The Founder Who Cracked Firefighting

Sunny Sethi doesn't fit the profile of someone who'd disrupt an industry that's barely changed since the 1960s. No firefighter background. No decades studying flames. Instead, he's got a Ph.D. in materials science, years developing carbon nanotubes, solar panels, semiconductors, and automotive adhesive systems. He's lived everywhere from Ohio to California. And he's driven by something most engineers overlook: his wife's anger.

In 2019, during evacuation warnings in Northern California, Sethi was traveling while his wife sat home alone with their three-year-old daughter. No family nearby. Potential evacuation order looming. When he returned, the conversation was blunt: "She was really mad at me. She's like, 'Dude, you need to fix this, otherwise you're not a real scientist.'"

That challenge led to HEN Technologies, a company that's quietly revolutionized firefighting through hardware-software convergence. The nozzles are just the headline. The real story is how one founder built an AI-powered data platform disguised as fire equipment.

Today, HEN's intelligent devices track water flow, pressure, location, weather, and timing data from active fire suppression. The company is building the infrastructure for predictive analytics in emergency response. By 2026, they're launching application layers with machine learning algorithms that could transform how fire departments allocate resources, prevent water shortages, and save lives.

This isn't a story about better nozzles. It's about how domain expertise, materials science, and relentless problem-solving can unlock opportunities in industries everyone assumes are mature.

The 60-Year Problem Nobody Solved

Fire suppression technology hasn't fundamentally changed since the 1960s. Your fire department's nozzles today work the same way they did in 1965. The basic physics hasn't evolved. Neither has the efficiency.

Traditional fire nozzles suffer from a critical weakness: they disperse water inefficiently. When water exits a standard nozzle, the stream breaks apart almost immediately. Wind pushes droplets. Turbulence scatters them. The pattern becomes unpredictable. In a head-on battle with a megafire, this matters enormously.

Consider what actually happens during wildfire suppression. A fire truck pulls up to defend a structure. The captain opens the nozzle. Water should hit the flames coherently, delivering maximum suppressive energy in a tight pattern. Instead, traditional nozzles send droplets everywhere. Some hit the fire. Some blow away on wind. Some penetrate the flames and cool them. But many just evaporate or miss entirely.

