How Human Motion Is Teaching Robots to Move Like Us

There's a moment that always catches people off guard. Watch Boston Dynamics' Atlas robot perform a parkour run, and your brain does something weird: it starts treating the machine like it has a body. It doesn't feel like watching industrial equipment anymore. It feels like watching something alive.

That sensation isn't accidental. It's the direct result of years spent teaching robots how humans actually move. Not the simplified, jerky motions from early robotics. Not the mechanical efficiency that makes machines do exactly what they're programmed to do. Real, adaptive, fluid movement that responds to the environment the way a human body responds to a stumble or an unexpected obstacle.

This is where robotics is fundamentally changing. The breakthrough isn't in the hardware alone—it's in how we're programming the software that controls it. By feeding AI systems detailed data about human movement, researchers are creating machines that don't just execute commands. They interpret intent. They adapt in real time. They move with something approaching grace.

But here's what most people miss: this isn't just about making robots look cool. Teaching a robot to move like a human isn't vanity. It's practical. Human bodies are the result of millions of years of evolutionary optimization. We know how to navigate stairs, climb obstacles, recover from slips, and move efficiently over rough terrain. When robots learn those same patterns, they become dramatically more useful in real-world environments. A robot that moves like a human can operate in spaces designed for humans—warehouses, construction sites, hospitals, homes. It doesn't need the environment to be specially built for it.

The technology making this possible is a combination of old and new. Motion capture systems have been around since the 1970s, but they've only recently become sophisticated enough to capture the subtle biomechanical details that matter. Virtual reality allows researchers to simulate thousands of scenarios that would take months to film. Machine learning algorithms can identify patterns in that data that no human observer could ever spot. And reinforcement learning lets robots practice movements millions of times, refining their technique with each iteration.

The result? Robots that are no longer confined to scripted movements. They're learning to improvise, to adapt, to move through chaos with something approaching the fluidity we take for granted in our own bodies.

What Makes Human Movement So Complex

If you think about movement, the obvious part is the large-scale stuff. Your muscles contract, your joints bend, you move through space. But the actual complexity is staggering.

Consider something simple: walking down a hallway. Your eyes are processing visual information and feeding it back to your motor cortex. Your inner ear is tracking balance and spatial orientation. Your feet are sending constant signals about pressure and friction. Your brain is predicting where you're going to be in the next few steps and adjusting muscle tension accordingly. All of this happens simultaneously, with microsecond precision, without you consciously thinking about any of it.

Now make it harder. The floor is uneven. There's an obstacle you didn't see. You trip. Your body's reflexes kick in automatically—you're already rebalancing before you're consciously aware of the problem. Your arms move to stabilize you. Your weight shifts. Your stride adapts. All of this happens in less than a second.

This is why early robots were so terrible at real-world tasks. They were programmed with specific movements for specific situations. If the situation changed even slightly, they either moved incorrectly or stopped entirely. They couldn't improvise because they had no model of how their body interacted with the environment.

The deeper complexity is biomechanical. Human movement isn't just about moving your limbs. It's about the coordination of different body systems. Your legs need to support your weight while your torso rotates and your arms balance. The timing of muscle activation matters. The sequence of muscle contraction matters. The amount of force applied matters. Too little force and you don't move. Too much force and you waste energy or lose balance.

There's also the problem of redundancy. A human arm has seven major joints (shoulder, elbow, wrist, plus hand mechanics). That means you can reach the same point in space using infinite combinations of joint angles. Your brain has to choose which combination to use, and it does so based on efficiency, stability, comfort, and the demands of the current task. There's no single "correct" way to move. There are countless correct ways, and your body automatically selects the best one for the situation.

Robots face the exact same problem, except they have no evolutionary experience to guide them. They have to learn movement from scratch. That's why motion capture and AI are so crucial. Instead of programming every movement manually, researchers can now capture how humans solve these problems and let AI algorithms reverse-engineer the principles.

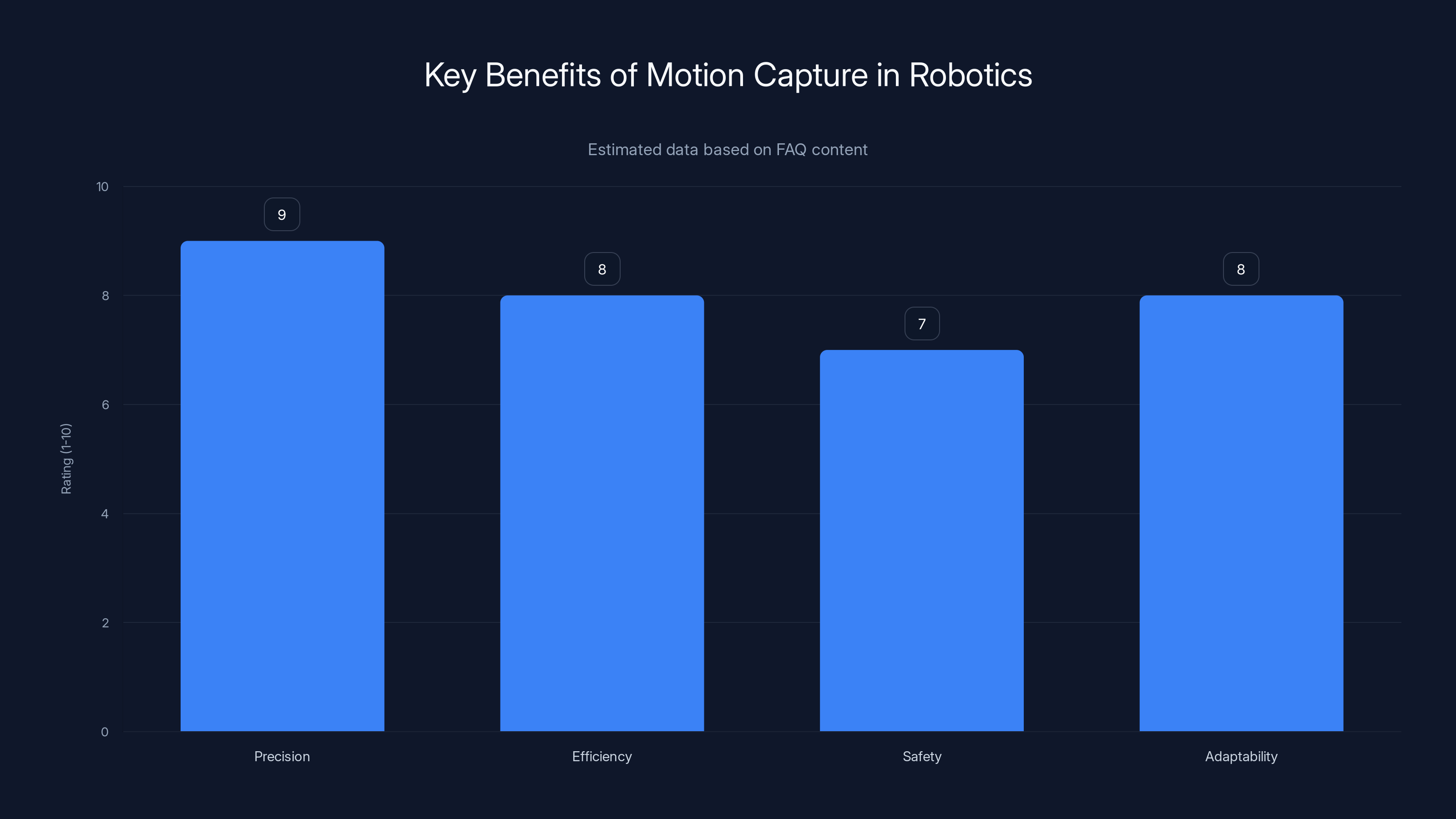

Motion capture offers high precision and efficiency in robot training, with significant safety and adaptability benefits. (Estimated data)

