Nuclear Startups and Small Modular Reactors: Can Manufacturing Really Fix the Problem? [2025]

The nuclear industry is having a moment. After decades of decline—cost overruns, construction delays, public skepticism—suddenly everyone wants in again. Investors are pouring money at an alarming rate. Government support is broadening beyond traditional utility companies. Even tech billionaires are taking sides in the energy debate.

But there's a problem hiding underneath all this optimism, and it's not what you might think.

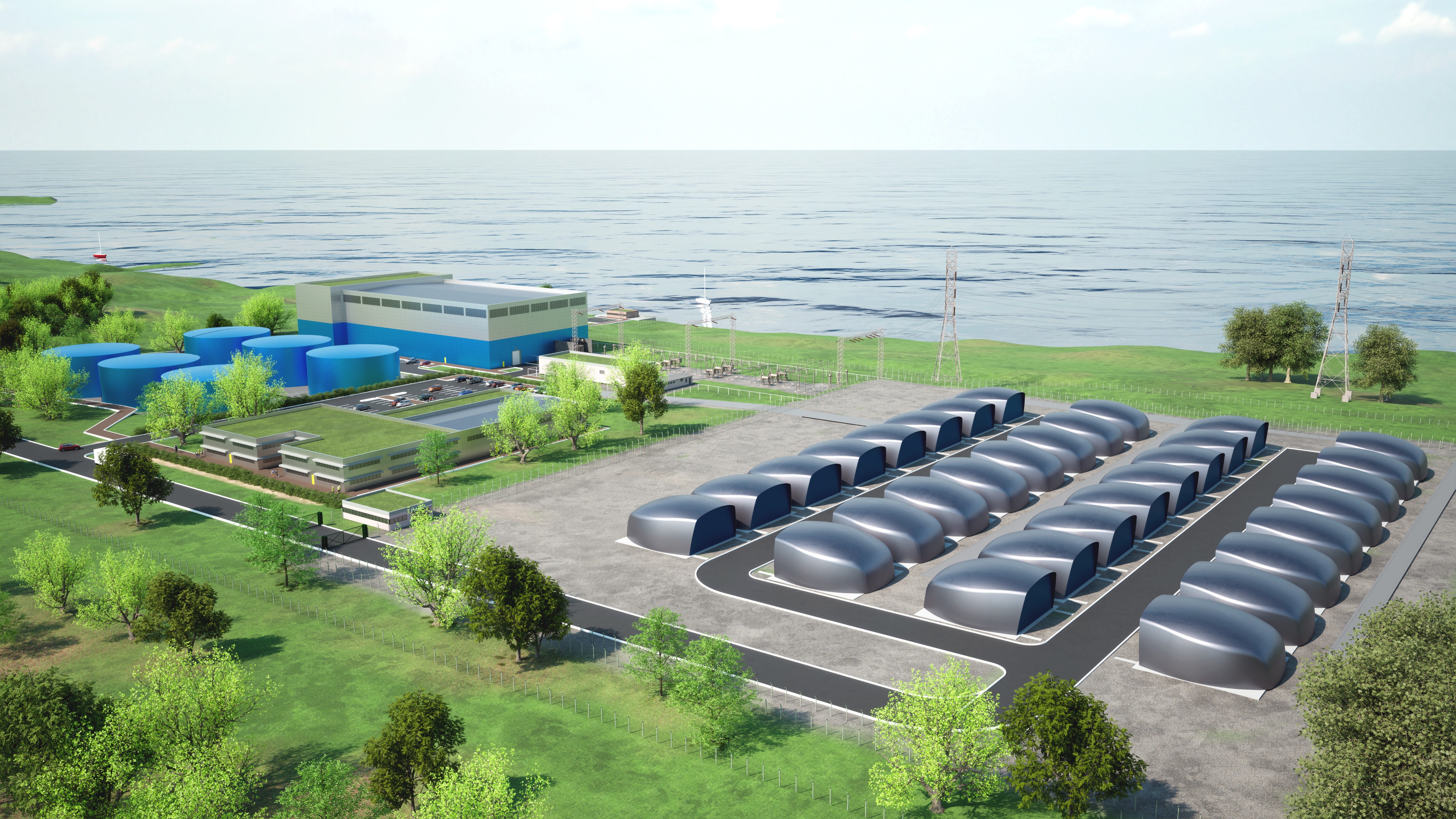

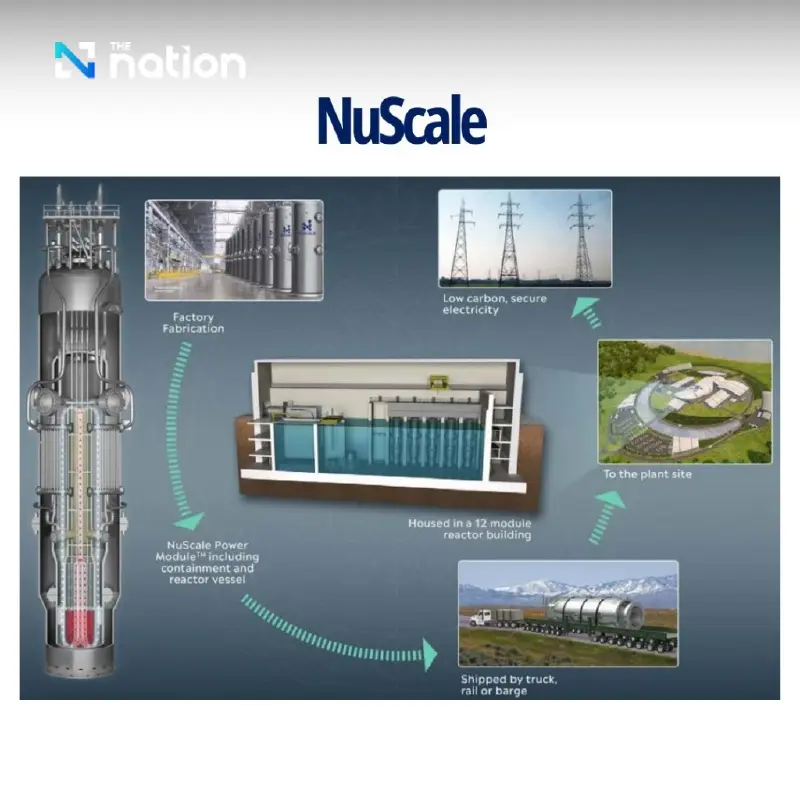

When you hear "small modular reactors" or SMRs, the pitch is seductive. Unlike massive nuclear plants that take 15 years and $30 billion to build, these smaller units could theoretically be manufactured in factories, shipped like industrial equipment, and deployed in modules. Stack them if you need more power. Replace one without shutting down the whole facility. Better economics through mass production.

