Amazon's Hidden Problem With Child Sexual Abuse Material in AI Training Data

Last year, something alarming happened in the corners of the artificial intelligence industry that most people never heard about. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children received over 1 million reports of AI-related child sexual abuse material in 2025. More than 90% of those reports came from one company: Amazon.

But here's the infuriating part. Amazon won't say where the material came from.

When pressed for details about the sources of this content, Amazon gave the equivalent of a corporate shrug. The company claimed it found the CSAM in external datasets used to train its AI models but refused to disclose which sources, which datasets, or how this content ended up there in the first place. They said the information was proprietary and couldn't be shared.

Fallon Mc Nulty, the executive director of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children's Cyber Tipline, called the situation an outlier. And that's putting it mildly. The reports Amazon submitted weren't just concerning—they were completely useless to law enforcement. Mc Nulty told Bloomberg that unlike reports from other tech companies, Amazon's submissions were what she called "inactionable." No context. No source information. No actionable intelligence that could help investigators track down the perpetrators or protect children.

This is a story about opacity, accountability, and whether the technology industry is serious about protecting children. It's also a story about what happens when companies move fast, break things, and don't look back at what they broke.

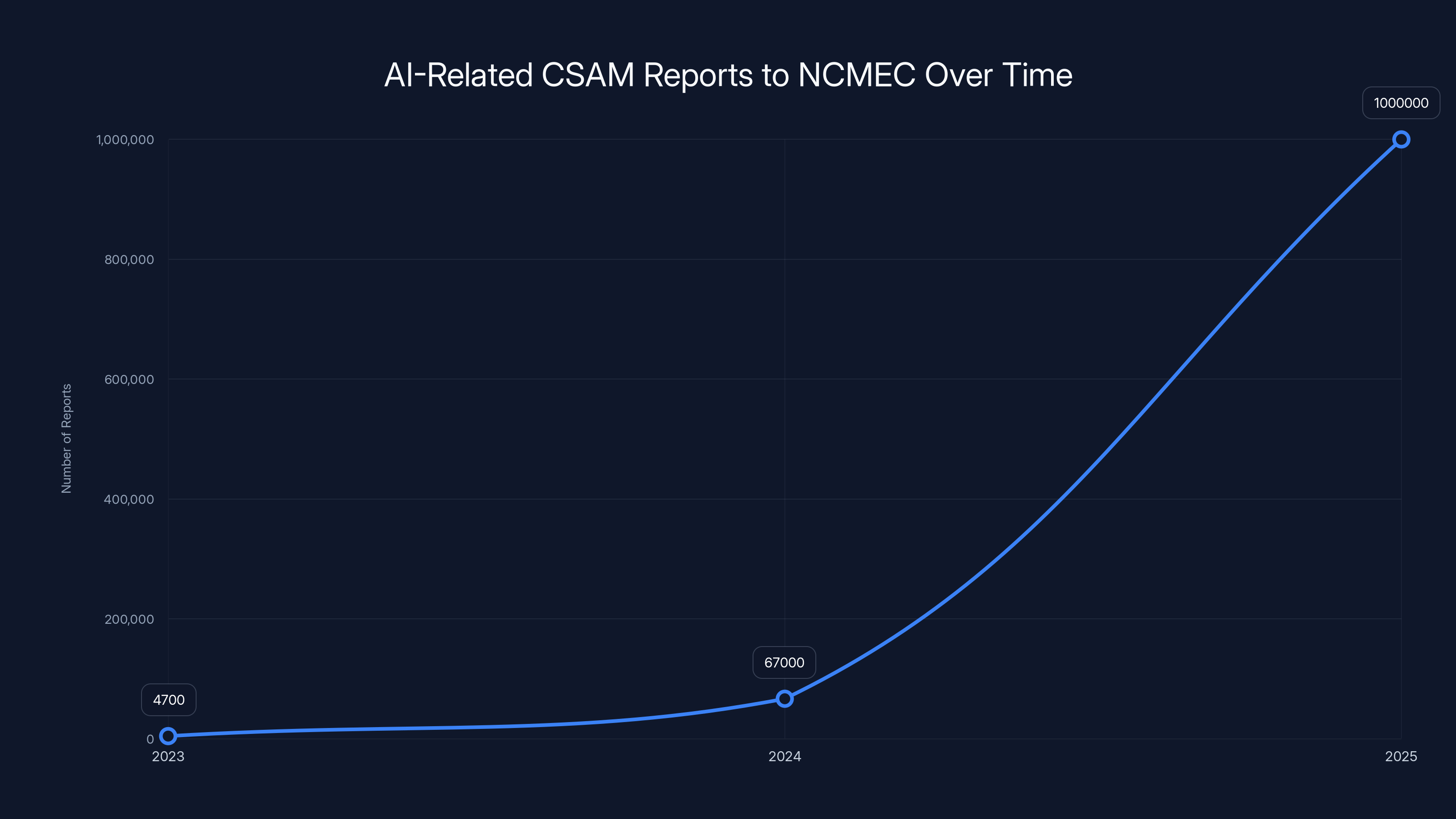

The numbers tell you everything. In 2023, the NCMEC received 4,700 AI-related CSAM reports. In 2024, that jumped to 67,000. Last year, it exploded to 1 million plus. That's not a gradual increase. That's an explosion. And it's accelerating.

TL; DR

- 1 million+ AI-related CSAM reports were submitted to NCMEC in 2025, with the vast majority from Amazon

- Amazon refuses to disclose sources, claiming datasets are proprietary and cannot be shared

- Reports are classified as "inactionable" by child safety experts, lacking context for law enforcement

- CSAM detections have skyrocketed from 4,700 reports in 2023 to over 1 million in 2025

- Other companies provide actionable data, making Amazon's opaque approach a major outlier in the industry

- No safeguards were implemented before training, raising questions about content filtering practices

- Removal happened post-detection, not during the data collection or curation phase

