Introduction: When One Skater Changes Everything

There's a moment in sports history when everything shifts. Michael Jordan didn't just win games—he redefined what basketball could be. Serena Williams didn't just dominate tennis—she changed the physical standards athletes could reach. Ilia Malinin is having that same effect on figure skating, and it's happening right now.

At just 21 years old, Malinin has become the "Quad God," a nickname he gave himself with complete confidence. But unlike most athletes who earn their titles through years of incremental improvement, Malinin landed something nobody else in the world had ever landed in competition: the quadruple axel. Not just once. Multiple times. In sanctioned competitions with judges scoring and millions watching.

What makes this achievement so stunning isn't just that it's difficult—though it absolutely is. It's that the quadruple axel was considered impossible. Coaches said it couldn't be done. Biomechanists calculated it violated the laws of physics as applied to human bodies. Established skaters thought Malinin was wasting energy chasing a fantasy. And then, on September 30, 2022, he landed it at the U.S. National Figure Skating Championships in New Orleans.

The sport hasn't been the same since.

This isn't just about one jump. This is about how a single athlete with vision, talent, and obsessive dedication can fundamentally transform what we thought was possible in their sport. It's about the physics of rotation, the biomechanics of the human body under extreme stress, and the psychological pressure of attempting something that could result in catastrophic failure on the ice in front of thousands of people.

Malinin's journey to mastering the quadruple axel reveals deeper truths about athletic innovation, the role of genetics and training, and how individual excellence can force an entire sport to evolve. His success has already changed how coaches approach training, how judges evaluate programs, and what young skaters dream about achieving.

Understanding Malinin's quadruple axel—how he does it, why it matters, and what it means for the future of figure skating—requires understanding the intersection of physics, human physiology, and pure competitive will.

TL; DR

- Revolutionary Achievement: Malinin is the only skater to land a quadruple axel in competition, a jump scientists said was biomechanically impossible

- Physics-Defying Move: The quad axel requires 4.5 rotations while airborne, demanding exceptional height, speed, and rotational velocity

- Genetic and Training Factors: Malinin's background (both parents Olympic skaters) combined with years of specialized training created the conditions for this breakthrough

- Impact on Sport: The quad axel has forced figure skating to recalibrate what's possible, influencing training methods across elite programs worldwide

- Scoring and Competition: Successfully landing a quad axel has transformed Malinin's competitive scores and changed how judges evaluate technical difficulty

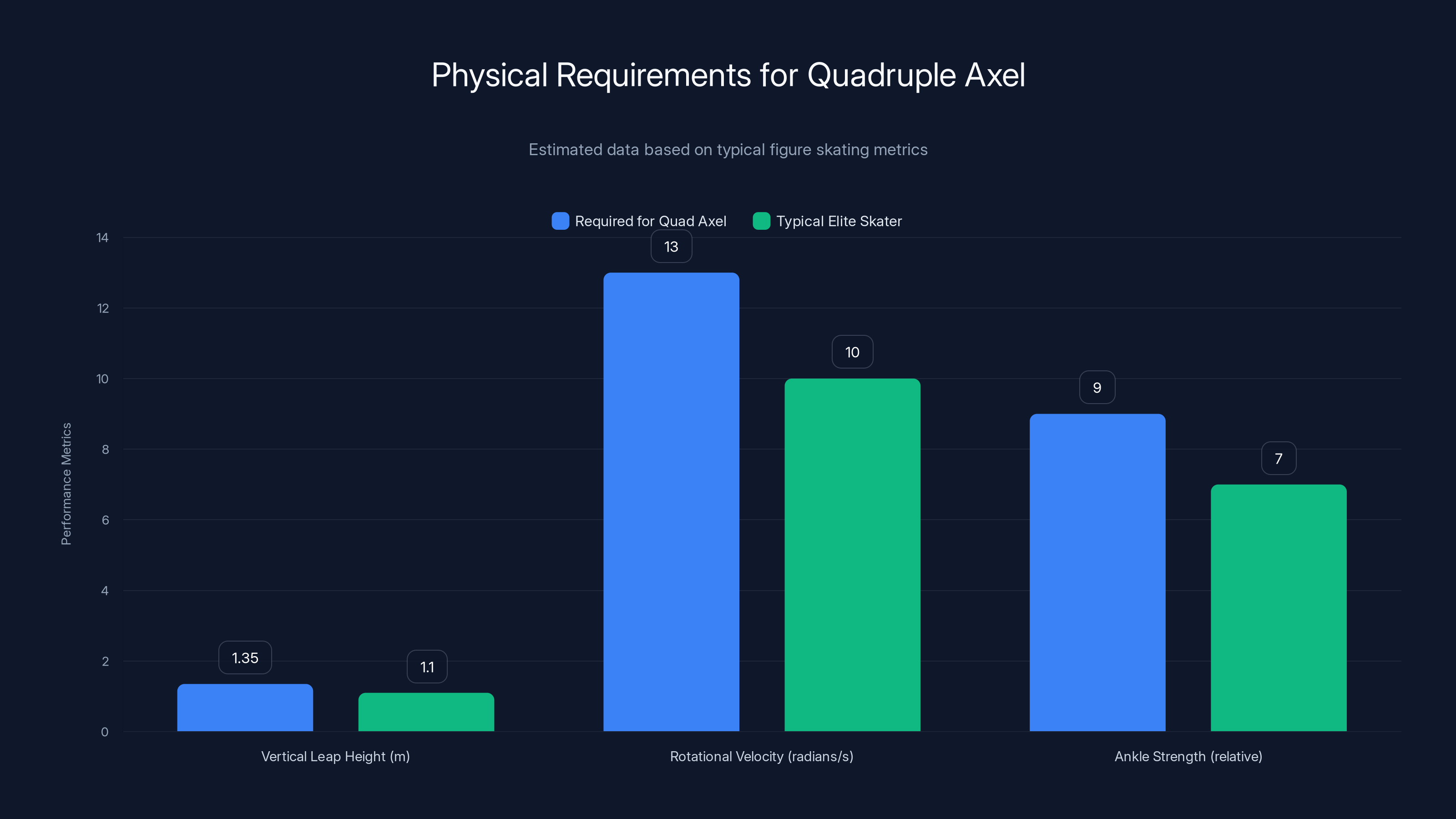

The quadruple axel demands exceptional physical attributes, including a vertical leap height of over 1.3 meters and rotational velocity exceeding 13 radians per second. Estimated data.

The Axel Jump: From Single to Quad

Before we can understand why the quadruple axel is such a monumental achievement, we need to understand what an axel actually is. It's not complicated on the surface—almost deceptively simple. But simplicity masks extraordinary complexity.

