Microsoft's AI Content Licensing Marketplace: The Future of Publisher Payments [2025]

For years, AI companies have trained their models on massive amounts of internet content without paying creators a dime. Publishers watched their work fuel billion-dollar models, then watched their traffic disappear as AI provided answers without clicking through. It's been a one-way street, and publishers are finally pushing back.

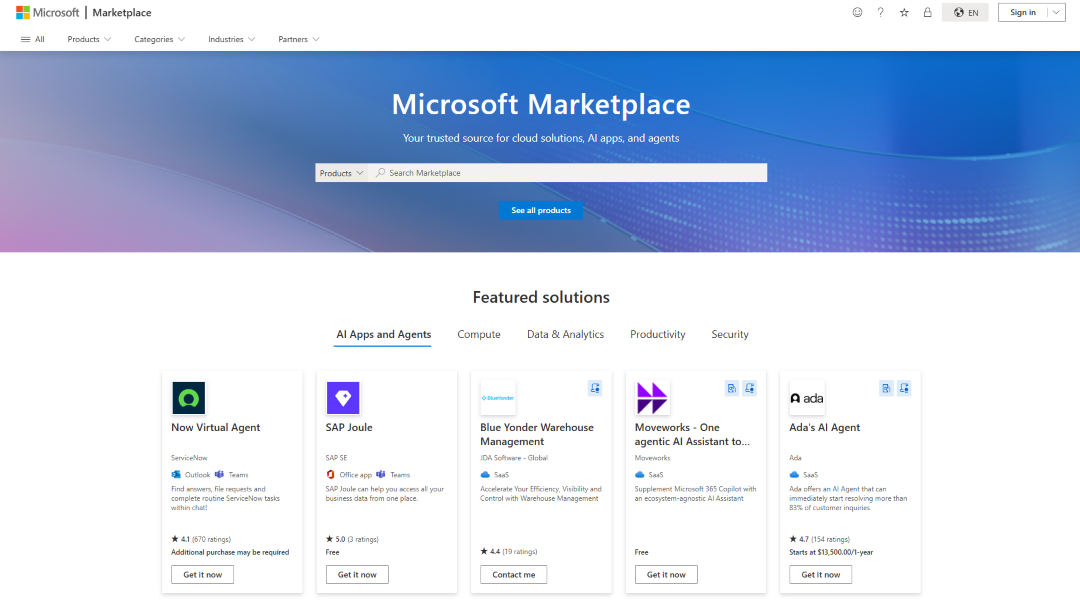

That's where Microsoft's new Publisher Content Marketplace comes in. It's essentially an app store for AI training data, where publishers can list their content with clear licensing terms, and AI companies can browse, negotiate, and pay for legitimate access to premium material.

This isn't a small move. It's a fundamental shift in how AI models get built, how publishers get compensated, and what "fair use" means in the age of generative AI. For the first time, there's a structured way for AI companies to pay for content at scale instead of scraping it for free.

Let me walk you through what this means, why it matters, and how it changes the game for everyone involved.

TL; DR

- Publisher Content Marketplace: Microsoft's new platform lets publishers set licensing terms for AI training, creating a direct marketplace for content access

- Payment Structure: AI companies pay based on delivered value and usage, giving publishers usage-based reporting to set better prices

