The Moment That Changed Figure Skating Forever

It was a Monday night at the Olympics when NBC commentators casually dropped a bombshell. As Kateřina Mrázková and Daniel Mrázek performed their rhythm dance, one announcer mentioned in passing: "This is AI generated, this first part." That single sentence exposed something far bigger than a couple of Czech siblings trying to save on licensing fees.

Here's the thing: the music wasn't just AI-generated. It was plagiarized AI-generated music.

The pair had used a platform to create a song "in the style of Bon Jovi," and what came back was basically a Bon Jovi song—complete with his actual lyrics, his vocal pattern, and even lines that appeared note-for-note in his 1990s catalog. When they performed on the world's biggest stage, millions of viewers watched as these elite athletes danced to intellectual property theft set to music.

But the story gets worse. This wasn't even their first rodeo with this problem. Just months earlier, the same duo had attempted a rhythm dance to AI music that opened with "Every night we smash a Mercedes Benz"—a direct lyric from New Radicals' "You Get What You Give" (MusicRadar). The AI system didn't just borrow a vibe or aesthetic. It regurgitated actual lyrics from a song that had nothing to do with their requested style.

So what happened? How did two Olympic athletes end up at the center of a plagiarism scandal? And more importantly, what does this tell us about where artificial intelligence actually is right now, beneath all the hype?

This is about more than ice skating. It's about how large language models work, why they do what they do, and why the music industry—and every creative industry—should be genuinely worried.

TL; DR

- Czech ice dancers used AI music at the Olympics that plagiarized lyrics from "You Get What You Give" and Bon Jovi songs without permission (People)

- LLMs don't "create"—they predict statistically probable text based on training data, which often includes copyrighted material scraped without consent (UNESCO)

- This isn't a glitch, it's a feature of how these systems work, making plagiarism almost inevitable for creative tasks (Bloomberg Law)

- The real problem is training data sources, not the models themselves—most music AI systems trained on vast libraries without artist permission (IPWatchdog)

- Olympics rules don't prohibit AI music, but intellectual property laws do, creating a legal gray zone that nobody's figured out yet (Yahoo Sports)

- This signals a creativity crisis where AI tools can produce output that sounds professional but steals from actual artists (Brobible)

