The Hidden Cost of Gas Generators on Food Carts

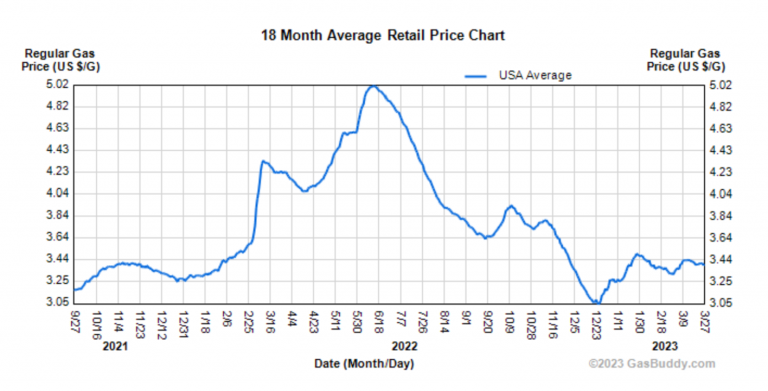

Walk down any major street in New York City and you'll catch them before you see them: the acrid smell of diesel fumes wafting from food carts. These generators, humming away at volumes that can hit 80 decibels, power everything from warming lights to refrigeration units. They're reliable, sure. But they're also expensive, loud, and frankly, they're killing the appeal of street food.

Here's the economic reality most people don't think about. A typical food cart generator costs between

The pollution angle matters too, and it's not just environmental virtue signaling. New York City officially began tracking roadway pollution in street vending zones, and generators consistently rank among the worst offenders. A single cart running a 2-kilowatt generator produces roughly 2.5 kilograms of carbon emissions annually. When you multiply that across the city's estimated 10,000+ street food carts, you're looking at 25,000 kilograms of annual emissions from this single industry segment.

But the real problem isn't the generators themselves. The real problem is that for decades, nobody invested in building the infrastructure for a better alternative. Until now.

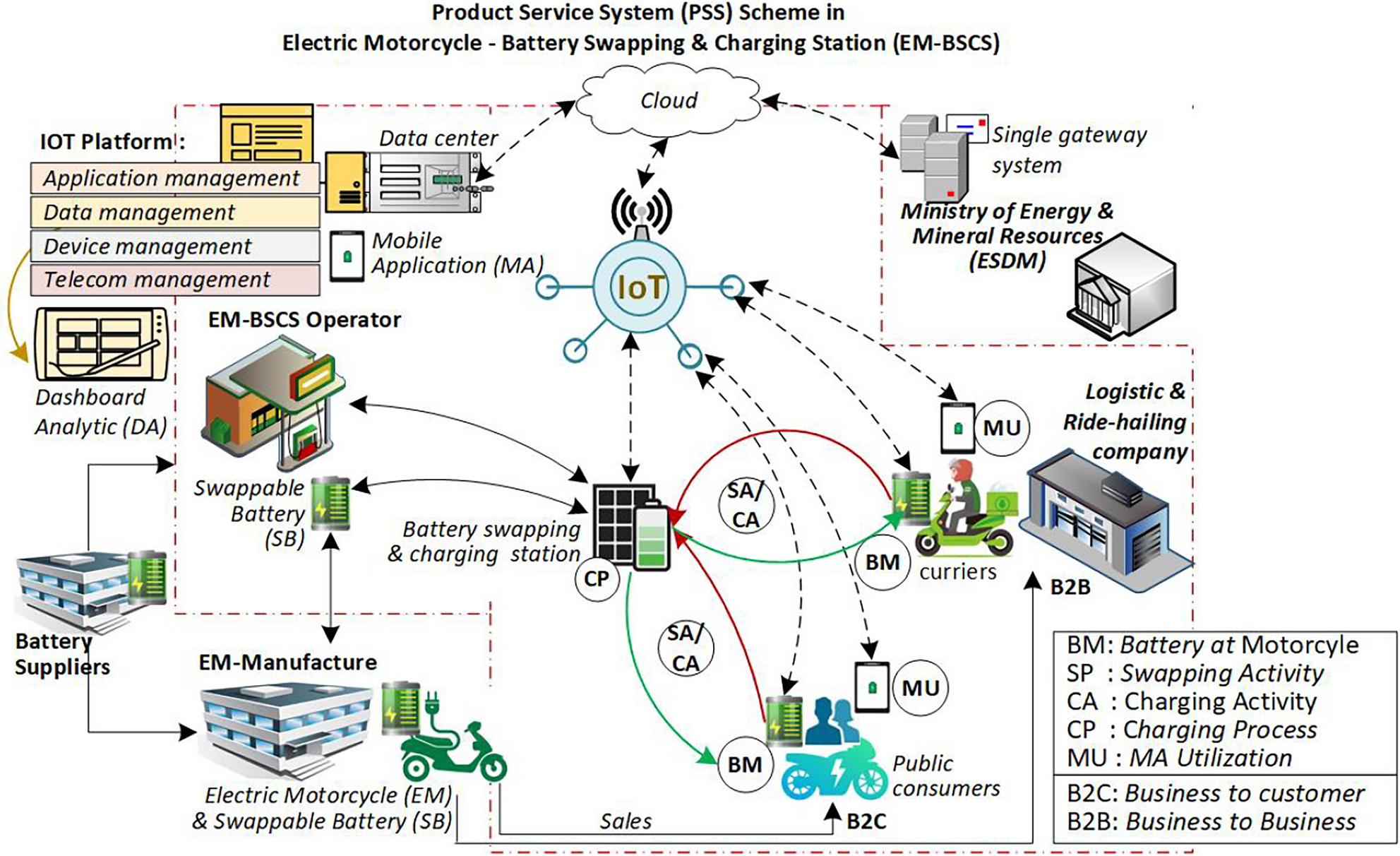

Understanding Pop Wheels' Battery Swapping Network

Pop Wheels started with a different problem entirely. Back in 2023, New York City experienced a surge in e-bike fires that caught everyone's attention. These weren't freak accidents. They were lithium battery incidents in shared housing, garages, and sidewalk enclosures. In a single year, the city recorded over 200 e-bike fire incidents. The company's founding mission was laser-focused: create fire-safe infrastructure for battery storage and charging.

David Hammer, Pop Wheels' co-founder and CEO, came from Google in the early days. That background shapes how the company thinks about infrastructure problems. Instead of just building safer charging stations, they asked: what if we could create a network that solves the distribution problem entirely?

The answer was battery swapping. Rather than making riders wait 3-4 hours for a full charge, Pop Wheels designed a system where delivery workers and e-bike riders could swap depleted batteries for fully charged ones in under two minutes. The math works because you don't need one charger per rider. You need enough batteries to cover the population of riders during peak hours, plus a few charging stations running overnight.