Motion Capture: The Bridge Between Human and Machine

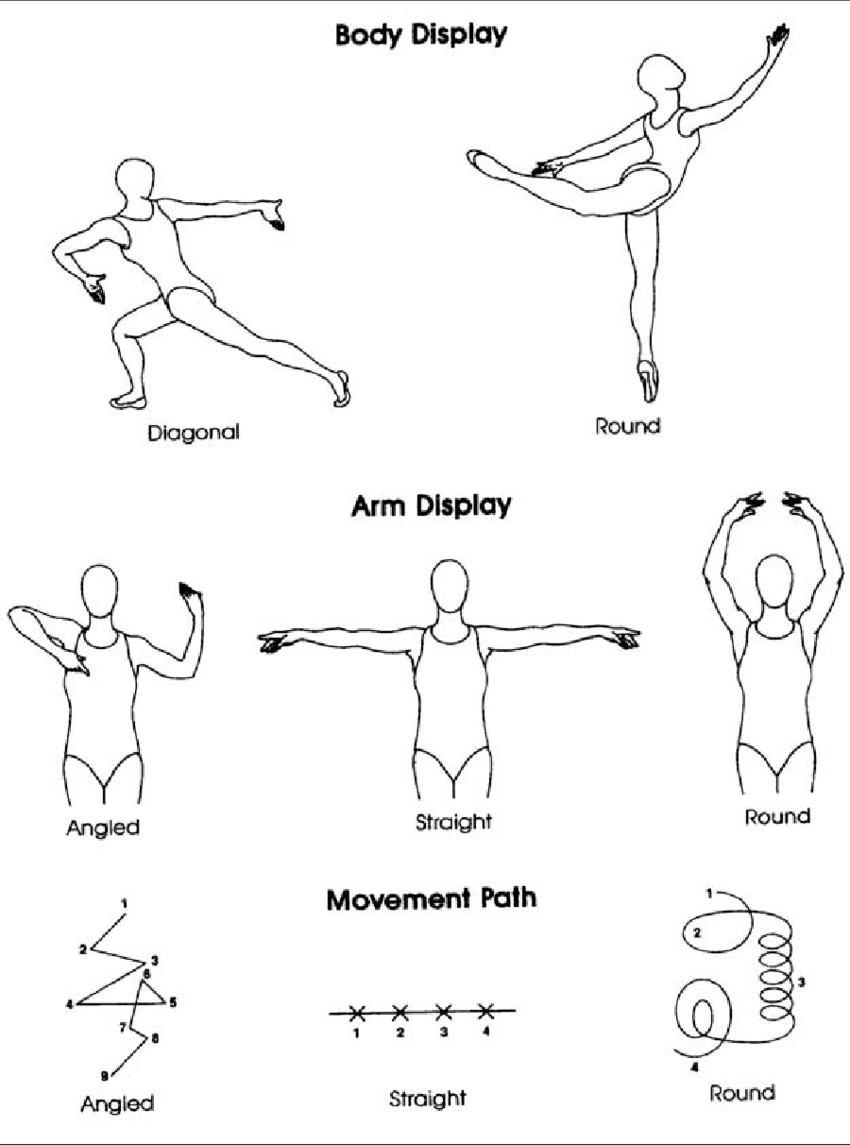

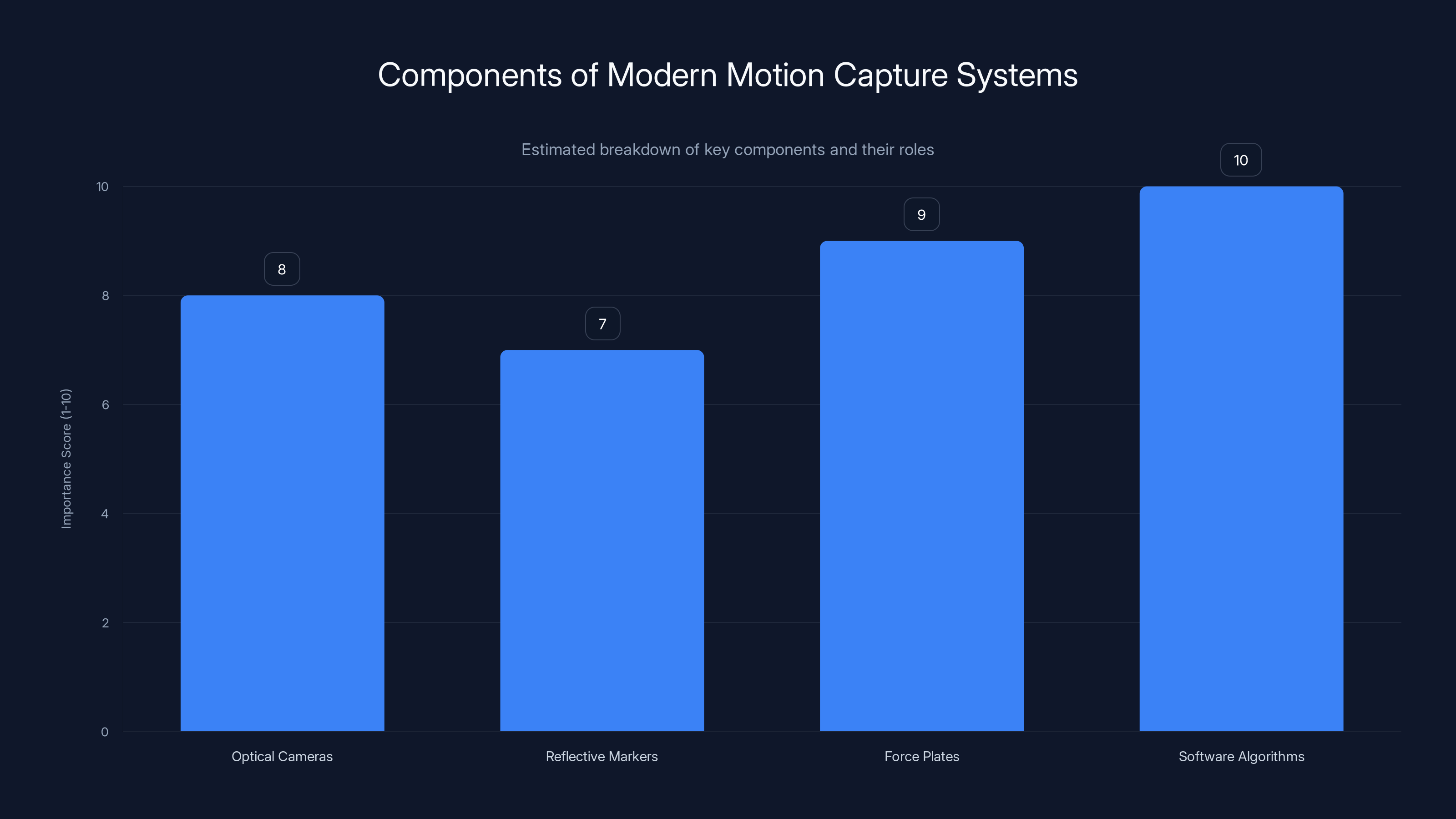

Motion capture technology sounds straightforward: put markers on a human body, film them moving, extract the positions of those markers, and use that data to drive a robot. In practice, it's extraordinarily sophisticated.

The basic system uses optical cameras (usually between 8 and 40 of them) positioned around a capture space. Reflective markers are attached to specific anatomical landmarks—joints, limbs, spine, head. As the actor moves, the cameras track where each marker is in 3D space. Specialized software reconstructs the skeleton structure and tracks how it moves through time.

But raw marker data is just position information. It tells you where the joints are, but it doesn't directly tell you how much force is being applied, what the muscle activation looks like, or how the movement should feel. That's where the sophistication comes in.

Modern motion capture systems often include force plates—sensors built into the ground that measure how much force the person is applying and in which direction. These are crucial because they capture the interaction between the body and the environment. Walking on a force plate shows not just where your foot is, but how hard you're pushing against the ground. That data is essential for training a robot to produce realistic movements.

There's also the problem of marker dropout. Sometimes a marker moves out of view of the cameras. Sometimes markers get occluded by the actor's own body. The software has to intelligently predict where that marker should be based on biomechanical constraints. The human skeleton isn't infinitely flexible—joints have ranges of motion. The system uses these constraints to fill in gaps in the data.

And then there's the problem of scaling. A human actor might be 5'10". The robot might be 5'11" and have a completely different body structure. The limb proportions are different. The joint types are different. The weight distribution is different. Just copying the raw motion data won't work—the physics don't transfer directly. The data has to be adapted and retargeted to the robot's specific morphology.

This is where AI becomes essential. Instead of manually programming rules for how to adapt human motion to a robot, researchers train neural networks on thousands of captured movements. The network learns the underlying principles of human movement—the biomechanical patterns that are consistent across different body sizes and shapes. Then it can apply those principles to generate robot-appropriate movements that maintain the essential characteristics of the original human motion.