It sounds like a perfect Silicon Valley playbook. Find an inefficient legacy industry. Apply modern manufacturing. Scale ruthlessly. Disrupt.

Except nuclear isn't software. It's not even hardware in the way most people understand it. It's the most regulated industry on Earth, built on 70 years of accumulated expertise, institutional knowledge, and supply chains that barely exist anymore.

Let's dig into what's really happening, what the risks actually are, and whether the nuclear startup moment is real transformation or collective wishful thinking.

The Nuclear Industry Is Having an Actual Renaissance (But Here's Why)

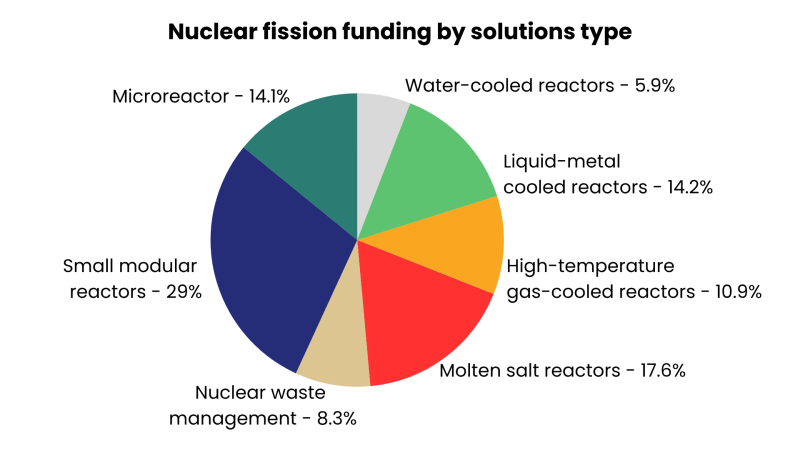

The numbers tell part of the story. In just the last weeks of 2025 alone, nuclear startups pulled in $1.1 billion in funding. That's not a typo. Over a billion dollars in a few weeks. Extrapolate that, and you're looking at an industry that's becoming a serious destination for venture capital.