Currently, Pop Wheels operates 30 charging cabinets throughout Manhattan, primarily concentrated in areas with high delivery worker density. Each cabinet holds 16 batteries and draws approximately 3.8 kilowatts during the charging cycle, equivalent to what a Level 2 electric vehicle charger requires. The company designed these cabinets with integrated fire suppression systems, an engineering choice that stems directly from their origin story.

The unit economics tell an interesting story. A delivery worker using traditional charging (through bodegas that charge

What's truly clever about Pop Wheels' approach is that they've created what Hammer calls a "de facto decentralized fleet." Because most e-bike riders use standardized models (primarily Arrow and Whizz), the company can standardize on a handful of battery types. This means they're not managing thousands of proprietary battery formats. They're managing maybe five different SKUs across hundreds of users. That's the infrastructure efficiency that makes the entire model work.

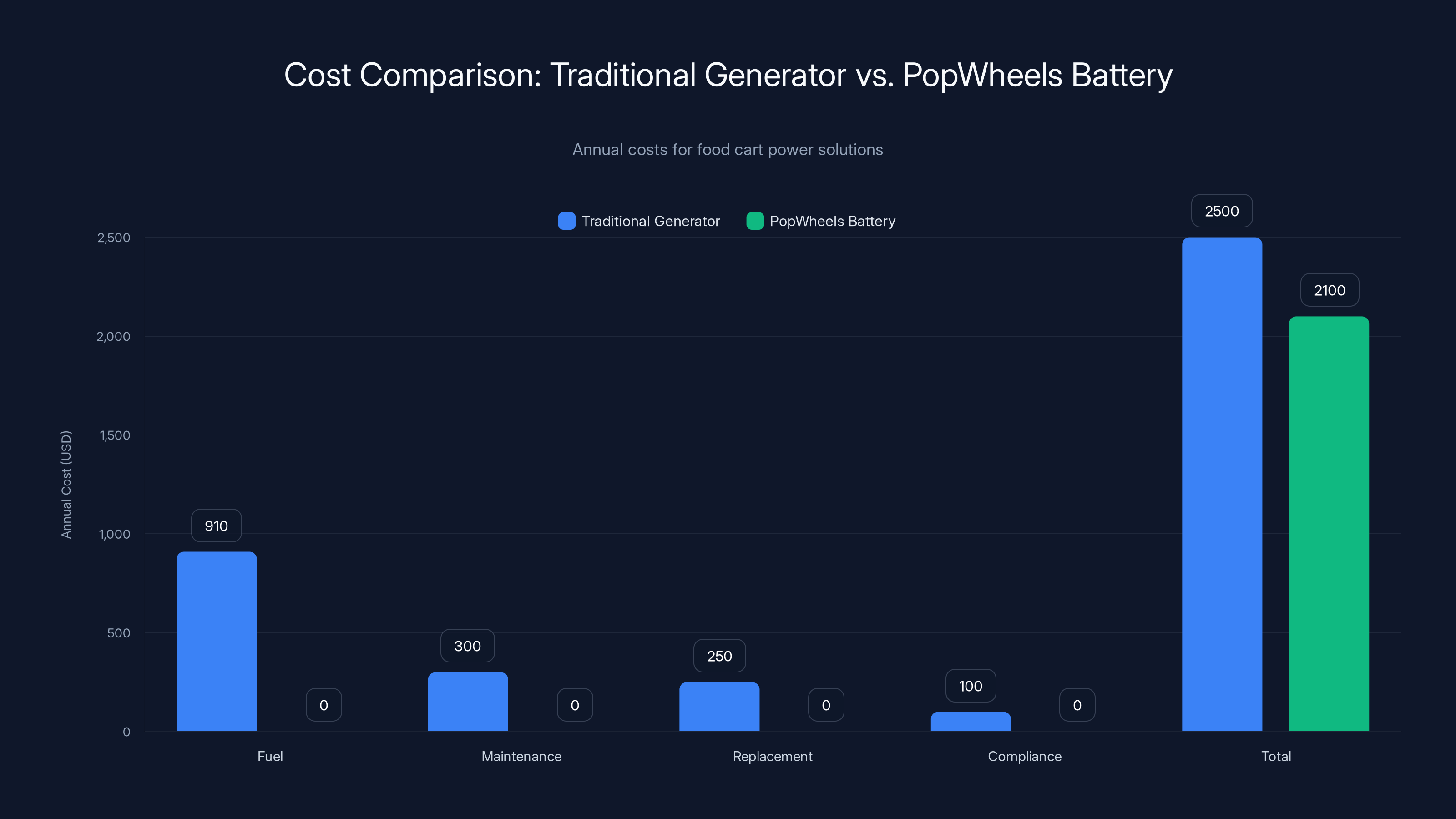

PopWheels Battery swapping system offers a competitive annual cost of

The Food Cart Use Case: From Idea to Reality

Like many good business pivots, this one started with someone mentioning an article. A Pop Wheels team member sent Hammer a piece discussing New York City's initiative to decarbonize the street vending industry. The city was actively looking for solutions to reduce emissions from food carts, which represented a surprisingly significant urban pollution source.

Hammer and the team started running the numbers. A food cart's daily power requirements are actually quite predictable. Most carts need about 1.5 to 2.5 kilowatts of continuous power during operating hours, with peak demand during lunch and dinner service. A typical e-bike battery pack contains 0.5 to 0.7 kilowatts of capacity. That means a food cart would need three to five battery swaps during a 12-hour operating day.

The breakthrough realization: Pop Wheels' existing infrastructure could handle this. Their charging cabinets have excess capacity during off-peak hours. Their established relationships with property owners (mostly parking lot and alley space) gave them locations. And their battery inventory—already optimized for scale—could absorb food cart demand without major new capital investment.

In summer 2025, Pop Wheels built an adapter system and tested it at an event during New York Climate Week at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The prototype worked, but more importantly, it proved the concept could actually function under real conditions. Then came the real test: La Chona Mexican, a well-established food cart operating from the corner of 30th and Broadway in Manhattan.

The first full day of operation happened just last week. The results surprised even the Pop Wheels team. La Chona's owner reported dramatically improved customer experience. There was no smell. No noise. No visible emissions. Customers who had always rushed past due to generator fumes actually lingered. Food appeared fresher when the ambient temperature wasn't being warmed by an idling engine.

But here's what really caught Hammer's attention: multiple other cart owners came up asking what was happening and how they could get access. That organic demand signal matters more than any market research. It suggests real, unforced demand for this solution.

