Introduction: A Moment of Cosmic Beauty in Turbulent Times

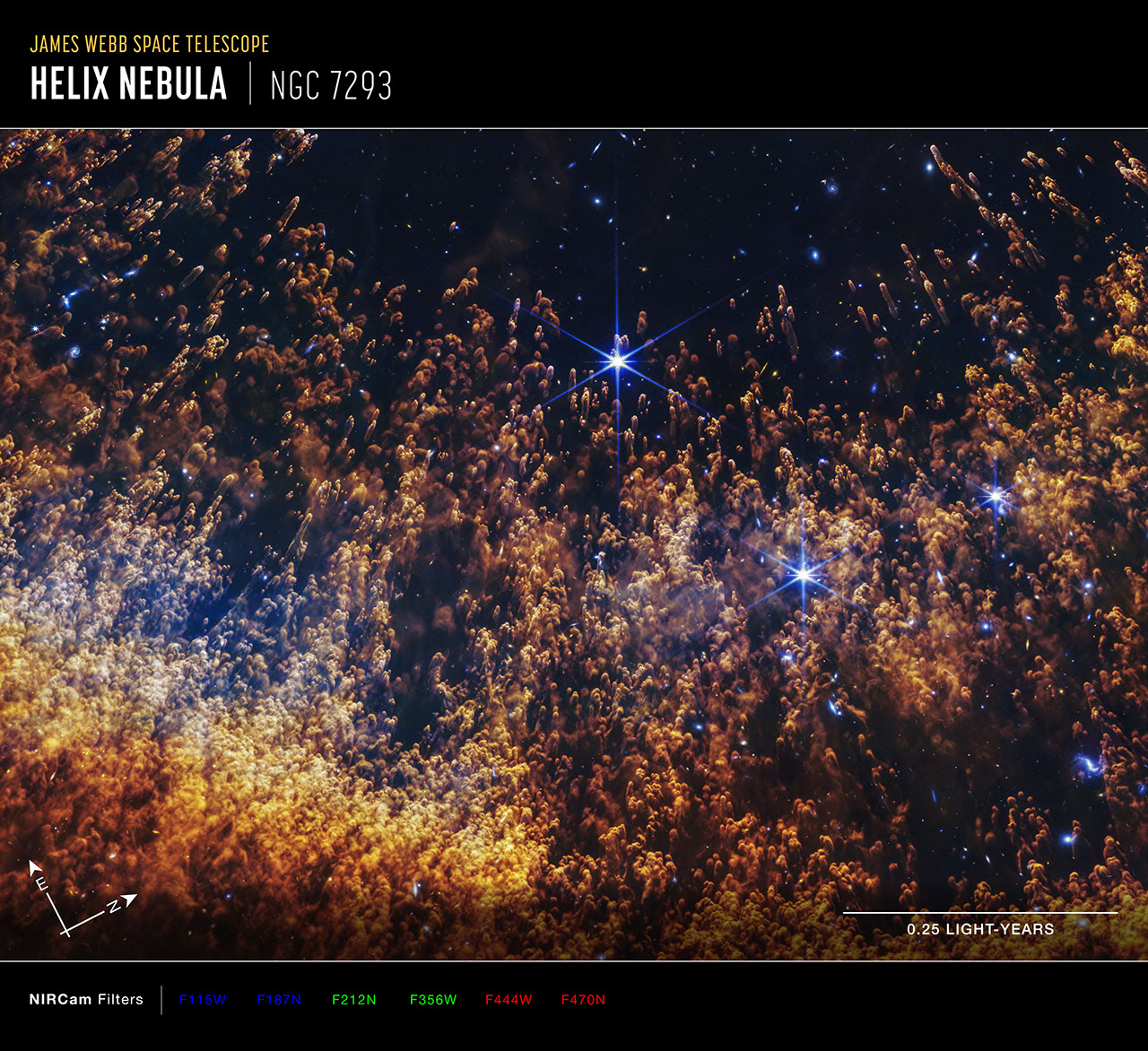

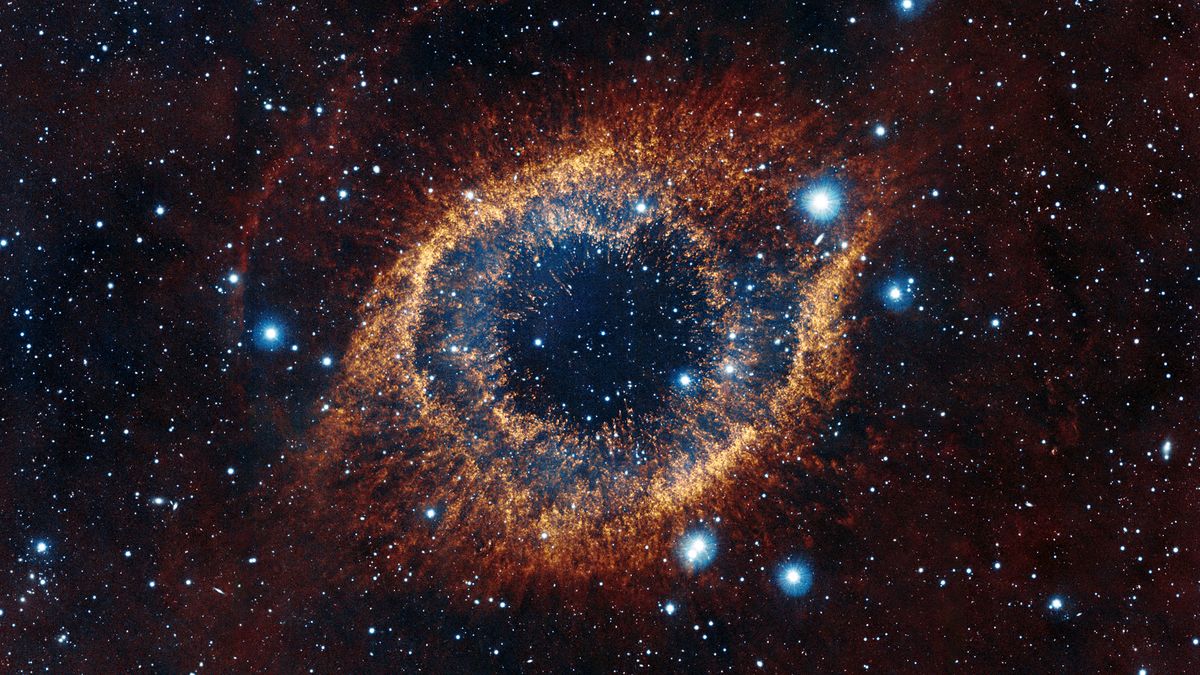

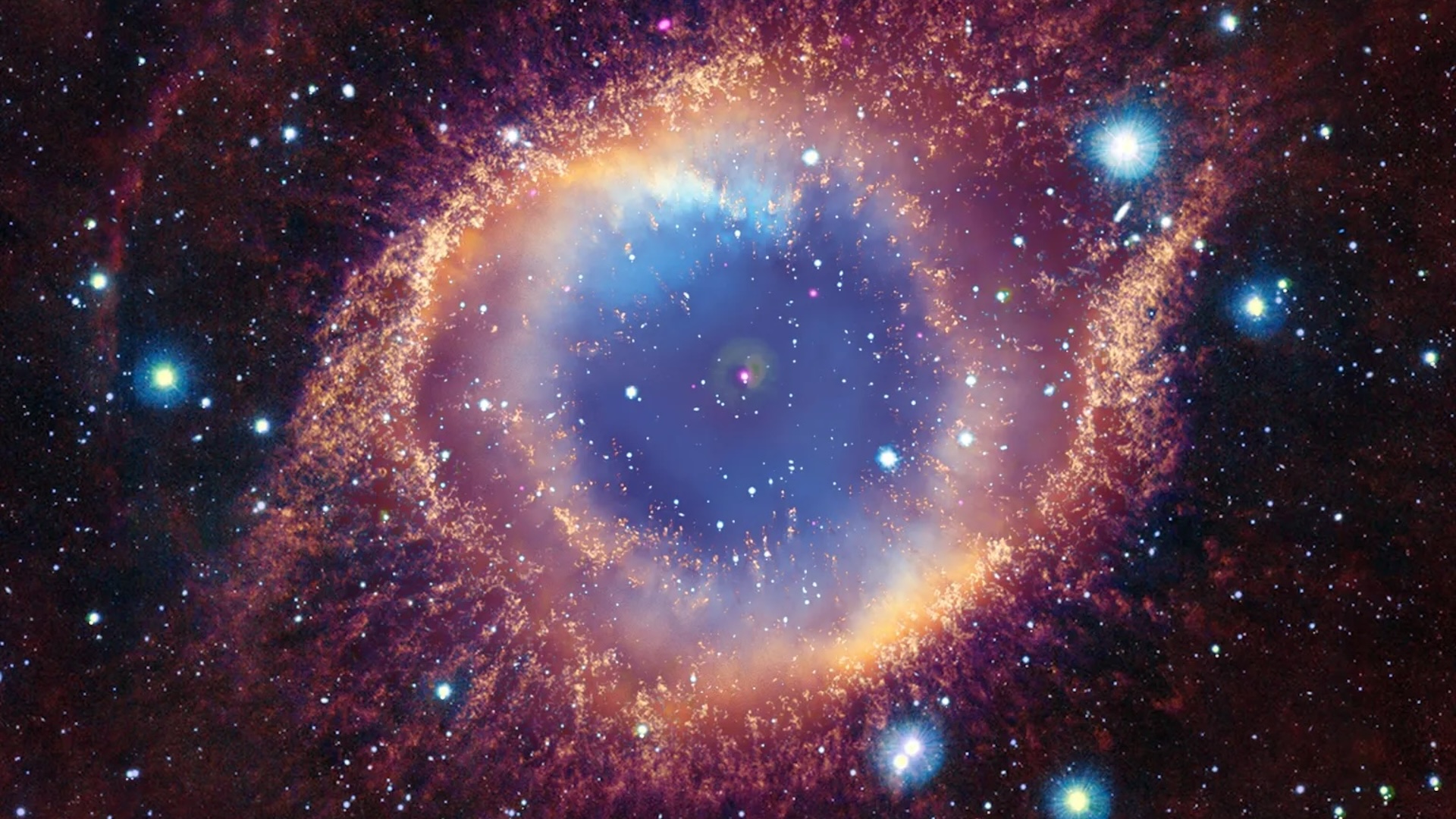

There's something almost therapeutic about looking up at the stars when everything down here feels overwhelming. And right now, with global challenges mounting by the day, taking a moment to appreciate the universe's grandeur feels less like escapism and more like survival. The James Webb Space Telescope, humanity's most sophisticated eye on the cosmos, just handed us exactly what we need: a breathtaking new image of the Helix Nebula that's so detailed, so intricate, it makes you forget about everything else for a moment.