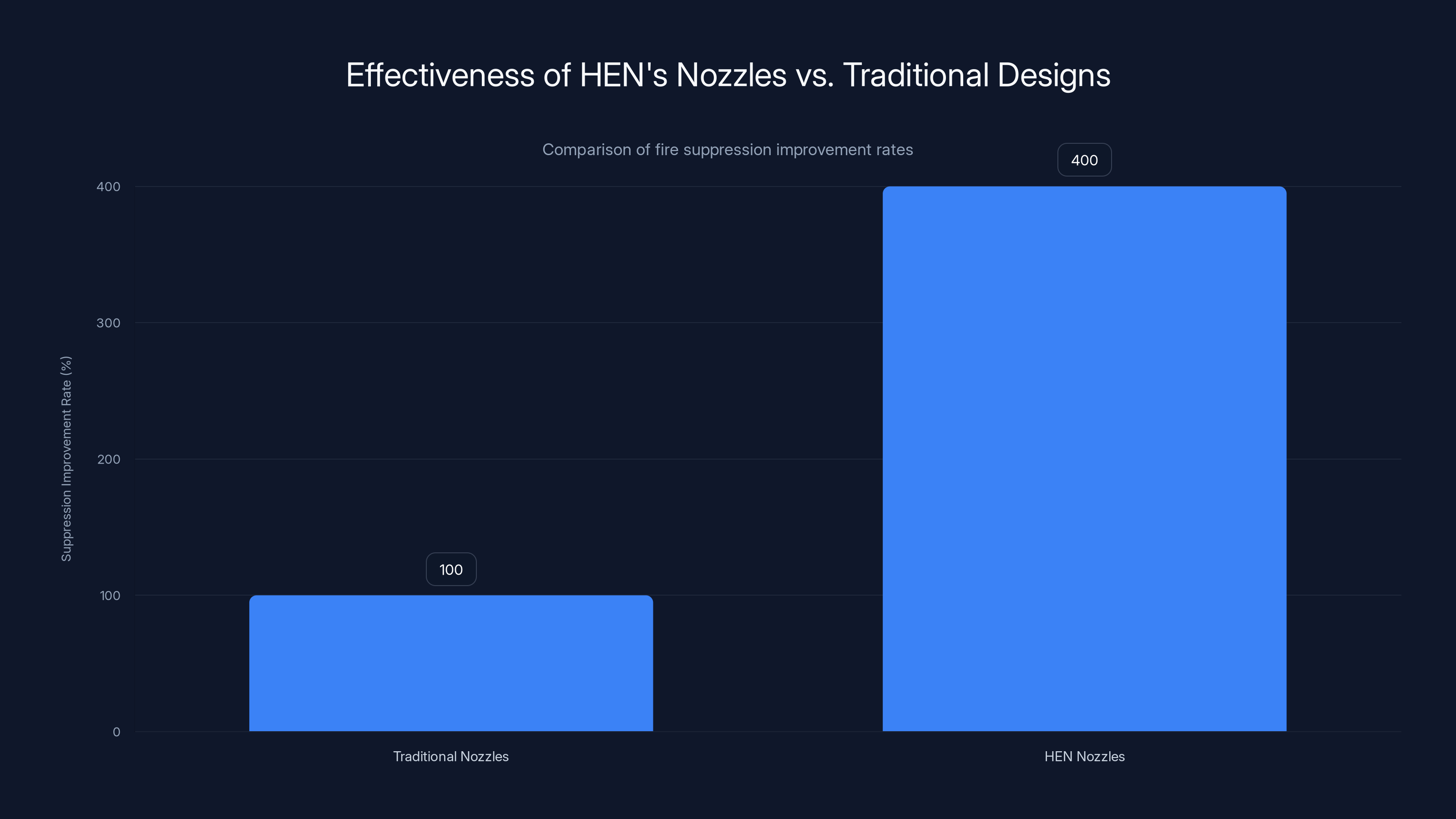

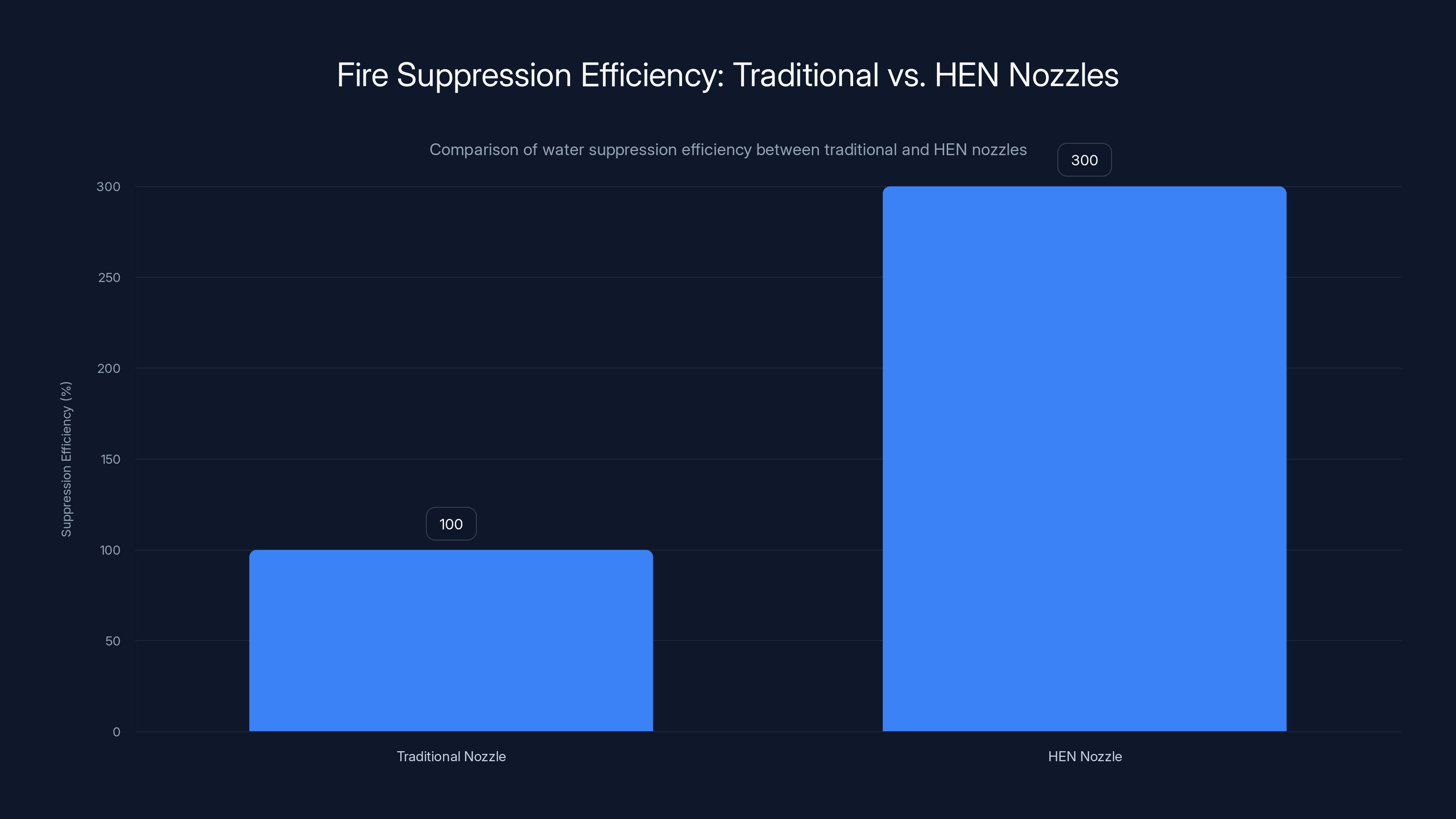

The math is brutal. A standard nozzle at the same flow rate as HEN's produces dispersed, unpredictable patterns. HEN's maintains coherence. The difference in suppression rates isn't marginal. It's a 300% improvement on paper, though real-world conditions vary.

But the bigger problem isn't efficiency. It's coordination.

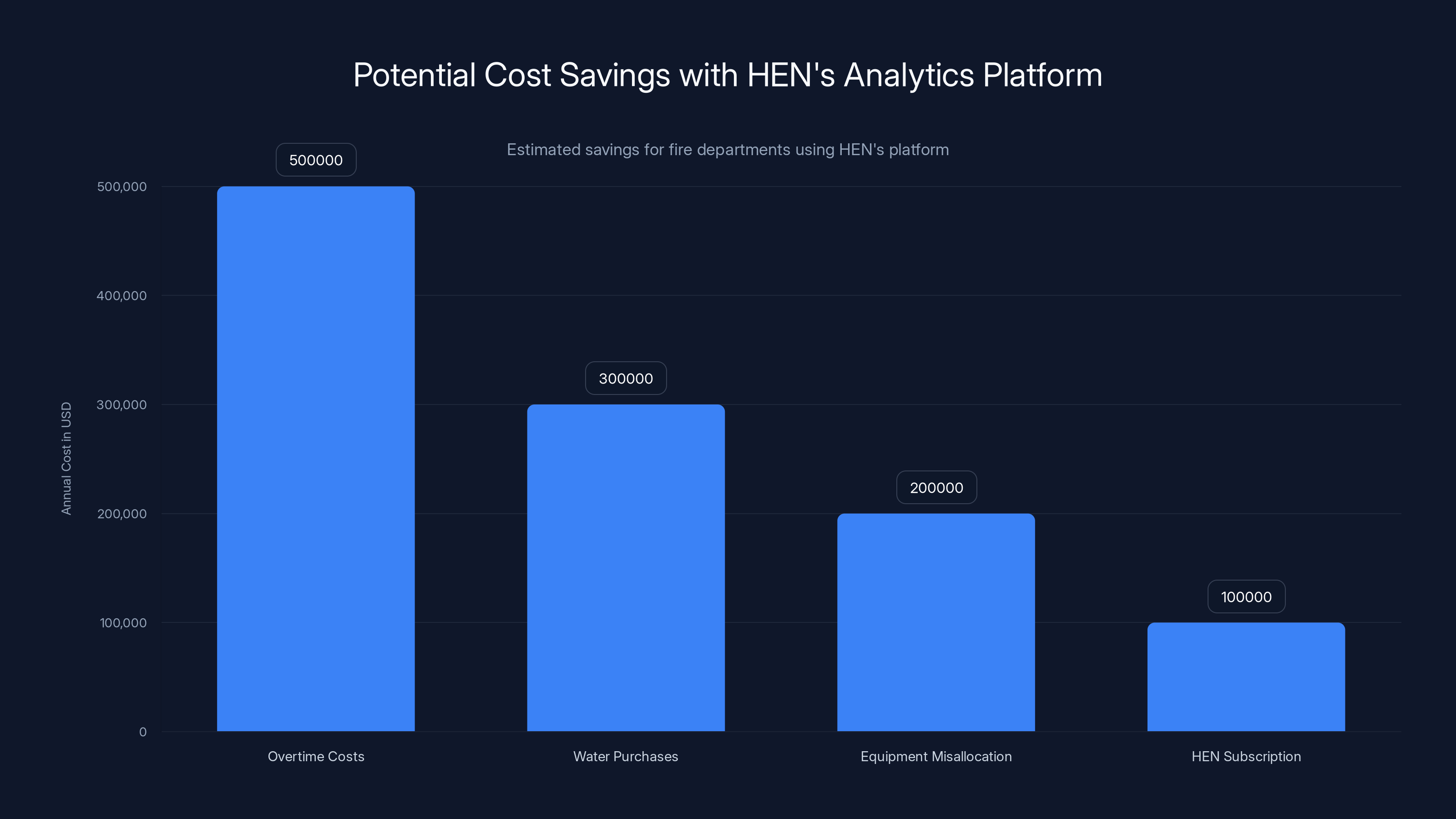

Fire departments could potentially save significant costs on overtime, water, and equipment misallocation by subscribing to HEN's analytics platform. Estimated data.