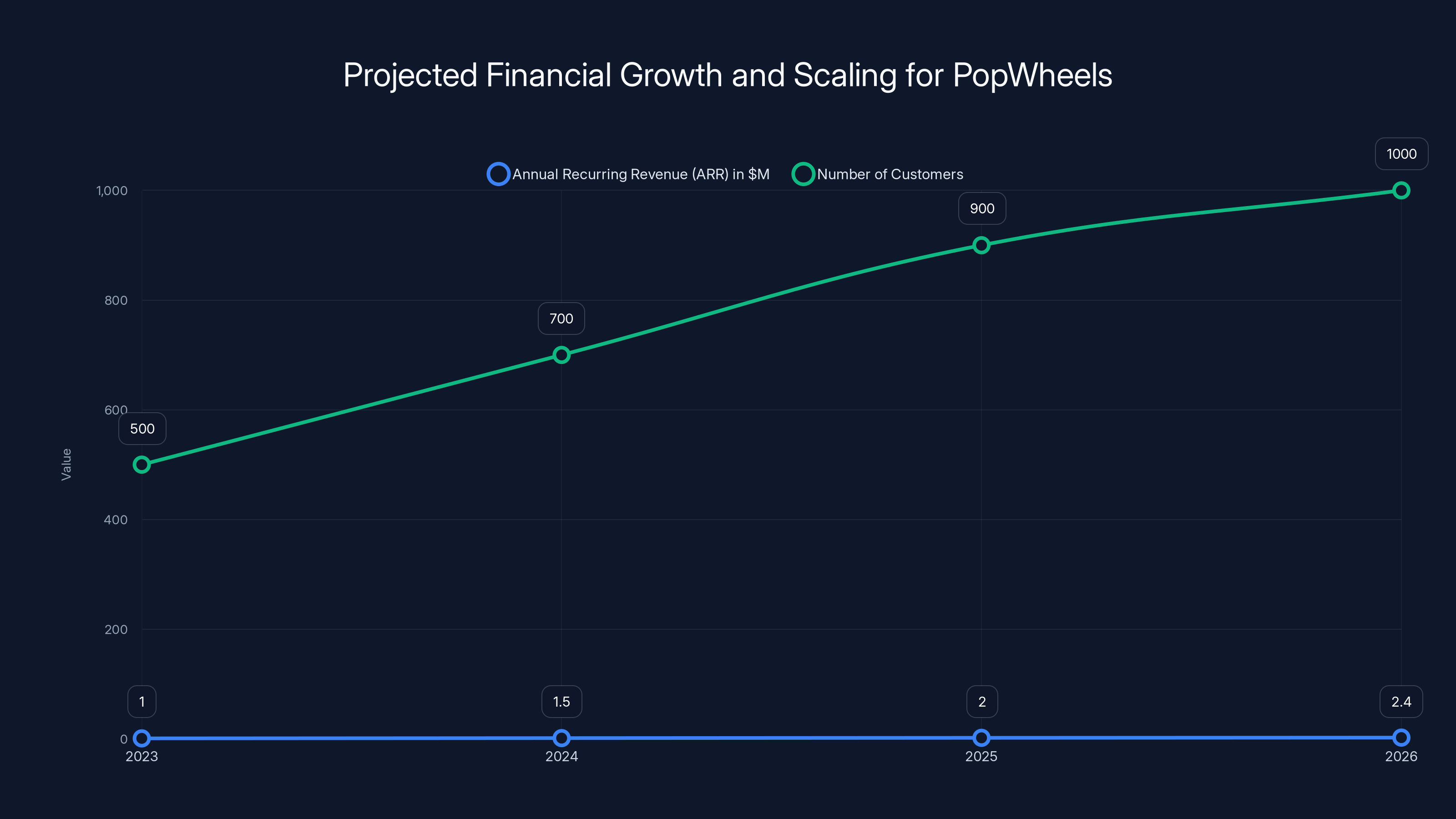

PopWheels aims to increase its ARR from

The Economics Work: Cost Comparison

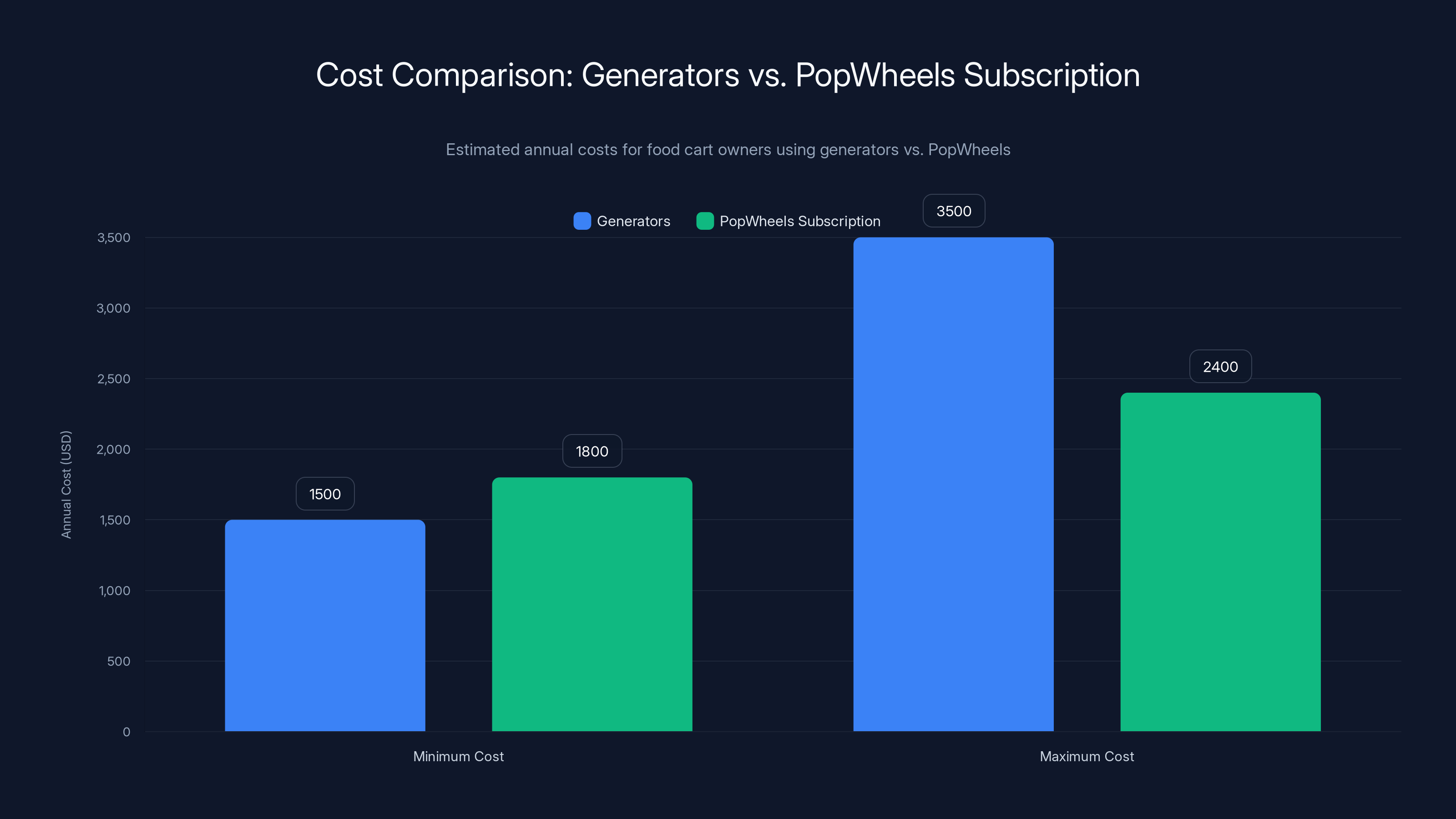

Let's break down the actual economics because this matters. A food cart owner currently spending $4,500 per year on generator fuel and maintenance faces several questions:

Scenario 1: Traditional Generator

- Fuel cost (assuming 910/year

- Maintenance and oil: $300/year

- Generator replacement (amortized over 8 years): $250/year

- Regulatory compliance and inspection: $100/year

- Total: $1,560/year (conservative estimate)

Actually, most cart owners report higher numbers closer to $2,500-3,500/year when accounting for unexpected repairs and additional inspections.

