The Unexpected Marketing Machine Behind Games Done Quick

There's a particular kind of magic that happens when you put a talented speedrunner in front of thousands of live viewers and ask them to break your game as creatively as possible. For indie developers, it's become something between a blessing and a controlled chaos scenario.

Games Done Quick, the biannual speedrunning charity event, has grown from a niche community thing into a full-blown cultural moment. The event currently running right now raises millions for organizations like the Prevent Cancer Foundation and Doctors Without Borders. But if you're an indie developer watching your game get demolished on stream by someone who's played it for 200 hours and found glitches you didn't know existed, the real payoff isn't just the charitable impact. It's the hundreds of thousands of eyeballs suddenly aware that your game exists.

The numbers tell a story. A GDQ feature can translate into a measurable spike in sales, wishlist additions, and community engagement. But what's fascinating is how this differs from traditional game marketing. There's no paid sponsorship angle here. No corporate tie-in. Just developers whose games impressed the GDQ selection committee enough to make the cut, paired with speedrunners who've spent months optimizing every frame and sequence skip.

The speedrunning community itself has exploded in the past five years. What started as scattered speed-running communities on forums evolved into Twitch, where speedrunning became appointment viewing. GDQ events now draw audiences in the 50,000 to 200,000 concurrent viewer range, depending on which event and which games are being run. That's legitimate primetime television numbers.

For indie games specifically, this exposure is transformative. Most indie titles launch with minimal marketing budgets. A small team might spend months crafting something special, only to watch it get buried in the digital noise of Steam, Epic, and other storefronts. Getting featured at GDQ bypasses all that noise. It's an earned spotlight, not a bought one.

But here's the thing that makes this genuinely interesting: the relationship between speedrunning and game design is more symbiotic than most people realize. Speedrunners don't just break games. They reveal things about how games actually work. They expose design decisions, intentional speedrun-friendly mechanics, and sometimes accidental glitches that become features. And developers are paying attention.

Real Developer Stories: The GDQ Boost in Action

Ceroro developed Bat to the Heavens, a 2D platformer with a concept that sounds impossible on paper: the main character can't jump, so she has to use a bat as a tool to ascend vertically. It's her first official game, released in 2024. The game had been doing reasonably well post-launch, with steady sales and a small but engaged community.

Then Awesome Games Done Quick 2026 happened.

"It was extremely exciting," Ceroro said about the experience of watching her game speedrun live in front of thousands of people. "Right after the AGDQ run, there was a large burst in sales and wishlists I haven't seen since I initially released the game." That's the kind of impact that changes things for a small developer. For context, launch momentum is everything in indie game publishing. Second winds are rare. Getting a second spike in sales months after release can mean the difference between breaking even on development costs and actually making profit.