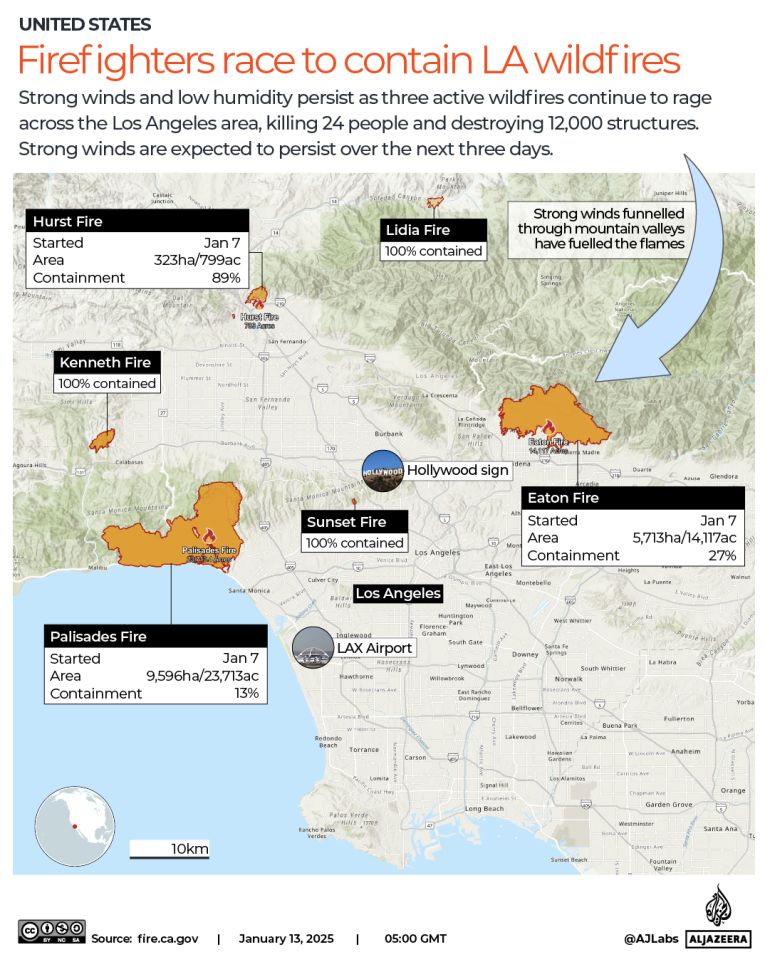

Water Shortage at the Palisades Fire

During the 2025 Palisades Fire, something went wrong that happens more often than most people realize: water suppliers and firefighters lost coordination. Departments didn't know how much water was being drawn from specific hydrants. Usage wasn't tracked in real-time. When multiple fire engines connected to one hydrant, pressure variations cascaded. One engine suddenly got nothing. The fire continued growing while firefighters stood with empty lines.

This isn't a training problem. It's an infrastructure problem.

In rural America, the situation deteriorates further. Water tenders, which are tanker trucks shuttling water from distant sources during drought conditions, face logistics nightmares. A tender might travel 45 minutes to refill. Meanwhile, fire captains have zero visibility into whether that tender is coming, when it'll arrive, or whether supply will meet demand.

The Oakland Fire in the 1990s had the same issue. Decades later, nothing changed. Fire departments operated blind, rationing water based on intuition and radio calls, not data.

Sethi saw the opportunity. Not in the nozzle itself, but in the data system that could wrap around it.

Why His Background Mattered

Sethi's unconventional path became his advantage. Most people climbing the ranks in fire suppression came through fire science. They understood flame dynamics but worked within institutional constraints. Sethi arrived as an outsider with what he calls a "bias-free and flexible" thinking style.

He'd seen multiple industries solve similar problems. At ADAP Nanotech, he researched surfaces and adhesion. The Air Force Research Lab funded his work. He developed deep material science intuition about how particles interact, how surfaces behave, how adhesive forces work at different scales.

At Sun Power, he translated that into solar panel design, working on shingled photovoltaic modules. At TE Connectivity, he engineered new adhesive formulations to enable faster automotive manufacturing. Each role exposed him to different problem-solving frameworks. Materials engineering. Process optimization. Manufacturing constraints. Supply chain logic.

When he started HEN in June 2020, he brought that toolkit. Traditional nozzle manufacturers asked: "How do we improve water delivery?" Sethi asked: "How do we make water delivery measurable, predictable, and connected to a larger system?"

The answer required materials science to engineer precise droplet control. It required fluid dynamics simulation using computational tools. It required embedded systems knowledge to put sensors and processors inside "dumb" hardware. It required cloud architecture to ingest and process real-time data from thousands of devices. And it required firefighting domain knowledge to understand what questions the data should answer.

No single background had all of this. Sethi's zigzag career actually prepared him perfectly.

HEN's nozzles show a documented 300% improvement in suppression rates compared to traditional nozzles, enhancing fire cooling and stream coherence.

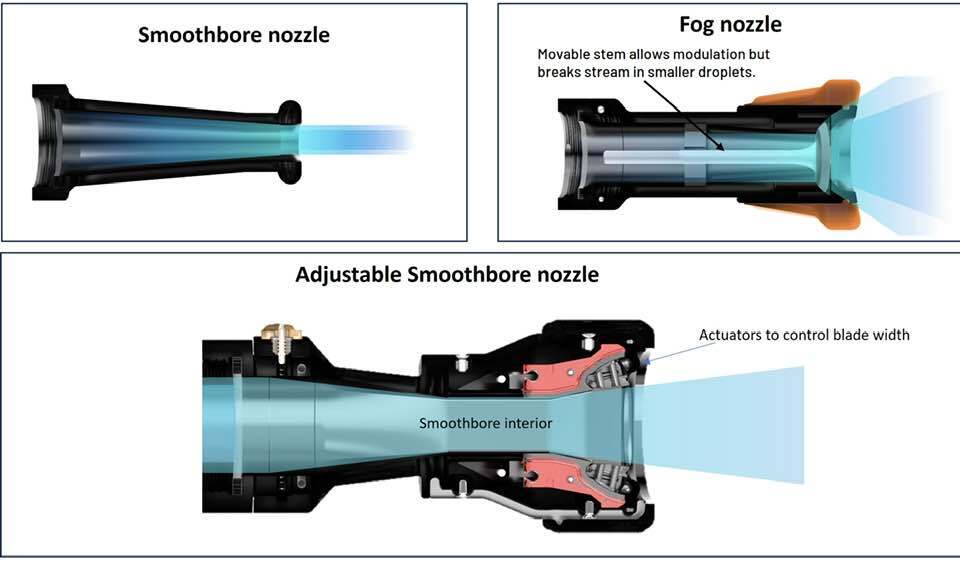

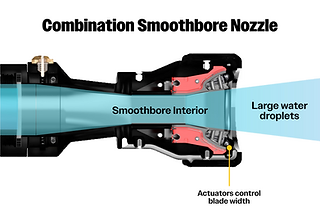

How The Nozzle Physics Actually Work

Traditional nozzles use simple geometry to direct water flow. Water enters, gets squeezed through an opening, exits in a pattern. Physics determines everything else. Water molecules collide, turbulence increases, the stream falls apart.

HEN's nozzles solve this through three mechanical innovations. First, they control droplet size precisely. Smaller droplets evaporate faster, increasing the cooling effect. Larger droplets penetrate further. HEN's design balances this, creating droplets in the optimal size range for fire suppression. Second, they manage velocity in novel ways, maintaining stream coherence across longer distances. Traditional nozzles lose coherence after 20-30 feet. HEN's maintain it further.

Third, they resist wind. In extreme wind conditions, which are common in wildfire environments, traditional nozzles get completely deflected. HEN's geometry keeps the core stream intact even with significant crosswinds.

Sethi conducts computational fluid dynamics analysis to optimize these parameters. He simulates water flow, droplet trajectories, wind interaction, and thermal effects. The physics is elegant. The implementation is meticulous. The result is measurable: a 300% improvement in suppression rates under controlled conditions.