Scenario 2: Pop Wheels Battery Swapping

- Monthly subscription for food carts (estimated at 1,800-2,400/year

- Installation of adapter system: $0 (Pop Wheels handles this)

- Maintenance on cart: $0 (Pop Wheels manages batteries)

- Regulatory compliance: $0 (cleaner emissions)

- Total: $1,800-2,400/year

The economics work, but they're tight. Pop Wheels needs volume to make this work at scale. The company is betting that the regulatory angle will drive adoption. The EPA and New York City are both moving toward stricter emissions standards for street vending. The low-hanging fruit is generators. If regulators decide that generators on city streets violate emissions standards, food cart owners won't have much choice but to find alternatives.

There's also a quality-of-life angle that translates into economic value. A cart owner whose location attracts customers without the generator smell and noise might see higher foot traffic. Even a 10-15% increase in daily sales ($50-100 additional revenue) would make the Pop Wheels subscription profitable immediately.

Hammer mentioned that Pop Wheels can "make the economics work so that we're actually saving them money right off the bat." That suggests they're pricing the food cart subscription aggressively, potentially below the $150-200 estimated rate, knowing that volume and positive regulatory signals will eventually make the unit economics stronger.

Technical Architecture: How Battery Swapping Infrastructure Works

The unglamorous engineering work is where Pop Wheels differentiates. Building a battery swapping network sounds simple until you start thinking through the actual requirements.

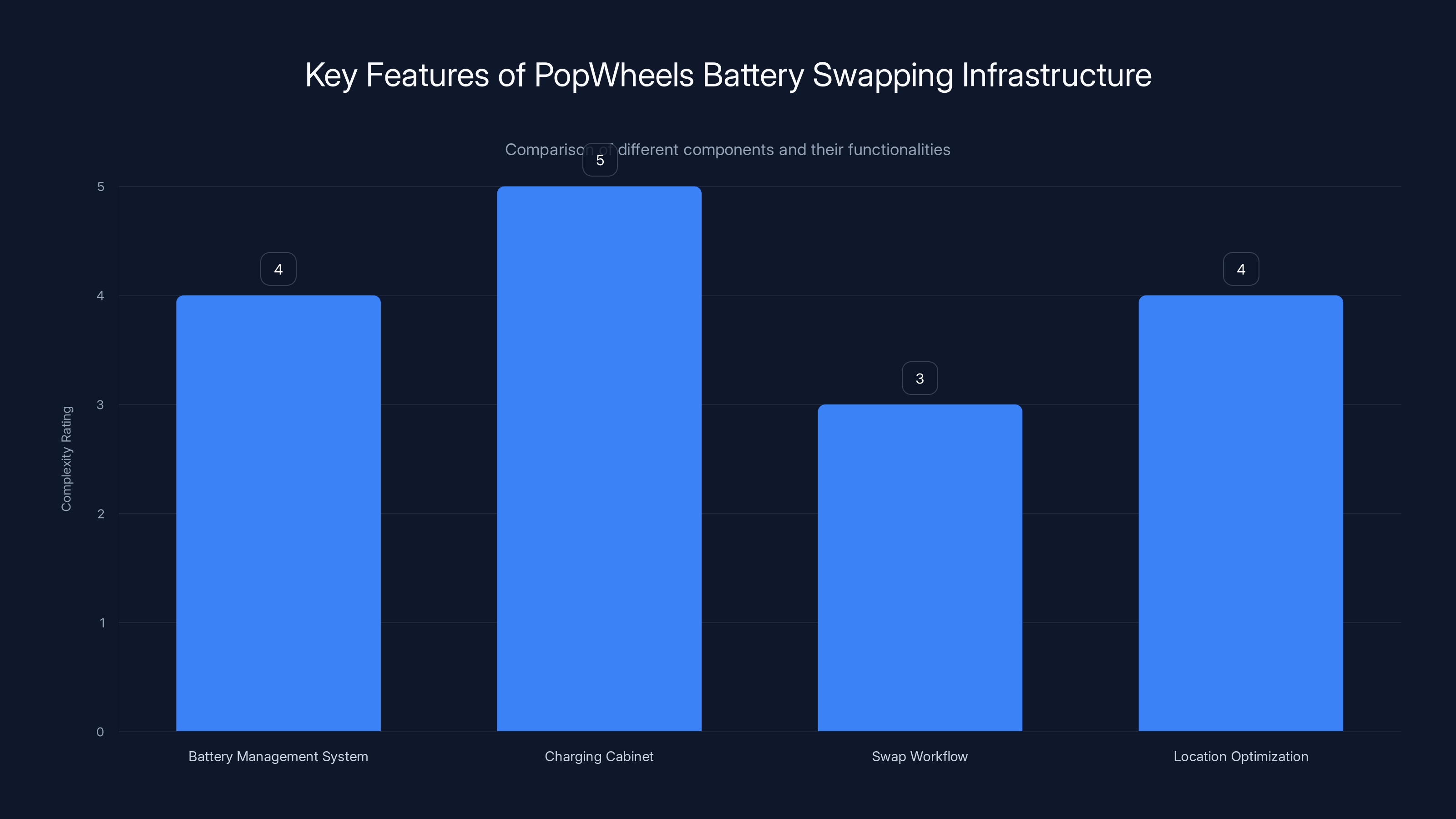

Battery Management System (BMS) Each Pop Wheels battery pack contains embedded monitoring hardware that communicates with the network. The system tracks:

- State of charge (SOC) in real-time

- Temperature during charging and use

- Cycle count and degradation estimates

- Safety parameters (voltage, current)

This data feeds into a predictive algorithm that estimates remaining useful life for each battery. When a battery degrades below 80% of original capacity, it gets rotated out of the main fleet into lower-demand applications (food carts, actually, would be perfect for these older batteries that still have 80% capacity).