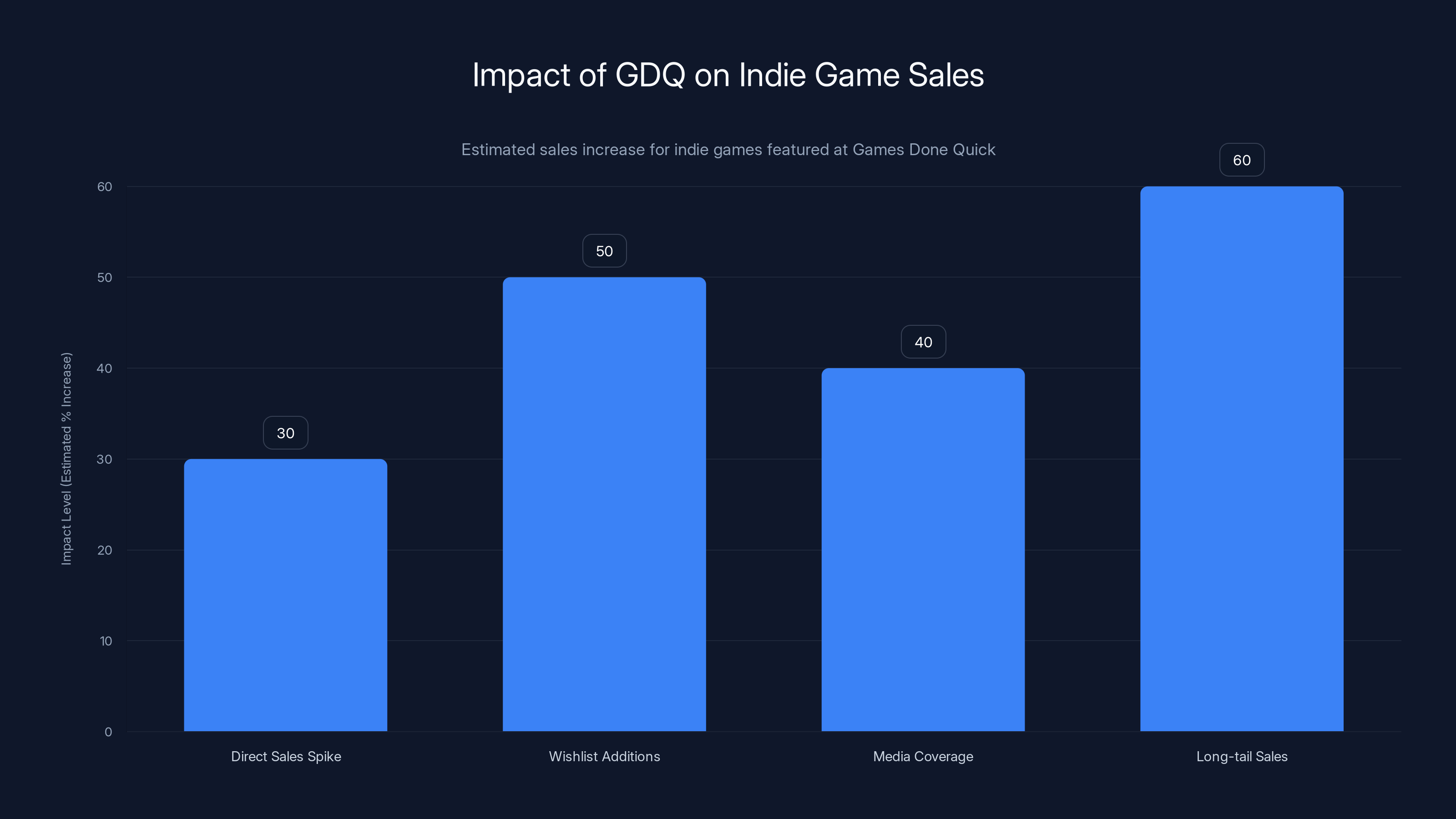

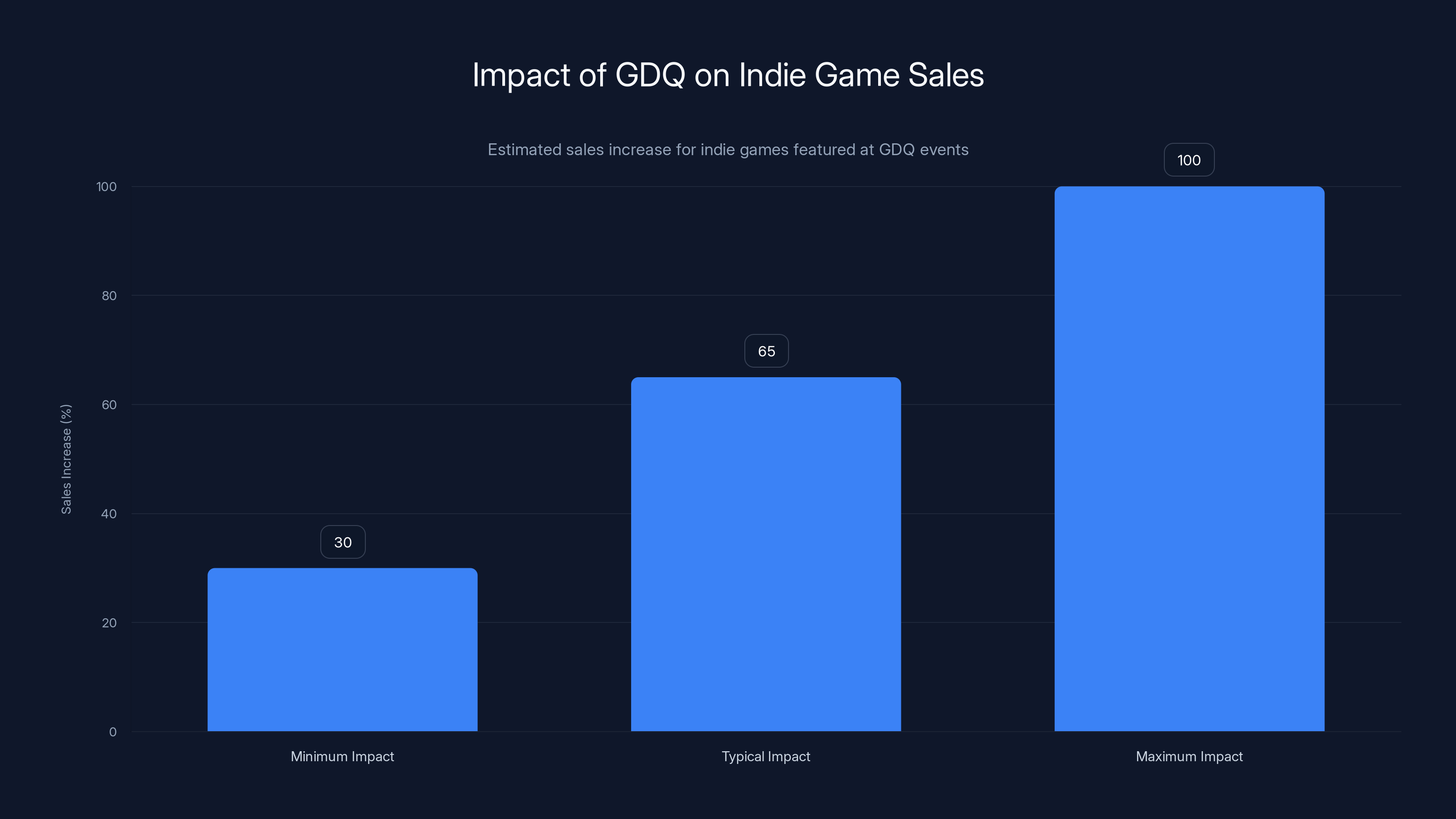

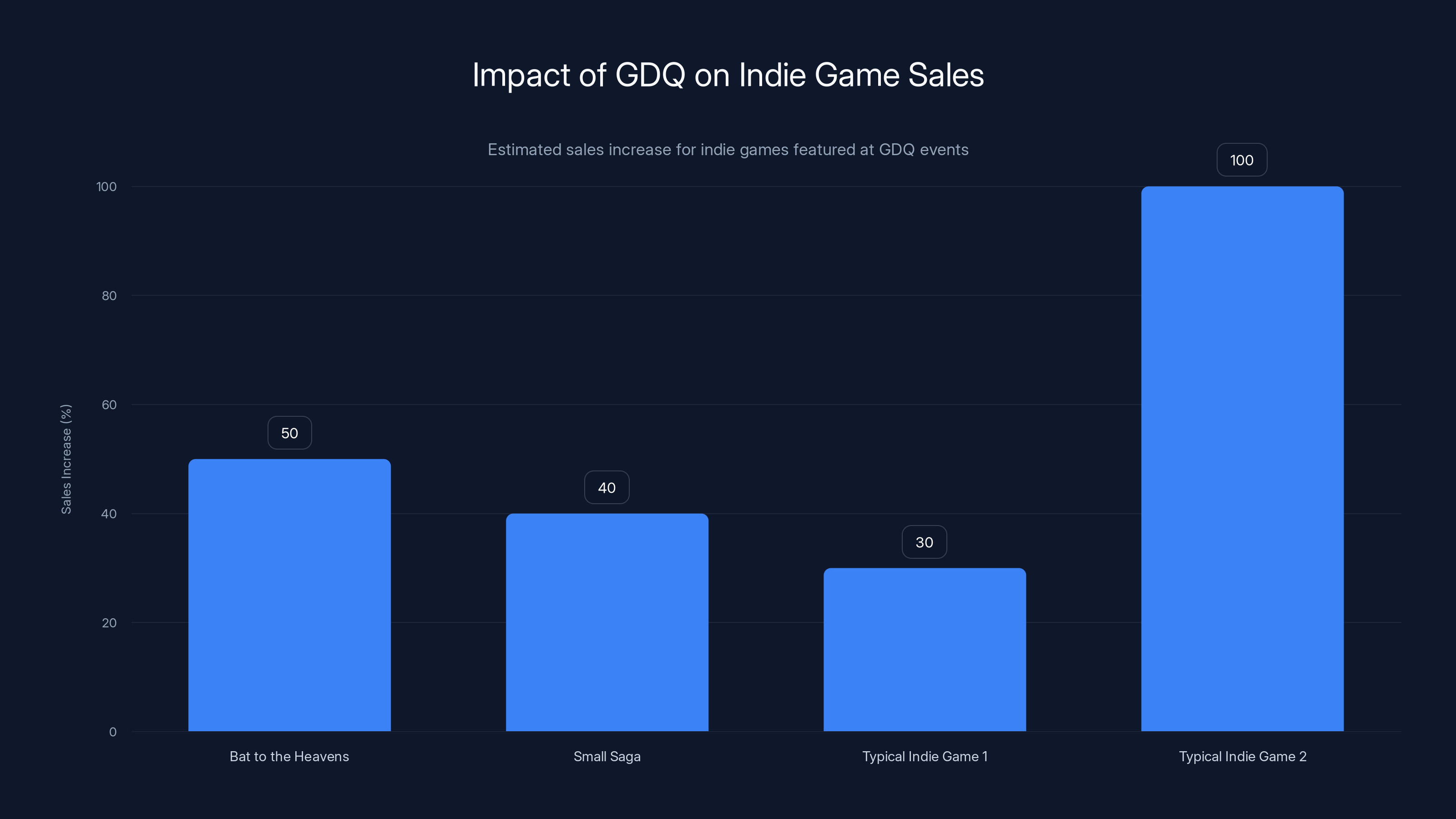

The specific numbers vary by game, but developers consistently report significant increases. For some titles, it's a 30% to 50% bump in sales over the following week. For others, it's closer to 100% or more. The variability depends on how many viewers were watching that particular run, whether the game was already on players' wishlists, and pure luck in terms of content creators picking it up afterward.

Darya Noghani, solo developer of Small Saga (a turn-based RPG about a mouse trying to kill god, which is exactly as creative as it sounds), experienced the GDQ effect firsthand. "A number of streamers played the game on Twitch, several commenters recommended the game on platforms like Bluesky, and there was a nice uptick in sales," they said. But the impact extended beyond the immediate post-run period. Getting featured on GDQ added legitimacy. The game appeared in Twitch categories. Content creators who'd never heard of Small Saga picked it up, assuming if GDQ featured it, it must be worth their time.

This is the secondary effect that often gets overlooked. The direct sales bump from GDQ viewers is real, but the downstream visibility—streamers picking it up, recommendation chains on social media, algorithmic boosts on storefronts—sometimes exceeds the initial burst. It's like dominoes where GDQ provides the first push, and the rest of the indie gaming ecosystem does the work.

Other smaller titles have experienced similar trajectories. Games like Bread Simulator got their moment on the GDQ stage. So did obscure platformers, experimental puzzle games, and niche RPGs that would've remained invisible without that exposure. The selection process for GDQ submissions is rigorous enough that everything featured has some quality bar. But there are thousands of decent indie games. Only a handful get the GDQ slot.

For developers, getting that email saying your game made the cut is life-changing. It's validation from peers and the community. It's a signal that your work mattered enough to be worth 30 minutes to an hour of live broadcast time.

Indie games featured at GDQ can see a direct sales spike of 30-100% and significant long-tail sales impact, with increased media coverage and wishlist additions. (Estimated data)

The Hidden Costs: When Your Game Gets Broken

But here's where it gets complicated. Speedrunning isn't about playing a game the way the developer intended. It's about exploiting every possible mechanic, sequence break, and glitch to finish as fast as possible. For a developer watching the stream, this can be equal parts thrilling and terrifying.