But here's the critical insight: the nozzle itself is just the hardware foundation. What matters more is everything else he built on top of it.

From Hardware to Connected Systems

In 2020, when HEN launched, the company's mission seemed straightforward: build better nozzles. By 2025, the product line had expanded dramatically. HEN now manufactures monitors, valves, overhead sprinklers, pressure devices, and various discharge control systems. Each device is "smart," meaning it contains custom-designed circuit boards with sensors and computing power.

Some devices are powered by Nvidia Orion Nano processors, which are compact, efficient chips designed for edge computing. Sethi's team has designed 23 different circuit board configurations. Each device collects data: when it activates, how much water flows, what pressure is required, what the ambient conditions are.

The cloud platform is where the real innovation lives. HEN built application layers that Sethi compares to what Adobe did with cloud infrastructure. Think subscription-based, modular, à la carte systems for different fire department roles: captains, battalion chiefs, incident commanders. Each has different information needs.

A fire captain needs real-time status on water supply for their specific engine. A battalion chief needs pressure and flow data across multiple units. An incident commander needs weather forecasting, resource allocation recommendations, water tender positioning, and predictive alerts.

The system has weather integration. It has GPS in all devices. It can predict wind shifts 10 minutes out and alert crews that they need to reposition their engines or risk losing suppression capability. It can warn that a particular fire truck is drawing down its water supply faster than expected and a tender needs to redeploy.

The Data Lake That Powers Everything

Sethi isn't monetizing the data yet. Instead, he's deliberately building out infrastructure to accumulate as much high-quality data as possible. Every device HEN deploys is a data node. Every fire suppression event generates records: location, timing, water usage, pressure, weather conditions, equipment status, personnel assignments.

Over months and years, this becomes a comprehensive dataset about how fire suppression actually works in the real world. What pressures are needed for different fire types? How does wind affect suppression effectiveness? Which hydrant locations have pressure problems? How do seasonal variations affect water availability? What's the correlation between device positioning and fire containment speed?

This data has never been systematically collected before. Fire departments have anecdotal experience. They know certain techniques work. But they don't have the quantitative evidence.

Sethi is building the first comprehensive data lake for fire suppression. Next year, his company plans to start commercializing application layers with built-in intelligence. This is where machine learning comes in.

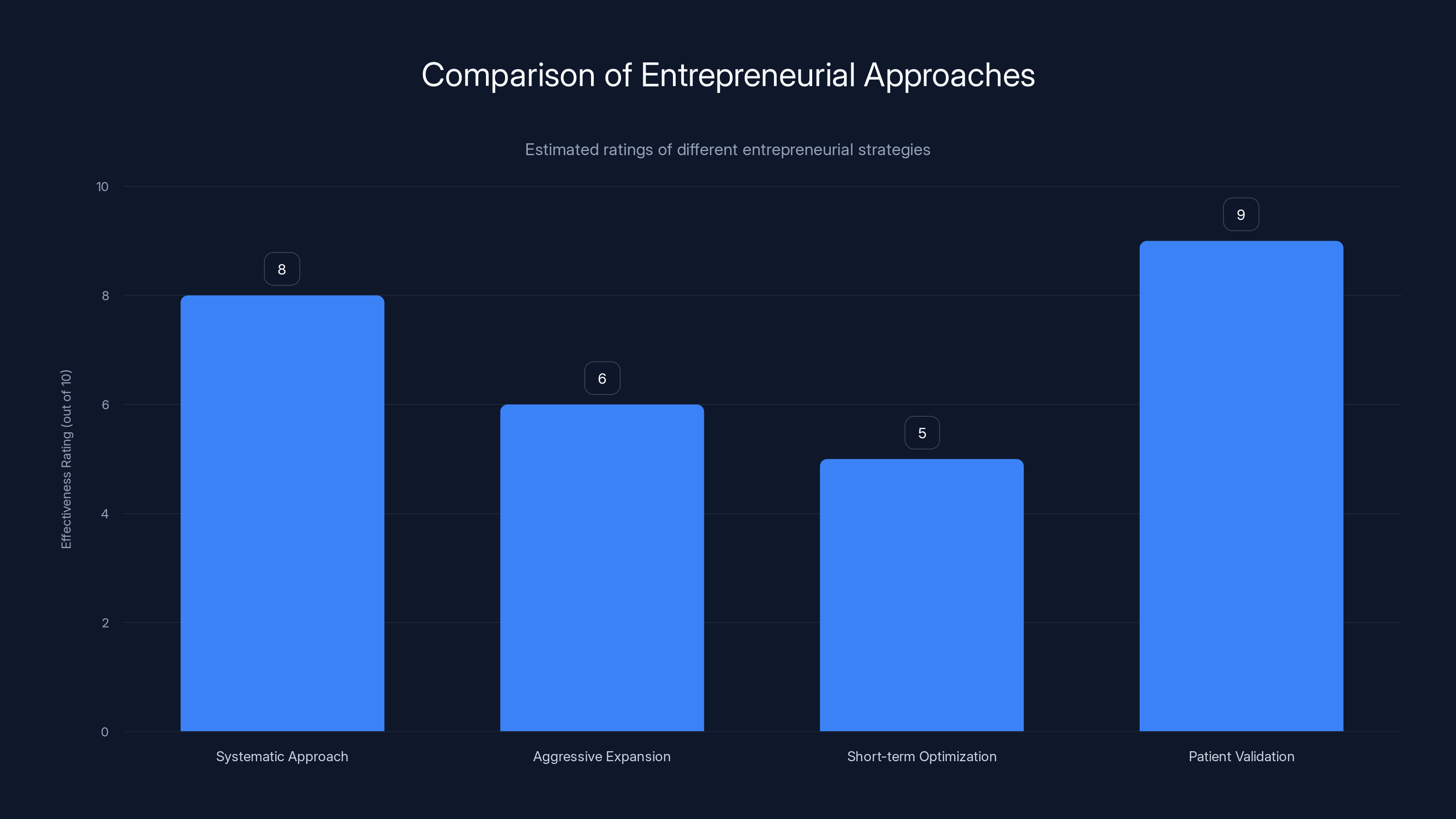

The systematic approach and patient validation are estimated to be more effective in building durable and valuable businesses compared to aggressive expansion and short-term optimization. Estimated data.

Machine Learning in Emergency Response

Predictive analytics in firefighting requires good quality data. You can't build reliable models on incomplete information. This is why Sethi emphasized that hardware came first: "You can't have predictive analytics unless you have good quality data. You can't have good quality data unless you have the right hardware."

Once you have the data, the AI applications become obvious. Machine learning models can predict water demands based on fire characteristics. They can optimize engine deployment across a county. They can forecast which water sources might become unavailable and reroute resources preemptively. They can recommend hose configurations and nozzle settings based on fire conditions.

Consider a simple use case: a captain is arriving at a structure fire. Based on the building's characteristics, weather conditions, and historical data from 50,000 similar fires, the system recommends specific pressure settings and nozzle configurations that have proven most effective. Instead of trial-and-error, the captain has evidence-based guidance.

Or consider a larger scale: a county fire coordinator needs to position resources before a predicted wind event. The system analyzes where fires are most likely to start, where equipment is currently located, what water sources have capacity, and recommends positioning that would minimize response time. During the 2025 California fire season, this kind of predictive positioning could have prevented water shortages that actually occurred.

