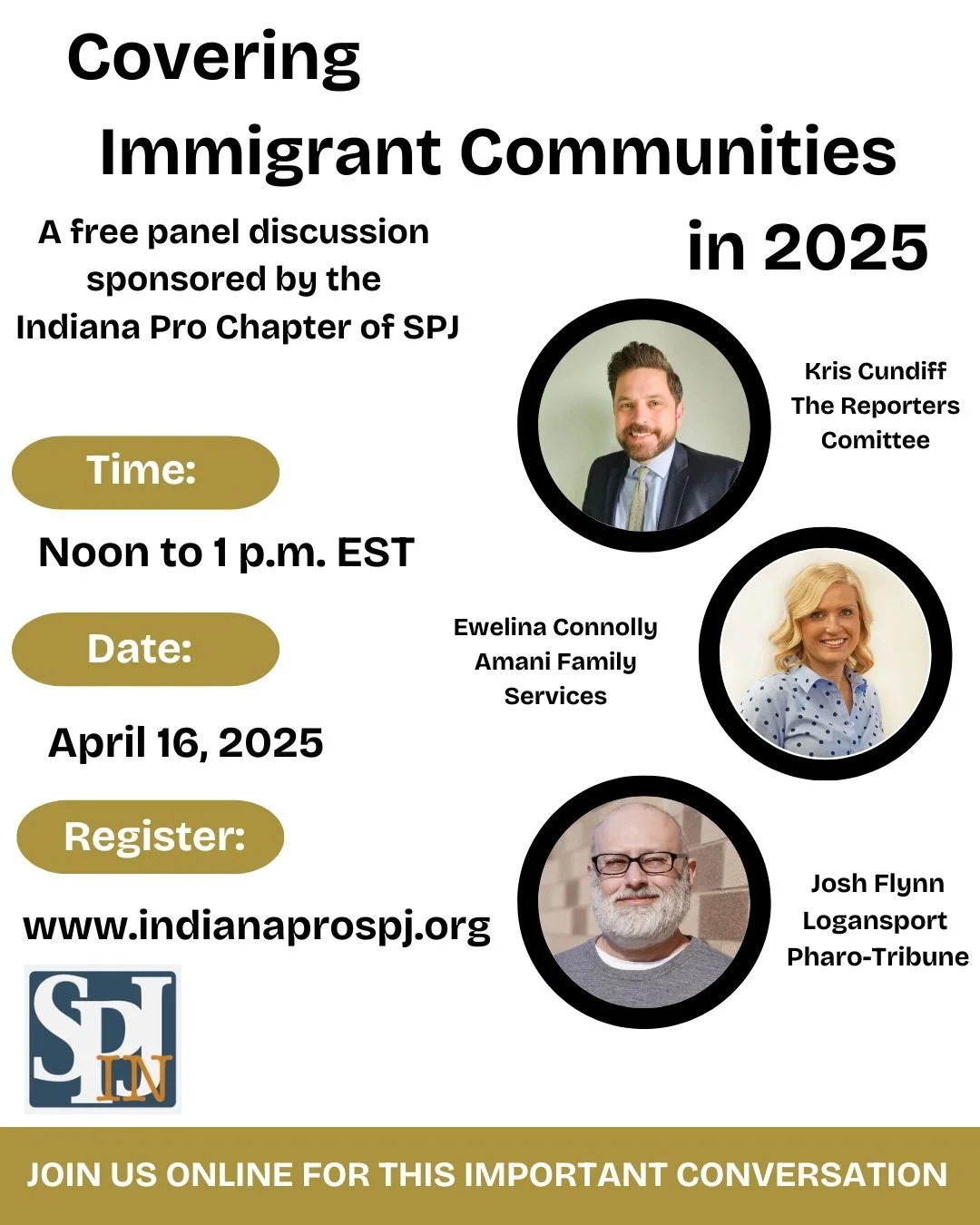

The Digital Divide Immigrant Communities Face

If you're a journalist working at a mainstream newsroom, you probably think about reaching your audience on TikTok, Instagram, or maybe YouTube. You track algorithm changes. You obsess over reach metrics. You publish, you wait for the engagement to roll in.

But here's the thing: that strategy doesn't work for immigrant communities.