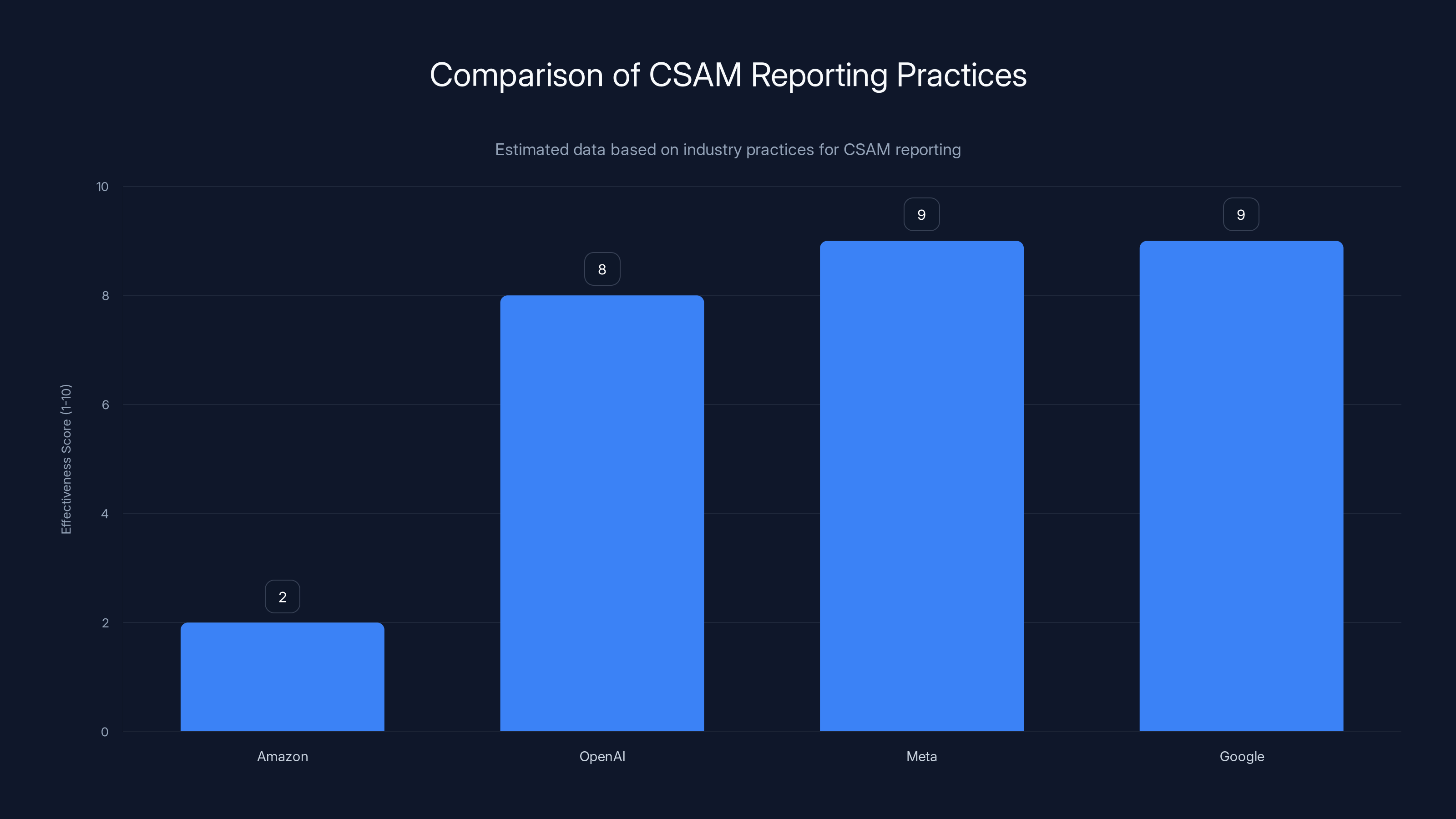

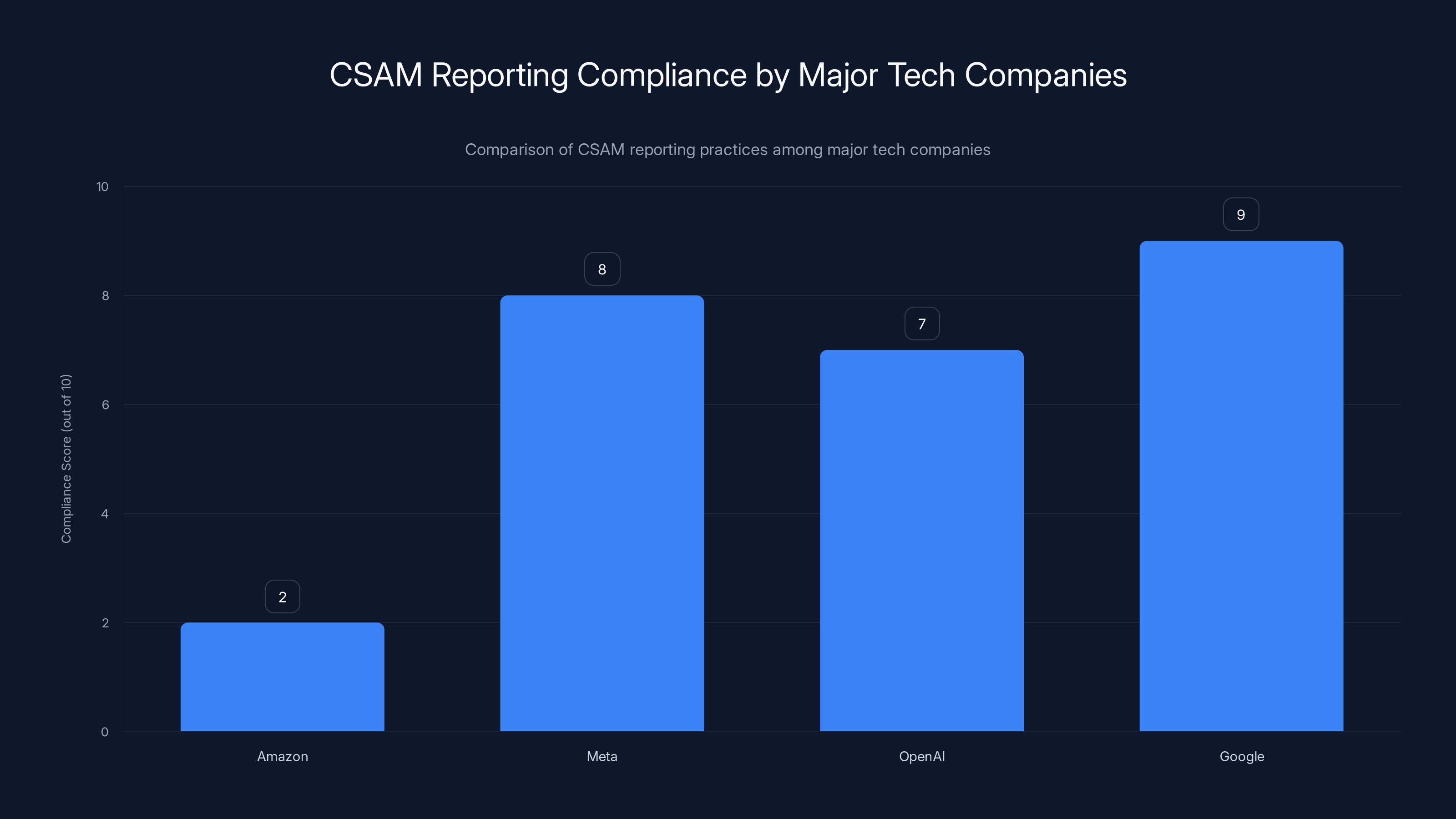

Amazon's CSAM reporting practices are estimated to be less effective compared to other tech giants like OpenAI, Meta, and Google, which provide more actionable reports to law enforcement. Estimated data.

