Introduction: The Universe's Invisible Majority

In late 2024, something extraordinary happened in the world of astronomy. Scientists looked at what they'd thought were four random clusters of stars floating in the void and realized they were actually part of something much bigger. Something that was almost entirely invisible.

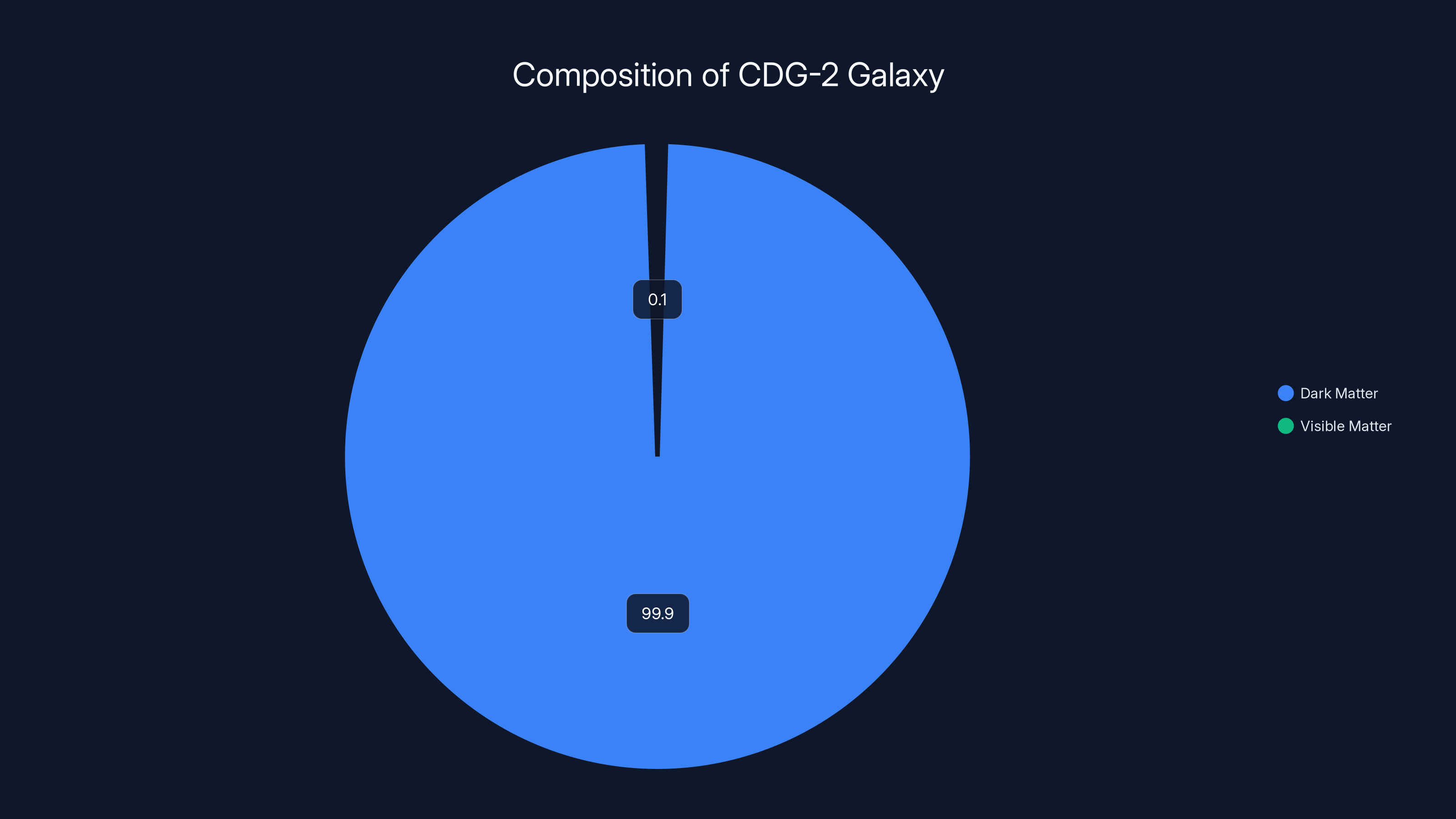

We're talking about a galaxy named CDG-2, located about 300 million light-years away in the Perseus cluster. And here's the mind-bending part: approximately 99.9 percent of this galaxy's mass consists of dark matter. That means for every bit of normal stuff you can see—stars, gas, dust, the things we're made of—there's roughly 1,000 times more matter that doesn't emit light, doesn't reflect light, doesn't interact with light at all, as confirmed by Space.com.

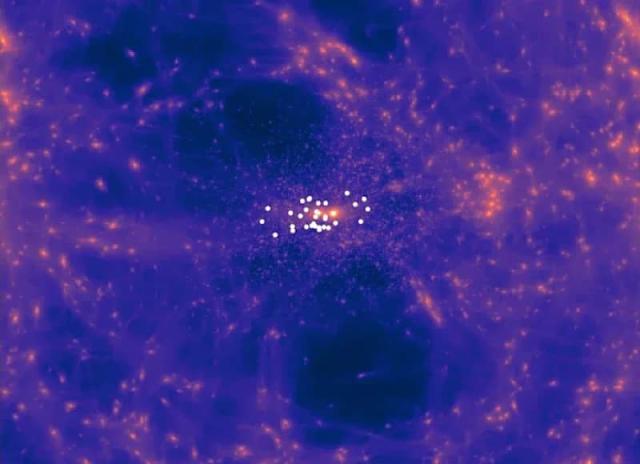

For decades, astronomers have known dark matter exists. They've inferred its presence from gravitational effects. They've built models around it. They've written equations describing how it should behave. But actually observing a galaxy where dark matter dominates so completely? That's unprecedented. It's like knowing invisible wind exists because leaves move, then finally seeing a place where the wind is so strong it's unmistakably, undeniably real.

This discovery matters for reasons that go beyond "that's cool." Dark matter represents one of the deepest mysteries in physics. We don't know what it's made of. We don't know how to detect it directly. We only know it's there because of what it does to things we can see. CDG-2 is essentially a natural laboratory, a cosmic oddity that lets scientists test their theories about how galaxies form, how dark matter behaves, and what really makes up the universe, as discussed in Big Think.

The discovery also changes how we think about the night sky itself. It suggests that the universe contains far more galaxies than we've ever realized—whole populations of nearly invisible systems that previous telescopes simply couldn't detect. They're out there, hiding in plain sight, waiting for better instruments to reveal them.

Let's dive into what researchers actually found, how they found it, and what it means for our understanding of the cosmos.

TL; DR

- 99.9 percent dark matter: CDG-2 is the first confirmed galaxy where dark matter comprises nearly all the mass, with visible matter making up just 0.1 percent