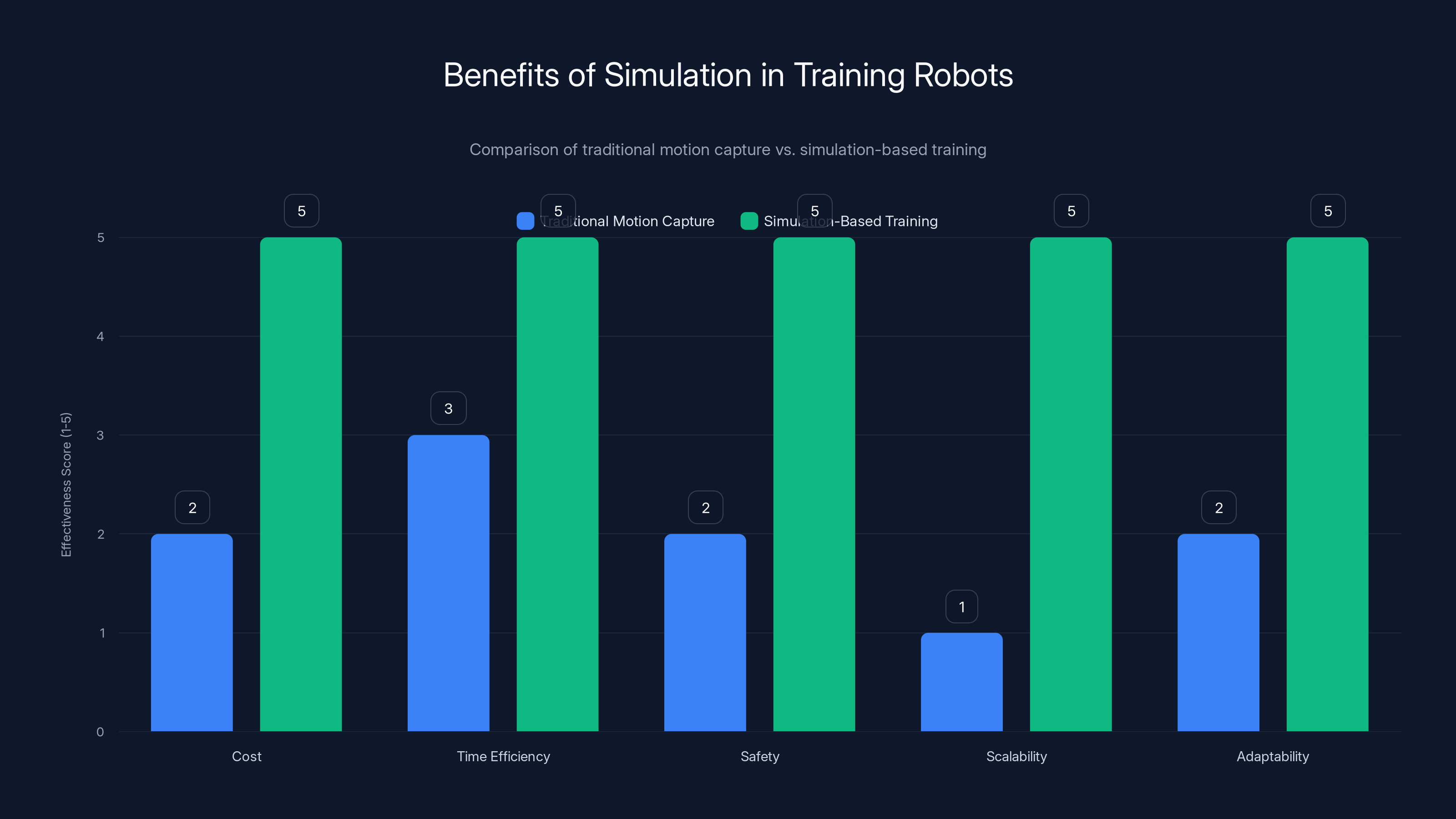

Simulation-based training significantly outperforms traditional motion capture in cost, time efficiency, safety, scalability, and adaptability. Estimated data based on typical advantages of simulation.

Virtual Environments and Simulation: Training at Scale

Here's the limitation of pure motion capture: it's expensive, time-consuming, and limited to movements humans are willing to perform. You can't easily capture someone parkour-jumping off a cliff. You can't film thousands of different ways to climb an obstacle. You can't safely record movement in dangerous scenarios.

This is where simulation changes everything. Instead of filming humans, researchers can create virtual environments with physics engines and let robots practice movements in those simulations millions of times.

The workflow looks something like this: start with motion-captured human movement as the foundation. Feed that into a physics simulation. The robot's AI model (usually a neural network) is tasked with reproducing the captured movement while responding to variations in the environment. The simulation introduces obstacles, changes the ground surface, applies unexpected forces. The AI learns to adapt the basic movement pattern to handle these variations.

This is where reinforcement learning comes in. The robot (in simulation) attempts a movement. The simulation measures how well it accomplished the goal. The neural network gets feedback—reward or penalty—based on performance. Over time, through millions of iterations, the network learns movement patterns that are robust to environmental variation.

The advantage is scale. Simulations run much faster than real time. A researcher can train a robot for the equivalent of months of continuous movement in just hours of computation time. The simulation can introduce scenarios that would be impractical or dangerous to film: falling backward and recovering, navigating extreme slopes, moving through unstable terrain.

But there's a catch, and it's a big one: the "reality gap." Simulations are abstractions of reality. They can't capture every detail of how a physical robot actually behaves. The friction model might be slightly off. The joint mechanics might be simplified. The sensor characteristics might be idealized. Train a robot entirely in simulation, and when you transfer it to the real world, it often fails at tasks it performed perfectly in the virtual environment.

So researchers use a hybrid approach. Train extensively in simulation, then fine-tune with limited real-world data. Or run simulations that deliberately include some "noise"—randomized variations that make the simulation less predictable, which trains the AI to be more robust to real-world unpredictability. This technique is called domain randomization, and it's surprisingly effective at bridging the reality gap.

The other critical element is physics fidelity. Modern physics engines (like Py Bullet or Mu Jo Co) can simulate rigid body dynamics with remarkable accuracy. They can model contact forces, friction, damping, and joint constraints. This means that movements trained in simulation actually do transfer reasonably well to real robots, especially for fundamental movements like walking or running.

Deep Reinforcement Learning: Teaching Robots to Improvise

Let's say you've got motion-captured human walking data. You've built a physics simulation with a robot. Now what? How do you actually teach the robot to walk?

This is where deep reinforcement learning (DRL) becomes indispensable. Unlike supervised learning, where you show the AI the correct answer and punish it for being wrong, reinforcement learning teaches through trial and error with rewards.

The robot starts in simulation. It applies random forces to its joints—essentially flailing around. The physics engine calculates what happens: the robot falls, tumbles, maybe stumbles forward accidentally. The algorithm measures: Did we accomplish the goal? How close are we? It assigns a reward signal. Negative reward for falling. Positive reward for moving forward. Huge positive reward for moving forward smoothly while maintaining balance.

The neural network adjusts its weights slightly based on that reward signal. Then the robot tries again. And again. And again. After millions of iterations, patterns emerge. The network learns that applying force to the left leg while the right leg is in the air tends to produce forward motion. It learns the timing. It learns the magnitude of forces needed for different speeds.

But here's the remarkable part: the network doesn't learn a fixed movement pattern. It learns a policy—a set of principles for how to move. Show the robot a new terrain, and it doesn't just apply a memorized sequence. It applies the learned principles, adapting in real time to the new conditions.

There's a technique called imitation learning that accelerates this process. Instead of starting from random movements, the robot's neural network is pretrained on motion-captured human movement. The network already has a rough idea of what walking looks like. Then reinforcement learning fine-tunes it, pushing the network to generate movement that's not just similar to human movement, but actually effective and stable for the robot's specific body.

The reward function is crucial and surprisingly subtle. Simple reward functions can lead to weird movement. For example, if you only reward forward progress, the robot might learn to flail violently but move forward quickly—technically achieving the goal but looking nothing like natural walking. Researchers have to carefully design reward functions that capture what they actually want: smooth, efficient, stable movement that adapts appropriately to the environment.

One advanced approach is using human preference learning. Instead of manually designing the reward function, the AI shows researchers different movement variations and asks: which one looks better? This human feedback helps the AI understand what counts as "good" movement from a human perspective, not just from a pure engineering perspective.

Force plates and software algorithms are crucial in modern motion capture systems, with high importance scores due to their roles in capturing force data and reconstructing movement. (Estimated data)

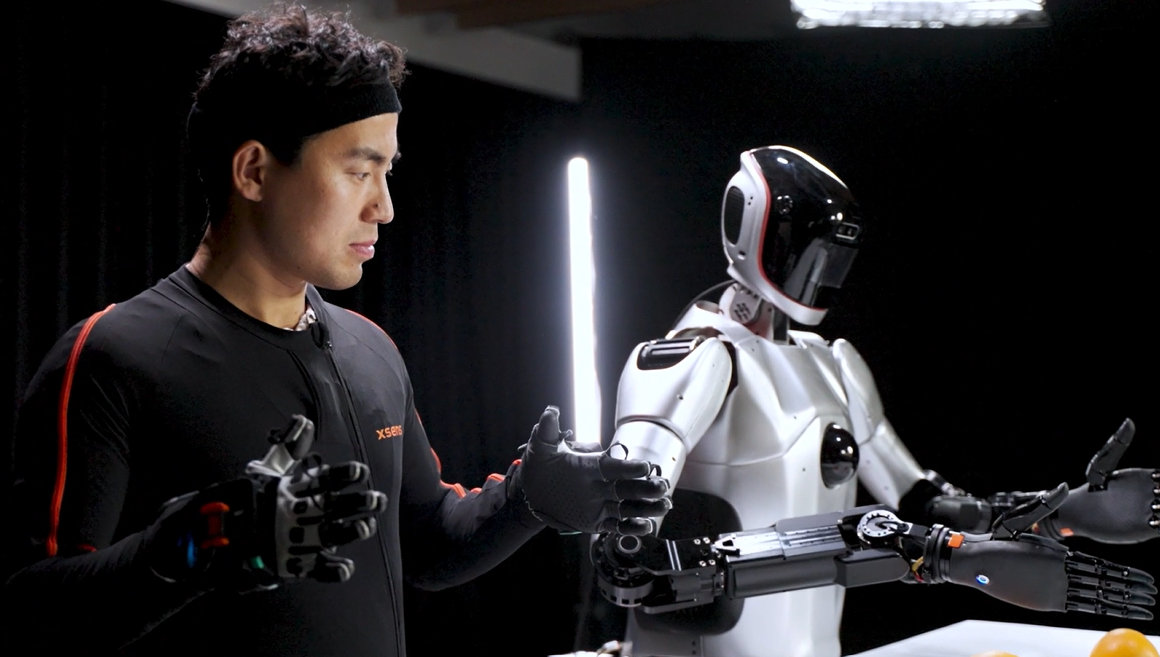

VR and Teleoperation: Learning from Embodied Human Experience

Motion capture records movement, but it's a passive recording. The human doesn't experience what the robot would experience. They don't feel gravity the way the robot feels it. They don't have the robot's constraints.