This isn't just hype. There are real factors driving the investment surge.

First, climate change has finally broken through the noise. Governments are desperate for carbon-free power that actually runs 24/7. Solar and wind are great, but they don't run at 2 AM on a cloudy night. Nuclear does. It runs at 90%+ capacity factors, meaning it's generating electricity almost all the time.

Second, AI and data centers are creating unprecedented electricity demand. Companies building large language models, training neural networks, and deploying inference at scale need power that's both cheap and abundant. A lot of that demand is currently being met by natural gas plants—not exactly a climate victory. But a nuclear plant could power a data center for decades with minimal fuel costs.

Third, and this matters more than people realize, the regulatory environment is thawing. The Biden administration explicitly green-lit nuclear as a climate solution. This isn't just rhetoric—it translated into actual policy changes, expedited licensing pathways for advanced reactors, and billions in direct support through programs like the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP).

Add to that the geopolitical angle. Supply chains for critical minerals are increasingly concentrated in hostile or unstable countries. Energy independence has become a national security issue, not just an economic one. Nuclear looks different when you're thinking about strategic resilience.

But here's the thing that keeps getting glossed over: the industry is also having this renaissance because traditional nuclear got so broken that people are willing to try something completely different. The Vogtle units in Georgia are the cautionary tale everyone knows. Reactors 3 and 4, the newest nuclear plants built in the United States, were supposed to cost about

That's not just a project failure. That's an industry failure. When massive, experienced utilities can't build a nuclear plant without spectacular cost and time overruns, the message is clear: something is fundamentally broken.

Enter the startup thesis: what if the problem isn't nuclear physics, but construction methodology?

The Small Modular Reactor Thesis: Smaller Must Mean Better

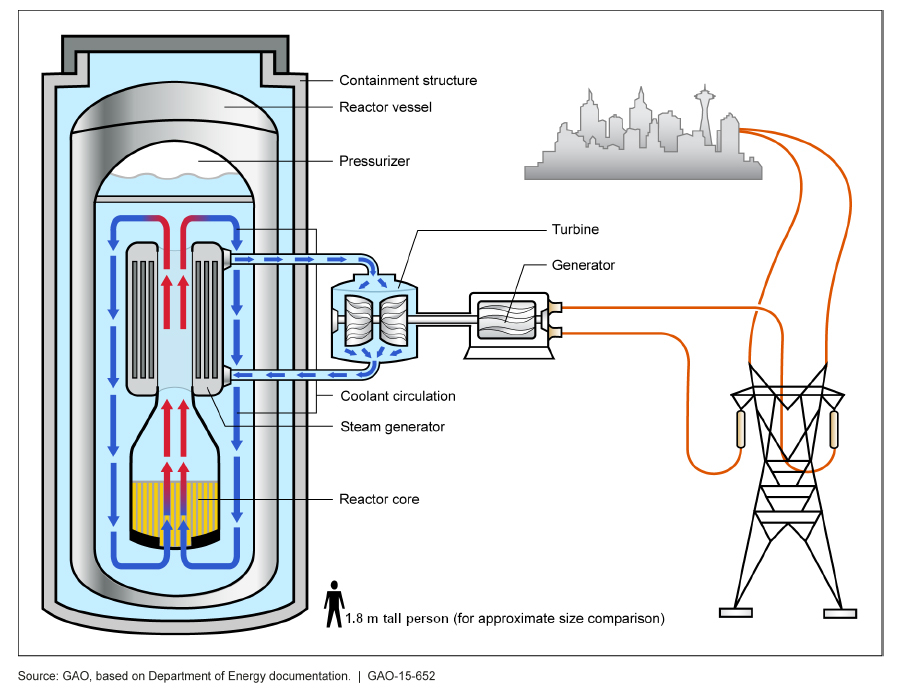

The pitch from companies like Nu Scale, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, X-energy, and dozens of others is straightforward. Traditional nuclear reactors are enormous, monolithic pieces of infrastructure. Vogtle's reactors generate 1.2 gigawatts each. The containment building is a cathedral-scale structure. Fuel assemblies are 14 feet tall. The sheer scale of these things creates scale problems: supply chains are thin, construction expertise is precious, quality control is harder, and fixing mistakes is expensive because everything is custom.

Small modular reactors flip the equation. Instead of one gigantic reactor, you might have twelve 100-megawatt modules. Each one is smaller, simpler, faster to build. Instead of custom construction, you're doing mass manufacturing. Instead of requiring specialists for every tiny component, you're building in volume so that manufacturing curves kick in.