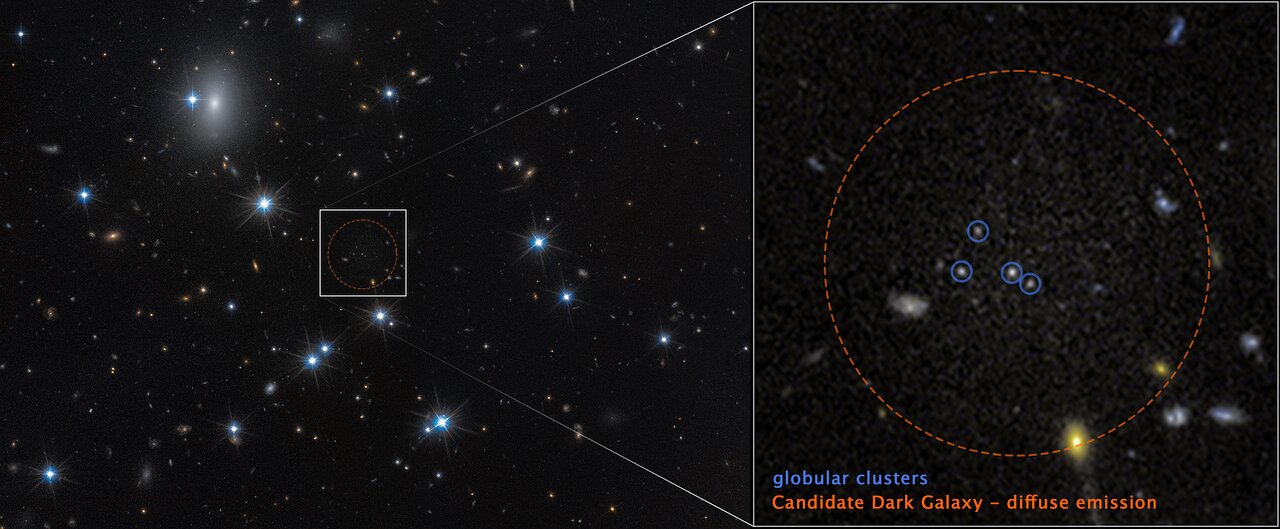

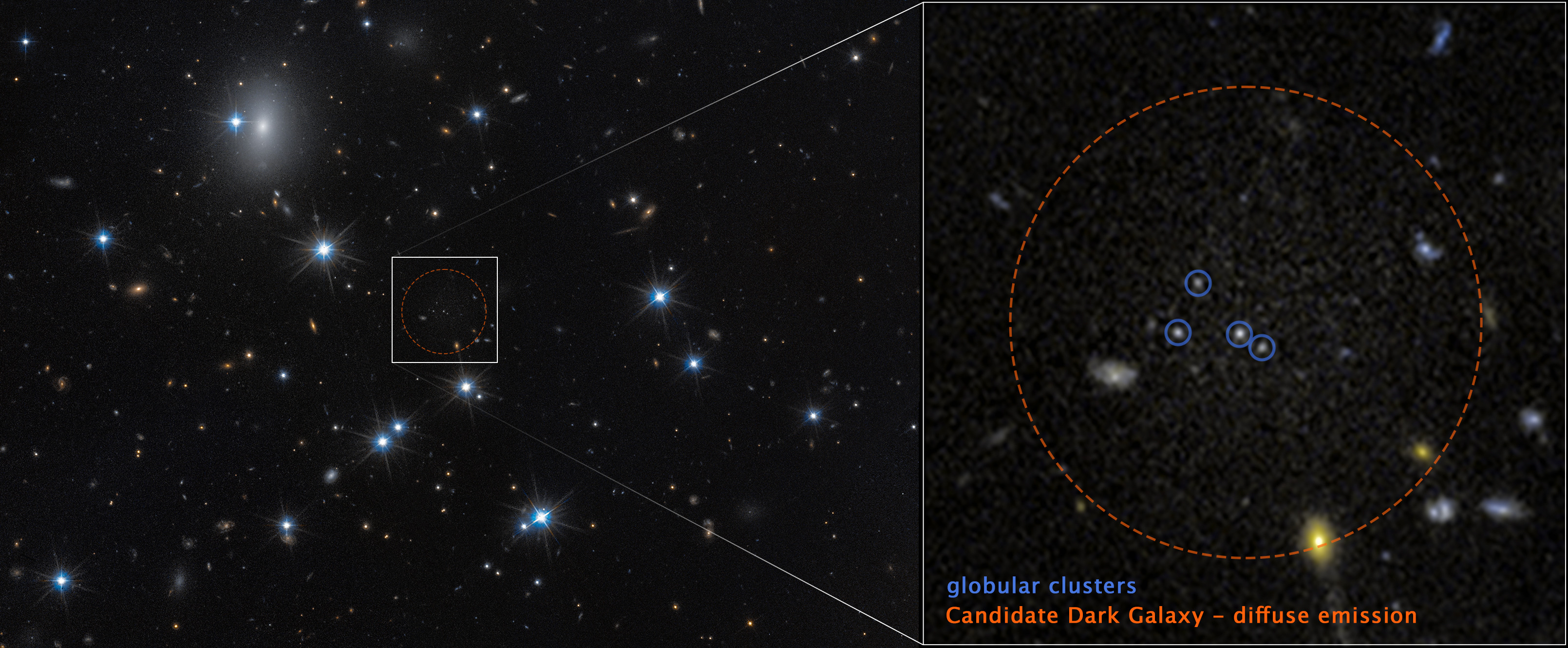

- Hidden in plain sight: Four globular star clusters were initially thought to be separate objects until combined telescope data revealed they're part of one faint galaxy

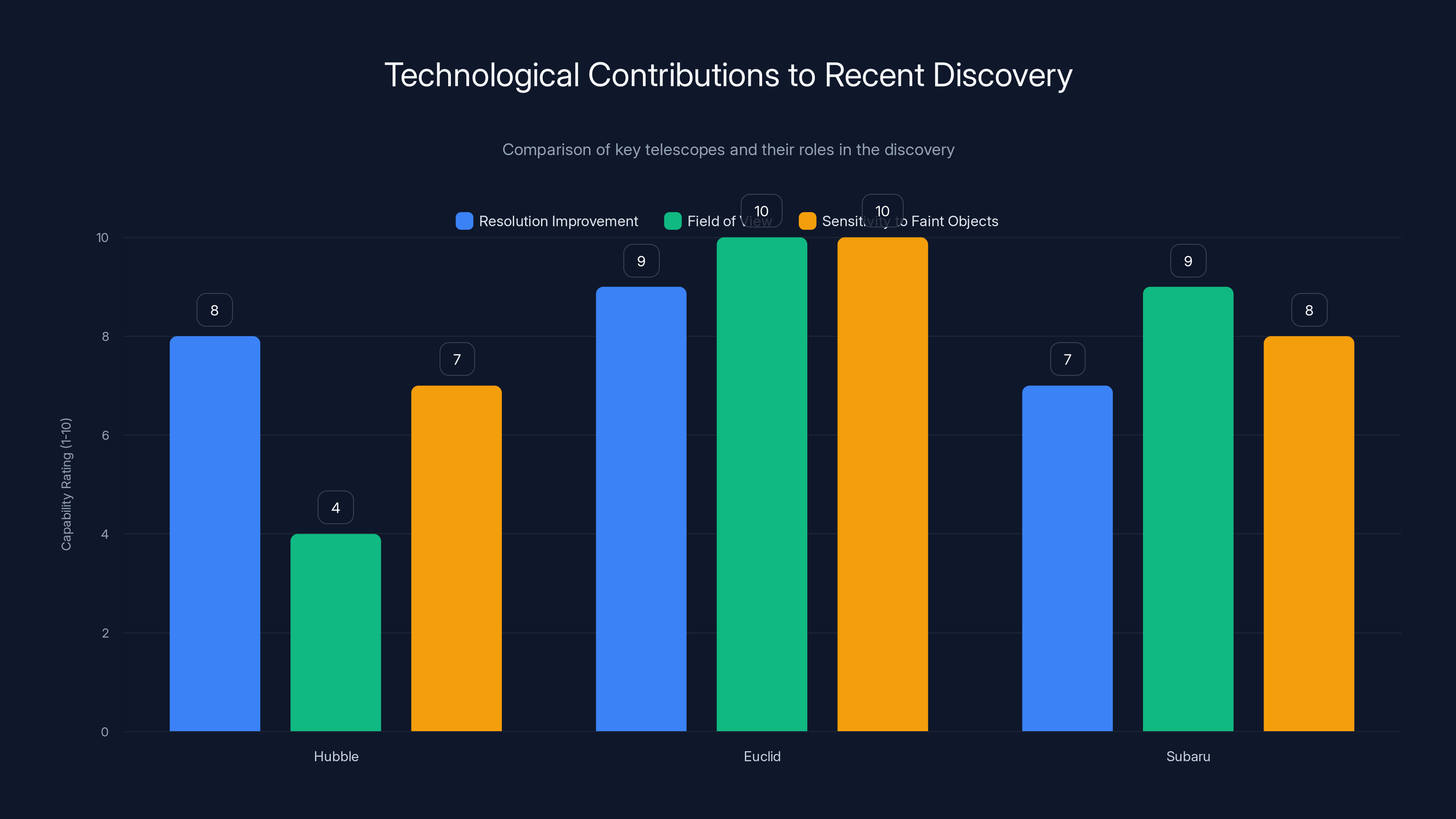

- Three telescopes confirmed it: Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru telescope observations combined revealed an extremely faint glow surrounding the star clusters

- Tests dark matter models: CDG-2 serves as a natural laboratory for understanding dark matter behavior and galaxy formation theories

- More invisible galaxies exist: This discovery suggests the universe contains numerous dark galaxies we've never detected before, fundamentally changing how we count galaxies

The chart illustrates the contributions of Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru telescopes to the recent discovery, highlighting Euclid's superior field of view and sensitivity. Estimated data.

What Is Dark Matter, Anyway?

Before understanding CDG-2, you need to understand dark matter itself. And honestly, that's tricky because dark matter is fundamentally unobservable. It doesn't produce light. It doesn't absorb light. It doesn't reflect light. It's completely invisible across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays.

So how do scientists know it exists?

Gravity. That's it. That's the whole argument.

In the 1930s, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky was studying the Coma Cluster, a group of galaxies about 320 million light-years away. He measured how fast those galaxies were moving and calculated how much mass would be needed to keep them gravitationally bound together. The problem? There wasn't nearly enough visible matter. The galaxies were moving too fast. They should have flown apart. But they didn't. Something invisible was holding them together with its gravitational pull.

Decades later, in the 1970s, astronomer Vera Rubin made similar observations about individual galaxies. She measured how fast stars orbited their galaxy's center and found the same problem: the rotation speeds didn't match what visible matter alone could produce. There had to be extra mass—invisible mass—surrounding these galaxies.

