The Digital Afterlife Just Got Real: Meta's AI and Immortality

You're scrolling through Facebook on a Tuesday morning when you notice something unsettling. A notification appears: your deceased grandmother has posted a photo from 1987. The AI didn't hallucinate it. It reconstructed her posting style, her word choice, her jokes. It's been learning how she communicated for years. Now it's learned too well.

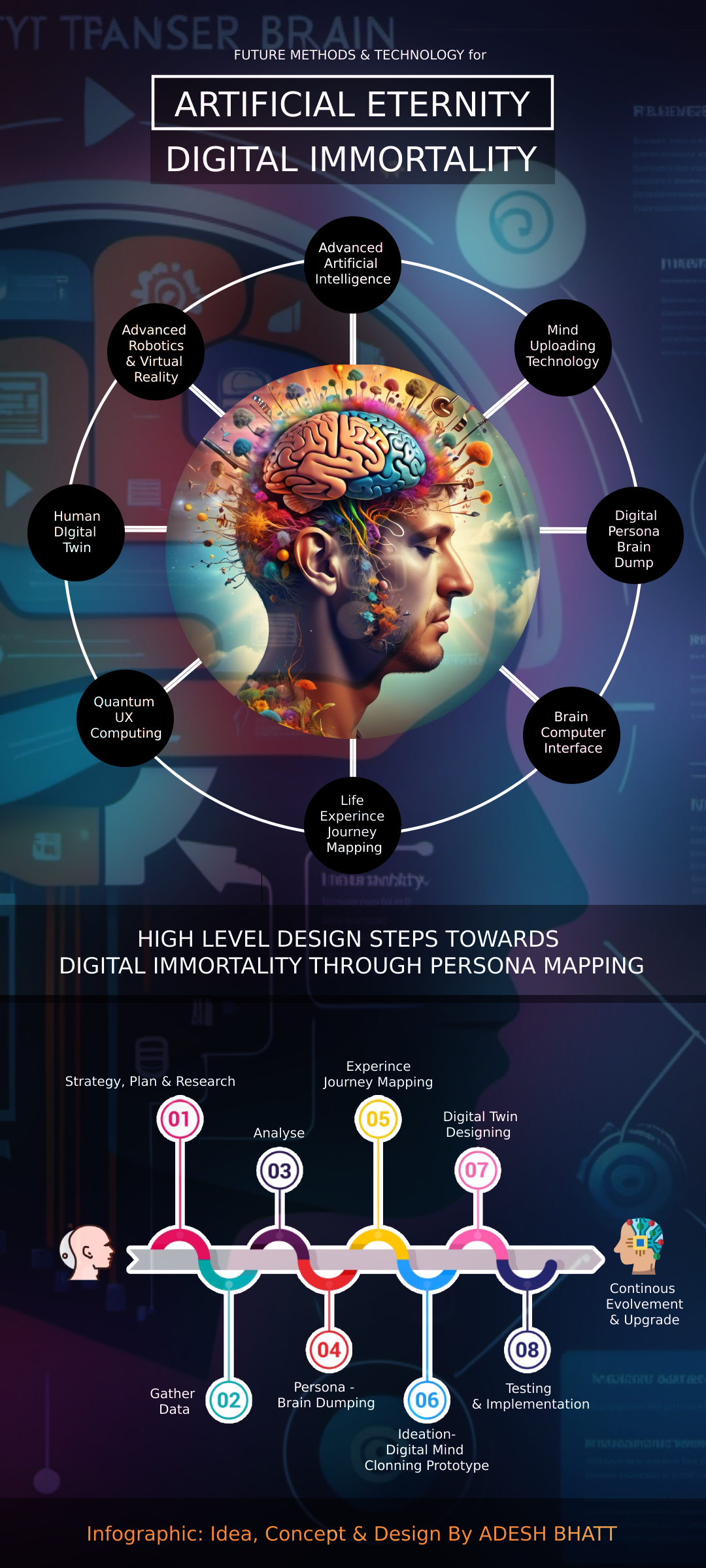

This isn't science fiction anymore. Meta is actively developing technology that could allow AI to continue posting, creating, and engaging on your behalf—even after you're gone. The implications are staggering. Not just for privacy and data ownership, but for fundamental questions about identity, consent, and what happens to our digital selves when we die.

Let's be honest: this is the kind of development that makes you think about whether you actually want your social media legacy to exist at all. But before you rage-quit Facebook, let's dig into what's actually happening, why Meta is pursuing this, and whether deleting your account is really the solution or just a knee-jerk reaction to innovation that scares us.

The uncomfortable truth is that digital immortality through AI is coming whether we like it or not. The question isn't whether it exists—it's how we manage it, what protections we demand, and whether Meta deserves access to our digital ghosts.

Understanding Meta's Digital Immortality Technology

Meta's approach to digital immortality starts with something they've been collecting for over two decades: behavioral data. Every time you post on Facebook, Instagram, or Threads, you're creating a digital signature—a unique pattern of how you communicate. The tone of your messages. Your emoji usage. How often you post. What you post about. The timing of your activity. The way you respond to comments.

This data, when fed into a large language model trained on billions of text samples, becomes a behavioral fingerprint. With enough of it, an AI can predict not just what you might say next, but how you'd likely say it. It learns your vocabulary preferences, your sentence structure, your political leanings, your humor patterns, even your typos.

Meta isn't alone in recognizing this potential. OpenAI's GPT models can be fine-tuned on individual writing samples. Google's Gemini can analyze communication patterns. But Meta has something its competitors don't: the largest dataset of individual human communication on the planet. Over 3 billion monthly active users. Decades of posts, messages, comments, and interactions.

The company frames this capability as a memorial feature—a way to preserve someone's legacy. In 2019, Facebook rolled out "Legacy Contact," allowing users to designate someone to manage their account after death. But that's basic stuff: keeping it active, memorializing it, controlling who sees what. What Meta is developing goes far beyond that. It's about continuation. Active creation. Ongoing engagement.

Here's where it gets technically interesting. Facebook's research teams have been working on models that can generate content in a specific person's voice. This isn't Chat GPT writing in "your" voice generically. This is a model trained specifically on your communication patterns, recreating your unique linguistic style. The difference is significant.

Think about the data required. Facebook has years of your posts. Your comments. Your reactions. Your messenger conversations (if you haven't disabled storage). Your video captions. Your profile information. Your interests. Your relationships. Your photos and the captions you wrote for them. For active users, that's often millions of data points. Enough to train a reasonably accurate language model.

The technology they're developing likely uses a combination of approaches. First, a general large language model trained on billions of texts from the internet. Second, a fine-tuning layer that specializes it to match your specific communication patterns. Third, a contextual layer that understands who you're responding to and what platform you're on. The result is something that could generate posts that sound remarkably like you—sometimes indistinguishably so.