It's not a new idea, but it's an idea that's suddenly fundable because the traditional nuclear model has become so obviously broken.

The economic logic is compelling. In manufacturing, the more you make, the cheaper each unit becomes. This is called the learning curve or manufacturing curve. For every doubling of cumulative production, costs typically drop 10-20% depending on the industry. It's why the first car cost millions and now you can get a functional vehicle for $15,000.

The startup argument is that SMRs are at the very beginning of that curve. The first few units will be expensive. But as companies manufacture the 50th, the 100th, the 500th module, costs will plummet. They'll eventually become so cheap that they'll be economically competitive without subsidies.

It's a seductive thesis. And it might even be right.

But there's a massive gap between right-in-theory and achievable-in-practice. That gap is called manufacturing reality.

The Tesla Problem: Why Manufacturing at Scale Is Harder Than Physics

Let's talk about Tesla for a moment, because Tesla is probably the closest comparison anyone can make to what nuclear startups are attempting.

Tesla also promised that scale and modern manufacturing could solve a legacy industry's problems. Elon Musk was confident that the Model 3 could be mass-produced profitably. The company famously had to shut down production multiple times because of manufacturing bottlenecks. Quality control issues plagued the company for years. The supply chain was fragile. Costs were higher than planned because suppliers couldn't deliver at the price points Tesla needed.

And Tesla had massive advantages that nuclear startups don't have. The automotive industry still exists in the United States. There are supply chains, suppliers, manufacturers, and a deep bench of engineering talent who understand how to build things. Companies like Toyota and BMW have been doing this for 100 years. Tesla could hire people who knew how to manufacture at scale.

There's also less regulation in automotive than nuclear. A Tesla manufacturing defect might result in recalls and lawsuits. A nuclear manufacturing defect could potentially end in catastrophic failure and evacuation. The stakes are different. The tolerance for learning curves is different. The regulatory patience is different.

Now imagine trying to do what Tesla did, but in an industry where the U.S. hasn't built anything significant in 40 years. Where supply chains have been completely offshored or dismantled. Where the regulatory bar is orders of magnitude higher. Where the cost of a mistake is potentially measured in lives, not in warranty claims.

This is what nuclear startups are actually attempting.

The Missing Ingredient: Manufacturing Expertise Doesn't Exist in the U.S.

Milo Werner is a partner at DCVC, a prominent climate tech venture capital firm. Before that, she worked at Tesla leading new product introduction for the Model 3. Before that, she did manufacturing operations at Fit Bit, launching four factories in China. She knows manufacturing. She knows how hard it is.

When she looks at nuclear startups, here's what she sees: capital is not the constraint. These companies are "awash in capital," as she puts it. They can raise money. They can hire executives. They can rent buildings and buy equipment.

The constraint is human capital. Specifically, experienced manufacturing people.

"We haven't really built any industrial facilities in 40 years in the United States," Werner said. "As a result, we've lost the muscle memory."

This isn't hyperbole. It's what happened when American manufacturing became concentrated in automotive and consumer electronics. When nuclear stopped being built. When the government stopped commissioning new industrial infrastructure. The country lost the institutional knowledge.

You need people who've done this before. Seasoned factory supervisors who know how to manage complex assembly lines. Operations managers who understand how to maintain equipment and solve problems in real time. Quality assurance specialists who know what to look for. Supply chain experts who know how to build resilient networks. Finance people who understand manufacturing economics.

Werner knows how many people have this expertise: not enough.

"I have a number of friends who work in supply chain for nuclear, and they can rattle off five to ten materials we just don't make in the United States," she said. "We have to buy them overseas. We've forgotten how to make them."

This is the supply chain problem in microcosm. The U.S. doesn't manufacture key materials that nuclear reactors need. You can build a factory in Texas and design an efficient production process, but if you can't source critical components domestically, you're dependent on foreign suppliers, longer lead times, and geopolitical risk.

Werner uses a vivid metaphor: "It's like we've been sitting on the couch watching TV for 10 years and then getting up and trying to run a marathon the next day. It's not good."

Capital Is Abundant. Experience Is Scarce. That's the Real Constraint.

When nuclear startups raise $300 million for a single project, that money can build a factory. It can buy equipment. It can pay salaries. But it can't instantly create expertise that takes decades to accumulate.