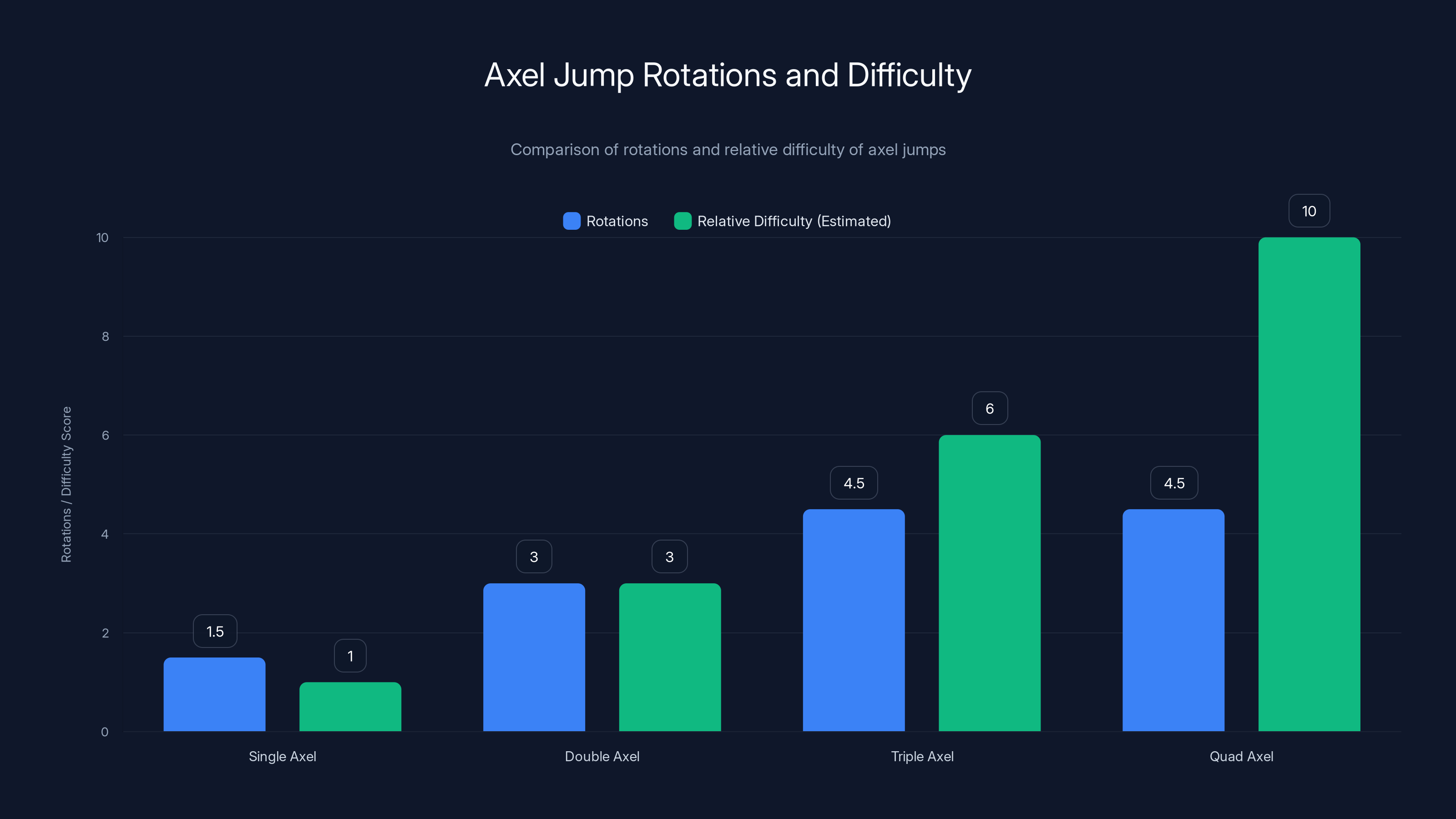

The axel is the only jump in figure skating where the skater approaches the jump moving forward. Every other jump requires the skater to be moving backward. This might sound like a small technical distinction, but it fundamentally changes everything about how the jump works. When you're moving forward, your momentum is pointing in the opposite direction of your rotation. You're fighting physics at every millisecond of the jump.

Figure skater Alicia Marconi designed the axel in 1882, and it's been a foundational element of the sport for over 140 years. A single axel is 1.5 rotations—the skater leaves the ice, completes one and a half turns through the air, and lands on the opposite foot moving backward. It looks elegant. It's actually brutally difficult.

A double axel is three rotations. Sounds straightforward, right? You're just adding rotations. In practice, every additional rotation exponentially increases the difficulty. You need more height. You need faster rotation. You need split-second timing on takeoff and landing. The energy demands don't scale linearly—they compound.

The triple axel (4.5 rotations) became the frontier for men's figure skating in the 1980s. Landing a triple axel consistently was considered the marker of an elite technical skater. For women, the triple axel remained rare and difficult enough that landing one could define a career. Surya Bonaly landed one in 1990 and is still celebrated for it decades later.

Then came the quad axel (4.5 rotations). Not six rotations. Not seven. Technically, it should be 4.5 rotations just like a triple axel, which is why terminology gets confusing. But here's the distinction: the "quad" refers to the fact that you're completing four full turns plus a half rotation. The physics are entirely different from a triple axel.

