Introduction: When Phone Design Actually Took a Risk

There's a moment in tech history when everyone stops playing it safe. The LG Wing was that moment for smartphones. While Samsung was perfecting the traditional fold and Apple was releasing incremental updates, LG looked at the entire category and asked: what if we rotated the screen?

This wasn't just another gimmick. The LG Wing represented something rare in 2020: genuine innovation in a space that had become predictable. Most people never got to hold one. That's the real tragedy. This device existed for roughly 18 months before LG quietly discontinued it, leaving behind a masterclass in engineering that the industry largely ignored.

I'll be honest—I never tested the Wing when it was available. Watching reviews and specs online doesn't do it justice. But talking to people who actually owned one? They unanimously said the same thing: once you used it, you couldn't go back. The innovative two-screen setup wasn't just different for different's sake. It fundamentally changed how you interacted with your phone.

The smartphone market had stagnated by 2020. Every flagship looked like the last one. Cameras got better. Processors got faster. But the form factor? The actual shape and interaction model? Frozen. Samsung's fold was clever but still a traditional phone format. Apple's iPhone was iterating on a design from 2014. Then LG came along and said: what if the screen rotated 90 degrees?

That's what made the Wing remarkable. Not that it was perfect. Not that it solved every problem. But because it represented a willingness to fail spectacularly in the name of trying something genuinely different. In an industry obsessed with "safe innovation," the Wing was radical. And the world mostly missed it.

This deep dive explores why the LG Wing mattered, how its rotating display actually worked, what made it unique compared to foldables, and why its discontinuation represented a missed opportunity for the entire smartphone category. If you care about innovation—real, messy, ambitious innovation—this is the phone that deserved your attention.

TL; DR

- Revolutionary Design: The LG Wing featured a unique rotating display (Main screen 6.8" OLED rotates horizontally) that created a dual-screen experience unlike any competitor

- Dual-Purpose Functionality: The rotation unlocked T-shaped configurations perfect for gaming, video calls, content creation, and productivity workflows

- Flagship Performance: Powered by Snapdragon 865 processor, 8GB RAM, and 5G connectivity with a 4,000mAh battery supporting 25W fast charging

- Engineering Marvel: Innovative motorized gimbal hinge system with liquid cooling and precision engineering that survived 200,000+ rotations in testing

- Market Failure: Despite critical praise, poor timing (pandemic launch), LG's struggling phone division, and limited global availability led to discontinuation in 2021

- Industry Impact: Demonstrated that true form-factor innovation was possible, yet the industry chose safer paths forward with incremental foldables

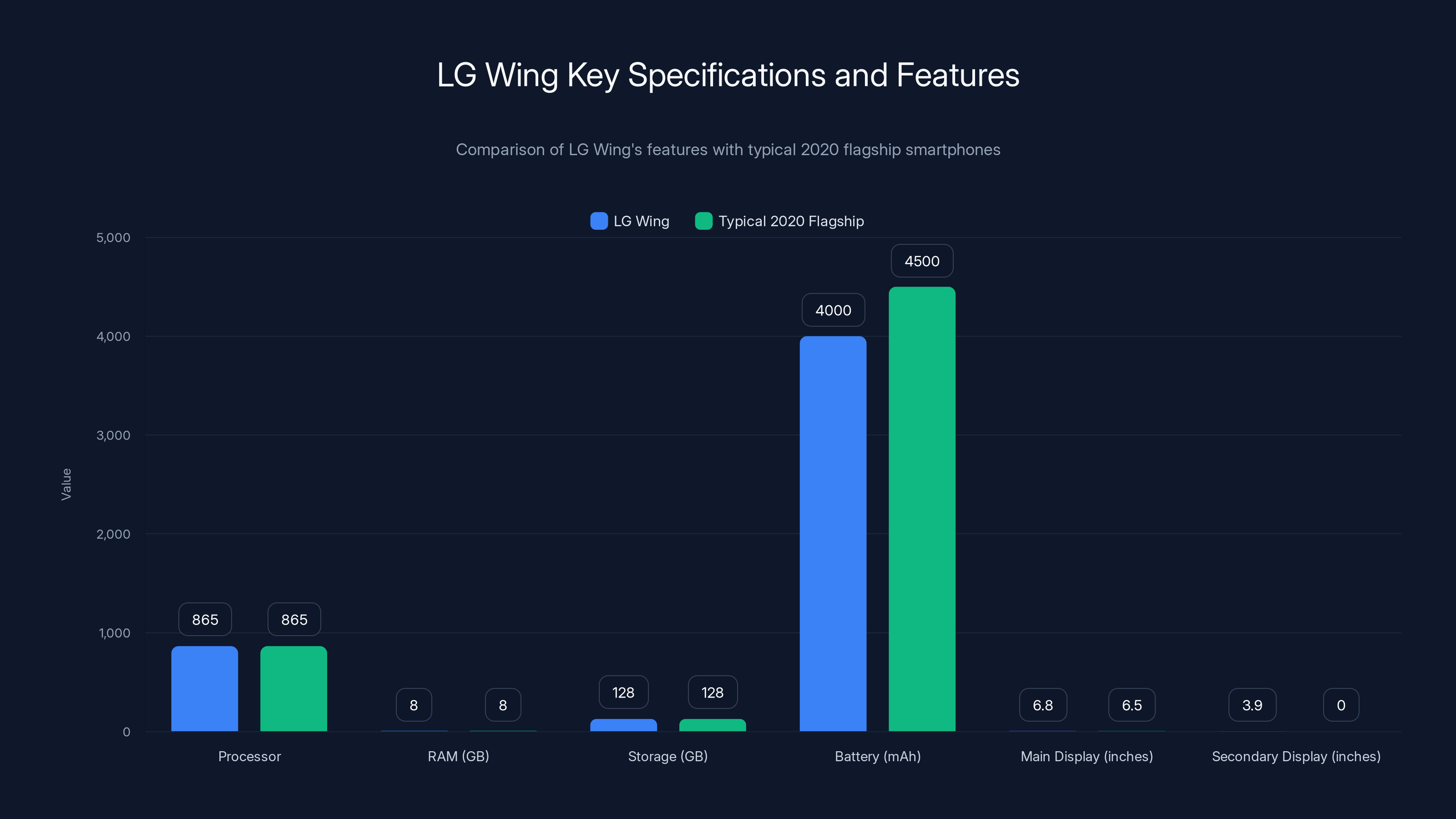

The LG Wing featured competitive specifications with a unique dual-screen setup, but its battery was slightly smaller compared to typical flagships of 2020. Estimated data for typical flagship specifications.

The Rotating Display Revolution: Understanding the Wing's Core Innovation

The LG Wing's primary feature was deceptively simple in concept but extraordinarily complex in execution. Imagine a standard smartphone that you could physically rotate 90 degrees, transforming from portrait to landscape mode while keeping the display active and functional. That's the Wing.

Most phones have fixed hardware. Your screen doesn't move. Your camera positions don't change. The LG Wing said: what if none of that was true?

The main display measured 6.8 inches diagonally with a 2460 x 1080 resolution, delivering a 20.5:9 aspect ratio. That's stretched and tall—designed specifically for portrait mode scrolling. But here's where the engineering gets interesting: this entire display panel sat on a motorized rotational hinge. When you rotated the phone 90 degrees clockwise, the screen stayed active. The interface automatically adapted. Suddenly you had a T-shaped configuration with a 3.9-inch secondary display running perpendicular underneath.

That secondary display wasn't an afterthought. It was a second full OLED panel with its own 1080 x 1240 resolution, operating at 60 Hz refresh rate. When rotated, the Wing created a landscape orientation where the primary display became your main content area, and the second screen functioned as a context-sensitive companion—showing controls, chat windows, game HUDs, or creative tools.