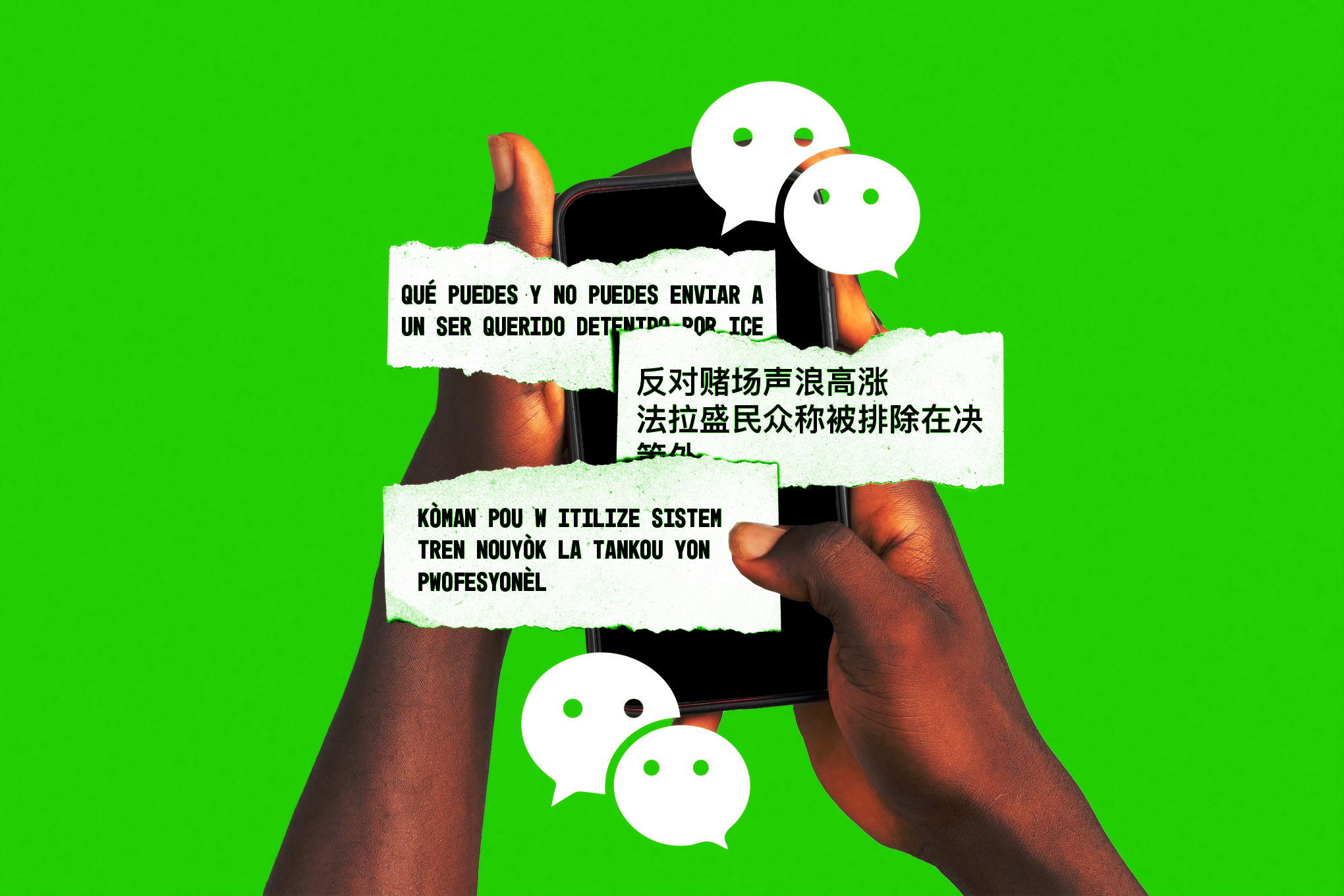

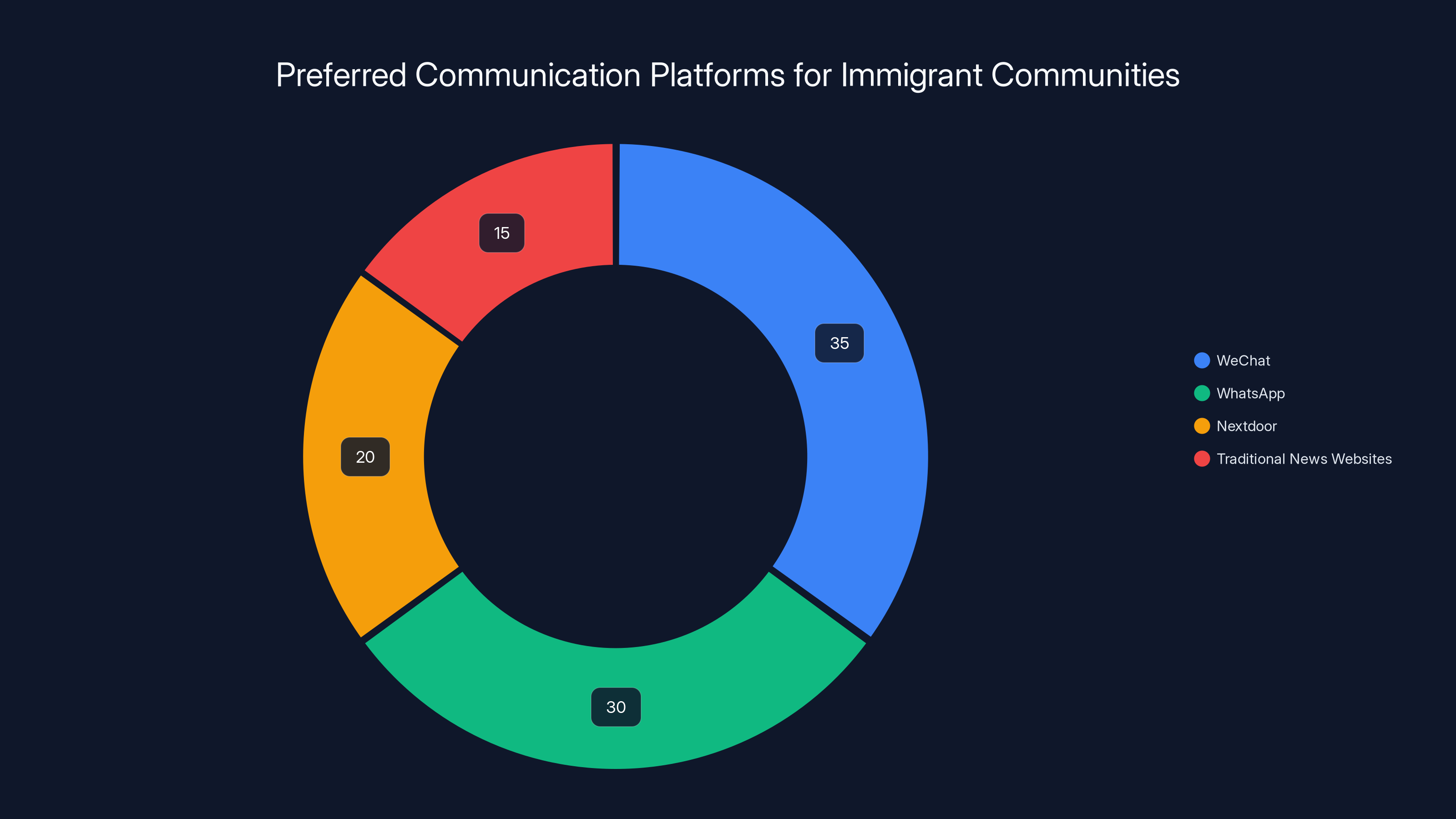

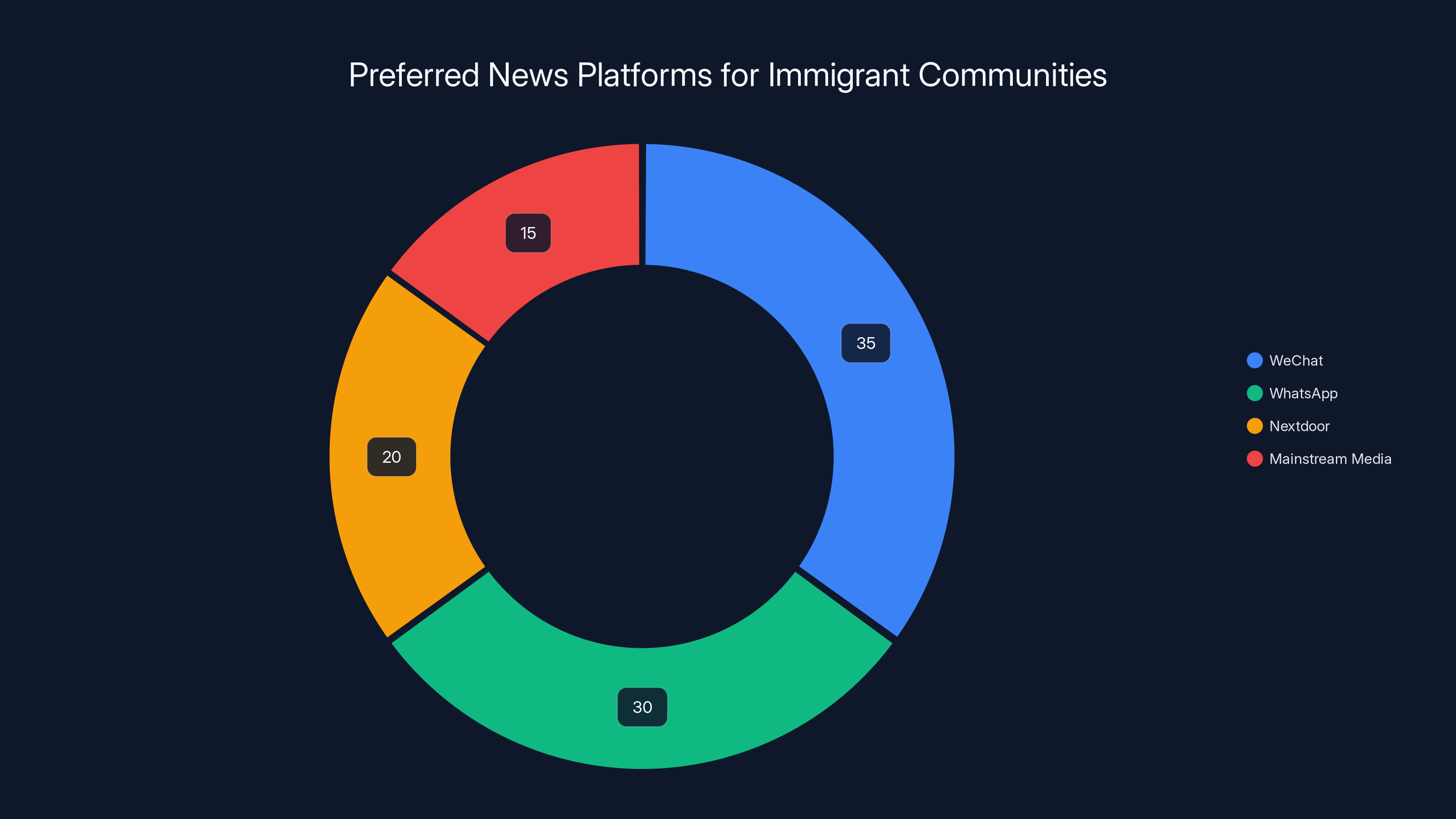

More than 40 million immigrants live in the United States, and they're consuming news in ways that would surprise most traditional media outlets. They're not on your newsroom's Instagram. They're not refreshing your website. They're on WeChat, a closed messaging platform that works like a combination of Facebook, Venmo, and WhatsApp all rolled into one. They're exchanging information on WhatsApp with other Spanish speakers in their neighborhood. They're asking trusted neighbors on Nextdoor about immigration checkpoints, free legal clinics, and school closures.

The mainstream media landscape has largely ignored this reality. When immigration becomes a breaking news story—as it has repeatedly in 2024 and 2025—the coverage that appears online is often only available in English, published on platforms that immigrant communities don't actually use, and written for an audience that isn't the people who need this information most.

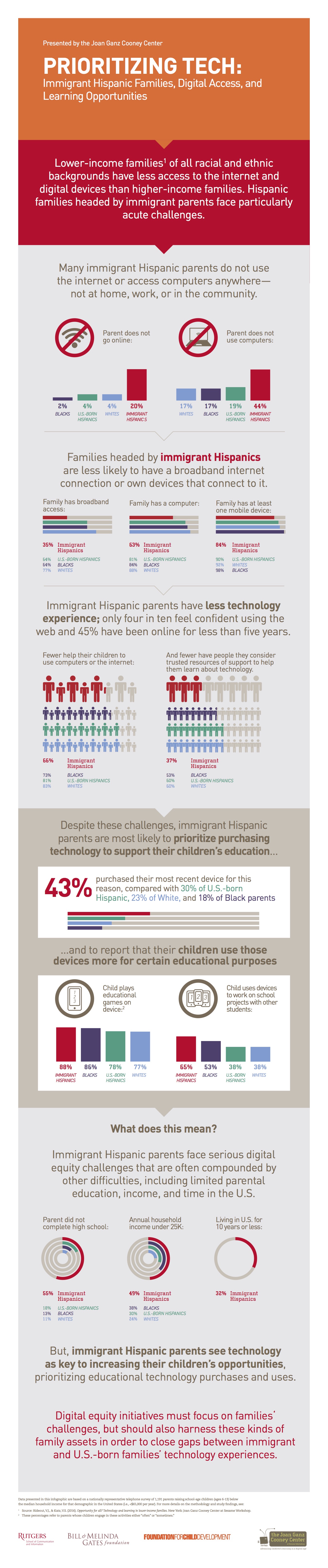

This mismatch between how newsrooms distribute information and where immigrant communities actually get their news represents one of the most significant accessibility failures in American journalism today. And it's not a technical problem. It's not a budget problem. It's a fundamental misunderstanding about what news accessibility actually means.

Accessibility isn't about posting content everywhere. It's about meeting people where they already are, in the languages they speak, on the platforms they trust. Some newsrooms have figured this out. They're experimenting with platforms that most journalism trade publications don't even mention. They're hiring reporters who speak the languages of their communities. They're rewriting the rules about how news gets distributed in the first place.

The shift is quietly reshaping what local journalism can do when it's built for actual community needs instead of engagement metrics.

Understanding the Immigrant Information Ecosystem

When we talk about "social media platforms" in journalism, we're usually thinking about companies like Meta, TikTok, or YouTube. These are the platforms that shape the media diet of English-speaking Americans. They're where newsrooms hunt for viral moments. They're where algorithms decide what millions of people see.