Charging Cabinet Hardware Pop Wheels' 16-slot cabinets aren't just dumb storage boxes. They integrate:

- Individual outlet monitoring (detecting fire risk)

- Thermal management (fans and ventilation)

- Integrated fire suppression (their original founding mission)

- Network connectivity (communicating cabinet status, inventory levels)

Each cabinet requires 30-50 amps of electrical service, achievable from standard commercial circuits. Installation costs run between $8,000-15,000 per cabinet, which Pop Wheels amortizes across the user base.

The Swap Workflow The actual user experience is deliberately simple:

- Rider/cart owner approaches cabinet with depleted battery

- Mobile app confirms subscription status and available batteries

- Depleted battery inserted into cabinet slot (triggered door unlocks)

- Charged battery removed and installed

- Network updated automatically

The entire process takes 90 seconds for someone familiar with the system, 2-3 minutes for someone doing it the first time.

Location Optimization Pop Wheels uses predictive algorithms to determine cabinet placement. They model:

- Delivery worker density by neighborhood

- Typical routes and stop patterns

- Historical demand by time of day

- Nearby parking availability

- Commercial partner interest

The 30 existing cabinets serve roughly 2,000-3,000 active users with a utilization rate of approximately 15-20 swaps per cabinet per day. That's a total of 450-600 swaps daily across the network, representing meaningful scale for a startup at this stage.

The charging cabinet hardware is the most complex component, rated highest due to its integration of multiple safety and connectivity features. Estimated data.

Addressing the Regulatory Environment

Pop Wheels' timing with the food cart pivot is interesting from a regulatory standpoint. New York City has been unusually aggressive in trying to reduce street-level emissions. In 2023, the city introduced emissions standards for certain commercial vehicles, with discussions ongoing about extending these standards to street vending equipment.

The Street Vendor Project, a nonprofit advocacy organization, has been instrumental in helping Pop Wheels navigate this regulatory landscape. They've been advocating for exactly this kind of solution: decentralized, accessible, and genuinely beneficial for the vendors themselves.

From a regulatory perspective, the appeal is straightforward. A battery-powered food cart produces zero direct emissions. It's approximately 60% more efficient than a generator (batteries convert stored energy at 90%+ efficiency, while generators operate at 35-40% thermal efficiency). And it eliminates noise pollution, which is measurable and regulated in New York City.

There's a non-trivial chance that future regulations could make generators functionally illegal in commercial zones. If that happens, solutions like Pop Wheels move from "nice to have" to "required." Pop Wheels is clearly betting on this regulatory direction, which is why they're planning an "aggressive rollout" starting summer 2026.

The Broader Urban Infrastructure Play

What Hammer said about Pop Wheels' underlying thesis is worth taking seriously. The company isn't really in the food cart business. They're in the business of building urban-scale battery infrastructure. Food carts are just the next obvious use case.

If you think about the physical infrastructure needs of a modern city, battery charging is becoming increasingly central. The shift from gas vehicles to electric vehicles is creating massive demand for distributed charging. But batteries power way more than just cars and bikes. They power:

- Portable power tools for construction sites

- Emergency backup systems for critical equipment

- Temporary event lighting and sound systems

- Mobile food preparation and cooling

- Portable healthcare equipment

Every single one of these use cases currently relies on either gasoline generators or hardwired electrical service. Every single one could benefit from a standardized, distributed, managed battery network.

Pop Wheels' insight is that if you build the infrastructure correctly, you can support multiple use cases simultaneously. The same cabinet that serves a delivery worker at 6 AM can serve a food cart owner at noon and a contractor at 3 PM. The business model changes from "we're a delivery tech company" to "we're essential urban infrastructure."

This is why the food cart pivot matters beyond the immediate revenue. It proves the thesis. It shows that Pop Wheels can serve heterogeneous customers with different needs using the same core infrastructure. It demonstrates that the unit economics work across multiple business models.

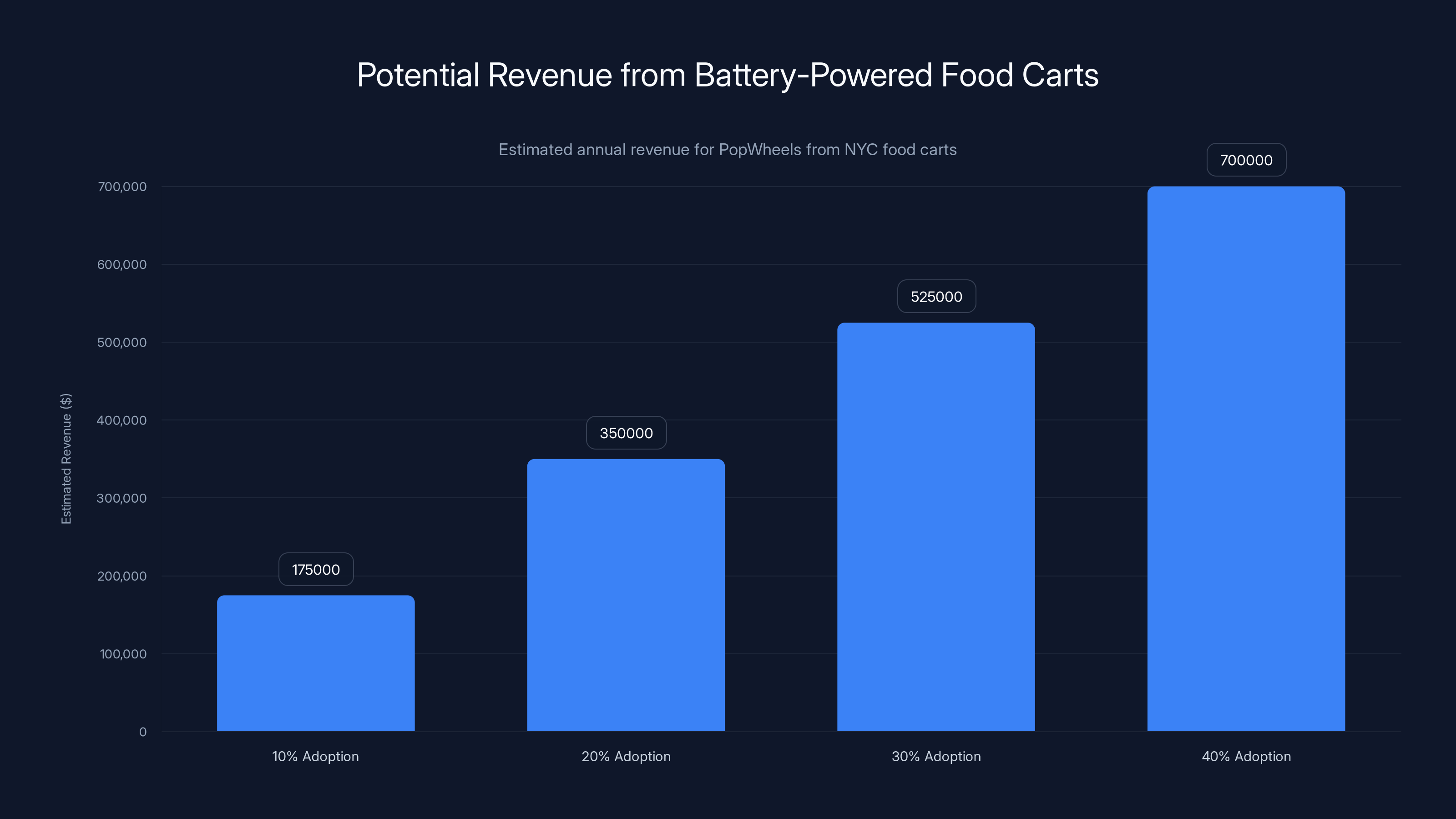

If 10% of NYC's food carts adopt battery power, PopWheels could generate

The Competitive Landscape and Why Pop Wheels Wins

Battery swapping for urban mobility isn't a new idea. Companies like Nio in China and CATL in Asia have already built massive battery swapping networks. In the U. S., there have been multiple attempts at scale, none particularly successful so far.