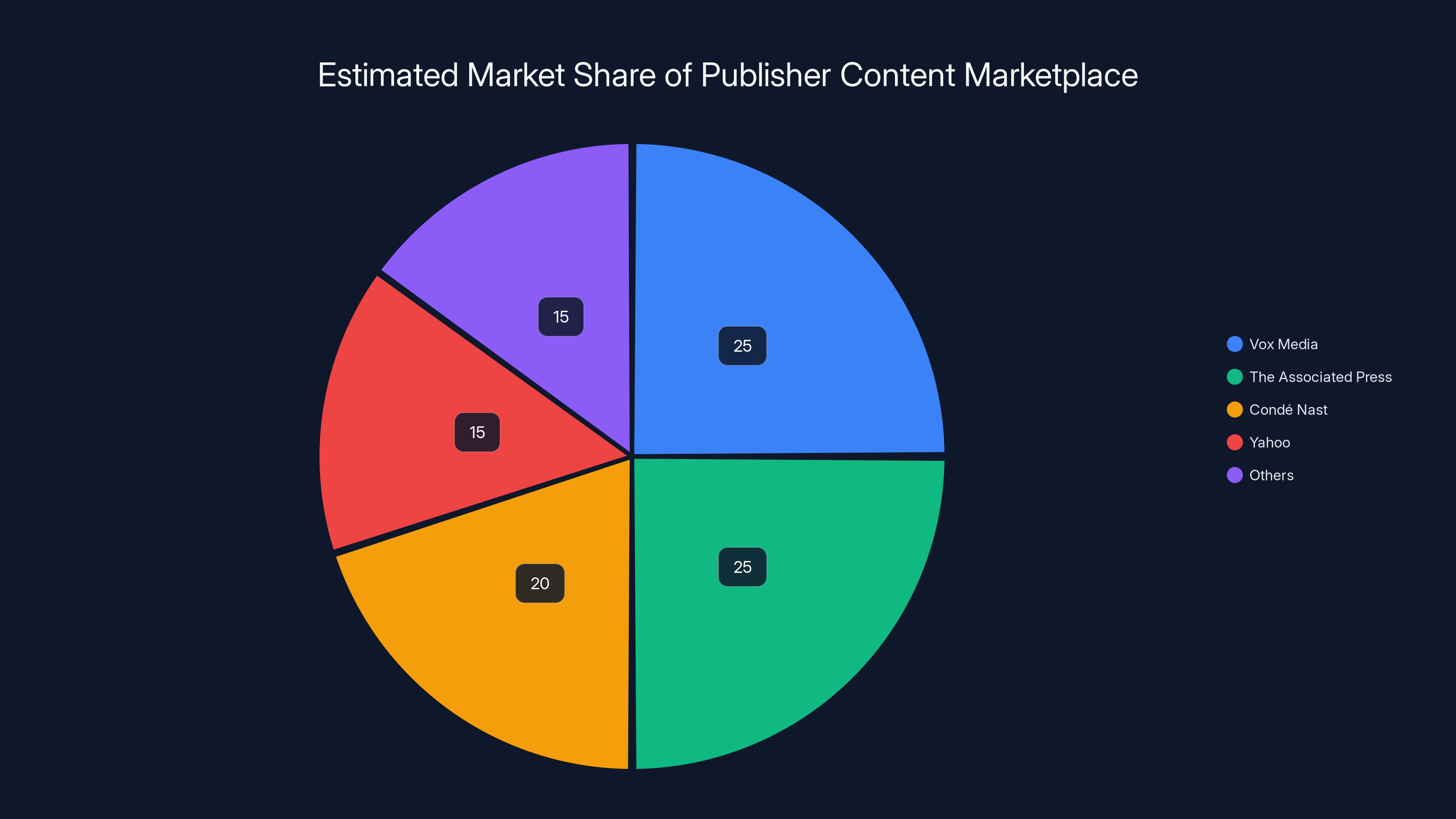

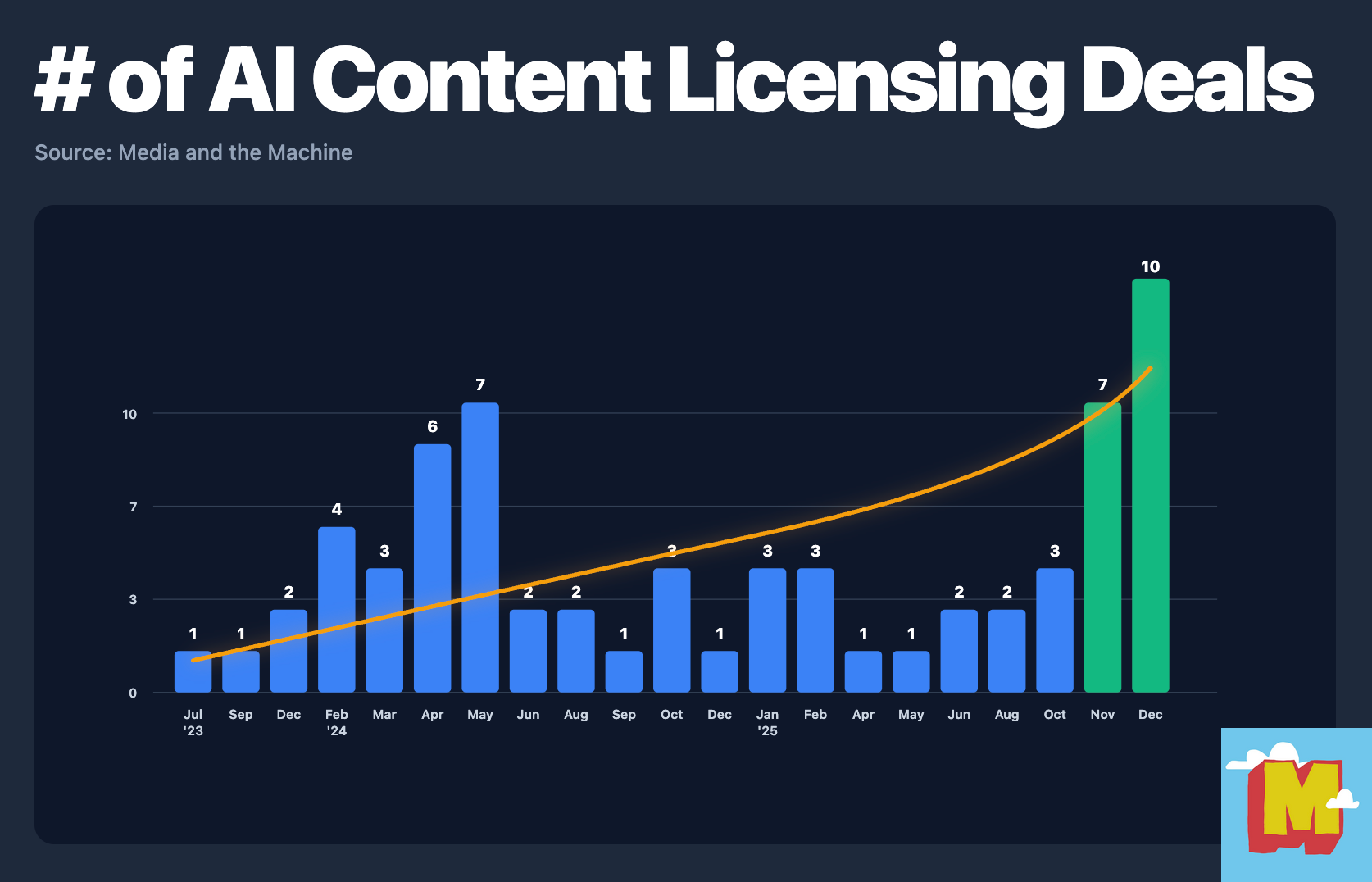

- Industry Participation: Major publishers including Vox Media, The Associated Press, Condé Nast, and others are co-designing the platform

- Licensing Standard: The marketplace complements initiatives like Really Simple Licensing (RSL), though exact integration details remain unclear

- Scalability Goal: Microsoft says the PCM will support publishers of all sizes, from major organizations to independent publications

Estimated data shows that Vox Media and The Associated Press each hold a 25% share in the Publisher Content Marketplace, with Condé Nast and Yahoo also being significant players. Estimated data.

What Exactly Is the Publisher Content Marketplace?

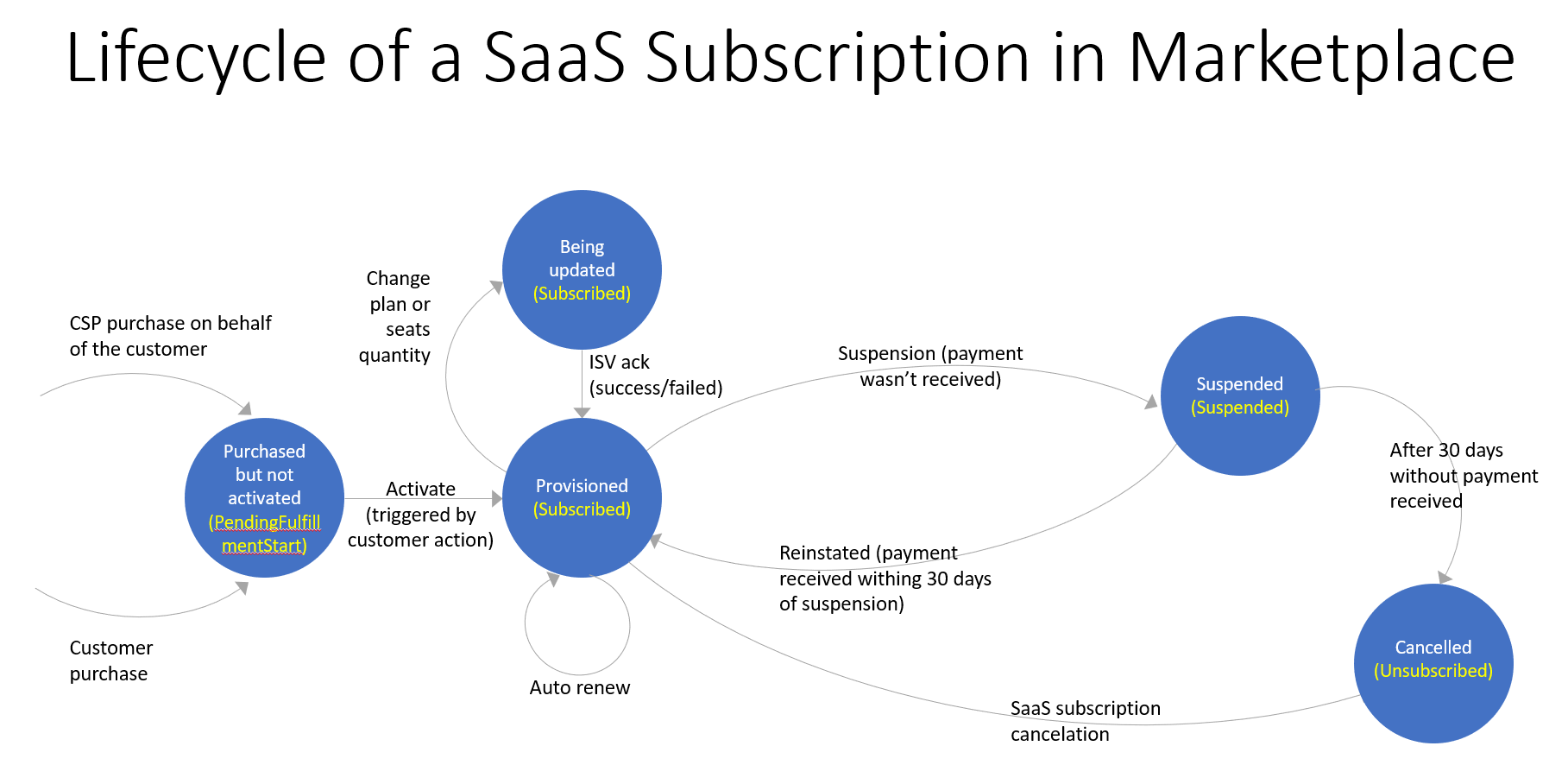

The Publisher Content Marketplace (PCM) is Microsoft's new licensing hub designed to solve a specific problem: AI companies need quality content to train better models, but publishers have no way to get paid for it.