But immigrant communities operate within a different media ecosystem entirely. This isn't accidental. It's the result of deliberate choices that immigrant populations make based on language, trust, community, and practical need.

Consider WeChat for a moment. In the United States, it's not a mainstream social network. Most English-speaking Americans have never used it. But for the 4 million Chinese immigrants living in the U.S., WeChat isn't just a communication tool. It's essential infrastructure. It's how they stay connected to family in China. It's how they conduct business. It's how they transfer money. It's how they find community.

The platform is semi-closed, meaning you can't just stumble across content from strangers. You see posts from people you're already connected to. You participate in group chats. The algorithm doesn't promote viral content. Instead, information spreads through networks of trust: family groups, neighborhood groups, professional groups, religious groups.

This structure creates both opportunity and responsibility for newsrooms. The opportunity is obvious: if you establish yourself as a trusted source within a WeChat community, your content will reach people who are actively seeking information about their lives and their futures. The responsibility is equally clear: you're entering spaces built on trust, not metrics. You can't manipulate. You can't optimize for engagement. You have to actually serve the community.

The same principle applies to other platforms. WhatsApp is where Spanish-speaking immigrants coordinate with their families, their employers, and their neighbors. Nextdoor is where Caribbean immigrants ask neighbors for recommendations and information. These aren't platforms optimized for reach or virality. They're optimized for communication within bounded communities.

Understanding this ecosystem requires reporters to think differently about what news actually is. It's not a headline designed to get clicks. It's information that helps people make decisions about their lives. Where can I find a free English class? What documents do I need for my green card application? Is there a school closing tomorrow due to weather? Should I drive my car if there's a checkpoint nearby?

This is news as utility. And utility-focused news doesn't spread through algorithms. It spreads through networks of trust.

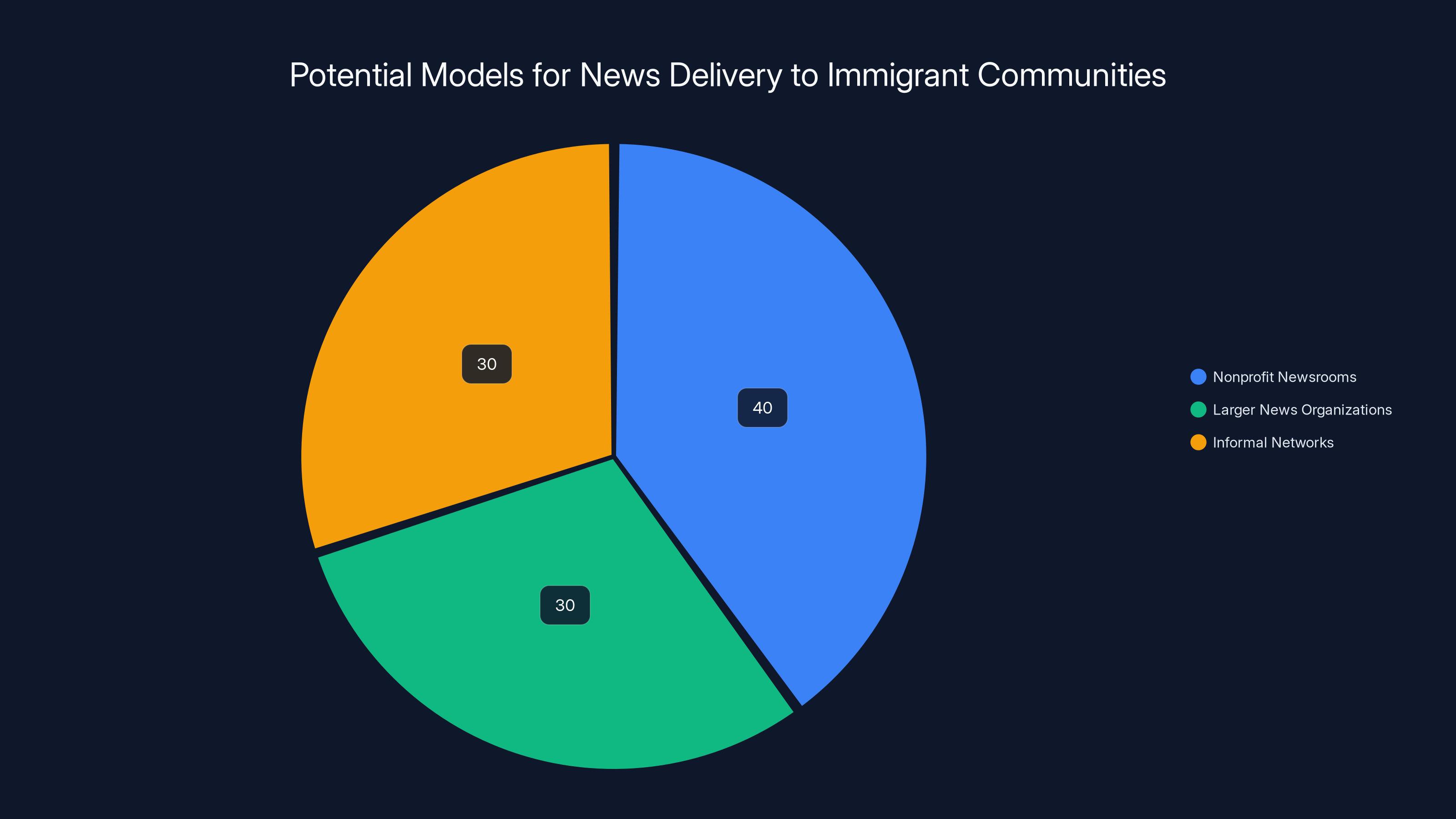

Estimated data suggests that nonprofit newsrooms may lead in delivering news to immigrant communities, followed closely by larger news organizations and informal networks.

Why WeChat Changed Everything for Chinese-Speaking Audiences

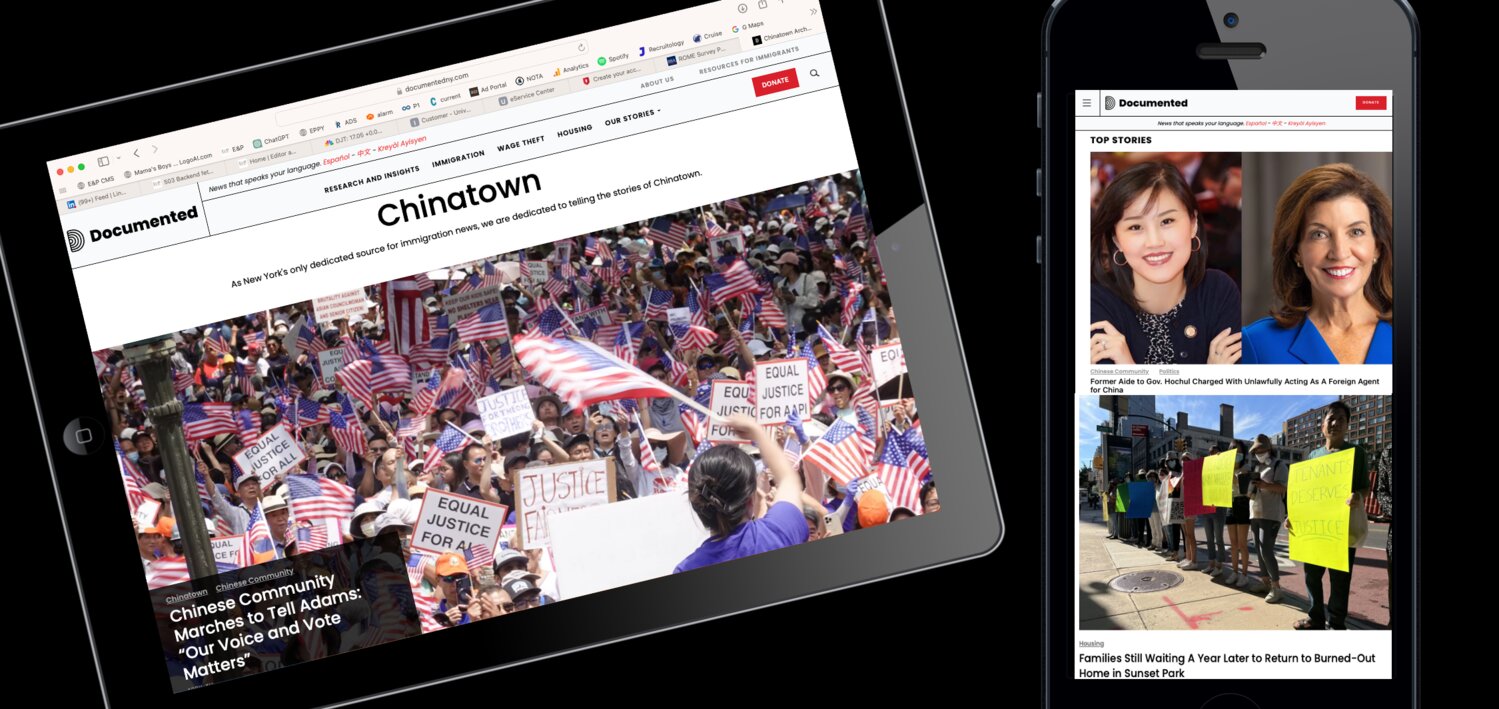

April Xu is a reporter who covers New York's Chinese community for Documented NYC. Early in her career at the organization, she made a simple observation: the immigrants she was trying to reach were on WeChat, but her newsroom wasn't.

