Introduction: When Tech Platforms Become Political Gatekeepers

In early 2025, something unusual happened on Meta's platforms. Users trying to share links to a website called ICE List found their posts mysteriously disappearing. No warning. No explanation. Just gone.

ICE List claims to maintain a database of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) employees, specifically Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. The site was created by activists who argue transparency about government agents is essential for accountability. But Meta decided otherwise, blocking the links across Facebook, Instagram, and Threads while leaving WhatsApp unblocked. According to Wired, this decision reflects a broader debate about the power of tech companies over political speech.

This isn't just another content moderation decision. It sits at the intersection of three massive debates happening right now: what power should tech companies wield over political speech, how should platforms balance safety concerns with free expression, and who gets to decide what information citizens can access?

Here's what happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about where content moderation is heading.

The ICE List Controversy: Background and Context

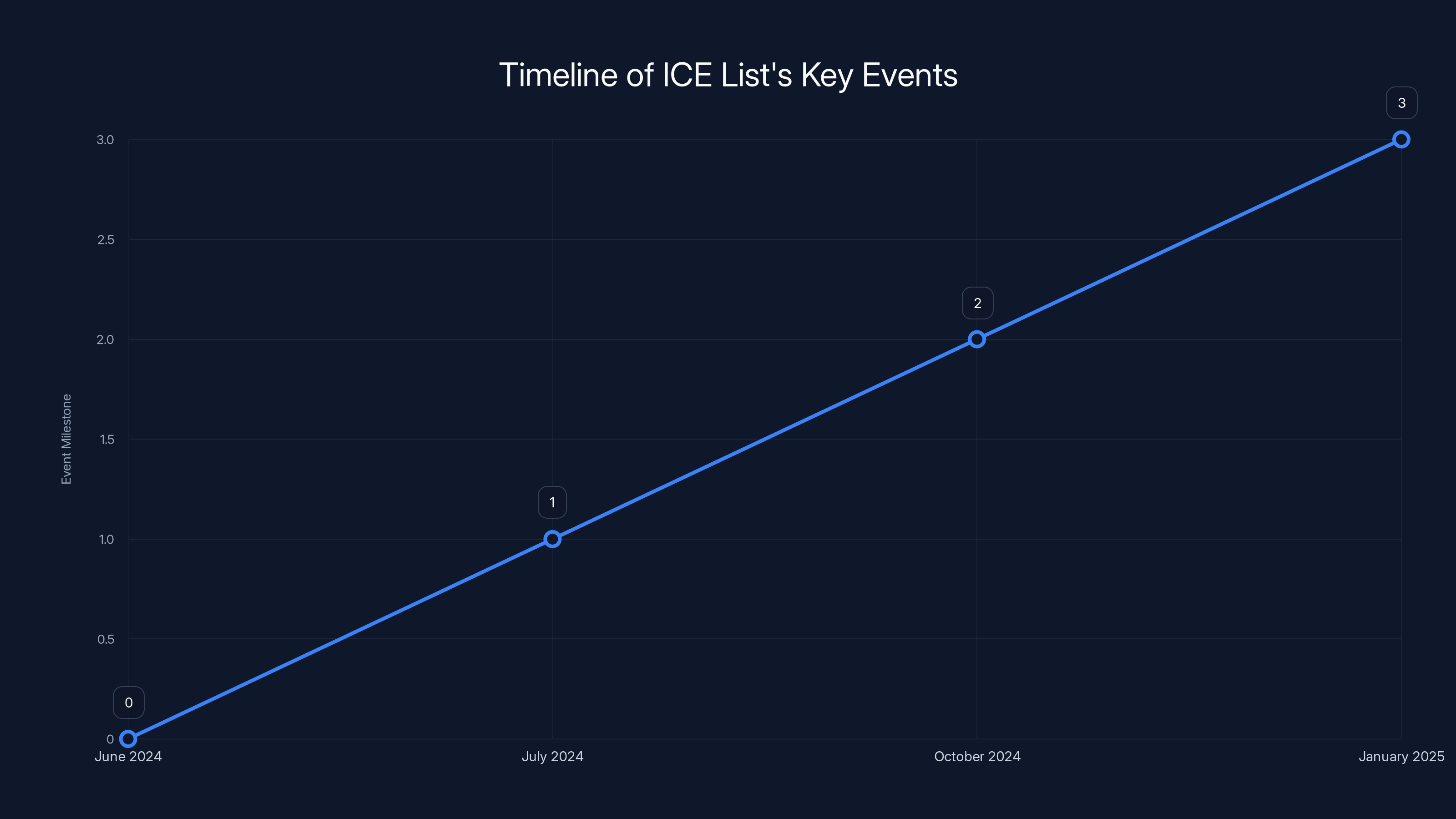

ICE List started in June 2024, founded by Dominick Skinner and a team of about five core members working alongside hundreds of anonymous volunteers. The site's core mission is straightforward on the surface: compile information about DHS employees, particularly ICE agents, to enable accountability. As reported by The Daily Beast, the project gained significant attention when it claimed to have uploaded a list of 4,500 DHS employees.