The machine learning models improve continuously as more data accumulates. They become more accurate. More specific to local conditions. More useful.

20 Patents and Counting

Sethi's team has filed 20 patent applications, with roughly half granted so far. These patents cover different aspects of the system: the nozzle geometry itself, the droplet control mechanisms, the pressure management systems, the sensor integration approaches, the data collection protocols, and the cloud-based analytics platform.

In hardware-software convergence, patents matter differently than in pure software. A software patent protects an algorithm. A hardware patent protects a physical design. HEN's portfolio protects both: the physical innovation in water suppression and the system integration approach.

Competitors can't simply copy HEN's designs. The patents create a moat. More importantly, they demonstrate deep technical work and genuine innovation. Twenty patent applications from a company founded in 2020 shows serious engineering velocity.

The patent strategy also telegraphs where Sethi is headed. Patents on cloud integration and sensor systems suggest the company sees hardware as infrastructure for data collection, not as the endgame itself.

How This Compares to Existing Systems

Before HEN, fire departments relied on manual coordination and institutional knowledge. A fire captain knew their district's hydrant locations. They knew which streets had pressure problems. They maintained this knowledge through experience and radio communication.

When a fire started, dispatch would send units. The captain would decide where to set up based on wind, fire behavior, and experience. They'd open the nozzle and adjust pressure manually. If water ran low, they'd radio for a tender. If communication broke down or assumptions were wrong, they had no backup plan.

The system was reactive, not predictive. It depended entirely on individual expertise. It didn't accumulate learning. A captain in County A couldn't benefit from best practices discovered in County B.

HEN's system inverts this. It's predictive. It's systematic. It captures learning. It shares insights across geography and time. A captain in County A now sees what worked in County B last year under similar conditions.

The integration of hardware and software also creates network effects. Each new device deployed makes the system more valuable for all existing deployments. More data. More patterns. More accurate predictions. More useful recommendations.

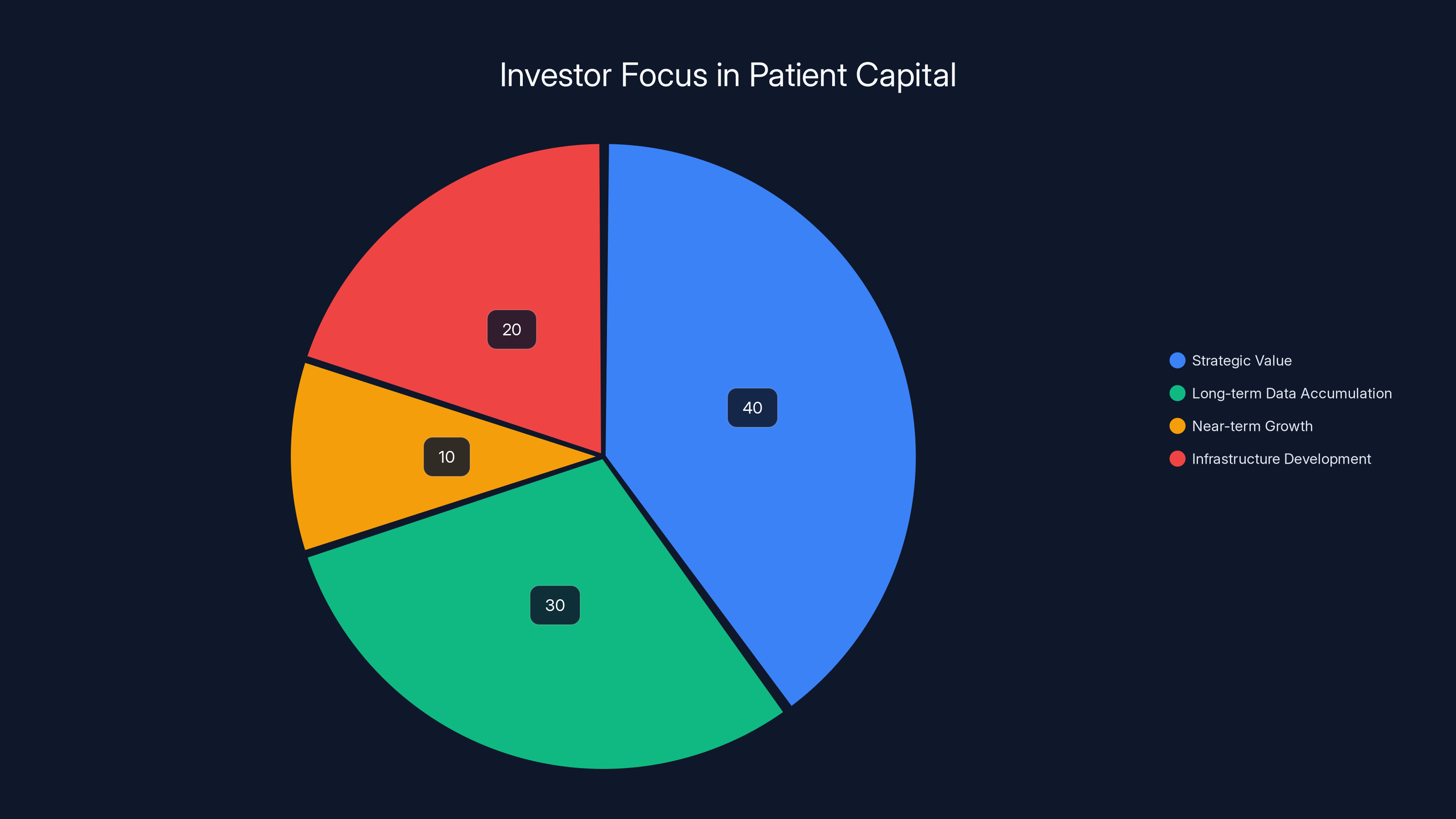

Estimated data suggests that investors in patient capital prioritize strategic value and long-term data accumulation over near-term growth. This aligns with the infrastructure development focus.

The Path to Commercialization

Sethi has been deliberately methodical about rollout. Rather than rushing to sell licenses, he's installing devices, building the data pipeline, creating the data lake. This is unsexy but strategic. You can't sell predictive insights until you have data to base them on.

By late 2025, HEN had accumulated suppression data from hundreds of fires across California and multiple states. The database includes various fire types: structure fires, wildland-urban interface fires, vegetation fires. Different geographic regions. Different seasons. Different equipment configurations.

This dataset is the moat. Competitors can copy hardware faster than they can accumulate fire suppression data. Competitors can't immediately replicate the cloud platform and machine learning models. But competitors absolutely can't buy the institutional knowledge locked in years of real-world fire data.

Next year, commercialization begins in earnest. Application layers with built-in intelligence will be sold as subscriptions. Fire departments will pay for insights, not just hardware. The economics of this model are compelling.

Consider the value proposition to a county fire department. A subscription to HEN's analytics platform might cost

The Regulatory and Adoption Challenge

Fire suppression isn't like consumer software. You can't deploy a new feature and iterate based on feedback. Failures have deadly consequences. Regulatory approval is slow. Adoption requires building trust with conservative institutions.

Fire departments are also notoriously underfunded. Budget cycles are annual. Adoption of new technology requires capital approval. The decision-making process involves city councils, county supervisors, union representatives, and established vendors. This isn't Silicon Valley moving at light speed.

Sethi has navigated this by working directly with departments on pilots. A small deployment proves the technology works. Success on a local level builds trust. Other departments see the results and follow.