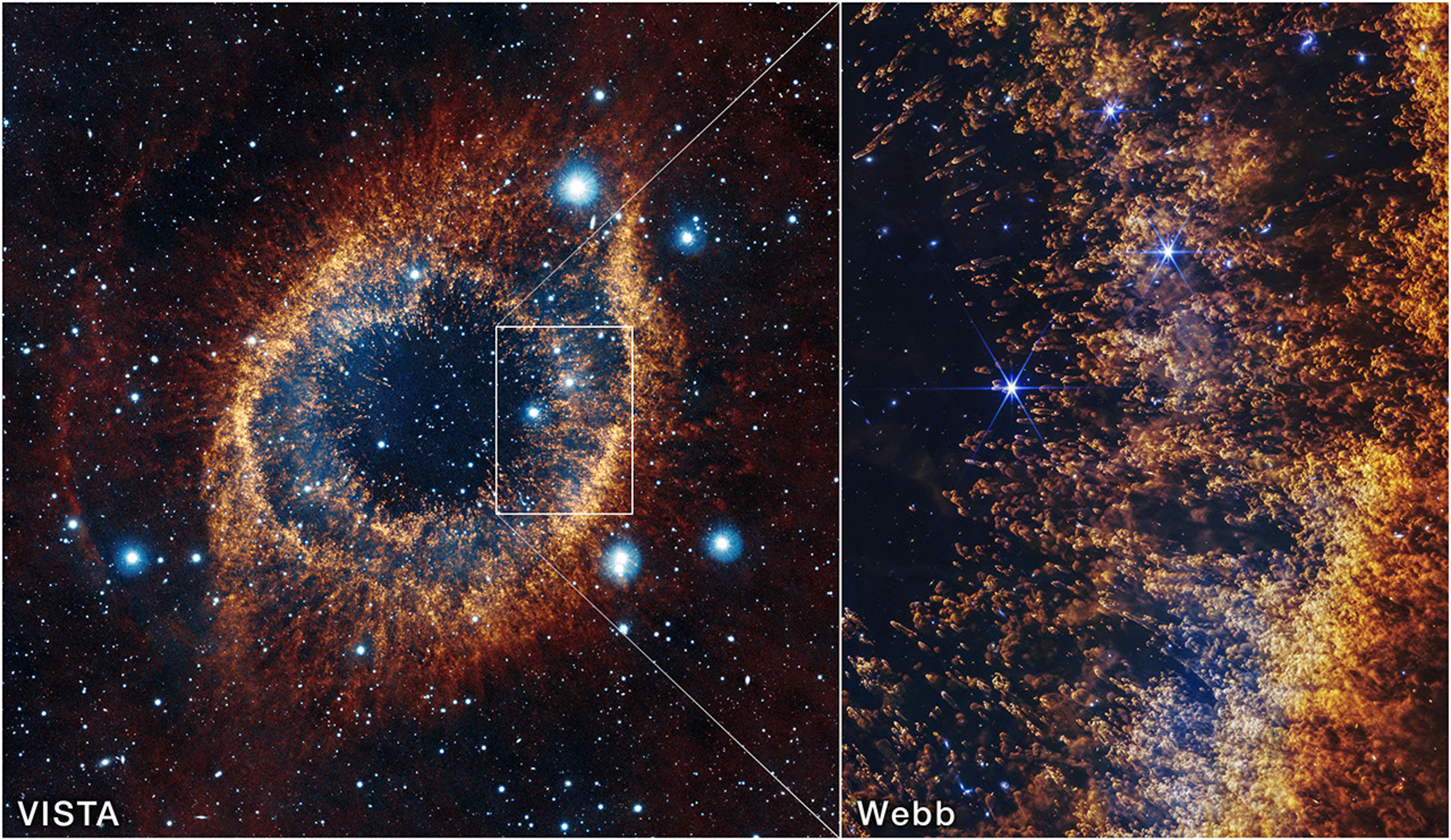

This isn't just another pretty space picture. What we're looking at is something profound, a dying star's final act caught in unprecedented detail. The image reveals what astronomers call cometary knots—pillar-like structures that resemble comets but are actually dense clouds of gas and dust being sculpted by the winds of a dying star. For the first time, we're seeing these delicate structures with clarity that was simply impossible before Webb came online.

The Helix Nebula sits about 655 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius, making it one of Earth's closest planetary nebulae. That "close" is still incomprehensibly far—light from that nebula left its source when the American territories were still very much frontier land. Yet here we are, able to peer into the details of stellar death happening at such a distance that it challenges our grasp of scale.

What makes this image particularly fascinating isn't just the beauty, though that's certainly there. It's what the image tells us about how stars die, how the universe recycles itself, and how matter that once formed a star might someday seed the birth of planets, moons, and perhaps even life. This is the cosmic circle of life in action, and Webb just gave us the best seat in the house.

TL; DR

- Webb's New Image: The James Webb Space Telescope captured the most detailed view yet of the Helix Nebula's cometary knots, revealing intricate structures never before visible.

- Distance and Scale: Located 655 light-years away in Aquarius, the Helix Nebula is one of the closest planetary nebulae to Earth.

- The Science: The image shows a dying star shedding its outer layers, creating structures that provide raw material for new star and planet formation.

- Temperature Mapping: Different colors in the image represent distinct temperature zones, from hot ultraviolet-energized gas to cool dust-forming regions.

- Why It Matters: This level of detail helps astronomers understand stellar evolution, mass loss, and the life cycles that shape our galaxy.