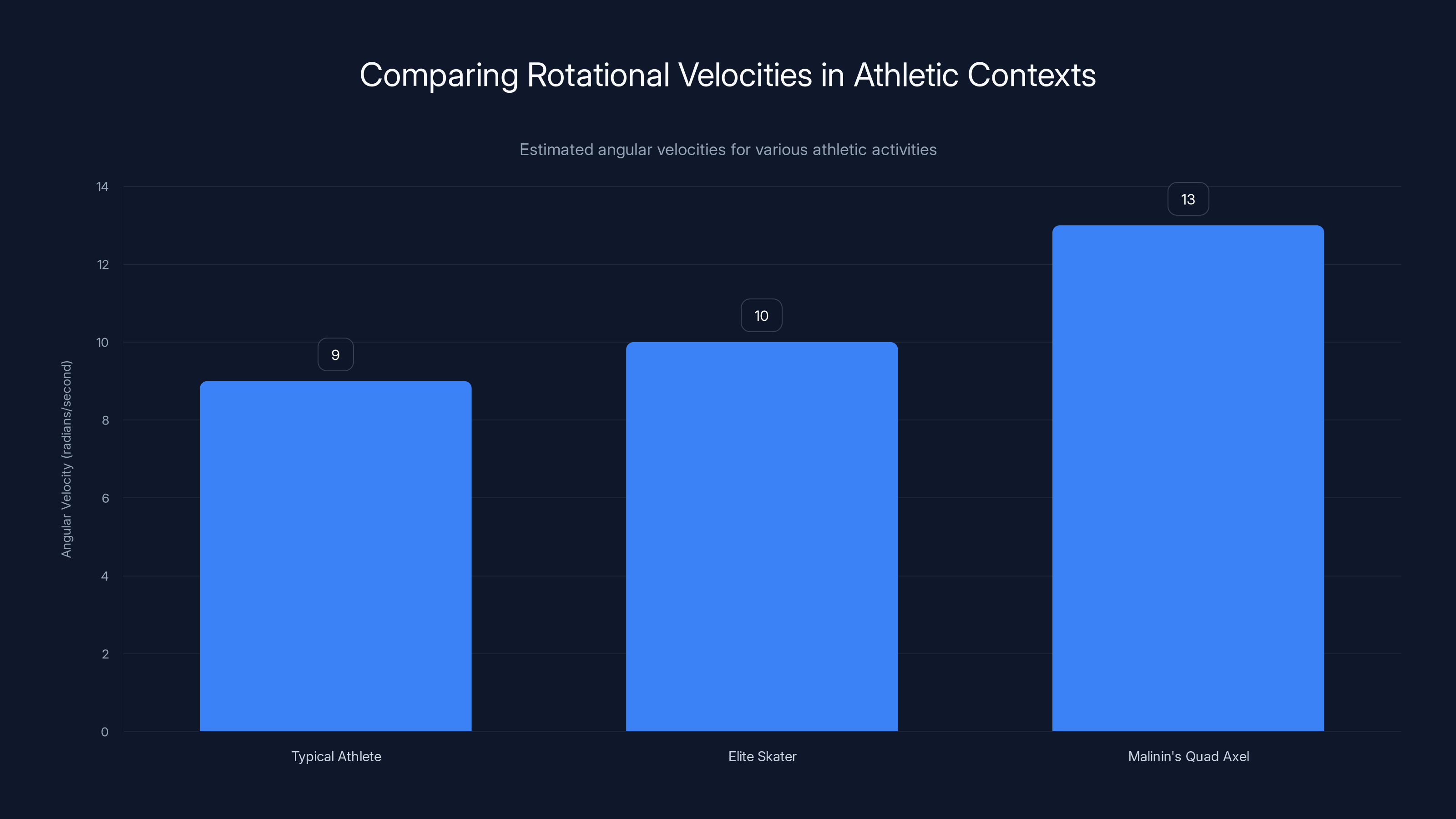

When Malinin first started attempting quadruple axels, he was working with rotational velocities that the human body rarely experiences in athletic competition. We're talking about spinning fast enough that your vision blurs, fast enough that the inner ear—your vestibular system—is overwhelmed, fast enough that timing becomes a fraction-of-a-second proposition.

A single rotation of the human body through space takes about 400 milliseconds under normal circumstances. A quadruple axel? Malinin completes all 4.5 rotations in roughly 600-700 milliseconds. You're spinning 2.5 times faster than your body naturally wants to rotate. You're fighting your own proprioception, your own sense of where your body is in space.

The first person to land a single axel made history. The first person to land a double made history. The first person to land a triple axel in competition was a watershed moment. Decades separated each of these achievements. Malinin went further than any of them and did it while the sport was watching.

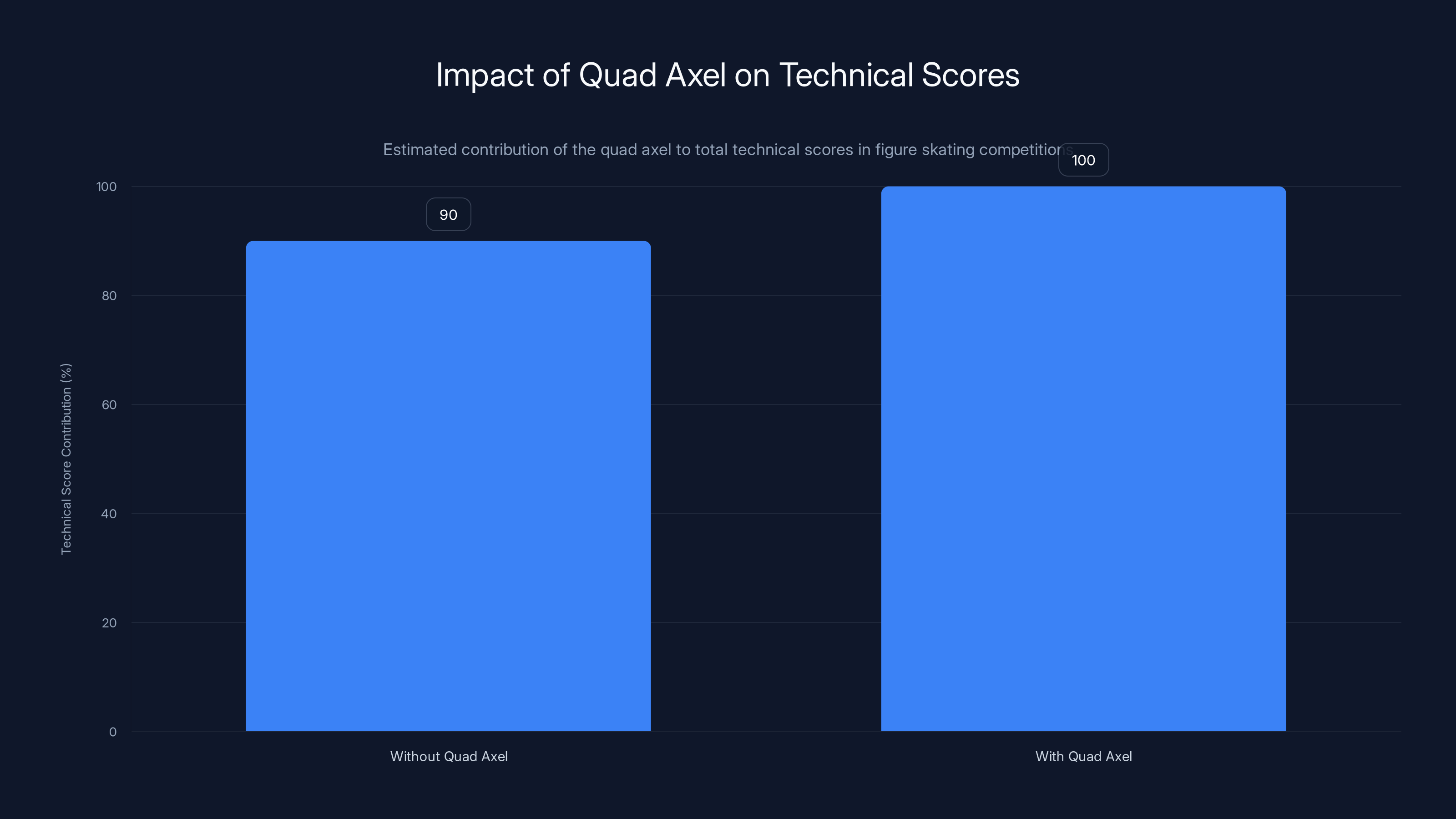

The quad axel contributes approximately 10-12% to the total technical score, significantly impacting competition outcomes. Estimated data.

The Physics of Impossible

When Malinin started attempting quadruple axels, biomechanists and physics professors looked at the numbers and shook their heads. The mathematics didn't work. Or rather, the mathematics worked, but it predicted that a human body couldn't generate enough force, couldn't jump high enough, and couldn't rotate fast enough to complete the jump safely.