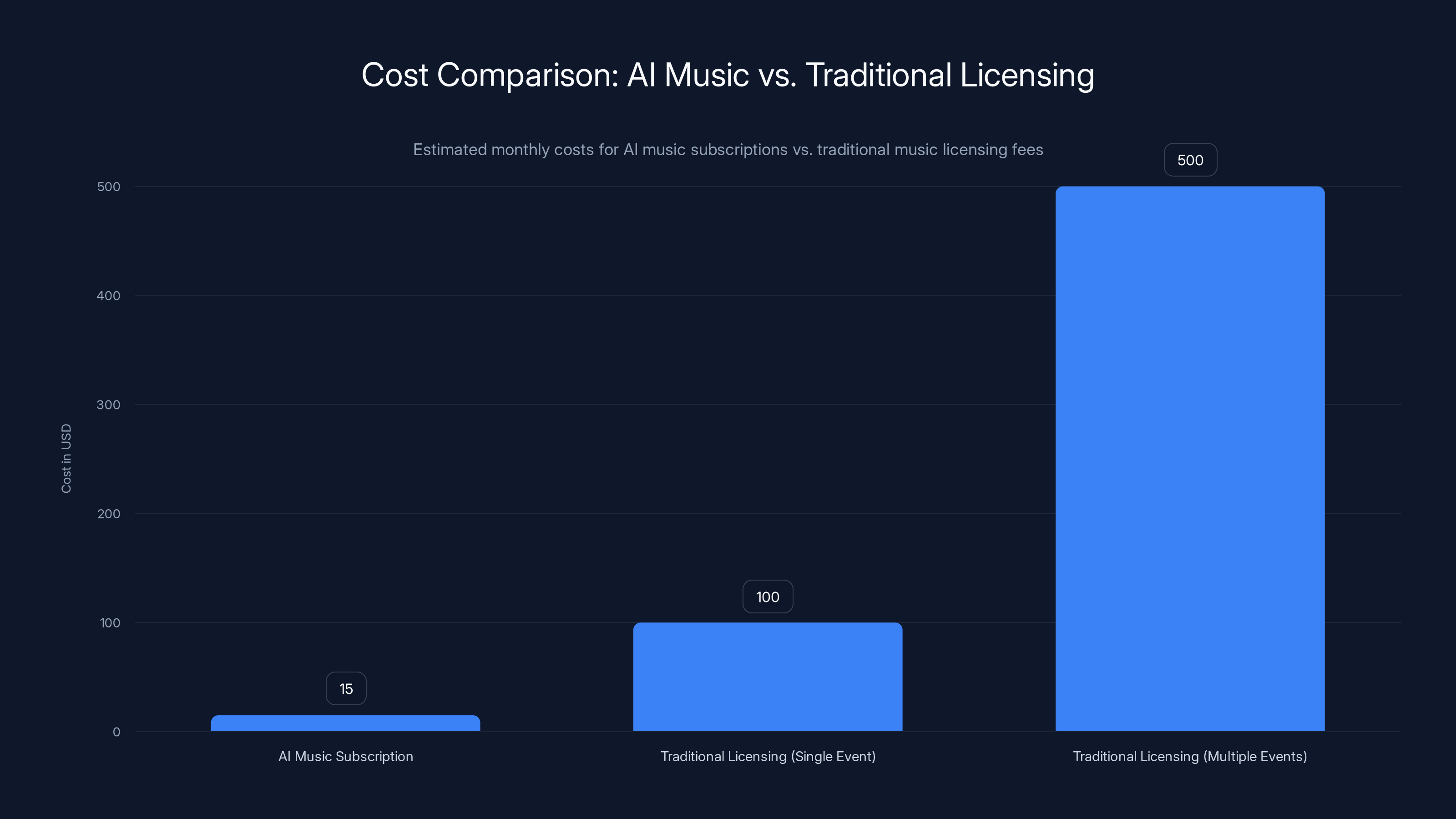

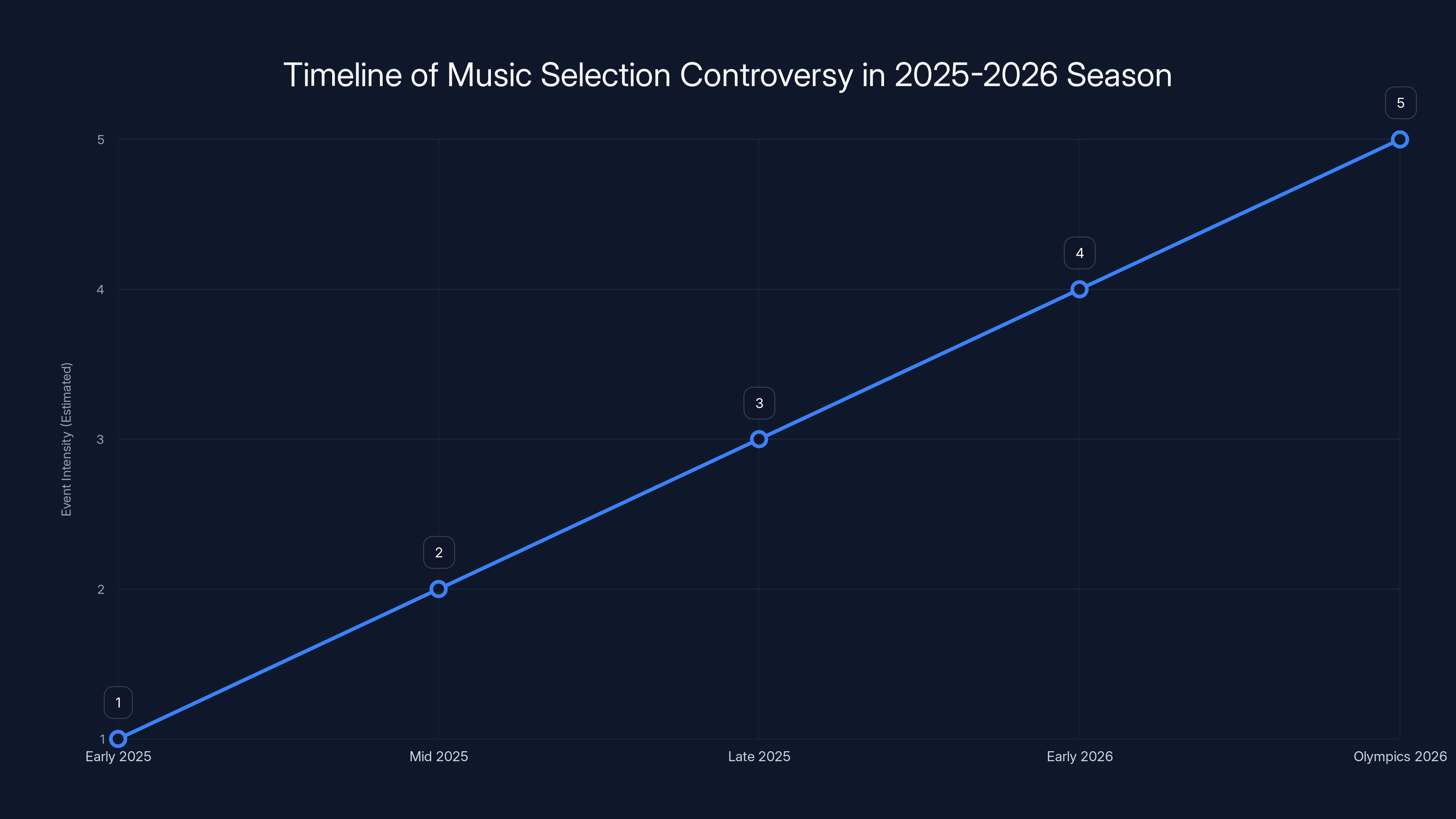

AI music subscriptions are significantly cheaper than traditional licensing, especially for athletes performing at multiple events. Estimated data.

What Actually Happened: The Timeline of a Disaster

Let's back up and understand the sequence of events, because this wasn't a single mistake. It was a pattern.

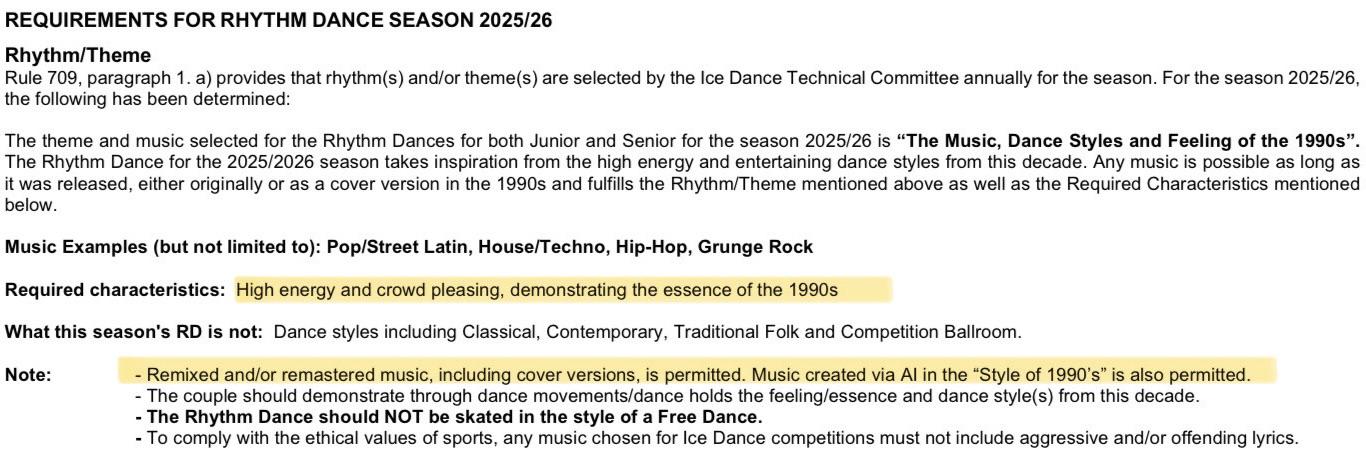

Earlier in the 2025-2026 competitive season, Mrázková and Mrázek needed music for their rhythm dance. The Olympic ice dance competition that year had a theme: "The Music, Dance Styles, and Feeling of the 1990s." Other teams picked obvious choices. British dancers Lilah Fear and Lewis Gibson went with the Spice Girls. American favorites Madison Chock and Evan Bates chose a Lenny Kravitz medley (US Figure Skating).

But Mrázková and Mrázek chose a different path. For whatever reason—maybe licensing costs were too high, maybe they wanted to experiment, maybe they just wanted to try something different—they generated their music using AI.

The AI system created a song titled "One Two," which immediately should've been a red flag. Those are the opening words of "You Get What You Give" by New Radicals. The AI wasn't subtle. The opening line was literally "Every night we smash a Mercedes Benz," pulled directly from the original song. Then came "Wake up, kids / We got the dreamer's disease," and "First we run, and then we laugh 'til we cry." All. Direct. Quotes.

Athletes and coaches in the figure skating community noticed immediately. Shana Bartels, a journalist who covers competitive skating, caught it and wrote about it on her Patreon. The skating community started seething on social media.

So the duo changed their approach. They swapped out the New Radicals lyrics for new AI-generated lyrics that sounded suspiciously like Bon Jovi. Lines like "raise your hands, set the night on fire" appeared in the new version—and those lyrics appear in an actual Bon Jovi song called "Raise Your Hands." (Not even from the '90s, by the way, which made the theme violation even more awkward.)

The AI "vocalist" also sounded uncannily like Jon Bon Jovi. Deep voice. That characteristic vibrato. Everything.

Then came the Olympics. The duo skated to this second version—the Bon Jovi knockoff—which then transitioned into "Thunderstruck" by AC/DC, an actual '90s song by actual people. So their routine was half-plagiarized AI and half-legitimate music.

The most baffling part? The International Skating Union, the governing body that oversees competitive ice skating, actually approved this. The official Olympics website listed the music as "One Two by AI (of 90s style Bon Jovi)" and "Thunderstruck by AC/DC." Nobody blocked it. Nobody stopped it. It happened on the world's biggest sporting stage.

Here's the real kicker: none of this broke official Olympic rules.

