The M&A Paradox: Headlines vs. Reality

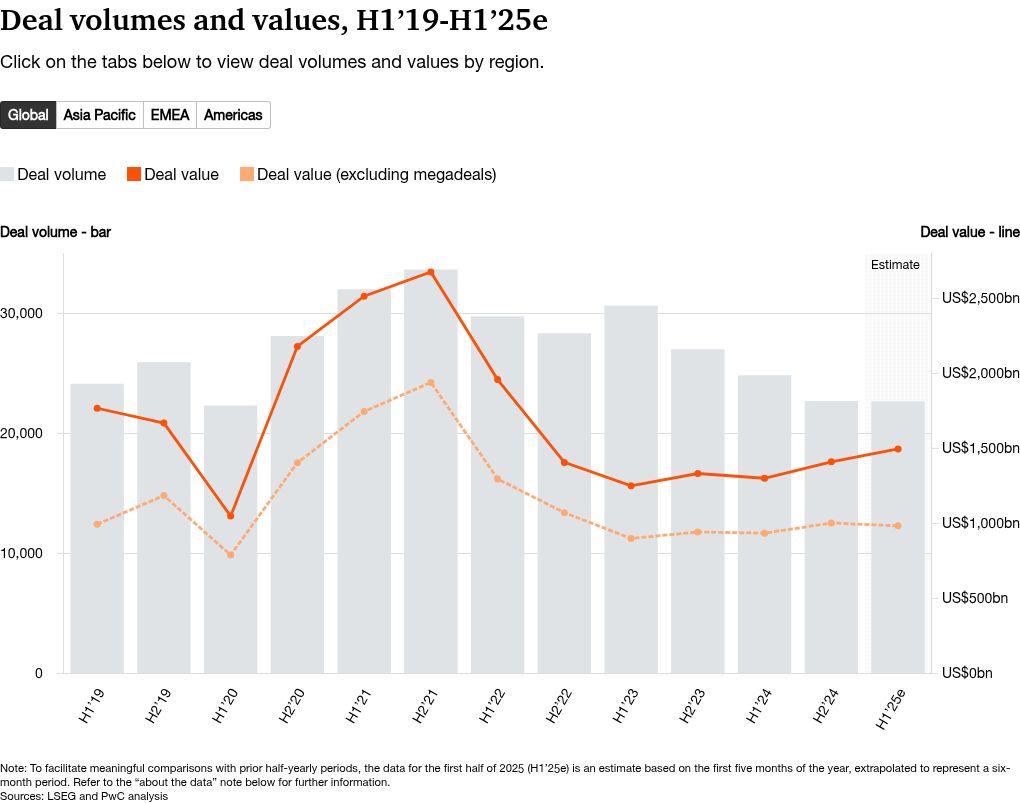

The past twelve months have delivered some genuinely stunning acquisition announcements. Nvidia dropped

But here's the thing that keeps showing up in the actual data, and it's kind of terrifying if you're sitting on equity in a company hoping for an exit: the deals you actually hear about represent a tiny, privileged slice of what's happening in the market.