This might seem like an obvious problem to solve. Just start posting on WeChat, right? But there's a complication. WeChat isn't open to casual accounts from anyone. The platform requires a Chinese phone number to verify accounts. Setting up an official newsroom presence on WeChat requires actual investment in Chinese infrastructure, not just a new account.

For most newsrooms, that barrier would be prohibitive. It's easier to post on platforms that already exist in their workflow. It's easier to use tools that integrate with their content management systems. It's easier to pursue reach on platforms that other newsrooms are using.

But Xu recognized something important: if she wanted to serve Chinese-speaking New Yorkers, she had to meet them where they actually were. So Documented invested in building a WeChat presence. They created an official channel called 纽约移民记事网Documented, which translates to "New York Immigrant Chronicle."

The channel looks nothing like a traditional news feed. It combines actual journalism with public service information. Yes, there are stories about healthcare and immigration enforcement. But there are also listings for toy giveaways, locations of free grocery distribution, affordable housing lottery information, and information about local events.

Readers can contact reporters directly. But they're not just sending tips, which is what journalists expect from reader communication. They're asking essential survival questions: Where can I find free English classes? What should I expect at my immigration court date? Can I travel outside the United States if I have a green card?

Xu is personally part of over 50 WeChat group chats that serve New York's Chinese community. Each group can have up to 500 members. She also manages a smaller Documented reader group. This isn't passive broadcasting. She's actively participating in communities, answering questions, building relationships. The time investment is significant. But the trust that develops is impossible to replicate on traditional social media platforms.

Here's where this gets interesting: Xu doesn't need to go viral. She doesn't need millions of impressions. She needs to reach the specific people in her community who will actually use the information she's sharing. A post about affordable housing that reaches 500 people in a specific WeChat group might be worth more to those 500 people than a housing story that reaches 50,000 people on Instagram but gets lost in the algorithm within hours.

The model flips traditional media metrics on their head. Instead of optimizing for reach, you optimize for relevance. Instead of measuring success by impressions, you measure it by whether the information actually changed someone's behavior.

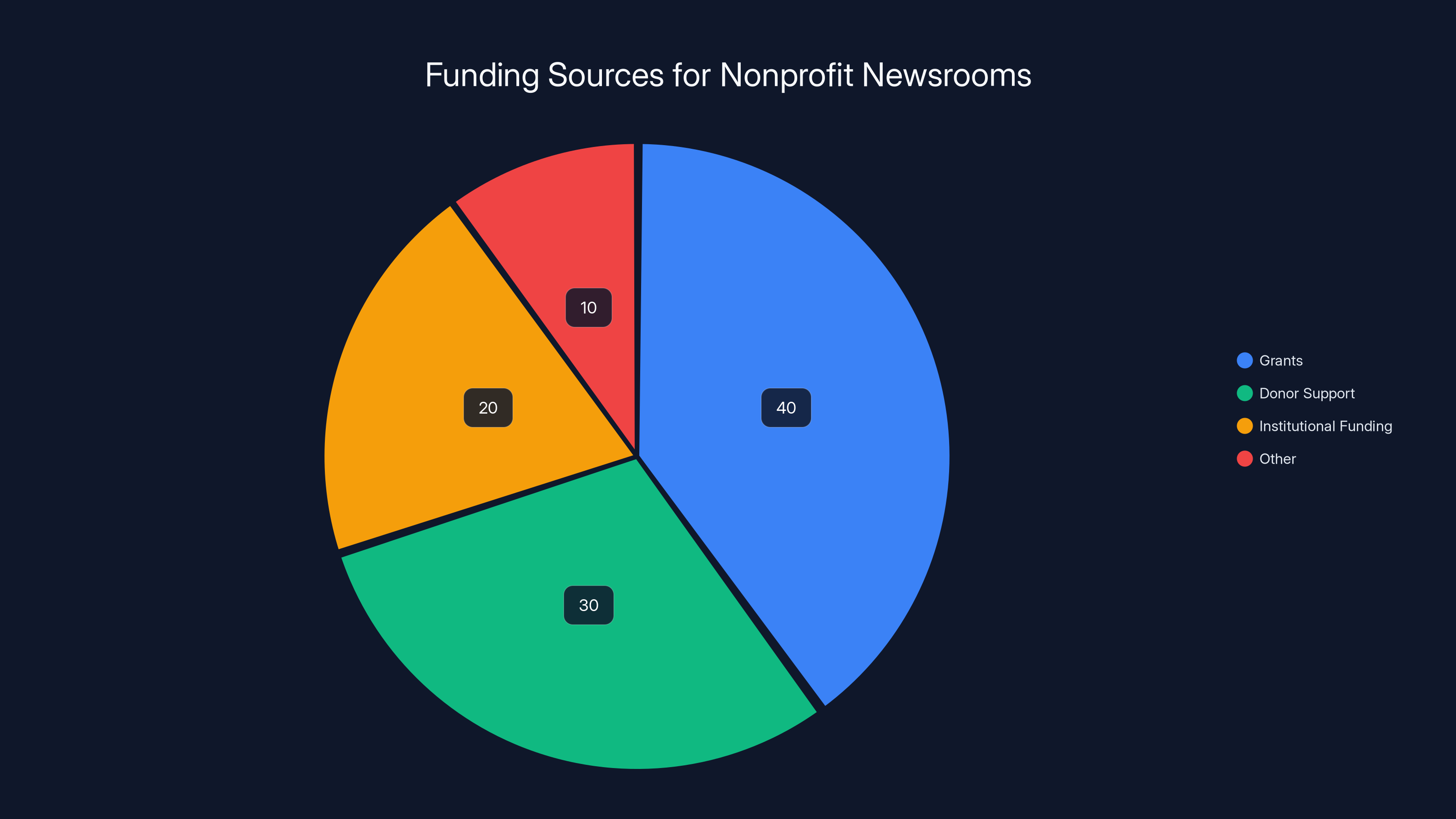

Nonprofit newsrooms like Documented NYC rely on a mix of grants, donor support, and institutional funding, with grants being the largest source. (Estimated data)

WhatsApp as a Gateway to Spanish-Speaking Communities

For Spanish-speaking immigrant communities in the United States, WhatsApp plays a similar role to WeChat for Chinese immigrants. It's ubiquitous. It's trusted. It's where communication happens.

The United States has a Spanish-speaking population of over 41 million people, and while not all of them are immigrants, the vast majority of Spanish speakers in working-class and immigrant-heavy neighborhoods use WhatsApp as their primary messaging platform. Unlike WeChat, WhatsApp isn't mysterious to English-speaking Americans. Many people with international connections use it. But it operates very differently in immigrant communities than it does in mainstream American usage.

In immigrant neighborhoods, WhatsApp group chats function like modern versions of community radio. Someone posts information to a neighborhood group chat. That information gets shared forward. People ask clarifying questions. Within an hour, the information has spread through multiple networks. If that information comes from a trusted source—a local reporter, a community organization, a local official—it carries weight. If it comes from an unknown source, people are skeptical.

For newsrooms trying to reach Spanish-speaking immigrant communities, WhatsApp creates both an opportunity and a distinct set of challenges. The opportunity is direct access to engaged communities. But the challenge is that WhatsApp is designed for personal communication, not broadcasting. It doesn't have a built-in publishing platform. It doesn't have analytics. It doesn't have the infrastructure that modern newsrooms expect.

This forces newsrooms to think differently about content. The content that performs on WhatsApp is different from content optimized for Instagram or TikTok. It's usually shorter. It's more practical. It links to more detailed information rather than trying to tell the whole story in a single post. It often raises questions that readers can then ask in the group chat, creating ongoing conversation rather than passive consumption.

Some newsrooms have experimented with WhatsApp business accounts, which are specifically designed for organizations to communicate with customers and communities. These accounts can be linked to automation tools. They can handle multiple conversations at once. They can be integrated with customer service workflows.

But Documented NYC's approach is more direct. They use WhatsApp to distribute information, but they also personally engage with readers. Reporters answer questions. They build relationships. It's labor-intensive. It's not scalable in the traditional sense. But it's also the only way to actually serve a community instead of broadcasting at it.

The practical limitations of WhatsApp also create interesting editorial choices. A story about immigration enforcement can't just drop a news alert and disappear. If you're sending it to a community WhatsApp group, you need to be prepared to answer follow-up questions. What does this mean for green card holders? What should people do if they encounter an enforcement action? Where can they find legal help?

These are the questions that separate news that's actually useful from news that's just information.

Nextdoor and Neighborhood-Specific News Distribution

Nextdoor is the platform that most mainstream newsrooms probably know about, at least by reputation. It's an app designed for neighborhood communication. You sign up for your specific neighborhood. You can see posts from your neighbors. You can ask for recommendations. You can report local issues.

In mainstream American usage, Nextdoor has a particular reputation. It's where people complain about parking. It's where someone asks about a loud noise at 2 AM. It's where neighborhood watch culture sometimes goes overboard. The journalism industry has mostly treated Nextdoor as a curiosity—a place where neighborhood gossip happens, not a serious news distribution platform.

But for Caribbean immigrant communities in New York, Nextdoor functions quite differently. It's a neighborhood communication tool, yes. But it's also where essential information gets shared. It's where someone asks about affordable dentists who speak Spanish or Haitian Creole. It's where people share information about free services. It's where community members alert each other about local changes that might affect them.

For newsrooms serving Caribbean immigrant communities, Nextdoor presents a specific opportunity: it's already geographically bounded. The neighborhoods where Caribbean immigrants are concentrated in New York are specific and identifiable. Documenting news and information for those neighborhoods, distributed directly through Nextdoor, reaches exactly the right people.

