activities the public never imagined were legal.

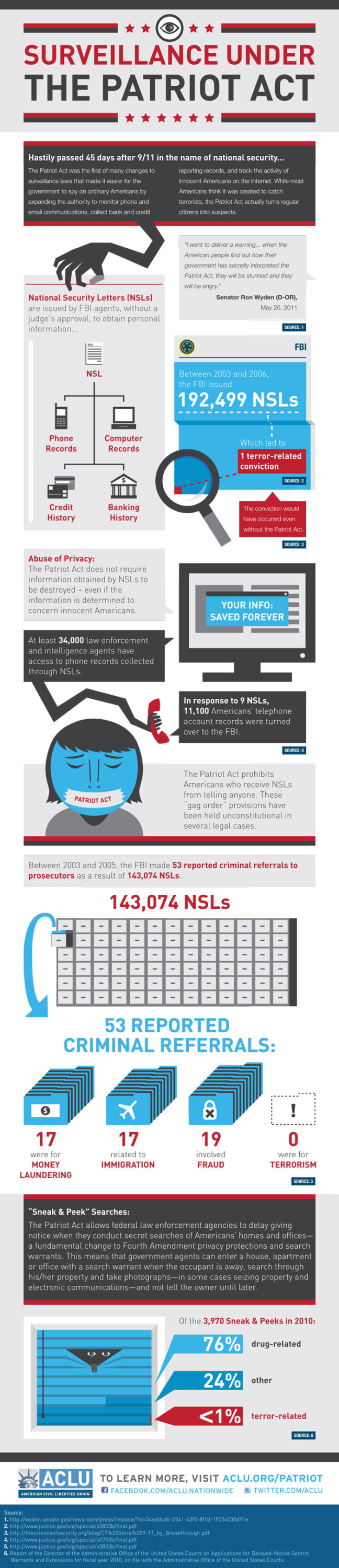

The Patriot Act provides the clearest example. When Congress passed the Patriot Act in 2001, it included Section 215, which allowed the FBI to obtain business records relevant to terrorism investigations. The plain language suggests this should be targeted: the FBI needs to justify that the records are relevant to a specific investigation.

But the government's secret interpretation concluded that "relevant" meant the NSA could gather all phone records in bulk, on the theory that the bulk data was potentially relevant to some counterterrorism investigation somewhere. This interpretation turned a law that seemed to authorize targeted collection into a program enabling mass surveillance.

The legal theory wasn't entirely unreasonable, but it involved stretched interpretations of ordinary words. "Relevant" stopped meaning something the government needed to justify case-by-case and became something defined by the government as a whole as "potentially useful to future investigations."

This pattern appears repeatedly. The government develops interpretations of laws that:

- Authorize collection of data the laws' language doesn't clearly permit

- Classify the interpretation itself as secret

- Prevent public debate about whether the interpretation is correct

- Create a gap between what the government can actually do and what the public thinks the law allows

Wyden has flagged this happening with FBI demands for push notification data from tech companies. The government apparently demanded that Apple and Google turn over push notifications (which reveal who's communicating with whom and potentially what they're communicating about) without public disclosure that this was happening.

The Expanding Surveillance Technology Landscape

Wyden's warnings become more urgent when you understand how surveillance technology has evolved. In 2001, when the Patriot Act passed, collecting the phone records of an entire nation was technically challenging and expensive. By 2013, when Snowden revealed the program, it was routine. By 2025, the technical capabilities are far more sophisticated and troubling.

Modern surveillance involves:

AI-Powered Analysis: The NSA and other agencies now use machine learning to identify patterns in surveillance data. Instead of human analysts looking for suspicious activity, algorithms scan massive datasets looking for anomalies. This happens at scale and speed that was impossible a decade ago. An AI system could identify patterns in communications metadata that humans would never notice, raising questions about bias and false positives.

Metadata Exploitation: Metadata seems innocent—just phone records or email headers. But metadata, when analyzed at scale, reveals incredibly intimate information. Whom you call, when, and for how long reveals your social network, your habits, your relationships, your health conditions (if you're calling doctors), and your political beliefs. Modern analysis can infer all of this from metadata alone.

Backdoor Demands: Intelligence agencies have pressured technology companies to build backdoors into encrypted communications, claiming they need access for investigations. This involves secret demands for data and secret agreements about how tech companies must handle government requests.