"You're in a state of apprehension," Noghani explained. The fear is legitimate. If a runner happens to find a game-breaking glitch that completely crashes the run, that's your game failing in front of hundreds of thousands of people. The footage is permanent. It gets clipped and shared. "Runners are pushing the game to break in particular ways, and you know this is adjacent to the game just crashing and ruining the run."

Small Saga's run at GDQ was relatively glitch-free, which Noghani took as "a win." That probably understates the relief. A smooth speedrun showcases the game in a positive light. A crashed run showcases your game's bugs, which is the opposite of what you want during your big moment.

There's also the concern about speedruns trivializing the game design. Speedrunners might skip entire sections that the developer spent weeks crafting. They'll exploit unintuitive glitches that completely undermine the intended experience. To someone seeing the speedrun without context, the game might look trivial, broken, or poorly designed.

Ceroro's perspective on this is interesting. She recognized that speedrunning inherently shows only a compressed, exploit-heavy version of the game. But she also didn't see that as a dealbreaker. "The speedrun for Bat to the Heavens went by too fast to actually get a good understanding of everything or how the game actually feels, so it'll be a shock to new players." In other words, the speedrun isn't a spoiler. It's a different experience entirely. Someone watching a speedrun for 30 minutes might think the game looks simple. Playing it legitimately for 4 to 6 hours reveals the actual complexity.

Some exploits are actually features. "Exploits and glitches are something that taps into the nature of game design," Ceroro noted. The extreme movement techniques used in the Bat to the Heavens run were "pretty much within bounds of the intended design." She'd thought about speedrunning when developing the game. She knew players would find ways to bypass certain challenges. She built the game with that in mind.

That's the ideal scenario: a developer who understands the speedrunning community, builds speedrun-friendly mechanics intentionally, and can watch the run knowing they're seeing a creative expression of their game design rather than a break of it. Not every developer approaches it that way, though. Some are genuinely stressed watching their game get exploited.