How CSAM Ended Up in Amazon's AI Training Data

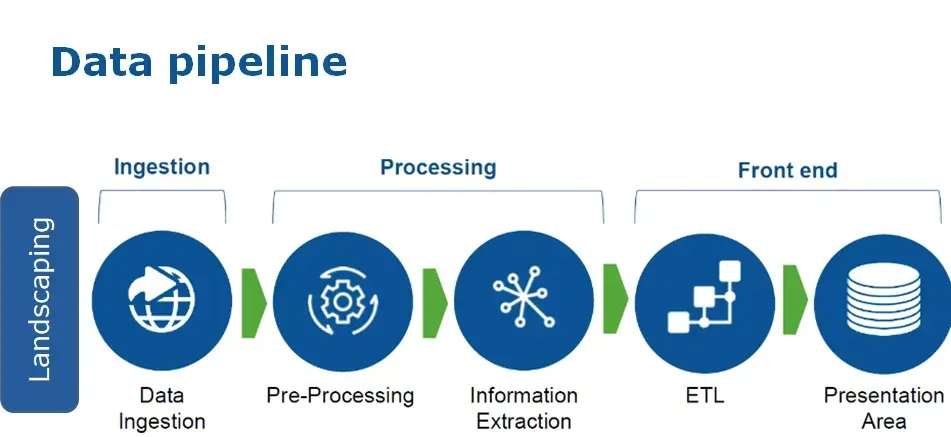

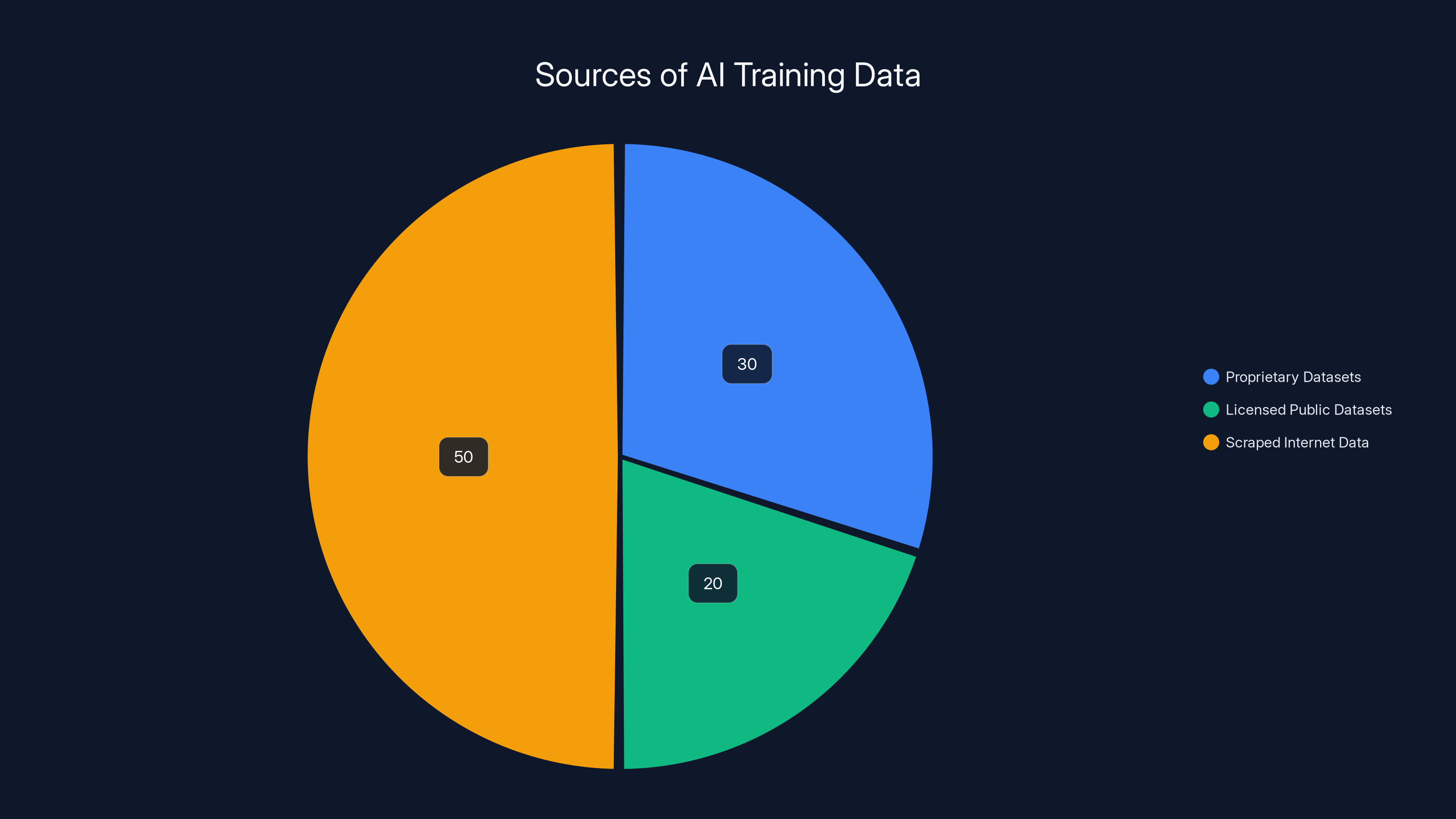

Understanding this crisis requires understanding how AI training data works. Large language models and multimodal AI systems need to be trained on billions of pieces of data. The bigger the dataset, the more capable the model. Companies have three main sources for this data: proprietary datasets they've built themselves, publicly available datasets they license, and data scraped directly from the public internet.

Amazon's approach involved using external sources. The company pulled data from multiple places to train its AI services. But here's the problem: when you're scraping the internet at massive scale, you don't have perfect visibility into what you're getting. Bad data slips through. Harmful data slips through. Illegal content slips through.

The internet contains an enormous amount of content that shouldn't exist. This includes material involving the exploitation of children. It's been there for years, spread across various platforms, forums, and datasets. When you're downloading billions of images, videos, and text snippets without robust filtering at the intake stage, you're going to capture some of that content.

But that's exactly the problem. There should have been filtering. There should have been safeguards. There should have been multiple checkpoints before any of that data got anywhere near a training pipeline.