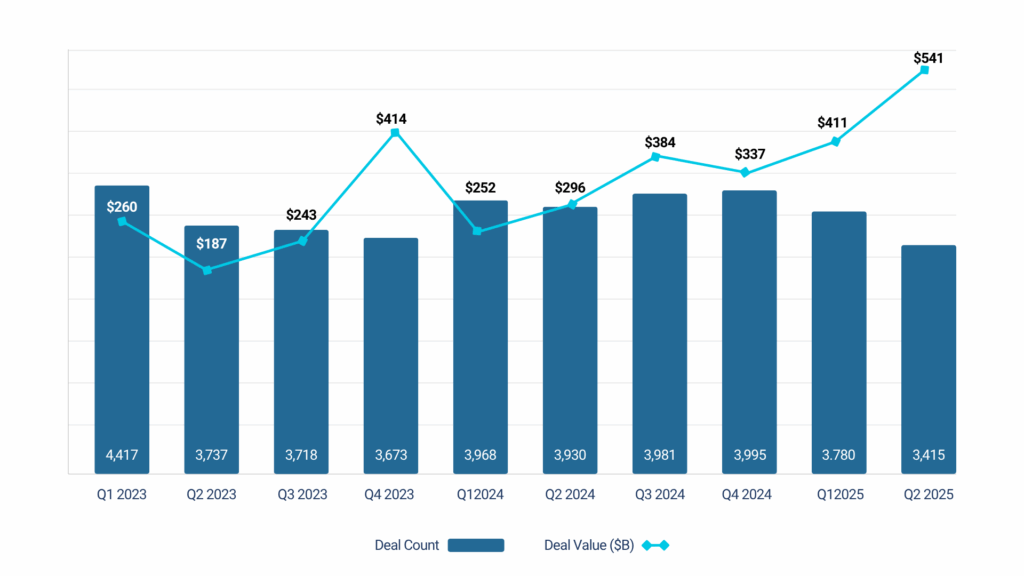

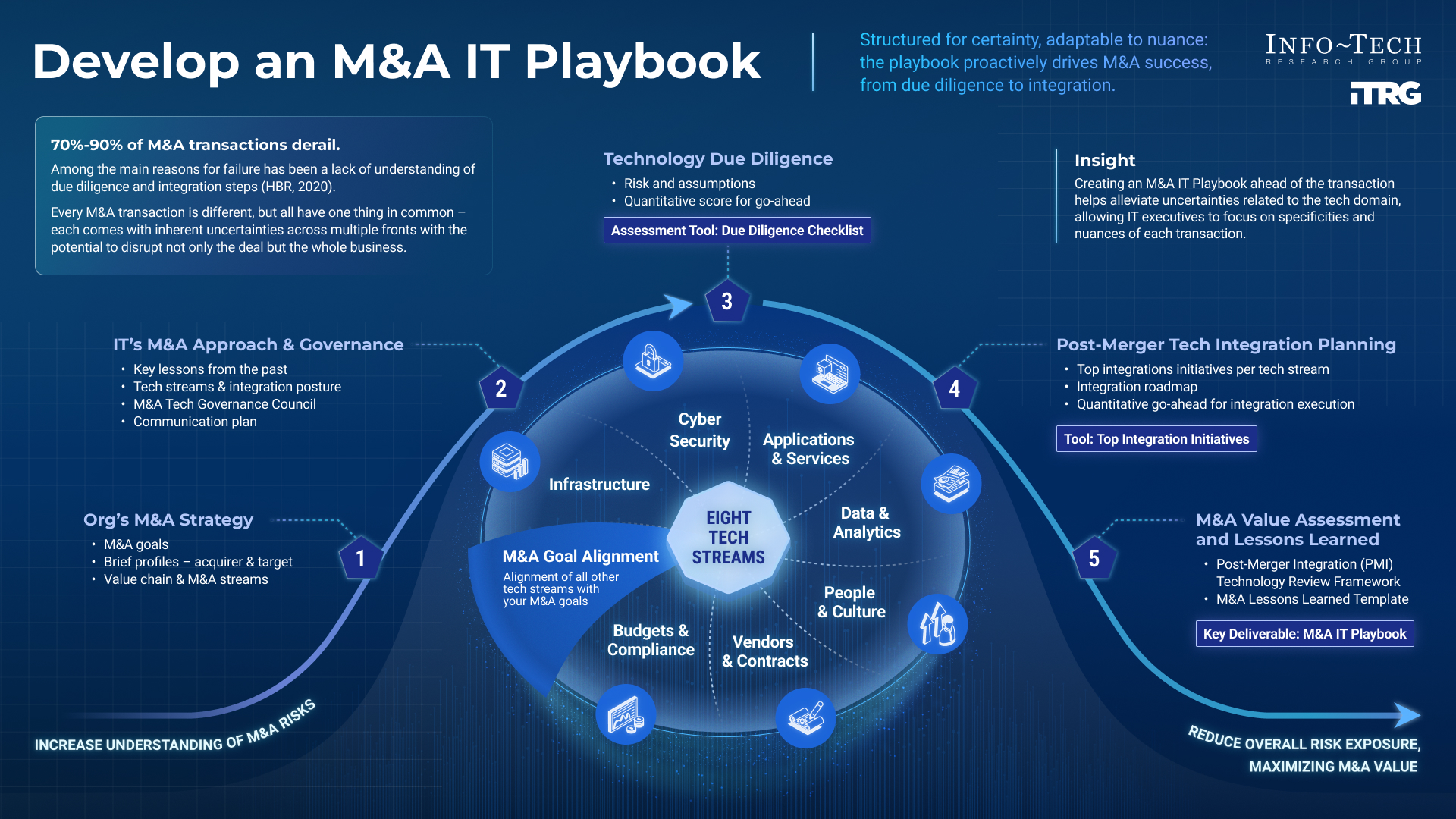

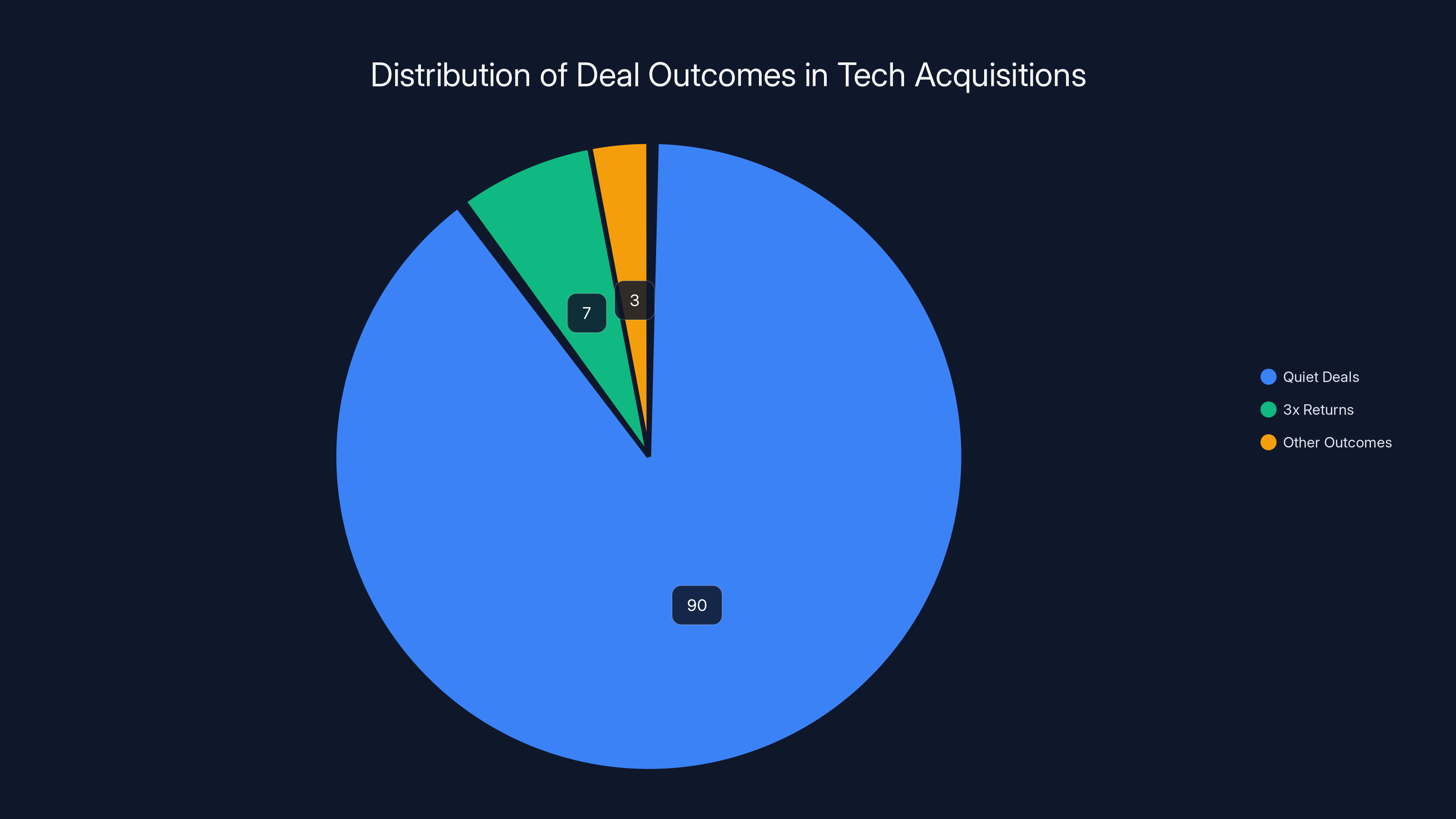

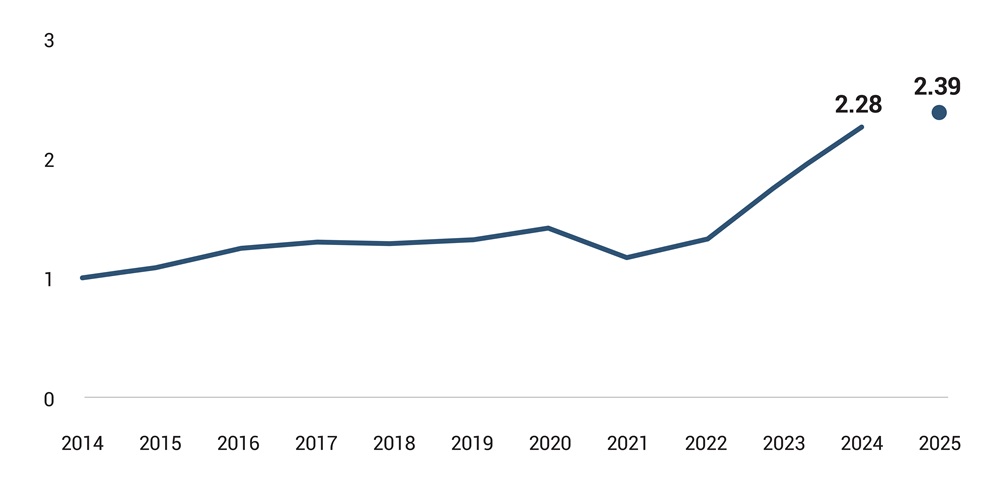

When you dig into the confirmed outcomes, when you look at deals where both parties actually disclosed what happened, the picture gets much darker. Only 7% of disclosed M&A deals in 2025 returned 3x or more to VCs. That's not a typo. Seven percent.

In 2021, that number was 22%. In 2019, it was 15%. We're talking about a two-thirds collapse in confirmed good outcomes over just four years.