Indie games featured at GDQ can see sales spikes ranging from 30% to 100%, with significant financial benefits. (Estimated data)

The Community Effect: Why GDQ Matters Beyond the Metrics

But the actual numbers might be secondary to something less quantifiable. Games Done Quick has built something remarkable in terms of community culture. It's not just a speedrunning event. It's evolved into a celebration of gaming, inclusion, and humor. The chat interactions alone are worth study. You get genuine crowd reactions, community in-jokes that have persisted for over a decade, and real moments of human connection in an online space that's often fragmented and toxic.

Xalavier Nelson Jr., creative director at Strange Scaffold (the studio behind Games like Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator, which has been featured at GDQ multiple times), put it perfectly: "In the development community, it's a giant moment. I got about as many congratulations for appearing on Games Done Quick as I have for getting major reviews or awards."

That's striking. A GDQ feature registers as a major achievement alongside traditional markers of success like critical acclaim or industry recognition. There's something about being part of that community moment that resonates differently than standard marketing.

GDQ has been intentional about building that culture. The organization has implemented top-down approaches to diversity and inclusion over the years. They host smaller events specifically designed to highlight speedrunners from marginalized backgrounds. They've worked to make the community welcoming to queer participants. You'll see streamers casually saying "trans rights" on GDQ broadcasts and getting the same enthusiastic audience response they would for any other celebration or inside joke.

Compare that to many gaming communities, which range from indifferent to actively hostile toward inclusion initiatives. GDQ's approach has created a genuinely different vibe. It feels intentional, authentic, and built from the community up rather than imposed from above.

For indie developers, this matters. When your game gets featured at GDQ, you're not just getting marketing exposure. You're getting associated with a community that cares about gaming as a craft and as a social experience. That association matters. Players who find your game through GDQ already have some baseline expectations about quality and heart.

Noghani specifically called this out: "Because GDQ is genuinely well-loved by both players and developers, not just for its charitable causes, but because of the efforts they've taken to cultivate an uplifting community."

The Selection Process: How Your Game Gets Chosen

Not every indie game gets the GDQ treatment. The selection committee reviews hundreds of submissions for each event. Games need to meet certain criteria: they need to be speedrun-able in a reasonable timeframe, interesting enough to watch, and hopefully novel or creative in some way. The committee looks for games that will entertain viewers, not just showcase technical speedrunning skill.

This is partly why GDQ has become such an effective platform for indie games. The committee isn't just picking AAA titles or already-famous speedrunning games. They're actively searching for hidden gems. They want to introduce viewers to games they've never heard of. Getting selected means your game passed a quality bar set by people who care deeply about speedrunning and game design.

The submission process itself is competitive. GDQ events receive thousands of submissions. Only a few hundred games get reviewed in detail. Fewer still make the final schedule. For an indie developer, success in the selection process requires a few things: a game that speedrunners actually want to run, a game that's interesting to watch, and often, existing speedrunning community interest.

Many games that appear at GDQ already have speedrunning communities, sometimes months or years before the event. Speedrunners have been running these games on their own streams, optimizing routes, finding glitches. By the time a game gets selected for GDQ, there might already be leaderboards, established techniques, and people who know the game intimately.

This creates a feedback loop. A small speedrunning community builds around a game. One of those runners submits it to GDQ. The game gets accepted. Suddenly the community grows 50-fold. New runners start optimizing. New leaderboards get recorded. The speedrunning scene around that game transforms.

For developers, understanding this dynamic helps. If you're hoping your indie game might get GDQ exposure, having a speedrunning community before the event helps significantly. Not because GDQ favors already-popular games, but because the existence of a speedrunning community signals that your game is actually worth speedrunning.

A GDQ feature can lead to 5,000-15,000 wishlist additions, with 20%-40% converting to purchases, generating

Financial Impact: Converting Viewers to Revenue

Let's talk actual money. How much does a GDQ feature actually impact a game's bottom line?

The conversion varies wildly depending on the game, the runner, the specific audience watching that run, and the current state of the game's marketing cycle. But some rough frameworks help:

A 30-minute run in front of 100,000 concurrent viewers might translate to somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 people adding the game to their wishlist. Of those, maybe 20% to 40% will eventually purchase. If the game costs

But those numbers are rough estimates. Some developers report much higher conversion rates. Others report lower ones. The variance depends on how many viewers were already aware of the game, how compelling the speedrun was, and how good the call-to-action is from the community.

The real impact might actually be in the long tail. Yes, there's a spike during and immediately after the run. But the sustained visibility from that appearance can drive sales for months afterward. GDQ footage gets clipped and shared. Content creators pick up the game. It appears in recommendation algorithms. The cumulative effect might be

For small indie teams, that's transformative. That kind of revenue can fund the next project, expand the team, or justify continued work on the original game through additional updates and content.

Moreover, there's value in the media coverage that follows. Gaming outlets write about interesting GDQ runs. Streamers on platforms like YouTube and Twitch react to the footage. The game gets mentioned in Reddit threads, Discord communities, and gaming forums. All of that generates additional visibility that didn't exist before.

The challenge is that this effect is hardest to measure. A sales spike is obvious. Attributing a viral TikTok video about your game to the GDQ feature is harder. But developers know something shifted. The game trends differently post-GDQ. It has momentum it didn't have before.

