AI Data Centers & Carbon Emissions: Why Policy Matters Now

Last month, I had coffee with an engineer who manages infrastructure for one of the major cloud providers. We talked about AI, scaling, the usual stuff. Then he dropped something that stuck with me: "We're not energy-constrained by physics anymore. We're constrained by policy."

That sentence haunts me because it's true. The technology works. The servers run. The models train. But the electricity question—where it comes from, how much it costs, what it does to the atmosphere—that's where things get complicated.

Right now, the US is facing a choice that looks deceptively simple on paper but has massive real-world consequences. The AI boom is coming. The electricity demand is coming with it. The only question is: what powers it?

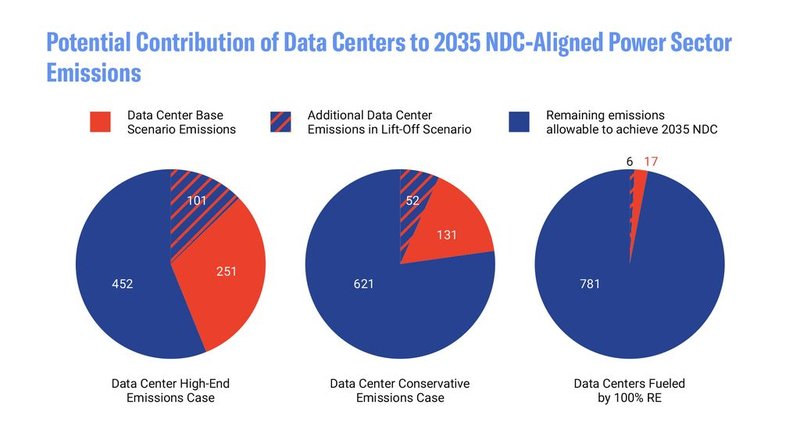

A recent analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists looked at exactly this scenario, modeling what happens to US carbon emissions over the next decade if we don't change course. The findings are stark, but they're also not inevitable. Let me break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and more importantly, what could actually fix it.

TL; DR

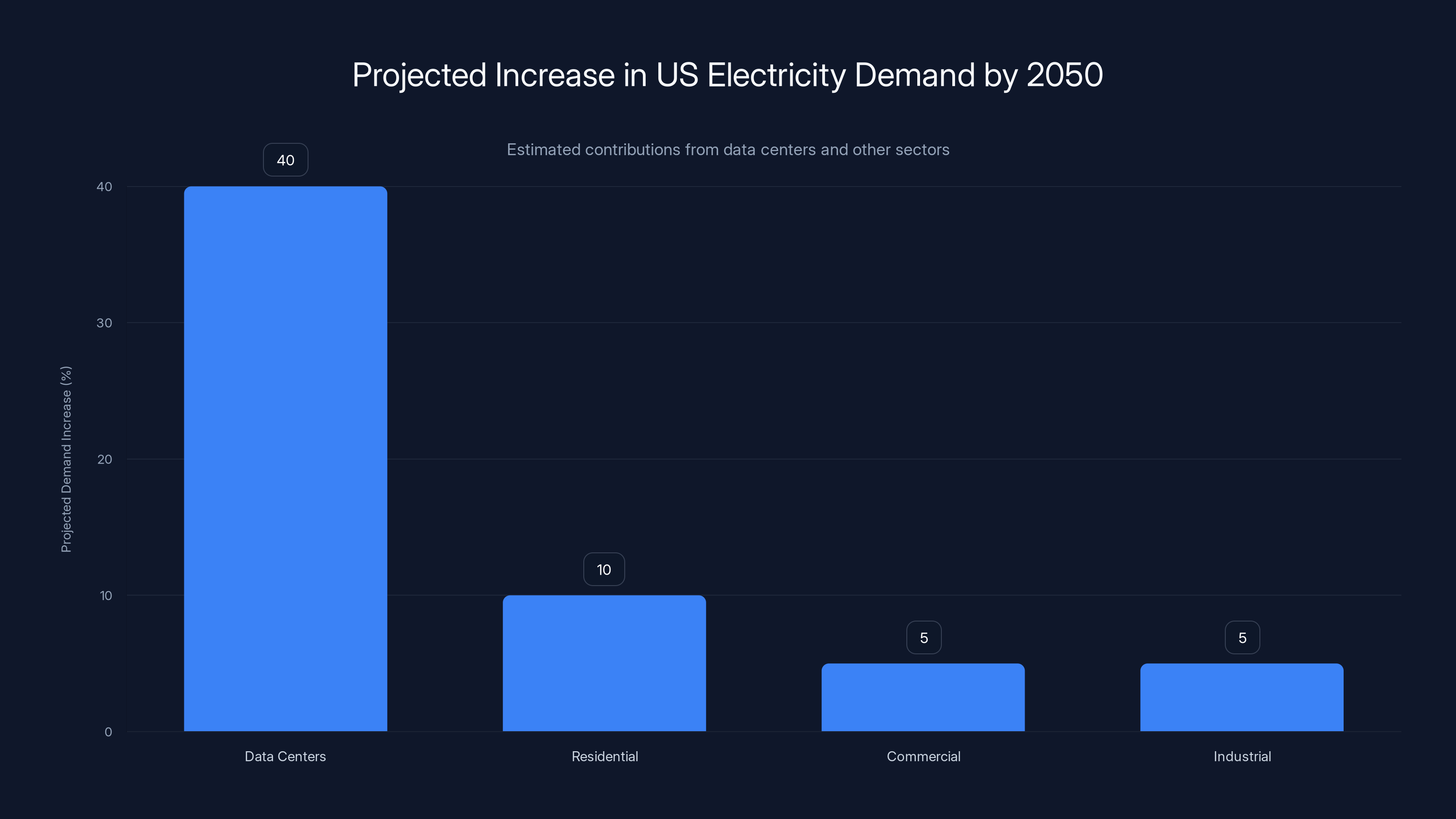

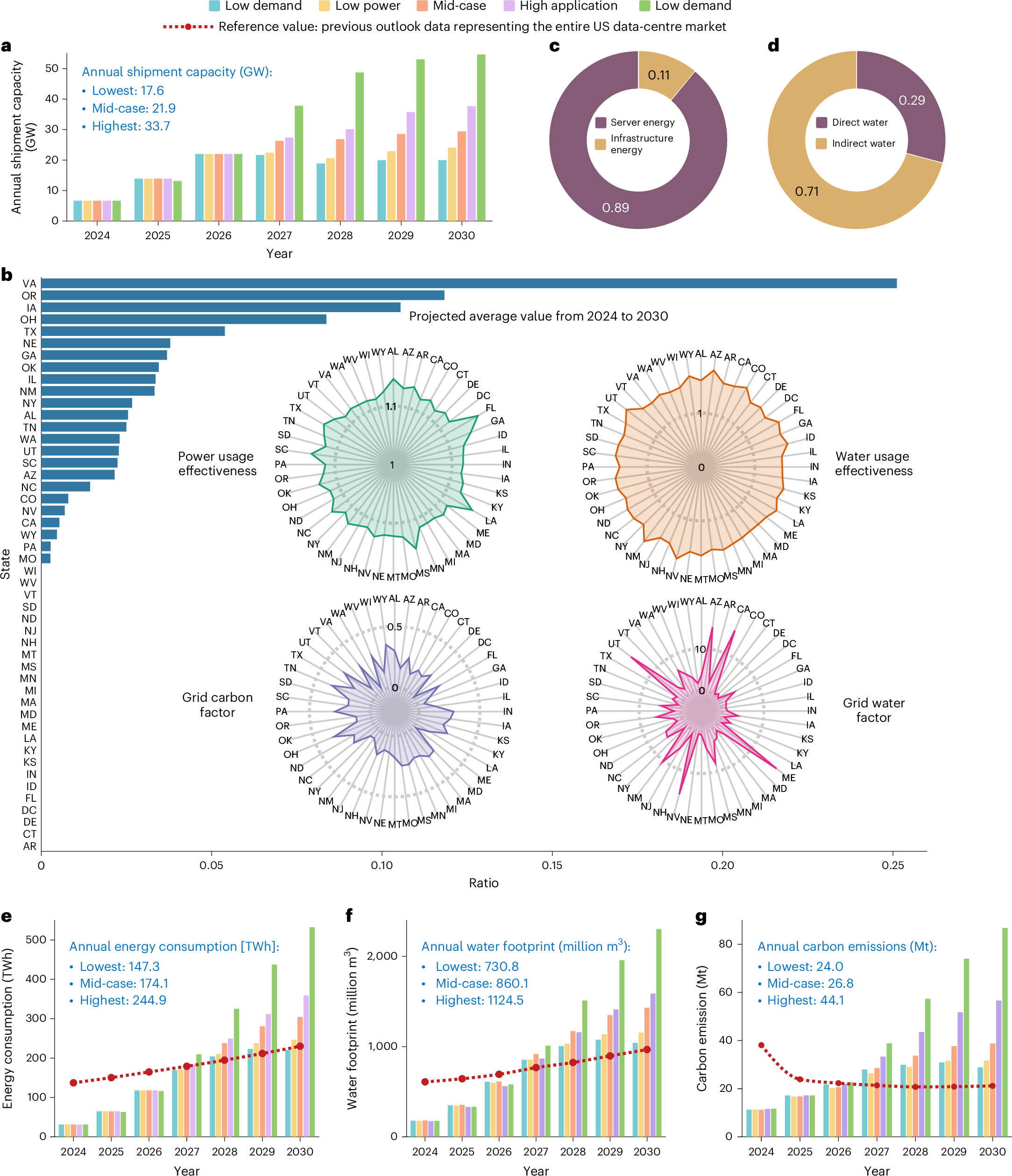

- Data center electricity demand will more than double: US power demand could jump 60-80% by 2050, with data centers driving more than half of that growth by 2030