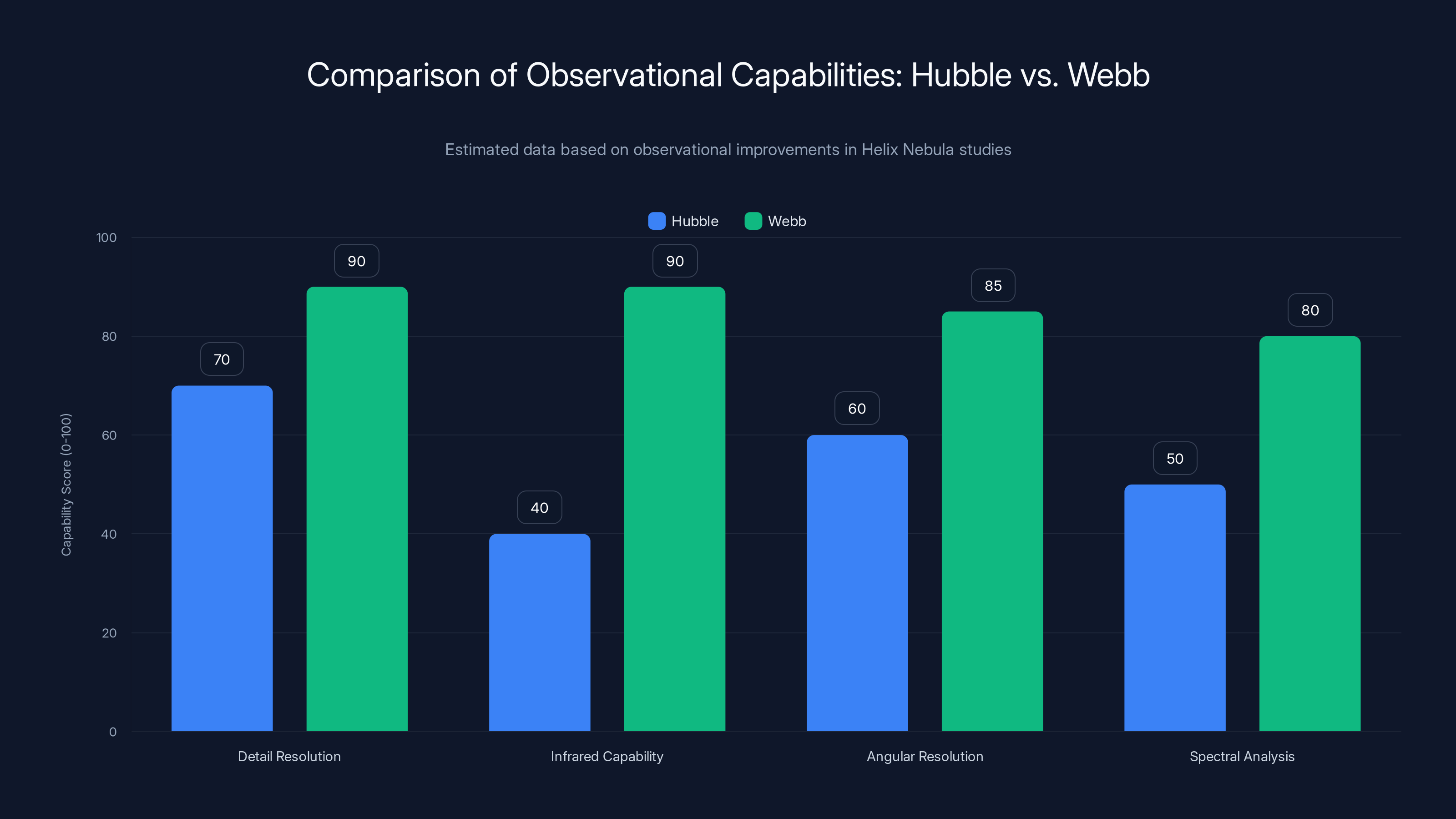

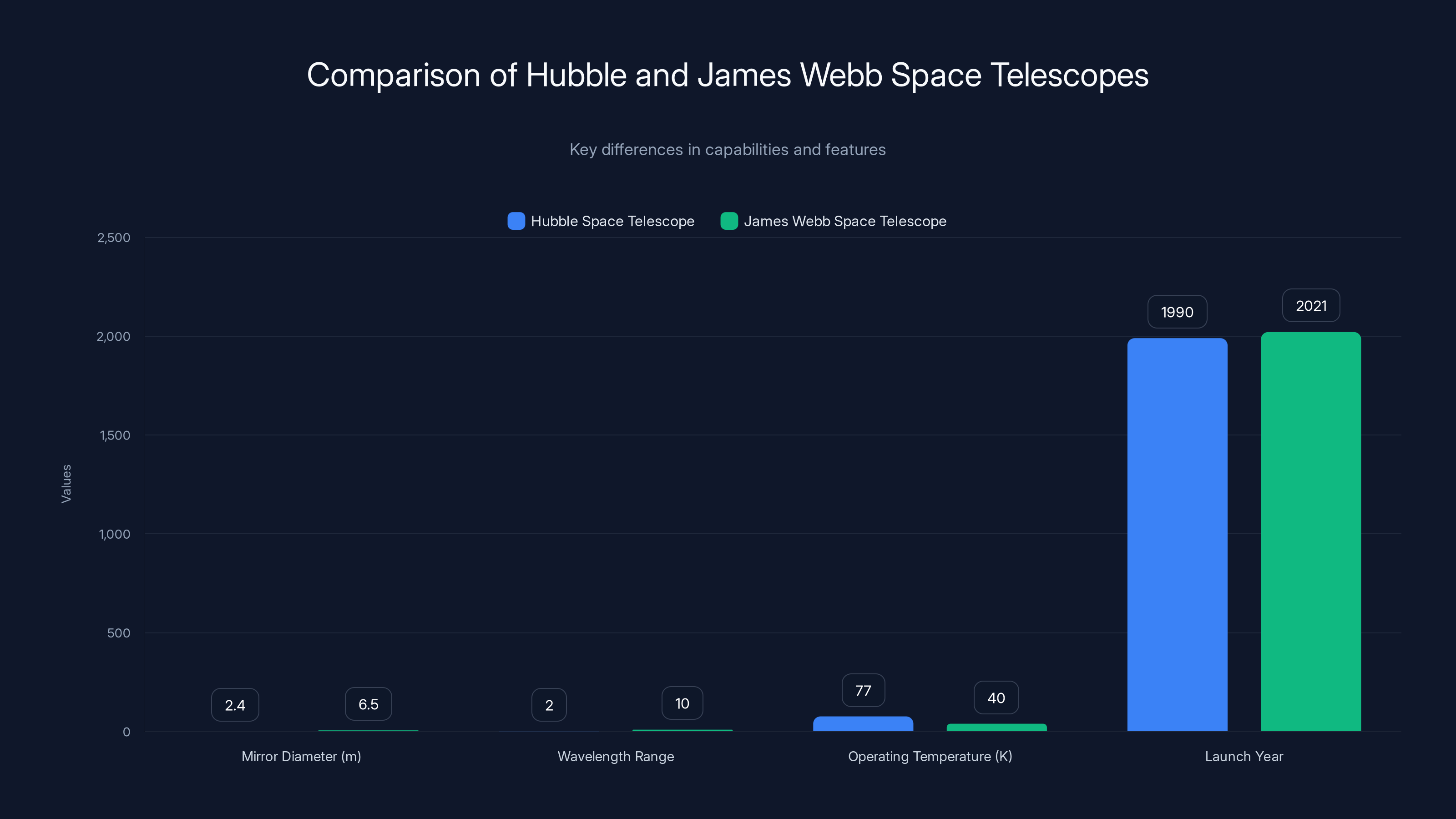

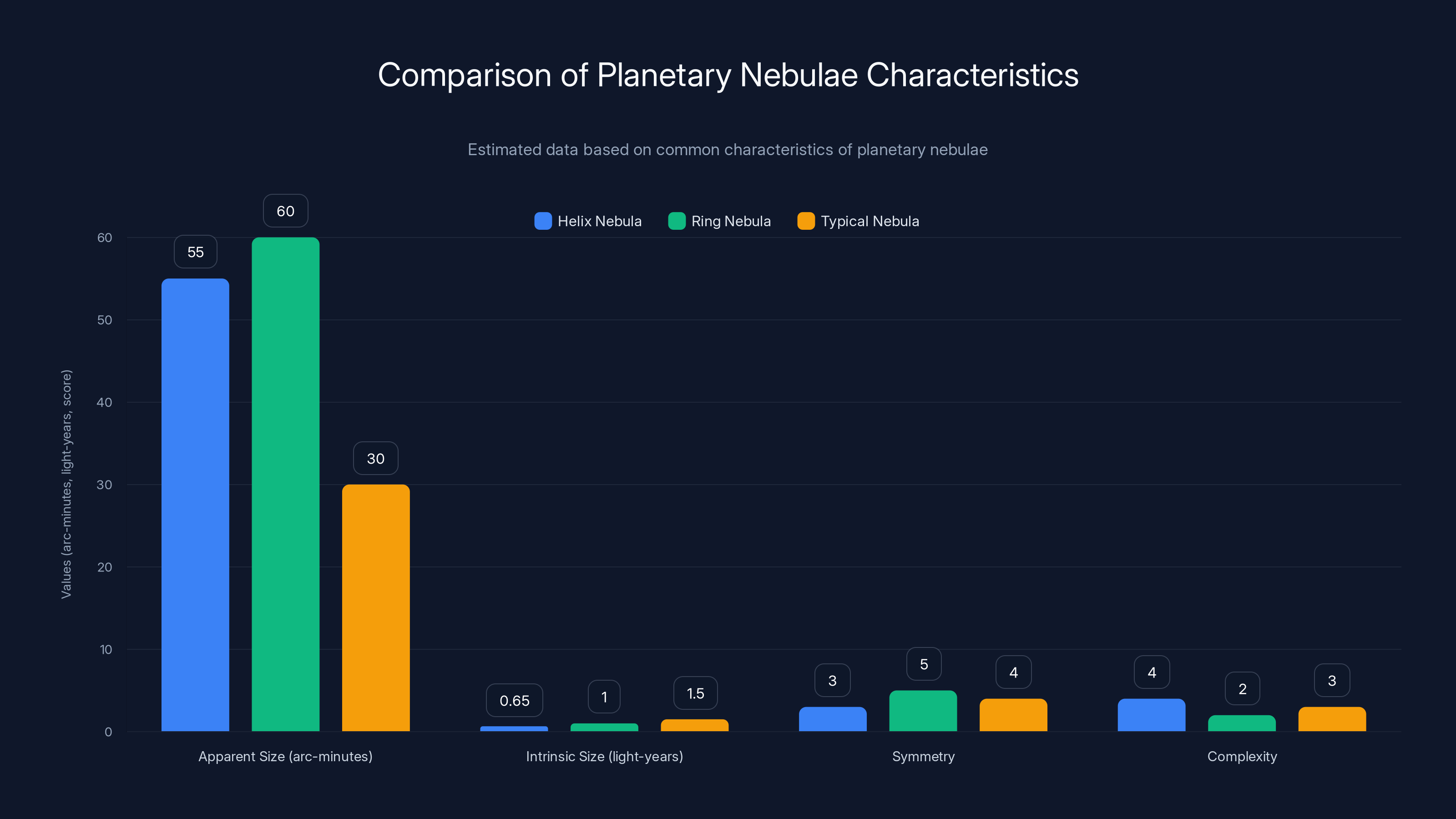

Webb significantly enhances observational capabilities over Hubble, particularly in infrared and angular resolution, allowing for more detailed studies of structures like the Helix Nebula. Estimated data.

Understanding Planetary Nebulae: Stellar Death Made Visible

Before we dive into what makes this particular Webb observation so special, let's establish what we're actually looking at. Planetary nebulae are often misunderstood by casual observers. The name itself is misleading—they have nothing to do with planets, despite what the 18th-century astronomers who named them thought.