Amazon said it takes a "deliberately cautious approach" to scanning training data and that it looks for known child sexual abuse material. The company claims it removed the suspected CSAM before it actually fed the data into its AI models. That sounds responsible on the surface. But removed after it was detected, not before it was included in the first place.

This is like finding a mouse in your restaurant kitchen and saying you threw it away, so everything is fine now. The problem wasn't just that the mouse existed. The problem is that your procedures allowed the mouse to get in during the first place.

The company also said it deliberately over-reported cases to the NCMEC to avoid missing any instances. This sounds like abundance of caution, but it actually raises another question: if you're over-reporting, are you also not investigating what you're reporting? Are you just flagging everything as potentially problematic without doing the filtering work yourself?

The answer matters because the NCMEC receives reports from Amazon, investigates them, and tries to pass actionable intelligence to law enforcement. If Amazon is just flagging stuff without providing context or source information, the NCMEC's investigators end up spinning their wheels trying to figure out where the material came from and how to act on it.

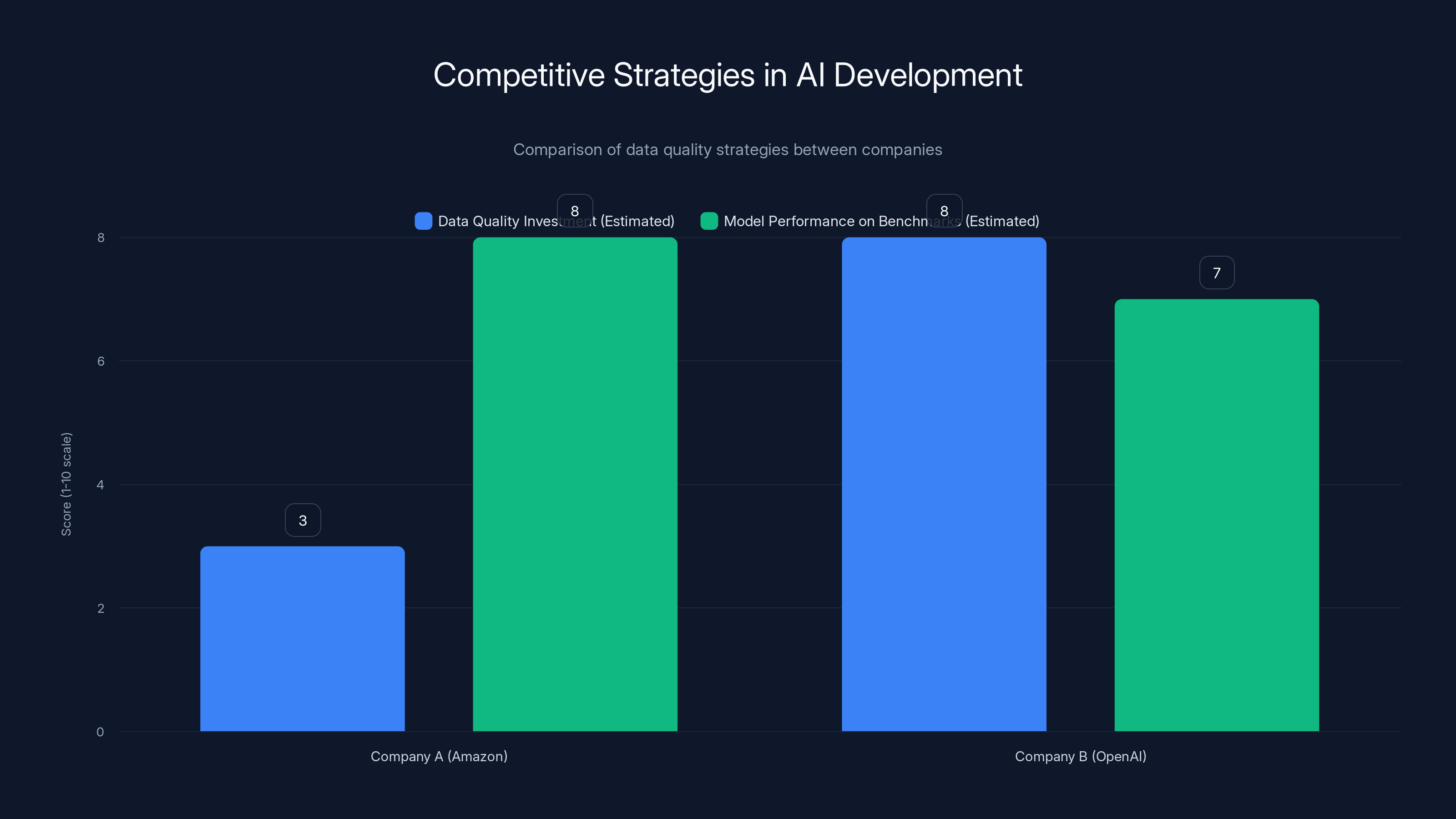

Estimated data shows that while Amazon may achieve higher benchmark scores by cutting corners, OpenAI's investment in data quality ensures long-term trust and reliability. Estimated data.

Why Amazon's Data Sources Matter

Let's talk about why disclosure of sources is so important. When a company reports potential CSAM to the NCMEC, investigators need to know where it came from. Is it from a specific platform? A specific user? A specific geographic region? This information helps investigators understand the scope of the problem, identify networks of perpetrators, and work with specific platforms to take down harmful content.

Without source information, investigators are essentially looking at isolated data points with no connective tissue. You can't build a case. You can't identify patterns. You can't shut down the pipeline that produced the harmful content in the first place.

Amazon claimed it couldn't share this information because the datasets are proprietary. But here's the thing: other companies manage to report CSAM while also providing useful context to law enforcement. It's entirely possible to say "we found this material in a dataset from Source X" without revealing your proprietary training pipeline or your trade secrets.

Meta reports CSAM. Open AI reports CSAM. Google reports CSAM. These companies figure out how to be compliant with the law and also useful to the child safety community. Amazon's position suggests either an unwillingness to do that work or a fundamental lack of visibility into their own data sources.

The lack of actionable data is particularly frustrating to the people who work in child safety. Fallon Mc Nulty told Bloomberg that having such a high volume of reports that are essentially useless forces the NCMEC to spend resources investigating Amazon's submissions when they could be using those resources elsewhere.

Consider the math. If you're getting 1 million reports from one company and 5,000 reports from all other companies combined, and the reports from other companies are actionable while Amazon's aren't, you're looking at a situation where the majority of your incoming data is not useful. That's a problem. That's a massive resource waste in an organization dedicated to protecting children.