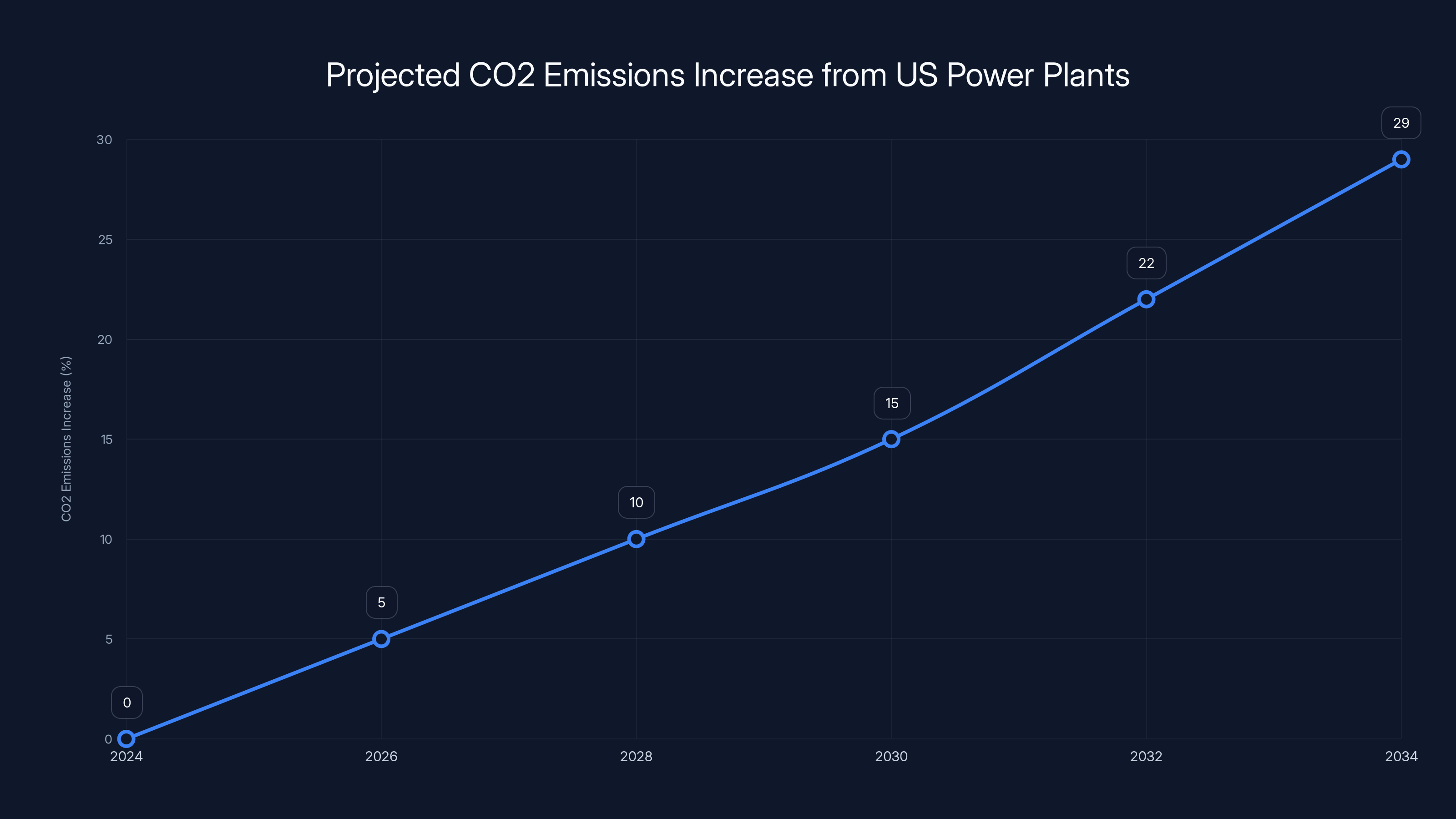

- Carbon emissions will spike without policy change: Without new renewable energy policies, CO2 emissions from power plants could rise 19-29% over the next decade just from data center energy needs

- Renewables are the solution, not the problem: Restoring tax credits for wind and solar could cut data center-related emissions by over 30% while potentially lowering electricity costs by 2050

- Current policy is actively making things worse: Federal administration actions against renewable projects are creating bottlenecks and sending signals that discourage clean energy investment

- Tech companies aren't pushing back enough: Despite climate commitments, major tech firms are largely staying silent on energy policy, focusing instead on minor community relations gestures

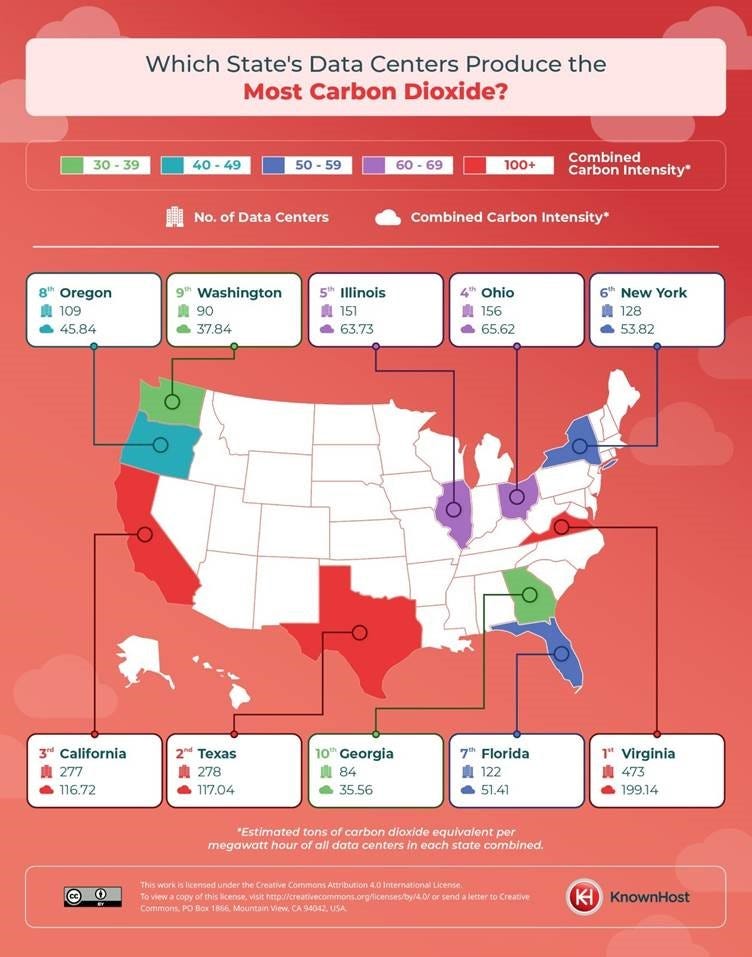

Data centers are projected to account for 40% of the 60-80% increase in US electricity demand by 2050, highlighting their significant impact on future energy needs. Estimated data.