Why AAA Games Can't Replicate This

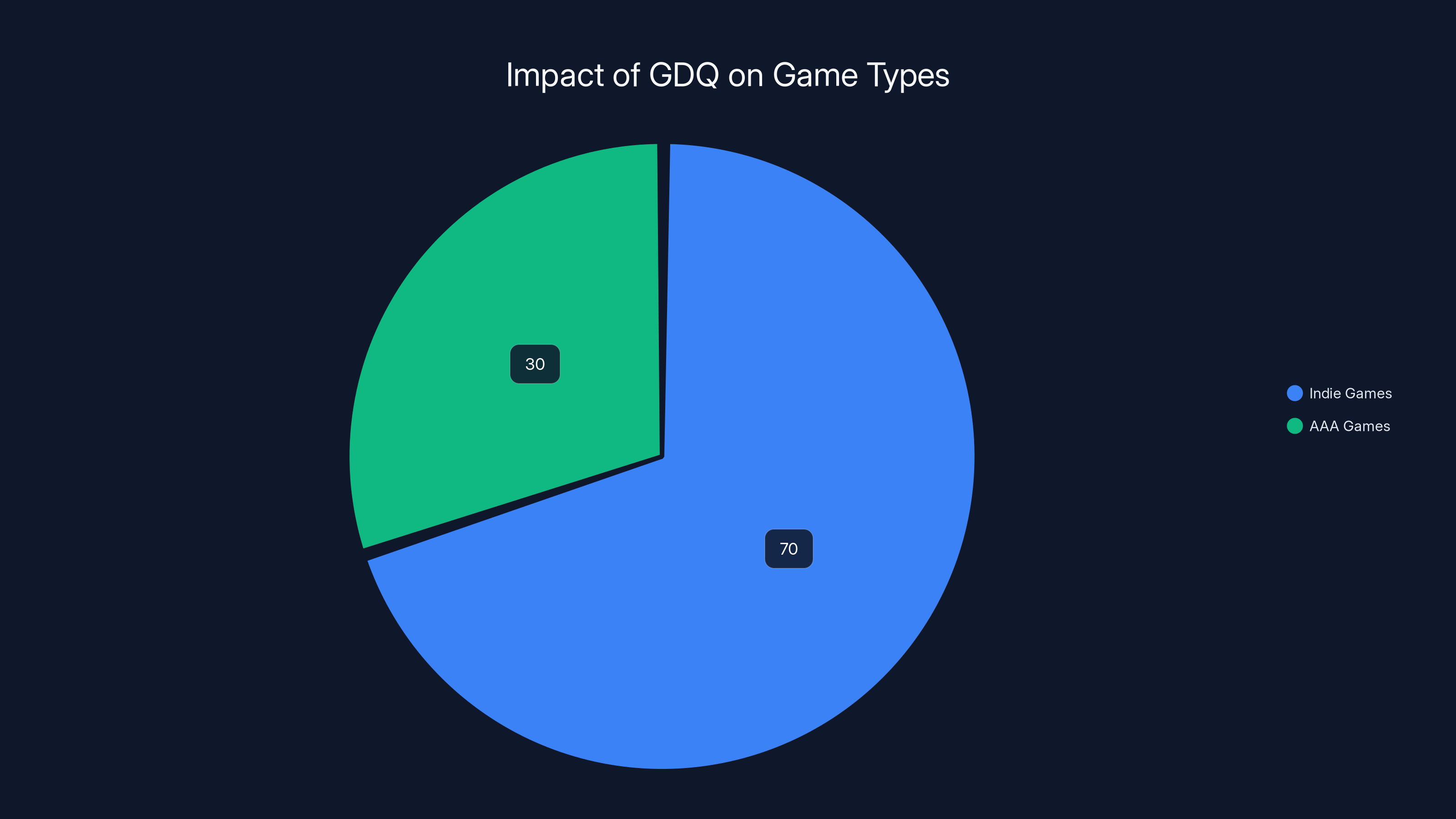

Here's something that's often overlooked: games from major studios don't get the same kind of boost from GDQ that indie games do. A speedrun of a AAA title might be entertaining, but it doesn't generate the same sense of discovery. Everyone already knows about the latest Zelda or Elden Ring. A GDQ feature on those games is cool, but it's not revealing anything new.

Indie games benefit from that discovery element. The speedrun is often people's first exposure to a game they've never heard of. The novelty, combined with the skillful speedrunning, creates a compelling package. It's a showcase event in a way that a AAA speedrun isn't.

This dynamic has actually made GDQ more valuable to the indie dev community over time. As the event has grown in prestige, the selection committee has become more conscious of giving indie games a platform. They know that's where the impact is most meaningful.

It's also worth noting that AAA studios don't need GDQ the way indie developers do. They have marketing budgets in the millions. They can buy ad space, influence media coverage, and generate hype through traditional channels. Indie developers are working with a fraction of that. GDQ provides what they can't buy.

Games featured at GDQ events can experience significant sales increases, ranging from 30% to over 100%, providing a crucial boost for indie developers. Estimated data.

The Speedrunning Community: What They Actually Contribute

The speedrunners themselves deserve credit that they often don't get. A good speedrunner doesn't just play a game fast. They entertain. They narrate their experience. They react to moments of tension. They build a narrative around their run, even if the run itself is only 30 minutes of compressed gameplay.

Good speedrunners understand pacing. They know when to explain a trick, when to let the silence speak, when to celebrate a near-miss. They're performers, not just skilled players. The best runs at GDQ feel like collaborative performances between the runner and the community.

For developers watching a speedrunner take their game apart, there's often genuine appreciation for the skill involved. These people have invested hundreds of hours learning your game. They've found strategies you didn't anticipate. They've pushed your game to its limits. The respect goes both ways.

Speedrunners also tend to be genuinely invested in the games they run. They're not just looking for quick dopamine hits. They care about the craft of speedrunning, the community, and the games themselves. This shows when they talk about games post-GDQ. A runner who speedran your indie game might stream it again later, play the DLC, or recommend it to their audience. That sustained engagement is incredibly valuable.

The speedrunning community has also become more sophisticated about game development over the years. Runners collaborate with developers. They offer feedback on games. Some have become involved in game development themselves. The line between speedrunning community and game dev community has blurred significantly.

Technical Preparation: What Developers Need to Do

If you're an indie developer hoping to get GDQ exposure, or if you've been selected and now have to prepare, there are practical steps to take.

First, make sure your game runs stably. Test it extensively with the speedrunner who's going to be featured. GDQ events happen on specific hardware setups. Make sure your game doesn't have random crashes or physics glitches that could end a run unexpectedly. This seems obvious, but it's worth emphasizing because a crashed run is visible failure on a massive stage.

Second, communicate with the speedrunner. Understand their intended route. Know which glitches they'll be using and which ones are unintended. If you have concerns about something, raise them early. Most speedrunners are collaborative and will work with developers to ensure a smooth run that showcases the game well.

Third, consider patching known issues if you discover them during preparation. You don't want a run halted by a bug you could've fixed. That said, don't make changes that break the speedrunning strategies. This is a balance.