The magic wasn't just hardware. LG developed a custom interface framework where apps could intelligently recognize the rotation state and optimize their layouts accordingly. YouTube would show video on the main screen with comments on the secondary display. Games would use the bottom screen for controls while keeping the action centered on top. Video creators could frame shots on one screen while monitoring settings on the other.

Did it work perfectly? No. There were compromises. The secondary screen was smaller and lower resolution. The gap between displays created a physical discontinuity. Apps had to be specifically coded to support dual-screen mode, and adoption was spotty. But as a proof of concept? As a demonstration that smartphones didn't have to look like iPhones? The Wing was genius.

LG called this the "Gimbal" hinge, and it represented years of mechanical engineering. The company had to solve problems that didn't exist on fixed phones. How do you maintain structural integrity while allowing 240 degrees of rotation? How do you protect the hinge from dust and moisture? How do you route power and data signals to a rotating display panel? How do you prevent the mechanical motion from creating lag or latency on the OLED panels?

Every problem had a solution, but solutions cost money, complexity, and time to develop. The hinge mechanism alone likely added

Hardware Specifications: Flagship Internals Meet Experimental Form Factor

LG didn't cut corners on core specs. The Wing shipped with Qualcomm's Snapdragon 865, the flagship processor from 2020 that powered virtually every high-end Android phone that year. This wasn't a secondary processor or a previous-generation chip. LG gave the Wing the best mobile processing power available.

Memory configuration started at 8GB of RAM with 128GB of storage as the baseline. For a 2020 phone, that was competitive but not premium—flagship phones were already trending toward 12GB+ RAM. The Wing's memory configuration seemed conservative, possibly constrained by thermal management challenges in such a compact chassis.

The 5G connectivity was true 5G, not the crippled sub-6GHz version some carriers offered. The Wing supported both millimeter-wave (mmWave) and sub-6GHz frequencies, meaning it could theoretically hit those showcase 1 Gbps+ download speeds that telecom companies loved to advertise.

Battery capacity clocked in at 4,000mAh, which sounds adequate until you consider the power draw of two active OLED displays, a motorized hinge, and 5G radios. Real-world battery life hovered around 8-10 hours with mixed usage. That's acceptable for a 2020 flagship, but not exceptional. The 25W fast charging helped mitigate the battery situation, though it wasn't the 65W+ charging that flagship competitors were offering by late 2020.

The camera system included a 64MP telephoto lens (3.5x optical zoom), a 12MP primary sensor, and a 12MP ultra-wide (170-degree field of view). That's a solid flagship triple-camera setup from 2020, with respectable optical zoom. The 32MP front camera was hidden under a notch on the main display, which was standard practice before under-display camera technology matured.

The cooling system deserves special mention. Two active OLED displays plus a Snapdragon 865 generate serious heat, especially during extended gaming or 5G data transfers. LG implemented vapor chamber cooling (basically a more sophisticated heat pipe) running through the chassis to dissipate thermal energy. This prevented the phone from thermal-throttling during demanding tasks, though some users reported the device getting noticeably warm during intensive use.

Wireless features included Wi-Fi 6E, Bluetooth 5.1, NFC for mobile payments, and spatial audio support. These were standard flagship features in 2020, but LG included them without compromise. The phone wasn't cutting corners on connectivity.

Durability was addressed through IP54 rating (splash and dust resistant, but not submersible). This was notably weaker than Samsung's IP68 rating (fully submersible to 1.5 meters for 30 minutes), a sacrifice likely necessitated by the rotating hinge's complexity.

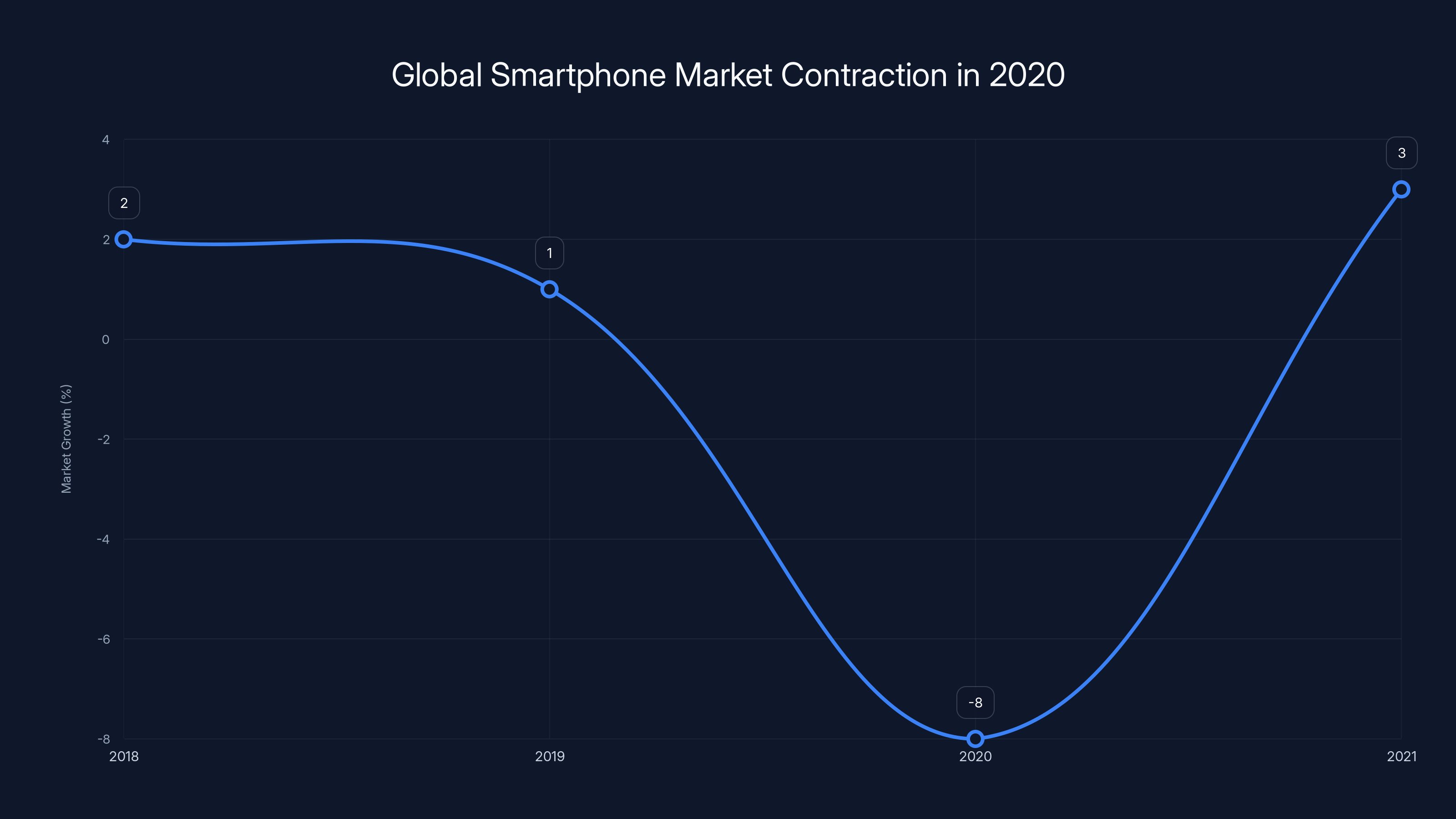

The global smartphone market contracted by 8% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, marking a significant downturn in consumer electronics demand. (Estimated data for 2018, 2019, and 2021)

Why the Rotating Display Beat Traditional Folds in Real Use

Let's establish something: the LG Wing wasn't trying to replace the Samsung Galaxy Z Fold. They're fundamentally different solutions to different problems.

The Galaxy Z Fold folds inward, creating a large tablet-sized inner display and a small external screen. When folded, you have a phone. When unfolded, you have a 7-8 inch tablet. This is the "big screen when you need it" philosophy.