Why Data Centers Are About to Dominate US Energy Demand

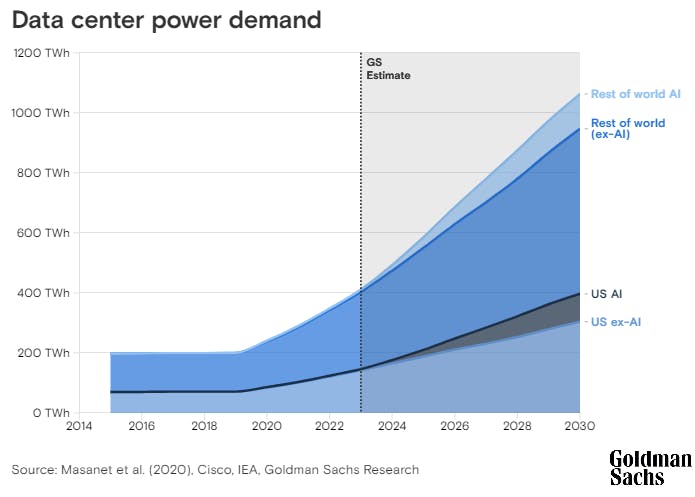

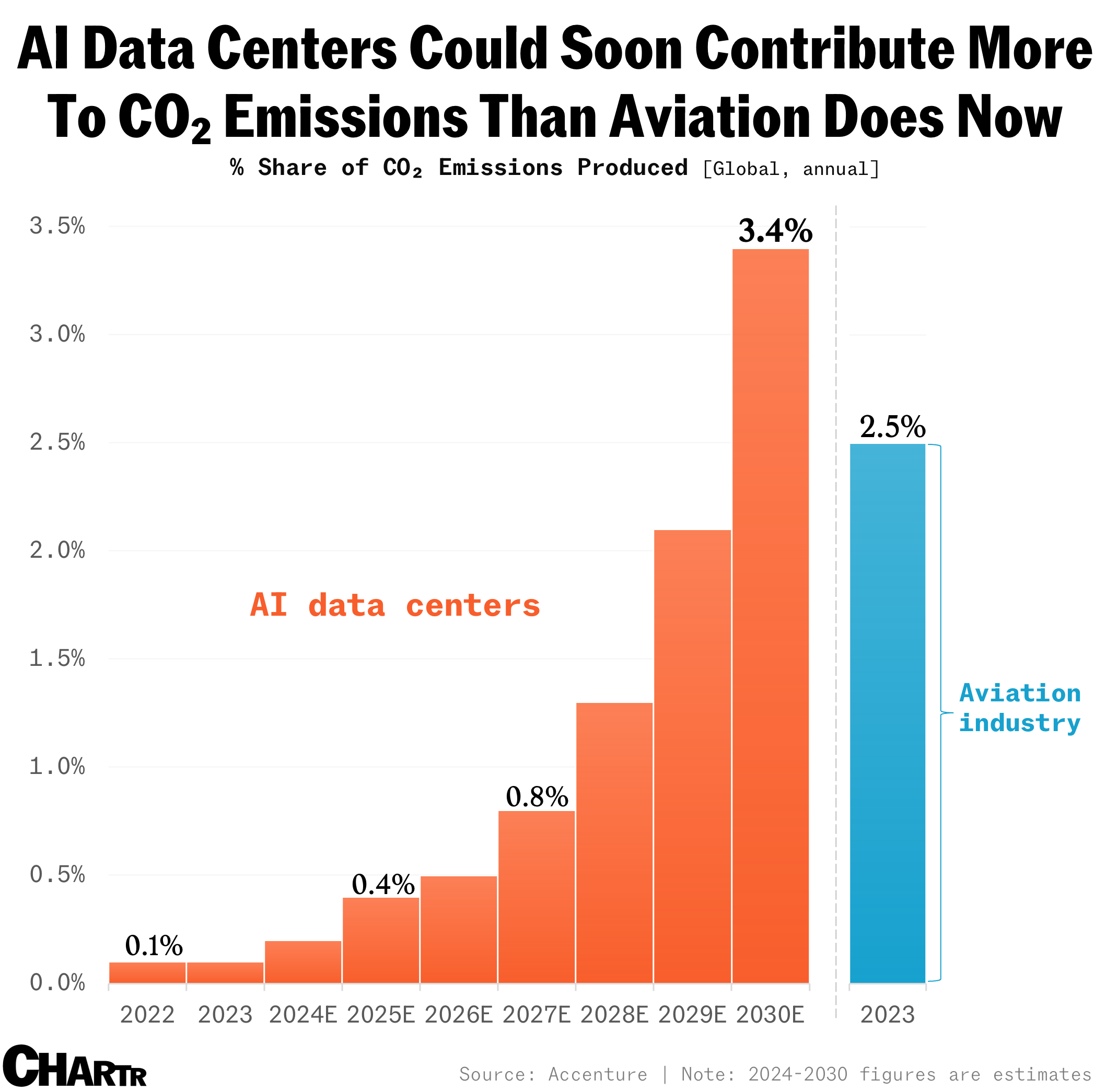

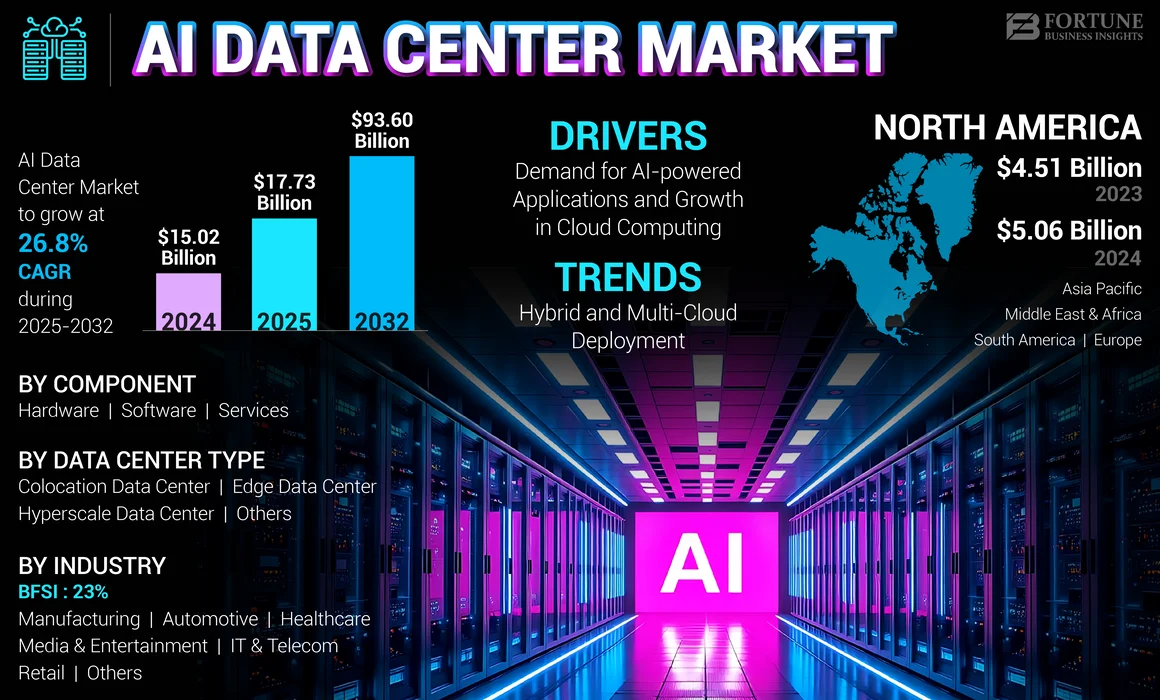

Let's start with the basics, because the scale here is genuinely hard to visualize. Data centers aren't new. Google's had them for years. Microsoft runs Azure across continents. Amazon dominates cloud infrastructure. What's different now is the velocity.

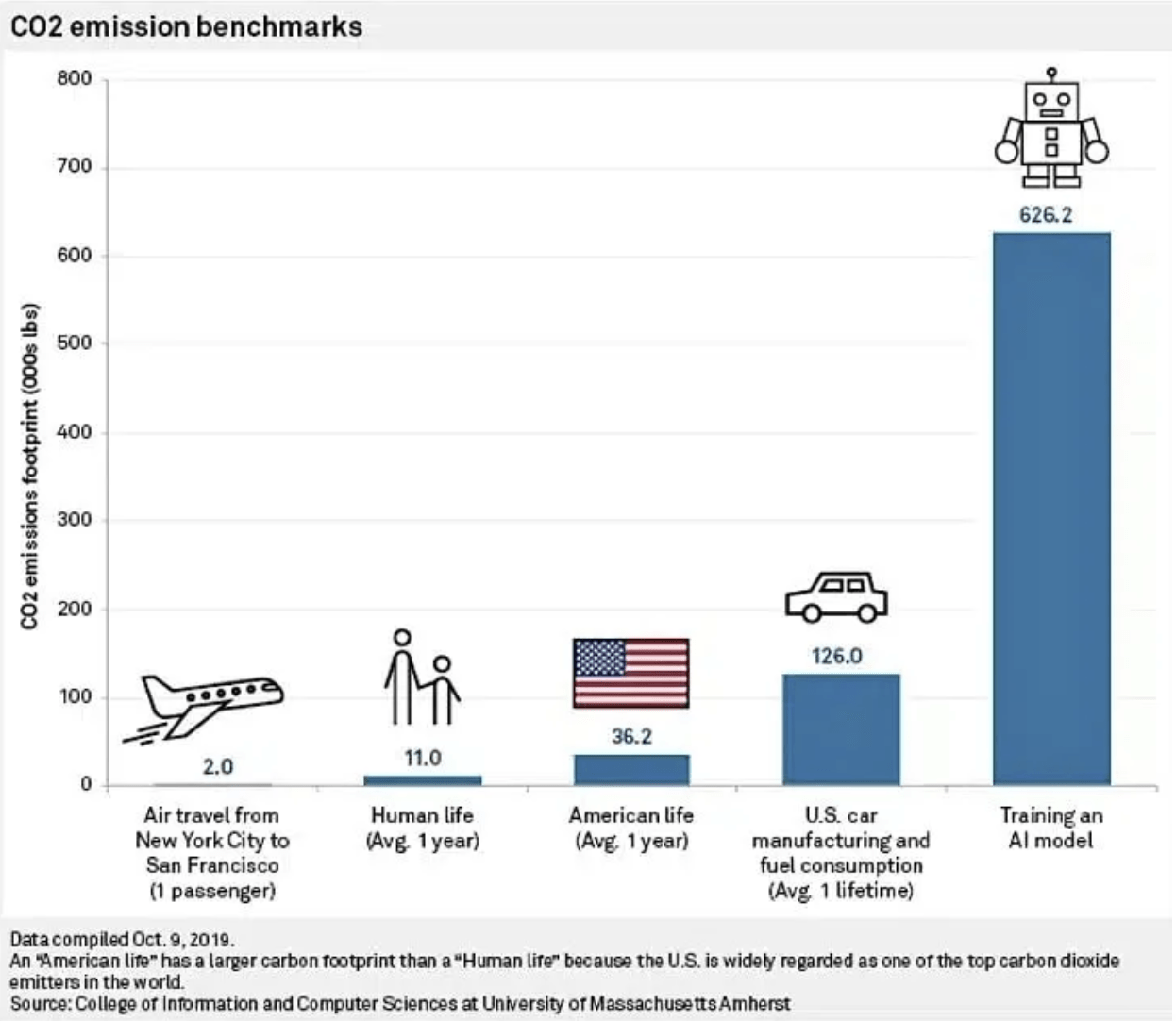

Artificial intelligence—specifically the training and inference of large language models—demands more compute power than traditional cloud workloads. A single training run for a large model can consume as much electricity as a small city runs in a month. Inference requests add up fast too. Every ChatGPT query, every Claude response, every time someone uses GitHub Copilot or Gemini, that's electricity being burned somewhere.