Fourth, prepare for the aftermath. Have server capacity for increased traffic to your Steam page, your Discord, or your official website. Prepare communication. Write a tweet ahead of time thanking the speedrunner. Plan any sales or discounts you want to run post-GDQ. Have enough inventory or digital copies available if applicable.

Fifth, engage with the community afterward. Reply to comments, answer questions about your game, interact with people who discovered it through GDQ. That engagement turns one-time viewers into community members.

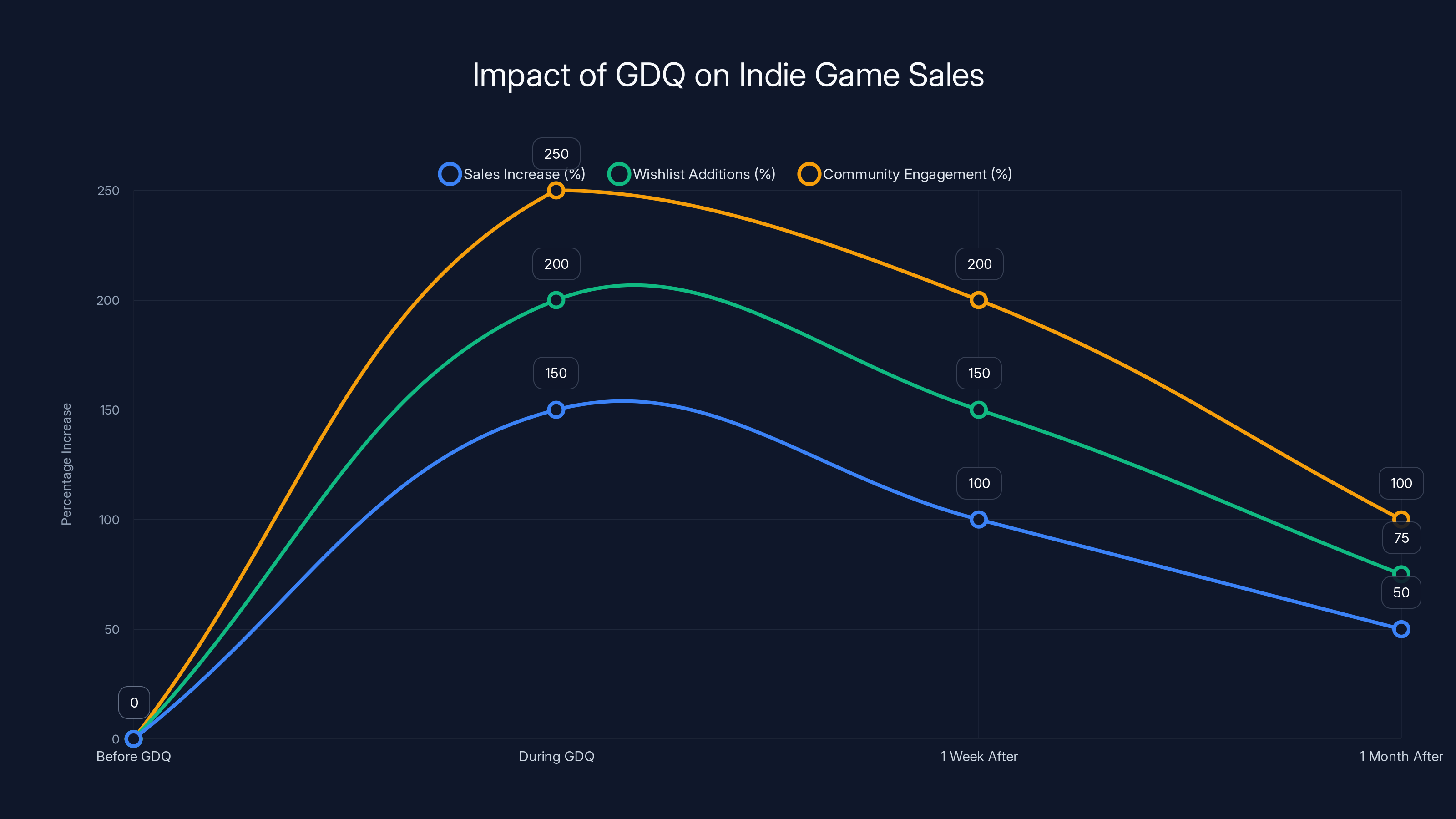

Estimated data shows a significant spike in sales, wishlist additions, and community engagement for indie games featured at GDQ, with effects lasting up to a month after the event.

The Psychological Impact: Achievement and Validation

Beyond the financial and marketing considerations, there's something psychological about getting your game featured at GDQ. It's validation. It's recognition from a community you respect.

Indie game development is grueling. You pour thousands of hours into something with no guarantee of success. You stress about funding, about whether anyone will care, about whether the game will even be finished. Getting to launch is already an achievement. Getting the game to be commercially successful is luck combined with skill.

But getting selected for GDQ is different. That's peer recognition. That's the gaming community saying, "This game is worth celebrating. This is interesting enough for our event."

Noghani captured this: "It's been exciting because GDQ is genuinely well-loved by both players and developers." The emphasis on genuine is important. This isn't sponsorship-driven recognition. This is a community saying they value your work.

For developers early in their careers, this matters enormously. A GDQ feature can become a centerpiece of their professional narrative. When they pitch their next game, they can say, "My last game was featured at Games Done Quick." That carries weight in indie dev circles.

It also creates momentum psychologically. The validation gives confidence to move forward. The financial success helps with practical concerns. Combined, it's often the difference between a developer continuing to make games and deciding that game development wasn't viable.

The Broader Ecosystem: How GDQ Influences Game Development

Games Done Quick's impact extends beyond individual games and developers. The event influences how games get designed. Knowing that speedrunning communities might form around your game, developers increasingly think about speedrun-friendly design. They consider which glitches are acceptable, which mechanics might be exploited, how the game would look if someone played it at maximum efficiency.

This has actually improved game design in some ways. It forces developers to think critically about game mechanics and progression. It encourages tighter, more intentional design. It also creates opportunities for games to have multiple play modes or difficulty options that appeal to different audiences.