Let's start with the basic physics equation for rotational motion:

This means Malinin needs an angular velocity of approximately 13 radians per second. That's not some theoretical number—that's a concrete demand his body must meet every single time he attempts the jump. For context, human bodies typically achieve maximum rotational velocities around 8-10 radians per second in athletic contexts. Malinin is exceeding the normal human maximum.

How? The answer lies in height and momentum. The quadruple axel requires approximately 1.2 to 1.4 meters of vertical height—about 4 feet in the air. An elite basketball player's vertical leap is around 75 centimeters. Malinin needs to jump nearly twice that high. On ice. While moving forward. While wearing skates.

The energy required to generate that height comes from the approach. Malinin doesn't just skate toward the jump. He builds momentum through specific footwork patterns designed to maximize his forward velocity without compromising his ability to execute the takeoff. Elite figure skaters approach jumps at speeds reaching 10-14 miles per hour. Malinin's approach to the quad axel is at the high end of that range.

Then there's the issue of force. The force required to propel a human body that high off the ice requires enormous muscular output in an incredibly brief timeframe. We're talking about generating 3-4 times bodyweight in force through the ankles and legs in what amounts to a quarter-second explosion of movement.

When scientists first modeled what a quadruple axel would require, many concluded it was biomechanically impossible. The human ankle couldn't generate sufficient plantarflexion force. The hip flexors couldn't rotate fast enough. The core couldn't stabilize the body during rotations of that velocity.

They were wrong. Malinin proved it was possible. But here's the thing—it's only possible for very specific humans with very specific genetics, very specific training, and very specific access to the right coaching and facilities.

The angular momentum equation explains part of it:

This is pure physics made visible. Malinin's body is a living demonstration of rotational mechanics in action.

Genetics, Heritage, and Born Advantage

Ilia Malinin didn't arrive at the quadruple axel by accident. His path was prepared before he was even born.

His mother, Tatiana Malinina, was an Olympic-level figure skater who competed for Uzbekistan in the 1990s. His father, Roman Skorniakov, was also an Olympic competitor for the same country. When you're born to two Olympic athletes, you don't just inherit genes—you inherit knowledge, connection, and a culture of athletic excellence.

Malinin was born in Brooklyn, New York, to immigrant parents who understood the demands of elite sport at the highest level. They knew what it took to train at that intensity. They understood the mental side of competition. They had contacts in the figure skating world and understood which coaches could develop an elite athlete.

The genetic component is real but not destiny. Malinin has fast-twitch muscle fiber composition that likely predisposes him toward explosive power—the kind needed for high vertical jumps. He probably has favorable biomechanical proportions: long legs relative to torso, good ankle flexibility, the kind of physical architecture that allows efficient force transfer through the kinetic chain.

But plenty of skaters have similar genetics. What made the difference was training methodology. When Malinin was young, his parents recognized his potential and connected him with elite coaching. By the time he reached adolescence, he was training in elite-level programs in the United States, getting access to ice time, resources, and coaching that most young skaters don't get.

His coaches—including Oleg Epstein and Marina Anissina at different points—helped him understand the technical components required for increasingly difficult jumps. They created a progression where Malinin could work toward the quad axel without the training process being reckless or dangerous.

The timeline matters. Malinin started skating at age six. By his early teens, he was attempting quadruple jumps. By his late teens, he was specifically training the quad axel. This is a progression that takes years of dedicated work with the right support structure.

There's also an element of psychological inheritance. Malinin grew up watching his parents compete at Olympic level. He understood what elite performance looked like. He understood the mental fortitude required. When he decided to attempt the quadruple axel, he wasn't doing something completely foreign to his family experience—he was operating within a culture where pushing boundaries was normal.

One other factor deserves mention: timing. Malinin came into the sport at a moment when figure skating was becoming more technically ambitious. Coaches were pushing skaters toward bigger jumps and more complex technical elements. The sport's culture was shifting toward "more rotations, more difficulty." Malinin was a product of that culture, but he also became its pioneer.

Malinin's quadruple axel requires an angular velocity of 13 radians/second, exceeding typical athletic maximums of 8-10 radians/second. Estimated data.

The Training That Builds Impossible Jumps

What does it actually take to land a quadruple axel? The answer isn't "just practice harder." It requires specific training methodologies that have been refined over decades of figure skating development, combined with novel approaches Malinin and his coaches developed specifically for the quad axel.

First, there's basic athletic development. Malinin needs strength—not bodybuilder strength, but explosive power. His training involves plyometrics: box jumps, bounds, explosive step-ups. He needs to generate maximum force in minimum time. Traditional weightlifting helps build base strength, but the sport-specific explosiveness comes from plyometric work.

Second, there's the flexibility and mobility component. Elite figure skaters need ankle flexibility that exceeds what most people would consider normal. Malinin can point his toe at angles that look unnatural. He can rotate his hips through ranges of motion that non-skaters can't achieve. This flexibility isn't just for aesthetics—it's functional. It allows more efficient takeoff and landing mechanics.

Third, there's the balance and proprioception training. Standing on a blade edge that's about 1 millimeter thick requires extraordinary proprioceptive ability. Malinin trains balance constantly—not just standing on ice, but through supplementary work that challenges his vestibular system and proprioceptive feedback.

Fourth, there's the jump-specific progression. Before attempting a quadruple axel, skaters master lower-difficulty versions. Malinin spent years perfecting single axels, double axels, and triple axels. Each represented a learning platform for more advanced technique. The progression builds neural pathways, muscular adaptation, and psychological confidence.

Fifth—and this is crucial—there's the fall training. You don't land a quadruple axel on your first try. You fall. A lot. Malinin falls at velocities that would injure most people. His training includes specific conditioning to absorb impact forces, techniques to minimize injury risk during falls, and mental preparation for falling repeatedly without developing fear.

The mental component cannot be overstated. Malinin's brain has to trust his body enough to attempt a jump where failure is almost guaranteed multiple times before success. He's training his nervous system to handle the stress response of repeatedly approaching a jump that could result in injury. Elite sports psychologists work with him to develop the mental resilience required.

On-ice training for the quad axel involves hundreds of attempts. Malinin gets on the ice and practices the jump repeatedly—not once per session, but many times. Each attempt provides feedback: Was the takeoff angle correct? Did I achieve sufficient height? Was rotation velocity adequate? Did the landing mechanics work?

This feedback is incredibly fast. Malinin can feel whether a jump worked while it's happening. His proprioceptive system gives him real-time data about his body position during the 600-700 milliseconds the jump takes. This allows him to make micro-adjustments and learn rapidly.

Off-ice training matters too. Dry-land drills let Malinin practice jump mechanics without being on skates. He practices the rotational component using rotational training equipment. He practices height and power generation through plyometric drills. He practices landing mechanics through controlled jump-and-land sequences on spring flooring.