Why is Pop Wheels different? Several factors:

First-Mover in a Specific Segment Pop Wheels isn't trying to be everything to everyone. They're not trying to serve electric car owners (too capital-intensive, wrong physics). They're focused on electric bikes and adjacent uses where the battery requirements are much smaller. This focus means faster iteration and better unit economics.

Inherited Infrastructure from a Real Problem Pop Wheels started solving e-bike fires. That gave them legitimate reasons to build cabinets, develop safety systems, and establish partnerships with property owners. When they later decided to expand use cases, the infrastructure was already there. They didn't have to justify building cabinets for speculative reasons.

Regulatory Tailwinds New York City is genuinely pushing decarbonization. The Street Vendor Project is advocating for solutions. Multiple city agencies are interested in the problem. Pop Wheels has tailwinds that previous battery-swapping startups lacked.

Focus on Unit Economics Early Pop Wheels raised only $2.3 million in seed funding. That's small compared to some scale-up battery companies. But it forces discipline. They can't burn money on theoretical expansion. Every use case has to work economically at reasonable volumes.

The Summer 2026 Rollout: What to Expect

Pop Wheels is planning to expand aggressively starting this summer. Hammer mentioned this isn't vague aspiration. The company has specific targets and locations lined up. Here's what an aggressive rollout likely means:

Geographic Expansion Moving beyond Manhattan's core to outer boroughs. Queens and Brooklyn have significant street vending populations and parking lot availability. The company will probably add 20-30 new cabinets, bringing the total from 30 to 50-60.

Use Case Expansion Food carts are just the first vertical. Expect to see pilots with:

- Mobile car wash services (requiring water pump power)

- Portable medical stations (for events, pop-ups)

- Food delivery hubs (creating backup power for warehouses)

- Construction sites (small tools and temporary lighting)

Partnership Development Pop Wheels will likely sign formal partnerships with property owners, potentially offering revenue sharing or free charging access in exchange for cabinet placement.

Regulatory Engagement The company will probably work more closely with the city, potentially getting formal emissions reduction credit or regulatory compliance support.

Pricing Strategy For the food cart segment specifically, expect some form of promotional pricing in the first 6-12 months. Pop Wheels wants to demonstrate success stories. Subsidized pricing for early adopters makes sense from a unit-economics perspective (land grab now, raise prices later).

Switching from generators to PopWheels can save food cart owners money, with potential annual savings of up to $1,100. Estimated data based on typical expenses.

Critical Implementation Challenges

For all the promise, Pop Wheels faces real obstacles:

Availability and Reliability If a food cart owner depends on Pop Wheels batteries and a cabinet is empty or broken, they have no backup. This is a significant operational risk. The company needs redundancy and customer service processes that actually solve problems, not just promise solutions.

Weather and Seasonal Variation Battery performance degrades in cold weather. A battery rated for 0.7k Wh at 70 degrees might deliver only 0.55k Wh at 35 degrees. Winter in New York is real. Pop Wheels needs to account for seasonal capacity reductions and communicate honestly with customers.

Customer Education Food cart owners are not tech workers. Onboarding them onto an entirely new power system requires training, documentation, and ongoing support. Pop Wheels' customer success organization will be crucial.

Regulatory Uncertainty While tailwinds exist, they're not guaranteed. If regulations don't move as quickly as expected, food cart owners have less incentive to switch. Pop Wheels' aggressive rollout is betting on regulatory momentum that might not materialize on their timeline.

Competition from Grid Modernization Long-term, the city might invest in distributed electrical access points for street vendors. If that happens, it would undercut Pop Wheels' battery swapping model entirely. This is a longer-term risk but worth acknowledging.

What This Means for Urban Infrastructure Strategy

Pop Wheels' food cart pivot represents something broader: the realization that urban infrastructure can be modular, decentralized, and privately operated. Cities have traditionally assumed that powering street commerce was either a regulatory problem (license the generator use) or impossible (require grid connection). Neither works well.

Battery swapping sidesteps both problems. It's decentralized, so you don't need massive investment in electrical infrastructure. It's managed by a single operator, so reliability improves. It's private, so the city doesn't bear the maintenance burden.

The question this raises for city planners and policymakers is: what else could work on a battery swapping model? Could construction sites use it? Could emergency response teams use standardized batteries for backup power? Could event organizers use it for temporary installations?

The answer to all these questions is probably yes. Pop Wheels might not capture all these opportunities, but they're proving that the infrastructure works. That's valuable, even if competitors eventually emerge.