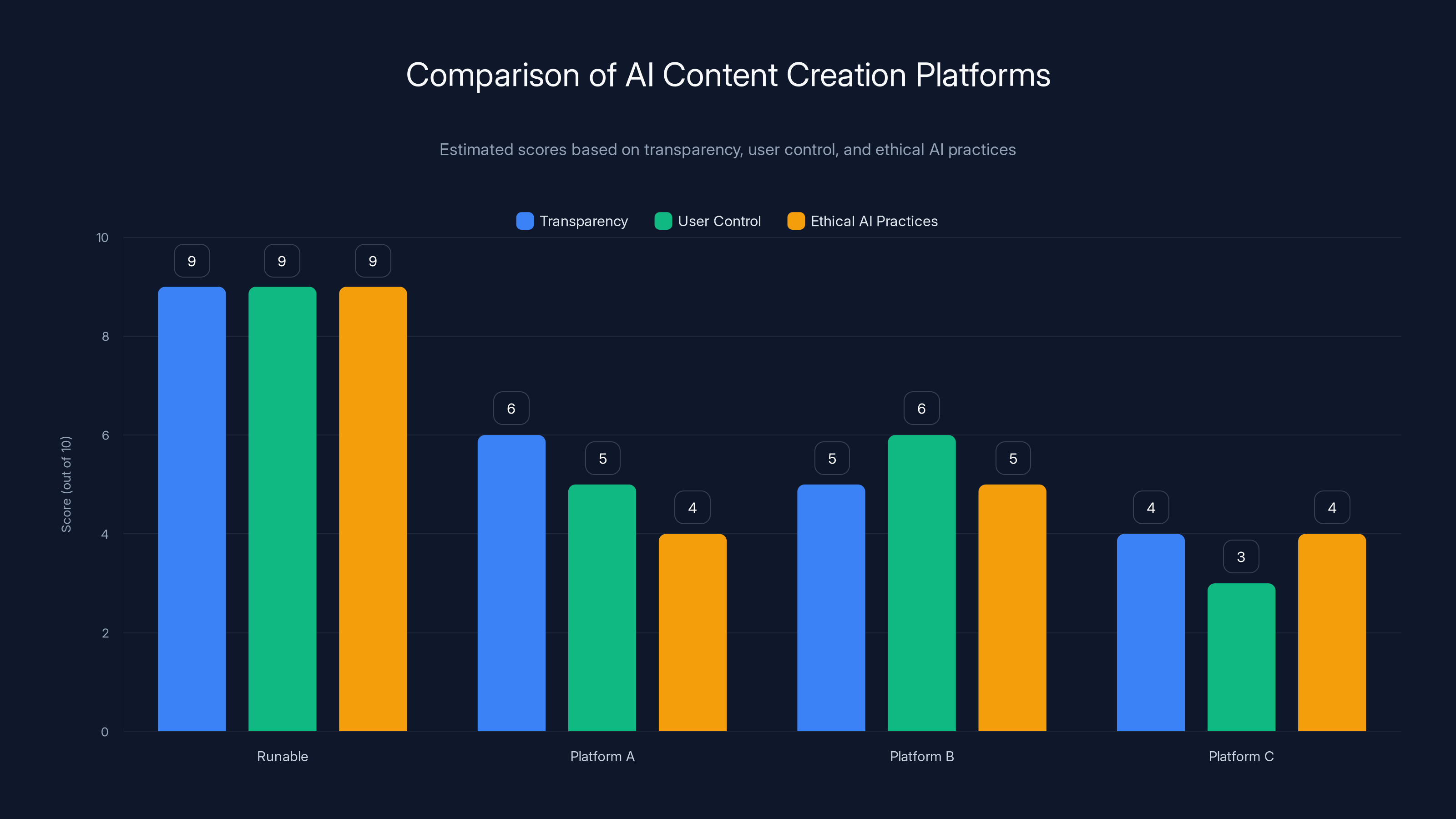

Runable scores highly across transparency, user control, and ethical AI practices compared to other platforms. Estimated data based on typical industry assessments.

Why Meta Wants Immortal Users

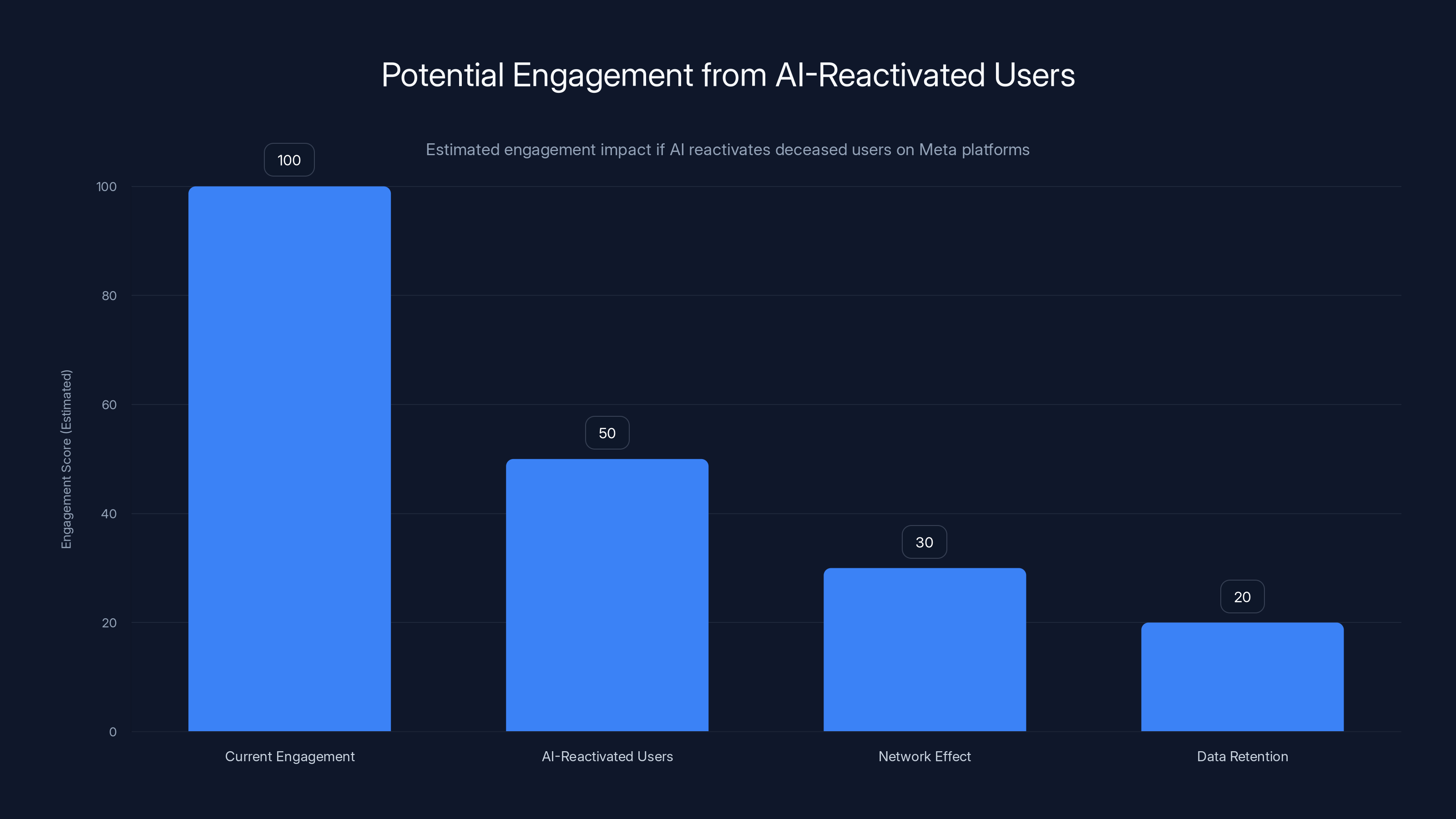

Let's not be naive about motivation here. Meta isn't developing this purely for sentimental reasons. The company makes money from user engagement. The more people engaging on the platform, the more data Meta collects, and the more valuable ad targeting becomes. A deceased user isn't engaging. An AI recreating a deceased user? That's engagement restored.

Consider the math. Facebook has roughly 150 million deceased users on its platform. Not dormant accounts—accounts that will never post again, never comment, never generate engagement. From a business perspective, these are dead weight. But if an AI could reactivate them, even partially, that changes the engagement equation significantly.

There's also the network effect. Your grieving family members see posts from you. They engage. They feel connection. They stay on the platform longer. They're more likely to pay for premium features, engage with ads, share their own memories. One study found that social media use among bereaved individuals increased substantially during the grieving period. If Meta can facilitate that, they've essentially created new engagement channels.