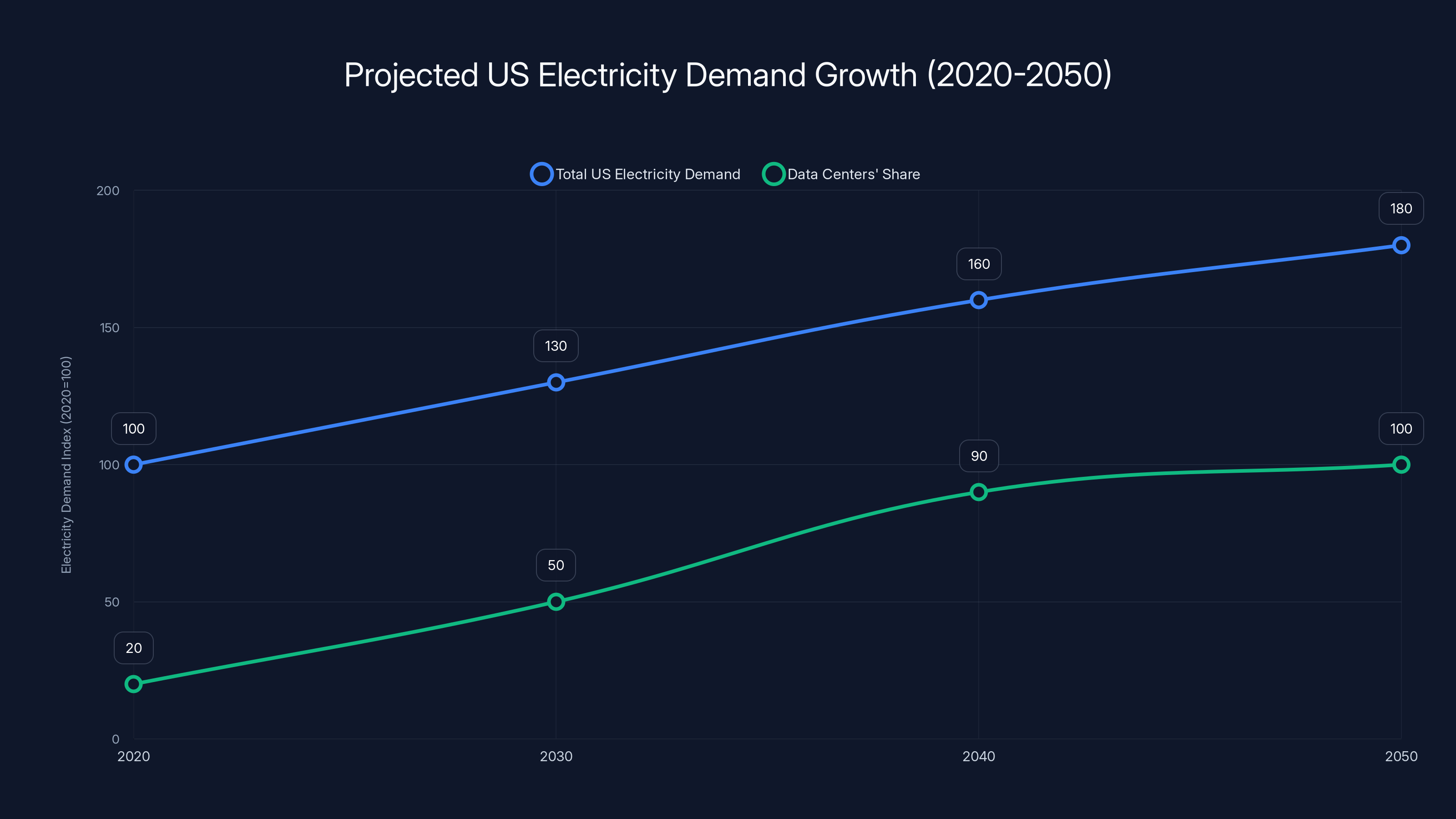

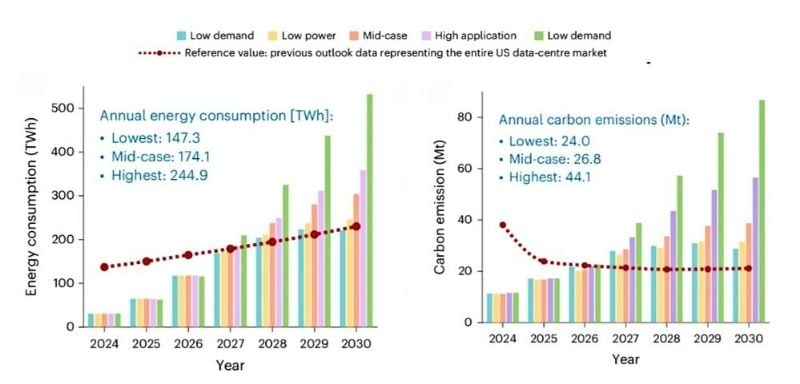

The numbers are staggering. The UCS analysis projects that US electricity demand will grow 60 to 80 percent through 2050. Let's anchor that for a second. That's not gradual. That's transformative. And here's the kicker: data centers alone will account for more than half of that increase by the end of this decade.

Why such aggressive growth? A few factors converge:

First, the absolute growth in AI adoption is accelerating. Companies aren't just using AI for research anymore. They're embedding it into products, running it on customer-facing infrastructure, using it for internal operations. Every business suddenly wants "AI" somewhere in their tech stack, whether that makes sense or not.

Second, the models themselves keep getting bigger. GPT-4 required more compute to train than GPT-3. Future models will require more again. This isn't a plateau—it's a compounding curve. Each generation wants more parameters, more training data, more computational cycles.

Third, inference is the hidden killer. Training happens once (mostly). Inference happens constantly. If a thousand people use a service powered by AI every hour, that's thousands of inference queries running every single hour, every single day. Scale that across millions of users and multiple AI services, and inference becomes the primary electricity consumer in this new paradigm.

What's interesting is how scattered the estimates are. When you read headlines, you see wildly different projections. Some data centers claim they'll need X amount of power. Utilities project Y. Analysis firms estimate Z. Why the variance?

Companies shopping for data center locations often pitch the same project to multiple utilities to get the best deal. This inflates overall demand projections. A single proposed data center might show up in three different utility forecasts as three separate projects. When those utilities pool their estimates, it looks like 3X the actual demand.

PJM, one of the largest regional transmission operators in the country, actually downgraded its energy demand projections recently after more carefully vetting some data center proposals. They realized they were overestimating. That's refreshing, actually. But it also means previous estimates were probably too high.

The UCS analysis tried to account for this by using middle-range growth scenarios and assuming that only about half of publicly announced data center projects would actually be built. That's probably reasonable. Some projects get cancelled. Others get delayed. Environmental review takes time. Land acquisition complications happen.

But even with those conservative assumptions, the picture remains dramatic. The demand for electricity from data centers over the next decade is going to be substantial, and it's going to grow faster than almost any other electricity demand sector.

Data centers are projected to account for over half of the US electricity demand increase by 2050, driven by AI adoption and larger model requirements. Estimated data.

The Carbon Emissions Problem: 19-29% Increase Over a Decade

Now let's talk about what happens if we don't change anything.

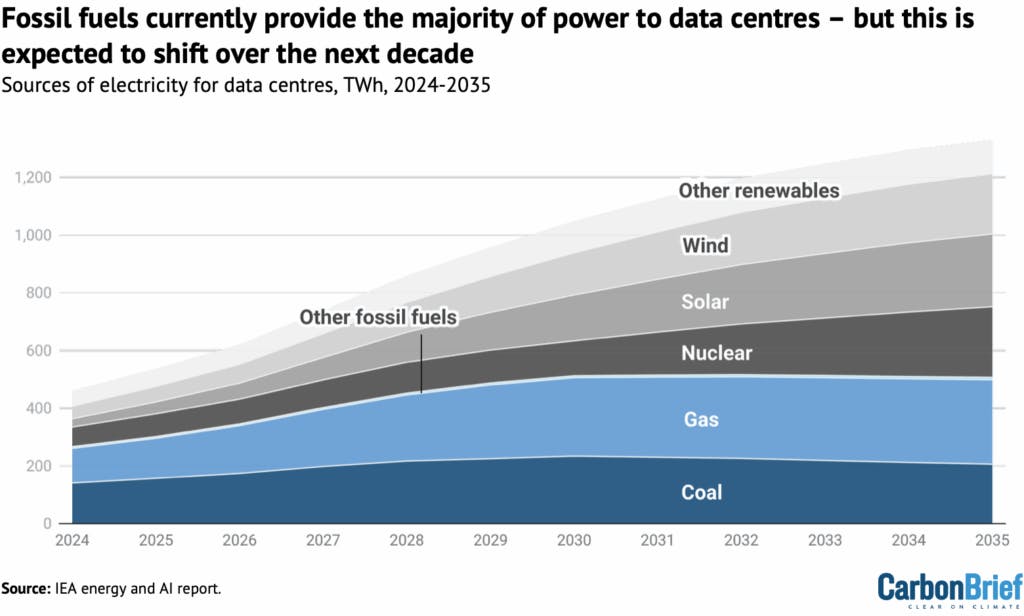

Power plants in the US are responsible for about a quarter of the country's total greenhouse gas emissions. They're the second-largest source after transportation. And over the past few years, something important happened: emissions from the power sector had actually been declining. Renewables were growing. Coal was shutting down. The trend was positive.