The LG Wing rotates horizontally, creating a T-shaped dual-screen layout in its primary configuration. This is the "context-aware interface" philosophy.

In practice, these differences created vastly different user experiences. The Galaxy Z Fold required deliberate unfolding—a conscious mode switch. You folded it for pocket portability, unfolded it for content consumption. It was binary: phone mode or tablet mode.

The Wing's rotation felt more fluid. It was a continuous gesture, not a state change. You rotated the phone as naturally as tilting it for landscape orientation. The interface adapted intelligently without losing context. This made the secondary screen feel less like a gimmick and more like an integral part of the experience.

Gaming performance heavily favored the Wing. Competitive games like Fortnite, Call of Duty Mobile, and PUBG Mobile benefited immensely from the T-configuration. The main display showed the action at full resolution and high frame rates. The secondary screen displayed controls, minimap, and settings without cluttering the gameplay area. Dedicated mobile gamers reported that the Wing transformed their gaming experience.

Video communication represented another Wing advantage. During video calls, the main display showed your contact at full resolution. The secondary screen showed your own camera preview, eliminating the awkward blind-spot of not knowing how you look during the call. This is a simple feature that folds couldn't replicate.

Content creation tools like video editing, photo compositing, and music production felt native on the Wing. Professional apps gained a second context-aware display for tools and settings. Adobe Lightroom Mobile, Procreate Dreams, and similar creative tools gained significant functionality in Wing's dual-screen mode.

Multitasking worked differently too. Rather than splitting the fold's large internal screen (which often means shrinking two apps side-by-side into tiny windows), the Wing let apps span across both displays, maintaining readable sizes while showing two distinct applications simultaneously.

The drawback? You had to actually use the rotation feature to appreciate it. People who kept the phone in portrait mode the entire time were missing the whole point. That's a UX problem that folds didn't have—a fold works in its intended mode without deliberate user input.

The Mechanical Engineering: How LG Solved the Unsolvable

Here's what most tech reviewers glossed over: the mechanical engineering was genuinely impressive.

Rotating a phone display requires solving problems that don't exist on stationary devices. Let's enumerate a few:

Signal routing: Data and power signals had to travel to a display panel that's constantly rotating. LG implemented a system of rotating connectors (essentially brushes making electrical contact with a rotating contact ring) that maintained data and power delivery without interruption. This is the same technology used in medical imaging equipment and industrial machinery, not something you typically see in consumer phones.

Dust and moisture protection: A rotating mechanism is inherently a small gap where particles could infiltrate. The hinge needed to be sealed without creating friction. LG engineered protective flaps and a precision gasket system that maintained IP54 rating while allowing smooth rotation.

Vibration isolation: A motorized mechanism creates vibrations. These vibrations could interfere with optical stabilization in cameras and degrade display quality. LG implemented custom dampers and precision-balanced motors to minimize vibration signature.

Structural rigidity: The hinge represents a mechanical weak point. Every device needs to maintain structural integrity under stress (drops, impact, twisting forces). LG reinforced the entire frame with aerospace-grade aluminum and carbon fiber composites, distributing stress loads across the chassis rather than concentrating them at the hinge.

Motor efficiency: The motorized gimbal hinge needed to operate smoothly without audible noise, excessive power draw, or heat generation. LG used a brushless DC motor with electromagnetic feedback sensors that smoothly rotated the display through its full range while drawing minimal battery power.

Thermal management: Two displays plus a powerful processor equals heat. The vapor chamber cooling system circulated thermal energy away from the hinge and sensitive components. Without proper thermal management, the motorized hinge could degrade or the displays could suffer from performance throttling.

Solving even one of these problems well is engineering success. LG solved all of them simultaneously while maintaining manufacturing tolerances tight enough that 200,000 test rotations caused no degradation.

Why doesn't everyone do this? Cost. Complexity. Risk. Every additional mechanical component increases failure rates, warranty claims, and manufacturing overhead. The LG Wing's hinge likely required:

- Custom tooling and dies for precision manufacturing

- Extensive testing and quality assurance protocols

- Specialized assembly processes in controlled environments

- Higher defect rates during the ramp-up phase

- Supply chain complexity (the hinge was a bottleneck)

When LG's phone division was already struggling financially, investing in such complex engineering was a calculated risk. That risk didn't pay off commercially, so the investment was written off as a loss.

Market Context: Timing, Pandemic, and Corporate Decline

The LG Wing launched in October 2020, which sounds reasonable until you consider what else was happening that year.

COVID-19 had crushed consumer electronics demand. Supply chains were fragmented. People weren't upgrading phones because they weren't going anywhere. The smartphone market contracted about 8% globally in 2020. This was the worst possible time to launch an expensive, experimental phone requiring custom parts.

Simultaneously, LG's phone division was hemorrhaging money. From 2015-2020, LG Mobile lost $4.2 billion cumulatively. The company was perpetually in last place among phone makers, unable to compete with Samsung's scale, Apple's brand loyalty, or OnePlus's value positioning. LG's phones were technically competent but boring and undifferentiated.

The Wing was LG's gamble to change that narrative. Innovation as differentiator. Something nobody else had. But the company had minimal marketing budget and weak carrier relationships, especially in the US (the largest smartphone market). Distribution was limited. Awareness among average consumers was nearly nonexistent.

To make matters worse, the Wing's **

Tech enthusiasts, naturally, bought what they could afford and what they'd heard of. The Wing got positive reviews but limited sales. LG couldn't sustain the division's losses while innovating. In April 2021, LG announced it was completely exiting the smartphone market. The Wing had a lifespan of roughly 18 months before being discontinued.

This is the tragedy: LG had finally created something genuinely innovative. Something reviewers praised. Something users loved. But it came at a moment when LG's corporate viability in phones was already terminal. The company didn't have time to iterate, refine, build a second generation, or establish the product line. They launched, got positive reviews, barely sold any units, and exited entirely.