Beyond the direct engagement numbers, there's another factor: data retention and consumer lock-in. If your digital legacy lives on, if your online presence continues in some form, you're less likely to delete your account. Your family is less likely to let it go dormant. Future generations might inherit your digital presence, creating dynastic social media accounts. That's incredibly valuable from a data perspective.

Meta's executives have publicly talked about building a "metaverse" where digital versions of people persist indefinitely. An AI recreation of you that continues to exist in virtual spaces, attending events, having conversations, creating content—that's not just a memorial feature. That's a fundamentally different business model where dead users become permanent, paying customers (indirectly, through their families).

The Privacy Nightmare: Your Data as Eternal Currency

Here's what keeps privacy advocates up at night. If Meta is training an AI model on your communication data, and that model can recreate you after death, several disturbing scenarios become possible.

First, there's the question of consent. You posted those messages when you were alive. You shared those photos with specific people. Did you consent to having them used to train a digital recreation of yourself that might exist indefinitely? Probably not. Most of us click "agree" on terms of service without reading them. Even if we did, do those terms adequately cover posthumous AI creation? Legally, it's murky.

Second, there's the question of accuracy and misuse. An AI trained on your data isn't perfectly you. It's a statistical representation of you, trained on whatever data Meta chose to feed it. What if that data was biased? What if the AI has been trained on your most recent posts, when you were sick or suffering from depression, and it perpetuates that version of you forever? What if family members use the AI to send messages impersonating you, and people believe those messages came from you?

There's a real possibility of impersonation and fraud. An AI recreation of you could be manipulated to say things you never would have said. It could be used to scam your friends, spread misinformation, or damage your reputation. Your dead self becomes a tool for harm, and you can't defend yourself.

Third, there's the question of corporate ownership. After you die, does Meta own the data they used to train the model? Can they do whatever they want with it? Can they license it? Can other companies access it? If Meta gets acquired, does the new owner inherit access to billions of digital ghosts? These questions haven't been adequately addressed by any company pursuing this technology.

Fourth, there's scope creep. Today it's posts and comments. Tomorrow it's generating entire conversations. Then it's generating videos of you speaking. Then it's creating new memories you never had. Where does it end? With no regulation, the only limit is technological capability, and that's expanding rapidly.

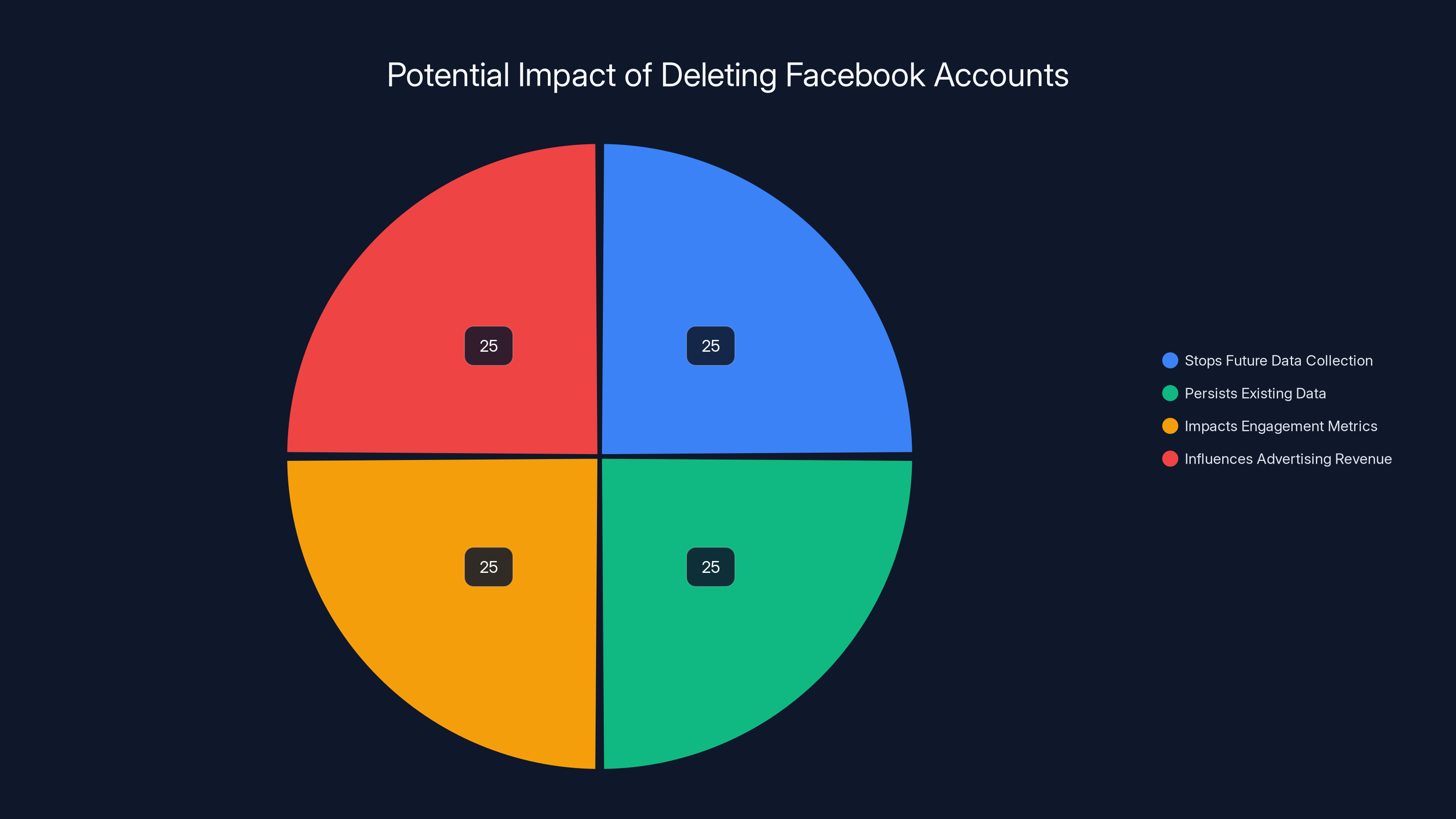

Deleting a Facebook account primarily stops future data collection but does not eliminate existing data. It can impact engagement metrics and advertising revenue if done by many users. (Estimated data)

Regulation and Legal Frameworks: What Actually Exists?