Venture capital is very good at some things: accelerating timelines, finding creative solutions to problems, applying fresh thinking to old industries. What it's not good at is replacing institutional knowledge and manufacturing expertise that has been systematically dismantled over 40 years.

You can hire some of those people. The ones still alive and working, anyway. But you can't hire enough of them for every startup to have a fully staffed team of seasoned manufacturing veterans. There just aren't enough people.

Werner sees one potentially promising approach: "A lot of startups, nuclear and otherwise, are building early versions of their products in close proximity to their technical team."

What this means is keeping manufacturing geographically close to engineering. When you're still iterating and learning, being able to rapidly test changes, see the results, and adjust is worth far more than the labor cost savings of offshoring. But it only works for early-stage production. At some point, if you want to really scale, you need to hand off to professional manufacturers or build your own mega-factories. And that's where the expertise gap bites.

Modularity Is Essential. But It's Also Harder Than It Sounds.

Werner emphasizes that modularity is crucial for nuclear startups to succeed. "Really leaning into modularity is very important for investors," she said.

Why? Because modularity lets you start small and collect data. You don't have to build five massive factories at once. You can start with one factory producing a small volume, measure how efficiently you're producing, identify problems, fix them, and iterate. As you get better, you increase volume.

This is basically the startup methodology applied to manufacturing. Small batches, fast feedback loops, rapid iteration. It works in software. It works in some hardware. Does it work in nuclear?

The theory is sound. In practice, modularity in nuclear is deceptively complex.

First, modular design is harder in nuclear than in many other industries because systems are so interconnected. You can modularize a car—wheels, engine, transmission, body—and most of those modules are somewhat independent. In a nuclear reactor, everything is integrated. The coolant system, the control system, the containment, the steam generation—they all have to work together perfectly.

Second, even if you achieve modularity in the reactor itself, you still have to build nuclear power plants. And nuclear power plants aren't just reactors. They're massive support infrastructure. Cooling towers, backup systems, security facilities, waste storage, control rooms, transformers, grid connections. A lot of that isn't going to be modular. It's site-specific and custom-built.

So you might solve the manufacturing problem for the reactor modules while still being stuck with all the traditional construction problems for everything else.

But the modularity theory is still the best bet on the table. If it doesn't work, the entire small modular reactor thesis collapses.

The Learning Curve: How Long Is This Going to Take?

Here's where the timeline question becomes critical.

Manufacturing learning curves are real. They're documented. They work. But they're also not magic, and they take time.

Werner is blunt about this: "Often it takes years, like a decade, to get there."

A decade. That's 10 years of building reactors before costs come down to levels that are economically competitive.

But most nuclear startup projections are much more optimistic. They're talking about cost reductions happening within 5-7 years. They're talking about being commercially competitive by the early 2030s.

If they're underestimating the timescale by 3-5 years, that's a massive difference. It means more capital burned before profitability. It means longer timelines before deploying reactors at meaningful scale. It means more time for competitors to emerge or for the regulatory landscape to shift.

The reason the timeline matters so much is that nuclear startups are burning through capital at prodigious rates, and the only way that works long-term is if revenue growth curves up steeply. If you're spending $500 million per year on research, development, and manufacturing ramp-up, and you're not generating revenue for 10-12 years, you need investors willing to wait an extremely long time and be comfortable with significant downside risk.

That's a different kind of venture capital than is typical in the startup world. It's closer to infrastructure investing than to growth stage VC. And the math has to work out perfectly.

The First-of-a-Kind Problem: Why the First Unit Is Always the Most Expensive

In manufacturing, there's a principle called "first-of-a-kind" or FOAK. The first unit you build is almost always the most expensive because you're still figuring out how to build it. You discover problems you didn't anticipate. You have to iterate. You have to customize. Every subsequent unit gets cheaper because you've already paid the learning costs.

But in nuclear, the first-of-a-kind problem is existential.

When Nu Scale or Commonwealth Fusion Systems builds their first operational reactor modules, those units are going to be expensive. Much more expensive than their projections. This is almost guaranteed because of the complexity of the engineering, the regulatory requirements, and the learning curve.

But the company might only get to build a handful of first-generation units before the design is locked in or before the next generation comes along. You don't get to produce thousands of identical units right away. There are customer orders to fulfill, site-specific requirements to accommodate, regulatory approvals to manage.