Then 2024 happened. Emissions ticked up slightly. For the first time in a couple of years, power sector emissions increased rather than decreased. Why? Demand from commercial buildings—primarily data centers—was the main driver of that increased electricity consumption, which required bringing more fossil fuel capacity online.

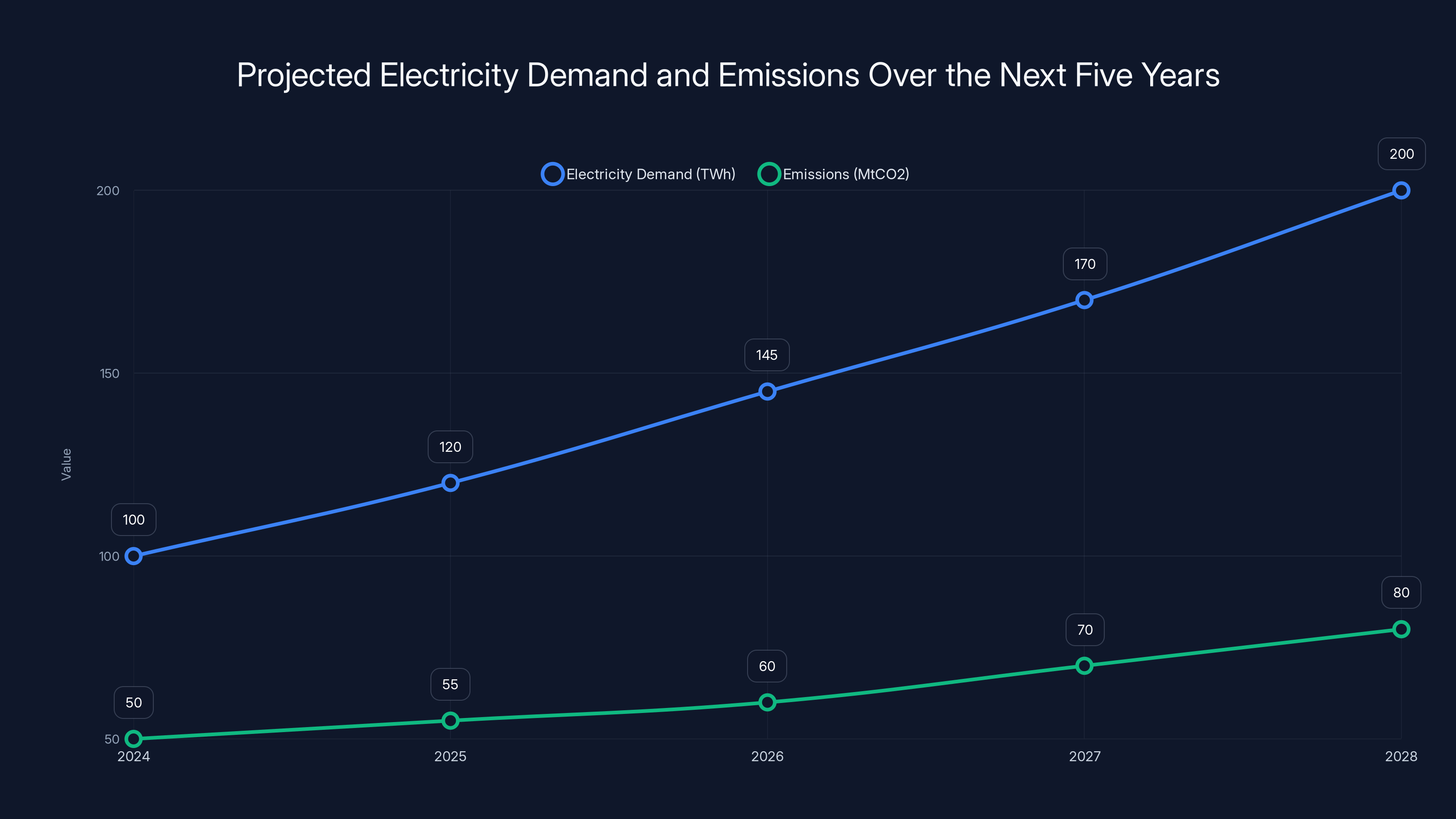

If that trend accelerates without policy intervention, the UCS modeling shows something sobering: between a 19 and 29 percent increase in CO2 emissions from US power plants tied specifically to data center energy demand over the next ten years. That's not marginal. That's a reversal of the progress the country has made on decarbonizing electricity.

Let's think about what that means practically. The US power sector was finally moving in the right direction. Coal plants were closing. Natural gas was (relatively) cleaner than coal. Wind and solar were expanding. We were making progress on climate.

Now imagine adding 60-80% more electricity demand on top of that, powered primarily by fossil fuels because that's what's available, because coal and gas plants exist and renewables take time to build. The carbon accounting gets ugly fast.

There's a mathematical way to think about this. The carbon intensity of your electricity grid (measured in grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour) multiplied by your total electricity consumption equals your total emissions. If you increase consumption by 60% and your grid gets dirtier because you're relying on more fossil fuel plants to meet that demand, your emissions don't just go up proportionally. They spike.

Where carbon intensity increases as you bring fossil fuel plants online to meet new demand, the multiplier effect compounds the problem.

Now, the 19-29% range reflects different policy scenarios. If no policies change and fossil fuels dominate new capacity, you're looking at the higher end. If some renewables get built, maybe you're closer to 19%. But all of these scenarios assume the current policy environment stays roughly the same.

That's important because the current policy environment is actively working against renewables right now.

How We Got Here: The Energy Situation Today

To understand the problem, you need to know what the current energy landscape looks like.

The US grid is a patchwork of different systems, different rules, different incentives. You've got investor-owned utilities that make more money when they sell more electricity. You've got municipal utilities that operate non-profit. You've got rural cooperatives. You've got regional transmission organizations like PJM, ERCOT in Texas, ISO New England, and others that manage the grid across multiple states.

This fragmentation is partly why the US has had such a hard time deploying renewables quickly. You don't have a single decision maker saying "let's build wind farms here." You have dozens of different entities with different incentives, different capital structures, different regulatory environments.

Historically, when there was more electricity demand, utilities built power plants. Coal plants, mostly, because coal was cheap and the environmental costs weren't priced into the system. Later, natural gas became cheaper and less politically toxic. Utilities built gas plants.

Renewables—wind and solar—were always cheaper per unit than people expected, but they came with a political problem. They're not dispatchable. The sun doesn't shine when you need it. The wind doesn't blow predictably. So there's an engineering problem to solve around grid stability and storage. That's solvable (battery technology has improved dramatically), but it's an additional cost layer that fossil fuels don't have in the same way.

Then you add the policy layer. Tax credits for renewables (good). Regulatory frameworks that protect coal plants (bad). Subsidies for fossil fuels (very bad). Delays in grid modernization (bad). These policies compound.

Over the past couple of decades, renewables have gradually become cost-competitive with fossil fuels, especially when you include the environmental costs and the falling price of batteries. Some estimates suggest that wind and solar are now the cheapest way to generate new electricity capacity in most of the US, even without subsidies.

But policy uncertainty kills deployment. If you're a company thinking about building a wind farm and you're not sure if the tax credits will still exist in five years, that changes your financial model. It makes the project riskier. It means higher financing costs. It means maybe you don't build it.

The past year has seen that policy uncertainty spike dramatically. The current federal administration has made it explicitly clear that it wants fossil fuels—specifically coal, the dirtiest form of energy—to power the AI boom.

Electricity cost is the most significant factor for tech companies considering energy policy, followed closely by reliability and corporate reputation. Estimated data.

The Federal Policy Assault on Renewables

Let's be specific about what's actually happening with federal policy right now, because the moves have been aggressive and coordinated.