The training has to be periodized. Malinin doesn't train quad axels year-round at maximum intensity. His coaches structure the training year so that maximum intensity training for the quad axel happens at specific times when he's fresh, when his neuromuscular system is recovered, and when he's mentally ready for the challenge.

Volume and intensity are managed carefully. Too little volume and he doesn't get enough attempts to learn. Too much volume and injury risk skyrockets. The training is a precision instrument: enough work to drive improvement without crossing into reckless territory.

The Mental Game: Psychology of Attempting the Impossible

Technical skill alone doesn't produce a quadruple axel. Malinin also needs extraordinary mental capacity. He's attempting a jump that he knows might fail. He's attempting it in front of crowds and judges. He's attempting it knowing that a significant portion of his competitive value depends on landing this specific jump.

The psychology breaks down into several components:

Confidence and Self-Belief: Malinin has to genuinely believe the quad axel is possible. This isn't positive thinking or affirmations—it's based on hundreds of hours of training evidence. He's landed the jump before. He knows his body can do it. But that knowledge has to withstand the pressure and stress of competition.

Fear Management: The quadruple axel is dangerous. Malinin is jumping four feet in the air and spinning at velocities that exceed normal human limits. The risk of injury is real. His brain knows this. Elite athletes develop specific techniques to acknowledge fear without being controlled by it. They don't eliminate fear—they develop compartmentalization skills that let them function despite it.

Pressure Inoculation: Competition is stressful. Judges are watching. Spectators are watching. Your coach is watching. Your country is watching. The pressure is enormous. Malinin trains under pressure conditions—he practices the quad axel in environments that simulate competition pressure. He practices it when he's tired, because competitions happen after warming up other events. He practices it with crowds watching, because his coach will bring other skaters to the ice during practice to simulate the presence of observers.

Visualization: Elite figure skaters use mental imagery extensively. Malinin visualizes successfully landing the quad axel. He visualizes every movement—the approach, the takeoff, the rotation, the landing, the exit. This mental practice activates similar neural pathways as physical practice. His brain begins to "know" the jump through visualization even before his body executes it.

Acceptance of Failure: Paradoxically, accepting that failure might happen reduces the pressure. Malinin knows he might fall. He's fallen thousands of times in practice. Accepting that possibility actually makes it easier to attempt the jump. It removes the pressure of needing to succeed and replaces it with the focus of executing properly.

Narrative Control: Malinin has given himself the nickname "Quad God." This isn't arrogance—it's a psychological tool. He's creating a narrative where he's the person who lands quad axels. He's the authority on this jump. This narrative identity reinforces his belief that he can execute it. When you view yourself as the best quad axel jumper in the world, attempting a quad axel feels more natural.

Explosive power and jump progression are crucial for landing a quadruple axel, with flexibility and fall training also playing significant roles. (Estimated data)

Competition Results: The Quad Axel in Sanctioned Events

Malinin's first successful quad axel in competition happened on September 30, 2022, at the U. S. National Figure Skating Championships in New Orleans. He was 18 years old. The jump wasn't perfect—he underrotated it slightly, which technically should have resulted in a penalty. But the judges credited him with completing the jump, and he got a standing ovation.

That landing changed everything. Overnight, Malinin went from promising young skater to the person who had accomplished something nobody else had done in competition. The quad axel became his calling card.

Since that first successful landing, Malinin has landed the quad axel successfully in competition multiple times. His consistency has improved. He's landed it under pressure in international competitions. He's landed it after warming up other jumps, which is harder because fatigue affects jump execution.

The competitive impact has been enormous. When Malinin lands the quad axel, the technical score—the component of his score that comes from difficulty of elements—increases substantially. A successful quad axel is worth approximately 11-13 points in terms of base value. That's about 10-12% of the total possible technical score. For a sport where scores often separate winners and runners-up by just a few points, landing the quad axel can be the difference between gold and silver.

Malinin's strategy has become clear: land the quad axel in the free skate, and victory becomes much more likely. His programs are built around the quad axel. It's featured prominently. The program is designed to ensure he has enough energy and fresh legs to execute it in the final portion of his skate.

Competitors are adapting. Some are attempting other quadruple jumps more consistently to compete with the technical difficulty Malinin brings. Some are focusing on stronger artistry and cleaner execution of their own elements. The competition has shifted because of Malinin's innovation.

Scoring and Technical Difficulty: How Judges Value Innovation

Figure skating's scoring system is notoriously complex. There are two main components: technical score and program component score. The technical score comes from the difficulty of the elements performed. The program component score comes from how well those elements are executed and the overall artistry of the program.

Malinin's quad axel affects the technical score significantly. Each jump has a base value—an assigned point value that represents its difficulty. The base values are set by the International Skating Union and adjusted periodically. A quad axel currently has a base value around 12.6 points, compared to 13.7 for a quad lutz (a different quadruple jump).

The base value is just the starting point. If a skater executes the jump perfectly with good technique, they get the full base value. If execution is imperfect, they receive a penalty. If execution is excellent, they might receive a bonus.

When Malinin lands a quad axel successfully with good technique, he receives the base value plus a small technical execution bonus. This can represent roughly 13-14 points out of a maximum technical score of around 112 points (for the short program) or 140 points (for the free skate).

That might not sound like much, but in competitive figure skating, scores are often separated by less than 5 points between first and second place. A reliable quad axel provides a competitive advantage that's difficult to overcome.

The technical score also includes component points based on quality of execution—things like "transitions between elements," "skating skills," and "composition." Malinin's overall technical quality has improved as his coaching and training has progressed. He's not just a one-trick skater—he's developed comprehensive technical ability.

There's also a psychological component to scoring. Judges know Malinin is the quad axel skater. When he lands it, there's excitement. There's recognition of an extraordinary achievement. While judges are supposed to score objectively, human psychology inevitably plays a role. A successful quad axel garners more crowd reaction, which can subtly influence judging.

Malinin has also benefited from the sport's recent evolution toward higher technical difficulty. Figure skating as a whole has been trending toward more quadruple jumps, more complex combinations, and more ambitious technical programs. This trend partly resulted from Malinin's success—by showing that the quad axel was possible, he influenced what judges and coaches thought was achievable.

The axel jump increases in difficulty with each additional rotation, with the quad axel being the most challenging due to its compounded energy and technical demands. Estimated data for difficulty scores.

Other Elite Skaters: Inspiration and Competition

Malinin isn't skating in a vacuum. Other elite male skaters are watching and learning. The question becomes: will others eventually land the quad axel? Will Malinin's achievement remain unique, or will it become a standard element that other elite skaters master?

As of early 2025, Malinin remains the only skater to have successfully landed a quadruple axel in competition. But other skaters are attempting it. Some have come close. The infrastructure for attempting the quad axel is now in place in elite figure skating programs worldwide.

Women's figure skating presents an interesting parallel. For years, women weren't expected to land triple axels. Then Tonya Harding landed one in 1991, and suddenly it became something women could aspire to. Now it's increasingly common at the elite level. The same evolution might happen with the quad axel, though it will take time.