Speedrunning has become a lens through which game design is evaluated. Gaming conferences now have speedrunning panels. Game jams often include speedrunning categories. The speedrunning community has become part of the broader gaming discourse.

GDQ specifically has helped legitimize this. By providing a major platform for speedrunning, the event has signaled to the industry that this matters. Game developers, publishers, and players now all recognize speedrunning as a valid way to engage with games.

There's also the educational component. Aspiring game developers watch GDQ and see how games are structured, how players interact with systems, how small design decisions cascade into major emergent behaviors. It's a free masterclass in game design, broadcast to hundreds of thousands of people.

GDQ events have a significantly higher impact on indie games (70%) compared to AAA games (30%), highlighting the platform's role in indie game discovery. Estimated data.

Growing Pains: The Challenge of Scaling While Staying True

As GDQ has grown, there's been inevitable tension. With more viewers comes more commercial interest. More sponsorships, more corporate involvement, more professionalization. Some community members worry that the event is becoming less grassroots, more polished, potentially losing some of its charm.

There's also the challenge of maintaining quality and community focus while handling exponential growth. Early GDQ events were run more or less by volunteers. Modern events are complex productions with significant logistics. That professionalization is necessary for safety, accessibility, and managing such large audiences. But it changes the vibe.

For developers and speedrunners, the challenge is staying involved as the event grows. How do you maintain that sense of community when you're one of thousands? How do you ensure that indie developers still have a spotlight when there's increasingly corporate interest in the event?

GDQ's approach has been to remain selective. They haven't overexpanded the event schedule or diluted the quality bar for games that get featured. They've kept the community culture intentional. They've hired staff and volunteers who understand the community and want to preserve what makes GDQ special.

It seems to be working. The community remains engaged. The event continues to attract top-tier speedrunners and interesting games. The charity components continue to raise substantial funds. But it's something the event will need to keep managing as it evolves.

The Future: Will GDQ Remain the Indie Game Showcase?

There are interesting questions about what comes next for GDQ and indie games at speedrunning events. Will the event continue to prioritize indie games, or will there be pressure toward bigger, flashier AAA titles? Will the financial success of indie developers getting featured at GDQ create saturation, making future GDQ boosts less impactful? Will other events create similar opportunities, fragmenting the speedrunning audience?

Historically, GDQ has remained true to its mission of selecting interesting games over commercially obvious ones. That suggests they'll likely continue giving indie games substantial airtime. But the landscape is changing. More events are launching. More platforms are hosting speedrunning content. More developers are aware of speedrunning's marketing potential.

For indie developers specifically, the window of relative novelty might be closing. Early indie games that appeared on GDQ benefited from genuine discovery. As GDQ becomes more established and more indie games appear, the novelty factor diminishes. Future indie games at GDQ might not see the same kind of first-mover advantage that early featured titles did.

But the community value remains. The validation remains. The exposure still matters. It might not be the life-changing discovery moment it was five years ago, but it's still significant.

Practical Advice for Indie Developers

If you're an indie developer hoping to get GDQ exposure, here's what actually matters:

First, make a game that's actually good and worth speedrunning. This should be obvious, but it's foundational. You can't game the system. The committee will see through a submission designed purely to catch speedrunners' attention. Make something you're genuinely proud of.

Second, consider speedrunning in your game design. Not obsessively, but think about it. What happens if someone skips all the cutscenes? What happens if they find a sequence break? Can your game handle it? These considerations will make your game more robust anyway.

Third, engage with the speedrunning community. If your game lends itself to speedrunning, let runners know about it. Be part of early speedrunning communities around your game. Support runners. This builds genuine interest that translates to GDQ selection interest.

Fourth, submit to GDQ. You don't get selected if you don't apply. The submission process is straightforward. Being thoughtful about why your game is interesting to speedrun increases your chances.

Fifth, don't fixate on GDQ as your success metric. It's one possible opportunity, not a guarantee. Build your game because you want to make it. If GDQ happens, great. If not, you've still made something. Focus on making the best game possible.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Moment Matters

Games Done Quick's rise to prominence reflects something broader about gaming culture. Speedrunning has moved from niche hobby to legitimate form of game engagement and performance art. Indie games have moved from afterthoughts to the core of innovation in gaming. Communities have learned how to organize, celebrate, and champion work they care about without corporate interference.

GDQ exists at the intersection of all these trends. It's a celebration of speedrunning, a platform for indie developers, and a community-driven event in an increasingly corporate gaming landscape. That combination is rare and valuable.

For indie developers, GDQ represents the possibility that you can make something in a garage with a small team, and if it's good enough and interesting enough, it can reach millions of people. That's not guaranteed. It requires luck and timing and the right kind of game. But it's possible. That possibility matters for the entire indie game ecosystem.

It also demonstrates that marketing doesn't have to be purely transactional. You don't have to buy your way to visibility. You can earn it through quality and community engagement and luck. GDQ proves this is possible at a scale that influences careers and changes lives.

That's why developers care so deeply about GDQ. It's not just about the sales bump, though that matters. It's about recognition, validation, and proof that the work matters.

Looking Ahead: The Evolution Continues

Games Done Quick will likely continue to evolve. New platforms and technologies will change how speedrunning is experienced. New games will be discovered through the event. New developers will launch careers off the back of a GDQ appearance. The community will grow, change, adapt, and hopefully maintain what makes the event special.

For indie developers watching right now, the key insight is that opportunities like this exist. They're not guaranteed, and they're not for every game. But if you make something interesting and engage with communities that care about what you've built, good things can happen. A game featured at GDQ isn't a lottery. It's a reward for making something worth celebrating.

The speedrunning community has shown what's possible when people genuinely care about gaming and build communities around that care. GDQ has proven that those communities can reach massive scale while maintaining authenticity. Indie developers have proven that small teams with great ideas can compete for attention and recognition.

Together, they've created something that didn't exist ten years ago: a mainstream celebration of speedrunning, indie games, and the communities that love them. That's remarkable. And it's still growing.

FAQ

What is Games Done Quick?