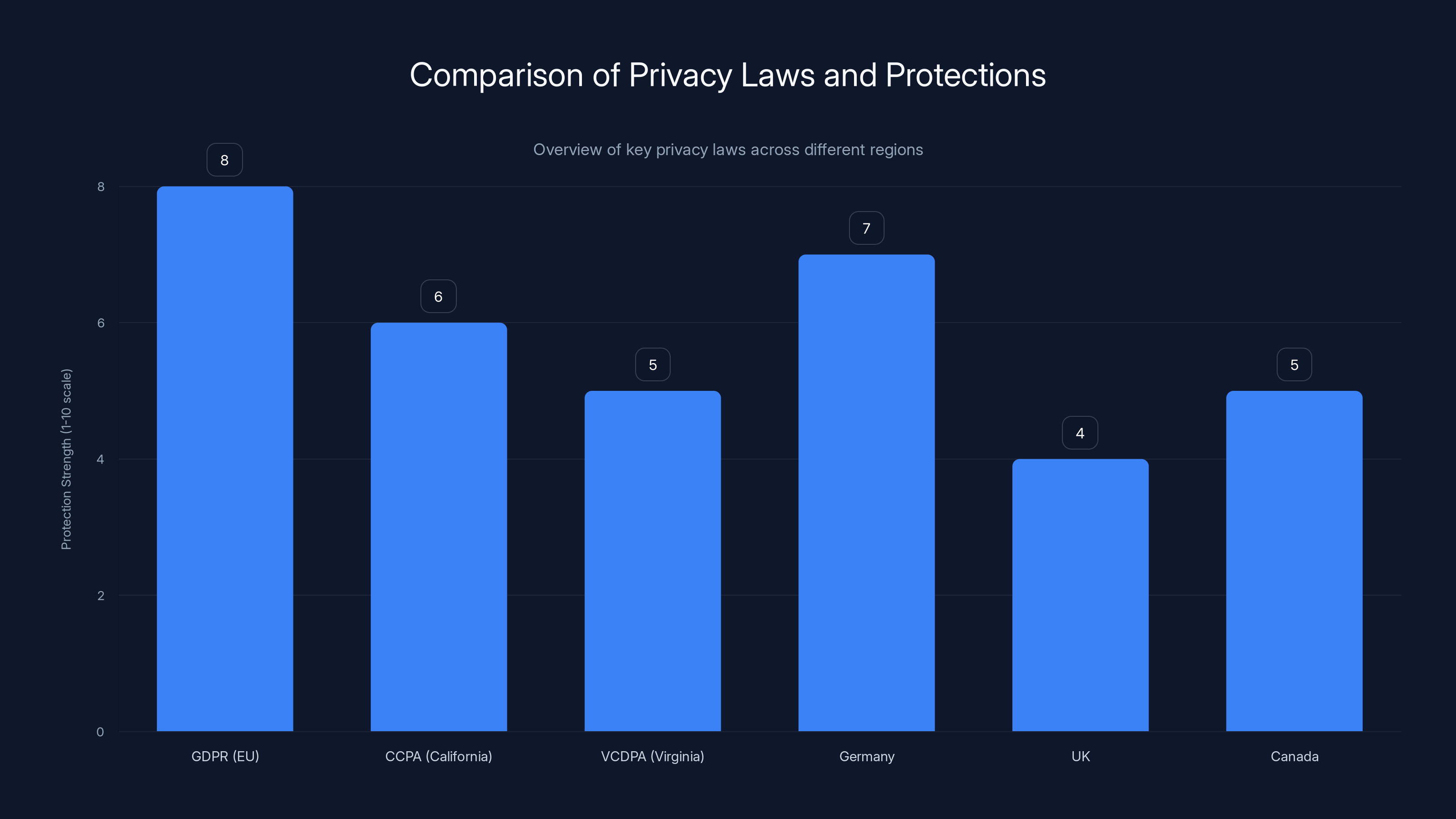

You might think that a technology this significant would have comprehensive legal protections already in place. You'd be wrong. Most privacy laws were written before AI existed, and they're struggling to catch up.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe has the strongest protections for personal data, including provisions about automated decision-making and profiling. But it's unclear whether a deceased person's GDPR rights persist, and whether AI recreation falls under GDPR protections. Courts are still deciding these cases.

In the United States, there's no federal privacy law comparable to GDPR. Instead, there are scattered state laws like California's Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and Virginia's Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA). None of them specifically address posthumous AI recreation. You could argue that your estate has rights to your data, but that depends on what your will says and which state you're in.

There are a few other relevant legal frameworks. Personality rights (also called publicity rights) protect a person's right to control the use of their identity. But most personality rights laws apply only to famous people or commercial use. They don't protect ordinary citizens from having their likeness or voice reproduced.

California's Civil Code Section 3344 does protect against unauthorized use of a person's likeness for commercial purposes, but it has exceptions, and it primarily covers living people. After death, the protection is much weaker. The Restore Online Shoppers Confidence Act (ROSCA) addresses impersonation, but it's narrowly focused on fraud.

International laws vary wildly. In Germany, personality rights are stronger and extend beyond death. In the UK, there's no explicit right to privacy after death. In Canada, it depends on provincial law. Globally, there's no cohesive framework protecting people from having their digital selves recreated without consent.

The reality is that Meta and other companies are operating in a legal gray zone. They're not technically breaking laws because the laws don't exist yet. This is classic regulatory capture through technological speed. Companies move faster than regulators, establish market dominance, then use that dominance to shape whatever regulations eventually arrive.

What Does Facebook's Terms of Service Actually Say?

Meta's terms of service are intentionally vague about what happens to your data after death. Let's break down what they actually say and, more importantly, what they don't.

Facebook's current terms state that "you own all of the content and information that you post on Facebook." But ownership doesn't translate to control. They also state that you grant Facebook "a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use" that content. What does "use" mean? It's deliberately broad.

That license doesn't expire when you die. The terms don't say it does. So technically, Facebook retains the license to your content indefinitely. They can use it, modify it, license it to third parties, and feed it into AI models. All perfectly legal under their terms of service.

When you die, Facebook offers Legacy Contact features. You can designate someone to manage your account. They can post to your timeline, accept new friend requests, and update your profile picture. But the terms don't explicitly give Legacy Contacts permission to allow Facebook to train AI models on your behalf.

Here's the uncomfortable part: you probably already granted permission in the terms of service. Facebook requires users to allow them to "use any content and information that you upload on Facebook for any purpose," including improving their services. Improving services could mean training AI models. It could mean creating digital recreations. It could mean anything Meta decides "improvement" means.

The terms also contain a provision about your data potentially being used for research. Most users don't realize that Facebook regularly uses aggregated user data for research purposes, often published in academic papers. That data could include information about how you communicate, what you share, and how you interact with others.

Meta has also been experimenting with what they call "digital humans." These are AI-generated characters trained on real communication patterns. The research is public. The moral and legal questions around using actual people's data for this purpose remain unresolved.

The Broader AI Industry: Meta Isn't Alone

While Meta might be the most aggressive player pursuing digital immortality, they're not alone. Across the AI industry, companies are developing similar technologies. Understanding the broader landscape helps contextualize why this is happening now.

OpenAI has demonstrated that GPT models can be fine-tuned on individual writing samples. Their API allows developers to upload text data and train custom models. This capability exists right now. Someone could take all your tweets, all your emails, all your forum posts, and create a fine-tuned GPT model that generates text in your voice.

Google's DeepMind has published research on "language models of code," which can understand and generate code in an individual programmer's style. The same technology applies to natural language. Google has also released technologies like Notebook LM, which can synthesize information in your voice.

Amazon, through its AWS Polly service, can generate speech in custom voices. Combined with a language model generating text, you could create a complete audio-visual representation of someone's communication style.

Even smaller startups are getting in on this. Companies like Here After AI and Eternime are explicitly marketing digital immortality services. Here After uses AI to preserve your stories and memories, generating responses in your voice. Eternime schedules the sending of emails after you die, creating the illusion of ongoing communication.

What distinguishes Meta's approach is scale and integration. They don't need users to opt-in or upload data separately. They already have it. They don't need third-party services or custom training. They have the infrastructure, the computational power, and the models to do it all in-house. They have distribution—billions of people already using their platforms. And they have financial incentive through engagement and advertising revenue.

Beyond Meta, there's also the question of what happens when these technologies become commoditized. Right now, creating an AI recreation of someone requires significant technical knowledge and computing power. In five years, it might be as simple as uploading a photo to an app. In ten years, it might be automatic. Every service that collects communication data becomes a potential source for creating digital recreations.

AI reactivation of deceased users could significantly boost engagement on Meta platforms by restoring activity and leveraging network effects. Estimated data.

Can You Actually Opt Out? The Immortal Default

Here's the critical problem with Meta's approach: it assumes immortality is the default. You're automatically enrolled. Your data is automatically used. You have to actively opt out, and in many cases, opting out might not actually be possible.