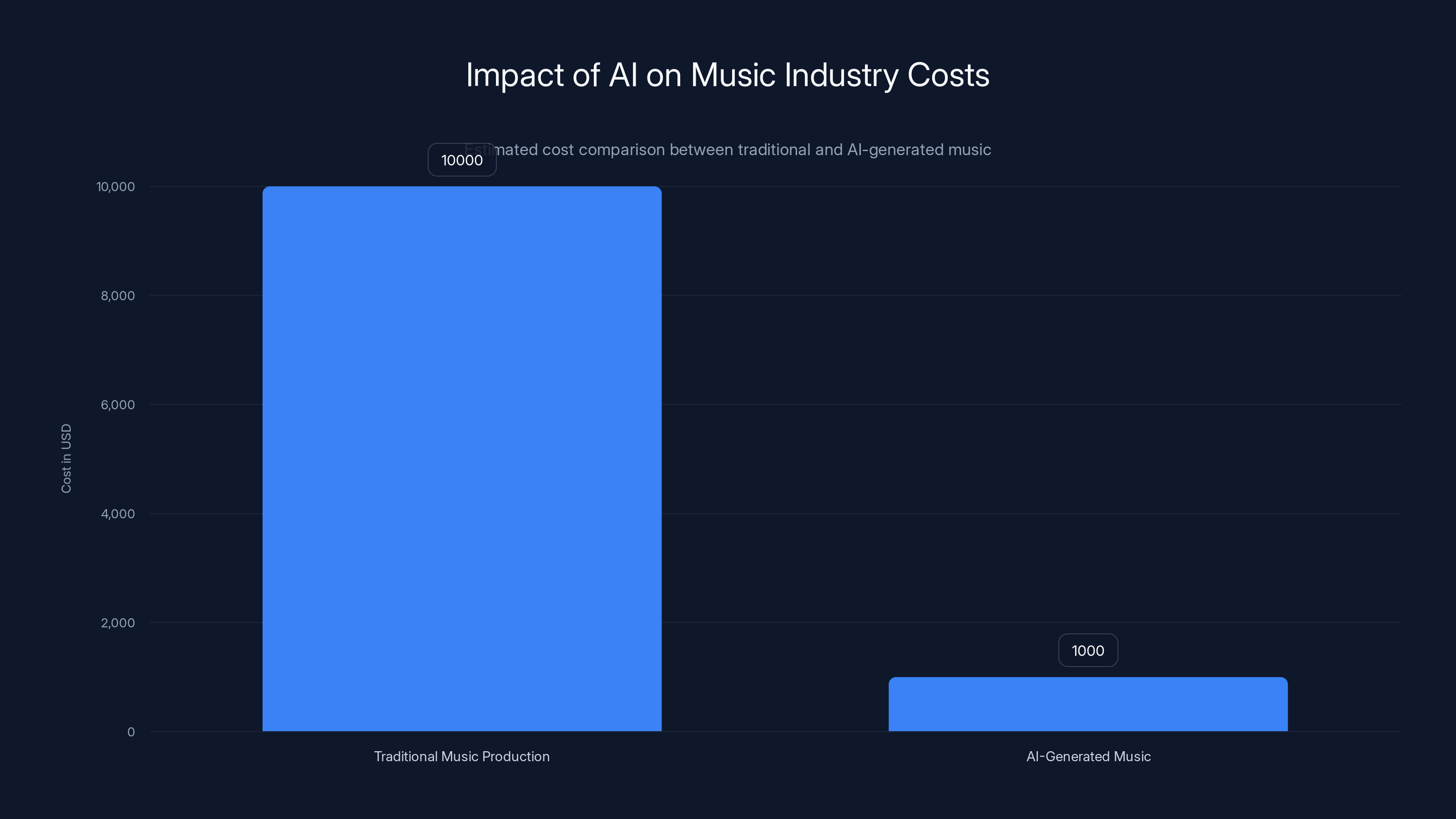

AI-generated music can be produced at a fraction of the cost of traditional music production, posing a significant economic threat to the industry. (Estimated data)

Why LLMs Plagiarize: The Technical Reality

Before you blame the dancers or the AI company, you need to understand something fundamental about how these systems actually work. This isn't a bug. It's the system doing exactly what it was designed to do.

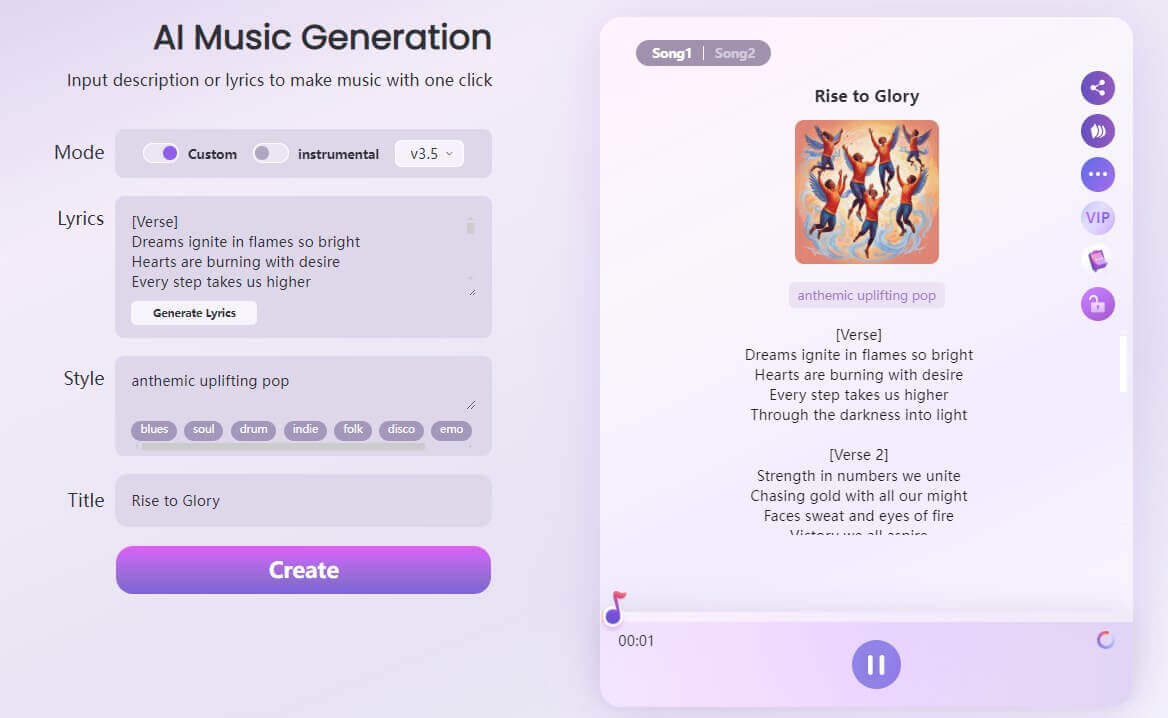

Large language models (and music-generating versions like them) are trained on massive datasets of existing content. We're talking millions upon millions of songs, all dumped into a statistical machine. The model learns patterns in this data. It learns that certain words, melodies, and chord progressions tend to appear together. It learns the "language" of Bon Jovi songs—the lyrical patterns, the melodic structures, the emotional arc.

When you prompt the system to create something "in the style of Bon Jovi," you're asking it to generate the most statistically probable text or music that matches that pattern. The system doesn't think. It doesn't create from scratch. It predicts what comes next based on probability.

So here's what happens: the system has been trained on Bon Jovi songs. Those songs contain certain lyrics and melodies. When asked to create "Bon Jovi style," the system outputs the statistically probable next words or notes. And guess what? Those are often the actual words and notes from Bon Jovi songs.