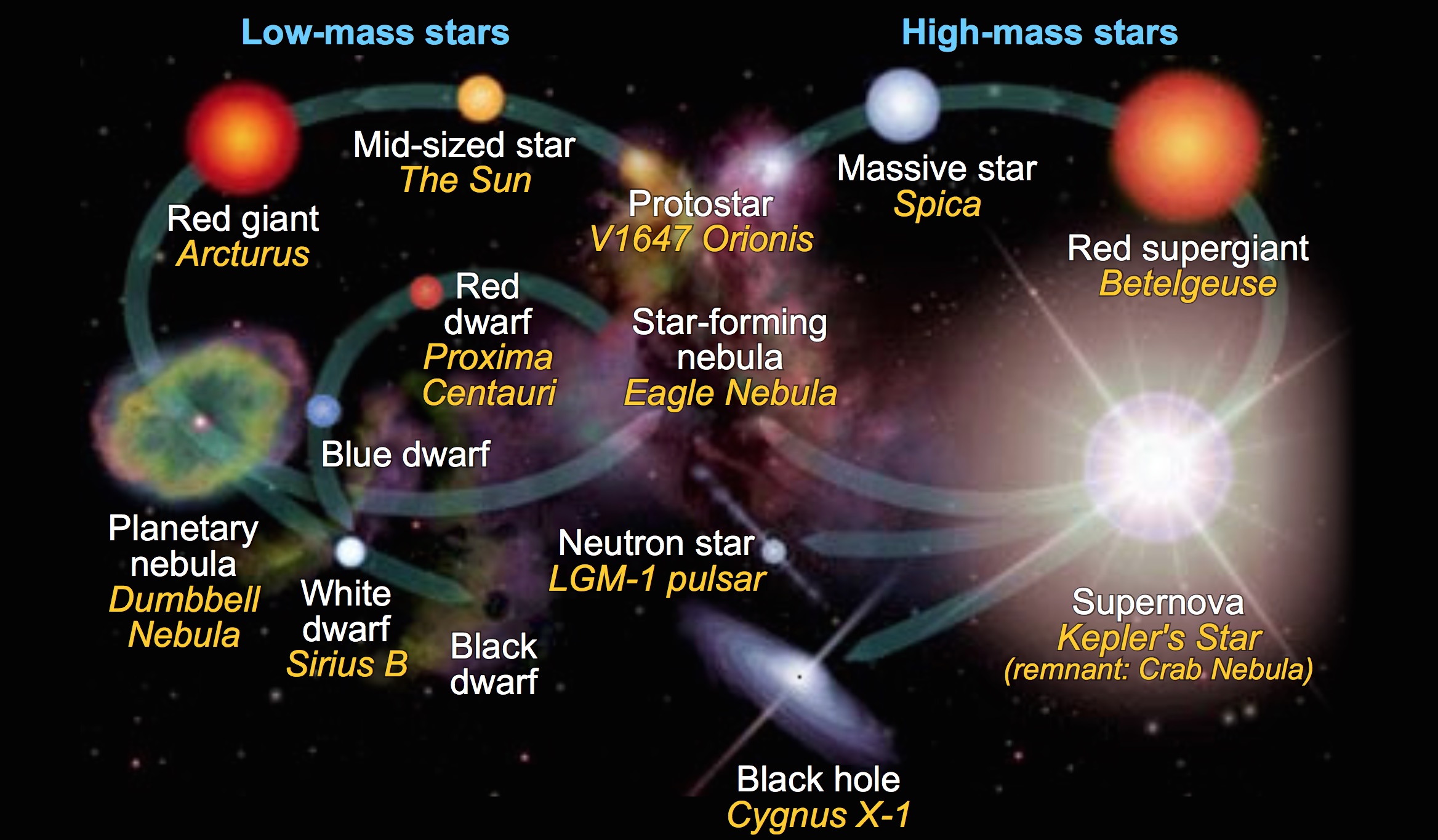

A planetary nebula forms when a star roughly the size of our Sun reaches the end of its life. Our Sun will eventually become one, by the way, in about 5 billion years. The star exhausts the hydrogen in its core and begins fusing heavier elements. This process destabilizes the star's structure, causing it to shed its outer layers into space. What remains is a hot, dense core called a white dwarf—the stellar equivalent of a cinder.

The expelled gas and dust forms what we call a nebula. But here's where it gets interesting: these nebulae aren't uniform, amorphous clouds. They have structure, shape, and personality. Some look like donuts. Others resemble hourglasses, jellyfish, or in the case of the Helix, a cosmic eye staring back at us.

The formation of these structures isn't random. Gravity, stellar winds, magnetic fields, and the original rotation of the dying star all contribute to sculpting the nebula into recognizable shapes. The process isn't instantaneous—it plays out over thousands of years, which is why we can observe snapshots of it. This is stellar geology in motion, and it reveals fundamental truths about how matter behaves under extreme conditions.

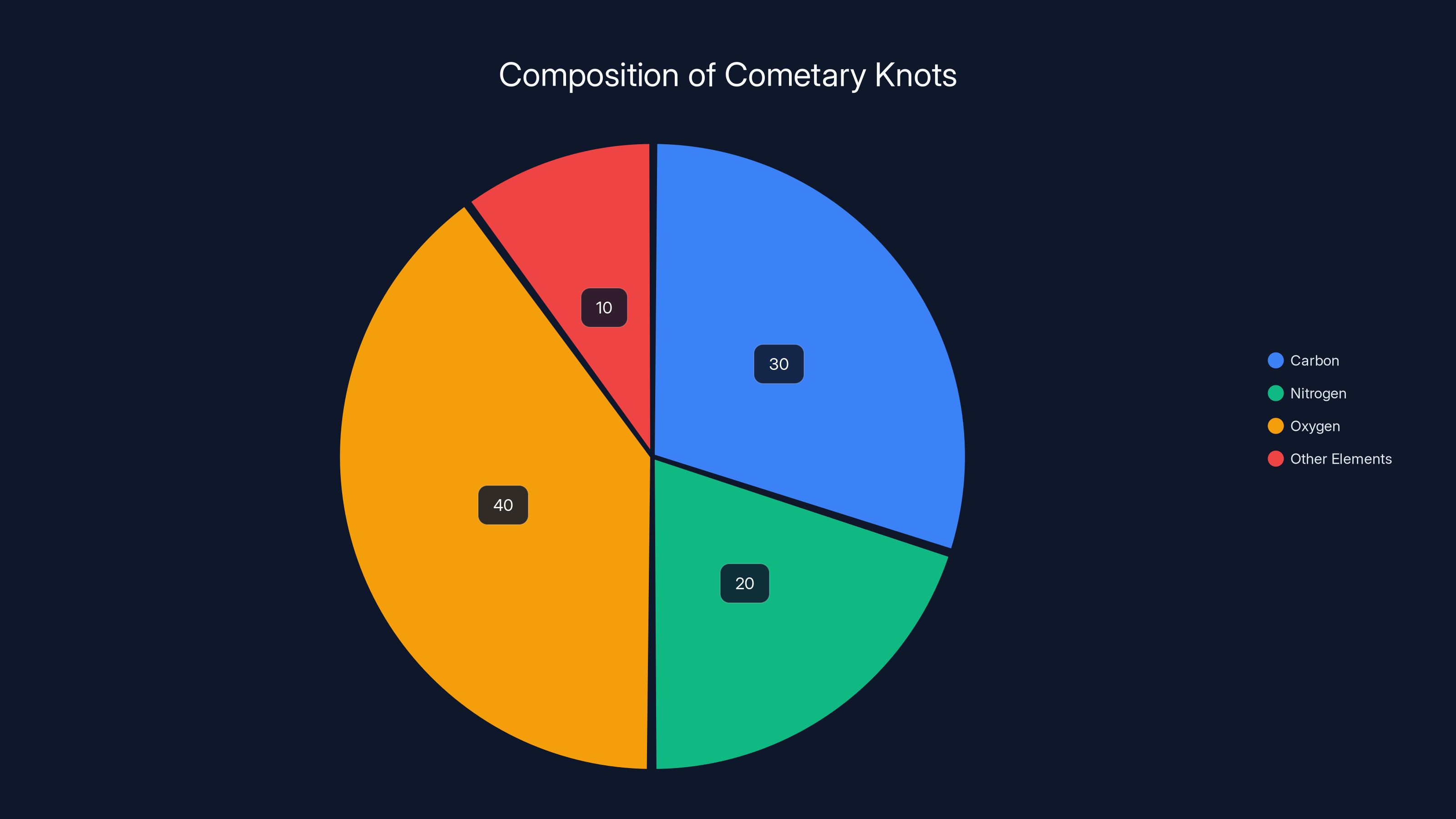

What makes planetary nebulae cosmically important extends beyond aesthetics. These stellar corpses are returning material to the galaxy that was created inside the star. Over millions of years of nuclear fusion, these stars created heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. When a planetary nebula expands, it distributes these elements across light-years of space. Eventually, gravity pulls these enriched clouds together, forming new stars and planetary systems with complex chemistry. You could say we're all stardust in the most literal sense.