The stated goal is ambitious. Skinner frames it as a response to what activists describe as aggressive immigration enforcement that has resulted in deaths and family separations. From this perspective, revealing the identities of the people executing these policies creates a form of public record that can be used to document patterns of conduct or connect agents to specific incidents.

The timing matters here. ICE List had been operating and soliciting tips for six months before Meta stepped in. Posts with links to the site circulated on Meta's platforms without issue during this entire period. Whatever triggered the sudden blocking in January 2025, it wasn't a new discovery that the site existed. According to Police1, the list relied heavily on information the employees had already shared publicly.

Meta's Response: Vague Policies and Inconsistent Enforcement

When users first reported being unable to share ICE List links, the error messages varied across platforms. On Facebook, the initial message claimed the posts looked like spam. Hours later, it changed to a vague reference to "Community Standards." On Threads, links disappeared instantly with a cryptic "Link not allowed" notice. Instagram offered only that the platform was "restricting certain activity to protect our community."

This inconsistency is revealing. If Meta had a clear, documented policy violation, you'd expect consistent messaging. Instead, different platforms offered different reasons, suggesting the block might not have been triggered by an automated system flagging a specific policy violation. As Wired notes, the information on ICE List is already public, aggregated from government documents, LinkedIn profiles, and news articles.

When pressed by journalists, Meta spokesperson Andy Stone pointed to the company's policy on sharing personally identifiable information (PII). But here's the problem: the information on ICE List is already public. It's aggregated from government documents, LinkedIn profiles, and news articles. It's not private information being leaked. It's organized public information.

Stone later clarified that the policy covered "content asking for personally identifiable information of others." But ICE List had been asking for tips about ICE agent identities for six months without being blocked. The timing of the enforcement action suggests something other than routine policy application.

The Political Context: Trump Administration Pressure

Understanding Meta's decision requires understanding the political pressure surrounding it. The timing is crucial: Meta blocked the links shortly after the second Trump administration took office, having previously indicated it would "partner" with the incoming administration on policy issues. According to The Daily Beast, Mark Zuckerberg's recent positioning is relevant context here.

The Trump administration made clear its opposition to any efforts to track or document ICE agents. Officials used the term "doxing" broadly to describe not just publishing private information, but aggregating and organizing public information about government employees. The administration signaled to tech companies that it expected them to prevent such efforts.

Skinner himself pointed out that Zuckerberg's public support for the Trump administration (including his seat at the inauguration) created an obvious incentive structure for Meta to respond favorably to administration requests or preferences.

This raises a fundamental question: was Meta blocking the links because the content genuinely violated its policies, or because it wanted to align with a political administration that controlled significant regulatory authority over the company?