Here's how it works in practice. A publisher like The Associated Press logs into the platform and lists their content catalog with specific licensing terms. They might say something like: "You can use 50,000 articles monthly for $50,000." Or: "Premium investigative pieces cost 10x the standard rate." They set the rules.

Meanwhile, an AI company like Open AI or Anthropic browses the marketplace, compares licensing terms across publishers, and clicks "add to cart." They get instant access to content for training or grounding their models. No legal negotiation. No six-month contract cycle. Just clear terms and immediate execution.

The genius part is the feedback loop. Publishers get usage-based reporting showing exactly how much content was actually used, by which AI models, for what purposes. This data lets publishers understand their content's real value. Over time, they can adjust pricing based on actual demand instead of guessing.

Microsoft has been co-designing this with heavyweight publishers including Vox Media, The Associated Press, Condé Nast, and others. Yahoo is already onboarded. The platform is in pilot phase but expanding.

The PCM represents something fundamentally different from how content licensing worked in the pre-AI era. In the old world, a newspaper licensed content to a wire service or a news aggregator, and those companies redistributed it. The model worked because humans read the articles. In the AI world, machines train on the articles, then answer questions about them directly, eliminating the need for readers to visit the original publisher's site.

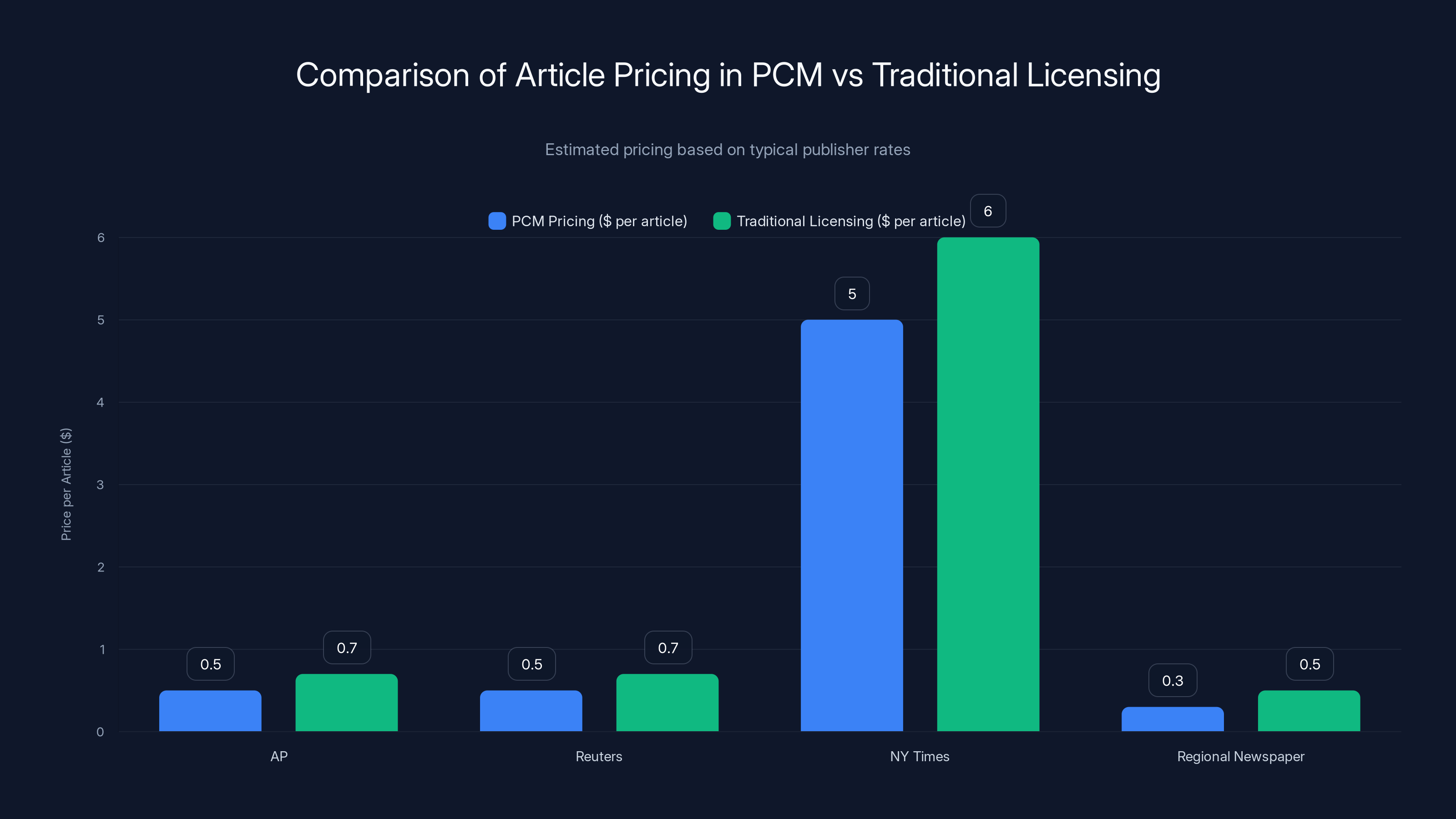

PCM offers faster transactions but may lead to lower pricing due to transparency and competition. Estimated data shows traditional licensing can command higher rates for premium content.

Why Publishers Need This (And Why They've Been Fighting)

The math of the AI boom has been brutal for publishers. The Verge and other publishers built their businesses on a simple equation: create content that readers want, the readers click through, we sell ads. Traffic drove revenue.

Then Chat GPT launched in November 2022, and suddenly readers could get answers without visiting the publisher's site. "What's the latest climate research?" Chat GPT answers directly, citing nothing. "Explain quantum computing." Chat GPT explains, no link to the article that informed it.