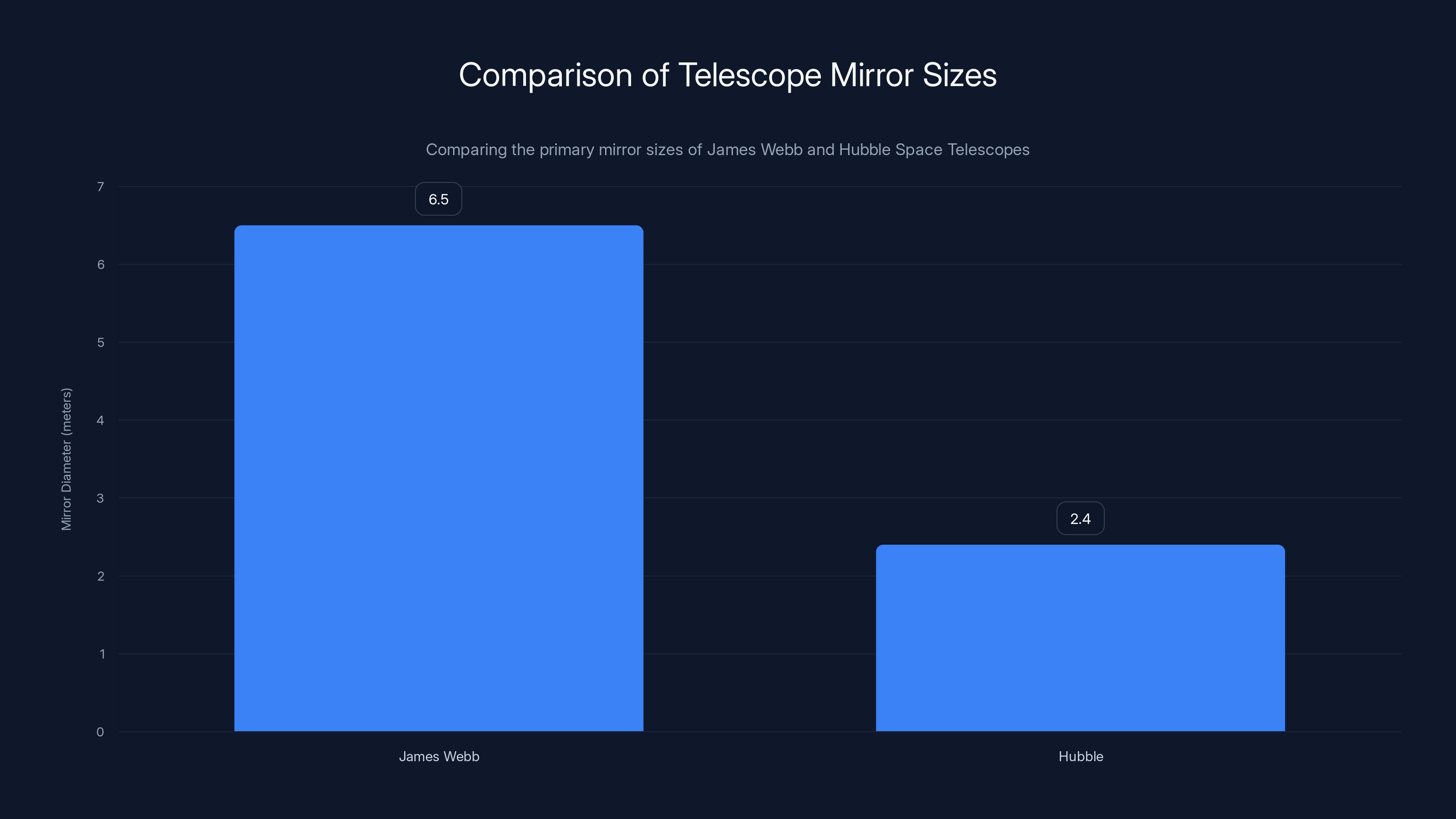

The James Webb Space Telescope has a significantly larger primary mirror (6.5 meters) compared to the Hubble Space Telescope (2.4 meters), allowing for superior angular resolution and the ability to observe finer details.

The Helix Nebula: A Stellar Icon

The Helix Nebula deserves special mention because it's genuinely one of the most famous nebulae in professional and amateur astronomy circles. Discovered in the early 19th century, it's been studied extensively over the past two centuries as telescopic technology improved.

What's fascinating about the Helix is its apparent proximity. At 655 light-years away, it's genuinely close by cosmic standards. For perspective, the famous Orion Nebula is about 1,350 light-years away. The Ring Nebula is roughly 2,600 light-years distant. The Helix's proximity means we can see its details relatively easily, even with older telescopes. That accessibility made it a natural target for observation as each new generation of astronomical instruments came online.

The nebula's nickname, the "Eye of God" or "Eye of Sauron" (depending on your cultural references), comes from its appearance when viewed from afar. The white dwarf at its center appears as a bright pupil surrounded by concentric rings of glowing gas, creating the uncanny impression of a cosmic eye peering at us. When you see wide-angle images of the Helix, you understand immediately why observers felt compelled to assign it such evocative names. It has personality.

But what's particularly exciting about this new Webb image is that it zooms in on a region that older telescopes simply couldn't resolve adequately. We're not seeing the whole nebula anymore—we're seeing details within it, structures at scales that were previously invisible. It's like the difference between seeing someone's face from across a crowded room and suddenly being able to see the individual patterns of their iris.

The James Webb Space Telescope: A Revolutionary Tool for Cosmic Observation

You can't properly understand why this new Helix Nebula image is such a big deal without understanding what the James Webb Space Telescope actually is and why it's so transformative for astronomy.

JWST launched on December 25, 2021, after decades of development and billions of dollars in funding. It immediately became humanity's most powerful space observatory, surpassing the Hubble Space Telescope that had dominated our cosmic vision since 1990. But comparing Webb and Hubble is a bit like comparing a smartphone to a flip phone—sure, they're both communication devices, but the generational leap is profound.

The key difference lies in what wavelengths of light each telescope observes. Hubble primarily operates in visible and ultraviolet light—roughly what our eyes can see, plus a bit beyond. Webb, by contrast, observes primarily in infrared wavelengths. This distinction matters immensely because infrared light passes through cosmic dust clouds that block visible light. Dust is ubiquitous in space. It surrounds newborn stars, fills the spaces between galaxies, and permeates nebulae. Visible light telescopes see dust as obscuring obstacles. Webb sees right through it.

Webb also features a primary mirror composed of 18 hexagonal segments made of beryllium coated with gold. Why beryllium and gold? Beryllium is exceptionally strong and light, while gold is an excellent reflector of infrared light. The segments work together to create an equivalent mirror 6.5 meters in diameter, compared to Hubble's 2.4-meter mirror. This larger aperture means Webb collects more light and can achieve finer detail. The improvement in resolution isn't just incremental—it's revolutionary.

The telescope also includes remarkable engineering innovations. Because infrared observations require extremely cold conditions—Webb operates at around 40 Kelvin (about -233 degrees Celsius)—the telescope incorporates a five-layer sunshield that protects the instrument from the Sun's heat. This shield is roughly the size of a tennis court when fully deployed and was one of the most technically challenging aspects of the entire mission.

The Helix Nebula image released recently comes from Webb's NIRCam instrument, which specializes in near-infrared observation. This particular view reveals the nebula at wavelengths that are mostly invisible to our eyes but carry crucial information about its composition, temperature structure, and dynamics.

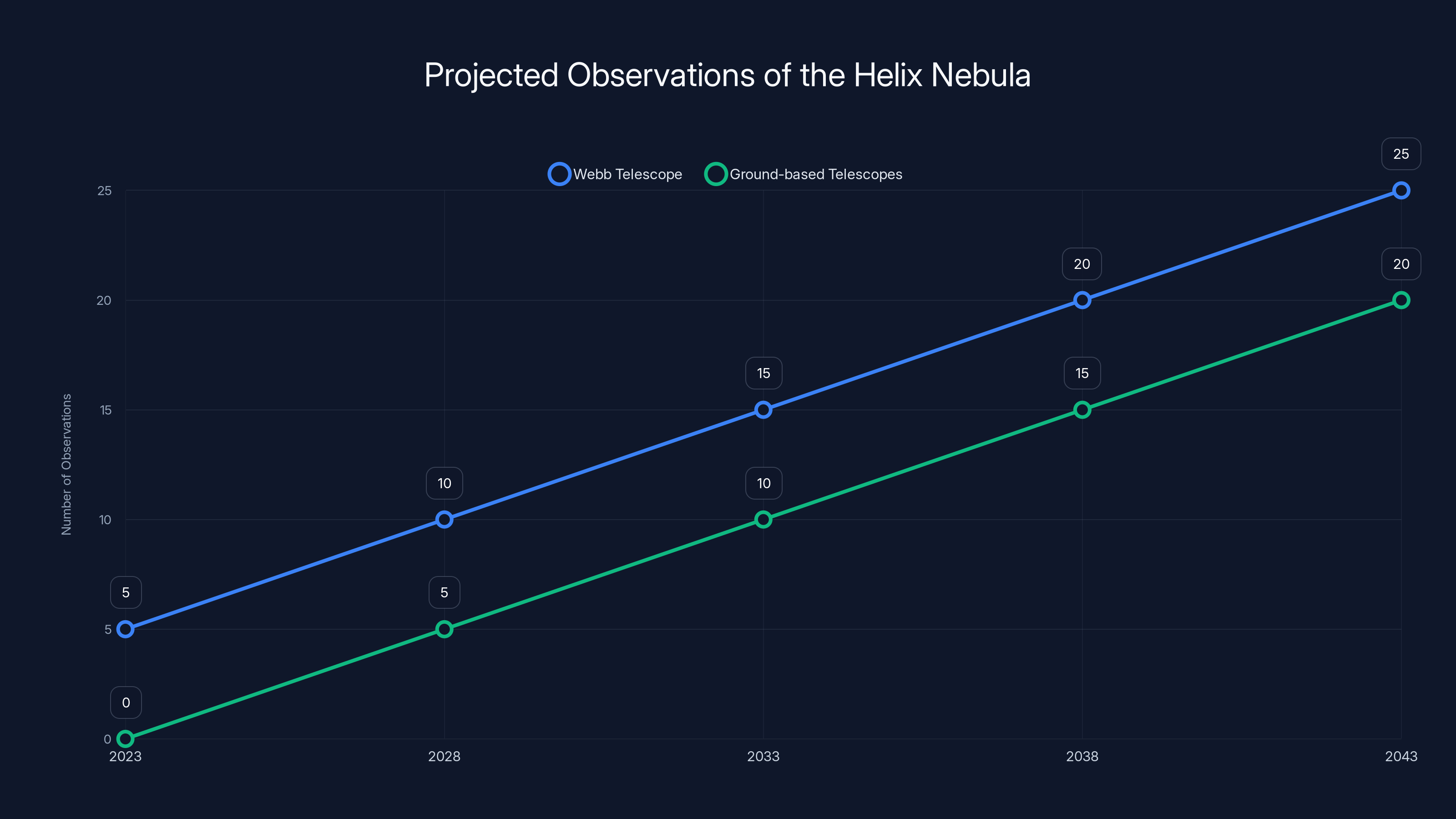

Estimated data suggests that the Webb Telescope and future ground-based telescopes will significantly increase the frequency of observations of the Helix Nebula over the next 20 years.