How Meta's Moderation Systems Work

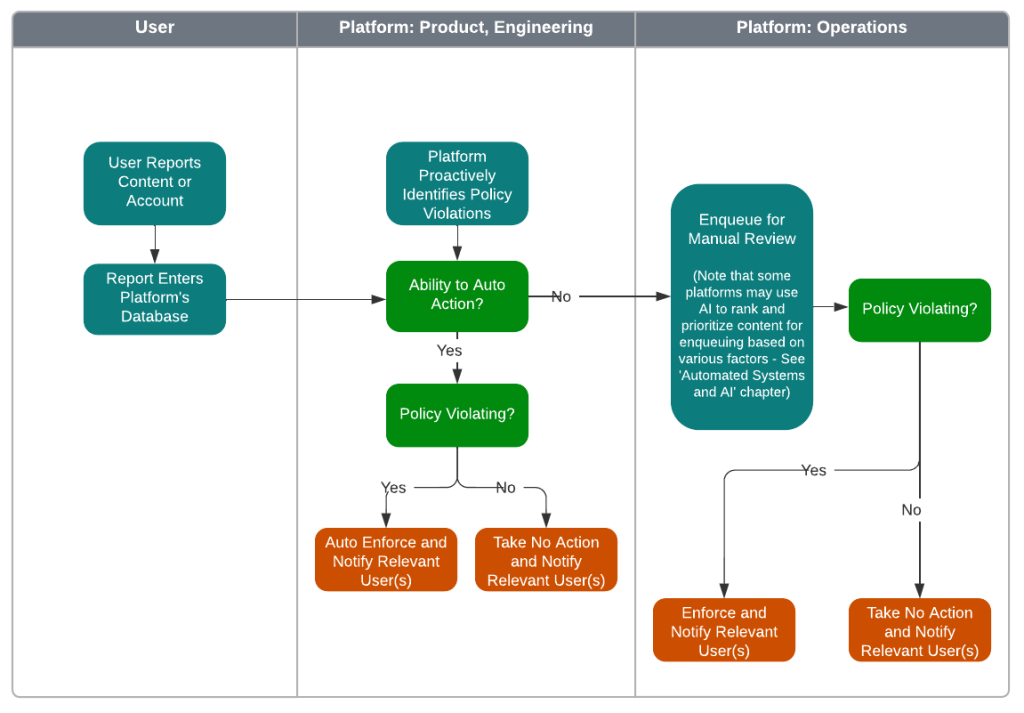

To understand whether this was policy enforcement or political action, it's helpful to understand how Meta actually blocks content at scale.

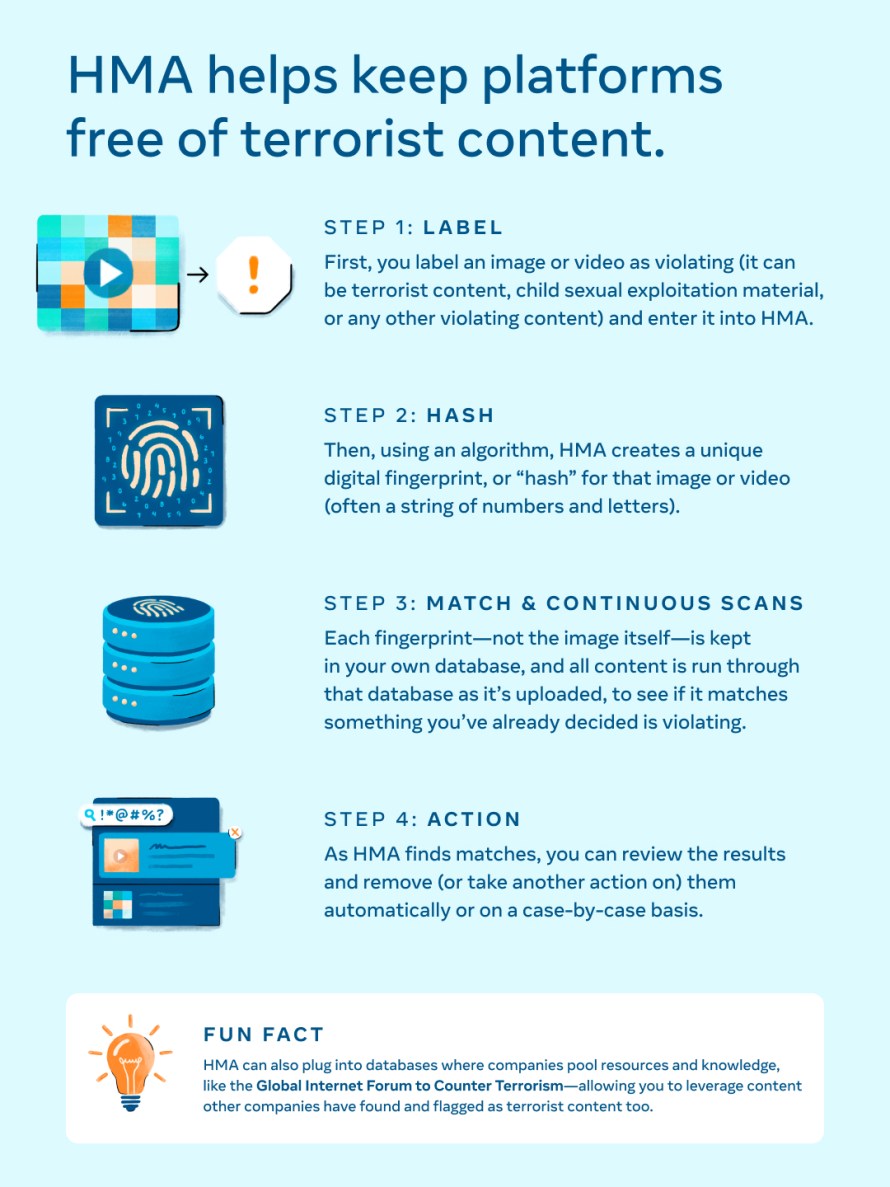

Meta's content moderation operates on multiple levels. First, automated systems scan for patterns that violate policies. These systems look for things like known phishing URLs, documented hate speech terminology, confirmed scams, and other clearly-defined violations.