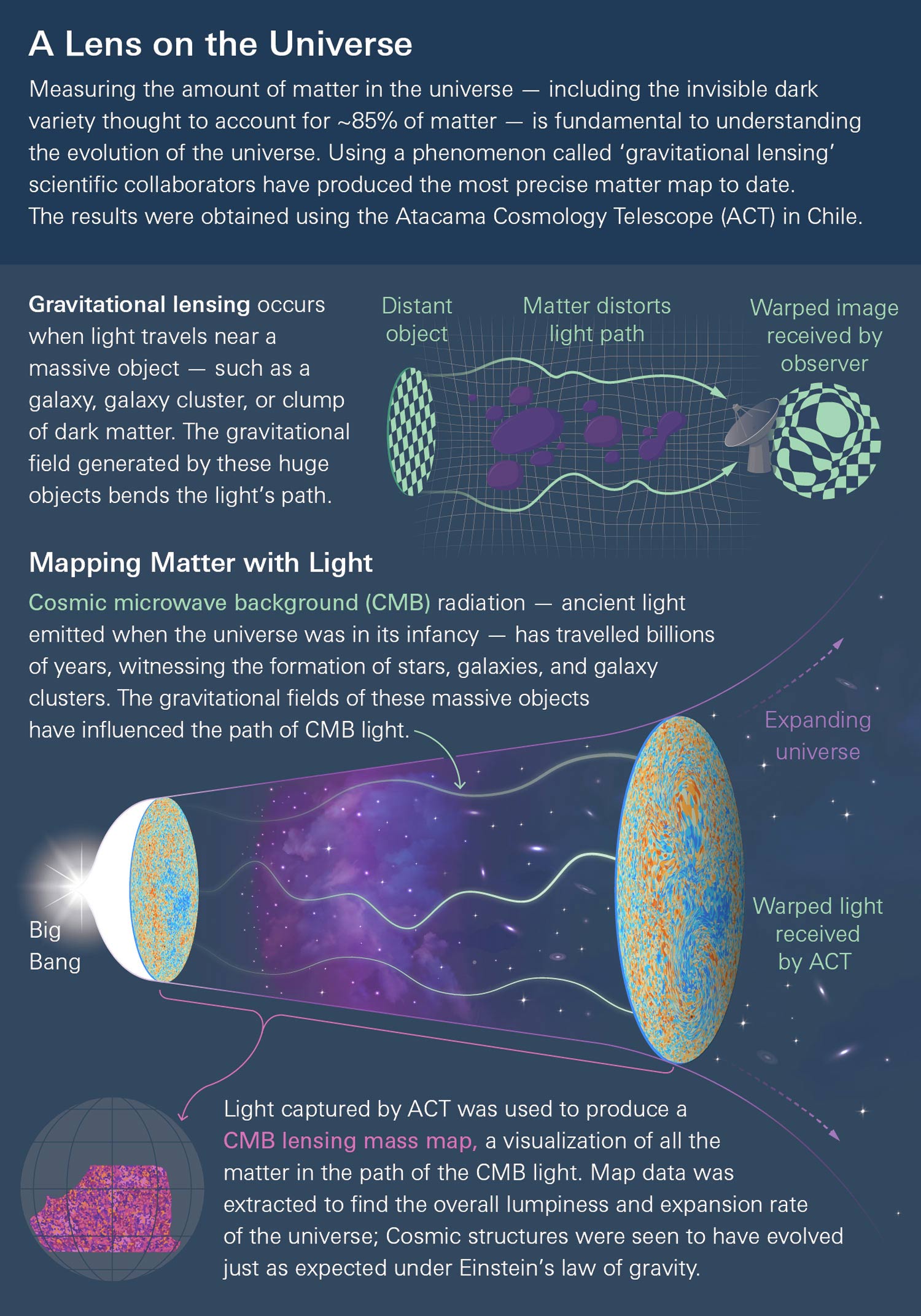

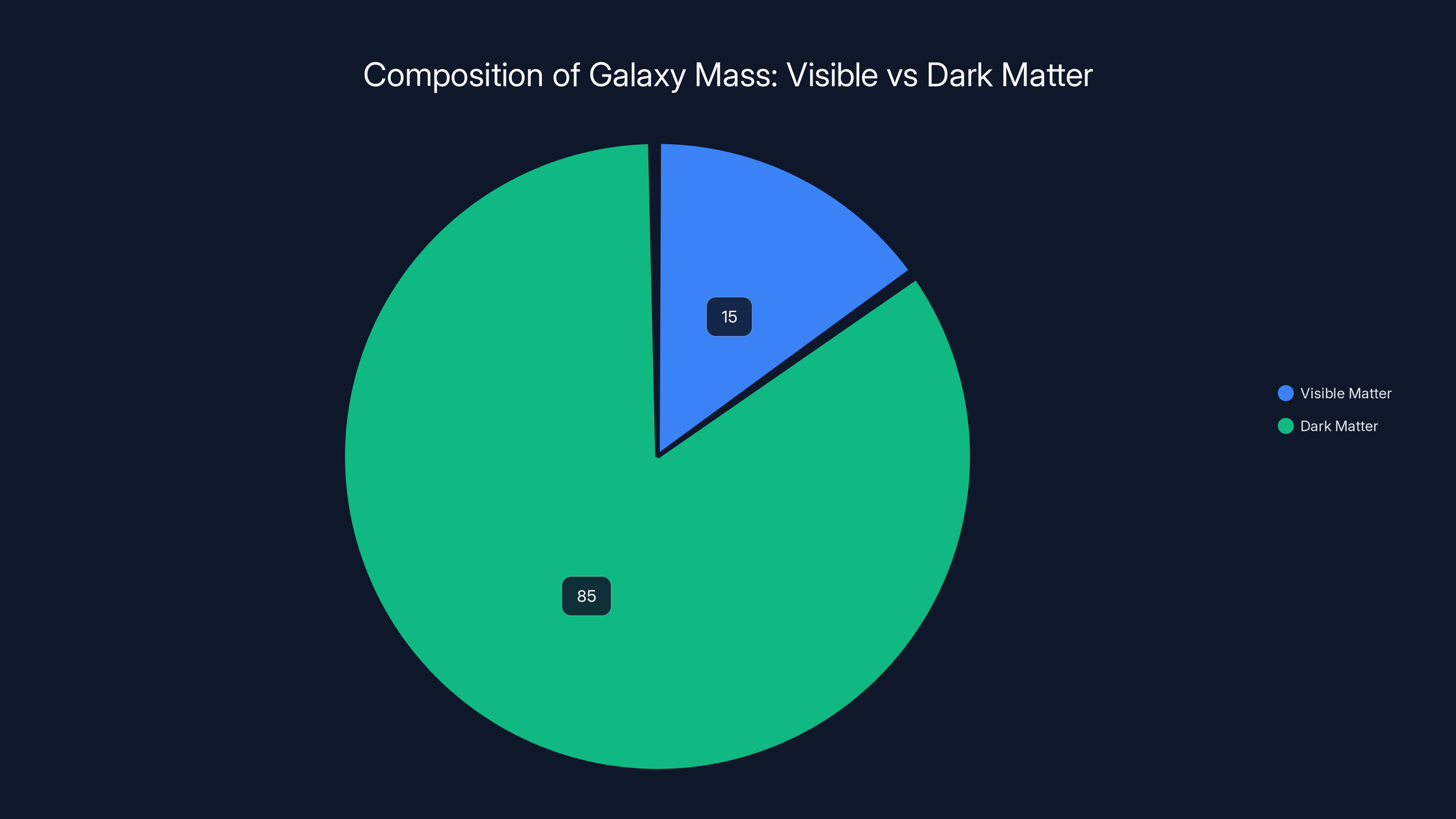

Today, we understand that dark matter isn't some fringe hypothesis. It's core to modern cosmology. Current estimates suggest dark matter comprises about 27 percent of the universe's total energy density. Among matter specifically (not counting dark energy), dark matter makes up roughly 85 percent. That means for every kilogram of regular atoms, there are about 5.7 kilograms of dark matter out there somewhere, as noted by NASA.

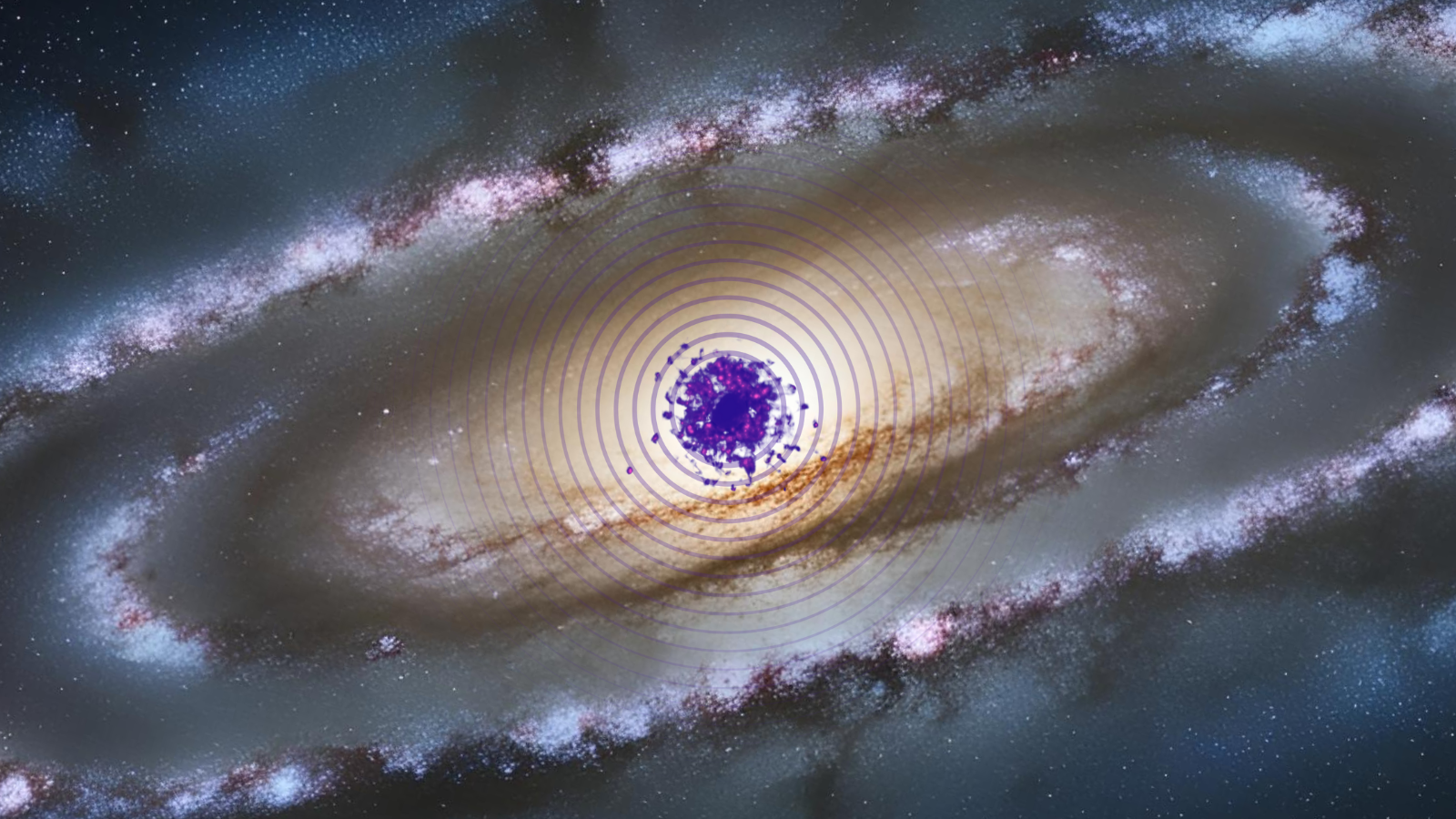

In galaxies like our Milky Way, dark matter forms massive halos that envelop the visible galactic disk. Models suggest our galaxy's dark matter halo contains roughly 90 percent of the galaxy's total mass. But even that's nothing compared to CDG-2.