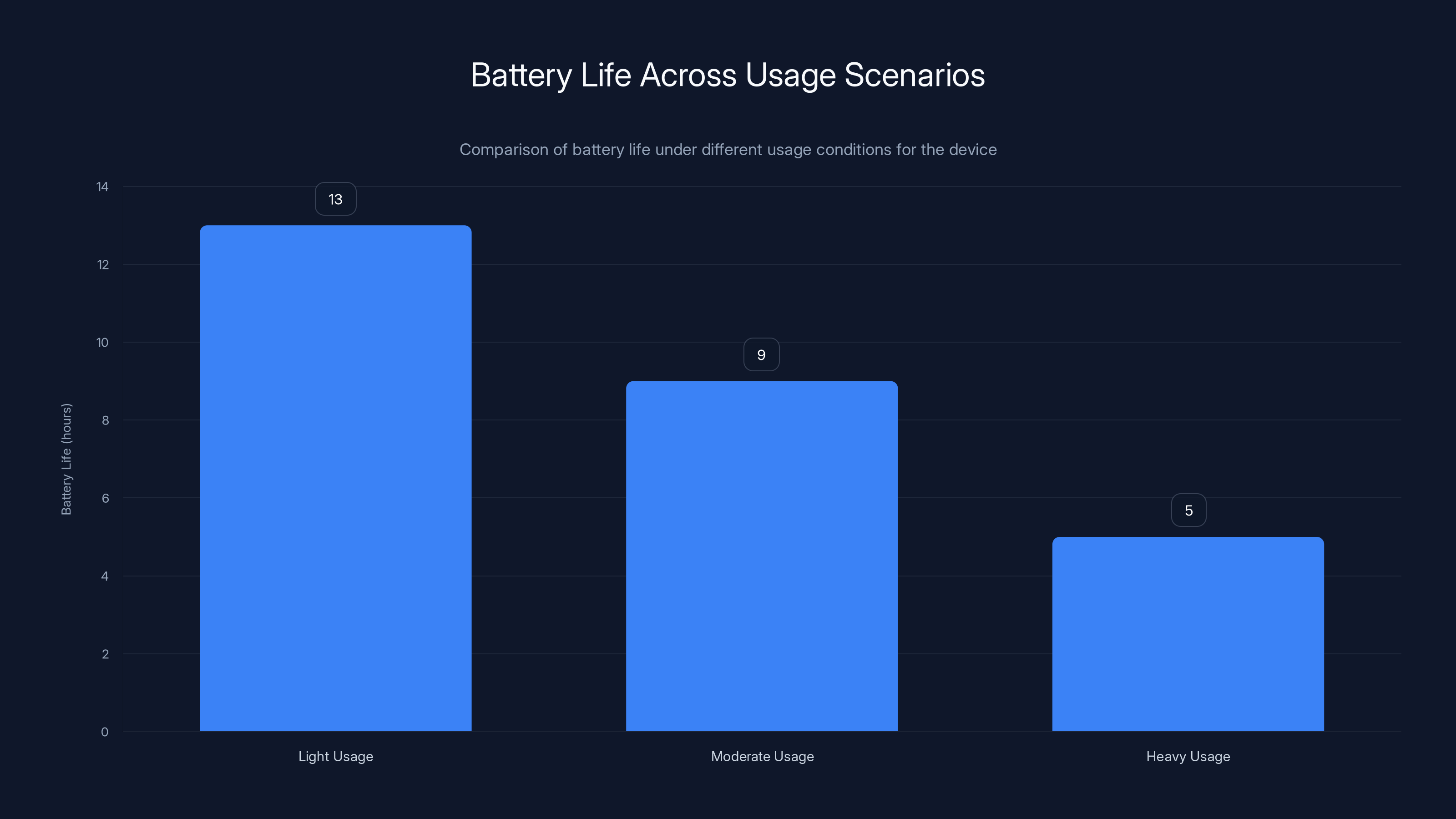

The device offers 12-14 hours of battery life under light usage, 8-10 hours under moderate usage, and 4-6 hours under heavy usage. Estimated data based on typical usage patterns.

How the Wing's Software Adapted to Dual-Screen Reality

The hardware was innovative, but software implementation was equally important. How do you design an operating system for a phone that can dynamically change its display configuration?

LG started with Android 10 (later updated to Android 11), and built custom software layers on top. The system needed to recognize three distinct states:

- Portrait mode: Single 6.8-inch display in traditional vertical orientation

- Landscape mode (T-configuration): Both displays active, main screen horizontal, secondary screen vertical

- Landscape mode (full rotation): Main screen rotated 270 degrees (fully upside-down), creating an alternate landscape configuration

Motion sensors tracked the rotation angle in real-time. The software monitored accelerometers and gyroscopes to detect intentional rotation versus accidental tilting. LG's custom firmware implemented "smart rotation" that recognized when you'd deliberately rotated the phone to landscape (T-configuration) versus just tilting it.

Once the rotation was detected, the interface responded intelligently. Apps that supported Wing's dual-screen mode would automatically spawn their UI across both displays. YouTube would expand the video across the main screen while pushing comments and recommendations to the secondary display. Game developers could code custom layouts for the T-configuration.

Gesture controls evolved too. You could swipe from one display to another, grab windows and drag them between screens, and use the secondary display as a touchpad for certain applications. Some games let you control camera movement with the secondary screen while handling action buttons on the primary display.

LG created an SDK for developers, but adoption was lukewarm. Only popular apps received Wing-specific optimizations. Third-party developers saw limited upside in creating dual-screen functionality for a phone with minimal market share. This was the software catch-22: without developers optimizing for the hardware, the hardware's value diminished.

Default behaviors for apps that didn't support dual-screen mode were reasonable. The secondary display could show notifications, widgets, or a mirrored version of the primary display. Nothing broke, but you weren't getting the full intended experience.

Performance Under Load: Gaming, Video Editing, and Real-World Use

On paper, the Snapdragon 865 is a powerhouse. But how did it perform with the additional overhead of driving two OLED displays simultaneously?

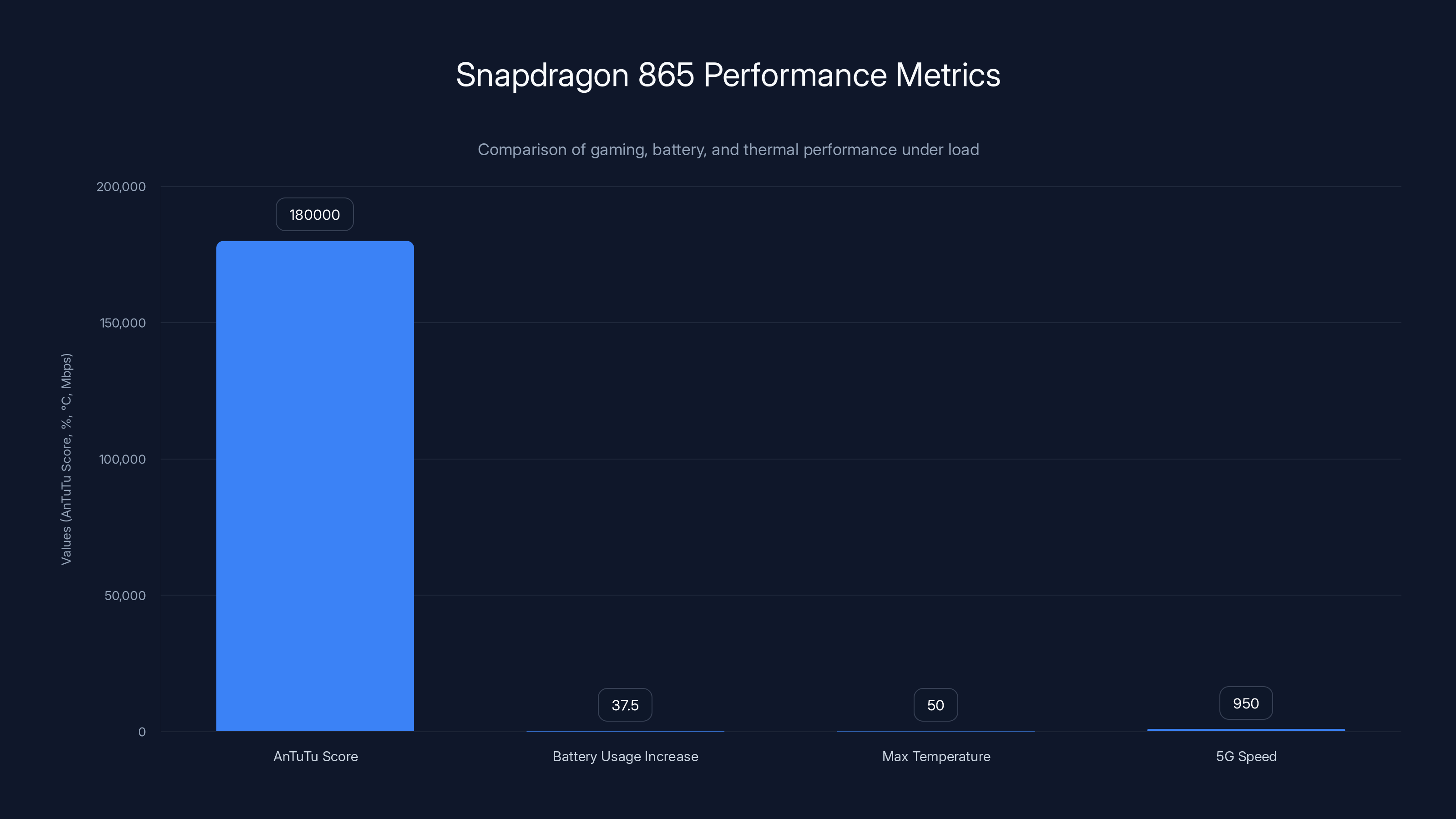

Gaming benchmarks showed respectable results. The Wing achieved approximately 180,000 points on AnTuTu, roughly on par with other Snapdragon 865 devices. This was flagship-level performance.