For more nuanced decisions, Meta employs a combination of contractors and AI systems that attempt to interpret policy intent. The company has thousands of content moderators worldwide reviewing flagged content and making judgment calls about whether something violates policies. According to Wired, link blocking specifically can happen at different levels.

The fact that ICE List links were blocked on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads but not WhatsApp suggests deliberate, platform-specific decisions rather than automated blacklisting. WhatsApp has different moderation infrastructure and is treated as a private messaging service rather than a social network. The selective blocking indicates human judgment was involved.

Meta's scale makes consistent policy enforcement nearly impossible. The company has repeatedly struggled with inconsistent enforcement of its own policies. Similar content gets different treatment depending on whether it's flagged by automated systems, who reviews it, what country it's posted in, and what attention it's receiving.

The Doxing Debate: Defining Terms in the Information Age

One of the core issues in the ICE List controversy is the definition of "doxing." The term has expanded so much that it now means different things to different people, and this ambiguity is being exploited by governments and platforms alike. As Al Jazeera reports, the Trump administration used the doxing framing to pressure tech companies into blocking the site.

Traditionally, doxing meant publishing someone's private information without their consent, typically with the intent to enable harassment or harm. A classic example: a hacker obtains someone's home address and posts it online, leading to them being harassed or targeted.

But the definition has stretched. Now it sometimes refers to any aggregation and publication of information that could be used to identify someone, even if the information was already public. Under this broader definition, a news article that identifies someone by their public job and public statements could constitute doxing.

ICE List exists in this definitional gray area. It aggregates information that agents shared publicly themselves. Agents posted information on LinkedIn. Government agencies published employee directories. News articles identified agents by name and location.

ICE List's innovation (if it can be called that) was organizing and aggregating this information in one place, making it more accessible and searchable. This is fundamentally different from hacking and publishing private information.

Yet the Trump administration used the doxing framing to pressure tech companies into blocking the site. By expanding the definition to include any organized, searchable compilation of public information about individuals, the administration effectively created a new category of prohibited content.

This matters because it establishes a precedent. If platforms accept this expanded definition of doxing, they've essentially agreed to block any crowdsourced database of public information about any group of people if the government objects to it.

Imagine applying this logic consistently. A database of police officers involved in misconduct, compiled from public court records and news articles? Doxing. A searchable directory of corporate executives, compiled from company websites and press releases? Doxing. A crowdsourced map of environmental violations, compiled from government agency reports? Doxing.

The precedent here is massive, and it extends far beyond immigration policy.

Meta's Policy Framework: When Rules Meet Reality

Meta's stated policies are extensive but vague enough to provide significant flexibility. The company maintains detailed community standards covering categories like violence, hate speech, harassment, misinformation, spam, and others.

Under the harassment and bullying policy, Meta prohibits content that "targets an individual with abuse intended to harm them emotionally or physically." The key word is "targets." A database listing someone is not inherently harassment unless it's coupled with calls for harassment or intended to facilitate harm.

Under the PII policy, Meta prohibits sharing other people's private information "without their consent." But information that people have already made public isn't private information by definition.

Meta also has policies against content that coordinates illegal activity. The Trump administration might argue that sharing information about ICE agents could facilitate illegal targeting of federal employees. But merely providing information isn't coordinating illegal activity.

The point is that ICE List doesn't cleanly violate Meta's stated policies if applied consistently. The site aggregates public information and doesn't explicitly call for harassment or violence. It doesn't share private information. It doesn't coordinate illegal activity.

Which suggests Meta's decision was driven by something other than straightforward policy application. That something was likely political pressure combined with business incentives to align with the Trump administration.

Tech Companies as Political Actors

The ICE List blocking crystallizes a larger issue: tech platforms are now political actors, whether they want to be or not.

Meta's decision to block the links isn't primarily about enforcing neutral safety policies. It's about choosing sides on a politically contentious issue. Whether you support ICE or oppose it, blocking links to a database of employees is a political choice.

