GPS Jamming: The Vulnerability Threatening Modern Infrastructure [2025]

It's September 2025, and a Widerøe Airlines pilot is trying to land in Vardø, Norway. The clouds are so thick you can't see the runway. The visibility is terrible. In conditions like this, pilots depend on GPS to guide them down safely. But something's wrong. The GPS signals aren't working. They're being jammed.

Across the fjord, just 40 miles away, Russian military forces are running a massive wargame called Zapad-2025. The exercise simulates conflict scenarios, and part of that simulation involves GPS interference. The pilot has no choice but to abort the landing and fly 70 miles south to Båtsfjord instead.

This isn't a rare incident. GPS disruption in northern Norway near the Russian border is now near-constant. Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine, these interference events have exploded in frequency. And this problem isn't confined to Scandinavia.

GPS jamming is happening globally. It's cheap. It's easy. And it's breaking systems that modern society depends on in ways most people don't even realize.

Why GPS Has Become Our Invisible Infrastructure Backbone

GPS isn't just about getting directions on your phone. That's actually one of the least critical uses.

GPS signals are deeply embedded in infrastructure most people never think about. Power grids use GPS for synchronization. Cell towers rely on GPS-based timing. Banks use it to timestamp financial transactions. Traffic lights adjust their timing based on GPS clocks. Military weapons systems, from guided missiles to drone swarms, depend entirely on GPS positioning and timing.

There's a reason the military built this system in the 1970s. They wanted precision guidance for weapons. They wanted to coordinate operations across continents. When the system was eventually opened to civilians, it became the backbone of modern navigation and timing infrastructure.

"Part of what makes GPS so successful is that it's ubiquitous and it's inexpensive," says John Langer, a GPS expert at the Aerospace Corporation. "Losing GPS would mean losing a lot more than Google Maps."

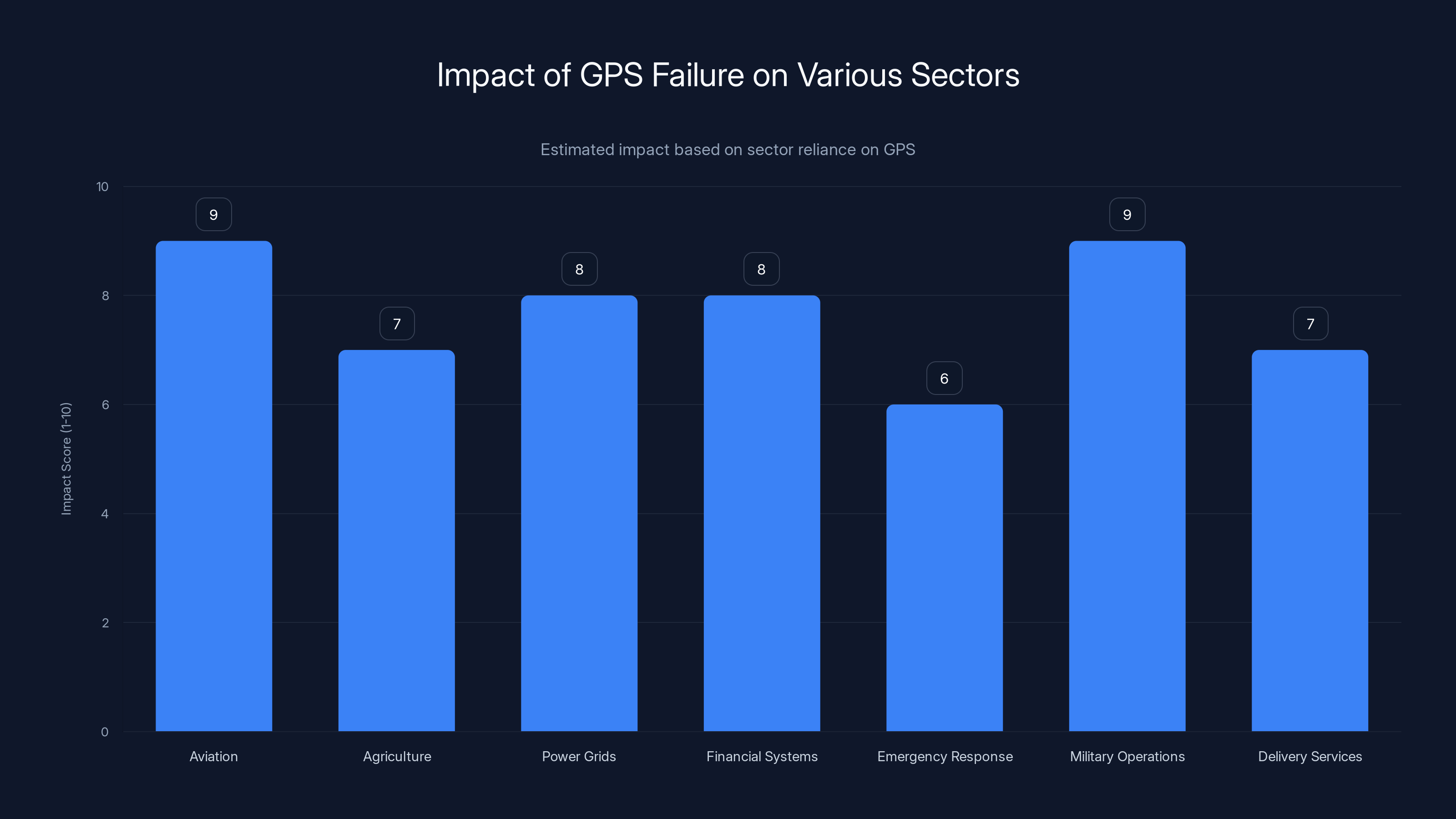

Consider what would happen if GPS went down tomorrow. Your phone wouldn't know where you are. Ride-sharing apps would stop working. Delivery systems would fail. Farmers using precision agriculture GPS-guided equipment couldn't plant crops efficiently. ATMs couldn't sync with banking networks. Electric utilities couldn't maintain grid stability. Emergency responders couldn't coordinate. Military operations would be severely degraded.

The system has become so central to how we operate that most people don't even realize GPS is there. It's like electricity or running water. You notice when it's gone.

Estimated data shows that aviation and military operations would face the highest impact if GPS stops working, with scores of 9 out of 10. Other sectors like agriculture and delivery services also face significant disruptions.

How GPS Works: The Simple System That Changed Everything

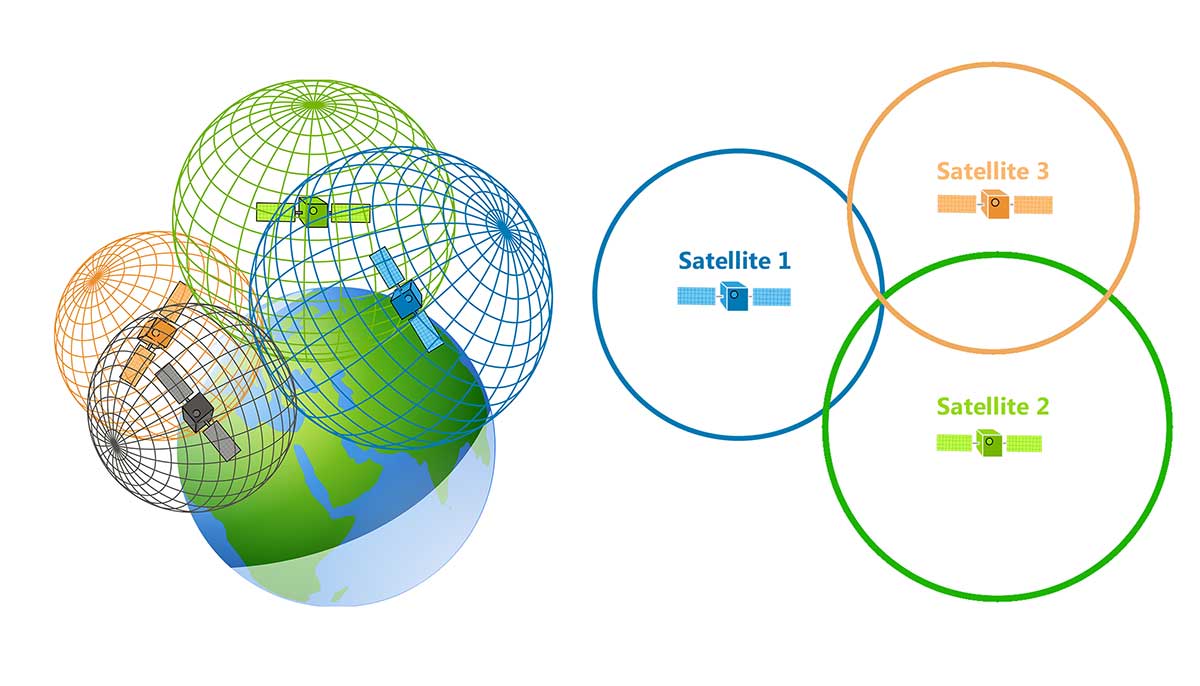

GPS operates on a surprisingly elegant principle. Each satellite carries an atomic clock that's accurate to within nanoseconds. These satellites broadcast their current time constantly.