International Data Flows: Communications flow through international cables. The NSA collects some communications at landing points where international cables enter U.S. territory. This involves collecting Americans' communications along with foreign targets, raising questions about incidental collection.

Smartphone and App Data: Modern phones track location, communications, browsing, and app usage. Intelligence agencies can access some of this data through legal process and some through secret agreements with tech companies.

Each of these technologies was nascent or nonexistent when the legal frameworks governing surveillance were developed. The Constitution's Fourth Amendment was written assuming searches would be of physical spaces. Wiretapping emerged in the 20th century as a new capability that required new legal rules. But those rules assumed human review and targeted applications.

None of the legal frameworks adequately address AI-powered analysis of billions of data points, or the implications of metadata collection at scale, or the security implications of deliberately weakening encryption. Wyden's warnings partly reflect that the legal and technological worlds have diverged. The government has capabilities the law doesn't clearly authorize and the public doesn't know about.

Estimated data shows bulk data collection and metadata intelligence as having the highest impact on modern surveillance capabilities.

Oversight Mechanisms: Are They Working?

The U.S. has multiple mechanisms supposedly designed to oversee surveillance:

The Senate Intelligence Committee (where Wyden sits) receives classified briefings and is supposed to review ongoing programs. But the committee's reviews are limited. Not all programs are fully briefed. Details are compartmentalized. And the committee's findings are classified, preventing public debate.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court approves some surveillance applications. But it operates entirely in secret. Judges never hear from civil liberties advocates or targets of surveillance. Only government lawyers present arguments. The court has approved vast majorities of applications it has reviewed.

The Inspector General within the intelligence agencies investigates complaints. But inspector general reports on surveillance are often classified, and the inspector general cannot prosecute or prevent operations they find problematic.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests allow the public to request documents from the government. But national security documents are routinely withheld under exemption (b)(1), which allows agencies to keep anything classified as secret. Releasing even summaries of surveillance programs is often denied.

Whistleblowers like Edward Snowden have sometimes exposed programs the formal oversight mechanisms missed or failed to stop. But whistleblowing involves criminal risk and offers limited recourse.

None of these mechanisms has proven adequate to prevent government surveillance overreach. The Snowden revelations showed that even the NSA's inspector general was aware of concerns about the bulk phone collection program but couldn't stop it. The FISA Court has approved mass surveillance programs. The Intelligence Committee has been briefed on programs later revealed to be controversial.

Wyden represents a system of oversight that's trying to function despite enormous constraints. He has access to information, constitutional concerns, and a platform. But he can't communicate freely. He can't organize the public pressure that would be necessary to force change. He can only hint and warn and hope that his track record of being right makes people take his warnings seriously.

This is a fragile system. It depends on individual lawmakers having both integrity and courage, on them being willing to use whatever tools they have to push back against overreach, and on the public recognizing when those warnings should prompt attention. It's not a reliable mechanism for preventing surveillance abuse.

The Tech Company Surveillance Angle: Cooperation and Secrecy

One area where Wyden's warnings have been particularly pointed involves how the government demands data from technology companies. This represents a different category of surveillance than direct government collection, but it's no less important.

Tech companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook collect vast amounts of user data. They have access to communications, location information, social networks, and behavioral patterns. The government has incentives to access this data for law enforcement and intelligence purposes.

For many years, the government used traditional methods: warrants, subpoenas, and court orders. But Wyden has flagged that agencies also make secret demands, often with gag orders preventing companies from disclosing that the demands occurred.

The push notification case Wyden highlighted is illustrative. Push notifications are messages sent to your phone about incoming calls, messages, or app activity. They reveal who's communicating with you. The FBI apparently demanded access to this data from Apple and Google. The government classified the demands as secret and forbade the companies from publicly disclosing that such demands existed.

This creates a situation where:

- The government demands data from tech companies

- Demands are made under secret legal authorities or secrecy agreements

- Companies can't tell users their data was requested

- The public doesn't know this data collection is happening

- No democratic process addresses whether this is acceptable

Apple and Google have published transparency reports about government data demands in recent years, but these are limited. They show the number of demands but often can't provide details about what information was sought or what legal basis was claimed due to government restrictions.