So the learning curve isn't as smooth as it is in automotive or consumer electronics. You might build 10 units at

And unlike Tesla, which could hide losses on early Model 3s within the broader business and use later profitability to offset, nuclear startups don't have that luxury. They're focused on nuclear. There's no other product line to cross-subsidize losses.

Regulatory Approval Is a Bottleneck, Not a Rubber Stamp

Here's something that often gets underestimated in venture capital analysis of nuclear: regulatory approval is hard, slow, and legitimately cautious.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) doesn't just rubber-stamp designs. They certify them. The certification process for an advanced reactor design can take 10-15 years. During that time, the company is burning capital without deploying a single commercial unit.

Nu Scale had its design certified in 2020, which is genuinely impressive. But even after certification, there's the licensing process for individual plants, which is different and separate. Licensing a specific site-specific reactor still takes years.

The reason for this caution isn't bureaucratic inertia. It's that nuclear accidents, while rare, are catastrophic. A software bug in an app affects a few users. A manufacturing flaw in a reactor affects potentially hundreds of thousands of people. The regulatory cautiousness is proportional to the downside risk.

This means nuclear startups can't move at startup speed. They can move faster than traditional utilities, maybe, but they're still constrained by the pace of regulatory approval.

And here's the kicker: if a startup gets regulatory approval for a design and then discovers a problem in the first few units produced, the regulatory process starts again. The design might need changes. Those changes might require recertification. It's a potential death spiral.

Tesla could ship cars with software bugs and push fixes over the air. Nuclear can't do that.

Supply Chain Resilience: Building Domestic Suppliers From Scratch

Let's go deeper on the supply chain problem because it's genuinely thorny.

Nuclear reactors need specific materials: specialized alloys, ceramics, components that can withstand intense radiation and heat. Some of these materials are specialized to the point where there are only a handful of suppliers globally. Many of those suppliers are in countries that are geopolitically uncertain or actively hostile to the United States.

To solve this, the government and startups are talking about rebuilding domestic supply chains. But rebuilding a supplier takes time and requires demand.

Here's the bootstrap problem: Suppliers are hesitant to invest in capacity to produce nuclear materials if there's no guaranteed demand. But nuclear startups can't commit to large purchase orders until they have a design locked in and production ramped up. Until they're actually building dozens of reactors per year.

So you're stuck in a catch-22. Startups need suppliers. Suppliers need committed orders. Nobody wants to go first.

The government is trying to solve this with subsidies and direct investment, which helps. But it requires political will that might not persist across administrations.

Domestically rebuilding supply chains for specialized nuclear materials could cost tens of billions of dollars and take 5-10 years even with aggressive government support. Add that timeline onto the nuclear startup timeline, and you're looking at a decade before anything meaningful hits the grid at competitive costs.

The Financing Question: Can Startups Afford the Wait?

Venture capital is patient, but it's not infinitely patient.

A typical VC fund has a lifespan of 10 years. LPs (limited partners who provide the capital) expect returns within that window. If a nuclear startup is projecting breakeven in year 12, that's a problem for standard VC.

There are specialized funds for long-duration infrastructure, and nuclear has attracted some of that capital. But the majority of funding nuclear startups are raising is coming from traditional climate tech VCs, which operate on traditional timescales.

This creates pressure on startups to accelerate timelines or hit revenue targets sooner than is realistic. Which in turn creates risk of cutting corners or over-promising results.

The companies that will succeed in nuclear are probably the ones that have secured patient capital from sources that understand they won't see returns for 10-15 years. That might be government agencies, large strategic investors with long time horizons (like utilities), or family offices.

Traditional venture capital might not be the right fuel source for this industry after the early stage.

Manufacturing Locations and Geographic Advantages

Where do nuclear startups build their factories?

There's significant political pressure to locate factories in the United States, particularly in regions that have lost manufacturing jobs. There are also tax incentives and direct subsidies for building domestically.

But here's the complication: the U.S. doesn't have a lot of infrastructure ready to support a new, large-scale manufacturing effort. You'd need to build or renovate a facility, get it certified, staff it, and then start producing. That's a multi-year effort.

Some startups are considering building initial manufacturing capacity in countries with stronger manufacturing infrastructure, like Japan or parts of Europe. This solves some of the expertise and supply chain problems, but it creates political problems and supply chain vulnerability.

The optimal solution is probably to build domestic manufacturing capacity with international partnerships, learning from experienced manufacturers in other countries while creating genuine American jobs and reducing supply chain risk.

But optimal solutions take longer and cost more than suboptimal ones.