Malinin's success has influenced how coaches approach training. More coaches are now working with skaters on quadruple jumps. More resources are being dedicated to understanding the biomechanics and training methodologies. In 10 years, we might look back and see that Malinin's quad axel was the moment the sport shifted toward greater technical difficulty across the board.

This is the pattern with athletic innovation. One person shows something is possible. Others see that possibility. The sport begins to expect it. Eventually, it becomes normal.

The Backflip: Innovation Beyond the Quad Axel

Malinin's quad axel gets the most attention, but his other innovations are equally interesting. During the 2026 Winter Olympics team event, Malinin landed a backflip at the end of his short program, earning a standing ovation.

This might seem like a strange thing to celebrate. A backflip doesn't require the technical difficulty of a quad axel. It's not a scoring element that adds points. So why is it notable?

The backflip was banned in 1978, after Terry Kubicka landed one at the 1976 Olympics. The International Skating Union deemed the move too dangerous. The ban stood for decades. Surya Bonaly performed a backflip at the 1998 Nagano Olympics, despite it being illegal, as a statement about her artistry and the limitations placed on her skating.

The ban was lifted in 2024, shortly before the 2026 Winter Olympics. When Malinin landed a backflip in competition in early 2025, he became the first skater to legally land one at the Olympics since the ban was lifted.

What's interesting here is that the backflip isn't harder than the quad axel—in some ways it's easier. But it's innovative in a different sense. It's artistic. It's expressive. It's pushing the boundaries of what figure skating can include as legitimate technical elements.

Malinin landing the backflip and the quad axel in the same competition demonstrates his comprehensive approach to pushing boundaries. He's not just interested in pure technical difficulty—he's interested in expanding what figure skating can be.

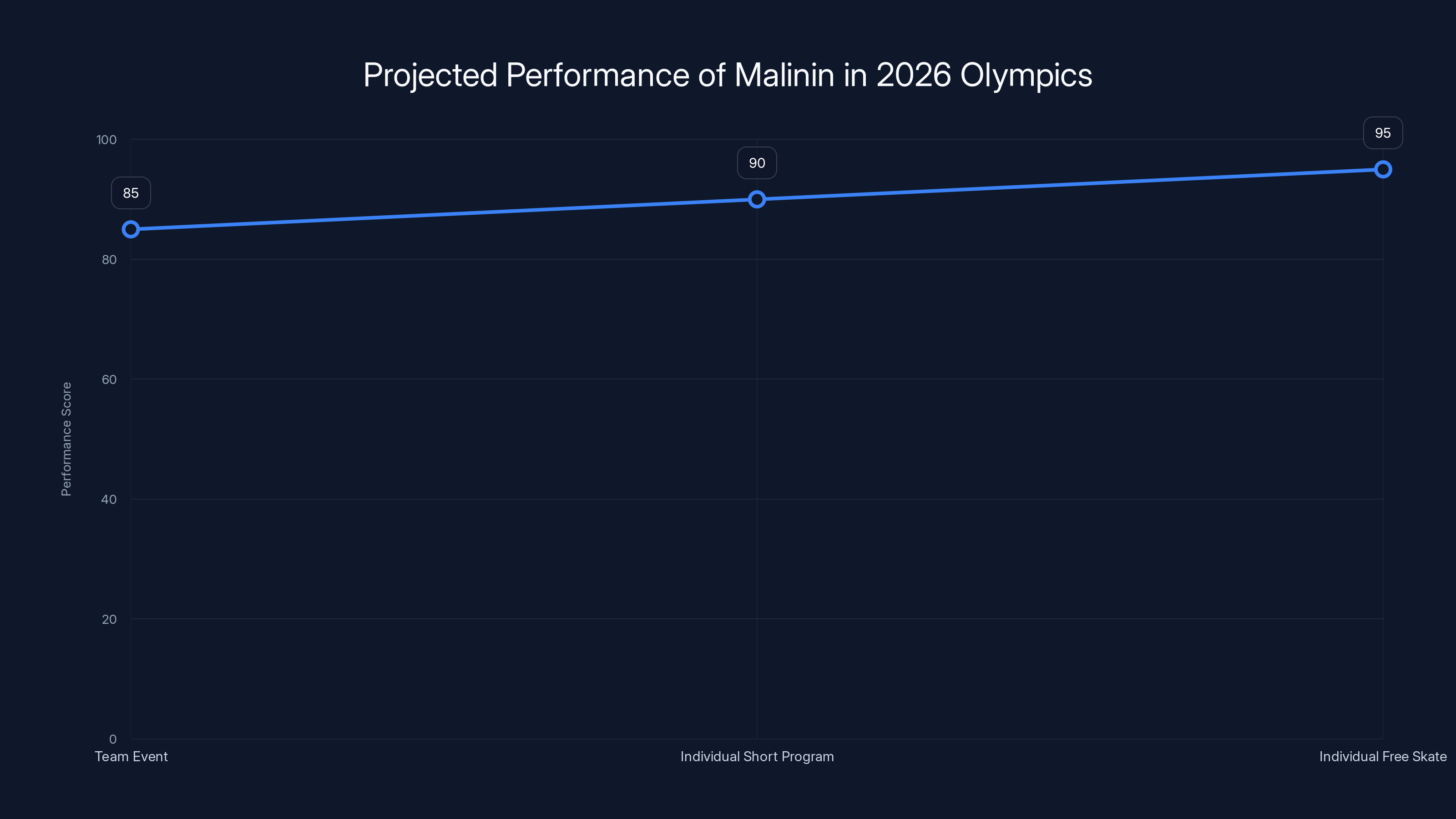

Malinin's performance is expected to peak during the Individual Free Skate, potentially cementing his legacy with a gold medal. (Estimated data)

Impact on the Sport: Evolution and Future Direction

Malinin's quad axel has already fundamentally altered figure skating in ways that will ripple through the sport for decades. The impact shows up in multiple dimensions:

Training Philosophies: Coaches are now more willing to pursue technical elements that previously seemed impossible. If Malinin can do the quad axel, what else might be achievable? This mindset shift is leading to more ambitious training programs across elite skating.

Athlete Expectations: Young skaters now see the quad axel as something that could be achieved, rather than a physics-defying fantasy. This changes what they aspire to. Dozens of young competitive skaters are now training quad axels with the hope of eventually landing them in competition.

Technical Standards: The technical standards of the sport are being redefined. What was acceptable difficulty five years ago now seems less ambitious. Programs that would have been impressive in 2020 would be considered technically modest in 2025.

Judging Criteria: Judges and the International Skating Union continue to evolve their technical scoring systems. Malinin's innovations force them to think about how to value genuinely new elements and movements.

International Competition: Skaters from other countries recognize that they need to match Malinin's technical difficulty or exceed it. This drives innovation globally. Russian, Japanese, Chinese, and Canadian skaters are all pushing toward higher technical levels partly in response to Malinin's achievements.