Wyden's concern about push notifications specifically relates to national security letters (NSLs), which are administrative subpoenas issued by FBI field offices without court review. NSLs can require production of business records relevant to terrorism or foreign intelligence investigations. They come with gag orders. Recipients can't tell anyone, including affected parties, that NSLs were served.

The government argues NSLs are necessary for efficient investigations. Civil liberties groups argue they bypass the warrant requirement and enable fishing expeditions. Wyden has flagged that the scope of NSL demands has expanded beyond historical practice.

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of classified documents involves legal interpretations and other non-operational information, highlighting the challenge of democratic accountability.

The Broader Trend: Data Collection and Digital Privacy

Wyden's warnings about classified programs don't exist in isolation. They're part of a broader trend where government surveillance capacity has expanded enormously while legal frameworks have struggled to keep pace.

This involves several dimensions:

Metadata Becomes Actionable Intelligence: Governments have learned that metadata is often more useful than content. Knowing who someone is communicating with, when, and from where reveals patterns and social networks. This can identify suspects, reveal relationships, and map organizations. Modern AI analysis makes metadata even more valuable because algorithms can identify patterns humans would miss.

Volume Becomes a Feature, Not a Bug: Rather than trying to target surveillance to specific suspects, intelligence agencies have concluded that bulk collection is more efficient. Even if 99.9% of the data is irrelevant, the 0.1% that matters is captured. Modern storage and analysis makes this feasible.

Backdoors and Vulnerabilities: The government has pressured companies to build backdoors into encryption or to weaken security so government can access data. These backdoors create security risks for everyone. If a backdoor exists for government, it exists for criminals and foreign governments too.

Demographic Targeting: Modern surveillance doesn't just target individuals; it can target demographics, communities, or political groups. AI systems analyzing patterns can flag entire populations for enhanced surveillance.

Operational Secrecy: The government has become more sophisticated at hiding surveillance. Intelligence operations now hide in classified legal authorities and secret agreements. This prevents the public debate that would normally constrain government power.

Wyden's warnings highlight that this isn't hypothetical. It's happening. Senior lawmakers with direct access to these programs are concerned enough to issue warnings despite the legal constraints on what they can say.

The Privacy vs. Security Debate: Is It a Real Trade-Off?

Intelligence agencies argue that surveillance is necessary for national security. Secret programs are secret because disclosing them would compromise operations and put sources at risk. Restricting government surveillance would make it harder to detect terrorism and foreign threats.

Civil liberties advocates counter that surveillance has expanded far beyond what's necessary for genuine security. Secret programs are secret because they involve activities the public wouldn't approve of. And historical evidence shows that surveillance capacity tends to be misused—against dissidents, minorities, and political opponents—once it exists.

Wyden occupies an interesting position in this debate. He's not arguing against all government surveillance. He has access to classified briefings and presumably agrees that some intelligence operations are necessary. His concerns are about scope, legality, and accountability. He's flagging cases where he believes the government has gone beyond what law permits, or where programs operate under secret interpretations that the public would reject if they knew about them.

The debate is often framed as though security and privacy are inversely related: more surveillance means more security, less surveillance means less security. But this assumes all surveillance is equally effective and that oversight mechanisms don't matter.

Evidence suggests a more complex picture. Broad surveillance isn't necessarily more effective than targeted surveillance. The NSA's bulk phone collection program, revealed by Snowden, was not responsible for detecting most terrorism plots. More targeted approaches, combined with good intelligence work, prevented most attacks.

Furthermore, privacy and security are related in complex ways. Surveillance programs that operate in secret and without accountability can themselves become security threats. Backdoors demanded of companies for government access create vulnerabilities that criminals exploit. Classification systems that hide government legal interpretations prevent public debate that would improve policy.

Wyden's position, implicitly, is that you can have effective national security without operating a mass surveillance state. But you need oversight, transparency where possible, and compliance with what the law actually says (rather than secret interpretations).