What Amazon should be doing is saying: "We found CSAM in datasets from source A, B, and C. We've notified those sources directly. Here's where we found it. Here's what it was. Here's what we've done about it." Instead, Amazon said: "We found some stuff. It's handled. Stop asking questions."

The CSAM Explosion and What It Means

To understand why this is such a big deal, you need to look at the trajectory. CSAM reports to the NCMEC related to AI didn't start at zero. They started small and grew exponentially.

2023: 4,700 AI-related CSAM reports 2024: 67,000 AI-related CSAM reports (14x increase) 2025: 1,000,000+ AI-related CSAM reports (15x increase)

This isn't a gradual trend. This is an explosion. Something changed. And the change seems to correlate directly with the massive scaling of AI model training and the increasing use of internet-scraped data as training material.

Why is this happening? A few reasons. First, more companies are building AI models, and they're all vacuuming up training data from the internet. Second, data scraping is happening faster and with less human oversight than it used to. Third, companies aren't implementing sufficient filtering mechanisms to catch harmful content at the intake stage.

Fourth, and this is important, more companies are actually reporting when they find this material. That's a good thing. But it also means we're seeing the real scope of the problem for the first time. We're not discovering that CSAM suddenly started appearing in AI training data in 2023. We're discovering that it was always there, and now we're finally measuring it.

The concentration of reports from Amazon is particularly striking. When one company is responsible for 90%+ of the reports you're receiving, something is structurally different about that company's approach. Either their dataset acquisition practices are significantly riskier than other companies, or they're doing more detection work than other companies.

Amazon claims it's the latter. But then why aren't they providing actionable data? If you're doing more detection work, you should have more visibility into where the material came from. You should have better data to share.

The alternative explanation is that Amazon scraped data from sources known to contain harmful content, didn't filter effectively at intake, detected the problem too late, and now doesn't want to admit what they were scraping or why their safeguards failed.

The number of AI-related CSAM reports to NCMEC surged dramatically from 4,700 in 2023 to over 1 million in 2025, highlighting a critical issue in AI data sourcing.

How Other Companies Handle CSAM Reporting

When you compare Amazon's approach to how other tech companies handle CSAM reporting, the differences are stark. Most companies that report to the NCMEC provide context, source information, and actionable intelligence.

Open AI, for example, reports to the NCMEC when it finds problematic content. But Open AI is also transparent about its processes. The company uses a combination of automated content moderation and human review. When content is flagged, Open AI can explain where it came from, why it was problematic, and what steps the company took to address it.

Meta does similar work. The company has sophisticated content moderation systems and regularly reports findings to the NCMEC. Meta's reports are actionable because Meta knows its systems, knows where content came from, and can provide investigators with meaningful leads.

Google deals with massive amounts of data, but the company has invested heavily in content classification systems. When Google finds problematic material, it can typically trace it back to a source and provide that information to authorities.

Amazon, by contrast, is refusing to disclose sources. This is a choice. It's a business choice, likely driven by legal risk concerns or reluctance to highlight security vulnerabilities in their data acquisition processes.

The pattern is clear. Companies that have built robust, transparent systems can report effectively. Companies that are just reacting to problems and flagging content without understanding their own pipelines end up creating noise instead of signal.

Amazon could improve this situation relatively quickly. The company could commit to providing source information for all future CSAM reports. It could work with the NCMEC to develop processes that preserve proprietary details while providing operational context. It could be transparent about its data sources and the screening processes it uses.

Instead, the company chose opacity.

The Bigger Picture: AI Training Data Quality

This CSAM crisis isn't happening in isolation. It's part of a larger conversation about AI training data quality and the shortcuts companies are taking to scale their models quickly.

There's enormous competitive pressure in AI right now. Companies want bigger models. Bigger models need more data. More data means going to the internet and scraping everything. But when you scrape everything, you get everything. The good, the bad, the ugly, and the illegal.

Some companies have realized that data quality matters more than data quantity. They've invested in curation, filtering, and careful source selection. These approaches take longer and cost more money. But they produce better models and avoid legal and ethical disasters.

Other companies have decided to move fast and deal with consequences later. Scrape first, filter later. Detect problems after the model is trained. Report problems to regulators. Hope that transparency is enough.

The CSAM issue is the consequence of the second approach taken to an extreme. Amazon's sheer volume of reported problematic content suggests the company either scraped from the wrong sources or didn't implement sufficient filtering mechanisms.

Here's what we don't know but should: Did Amazon know it was scraping sources that contained CSAM? Was it a deliberate risk calculation? Did Amazon's teams flag the risks and were they ignored? Or did nobody in the organization take data quality seriously enough to ask these questions?

These are questions that regulators should be asking. They're not the kind of questions that Amazon's current "we removed it afterward" approach addresses.

The broader issue is that the AI industry doesn't have sufficient accountability mechanisms. Companies can scrape data from anywhere, build models quickly, and then deal with the consequences as a business problem rather than an operational one. As long as they report the problem to the right agency, they figure they're compliant.

But compliance isn't the same as responsibility. Reporting that you found 1 million instances of CSAM is very different from building systems that prevent the CSAM from being included in the first place.