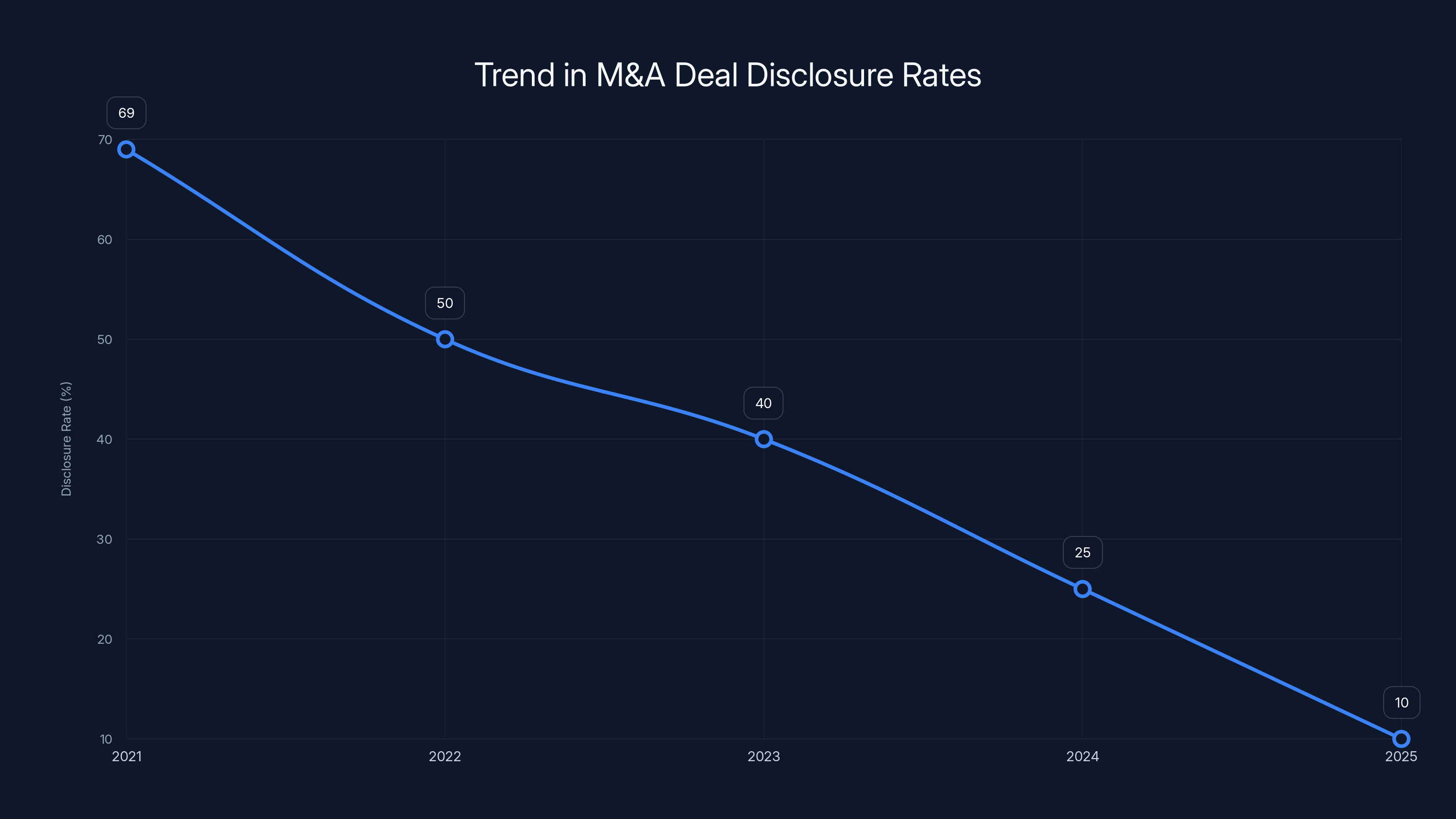

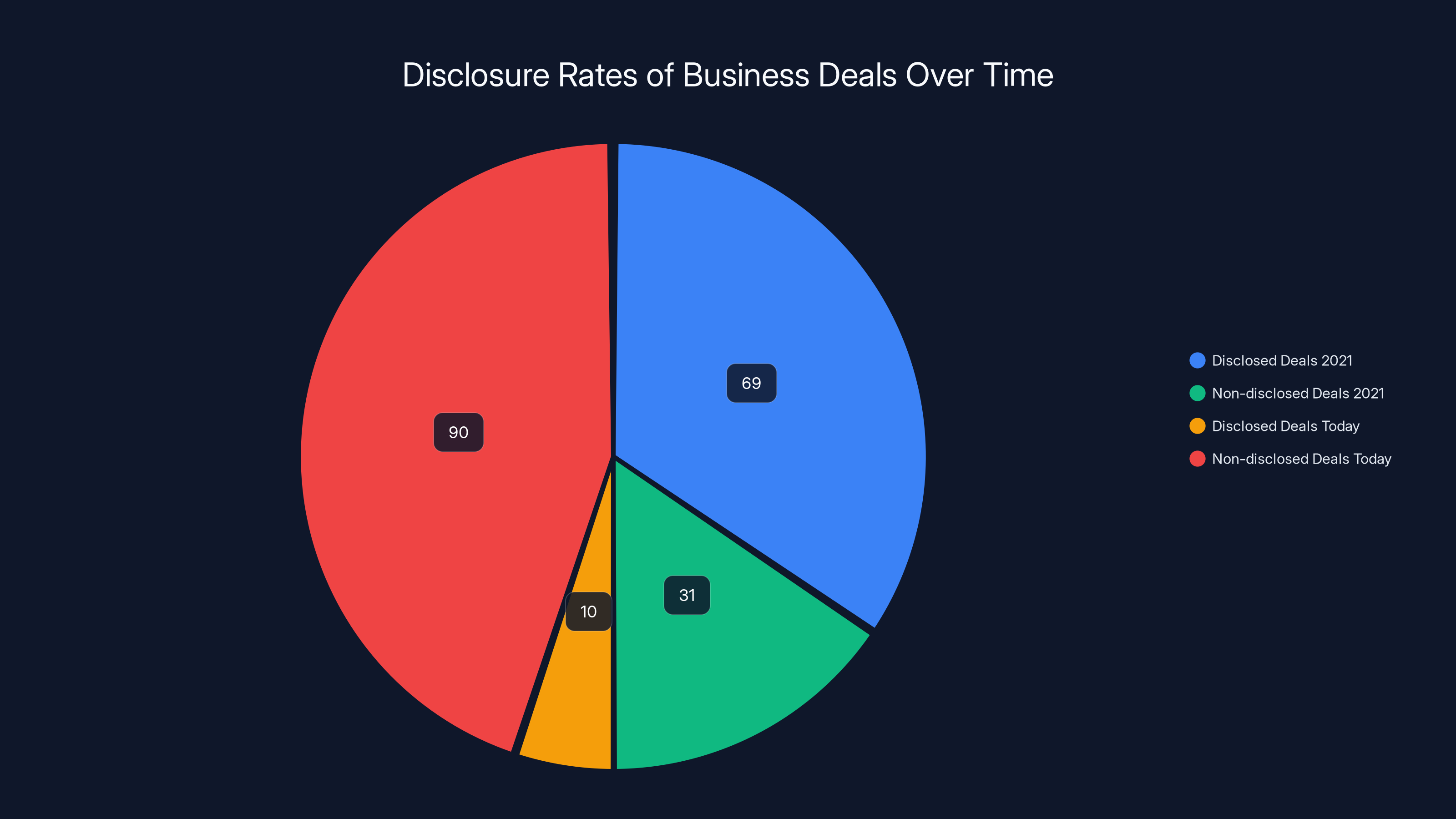

Yet at the same time, 90% of 2025 deals didn't disclose terms at all. That's up from 69% in 2021. So here's the uncomfortable reality you need to understand: most deals are staying silent. The only ones we have hard numbers on are increasingly likely to be disappointing.

Draw your own conclusions about what that silence means.

TL; DR

- Confirmed 3x+ returns collapsed from 22% (2021) to 7% (2025), a two-thirds decline in just four years

- 90% of 2025 deals are undisclosed, making true market performance impossible to assess

- The ratio of M&A to VC deals is climbing, reaching 8 per 100 VC deals (highest in seven years), but the quality of those deals is deteriorating

- VC-backed acquirers now represent 46% of all M&A, up from just 10% in 2015, shifting the entire ecosystem's power dynamics

- Silence signals risk: deals that don't announce their valuations are disproportionately likely to be acquihires or return-of-capital situations, not wins

- Your exit is real but harder, requiring stronger fundamentals, clearer strategic value, and better positioning than ever before

In 2025, only 7% of disclosed M&A deals achieved a 3x return, highlighting the rarity of such successful outcomes in the current market. Estimated data.

What the Data Actually Tells Us (And What It Doesn't)

Let's be precise about what we're looking at here, because the dataset itself is the story.

SVB Intelligence has been tracking M&A outcomes for years, breaking them down into four categories based on deal price relative to the total VC capital that company raised. Think of it as a multiplier: did founders and investors get back 3x their money, 1x-3x, less than 1x, or something in between?

The critical constraint is disclosure. SVB can only analyze deals where the price actually became public knowledge. And in 2025, that's just 10% of all deals.

Ninety percent stayed quiet.

That's a massive increase from 2021, when about 69% of deals disclosed their terms. Something fundamental shifted in the market's appetite for transparency.

Now, here's the question everyone asks: are the undisclosed deals just secret wins? Are founders quietly cashing out at huge multiples but keeping it under wraps?

Practically speaking, no. When Google pays $32 billion for a company, they announce it. The acquirer wants credit. The founders want the prestige. Investors want the win on their track record.

When a startup gets acquihired for

Silence, in M&A, usually means something went wrong.

But you can't claim with certainty that undisclosed deals are mostly acquihires. The data doesn't prove that. All it proves is that disclosed deals are getting worse, and fewer deals are disclosing at all.

That's signal enough.

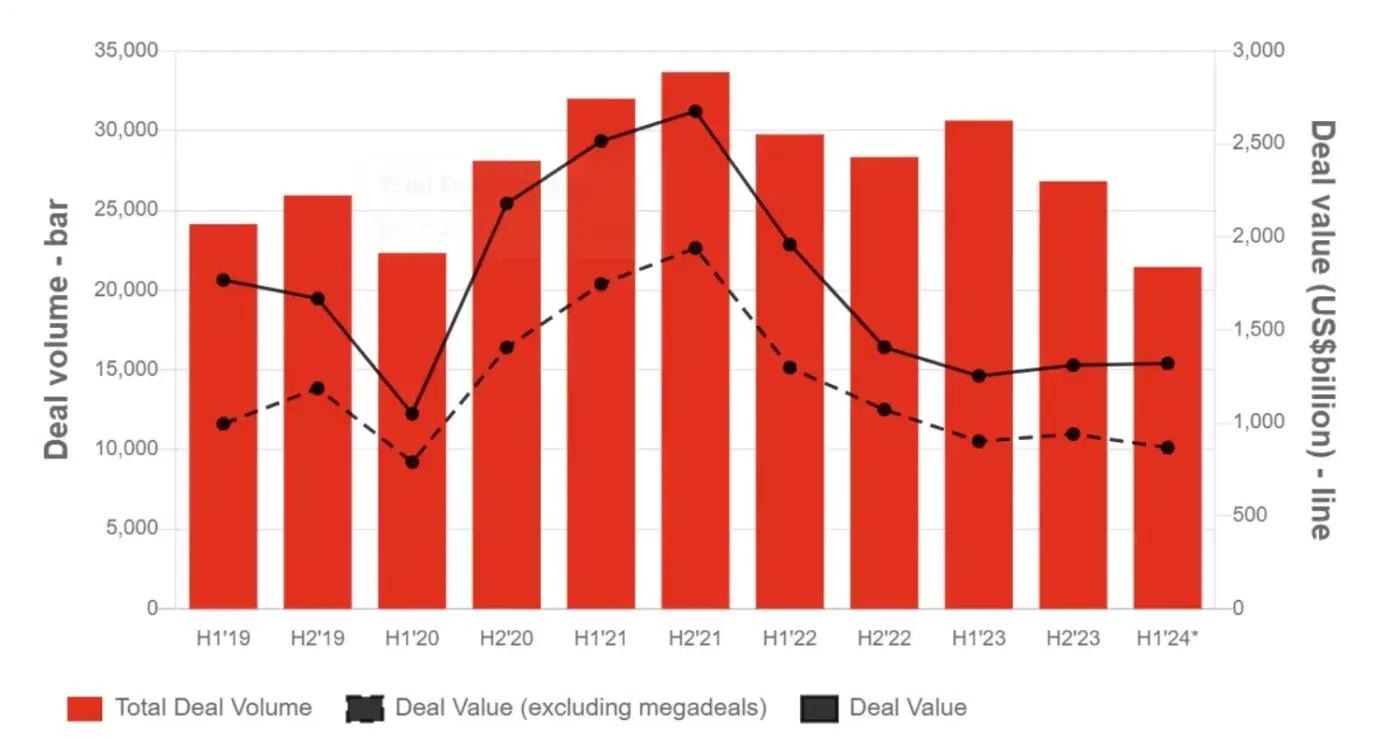

The Structural Shift: Why This Matters More Than Noise

Some people look at this and say: "Well, 7% is still a sample size. Maybe the undisclosed deals are actually good." Technically true. But when you zoom out, the trend is unmistakable.