Cometary Knots: The Most Striking Features

The most visually dominant features in this new Webb image are the cometary knots—those pillar-like structures that resemble comets tails pointing away from the nebula's center. These aren't actually comets, despite the name. They're dense concentrations of gas and dust that have been sculpted into distinctive shapes by the stellar winds flowing from the dying star at the nebula's core.

To understand how these knots form, imagine standing in a wind tunnel where the pressure of the wind increases gradually over time. Objects in that tunnel don't get blown away uniformly. Instead, denser materials develop into distinctive shapes, with less dense materials compressed around them. Now increase the stakes dramatically: the wind in question is a stream of particles traveling at thousands of kilometers per second, originating from a stellar surface at temperatures exceeding 100,000 Kelvin. The materials being shaped have been traveling through space for thousands of years. That's the environment that created these cometary knots.

What's remarkable is that the knots appear to have internal structure. They're not solid, uniform objects. Rather, they seem to contain filaments and layers, suggesting complex dynamics within each knot. Some knots appear to be shedding material, with wisps extending from their heads. Others appear more compact and stable. This variation hints at different ages, compositions, and exposure histories.

The knots are important scientifically because they tell us about the mass-loss process in dying stars. How much material does a star shed? How fast does it move? What's its composition? These questions matter because the answers help us understand stellar evolution across the galaxy. Every star similar to our Sun will eventually go through this phase, eventually returning carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and other elements it created to the interstellar medium.

The colors visible in the knots—ranging from blue to yellow to red—aren't arbitrary. They represent different temperatures and chemical compositions. Blue regions indicate the hottest gas, energized by ultraviolet radiation from the white dwarf at the nebula's center. As you move away from the central source of heating, temperatures drop progressively, and the color shifts to yellow, then red. This temperature gradient is physically meaningful and helps astronomers understand heat distribution throughout the nebula.

Temperature Mapping and Chemical Analysis Through Color

One of the most sophisticated aspects of modern astronomical imaging is what's called spectral analysis or narrowband imaging. Instead of taking single images in visible light the way older telescopes worked, modern instruments like Webb's NIRCam can isolate specific wavelengths of light, essentially creating separate images for different chemical elements and different temperature regimes.

In the Helix Nebula image, the colors we see aren't arbitrary color assignments for aesthetic purposes. They represent real physical properties being measured by the instrument. Different wavelength bands capture light emitted by different atoms and molecules at different temperatures.

The blue regions in the image represent the hottest regions of the nebula. These regions are typically near the white dwarf at the center, where ultraviolet radiation from the star is actively ionizing atoms. When ultraviolet photons strike hydrogen atoms, they strip away electrons, creating ions that emit light at characteristic wavelengths. The blue color in the image often corresponds to ionized hydrogen, helium, and oxygen.

As we move outward from the center, temperatures decline. At intermediate temperatures, different atomic transitions become dominant. Singly ionized nitrogen emits in yellow wavelengths. Neutral hydrogen molecules (H2) emit in infrared. The transition from blue to yellow to red in the nebula effectively maps temperature from hot to cool.

The reddish-orange regions represent the coolest material, where gases have cooled enough that dust grains can form. Dust grain formation is significant because dust changes how light interacts with the gas. Dust absorbs certain wavelengths and reemits others, which is why the appearance changes so dramatically in the outer regions of the nebula.

This temperature mapping has direct scientific value. By understanding the temperature distribution, astronomers can calculate the density of material in different regions, estimate the velocity of the stellar winds, and model how the nebula will continue to evolve over the next thousand years. The image becomes a data set, not just a pretty picture.

Estimated data shows oxygen as the most prevalent element in cometary knots, followed by carbon and nitrogen, reflecting typical stellar compositions.

The Central White Dwarf: A Stellar Corpse

While the cometary knots dominate the visible composition of this Webb image, they're not the most important object in the frame. That distinction belongs to the white dwarf at the center—the remnant of the original star that lost all these layers.

White dwarfs are among the most exotic objects in the universe. They're the ultra-dense cores of dead stars, typically with masses comparable to our Sun but compressed into a volume the size of Earth. A teaspoon of white dwarf material would weigh roughly a ton. Their density is so extreme that normal atomic structure breaks down. Electrons are compressed into degenerate states where quantum mechanical effects dominate, preventing further collapse.

The white dwarf in the Helix isn't visible in this particular image because it's too faint compared to the bright nebula surrounding it. But its presence is undeniable—the entire nebula's structure is sculpted by the radiation and stellar winds emanating from this invisible furnace at the center. The white dwarf is actively heating the nebula and pushing the gas outward, maintaining the structure we observe.

Over the course of centuries and millennia, the white dwarf will gradually cool. Our own Sun will eventually become a white dwarf, and after several trillions of years (longer than the current age of the universe), it will cool to become a black dwarf. Don't worry though—we have time. Lots of time.

The presence of a white dwarf at the center of a planetary nebula tells us something crucial about the nebula's age. White dwarfs cool predictably according to physical theory. By measuring a white dwarf's temperature, astronomers can estimate how long ago the nebular ejection occurred. The Helix Nebula's white dwarf suggests that the mass-ejection event began roughly 6,600 years ago. That means the nebula we see today is still relatively young in cosmic terms, still expanding, still evolving.

The Dying Star's Winds: Sculptors of the Cosmic Canvas

When we talk about stellar winds from a dying star, we're describing something genuinely violent and energetic. The dying star isn't gently releasing material into space like steam from a kettle. It's actively expelling gas at speeds of hundreds of kilometers per second. These aren't subsonic winds—they're supersonic, moving faster than sound waves can propagate through the surrounding gas.

When an extremely fast-moving wind encounters slower-moving material (like the shells of gas ejected by the star in its previous evolutionary stages), shocks form. Shocks are abrupt discontinuities in pressure, density, and temperature. The energy in these shocks heats the gas dramatically, causing it to emit light across a broad spectrum.

The interaction between the stellar wind and the pre-existing shells creates the distinctive structures we see in the nebula. The cometary knots aren't randomly distributed—they form where wind pressure meets maximum resistance from denser material. The tails of the knots form as the wind pushes on the densest material while streaming around the sides.

This wind-structure interaction is the key to understanding the nebula's current appearance. In a few thousand years, the winds will have pushed all this material much farther from the center. The nebula will become larger, dimmer, and more diffuse. Eventually—in tens of thousands of years—the nebula will dissipate entirely, merging back into the interstellar medium. The structures we see today are ephemeral, beautiful, but ultimately temporary.

The James Webb Space Telescope vastly surpasses the Hubble in mirror size and infrared capabilities, operating at much colder temperatures for enhanced cosmic observation. Estimated data for wavelength range (Hubble: visible/UV=2, Webb: infrared=10).

Comparative Planetary Nebulae: How the Helix Measures Up

The Helix Nebula is far from being the only planetary nebula in the galaxy. There are thousands of known planetary nebulae, and estimates suggest hundreds of thousands actually exist in the Milky Way. So how does the Helix compare to its cousins?

Some planetary nebulae, like the Ring Nebula in the constellation Lyra, display nearly perfect geometric symmetry. The Ring Nebula appears as a nearly perfect smoke ring, presumably because we're viewing the nebula almost exactly edge-on. Other nebulae display dramatic asymmetries, suggesting that the original dying star had a companion star whose gravity influenced the mass ejection process.

The Helix Nebula occupies a middle ground in terms of complexity and apparent symmetry. It shows overall circular structure when viewed from a distance, but detailed examination reveals intricate substructure. The cometary knots, in particular, are more prominent in the Helix than in many other planetary nebulae. This distinctive feature has made the Helix particularly interesting to study.

In terms of apparent size, the Helix is genuinely large. It spans about 55 arc-minutes of sky—roughly twice the diameter of the full moon as seen from Earth. This apparent size makes it accessible to amateur astronomers with moderate equipment, which is why it's been observed so extensively. Many nebulae are either too distant or too faint to observe except through large professional telescopes, but the Helix is within reach of enthusiasts.

The nebula's intrinsic size (not just how large it appears to us, but its actual physical dimensions) is roughly 0.65 light-years across. That's substantial but not enormous by nebular standards. Some planetary nebulae span several light-years. The Helix's size and age suggest it's past its period of most rapid expansion, moving into a phase of slower, more gradual dispersal.