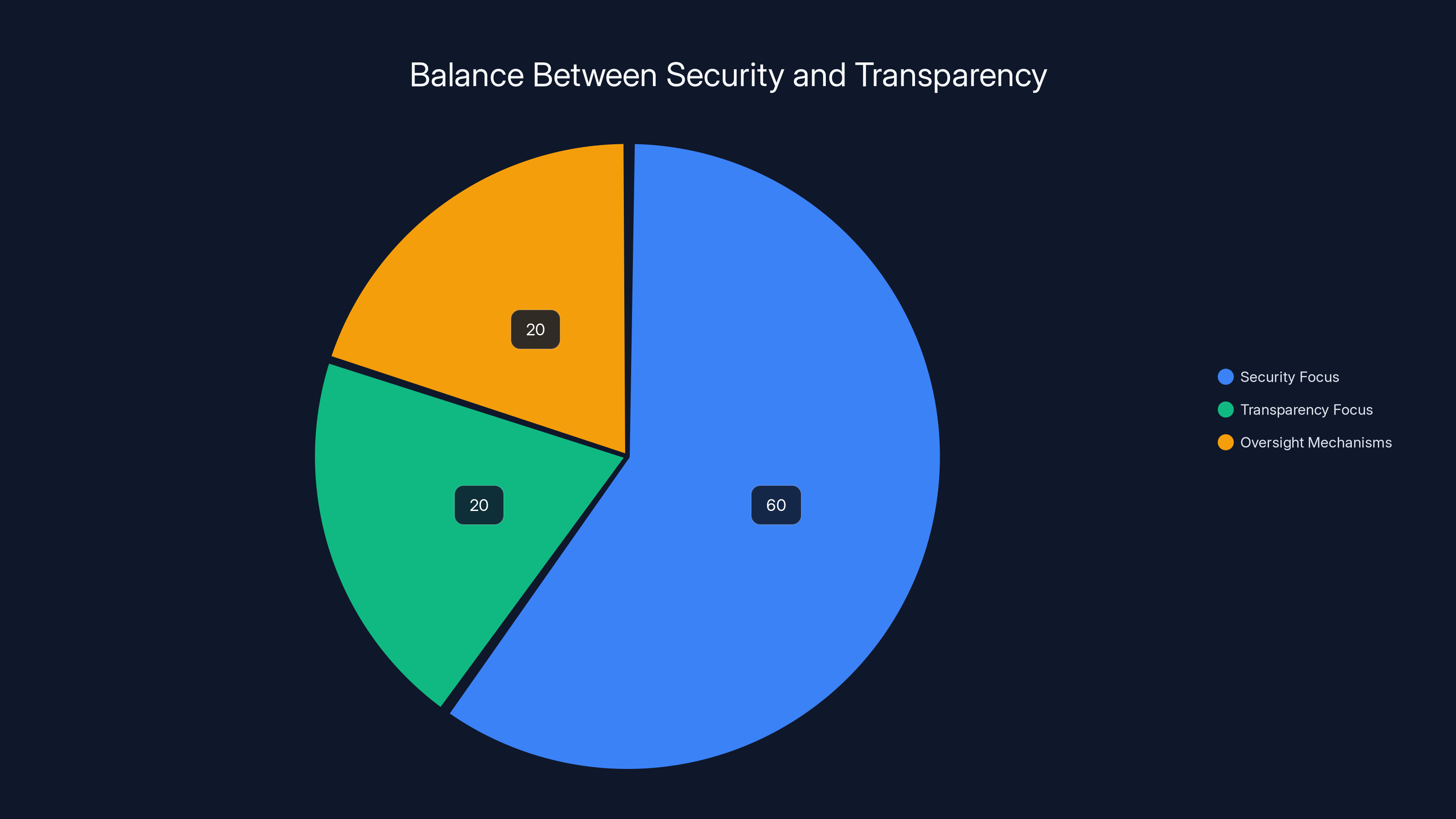

Estimated data suggests a significant focus on security over transparency and oversight in U.S. intelligence operations, highlighting the need for reform.

How Secret Programs Get Revealed: The Whistleblower Pipeline

If oversight mechanisms like Congress and inspectors general aren't always effective, how do secret programs eventually become public? Often through whistleblowers.

Edward Snowden is the obvious example. He had access to NSA materials as a contractor, recognized what he believed was unconstitutional mass surveillance, and decided to leak documents to journalists. This resulted in the most significant surveillance revelations in recent history.

But Snowden isn't unique. The post-Snowden era has seen numerous whistleblowers from the intelligence community:

Reality Winner leaked the NSA's assessment of Russian interference in the 2016 election. She faced prosecution and spent years in prison.