In 2021, roughly 1 in 5 disclosed deals confirmed a 3x or better return. Today it's 1 in 14.

That's not statistical noise. That's a structural change in how M&A is working.

Think about what that implies for founders and investors. In 2021, if you made it to acquisition, there was a reasonable shot—a 22% shot—that you'd get a meaningful outcome. Not a guarantee, but real odds.

Today, those odds are worse than lottery tickets.

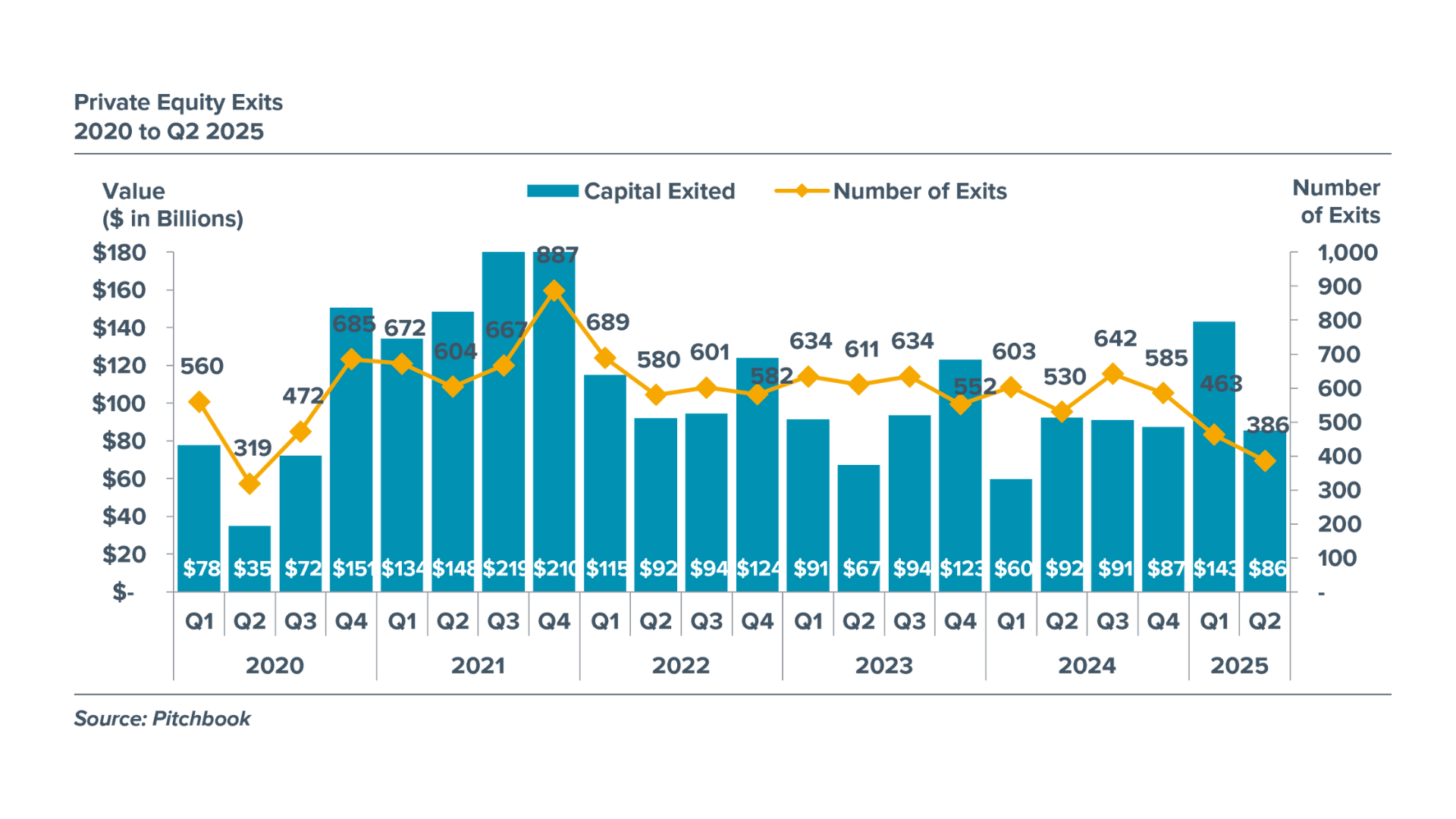

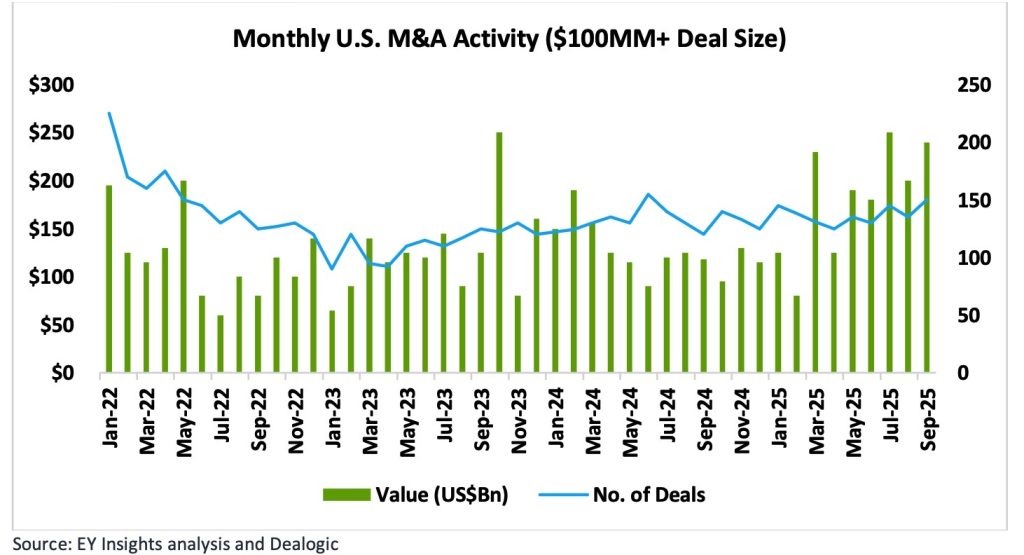

The reasons are layered. First, the macro environment for acquisitions has tightened. Companies are more conservative with capital. They're scrutinizing ROI on acquisitions more carefully. When they do acquire, they're more likely to structure the deal as a talent hire with deferred earnout provisions rather than an upfront cash payment. Earnouts are great for acquirers, terrible for founders and investors who need liquidity now.

Second, the definition of "strategic value" has narrowed. Three years ago, a company with a novel technology, solid growth, and a capable team could realistically get acquired at a 3x or 4x revenue multiple. Today, acquirers are more demanding. They want proven profitability, recurring revenue, zero churn, or some defensible moat they can't build themselves.

Third, the volume of VC-backed startups has exploded, which means the acquisition pipeline is oversaturated. When you have 50 companies competing to solve the same problem, acquirers can cherry-pick. The ones with weaker fundamentals get offered a down round or a salary package. The exceptional ones get the real money.

The middle class of exits is disappearing.

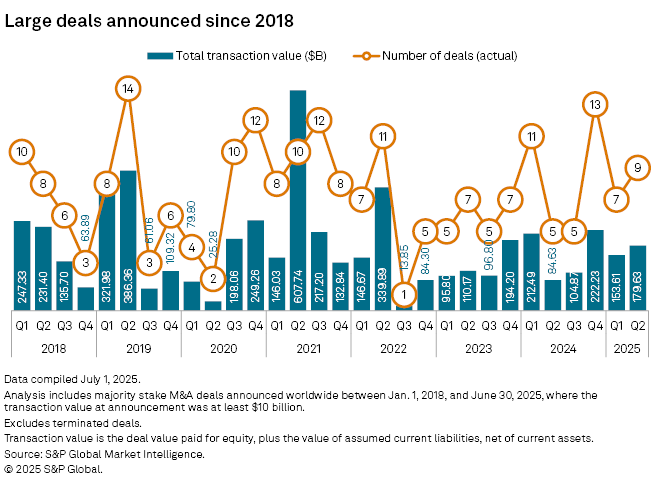

The Headline Deals: Why You Shouldn't Take Them as Proof

Now let's talk about the deals everyone knows. The Wiz deal. The Groq deal. The Service Now roll-ups.

These are real. The money is real. The outcomes are spectacular.

For the companies involved, M&A in 2025 has been transformative. Wiz became a $23 billion company through its exit. That's generational wealth for founders and early investors.

But here's the critical insight: these deals represent a thin slice of the market. They're outliers, not the mode.

For every Wiz, there are dozens of acquisitions nobody hears about. A Series B company gets acquired by a larger platform at a 0.8x revenue multiple. Founders get jobs. Investors get their money back minus fees and dilution. It's not a disaster. It's not a win. It's a shuffle.

The deals that make headlines are the ones where something exceptional happened: the company was growing at 300% Yo Y, had a clear path to profitability, or solved a problem so urgent that an acquirer had to pay up to get ahead of the competition.

Those deals do happen. But they're rare. And they're getting rarer.

What the headline deals do tell us is that strategic M&A is still valuable for certain companies. If you've built something defensible, you have a chance. But "chance" is the operative word. It's not a guarantee.

The rate of disclosed M&A deals has significantly decreased from 69% in 2021 to just 10% in 2025, indicating a shift in market transparency. Estimated data.