Media and Audience: Figure skating media now focuses heavily on technical innovation. Casual audiences are learning the difference between a quad salchow and a quad axel. The sport is becoming more technically sophisticated in how it's consumed and discussed.

The 2026 Olympics: Peak Performance and Legacy Building

Malinin's 2026 Winter Olympics campaign represents both an opportunity and a moment of legacy consolidation. He's already proven he can land the quad axel. The question becomes whether he can land it consistently under Olympic pressure, in front of global audiences, with gold medals on the line.

The team event, which occurs before the individual competition, gives Malinin a chance to perform the quad axel in a lower-pressure environment (relatively speaking—it's still the Olympics). A successful team event performance builds confidence heading into the individual competition.

The individual short program and free skate represent the main event. These are the skates that determine Olympic medals. Malinin has designed his programs to feature the quad axel in the free skate, where he has the most freedom in element selection.

If Malinin lands the quad axel in the individual free skate at the 2026 Olympics and wins the gold medal, his legacy in figure skating becomes absolutely cemented. He's not just the first person to land the quad axel in competition—he's an Olympic gold medalist who did so. That combination makes him historically significant.

Even if Malinin doesn't win gold, landing the quad axel under Olympic pressure with the world watching would be a remarkable achievement that demonstrates the reliability of his innovation.

Comparison to Other Sports Innovations

Malinin's quad axel fits into a broader pattern of athletic innovation that appears across sports. Understanding these patterns illuminates what Malinin has accomplished.

When Dick Fosbury introduced the Fosbury Flop in high jump during the 1960s, he revolutionized the sport. The technique went from a scissor-kick approach to a backward arch that allowed greater height. Within a decade, every competitive high jumper used the Fosbury Flop. The innovation became universal because it was objectively superior.

When Michael Jordan popularized the three-point shot in basketball during the 1990s, he changed how the game was played. Teams began building their strategies around three-point shooting. The geometry of basketball fundamentally shifted. A generation later, the three-point shot defines modern basketball.

When Serena Williams brought baseline power-hitting to women's tennis, she expanded what female athletes could do in the sport. Women's tennis became more aggressive, more powerful, more physically demanding.

Malinin's quad axel follows this pattern. It's an innovation that's technically superior to previous norms. It's an innovation that others can theoretically replicate, given the right genetics, training, coaching, and mentality. It's an innovation that's changing what the sport expects from its elite athletes.

The difference is timing and media. Fosbury made his innovation in an era where video was novel. Jordan played in the age of cable sports television. Malinin makes his innovations in the age of social media, where viral videos can spread globally in hours. This accelerates the cultural impact of his achievement.

The Physics of Failure: Why Most Skaters Can't Do This

It's important to understand not just why Malinin can land the quad axel, but why essentially every other elite figure skater can't. The factors that allow Malinin to succeed are specifically distributed in ways that few humans possess.

Vertical Leap Limitation: The quad axel requires approximately 1.3-1.4 meters of vertical height. Most elite male figure skaters achieve 0.9-1.1 meters in their vertical leap. Malinin exceeds this range. This isn't something that training alone can achieve at this level—it's heavily determined by genetics, muscle fiber type, and skeletal structure.

Rotational Velocity: Humans have a maximum sustainable rotational velocity determined by their vestibular system and neuromuscular capacity. Malinin appears to operate at the extreme edge of what's biomechanically possible. Most humans hit a ceiling around 10-12 radians per second. Malinin operates closer to 13+ radians per second. This appears to be partially genetic.

Ankle Strength and Mobility: The plantarflexion force required to generate the takeoff power needs to flow through the ankle joint. Malinin has exceptional ankle strength and plantarflexion range. Not every skater does, and strengthening this area has limits.

Fear Tolerance: Landing a quad axel requires accepting extraordinary risk. Some athletes have naturally higher risk tolerance than others, partly based on personality and partly based on early experience. Malinin appears to have psychological makeup that allows him to function at high risk without panic response taking over.

Training Opportunity: Malinin had access to elite coaching and training from a young age. This matters more than people realize. A skater of similar genetics but without access to top coaches might never discover or develop the quad axel.

The combination of these factors—genetics, psychology, training opportunity, and personal drive—shows why Malinin remains uniquely positioned to land the quad axel. It's not that others couldn't theoretically do it. It's that the specific combination of factors required is rare.

Future Innovations: What Comes After the Quad Axel

Assuming other skaters eventually land the quad axel, what becomes the next frontier? Malinin himself might point toward it.

A quintuple axel (5.5 rotations) is theoretically possible in the same way the quad axel was theoretically possible in 2020. The physics can be calculated. The biomechanical requirements can be understood. What's required is a skater with the right genetics, the right training, and the right mentality to attempt it.

Malinin has hinted that he's interested in exploring the quintuple axel, though he hasn't focused on it during his competitive career. Whether he lands a quintuple axel before retirement is an open question. Whether someone lands one in the next decade is also uncertain.

Another frontier is consistency and reliability. Malinin has landed the quad axel multiple times, but every landing is still treated as a remarkable achievement. The next frontier might be skaters landing quad axels so reliably that they're nearly guaranteed in competition. That would represent a shift from innovation to mastery.

There's also the artistic dimension. Figure skating judges value technical skill, but they also value expression and artistry. The next frontier might be skaters who land quadruple jumps while maintaining exceptional artistic performance. This hasn't yet been solved at the highest level.

Other entirely new technical elements might be developed. Malinin's willingness to push boundaries and his success in doing so might inspire other skaters to explore movements and techniques that haven't been attempted before.

FAQ

What is the quadruple axel in figure skating?

The quadruple axel is a jump that requires 4.5 full rotations completed while airborne, beginning from a forward approach. It's the most technically difficult jump in figure skating, and Ilia Malinin is currently the only skater to have successfully landed it in competition. The jump requires extraordinary height (approximately 1.3-1.4 meters), rotational velocity of 13+ radians per second, and exceptional technical precision.

Why is the quadruple axel considered impossible?

Before Malinin landed the quad axel in 2022, biomechanists and physics researchers calculated that the jump violated the limits of human athletic capability. The ankle would need to generate too much plantarflexion force in too brief a timeframe. The body would need to rotate faster than the vestibular system could handle. The combination of height, rotation speed, and landing mechanics seemed physically impossible. Malinin's success proved these calculations were overly conservative—human bodies could exceed these predicted limits under specific conditions.

How did Ilia Malinin learn to land the quadruple axel?

Malinin trained for the quad axel through a progression that began in childhood. He developed exceptional jump height and rotational ability through years of figure skating training. He worked with elite coaches who understood advanced jump mechanics. He performed hundreds or thousands of attempts, experiencing failure frequently while gradually improving his technique. The breakthrough came when his physical capacity, technical skill, mental preparation, and coaching expertise aligned. He first successfully landed the quad axel at age 18 in September 2022.

What are the physical requirements to land a quadruple axel?