The Competition Problem: How Many Winners Can There Be?

There's an assumption in venture capital that multiple companies can win in any market. Competition drives efficiency and innovation.

But nuclear is a capital-intensive industry with massive fixed costs and regulatory moats. It's more like aerospace than like software.

Can three SMR companies be simultaneously profitable? Five? Ten?

Probably not all of them. There will be consolidation. Some companies will fail. Some will be absorbed. The ones that survive will have either achieved massive cost advantages through manufacturing scale, or they'll have locked in government contracts with stable long-term demand.

Venture capital has funded 100 companies competing for the same market before. Usually, that results in winners and losers, with the winners capturing most of the value. In nuclear, there are fewer potential slots for winners because deploying reactors is a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar commitment that utilities and governments don't make casually.

This means a lot of the capital being raised by nuclear startups right now might ultimately not generate returns. The winners will be spectacular. The losers will burn through billions.

Investors understand this intellectually. But it's easy to get caught up in the enthusiasm and forget how brutal the shakeout will be.

International Competition: Why American Startups Aren't the Only Players

When people think about nuclear startups, they often think about American companies: Commonwealth Fusion Systems, X-energy, Nu Scale, Oklo. These companies are well-funded and well-publicized.

But there's an entire world of nuclear companies outside the U.S., and some of them have significant advantages.

Companies in Canada, France, South Korea, Japan, and Russia have state backing and less financial pressure. They're playing a longer game. Some of them have decades of operating experience with reactors. They understand nuclear supply chains because they've been building reactors.

Canada has been pushing small modular reactors aggressively through companies like ARC Clean Energy. France, despite its focus on large reactors, has companies developing SMRs. South Korea and Japan have explicit government support for new reactor designs.

The competition for global dominance in SMR technology isn't just American venture capital firms fighting each other. It's international competition, and some of the other players have resources and experience that American startups lack.

If an American startup's competitive advantage is manufacturing efficiency and modern design, but a Korean company can leverage government support and existing manufacturing expertise, which wins?

That's an open question. But it suggests the nuclear startup market is more complex than just the companies with the highest venture valuations.

Bridging the Gap: Real Solutions to Real Problems

Given all these challenges, what actually needs to happen for nuclear startups to succeed?

First, they need to accept that manufacturing expertise can't be bought instantly. Building a manufacturing base requires hiring, training, and retaining people. That's a multi-year project. Starting early, learning from mistakes, and iterating is essential.

Second, they need patient capital sources. Traditional venture capital might fund early-stage R&D, but scaling manufacturing requires different kinds of investors. Utilities, government, infrastructure funds, and strategic investors need to be part of the capital stack.

Third, supply chain development needs to be treated as a strategic priority, not an afterthought. This probably requires government support, potentially including direct investment in building domestic supplier capacity.

Fourth, modularity isn't just a design principle, it's a risk management tool. Designing reactors so that you can iterate, test, and improve incrementally is essential when you're in a high-stakes industry.

Fifth, partnerships with experienced manufacturers in other countries could accelerate learning and de-risk the manufacturing process. This might mean joint ventures, licensing arrangements, or strategic partnerships.

Sixth, regulatory agencies need to stay engaged as partners, not obstacles. Uncertainty about what the NRC will require creates risk and delays. Clear, predictable regulatory pathways are valuable.

Seventh, companies that can demonstrate real progress on manufacturing and cost reduction will deserve more credibility than companies making optimistic projections. The companies proving the learning curve works will attract the next wave of capital.

The Clock Is Ticking: Why Timelines Matter Now

Here's the thing that makes the next 2-3 years crucial: nuclear startups need to demonstrate material progress on actual manufacturing.

Not just in R&D or in simulations. Real factories producing real components, achieving real cost reductions. Data that shows the learning curve is actually working.

If that doesn't happen, if the first units come in massively over budget and behind schedule, investor sentiment will shift quickly. Climate tech is hot right now, but that can change. If nuclear startups become seen as capital-intensive boondoggles that don't deliver, the funding dries up.

On the flip side, if even one or two companies can demonstrate that they're manufacturing competently and hitting cost targets, the entire sector gets de-risked. That company becomes a proof point. Others attract more capital. The ecosystem accelerates.

This is why the next couple of years are so important. They're the inflection point where the theory either becomes practice or becomes another cautionary tale.

Looking Forward: What Happens Next

The most likely scenario is that the nuclear startup boom continues, but with consolidation and shakeout along the way.