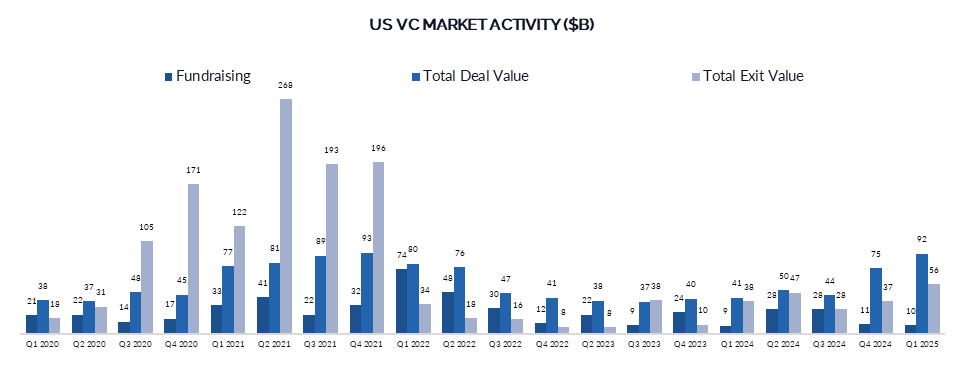

The Acquirer Revolution: Unicorns Eating Unicorns

Here's what's actually fascinating and gets overlooked in most analysis: who's buying has fundamentally changed.

In 2015, if a startup got acquired, the acquirer was usually a public company or a well-established enterprise firm. IBM buying Red Hat. Microsoft buying Linked In. Salesforce buying Slack. These were trophy acquisitions by established players.

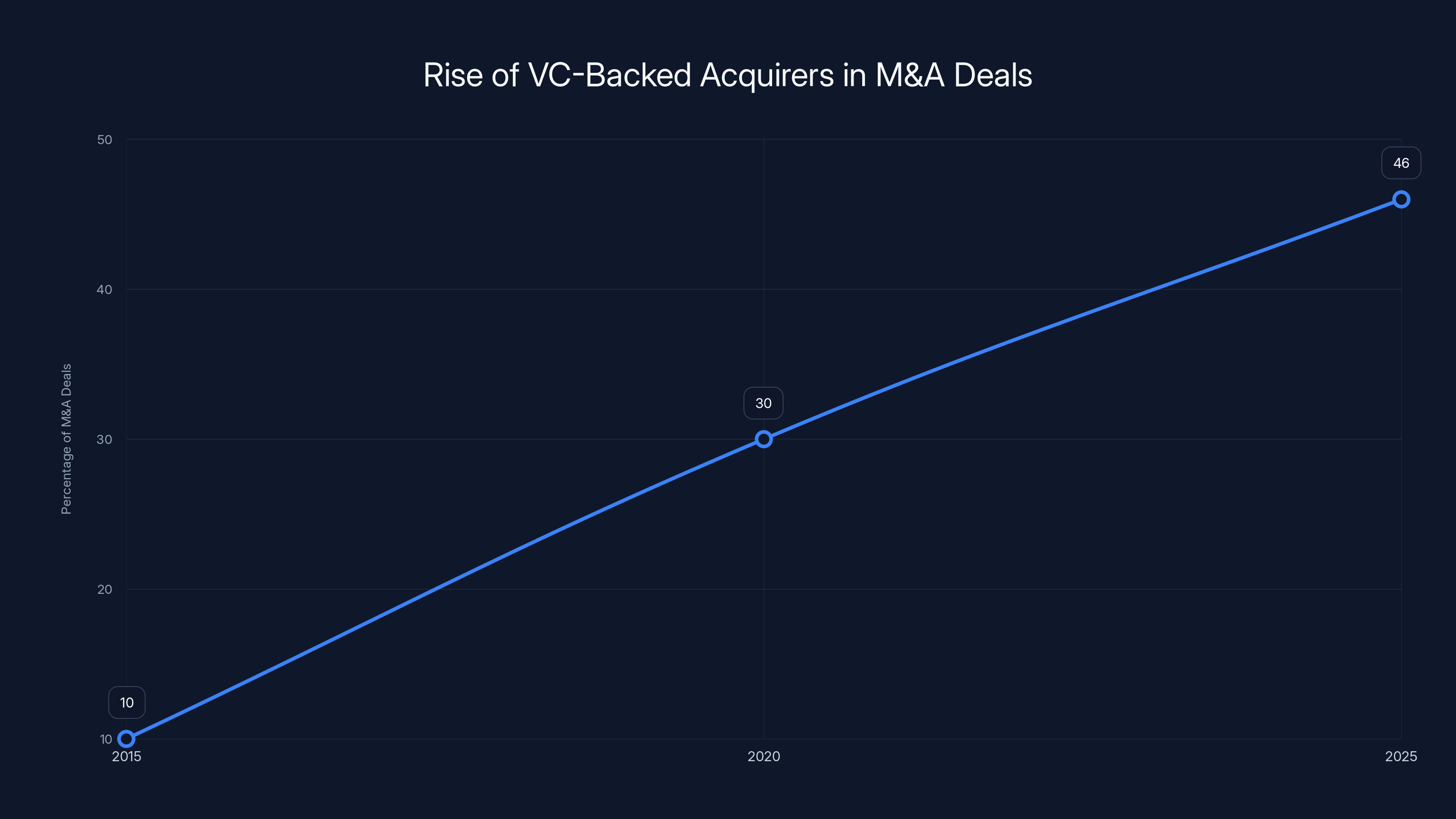

Today? 46% of M&A deals in 2025 have a VC-backed company as the buyer. That's up from just 10% a decade ago.

The unicorns are acquiring the unicorns.

Databricks has done 17 acquisitions. Stripe has been on an aggressive acquisition spree. Figma, Canva, and other juggernauts are systematically buying competitors and smaller players in adjacent markets.

Grub Market has done 17 acquisitions as part of a systematic consolidation strategy in the grocery supply chain.

This is fundamentally different from the old M&A playbook. When a VC-backed company buys another VC-backed company, the dynamics change. The acquirer is optimizing for growth, not synergy. They're often rolling up a fragmented market rather than looking for a strategic fit.

For founders being acquired by another VC-backed company, that can be good news or terrible news depending on the deal structure.

Good news: VC-backed acquirers understand founder psychology. They move fast. They might keep you in operational control. They might offer equity upside if the combined entity does well.

Terrible news: VC-backed acquirers are often stretched for cash and overgeared. That "equity upside" might never materialize. They might integrate your product aggressively, bleed your team, and then walk away after 18 months. And because the acquirer itself is VC-backed, when economic conditions tighten, the whole thing can come apart.

The shift toward VC-backed acquirers also concentrates power. A handful of mega-valued companies (Databricks, Stripe, Figma) are buying up competitors and adjacent players. The winners in this ecosystem are becoming more concentrated.

For founders, that means your potential acquirer base is actually shrinking, even though there are more total M&A deals happening.

Why 90% of Deals Don't Disclose (And What That Silence Costs You)

The explosion in non-disclosure is a story in itself.

In 2021, roughly 69% of deals disclosed. That means 31% stayed quiet. Today it's flipped: only 10% disclose.

Why the sudden shift to secrecy?

Part of it is legal. Companies are more cautious about antitrust scrutiny. Tech acquisitions face regulatory review now. Smaller deals that might've been announced five years ago now get buried to avoid attention.

Part of it is financial. If you're an acquirer buying a company at a down round (below previous valuation), you don't want that information leaking to the market. It signals weakness in your judgment. So you hide the deal under confidentiality agreements and move on.

Part of it is psychological. Founders and investors don't want to explain outcomes that disappoint them. A Series C company that raised at

Part of it is competitive. If you're acquiring a competitor, you might not want customers or employees to know the acquisition happened. You want to absorb the company quietly, migrate the customers, and avoid disruption.

The result is an information vacuum. We only have hard data on 10% of deals, and that 10% is increasingly negative. The 90% we don't know about could be better or worse, but the fact that nobody's talking suggests it's not good.

For founders evaluating a potential acquisition offer, this silence is a warning sign. If the acquirer is pushing for confidentiality before you even agree in principle, that's suspicious. Reputable buyers of real value usually want some level of transparency. They're proud of the acquisition.

Secrecy protects the acquirer, not you.

The Economics of Acquihires: Why Silence Makes Sense

Let's talk directly about what a lot of these quiet deals probably are: acquihires.

An acquihire is when a company buys another company primarily to hire its team, not to acquire its product or technology. The acquirer typically pays less than what the acquired company's investors put in. The founders might negotiate personal packages (salaries, retention bonuses) that look good short-term. But the investors often take a loss or break even.

Acquihires have become incredibly common in tech, especially in AI and infrastructure. You build a team, it gets traction, another well-funded company decides it wants your team more than your product, and they buy you for that reason.

For the acquirer, an acquihire is efficient. Hiring engineers in San Francisco or New York costs

For founders, acquihires can actually be okay if you negotiate well. You get a job, usually with acceleration of your equity, some retention bonus, and you get to work on a company with more resources.

For investors, acquihires are a loss. You put in

That's why acquihires are quiet. Nobody wants to broadcast that outcome.

And if 90% of deals are quiet, and the disclosed ones are returning 3x only 7% of the time, it's reasonable to infer that acquihires and marginal outcomes make up a significant chunk of the market.

That's not conspiracy theory. That's just math.