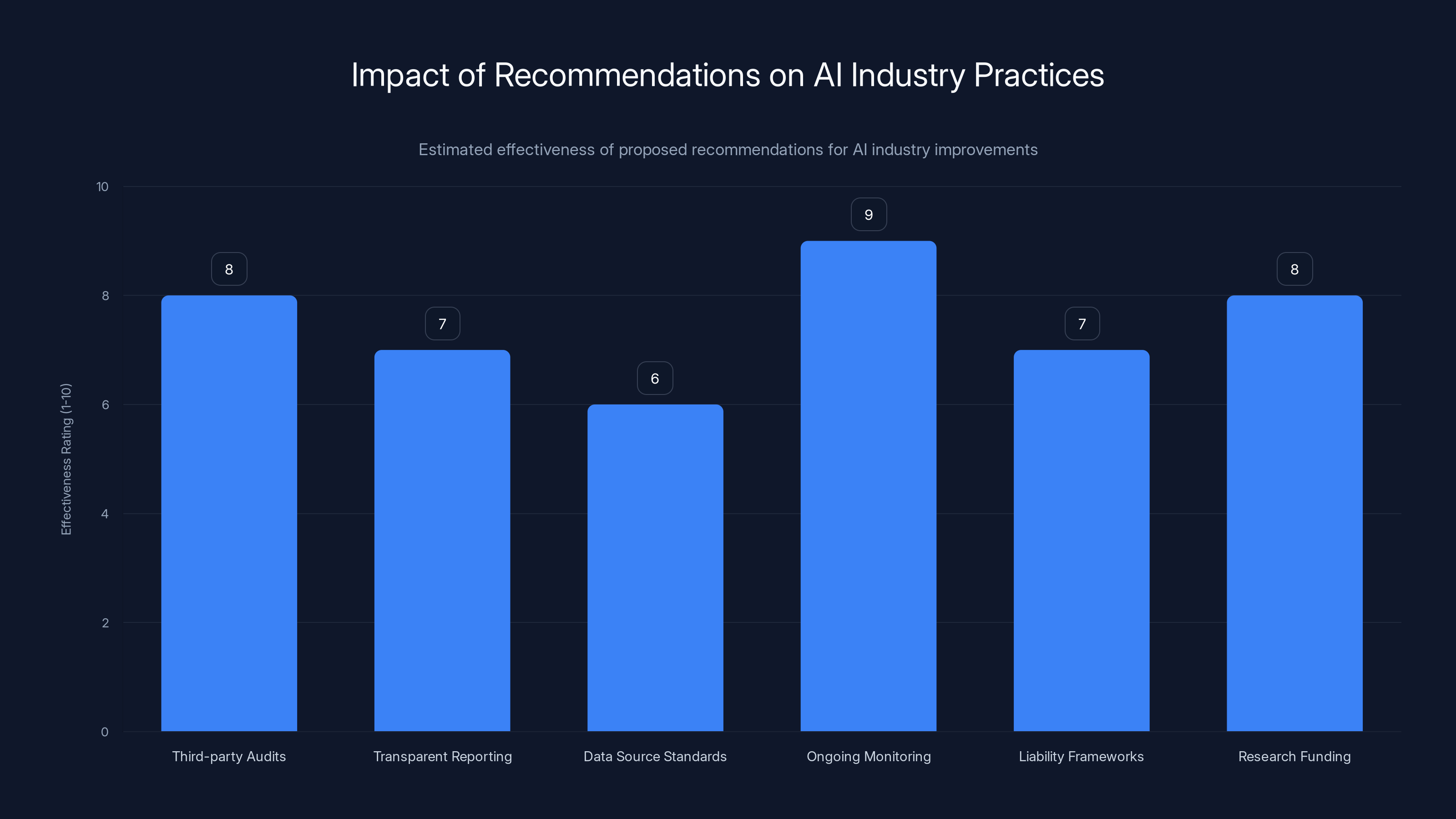

Implementing third-party audits and ongoing monitoring are estimated to be the most effective recommendations for improving AI industry practices. Estimated data.

Legal and Regulatory Implications

The CSAM issue creates serious legal exposure for Amazon. The company could face investigations by the Federal Trade Commission, attorneys general in various states, and potentially federal prosecutors. The Defend Children Act and other legislation give regulators and law enforcement tools to pursue companies that fail to adequately protect children online.

Amazon's opacity about data sources is particularly problematic from a legal standpoint. If the company can't explain where the data came from or why safeguards failed, prosecutors and regulators might conclude that the company was negligent or indifferent to the risks.

The company might face civil litigation from advocacy groups or from parents of harmed children. Amazon could also face pressure from its customers and business partners to explain what happened and how the company will prevent similar incidents.

Moreover, there's the question of whether Amazon's lack of actionable reporting violates its obligations under the Cyber Tipline system. When a company submits reports that are so vague that they can't be acted upon, is the company truly complying with the spirit of the law?

For other companies in the AI space, the Amazon situation is a cautionary tale. The cost of not building robust data quality processes upfront is far higher than the cost of building them. Companies like Open AI and Meta are investing heavily in content moderation and data filtering specifically to avoid this situation.

Regulators are clearly paying attention. The FTC has launched initiatives focused on AI safety. Congress has held hearings on AI and child safety. State attorneys general are investigating tech companies' practices. The message is clear: companies that don't take data quality and child safety seriously will face regulatory consequences.

AI Safety and the Failure to Implement Guardrails

One of the most concerning aspects of this situation is what it reveals about AI safety practices in the industry. If a company like Amazon, with resources to spare, didn't implement sufficient content filtering at the data intake stage, what are smaller companies doing?

Amazon's safety practices apparently relied on post-training detection rather than pre-training prevention. The company scanned data after it was collected but before it was used for training. That's better than no safeguards, but it's fundamentally reactive rather than proactive.

Better practice would involve multiple layers. First, careful source selection. Which datasets are known to be clean? Which sources have good content moderation? Second, automated filtering at intake. Scanning incoming data for known harmful content patterns. Third, human review of flagged content. Fourth, final screening before training. Fifth, ongoing monitoring of model outputs.

Amazon apparently had some detection mechanisms, but the fact that it found 1 million instances suggests those mechanisms weren't deployed at scale or weren't tuned effectively.

The broader question is whether the AI industry is serious about safety or just going through the motions. Companies want to build AI systems quickly and deploy them to market. Safety adds friction. Data quality processes add friction. Content moderation adds friction.

But the CSAM crisis shows what happens when you optimize for speed over safety. You end up with contaminated models, regulatory attention, legal liability, and reputational damage. In the long run, safety isn't friction. It's the responsible path.

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of AI training data comes from internet scraping, highlighting the risk of including harmful content.

The Role of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

The NCMEC is operating at the front lines of the CSAM issue. The organization receives reports from tech companies, investigates them, and passes actionable intelligence to law enforcement. It's a critical function in the digital safety ecosystem.

But the organization is also resource-constrained. When it receives 1 million reports from one company and most of them are unusable, it's a massive drag on the organization's capacity. The NCMEC has to investigate Amazon's reports, determine that they lack actionable data, and then move on to reports from other sources that are actually useful.

Fallon Mc Nulty, the executive director of the NCMEC's Cyber Tipline, was explicit about this. She called Amazon's reports "inactionable." That's a specific word choice. Not "unhelpful." Not "vague." "Inactionable." Meaning the organization literally cannot take action based on these reports.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Companies that report thoroughly but provide context are helping law enforcement. Companies that report vaguely are creating busywork for the NCMEC. If Amazon's goal is to comply with reporting requirements while minimizing cooperation with law enforcement, the company has achieved that goal.

But this isn't a sustainable approach. Regulators and policymakers will eventually push back on companies that report large volumes of inactionable data. The Cyber Tipline system is designed to be a bridge between tech companies and law enforcement. When companies don't use it effectively, the system breaks down.

The NCMEC is also documenting all of this. The organization is aware that most of the AI-related CSAM reports come from Amazon and that Amazon's reports lack context. This information will inevitably make its way to regulators and could become evidence in investigations or enforcement actions.

What Should Amazon Have Done Differently

Let's be clear about what responsible practice looks like. A company that discovers CSAM in training data should:

1. Implement source vetting at intake. Know which datasets and sources are reputable. Avoid pulling data from sources known to have insufficient content moderation.