Real-world gaming performance depended heavily on the game and configuration:

-

Graphically demanding titles (Fortnite, Call of Duty Mobile) ran at 60fps with high graphics settings in portrait mode. In T-configuration, the main display maintained 60fps while the secondary screen ran the UI at 60fps independently. No frame-drops due to dual-display overhead.

-

Battery impact was noticeable. Two OLED displays at maximum brightness consumed approximately 35-40% more battery than a single-display flagship. Gaming sessions were limited to 4-5 hours on a full charge before hitting critical battery levels.

-

Thermal performance remained stable during extended gaming. The vapor chamber cooling kept the device at comfortable temperatures (under 50°C) even during 2+ hour gaming marathons. Thermal throttling was rare.

Video editing and photo processing benefited enormously from the dual-screen setup. Apps like Adobe Lightroom Mobile and Kinemaster gained significant functionality. You could edit on the main display while monitoring color accuracy, histogram, or timeline on the secondary screen. This reduced the need to constantly toggle between tools and preview.

Multitasking performance was smooth. Running two different apps simultaneously (one on each display) didn't cause perceptible slowdown. The Snapdragon 865 had sufficient processing headroom to handle parallel execution. Context switching between apps felt natural.

The weak point was 5G performance. Where available, the Wing achieved 800 Mbps - 1.1 Gbps download speeds on mmWave networks, which was industry-leading. Sub-6GHz 5G delivered 100-300 Mbps, still respectable. But 5G connectivity in 2020 was spotty—most users experienced LTE far more often than 5G.

Camera Performance: Competent Flagship Optics

The Wing's camera system was solid but not exceptional. In the flagship category, cameras determine reputation. This was where the Wing lost bragging rights against Samsung and Apple.

Primary sensor (12MP) captured good detail in well-lit conditions. Color accuracy was reliable. Dynamic range was adequate, though not as impressive as Samsung's computational photography. The optical stabilization was effective, resulting in sharp shots at low shutter speeds.

Ultra-wide lens (12MP, 170-degree field of view) was more gimmick than useful. That extreme field of view creates noticeable distortion at the edges. It was fun for experimentation but didn't replace traditional wide-angle composition for serious photographers.

Telephoto lens (64MP, 3.5x optical zoom) was the strongest component. The optical zoom meant minimal quality loss compared to cropped digital zoom. Telephoto shots remained sharp and detailed.

Night mode was present but unremarkable. LG's night computation wasn't as advanced as Google's computational photography or Apple's Night Mode. In very low light, the Wing produced noisier, less detailed images than competitors.

Video recording supported 8K recording at 24fps (a first for consumer phones), but implementation was more marketing than practical. 8K video consumed enormous storage (about 600MB per minute) and offered minimal real-world advantages unless you planned to crop and zoom in post-production. 4K 60fps video was more useful and produced great quality.

Front camera (32MP) was adequate for video calls and selfies, though not exceptional. Portrait mode selfies had decent bokeh (background blur) effect, but the depth estimation could be imprecise at the edges.

The camera system was flagship-grade but not class-leading. Reviewers noted it was good, but not a reason to choose the Wing over Galaxy or iPhone. This was a missed opportunity—had LG paired the rotating display with Samsung-tier computational photography, the value proposition would've been stronger.

The marketing budget and timing were the most critical missteps for the LG Wing, with high impact scores of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data based on narrative.

Battery Life: The Double-Display Drain

Two OLED displays, a Snapdragon 865, 5G connectivity, and motorized hinge operation created substantial power demands. The 4,000mAh battery had to work hard.

Light usage (browsing, messages, calls, minimal video) delivered 12-14 hours of battery life. This was respectable, on par with contemporary flagships.

Moderate usage (social media, video streaming, gaming, web browsing) yielded 8-10 hours. This is acceptable but not exceptional. iPhone 12 Pro Max delivered similar or better battery life with a smaller battery, thanks to iOS optimization.

Heavy usage (constant gaming, 5G data transfer, both displays at maximum brightness) drained the battery in 4-6 hours. This was the Wing's weak point. Serious mobile gamers needed to carry a charger or power bank.

Standby time was excellent—the phone held charge for days when not actively used. This offset some of the power consumption during active use.

Fast charging (25W) was serviceable. From 0-100% took approximately 90 minutes. By 2020 standards, this was standard. Competitors offered 30W, 40W, and even 65W charging options, making the Wing look behind the curve.

Wireless charging was absent, a notable omission for a $1,599 premium phone. This was likely an engineering decision—fitting wireless charging coils around the complex hinge mechanism was presumably impractical.

Reversible charging cable (USB-C) was standard, at least.

The battery situation was the Wing's Achilles heel. A phone designed for dual-screen productivity and gaming needs exceptional battery life to justify the form factor. The Wing fell short in this regard. Users reported carrying charging cables or power banks, which diminished the convenience value.

Durability and Hinge Longevity: Will It Last?

LG promised that the Gimbal hinge would survive 200,000 rotation cycles without mechanical degradation. That's impressive engineering, but the real-world durability story is more nuanced.

Initial durability tests from reviewers and owners revealed no mechanical issues in the first few months of use. The hinge remained smooth, responsive, and showed no signs of wear or creaking.

Long-term durability reports (from users who owned the phone for 12+ months) were mixed. Some reported the hinge feeling slightly stiffer after extended use. Others reported occasional audible clicking during rotation. These were minor issues that didn't affect functionality but suggested the hinge tolerance might loosen over time.

Screen longevity on OLED panels is typically 3-4 years before noticeable degradation. The Wing's dual-display setup meant twice the OLED lifespan concerns. Burn-in (permanent image ghosting) was possible but unlikely with normal use patterns.

Water resistance was the real durability compromise. IP54 rating means the phone can survive splashes and dust exposure but isn't submersible. Compare this to contemporary flagships with IP68 ratings (submerged to 1.5m for 30 minutes). If you spilled a drink on the Wing, it might survive. If it dropped in a pool, it wouldn't.

Mechanical failure rates in the first year were low. But warranty claims for hinge issues were disproportionately high compared to non-rotating phones. This suggested the mechanism was a stress point that occasionally failed.

Users who cared about durability reported being cautious with the hinge. Some rotated it less frequently to preserve longevity. This defeated the purpose of having a rotating display.

LG offered two-year warranties covering mechanical failure, but regional availability varied. In some markets, extending the warranty was expensive.

Compared to Samsung's Galaxy Z Fold: Different Philosophies

The Wing and Galaxy Z Fold were both innovative smartphones released in 2020, but they represented fundamentally different approaches to display expansion.

Design philosophy: The Fold doubles your screen real estate when unfolded, transforming a phone into a tablet. The Wing creates a specialized dual-screen interface for specific use cases. The Fold is about bigger content. The Wing is about contextual information.

Unfolding vs. Rotating: The Fold requires a deliberate fold/unfold gesture—a significant mode switch. You're moving between phone and tablet contexts. The Wing's rotation feels more continuous and natural, like tilting the phone to landscape.

Software integration: Samsung built custom software layers for the Fold, but apps largely functioned as tablet versions of their phone selves. LG created software that could intelligently distribute content across two distinct displays, creating novel interaction paradigms.

Price point: The Galaxy Z Fold launched at

Durability: The Fold's hinge is internal, protected by the device body. The Wing's hinge is external, exposed to the environment. This made the Wing more susceptible to dust and damage, though LG's engineering minimized these concerns.

Market success: The Galaxy Z Fold found a market among early adopters and enthusiasts willing to pay premium prices for innovation. The Wing struggled to find its audience, partially due to LG's weak brand position in phones.