The Palisades Fire situation accelerated adoption interest. After water shortages nearly caused catastrophic failures, departments became urgently interested in better coordination systems. The pain point was undeniable. HEN's timing was perfect.

The AI Goldmine Beyond Firefighting

Here's where this gets interesting for Sethi's longer-term vision. The data lake he's building isn't just about fire suppression. It's about emergency response broadly.

Machine learning models trained on fire suppression data can be applied to other emergency response domains. Police departments managing resources during civil unrest face similar allocation problems. Medical teams managing patient flow during mass casualty events need predictive tools. Disaster response agencies need weather-based positioning forecasting. Utility companies managing power outages during extreme weather need resource optimization.

The specific models would be different, but the underlying infrastructure is reusable. A cloud platform for emergency response data collection, analysis, and recommendation is valuable across multiple domains.

Sethi has hinted at this larger vision. The "muscle on the ground" is the hardware. The cloud platform is the nervous system. The analytics and AI are the brain. Firefighting is the first domain where this brain proves itself. But it's not the only domain where it matters.

If HEN can establish dominance in fire suppression, the data advantage becomes insurmountable. Competitors entering adjacent domains (police resource allocation, medical logistics, disaster response) would start with zero data. HEN would start with years of comparative advantage.

This is the play that could make HEN genuinely valuable at venture scale. Not "better nozzles." But "the operating system for emergency response data and AI."

HEN nozzles offer a 300% improvement in suppression efficiency over traditional nozzles, highlighting a significant advancement in fire suppression technology (Estimated data).

The Founder Psychology Behind This

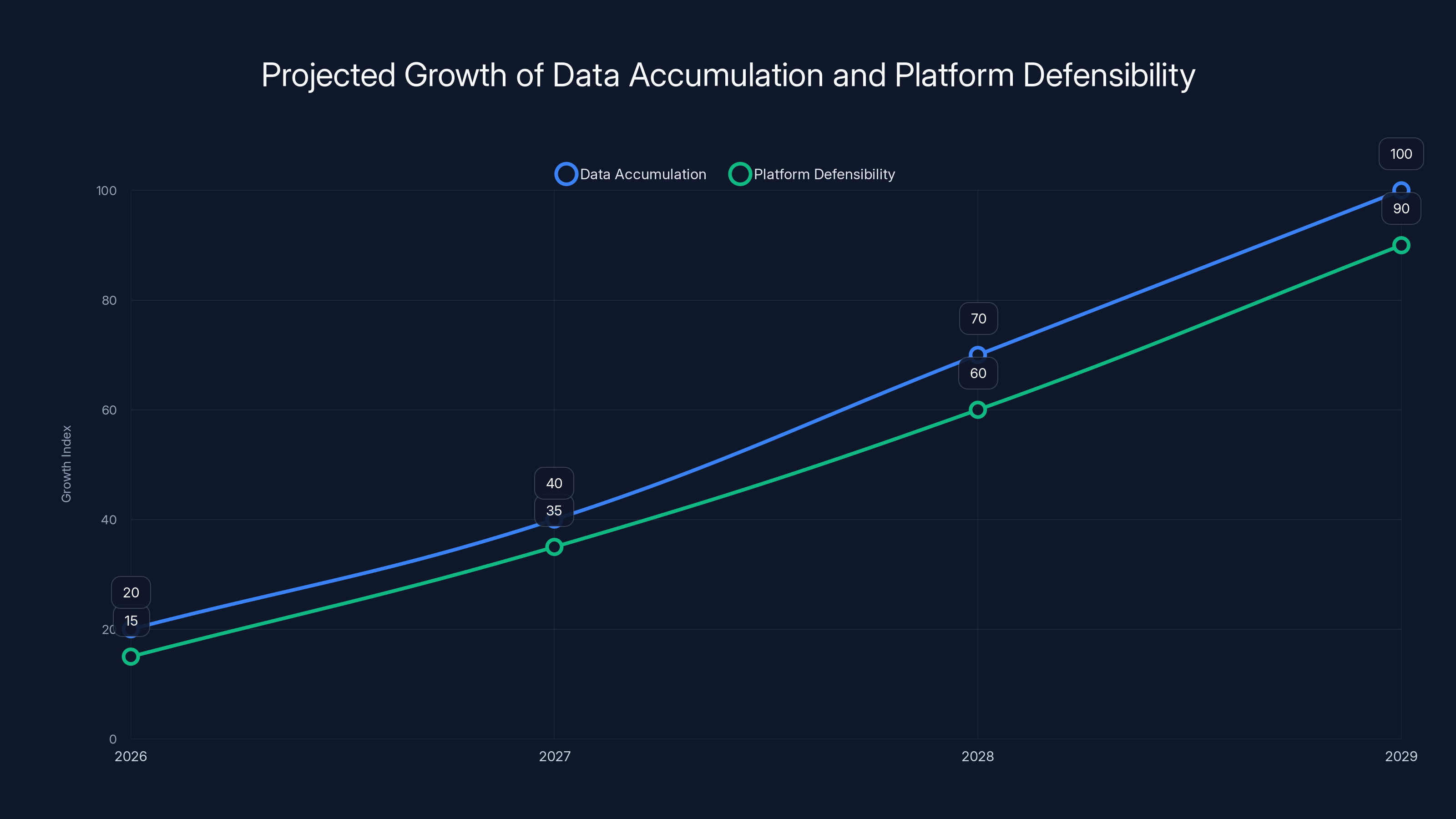

What's revealing about Sethi's approach is that he's not optimizing for the obvious metrics. He's not trying to maximize nozzle sales or software license revenue in 2026. He's optimizing for data accumulation and platform defensibility in 2027, 2028, and beyond.

This requires unusual patience for a tech founder. You have to invest in infrastructure that doesn't directly generate revenue. You have to care more about data quality than quarterly growth. You have to resist the temptation to monetize prematurely.

Speaking about his journey at Disrupt conferences and industry events, Sethi doesn't project typical startup urgency. He seems genuinely more interested in the technical problem than the business outcome. Whether this is authentic or expertly performed doesn't matter much. The result is the same: he's building something long-term and structural, not trying to flip a quick exit.

His wife's challenge during that 2019 evacuation planted the seed. But what kept it growing was this engineer's mindset: when facing a broken system, you don't cut corners. You start from first principles, understand the physics and logistics, and build infrastructure that works systematically.

Manufacturing and Supply Chain Innovation

Building smart fire suppression devices at scale introduces manufacturing complexity that most tech companies never encounter. Each device contains sensors, circuit boards, processors, and embedded software. The manufacturing process must be reproducible, reliable, and cost-effective. Small defects cascade into field failures that could literally cost lives.

Sethi's background in automotive manufacturing at TE Connectivity proved valuable here. He understands yield optimization, quality control, and scaling production from thousands to hundreds of thousands of units. He's worked on assembly line processes where precision matters.

HEN manufactures devices at a facility in California. They've optimized the assembly process to keep costs down while maintaining reliability standards. Each unit is tested before deployment. The supply chain for components is carefully managed because a shortage of any single element could halt production.

This manufacturing discipline is invisible to end users but critical to long-term success. Competitors who cut corners on quality or scaling will find themselves with field failures and damaged reputation at exactly the moment they're trying to build market trust.

Sethi's insistence on reliability over rapid growth is partly technical prudence and partly strategic. If fire departments experience failures, they lose interest in connected systems. If they experience reliability, adoption accelerates.