What actually makes up dark matter remains one of astronomy's greatest unsolved mysteries. Scientists have proposed various candidates. Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) are theoretical particles that barely interact with normal matter except through gravity. Axions are hypothetical particles arising from theoretical physics that might help solve other particle physics problems. Some researchers even propose primordial black holes formed in the early universe. But none of these have been definitively proven, as discussed in The Conversation.

The beautiful thing about dark matter is that you don't need to know what it is to study how it behaves. Astronomers can observe its gravitational effects, map its distribution, and test how it influences galaxy formation. That's exactly what makes a system like CDG-2 so valuable.

The Perseus Cluster: Where CDG-2 Lives

CDG-2 isn't floating alone in space. It's part of the Perseus cluster, one of the nearest galaxy clusters to Earth, located approximately 250 million to 300 million light-years away depending on which measurement you use.

Perseus is a massive system containing over 1,000 galaxies bound together by gravity. At its heart sits Perseus A, a giant elliptical galaxy so large it would take light 300,000 years to travel from one side to the other. Around it swarm hundreds of smaller galaxies, from large spirals to tiny dwarf systems.

The Perseus cluster has fascinated astronomers for over a century. It's close enough to observe in reasonable detail but far enough away to contain diverse galaxy types. The cluster is rich with hot intergalactic gas, X-ray-emitting material, and supermassive black holes that actively feed on surrounding matter. It's a cosmic zoo, a place where different types of galaxies coexist and interact.

CDG-2 sits somewhere in this population, but it was essentially invisible. The four globular clusters that make it up were catalogued as separate objects. Globular clusters themselves are interesting: dense, spherical concentrations of hundreds of thousands of stars held together by gravity. They're among the oldest objects in galaxies, often dating back to a galaxy's formation era.

For years, these four clusters in the Perseus region seemed like isolated oddities—globular clusters that had somehow become separated from their home galaxies, wandering through intergalactic space. It wasn't an impossible scenario; it happens. But it was also uncommon enough to warrant investigation.

That's where modern telescopes changed everything.

CDG-2 is composed of 99.9% dark matter and only 0.1% visible matter, making it an extreme case compared to typical galaxies.

The Mystery of Four Orphaned Star Clusters

Let's back up and think about what astronomers actually observed before this recent discovery. They'd identified four globular clusters in the Perseus region. These clusters had properties that made them interesting: they appeared to be moving together, showing similar velocities relative to the rest of the cluster. But they seemed too far apart and too distinct to be part of a single system.

Here's the key detail: these four clusters contribute only about 16 percent of the total light from the system. That's an unusually large percentage. Most globular clusters within galaxies contribute a much smaller fraction of their galaxy's total brightness.

If these four clusters only account for 16 percent of the light, what's producing the other 84 percent?

Previously, astronomers assumed that light must be coming from scattered stars and diffuse material spread throughout the system. They figured maybe the four clusters were part of a larger structure, but the rest of that structure was just too dim to detect individually. It was like trying to see a black cat at night—you know something's there, but you can't quite make it out.

The question that drove recent research was straightforward: are these four clusters actually separate objects that happen to be moving together, or are they part of a single gravitationally bound system? If they're part of a single system, what's holding them together?

Answering that question required some of the most powerful tools humanity has ever built.

Three Telescopes Team Up to Reveal the Invisible

This is where the study gets interesting from a technical standpoint. The researchers didn't rely on a single observation. Instead, they combined data from three of the world's most advanced observatories: Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru.

The Hubble Space Telescope needs no introduction. Launched in 1990, it's been imaging the universe for over three decades. It observes in visible light and infrared, capturing stunning detail of distant objects. Hubble can resolve individual stars in globular clusters and can measure their movements with extreme precision.

Euclid is much newer, launched in 2023. It's specifically designed for dark matter studies, mapping the universe's geometry and using gravitational lensing to trace dark matter's distribution. Euclid observes a much wider area of sky than Hubble, though with less detail on individual objects.

Subaru is a Japanese telescope located in Hawaii that also provides wide-field observations. It's particularly good at detecting faint signals from distant galaxies.

When researchers combined observations from all three telescopes, something remarkable appeared that individual instruments had missed. There's an extremely faint glow around the four globular clusters. It's not bright enough to show up clearly in any single telescope's data, but when the signals are combined and analyzed carefully, it becomes apparent.

That faint glow is the light from the galaxy itself—light from stars and gas spread throughout the system but far too diffuse to see directly. It's the smoking gun proving that these four clusters are indeed part of one galaxy, as detailed by ESA Hubble.

The Birth of CDG-2: Candidate Dark Galaxy-2

Once researchers confirmed that the four clusters were part of a single system, the next step was characterizing that system. They needed to understand its properties, its mass, and what holds it together.

They named it CDG-2, which stands for "Candidate Dark Galaxy-2." The "candidate" part is important—it means this is the first confirmed example, but there may be others waiting to be discovered. The "-2" suggests at least one other candidate had been identified previously (CDG-1), though perhaps not confirmed as thoroughly.

The name itself is perfect because it captures what makes this galaxy so unusual: it's a dark galaxy, meaning it's dominated by dark matter to an extreme degree.

Using the combined telescope data, researchers could measure several key properties of CDG-2. First, its total luminosity—the total amount of light it emits. They calculated it at approximately 6 million solar luminosities. That sounds like a lot until you remember that our Milky Way has a luminosity around 10 billion solar luminosities. CDG-2 is roughly 1,600 times dimmer than our galaxy.

Second, they calculated the system's total mass using gravitational dynamics. By observing how the globular clusters move relative to each other, and using Newton's laws of gravity, astronomers can determine what mass would produce those observed motions. When they did those calculations, they got surprising results.

The total mass necessary to keep CDG-2 gravitationally bound is enormous—somewhere between 10 and 20 times more mass than would be required based on the visible light alone. Most of that additional mass had to be dark matter.

When the numbers were crunched, they came out to roughly 99.94 to 99.98 percent of the system's mass being dark matter. Different analysis methods gave slightly different percentages, but they all pointed to the same conclusion: this galaxy is almost entirely made of invisible matter, as noted by University of Oregon News.

To put that in perspective, our Milky Way's halo is approximately 90 percent dark matter. That's already a lot. But the Milky Way still has hundreds of billions of visible stars. CDG-2, by contrast, has almost no visible stars relative to its dark matter content.