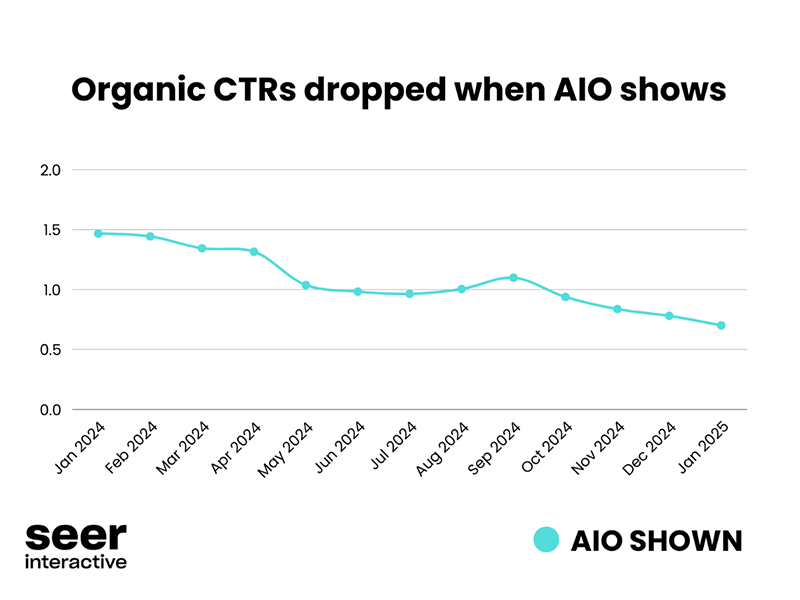

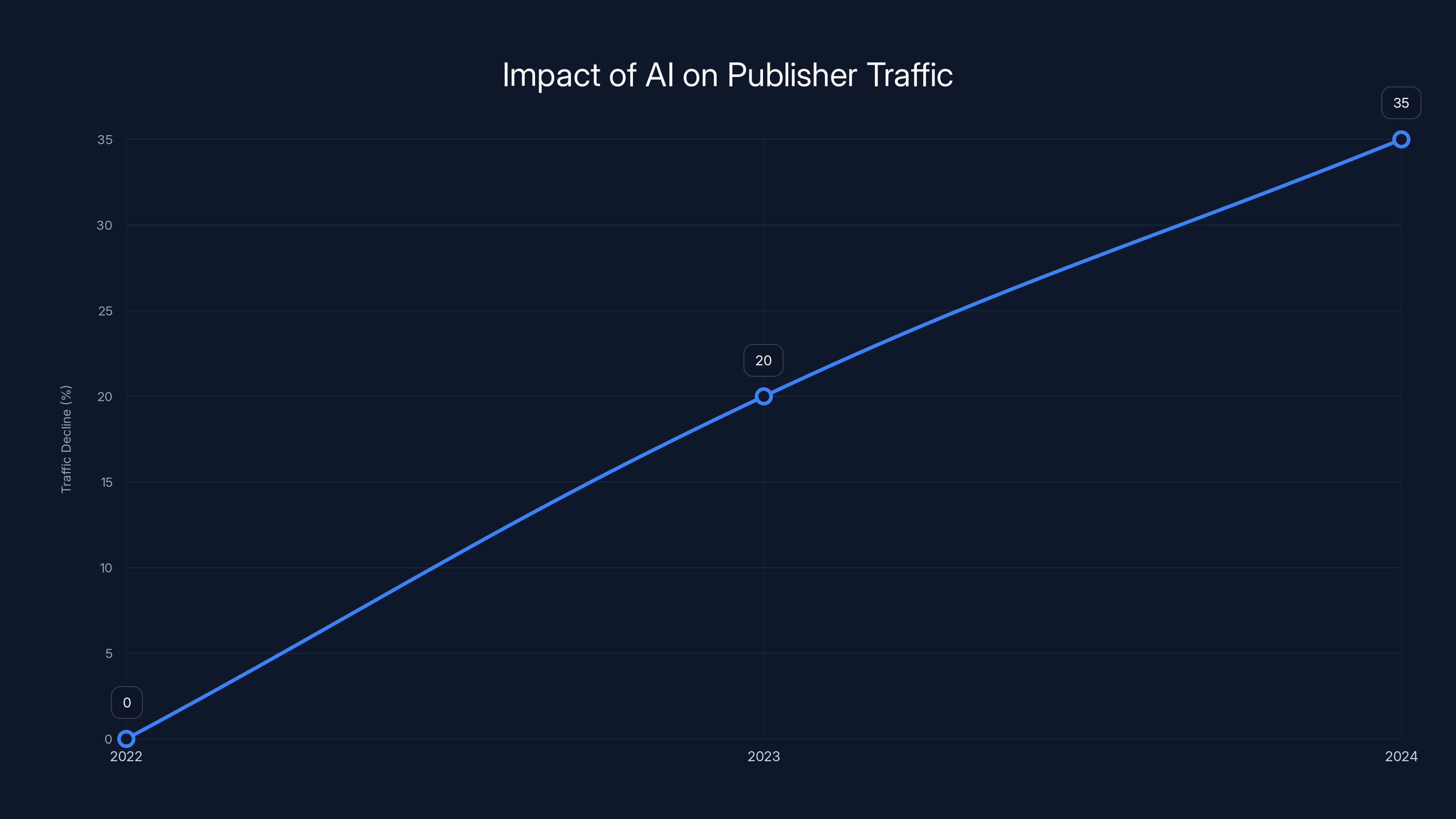

Publishers started seeing traffic drops. Not small ones. Major ones. The Verge reported in early 2024 that many publishers were seeing 5-40% declines in referral traffic from AI search products. That's not noise. That's existential.

Simultaneously, Open AI, Google, and Microsoft were scraping that same publisher content without permission to train their models. The New York Times trained the models. The Times got nothing. Open AI got a $80 billion valuation.

Publishers fought back. The New York Times sued Open AI and Microsoft. The Intercept sued both companies. The Verge's parent company Vox Media pursued licensing deals. The industry started asking: why are we letting this happen for free?

The PCM is Microsoft's answer to these fights. Instead of asking publishers to sue, Microsoft is creating a path to paid licensing. It's saying: "Yes, AI companies need your content. Here's a marketplace where you can charge for it."

From the publisher's perspective, this is infinitely better than litigation. A lawsuit against Open AI takes years and costs millions, and the outcome is uncertain. A licensing deal on the PCM generates revenue immediately. You set the price. You get usage reports. You move on.

The Economic Model: How AI Companies Pay, How Publishers Profit

The PCM's payment structure is novel because it ties compensation to actual value delivered. This is different from old licensing models where a newspaper might pay a wire service a flat annual fee regardless of usage.

Here's the framework: Publishers set licensing terms on the platform. AI companies can see those terms instantly. When an AI company uses a publisher's content to train a model or ground responses, that usage is tracked and reported. The AI company pays based on what they actually used.

Microsoft describes this as "publishers will be paid on delivered value." What does that mean exactly? The details aren't completely clear yet, but the concept is straightforward.