Jeffrey Scudder provided information about NSA surveillance activities to journalists. He also faced legal consequences.

William Binney and other NSA whistleblowers have spoken publicly about mass surveillance programs and constitutional concerns.

Various contractors and government employees have provided information to media outlets and watchdog organizations about classified programs.

Whistleblowers serve a critical function: they bypass the classification system and provide the public with information about what their government is doing in secret. But the system punishes them harshly. Whistleblowers face prosecution under the Espionage Act, imprisonment, financial ruin, and permanent exile (as Snowden experienced).

This creates a perverse incentive structure. The government wants to keep programs secret. When whistleblowers reveal them, the government prosecutes the whistleblowers rather than addressing the underlying concerns about the programs themselves. This discourages future whistleblowing and reinforces secrecy.

Wyden's warnings are, in effect, a inside-the-system alternative to whistleblowing. He's using whatever tools he has as a senator to alert the public that something is wrong without violating his security oath. But even this approach is constrained. He can't say what's wrong. He can only hint.

International Cooperation and Surveillance

American surveillance isn't conducted in isolation. The U.S. works with allied governments to conduct signals intelligence and collect information about communications. This international dimension creates additional complexity.

Programs like the "Five Eyes" arrangement involve intelligence sharing between the U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. These countries conduct surveillance and share information, creating a web of intelligence cooperation.

One implication is that information collected on Americans can flow to foreign governments through these partnerships. Another implication is that intelligence from foreign sources can be used domestically.

Wyden has raised concerns about how information collected by allies under different legal rules can flow back to the U.S. The legal constraints on American surveillance might be evaded by having allied governments collect information and then sharing it.

This involves what's sometimes called "third party doctrine" expansion. Normally, the government needs a warrant to search your communications. But if a foreign government conducts that search and provides the information to the U.S., the question becomes more complex: did the Fourth Amendment apply to surveillance conducted by a foreign government?

These international dimensions make surveillance oversight even more difficult. Congress can oversight American agencies, but it has limited ability to oversight foreign governments. The public has even less visibility into international intelligence cooperation.

The Role of Civil Liberties Organizations

Organizations dedicated to civil liberties and digital rights have become crucial for highlighting surveillance concerns and pushing back against expansion.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, American Civil Liberties Union, Center for Democracy and Technology, and others:

- File FOIA requests to extract classified information

- Litigate cases challenging surveillance authorities

- Publish research and reports about programs

- Advocate for legal reforms

- Monitor government surveillance activities

- Provide technical resources for secure communications

Wyden, in many cases, works with these organizations. His warnings often precede or accompany reports from civil liberties groups providing more detailed analysis.

These organizations fill gaps that the formal oversight system leaves open. They operate with public transparency, unlike the classified committees. They can organize public pressure, unlike individual lawmakers bound by security oaths. They can litigate constitutional issues in court, forcing public arguments about whether surveillance is legal.

But they operate with limited resources compared to government agencies. They depend on public support and donations. And they can't access classified information the way Congress can. Their advocacy is valuable but not sufficient on its own.

Modern Surveillance in the AI Era: New Capabilities, Old Laws

By 2025, the surveillance landscape has evolved significantly from the Snowden era. Modern capabilities involve artificial intelligence, behavioral analysis, and predictive systems that go far beyond simple data collection.

Predictive Policing: AI systems analyze historical crime data to predict where crimes will occur and who is likely to commit them. When used for surveillance, these systems can flag individuals for enhanced monitoring based on algorithmic assessments of risk. The accuracy and bias implications are disputed.

Behavioral Analysis: Machine learning systems can identify patterns in communications and behaviors that suggest someone is engaged in illegal activity, terrorism, or foreign intelligence work. But these systems can also produce false positives and can be biased against certain groups.

Face Recognition: The government has access to massive databases of facial images (driver's licenses, passport photos, etc.) and can match faces in video footage to these databases. This enables mass identification from uncontrolled surveillance video. The accuracy varies significantly by demographics.

Location Tracking: Modern phones and devices transmit location constantly. The government can access historical location data from telecom providers and can conduct real-time location tracking with warrants. The volume of location data being collected is vast.