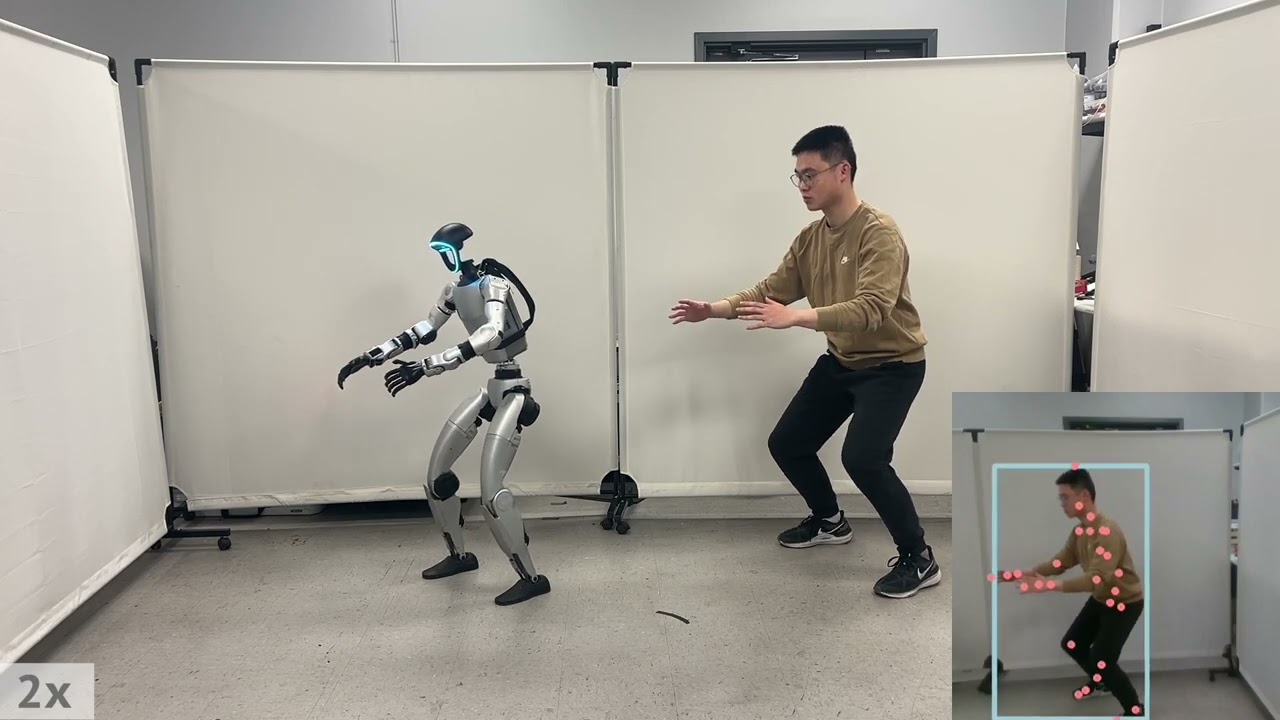

Virtual reality changes this. Instead of just recording movement, a human operator can put on a VR headset and actually inhabit the robot's perspective—literally seeing through the robot's cameras, controlling its limbs, and experiencing the feedback from its sensors.

This is called teleoperation, and it's becoming increasingly important in robotics research. The human operator gets real-time sensory feedback: video feed from the robot's cameras, haptic feedback through controllers (vibration patterns that simulate the sensation of contact), sometimes even force feedback that shows how much resistance the robot encounters when trying to move.

When the human operates the robot through VR, they're solving real-time control problems. How hard do I need to push to climb this obstacle? How do I balance when the surface is slippery? These are the kinds of decisions that require embodied understanding—understanding that comes from having a body and moving through the world.

More importantly, this teleoperation data becomes training data. Record thousands of hours of human operators controlling robots through VR, and you've got a dataset of human-guided solutions to real problems. This data is invaluable for training AI systems.

The combination is powerful: motion capture provides general principles of human movement, simulation provides safe practice at scale, reinforcement learning provides refinement and adaptation, and VR teleoperation provides real-world data and human problem-solving expertise.

There's also an interesting convergence happening. As AI systems get better at movement, they're being used to assist human operators in VR. The AI doesn't control the robot directly—it provides suggestions, stabilization, and safety constraints. The human makes the decisions, but the AI handles the low-level details of balance and safe motion. This creates an even richer dataset of how to solve problems in real-world conditions.

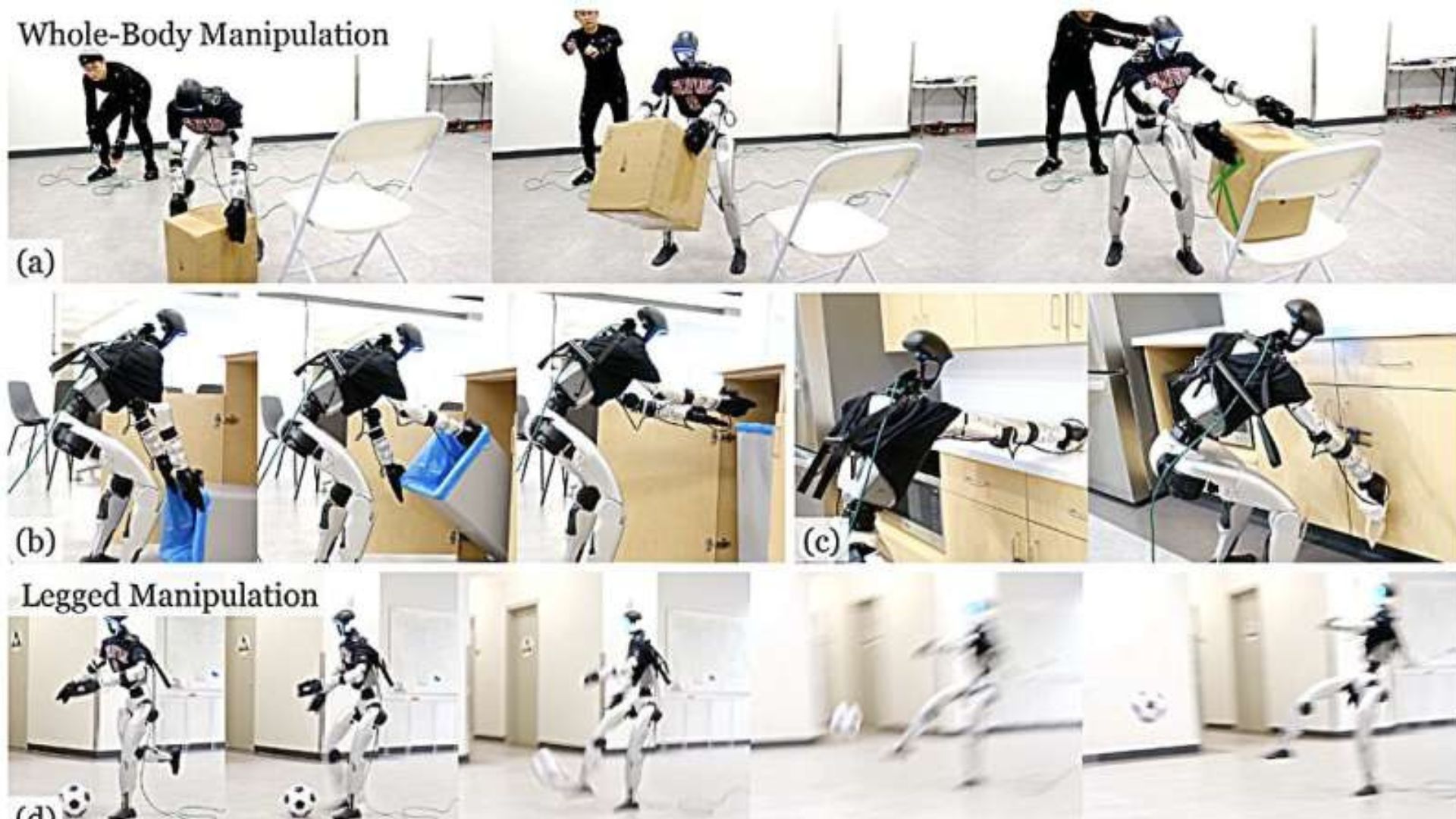

Transfer Learning: Applying One Motion to Many Tasks

Once a robot has learned to walk, does it need to start from scratch to learn to run? What about climbing stairs? What about recovering from a stumble?

Transfer learning is the principle that knowledge learned in one domain can be applied to a different domain. A robot that's learned the fundamentals of legged locomotion has already learned a lot of useful skills: how to balance, how to distribute weight, how to time limb movements, how to respond to instability.

A clever way to implement this is through hierarchical learning. The robot first learns basic skills: balanced standing, forward walking, responding to small perturbations. These basic skills are "locked in"—the network learns them thoroughly. Then, training continues on more complex skills: running, climbing, parkour. But the base skills are available for higher-level behaviors to build on.