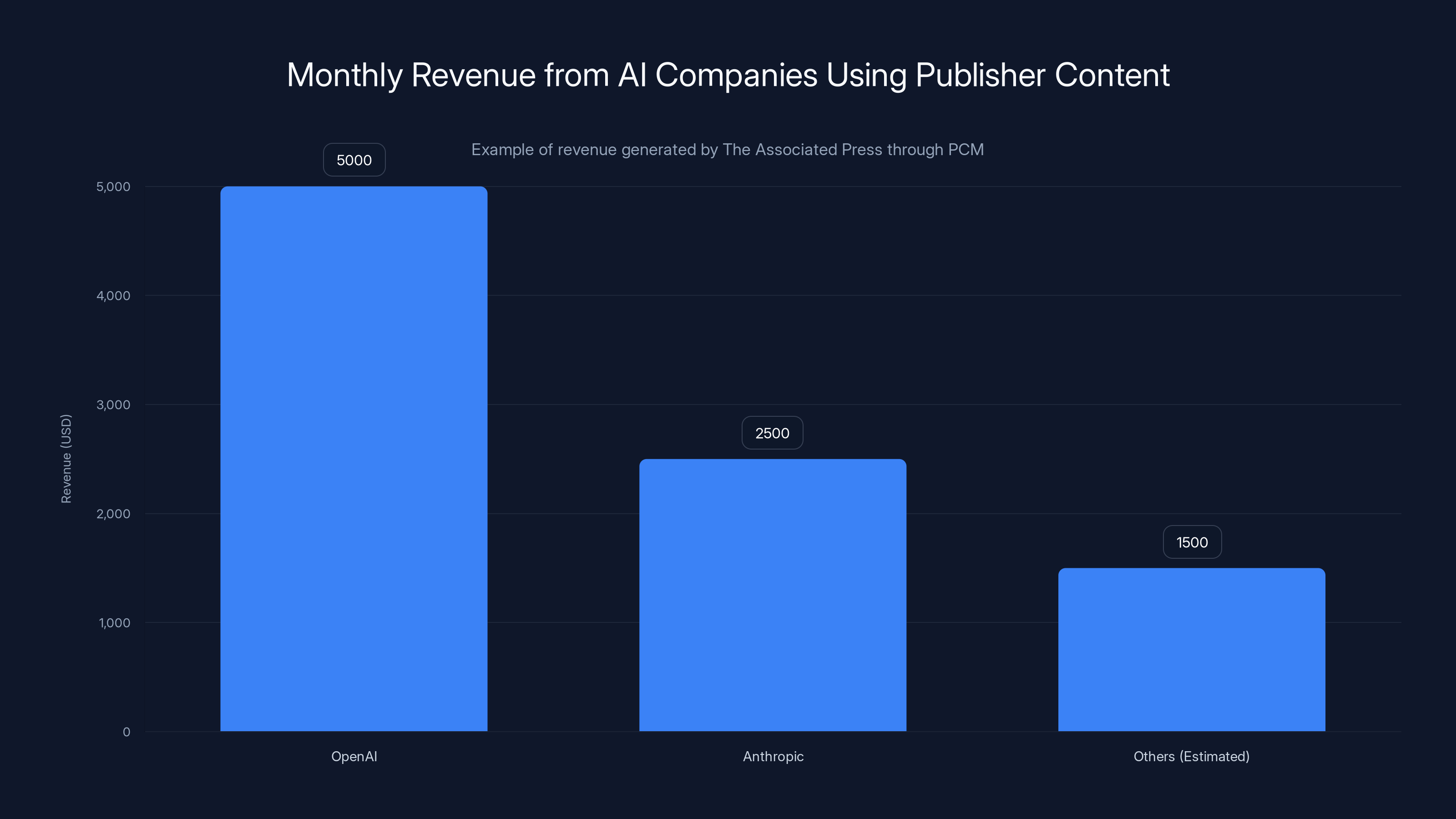

Let's model an example. Imagine The Associated Press lists 100,000 news articles on the PCM. The AP sets the terms at

The beauty here is transparency. Publishers see exactly which content gets used and how often. Over time, they learn: "Our business reporting generates 3x the usage of our sports coverage. Let's charge more for business." Or: "AI companies prefer recent articles over archived pieces. Let's adjust pricing to reflect that."

This creates a pricing market where value actually matters. Before the PCM, there was no market for publisher content and AI training. It just happened, for free. Now there's price discovery. Reuters's investigative journalism might command a 5x premium over a wire service piece. An exclusive New York Times scoop might command 10x.

For AI companies, this is actually a win too. Instead of getting caught training illegal models on stolen content, they can now license content legally, demonstrate compliance, and justify that licensing to their users and investors. An AI model trained on licensed content is a much safer product from a legal standpoint.

Microsoft's positioning of the PCM emphasizes this mutual benefit. "Creators get paid for their work. AI builders get legal access to quality content. Users get better products because the content is curated and licensed, not scraped and stolen."

The question is whether the economics work at scale. An AI company training a large model might need billions of pieces of content. At $0.50 per article, that's... a lot of money. But it's better than losing a lawsuit, and it's better for publishers than getting zero.

Estimated data shows a significant decline in publisher traffic due to AI search products, with a drop from 0% in 2022 to 35% by 2024.

The Real Problem: The "Open Web" Model Is Dead

Microsoft makes an interesting point in their PCM announcement. They write: "The open web was built on an implicit value exchange where publishers made content accessible, and distribution channels like search helped people find it. That model does not translate cleanly to an AI-first world, where answers are increasingly delivered in a conversation."

This is the core insight. The old model worked because Google Search sent traffic to publishers. You searched "how to fix a leaky faucet," Google showed you a link to an article, you clicked it, you read it, the publisher made ad revenue. Everyone won.

In an AI-first world, you ask Chat GPT "how do I fix a leaky faucet," and Chat GPT gives you step-by-step instructions without mentioning any source. You never click through. The publisher makes zero revenue. Chat GPT's owner made zero payment to the publisher.

This breaks the value chain. Publishers created the content. They should benefit from it being used. But in the conversational AI model, they don't.

The PCM is essentially an attempt to build a new value exchange. Publishers say: "You want our content? Here's the marketplace. Here are our terms. You agree or you don't. But you're not scraping for free anymore."

The challenge now is whether AI companies will actually use the PCM for training, or whether they'll just keep doing what they've been doing (claiming some unclear form of fair use defense). The PCM only works if AI companies choose to participate.

Microsoft's leverage here is interesting. Microsoft owns Bing, invests in Open AI, and has every incentive to say "we're the company that built a marketplace." If Open AI uses the PCM, other AI companies follow. If Open AI ignores it, the whole thing collapses.