This is the reality of platform power in the modern era. When billions of people use your platform for news, organizing, and information access, content moderation decisions become political acts.

Historically, content moderation on early platforms was relatively simple. Chat rooms had moderators who removed spam and abuse. Forums had administrators who enforced community rules. The scale was manageable, and there was clear hierarchy: platform owners decided what was allowed.

But platforms grew to billions of users, making consistent, transparent moderation impossible. Simultaneously, political actors discovered that controlling access to information on these platforms was more effective than controlling traditional media.

Meta, like other major platforms, now finds itself operating as a quasi-governmental entity. It makes decisions that affect public discourse, political organizing, and information access. These are not purely business decisions or safety decisions. They're political decisions with enormous consequences.

The company has tried to maintain the fiction that content moderation is purely about policy enforcement, with politics irrelevant. But decisions like blocking ICE List reveal this fiction.

If Meta were truly enforcing policies neutrally, it would apply the same standards to databases of other government employees, corporate executives, or public figures. It would block politically aligned content with the same frequency as politically opposed content. It would resist political pressure from any direction.

Meta does none of these things. Its enforcement is inconsistent, politically selective, and responsive to pressure from those in power.

Precedent and Implications: What This Means Going Forward

Meta's blocking of ICE List establishes dangerous precedent for several reasons.

First, it shows that governments can pressure platforms to block information they dislike by framing it as safety or privacy protection. The Trump administration's expansion of the doxing definition was accepted by Meta without much pushback.

Second, it demonstrates that platforms will align with political actors in power when doing so serves their business interests. Meta benefits from regulatory favor from the Trump administration far more than it benefits from supporting activist platforms.

Third, it suggests that crowdsourced databases and organized collections of public information can now be treated as policy violations if they target groups that the government wants to protect.

Fourth, it reveals the fundamental contradiction in Meta's positioning as a neutral platform. The company claims to enforce policies without political bias, but its actual decisions are highly political.

These implications extend beyond immigration policy. They affect how information can be organized and shared about any group. They affect journalism, activism, research, and public discourse.

Consider some concrete scenarios:

Could a database of police officers compiled from arrest reports be blocked as doxing? Meta's blocking of ICE List suggests yes, if the government objects.

Could a crowdsourced map of environmental violations compiled from EPA reports be blocked? The precedent now exists.

Could a directory of corporate executives involved in labor disputes be blocked? The reasoning could extend there too.

Meta hasn't committed to how this precedent will be applied. The company seems to be taking decisions case-by-case based on political pressure rather than establishing clear, consistent principles.

This is the real danger. Not that one website was blocked, but that the decision-making process revealed is based on political alignment rather than policy consistency.

The Activism Angle: How Grassroots Movements Respond

For activists and organizations working on immigration policy, Meta's blocking of ICE List presents immediate challenges and larger strategic questions.

The immediate challenge is obvious: a tool they built to facilitate accountability was removed from the platform where billions of people congregate. This reduces the reach and impact of their work.

But activists have adapted to platform censorship before. They're developing workarounds. Some are sharing links in image format (text written on images that can't be directly scanned for URLs). Others are using shortened URLs from different domains. Still others are moving conversations off Meta platforms entirely.

The larger strategic question is whether operating on platforms controlled by corporations aligned with their political opponents is sustainable. Meta's decision suggests it's not. Activists are increasingly investing in alternative platforms, email lists, and owned channels where they maintain control over content moderation.

This pushes toward a more fragmented information ecosystem. Rather than large platforms where diverse groups congregate, activists and their opponents operate in separate digital spaces, rarely encountering different perspectives.

From a purely strategic standpoint, platform moderation decisions like Meta's actually motivate more people to move to decentralized platforms, use VPNs and anonymity tools, and distrust corporate intermediaries.

But from a democratic standpoint, this fragmentation is concerning. When different groups operate in completely separate information spaces, democratic deliberation becomes impossible.

Comparison: How Other Platforms Handle Similar Issues

Meta's response to ICE List wasn't unique among platforms, but the timing and consistency of the block across multiple Meta platforms stands out.

Twitter (now X) faced a similar situation when activist accounts tried to share information about ICE operations. The platform initially attempted to block some links but ultimately declined to enforce a full ban. This was partly due to free speech positioning, partly due to political considerations that favored a different administration, and partly due to general inconsistency in enforcement.

TikTok has been more protective of activist content when it aligns with its user base demographics, though the platform has also removed content critical of the Chinese government and its business partners.