Another approach is multitask learning. Train a single network to perform multiple tasks simultaneously: walking, running, stair climbing, backward walking, turning. The network learns shared representations—internal features that are useful for multiple tasks. This creates a more robust, flexible system because the network has to find principles that work across different scenarios.

There's also domain transfer. Train a robot walking on flat ground, then apply it to uneven terrain. Train on one robot morphology and apply to a different robot. The underlying principles of locomotion don't change, even though the specific details (limb proportions, motor characteristics, sensor types) might be different.

The remarkable finding is that this often works better than expected. A policy trained on a legged robot can sometimes transfer to a different legged robot with minimal adjustment. A walking policy can provide a foundation for learning to climb stairs. The principles are general enough to apply broadly.

This is where the future efficiency comes from. Instead of training every new behavior from scratch, researchers can build on previously learned skills. A robot that took months to train initially can learn a new task in days or hours by transferring knowledge from related tasks.

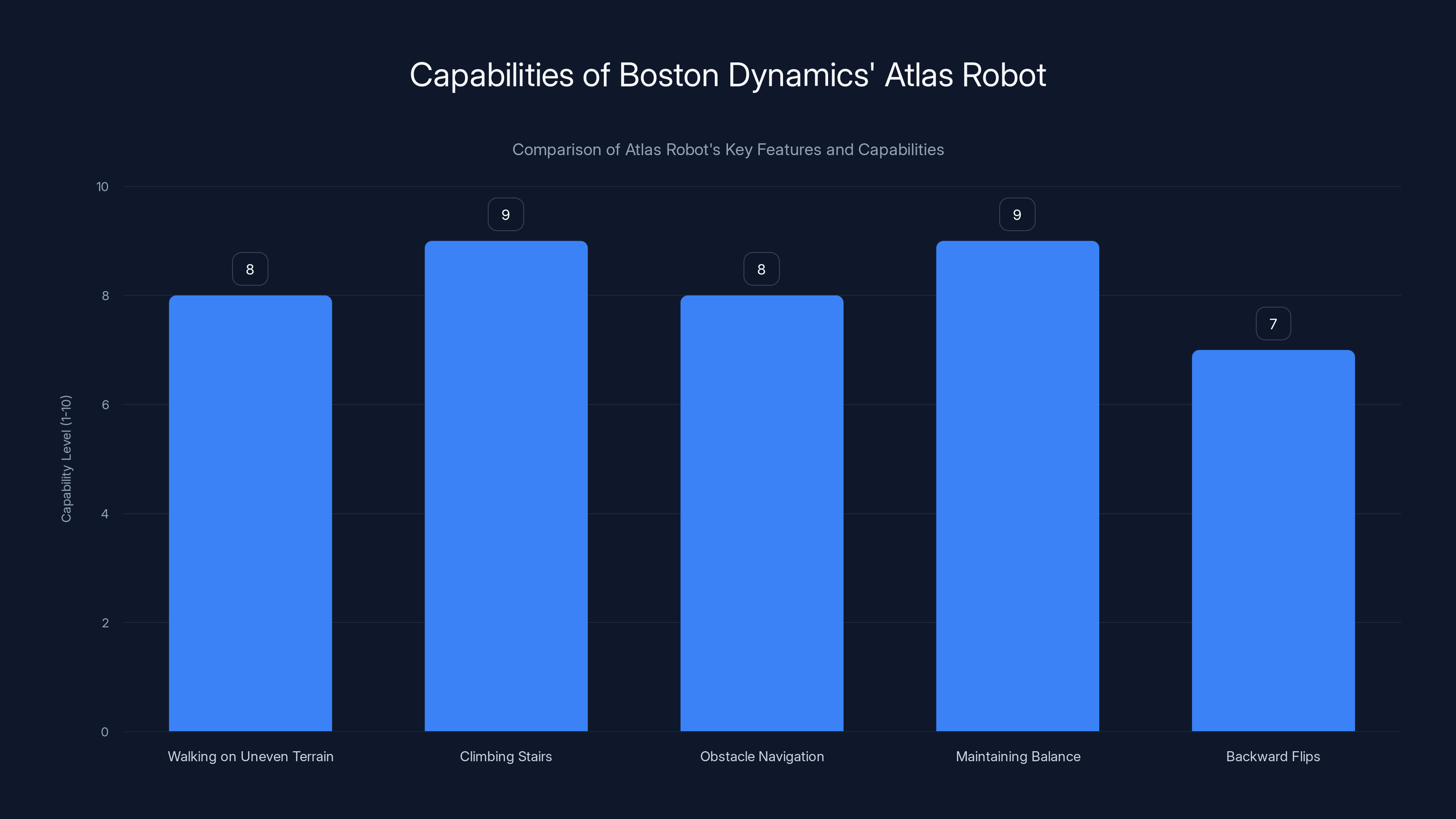

Atlas excels in maintaining balance and climbing stairs, with high capability levels in navigating obstacles and walking on uneven terrain. Estimated data based on described capabilities.

Biomechanical Constraints and Natural Movement

Here's something that surprised many roboticists: if you train an AI system on human movement data without explicitly constraining it, the AI naturally learns to produce movement that respects human biomechanical principles.

Why? Because those principles are solutions to real problems. The human body evolved to move efficiently within its constraints. Movements that respect biomechanical constraints—that align joints in natural ranges, that use muscle groups in coordinated sequences—tend to be more stable, more efficient, and more generalizable to new situations.

Researchers are now deliberately encoding biomechanical knowledge into AI training. Not by manually programming movements, but by structuring the network architecture and loss functions to encourage solutions that align with how bodies actually work.

For example, you can build in the constraint that joints only bend in specific ranges and directions. You can structure the network to naturally produce smooth, continuous motion rather than jerky changes. You can reward movement patterns that distribute load across multiple joints rather than putting stress on a single joint.

The result is that AI-generated movement doesn't just look human—it's actually biomechanically sensible. It's efficient. It's stable. It's likely to generalize to new situations because it's based on principles rather than memorized patterns.

There's a fascinating convergence here. By training on human data and imposing biomechanical constraints, AI systems naturally converge on solutions that are similar to how humans move. Not identical—the robot's body is different, after all—but recognizably human in character. This isn't accidental. It's the result of biomechanical principles being nearly optimal for legged locomotion.

Atlas and the State of the Art

Boston Dynamics' Atlas robot has become the public face of advanced humanoid robotics, and for good reason. The robot's movements are genuinely impressive—not because they're perfect, but because they represent a leap in how naturally a machine can move.

Atlas is about 5'9" tall, weighs around 330 pounds, and has 28 joints. From a pure hardware perspective, it's state-of-the-art but not revolutionary. It has hydraulic actuators, which are powerful but not novel. The real advancement is in the control software.

The robot can walk on uneven terrain, climb stairs, navigate obstacles, and maintain balance when pushed. It can do backward flips. It can pick up objects. Most impressively, it can adapt—if the terrain changes, if there's an unexpected obstacle, if the robot is pushed off-balance, it responds fluidly rather than failing.

How was this achieved? Through years of data collection, thousands of hours of simulation, careful reinforcement learning, and what appears to be some hand-coded behavior for specific situations. Boston Dynamics hasn't publicly released detailed technical documentation, but interviews with their team suggest a combination of approaches.

The team used motion capture of human movement as a starting point. They built physics simulations that included the robot's actual hydraulic characteristics. They used reinforcement learning to train policies for different locomotion modes: walking at different speeds, running, climbing stairs, navigating obstacles. They probably used some imitation learning to jumpstart training from human movement data.

What makes Atlas stand out is not that it's using fundamentally new techniques. It's that the team has carefully integrated these techniques and iterated on the implementation until they've achieved surprisingly robust real-world performance.

It's worth noting what Atlas still struggles with: very uneven terrain, moving objects that require dexterous manipulation, long-duration tasks without human intervention. These are the boundaries of current capability. The fact that these are the boundaries tells us a lot about what we've achieved and what remains difficult.