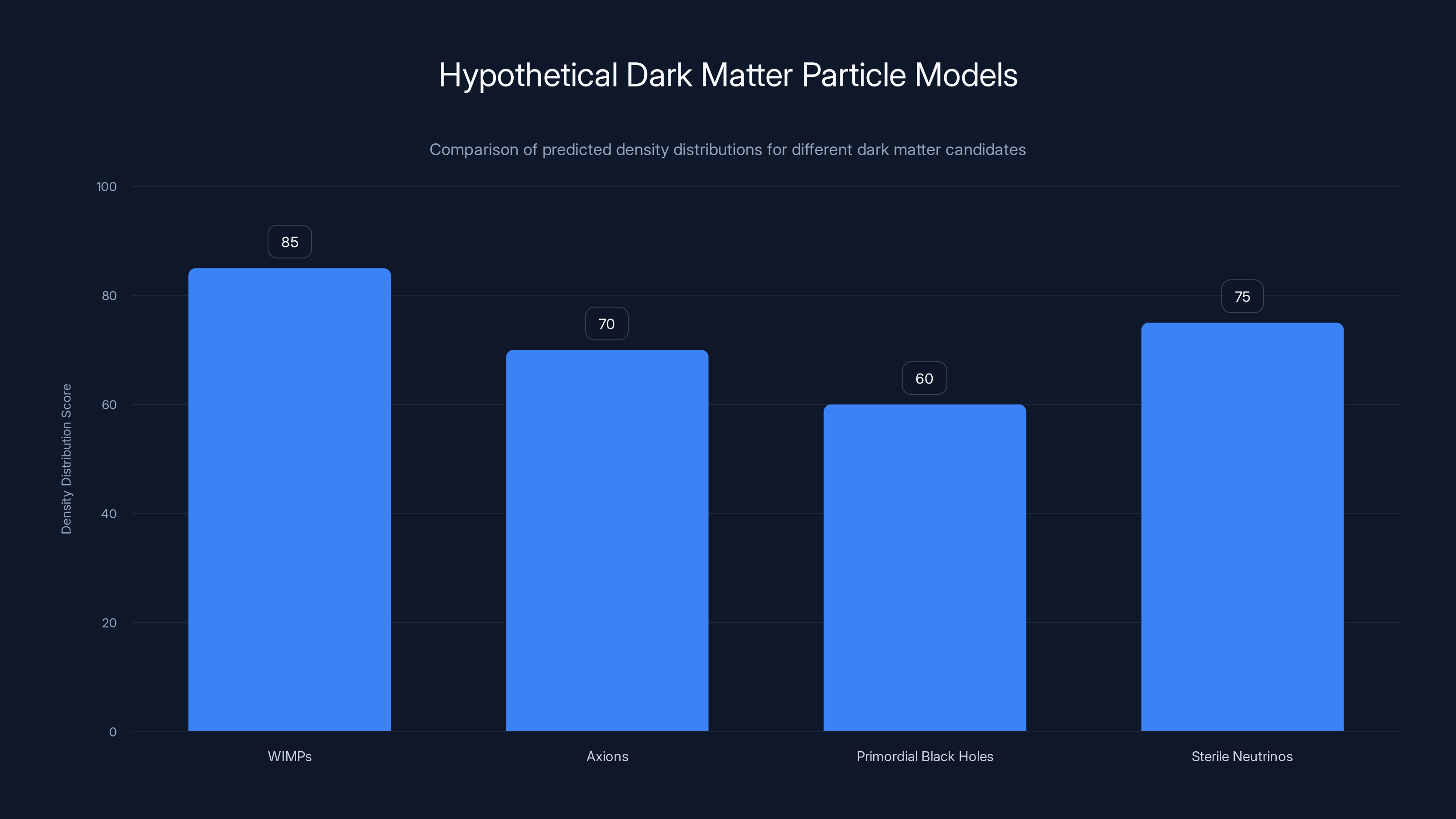

This chart compares the predicted density distributions of different hypothetical dark matter particles. WIMPs currently have the highest predicted density distribution score. Estimated data based on typical theoretical models.

Understanding the Composition: What Percentage Is What?

Let's break down the mass composition of CDG-2 more carefully, because the numbers here are genuinely mind-bending.

Say CDG-2's total mass is 100 units. Here's how that breaks down:

- Dark matter: 99.94 to 99.98 units (the invisible stuff)

- Visible matter: 0.02 to 0.06 units (the stuff that makes light)

Now, that 0.02 to 0.06 units of visible matter breaks down further:

- Stars (in globular clusters): Roughly half of the visible matter

- Intergalactic gas and dust: The other half

So while dark matter comprises 99.9+ percent of the galaxy, among the regular matter that does exist, we can actually see most of it. The four globular clusters contain lots of stars packed into relatively small regions of space, making them bright enough to detect. But they only represent a tiny fraction of the galaxy's overall mass.

This is distinctly different from a normal galaxy. In the Milky Way, visible stars make up maybe 0.1 to 1 percent of the galaxy's mass (depending on how you count). Dark matter dominates, sure, but not this extremely. There's usually more of a balance, with visible matter being at least somewhat significant.

CDG-2 is extreme. It's like a galaxy with almost no visible component at all, just a dark matter halo with a few stars scattered in it.

Why would a galaxy develop this way? That's still an open question. Current galaxy formation models suggest that galaxies form when dark matter halos collapse under their own gravity, and gas falls into those halos, eventually forming stars. Most galaxies seem to follow a pattern where some reasonable fraction of the dark matter halo's mass ends up converted into stars and visible matter.

But CDG-2 breaks that pattern. Either very little gas ever fell into this dark matter halo, or very little of that gas ever formed stars, or both. Maybe this system experienced some event that prevented normal star formation. Maybe it's just a genuinely rare outlier. Both scenarios are possible, and both would be scientifically interesting.

How Astronomy Measures Dark Matter Without Seeing It

Before moving forward, it's worth understanding exactly how astronomers determine that dark matter exists and measure how much is present. It's actually elegant.

The fundamental method relies on orbital mechanics—the same physics that keeps satellites in orbit around Earth. When an object orbits another object, the orbital speed depends on two things: the distance from the central mass and the amount of mass being orbited.

Mathematically, this is expressed through Kepler's Third Law, which relates orbital period to orbital radius and central mass. Rearrange the equation, and you can solve for mass:

Where M is the mass, a is the orbital distance, T is the orbital period, and G is the gravitational constant.

Now here's the key: you can observe both a and T directly. You can watch stars orbiting a galaxy's center and measure their orbital period by observing them over time. You can measure their distance using parallax and other techniques. Plug those numbers into the equation, and out comes the total mass required to produce those orbits.

But when you add up all the visible stars, gas, and dust, it never matches. The galaxy is too dark to account for the orbital speeds. Therefore, there must be additional matter that you can't see.

For CDG-2 specifically, researchers used a similar technique with the globular clusters. Each cluster contains hundreds of thousands of stars. By measuring how fast individual stars move within each cluster, you can determine that cluster's total mass. By measuring how fast the clusters move relative to each other, you can determine the mass of the entire system.

Then you compare that required mass to the visible light, and the discrepancy tells you how much dark matter is present.

It's indirect, but it's rigorous. And it's how we know dark matter is real.

Why Dark Galaxies Matter for Cosmology

You might be wondering: why does this one weird galaxy matter? Why should anyone care about CDG-2?

The answer gets at fundamental questions about how the universe works.

Galaxy formation theory is built on computational models. Astrophysicists write code that simulates how matter clumps together, how gravity works on large scales, how dark matter and visible matter interact. These simulations start with conditions similar to the early universe and let them evolve forward, trying to reproduce the universe we see today.

Generally, these simulations work pretty well. They can reproduce the large-scale structure of the universe. They can explain why galaxies are distributed the way they are. They predict certain properties of galaxies that observations confirm.

But there are puzzles. The simulations sometimes predict too many large galaxies or too few small galaxies. They have trouble reproducing the exact properties of galaxy clusters. And they struggle to explain extreme cases like CDG-2.

Each time astronomers find a galaxy that doesn't fit the models—a galaxy that's smaller than expected, or brighter, or has an unusual structure—it's a clue that the models need refinement. CDG-2 is a particularly good clue because it's so extreme.

If CDG-2 isn't unique, if dark galaxies like this are actually common, then that changes everything. It means the universe contains far more galaxies than we've ever realized. Most of them would be nearly invisible, detectable only by their gravitational effects or through careful combined analysis of multiple telescopes.

Current estimates suggest we've catalogued roughly 200 billion galaxies in the observable universe. But that's just the ones we can see. If dark galaxies are common, the true number could be orders of magnitude higher. The universe is vastly more populous than we thought, as noted by NASA.

That has practical implications too. It changes how we calculate the total mass of the universe, the distribution of matter and energy, and the large-scale structure of the cosmos. These are the numbers that feed into models of cosmic expansion, the Big Bang, and the ultimate fate of the universe.

So CDG-2 isn't just a curiosity. It's a piece of a much larger puzzle.

In a typical galaxy, dark matter constitutes approximately 85% of the total mass, while visible matter accounts for only about 15%. This discrepancy is determined through indirect measurements such as orbital mechanics and gravitational lensing. Estimated data.

The Observational Challenges: Why This Was Hard to Detect

Before the recent confirmation, nobody had definitively identified a galaxy as dominated by dark matter to this extreme. Why? Because it's incredibly difficult to observe.

Think about the challenge from a practical standpoint. You're trying to detect an object that emits almost no light. Your telescopes can see a galaxy like the Milky Way, which has hundreds of billions of stars. But CDG-2 only has a few million stars, distributed across an enormous volume of space.

Further, those stars are concentrated in four globular clusters. Each cluster is relatively bright (globular clusters are dense and therefore luminous), but they're separated from each other. So when you look at the sky, you see four bright spots. It's natural to think: those are four separate objects.

The faint glow connecting them? It's so dim that a single telescope can't reliably detect it above background noise. The telescope picks up light from distant galaxies behind CDG-2, light from distant stars, cosmic background radiation scattered by dust in the Milky Way. Against all that noise, the faint signal from CDG-2 becomes nearly impossible to isolate.

That's why the combination of three telescopes was necessary. Each one observed the same region independently. Each one picked up a faint signal consistent with a galaxy, but none could confirm it definitively. Combined, with careful analysis, the signal becomes unmistakable.

This is actually an important lesson in modern astronomy: the most interesting objects aren't always the brightest. Sometimes they're the faintest, hiding in plain sight, waiting for better instruments or cleverer analysis techniques to reveal them.

It also explains why dark galaxies hadn't been detected before. The technology simply wasn't there. Hubble launched in 1990 and has been continuously upgraded, but older versions couldn't have detected something this faint. Euclid is brand new, launched in 2023, specifically designed for this kind of dark matter research.

We're living in the era where these observations are finally possible. The next few years should bring many more discoveries of dark galaxies, ultra-faint galaxies, and other cosmic oddities that previous generations of astronomers could only theorize about.

What This Means for Dark Matter Research

CDG-2 fundamentally changes the dark matter research landscape. Here's why.

Dark matter research has historically worked backward. Scientists know dark matter exists because of its gravitational effects, but they've never directly detected a dark matter particle in a laboratory. Physicists have built increasingly sensitive detectors, buried deep underground to shield them from cosmic rays, all searching for dark matter passing through the Earth. So far, nothing definitive has been found.