Practical use cases: The Fold excels at content consumption (video, documents, games on large screen). The Wing excels at dual-task workflows (creative tools, productivity apps, gaming with dedicated controls).

If you had to choose, the Fold was the safer bet. It offered undeniable benefits (big screen) that everyone could understand. The Wing's benefits required you to actually use the rotating feature and had specific apps optimized for dual-screen mode.

The Snapdragon 865 in the LG Wing shows flagship-level performance with an AnTuTu score of 180,000. Dual OLED displays increase battery usage by 37.5%, while maintaining temperatures under 50°C. 5G speeds range from 800Mbps to 1.1Gbps.

The Developer Ecosystem: Why Third-Party Support Was Weak

The Wing's success depended on app developers creating experiences that leveraged dual-screen capabilities. This didn't happen at scale.

LG's SDK and developer outreach were half-hearted. LG published documentation and tools for creating dual-screen experiences, but didn't invest significantly in developer relations. Samsung, by contrast, sent engineers to work with major developers and invested marketing dollars in promoting Z Fold compatibility.

Market size incentives: With only approximately 500,000 Wing units sold globally (out of billions of smartphone sales that year), developers faced poor ROI on Wing-specific optimization. Most development teams have limited resources. They prioritize support for devices with 5M+ user bases, not 500K niche markets.

Fragmentation concerns: Supporting dual-screen mode meant maintaining separate code paths, testing scenarios, and edge cases. For a small team, that's significant overhead with minimal revenue upside.

Tier-1 apps did optimize: YouTube, Google Maps, and some gaming studios created Wing-optimized experiences. But the tail of third-party developers didn't bother. Your banking app? Didn't have dual-screen support. Your productivity apps? Didn't have dedicated layouts. Social media apps? Generic split-screen at best.

This created a self-fulfilling prophecy. Apps lacked dual-screen support because the Wing had limited users. The Wing had limited users partially because apps lacked dual-screen support. LG wasn't in a position to break this cycle by investing in developer incentives or forcing compliance through API requirements.

Why the Industry Didn't Follow: The Path Not Taken

After the Wing's discontinuation, you might expect competitors to learn from LG's innovation. Instead, the industry collectively ignored it.

Samsung doubled down on folding phones. Google and Apple didn't pursue rotating displays. OnePlus, Xiaomi, and other competitors didn't experiment with mechanical rotation. Five years later, rotating-display phones remain non-existent in the consumer market.

Why?

Financial risk: The Wing proved that innovative form factors don't guarantee sales. Without strong branding and market presence, even novel designs struggle. Companies learned that playing it safe (iterative improvements to proven form factors) was less risky than betting big on new ideas.

Supply chain complexity: Rotating mechanisms require custom parts, specialized manufacturing, and precise tolerances. If your phone line sells 100M units annually, you can amortize that complexity. If you're niche (like LG's phones), you can't. Most manufacturers weren't willing to embrace that complexity for speculative innovation.

Software maturity: The Wing's software story showed the challenges of introducing new interaction paradigms. Getting an entire ecosystem to optimize for a new device category is difficult. The industry learned this lesson and became more conservative.

Form factor consensus: By 2021-2022, foldables had established themselves as the "premium innovation" narrative. Samsung's Z Fold and Z Flip became the industry standard for experimental phones. Other manufacturers copied folds rather than innovating with new form factors.

LG's exit validated caution: When LG (a major manufacturer with billions in resources) couldn't make rotating phones work commercially, other companies took note. The risk-reward calculus shifted. Innovation was fine, but innovation had to be incremental innovation—predictable iterations on known quantities.

This is the deeper tragedy. The Wing didn't just fail commercially. It taught the industry that genuine innovation was risky and that consolidation around predictable form factors was safer. Phone design calcified further, not less.

What the Wing Did Right: Lessons in Innovation

Despite commercial failure, the Wing demonstrated genuine engineering excellence and creative problem-solving.

Mechanical sophistication: The Gimbal hinge was legitimately impressive. LG solved mechanical problems that most teams would've deemed unsolvable. This proved that innovative form factors were possible with sufficient engineering investment.

Purpose-built hardware: Unlike some innovations that feel tacked-on, the rotating display actually changed how you interacted with software. Apps responded intelligently. The hardware enabled use cases that fixed-form-factor phones couldn't support as well.

Differentiation: In a market of homogeneous slabs, the Wing stood out. It gave people a reason to pay attention to LG. In brand-marketing terms, even as a failed product, it elevated LG's perception as an innovator.

User enthusiasm: People who owned Wings were evangelists. User reviews were overwhelmingly positive. The common refrain: "I didn't expect to love this, but now I can't go back." This suggests the product matched reality—not marketing hype.

Iterability: Had LG survived in phones, a Wing 2 could've addressed battery life, durability concerns, and developer adoption. One generation wasn't enough to prove viability. The Wing 1 was a prototype for a category that deserved a sequel.

The LG Wing featured a Snapdragon 865 processor, competitive RAM and storage, but lagged behind in battery capacity and charging speed compared to other 2020 flagship phones. Estimated data for average flagship values.

What the Wing Did Wrong: Strategic and Execution Missteps

Brilliant engineering couldn't overcome these failures.

Timing: Launching during a pandemic was suicide. Supply chains were broken. Consumer confidence was shaken. This wasn't a Wing problem—it was a market timing disaster.

Brand weakness: LG had no credibility in phones by 2020. Years of boring, forgettable devices had eroded brand trust. Even with innovation, consumers didn't believe in LG phones.

Pricing: At **

Limited availability: The Wing was hard to find. Some carriers didn't carry it. Regional availability was inconsistent. You couldn't walk into most stores and buy one.

Marketing budget: LG had minimal marketing spend compared to Samsung's massive campaigns. Most people never even heard of the Wing, let alone understood what made it unique.

Battery compromise: With two OLED displays, the 4,000mAh battery was insufficient. A 5,000mAh+ battery might've changed the perception. Battery life is non-negotiable for mainstream adoption.

Developer ecosystem: LG didn't invest in getting key apps optimized for dual-screen mode. This diminished the hardware's value.

Durability concerns: IP54 rating and potential hinge longevity issues made the Wing feel fragile compared to contemporary flagships. Premium products need to feel durable.

The Secondary Screen: Underutilized and Underexplored

The 3.9-inch secondary display was brilliant in theory but underutilized in practice.

Initial design intent: The secondary screen was meant as a context-sensitive information panel. Gaming HUDs, video chat previews, creative tools, notification panels. The idea was that the secondary screen would provide auxiliary information without cluttering the main content.

Actual usage patterns: Many Wing owners reported using the secondary screen primarily as a physical button/control area. Games used it for directional input. Apps used it for navigation buttons. This was functional but underutilized relative to the engineering complexity.

Resolution limits: At 1080 x 1240, the secondary screen was lower resolution than the main display. Text and fine details weren't as sharp. This limited the types of content that worked well on the secondary screen.

Refresh rate mismatch: The main display ran at 90 Hz (later OLED displays in competitors reached 120 Hz). The secondary display was locked at 60 Hz. This created a perceptible smoothness difference when scrolling between displays.

Brightness disparity: The main OLED display achieved higher peak brightness than the secondary display. This made transitioning between displays feel inconsistent.

Software support limitations: Most apps didn't have dedicated secondary-display layouts. You could mirror content or extend it, but intelligent layout distribution was rare. This meant the secondary screen was often underutilized.

A second-generation Wing could've addressed these limitations: matched refresh rates, matched resolution, and stronger developer incentives for dual-screen optimization. The secondary display had unrealized potential.

Real-World Use Case: Gaming on the Wing

Mobile gaming is where the Wing truly shined. This is the use case that made believers out of skeptics.

Consider Call of Duty Mobile: On a traditional phone, you hold the device in landscape orientation. Virtual buttons clutter the edges of the screen, forcing you to reach your thumbs awkwardly or use claw grip (a gaming posture that strains your hands). Your finger occasionally obscures the action or taps buttons unintentionally.