The Geographic and Sector Concentration

Here's another layer: M&A isn't evenly distributed across sectors or geographies.

AI and infrastructure companies have seen massive acquisition activity. That makes sense—every established company wants AI capabilities, and the fastest way to get them is to buy a team or a technology.

Biotech and healthcare M&A is also robust. Regulatory barriers make those markets more consolidation-friendly.

But enterprise Saa S, once the heartbeat of acquisition activity, has cooled significantly. There's less consolidation among mid-market Saa S companies. The winners are consolidating, but the middle tier is increasingly stuck.

Geographically, M&A remains heavily concentrated in the US and Western Europe. Founders in emerging markets face an even thinner acquisition pipeline.

For you as a founder, this means your odds of getting acquired depend heavily on what you built and where. If you're building AI infrastructure in San Francisco, you've got options. If you're building B2B Saa S in emerging markets, your potential acquirer base is smaller.

That concentration of opportunity is creating winners and losers at the ecosystem level.

The percentage of M&A deals involving VC-backed acquirers has increased from 10% in 2015 to an estimated 46% in 2025, highlighting a significant shift in acquisition dynamics. (Estimated data)

The Earnout Problem: Why "Announced Valuations" Lie

Here's a dirty secret in M&A that the headlines rarely mention: announced deal values often aren't what actually gets paid.

When a company announces acquisition for "$500 million," that often breaks down like this:

The headline says

Earnouts are heavily weighted in favor of acquirers. They incentivize you to stay and perform, but they're also a way for the acquirer to reduce their actual cash outlay.

When deals are disclosed, the headline number is often the full value including earnouts. The actual upfront payment is often 60-70% of that.

This is another reason silence might be increasing. If you're getting acquired for announced "

For founders evaluating an acquisition, insist on understanding the earnout structure. That's where real disputes happen. An earnout that requires hitting growth targets with an acquirer that doesn't prioritize your product is a ticking time bomb.

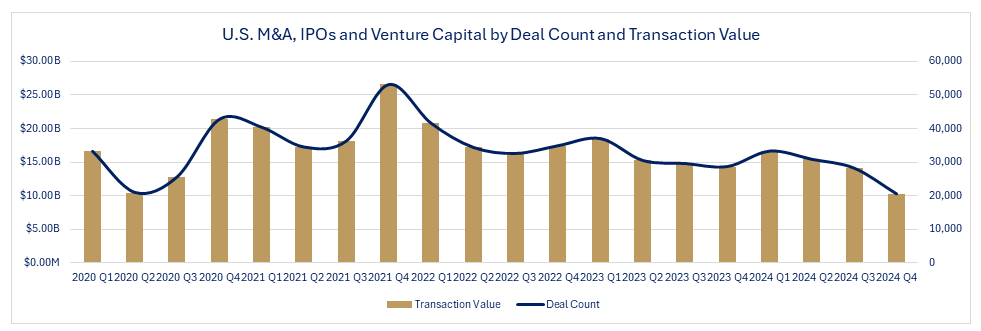

The IPO Alternative: Why Some Founders Are Opting Out

Given the collapse in acquisition returns, some founders have started asking: why get acquired at all?

If the median acquisition outcome is mediocre, and taking a company public is still possible (even if it's harder), shouldn't more founders just stay independent and build long-term value?

It's a fair question. And a few companies are choosing this path.

The challenge is that going public is not actually easier in 2025 than 2019. IPO volume is down. Valuations are being compressed. The bar for profitability is higher. And frankly, fewer founders want to manage a public company when they could just sell and move on.

But for founders with unit economics that actually work, with reasonable paths to profitability, staying independent is increasingly attractive.

The Stripe example is instructive. Stripe has been acquisition-resistant. They've raised at high valuations from top-tier VCs, they've achieved massive scale, and they're reportedly considering a path to profitability and IPO rather than accepting an acquisition from a larger player.

Stripe probably couldn't be acquired for what VCs think it's worth anyway. So they have leverage.

Most founders don't have that leverage. But the lesson stands: if your company is strong enough, M&A isn't your only path. You might have optionality.

What This Means for Your Exit Strategy

Okay, so the data is pretty stark. Only 7% of disclosed deals return 3x or more. Most deals don't disclose. The acquirer base is shifting toward VC-backed companies. Earnouts are eating into real payouts.

What should you actually do with this information?

First, stop anchoring your company valuation to headline acquisition prices. That Wiz deal at $23 billion is inspiration for a few dozen founders. It's not a baseline for the other 100,000 startups in the ecosystem.

Second, understand that if you get acquired, the deal structure matters as much as the headline number. Work with an experienced M&A lawyer who understands earnout risk. Negotiate for as much cash at close as possible. Earnouts are risk transfer to you. The acquirer is saying, "We don't have enough confidence in the combined business to pay you now."

Third, get multiple offers if you can. The only way to improve deal economics is to create competition among acquirers. One offer is not a negotiation. Three offers creates leverage.

Fourth, understand what an acquirer actually wants. If they want your team, they'll probably try to structure the deal that way. If they want your technology, they'll emphasize that. If they want your customer relationships, that matters. Knowing their real motivation lets you negotiate around it.

Fifth, consider your alternatives. If you have a path to IPO, or a path to meaningful profitability, or a path to being acquired by a strategic buyer (not another VC-backed startup), those options might have better outcomes than a discount acquisition.

Sixth, think about retention and team. When you get acquired, your team either stays with the new company or leaves. If key people leave, the deal value often erodes because the acquirer was buying the team. Negotiate retention packages that keep people motivated.

The Role of VCs in Declining Returns

Here's something worth saying directly: VCs have some responsibility for declining exit returns.

When you have a venture market where $1 billion-plus valuations are common for Series A companies, and the same market has a limited number of acquirers with sufficient capital to buy those companies, you get a supply and demand problem.

VCs have inflated the valuations of companies during fundraising. Series A companies raised at $200-500 million post-money valuations that don't make sense from a revenue perspective. That means when those companies get acquired, the acquisition price often doesn't match the investor expectations set during fundraising.

Acquirers look at that mismatch and either walk away or offer an aggressive earnout structure that pushes the real value lower.

VCs also concentrate ownership among a few mega-funds, which means when you're raising, you're often raising from someone who also owns 1-5 other companies in your space. That creates conflicts of interest around acquisition timing. If the mega-fund owns Company A and you're Company B, the mega-fund might prefer an acquisition that benefits Company A, not you.

The venture market has become increasingly about creating exits at any price, rather than building companies for durable value. That's a structural problem that's going to persist until the incentives change.

Estimated data suggests that 90% of tech acquisition deals are quiet, with only 7% achieving 3x returns, highlighting the prevalence of acquihires and marginal outcomes.

International M&A: Different Rules, Same Problems

M&A outside the US operates by different rules, with different challenges.

In Europe, regulatory scrutiny around acquisitions is higher. Data privacy, labor laws, and antitrust concerns mean European deals move slower and face more scrutiny.

In Asia-Pacific, M&A is growing but remains dominated by a smaller set of acquirers. The acquisition prices are often lower because the potential acquirer base is smaller.

In emerging markets, M&A is relatively rare. Most startups in those regions depend on venture capital for growth, not acquisition, because there aren't enough large acquirers with capital to buy them.

For international founders, this matters. Your potential acquirer base is smaller. Your negotiating leverage is lower. Your outcomes are more likely to be compressed.

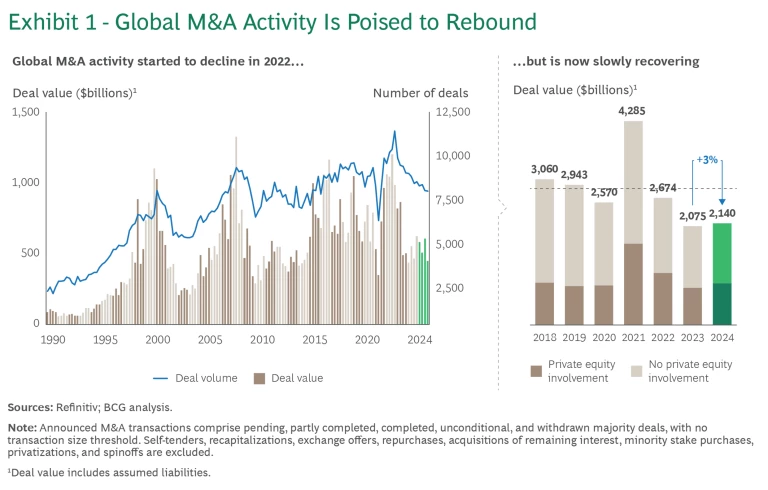

The global M&A collapse isn't uniform. But it's real enough in most geographies.

The AI Exception: Why Some Sectors Are Still Hot

One thing that breaks the overall trend: AI infrastructure and AI application companies are still getting acquired at robust valuations.

Why? Because every large company—Google, Microsoft, Apple, Meta, Amazon—is in an arms race for AI capabilities. They'd rather acquire an AI-native startup than build from scratch.

If you're building in AI, your acquisition prospects are actually better than they've been in years.

But that advantage is time-limited. As AI infrastructure commoditizes, and more large companies build their own AI capabilities, that premium pricing disappears.

Founders building in AI should understand this is a temporary window. The next 18-24 months are probably your best shot at a premium acquisition. After that, the market will be more crowded and the acquirer desperation will fade.

Timing Your Exit: The Hardest Decision

There's no perfect time to exit, but there are better and worse times.