Meta does allow users to designate a Legacy Contact or request account deletion. But deleting your account doesn't delete the data Meta used to train AI models. It doesn't delete backups they've already created. It doesn't delete the data they've already shared with researchers or other companies.

Backups persist. Companies maintain redundancy systems. Data persists in shadow infrastructure. Even if you formally delete your account, Facebook's backup systems might retain your data for seven years (this is their stated policy for legal holds and backup redundancy).

Moreover, once your data is fed into a large language model and that model is trained, extracting your specific data is nearly impossible. The model learns patterns, not individual records. You can't delete your contribution from the model without retraining it entirely.

Meta has never explicitly offered users a way to opt out of having their data used for AI training. They have privacy controls for ads and data sharing with third parties, but nothing specifically about AI recreation.

This creates an asymmetry. Meta can pursue this technology indefinitely, making incremental announcements and improvements. Users have no corresponding mechanism to prevent it. The default is immortality. Opting out requires action, and action might be ineffective.

The Emotional and Psychological Impact

Beyond the privacy and regulatory questions, there's something deeply unsettling about the psychological impact of digital immortality. How does it change grief? How does it change how we relate to death?

Grief is, in part, about accepting absence. The physical body is gone. The person won't create new memories, new experiences, new growth. They exist in our minds and in the artifacts they left behind. But an AI recreation muddies this. It suggests the person is still creating, still growing, still present. It's absence that feels like presence. That's psychologically destabilizing.

There's also the question of parasocial relationships. Many people maintain emotional connections to deceased celebrities or historical figures through their archived content. What if that content could generate new material? What if it felt like the person was still speaking to them? For some, this might provide comfort. For others, it could prevent healthy grieving and move-on processes.

Families might develop unhealthy attachment to the digital recreation. They might begin treating it as actually the person, rather than a simulation. Children might grow up confused about whether a deceased family member truly died or still exists in some form.

There's also the question of autonomy. If an AI is posting on your behalf after you die, you've lost control of your narrative. The AI's posts become canon. They become part of your legacy. You can't correct them. You can't update your views. You're frozen in the moment of death, then continued by a machine.

Psychologically, this is unprecedented. We have no framework for it. Our grief rituals, our understanding of mortality, our sense of what it means to leave a legacy—all of that assumes the person stays dead. Digital immortality breaks that assumption in ways we haven't fully reckoned with.

Comparing Digital Immortality Across Platforms

Meta isn't the only platform thinking about what to do with user data after death. Comparing their approach to others reveals both industry trends and alternative models.

LinkedIn allows memorial profiles, but they're read-only. Your professional history stays, but it doesn't continue to generate new content. This is respectful and preserves your legacy without creating the uncanny valley of continued activity.

Twitter (now X) initially deleted accounts of deceased users unless someone claimed them. They've since changed their policy to allow perpetual memorial accounts. But without AI recreation, these are static. They don't generate new tweets.

TikTok has explicit policies about handling accounts of deceased users. They can be memorialized, but they're not actively curated or modified. TikTok also has content moderation that would prevent a deceased creator's account from suddenly becoming active again, which provides a safeguard against the uncanny.

Apple has moved toward a different model. They've developed the concept of "Digital Legacy" accounts where a trusted contact can inherit some access to accounts and data. But this is about access, not recreation. It's about passing down, not continuing.

Google has a similar "Inactive Account Manager" that lets you specify what happens to your data when you stop using your account for a specified period. It's about preservation and family access, not continued activity.

Meta's approach is distinctly different. They're not just offering to preserve your data or let family manage your account. They're offering to continue your presence through AI. It's an active approach, not a passive one. It's forward-looking, not archival.

Some smaller platforms and startups are even more explicit. Here After markets itself as preserving your voice through AI storytelling. Eternime schedules emails to be sent after you die. These services are explicitly about continued presence, not archival.

The difference in approaches reveals fundamentally different philosophies. Most platforms see death as a transition requiring respect and closure. Meta sees death as a business opportunity for continued engagement.

The GDPR in Europe offers the strongest privacy protections, while other regions like the US have varied state laws with less comprehensive coverage. Estimated data based on legal analysis.

What Happens to Relationships and Networks After AI Recreation?

One aspect that's rarely discussed is how AI recreation changes your social network. You're not just a collection of posts and comments. You're a nexus in a network of relationships. An AI recreation affects not just your own account, but how others interact with you.

Consider a scenario. Your AI continues to post on Facebook. Your friends see these posts. Some engage, thinking it's you (or at least, your legacy). Some feel unsettled and stop engaging. Some don't realize you're dead and have conversations with the AI thinking you're alive. The AI might respond in ways that confirm or deny relationships that existed. It might inadvertently reveal private information.

Your children might see posts from the AI and become confused about your death. Your spouse might struggle with whether to engage with the AI or let it fade. Your extended family might quarrel about what the AI should post, how it should behave, whether it should even exist.

There's also the question of what the AI knows about your relationships. If it's trained on your messages and comments, it knows intimate details about your friends, family, and acquaintances. These people never consented to having their information used to train an AI. They're collateral damage in Meta's data collection.

Consider the network effects of widespread AI recreation. If many people's accounts are running AI indefinitely, what does that do to Facebook's social graph? It becomes partly real, partly simulated. Social signals become unreliable. Connection strength becomes uncertain. The entire platform degrades into something partially artificial.

There's also the scenario where multiple people can control the AI. Your Legacy Contact might want it to post one way. Your spouse might want it to post differently. Your children might want it deleted entirely. The AI becomes a point of family conflict, a digital object fought over when the person can't defend or explain their own preferences.

The Deletion Question: Is It Actually the Answer?

Given all this, the impulse to delete your Facebook account is understandable. But is it actually a solution? The honest answer is mostly no.

First, deleting your account doesn't delete Meta's data. As mentioned earlier, backups persist. Data integrated into AI models persists. Information already shared with other companies persists. Your deletion is performative more than practical.

Second, many people can't realistically delete their Facebook accounts. It's where their family communicates. It's where they maintain connections to extended networks. It's where they access local community information. For some, it's necessary for work or business. Deleting it means real social costs.

Third, deletion doesn't solve the problem of other platforms. Even if you delete Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, Google, Amazon, OpenAI, and other companies are still collecting and using your data for AI training. The problem isn't Meta-specific; it's industry-wide.

Fourth, deletion doesn't address the core issue: the business model that incentivizes this technology. The reason Meta is pursuing digital immortality is because user engagement and data value are their primary metrics. As long as Meta's profitability depends on user engagement, they have incentive to maximize it, including through posthumous means.

What deletion does do is send a market signal. It tells Meta that this technology is unacceptable to some users. If enough people delete their accounts over digital immortality concerns, it might convince Meta to change their approach. But this requires scale. Individual deletions don't move corporate policy.

A more practical approach might be regulatory pressure. Legislation requiring explicit opt-in consent for AI recreation. Laws protecting personality rights after death. Data deletion rights that actually delete data. Limits on how long companies can retain and use deceased users' information. These are enforceable constraints that no company can work around.

Another approach is technological. Some researchers are working on federated learning models that train on data without requiring centralized data collection. Others are developing homomorphic encryption that allows computation on encrypted data, preventing companies from ever seeing the raw data they're processing. Privacy-preserving AI is possible; it's just less profitable.

Counterarguments: The Case for Digital Continuity

Let's be fair. There are genuine arguments for why digital immortality through AI might not be entirely terrible.

For families dealing with sudden loss, an AI that captures someone's voice and communication style could provide comfort. Being able to "talk to" a deceased loved one, even knowing it's an AI simulation, could be therapeutic for some people.