Your receiver picks up signals from at least four satellites. It knows what time each satellite broadcast their signal. It knows where each satellite was located when they transmitted. By measuring how long the signal took to arrive, your device can calculate its own position through triangulation.

Here's the math behind it: If a satellite is 12,500 miles away and transmits a signal traveling at the speed of light, the signal takes about 0.067 seconds to arrive. Your receiver's clock registers when the signal arrives. The satellite's clock information tells the receiver when the signal was sent. The difference between these times tells you the distance from the satellite.

Do this with four satellites, and you get your precise latitude, longitude, altitude, and time.

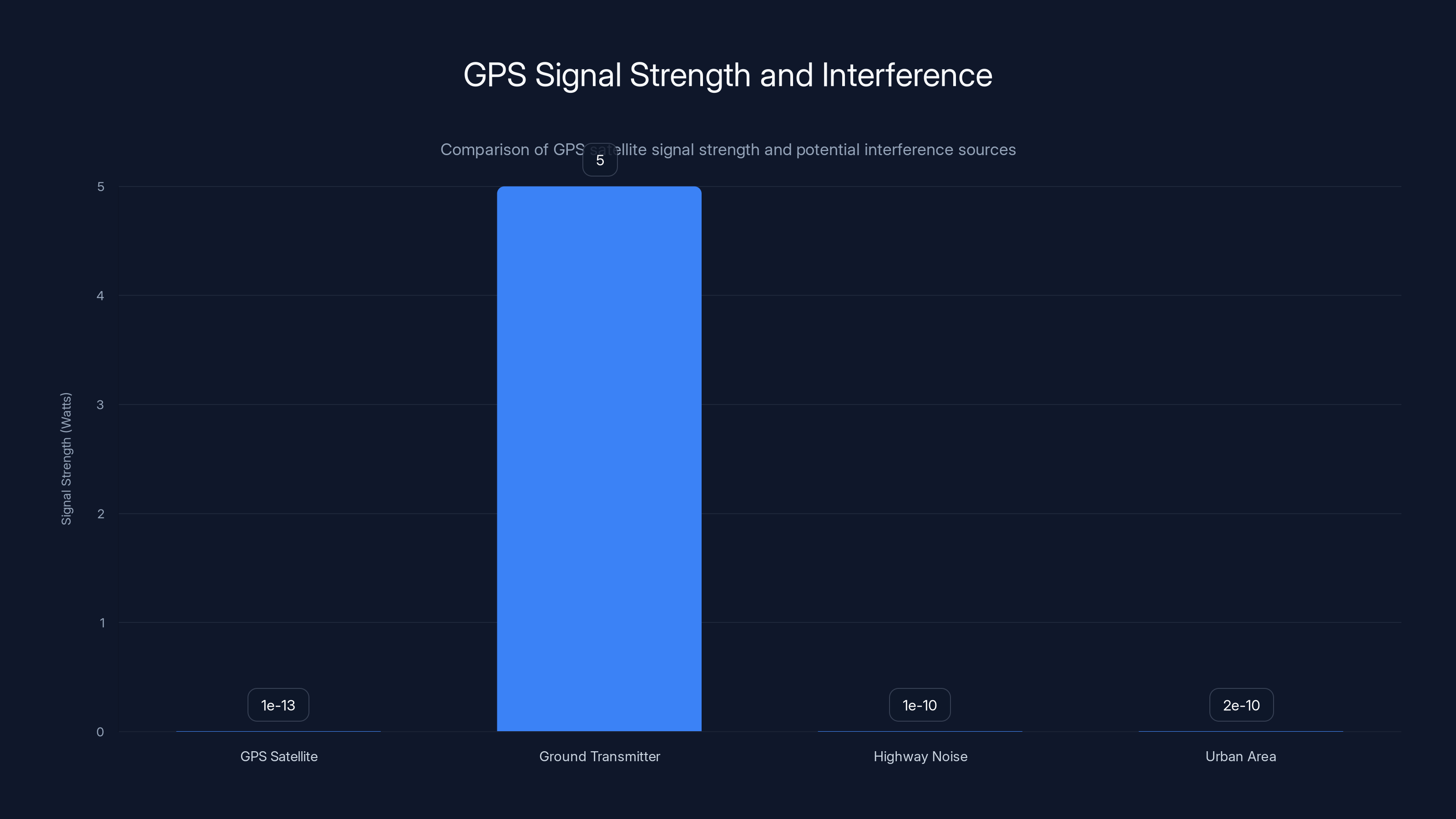

That's the elegant part. The vulnerable part is that this signal is incredibly weak. GPS satellites are 12,550 miles up. Their transmitters only produce about 50 watts of power. By the time that signal reaches Earth, it's essentially a whisper trying to compete with the noise of a highway.

A ground-based transmitter generating just a few watts of power can drown out that whisper. This is GPS jamming.