SIGINT and IMINT: Signals intelligence (SIGINT) and imagery intelligence (IMINT) involve vast automated systems that collect and process communications and satellite imagery. The scale is difficult to comprehend—petabytes of data daily.

All of these capabilities involve interpretation. The AI models that analyze this data make judgments. Those judgments reflect the values and biases of the people who built them. When government agencies deploy these systems at scale without transparent review, the implications are significant.

Wyden's concerns about CIA activities in 2025 likely involve some combination of these modern capabilities. The substance remains classified, but the pattern is clear: surveillance technology is advancing faster than legal and ethical frameworks.

What Citizens Should Know About Government Surveillance

Given the complexity and secrecy surrounding these issues, what should ordinary Americans understand about their own exposure to government surveillance?

Your Phone Records Can Be Collected: Even after the end of the NSA's bulk phone collection program, telecom providers retain phone records and government can request them with a warrant or sometimes with a National Security Letter. Your pattern of calls reveals a lot about your life.

Your Location Is Tracked: Your phone broadcasts location information constantly. Government can purchase location data from brokers or request it from telecom providers. This has been used for law enforcement and intelligence purposes without warrants in some cases.

Your Internet Activity Is Monitored: The government collects some internet traffic at border points where international cables land. Your communications with foreign contacts are likely monitored. Communications with domestic contacts can be collected if under court order or if they're about foreign intelligence matters.

You Have Limited Visibility: You don't know when government is collecting your information. Warrants can be secret. National Security Letters include gag orders. Intelligence activities are classified.

Reform Is Possible But Difficult: Legal reforms that restricted surveillance (like the Freedom Act) were only possible because whistleblowers exposed programs. Without public knowledge, reform doesn't happen. Supporting civil liberties organizations and staying informed increases the likelihood of change.

The Path Forward: What Would Meaningful Reform Look Like?

Wyden and other advocates for surveillance reform have proposed various approaches:

Transparency Reporting: Require companies and government agencies to publish detailed reports about surveillance requests and activities, without compromising security. This allows the public to understand the scale and scope of surveillance.

FOIA Improvement: Reduce the ability to withhold information under national security exemptions. Establish stronger requirements for agencies to demonstrate why disclosure would genuinely compromise security.

FISA Court Reform: Open the FISA Court to civil liberties perspectives. Require that constitutional arguments be presented, not just government arguments. Publish more decisions and legal reasoning.

Encryption Backdoor Resistance: Oppose government pressure on companies to weaken encryption or build backdoors. Instead, develop secure methods for law enforcement to conduct investigations without undermining overall security.

AI Surveillance Oversight: Establish requirements for government agencies to disclose when they're using AI systems for surveillance, to audit those systems for bias and errors, and to allow independent review.

Congressional Oversight Strengthening: Give more Intelligence Committee members access to classified information about programs, allow them to discuss findings more freely, and empower them to prevent overreach.

Whistleblower Protection: Reduce legal penalties for whistleblowers who expose surveillance they believe is illegal or unconstitutional. Create pathways for whistleblowing without criminalization.

None of these reforms would eliminate surveillance. But they would make it more transparent, more accountable, and less likely to be abused.

The deeper challenge is cultural and structural. American government is built on secrecy in intelligence matters. The assumption is that security requires secrecy. Changing that requires building consensus that transparency and oversight are compatible with security—that in fact, oversight and legality improve security by preventing abuse and maintaining legitimacy.

Looking Ahead: 2025 and Beyond

As we move deeper into 2025, several developments will likely influence surveillance and oversight:

Technology Acceleration: AI capabilities will continue advancing. The government's surveillance abilities will continue expanding. The gap between what's legally authorized and what's technically possible will likely widen.

Generational Change: Younger people expect privacy and have built their lives around digital tools. This generational demand for privacy may create political pressure for reform that didn't exist when surveillance programs began.

International Developments: Other countries are developing their own surveillance capabilities. Intelligence sharing arrangements may change. Competition with China and Russia may push American government toward more aggressive intelligence operations.

Tech Company Resistance: Technology companies, facing pressure from users and from regulation in Europe and elsewhere, may increasingly resist government surveillance demands. This could create friction with intelligence agencies.

Legal Developments: Courts may rule on surveillance authorities. New legislation may pass. Whistleblowers may expose programs, triggering reform or retrenchment.