Integration with Existing Fire Department Infrastructure

Fire departments operate on systems built over decades. Dispatch systems use radio protocols from the 1980s. Water infrastructure dates back further. Some departments don't have digital maps of their service areas. Others do.

HEN's devices have to integrate with this heterogeneous landscape. A new smart nozzle needs to connect to both modern departments with digital systems and rural departments working largely on paper and radio.

This is why the modular approach matters. Some applications are cloud-based, requiring internet connectivity. Others function offline, storing data locally until connectivity is restored. Some departments want full integration with their dispatch system. Others want a simple dashboard they access separately.

The flexibility makes adoption possible across different institutional contexts. A rural fire district can deploy HEN devices without overhauling their entire operational infrastructure. A large urban department can integrate HEN data into their existing systems.

Sethi's focus on long-term data accumulation and platform defensibility is projected to significantly increase from 2026 to 2029. Estimated data.

Competitive Moats and Market Dynamics

In traditional hardware markets, competitive advantage erodes quickly. A competitor sees your design, engineers around it, and undercuts your price. Established manufacturers (like Akron Brass, which has dominated fire equipment for generations) can leverage existing relationships and scale.

But HEN isn't competing on hardware alone. The data moat is deeper. HEN has suppression effectiveness data from hundreds of fires. A competitor would need to deploy devices in hundreds of fires to accumulate equivalent data. That would take years.

The software moat matters too. Machine learning models improve with more data and more iterations. HEN's models are trained on two years of operational data. A new competitor's models start with zero data. Even if they build technically superior software, it won't perform as well on unfamiliar problem spaces.

Akron Brass (the dominant traditional manufacturer) could theoretically acquire HEN or build a competing smart system. They have distribution relationships that HEN lacks. They have manufacturing capacity and cost advantages. But they don't have the institutional knowledge about how to build predictive analytics for emergency response. Building that from scratch would take years. Acquiring HEN probably makes more sense strategically.

This creates an interesting dynamic. HEN isn't trying to be a massive independent company. It's positioning itself to be strategically valuable to a larger player, but only after proving the data and software moats are defensible.

The Broader Implications for Hardware Startups

HEN's approach offers lessons for other hardware startups building connected devices. The obvious insight is that hardware alone isn't enough. You need software, data, and platforms.

But the deeper insight is about sequencing. HEN didn't try to launch with full commercial platform ambitions. They built hardware first. They shipped devices. They accumulated data. Only then did they start building the analytics layer.

Many hardware startups try to do this simultaneously. They build the device and the cloud platform and the machine learning models all at once. They launch with half-baked features, trying to gather feedback for all three pieces concurrently. This makes it impossible to validate whether problems come from hardware, software, or misaligned incentives.

Sethi's approach is: get hardware right first. Ship it. Learn from real deployment. Then build software on the foundation of real operational experience. This is slower to market but produces better outcomes.

The other lesson is about patience with monetization. Most startups need to charge immediately to prove unit economics. HEN instead invested in infrastructure for years before serious revenue. This required either patient capital (investors who understood the long-term play) or founder capital (Sethi bootstrapping or having other resources).

This approach isn't feasible for all startups, but it's possible for founders with a specific thesis about where defensible value will eventually sit.

Looking Ahead: The 2026 Roadmap

Sethi has publicly outlined plans for launching new flow-control devices and discharge control systems in 2026. The cloud platform will expand with more sophisticated machine learning models. The application layer will roll out to early customer fire departments.

The focus remains on data accumulation. Each new deployment is valuable not for immediate license revenue but for the insights it will eventually generate. Each fire adds to the training data. Each geographic region adds local context to the models.

By 2027, HEN should have sufficient data diversity to make strong claims about prediction accuracy. The models will be tested against holdout test sets. The performance will be publicly shared. Third-party validation of the science will come.

This is when the company becomes truly defensible. Not because the patents are strong, but because the empirical evidence of value is overwhelming.

Sethi's longer-term vision appears to be transforming fire department operations through data-driven insights. The nozzles and devices are infrastructure. The cloud platform is the interface. The machine learning models are the intelligence. Fire departments that adopt HEN shift from reactive, experience-based operations to predictive, data-driven operations.

If this works at scale, it's transformative. If water shortages at major fires become preventable through better predictive positioning, it changes how fire departments approach extreme weather seasons. If suppression effectiveness improves through evidence-based techniques, fewer structures burn. If firefighter safety improves because positioning is optimized, that's a massive win.

The financial upside is secondary to these outcomes in Sethi's framing. But they're connected. The more valuable the safety and effectiveness improvements, the more fire departments will pay for the platform. The more adoption, the more data. The more data, the more valuable the models.

Lessons from Materials Science to Entrepreneurship

Watching Sethi's trajectory from Ph.D. researcher to tech founder, there's a consistent thread: he's more interested in understanding systems at a fundamental level than in optimizing for short-term outcomes.

In materials science, you study how atoms arrange, how surfaces interact, why certain compounds have specific properties. You're working at fundamental levels, and understanding them deeply takes time. You can't shortcut this.

In firefighting, he applied the same rigor. What are the fundamental physics of water suppression? How do droplets interact with flames? How does wind disrupt suppression effectiveness? Build models. Test models. Refine models.

In startup building, he's applying the same patient, systematic approach. Don't shortcut the data accumulation phase. Don't oversell capabilities before you've validated them on diverse real-world scenarios. Build defensible moats, not quick wins.

This probably limits his upside versus a more aggressive founder who'd try to raise $500 million, expand to 20 product lines, and pursue an IPO in five years. But it maximizes his probability of building something genuinely durable and valuable.

The wife's challenge in 2019 was the trigger. But what made HEN possible was a founder with the training, experience, and temperament to treat a societal problem as seriously as a physics researcher treats a complex system.

The Unsexy But Crucial Details

One thing that rarely gets attention in startup narratives is attention to unglamorous details. HEN's success ultimately depends on things like: Are the circuit boards reliable? Do the sensors drift over time? Can the software handle edge cases in weather prediction? Are the API calls to the cloud platform latency-constrained?

These aren't exciting to discuss, but they determine whether the system actually works in practice. A nozzle that's theoretically 300% more effective but breaks down in the field isn't actually more effective.

Sethi's background in manufacturing, semiconductors, and process optimization meant he understood the importance of these details. He probably spent as much time engineering reliability into the system as he spent on the high-level value proposition.

This is what separates companies that look good in press releases from companies that actually work when real lives depend on them.

Why The Timing Was Right

HEN launched in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, when supply chains were disrupted and attention was fragmented. It seems like terrible timing. But 2020 was also the year that California's fire season hit new severity levels. The Camp Fire had been 2018. The Kincade Fire had been 2019. The 2020 fire season was catastrophic.

Fire departments were desperate for any innovation that might help. Political attention on wildfire preparedness was at peak intensity. Federal funding for emergency response infrastructure was increasing. The pain was undeniable.

Bad timing for a general tech startup. Perfect timing for a company solving a specific crisis.

Sethi recognized this. Rather than waiting for perfect conditions, he launched into the fire. Literal and figurative. The urgency of the problem created an opening that wouldn't have existed in a quieter year.

The Role of Patient Capital

Building HEN's vision requires patient capital. Investors who understand that profitability might be 5-7 years away. Investors who care about strategic value more than near-term growth metrics.