Games Done Quick is a biannual charity speedrunning event that raises millions of dollars for organizations like the Prevent Cancer Foundation and Doctors Without Borders. Speedrunners compete to complete games as quickly as possible, employing glitches, sequence breaks, and optimized techniques to minimize playtime. The event streams to hundreds of thousands of concurrent viewers on Twitch and has become a major cultural moment in gaming.

How does a game get selected for Games Done Quick?

The GDQ selection committee reviews hundreds of submissions for each event and chooses games based on several criteria: speedrun-ability within a reasonable timeframe, entertainment value for viewers, novelty, and existing speedrunning community interest. Games need to pass a quality bar and be interesting to watch. Having an existing speedrunning community around your game significantly increases the likelihood of selection, as does making the submission thoughtful and compelling.

What are the benefits of getting your indie game featured at Games Done Quick?

Featuring an indie game at GDQ generates multiple benefits including direct sales spikes (often 30-100% increases in a single week), increased wishlist additions, sustained visibility from media coverage and content creator reactions, community validation, and long-tail sales impact over following months. The exposure reaches hundreds of thousands of players who might never have discovered the game otherwise, and the association with the well-respected GDQ community adds credibility to smaller indie titles.

How much money can an indie game make from a Games Done Quick appearance?

The financial impact varies significantly based on viewer count, game price, and conversion rates, but estimates suggest a 30-minute run in front of 100,000 concurrent viewers could generate between

What happens to indie developers after their game gets featured at Games Done Quick?

Indie developers typically experience immediate and sustained benefits including financial revenue that can fund future projects or expand their team, increased media coverage and streaming interest, new community members joining their Discord or social channels, and significant career validation. Many developers report that the GDQ feature becomes a centerpiece of their professional narrative and provides momentum for future game pitches and projects. The psychological boost of community recognition often matters as much as the financial impact.

Does speedrunning break or spoil indie games?

While speedrunners exploit glitches and skip content, most developers view this positively as a creative expression of game design rather than a break. Many speedrunning techniques are within the bounds of intended design, and the compressed nature of a speedrun often doesn't spoil the actual game experience since viewers don't see how mechanics feel during normal gameplay. Developers strategically design games with speedrunning in mind, intentionally including speedrun-friendly mechanics that work both for speedrunners and traditional players.

How can indie developers prepare their game for a Games Done Quick appearance?

Key preparation steps include extensively testing the game with the speedrunner on the specific hardware GDQ uses, communicating closely with the runner about their intended route and any glitches they'll use, patching any critical bugs that could crash during the run, preparing server capacity and communication for increased visibility, engaging with community afterward, and potentially planning post-GDQ sales or discounts. Most importantly, developers should collaborate with the runner to understand their strategy and ensure a smooth run that showcases the game well.

Why is Games Done Quick more impactful for indie games than AAA games?

AAA games don't receive the same discovery boost from GDQ because audiences already know about them through existing marketing and media coverage. Indie games benefit from the novelty and discovery element of being exposed to hundreds of thousands of players for the first time. The sense of discovering something unknown makes the speedrun more compelling for viewers, and the impact on indie developers is more meaningful because they typically lack the marketing budgets of major studios. GDQ provides indie developers with exposure they couldn't buy.

Has Games Done Quick changed how indie games are designed?

Yes, GDQ's prominence has influenced indie game design significantly. Developers increasingly consider speedrunning in their design process, thinking about which glitches are acceptable and which mechanics might be exploited intentionally. This consideration has actually improved game design by encouraging tighter, more intentional mechanics and creating opportunities for multiple play modes. Speedrunning has become a lens through which game design is evaluated, with conferences, game jams, and the broader industry now recognizing speedrunning as a valid and important form of game engagement.

TL; DR

- Games Done Quick is a massive platform: The biannual charity speedrunning event reaches 50,000 to 200,000 concurrent viewers and has become a life-changing opportunity for indie developers.

- Direct financial impact is significant: Indie games featured at GDQ typically see 30-100% sales spikes, sometimes generating 120,000 in direct revenue from a single appearance, with sustained increases for months afterward.

- Community validation matters as much as money: Developers report that GDQ recognition carries equal weight to traditional success metrics like critical reviews, and the community support inspires continued game development.

- Speedrunning showcases, not spoils games: Speedruns don't ruin the game experience because they're compressed, exploit-heavy, and often within intended design bounds. Most players watching speedruns later discover entirely different gameplay.

- Preparation and community building are key: Games that already have speedrunning communities pre-GDQ are more likely to be selected, and developers who engage with speedrunners and communicate during preparation see the smoothest runs and best outcomes.

- The discovery element is irreplaceable: Unlike AAA games that audiences already know about, indie games benefit from genuine discovery through GDQ, making the exposure exponentially more impactful for small teams without traditional marketing budgets.

Key Takeaways

- Games Done Quick features generate 30-100% sales spikes for indie games, sometimes translating to 120,000+ in direct revenue from a single event

- The community validation from GDQ is valued equally to critical acclaim and awards by indie developers, providing psychological impact that sustains careers

- Speedrunning showcases don't spoil games because speedruns are compressed, exploit-heavy experiences fundamentally different from normal gameplay

- Games with existing speedrunning communities pre-GDQ are significantly more likely to be selected, making community engagement a practical strategy

- GDQ's intentional approach to diversity and inclusion has created a uniquely welcoming gaming community that benefits all participants beyond the event itself

- Indie games benefit from discovery-driven exposure at GDQ in ways AAA titles cannot, because audiences already know about major studio releases through traditional marketing

Related Articles

- How to Watch Awesome Games Done Quick 2026: Complete Guide [2025]

- 2025 Steam Awards Winners: Complete Breakdown [2025]

- Stardew Valley Nintendo Switch 2 Free Upgrade [2025]

- Larian Studios AI Policy: No Gen-AI Art or Writing for Baldur's Gate 3 [2025]

- Xbox Developer Direct 2026: Fable, Forza Horizon 6, and Beast of Reincarnation [2025]

- GTA 6 Delays & Game Announcements: Why Early Reveals Hurt [2025]

![How Games Done Quick Became a Game-Changer for Indie Developers [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-games-done-quick-became-a-game-changer-for-indie-develop/image-1-1768052155375.jpg)