Previous Observations: How Webb Changes Our Perspective

Before Webb came online, the most detailed observations of the Helix Nebula came from the Hubble Space Telescope, particularly observations made in 2004 by the Wide Field Camera 3 instrument. Those images, taken in visible light wavelengths, showed remarkable detail and gave astronomers their first clear view of the nebula's overall structure and the general distribution of its material.

The 2004 Hubble images were transformative for Helix Nebula studies. Astronomers could identify the individual cometary knots, study their spacing and distribution, and note their morphological characteristics. The images revealed that the nebula was more complex than initially thought, with intricate structures at multiple scales.

But here's where Webb takes things to a different level. By observing in infrared wavelengths, Webb can penetrate dust that obscures visible light observations. This means structures that Hubble could barely resolve become crystal clear in the Webb imagery. Additionally, Webb's superior angular resolution means smaller structures become visible.

The comparison between Hubble and Webb observations of the Helix illustrates the generational leap in observational capability. Where Hubble could show the general distribution of material, Webb can show the internal structure of individual knots. Where Hubble could suggest the presence of filaments and density variations, Webb can resolve them with stunning clarity.

This improved clarity has allowed astronomers to refine their models of how the nebula formed and evolved. Detailed measurements of the knots' shapes and sizes provide constraints on wind velocities and mass-loss rates. Understanding the composition through spectral analysis gives insight into the star's nuclear fusion history.

The Helix Nebula stands out for its large apparent size and complexity, while the Ring Nebula is noted for its symmetry. Estimated data reflects typical values for comparison.

Stellar Evolution and the Life Cycle of Matter

The Helix Nebula isn't just visually interesting—it's a laboratory for understanding one of the most fundamental processes in the universe: how stars die and redistribute their material back to space.

Stars spend most of their lives in a state of equilibrium, with the outward pressure from fusion in the core balanced by inward gravitational pressure. For a star like our Sun, this equilibrium lasts roughly 10 billion years. But when the core runs out of hydrogen fuel, the balance shifts.

What happens next depends critically on the star's mass. The Helix Nebula's progenitor star was probably roughly 1.5 to 2 times the mass of our Sun. Such stars undergo a complex series of evolutionary stages after leaving the main sequence. They become red giants, then asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, experiencing multiple episodes of mass loss. During the AGB phase, a star can lose a significant fraction of its mass to space through powerful stellar winds.

Eventually, after shedding these outer layers, the hot stellar core is exposed—the white dwarf we discussed earlier. This white dwarf emits intense ultraviolet radiation that ionizes the surrounding gas, causing it to glow. The result is what we observe: a planetary nebula.

This process has profound implications for galactic evolution. The material in the dying star—carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, silicon, iron, and other elements created through nuclear fusion—gets returned to the galactic disk. This enriched material subsequently becomes part of new interstellar clouds. Eventually, new stars form from these clouds, incorporating the heavy elements from their predecessors.

This recycling process means that every star is essentially a cosmic furnace, converting light elements into heavier ones and then returning the processed material for recycling. Our own Sun and planets are made from material processed through multiple stellar generations. The iron in your blood came from fusion in a massive star. The calcium in your bones came from stellar fusion. The oxygen you're breathing was created in a star's furnace. In the most literal sense, we are stardust.

Implications for Understanding Mass Loss in Evolved Stars

One of the central problems in astrophysics is understanding how evolved stars lose mass and at what rate. Mass loss shapes a star's final evolutionary state, determines whether it ends its life as a white dwarf or collapses catastrophically, and influences the chemical composition of planetary nebulae.

Theoretically, astronomers can model stellar winds based on first principles—understanding the physics of hot gas expanding away from a high-gravity object. But observations often reveal discrepancies between theoretical predictions and reality. The winds appear to be more concentrated, more clumpy, and more structured than simple models predict.

The detailed Webb images of the Helix Nebula provide crucial observational constraints for refining these models. By measuring the sizes, shapes, and spacing of the cometary knots, astronomers can infer the properties of the wind that created them. The knots themselves represent density enhancements—regions where stellar wind compression created higher concentrations of material.

Understanding the physics of these wind-sculpted structures helps astronomers build better models of how all evolved stars shed their outer layers. This knowledge cascades into broader astrophysical understanding. How much dust is returned to the galaxy by dying stars? What's the chemical composition of this returned material? These answers have implications for understanding galactic chemical evolution, for understanding the formation of new stars and planets, and for understanding our own cosmic origins.

The Role of Spectroscopy in Nebular Analysis

While the stunning images from Webb capture our imagination, the real power of modern astronomical observation lies in spectroscopy—the ability to analyze light across many different wavelengths simultaneously and extract information about composition, temperature, density, and motion.

Spectroscopy works by dispersing light into its component wavelengths, similar to how a prism creates a rainbow. Each element emits light at characteristic wavelengths when heated or ionized. By analyzing the spectral lines, astronomers can determine what elements are present and in what abundance.

In the case of the Helix Nebula, spectroscopic observations have revealed the presence of hydrogen (the most abundant element), helium, nitrogen, oxygen, and other heavier elements. The relative abundances tell us about the fusion history of the original star. A star that spent a long time fusing helium will produce abundant carbon and oxygen. A star with different evolutionary history will produce different elemental abundances.

Additionally, the width and shape of spectral lines tell us about motion. Atoms moving toward us produce slightly blue-shifted light (shorter wavelengths due to the Doppler effect), while atoms moving away produce red-shifted light (longer wavelengths). By analyzing these shifts, astronomers can determine how fast material is moving and in what direction.

Measuring the broadening of spectral lines also reveals temperature. Hotter material has atoms moving at higher speeds, causing broader, less distinct spectral lines. Cooler material produces sharper, more well-defined lines. By analyzing multiple spectral features, astronomers can create a detailed map of the temperature and density distribution throughout the nebula.

Webb's spectroscopic capabilities, particularly through its NIRSpec instrument, complement the imaging capabilities beautifully. Future spectroscopic observations of the Helix Nebula will provide this detailed compositional and kinematic information, deepening our understanding of the nebula beyond what beautiful images alone can convey.

Dust Formation and the Birth of Future Stars

One aspect of planetary nebulae that often gets overlooked is the dust. Spectral observations and infrared imaging reveal that planetary nebulae contain dust—solid particles typically composed of carbon, silicates, and other materials. This dust is crucial because it eventually provides the building blocks for rocky planets.

Dust in planetary nebulae forms through interesting chemistry. Atoms combine into molecules, which aggregate into larger particles. This process is thermodynamically favorable only at relatively low temperatures, which is why dust forms preferentially in the cooler outer regions of nebulae.

The dust is important scientifically and philosophically. Scientifically, it affects how light propagates through the nebula, which is why infrared observations like Webb's are so valuable—infrared light penetrates dust much more effectively than visible light. Philosophically, the dust returned to space by dying stars becomes the foundation for new planets and planetary systems. Any rocky exoplanet ever discovered owes its existence ultimately to dust grains that formed in a planetary nebula billions of years ago.

In a few million years, the ejected material from the Helix Nebula will merge back into the interstellar medium. The dust grains in particular will become part of new stellar nurseries. When new stars ignite in those regions, the dust surrounding them will be heated, compressed, and will begin aggregating into larger bodies. Eventually, planets will form from this material. The material we see being ejected by the dying star in the Helix Nebula might contribute to a planetary system around a new star, perhaps eventually hosting life. It's the ultimate long-term recycling program.

Technological Limitations and Future Observations

While the new Webb images represent a revolutionary improvement over previous observations, they still represent a single snapshot in time. To truly understand the Helix Nebula's dynamics and evolution, astronomers need multiple observations over extended time periods.

Fortunately, Webb's mission profile allows for exactly this kind of long-term monitoring. The telescope is expected to continue operating for at least another 15-20 years, potentially much longer if its current health trajectory continues. During that time, astronomers will observe the Helix Nebula repeatedly, watching for changes in the structures we see today.

Future observations might reveal proper motion—the actual movement of material through space as the nebula expands. Currently, the nebula's expansion is inferred from velocity measurements obtained through spectroscopy. But Webb's angular resolution is so fine that eventually, direct measurement of positional changes might become possible. This would provide the most direct measurement yet of the nebula's expansion rate.

Additionally, Webb will be joined in the coming decade by other advanced observatories. The next generation of ground-based telescopes—particularly the Extremely Large Telescope currently under construction in Chile and the Thirty Meter Telescope—will eventually surpass even Webb's capabilities for certain observations. When these telescopes come online, the Helix Nebula will again become a natural target for observation.

The combination of these observatories will create an unprecedented picture of the Helix Nebula. Infrared data from Webb will be combined with visible-light data from ground-based telescopes. Spectroscopic observations will be coordinated across multiple instruments. The result will be a comprehensive, multi-wavelength understanding of how this nebula is structured, how it's evolving, and what it tells us about stellar death and cosmic recycling.

The Emotional and Philosophical Impact of Cosmic Imagery

Beyond the science, there's something profound about images like this new Webb view of the Helix Nebula. They connect us to something larger than ourselves. In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, images of the cosmos provide perspective. They remind us that we're part of something vast, ancient, and beautiful.

This isn't unscientific or sentimental. The emotional response to cosmic imagery is fundamentally connected to the intellectual understanding of what we're seeing. When you understand that you're looking at matter being returned to space by a dying star, knowing that this material will seed new stars and planets, you're experiencing a kind of cosmic humility that's profoundly human.