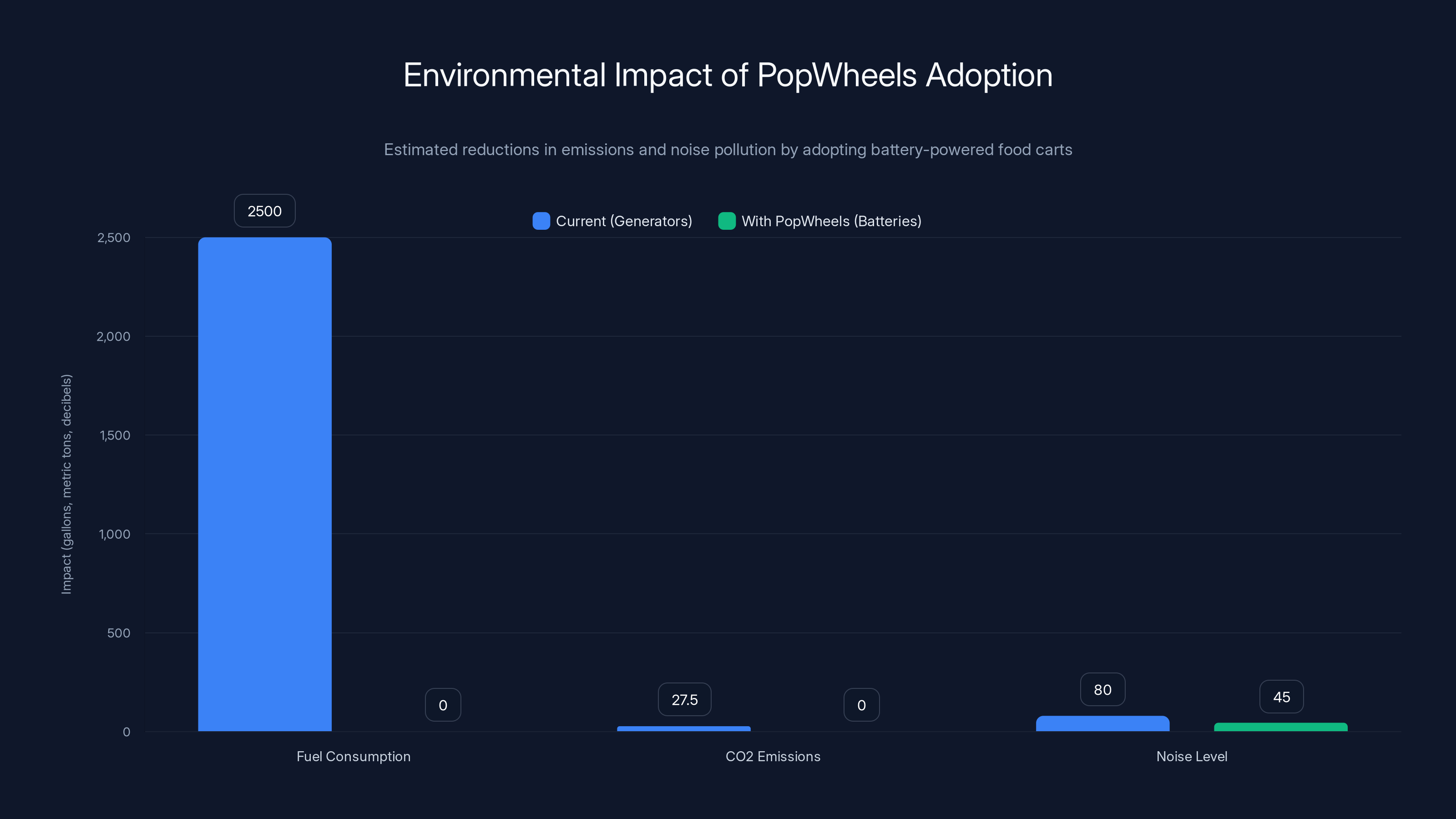

Adopting battery-powered carts could eliminate 2,500 gallons of fuel use and 27.5 metric tons of CO2 annually, while reducing noise pollution by 35 decibels. Estimated data based on current generator usage.

The Environmental Impact Story

Let's quantify what successful adoption actually means. If Pop Wheels gets 500 food carts (approximately 5% of New York's estimated 10,000 street food carts) onto their platform within the next two years:

Emissions Reduction

- Annual fuel consumption eliminated: roughly 2,500 gallons (based on 5 gallons/week per cart)

- Annual CO2 reduction: approximately 27.5 metric tons

- Equivalent to: removing 6 cars from the road for a year

That sounds modest until you realize this is just food carts. Scale it to construction tools, event equipment, and emergency systems, and suddenly you're talking about meaningful urban emissions reduction.

Particulate Matter and Air Quality Generators produce not just CO2 but also particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds. These affect respiratory health directly. The air quality improvement in neighborhoods where generators are replaced with batteries would be measurable, particularly in lower-income neighborhoods where street vending is concentrated.

Noise Pollution This is quantifiable but often ignored. Generator noise around 80 decibels creates stress, affects sleep, and impairs communication. Battery-powered carts operating at roughly 40-50 decibels represent a genuinely meaningful quality-of-life improvement.

The environmental story isn't just marketing. It's genuine, measurable impact that benefits real people.

Financial Viability: When Does Pop Wheels Achieve Scale?

The company has raised $2.3 million to date. That funds:

- Current 30-cabinet network

- Team of approximately 15-20 people

- R&D for new battery types and adapters

- Regulatory and legal work

- 12-24 months of operations

For the aggressive 2026 rollout to work, Pop Wheels will likely need additional funding. Not necessarily a massive Series A, but probably $5-10 million to:

- Build 30-50 additional cabinets

- Hire customer success and operations staff

- Create marketing and partnership development capacity

- Build the management software for food carts

At 500 customers paying

The path to sustainability probably involves:

- Hit 1,000+ customers (mix of delivery riders and food carts) generating $1.8-2.4M ARR

- Achieve 40%+ gross margins through operational efficiency

- Demonstrate unit economics that support 50%+ Y/Y growth

- Use that growth to raise Series B and expand to other cities

This is a realistic timeline if regulatory momentum continues and customer acquisition costs remain reasonable.

Lessons for Other Infrastructure Startups

Pop Wheels' approach offers insights for other infrastructure-focused startups:

Solve a Real Problem First Pop Wheels didn't start with the thesis "let's build battery swapping." They started with "let's prevent e-bike fires." That reality grounded them. When they eventually did develop battery swapping, it was solving a real customer problem, not a theoretical one.

Look for Natural Use Case Expansion Instead of forcing food carts into a platform designed for delivery riders, Pop Wheels recognized organic overlaps and built adapters. This is much more likely to work than forcing unrelated use cases together.

Align with Regulatory Trends Pop Wheels benefited massively from New York City's decarbonization push. They're not fighting regulation. They're enabling it. That's much easier than fighting against regulatory headwinds.

Keep Capital Efficiency in Mind Raising only

Focus on Operational Excellence The competitive moat won't be technology. It will be operations. Can Pop Wheels keep cabinets stocked? Can they respond when something breaks? Can they keep reliability above 95%? That's where the company succeeds or fails.

What Happens Next: The 18-Month Forecast

Based on Hammer's comments and market signals, here's what probably happens:

Summer 2026 (Now)

- 50-70 total cabinets across Manhattan and outer boroughs

- 3,000-5,000 total active users (delivery riders and early food cart adopters)

- First profitability at unit level, not yet at company level

- Series A funding discussions underway

Fall 2026

- 100+ cabinets

- 250-500 food carts on the platform

- Regulatory approval or formal pilot program with NYC government

- Expansion planning to other cities (likely Philadelphia, Washington DC, San Francisco)

Early 2027

- Series A funding announced (likely $5-10 million range)

- Presence in 2-3 additional cities

- 1,000+ total customers

- Profitability at unit level, approaching breakeven at company level

This is moderately aggressive but realistic given the tailwinds and current traction.

The Broader Implications for Sustainable Urban Commerce

What's genuinely interesting about Pop Wheels' food cart pivot is what it signals about the future of urban commerce more broadly. Food carts represent a genuinely sustainable form of commerce. They require minimal real estate, no construction, and can be deployed nearly anywhere.

The barrier to sustainability has always been the power system. Generators suck, but alternatives didn't exist. Battery swapping changes that equation. It makes sustainable street commerce not just possible but economically viable.