Right now, the macro environment is recovering but uncertain. Tech stocks are up. Corporate spending is returning. But valuations are not back to 2021 levels, and they won't be.

If you have a company that's generating revenue, growing, and profitable, you're in a strong position to command better acquisition terms.

If you're pre-revenue or barely growing, your exit options are limited. You either keep raising venture capital, or you take whatever acquisition offer comes.

The timing question is really about this: how much optionality do you have? If you can operate for 24 more months without raising capital, you have optionality. You can be selective about which acquirer you work with. You can wait for the right offer.

If you need capital now, you have less optionality. Your acquirer base shrinks to whoever will finance your next phase of growth.

Optionality is worth enormous amounts of money in M&A. Figure out how to buy it.

The Future: Will Acquisition Returns Recover?

The honest answer is: probably not to 2021 levels, at least not in the near term.

Here's why. The venture market has undergone a structural reset. Companies that raised at inflated valuations in 2020-2021 are either scaling into those valuations or dying. Acquirers got burned on a few bad acquisitions (Elon buying Twitter for $44 billion and losing half the company's value is the extreme example, but there are more modest versions). They're being more conservative.

Third, the acquirer base isn't growing fast enough to absorb the supply of VC-backed companies. There are more startups than ever, but acquisition appetite is actually declining.

Fourth, public market valuations are more rational. When public company stock is trading at 15x revenue instead of 50x revenue (2021 levels), the acquirers' cost of capital is higher. They can't justify aggressive acquisition pricing anymore.

All of that suggests acquisition returns will stay compressed for at least the next 2-3 years.

But there are countervailing factors. As more VC-backed companies consolidate, they'll have cash to make acquisitions. That could create a new wave of M&A activity. If the macro environment stays strong, corporate M&A budgets will be more robust.

But we're probably not going back to a world where one-in-five acquisitions return 3x or more. That was an anomaly of cheap capital and booming public markets. This is the new normal.

Acquisition returns are projected to remain below 2021 levels, with a gradual recovery expected over the next few years. Estimated data based on current market conditions.

Lessons from Recent Mega-Deals

Let's extract what we can learn from the biggest recent acquisitions.

Wiz (

Groq ($20 billion Nvidia acquisition): Groq built specialized AI chips. Nvidia wanted to own the full stack and eliminate a competitor. This was less about Groq's cash flow and more about Nvidia's strategic necessity. Lesson: if you're solving a problem a giant company absolutely needs to own, you have leverage.

Windsurf ($2.4 billion): Google essentially paid to hire the founding team and license their technology. This is a modern acquihire at mega-scale. Lesson: if your team is exceptional, you can command premium pricing even if your product isn't fully proven.

Service Now's $20 billion in acquisitions: Service Now is systematically buying companies to fill gaps in their platform. Each acquisition is smaller, but the cumulative effect is consolidation. Lesson: when a platform company is on an acquisition spree, being acquired by them means integration risk but also potential for scale.

None of these deals are replicable by typical founders. But they show that extreme outcomes are still possible if you hit certain conditions.

Negotiating Better M&A Terms

If you're in acquisition conversations, here are concrete things to negotiate for:

Cash at close: Push for 75%+ of the deal value to be paid at closing. Earnouts are risk. You take on the risk of hitting milestones with an acquirer that might not prioritize your product.

Retention packages: Structure equity acceleration so that key team members stay engaged. If your team leaves post-acquisition, the deal value erodes.

Defined milestones for earnouts: If you do have earnouts, make sure the milestones are under your control, not the acquirer's discretion. "Hit $10M ARR by end of year" is good. "Hit revenue targets we haven't specified yet" is bad.

Non-compete agreements: Don't agree to non-competes longer than 1-2 years. You need to be able to go do something else.

Management continuity: If you're staying with the company, get clarity on your role. If they're replacing you as CEO, get that in writing. Don't let them promise one thing at close and change it after.

Tax treatment: Work with a tax lawyer to understand the implications of the deal structure. Sometimes structure can be adjusted to be more tax-efficient.

Data and IP: If the acquirer is buying your technology, make sure all IP is clearly transferred and documented. Don't leave loose ends.

The Broader Ecosystem Impact

These declining exit returns have ripple effects through the venture ecosystem.

VCs are getting more conservative about which companies they fund. The bar for follow-on investment is higher. Mid-stage companies with decent traction but not-exceptional growth are struggling to raise Series C at any valuation.

Less capital flowing to startups means fewer new companies starting. The founder pipeline is tightening.

Founders are questioning whether VC-backed startups are even the right path. More are choosing to bootstrap or raise angel capital and stay independent longer.

The whole ecosystem is recalibrating around the reality that exits are harder and returns are lower. That's healthy in some ways—it makes capital allocation more rational. But it also means the golden age of easy venture capital is genuinely over.

When Not to Pursue M&A

Here's something nobody says enough: sometimes the best path forward is not acquisition.

If you have a company that's actually profitable, with recurring revenue, and sustainable growth, why get acquired? Why take a 3x multiple when you could build a 10x business over ten years?

If your company is generating $10 million in annual profit and can reinvest for growth, that's a business worth keeping.

The problem is most VC-backed companies are structured to be acquired, not to be profitable operating businesses. They're taking on VC capital expecting to cash out, not expecting to build indefinitely.

But founders should ask themselves: do I need VC? Or do I just need enough capital to get to profitability and then optimize from there?

For the right founder with the right business, the answer might be "skip acquisition altogether."

In 2021, 69% of deals were disclosed, but today only 10% are. This shift towards non-disclosure highlights increasing secrecy in business transactions.

What Acquirers Actually Care About

When an acquirer evaluates your company, they're looking at:

Revenue and growth rate: Are you growing and is it sustainable? What's your CAC and LTV?

Customer concentration: Are 80% of your revenues from three customers (bad) or are they diversified?

Churn: Are customers staying or leaving? Negative churn is gold. High churn means the acquisition value is limited.

Team: Is your team exceptional or just okay? Can they execute post-acquisition?

Technology and IP: Is your technology actually defensible or is it quickly replicable?

Culture and values: Will your company's culture clash with theirs? That affects integration success.

Strategic fit: How well does your product fit into their platform? Is it a natural adjacency or a stretch?

Competitive threat: Are you a threat they need to neutralize, or a complement?

Acquirers rarely care about your vision or mission. They care about cash flow impact and strategic fit. Pitch accordingly.

Red Flags in Acquisition Conversations

Some warning signs that should make you cautious:

Demanding secrecy before terms are set: They want to avoid competition. That suggests they know what they're willing to pay and don't want you to shop it around.

Aggressive earnout structure: If 60%+ of the deal is earnouts, they don't have confidence in the business. Why would you?

Changes in leadership post-announcement: If the CTO or CEO you negotiated with suddenly leaves, renegotiate.

Slow integration planning: If they don't have a detailed plan for how they'll integrate your product, they might not know what they're buying.

Pressure to accept quickly: Real buyers will move fast but they won't panic. Panic usually means they're worried about something.

Vague earnout milestones: If the earnout is tied to metrics they won't define, assume you won't hit them.

Trust your instincts. If something feels off, it probably is.

Building for Acquisition (If That's Your Goal)

If you are actually trying to optimize for acquisition, here's how to think about it:

Find an acquirer's pain point and solve it: Don't build a product for market. Build a product that specifically solves a problem one acquirer desperately needs solved. Then be acquired by them.

Build technology they can't easily build themselves: If you can make something that would take them 18 months to build, you're valuable.

Create a team they need: Recruit people they'd love to have. Become a talent magnet.

Get customers of theirs: If you can help a big company's customers solve a problem, you're strategic.

Grow fast and predictably: Show 50%+ quarter-over-quarter growth. Predictability matters as much as growth rate.

Get to unit economics that work: An acquirer will stress-test your CAC and LTV. Have answers.

Build towards a specific exit: Start with your target acquirer in mind. What would they value? What would they want to acquire?

This is the opposite of "build for the market." It's "build for your acquirer." Both are valid strategies. Just pick one.

The Remote Work Effect on M&A

One subtle factor in declining acquisition returns: remote work has made it easier for companies to stay distributed and harder to justify expensive acquisitions.

When you had to be in the same office, acquiring a team made sense for geographic consolidation. Now? You can hire the team remotely and they can work anywhere.

That reduces the "must acquire to hire" impulse that used to drive some M&A.

It also means founders have more leverage to stay independent. You don't need to be acquired to access talent or scale. You can hire globally from anywhere.

This is a subtle but real factor in why acquisition returns are declining.

Preparing for Due Diligence

If acquisition conversations progress, you'll enter due diligence. Here's what to prepare for:

Financial records: Have clean books. Document every expense. Have audited statements if possible.

Customer contracts: Pull every contract. Document revenue recognition. Show any contracts with unusual terms.

Employee agreements: Have all employees on clear employment agreements. No ambiguous equity awards.

IP documentation: Prove you own your technology. Document developer agreements. Get assignments from any contractors.

Regulatory compliance: Have clean records on GDPR, CCPA, SOC 2, whatever applies to your business.

Litigation and disputes: Disclose anything. Acquirers will find it anyway. Better to disclose than be surprised.

Related-party transactions: If you've done business with founders or board members, document it clearly.

Board minutes: Have organized records of all board meetings and decisions.

Legal opinions: Have a corporate lawyer review everything. Get an opinion letter on capitalization and governance.