The Really Simple Licensing Standard and How It Fits In

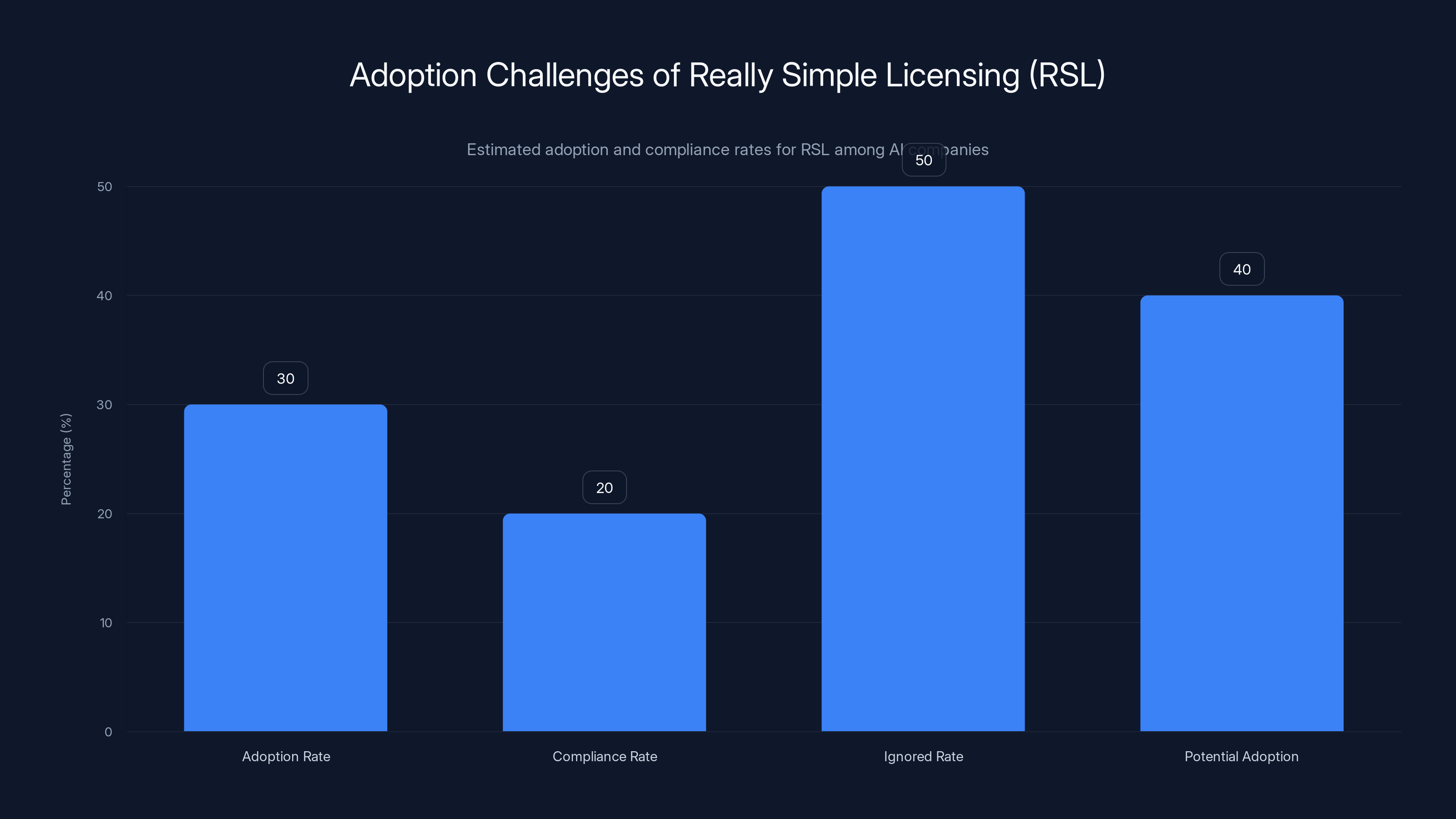

Before the PCM, there was an attempt to solve this problem called Really Simple Licensing (RSL). It's an open standard built by publishers to define how bots should behave on publisher sites.

RSL works like this: A publisher adds an RSL tag to their website that says something like: "Bots can access 10 articles per day without payment, but if they want more, they need to pay $100/month." The bot sees the tag and respects the limit. It's like a digital version of "Please respect our terms."

The Verge reported on RSL becoming official in early 2024, but the standard has struggled with adoption. AI companies don't universally honor RSL tags because there's no enforcement mechanism. A bot can just ignore the tag and scrape anyway.

What's unclear is how the PCM integrates with RSL. Do they work together? Does the PCM subsume RSL? Does RSL remain an option for publishers who want to set terms on their own site, while the PCM is for publishers who want to list on a marketplace?

Microsoft didn't clarify this in their announcement, and The Verge (the publication) reached out to Microsoft for more info but didn't hear back immediately. This is a significant gap because RSL advocates would want to see the PCM enhance RSL, not replace it.

The likely scenario is that RSL and the PCM will coexist. RSL is a way for publishers to set baseline terms on their own properties. The PCM is a marketplace for publishers who want broader AI company access. They're complementary tools, not competing ones.

But again, the details matter here, and Microsoft hasn't been explicit. As the PCM rolls out of pilot and into wider availability, publishers and AI companies will need clear guidance on how these standards interact.

The Associated Press generated

Who's Involved: The Power Players

Microsoft says it's been co-designing the PCM with major publishers, and the list is telling. Vox Media (which owns The Verge), The Associated Press, Condé Nast, and others are involved.

These are the publishers with leverage. They have massive content libraries, premium brands, and legal teams willing to fight. They're the ones who sued Open AI. Now they're part of designing the licensing framework.

The fact that Yahoo is already onboarded is noteworthy. Yahoo hosts a ton of news content and has long relationships with publishers. Their participation gives the PCM distribution and legitimacy from day one.

What's missing from the announcement is clarity on smaller publishers and independent writers. Microsoft says the PCM will "support publishers of all sizes, including large organizations and independent publications." That's good to hear, but how? Will there be a bulk-licensing option? Will independent writers have individual accounts, or do they have to go through an aggregator?

This is crucial because independent journalists and smaller publishers have suffered the most from AI content scraping. They don't have legal teams or PR departments. They just lost traffic and made no money. If the PCM is only accessible to major publishers, it doesn't solve the broader problem.

Legal Implications: The Lawsuit Problem

The PCM exists partly because publishers are suing AI companies. The New York Times has a major case against Open AI and Microsoft. The Intercept filed suit. Other publishers are considering litigation.

Does participation in the PCM affect those lawsuits? Can a publisher sue Open AI while also licensing content to them on the PCM? Or does licensing imply acceptance of past use?

These are complex questions and the legal landscape is still forming. Presumably, licensing agreements would have clear terms about past vs. future use, and about how licensing relates to pending litigation. But until we see actual contracts, we're speculating.

What's clear is that the PCM is Microsoft's attempt to get ahead of this legally. If Open AI uses the PCM to license content going forward, they can point to the PCM as evidence of good faith. Future use is licensed. They're not scraping anymore. Past use is a different question, but at least the company looks responsible.

Publishers benefit too. If they opt into the PCM and start getting licensing revenue, that's evidence that they were harmed by past unlicensed use (strengthening damages claims) while also demonstrating they have a remedy (the PCM itself).