This is why the AI-generated music sounded like plagiarism. It wasn't a mistake. It was the inevitable outcome of the system doing what it was designed to do.

The math works like this:

Given a prompt like "Generate a song in the style of Bon Jovi," the model calculates:

Where each token (word, syllable, note) is the statistically most likely option given the prompt and context. When you train on millions of Bon Jovi songs, the "most likely" output often is the actual Bon Jovi content.

This is useful for some tasks. When you're generating code, predicting the next line of a Python function based on statistical probability works great—because most functions follow predictable patterns. When you're writing a technical document, the same principle helps.

But when you're creating music or poetry in a specific artist's style? You're almost guaranteed to get actual content from that artist.

The real culprit isn't the model. It's the training data.

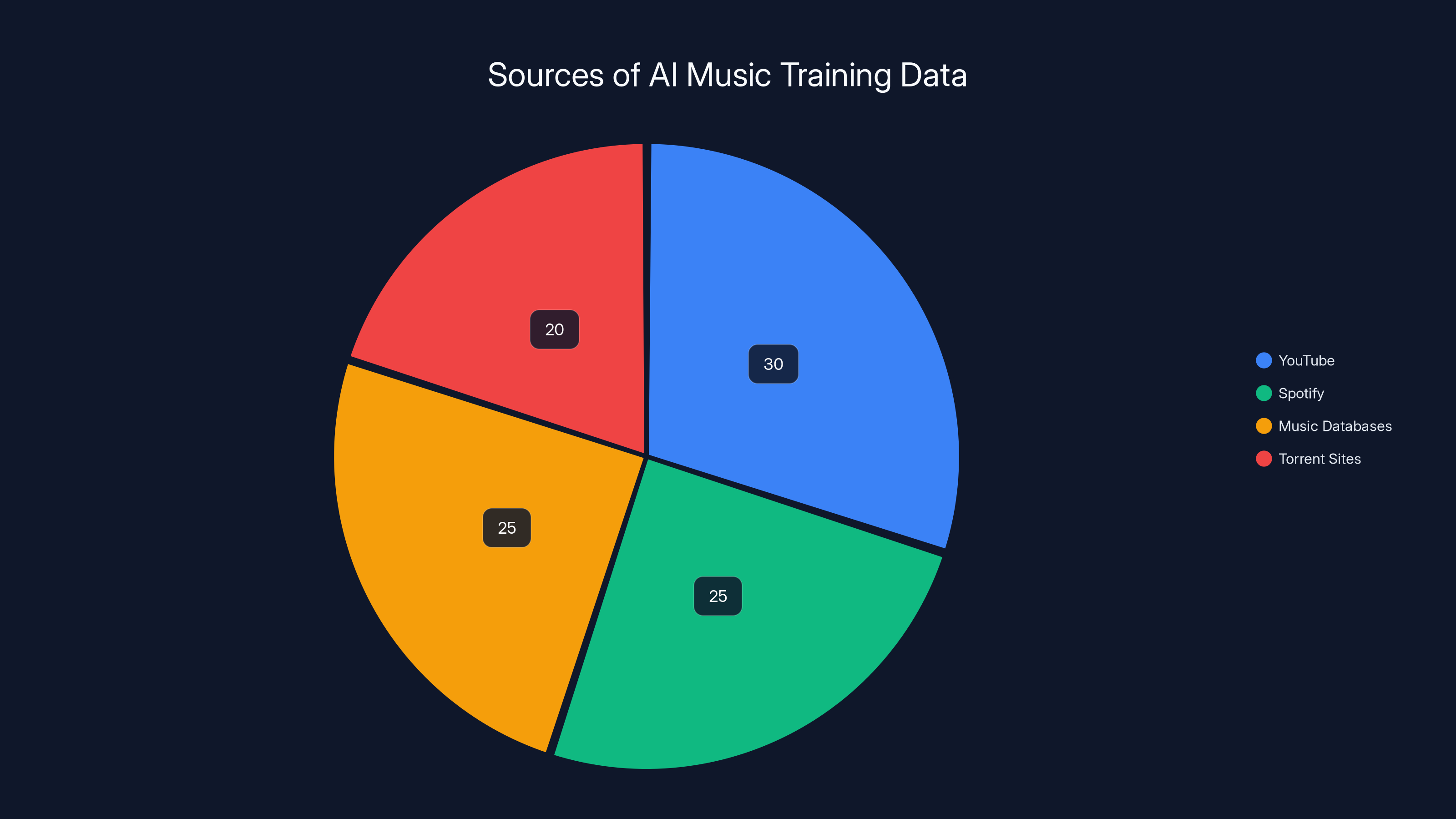

The Training Data Problem: Theft as Standard Practice

Most AI music generation platforms train their systems on massive datasets that include decades of copyrighted music, often scraped from the internet without artist permission. This isn't theoretical—it's documented.

Platforms like Suno (which powers a lot of AI music generation) were trained on music collections that likely include copyrighted material. Nobody's fully transparent about this. When you dig into terms of service, most companies gloss over the source of their training data.

Here's the process:

- Acquire data: Scrape music from various sources (YouTube, Spotify, music databases, torrent sites—it varies)

- Clean data: Format it in a way the model can process

- Train model: Feed millions of songs into a neural network until it learns patterns

- Deploy model: Release it to users who can prompt it to generate new music

- Plagiarism: Users generate "new" music that's statistically similar to training data

The problem is step one. Most of the music being scraped was never licensed for AI training. Artists didn't consent. Record labels didn't consent. But the companies doing the scraping argue they're operating in a legal gray zone.

And they kind of are. U.S. copyright law has this thing called "fair use," which allows limited copying of copyrighted material for research or transformation purposes. AI companies argue that training models on copyrighted music qualifies as fair use. Courts haven't definitively ruled on this yet, so companies keep training and scraping.

But even if training on copyrighted music is legal, the output—music that literally contains copyrighted lyrics and melodies—probably isn't legal to use or distribute.