If this works at scale in New York, it becomes replicable everywhere. Dense urban areas worldwide have the same generator problem. Many have the same regulatory push toward decarbonization. The infrastructure Pop Wheels is building in Manhattan could be adapted to London, Singapore, Toronto, or Mexico City.

That's the real value proposition. Not just selling batteries to food carts in New York, but proving that distributed battery infrastructure works as a foundational urban utility. Everything else follows from that.

Conclusion: Why This Moment Matters

Pop Wheels' story is interesting because it represents infrastructure thinking catching up to the actual needs of modern cities. For decades, we've been asking the wrong question: "How do we regulate generators better?" The right question is: "How do we eliminate generators entirely?"

Pop Wheels is answering that question with an infrastructure play that actually works. No government subsidy required. No massive upfront capital from the city. Just private operators building something that solves multiple problems simultaneously: environmental, economic, and quality-of-life.

The food cart pivot proves this isn't just theoretical. It's working. Real business owners are adopting it. Real customers are noticing the difference. Real regulatory interest is building.

The aggressive rollout starting this summer will tell us whether Pop Wheels can scale beyond the early adopters. If they can hit even modest targets—500 food carts, 50-70 cabinets, consistent operational metrics—they've proven something important: that battery swapping can work as essential urban infrastructure.

That's not just good for Pop Wheels. It's good for every city trying to figure out how to become more sustainable without breaking the existing street commerce ecosystem. Pop Wheels is essentially solving that problem and making money doing it.

Watcher this space over the next 18 months. If Pop Wheels executes the summer rollout, you'll see this become a case study in infrastructure innovation. And you'll probably see competitors emerge very quickly after that. That's how you know you're looking at a real market, not hype.

FAQ

What exactly is battery swapping for food carts?

Battery swapping for food carts is a system where food cart owners lease charged battery packs from a distributed network instead of relying on gasoline generators. Rather than waiting hours for a battery to charge on-site, owners can swap depleted batteries for fully charged ones in under two minutes at nearby network locations. Pop Wheels manages the charging infrastructure, battery maintenance, and inventory, while cart owners pay a subscription fee for unlimited access to the network.

How does Pop Wheels' charging cabinet technology prevent fires?

Pop Wheels designed its 16-slot charging cabinets with integrated fire suppression systems and individual outlet monitoring as part of its founding mission to prevent e-bike battery fires. Each cabinet includes thermal management through ventilation, real-time electrical monitoring to detect fire risk, and automated suppression systems. The company also uses embedded battery management systems that communicate with the network to track voltage, current, and temperature, catching problems before they become dangerous.

What are the actual cost savings for food cart owners switching from generators to battery power?

A typical food cart owner currently spends

Why did Pop Wheels pivot from just serving delivery workers to food carts?

Pop Wheels' founder realized that their core infrastructure—fire-safe battery swapping cabinets—could serve multiple use cases beyond delivery riders. When they learned about New York City's decarbonization initiatives for street vendors, they ran the numbers and found that food cart power requirements aligned well with their battery capacity and existing cabinet network. The pivot was driven by identifying an underserved problem that their existing infrastructure could solve economically.

What's Pop Wheels' regulatory strategy for the food cart expansion?

Pop Wheels is working closely with the Street Vendor Project, a nonprofit advocacy organization, to navigate regulatory pathways. They're positioning battery swapping as an enabling solution for New York City's decarbonization goals. The company is betting that regulations will eventually restrict or eliminate generators in commercial zones, making battery solutions mandatory rather than optional. This regulatory tailwind motivates both adoption and government partnership.

How does battery degradation affect food cart operators over time?

Battery packs naturally degrade over charging cycles, typically losing 3-5% of capacity annually under standard use. However, Pop Wheels manages this through optimized charging protocols that slow degradation to 1-2% annually. Older batteries (those dropping below 80% of original capacity) get rotated out of the main delivery rider fleet into food cart use, where slightly reduced capacity is acceptable. This staged rotation maximizes infrastructure value and allows Pop Wheels to offer consistent service to all customer segments.

What happens to food cart operators if a Pop Wheels cabinet is empty or broken?

This is a legitimate operational risk that Pop Wheels must address through service-level agreements and redundancy planning. The company needs to maintain cabinet availability above 95% and provide backup power solutions for essential operators. Customers should negotiate for guaranteed uptime commitments and backup options. Strategic cabinet placement across neighborhoods and predictive modeling of demand help prevent stockouts, but hardware failures remain a real concern that requires robust customer service response protocols.

Can Pop Wheels' model work in other cities beyond New York?

Yes, the model is highly replicable in dense urban areas with significant street vending populations and regulatory pressure to reduce emissions. Cities like San Francisco, Washington DC, Philadelphia, London, and Toronto all have similar conditions: street vending industries, generator pollution concerns, and regulatory interest in decarbonization. The infrastructure approach doesn't depend on New York-specific factors. Pop Wheels' challenge will be achieving unit economics in cities where real estate availability and regulatory support might differ.

What prevents larger companies from replicating Pop Wheels' battery swapping network?

The main barriers are regulatory relationships, early-stage capital efficiency, and focus. Large logistics companies like UPS or DHL have investigated battery swapping but haven't prioritized it because their core business is profitable without it. Pop Wheels' advantage isn't technology—it's infrastructure relationships and regulatory momentum. However, once Pop Wheels proves the concept at scale, larger competitors with deeper pockets could eventually disrupt them unless Pop Wheels builds strong network effects and customer loyalty.

What's the environmental impact potential if food cart battery swapping reaches significant scale?

If Pop Wheels achieves 5% penetration of New York's estimated 10,000 food carts, that's approximately 500 carts eliminating roughly 2,500 gallons of annual fuel consumption and reducing CO2 emissions by 27.5 metric tons annually. Beyond carbon, elimination of generators removes significant sources of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds that damage air quality and public health. The noise pollution reduction from 80+ decibel generators to 40-50 decibel battery operation represents genuine quality-of-life improvement in neighborhoods where street vending concentrates.

Key Takeaways

Pop Wheels demonstrates that infrastructure innovation in urban commerce can solve environmental, economic, and quality-of-life problems simultaneously without requiring government subsidies. The battery swapping model works because it aligns incentives: food cart owners save money, Pop Wheels gains recurring revenue, customers experience better environments, and cities achieve emissions reduction. The success of this summer's aggressive rollout will signal whether distributed battery infrastructure can become foundational urban utility. The competitive window for Pop Wheels is probably 18-24 months before larger players recognize the market opportunity. Food cart sustainability represents a genuine business opportunity with meaningful environmental impact, proving that "doing good" and "making money" aren't mutually exclusive.

![How E-Bike Battery Swapping Powers Food Carts: The PopWheels Model [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-e-bike-battery-swapping-powers-food-carts-the-popwheels-/image-1-1769272560479.jpg)