Sethi has likely worked with venture capital, but not the kind that demands hockey-stick growth graphs. More likely the kind that understands infrastructure plays: better to have 50 deployed systems with excellent data than 5,000 deployed systems with garbage data.

This capital structure determines everything about decision-making. A founder with demanding quarterly growth targets makes different choices than one with long-term backing.

Without knowing HEN's specific investor composition, it's reasonable to infer that Sethi has structured his capital raise around people who understand the data moat thesis. Because if your investors are demanding revenue growth, you can't spend years accumulating data without generating licensing fees. The math doesn't work.

Conclusion: Why This Matters Beyond Firefighting

HEN Technologies is interesting not because fire suppression itself is a hot venture category. It's interesting because Sethi cracked a formula that works: take an ancient industry, apply modern materials science and data infrastructure, build a defensible moat through accumulated knowledge, and position for massive scaling once the moat is proven.

The specific domain is almost incidental. It could be water management, agricultural optimization, infrastructure monitoring, or a dozen other legacy industries. The formula is portable.

What's rarer is finding founders with the right background (materials science, manufacturing, multiple industries), the right temperament (patient, systematic, less interested in press attention than in deep technical work), and the right motivation (personal mission rather than financial maximization).

Sethi is pursuing this for a specific reason: his wife challenged him to fix wildfire evacuation risks. That's a why. A real why. Not "I want to disrupt firefighting" but "my family shouldn't live in fear, and if I can apply my skills to fix this, I should."

Companies built on that foundation tend to endure. The next question is whether HEN can scale the model beyond firefighting. Whether the data and AI infrastructure generalizes to other emergency response domains. Whether Sethi can grow the company without losing the systematic, quality-focused approach that made it possible.

Based on his track record, the odds are better than they look. He's not a typical founder optimizing for headlines and growth at all costs. He's building something that might actually work, which in the startup world is surprisingly rare.

The fire nozzle is just the muscle on the ground. The real play is whether Sethi can build the operating system for emergency response. If he does, the implications extend far beyond firefighting.

FAQ

What makes HEN's nozzles more effective than traditional designs?

HEN's nozzles improve suppression rates through three mechanisms: precise droplet size control optimized for fire cooling, velocity management that maintains stream coherence over longer distances, and wind-resistant geometry that prevents deflection in extreme conditions. Computational fluid dynamics analysis guides the design, resulting in documented 300% suppression improvement rates compared to traditional nozzles at equivalent flow rates.

How does HEN's connected system help fire departments?

HEN embeds sensors and processors in fire suppression devices to collect real-time data on water usage, pressure, location, and timing. This data feeds into cloud-based analytics that provide predictive insights: optimal engine positioning based on forecasted fire behavior, alerts about imminent water shortages, wind shift warnings, and resource allocation recommendations. Departments shift from reactive, experience-based operations to data-driven decision-making.

What data does HEN's platform collect from fire suppression events?

The system captures when devices activate, water flow rates, pressure variations, GPS location, equipment status, weather conditions, and timing data. Over hundreds of fire deployments, this creates a comprehensive dataset about real-world suppression effectiveness. The dataset trains machine learning models to predict outcomes and recommend optimal tactics in future incidents.

Why is accumulated fire suppression data valuable as a competitive moat?

A competitor can copy hardware designs and build similar cloud platforms, but can't immediately acquire years of operational fire data. HEN's models are trained on hundreds of real fires across different regions, seasons, and fire types. A competitor's models start with zero data and would need years of deployment to reach equivalent training data volume. This creates an insurmountable early advantage.

When will HEN start charging for its platform services?

Sethi has indicated that commercialization of application layers with built-in machine learning intelligence will begin in 2026. Fire departments will pay subscription fees for analytics and recommendations, moving beyond hardware licensing alone. The company has deliberately delayed monetization to prioritize data accumulation and model development.

How does Sethi's background in materials science and automotive manufacturing relate to building fire suppression technology?

His Ph.D. research in surfaces and adhesion informed the physics of droplet behavior. His experience at Sun Power with photovoltaic design taught manufacturing scaling. His automotive work at TE Connectivity prepared him for precision assembly and quality control. His experience across industries gave him the "bias-free and flexible" thinking needed to approach firefighting as an outsider and identify systemic problems that insiders overlooked.

What other domains could HEN's emergency response platform potentially serve?

The data infrastructure and predictive analytics framework generalizes beyond firefighting to police resource allocation, medical logistics during mass casualty events, disaster response coordination, and utility company power outage management. The specific machine learning models would differ, but the underlying architecture for emergency response data collection and analysis is reusable across domains.

How many patent applications has HEN filed, and what do they protect?

HEN has filed 20 patent applications with approximately half granted to date. The portfolio covers the nozzle geometry and droplet control mechanisms, pressure management systems, sensor integration approaches, data collection protocols, and cloud-based analytics platform architecture. Patents protect both the physical innovations in water suppression and the system integration approach, creating defensible intellectual property.

What happened at the Palisades Fire that demonstrated the need for HEN's system?

During the 2025 Palisades Fire, water coordination broke down between suppliers and firefighters. Departments didn't track real-time water usage from specific hydrants. When multiple engines drew from one hydrant, pressure variations caused some engines to lose flow while fires continued growing. This systemic coordination failure had previously occurred during the Oakland Fire in the 1990s, demonstrating that the problem persists across decades without technological intervention.

How does HEN's system integrate with existing fire department infrastructure?

HEN's modular approach allows deployment across heterogeneous department contexts. Some applications function cloud-based for modern departments with digital systems. Others work offline, storing data locally until connectivity is restored. Some departments integrate HEN data into existing dispatch systems. Others access analytics through separate dashboards. This flexibility enables adoption across urban departments with modern infrastructure and rural districts operating primarily on radio and paper.

This comprehensive guide explores how Sunny Sethi transformed a single founder's challenge into a multi-domain emergency response platform, and why the implications extend far beyond firefighting into an entirely new category of predictive infrastructure technology.

Key Takeaways

- HEN Technologies increased fire suppression rates by 300% through materials science breakthroughs in nozzle design that control droplet size, velocity, and wind resistance

- The company's real moat isn't hardware; it's accumulated fire suppression data from hundreds of real incidents that trains machine learning models competitors can't instantly replicate

- Sunny Sethi's background spanning nanotechnology, solar, semiconductors, and automotive manufacturing gave him the 'bias-free' thinking needed to identify systemic problems in a 60-year-old industry

- HEN's platform enables predictive emergency response by integrating sensors across fire suppression devices to track water usage, pressure, weather, and location in real-time

- By deliberately delaying monetization to prioritize data accumulation, Sethi positioned HEN to commercialize high-value analytics and recommendations starting in 2026, creating long-term defensibility

Related Articles

- Smart Device End-of-Life Disclosure: Why Laws Matter [2025]

- AI Trends in Data Analytics: 7 Game-Changing Use Cases for 2026

- ClickHouse Hits $15B Valuation: How an Open-Source Database is Challenging Snowflake and Databricks [2025]

- Honeywell Home X2S Smart Thermostat Review [2025]

- Amazon Alexa on Web: Breaking Free From Echo Devices [2025]

- MayimFlow: Preventing Data Center Water Leaks Before They Happen [2025]

![How HEN Technologies Built a Fire Nozzle Empire on AI Data [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-hen-technologies-built-a-fire-nozzle-empire-on-ai-data-2/image-1-1769384201807.jpg)