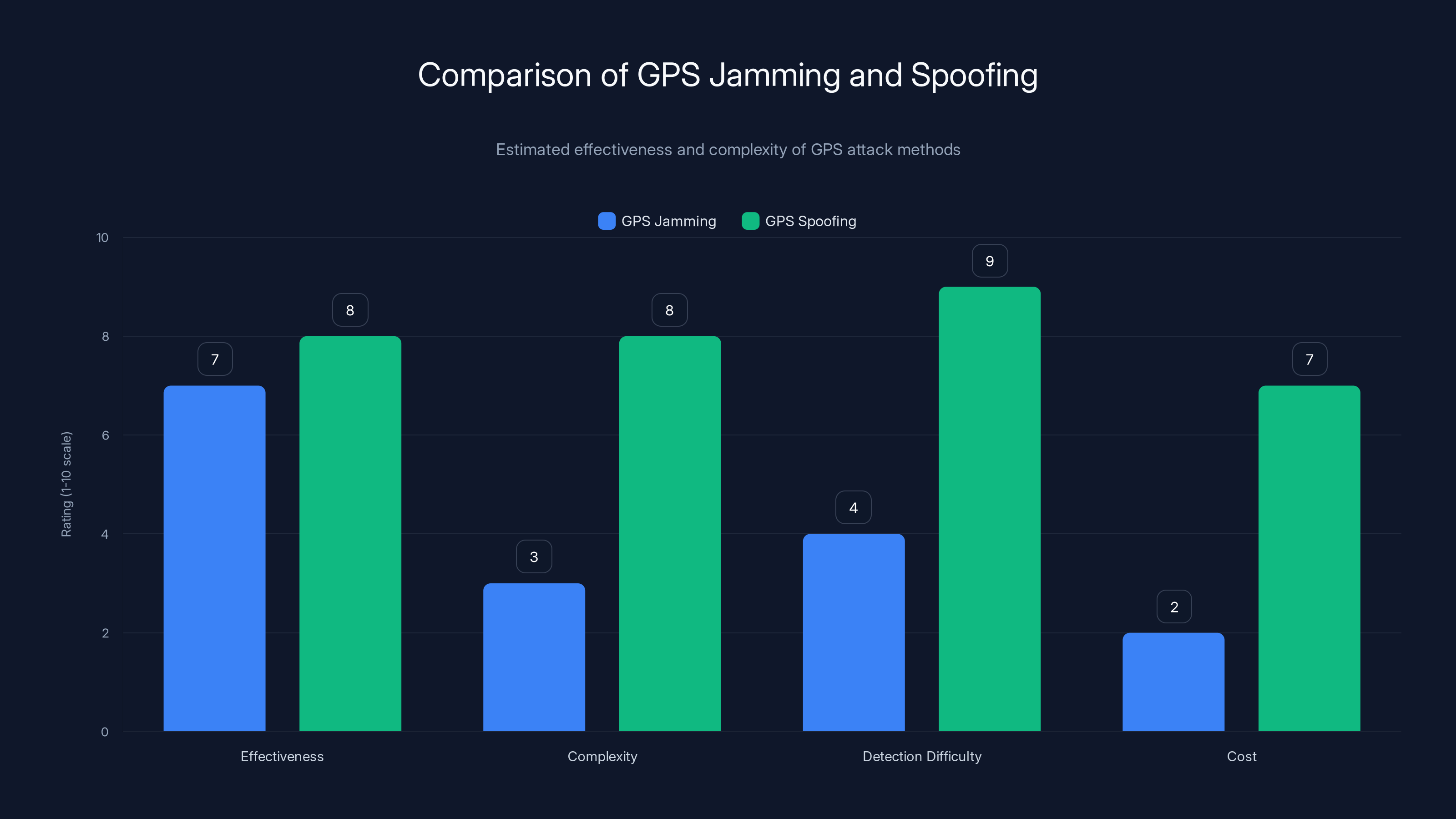

GPS spoofing is more complex and harder to detect than jamming, but both are effective. Jamming is cheaper to execute. (Estimated data)

GPS Jamming: How the Attack Works

Jamming GPS is conceptually straightforward. You transmit a stronger signal on the same frequency that GPS satellites use, overwhelming the legitimate signals.

GPS operates on the L1 frequency band, which is around 1,575 MHz. A jammer broadcasts noise or misleading signals on that frequency. From the receiver's perspective, it's like trying to hear someone whisper during a rock concert. The legitimate signal gets lost in the noise.

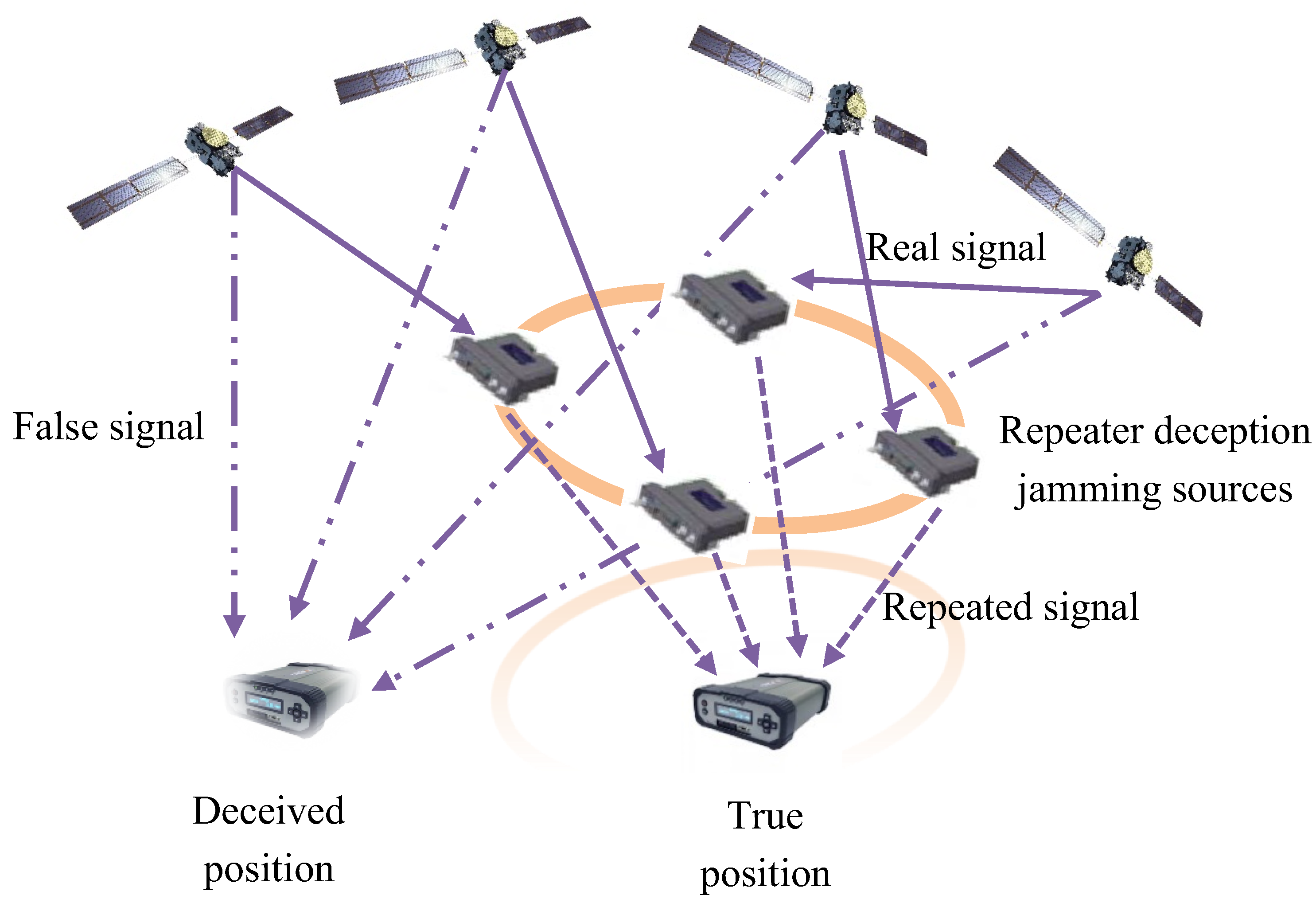

This is different from GPS spoofing, which is trickier but potentially more dangerous.

With jamming, you just disable GPS. With spoofing, you fake the signal. An attacker sends out fake GPS signals that look legitimate but provide false position or timing information. The receiver thinks it's getting real GPS data when it's actually being fed lies.

Imagine a spoofing attack on a guided missile. The missile receives false position data and thinks it's somewhere it's not. It goes off course. Or imagine spoofing a banking system's GPS clock. Transactions get timestamped incorrectly. Financial records become unreliable.

Spoofing is more sophisticated than jamming. It requires understanding the GPS signal format and having the capability to generate authentic-looking signals. But it's also much harder to detect because the receiver thinks everything is working normally.

Jamming is cruder but still effective. It just kills GPS reception entirely.

The concerning part is how accessible the technology has become. In the early 2000s, GPS jamming equipment was expensive and specialized. Today, you can build a functional GPS jammer with basic RF (radio frequency) equipment costing a few hundred dollars. Some commercial off-the-shelf systems can jam GPS over a radius of several kilometers.