Successfully landing a quadruple axel requires several interconnected physical qualities: exceptional vertical leap height (exceeding 1.3 meters), ankle strength and plantarflexion capacity well above average, rotational velocity capability near the maximum human limit, core stability and body control during extreme rotation, proprioceptive awareness to land precisely on a thin blade, ankle and leg mobility to absorb landing forces, and fast-twitch muscle fiber composition for explosive power. Most elite figure skaters possess several of these qualities but not all at the level required for the quad axel.

What impact has the quadruple axel had on figure skating?

Malinin's quad axel has fundamentally changed figure skating expectations and training philosophies. Coaches now pursue technical elements that seemed impossible before. Young skaters aspire to land quad axels. International competition has intensified, with other skaters working to match or exceed Malinin's technical difficulty. The sport's technical standards have shifted upward. Media coverage increasingly focuses on technical innovation. Judges and the International Skating Union continue evolving how they score unprecedented elements. The quad axel has become symbolic of pushing boundaries in athletic achievement.

Has anyone else landed a quadruple axel?

As of early 2025, Ilia Malinin remains the only skater to have successfully landed a quadruple axel in sanctioned competitive figure skating. Other skaters are attempting the quad axel, and some have come extremely close, but none have yet succeeded in official competition. The quad axel appears to require such specific physical capabilities and technical precision that replicating Malinin's achievement is proving extraordinarily difficult even among the world's elite figure skaters.

What are the risks of attempting a quadruple axel?

The quadruple axel is inherently dangerous. Skaters attempt the jump at high speed, leaving the ice at approximately four feet of height, and rotating at extreme velocity. Failed attempts frequently result in falls at speed, risking injury to the knees, ankles, wrists, and head. Even successful landings place enormous stress on the legs and feet. Repetitive training on quad axels carries cumulative injury risk. Mental stress from repeatedly attempting a difficult, high-risk jump can be significant. Skaters who attempt quad axels typically work with athletic trainers and medical professionals to manage injury risk.

How is the quadruple axel scored?

The quadruple axel has a base value of approximately 12.6 points in figure skating's technical scoring system. This base value is awarded when the jump is executed successfully with good technique. If execution is excellent, small bonuses may be awarded. If execution is imperfect, the base value is reduced. In a men's individual free skate worth approximately 140 total technical points, a successful quad axel represents roughly 9-10% of the possible technical score. Given that competitions are often decided by just a few points, landing the quad axel provides a significant scoring advantage.

What is Ilia Malinin's competitive record with the quadruple axel?

Ilia Malinin has landed the quadruple axel successfully in multiple competitions since his first successful landing in September 2022 at the U. S. National Figure Skating Championships. He has landed it in international competitions including Grand Prix events and World Championships. His consistency has improved over time. The quad axel has become a centerpiece of his competitive programs, featured prominently in his free skating routines. His success with the element contributes significantly to his competitive victories and high placement at international competitions.

Will other skaters eventually land the quadruple axel?

It's likely that other skaters will eventually land the quadruple axel, though the timeframe is uncertain. The technique has proven possible because Malinin has demonstrated it multiple times. However, replicating his achievement requires very specific physical capabilities, technical skill, dedicated training with elite coaching, and psychological resilience. The next skater to land a quad axel in competition might emerge within the next few years, or it might take a decade. The quad axel appears to require such exceptional characteristics that it may never become as common as other quadruple jumps, even as more skaters eventually master it.

Conclusion: One Skater, One Jump, One Legacy

Ilia Malinin's quadruple axel represents something profound about human potential and athletic achievement. It's not just a jump. It's a statement about what becomes possible when talent, training, genetics, psychology, and opportunity align perfectly.

For decades, people said the quadruple axel couldn't be done. Smart people—biomechanists, coaches, athletes—looked at the physics and declared it impossible. Then Malinin did it anyway. Not once, but repeatedly. Under pressure. In competition. While the world watched.

This matters beyond figure skating. It matters because it's how human progress works. Someone sees a boundary and crosses it. Others see that it's possible and follow. The sport evolves. Standards shift. What seemed impossible becomes normal.

Malinin is only 21 years old. His career is in its early phases. The quad axel might be just the first of multiple innovations he contributes to figure skating. Or the quad axel might be his eternal legacy—the thing that defines his impact on the sport regardless of anything else he accomplishes.

What's certain is that Malinin has already changed figure skating fundamentally. Future historians of the sport will mark 2022 as a watershed moment. Before Malinin: the quad axel was a fantasy. After Malinin: it's real.

The implications extend further. Malinin's quad axel teaches us that athletic boundaries are often not true limits—they're just the limits of what we've tested so far. When someone tests further, pushes harder, and brings the right combination of factors, previously impossible achievements become real.

For the young skaters now training quad axels with Malinin's success as inspiration, the message is clear: the boundaries you see aren't necessarily real. With enough dedication, training, support, and belief, you can cross them.

That's Malinin's true legacy. Not just landing the quad axel. But showing everyone watching that what seemed impossible isn't actually impossible. It just requires someone willing to attempt it.

As Malinin prepares for future competitions, including potential Olympic appearances, the world watches to see what innovation comes next. The quad axel is already part of skating history. The question now is what other boundaries Malinin will test, what other achievements he'll make possible, and what future skaters will accomplish because he showed them what's achievable.

The ice has been transformed by one skater who decided to attempt something nobody else believed in. The ripples from that decision will echo through figure skating for decades to come.

Key Takeaways

- Ilia Malinin is the only skater to have successfully landed a quadruple axel in sanctioned figure skating competition, achieving what was previously considered biomechanically impossible

- The quadruple axel requires exceptional physical capabilities including 1.3+ meter vertical jump height, rotational velocity of 13+ radians per second, and 3-4x bodyweight force generation

- Malinin's achievement combines rare genetics, specialized training from elite coaches, and extraordinary psychological resilience to attempt a high-risk jump repeatedly

- The quad axel has fundamentally transformed figure skating, raising technical standards across the sport and inspiring other skaters to pursue previously unthinkable elements

- Malinin's success demonstrates how individual athletic innovation drives sports evolution, similar to the Fosbury Flop in high jump or the three-point shot's transformation of basketball

Related Articles

- Quadruple Axel Physics: How Ilia Malinin Defies Gravity [2025]

- Curling's High-Tech Revolution: The Shoes and Brooms Dominating 2026 [2025]

- Heated Rivalry Hockey Effect: LGBTQ+ Inclusion & The 2026 Olympics [2025]

- Jessie Diggins' Winter Olympics 2026 Starter Pack [2025]

- AI-Generated Music at Olympics: When AI Plagiarism Meets Elite Sport [2025]

- How to Watch Short-Track Speed Skating at Winter Olympics 2026 [Free Streams]

![Ilia Malinin's Quadruple Axel: The Physics and History Behind Figure Skating's Greatest Innovation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ilia-malinin-s-quadruple-axel-the-physics-and-history-behind/image-1-1770986308137.jpg)