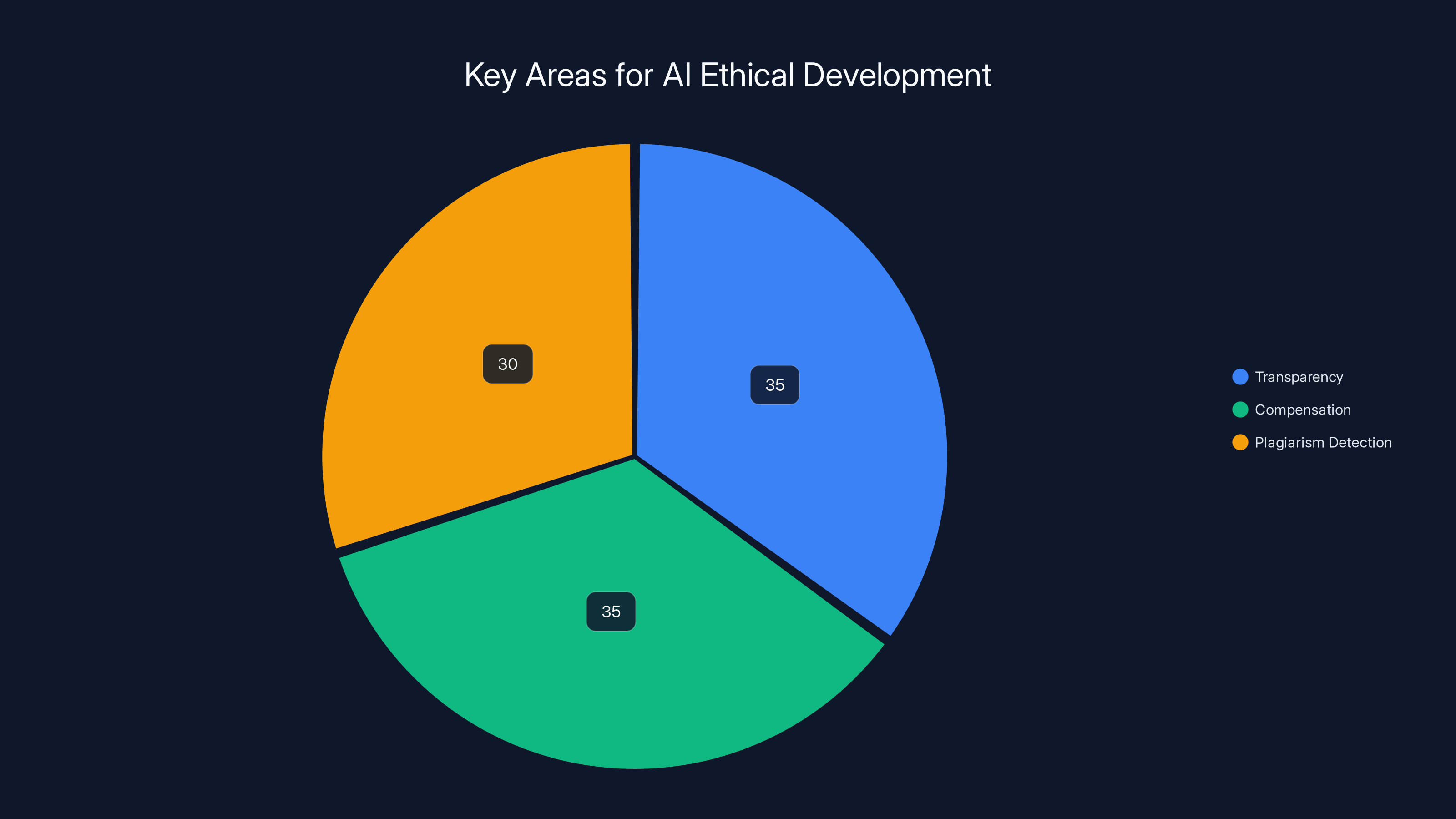

Estimated data suggests equal emphasis on transparency and compensation, with a slightly lower focus on plagiarism detection. Addressing these areas is crucial for ethical AI development.

The Olympics and Rule Grey Zones

Here's the thing that drives skating purists crazy: nothing in Olympic rules explicitly prohibits AI-generated music.

The International Skating Union has rules about music selection. Rhythms must match a specific theme. Music must be appropriate for competition. But nowhere does it say "no artificial intelligence." Technically, an athlete could perform their entire routine to music generated by an LLM, and they wouldn't be breaking any official rules.

But they'd be breaking copyright law.

The Olympics exist in this weird legal space where they have their own internal rules, but those rules don't override national and international copyright law. So while the ISU said "okay" to the music, actual copyright holders (or their estates) could theoretically claim infringement.

Will they? Probably not. New Radicals' record label isn't going to sue Olympic athletes. But they could, and that's the problem. The legal structure isn't clear.

This is the fundamental issue with AI-generated content right now: the tools can produce output that's technically legal to use (under some interpretations) but actually infringing on copyright law. The responsibility falls on the user—and most users don't even realize they're committing infringement.

Mrázková and Mrázek probably didn't know they were violating copyright. They used a tool, got output, and performed it. They might've thought "AI-generated" meant "original." It didn't.

What This Means for the Music Industry

The ice dance incident is a canary in the coal mine for the music industry. This is what's coming.

Right now, music companies are panicking. They see platforms like Suno, which can generate listenable music in seconds, and they see a future where their artists' careers might be displaced by statistical models. They're filing lawsuits. They're pushing for legislation. They're demanding that AI companies pay licensing fees.

But there's a deeper problem: nobody knows how to fix this.

You can't un-train a model. Once music is in the training data, it's encoded into the weights and parameters. You can't remove it. You can build new models with different training data, but that's expensive and time-consuming.

You could require AI companies to pay licensing fees for training data, but then the cost of building these systems skyrockets, and only big companies can afford them. You could establish copyright protections for AI output, but then every generated song becomes a potential legal liability.

Or you could do nothing and watch the industry transform. Some musicians are already experimenting with AI. Telisha Jones used Suno to generate music for her poetry, and she got a $3 million record deal. Not because the music was better than human-composed music, but because it was cheap, fast, and good enough.

That's the real threat: not that AI will be better than human musicians, but that it'll be "good enough" at a fraction of the cost.