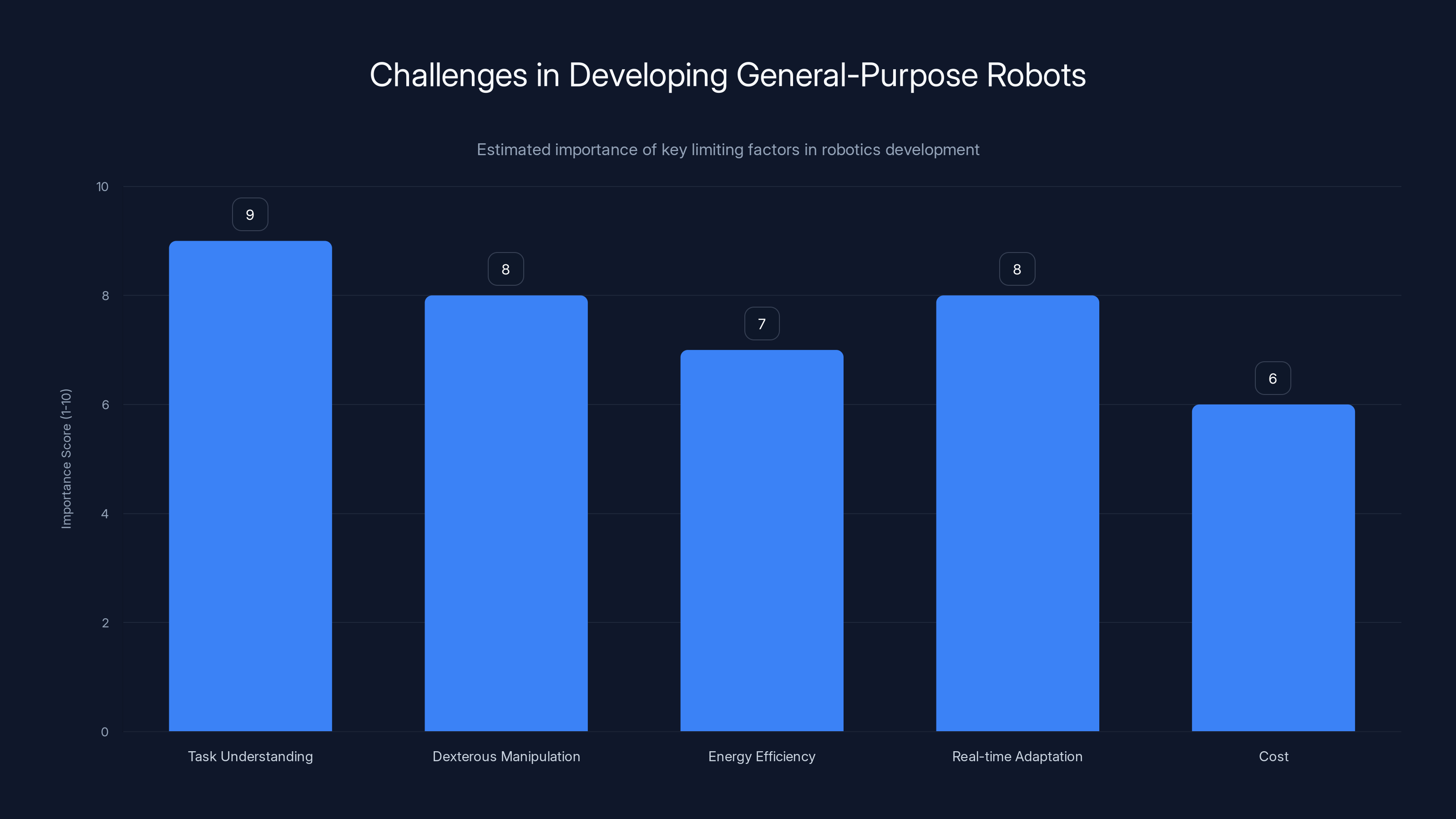

Task understanding and dexterous manipulation are critical challenges in developing general-purpose robots, requiring significant advancements in AI and robotics technology. (Estimated data)

Humanoid vs. Non-Humanoid Approaches

Should robots be humanoid? It seems obvious—if humans move efficiently, shouldn't robots copy that design? But it's actually not that simple.

Humanoid robots have huge advantages. They can use tools designed for human hands. They can operate in environments designed for human bodies. Their movement patterns are intuitive to humans—we naturally understand what they're about to do. This familiarity reduces perceived risk and increases acceptance.

But humanoid robots have significant disadvantages. The human form is optimized for human-scale tasks in human-scale environments. For many industrial applications, it's suboptimal. A robot designed specifically for package sorting doesn't need human hands—specialized grippers are more efficient. A robot designed to climb stairs doesn't need human proportions—spider-like legs might work better.

Moreover, humanoid robots are mechanically complex. Getting the balance, the motor control, the sensing right is genuinely hard. Non-humanoid robots with simpler morphologies can be easier to control and more reliable.

The emerging consensus seems to be: humanoid robots for tasks that require flexibility and operation in human spaces. Non-humanoid designs for specialized tasks where the environment can be adapted to the robot.

But here's the important point: the techniques for teaching movement apply regardless of morphology. Motion capture can be adapted to record non-human movement. Simulation works for any body structure. Reinforcement learning applies universally. Virtual reality teleoperation works for any robot.

The difference is that for non-humanoid robots, the motion data comes from different sources. For a quadrupedal robot, you'd capture dog or horse movement. For a robotic arm, you'd capture human arm movement but potentially adapted for the different mechanics.

What's interesting is that applying human motion data to non-humanoid robots sometimes produces surprisingly good results. A quadrupedal robot trained with quadrupedal motion capture learns more efficiently, but if you feed it bipedal human data with appropriate retargeting, it can still learn—it just takes longer and is less efficient. The principles of coordination and balance transfer somewhat.

Real-World Deployment and the Challenges Ahead

There's a big difference between a robot that moves well in a controlled environment and a robot that actually works in the real world.

In the lab, everything is known. The floor is a consistent material. The lighting is controlled. The obstacles are predictable. The robot has time to move slowly and carefully. Deploying the same robot in a warehouse, on a construction site, or in a home requires handling significant uncertainty.

Real-world deployment introduces challenges that simulation can't fully capture. Dynamic obstacles—other robots moving, humans moving around. Variable surfaces—concrete, tile, dirt, gravel. Lighting variation that affects vision. Temperature changes that affect sensor accuracy and motor response. Unpredictable forces—objects moving unexpectedly, people interacting with the robot.

This is where the motion capture training becomes crucial. Because the robot has learned fundamental principles of movement from human data rather than just memorizing a specific walking pattern, it can generalize. It can adapt to new surfaces and obstacles because it understands the underlying principles.

But there's still a gap. Current robots trained this way work well in semi-controlled environments. Full deployment in truly dynamic, unpredictable environments like human homes or chaotic construction sites is still being worked on.

One key challenge is foot placement. Humans can walk through complex environments because we process visual information and plan foot placement accordingly. Current robots can do this too, but the decision-making is slower and sometimes suboptimal. Teaching robots to look ahead, predict where their feet should go, and execute that plan smoothly is an active area of research.

Another challenge is energy efficiency. Humans move efficiently because millions of years of evolution optimized our bodies for minimal energy expenditure. Current robots move well but not efficiently. Atlas, for example, consumes significant power even for basic walking. Making robots that can operate for extended periods on limited battery power requires improving energy efficiency.

There's also the problem of wear and tear. Robots trained in simulation don't experience fatigue, damage, or gradual degradation. Real robots degrade. Motors wear out. Sensors accumulate dust. Joints accumulate slack. Training robots to detect and compensate for this degradation is important for long-term autonomous operation.

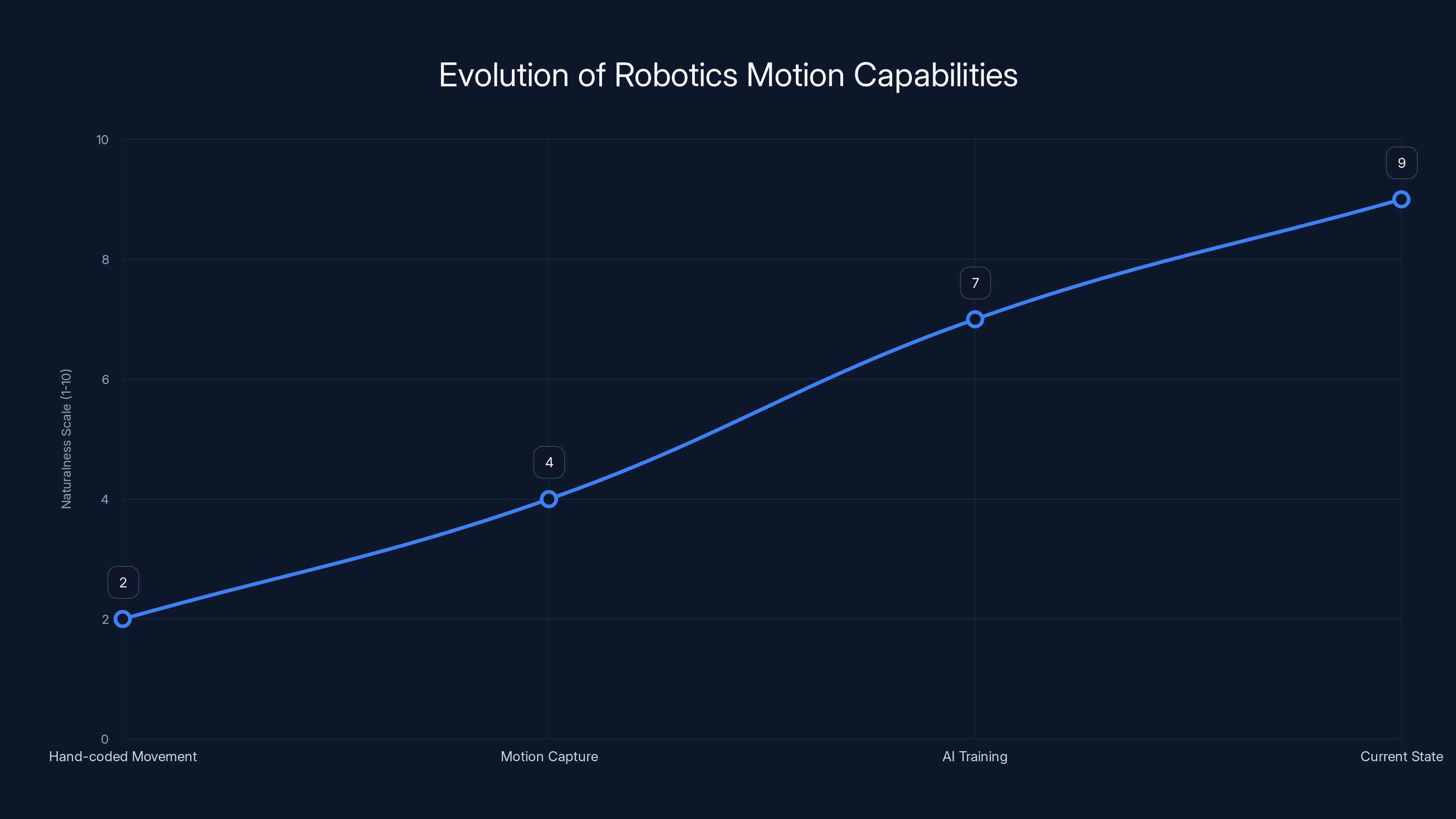

Estimated data shows significant improvement in robotic motion naturalness, with AI training leading to near-human-like movement capabilities.