The Proliferation Problem: Why GPS Jamming Is Getting Worse

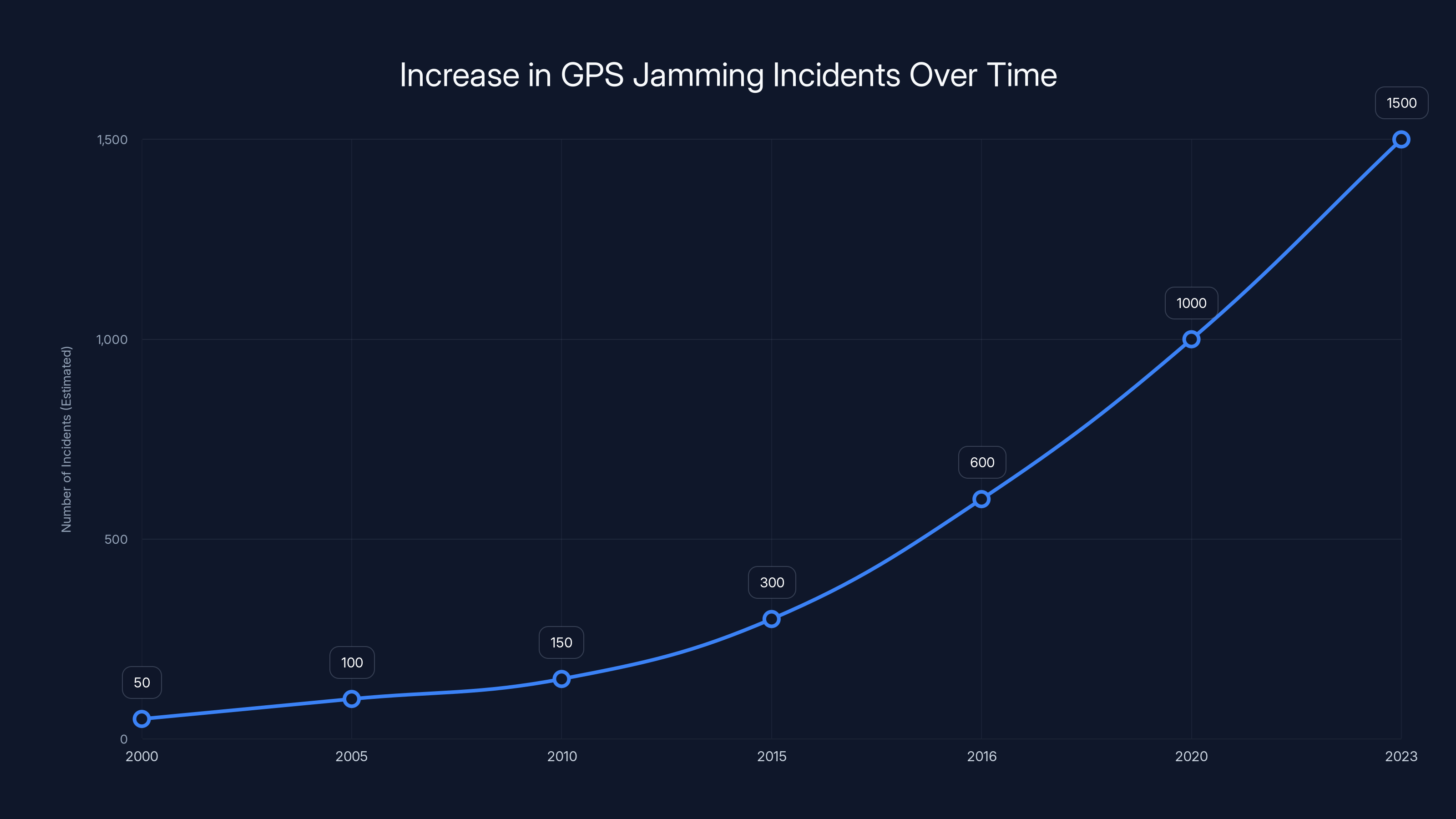

GPS interference incidents have skyrocketed since around 2000, when the technology to jam GPS became cheaper and more accessible.

The real turning point came in 2016 when the augmented reality game Pokémon GO launched. Suddenly, millions of casual players wanted to spoof their location so they could catch Pokémon without leaving their house. The demand for location spoofing tools exploded. Tech-savvy players figured out how to trick their phones into reporting false GPS positions.

"All of a sudden, everyone was interested in spoofing," says Todd Walter, director of the Stanford GPS Lab.

Truck drivers started using GPS jamming and spoofing to hide their location from their employers or to claim they'd delivered cargo when they actually hadn't. This fraud costs the trucking and logistics industries hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Criminal enterprises use jamming to interfere with asset tracking. Stolen vehicles with GPS trackers lose their signals. Expensive shipments that should be traceable simply vanish from monitoring systems.

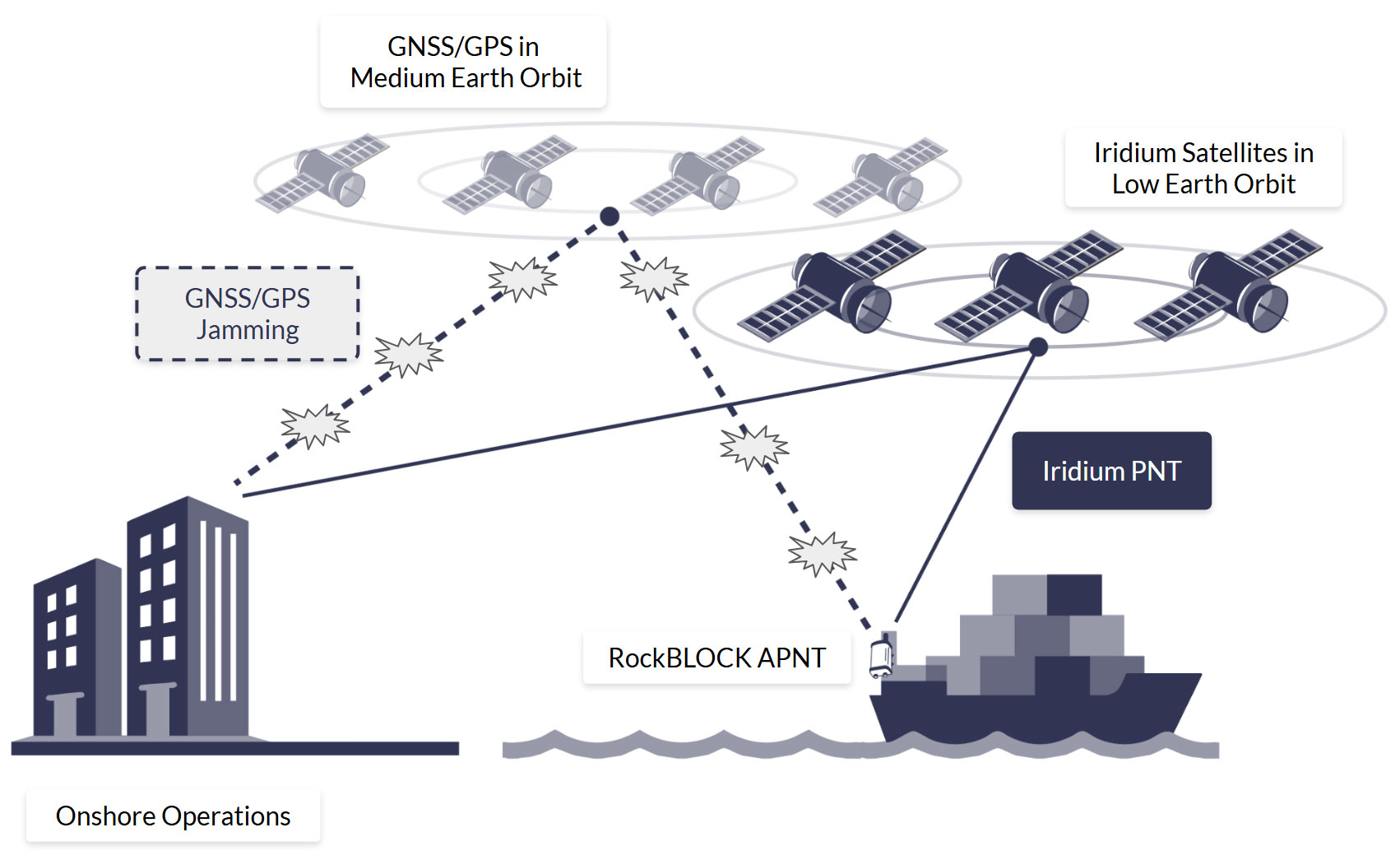

But the biggest driver of GPS interference is military activity. Militaries around the world, including the United States, Russia, and China, regularly conduct GPS jamming and spoofing during exercises and combat operations.

Russia has been particularly aggressive with GPS interference. Since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russian forces have jammed GPS signals over wide areas, both as a military tactic to degrade Ukrainian drone operations and during training exercises.

The effects ripple across civilian infrastructure. Airlines flying near conflict zones lose GPS navigation capability. Power grids struggle with synchronization when GPS timing signals are disrupted. Financial markets depend on GPS-synchronized clocks for trading records, and jamming attacks could corrupt transaction timestamps.

The irony is that GPS was designed to be free and open. The military didn't want to maintain it or charge for it. The U. S. government made the decision to keep it available to civilians because there was no good way to exclude civilian users anyway. The signal just radiates outward to anyone with a receiver.

That openness and ubiquity made GPS incredibly valuable. It also made it inherently vulnerable.

GPS satellite signals are extremely weak by the time they reach Earth, making them susceptible to interference from relatively low-power ground transmitters.

The Consequences: When GPS Fails

When GPS stops working, the effects are immediate and ripple outward in unexpected ways.