Wyden's warnings should be read as a sign that significant issues remain unresolved. His access to classified information, combined with his willingness to flag problems, makes his concerns worth taking seriously. But structural reform requires public pressure and political will.

The pattern of warnings followed by revelations suggests that in the absence of reform, more will eventually become public. Whether that happens through whistleblowers, FOIA requests, or litigation remains to be seen.

Connecting Government Surveillance to Broader Technology Concerns

It's worth noting that government surveillance doesn't exist separately from commercial surveillance. Tech companies collect similar data for advertising purposes. The distinction between government and private sector surveillance is increasingly blurred.

When the government wants access to tech company data, that data already exists because companies collect it for business purposes. When companies build backdoors for government, they create vulnerabilities that criminals and other governments exploit. When intelligence agencies use commercial surveillance tools, they benefit from capabilities private companies developed.

Meaningfully addressing surveillance requires addressing both government and corporate data collection. It requires understanding how data flows between sectors. And it requires building technological and legal frameworks that protect privacy across all domains.

FAQ

What is government surveillance and how does it differ from law enforcement surveillance?

Government surveillance includes intelligence gathering by agencies like the NSA, CIA, and FBI for national security purposes. It differs from law enforcement surveillance in scope and legal framework. Law enforcement typically targets specific suspects with warrants. Intelligence agencies can conduct broader surveillance based on foreign intelligence or terrorism investigation authorities. Intelligence surveillance often involves classified legal authorities and classified interpretations of laws, making it less transparent to the public.

How does the classification system protect surveillance programs from public scrutiny?

The classification system allows the government to conduct activities in secret and prevent disclosure to the public or most lawmakers. When programs are classified, FOIA requests are denied, public debate is prevented, and only cleared individuals can access information. This creates a system where surveillance can expand without public knowledge or consent. Intelligence agencies argue classification protects sources and methods, but critics argue it also enables abuse without accountability.

What is the role of the Senate Intelligence Committee in overseeing surveillance?

The Senate Intelligence Committee receives classified briefings about ongoing programs and is supposed to provide oversight. Members can review classified material and question intelligence officials. But the Committee's reviews are limited by compartmented information, legal constraints on what members can discuss publicly, and the committee's own security clearances. Findings remain classified, preventing public debate. The Committee can't prevent programs it disagrees with—it can only investigate and report to leadership.

Why can't Senator Wyden simply disclose what he knows about classified programs?

Wyden, like all members of Congress with access to classified information, is bound by law and oath not to disclose classified details without authorization. Violating this obligation carries criminal penalties. This creates a dilemma: he can see problems and flag them generally, but can't explain specifically what's wrong. This is intentional—the system assumes secrecy is necessary for security. Critics argue it prevents the public discourse necessary for democratic accountability.

What happened with the NSA phone records program and why did it matter?

The NSA collected phone records on hundreds of millions of Americans under a secret interpretation of the Patriot Act. The program wasn't revealed to the public until 2013 through Snowden's leaks. It mattered because it showed that the government had secretly reinterpreted laws to authorize mass surveillance the public didn't know about. The program was shut down in 2015, but similar authorities and programs likely continue under different legal authorities.

How does artificial intelligence change government surveillance capabilities and concerns?

AI allows governments to analyze massive datasets looking for patterns humans would miss. Instead of targeted surveillance of specific suspects, AI can scan communications metadata on millions of people looking for anomalies. This increases surveillance capability but also raises concerns about false positives, bias in algorithms, and automated decision-making that affects people without human review. The legal framework for surveillance hasn't adapted to AI-powered analysis at scale.

What is a National Security Letter and why is it controversial?

A National Security Letter (NSL) is an administrative subpoena issued by FBI field offices without court review. It can require disclosure of business records relevant to terrorism or foreign intelligence investigations. NSLs come with gag orders preventing recipients from disclosing that the request occurred. Critics argue NSLs bypass warrant requirements and enable fishing expeditions. They've been issued in vast numbers—over 180,000 NSLs were issued in 2010 alone.

What can individuals do to protect their privacy from government surveillance?