It's news as neighborhood service. A story about a new affordable housing lottery isn't interesting to someone in Manhattan if the housing is in specific neighborhoods in Brooklyn. But it's urgently relevant to someone in that exact neighborhood. Nextdoor allows for that level of geographic precision that traditional news platforms don't.

The challenge with Nextdoor is similar to WhatsApp: it's not designed for media organizations. It's designed for peer-to-peer communication. This means that newsrooms using Nextdoor need to participate as community members, not as broadcast channels. They share information. They answer questions. They engage in conversations.

For reporters who are part of the communities they cover, this isn't artificial. Documented's reporters aren't distant institutions broadcasting to immigrant communities. They're part of those communities. They have their own addresses on Nextdoor. They have neighbors. They're already participating in neighborhood life. Using Nextdoor to share journalistic information is just an extension of being a community member.

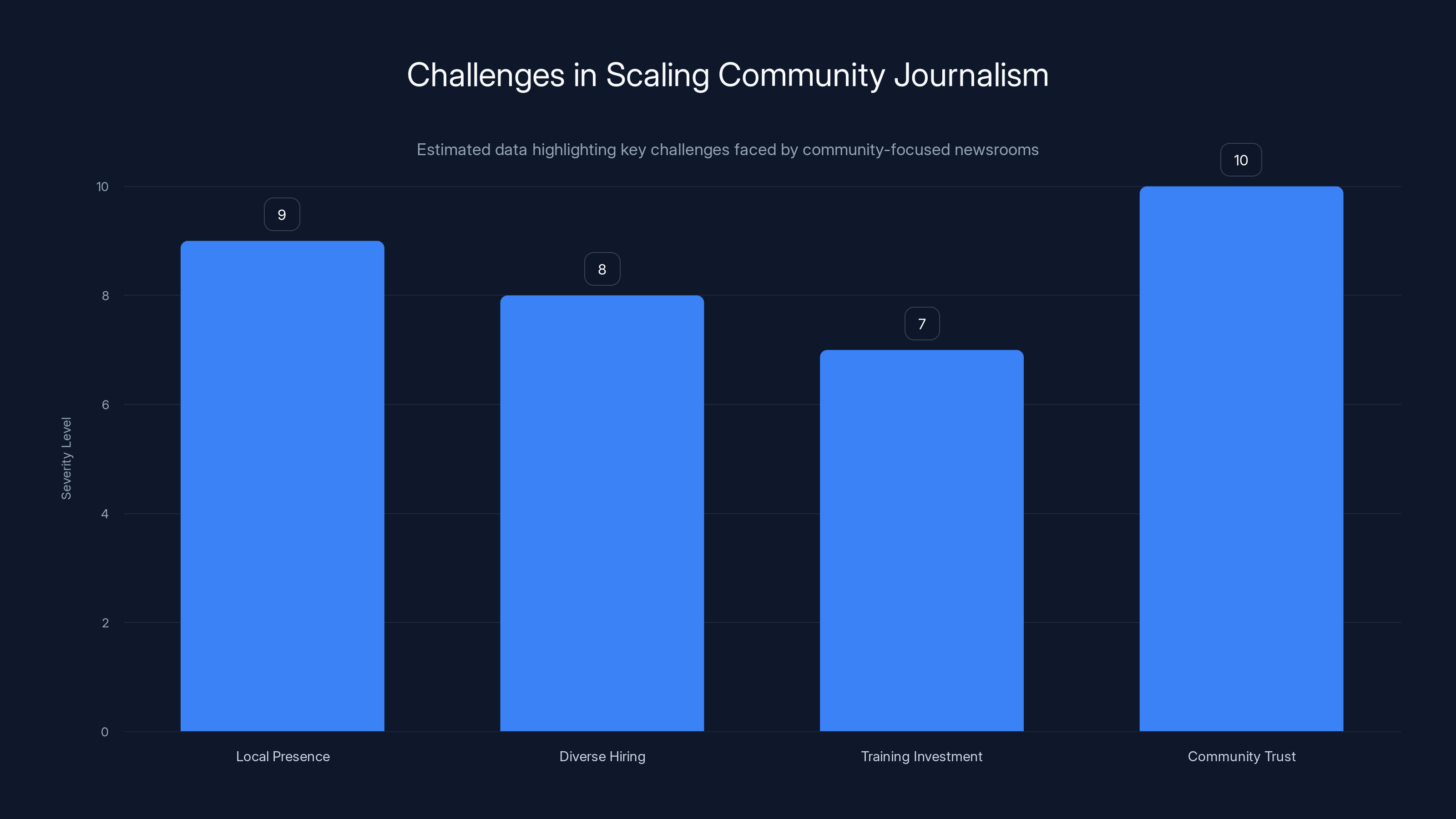

Community journalism faces significant challenges in scaling, particularly due to the need for local presence and building community trust. (Estimated data)

The Structural Problem With Platform Dependence

For the last 15 years, American newsrooms have become increasingly dependent on third-party platforms to reach their audiences. This wasn't a deliberate strategy—it just happened. Journalists and publishers realized that Facebook could drive traffic more efficiently than email newsletters. TikTok could reach younger audiences more effectively than traditional media channels. Instagram could build community more easily than comments on a website.

The logic made sense. Why invest in your own distribution infrastructure when platforms with billions of users could do it for you? Why build a newsletter when you could just post to Facebook and let their algorithm do the work? Why worry about your own reach when TikTok's algorithm could make your content go viral?

The problem, which should have been obvious but somehow wasn't until it became catastrophic, is that you don't control platforms you don't own. Facebook can change its algorithm. TikTok can be banned. Instagram can shift its strategy from discovery to friends-and-family content. YouTube can change its monetization structure. When you depend entirely on someone else's platform for your audience, you're dependent on their business decisions, their political pressures, their shifting priorities.

This became painfully clear in 2024 and 2025 as Meta's algorithm changes and TikTok's existential uncertainty wreaked havoc on newsroom traffic. Publishers who had spent a decade optimizing for Facebook's algorithm suddenly found their reach collapsing. Newsrooms that had built TikTok audiences faced genuine uncertainty about whether that platform would continue to exist.

For immigrant communities, the problem is even more acute. Most immigrant communities aren't using Meta's platforms the same way English-speaking Americans are. They've built their own infrastructure. They've created their own trusted networks. They're sharing information in ways that traditional news platforms can't reach.

Documented NYC's approach inverts the traditional dependence. Instead of depending on platforms that prioritize reach, they're using platforms that immigrant communities have already built for themselves. Instead of asking immigrants to come to the news platform, they're going to the communication platforms that immigrants are already using.

This isn't just more effective. It's also more resilient. If Meta changes its algorithm, Documented's reach on Meta is affected. But their reach on WeChat? That depends on the relationships they've built with community members, not on platform algorithms. If WhatsApp changes its interface, the core communication still works. If Nextdoor shifts its business model, the neighborhoods where community members live don't change.

The strategy acknowledges a fundamental truth: the most important media infrastructure for immigrant communities isn't owned by Silicon Valley tech companies. It's the communication networks that communities have built for themselves.

Language Accessibility as Fundamental Journalism

Documented NYC publishes in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Haitian Creole. This isn't because the organization is particularly wealthy or well-resourced. It's because language accessibility is understood as fundamental to the mission, not an optional add-on.

This creates practical challenges. It means hiring reporters who speak these languages. It means translating or creating original content in each language. It means understanding cultural contexts specific to each community, not just translating English text into other languages.

Here's a concrete example of why this matters: a story about how to apply for a green card isn't the same story in English and Spanish. The English version might assume familiarity with American bureaucracy that a recently arrived immigrant wouldn't have. The Spanish version might include details about which countries use which forms, based on the specific nationalities of the Spanish-speaking community. The Chinese version might need to address specific visa categories and policies that are particularly relevant to Chinese immigrants.

Just translating English articles isn't sufficient. You need reporters who understand the specific communities, the specific experiences, the specific questions that immigrant populations are asking.

Documented's approach is to hire reporters from the communities they cover. April Xu, who covers New York's Chinese community, is part of that community. Her fluency isn't just linguistic. It's cultural. She knows the community structures. She participates in them. She understands how information actually flows through the community.

This is labor-intensive. It's expensive. It's not scalable in the way that traditional media organizations think about scale. You can't write one English story and have it translated and distributed in four languages. You need reporters who are genuinely part of each community, reporting on stories that matter to that community, in languages they actually speak.

The payoff is that the journalism is actually useful. A story about immigration enforcement isn't an abstract news item. It's information that could affect whether someone gets in their car tomorrow, whether they trust the authorities, whether they know their rights.

That level of specificity and utility is only possible if you're actually embedded in the community. A reporter who's reading about Chinese immigrants online can't understand what it feels like to be part of the WeChat ecosystem. A reporter who doesn't speak Haitian Creole can't understand how community members in that language are discussing immigration policy.

Language accessibility means that journalism isn't just translated. It's reimagined for each community. It's built around what each community actually needs to know.

WeChat and WhatsApp are leading platforms for immigrant communities, with WeChat being particularly vital for Chinese immigrants. Estimated data based on typical usage patterns.

Building Trust in Communities, Not Metrics

When you're a reporter at a mainstream newsroom, success is usually measured in metrics. How many page views did your story get? How many shares on social media? What's your engagement rate? Did the story trend?

These metrics drive editorial decisions. They influence how stories are framed, where they're promoted, what follow-up coverage gets done. An editor sees that a particular story got 50,000 views and 2,000 shares. That's success. That's what you do more of.