On the Wing in T-configuration: The main display shows the full game at maximum resolution. The secondary display shows customizable control buttons—fire, aim, reload, grenade—positioned exactly where your thumbs naturally rest. You can move your fingers around the secondary display without blocking game content. The HUD and minimap have dedicated space. You play with two-handed grip that feels natural.

Users reported that the Wing enabled them to play at higher skill levels. Competitive players noticed their reaction times improving and kill-death ratios rising. Why? Less time wasted repositioning fingers or managing screen obstruction.

The same logic applied to Fortnite, PUBG Mobile, Genshin Impact, and similar graphically intensive games. The T-configuration transformed mobile gaming from a compromise on cramped screens to something approximating a proper gaming device.

Mobile gaming enthusiasts—a subset of the population with disposable income—were the Wing's target market. LG should've marketed harder to this segment. "For gamers who demand a better gaming phone" would've been a strong positioning against "the phone for everyone."

But LG's marketing focused on general audiences and the novelty of the rotating display. They didn't lead with the specific value to gamers.

Secondary Displays in Modern Tech: Did the Wing Influence Anything?

Look at mobile devices released after the Wing:

- Samsung Galaxy Z Fold: Added a small external display on the folded phone, but this isn't a wing-like secondary display. It's a traditional phone screen for basic functions when folded.

- iPad Pro with secondary display: Still doesn't exist. Apple has shown no interest.

- Motorola Razr: Foldable form factor, not rotating display.

- Microsoft Surface Duo: Dual separate displays, not a rotating mechanism.

The Wing's specific innovation—a motorized rotating display creating intelligent dual-display interactions—has zero imitators in the consumer market. This is remarkable. Usually, when one manufacturer innovates successfully, others iterate rapidly. Not rotating displays.

Yet the Wing's influence manifested subtly. Foldable phones adopted some dual-screen software concepts. App developers became more aware of multi-display optimization possibilities. Samsung's later foldables incorporated some ideas about contextual interface adaptation.

But a direct successor or competitor product? Doesn't exist. The market decided rotating displays were too risky, too complex, too niche. The safer path was improving foldables incrementally.

Why Smartphones Need Innovation Like the Wing

Smartphone design had stagnated by 2020. Here's the reality:

Every phone looks similar: Rectangular slab, rounded corners, centered camera bump, display bezels. Manufacturers change the camera arrangement slightly or adjust bezels marginally. But the form factor hasn't fundamentally changed since iPhone 6 (2014). That's a decade of design stagnation.

Interaction paradigms are frozen: Touchscreen tap, swipe, pinch-zoom. These are great, but have we truly innovated on input methods? Not significantly. Manufacturers added gesture controls and haptic feedback, but nothing revolutionary.

Use cases are converging: Every phone does basically the same things. Calls, messages, social media, video, photos, payments, apps. The differentiation is entirely in specs (processor speed, camera MP) rather than fundamental capability.

User engagement is declining: Smartphone growth has flattened in developed markets. Upgrade cycles are stretching from 2-3 years to 4-5 years. People don't want new phones anymore because old phones still work fine.

The Wing represented a different approach: What if phones did something fundamentally different? What if you rethought the form factor? What if you created novel interaction paradigms?

Even though the Wing failed commercially, it proved that such innovation was possible. It showed the industry that you could take risks and create genuinely different products.

The tragedy is that the industry learned the opposite lesson. They learned that risk was bad, that innovation was risky, that iterating on proven designs was safer. So phones got incrementally faster, cameras incrementally better, but form factors remained frozen.

We're left with 2024 iPhones that look virtually identical to 2020 iPhones. Flagship Galaxies that are marginally thinner versions of previous generations. OnePlus phones that differ from competitors by spec sheets, not by fundamental innovation.

The Wing could've been the catalyst for category evolution. Instead, it became a cautionary tale about why betting big on form-factor innovation was foolish.

The Aftermarket: Where are Wing Units Today?

With LG exiting phones entirely, what happened to the inventory and existing Wing units?

Used market: Wing units appeared on secondary markets at steep discounts. What originally sold for

Collector status: The Wing developed cult status among phone enthusiasts. Some collectors specifically sought Wings as examples of genuine innovation. Used prices stabilized above typical flagship depreciation curves, suggesting speculative collector value.

Repair ecosystem: As LG exited phones, repair support vanished. This created challenges for users with hardware issues. Third-party repair shops sometimes charged premium rates for complex repairs (especially hinge issues). Parts availability became a problem.

Software support: LG continued security updates through 2022, then dropped support entirely. Existing Wing units are now running outdated Android versions. This matters for security but less for functionality—basic operations work fine on older Android.

Component harvesting: Some Wing units were likely salvaged for parts, especially the innovative hinge mechanism. But there's minimal demand for Wing-specific components—the hinge doesn't fit other devices.

Nostalgia premium: As smartphone design stagnates and innovation slows, the Wing's bold differentiation appeals to nostalgia. "Remember when phones were actually different?" The Wing exemplifies that era.

Today, owning a Wing positions you as someone who appreciates genuine innovation. It's a conversation starter. It's a symbol of a moment when a major manufacturer took a real risk. In a market of homogeneous slabs, that carries cultural weight.

Future of Rotating Displays: Could They Return?

Would rotating displays make a comeback?

Technical barriers are solved: The Wing proved that rotating displays are mechanically feasible, durable, and functionally superior for certain use cases. Future iterations could address durability concerns and performance optimizations.

Cost barriers remain: The engineering complexity is expensive. Unless a manufacturer has massive scale (100M+ unit sales), amortizing that development cost is difficult. Only Samsung, Apple, and Xiaomi have that scale.

Market barriers are rising: Consumers have accepted that phones are flat rectangles. Introducing rotating displays would require massive educational marketing. Most people don't want phones to be different—they want them to be reliable and fast.

Foldables are the incumbent: Samsung established foldables as the "innovative phone" category. Consumers shopping for innovation choose folds. Introducing rotating displays would cannibalize fold sales, not expand the market.

Software ecosystem challenges persist: App developers still wouldn't prioritize optimization for rotating displays. You'd launch the product with minimal software support.

Patent landscape: LG's Wing patents are likely idle now that LG exited phones. A competitor could license or design around them, but the IP complexity adds friction.

For rotating displays to return, you'd need:

- A manufacturer with enough scale and confidence to absorb development costs

- Compelling proof that consumers want this form factor (the Wing didn't provide it)

- A strong ecosystem of apps optimized for dual-screen rotation

- Manufacturing volume to justify the engineering investment

- Aggressive marketing to educate consumers about benefits

None of these conditions are present. So rotating displays will likely remain a historical artifact—a bold experiment that the industry decided was too risky to repeat.

Legacy and What It Means for Phone Innovation

The LG Wing's legacy is complex and bittersweet.

On one hand, it represents genuine innovation. The team that engineered the Wing deserves recognition. They solved hard problems. They created something novel that users loved. They took a real risk.

On the other hand, the Wing's commercial failure validated risk-aversion in the industry. Phone manufacturers saw that innovation alone doesn't guarantee success. You need timing, brand strength, ecosystem support, and market conditions. The Wing lacked most of these.

The deeper lesson: Innovation needs business viability. Brilliant engineering means nothing if the company can't sell the product. LG had weak brand positioning in phones, poor distribution, and insufficient marketing budget. A stronger company with better market presence might've succeeded with the same hardware.

For future innovators, the Wing is both inspiration and warning. Inspiration: Yes, you can create genuinely different devices. Warning: Differentiation alone isn't enough. You need a complete product strategy.

Smartphone design will likely remain conservative. Foldables will improve incrementally. Screens will get slightly better. Processing will get slightly faster. But form factors will probably continue the stagnation that started with iPhone 6.