For aviation, GPS outages during low-visibility approaches are extremely dangerous. Pilots trained on instrument landings can still land, but it's more stressful and increases the risk of accidents. During the Norwegian GPS jamming incidents, airlines had to divert flights to alternate airports, costing tens of thousands of dollars per incident. Multiply that across hundreds of affected flights, and the economic impact becomes substantial.

For agriculture, GPS-guided tractors and combines are now standard equipment on larger farms. These systems autonomously drive rows with centimeter-level precision, reducing fuel consumption and chemical use. A GPS outage forces farmers to revert to manual guidance, which is less efficient and more expensive. During spring planting season, GPS jamming could cost farms thousands of dollars in lost productivity.

For power grids, GPS provides the timing reference for synchronizing distributed generators and managing load balancing. Without GPS, grid operators have to rely on less accurate timing systems, which can lead to cascading failures if multiple components drift out of sync.

For emergency response, GPS helps dispatchers locate emergency vehicles and helps responders navigate to incidents. GPS outages mean slower response times and potentially lives lost.

For military operations, losing GPS means losing precision-guided weapons capability, losing drone coordination, and losing real-time battle management systems.

For financial systems, GPS-synchronized clocks provide the timestamps for trading records. Without accurate GPS-based timing, banks and stock exchanges can't maintain reliable transaction records.

The vulnerability isn't just about the military or high-tech systems. It touches every part of modern infrastructure because GPS is so deeply integrated into almost everything.

Why Traditional Solutions Don't Work

You might think the military would have solved GPS jamming decades ago. They did, partially, for their own systems.

Military GPS receivers use encrypted signals that are much harder to jam or spoof. They also use much higher-power signals that are more resistant to interference. But civilians don't have access to military-grade GPS receivers because they're classified and expensive.

For civilian GPS, the signals are intentionally weak so that any civilian can receive them with cheap equipment. This is a fundamental design constraint. You can't make the civilian GPS signals stronger without completely rebuilding the satellite constellation, which would cost tens of billions of dollars.

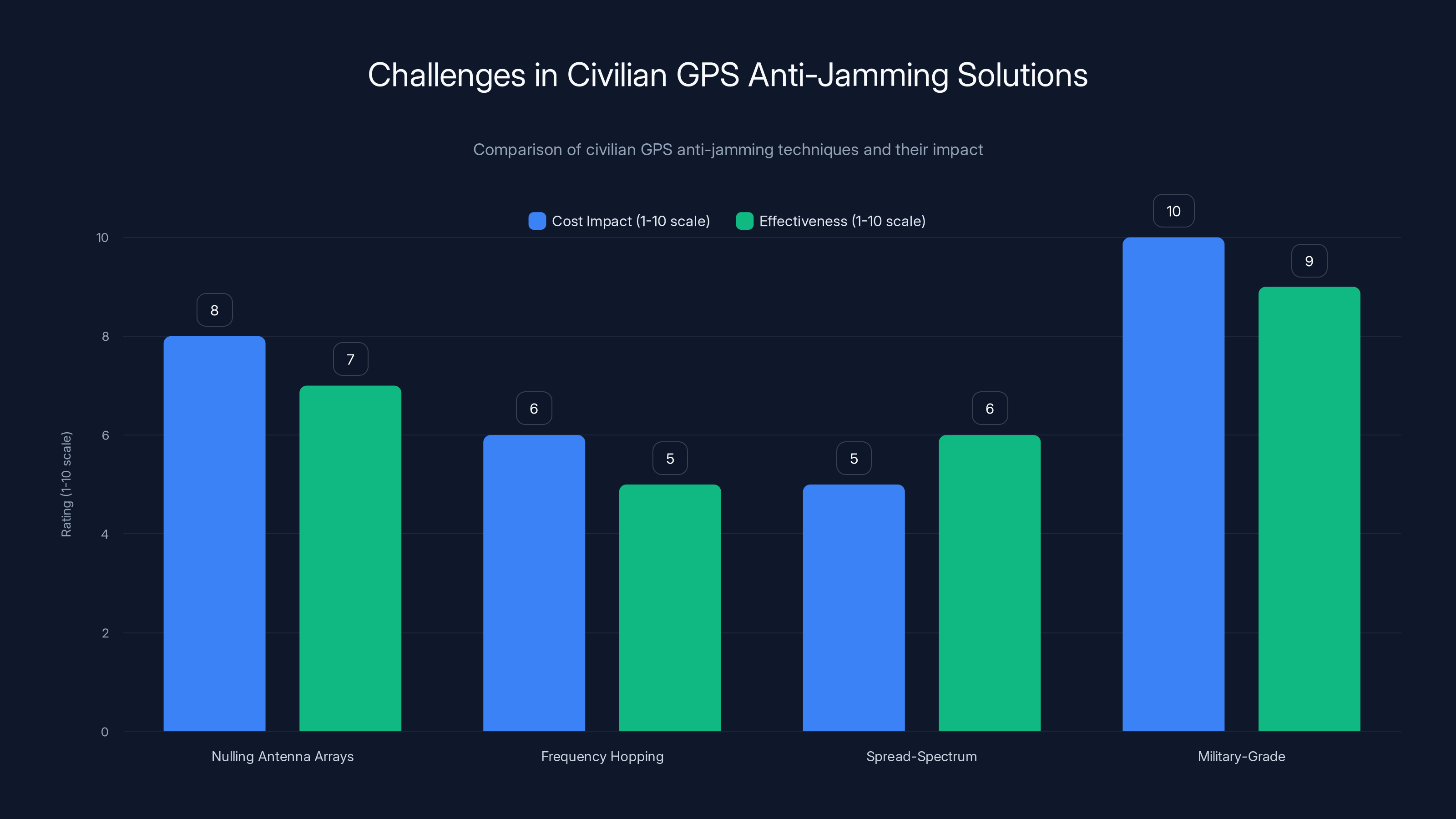

There are some anti-jamming techniques that exist today. GPS receivers can use multiple antennas to detect and null out jammer signals. They can use frequency-hopping techniques to avoid jammer frequencies. They can use spread-spectrum techniques to make the signals harder to jam.

But these techniques either increase receiver cost significantly or require changes to the GPS satellites themselves. You can build a military-grade GPS receiver with advanced anti-jamming for tens of thousands of dollars, but you can't build a consumer receiver with the same capability for $5.

The fundamental problem is that GPS, by design, prioritizes being cheap and easy to receive over being secure and resistant to jamming. Fixing that requires either:

- Accepting higher receiver costs for everyone

- Building redundant systems that don't depend on GPS

- Developing new satellite signals with better jamming resistance

- Some combination of all three

GPS jamming incidents have increased significantly since 2000, with notable spikes around 2016 due to location spoofing demand and post-2022 due to military activities. Estimated data.