The Trump administration has taken several concrete actions:

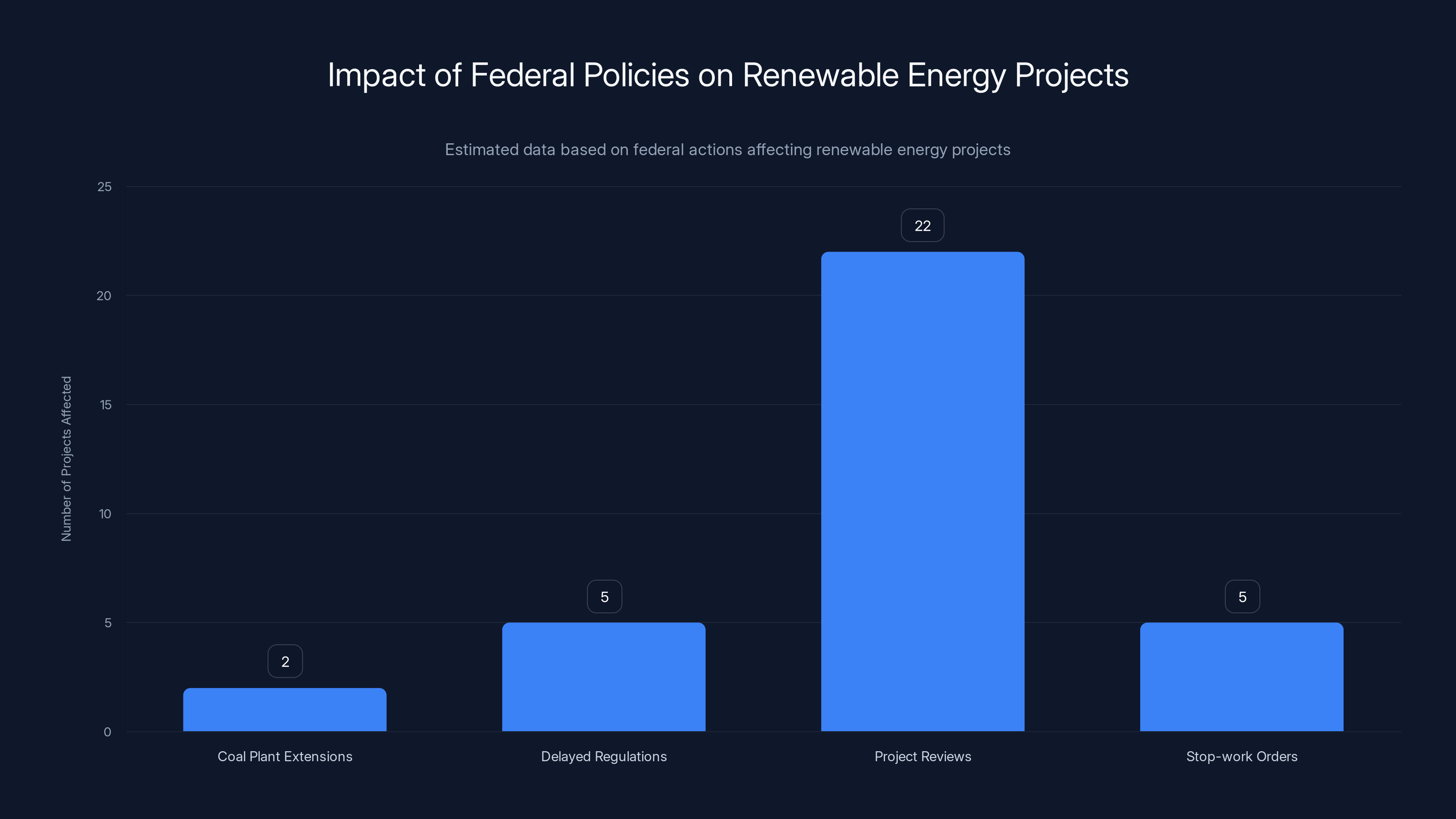

Energy secretary Chris Wright ordered at least two coal-fired power plants to stay online past their retirement dates. These plants were scheduled to close because they weren't economically viable anymore. But the administration essentially forced them to keep running, treating them as strategic infrastructure.

The White House and EPA have pushed multiple policies that benefit the coal industry. These include delayed regulations that would otherwise accelerate coal plant retirement, changes to how environmental reviews work, and removal of restrictions on coal expansion.

An Interior Department policy now mandates review of all wind and solar projects on federal lands. This sounds procedurally benign. In practice, it's created a bottleneck of absolutely staggering proportions. Twenty-two gigawatts of renewable projects are stuck in review limbo. Let's put that in context: that's enough renewable capacity to power more than 16 million homes.

Twenty-two gigawatts. That's not trivial. That's transformative capacity that could be operating right now, generating power, reducing the need for fossil fuels.

In December, the administration issued stop-work orders for five East Coast wind farms that were already under construction. These projects had gone through environmental reviews, had approval, were actively being built. The administration halted them citing "national security concerns." (Three judges subsequently ruled that construction could proceed, but the signal had been sent.)

Steve Clemmer, the lead author of the UCS analysis and director of energy research there, described the situation bluntly: "The Trump administration is doing this with projects that have already been approved and are under construction. It sends a chilling signal to the industry, and to efforts to power data centers and meet electricity demand. We need to build as much as we can, as fast as we can."

He's right. The problem isn't just what's being blocked. It's the uncertainty it creates. If you're a company thinking about investing billions in renewable generation capacity and the federal government is unpredictably halting projects that have already been approved, that makes your investment decision harder. You have to account for policy risk in your financial models. That makes renewables look worse compared to fossil fuels, which still get to operate under the old rules.

The UCS analysis actually accounts for some of these policy headwinds, including withdrawal of renewable tax credits, coal plant retirement delays, and some offshore wind project cancellations. But it doesn't account for everything. The Interior Department bottleneck, for example, wasn't fully modeled because it's still evolving and its full impact isn't entirely clear.

What that means is the UCS analysis might actually be conservative. The real-world policy environment might be worse than what they modeled. The emissions increase could be at the high end of that 19-29% range, or possibly even higher.

Why Fossil Fuels Aren't Even the Cheapest Option Anymore

Here's something interesting: despite the administration's push for coal and natural gas, fossil fuels might not even be the economically optimal choice anymore. And that's creating an awkward dynamic.

Natural gas is becoming constrained. Demand for new gas turbines has skyrocketed because utilities are trying to add capacity fast to meet data center demand. But manufacturing new turbines takes time. Lead times for new natural gas plant construction are stretching into years. We're talking five to seven year wait times for some projects. That's a long time to wait when you need capacity now.

Renewables—wind and solar—can be built faster. They can be deployed modularly (you don't have to build a massive 1,000 MW facility; you can build a 100 MW farm and expand it). They're increasingly cost-competitive.

So you have a situation where the federal government is actively pushing fossil fuels, but the market logic is pointing toward renewables. That's creating a disconnect.

Some power providers are pushing back. PJM, the regional transmission organization covering 13 states and Washington DC, actually filed a brief supporting a Virginia offshore wind developer that sued the Trump administration over the project blocking. In their brief, PJM argued that the wind project, which would provide enough power for 600,000+ homes, "is important to meet a rapidly increasing demand for electric power."

That's significant. PJM is essentially saying: we need this project. Not for environmental reasons, although those matter. But for grid reliability and capacity. PJM is a creature of the market. They're saying the market demands renewable generation.

Other utilities and grid operators are likely thinking similarly. They have to keep the lights on. Renewable capacity helps them do that. Blocks on renewable projects create problems for them, not solutions.

Estimated data shows a steady increase in electricity demand and emissions over the next five years, highlighting the need for policy shifts towards renewable energy to stabilize emissions.

The Solution That Actually Works: Renewable Energy Policy

So what's the fix? The UCS analysis modeled this specifically. If you bring back tax credits for wind and solar—essentially restoring policies that existed but faced political attacks—what happens?

The numbers are pretty remarkable. Restoring renewable tax credits would cut CO2 emissions by more than 30 percent over the next decade, even accounting for the large amount of new electricity demand from data centers. That's not a small difference. That's moving the needle.

More interesting still, the analysis shows that renewable policies could also make wholesale electricity costs go down by about 4 percent by 2050, after a slight rise over the next decade. This is the key point that often gets missed in these discussions: renewable energy deployment isn't just good for the climate. It's economically rational.

Why? A few mechanisms:

First, renewables have zero fuel costs. A wind turbine or solar panel, once built, produces electricity at essentially zero marginal cost. There's no coal to buy, no natural gas to purchase. You just turn it on. Compare that to fossil fuel plants, which have to purchase fuel continuously. When wholesale electricity prices are determined by the marginal cost of the last plant needed to meet demand (which is usually how electricity markets work), having renewable plants in the mix changes the economics.

Second, renewable tax credits reduce the effective capital cost of building renewable capacity. A 30% tax credit on a wind farm makes the project more attractive, which accelerates deployment, which increases supply of renewable electricity, which drives down prices over time.

Third, renewables scale down the need for expensive peaking plants. Electricity grids always need some amount of peaking capacity—plants that run when demand is highest. These are often expensive, inefficient plants. If renewables are providing more of the baseline load, you need fewer peaking plants. That drives down system-wide costs.

The UCS analysis shows that these mechanisms actually play out in the modeling. Restoring renewable policies leads to more renewable deployment, which leads to lower electricity prices long-term.

Now, there are some caveats. The analysis does show a slight increase in electricity costs over the next decade even with renewable policies restored, because electricity demand is growing so fast. Building out infrastructure to meet surging demand always costs something. But the long-term trajectory (out to 2050) is lower costs with renewables than with fossil fuels.

This contradicts the framing that renewable policies are expensive. In the long run, they're economically optimal. The short-term bump in costs reflects the reality that we're scaling up infrastructure fast, not a failure of renewable policy.

What Big Tech Is Actually Doing (Spoiler: Not Enough)

Here's where things get frustrating. Over the past few years, major tech companies—Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta—have made public commitments to climate action and emissions reduction. They pledged to reach carbon neutrality, to match their electricity consumption with renewable energy, to drive down the emissions intensity of their operations.

Then AI exploded. Data center demand surged. And suddenly, those commitments were quietly walking backward. Companies were doing the emissions accounting gymnastics—counting "renewable energy credits" differently, adjusting their baseline years, moving goalpost definitions around. The net effect was that emissions were going up while the companies maintained their climate rhetoric.

It's not that companies consciously set out to break their promises. It's that the math of exponential AI growth made the original promises incompatible with the business trajectory. You can't commit to carbon neutrality while 3x-ing your electricity consumption if your grid isn't carbon-neutral. Those two things don't fit together.