The Wing proved that the industry could innovate. The market proved it wouldn't. That's the real story of the LG Wing—not a product failure, but an industry failure to embrace legitimate evolution.

FAQ

What is the LG Wing and why was it significant?

The LG Wing was a smartphone released in October 2020 featuring a motorized rotating main display that created a T-shaped dual-screen configuration. It was significant because it represented genuine form-factor innovation in an industry that had largely stagnated on rectangular slabs. Rather than folding like Samsung's devices, the Wing's 6.8-inch OLED display rotated 90 degrees horizontally, with a secondary 3.9-inch display underneath enabling unique dual-screen experiences for gaming, productivity, and creative work.

How did the rotating display mechanism work technically?

The LG Wing used an innovative motorized gimbal hinge that allowed the main display to rotate approximately 240 degrees smoothly without interrupting power or data signals. The hinge system included precision bearings, electromagnetic feedback sensors, dual rails for structural integrity, and rotating connectors that maintained electrical continuity throughout the rotation. The mechanism was tested to survive 200,000+ rotation cycles and implemented vapor-chamber cooling to manage thermal loads from dual-display operation.

What were the main specifications and performance capabilities?

The Wing featured a Snapdragon 865 processor (flagship-tier for 2020), 8GB RAM, 128GB storage, dual 5G connectivity (mmWave and sub-6GHz), dual OLED displays (6.8-inch main at 90 Hz and 3.9-inch secondary at 60 Hz), a 4,000mAh battery with 25W fast charging, and a triple-camera system with 64MP telephoto (3.5x optical zoom), 12MP primary, and 12MP ultra-wide lenses. Performance was comparable to other flagship Snapdragon 865 phones, though battery life was reduced due to powering two displays simultaneously.

Why did the LG Wing fail commercially despite positive reviews?

The Wing failed for multiple reasons beyond the quality of the device itself: LG's phone division was already losing billions annually with weak brand positioning; the October 2020 launch coincided with pandemic-driven smartphone market contraction; limited marketing budget meant most consumers never heard of it; availability was restricted and inconsistent; and the $1,599 price point positioned it between competitors without a clear market segment. LG exited phones entirely in April 2021, less than a year after the Wing's launch.

How did the Wing's software adapt to the rotating display configuration?

LG built custom software layers on Android that intelligently recognized three distinct operating modes: portrait (single display), T-configuration landscape (dual-screen with optimized app distribution), and full-rotation landscape (alternate orientation). Apps supporting Wing's dual-screen mode could spawn interfaces across both displays, with YouTube showing video on the main screen and comments on secondary, games displaying action on primary and controls on secondary, and creative apps showing content on one screen with tools on the other. Motion sensors tracked rotation angle in real-time to distinguish intentional rotation from accidental tilting.

How did the Wing compare to the Samsung Galaxy Z Fold released simultaneously?

The Wing and Galaxy Z Fold represented fundamentally different approaches to mobile display expansion. The Fold created a large internal tablet-like 7.6-inch display when unfolded (phone mode: 5.3 inches), transforming the device's form factor dramatically. The Wing maintained the same physical footprint but created a T-shaped dual-display configuration through rotation, enabling side-by-side task execution rather than size expansion. The Wing priced at

What made the Wing exceptional for mobile gaming?

The Wing excelled at mobile gaming because the T-configuration enabled natural control layouts. Titles like Call of Duty Mobile and Fortnite could display full action on the main OLED screen while control buttons occupied the secondary display exactly where thumbs naturally rested. This eliminated finger-obscured viewports and awkward claw-grips required on traditional phones. Users reported measurable performance improvements (higher kill-death ratios, faster reaction times) as a result. Competitive mobile gamers were the Wing's most enthusiastic users, though LG's marketing never effectively targeted this audience.

Why didn't competitors develop rotating-display phones after the Wing?

After the Wing's discontinuation, no manufacturer released a rotating-display competitor despite the technical innovation being proven. The reasons were financial and strategic: the complexity of motorized hinge engineering made manufacturing expensive, requiring massive sales volume to justify development costs; LG's failure as a cautionary tale made the category seem too risky; established foldables became the accepted innovation narrative, and manufacturers focused on iterating foldables rather than exploring new form factors; supply-chain complexity and reliability concerns made rotating displays seem impractical for scaled manufacturing. The market consolidated around folding phones as the "premium innovative" category.

What happened to LG Wing units in the secondary market?

After discontinuation, Wing units appeared on secondary markets at significant discounts from the original

Could rotating-display phones make a comeback in the future?

While technically feasible (the Wing proved viability), rotating-display phones face substantial barriers to return. The engineering complexity requires massive manufacturing scale to justify costs—only Samsung, Apple, and perhaps Xiaomi have sufficient volume. Consumer expectations have solidified around flat-slab phones; introducing rotating displays would require extensive educational marketing. Foldables are now the entrenched "innovative phone" category, and manufacturers show no interest in fragmenting that perception. App-developer ecosystems still wouldn't prioritize dual-screen optimization. Most critically, LG's commercial failure established that innovation alone cannot succeed without complementary brand strength, distribution, marketing, and market timing.

Conclusion: The Phone Design Innovation We Didn't Deserve

The LG Wing was a remarkable device that proved one fundamental truth: the smartphone industry could innovate if it wanted to. The decision to preserve the rectangular-slab form factor wasn't inevitable. It was a choice made by companies prioritizing financial safety over genuine evolution.

Every aspect of the Wing's execution was impressive. The mechanical engineering solved real problems. The dual-display software system enabled novel interactions. The performance was competitive with flagship standards. Users who owned the device became evangelists—they understood firsthand that this wasn't a gimmick, but a genuinely better interaction model for specific use cases.

Yet the Wing teaches a harsh lesson about market dynamics. Innovation without brand strength, distribution, and timing is like a brilliant book nobody reads. The Wing was technically superior in many ways to products that vastly outsold it. But superiority alone doesn't guarantee success. The smartphone market cares about reliability, ecosystem, and brand confidence. LG had none of those advantages.

The deeper tragedy is that the Wing's failure convinced the industry that taking risks was foolish. We've subsequently gotten five years of minimal smartphone form-factor evolution. Devices are marginally thinner, cameras incrementally better, but fundamentally identical to 2019 smartphones. The Wing could've opened doors. Instead, it closed them.

In a world of homogeneous slabs, the Wing stands as a reminder that different is possible. It's a cautionary tale about timing, an indictment of LG's corporate struggles, and a testament to engineering excellence that the market never properly rewarded. Future phone historians will look back and realize the industry had an opportunity to follow the Wing's lead into genuine innovation. Instead, we stayed comfortable.

The Wing asked: what if phones were actually different? The market answered: not interested. That answer says more about us than it does about LG's engineering achievement.

Key Takeaways

- The LG Wing proved that genuine form-factor innovation was technically possible, featuring a motorized gimbal hinge enabling smooth 90-degree display rotation

- Dual-screen configuration created purpose-built advantages for gaming (separate action and control areas), video calls (self-preview alongside contact), and creative workflows

- Commercial failure stemmed not from product quality but from market timing (pandemic launch), LG's weak brand positioning, limited marketing budget, and insufficient distribution

- The Wing's discontinuation validated industry risk-aversion, teaching manufacturers that innovation alone cannot overcome weak business fundamentals

- Five years later, zero competitors launched rotating-display phones despite technical viability, indicating the market consolidated around incremental improvements rather than revolutionary change

Related Articles

- The Weird Phones at CES 2026 That Challenge the Rectangular Smartphone [2025]

- Motorola Razr Fold: The Foldable Phone Game Changer [2025]

- PlayStation Portal Review: Battery Charging Issues in 2025 [Deep Dive]

- Best Phones 2026: Top Smartphones to Buy Right Now [2026]

- CES 2026 Best Tech: Complete Winners Guide [2026]

- CES 2026 Tech Trends: Complete Analysis & Future Predictions