The Modernization Effort: GPS III and Beyond

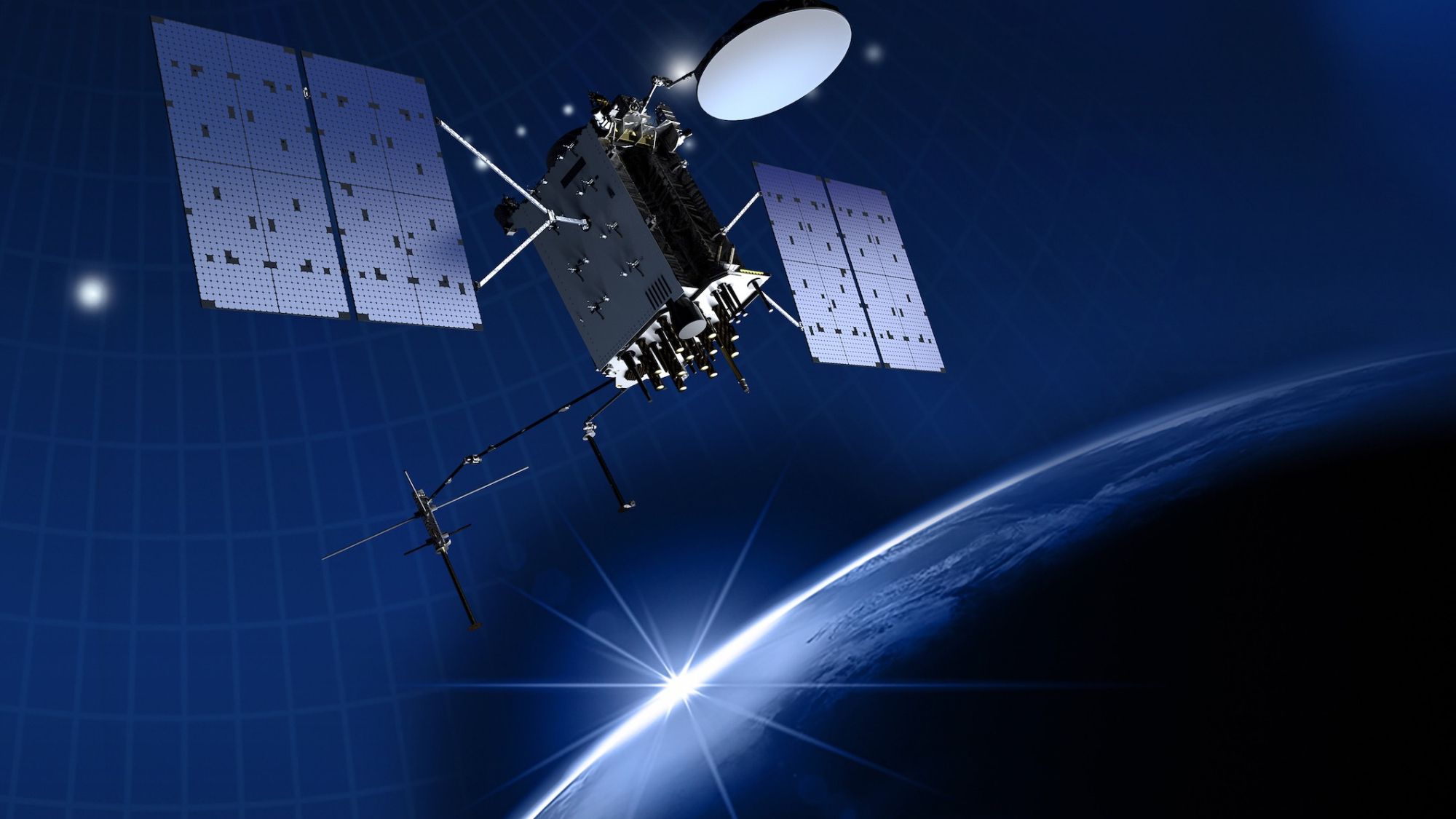

The U. S. military recognized GPS vulnerability decades ago. They've been building better solutions.

GPS III is the newest generation of satellites currently being deployed. GPS III satellites are significantly more powerful than their predecessors. They transmit stronger signals, making them harder to jam. They also broadcast new military-encrypted signal formats that are much more resistant to spoofing.

For civilian users, GPS III introduces new civilian signal formats. The L5 signal is a second civilian frequency that provides better accuracy and jamming resistance because it's on a different frequency than traditional GPS. The L1C signal is another new civilian signal with stronger power and better structure.

Having multiple signal frequencies is key. If a jammer targets one frequency, receivers can potentially lock onto another frequency. This redundancy makes jamming much harder.

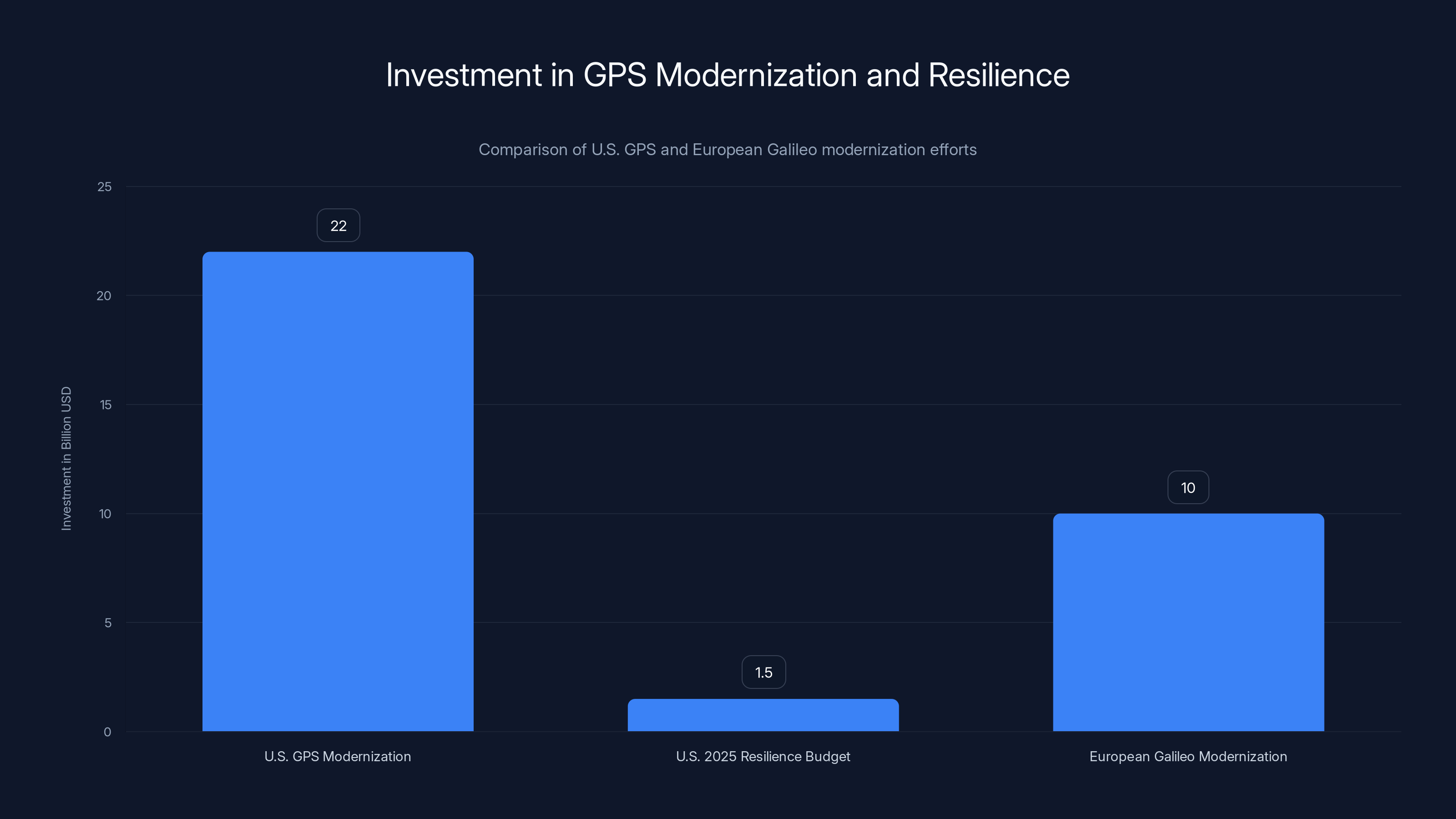

The U. S. government has invested over $22 billion in the GPS modernization program. This includes building new satellites, launching them, replacing aging satellites, and improving ground infrastructure.

Additionally, the military's 2025 budget requested $1.5 billion specifically for resilient position, navigation, and timing programs. This is money dedicated to making the system more robust against jamming and spoofing.

Europe is doing something similar with Galileo, their civilian satellite navigation system. Galileo satellites are also more powerful than GPS and offer signal formats specifically designed to be harder to jam.

But modernization takes time. GPS satellites launch as needed, and each launch is an expensive operation. The constellation won't be fully upgraded to GPS III for several more years.

Alternative Navigation Systems: The Backup Plan

The U. S. government is actively developing backup systems that don't depend on satellites.

The Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration are investing in e LORAN, an enhanced version of LORAN (Long Range Navigation), a much older navigation system that predates GPS.

e LORAN uses ground-based transmitters instead of satellites. The transmitters broadcast signals that are much stronger than GPS because they originate from the ground and don't have to travel through space. Because the signals are stronger, they're much harder to jam. A jammer would have to broadcast signals comparable in power to a radio station to effectively jam e LORAN, which is impractical in most situations.

The downside is that e LORAN is less accurate than GPS. GPS can provide meter-level accuracy in good conditions. e LORAN typically provides accuracy within tens of meters. For aviation and maritime navigation, this is acceptable. For precision farming or guided weapons, it's not.