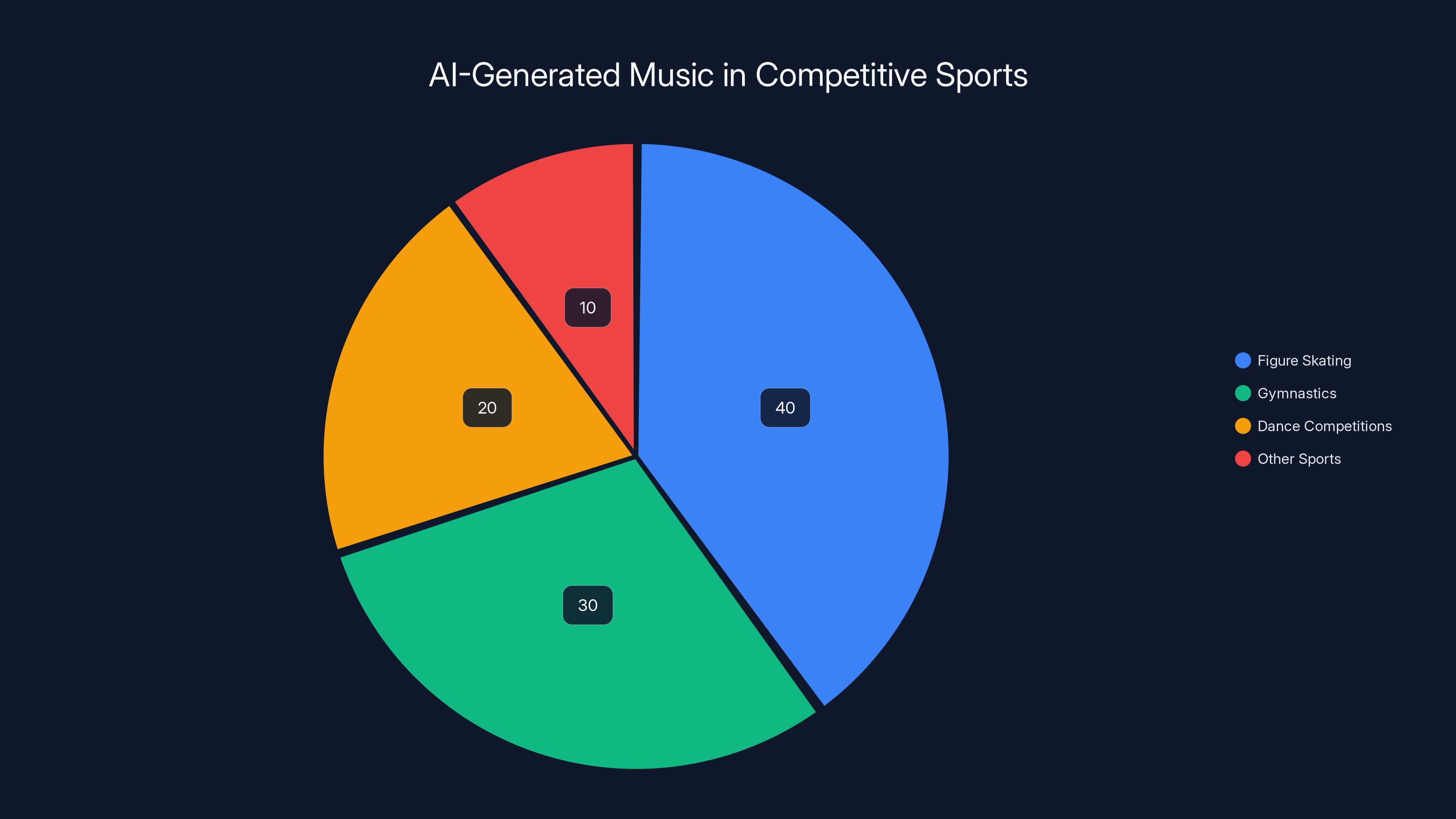

Estimated data shows figure skating as the primary user of AI-generated music in competitive sports, followed by gymnastics and dance competitions.

The Plagiarism Pattern: It's Not Random

Here's what bothers me most about the ice dance situation: it's not an isolated incident. This is a pattern.

The duo didn't accidentally create two different songs that happened to plagiarize two different artists. They deliberately used AI music generation, got plagiarized output, and then tried again with different parameters. Same problem, different artist.

This suggests a fundamental misunderstanding about what these tools actually do. They're not magic creativity machines. They're statistical models that reproduce training data in statistically likely combinations.

When you ask for "'90s style music," you're asking for the most statistically probable sequence of notes and lyrics that appeared in '90s songs in the training data. If that includes actual Bon Jovi or New Radicals, the model will output that.

It's not a bug. It's not a mistake. It's the system working as designed.

The real question is: why are we surprised? We built systems trained on copyrighted material and then acted shocked when they output copyrighted material. That's like training a model on thousands of conversations and then being surprised when it repeats conversations.

The mathematics of this are straightforward. If a model is trained on 500,000 songs, and 1,000 of them are Bon Jovi, then roughly 0.2% of the statistical patterns in the training data are Bon Jovi patterns. When you ask the model to generate "Bon Jovi style," it weights those patterns heavily. The output will be statistically similar to Bon Jovi songs, which means it will often be parts of actual Bon Jovi songs.

This isn't a problem with the model. It's a problem with how we're building and deploying these systems.

The Creativity Conversation Nobody's Having

But here's where it gets really interesting, and where the ice dance incident becomes a mirror for a much larger cultural question.

The Olympics are supposed to be about human excellence. About athletes pushing their bodies and minds to impossible limits. Figure skating, in particular, is supposed to showcase artistry. Skaters work with choreographers for months. They interpret music emotionally. They create something that's uniquely theirs.

Now we're at a point where an Olympic routine can use music that was generated by a machine predicting statistically probable sounds. There's no artist behind it. No one understood the emotion or vision. A system processed 500,000 songs and outputted the most likely sequence.

And we're calling that acceptable at the Olympics.

I'm not here to say AI music is evil or that technology is ruining sport. That's simplistic. But I am saying that there's something worth questioning about a world where athletes on the biggest stage can use AI-generated content without even realizing it's plagiarized.

The figure skating community got this right when they voiced concerns. This isn't about being technophobic. It's about asking: what are we actually celebrating if the music itself is machine-generated and plagiarized?

Sports have rules partly to maintain competitive integrity, but also to preserve what makes the sport meaningful. If you allow synthetic, plagiarized music, you're changing what ice dance actually is. You're saying that the music component doesn't matter as much as we thought. You're saying technical skating ability is what counts, and the artistic expression is optional.

Maybe that's fine. Maybe figure skating should be judged purely on technique. But that's a decision the sport should make deliberately, not through neglect.

Estimated data suggests that AI music platforms predominantly source training data from YouTube and Spotify, with significant portions also coming from music databases and torrent sites. Estimated data.

What Happened to Originality in AI?

There's a philosophical question lurking under all of this: can AI actually be original?

By definition, LLMs work by predicting patterns from training data. They don't have experiences. They don't have emotions. They don't have perspectives. They can't want something the way a human artist wants something.

What they can do is remix. They can recombine elements from training data in novel arrangements. Sometimes those arrangements are creative. Sometimes they're just new statistical combinations of old patterns.

But when those arrangements include actual copyrighted material, is it still remix? Or is it plagiarism with extra steps?

The ice dance example is plagiarism, full stop. But there's a spectrum. Some AI-generated music sounds completely original because the arrangement of statistical patterns doesn't happen to match existing copyrighted material. Other AI-generated music is almost identical to existing work.

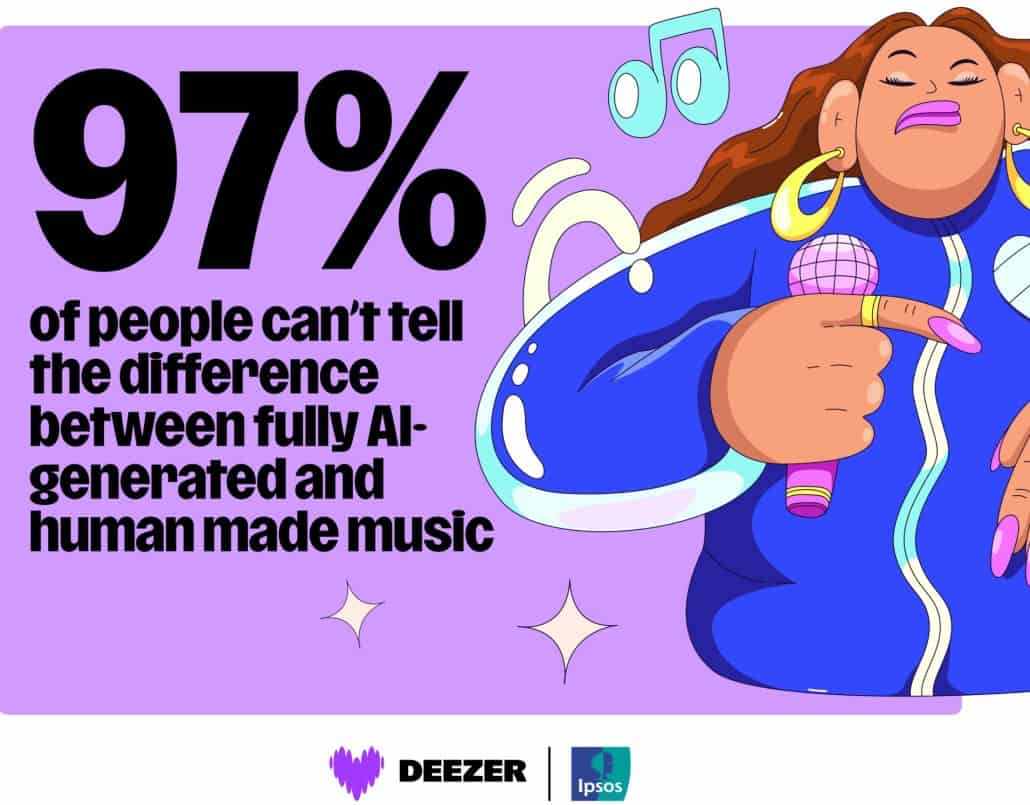

But here's the uncomfortable truth: we don't know where the line is. We can't easily tell whether a given piece of AI music infringes copyright or not. There's no plagiarism detector that works for music the way it does for text (and text plagiarism detection is already imperfect).