What's notable is what companies are not doing. They're not pushing back against the federal government on renewable policy. They're not publicly advocating for renewable deployment. Microsoft didn't mention emissions or climate policy in recent commitments to "be better neighbors" to communities hosting their data centers. The commitments focused on local taxes, local jobs, community benefits—legitimate concerns, but conspicuously absent: how do we power this sustainably?

Why the silence? Probably a mix of factors:

First, it's politically contentious. Advocating for renewable energy policy means taking a position that the current administration opposes. Tech companies are risk-averse when it comes to confrontational politics. They'd rather donate to both parties and stay neutral.

Second, they're not sure how seriously the federal government takes their input on energy policy. Tech companies have leverage on some issues (antitrust, immigration) but not necessarily on energy. Why spend political capital on an issue where you're not sure you have influence?

Third, there's an implicit calculation that the market will eventually force this issue. Grid operators need capacity. If renewables are the fastest way to add capacity, operators will deploy them. Why push for policy when the market might solve the problem?

That last point might be true. But it's also potentially dangerous from a climate perspective. Market dynamics are slow. Climate impacts are accelerating. Waiting for market forces to allocate capital toward renewables when federal policy is actively blocking renewable projects is not a high-confidence strategy.

Projected data shows a potential 19-29% increase in CO2 emissions from US power plants over the next decade, driven by rising data center energy demand. Estimated data.

The Efficiency Wildcard: Could Technological Advances Save Us?

One thing worth considering is the possibility that technological advances could make data centers and AI models much more energy-efficient over the next several years.

It's not fanciful. We've seen remarkable improvements in AI efficiency already. Models that would have required 10x more compute five years ago now run on standard hardware. Training times have come down. Inference optimization techniques are constantly improving.

Some of the most extreme estimates for data center electricity demand—the ones that make headlines—probably overestimate future need because they don't account for efficiency gains. We're not going to be running the same AI models at the same computational cost in 2035 as we run them in 2025. Hardware will improve. Software will improve. Models will become more efficient.

But here's the thing: this efficiency improvement doesn't solve the problem. It might slow the growth rate, but it doesn't reverse it. Even if efficiency improves dramatically, the sheer number of AI inference requests is growing fast enough that total electricity consumption still increases.

It's like the Jevons paradox—as something becomes more efficient, you actually use more of it, so total consumption goes up. More efficient AI might make it economical to use AI in more places, for more tasks, at scale. Total electricity consumption still rises.

That said, efficiency improvements do buy time. They reduce how badly the problem manifests, which gives policy time to catch up.

Regional Grids: Where the Rubber Meets the Road

The national electricity grid is actually a collection of regional grids with different characteristics, different rules, different environmental mixes.

Texas (ERCOT) is heavy on wind and gas. It's been pretty responsive to renewable deployment because wind is economically attractive and there's political support. But ERCOT has also had reliability challenges during extreme weather events.

The Northeast (ISO New England, PJM) is a mix of coal (being phased out), natural gas, nuclear, and increasing renewables. These regions have been pushing for offshore wind as a major supply source. PJM's recent actions supporting wind farms against federal blocking shows the regional variation in policy approach.

The Southwest (WECC) has abundant solar resources. California has pushed aggressively on renewable deployment. But California's extreme electricity prices in recent years created political backlash, complicating the picture.

Where data center deployment happens matters a lot. A data center in Iowa will have a different carbon footprint than one in West Virginia because Iowa's grid is cleaner. A data center in Texas will have different reliability characteristics than one in the Northeast.

This fragmented approach creates interesting dynamics. Companies can shop for locations not just based on real estate and labor costs, but based on electricity costs and grid characteristics. Some companies are explicitly seeking locations with clean electricity. Others are purely economic in their decision-making.

Regional grids also create opportunities for policy. A state or region could potentially use procurement rules or electricity pricing to incentivize cleaner data center development. If you require data centers to match their electricity consumption with renewable energy contracts, you're essentially forcing clean energy deployment. Some regions are experimenting with this approach.

Federal policies have significantly impacted renewable energy projects, with 22 GW of capacity in review and multiple projects facing delays or halts. Estimated data.

The Business Case for Tech Companies to Push Back on Energy Policy

Let's think about this from a tech company perspective. Why should they care about federal energy policy?

First, electricity cost is material to their bottom line. Data centers are massive consumers. Even a 1% difference in electricity cost compounds across thousands of facilities and billions of requests. If renewable policies drive down electricity costs, that's direct margin improvement.

Second, reliability matters. The power outages that shut down cloud services create massive reputational damage and lost revenue. A grid that's scaling to meet surging demand with the right mix of baseload and peaking capacity is more reliable than one that's hastily adding fossil fuel capacity to meet urgent demand. Renewable policies that accelerate diverse capacity deployment probably help reliability.

Third, corporate reputation is increasingly tied to climate stance. Investors look at this. Customers increasingly care. Employees care (maybe more than customers do). A company that's loudly advocating for climate policy while its business is exploding in carbon emissions looks hypocritical. A company that's willing to have hard conversations with policymakers about energy looks serious.

Fourth, long-term planning requires certainty. If a company is planning to operate data centers for the next 20 years, it needs to be able to predict electricity prices, regulatory environment, and grid reliability that far out. Advocating for stable renewable policy is a form of risk management.

None of this is rocket science. The business case is straightforward. Yet most tech companies have chosen not to make a major public push on federal energy policy. That's a strategic choice, and it's probably a mistake.

What Actually Needs to Change

So what's the concrete policy agenda that would actually move the needle on this problem?

The UCS analysis is pretty clear on this. You need:

1. Restore renewable energy tax credits. Wind and solar don't need massive subsidies anymore, but tax credits are an incredibly cost-effective way to accelerate deployment. The investment tax credit for solar and the production tax credit for wind are well-understood, economically efficient policies. Restoring these should be table stakes.

2. Unblock renewable projects on federal lands. That 22-gigawatt backlog isn't going to disappear on its own. You need a policy change that either eliminates the blocking review process or accelerates it dramatically. This is legitimately solvable—you just need a policy decision.

3. Modernize grid interconnection rules. One thing that doesn't get enough attention is how hard it is to connect new generation to the grid. The interconnection queue—the process of getting approved to connect your renewable project to the power grid—is incredibly slow. Some projects wait five years or more just to get connected, even after being built. Grid operators could streamline this process significantly without compromising reliability.

4. Implement carbon pricing or strengthen emissions standards for power plants. This is more politically contentious, but it's economically efficient. If CO2 has a cost, then coal and gas become less attractive compared to renewables. Carbon pricing doesn't need to be astronomical to move markets—even modest pricing creates meaningful incentives.

5. Invest in grid modernization and battery storage. The grid needs upgrades to handle the mix of renewable generation, peaking capacity, and storage needed to maintain reliability. This isn't a policy question so much as an investment question, but policy can accelerate it through funding and regulatory streamlining.

These aren't radical proposals. Most of them are just "do what we were doing before political opposition got in the way." That's the frustrating part. This isn't a hard technical problem. It's a policy problem. And policy problems are solved by political will, which is in shorter supply.

The Economic Tension: Why This Is Actually Hard

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: there's a real tension between keeping electricity cheap and keeping electricity clean.

Fossil fuel plants have sunk costs. Coal plants and natural gas plants were already built. The capital is already deployed. Running them has low marginal cost (you just buy fuel and operate them). From a short-term cost perspective, using existing fossil fuel plants is cheaper than building brand new renewable capacity.

New renewable capacity requires capital investment. You have to build the farms, install the equipment, wire them to the grid. That's expensive upfront. The operational costs are low (fuel is free), but the capital is significant.

In a rational, long-term economic perspective, renewables are cheaper when you account for the full lifecycle and externalities. But in a short-term cash flow perspective, using existing fossil fuel plants is cheaper.

Utilities and grid operators face this tension constantly. They need to keep electricity prices down for customers and shareholders. They also need to (theoretically) decarbonize. These push against each other in the short term, although they align long-term.

The way to bridge this gap is policy that changes the economics. Tax credits for renewables work because they reduce the upfront capital required, bringing the total cost closer to fossil fuels. Carbon pricing works because it adds cost to fossil fuels. Regulations that force fossil fuel plant retirement work because they remove the sunk-cost advantage.

All of these are policy tools. None of them are automatically economically optimal. They're ways of translating a political decision (we want clean electricity) into economic incentives that make that decision profitable.

The Wildcard: Voluntary Corporate Action

One scenario that's underexplored is whether tech companies could unilaterally accelerate renewable deployment through their procurement power.

Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta collectively have massive capital. They could, theoretically, just start signing long-term renewable energy contracts. Not the accounting tricks (renewable energy credits). Actual power purchase agreements where they're contracting for renewable generation and paying the cost premium if there is one.

Some companies have done some of this. Microsoft, for example, has signed renewable power purchase agreements. But the scale is not commensurate with their electricity demand. Most of their electricity still comes from whatever sources the grid operator has available.

If the big tech companies collectively decided "we're going to source 80% of our electricity from renewables by 2030" and actually made procurement decisions aligned with that goal, it would move the needle significantly. It wouldn't require federal policy changes. It would just require companies to prioritize climate over margin optimization.

Will they do this? Probably not voluntarily, at scale. Because it costs money (maybe not much, but some), and it's easier to not do it. Regulatory requirement or strong investor pressure might force it, but not voluntary decision-making.