But e LORAN is essentially a fail-safe. If GPS goes down, critical navigation-dependent systems can fall back to e LORAN for basic positioning information.

In October 2025, the Department of Transportation awarded $5 million to five different companies to develop and demonstrate e LORAN and other complementary navigation technologies. This is essentially a bet-hedging strategy: figure out what technologies work best for various applications and then scale them.

Other countries are exploring similar backup systems. The United Kingdom is testing a system called Locate from signals like e LORAN and other ground-based transmitters.

China and Russia are primarily relying on their own satellite systems (Bei Dou and GLONASS respectively) as redundancy. If one system goes down, the others are still available. But multiple satellite systems don't help much against military jamming that specifically targets all of them.

Estimated data shows that while military-grade solutions offer high effectiveness, they also come with the highest cost. Civilian techniques like nulling antenna arrays and spread-spectrum are moderately effective but still costly.

Inertial Navigation Systems: Going Old School

Another approach to GPS resilience is inertial navigation technology.

Inertial systems use accelerometers and gyroscopes to track movement without external signals. You know where you started, you measure acceleration and rotation, and you calculate where you are now.

This approach was used on submarines and intercontinental ballistic missiles long before GPS existed. It's incredibly accurate for short periods but suffers from drift over time. After several hours without external corrections, inertial systems accumulate enough error to become unreliable.

But combined with GPS, inertial systems are powerful. When GPS is available, it corrects the inertial system's drift. When GPS is jammed, the inertial system can maintain accuracy for hours, which is usually long enough to either reach a destination or reestablish GPS contact.

Militaries have used this hybrid approach for decades. Civilian applications are now exploring it.

The challenge is cost. A high-grade inertial measurement unit costs tens of thousands of dollars. The inertial systems suitable for civilian applications (smartphones, delivery vehicles) are much cheaper but less accurate.

For specialized applications like emergency response vehicles, military equipment, or critical infrastructure, hybrid GPS-inertial systems are becoming standard. These systems cost more but provide resilience against GPS jamming.

Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) GPS: The Precision Alternative

For applications requiring extreme precision, RTK-GPS is becoming more popular.

Real-Time Kinematic GPS uses a network of ground-based GPS reference stations instead of relying solely on satellite signals. A reference station receives GPS signals and calculates its exact position. It then broadcasts corrections to nearby receivers.

A receiver uses these corrections to achieve centimeter-level accuracy instead of the meter-level accuracy of standard GPS. It's particularly useful for agriculture, construction, and surveying.

Because RTK relies on ground-based transmitters rather than satellites, it's less vulnerable to jamming. A jammer would have to target the ground infrastructure, which is much harder to do effectively than jamming satellite signals.

The downside is that RTK requires a dense network of reference stations. The receiver has to be within signal range of these stations. For maritime or aviation applications covering vast areas, RTK isn't practical. For local applications like farming or construction, it works well.

Networks like CORS (Continuously Operating Reference Stations) provide RTK corrections across the United States. Similar networks exist in Europe, Asia, and other developed regions. As this infrastructure expands, RTK becomes more viable as a GPS complement.

The U.S. has invested over

Blockchain and Distributed Trust: The Future Approach

Some researchers are exploring completely different approaches to navigation and timing using distributed networks and blockchain.

The idea is to create a navigation system that relies on many independent transmitters rather than a centralized satellite constellation. If jamming takes out one transmitter, others are still available.

Blockchain technology could potentially be used to create a distributed, tamper-resistant system for validating timing and position information. Instead of trusting a central authority (the U. S. government operating GPS), users would verify information through a distributed network of independent verifiers.

This is still largely theoretical and experimental. Implementing a global navigation system using blockchain would require solving massive technical challenges: how to achieve synchronized timing across a distributed network, how to prevent 51% attacks where an adversary controls most of the network, how to achieve the accuracy and latency required for real-world applications.

But the research is ongoing, particularly in academia and among cryptocurrency communities that are already comfortable with blockchain technology.

If such a system could be built, it would be extremely resilient. Jamming or spoofing would require compromising the majority of the network simultaneously, which is much harder than jamming a single satellite constellation.

Military Solutions: The Classified Approach

The military has solutions for GPS jamming that civilians don't have access to, mostly because they're classified.

Military GPS receivers use the M-code signal, which is encrypted and only available to authorized military users. This signal is much stronger than civilian signals and uses encryption that makes spoofing essentially impossible without breaking the encryption.

The military also has the capability to deny GPS to enemies through jamming and spoofing. During military exercises and actual conflicts, the U. S. military jams and spoofs GPS to test and train its systems and personnel. Russia and China do the same.

But here's the problem: military solutions don't help civilians. A commercial airline can't switch to military GPS because those receivers are classified and not available commercially. A power grid operator can't switch to military timing signals for the same reason.

This creates an asymmetry. Militaries invest in resilient, hardened GPS systems. Civilians depend on vulnerable civilian GPS signals.

There's been discussion about making more powerful civilian military signals available or making civilian signals more resistant to jamming. But this requires updating the satellites, which is expensive and takes years.

In the meantime, the military has invested heavily in GPS-independent systems. The U. S. military's inertial guidance systems, terrain mapping systems, and other technologies can provide navigation and targeting capability even without GPS. But these are specialized systems not available to civilian users.

The Economics of GPS Resilience

Building resilient GPS alternatives costs money. Lots of money.

The GPS modernization program costs over $22 billion. Building and maintaining e LORAN backup systems costs hundreds of millions. RTK reference station networks cost millions to establish and maintain.

These are major investments for what is essentially insurance against GPS disruption. In normal times, this might seem like wasteful spending. But in an era of increasing geopolitical tension and frequent military exercises that disrupt GPS, the investment is clearly justified.

The question for policymakers is: who should pay for this? Civilian GPS users benefit from GPS redundancy. So do militaries. Should costs be shared? Should it be funded entirely by government? Should private companies that depend on GPS contribute?

Currently, the U. S. government bears most of the cost. The Federal Aviation Administration funds aviation-related GPS backup systems. The Department of Transportation funds general navigation system development. The Department of Defense funds military-specific systems.

But there's clearly a cost-benefit calculation being done. If GPS jamming incidents multiply and cause major infrastructure failures, the pressure to fund alternatives will increase dramatically.

For now, the investment is steady but not overwhelming. But if a major power grid failure or aviation accident is directly caused by GPS jamming, expect funding to increase rapidly.

Cyber Threats: GPS Goes Digital

GPS vulnerability isn't just a radio frequency problem anymore. It's increasingly a cybersecurity problem.

Modern GPS receivers contain computers and software. This software can be vulnerable to hacking, just like any other connected device. An attacker could potentially compromise a GPS receiver's firmware to make it ignore authentic signals or accept spoofed signals.

As GPS integration becomes more sophisticated, with receivers connected to larger systems through APIs and networks, the attack surface expands. A compromised GPS receiver in a power grid controller could provide false position or timing information that cascades through the power system.

Security researchers have demonstrated vulnerabilities in various GPS receivers and systems. These vulnerabilities are being patched, but the underlying risk remains.

The solution requires both hardware-level improvements (better receiver design, anti-spoofing hardware) and software-level improvements (secure firmware, authentication protocols, anomaly detection).

This is an ongoing arms race between defenders and potential attackers, similar to every other cybersecurity domain.

The Path Forward: What Comes Next

The GPS modernization effort will continue for the foreseeable future. GPS III satellites will eventually replace the entire constellation. New civilian signal formats will become standard. Ground infrastructure will improve.

Parallel investments in backup systems like e LORAN will continue, especially in countries that view GPS disruption as a credible threat.

Private companies will continue developing hybrid systems that combine GPS with inertial navigation, RTK, and other technologies to create resilient positioning systems.

The regulatory environment will likely become more stringent. Already, the FCC heavily penalizes GPS jamming. As incidents increase, expect more regulations restricting RF emissions and penalizing jamming more harshly.

International agreements regarding GPS jamming during peacetime may be negotiated, similar to existing agreements about other forms of warfare. But enforcement will be difficult, and military exercises will continue to cause civilian disruption.

For specific industries like aviation and power grids, mandatory backup navigation systems may become regulatory requirements. Airlines might be required to carry e LORAN receivers as backups. Power grids might be required to use GPS-independent timing systems for critical functions.