So we've created a system where artists can generate music, distribute it, build careers on it, and never know if they're committing infringement.

The Economics of AI Music

Let's talk about why this happened in the first place. Why would Olympic athletes use AI music?

The answer is probably simpler than you think: cost and convenience.

Licensing music for performance is expensive. You need permission from the original copyright holders. You need to pay fees. Depending on the song and how you're using it, you might need to pay every time you perform it publicly. For elite athletes competing at multiple events throughout a season, licensing costs add up.

AI music generation? You pay a subscription fee (often $10-20 per month) and generate as much music as you want. No licensing. No permission. No fees per performance.

It's the economics of convenience. Even if you know the AI might plagiarize, it's so much cheaper and easier than going through proper licensing channels that you might take the risk.

This is happening across industries. Smaller companies are using AI to generate marketing copy, blog posts, images, and videos because hiring humans is expensive. Some of that generated content probably infringes copyright. But enforcement is weak, and the economic incentive to just do it is strong.

The ice dancers might've genuinely not realized they were committing plagiarism. They might've thought "AI-generated" meant "original and safe to use." That's a reasonable assumption for a non-specialist. It's also wrong, but reasonable.

The timeline illustrates the escalation of the music selection controversy, peaking during the Olympics in 2026. Estimated data based on narrative.

Legal Liability: Who Actually Gets Sued?

So if the music is plagiarized, who's responsible?

Technically, it could be:

- The athletes: They performed the music publicly and might be liable for copyright infringement

- The AI company: They created the tool and the output

- The event organizer: The Olympics hosted the performance

- The coach/choreographer: They selected the music for the routine

In practice? Probably nobody. Copyright enforcement in this space is still developing. But the potential for liability is there, and it's unclear.

This is why music companies are pushing for legislation. They want clear rules. They want to establish that AI companies are liable for their training data choices and output. They want damages when copyrighted material is infringed.

Right now, there's just ambiguity. And ambiguity means continued risk.

The ice dancers might have faced no legal consequence. But someone else might. And when that happens, it'll set a precedent that changes how AI music is created and used.

The Future of AI Music in Sports

What happens next? Probably nothing in the immediate term. The ice dancers completed their Olympic debut. The controversy fades. Life moves on.

But the structural problem remains. As AI tools get cheaper and easier to use, more athletes will experiment with them. More plagiarism will happen. Eventually, a major artist or label will sue to establish precedent. And then the rules will change.

My guess is that we'll see three developments:

First, stronger copyright enforcement. AI companies will either train models on licensed music only, or they'll face lawsuits that force them to. The cost of generating music will go up. The plagiarism risk will go down.

Second, clearer rules from sporting bodies. The Olympics and other sports organizations will explicitly address AI-generated content. They might allow it with restrictions. They might ban it entirely. But they'll stop ignoring it.

Third, better plagiarism detection. Tools will emerge that can identify whether AI-generated music contains copyrighted material. Athletes, platforms, and rights holders will use these tools to reduce liability.

But these changes take time. In the interim, we're in a weird zone where AI music is technically possible, legally ambiguous, and probably violating copyright law in ways we don't fully understand.

What This Means for Other Creative Industries

The ice dance incident isn't just about music. It's about all creative work.

Imagine a designer using AI to generate images for a marketing campaign. Imagine a writer using AI to draft a screenplay. Imagine a developer using AI to write code. All of these scenarios have the same plagiarism risk that the ice dancers faced.

AI systems are being trained on copyrighted creative work without permission. When they generate output, that output sometimes contains copyrighted elements. When people use that output without knowing it's plagiarized, they're committing infringement.

This is happening at massive scale across every creative industry. Journalists are using AI to draft articles. Marketing agencies are using AI to generate ad copy. Game developers are using AI to create sprites and textures.

Most of them don't realize they're walking into legal liability.

The ice dance story is just the Olympics-sized version of a problem that's happening millions of times per day in less visible ways.

The Conversation About Creativity

But underneath all the legal and technical issues is a deeper conversation about what creativity actually is.

If a machine predicts statistically probable sequences based on patterns in training data, is that creative? Most people would say no. Creativity requires intention, perspective, emotional depth. A statistical model can't have those things.

But here's where it gets uncomfortable: machine-generated output sometimes feels creative. Sometimes it's genuinely surprising and beautiful. Sometimes it makes people cry or think differently about something.

If the output is indistinguishable from human creativity, does the source matter? Is creativity defined by the process or by the result?

This is a question philosophers, artists, and lawyers are going to grapple with for decades. The ice dance incident is just one data point in a much larger conversation about what it means to create something in a world where machines can generate content.

I don't have a definitive answer. But I know that dismissing AI creativity entirely is probably too simple, and celebrating it uncritically is definitely too simple.

The truth is more nuanced. Some AI output is genuinely novel and creative. Some is plagiarism disguised as novelty. And we don't have good tools yet to tell the difference.

The Real Issue: Consent

At the core of this whole situation is a consent problem.

Artists never consented to have their work used in AI training datasets. They never agreed that their music, their writing, their art would be fed into statistical models to extract patterns. If someone had asked "Can we train a machine learning model on your creative work?" most would've said no. Or asked for payment.

But nobody asked. Companies just scraped the internet and trained models. The artists found out after the fact, when AI systems started generating output that sounded suspiciously like their work.

This is a violation of creative autonomy. It's not about money, exactly, though that matters. It's about artists not having control over how their work is used. It's about their creative legacy being fed into machines without their knowledge.

Some artists are pushing back. They're filing lawsuits. They're demanding that AI companies license training data properly. They're asking for compensation when their work is used to train models.

They're right to push back. But the genie is out of the bottle. Models have already been trained. You can't undo that.

The best we can do going forward is establish clear consent frameworks. If you want to use an artist's work in a training dataset, you need to ask permission and offer compensation. That will make AI development more expensive. It might slow innovation. But it's the right thing to do.

The ice dancers probably didn't think about this. They just needed music for their routine. They didn't think about whether the artists behind the training data had consented. They didn't think about whether they were perpetuating a violation of creative autonomy.

But that lack of thought doesn't make it less of a violation. It just makes it invisible.

Where We Go From Here

So what's the path forward?

I think we need three things:

First, transparency. AI companies should be completely transparent about their training data. What music did you scrape? From where? Did you get permission? If you can't answer these questions, you shouldn't be training models.

Second, compensation. If you're going to use creative work to train AI, you should pay the artists. This increases costs, but it's the ethical choice. And it's probably legally required eventually anyway.

Third, better plagiarism detection. We need tools that can identify whether AI-generated content contains copyrighted material. These tools should be freely available to anyone, not just well-funded companies.

The ice dance incident is a symptom of a system that's broken. It's not the athletes' fault. It's not even necessarily the AI company's fault, though they deserve some blame for not being more transparent about their training data.