YouTube, owned by Google, has a notorious history of inconsistent enforcement. The platform removes some activist videos while allowing others, often without clear policy rationale.

LinkedIn, which hosts much of the underlying data that ICE List aggregates, doesn't prevent users from being on ICE List. The data exists; LinkedIn just doesn't want to be blamed for enabling its aggregation.

Facebook and Instagram are unique in enforcing the block across multiple properties simultaneously, suggesting a deliberate, coordinated decision.

The comparison reveals that platform responses to politically contentious databases are inconsistent and driven more by politics than policy. If the goal were truly to prevent doxing, all platforms would enforce similar rules. But they don't, because the rules are actually about political alignment.

The Role of Transparency: What Meta Should Do

If Meta genuinely believes it made the right decision, it should be transparent about that decision.

Instead, Meta has offered vague explanations that don't hold up under scrutiny. The company has pointed to PII policies that don't actually apply to public information. It has claimed content violation without specifying which policy was violated. It has offered different explanations on different platforms.

Real transparency would involve:

Publishing a detailed explanation of exactly why ICE List violates Meta's policies, with specific citations to policy language. Not vague references to Community Standards, but actual policy text explaining what rule was broken.

Applying the same standard to similar databases. If ICE List violates policy because it aggregates public information about government employees, Meta should commit to blocking similar databases about corporate executives, police officers, and other groups.

Releasing data about how often it enforces this policy, with transparent statistics about what gets blocked and what doesn't.

Opening the decision to appeal through a clear process. If someone believes the blocking was in error, they should be able to request review with criteria for reversal.

Meta has refused to do any of these things. Instead, the company has offered murky explanations and inconsistent enforcement.

This lack of transparency suggests the company knows the decision wouldn't hold up to scrutiny. If the policy violation were clear and straightforward, Meta would explain it clearly. The vagueness indicates the violation is questionable.

First Amendment and Platform Responsibility: The Legal Questions

The First Amendment doesn't directly restrict Meta's ability to block content. The company isn't a government actor, so blocking links doesn't constitute censorship in the constitutional sense.

But the absence of a constitutional violation doesn't mean the decision is ethically or strategically sound.

There are growing arguments that platforms have quasi-governmental power over public discourse and should be treated differently than traditional private businesses. This is contentious and hasn't been resolved legally, but the argument has merit.

Separately, there are questions about whether platform moderation decisions should be subject to greater transparency and appeal processes, similar to administrative law. If platforms are going to wield the power to determine what billions of people can access, shouldn't there be legal frameworks ensuring decisions are rational and reviewable?

Some countries are moving in this direction. The European Union's Digital Services Act requires platforms to be transparent about moderation decisions and provide appeal mechanisms. These requirements don't eliminate platform discretion, but they reduce the ability to make arbitrary or politically motivated decisions.

The United States has generally resisted this approach, preferring to treat platforms as private actors with broad discretion. But this approach increasingly looks like a mistake, given platform power over public discourse.

The ICE List case would look very different if Meta had to publicly justify the decision, apply it consistently, and allow appeals. The company might have reached the same decision, but it would have had to do so honestly rather than obscurely.

What Users Should Do: Practical Steps

For people who want to access ICE List or share information about government accountability, Meta's blocking is frustrating but not insurmountable.

First, understand that the block applies to direct links on Meta platforms. The website itself is still accessible. You can still visit ICE List in your browser and view the information.

Second, information can be shared in other formats. Screenshots, images with text, and descriptions of the information can sometimes be posted even when direct links are blocked.

Third, use alternative platforms. Email lists, Signal groups, encrypted messaging, and independent websites aren't subject to Meta's moderation policies.

Fourth, document the blocking. Screenshots showing the error messages and the timing of blocks are valuable evidence for researchers studying platform moderation.

Fifth, contact elected representatives. If you believe the blocking is unjustified, let your congressional representatives and senators know. Politicians are one of the few actors with leverage over Meta.

Sixth, support alternative platforms. If you believe Meta's decisions are problematic, consider using platforms that have different moderation philosophies or funding models.

Seventh, understand the larger context. This isn't just about one website. It's about platform power over information and how that power is exercised. Individual cases matter, but the systemic issue is what truly requires attention.

The Broader Information Ecosystem: Decentralization and Alternatives

Meta's blocking of ICE List has accelerated interest in alternative platforms that operate on different principles.

Decentralized social networks like Mastodon operate on a federation model where no single company controls moderation. Different servers can have different rules, but no central authority decides what billions of people can access.