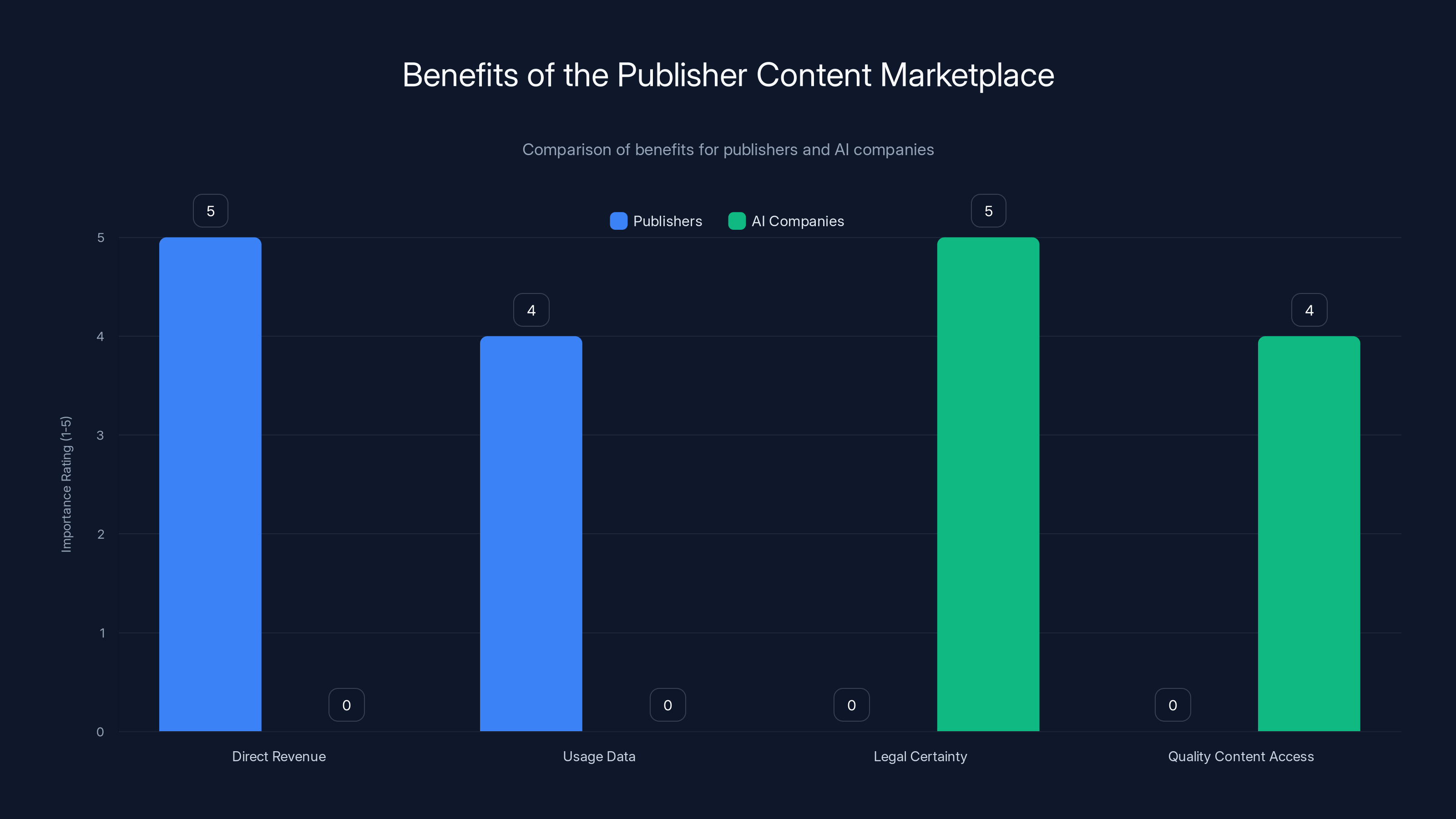

The Publisher Content Marketplace offers significant benefits to both publishers and AI companies, with direct revenue and usage data being crucial for publishers, while legal certainty and quality content access are key for AI companies.

The Broader AI Governance Conversation

The PCM is one piece of a larger conversation about how AI should be governed and how creators should be compensated in the AI age. This conversation is happening globally.

In Europe, the AI Act requires transparency about training data. In the US, Congress has discussed content creator protection bills. The Writers Guild of America fought for AI protections in recent contracts.

The PCM is one model: a marketplace where creators set terms and AI companies negotiate. But it's not the only model. Some people argue for mandatory licensing pools. Others argue for individual creator rights management. Still others argue that scraped content is fair use and compensation is unnecessary.

The PCM represents Microsoft's bet on the marketplace model. It's saying: decentralized, voluntary, market-driven licensing is better than government mandates or litigation warfare.

That might be true. Or it might mean that only big, well-resourced publishers get paid, while everyone else gets screwed. The answer depends on execution.

How the PCM Compares to Other Licensing Models

Content licensing for digital use isn't new. What's new is doing it at AI scale and speed.

Traditionally, licensing works like this: A publisher and a platform negotiate a contract. Lawyers get involved. It takes months. The contract covers specific terms. Usage is monitored. Payments are made quarterly.

The PCM attempts to compress this from months to minutes. Publishers list terms. AI companies browse and click. Boom, deal done.

This is faster, but it might be less lucrative. In traditional licensing negotiations, publishers with leverage (like The New York Times) can demand premium rates because they have scarce, high-quality content. In a marketplace, there's price transparency and downward pressure on rates.

Say AP charges

The New York Times might charge $5 per article because their journalism is premium. That works for them. But a regional newspaper might struggle to charge anything more than commodity rates.

This is a tradeoff. The PCM democratizes access to licensing (any publisher can list content), but it also commoditizes content (publishers compete on price). Whether that's good or bad depends on your perspective.

The adoption and compliance rates for RSL are low, with a significant portion of AI companies ignoring the standard. Estimated data.

Integration with AI Training Workflows

For AI companies, the PCM needs to integrate cleanly into their training pipelines. That's a technical and operational question that's not yet answered.

Today, an AI company training a model might use a web scraper to download billions of articles, parse them, clean them, and ingest them into training data. That happens on the company's infrastructure.

With the PCM, the workflow changes. An AI company identifies data sources on the marketplace. They purchase or license access. They still need to download, parse, and ingest the data. But now the data is licensed, and usage is tracked.

How is usage tracked? Is there a PCM API that logs requests? Do publishers get real-time dashboards showing which content is being used? Or is it batch reporting after the fact?

These operational details matter enormously for whether the PCM actually works. If tracking is manual and slow, AI companies won't use it. If it's automated and real-time, adoption is much more likely.

Microsoft hasn't provided technical documentation yet, so we're in the dark. As the platform moves out of pilot, expect these details to emerge.

The Future: Will the PCM Become the Standard?

Here's the billion-dollar question: Will AI companies actually use the Publisher Content Marketplace, or will they ignore it and keep scraping?

If Open AI, Anthropic, Google, and other major AI labs embrace the PCM, it becomes the standard. Publishers start licensing on the platform. Revenue flows. The lawsuits settle or disappear.

If AI companies largely ignore the PCM and keep scraping (claiming fair use), the platform becomes a failed experiment. Publishers continue suing. The legal landscape remains chaotic.

Microsoft's leverage is that they control Bing and Open AI (through investment). If they force the issue and say "we're using the PCM for our AI products," others will follow. But if Open AI resists and Google does their own thing, the PCM becomes fragmented.

My bet? It becomes a standard, but only for "good actor" companies and for forward-looking licensing. Companies concerned about legal risk will use it. Companies that don't care about legal risk will ignore it. Most likely, Open AI will participate partly (licensing some premium sources) while also claiming fair use (for broad scraping).

Publisher Strategy: How to Navigate This

If you're a publisher, the PCM presents a strategic choice. Do you participate? At what price? With what terms?

Participation is probably good. A marketplace is better than litigation or negotiating individually with 50 AI companies. You set the terms once, and buyers come to you.

Pricing is tricky. Charge too little, and you leave money on the table. Charge too much, and AI companies will try to find cheaper sources or scrape illegally. You need to understand your content's marginal value to AI systems. Investigative journalism has high value. Breaking news has high value. Commodity listicles have low value.

Term should be clear. Will you allow unrestricted commercial use of your content for model training? Will you exclude specific uses (like training models to write in your house style)? Will you require attribution or sourcing? These matter.

You should also monitor competitors. If AP is undercutting your price, that's useful data. Adjust accordingly.

And don't abandon RSL or other legal protections just because you're on the PCM. The marketplace is voluntary. You need backup strategies.

The Independent Creator Problem

One significant gap in the PCM announcement is clarity on individual creators and independent publishers. The marketplace was co-designed by major publishers. It's optimized for them.

But what about freelance journalists, independent writers, and niche publishers with small archives? They were scrapped by Chat GPT too. Do they get a seat at the table?

Microsoft says the PCM will support "publishers of all sizes, including independent publications." But the mechanics are unclear. Can a solo writer list their Substack on the PCM? Can a small local news site join as a collective?

If the PCM only works for enterprises with dedicated licensing teams, it reproduces the same inequality that plagued digital media for years. Big publishers get revenue. Everyone else gets commoditized.

For the PCM to be truly impactful, Microsoft needs to create tools for small creators. Maybe a simplified onboarding flow. Maybe an aggregator service that bundles independent content. Maybe micropayments instead of bulk licensing.

Without that, the PCM is just a tool for the rich.

The Copyright and Fair Use Question Still Looms

Here's what the PCM doesn't solve: the question of whether scraping for AI training is legal without licensing.

Open AI and Microsoft maintain that training on publicly available content is protected by fair use. The New York Times and others maintain it's not. We won't know until courts decide.

If courts rule that scraping for AI training is fair use, the PCM becomes optional. AI companies can choose to license (to be good actors) but don't have to. The market is voluntary but lopsided.

If courts rule that licensing is required, the PCM becomes essential. AI companies that want to train models legally must use the PCM or negotiate individual deals. The market is mandatory.

This legal uncertainty is actually in the PCM's favor. AI companies facing litigation risk will be more willing to participate in a marketplace that proves they're licensing content legitimately.