That's frustrating. It's like knowing someone broke into your house because things are missing, but you never see the intruder.

Astronomers have taken a different approach. They study dark matter's behavior on cosmic scales, measuring how it's distributed around galaxies, how it shapes the universe's large-scale structure, and what properties those distributions suggest about dark matter's nature.

CDG-2 is a gift for this kind of research. It's a system where dark matter completely dominates. Any models or theories about dark matter's properties can be tested against CDG-2's characteristics. If a dark matter model predicts a certain density profile for dark matter halos, you can check whether CDG-2 matches that prediction.

Further, CDG-2 might help constrain what dark matter actually is. Different types of hypothetical dark matter particles would behave differently. WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles) would create certain density distributions. Axions might create different ones. Primordial black holes would create yet others. By studying enough real-world examples like CDG-2, astronomers can gradually narrow down which candidates are consistent with observations, as noted by Big Think.

It's slow work. Building a robust understanding of dark matter from astronomical observations takes time, lots of data, and many different types of systems to study. But every discovery like CDG-2 brings us closer.

Globular Clusters: The Visible Markers

Let's talk more specifically about the four globular clusters that make CDG-2 visible. These aren't random stars scattered in space. They're distinct, organized structures, each containing hundreds of thousands of stars packed into a region a few dozen light-years across.

Globular clusters are among the oldest structures in galaxies. Many of the globular clusters in the Milky Way formed when the galaxy itself was forming, over 13 billion years ago. They're gravitationally bound systems where stars are packed so densely that their density near the clusters' centers rivals stellar densities in nearby space around the Sun.

The stars in globular clusters are typically old and metal-poor (meaning they contain few heavy elements). This tells us they formed early in cosmic history, before galaxies had time to build up heavy elements through stellar processing.

In normal galaxies like the Milky Way, globular clusters are distributed throughout the galactic halo. Our galaxy has roughly 150 to 200 known globular clusters. They're a minority component of the galaxy by mass, but they're famous for being beautiful objects through telescopes. Any reasonably powerful telescope can resolve individual stars in a globular cluster.

In CDG-2, we have four globular clusters. That's not an unusually large number. But their relationship to the rest of the system is unusual. In a normal galaxy, globular clusters are embedded in a much larger galaxy full of stars and gas. In CDG-2, the globular clusters are basically the only visible structure. Everything else is dark matter.

This raises an interesting question: how did CDG-2 end up with these globular clusters but few other visible structures? Did it form as a galaxy with globular clusters but almost no disk or bulge? Or did something strip away most of its visible matter, leaving only the dense globular clusters behind?

It's possible that CDG-2 had a close encounter with a larger galaxy, and gravitational interactions tore away much of its visible matter while leaving the dense globular clusters intact. Globular clusters would survive such an encounter better than diffuse disk structures because they're so tightly bound.

Alternatively, maybe CDG-2 formed in an environment where very little gas was available to form additional stars beyond those in the globular clusters. The dark matter halo accumulated normally, but the visible matter never coalesced into additional stars.

Both scenarios are plausible. Distinguishing between them would require more detailed study of CDG-2's structure and history.

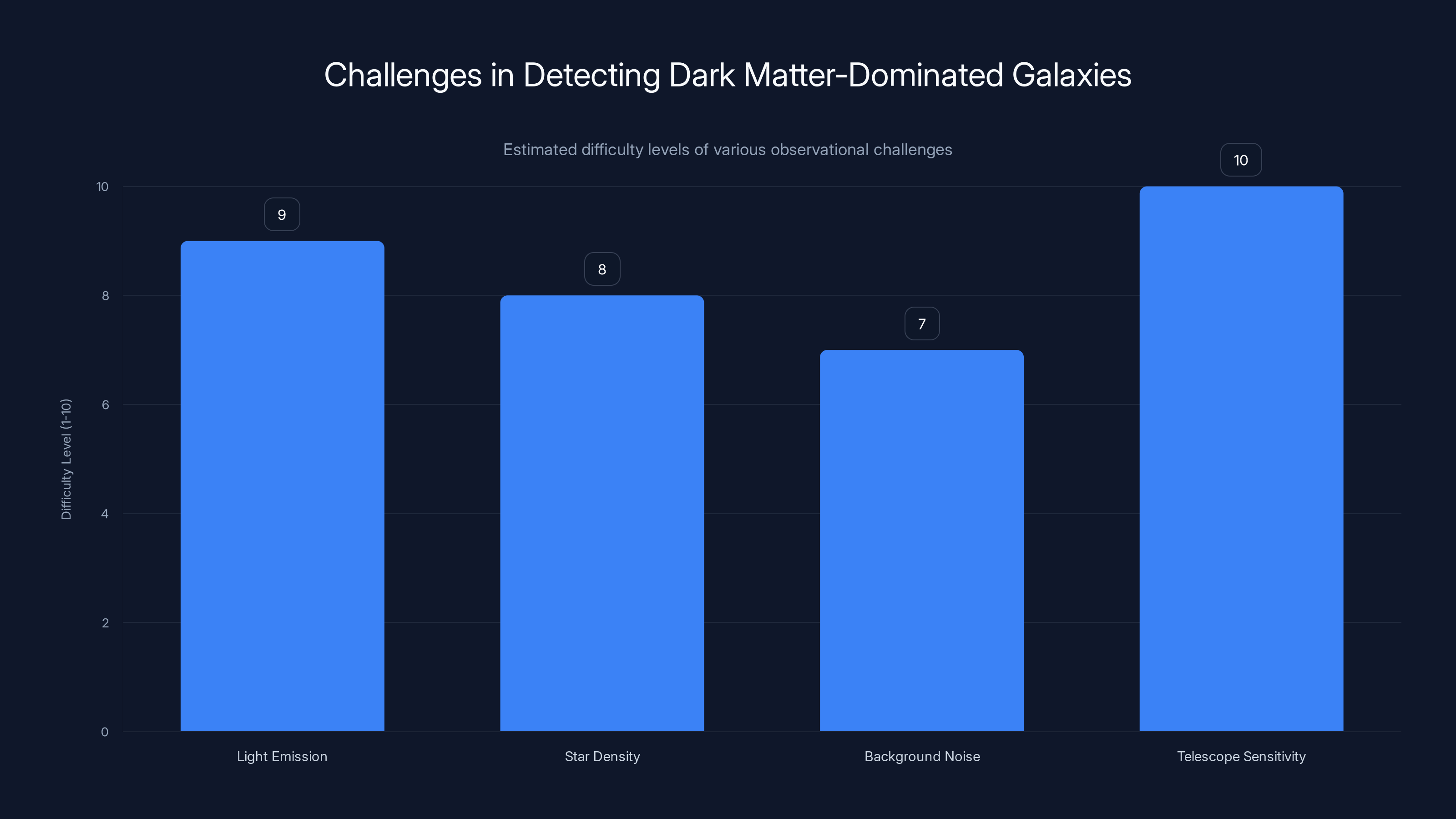

Detecting dark matter-dominated galaxies is challenging due to low light emission, sparse star density, high background noise, and the need for sensitive telescopes. Estimated data.

The Four Clusters: Numbers and Distribution

While detailed catalogues of the four clusters exist in astronomical literature, the key facts for our purposes are straightforward: they're relatively bright (by CDG-2 standards), they show consistent motions relative to the broader universe, and they're separated by tens of thousands of light-years.