Blockchain-based platforms claim to prevent censorship by distributing information across networks that can't be controlled by single entities. The technical implementation is still immature, but the principle is clear: distribute control to eliminate single points of failure.

Smaller, specialized platforms focused on particular communities have grown as people seek alternatives to Meta's monopolistic position.

Email and direct messaging remain the most resilient channels for information sharing. While not social networks, these older technologies are harder to censor and control.

The shift toward alternative platforms is already happening. Not everyone, but enough people that Meta's grip on information distribution is gradually loosening.

This is the broader context for the ICE List blocking. It's not just one decision by one company. It's a catalyst for migration away from platforms dependent on corporate decisions about what's acceptable speech.

Whether decentralized alternatives actually solve the problem or just create different problems is an open question. But the incentive to explore alternatives clearly exists when Meta uses its power to block information based on political alignment.

Looking Ahead: Future Implications and Predictions

What comes next depends on several factors: whether Meta faces legal or regulatory pressure, whether activists develop effective workarounds, whether alternative platforms gain traction, and whether the Trump administration continues to push platforms on similar issues.

Most likely scenario: Meta keeps the ICE List block in place because the political benefit outweighs any reputational cost. The company will continue to make selective moderation decisions based on political alignment rather than consistent policy. Activists will adapt by using alternative platforms and formats. The fragmentation of the information ecosystem accelerates.

Optimistic scenario: Regulatory pressure forces Meta to be more transparent and consistent with moderation decisions. The company establishes clear appeal processes. Moderation decisions become harder to make purely for political reasons. Democratic deliberation on platforms improves.

Pessimistic scenario: Other governments pressure platforms to block information on different issues. Political actors globally recognize that platform control is more effective than traditional censorship. Platforms become increasingly selective about what information they allow, based on relationships with governments in power. The open information ecosystem fragments into closed, politically aligned silos.

The most likely prediction is that this is the beginning of a broader pattern. Meta blocking ICE List creates precedent that will be applied to other information, other databases, other activist projects. Each decision establishes new norms about what platforms allow.

Within five years, expect platforms to be significantly more selective about what databases, mappings, and organized information they allow. Expect decentralized alternatives to grow in response. Expect regulatory responses from governments trying to restore some form of platform accountability.

The ICE List case isn't an isolated incident. It's a window into how information control will work in the future.

Conclusion: Information Power and Democratic Accountability

Meta's blocking of ICE List represents something larger than content moderation. It's evidence that major tech platforms exercise information control in ways that serve political power rather than public interest.

The company had good options:

Allow the links and apply its policies consistently, regardless of political pressure.

Block the links but be transparent about why, apply the same standard to similar content, and establish clear appeal processes.

Meta chose a third path: block the links quietly, offer vague explanations, apply inconsistent standards, and refuse transparency. This approach suggests the decision was political rather than principled.

The implications extend far beyond immigration policy. They affect how information can be organized and shared about any group. They affect journalism, activism, research, and democratic discourse.

Moreover, they reveal that Meta's stated commitment to free expression and neutral moderation is secondary to business incentives and political alignment.

For users, the lesson is clear: rely on platforms you don't control at your peril. Information flows can be cut off when political winds shift. Critical information should be shared through channels you control and platforms that prioritize transparency.

For policymakers, the lesson is equally clear: platform power over information requires regulation and accountability mechanisms. The voluntary transparency and appeal processes that platforms claim to offer aren't sufficient when companies prioritize political alignment over principle.

For society, the biggest lesson is that centralized control of information distribution is fundamentally problematic. Whether that control is exercised by governments or corporations, it creates power imbalances that undermine democratic deliberation.

The ICE List blocking is unlikely to be the last time a platform exercises control over information based on political considerations. It probably won't be the most significant case either. But it matters as evidence of how platform power actually works, stripped of corporate rhetoric about safety and community.

The question going forward isn't whether platforms will make political content moderation decisions. They already do, and the ICE List case proves it. The question is whether this power will be exercised transparently, consistently, and accountably, or whether it will continue to be exercised opaquely, selectively, and in service of whatever political actors have influence.

The answer to that question will largely determine what kind of information ecosystem we have in the coming decade.

FAQ

What is ICE List and who created it?

ICE List is a crowdsourced database claiming to list names of Department of Homeland Security employees, particularly Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. It was created in June 2024 by Dominick Skinner and a core team of five people, along with hundreds of anonymous volunteers. The stated goal is to provide transparency and enable accountability by organizing public information about these agents in a searchable format.