Comparison With Other Content Licensing Markets

This isn't the first time the web has tried to build licensing markets for content. The history offers lessons.

Music licensing went through this. Initially, music was shared freely online through Napster and others, with minimal payment to artists. Over time, licensing services like Spotify built payment infrastructure. Artists now get paid per stream (though often not much).

The PCM could follow a similar arc. Initial chaos and piracy (which is what's happening now). Then licensing marketplaces emerge (the PCM). Then industry standards solidify around the marketplaces.

But it could also fail. Video licensing via services like You Tube didn't necessarily pay creators fairly. Influencer content is often used in compilations without proper compensation. Digital content licensing is historically messy.

What Happens Next: Timeline and Expectations

Microsoft is currently in pilot mode with the PCM. Yahoo is onboarded. Major publishers are co-designing. That's happening now, in early 2025.

The next phase is wider rollout. Expect the PCM to open to more publishers (both large and independent) in the coming months. Expect pricing to stabilize as publishers learn what their content is worth. Expect Open AI, Anthropic, and other AI labs to announce integration with the PCM (or announce they're not integrating, which would be telling).

We'll also see legal proceedings continue. The New York Times' lawsuit against Open AI and Microsoft will likely move toward settlement or judgment. The PCM may influence those outcomes.

By end of 2025, we should have a much clearer picture of whether the PCM is working. Are publishers making meaningful revenue? Are AI companies actually using it? Is the platform accessible to independents or just enterprises?

If the answers are yes, the PCM becomes a model that other countries and platforms adopt. If no, we're back to litigation and regulatory approaches.

The Bigger Picture: AI, Ownership, and Compensation

The PCM is really about a fundamental question: In an AI economy, who owns content, and who gets paid when that content is used?

In the industrial economy, ownership was clear. You built a factory, you owned it. You wrote a book, you owned it. Compensation was straightforward.

In the digital economy, ownership got murkier. You posted a photo to social media, but the platform owned the terms of use. You wrote an article, but aggregators redistributed it. The web became a vast commons where the rules weren't clear.

In the AI economy, ownership and compensation become even more fraught. An AI model trained on your content is a new thing. It's not a copy of your content. It's a system that learned from your content. Do you own the model? Do you deserve compensation? Should you have the right to opt-out?

The PCM represents one answer: Yes, you should be compensated. You should have a marketplace where you set terms. AI companies should negotiate with you fairly.

But there are other possible answers. Some argue that AI training should be free and unencumbered because it advances technology for everyone. Others argue that creators should have blanket opt-out rights and AI companies should only train on explicitly-consented content. Others argue for licensing pools (like ASCAP for music) where a central authority negotiates on creators' behalf.

The PCM is Microsoft's bet. As the technology matures and more courts rule on fair use, we'll see if that bet pays off.

FAQ

What is the Publisher Content Marketplace?

The Publisher Content Marketplace (PCM) is Microsoft's new licensing platform that allows publishers to set terms for how AI companies can access and use their content for training and model grounding. Publishers list their content with specific pricing and usage rules, while AI companies can browse terms, purchase licenses, and track usage through the platform.

How does the Publisher Content Marketplace work?

Publishers create accounts on the PCM and list their content libraries with licensing terms, such as price per article or maximum monthly usage limits. AI companies browse the marketplace, review the terms, and purchase or license content they want to use. Usage is tracked and reported back to publishers, providing them with data to understand demand and adjust pricing accordingly.

What are the benefits of the Publisher Content Marketplace?

For publishers, the PCM creates a direct revenue stream from AI companies instead of allowing free scraping, provides usage data to inform pricing strategy, and offers an alternative to costly litigation against AI companies. For AI companies, it provides legal certainty, access to quality licensed content, and operational simplicity compared to individual contract negotiations. Users benefit from AI models trained on legal, quality content rather than scraped material.

How does the PCM differ from Really Simple Licensing (RSL)?

RSL is a standard that publishers can embed in their website to set baseline rules for bot access (e.g., "max 10 articles per day unless you pay"). The PCM is a centralized marketplace where publishers list content for licensing to AI companies. The two are likely complementary. RSL provides baseline protection on a publisher's own site, while the PCM enables broader licensing for reach and revenue.

Which publishers are involved in the PCM?

Microsoft co-designed the PCM with major publishers including Vox Media, The Associated Press, Condé Nast, and others. Yahoo is already onboarded as a partner. More publishers and independent publications are expected to join during wider rollout.

How will AI companies be charged through the PCM?

Pricing models on the PCM are expected to be usage-based, with publishers setting rates for content access. An AI company might pay per article used, per month of access, or based on a tiered pricing model depending on usage volume. Publishers receive usage reports showing exactly what content was accessed and by whom, allowing them to adjust pricing over time based on demand.

Does participation in the PCM affect ongoing lawsuits between publishers and AI companies?

This remains legally unclear and will depend on the specific terms of licensing agreements and how courts interpret the relationship between past unlicensed use and future licensed use. Publishers should consult legal counsel about how joining the PCM may affect pending litigation, and licensing terms should explicitly address whether they cover only future use or past use as well.

What happens if AI companies refuse to use the PCM?

If major AI companies decline to use the PCM, it becomes less valuable and publishers must rely on other approaches such as litigation, regulatory action, or individual licensing negotiations. However, Microsoft's control of Open AI and Bing gives the company significant leverage to encourage adoption by major AI labs.

Will independent writers and small publishers be able to participate in the PCM?

Microsoft states that the PCM will "support publishers of all sizes," but the specific mechanics for independent creators and small publications are not yet clear. It remains to be seen whether there will be simplified onboarding for individuals or aggregator services that bundle independent content for licensing.

Final Thoughts

The Publisher Content Marketplace represents a turning point in how AI models get trained and how creators get compensated. For the first time, there's an official platform where publishers can set terms for AI access instead of fighting through lawsuits or accepting free scraping.

But the PCM is only the beginning. The real work happens now: publishers need to list content at the right prices, AI companies need to actually use the platform, independent creators need a path to participation, and courts need to rule on fair use to set the legal backdrop.

If the PCM succeeds, it becomes a model for content licensing across industries. If it fails, we're headed for years of litigation and regulatory chaos. The outcome isn't predetermined. It depends on whether Microsoft, publishers, and AI companies can align their incentives.

One thing is certain: the era of free AI training on scraped content is ending. How publishers and creators benefit from that transition is the question the PCM is trying to answer.

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft's Publisher Content Marketplace creates the first structured platform for AI companies to legally license content from publishers at scale

- The PCM solves a critical revenue problem for publishers by replacing free content scraping with usage-based licensing payments

- Major publishers including Vox Media, Associated Press, and Condé Nast are co-designing the platform, signaling serious industry adoption

- The traditional publisher business model is broken by conversational AI that answers questions without directing traffic to source sites

- Participation in PCM is likely to become standard for AI companies concerned about legal risk, though fair use litigation will ultimately determine whether licensing becomes mandatory

Related Articles

- AI Safety by Design: What Experts Predict for 2026 [2025]

- Amazon's CSAM Crisis: What the AI Industry Isn't Telling You [2025]

- Inside Moltbook: The AI-Only Social Network Where Reality Blurs [2025]

- Apple Xcode Agentic Coding: OpenAI & Anthropic Integration [2025]

- AI Agents Getting Creepy: The 5 Unsettling Moments on Moltbook [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Image Generation Remains Uncontrolled [2025]

![Microsoft's AI Content Licensing Marketplace: The Future of Publisher Payments [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-ai-content-licensing-marketplace-the-future-of-p/image-1-1770151010345.jpg)