Due diligence is where deals die. Prepare properly.

The Role of Advisors and Brokers

Some founders hire M&A advisors or investment bankers to run acquisition processes. That can be helpful or unhelpful depending on who you hire.

Good advisors have relationships with potential acquirers and can create competitive tension. They understand deal structures and can negotiate better terms.

Bad advisors are mercenaries. They'll push you to accept the first offer for quick fees. They don't care about your outcome.

If you hire an advisor, make sure they have a track record in your space. Make sure they're getting paid on success (percentage of deal value), not just to run the process. And make sure they're contractually obligated to work in your interest, not just push any deal.

Advisors can add 10-20% in deal value if they're good. They can also cost you 20% if they're bad. Choose carefully.

After the Acquisition: Managing the Transition

If you get acquired, the real work starts. Here's how to think about it:

Your first 90 days set the tone: Come in with a plan to integrate quickly. Show you can operate within their systems.

Maintain team: Your team will want to leave. They're looking for any signal that the acquisition is a mistake. Keep them engaged with clarity about their role and options.

Find your champion within the acquiring company: You need someone on the inside who believes in what you're doing. Cultivate that relationship.

Over-communicate: Things change post-acquisition. Founders often feel blindsided. Communicate constantly about decisions and direction.

Push for autonomy: You want to maintain your product identity and culture as much as possible. Push for that.

Document the earnout: If you have earnouts, document exactly what you're hitting. Track metrics obsessively.

Plan your next move: Assume you're going to leave 18-36 months after acquisition. Start thinking about what's next.

Many acquisitions destroy value post-close. Founders and teams leave. Products get killed. It doesn't have to be that way, but you have to actively manage it.

The Contrarian View: Maybe Lower Returns Aren't So Bad

Here's a perspective worth considering: maybe declining acquisition returns are actually healthy for the ecosystem.

When acquisition returns were 22%, you had a lottery system. Most startups failed, some got modest exits, and a tiny few hit the jackpot. That created a feast-or-famine dynamic.

Now, with more measured returns and more disclosure, you're seeing a more realistic picture. Startups that build real value get acquired. Those that don't, fail or get acquired as acquihires.

That's more efficient. It means capital is being allocated to companies that actually solve real problems, not just hype.

It also means founders have to build real businesses, not just burn capital and hope to get lucky.

That's harder. But it's also more honest.

So in some sense, the collapse in acquisition returns is a feature, not a bug. It's the market correcting for irrational exuberance.

Key Takeaways for Founders

If you're running a company and thinking about acquisition:

-

Understand that 7% of disclosed deals return 3x or more. That's not good odds. But those deals do happen.

-

90% of deals don't disclose terms. Silence usually means the deal wasn't great.

-

Build your company for optionality. The more independent you are, the better your negotiating position.

-

Get multiple offers. One offer is not negotiation. Three offers is leverage.

-

Understand earnout risk. They're risk transfer to you. Minimize them.

-

Find an acquirer who desperately needs what you've built. That gives you leverage.

-

Your team is often the most valuable asset. Negotiate retention carefully.

-

Consider alternatives to acquisition. IPO, staying independent, or building for profitability might have better outcomes.

-

Prepare thoroughly for due diligence. Surprises kill deals and kill deal value.

-

Remember that the headline number isn't what you actually get. Understand the full financial structure.

Conclusion: The New M&A Reality

M&A is not dead. Big deals are still happening. Strategic acquisitions still create enormous value for founders and investors.

But the fantasy of 3x returns for most founders is gone. That was 2021. This is 2025.

The market has reset. Acquirers are more selective. Deal structures are more complex. Earnouts are the norm. Silence is more common than transparency.

For founders building in this environment, that means a few things have to change in how you think about exits.

First, build a real business. Revenue, growth, customer retention, unit economics that work. That's what acquirers actually care about.

Second, understand your potential acquirer base. Who would actually benefit from buying what you've built? Start those conversations early, not at the end when you're desperate.

Third, develop optionality. The better your independent business can function, the stronger your negotiating position in an acquisition.

Fourth, don't anchor to headline acquisition prices. The Wiz deal is an outlier. Price anchor to disclosed deals in your space that are more relevant.

Fifth, if you do get acquired, negotiate hard on the terms. Cash at close, earnout structures, retention packages, post-close autonomy. Every point matters.

Sixth, consider alternatives. Maybe you don't want to get acquired. Maybe staying independent and building a sustainable business has better outcomes.

The M&A market will evolve. It always does. Maybe acquisition returns recover in three years. Maybe they don't. Either way, the founders who win are the ones who build real value, negotiate intelligently, and maintain optionality.

That's the new M&A reality. It's harder than the 2021 fantasy. But it's more sustainable. And it rewards the founders who actually build things people want.

FAQ

What does a 3x return mean in M&A context?

A 3x return means the acquisition price is three times the total venture capital that was invested in the company. For example, if a company raised

Why are 90% of M&A deals not disclosing their valuations?

Companies avoid disclosing acquisition valuations for several strategic and psychological reasons. If an acquisition happens at a down-round valuation (below previous funding rounds), announcing it signals investor disappointment. Acquirers may keep quiet about acquisitions to avoid antitrust scrutiny or competitive consequences. Founders want to avoid explaining outcomes that disappoint investors. Additionally, many acquihires or talent acquisitions are sensitive because the acquirer got talent at a discount, and the investors took losses they'd prefer to hide.

What's the difference between an acquisition and an acquihire?

An acquisition is when a company buys another company for its product, technology, customer base, or market position. An acquihire is when a company buys another company primarily to hire its team and talent, often without caring much about the product. In acquihires, the acquirer typically pays less than the total VC investment in the acquired company, and founders often negotiate personal salary packages to compensate. Most early-stage founders don't want to admit they got acquihired because it signals the product didn't have sufficient market value.

How much of an acquisition deal price should be paid at closing versus as earnouts?

Industry standards typically involve 60-75% of the deal price being paid as cash at closing, with the remainder as earnouts paid over 2-3 years if the company hits specific milestones. However, you should push to maximize cash at close because earnouts are risky. If the acquirer changes strategy, loses interest in your product, or the company performs poorly overall, you might never receive the earnout amount. Every percentage point of earnout is risk you're transferring to yourself, while the acquirer reduces their actual cash outlay.

What should a founder focus on to improve acquisition odds and valuation?

Founders should focus on building sustainable unit economics (favorable CAC and LTV ratios), demonstrating predictable revenue growth of 40-50% quarter-over-quarter, achieving high customer retention with low churn, building defensible technology or moats, assembling a strong team that potential acquirers would want to hire, and diversifying the customer base so no single customer represents more than 10-15% of revenue. Additionally, understanding your potential acquirers and building relationships early, and maintaining operational independence so you can operate without raising more capital, strengthens your negotiating position.

Why do VC-backed acquirers represent such a large portion of M&A now?

VC-backed companies like Databricks, Stripe, Figma, and others have achieved massive scale and valuations, giving them sufficient capital and share-based currency to make acquisitions. These companies view M&A as roll-up strategies to consolidate fragmented markets, acquire competitors, and add adjacencies to their platforms. A VC-backed acquirer typically understands founder incentives and may offer better integration and autonomy than larger corporations. However, VC-backed acquirers are often capital-constrained and highly leveraged, making earnout-heavy deals more likely than all-cash acquisitions.

Should a founder try to get acquired or pursue IPO instead?

The answer depends on your company's fundamentals and optionality. If your company has clear paths to profitability, genuine sustainable growth, and recurring revenue, and if you have runway to operate independently, you have real optionality to stay independent longer or pursue IPO. IPO typically requires $100+ million in ARR and consistent profitability, so most startups will be acquired first. However, if acquisition terms are poor (high earnouts, low valuation multiples), and your company can sustain itself independently, staying private and building toward profitability or IPO has become a more viable alternative than accepting unfavorable acquisition terms.

What is the impact of earnout structures on actual founder proceeds?

Earnouts can dramatically reduce what founders actually receive. An announced deal of

How has AI acquisition activity differed from other sectors?

AI companies have bucked the broader trend of declining acquisition returns. Every major technology company (Google, Microsoft, Meta, Apple, Amazon) is in an arms race for AI capabilities, making them willing to pay premium prices to acquire AI infrastructure and application companies. Companies like Groq, Windsurf, and others have achieved significant acquisition valuations in the past 18 months. However, this AI premium is likely temporary. As AI infrastructure commoditizes, more large companies build their own capabilities, and competition increases, acquisition valuations in AI will compress to match other sectors. Founders building in AI should recognize this is a limited window and optimize for exits in the next 18-24 months.

What role do M&A advisors and investment bankers play in improving deal outcomes?

Good M&A advisors bring industry relationships that create competitive tension among potential acquirers, understand deal structures and tax implications, and can negotiate terms that are 10-20% more favorable than founders would achieve alone. Bad advisors are incentivized to close any deal quickly for their fees, regardless of whether it's optimal for founders. When hiring an advisor, ensure they have a track record in your specific industry, that their fee is tied to deal success (percentage of enterprise value), and that they're contractually obligated to represent your interests. Also make sure the advisor understands earnout and tax implications deeply, as these areas frequently determine whether a deal is actually good or just looks good on paper.

![M&A Deals Collapse to 7% 3x Returns: What This Means for Your Exit [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/m-a-deals-collapse-to-7-3x-returns-what-this-means-for-your-/image-1-1768048602878.jpg)