It's a structural problem. We've built tools that can generate plagiarized content without anyone realizing it's plagiarized. We've created incentives for people to use those tools because they're cheap and easy. We've failed to establish clear legal and ethical frameworks around AI-generated content.

The Olympics are big. They're visible. So when plagiarized music shows up there, everyone notices. But this is happening in marketing agencies, design studios, development teams, and publishing houses every single day. The ice dance story is just the visible tip of a massive iceberg.

Until we address the underlying structural issues, we're going to keep seeing versions of this story. Athletes, creators, and companies will keep using AI tools, getting plagiarized output, and sometimes getting caught. Sometimes they'll face legal consequences. Usually, they won't.

But the artists whose work was stolen? They'll never see compensation. They'll never be asked permission. They'll just watch as their creative legacy gets processed into training data and transformed into output that sounds like their work but isn't.

That's the real story behind the ice dancers. It's not about them. It's about a system that's broken and needs to be fixed.

FAQ

What is AI-generated music in competitive sports?

AI-generated music in competitive sports refers to compositions created by artificial intelligence systems, typically large language models or music generation platforms, that are used in athletic performances like figure skating. These systems are trained on existing music libraries and generate new compositions by predicting statistically probable sequences of notes and lyrics based on patterns in their training data.

How do music-generating AI systems work?

Music AI systems use neural networks trained on massive datasets of existing songs. When you provide a prompt like "create a song in the style of Bon Jovi," the system calculates the statistically most probable next note or lyric based on patterns in its training data. This mathematical approach means the output often reproduces elements from the training data, including copyrighted material, because the most probable next sequence is frequently an actual sequence from a song the system learned from.

Why did the Olympic ice dancers' AI music plagiarize existing songs?

The plagiarism occurred because music AI systems are trained on copyrighted material (often scraped from the internet without artist permission) and generate output by predicting the statistically probable next element. When prompted to create "Bon Jovi style" music, the model outputs sequences that match actual Bon Jovi songs because those patterns are in the training data. This isn't a glitch—it's the predictable outcome of how these systems work.

Is using AI-generated music legal for performance?

AI-generated music exists in a legal gray zone. While generating music using AI isn't prohibited by law, if that music contains copyrighted material from artists or songs in the AI system's training data, the user may be committing copyright infringement by performing or distributing it. Most AI music platforms don't warranty that their output is free from copyright claims, placing the liability on users.

What do sporting organizations say about AI music in competition?

Currently, most sporting organizations including the International Skating Union don't have explicit rules prohibiting AI-generated music. This creates a legal ambiguity where athletes can use AI music without breaking official competition rules while potentially violating copyright law. Sporting bodies are beginning to address this gap as AI use becomes more common.

How can athletes and creators avoid plagiarism when using AI tools?

The safest approach is to avoid AI-generated content for public performance unless you can verify it doesn't infringe copyright. If you use AI tools, ask the platform directly about their training data sources, request guarantees about copyright compliance, and consider having generated content reviewed by a copyright attorney before public use. Many AI platforms are unwilling to provide these guarantees because they can't verify their output is original.

What's the difference between AI music and traditional composition?

Traditional composition involves human creativity, intentionality, and emotional expression. The composer makes deliberate choices about melody, harmony, and structure based on vision and skill. AI music generation produces statistically probable sequences without intention or emotion. However, some AI-generated music can sound creative and original simply because statistical arrangement happens to produce novel combinations that weren't in the training data—even though the underlying process is fundamentally different from human composition.

Will this problem get worse as AI music tools become more popular?

Yes. As AI music generation becomes cheaper and easier to access, more athletes, creators, and companies will experiment with these tools. This will likely lead to more plagiarism incidents, higher legal liability, and eventually stricter rules from both sporting organizations and legal systems. The ice dance incident is probably just the first visible instance of a larger trend.

What happens legally if someone performs plagiarized AI music publicly?

Potentially, any of several parties could face copyright infringement liability: the performer, the AI company, the event organizer, or the choreographer who selected the music. In practice, enforcement is still developing. However, copyright holders can sue for infringement and seek damages. The recent lawsuits filed against AI music companies suggest that courts will eventually establish clearer liability frameworks.

Can we build AI music systems that don't plagiarize?

Yes, but it would be more expensive and time-consuming. AI companies would need to train models exclusively on music they have permission to use, properly license training data from artists and labels, or develop new approaches to music generation that don't rely on learning patterns from existing copyrighted work. The current approach is cheaper, which is why most platforms still operate the way they do.

The Bottom Line

The Czech ice dancers at the Olympics probably didn't set out to start a controversy about AI and copyright. They just wanted music for their routine. They used a tool that seemed convenient and affordable. The tool generated output that happened to plagiarize existing songs. They performed anyway, and nobody stopped them until millions of people were watching.

It's an easy story to dismiss as "a few athletes made a mistake." But it's really a story about a broken system.

We've built AI tools that can generate plagiarized content without users realizing it's plagiarized. We've created economic incentives for people to use those tools because they're cheap and easy. We've failed to establish clear legal and ethical frameworks around AI-generated creative work. And we've trained these systems on copyrighted material without asking artists for permission.

The ice dance incident is just the Olympics-scale version of something that's happening thousands of times every day in less visible ways. Marketers are using plagiarized AI copy. Designers are using plagiarized AI images. Developers are using plagiarized AI code.

Most of the time, nobody notices. The plagiarism is invisible, the artists who were violated never know, and the people using the tools never realize what they've done.

Sometimes, though, it happens at the Olympics. And then everyone sees it.

The real question isn't whether the ice dancers did something wrong. They probably did, though unintentionally. The real question is: how do we build a system where this can't happen? How do we ensure that AI tools are trained responsibly, that artists are compensated and consulted, and that people using these tools understand the risks?

That's a much harder problem to solve than scolding a couple of Olympic athletes. But it's the problem we actually need to address.

Key Takeaways

- Czech Olympic ice dancers used AI-generated music that plagiarized actual Bon Jovi and New Radicals songs, not through malice but through the predictable mechanics of how LLMs work

- LLMs generate plagiarism because they predict statistically probable sequences from training data that includes copyrighted material scraped without artist consent

- Olympic rules don't prohibit AI music, but copyright law does—creating a legal gray zone where athletes can break rules unknowingly

- The real problem is training data: AI companies train on millions of copyrighted songs without licensing or artist permission

- This plagiarism pattern reveals a fundamental consent violation where artists never agreed to have their work processed into AI systems

- Economic incentives drive plagiarism: AI music costs $10-20/month vs. hundreds for proper licensing, encouraging risky choices

- This incident signals a coming transformation of the music and creative industries where cost and convenience outweigh originality concerns

- Future solutions will likely include stricter copyright enforcement, clearer sporting organization rules, and plagiarism detection tools

Related Articles

- Quadruple Axel Physics: How Ilia Malinin Defies Gravity [2025]

- Why AI-Generated Super Bowl Ads Failed Spectacularly [2026]

- AI and Satellites Replace Nuclear Treaties: What's at Stake [2025]

- AI Recreation of Lost Cinema: The Magnificent Ambersons Debate [2025]

- Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters [2025]

- How to Watch the Olympics: The Complete Streaming Guide [2025]

![AI-Generated Music at Olympics: When AI Plagiarism Meets Elite Sport [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-generated-music-at-olympics-when-ai-plagiarism-meets-elit/image-1-1770764775569.jpg)