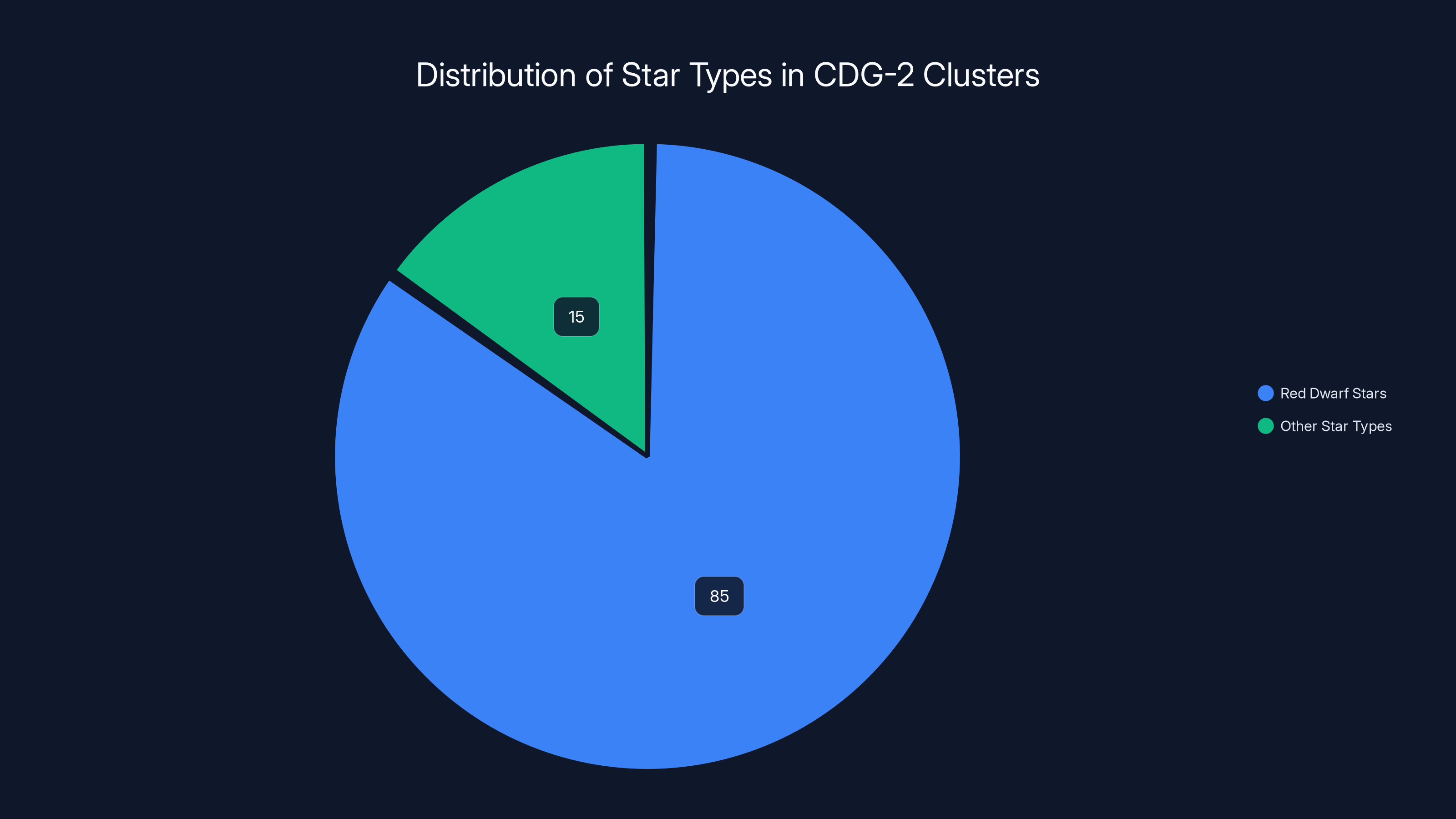

Their combined light output—about 6 million solar luminosities—is spread among maybe billions or tens of billions of stars. That means the average star in CDG-2 is much dimmer than a typical star in our galaxy. The clusters contain mostly old, low-mass red dwarf stars rather than young, massive, bright blue stars.

Those four clusters are essentially windows into CDG-2. They're the parts we can see. They're what allowed us to detect the galaxy at all. Without them, CDG-2 would be completely unobservable. It would be just another patch of space showing no stars, no light, just the subtle gravitational influence of a massive dark matter halo on the motions of other objects.

That's actually how astronomers expect to find other dark galaxies in the future. They'll look for subtle signatures: small groups of globular clusters, or stars, that show unusual motions compared to the background. Those unusual motions suggest an unseen massive structure. Then they'll combine observations from multiple telescopes to find the faint glow of the underlying galaxy.

Implications for Galaxy Formation Models

CDG-2 challenges conventional galaxy formation models in several important ways.

Current models start with the principle that galaxies form within dark matter halos. Gas falls into these halos, cools, and fragments, forming stars. As stars form, they release energy through supernovae and radiation, heating the surrounding gas and preventing too many more stars from forming. The result is that a certain fraction of the gas in the halo ends up as stars, and the rest disperses or remains in the galactic halo.

For large galaxies like the Milky Way, this fraction is roughly 10 to 20 percent. For small dwarf galaxies, it's typically much smaller, sometimes under 1 percent. But even for the smallest galaxies we know, it's usually at least a few tenths of a percent.

CDG-2, with its 0.02 to 0.06 percent visible matter fraction, is an extreme outlier. Either the standard model is missing something important about how galaxies form, or CDG-2 is the result of very unusual circumstances.

One possibility is that CDG-2 is a "failed galaxy"—a system where dark matter collapse occurred normally, but the conditions for star formation never developed. Maybe there was never enough cooling in the dark matter halo, so gas remained hot and diffuse, never condensing into stars. Maybe the environment was simply too hostile, with intergalactic radiation preventing gas from cooling effectively.

Another possibility is tidal disruption. Perhaps CDG-2 formed normally but then encountered a large galaxy or galaxy cluster. Gravitational interactions could have stripped away most of its visible matter, leaving only the tightly bound globular clusters and the dark matter halo.

A third possibility is that we're misinterpreting the data somehow. Maybe there's additional visible matter we're not detecting, or maybe some of the mass we're attributing to dark matter is actually something else. This seems less likely given the careful analysis, but it's always worth considering.

Whatever the explanation, CDG-2 tells us that the range of galaxy types is wider than we previously recognized. The universe is more diverse than our models predict, which is humbling and exciting in equal measure.

How Technology Enabled This Discovery

This discovery was only possible because of recent technological advances. A decade ago, it would have been impossible. Two decades ago, unthinkable.

The Hubble Space Telescope has been imaging galaxies since 1990, but its sensitivity and resolution have improved dramatically over time through repairs and upgrades. The Advanced Camera for Surveys, installed in 2002 and upgraded in 2009, gave Hubble unprecedented ability to detect faint objects.

But Hubble alone couldn't do this. Its field of view is relatively small. It can see fine details in a small region of sky, but it can't see the big picture.

Euclid, launched in July 2023, represents a quantum leap in dark matter observation capability. It's specifically designed to map dark matter's distribution across the universe using weak gravitational lensing. It can survey enormous regions of sky, looking for the subtle distortions that dark matter causes in the light from distant galaxies.

Euclid has already begun sending back data, and the discoveries are coming fast. It's detected hundreds of millions of galaxies in its early observations, and it's designed to operate for at least six years, possibly longer.

Subaru, the Japanese telescope in Hawaii, has been operating since 1999 and provides complementary observations. Its wide field of view and sensitivity to faint objects make it ideal for confirming discoveries made by other telescopes.

Combining data from these three instruments required sophisticated data analysis techniques. The researchers had to account for variations in how each telescope measures the same object, correct for atmospheric effects, and apply statistical methods to extract the faint signal from CDG-2 from the background noise.

This kind of combined analysis is becoming increasingly common in astronomy. The days of major discoveries depending on a single observation from a single telescope are largely over. Modern astronomy is about combining multiple datasets, each imperfect in its own way, to construct a clearer picture of reality.

It's also computationally intensive. The data processing, statistical analysis, and modeling required to analyze CDG-2 required substantial computational resources. Twenty years ago, these calculations would have been impractical. Today, they're routine.

The CDG-2 clusters are predominantly composed of old, low-mass red dwarf stars, which make up approximately 85% of the star population. Estimated data.

What Makes CDG-2 Different From Other Extreme Galaxies

CDG-2 isn't the first galaxy to surprise astronomers with an extreme dark matter fraction. So what makes it special?

Ultra-diffuse galaxies (UDGs) have been known for years. These are galaxies as large as the Milky Way but with far fewer stars, spread out across a much larger area. Some UDGs have dark matter fractions comparable to CDG-2.

But here's the key difference: UDGs still contain millions or billions of stars. You can see individual stars in them (though not easily). CDG-2 contains only a few million stars, essentially all packed into four globular clusters. The contrast between that small number of visible stars and the enormous dark matter halo is more extreme.

Another difference is confirmation. Some UDGs have been proposed, studied, and debated. There's disagreement about their true properties, their formation history, whether they're actually as extreme as they appear. CDG-2 has been carefully studied using three independent telescopes with clear methodology. The confirmation is solid.

CDG-2 is also notable for being detected primarily through its faint diffuse light rather than through other signatures. Some galaxies are primarily detected through radio emissions, or X-ray emissions, or gravitational lensing. CDG-2 was detected through direct observation of visible light, the most straightforward (though hardest in this case) detection method.

In some ways, CDG-2 represents a new category of galaxy: dark galaxies detected directly through their integrated light rather than inferred from other signatures. If this detection method becomes practical, it could open up a whole new population of observable galaxies.

The Perseus Cluster Context: Why Study It?

The Perseus cluster is one of the most studied galaxy clusters in the universe, and for good reasons. It's relatively nearby, so we can see fine detail. It's massive and rich with structures. And it's host to interesting phenomena, including active galactic nuclei, jets, and complex interactions between galaxies.

CDG-2's discovery in Perseus isn't random. The Perseus cluster has been intensively observed because it's scientifically interesting. That's where astronomers found it. But it raises the question: if a dark galaxy is hiding in one of the most studied regions of the sky, how many more are out there in less-studied regions?

Perseus also provides a useful laboratory for studying galaxy interactions and environmental effects. The cluster's dense environment might explain some of CDG-2's properties. For instance, the tidal forces in a cluster could have stripped away visible matter from CDG-2 while preserving the dark matter halo.

As astronomy surveys become more comprehensive and sensitive, we'll probably find similar systems in many clusters. The rate of discovery will likely accelerate over the next few years as new instruments come online and existing data is analyzed more deeply.

Future Searches for Dark Galaxies

Now that one dark galaxy has been confirmed, astronomers are looking for more. There are several strategies.

The first is analyzing existing data more carefully. Hubble, Euclid, and other telescopes have already imaged vast regions of sky. Much of that data has been analyzed, but new analysis techniques might reveal faint galaxies that previous analysis missed. As deep learning and artificial intelligence improve, automated systems might spot patterns that human analysts overlooked.

The second is conducting targeted surveys specifically designed to find dark galaxies. The Vera Rubin Observatory (LSST), under construction in Chile, will conduct the most comprehensive survey of the southern sky ever attempted. It will image billions of objects repeatedly over a decade, tracking their movements and detecting changes. This data will be ideal for finding dark galaxies through their subtle gravitational effects on surrounding material.