The overall trajectory is toward a multi-system approach where GPS remains primary but is complemented by multiple backup systems, creating defense in depth.

This approach is more expensive than relying on GPS alone, but it's increasingly seen as necessary as GPS jamming becomes more common and consequences of GPS failure become more serious.

FAQ

What is GPS jamming and how does it differ from spoofing?

GPS jamming involves broadcasting strong RF signals that overwhelm legitimate GPS signals, effectively disabling GPS reception in an area. Spoofing, by contrast, involves broadcasting fake GPS signals that look authentic but provide false position or timing information. Jamming is a denial-of-service attack; spoofing is a deception attack. Jamming is easier to detect because the receiver recognizes something is wrong. Spoofing is harder to detect because the receiver thinks everything is normal but is receiving false information.

Why is GPS so vulnerable to jamming if it was designed by the military?

GPS was designed in the 1970s for military use, but the U. S. government made the strategic decision to provide the same signals to civilians. The military anticipated this vulnerability and built military-only encrypted signals, but civilian signals had to remain open and unencrypted for everyone to access. This openness meant the signals had to be weak enough that cheap civilian receivers could receive them, which paradoxically made the civilian signals vulnerable to jamming. The military solved this for themselves with encrypted signals, but civilians were left with the vulnerable civilian GPS signals.

What are the main consequences if GPS stops working?

Losing GPS would disrupt aviation navigation, making low-visibility landings much riskier. Precision agriculture would become less efficient, costing farmers thousands of dollars per season. Power grids would lose timing synchronization, potentially causing cascading failures. Financial systems would lose accurate transaction timestamps. Emergency response systems would operate slower. Military operations would be severely degraded. Delivery and ride-sharing systems would fail. Essentially, GPS failure would impact nearly every sector of modern infrastructure because GPS is so deeply integrated into how systems operate.

How is the U. S. government trying to fix GPS vulnerability?

The government is pursuing multiple strategies: modernizing GPS satellites with the GPS III program, which provides stronger signals and new civilian signal formats; investing in backup systems like e LORAN that use ground-based transmitters instead of satellites; funding research into hybrid systems that combine GPS with inertial navigation and RTK; increasing funding for position, navigation, and timing resilience research; and potentially developing regulations that require critical infrastructure to have GPS-independent backup systems. The total investment exceeds $22 billion for satellite modernization alone, plus billions more for backup systems and resilience research.

What is e LORAN and why is it considered a viable GPS backup?

e LORAN (enhanced LORAN) is a modernized version of the Long Range Navigation system that existed before GPS. It uses ground-based transmitters instead of satellites to provide navigation signals. Because the signals originate from the ground, they're much stronger and harder to jam than satellite signals. A jammer would need to broadcast signals comparable to a radio station to effectively jam e LORAN. The downside is that e LORAN provides less accuracy than GPS, typically within tens of meters rather than the meter-level accuracy of GPS. But for aviation and maritime navigation, this accuracy is acceptable, making e LORAN a practical backup system for when GPS is unavailable.

Can civilians use military GPS signals to avoid jamming?

No. Military GPS signals use encryption and specialized hardware that is classified and not available to civilian consumers. Military receivers use the M-code signal and other encrypted formats specifically designed to resist jamming and spoofing. Commercial civilian receivers can only access the unencrypted civilian GPS signals. There has been discussion about making some military-level signals available to civilians, but this would require changes to satellites and receiving hardware that would take many years and billions of dollars to implement.

How does GPS modernization (GPS III) improve jamming resistance?

GPS III satellites are significantly more powerful than their predecessors, transmitting stronger signals that are harder to jam. They also broadcast new civilian signal formats like L5 and L1C on different frequencies than traditional GPS, providing redundancy so if one frequency is jammed, receivers can lock onto another. The military signals in GPS III use better encryption and frequency modulation techniques specifically designed to resist jamming and spoofing. The combination of multiple signals, stronger power, and better encryption makes the entire system much more resilient to jamming attacks than older GPS satellites.

What is RTK-GPS and when would you use it instead of regular GPS?

Real-Time Kinematic GPS uses a network of ground-based reference stations to provide centimeter-level positioning accuracy instead of the meter-level accuracy of standard GPS. It's particularly useful for precision agriculture, construction surveying, and other applications requiring high accuracy over limited areas. Because RTK relies on ground transmitters rather than satellites, it's less vulnerable to jamming. However, RTK requires being within range of reference station transmitters, so it's not suitable for maritime or aviation applications covering vast areas. For localized applications where a dense network of reference stations exists, RTK is increasingly preferred over standard GPS.

Is GPS jamming legal in the United States?

No. Using or selling GPS jamming equipment is a federal crime in the United States. The FCC actively prosecutes GPS jamming violations, with penalties up to $112,500 in fines and potential criminal charges. However, military and government agencies can legally jam GPS during exercises and operations. The legal situation varies internationally; some countries have similar strict prohibitions, while others have less enforcement. Some countries openly use GPS jamming during military exercises, which affects civilian systems in neighboring areas.

Why would someone jam GPS signals?

Militaries jam GPS during exercises and operations to train forces and degrade enemy capabilities. Criminal enterprises jam GPS to disrupt asset tracking and lose pursuers. Truck drivers and logistics companies use jamming or spoofing to hide their location or falsely claim cargo was delivered. During geopolitical conflicts or military tensions, militaries conduct GPS jamming to test their systems and deny GPS to potential adversaries. Hobbyists and researchers may experiment with jamming for academic purposes. The motivations range from military training to criminal activity to simple fraud and deception.

Conclusion: Preparing for a GPS-Free World

GPS has become so central to modern life that its vulnerability represents a genuine national security and infrastructure risk. The incidents in Norway are just the visible tip of a much larger problem.

The good news is that policymakers, military leaders, and technology experts recognize this vulnerability and are actively working on solutions. The GPS modernization effort is underway. Backup systems like e LORAN are being developed. Research into resilient navigation systems continues.

But solutions take time. Launching satellites takes years. Building infrastructure takes time. Deploying new systems across industries takes time.

In the meantime, GPS jamming will likely continue to increase. Military exercises will continue to disrupt civilian GPS. Criminal activities and fraud exploiting GPS vulnerabilities will expand.

The transition to a world with multiple redundant navigation systems instead of a single point of failure will be expensive and lengthy. But it's a necessary transition.

For individuals, the practical takeaway is simple: don't assume GPS always works. For critical applications, use backup navigation methods. For aviation, e LORAN and inertial systems already exist as backups. For critical infrastructure, implement monitoring and fallback procedures.

For policymakers, the message is also clear: invest in GPS resilience now, before a major GPS failure causes significant economic damage or loss of life.

The satellite system that transformed modern navigation and infrastructure has been hugely successful. But its success has created a vulnerability. We now depend on it too much. The fix involves diversification, redundancy, and investment in backup systems.

GPS won't disappear. It will continue to be the primary navigation system for most users. But it will eventually be complemented by multiple backup systems, creating a resilient infrastructure that works even when GPS fails.

That transition is underway now, and it's necessary work, even if most people don't realize it yet.

Key Takeaways

- GPS jamming has increased over 10x since 2010, with incidents accelerating dramatically since military conflicts in 2022

- The U.S. government is investing over $24 billion in GPS modernization (GPS III satellites) and backup systems like eLORAN to address vulnerability

- GPS is integrated into power grids, financial systems, aviation, agriculture, and military operations, making disruption impact far beyond navigation

- Solutions include stronger satellite signals, multiple frequency options, ground-based backups like eLORAN, hybrid inertial systems, and RTK ground corrections

- Military solutions like encrypted M-code signals exist but aren't available to civilians, leaving civilian infrastructure dependent on vulnerable civilian GPS signals

Related Articles

- France's La Poste DDoS Attack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Business [2025]

- The Worst Hacks of 2025: A Cybersecurity Wake-Up Call [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness: Why AI Safety Matters Now [2025]

- The Complete Guide to Breaking Free From Big Tech in 2026

- Beyond WireGuard: The Next Generation VPN Protocols [2025]

- 9 Game-Changing Cybersecurity Startups to Watch in 2025

![GPS Jamming: The Vulnerability Threatening Modern Infrastructure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/gps-jamming-the-vulnerability-threatening-modern-infrastruct/image-1-1767022577315.jpg)