2. Deploy automated content filtering. Use existing CSAM detection systems to identify problematic content as it's ingested. Multiple filtering passes are better than one.

3. Maintain visibility into data sources. Keep records of where data comes from, what filtering was applied, and what problems were detected. This information is crucial for accountability.

4. Report with context and actionable information. When reporting to the NCMEC, provide source information, detection methodology, and context that law enforcement can act on.

5. Be transparent about what happened. Explain publicly what was found, how it was found, what failed in your safeguards, and how the company is preventing it in the future.

6. Work with the NCMEC and other organizations. Don't treat child safety reporting as a compliance checkbox. Treat it as a serious responsibility and work with experts to improve your processes.

Amazon hasn't done most of these things. The company found problematic content and reported it, which is better than nothing. But the company didn't implement sufficient safeguards, didn't maintain visibility into sources, didn't provide actionable data, and hasn't been transparent about what happened.

Amazon has the resources to do better. The company could commit to significant improvements in its data quality practices. It could work with independent auditors to verify that safeguards are working. It could be transparent about its processes.

Instead, the company chose opacity and claims that source information is proprietary and can't be shared. That's a choice. And it's the wrong one.

Amazon scores lower in CSAM reporting compliance compared to Meta, OpenAI, and Google, indicating potential gaps in data source transparency. Estimated data based on narrative context.

The Competitive Pressure Problem

One reason Amazon may have cut corners on data quality is competitive pressure. In the AI race, companies are obsessed with model scale and capability. Bigger models. More parameters. Better performance on benchmarks. To achieve this, you need more training data.

But more data only matters if the data is good. If you're training on contaminated data, you're making your model worse, not better. You're introducing biases. You're potentially training your model to reproduce harmful content.

There's a race-to-the-bottom dynamic here. If Company A is scraping everything and Company B is carefully vetting sources, Company A will have larger datasets. Company A's models will achieve higher benchmark scores on raw capability metrics. This creates pressure on Company B to also cut corners.

But the companies that will win long-term are the ones that get this right. Open AI has built a successful business by investing in data quality and safety. The company's models are trusted by millions of users and enterprises because Open AI has demonstrated that it takes responsibility seriously.

Amazon is in the opposite position. Amazon's approach suggests that the company is willing to cut corners to keep up with competitors. That's a short-term decision that creates long-term problems.

The solution to this problem is for regulators to make it clear that cutting corners on data quality isn't acceptable. The cost of compliance should be lower than the cost of regulatory fines, reputational damage, and legal liability. When companies face real consequences for poor data practices, they'll invest in doing better.

What This Means for AI Model Users

If you're using Amazon's AI services, this situation should concern you. The company has demonstrated that its training data quality processes are insufficient. While Amazon claims it removed the problematic content before training the models, the sheer volume of detected CSAM suggests that a lot of bad data made it further into the pipeline than it should have.

This raises questions about what other types of harmful content might be present in Amazon's training data. If the company didn't catch 1 million instances of CSAM, what else is in there? Hate speech? Harassment? Propaganda? Misinformation?

When you're using an AI system to make business decisions, you want to be confident that the underlying model is trained on high-quality, curated data. You want to be confident that the company building the model took safety and quality seriously.

Amazon's approach doesn't inspire confidence. It suggests that the company prioritized speed over quality and is now dealing with the consequences.

Customers and partners should ask Amazon hard questions about data quality. What's your process? Who's auditing you? What other problems have you detected? How are you improving? If Amazon can't answer these questions satisfactorily, that's a reason to consider alternatives.

Recommendations for the Tech Industry

The CSAM crisis points to some clear recommendations for how the AI industry should be operating:

1. Mandate third-party audits of training data. Companies should be required to have independent auditors verify that their data quality and content moderation processes meet minimum standards.

2. Require transparent reporting of safety incidents. When companies detect problematic content, they should be required to report not just the volume but also the context and sources. Lack of transparency should trigger regulatory review.

3. Set standards for data source vetting. The industry should establish best practices for which sources are acceptable and what filtering is required.

4. Require ongoing monitoring of model outputs. After deployment, companies should monitor what their models are producing and report safety issues to relevant authorities.

5. Create liability frameworks. Companies that deploy models trained on contaminated data should face liability if those models produce harmful outputs.

6. Fund research into data quality. The AI industry should invest in research on how to detect and prevent harmful content in training data.

These recommendations would increase the cost of doing business in AI, but they'd also ensure that companies are doing the right thing. Right now, the incentives are misaligned. Companies can cut corners and face few consequences until they're caught. Fixing the incentives means fixing the industry.

Looking Forward: What Happens Next

The Amazon CSAM situation will have consequences. Some will be regulatory, some will be legal, and some will be reputational. The company has already faced criticism from child safety advocates, and that criticism will intensify as more people learn about the situation.

Regulators are paying attention. The FTC has a history of action against tech companies that fail to protect children. Congress has been holding hearings on AI safety. State attorneys general are investigating various tech companies. The political environment is increasingly hostile to companies that are perceived as not taking safety seriously.

We'll likely see formal investigations into Amazon's practices. The company may face fines or requirements to change its practices. Amazon might be required to implement new content moderation processes or submit to ongoing third-party auditing.

We might also see legislative action. Congress could pass laws requiring companies to implement specific safety practices or to maintain transparency about data sources. States could pass their own regulations.

For the AI industry broadly, this situation is a wake-up call. Companies need to take data quality and safety seriously. Not because it looks good. Not because regulators will punish them if they don't. But because it's the right thing to do.

Amazon could still get ahead of this by being transparent, implementing robust safeguards, and working cooperatively with regulators and child safety organizations. The company could turn a negative situation into a positive one by demonstrating leadership in data quality and safety.

Instead, the company appears to be taking a defensive posture. That approach rarely ends well.

The Fundamental Question: Is the AI Industry Ready?

This whole situation raises a fundamental question: Is the AI industry ready for the responsibility it's taking on? AI systems are being deployed in increasingly important domains. They're being used to make decisions about hiring, lending, criminal justice, and more. These systems will inevitably affect vulnerable populations, including children.

If companies can't even ensure that their training data doesn't contain illegal content depicting child exploitation, how can we trust them to handle the more subtle ethical questions that AI raises?

The CSAM issue is a obvious case. It's not a gray area. It's not a matter of opinion. If your training data contains illegal content, that's a problem. Full stop. No company should have to be convinced of this. But here we are.

Amazon's approach, if widely adopted, would suggest that the industry isn't ready. If companies can cut corners on data quality and face minimal consequences, the industry will continue to cut corners.