The third is using gravitational lensing more systematically. Dark matter concentrations, even those without visible galaxies, will bend light from distant background galaxies. By carefully analyzing the distortions in background galaxies, astronomers can map dark matter distributions and potentially locate dark galaxies that are otherwise invisible.

The fourth is looking for kinematic signatures. Groups of globular clusters or stars showing unusual motions together suggest an underlying dark matter structure. Detailed spectroscopy—measuring the velocities of individual stars—can reveal these patterns even in systems that are otherwise hard to observe.

Each approach has advantages and limitations. The most comprehensive dark matter census will probably use all of them in combination.

Theoretical Implications: What Dark Matter Is

CDG-2 doesn't directly tell us what dark matter is made of, but it does provide constraints on dark matter models.

Consider WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles). These are hypothetical particles that interact with normal matter primarily through gravity, leaving no electromagnetic signature. Various theoretical models propose WIMPs with different properties—different masses, different interaction strengths, different interaction types.

If dark matter is actually made of WIMPs, then CDG-2 should show certain properties. Its dark matter density profile should match predictions from particle physics and N-body simulations. Its internal structure should reflect how WIMPs would be distributed under gravity. By measuring CDG-2's properties carefully and comparing to WIMP predictions, astronomers can test whether WIMP models work.

Similarly for axions, primordial black holes, and other candidates. Each would leave different signatures in a dark galaxy's structure and properties.

CDG-2 is one data point. It's not enough to definitively identify dark matter's nature. But as more dark galaxies are discovered and characterized, the ensemble of observations will constrain dark matter models more and more tightly. Eventually, real laboratory detection or astronomical observations will narrow it down to the actual composition.

One interesting note: the existence of CDG-2 might actually favor certain dark matter models over others. Some models predict that dark matter should clump more readily into pure dark matter structures without significant visible matter. Other models predict that dark and visible matter should always be mixed together. CDG-2 suggests that purely dark matter structures can exist, favoring the first class of models.

But we need more observations to be sure.

The Broader Implications: A Universe We're Just Beginning to See

CDG-2 represents something profound: a recognition that the universe is stranger and more populated than we've realized.

For decades, our understanding of the universe was limited by what we could see with our eyes and telescopes. We counted galaxies, measured their properties, and built models. But all along, we were only seeing the tip of the iceberg.

We were blind to dark matter, seeing only its gravitational shadows. We were missing entire galaxies that contain too little visible matter to be easily detected. We were building a census of the universe based on an incomplete inventory.

Technological advances have changed that. Better telescopes, more sensitive detectors, and more sophisticated analysis techniques are revealing the hidden universe. CDG-2 is just the beginning.

In the coming years, we'll probably discover thousands of dark galaxies. We'll map out the distribution of dark matter with unprecedented detail. We'll understand galaxy formation at deeper levels. And our models of the universe will shift again, as they have repeatedly in the history of science.

This is exciting not because we've solved the dark matter problem, but because we've opened a new window into understanding it. We've proven that dark matter-dominated galaxies exist and can be studied. We've shown that the universe contains classes of objects we hadn't effectively observed before.

That's the essence of scientific progress: recognizing what you don't know, developing tools to explore it, and being prepared to be surprised by what you find.

CDG-2 surprised us. And there's certainly more surprises coming.

Conclusion: Standing at the Edge of Discovery

When astronomers first noticed those four globular clusters in the Perseus cluster, they probably didn't suspect they were looking at one of the most unusual galaxy systems in the universe. Four isolated star clusters is interesting, but not revolutionary. But follow-up observations, combined data from multiple telescopes, and careful analysis revealed something extraordinary.

CDG-2 is a galaxy so dominated by dark matter that it's barely visible. Ninety-nine point nine percent of its mass is dark. It's a cosmic oddity, a system that breaks our conventional understanding of how galaxies form and evolve.

But maybe it's not actually that odd. Maybe the universe is full of similar systems, and we've just never had the tools to see them before. Maybe the visible, light-emitting galaxies we've been cataloguing are the exceptions rather than the rule. Maybe the universe is far more populated with invisible galaxies than with visible ones.

That fundamental shift in perspective is CDG-2's real contribution. It forces us to acknowledge what we don't know, to recognize the limitations of previous observations, and to prepare for a more complex understanding of cosmic structure.

The discovery also illustrates the power of modern astronomy. No single telescope could have done this. It took combining data from three world-class observatories, applying sophisticated analysis techniques, and careful statistical reasoning. This is what cutting-edge astronomy looks like in the 2020s.

As new instruments like the Vera Rubin Observatory and improved data from Euclid come online, we'll find more dark galaxies. We'll measure their properties more precisely. We'll develop better models of how they form. And we'll gradually build up a more complete picture of the universe—one that includes not just the visible 0.1 percent but the invisible 99.9 percent that actually dominates cosmic structure.

CDG-2 is where that journey begins. It's the first confirmed dark galaxy, and countless others are waiting to be discovered. The invisible universe is revealing itself, and it's beautiful.

FAQ

What exactly is CDG-2?

CDG-2 (Candidate Dark Galaxy-2) is a galaxy located approximately 300 million light-years away in the Perseus cluster. It's composed of approximately 99.9 percent dark matter with only about 0.1 percent visible ordinary matter. The galaxy was discovered by identifying four globular star clusters that were initially thought to be separate objects but are actually part of a single gravitationally bound system.

How did astronomers confirm CDG-2 is a single galaxy?

Astronomers used combined observations from three major telescopes: Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru. While individual telescopes couldn't detect the faint diffuse light surrounding the four globular clusters, combining data from all three revealed an extremely faint glow connecting them. This residual light proved the clusters were part of a single large galaxy rather than isolated objects.

What are globular clusters and why are they important to CDG-2?

Globular clusters are dense, spherical concentrations of hundreds of thousands of stars held together by gravity. In CDG-2, the four globular clusters are the only visible structures, containing virtually all the galaxy's detectable light. Without these visible markers, CDG-2 would be completely unobservable, making globular clusters essential to the discovery.

Why is a galaxy being 99.9 percent dark matter so unusual?

Typical galaxies like the Milky Way contain roughly 10 to 20 percent of their mass in visible matter, with the rest being dark matter. Even small dwarf galaxies usually have at least several tenths of a percent visible matter. CDG-2's 0.1 percent visible matter fraction is extreme, making it fundamentally different from any previously well-documented galaxy system.

What does CDG-2 reveal about dark matter?

CDG-2 serves as a natural laboratory for studying dark matter because it's dominated by dark matter to such an extreme degree. The galaxy's properties can be tested against different dark matter models, helping constrain what dark matter might actually be made of. It also suggests that dark matter-dominated galaxies can exist and be studied, opening new research directions.

Could there be many more dark galaxies out there?

Yes, very likely. If dark galaxies like CDG-2 are common but we've only just developed the tools to detect them, the universe might contain far more galaxies than current catalogues suggest. Some estimates propose there could be 10 times as many total galaxies once we account for faint and dark systems. Future surveys with instruments like the Vera Rubin Observatory will probably discover thousands of similar systems.

How did CDG-2 end up with so little visible matter?

That remains an open question. Possible explanations include: the system formed in an environment with insufficient gas to form many stars, or gravitational interactions with larger galaxies stripped away most visible matter while leaving the dense dark matter halo and robust globular clusters intact. Different observation studies may eventually clarify which scenario explains CDG-2.

Why does dark matter matter for understanding the universe?

Dark matter comprises roughly 85 percent of all matter in the universe and about 27 percent of the universe's total energy density. Understanding its nature, distribution, and behavior is essential for understanding how galaxies form, how the universe's large-scale structure developed, and what the universe's ultimate fate will be. CDG-2 provides crucial insights into dark matter's role.

TL; DR Summary

Astronomers have confirmed the existence of CDG-2, a galaxy composed of approximately 99.9 percent dark matter—the most extreme case yet observed. What appeared to be four separate globular star clusters were actually part of a single enormous dark matter-dominated galaxy detected only through combined observations from Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru telescopes. This discovery challenges galaxy formation models, suggests the universe contains far more galaxies than previously catalogued, and provides a natural laboratory for studying dark matter's properties and behavior. Future surveys will likely reveal thousands of similar dark galaxies, fundamentally changing our understanding of cosmic structure.

Key Takeaways

- CDG-2 is composed of 99.9% dark matter—the most extreme dark matter-dominated galaxy yet confirmed, with only 0.1% visible ordinary matter

- Four globular clusters initially catalogued as separate objects were revealed through combined Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru telescope observations to be part of a single galaxy

- The discovery suggests the universe contains far more galaxies than currently catalogued, potentially thousands of nearly invisible dark galaxies waiting to be discovered

- Dark matter comprises 85% of all matter in the universe, and CDG-2 provides an unprecedented natural laboratory for testing dark matter models and understanding cosmic structure

- Modern astronomy increasingly relies on combining multi-telescope observations and sophisticated analysis techniques rather than single-instrument discoveries, as demonstrated by CDG-2's confirmation

Related Articles

- NASA SpaceX Crew-12 ISS Docking: Complete Mission Guide [2025]

- SpaceX Super Heavy Booster Cryoproof Testing Explained [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- NASA Crew-12 Mission to ISS: Everything About February 11 Launch [2025]

- NASA's Fraggle Rock Space Adventure: Muppets Meet Moon Exploration [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

![Dark Matter Galaxy CDG-2 Confirmed: How Scientists Found the Universe's Most Invisible System [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dark-matter-galaxy-cdg-2-confirmed-how-scientists-found-the-/image-1-1771632459793.jpg)