But these metrics are fundamentally misaligned with serving immigrant communities. A story about affordable housing options that reaches 500 people who desperately need housing information is more successful than a story about a celebrity that reaches 100,000 people who are just scrolling for entertainment.

Building trust in communities requires a completely different approach. It requires showing up consistently. It requires answering questions over and over again, even if you've already answered them on the website. It requires being accessible in ways that don't scale—actual human reporters engaging with actual community members.

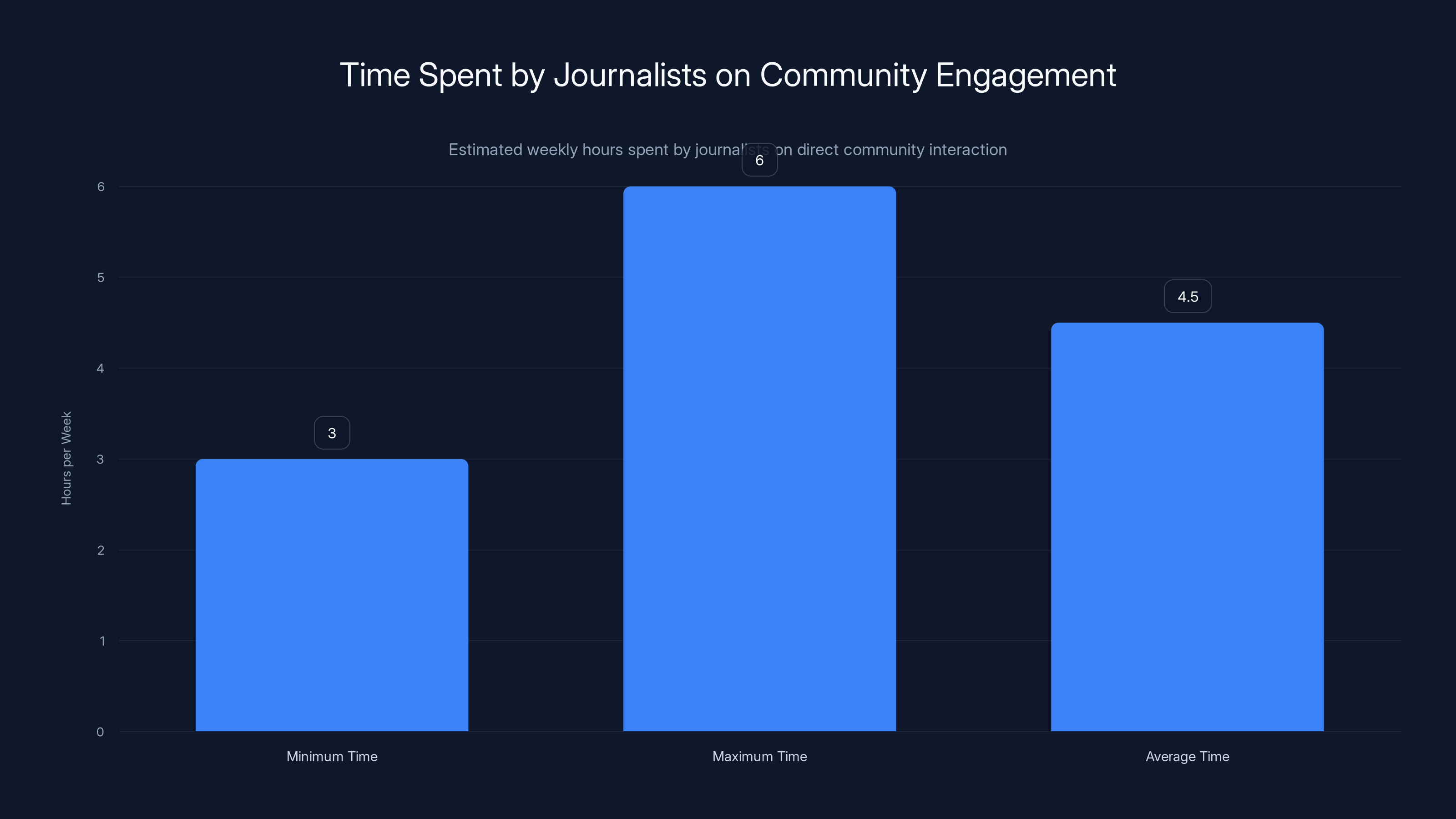

Documented reports that their journalists spend between three and six hours every week personally answering reader questions. These aren't press inquiries. These are community members asking for help. And the reporters are answering them. What does this tax form mean? Where can I find a lawyer? Is it safe to travel with my green card?

This approach is expensive. It's not efficient. A reporter answering questions for three to six hours every week isn't writing stories that might go viral. They're not building their own personal brand. They're not accumulating bylines and resumé credentials.

But they're building something more valuable: trust. When a community member in a WeChat group asks a question and gets answered by a reporter they know from Documented, they start thinking of that reporter as a resource. When someone from the community asks their neighbors about how to handle an immigration issue and gets referred to Documented because people know that organization has real information, the organization becomes the trusted resource.

This trust becomes the metric that actually matters. If a reporter's question thread on WeChat gets 30 responses, that's not measured by any traditional news analytics. But those 30 responses represent 30 community members engaging with journalism, asking questions, getting answers. That's success in a way that 30,000 passive readers never is.

The challenge is that this kind of success isn't rewarded by traditional media industry incentives. A journalist who answers a hundred questions for a thousand community members isn't going to have a flashy portfolio to show for it. Their work doesn't get covered by media trade publications. They don't get invited to speak at journalism conferences. Their value is internal and community-specific, not external and industry-wide.

But for immigrant communities, this is exactly what journalism needs to be. It needs to be embedded in community life, answering questions that people have, accessible in the languages they speak, on the platforms where they actually communicate.

The Economics of Community-Focused Journalism

Documented NYC is a nonprofit newsroom. This is important, because the nonprofit model is basically the only way that community-focused journalism like this can actually be sustainable.

Here's why: immigrant community journalism doesn't generate the advertising revenue that mainstream newsrooms depend on. If you're publishing in Spanish, Chinese, and Haitian Creole, your potential advertising market is more limited. If you're distributing on WeChat instead of your own website, you can't track clicks to display ads. If you're answering individual questions instead of publishing stories that drive traffic, you're not building the audience size that attracts premium advertising.

A for-profit newsroom operating under traditional media economics couldn't sustain this approach. They'd need to optimize for reach, traffic, advertising. They'd need to figure out how to monetize their content. They'd need to cut the reporter time spent answering community questions and redirect it to story production.

The nonprofit model allows for a different set of economics. Instead of relying on advertising or subscription revenue, nonprofit newsrooms rely on grants, donor support, and institutional funding. This doesn't solve the financial challenges—nonprofit newsrooms are perpetually struggling for funding. But it does allow for a mission-driven approach that doesn't require immediate revenue generation.

Documented NYC's funding model probably includes grants from journalism funding organizations, foundation support for immigration coverage, and individual donors. The organization can make editorial decisions based on what their communities need, not what drives clicks or advertising revenue.

This raises an important question: is nonprofit journalism the only sustainable model for serving immigrant communities? Or can this approach work within traditional for-profit newsrooms?

Some large news organizations have experimented with community-focused approaches. The New York Times has made investments in Spanish-language coverage. NPR has expanded its Spanish-language programming. But these initiatives operate within the constraints of for-profit media economics. They need to generate some form of revenue. They need to justify their existence within the larger organization's budget.

Documented's approach suggests that there's a fundamental mismatch between traditional media economics and immigrant community journalism. The most valuable journalism for these communities doesn't generate the metrics or revenue that traditional news organizations depend on. It's not viral. It doesn't drive mass traffic. It can't easily be monetized.

But it's also critically important. When immigration enforcement is happening, when community members need to know their rights, when crucial information is available only in English on platforms that immigrants don't use, the gap between what communities need and what mainstream media provides becomes painfully obvious.

The question for the journalism industry isn't whether this kind of work is valuable. It clearly is. The question is how to sustain it. The nonprofit model provides one answer. Institutional support from large news organizations could provide another. Public media funding could provide another. What's clear is that traditional for-profit news economics aren't sufficient.

Immigrant communities in the U.S. predominantly use platforms like WeChat and WhatsApp for news, highlighting a disconnect with mainstream media. (Estimated data)

How Reporters Actually Spend Their Time in Communities

When Ethar El-Katatney, Documented's editor-in-chief, describes the organization's approach, she emphasizes that reporters are "encouraged to spend time in the communities they cover." This sounds nice as a general principle. But what does it actually mean in practice?

For April Xu, it means being part of WeChat groups that serve her community. She's in over 50 of them. Some are neighborhood groups. Some are professional networks. Some are cultural and religious organizations. She participates actively—not as a journalist conducting interviews, but as a community member.

This is important. She's not using these groups to extract information from the community. She's actually part of the groups. She sees what people are discussing. She understands what questions people are asking. She knows what concerns are circulating through the network.

When she identifies a story that needs to be told, she has context. She knows who to talk to. She understands the community dynamics. She can anticipate questions that readers will have. She can provide answers that actually matter to the community.

But this also takes time. You can't be in 50 active group chats without spending significant time engaging with them. The three to six hours that reporters spend answering community questions? That's not time spent on traditional journalism tasks. It's time spent on community relationship building, knowledge gathering, and service.