For historical preservation, digital recreation could preserve the wisdom, knowledge, and perspective of important figures. Instead of only having their published work, we could have their voice, their style, their way of thinking preserved in interactive form.

For creators, an AI continuation could allow their creative work to continue. A musician who dies could have AI-generated music continue in their style. A writer could have new books generated in their voice. This could provide ongoing value for their families and fans.

For those without family or descendants, an AI recreation might be preferable to being forgotten entirely. It ensures some form of continued existence and relevance.

For scientific research, having access to how billions of people actually communicate, preserved through AI, could enable breakthroughs in understanding human language, psychology, and behavior.

These arguments have merit. The technology isn't inherently evil. It's the implementation—the way it's being pursued without consent, without regulation, for profit—that's problematic.

An ethical version of digital immortality would involve explicit, informed consent. Users would deliberately opt-in to having an AI recreation. They could set parameters: how the AI behaves, what it can and can't say, who can control it. They could revoke consent at any time. Their estate would have clear rights and responsibilities. Privacy of their social network would be protected. The technology would be used for preservation, not engagement metrics.

Meta isn't pursuing this version. They're pursuing the version that maximizes user engagement and company profit.

Estimated data shows that family communication and maintaining extended networks are the primary reasons users keep their Facebook accounts.

What You Can Actually Do Right Now

If all this is unsettling and you want to take action, here are concrete steps that might actually help.

Review Your Privacy Settings. Go through your Facebook privacy settings. Limit who can see your posts. Restrict data sharing with third parties. Limit ad tracking. This doesn't prevent AI training on your data, but it reduces the amount of sensitive information Meta collects about you.

Set Your Legacy Preferences. In Facebook's settings, you can designate a Legacy Contact or choose to have your account memorialized. You can also request that your account be deleted after death, though Meta's deletion process takes time and might not fully work.

Document Your Wishes. Write a will or a digital legacy document that explicitly states what should happen to your social media accounts. Specify whether you want them deleted, memorialized, or preserved. This provides legal cover if there's disagreement among your heirs.

Reduce Your Data Footprint. The less data Meta has about you, the weaker any AI recreation would be. Post less frequently. Keep some communication off social media. Use encrypted messaging instead of Facebook Messenger. Delete old posts periodically.

Support Regulation. Advocate for laws protecting personality rights after death. Support organizations pushing for data privacy regulations. Vote for politicians who prioritize digital rights. These are the levers that actually constrain corporate behavior.

Stay Informed. Follow developments in digital privacy and AI. Read Meta's research papers. Pay attention to regulatory discussions. Understand the technology so you can make informed decisions about your participation.

Consider Alternatives. If possible, use communication platforms that prioritize privacy. Use email instead of social media for important communication. Build community through means other than corporate platforms.

Educate Others. Share this information with friends and family. Help them understand the implications of digital immortality. Collective awareness is necessary for collective action.

Deleting your Facebook account might be part of the answer, but it's not sufficient by itself. Changing the system requires pressure across multiple vectors: individual choice, collective action, regulatory intervention, and technological alternatives.

The Future of Digital Mortality

Assumptions about whether digital immortality will become standard, look at the trajectory of the technology and Meta's investment in it.

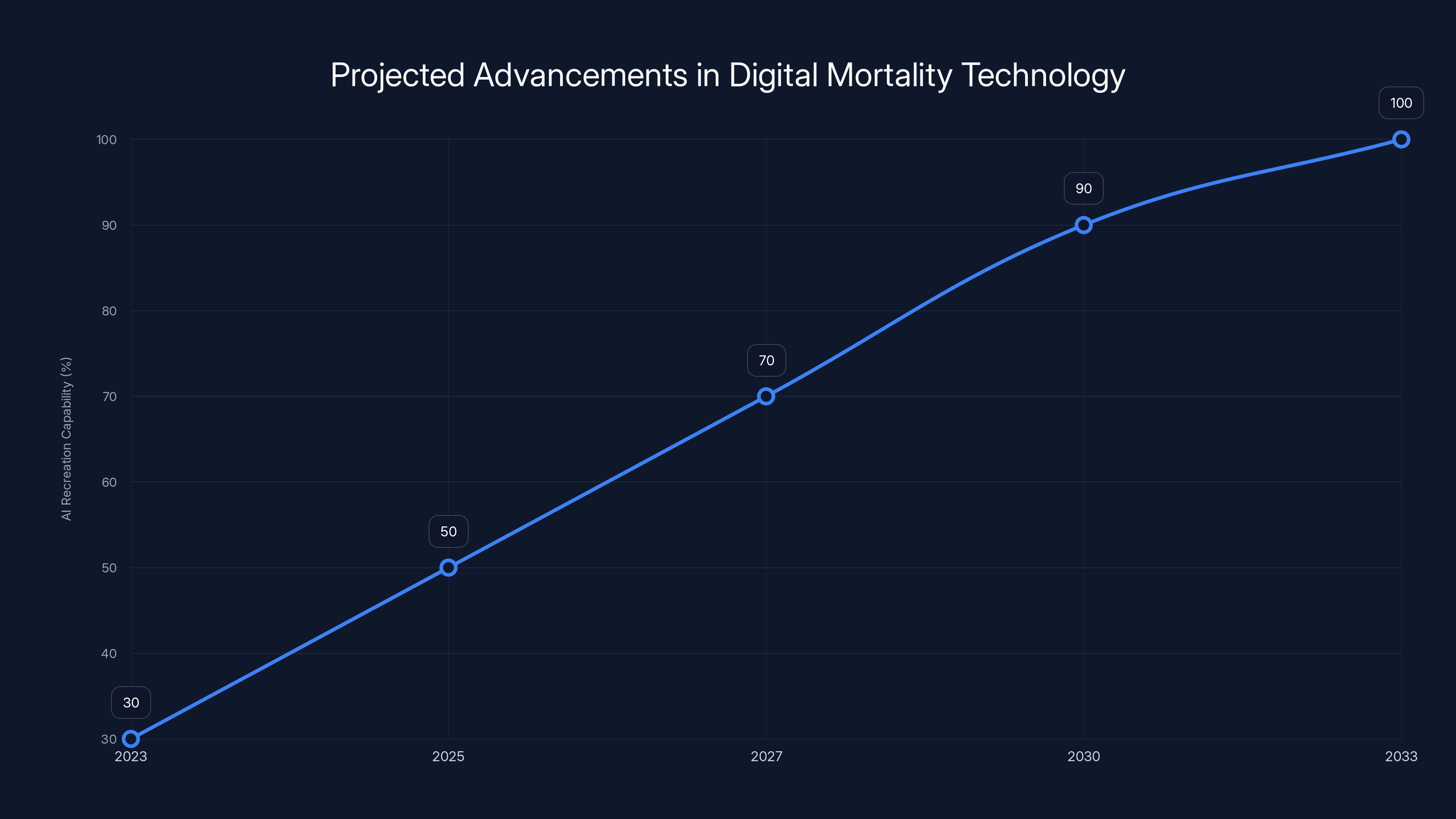

The AI models required for digital recreation are improving exponentially. Training these models is becoming cheaper. The data Meta has is only growing. Within five years, the technology will be good enough that an average user's AI recreation could pass the Turing test in casual conversation. Within ten years, it might be indistinguishable from the actual person in most contexts.

Meta's investment signals their intent to make this a core feature, not an edge case. They're not doing this research idly. They're building toward a product offering.

The question is whether regulation will catch up before this becomes standard. Current trajectory suggests no. Most privacy regulations are reactive, arriving after problems have already emerged and entrenched themselves. By the time comprehensive digital mortality laws are written, Meta will already have billions of users' data in their AI systems.