That's a shame, because it's literally in their power to solve this problem partly. They're just choosing not to.

Looking Forward: The Next Five Years

So where does this go? What actually happens over the next five years?

Most likely scenario: a muddle-through. Data center electricity demand grows faster than expected. Some new renewable capacity gets built because the economics work. But federal policy remains hostile to renewables, so growth is slower than it otherwise would be. Electricity prices go up somewhat. Some fossil fuel plants stay online longer than they should. Emissions rise, but not catastrophically.

Optimistic scenario: Federal policy shifts (through election, court decisions, political pressure, whatever). Renewable deployment accelerates. Tech companies, forced by shareholder pressure or regulation, commit to matching their electricity consumption with renewables. The grid upgrades to handle new demand. Electricity prices stay relatively stable. Emissions are contained.

Pessimistic scenario: Federal policy doubles down on fossil fuels. Renewable projects keep getting blocked. Tech companies keep expanding without addressing electricity source. Natural gas becomes the dominant new capacity because it's faster to build than coal but still fossil fuel. Electricity prices rise significantly. Emissions spike. The AI boom becomes politically controversial because of energy costs and environmental impact.

Historically, the muddle-through scenario is most likely. Institutions are biased toward incrementalism. Change happens slower than it should.

But the electricity demand from AI is accelerating fast enough that muddle-through might not be a stable equilibrium. Either policy shifts to enable renewable deployment, or electricity prices spike so much that it forces political change. Something's gotta give.

Why This Matters Beyond Energy

This isn't just an energy issue or a climate issue. It's a fundamental question about how we build systems that run on exponential growth.

AI is genuinely useful. It solves real problems. It's going to be important infrastructure going forward. But infrastructure that's growing 60-80% in electricity demand over a decade needs to be built on clean energy. There's no way around it.

The question is whether we make that decision explicitly (through policy and investment) or whether we discover it the hard way through electricity price spikes and climate impacts.

From a systems thinking perspective, the current approach is backwards. We're letting market incentives drive deployment (companies want cheap electricity, so they build data centers) while letting policy incentives remain misaligned (fossil fuels are politically pushed, renewables are blocked). That's a recipe for an inefficient outcome.

The smart approach would be to align policy incentives with market incentives. Make clean electricity cheaper than fossil fuel electricity (through tax credits, carbon pricing, whatever mechanism). Then let market forces drive deployment toward clean energy. Problem solved.

Instead, we have policy pushing one way (fossil fuels) and market economics pushing another (renewables are often cheaper). That creates deadlock.

The Role of Innovation

One thing that deserves more attention is how policy affects innovation in energy.

If renewable policies are uncertain, companies don't invest in renewable technology innovation. If battery storage is blocked by regulatory uncertainty, battery companies can't plan long-term R&D. If grid modernization investment is delayed, equipment manufacturers don't innovate on the hardware needed for next-generation grids.

Conversely, clear renewable policy, stable investment tax credits, and regulatory clarity on grid modernization accelerate innovation across the entire energy system.

The UCS analysis doesn't explicitly model this, but it's a mechanism that could make the benefits of renewable policy even larger than the modeling suggests. Clear policy could drive innovation that makes renewables even cheaper, which compounds the benefits over time.

Conclusion: A Moment of Choice

The US is at a genuine decision point. The electricity demand from AI is coming. That's not in question. What's in question is what powers it.

If current policies continue, we're looking at a reversal of climate progress. Electricity demand spikes. Fossil fuels dominate new capacity because of policy incentives and existing infrastructure. Carbon emissions increase. Electricity prices maybe go up. Everyone's worse off.

If we change policy—restore renewable energy incentives, unblock renewable projects, modernize the grid, implement carbon pricing—we can power the AI boom cleanly. Electricity demand still grows, but renewables provide the new capacity. Carbon emissions stay flat or decrease. Electricity prices long-term are lower. Everyone's better off.

It's not a close call economically. Renewables win. It's not a close call environmentally. Clean electricity wins. The only question is whether we have the policy will to make it happen.

The analysis from UCS makes this starkly clear: we know how to solve this problem. We know what policies work. We know they're economically beneficial. We're just not doing it for political reasons.

That's a choice, and it's one we can change.

FAQ

What is the primary driver of increased electricity demand in the US over the coming decade?

Data centers and AI infrastructure represent the dominant source of new electricity demand in the US. The UCS analysis projects that data centers alone will account for more than half of the projected 60-80% increase in total US electricity demand through 2050, with the most significant growth happening by 2030. This represents a dramatic shift from historical patterns where residential and commercial building demand dominated electricity growth.

How much will carbon emissions increase if current energy policies remain unchanged?

Without policy intervention, CO2 emissions from US power plants tied specifically to data center energy demand could increase between 19 and 29 percent over the next decade. This marks a significant reversal of progress—the power sector had been reducing emissions for several years before data center demand reversed that trend. The increase occurs because new electricity capacity to meet data center demand would predominantly come from fossil fuel sources under current policy.

Why are renewable energy projects facing delays if they're economically competitive?

Renewable projects face delays due to policy uncertainty and regulatory barriers rather than economic factors. An Interior Department policy mandating review of all wind and solar projects on federal lands has created a bottleneck of 22 gigawatts of capacity awaiting approval. Additionally, policy uncertainty about the future of tax credits, federal incentives, and regulatory support makes investors hesitant to commit capital to renewable projects, even when they're economically attractive.

What would restoring renewable energy tax credits actually accomplish?

Restoring wind and solar tax credits would cut data center-related CO2 emissions by more than 30 percent over the next decade while also potentially lowering wholesale electricity costs by approximately 4 percent by 2050. These credits reduce the upfront capital requirements for renewable projects, making them more economically attractive and accelerating deployment. The lower electricity costs result from renewable generation having zero fuel costs once deployed.

Why aren't major tech companies pushing harder for renewable energy policies?

Major tech companies have largely remained silent on federal renewable energy policy despite their massive electricity consumption and stated climate commitments. This reflects several factors: reluctance to take controversial political positions, uncertainty about their policy influence on energy matters, and a hope that market forces might eventually force renewable deployment without requiring explicit advocacy. However, this creates a strategic gap since these companies have significant economic leverage to influence energy policy toward renewables.

Could AI efficiency improvements solve the electricity demand problem?

Improvement in AI model efficiency could slow the rate of electricity demand growth but would not reverse the overall trend toward higher consumption. Even with dramatic efficiency improvements, the sheer number of AI inference queries and new applications would continue to drive total electricity consumption upward. Efficiency improvements are valuable as they buy time for policy to catch up, but they don't eliminate the need for policy change.

What role do regional electricity grids play in addressing data center demand?

Regional electricity grids have different characteristics, regulatory frameworks, and renewable resource availability. Texas's grid (ERCOT) has deployed significant wind capacity. The Northeast operates with a diverse mix of sources. The Southwest has abundant solar resources. Where data centers locate matters significantly for their carbon footprint, and regional grids offer different opportunities for renewable deployment and policy approaches.

How long does it take to build new natural gas plants compared to renewable capacity?

New natural gas power plant construction typically takes five to seven years from initial planning through operation. Renewable generation can be deployed much faster, with individual wind or solar installations potentially operational within 1-3 years. This speed advantage makes renewables more attractive for meeting rapidly growing electricity demand from data centers, even setting aside climate considerations.

What is the relationship between electricity pricing and renewable energy policy?

Renewable energy policies create a short-term cost increase through infrastructure investment but drive long-term cost reduction through zero-fuel-cost generation. While renewable policies may result in slight electricity price increases over the next decade as new capacity is built, modeling suggests that by 2050, renewable-focused policies would lead to approximately 4 percent lower wholesale electricity costs compared to fossil fuel-based approaches.

How accurate are projections of data center electricity demand given that some projects get cancelled?

Projections of data center electricity demand likely contain significant overcounting because companies submit proposals to multiple utilities simultaneously to shop for the best rates. The UCS analysis attempted to account for this by assuming only half of publicly announced projects would actually be built. Even with conservative assumptions, the projected electricity demand growth remains substantial and unprecedented in scale.

Thanks for reading. The data is clear, the solutions are available, and the decision is entirely ours.

Key Takeaways

- Data centers will drive over 50% of projected US electricity demand growth through 2050, fundamentally reshaping grid requirements and energy infrastructure

- Without policy intervention, CO2 emissions from power plants could increase 19-29% over the next decade specifically from data center energy needs, reversing years of climate progress

- Restoring renewable energy tax credits could cut data center-related emissions by 30%+ while potentially lowering long-term electricity costs, making clean energy economically optimal

- Federal policy is actively blocking renewable deployment, with 22 gigawatts of projects stuck in regulatory bottlenecks despite strong economic fundamentals and market demand

- Major tech companies have not adequately advocated for renewable energy policies despite their massive electricity consumption and stated climate commitments, representing a missed opportunity for industry-wide impact

Related Articles

- Microsoft's Community-First Data Centers: Who Really Pays for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- Trump and Governors Push Tech Giants to Fund Power Plants for AI [2025]

- Amazon's Bacterial Copper Mining Deal: What It Means for Data Centers [2025]

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- UK Electric Car Campaign: 5 Critical Roadblocks the Government Ignores [2025]

- How Chinese EV Batteries Conquered the World [2025]

![AI Data Centers & Carbon Emissions: Why Policy Matters Now [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-data-centers-carbon-emissions-why-policy-matters-now-2025/image-1-1768992196174.jpg)