For reporters coming from traditional journalism backgrounds, this can feel inefficient. You're not producing a consistent volume of published stories. You're not hitting daily or weekly publishing deadlines. You're not measuring your productivity by byline count.

But the approach is built on a different understanding of what journalism is. It's not just the stories that get published. It's the knowledge that gets built. It's the relationships that get developed. It's the understanding of the community that informs everything the journalist does.

When Xu publishes a story about a new housing lottery for low-income families, she can explain exactly what documents families will need because she's heard from families in her WeChat groups about what documents they're struggling to find. When she publishes a guide about immigration court procedures, she can anticipate confusion points because she's been answering questions about those procedures for months in her community groups.

This depth of local knowledge is increasingly rare in journalism. Traditional reporters often work on beat systems where they cover an area from the outside, learning about it primarily through official sources and story research. They might be embedded in the community in some ways, but there's a fundamental separation between their professional role and their community membership.

Xu doesn't have that separation. She's part of the community. Her professional work is an extension of her community membership, not something separate from it.

This requires hiring differently. Documented hires reporters who are from the communities they cover. They're not journalists assigned to cover an unfamiliar community. They're community members who have become journalists. That's a fundamental difference in how you approach the work.

Measuring Impact Beyond Metrics

Traditional journalism measures impact through metrics: traffic, engagement, reach, shares. These metrics are imperfect. They measure attention, not actual impact. A story can get millions of views and not change anyone's behavior. A story can reach a small audience and profoundly affect the lives of the people who read it.

For immigrant community journalism, the metrics that matter are different. They're harder to measure, but they're also more meaningful.

Has someone used information from a Documented story to understand their rights in an immigration situation? That's impact. Did a family use housing lottery information to apply for affordable housing? That's impact. Did someone who was worried about traveling with a green card find clarity from an explainer and make a decision they felt confident about? That's impact.

These kinds of impacts don't show up in web analytics. They don't show up in social media engagement. They show up in conversations. In follow-up questions from community members. In people referring others to Documented because they found the information helpful. In community members expressing gratitude when a reporter answers a question that mattered to them.

El-Katatney talks about the organization's approach as creating "actionable" information. This is the key metric: does the information actually help people take action in their lives? Not just does it provide facts, but does it provide facts in a form and context that people can actually use to make decisions?

This requires a different approach to journalism. It means explaining not just what happened, but what it means for the specific communities you're serving. It means providing context about how policies actually affect daily life. It means connecting readers to resources, not just reporting on issues.

A traditional news story about immigration enforcement might report: "ICE agents arrested 150 people at a construction site yesterday." That's factual. But what does it mean for someone who works in construction and is now worried about going to work? A Documented story would answer that: "Here's what ICE is doing, here's what your rights are, here's where to find legal help, here's how to prepare your family if you're detained, here's what not to say to authorities."

The second approach is journalism as information for survival, not journalism as reporting on news. And for immigrant communities facing intensive immigration enforcement, journalism as survival information is what actually matters.

Journalists at Documented spend between 3 to 6 hours weekly on direct community engagement, fostering trust over viral content. Estimated data.

Scaling Community Journalism Without Losing It

One of the biggest challenges for Documented and other community-focused newsrooms is growth and sustainability. If the model depends on reporters being embedded in communities, spending 20% of their time answering community questions, participating actively in community networks, then it's not easily scalable.

A traditional newsroom scales by automating. You build systems. You use templates. You optimize for efficiency. A reporter produces more stories. You hire more reporters. You expand coverage. You grow the operation.

But community-focused journalism doesn't scale the same way. You can't automate trust. You can't template relationship building. You can't hire journalists from a community that doesn't have journalists.

Documented has solved this partially by hiring reporters who are from the communities they cover. This means that the reporter's own presence in community networks is part of their qualification for the job, not something they have to learn. But it also means that growth requires finding more people from immigrant communities who have journalism skills or potential.

This is a real constraint. The United States doesn't have a huge pipeline of journalists from immigrant communities. Journalism as a profession is not particularly diverse. Immigrant communities have even less representation in journalism than the general population. Finding reporters who are both from immigrant communities and have journalism experience or aptitude is genuinely difficult.

One approach that some newsrooms have tried is investing in training and development. Hire smart people from communities you want to serve. Train them in journalism. Invest in their development. This works, but it requires different hiring and HR approaches than traditional newsrooms use.

Another constraint is that this kind of journalism fundamentally depends on local presence. You can't cover a community well from a distance. You can't build trust through a remote arrangement. This limits the geographic areas that a single newsroom can effectively serve, unless they're willing to hire a distributed team of local journalists in different regions.

Documented operates primarily in New York, which is a reasonable geographic boundary for a local nonprofit newsroom. Expanding to other cities would require expanding to multiple newsrooms or building a distributed team with local presence in each area.

This raises the question of whether this model could work at a larger scale. Could a national or regional nonprofit newsroom operate this way, with community-focused journalism for immigrant populations in multiple cities? Possibly. But it would require significant resources and a commitment to hiring journalists from immigrant communities in each area.

The challenge is that the value of this journalism is local and specific. A story about affordable housing in New York isn't useful for someone living in Los Angeles. A guide about navigating immigration court in New York doesn't apply to someone in Houston. This creates a natural limitation on how much centralized production and distribution can work.

The Role of AI and Automation in Immigrant Community News

Here's an interesting question for newsrooms: where does AI and automation fit into community-focused immigrant journalism?

Traditional newsrooms have started experimenting with AI for automated content generation, headline optimization, content distribution, and audience analytics. These tools promise efficiency gains. They promise to let journalists focus on reporting while automation handles routine tasks.

But there's a fundamental mismatch between what AI tools are designed for and what immigrant community journalism actually needs.

AI is good at scaling commodified tasks. It can write simple news stories from data. It can write multiple versions of a headline and test which performs better. It can identify trending topics and suggest stories. It can analyze audience data and recommend what to publish.

But immigrant community journalism isn't about scaling commodified tasks. It's about building specific relationships with specific communities. It's about understanding nuanced cultural and linguistic contexts. It's about answering individual questions from community members. These are all areas where AI can be helpful in limited ways, but can't actually replace the core work.

There are places where AI tools could be genuinely useful. Translation tools could help with content distribution across multiple languages. Automated systems could help handle routine inquiries ("Where do I find legal help?") and escalate complex questions to human reporters. Data tools could help identify trends in what questions community members are asking.

But the core work—the reporting, the relationships, the community embedding—this can't be automated. And importantly, it shouldn't be. The value of Documented's approach is precisely that it's human-centered, relationship-based, community-embedded. An AI system trying to replace that would destroy the thing that makes it work.

Platforms like Runable that enable content generation and workflow automation could potentially help by allowing reporters to focus more on community engagement and less on routine content creation. A reporter could spend less time writing routine FAQ updates or basic how-to guides and more time on in-depth reporting and community engagement. But this only works if the automation tools are used as force multipliers for human journalists, not replacements for them.

The real opportunity for technology in this space isn't about scaling the journalism itself. It's about scaling the logistics: How do you distribute information to community members in multiple languages? How do you manage conversations across multiple platforms? How do you track and respond to community questions? These operational challenges could potentially be addressed with better tools.

But the journalism itself—the reporting, the relationship building, the community understanding—this remains fundamentally human work.

The Future of News for Immigrant Communities

We're in a moment where immigration is one of the most contentious political issues in the United States. Policies are changing rapidly. Immigration enforcement is happening at scale. Federal and state governments are using data to identify and apprehend immigrants. Communities are navigating unprecedented uncertainty.

In this context, the need for credible, accessible, community-focused information about immigration has never been higher. And the failure of mainstream newsrooms to provide that information has never been more apparent.

Documented's approach—meeting communities where they are, in the languages they speak, on the platforms they use—is one model for addressing this gap. It's not the only model. But it's one that's proven effective.

The bigger question is whether the journalism industry will actually invest in this kind of work. It's not economically efficient. It doesn't generate viral reach. It doesn't fit neatly into traditional newsroom structures. But it serves a critical public function: making sure that information is actually accessible to the people who need it.

One possibility is that we'll see more nonprofit newsrooms emerging to serve specific communities. Some organizations are already experimenting with this: Spanish-language nonprofit newsrooms, newsrooms focused on specific immigrant populations, newsrooms focused on specific geographic areas with high immigrant populations.

Another possibility is that larger news organizations will invest in these kinds of community-focused approaches as part of their editorial missions. The New York Times has significant Spanish-language coverage, for example, though it's primarily distributed through its main platforms, not through community-specific platforms like WeChat or WhatsApp.

A third possibility is that immigrant communities will continue to rely on informal information networks and community organizations for their news, rather than formal news organizations. This is actually already happening. Many immigrant communities get their most trusted information from community leaders, religious organizations, mutual aid networks, and trusted peers, not from news organizations at all.

The challenge for journalism is that formal news organizations could add significant value in these informal networks. A reporter who is trusted in the community, distributing information through community platforms, is valuable precisely because they're operating within the informal network, not imposing external structure on it.

What's clear is that the traditional model of news distribution—publishing on your own website and hoping people find it through social media algorithms—is fundamentally insufficient for immigrant communities. And that failure reflects a broader failure of journalism to recognize that different communities have different information needs, different languages, and different platforms where they actually get information.

The future of news for immigrant communities doesn't depend on technology innovation or business model innovation. It depends on journalism that's actually built for those communities, that serves their needs, that operates in the spaces where they already are. Documented is demonstrating that this kind of journalism is possible. The question is whether the industry will invest in making it widespread.