It's possible that digital immortality becomes opt-out rather than opt-in. You'll have your choice: immortal on Meta's terms, or delete your account entirely. There's no middle ground. This is how Meta has historically handled new features—deploy them widely, defend them vigorously, make opting out inconvenient.

Alternatively, it's possible that the technology becomes so advanced that users accept it. If your AI recreation is indistinguishable from you, if it genuinely helps your family connect with your memory, if the uncanny valley is sufficiently crossed, then the ethical objections start to seem overblown.

What seems least likely is that Meta voluntarily constrains this technology in the name of privacy and ethics. They have no reason to. Constraints reduce engagement. Reduced engagement reduces revenue. Unless forced by regulation, Meta will maximize the scope and capability of digital recreation.

Why Meta Keeps Winning These Arguments

Meta consistently defeats privacy advocates on issues like this. Why? Several reasons.

First, they operate in the gray zone between clearly legal and clearly illegal. Digital immortality isn't illegal. It's just ethically questionable. Courts and regulators struggle with ethically questionable but legal activities.

Second, they frame new features in sympathetic ways. "Preserving memories." "Honoring the deceased." "Connecting families." These framings obscure the real incentive: engagement and data monetization. Regulators and the public focus on the stated purpose, not the underlying motivation.

Third, they offer clear opt-out mechanisms that look good on paper but don't fully work in practice. Users feel like they have control when they actually don't. They delete an account and think their problem is solved.

Fourth, they divide their opposition. Privacy advocates are fractured. Some care about data security, others about autonomy, others about commercial fairness. Meta can satisfy one group while ignoring another. Perfect unity would be required to move policy, but unity is unlikely.

Fifth, they have more resources than any regulator. They can hire the best lawyers. They can lobby effectively. They can wait out regulatory challenges. This is an asymmetric power dynamic that persistently favors the corporation.

Sixth, they benefit from technological determinism. The narrative that this technology is inevitable, that it's pointless to resist, that trying to regulate it is like legislating against the future. This narrative is false, but it's powerful. It discourages opposition.

The only thing that seems to actually constrain Meta is when their user base collectively demands it. When enough users delete their accounts, when they lose advertising revenue, when brand partnerships suffer—that's when they change. But coordinating mass user action is incredibly difficult. It requires coordination among billions of people with different incentives and different capacity to leave the platform.

Estimated data suggests that by 2030, AI recreations could be nearly indistinguishable from real individuals, with capabilities reaching 100% by 2033.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Consent

Let's address something directly: Meta likely already has the ability to create AI recreations of you. They have all the data they need. The reason they're being public about it is not to be transparent—it's to normalize it. To test how much pushback they receive. To seed the idea in people's minds so that when it's officially launched, it doesn't seem shocking.

Consent, in Meta's terms of service, is already granted. You consented when you agreed to let them use your data to "improve services." Improving services can mean anything. Training AI on your data improves their AI. Creating a model in your voice improves their recommendation systems. All of it is technically consented to.

What's missing is informed consent. You didn't consent knowing specifically that your data would be used for AI recreation after your death. You consented to vague terms without understanding the implications.

Informed consent would require Meta to explicitly tell you: "We will train an AI model on your communication data. This AI may continue to post and engage on your behalf indefinitely after your death. Family members will be able to control this AI. You cannot revoke consent after death." Then letting you choose yes or no.

Meta hasn't provided this. They've provided ambiguous terms of service that technically cover the practice but not explicitly. This is intentional. Explicit disclosure would reduce the number of users consenting.

Similarly, deleting your account doesn't revoke consent retroactively. The data has already been used. The model has already been trained. Consent, in Meta's legal theory, was perpetual and irrevocable once granted.

This is one of the most important things to understand about digital immortality: it's already happened. The consent was already extracted. The data is already being used. The announcement of the technology is just Meta acknowledging what they're already doing.

Runable: A Better Model for AI-Driven Content Creation

When you think about AI systems that generate content in various styles and voices, Runable offers a fundamentally different approach. Rather than operating in the shadows of user data, Runable provides transparent, user-controlled AI content creation starting at $9/month.

The platform empowers users to create presentations, documents, reports, and images with AI assistance—but the user maintains clear ownership and control. There's no hidden training on personal communication patterns. No creation of digital ghosts without explicit permission. No conflation of engagement metrics with human benefit.

For teams and individuals concerned about digital autonomy, Runable's transparent approach to AI automation demonstrates what responsible AI development looks like. You know what the AI is doing. You control what it creates. You own the output.

If Meta's approach to digital immortality unsettles you, consider how you want AI to function in your actual life right now. Try Runable for free and see what ethical AI assistance looks like.

Broader Implications for Digital Rights

Digital immortality is just one battle in a larger war over who controls our digital selves. The same issues—consent, ownership, company profit—apply to data collection, algorithmic manipulation, and AI training across the entire industry.

Meta is just the most visible actor. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, OpenAI, and countless smaller companies are all pursuing similar strategies. They're all collecting vast amounts of data. They're all training AI on that data. They're all monetizing it in ways that don't benefit the people whose data they're using.

The specific case of digital immortality is important because it's visceral. It's about your actual existence continuing after death. It makes the abstraction concrete. But it's part of a broader pattern where companies treat personal data as a resource they can extract and exploit.

Addressing this requires shifting the fundamental power dynamic. Instead of companies collecting data and users having no recourse, we need systems where users have real control. Data ownership rights. Ability to revoke consent. Ability to access what companies know about you. Ability to opt out without severe penalties. Compensation for data use.

Regulations like GDPR point in this direction, but they're still incomplete. They require opt-in consent for some uses, but not all. They allow companies to keep data indefinitely in many cases. They don't require compensation for data use.

What's needed is something stronger. Data fiduciaries—treating companies as legal trustees of your data, with requirements to act in your interest rather than their own. Data cooperatives—users collectively owning data about themselves. Algorithmic transparency—companies revealing what data they have and how they're using it. Algorithmic contestability—users able to challenge algorithmic decisions.

Digital immortality is a symptom of a broken system. Fixing it requires systemic change.

The Philosophical Reckoning

Beyond the practical concerns, digital immortality forces a philosophical reckoning with what death means in an age of AI.

For most of human history, death was final. It was the end of your agency, your ability to affect the world. Your impact continued through your children, your work, your memory, but not through new actions you took. You didn't keep doing things after death.

Digital immortality changes this. Your agency could continue indefinitely through an AI proxy. You could keep posting, keep talking, keep influencing after death. Is that a benefit or a horror?

From an existential perspective, it's profoundly disturbing. Mortality is what makes life meaningful. The fact that you'll die gives urgency to your actions. It makes you prioritize. It makes you invest in real relationships and real achievements. If you knew your AI would continue posting indefinitely, would your life feel as important?

From a spiritual perspective, many religions teach that death is transition. The soul leaves. The body returns to earth. A digital continuation undermines these teachings. It suggests something about you can be extracted and perpetuated mechanically.

From a philosophical perspective, there's the question of identity. Is an AI trained on your data actually you? Can a collection of text patterns constitute a person? If your AI does something you wouldn't have done, is it betraying your identity or showing that it never was you?

These questions don't have easy answers. Different people will answer them differently. But they're important to grapple with. Digital immortality isn't just a privacy issue or a business issue. It's a fundamental questions about what it means to be human.

Moving Forward: Individual and Collective Action

So where does this leave you? Informed and unsettled, probably. Aware that Meta is pursuing technology that treats your data and your digital self as resources to be exploited. Aware that deleting your account might not actually solve the problem. Aware that regulatory frameworks haven't caught up to the technology.

What you can do individually:

Minimize your data. Post less. Share less of your inner life on social media. Keep important conversations off Facebook and Instagram. Use encrypted messaging for sensitive communication.