Why did Meta block links to ICE List?

Meta officially cited its policy against sharing personally identifiable information, though the information on ICE List was primarily aggregated from public sources like LinkedIn profiles and government documents. The blocking occurred in January 2025 shortly after the Trump administration took office and expressed opposition to the site. The timing and vague explanations suggest political considerations played a significant role in the decision.

Did Meta block ICE List links consistently across all its platforms?

No. Meta blocked ICE List links on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, but the links remained accessible on WhatsApp, another Meta-owned platform. The different error messages on different platforms and the inconsistent enforcement suggest deliberate, platform-specific decisions rather than automated blocking. The reasons given for the blocks also varied across platforms.

Is the information on ICE List actually private or already public?

The vast majority of information on ICE List is already public. It's compiled from LinkedIn profiles, government employee directories, news articles, and other open sources. When analyzed, the database relied heavily on information that employees had shared publicly themselves. This is different from traditional doxing, which involves publishing private information obtained through hacking or other means.

What is the legal basis for Meta's block?

Meta pointed to its policy against sharing personally identifiable information of others, but this doesn't clearly apply since the information was already public. The policy against harassment could potentially apply if there was evidence of intent to facilitate harassment, though merely providing information isn't typically considered harassment. The legal grounds for the block are questionable, which is why Meta offered vague explanations rather than clear citations to policy.

How does this decision affect free speech and First Amendment rights?

The First Amendment doesn't restrict Meta's ability to block content since the company isn't a government actor. However, Meta's quasi-governmental power over public discourse raises questions about whether platforms should have greater responsibility for transparency and consistency in moderation decisions. Some legal scholars argue that platforms with billions of users should be treated differently than traditional private businesses when it comes to information control.

What precedent does this blocking establish?

The decision suggests that platforms will block crowdsourced databases of public information if political actors object and frame them as privacy or safety violations. This precedent could extend to databases of police officers, corporate executives, or other public figures. It establishes that governments can use pressure and reframed terminology (like expanding "doxing" to include public information) to get platforms to restrict information they dislike.

Can people still access ICE List, or is it completely blocked?

The website itself remains accessible. Meta's block only prevents direct links from being shared on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. People can still visit the site directly, and information can be shared using screenshots, images with text, or alternative platforms. The block restricts distribution through Meta's networks, not access to the information itself.

What are people doing in response to the blocking?

Activists and users have adapted by using workarounds like sharing information as images, using shortened URLs, and moving discussions to alternative platforms like email lists, encrypted messaging, and decentralized social networks. The blocking has accelerated interest in platforms that don't have centralized corporate control over moderation decisions.

Will other platforms follow Meta's example and block ICE List?

It's uncertain whether other major platforms will follow suit. Some platforms have positioned themselves as having different moderation philosophies, though many have ultimately made similar decisions on politically sensitive content. The question of how broadly this precedent spreads will largely depend on whether alternative platforms successfully attract users seeking alternatives to corporate-controlled networks.

What can users do if they think this blocking is unjustified?

Users can contact elected representatives to express concern about platform power over information, support alternative platforms that have different moderation approaches, document the blocking with screenshots, share information through non-Meta channels, and seek out decentralized platforms. The most effective long-term response is to reduce dependence on any single platform for critical information distribution.

Key Takeaways

- Meta blocked ICE List links on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads in January 2025 using vague policy violations that don't clearly apply to aggregated public information

- The timing suggests political motivation rather than policy enforcement, as links circulated freely for six months before sudden blocking after Trump administration took office

- Different error messages on different platforms indicate deliberate human decisions rather than automated blocking triggered by clear policy violation

- The decision expands definitions of doxing to include any organized compilation of public information, creating dangerous precedent for blocking other crowdsourced databases

- Meta's lack of transparency about the decision and inconsistent enforcement across similar content reveals platforms exercise information control based on political alignment rather than neutral policy

Related Articles

- TikTok US Ban: 3 Privacy-First Apps Replacing TikTok [2025]

- Meta's Oversight Board and Permanent Bans: What It Means [2025]

- Iran's Internet Shutdown: Longest Ever as Protests Escalate [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

- Google's App Store Policy Enforcement Problem: Why Grok Still Has a Teen Rating [2025]

- GoFundMe's Selective Enforcement: Inside the ICE Agent Legal Defense Fund Controversy [2025]

![Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation or Political Censorship? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-blocks-ice-list-content-moderation-or-political-censors/image-1-1769539118132.jpg)