Lessons From Community-First News Distribution

If you're working in journalism—whether at a nonprofit, a traditional newsroom, or a startup—there are specific lessons from Documented's approach that apply to your work.

First, understand the actual information ecosystem of your audience. Don't assume. Don't make guesses based on industry trends. Actually investigate where your audience gets information, what languages they speak, what platforms they use. This might be WeChat. It might be local Telegram groups. It might be Reddit communities. It might be email lists. It might be traditional social media. But find out what's actually true for your specific audience.

Second, go to where your audience is. Don't expect them to come to you. Don't expect that publishing on your website or main social media account will reach everyone who needs information. If your audience is on a platform you're not using, that's a signal that you need to expand your distribution, not a reason to ignore that audience.

Third, understand that different communities have different information needs. A story about housing might be relevant to everyone, but the relevant details are different for undocumented immigrants versus citizens versus permanent residents. The relevant resources are different. The relevant context is different. You need reporting that's specific to these different communities, not one-size-fits-all journalism.

Fourth, invest in language accessibility as fundamental journalism, not as an add-on. This probably means hiring people who speak the languages of your communities. It might mean translating content. It definitely means understanding that language accessibility isn't just about translation—it's about cultural context, specific examples, and understanding what different communities actually need to know.

Fifth, measure success by impact, not by metrics. How many people actually used this information? How did it affect their behavior? Did they make a decision that mattered to them? These are harder to measure than page views or shares, but they're what actually matters.

Sixth, invest in relationship building with communities. This is slower than broadcasting. It requires time and genuine commitment. But it creates the foundation for all the other work. It means reporters are part of communities, not external observers reporting on them.

Seventh, understand that this kind of journalism requires different economics than traditional news. You probably can't monetize it through advertising or traditional subscription models. You need foundation support, donor support, grants, or some other form of institutional funding that allows you to prioritize serving communities over generating revenue.

None of these lessons are revolutionary. They're pretty straightforward common sense. But implementing them requires resisting powerful incentives in the journalism industry—incentives toward scale, toward viral reach, toward metrics-driven decision making, toward centralized content production.

Documented is successful precisely because they've resisted those incentives and focused instead on serving their communities in the ways those communities actually need to be served.

Conclusion: The Immigrant Information Gap and What Happens Next

We live in an era of unprecedented information abundance. Anyone with internet access can find information about almost anything. Search engines, social media platforms, AI assistants—there's more information available than there's ever been.

But that information abundance is distributed unequally. It's concentrated in English. It's optimized for engagement and virality, not for actual community needs. It's distributed through platforms designed for attention capture, not for community communication. It's produced by institutions that often don't understand the specific contexts and needs of immigrant communities.

For immigrant communities in the United States, this creates a genuine information crisis. Government policies are changing rapidly, affecting people's daily lives. Law enforcement actions have consequences for families and communities. Government benefits, housing programs, education systems—all of these require navigation and information. But the information that's available through mainstream channels is often not accessible, not relevant, and not useful.

Documented NYC represents one response to this crisis. By understanding how immigrant communities actually get information, by meeting them where they are, by serving their specific needs in their preferred languages and platforms, they've created a model of journalism that actually serves the communities they work with.

But Documented can only do this work in New York, and only with the specific communities where they have reporters embedded in the community. The model doesn't scale automatically to other places or other communities. And the journalism industry as a whole hasn't invested in replicating this approach in other communities or geographic areas.

So the question that remains is: what happens to the thousands of other immigrant communities across the United States who don't have access to journalism like Documented provides? What happens to immigrant communities in areas where there's no nonprofit newsroom focused on serving them? What happens to immigrants who need information but can't find it in their language, on their platforms, from sources they trust?

They navigate the system as best they can. They rely on informal information networks. They get information from community organizations, religious institutions, mutual aid networks, and trusted peers. Some of this information is good. Some of it is dangerously wrong. But in the absence of accessible, credible, community-focused journalism, these informal networks are what people turn to.

The solution isn't complicated. It requires investment in journalism that's built for communities, not for metrics. It requires hiring journalists from immigrant communities. It requires distributing information through the platforms where communities actually gather. It requires understanding that different communities have different needs and different ways of getting information.

It's possible. Documented is proof of that. But it requires the journalism industry to make fundamentally different choices about what news is for, who it should serve, and how success should be measured.

In a moment when immigrant communities are facing unprecedented uncertainty and policy changes, when credible, accessible information could genuinely affect people's lives and safety, the stakes for getting this right are enormous. The question is whether journalism will rise to meet that challenge.

FAQ

What is community-focused immigrant journalism?

Community-focused immigrant journalism is reporting and news distribution designed specifically for immigrant populations, delivered in languages they speak and on platforms they actually use. Rather than publishing in English on traditional news websites, this approach recognizes that different communities have different information needs and different ways of accessing information. It prioritizes actionable information that helps community members navigate government systems, access services, and understand policies that affect their lives.

How do newsrooms like Documented reach immigrant communities effectively?

Documented reaches immigrant communities by embedding reporters within those communities, distributing information through the platforms where communities actually communicate (WeChat for Chinese speakers, WhatsApp for Spanish speakers, Nextdoor for neighborhood-specific communities), and hiring journalists from the communities they serve. Rather than broadcasting information widely, they focus on building relationships, answering individual community questions, and providing culturally specific information that actually matters to people's daily lives.

Why is WeChat important for reaching Chinese immigrants?

WeChat functions as essential infrastructure for Chinese immigrants in the United States, combining communication, financial services, shopping, and news all in one app. It operates as a semi-closed network where information spreads through trusted relationships rather than public algorithms. For newsrooms, this means reaching Chinese-speaking immigrants where they already spend significant time and with audiences built on relationships and trust rather than algorithmic reach.

What does language accessibility mean beyond translation?

Language accessibility means more than just translating English-language content into other languages. It means hiring reporters who understand the specific cultural contexts of immigrant communities, can identify stories that matter to those communities, and can provide information that's relevant to their specific situations. A story about housing, immigration court, or government services needs different context and different resources depending on who's reading it and what their specific circumstances are.

How do community-focused newsrooms measure success without traditional metrics?

Rather than measuring success by page views, shares, or viral reach, community-focused newsrooms measure impact by whether information actually changed people's behavior or helped them make important decisions. This includes tracking community member feedback, counting individual questions answered by reporters, observing whether people use provided resources, and gathering qualitative feedback about whether information was actually helpful. Impact is measured in relationships and trust built, not in aggregate reach.

Why can't traditional for-profit newsrooms sustain this approach?

Traditional for-profit newsrooms depend on advertising revenue or subscriptions, which require either large audiences or premium subscribers. Community-focused immigrant journalism doesn't generate large audiences on traditional platforms, and it doesn't lend itself well to paywalls or advertising. The nonprofit model allows newsrooms like Documented to prioritize serving communities over generating revenue, making sustainable mission-focused journalism possible.

Could AI tools help community-focused newsrooms scale their work?

AI and automation tools could potentially help with operational challenges like translation, content distribution, handling routine inquiries, and audience analytics. However, the core work of community-focused journalism—building relationships, understanding specific community needs, providing culturally specific reporting—cannot and should not be automated. Technology can be a force multiplier for human journalists, but it cannot replace the fundamental human work of being embedded in communities and serving them with credible, relevant information.

What languages does Documented NYC publish in?

Documented NYC publishes in English, Spanish, Chinese (primarily Mandarin), and Haitian Creole. Each language publication has dedicated reporters who are part of those communities, ensuring that reporting reflects the specific needs and contexts of each community rather than being simple translations of English-language content.

How much time do Documented reporters spend on community engagement?

Documented reporters spend between three and six hours every week personally answering reader questions in community platforms. This is in addition to their regular reporting work. The time investment reflects the organization's understanding that relationship building and direct community service are essential parts of their journalism, not distractions from it.

Is there a model for expanding community-focused journalism to other cities and communities?

While Documented has primarily focused on New York, the model could theoretically expand to other cities through hiring local reporters embedded in immigrant communities in those areas. However, this would require significant resources, a commitment to hiring journalists from immigrant communities (which requires different hiring practices than traditional newsrooms), and recognition that local, community-specific reporting is more valuable than centralized, geographic-scale reporting. Growth would likely mean multiple community-focused newsrooms rather than one large organization scaling across multiple cities.

Key Takeaways

- Immigrant communities get their news from platforms like WeChat, WhatsApp, and Nextdoor, not traditional social media or websites

- Newsrooms like Documented NYC serve immigrant populations by hiring reporters from those communities and distributing on community platforms

- Language accessibility means more than translation—it requires reporters who understand specific cultural contexts and community needs

- Community-focused journalism requires nonprofit economics because it doesn't generate traditional advertising or subscription revenue

- Success in immigrant community news should be measured by impact and trust-building, not by viral reach or engagement metrics

Related Articles

- ChatGPT Translate vs Google Translate: Complete Comparison Guide 2025

- Hannspree Lumo: The Dynamic Paper Tablet Redefining E-Readers [2025]

- Lizn Hearpieces Review: Affordable Hearing Aids with Major Comfort Trade-offs [2025]

- AI Accountability & Society: Who Bears Responsibility? [2025]

- Wikipedia's Existential Crisis: AI, Politics, and Dwindling Volunteers [2025]

- Norton VPN Exclusive Pricing 2025: Best Deals on Two-Year Plans [Guide]

![How Newsrooms Reach Immigrant Communities on Messaging Platforms [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-newsrooms-reach-immigrant-communities-on-messaging-platf/image-1-1768478872622.jpg)