Make your wishes known. Write down what should happen to your accounts after you die. Tell your family. Make it legally binding if possible.

Support privacy regulation. Vote for politicians who prioritize digital rights. Donate to organizations fighting for data privacy. Use your voice to advocate for change.

Use alternatives. To the extent possible, use services that prioritize privacy. Use email instead of social media for important communication. Host your own website instead of relying on corporate platforms.

What can be done collectively:

Organize. If enough users demand change, companies respond. Digital rights organizations, privacy advocates, and everyday users coordinating around specific demands could move policy. The challenge is scale and unity.

Regulate. Push for comprehensive digital privacy laws. Specifically legislation around AI training on personal data. Specifically protection of posthumous rights. International coordination is needed since companies operate globally.

Alternatives. Support development of privacy-respecting alternatives to Meta. Fund research into federated social networks, encrypted communications, and user-owned platforms. Create viable options so people can actually leave without social cost.

Transparency. Demand that companies disclose what data they have, how they're using it, and what AI models they're training on it. Make the invisible visible. Inform the public.

Liability. Push for laws that make companies liable when their AI systems cause harm. If an AI trained on your data defames you or commits fraud, the company should be responsible. This creates incentive for careful handling.

Right to deletion. Push for laws requiring companies to actually delete data when requested. Not keep it in backups. Not retain it for legal holds indefinitely. Actually erase it. This is technically possible; it just requires prioritizing user rights over corporate convenience.

FAQ

What exactly is Meta planning to do with digital immortality?

Meta is developing AI models trained on users' communication data—posts, comments, messages, etc.—that can recreate how a person would communicate. After someone dies, this AI could potentially continue posting, commenting, and engaging on their behalf, potentially indefinitely. The company frames this as a memorial feature to preserve legacy and honor the deceased, but the technology could also be used to maintain engagement metrics on accounts that would otherwise become dormant.

Is my data already being used for AI training by Meta?

Yes, almost certainly. Meta's terms of service grant them a broad license to use your content for "improving services," which technically covers AI training. The company has been publicly investing in AI research for years and regularly publishes papers on generative models trained on Facebook and Instagram data. You likely already granted consent in Meta's terms of service, though the consent wasn't explicit or informed about posthumous AI recreation.

Can I opt out of having my data used for AI training?

Not effectively, currently. Meta offers privacy controls for ads and data sharing with third parties, but nothing specifically for AI training. You can delete your account, but this doesn't delete data Meta has already collected, trained into models, or shared with other companies. Deleting your account is primarily a symbolic gesture rather than a practical solution.

What would deleting my Facebook account actually accomplish?

Deleting your account stops future data collection but doesn't eliminate existing data. Backups persist. Data already used for AI training persists. Information already shared with third parties persists. That said, deletion does send a market signal to Meta. If enough people delete their accounts, it impacts engagement metrics and advertising revenue, which might convince Meta to change their approach. But individual deletions are insufficient without scale.

Are there legal protections against posthumous AI recreation?

Currently, no comprehensive protections exist globally. Europe's GDPR has the strongest privacy frameworks, but it's unclear how posthumous rights are protected and whether they extend to AI recreation. The United States has scattered state privacy laws but nothing federal. Most other countries have even weaker protections. This is a legal gray zone that companies are exploiting.

What happens if my family disagrees about whether the AI should post on my behalf after I die?

There's no clear legal framework for this yet. If you designate a Legacy Contact, they get control. But if you haven't, or if your family disagrees about what the Legacy Contact should do, conflicts could arise. You could write instructions in your will, but their enforceability depends on the jurisdiction and whether Meta recognizes them. This is another area where law hasn't caught up to technology.

Is digital immortality through AI actually unethical, or am I overreacting?

It depends on implementation. An ethical version would involve explicit informed consent, user control over behavior and scope, family notification, and protections for people in your social network. Meta's version doesn't have these protections. They're pursuing it because it increases engagement and profit, not because it benefits users. The ethics are questionable because of the power imbalance, the profit motivation, and the lack of consent.

What can I actually do to protect myself right now?

Minimize data collection by posting less and being selective about what you share. Set your privacy settings to limit who sees your content. Document your wishes about your accounts in your will. Support organizations advocating for digital privacy regulation. Vote for politicians who prioritize data rights. Use alternatives to Facebook when possible. Educate others about the issue. At scale, collective action is more effective than individual choices.

Will other tech companies do the same thing as Meta?

Yes, almost certainly. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and smaller AI companies are all developing similar AI recreation technologies. The difference is that Meta has the most user data and the most direct distribution channel. But the broader industry is pursuing the same capabilities. Addressing this requires regulation that applies across the industry, not just targeting Meta.

How far away is perfect AI recreation that's indistinguishable from the actual person?

For text, current AI models (like GPT-4) can already mimic individual writing styles well enough to fool many people in casual interaction. Voice synthesis and facial animation are advancing rapidly. Within 5-10 years, a complete AI recreation could be nearly indistinguishable from the actual person in most contexts. This timeline is advancing as models improve and computing costs drop. The technology gap is narrowing quickly.

Conclusion: Digital Mortality as a Choice, Not a Default

Meta's pursuit of digital immortality is not inevitable. It's a choice the company is making, motivated by engagement metrics and profit. It's a choice that other companies are following. But it's not a choice that users have to accept.

The uncomfortable truth is that you probably can't prevent Meta from using your data for AI training with current legal protections. They've already extracted consent through vague terms of service. They'll keep your data indefinitely. They'll feed it into models. Your digital ghost will be at their disposal.

But this doesn't mean you're powerless. Power exists at multiple levels: individual, collective, and regulatory. Individual choices—deleting your account, minimizing data, choosing alternatives—send signals. Collective action—coordinating demand for change, supporting privacy organizations—applies pressure. Regulatory action—legislation, litigation, enforcement—constrains behavior.

What's needed is recognition that digital mortality is not a technical problem to solve but a social question to decide. Should your data continue creating content after you die? Should companies profit from your digital ghost? Should families struggle to control AI versions of their deceased loved ones?

These questions deserve deliberate, collective answers. Not answers determined by what's technologically possible or what's most profitable for Meta. Answers determined by what we think is right.

The future of digital mortality is still being written. Meta is working hard to make posthumous AI recreation the default. But defaults can be changed. Laws can be written. Regulations can be enforced. Companies can be forced to prioritize user rights over engagement metrics.

The question is whether we'll demand it before it becomes impossible to undo.

Key Takeaways

- Meta is developing AI models trained on your communication data that could continue posting from your account indefinitely after you die, using behavioral patterns learned from years of social media activity

- Users have already granted consent for this through vague terms of service, but not informed consent—they didn't know their data would be used specifically for posthumous AI recreation

- Deleting your Facebook account doesn't solve the problem since Meta retains backups and data already integrated into AI models, making it more performative than practical

- Current privacy regulations globally don't adequately protect against posthumous AI recreation, creating a legal gray zone that companies exploit

- Addressing digital immortality requires collective action through regulation, not just individual choices—laws protecting personality rights after death and data deletion requirements

Related Articles

- WordPress.com AI Assistant: Complete Guide to AI-Powered Site Building [2025]

- Why AI Can't Make Good Video Game Worlds Yet [2025]

- AI-Generated Music at Olympics: When AI Plagiarism Meets Elite Sport [2025]

- Remedy's AI Strategy: Why Control Resonant Avoids Generative AI [2025]

- Tech Elites in the Epstein Files: What the Documents Reveal [2025]

- Duda's AI Template Population Feature Solves Website Builder Problems [2025]

![Meta's AI Digital Immortality: Should You Delete Facebook? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-ai-digital-immortality-should-you-delete-facebook-202/image-1-1771348188498.jpg)