Individuals can use encrypted messaging apps (Signal), encrypted email providers (ProtonMail), and VPNs to increase privacy. They can minimize data shared with companies, use privacy-respecting browser settings, and stay informed about surveillance issues. More structurally, they can support organizations advocating for surveillance reform, contact elected representatives about surveillance legislation, and participate in public debates about privacy and security trade-offs. While technical measures increase privacy, systemic reform requires political action.

How does the Five Eyes intelligence alliance affect American surveillance of citizens?

The Five Eyes (US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) cooperate on signals intelligence and share information. This creates pathways for information about Americans to flow to foreign governments and vice versa. It potentially allows agencies to bypass domestic legal restrictions by having allied governments collect information. The Snowden revelations showed that the Five Eyes partnerships enabled mass surveillance activities that would have been illegal if conducted directly by each country alone.

Why do intelligence agencies resist disclosing information about surveillance programs?

Intelligence agencies argue that disclosure would compromise ongoing operations, reveal sources and methods to foreign governments and terrorist organizations, and reduce the effectiveness of intelligence activities. These are legitimate concerns in some cases. However, civil liberties advocates argue that agencies overclassify information and use security arguments to avoid accountability. The reality is likely somewhere in between: some information genuinely requires secrecy, while other information is classified primarily to avoid public scrutiny.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Tension Between Security and Transparency

Ron Wyden's latest warning about CIA activities fits into a pattern stretching back years. Senior lawmakers with access to classified information have repeatedly flagged concerns about government surveillance and overreach. When they can speak freely about the details (typically after public revelations like the Snowden leaks), their concerns have proven justified.

But the system we've built has inherent limitations. Effective oversight requires knowledge. The most sensitive knowledge is classified. Classification prevents public debate. Without public debate, democratic accountability fails. You end up with a situation where a senior member of Congress can recognize that his government is doing something he believes is wrong, and his only tools are cryptic warnings that most people miss.

This isn't a stable equilibrium. History shows it tends to end with whistleblowers, revelations, and public shock. The Snowden leaks revealed mass surveillance the public didn't know about. The Apple and Google push notification demands, which Wyden has flagged, represent similar dynamics—government overreach operating in secret.

The fundamental question is whether America can develop a system for conducting intelligence operations while maintaining meaningful oversight and accountability. Some secrecy is probably necessary. But the current system errs too far toward secrecy. It allows too much room for overreach and too little opportunity for correction.

Reform would involve increasing transparency where possible, improving oversight mechanisms, empowering Congress to actually constrain surveillance expansion, and building legal frameworks that keep pace with technological capability. It would require that governments sometimes decline to use surveillance capabilities they could technically employ, because the legal authority is lacking or because the public impact would be unacceptable.

Wyden's warnings are valuable because they signal that problems exist. But taking those warnings seriously requires recognizing that the formal oversight system isn't working. It requires supporting reforms that increase accountability. And it requires that citizens, to the extent possible, understand what governments are doing in their name and demand that it be consistent with law and democratic values.

The surveillance capabilities exist. The question is whether they'll be subject to meaningful constraint or whether they'll expand indefinitely under the cover of classification and national security claims. That's ultimately a question for voters, not just lawmakers—but voters can only answer it if they know what they're voting on.

Key Takeaways

- Government, tasked with oversight of the intelligence community, essentially saying "something wrong is happening, but I legally cannot tell you what it is

- We'll examine specific cases, understand how classification works, and consider what citizens should know about the gap between official transparency and actual government operations

- Timeline of Ron Wyden's Key Warnings

- Png)

*Estimated data shows a steady increase in the number of key warnings issued by Ron Wyden, highlighting his consistent vigilance on intelligence and privacy issues

- More importantly, he has legitimate access to information most people will never see

Related Articles

- Nintendo Switch 2 Sales Reveal: Why Japan Crushed Western Markets [2025]

- Best Dystopian Shows on Prime Video After Fallout [2025]

- Who will win Super Bowl LX? Predictions and how to watch Patriots vs Seahawks | TechRadar

- Here are my 4 most anticipated 4K Blu-rays of February 2026 | TechRadar

- Amazon's Melania Documentary: Box Office Reality & Media Economics [2025]

- NYT Connections Game #966: Complete Hints, Answers & Strategy Guide [2025]

![Government Surveillance & CIA Oversight: What We Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/government-surveillance-cia-oversight-what-we-know-2025/image-1-1770403207408.jpg)