There's also an element of connection across time. Light from the Helix Nebula spent 655 years traveling to reach us. The image we see shows the nebula as it was in roughly the year 1370. In a very real sense, we're seeing ancient light, witnessing an event that happened in the 14th century. The astronauts who were at the telescope when this observation was made were looking backward in time.

This temporal dimension adds another layer to the experience of viewing cosmic images. We're not just seeing distant space; we're seeing distant time. The death of this star is happening right now in cosmic terms, even though the light showing us that death traveled through space for centuries to reach us.

The Future of Astronomical Observation and Discovery

The Helix Nebula image is just one example of what Webb is revealing about the universe. The telescope's ongoing survey of the cosmos continues to produce images and data that challenge our understanding and expand our knowledge.

Mission scientists estimate that Webb's current fuel supply supports operations until 2033 or beyond. That means another eight to ten years of observations, potentially revealing structures and phenomena that we haven't even thought to look for yet. Part of the excitement of observational astronomy is that observations often reveal unexpected details that spark new theoretical investigations.

What excites astronomers most about Webb isn't necessarily that it's confirming predictions. It's that observations are revealing details that theories didn't predict, complexity that models hadn't anticipated. This is how science progresses. Observations challenge theories, theories are refined, predictions are tested against new observations. The Helix Nebula is participating in this process, contributing data that will refine our understanding of stellar death and evolution.

Looking further ahead, the next generation of astronomical facilities promises to extend our capabilities even further. The Habitable Worlds Observatory (currently in the planning stages) will be an infrared telescope even more powerful than Webb, designed specifically to study exoplanetary atmospheres and search for signs of habitability. The ground-based extremely large telescopes will provide complementary observations at visible and infrared wavelengths.

Within perhaps two decades, we might have images of planetary nebulae with resolution approaching what we achieve for nearby stars today. We might be able to watch nebulae evolve in real time, measuring the expansion and evolution over years rather than centuries. The Helix Nebula, being relatively nearby and relatively bright, will likely be a frequent target for observation as new facilities come online.

Bringing It Together: Why This Moment Matters

Why does this image of the Helix Nebula matter? On the surface, it's a beautiful photograph of a distant nebula. Diving deeper, it's a detailed scientific dataset revealing the physics of stellar death. But perhaps most importantly, it represents a moment in human history when we've developed technology sophisticated enough to see cosmic details that were previously invisible, to understand processes that were previously mysterious.

The Helix Nebula has been there for 655 years' worth of light travel time. Humans have observed it since the early 1800s. But only now, with Webb, can we see the intricate details that hint at the profound physics happening there. Only now can we begin to truly understand the dying star's wind, the cometary knots' formation, the temperature distribution throughout the nebula.

This improved capability isn't just about accumulating knowledge for knowledge's sake. Understanding how stars die informs understanding of how stars are born, how planets form, how chemistry enables complexity, and ultimately how we came to exist. The dust in the Helix Nebula will become part of the universe's future. The insights we gain from studying it inform our understanding of cosmic processes that sustain the galaxy.

When everything feels overwhelming here on Earth, images like this new Helix Nebula photograph remind us that there's profound beauty in the universe, that human ingenuity can achieve remarkable things, and that there are mysteries worth investing in to understand. That's why this image matters—not just as a scientific achievement, though it certainly is that, but as a reminder of what's possible when we turn our attention to the cosmos.

FAQ

What is the Helix Nebula?

The Helix Nebula is a planetary nebula located approximately 655 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius. It's one of the closest planetary nebulae to Earth, making it a popular target for astronomical observation. The nebula was discovered in the early 19th century and gets its distinctive "Eye of God" or "Eye of Sauron" nickname from its appearance, with a white dwarf at the center surrounded by concentric rings of glowing gas and dust.

What is a planetary nebula?

A planetary nebula forms when a dying star sheds its outer layers into space. The expelled gas and dust create visible structures that early astronomers mistakenly thought resembled planets, giving them their name. The hot white dwarf core that remains after the ejection energizes the surrounding gas through ultraviolet radiation, causing it to glow brightly. Planetary nebulae play a crucial role in returning heavy elements created through stellar fusion back to the interstellar medium, which eventually forms new stars and planets.

Why are the cometary knots important to study?

The cometary knots in the Helix Nebula are dense clouds of gas and dust sculpted into distinctive pillar-like shapes by the stellar winds from the dying star's core. Studying these structures helps astronomers understand mass-loss mechanisms in evolved stars, the interaction between stellar winds and pre-existing materials, and the physical conditions in planetary nebulae. The knots serve as laboratories for understanding some of the most extreme physical processes in the universe.

How does the James Webb Space Telescope improve upon previous observations?

The James Webb Space Telescope observes primarily in infrared wavelengths, which allows it to penetrate through dust that obscures visible light. Its much larger primary mirror (6.5 meters compared to Hubble's 2.4 meters) provides superior angular resolution, revealing fine details that were previously invisible. Webb can detect and measure structures much smaller and fainter than previous telescopes could observe, providing unprecedented clarity of nebular features.

What do the different colors in the Webb image represent?

The colors in astronomical images typically represent different wavelengths of light or different elements and temperatures. In the Helix Nebula image, blue regions represent the hottest gas near the white dwarf, energized by ultraviolet radiation. Yellow regions indicate intermediate temperatures where hydrogen molecules emit light. Red and orange regions represent the coolest material at the nebula's edges, where dust begins to form. These color assignments allow astronomers to visualize temperature and composition distributions throughout the nebula.

What will happen to the Helix Nebula in the future?

The Helix Nebula will continue expanding and gradually dispersing over tens of thousands of years. The stellar winds from the white dwarf at its center will push the material farther into space. Eventually, the nebula will become too diffuse to observe, and its material will merge back into the interstellar medium. The dust and gas from the Helix Nebula may eventually become part of new stellar nurseries, contributing to the formation of new stars, planets, and potentially even life-supporting systems.

How does this observation help us understand stellar evolution?

Planetary nebulae like the Helix represent a specific phase in stellar evolution that all stars similar to our Sun will eventually experience. By studying the Helix Nebula's detailed structure, composition, and dynamics, astronomers refine their understanding of how evolved stars lose mass, what happens to the material they eject, and how this process contributes to galactic chemical evolution. This knowledge applies broadly to understanding how stars throughout the universe progress through their life cycles.

Why is the Helix Nebula called the "Eye of Sauron"?

When viewed from a distance in wide-angle observations, the Helix Nebula's circular structure with a bright white dwarf at its center resembles a cosmic eye staring outward. The nickname "Eye of God" or "Eye of Sauron" (the latter referencing the fictional eye from Tolkien's work) comes from this striking visual resemblance. The nomenclature is informal but has become popular in both professional and amateur astronomy communities.

How old is the Helix Nebula?

Based on observations of the white dwarf's temperature and theoretical models of how white dwarfs cool, astronomers estimate that the Helix Nebula's mass-ejection event began approximately 6,600 years ago. By cosmic standards, this makes the nebula relatively young and still actively evolving. The nebula continues to expand as the stellar winds from the white dwarf push material outward.

Will the James Webb Space Telescope continue observing the Helix Nebula?

Yes, Webb's mission is expected to continue for at least 15-20 years beyond its current operational status, potentially much longer. Astronomers plan to observe the Helix Nebula repeatedly during this period to track changes in the nebular structure, measure expansion rates, and gather additional spectroscopic data about composition and kinematics. Future observations will be complemented by data from next-generation ground-based telescopes currently under construction.

The Beauty of Stellar Recycling

When we look at this incredible new Webb image of the Helix Nebula, we're witnessing one of the universe's most fundamental processes: a star returning its material to space, seeding future generations of stars and planets. The cometary knots we see aren't just beautiful structures—they're evidence of physics at work, wind and gravity and temperature interacting in ways that shape the cosmos.

What strikes me most is the perspective this image provides. In a time when the news feels relentlessly negative, when global challenges seem insurmountable, here's a reminder that the universe continues its ancient processes. Stars die, their material is recycled, new stars and planets form. This has been happening for billions of years and will continue for billions more.

The Helix Nebula, dying though its star may be, represents hope in a cosmic sense. That death enables new life. The heavy elements created in that dying star will become part of future worlds. The complexity we see in those cometary knots—the intricate structures sculpted by stellar winds—reminds us that nature, given sufficient time and energy, creates remarkable things.

The next time you feel overwhelmed by earthly concerns, remember that right now, 655 light-years away, that cosmic eye is staring back at us, showing us a fundamental truth: from death comes new beginning, from chaos comes beauty, and from understanding comes connection to something profoundly larger than ourselves. That's the real story this image tells.

Key Takeaways

- James Webb captured unprecedented detail of the Helix Nebula's cometary knots, revealing structures invisible to previous telescopes.

- Cometary knots form where stellar winds from the white dwarf collide with pre-existing shells of ejected gas, creating distinctive pillar-like shapes.

- Temperature mapping through color analysis shows the nebula spans from ultraviolet-energized hot gas near the core to cool dust-forming regions at the edges.

- The Helix Nebula represents a crucial phase in stellar evolution, with material being recycled back to space to form new stars, planets, and potentially life.

- Webb's infrared observation capability penetrates cosmic dust and achieves angular resolution far superior to visible-light telescopes, revolutionizing nebula studies.

![James Webb's Helix Nebula Image Reveals Cosmic Death and Rebirth [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/james-webb-s-helix-nebula-image-reveals-cosmic-death-and-reb/image-1-1768934214848.jpg)