But if this situation creates enough regulatory pressure and reputational incentive for companies to do better, we might see a shift. We might see real investment in data quality. We might see transparency about safety practices. We might see the industry actually growing up.

The next year or two will be critical. Watch how regulators respond. Watch how other companies react. Watch whether Amazon changes its practices. These things will tell you whether the AI industry is serious about responsibility or just paying lip service to it.

Conclusion: The Cost of Cutting Corners

The Amazon CSAM situation is a reminder that artificial intelligence isn't magic. It's built on data. And that data has to come from somewhere. If companies aren't careful about where the data comes from and how it's processed, they end up building systems on a foundation of contaminated material.

Amazon discovered 1 million instances of child sexual abuse material in its training data. The company reported it to authorities, which is good. But the company refused to provide context or source information, which is not good. The NCMEC described the reports as inactionable, which means Amazon's approach isn't actually helping law enforcement.

This is the cost of cutting corners. This is what happens when a company prioritizes speed and scale over responsibility. This is what the AI industry needs to learn from.

The path forward requires companies to take data quality seriously. It requires transparency. It requires working cooperatively with child safety organizations. It requires admitting when things go wrong and committing to real improvements.

Amazon can still do this. The company can change its practices. The company can invest in better safeguards. The company can be transparent about what happened.

But until the company does these things, the CSAM situation will remain a symbol of what's wrong with how the AI industry approaches responsibility. And that's a stain that won't wash away quickly.

The children depicted in the material that ended up in Amazon's training data are real victims. The fact that this material was ingested, processed, and stored in a commercial AI system is a real problem. The fact that Amazon refuses to provide meaningful information about what happened is a real failure.

This situation should matter to everyone who cares about child safety, about corporate responsibility, and about whether artificial intelligence can be trusted as a transformative technology. Right now, the answer is far from certain.

FAQ

What exactly is CSAM in AI training data?

CSAM (Child Sexual Abuse Material) refers to images and videos depicting the exploitation of minors. When this material ends up in AI training datasets, it means the datasets contain illegal content that shouldn't exist anywhere, let alone in commercial systems. The presence of CSAM in training data is problematic because it exposes the systems to illegal content and raises questions about source vetting and content moderation processes.

Why does Amazon refuse to disclose the sources of problematic data?

Amazon claims that disclosing sources would reveal proprietary information about its data acquisition practices and training datasets. The company argues that revealing these details could compromise competitive advantage or expose vulnerabilities in its systems. However, child safety advocates argue that companies can protect proprietary information while still providing sufficient context for law enforcement to be effective.

What does "inactionable" mean in the context of NCMEC reports?

When the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children calls reports "inactionable," it means the reports lack sufficient context and source information for law enforcement to investigate effectively. Actionable reports provide details about where content came from, how to access it, and information that helps investigators trace the source and take meaningful action. Without this information, reports are essentially useless to law enforcement.

How does this compare to how other tech companies handle CSAM?

Companies like Open AI, Meta, and Google report CSAM findings to the NCMEC with context and source information that allows law enforcement to investigate. These companies have invested in content moderation systems that allow them to understand where problematic content came from and how it made it into their systems. Amazon's refusal to provide this level of detail is an outlier in the industry.

What are the legal consequences Amazon might face?

Amazon could face investigations by the Federal Trade Commission, state attorneys general, and federal prosecutors. The company could face fines for failing to adequately protect children or for not cooperating fully with child safety organizations. Amazon could also face civil litigation from advocacy groups and potentially criminal charges depending on whether executives knew about the risks and failed to address them.

What safeguards should companies implement to prevent CSAM in training data?

Best practices include vetting data sources carefully before ingestion, implementing automated content filtering to detect problematic material, conducting human review of flagged content, maintaining detailed records of where data comes from, and providing context to law enforcement when problems are discovered. Companies should also conduct ongoing monitoring of deployed models to ensure they're not reproducing harmful content.

Why did this problem happen in the first place?

The combination of rapid AI model scaling, reliance on internet-scraped training data, and insufficient content moderation processes at the intake stage created the conditions for CSAM to end up in training datasets. Companies prioritized getting more training data faster without investing sufficiently in quality assurance and safety filtering.

How many AI-related CSAM reports are we talking about across all companies?

In 2025, the NCMEC received over 1 million AI-related CSAM reports, with more than 90% coming from Amazon. This represents an explosion from 4,700 reports in 2023 and 67,000 reports in 2024, indicating a major increase in detection and reporting as companies scale their AI systems.

What can users of Amazon's AI services do in response?

Users should ask Amazon detailed questions about data quality processes, content moderation practices, and safety testing. Users should request transparency about how the company sources training data and what safeguards are in place. If Amazon can't answer these questions satisfactorily, users should consider alternatives from competitors with stronger data quality reputations.

What needs to happen for the AI industry to prevent similar situations?

The industry needs mandatory third-party audits of training data, transparent reporting of safety incidents, standards for data source vetting, ongoing monitoring of model outputs, and clear liability frameworks for companies that deploy models trained on contaminated data. Regulatory action and legislative requirements will likely be necessary to drive these changes.

Related Reading and Resources

For more information on AI safety, data quality, and child protection in the technology industry, consider exploring topics like responsible AI development practices, content moderation at scale, data governance frameworks, and regulatory approaches to technology safety. These areas intersect with the Amazon CSAM situation and provide important context for understanding how the AI industry should evolve.

Key Takeaways

- Amazon discovered 1 million+ instances of CSAM in AI training data but refuses to disclose where it came from, claiming the information is proprietary

- The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children classified Amazon's reports as 'inactionable' because they lack source information needed by law enforcement

- CSAM reports to NCMEC have skyrocketed from 4,700 in 2023 to over 1 million in 2025, with 90%+ coming from Amazon due to flawed data acquisition practices

- Other tech companies like OpenAI and Meta successfully provide actionable CSAM reports with context, proving Amazon's opacity isn't technically necessary

- The crisis reveals systemic failures in AI training data quality and the race-to-the-bottom incentives driving companies to prioritize speed over responsibility

Related Articles

- AI Chatbots & User Disempowerment: How Often Do They Cause Real Harm? [2025]

- Why Publishers Are Blocking the Internet Archive From AI Scrapers [2025]

- Energy-Based Models: The Next Frontier in AI Beyond LLMs [2025]

- AI-Generated Anti-ICE Videos and Digital Resistance [2025]

- Google's Project Genie AI World Generator: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Nvidia's AI Chip Strategy in China: How Policy Shifted [2025]

![Amazon's CSAM Crisis: What the AI Industry Isn't Telling You [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/amazon-s-csam-crisis-what-the-ai-industry-isn-t-telling-you-/image-1-1769728009339.jpg)