Multi-Agent Learning and Collaborative Movement

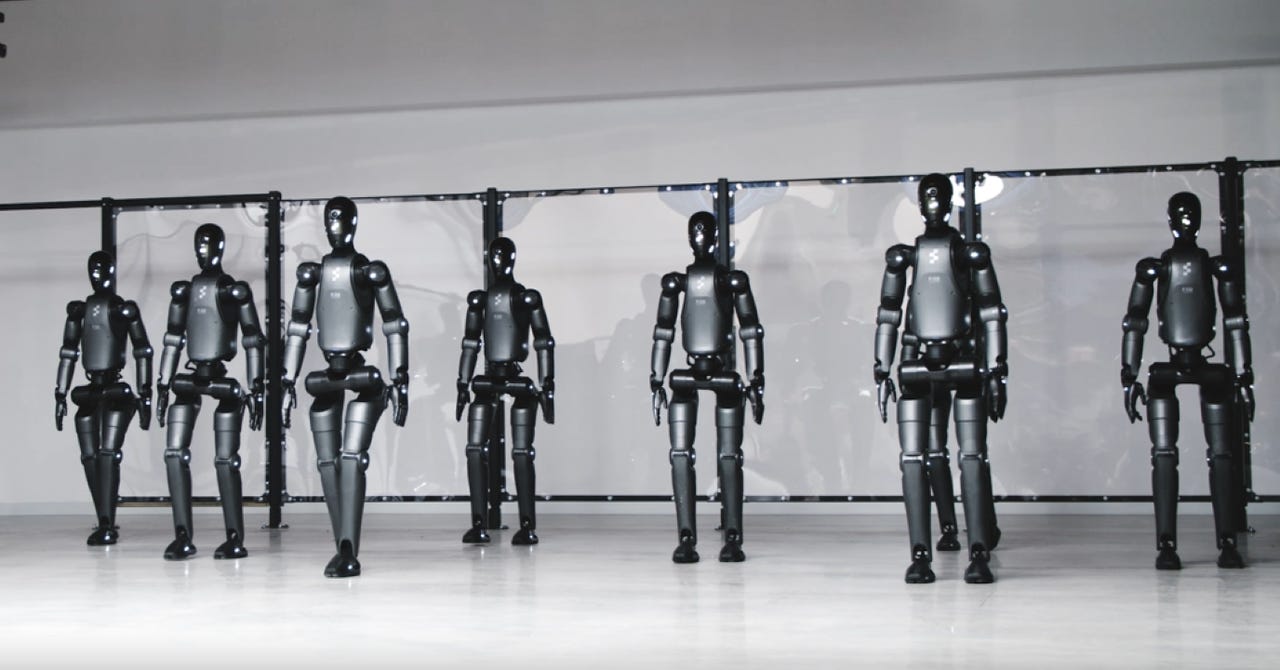

What happens when you have multiple robots that need to move together?

Humans do this naturally. Two people can coordinate to move a large object. A team of workers can move in formation. We have social understanding—we model what other people are going to do and adjust our movements accordingly.

Robots are just starting to learn this. Multi-agent reinforcement learning is an emerging field where multiple AI agents train together, each learning not just to accomplish their own task but to predict and respond to what the other agents will do.

This is incredibly useful for coordination. In a warehouse, multiple robots might need to move items along a conveyor system, coordinate to lift a heavy object, or navigate around each other in tight spaces. Training a system where each robot learns to move effectively while being aware of the other robots' positions and intended actions produces better coordination than simply programming collision avoidance.

Multi-agent learning also opens up possibilities for emergent behavior—coordination patterns that nobody explicitly programmed. Researchers have seen systems where robots learn to naturally form efficient queue-like structures, to handle heavy objects by cooperating, to adapt their movements based on team composition.

This is still an early-stage research area. True collaborative humanoid robots that can work together on complex tasks with minimal human direction is probably at least several years away. But the foundation is being laid through motion-capture-based training of coordinated movement.

Vision and Perception in Motion Learning

Here's something that's easy to overlook: moving effectively requires perceiving the environment effectively.

When a human walks, our eyes are constantly processing information. We see obstacles before we step. We perceive slope and surface texture. We notice other people and objects. That visual information is integrated with our proprioception (the sense of where our body is in space) and our vestibular system (the sense of balance), and that combination guides movement.

Robots need the same integration. A robot trained to walk but without good visual perception will stumble over obstacles it doesn't see. A robot with good vision but poor proprioception will generate movements that don't match the environment.

Modern approaches train vision and motion together. The robot learns to move while simultaneously learning to perceive. As it moves through the environment, it's gathering visual data that trains its perception system. As its perception improves, it can move more effectively through complex environments.

There's also active perception—deliberately moving to see better. Humans do this: we turn our heads to see around obstacles, we shift our weight to get a better view of the ground. Robots are starting to learn similar behaviors. A robot encountering a difficult terrain might pause, look more carefully, and then proceed once it understands the surface.

The combination of motion capture training and vision-based learning is powerful. The robot learns fundamental movement principles from human motion data, then learns to apply those principles in real environments based on what it perceives.

The Path to General-Purpose Robots

Where is all of this heading?

The vision is clear: robots that can move through real-world environments with the flexibility, grace, and adaptability of humans. Robots that don't need carefully controlled conditions. Robots that can handle unexpected obstacles, adapt to new environments, and collaborate with humans and other robots.

We're not there yet. Current robots are impressive but narrow. Atlas is spectacular at walking and climbing and parkour. Spot (another Boston Dynamics robot) is good at inspection and mapping. Humanoid robots in development at various companies are getting better at dexterous manipulation. But none of these robots can currently walk into a home, understand what needs to be cleaned, do it efficiently, and then move to the next task.

The limiting factors are becoming clearer. It's not motion itself anymore—we've largely solved that problem through motion capture, simulation, and reinforcement learning. The limiting factors are now:

- Task understanding: knowing what needs to be done and planning how to do it

- Dexterous manipulation: robots are still bad at complex hand tasks

- Energy efficiency: current robots consume too much power for long autonomous operation

- Real-time adaptation: adapting to truly novel situations quickly

- Cost: current advanced robots are prohibitively expensive

The motion learning techniques we've discussed address some of these. Good movement helps with task execution. Motion-based training that incorporates manipulation could improve robot hands. Efficient movement patterns reduce energy consumption.

But solving the full problem requires more than just better motion. It requires better AI for planning and reasoning. It requires better sensors. It requires better actuators. It requires solving the robotics problem holistically, not just the motion part.

That said, motion is foundational. A robot that moves well is a robot that can navigate environments, interact with objects at different heights and angles, and work alongside humans safely. The investment in motion learning is essential infrastructure for everything else.

Challenges in Scaling and Standardization

One overlooked challenge: as robots become better, we need to scale production. Currently, advanced humanoid robots are produced in tiny quantities. Atlas is mostly a research platform. Spot has been deployed to more customers, but we're talking hundreds of units, not millions.

Scaling production while maintaining the performance that comes from careful training is difficult. You can't just manufacture 10,000 Atlas units and expect them to all perform identically. Each robot will have slightly different joint characteristics, sensor calibrations, motor response curves. These small differences can accumulate and affect behavior.

This is where standardization becomes important. The motion capture data, the training algorithms, the simulation environments, the reinforcement learning frameworks—these are starting to become standardized. There are common platforms like Gym (for defining RL tasks) and ROS (Robot Operating System) that provide common interfaces.

As these standards mature, smaller companies and research institutions can build on common foundations. Rather than each organization developing its own motion capture system, training framework, and simulation environment, they can adopt proven solutions and focus their innovation on specific applications.

There's also the question of how much customization is needed. Do you need custom motion training for each robot unit, or can you train once and deploy to many units? Early evidence suggests the latter is possible—a trained policy can transfer to different units of the same model. But optimization for specific hardware characteristics probably still helps.

Economic and Practical Impacts

Why does motion matter economically?

Because a robot that moves like a human can work in spaces designed for humans without expensive modifications. A warehouse doesn't need to build special pathways if its robots can navigate stairs and doorways. A construction site doesn't need to level the ground specially for robots if they can handle uneven terrain.

This dramatically expands the potential applications. Currently, industrial robots are confined to structured environments where the workspace is optimized for them. Humanoid robots that move well can work in less-structured environments.

There's also the labor economics. A robot that can do 50% of a human worker's job with 20% of the cost can be economically justified in many industries. That threshold is rapidly being crossed. A robot that's expensive but reliable beats hiring multiple workers if those workers are unreliable or expensive to manage.

But there's more than economics. There's safety. A robot that moves naturally and predictably is easier for humans to work around safely. You can intuitively predict where the robot will be and what it will do. A robot with jerky, unpredictable movement is genuinely unsafe to work near.

There's also the psychological and social dimension. A robot that moves like a human is easier to train humans to work with. We have millions of years of experience reading human body language. Applying that understanding to robots that move naturally is almost automatic. Robots with alien movement patterns require humans to learn entirely new interpretive frameworks.

Data Privacy and Ethical Considerations

Here's an issue that hasn't gotten much attention: what about the humans whose movement is being captured?

Large-scale motion capture datasets involve hundreds or thousands of people. These datasets contain sensitive information—how individuals move, their gait patterns, their range of motion. In some cases, datasets include biometric data that could be used to identify individuals or infer health conditions.

When researchers train robots on this data, there are questions about consent. Was movement data collected with understanding of how it would be used? Who owns the data? How long should it be retained? What happens if it's shared with other researchers or commercial companies?

These questions don't have settled answers. Currently, the field is largely self-governed. Researchers typically anonymize data and follow IRB (Institutional Review Board) guidelines when collecting from human subjects. But there's growing recognition that this area needs more formal regulation and standards.

There's also an interesting question about bias. Human movement data reflects the diversity (or lack thereof) of the people being recorded. If motion capture is done primarily with young, able-bodied individuals, the trained robots will be optimized for moving like young, able-bodied humans. They might move poorly for very tall people, short people, people with disabilities, elderly people, or people from different ethnic backgrounds with different biomechanical characteristics.

As robot deployment becomes more widespread, ensuring that robots can work well with diverse human populations becomes important. This probably requires capturing and training on movement data from diverse populations.

Future Directions: Generative Models and Synthetic Data

What's the next frontier? Generative models that can create realistic movement without requiring capture of actual humans.

Already, generative AI (like diffusion models or large language models adapted for movement generation) can create plausible human movement. Show the system examples of walking and running, and it can generate variations—different walking speeds, different terrains, different body types.

This could change the data problem. Instead of needing to capture thousands of hours of human movement, researchers could generate synthetic movement data using generative models trained on smaller amounts of real data. This synthetic data could then be used to train robots.

The advantage is flexibility. Need walking on slopes? Generate it. Need movement patterns for people of a specific height or body type? Generate them. Need thousands of variations of a specific movement for robust training? Generate them.

The challenge is ensuring that synthetic data has sufficient realism. If the generated movement violates biomechanical principles or includes unrealistic transitions, robots trained on it will learn those unrealistic patterns. But as generative models improve, the quality of synthetic data is improving too.

There's also the possibility of video generation. Generative models are getting good at creating realistic video. Imagine feeding a generative model thousands of examples of human movement and having it create synthetic video of humans moving in ways and environments that were never filmed. That video could then be used as the basis for robot training.

This represents a potential inflection point. Once generative models are good enough, the data bottleneck dissolves. Researchers could generate essentially unlimited training data for any movement scenario. The limiting factor would shift from data collection to simulation fidelity and training algorithm efficiency.

Conclusion: A New Era of Robotics

The transformation happening in robotics right now isn't just incremental improvement. It's a fundamental shift in how we approach robot motion. Instead of engineering every movement manually, we're capturing human movement, training AI systems on that data, and letting machines figure out how to apply those principles to their own bodies in new situations.

It's working. Robots move more naturally and effectively than ever before. They navigate obstacles they've never seen. They adapt to environments they weren't trained for. They handle unexpected disturbances without falling. They're not as graceful as humans yet, but they're approaching it.

The implications are significant. A robot that moves well is a robot that can be useful in the real world. And as the cost of advanced robotics decreases and the performance increases, we're approaching a point where robots moving like humans will be common in workplaces, homes, and public spaces.

This journey started with engineers trying to hand-code movement. It progressed through motion capture systems recording human movement. It's now at a point where AI systems trained on human data and refined through simulation and reinforcement learning are producing movement that's remarkably human-like.

The next phase will involve scaling, refinement, and integration with other AI capabilities. Robots that move well need to also perceive well, reason well, and manipulate effectively. But the motion foundation is being laid. For the first time, we have methods that work at scale for teaching robots one of the things humans do best: moving through the world with grace, efficiency, and adaptability.

That's the revolution happening now. And it started with recognizing that human movement, shaped by millions of years of evolution, contains principles that machines can learn.

FAQ

What is motion capture and how does it work?

Motion capture uses cameras and reflective markers placed on a person's body to track their movement in three-dimensional space. Specialized software reconstructs the skeleton structure and translates the captured movement data into a format that can drive a robot or virtual character, recording detailed information about joint positions, timing, and force application.

Why is human movement important for training robots?

Human movement represents millions of years of evolutionary optimization for operating in natural, unstructured environments. By learning from human movement patterns, robots can acquire biomechanically sensible movement principles that are stable, efficient, and generalize well to new situations without requiring manual programming of every possible movement variation.

How do simulation and virtual environments speed up robot training?

Robots can practice movements in physics simulations millions of times faster than real time, allowing months of equivalent practice in just hours of computation. Simulations enable safe exploration of dangerous movements and scenarios that would be expensive or impossible to film with human subjects, dramatically accelerating the training process.

What is reinforcement learning and how does it apply to robot motion?

Reinforcement learning teaches robots through trial and error with reward signals. A robot in simulation attempts movements and receives feedback based on how well the movement achieved the goal. Over millions of iterations, the neural network learns movement policies that are not just similar to human movement, but effective and robust for the robot's specific body and environment.

Can robots transfer movement skills learned for one task to completely different tasks?

Yes, through transfer learning and hierarchical skill learning. Once a robot learns fundamental movement skills like balance and coordination, these skills provide a foundation for learning more complex movements. Interestingly, movement trained on one robot morphology can sometimes transfer to different robots with appropriate adaptation, because the underlying principles of locomotion are general.

What is the difference between humanoid and non-humanoid robot designs?

Humanoid robots match human proportions and can use human tools and environments without modification, but this adds mechanical complexity. Non-humanoid designs can be specialized for specific tasks (like quadrupedal robots for rough terrain). The motion-learning techniques apply to both, but humanoid robots are better for flexible, general-purpose tasks while specialized designs excel at specific applications.

What challenges remain before robots can work fully autonomously in real-world environments?

Key challenges include energy efficiency (current robots consume too much power for long operation), truly real-time adaptation to novel situations, dexterous manipulation with hands (robots are still clumsy), cost reduction to make advanced robots affordable, and task understanding (knowing what needs to be done and planning effectively). Motion learning has largely solved the basic movement problem, but robots need additional capabilities for true autonomy.

How do researchers handle the "reality gap" between simulation and real-world robot performance?

Researchers use domain randomization (training simulations with deliberate noise and variation), hybrid approaches (extensive simulation training followed by fine-tuning with real data), and increasingly accurate physics engines. More fundamentally, training on human movement data provides robust principles that generalize better than training on simulated-only data.

Can movement trained on one human body be applied to robots with completely different proportions?

Yes, through a process called motion retargeting. The robot learns the underlying biomechanical principles from human movement data, then adapts those principles to its own body structure. A robot with different limb proportions or joint types can still apply the fundamental movement principles like balance, coordination timing, and force distribution, though direct copying would require adaptation.

What role will generative AI play in future robot training?

Generative models could create unlimited synthetic training data, removing the bottleneck of requiring humans to be motion-captured. Instead of filming thousands of movement variations, researchers could generate synthetic human movement for any scenario. This would accelerate training and allow customization for specific robot morphologies or environmental conditions without extensive human data collection.

Key Takeaways

- Motion capture technology combined with AI training has revolutionized robot movement, making humanoid robots capable of natural, adaptive locomotion in real environments

- Reinforcement learning in physics simulations allows robots to practice millions of movement variations, dramatically accelerating training compared to real-world learning

- Robots trained on human biomechanical principles naturally develop efficient, stable movement that generalizes to novel situations and different environments

- Multi-modal training combining motion capture, VR teleoperation, simulation, and reinforcement learning produces more robust robot control than any single approach alone

- Transfer learning enables robots to apply movement skills learned for one task to completely different scenarios, accelerating development of diverse capabilities

Related Articles

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: Enterprise Transformation [2025]

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: The Future of Industrial Automation [2025]

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot 2028: Complete Guide & Automation Alternatives

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Press Conference Live [2026]

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Presentation Live [2025]

- CES 2026: Everything Revealed From Nvidia to Razer's AI Tools

![Human Motion & Robot Movement: How AI Learns to Walk [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/human-motion-robot-movement-how-ai-learns-to-walk-2025/image-1-1768482446534.jpg)