Some companies will fail. Some will be acquired by larger utilities or industrial companies that have the manufacturing expertise to execute. Some will succeed by partnering with experienced manufacturers rather than trying to build everything themselves.

A small number will achieve genuine breakthroughs in manufacturing efficiency and cost reduction. Those companies will be enormously valuable because they'll have cracked a problem that seemed intractable: how to build nuclear reactors at reasonable cost and timeline.

The industry will probably end up looking different than anyone is currently predicting. There will be more international players than expected. There will be more government involvement than venture capitalists are comfortable with. There will be more partnerships and fewer pure-play startups than the current hype cycle suggests.

But the underlying thesis—that small modular reactors can be manufactured more efficiently than massive traditional reactors—is probably right. The execution is just a lot harder than it looks from a venture capital spreadsheet.

For the nuclear startups that can navigate manufacturing reality without losing sight of the vision, the upside is enormous. They're potentially enabling a future where nuclear power plays a much larger role in global energy and climate solutions.

For investors, the challenge is distinguishing between genuine progress and compelling storytelling. The companies with manufacturing data beats the companies with Power Point slides. Every time.

FAQ

What are small modular reactors and how do they differ from traditional nuclear plants?

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are nuclear reactors that produce between 50-300 megawatts of electricity, compared to traditional reactors which often exceed 1,000 megawatts. SMRs are designed for factory manufacturing rather than on-site construction, multiple units can be combined for increased power output, and they theoretically enable cost savings through mass production and economies of scale.

Why are nuclear startups betting on mass manufacturing to reduce costs?

The learning curve in manufacturing shows that costs typically drop 10-20% with each doubling of cumulative production. Nuclear startups believe that by moving from custom on-site construction to factory-based mass production, they can achieve significant cost reductions over time, similar to what happened in automotive and consumer electronics industries, though the analogy isn't perfect.

What is the main challenge preventing nuclear startups from immediately reducing costs?

The United States has not built significant industrial facilities in 40 years, resulting in a loss of manufacturing expertise and institutional knowledge. Key materials needed for nuclear reactors are no longer manufactured domestically, and there aren't enough experienced manufacturing professionals to staff all the new factories that startups are planning to build simultaneously.

How long will it actually take for small modular reactor costs to become competitive?

Experts indicate that the learning curve from manufacturing experience typically takes a decade or longer to achieve meaningful cost reductions. While optimistic startup projections suggest competitive costs by the early 2030s, manufacturing veterans suggest the timeline could extend to 2035-2040 before costs are truly competitive without subsidies.

What role does regulatory approval play in delaying nuclear startup deployment?

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission certification process for advanced reactor designs can take 10-15 years, and site-specific licensing adds additional time. Unlike other industries where companies can ship products and iterate, nuclear reactor changes during manufacturing or operation can trigger recertification requirements, making rapid iteration impossible.

Are there successful examples of manufacturing scaling that nuclear startups can learn from?

Tesla's Model 3 production ramp-up shows both possibilities and pitfalls—the company achieved mass production but struggled significantly with profitability and quality control despite having automotive manufacturing expertise in the U.S. Nuclear startups face additional challenges because the U.S. lacks equivalent domestic nuclear manufacturing expertise and the regulatory stakes are far higher.

What would it take for nuclear startups to actually succeed at manufacturing scale?

Success requires patient capital sources (beyond traditional venture capital), early focus on supply chain development with government support, genuine partnerships with experienced manufacturers, demonstrated progress on actual cost reduction through manufacturing data, and realistic timelines that acknowledge the 10+ year path to competitiveness.

How many nuclear startup companies can actually become profitable?

Given the capital intensity, regulatory moats, and limited addressable market for reactor deployment, fewer companies will succeed than are currently being funded. The market will likely support only a handful of profitable nuclear manufacturers globally, with consolidation and failures concentrated among companies that fail to demonstrate manufacturing competence.

Key Takeaways

- Nuclear startups raised $1.1B in late 2025 alone, driven by climate urgency, AI power demands, and government support initiatives

- The core thesis is sound: small modular reactors manufactured at scale could reduce costs through learning curves, but execution faces severe expertise and supply chain constraints

- Manufacturing expertise doesn't exist domestically—the U.S. hasn't built significant industrial facilities in 40 years and has lost institutional knowledge required for nuclear manufacturing

- Realistic timelines for cost competitiveness are 10+ years, not the 5-7 year projections many startups are making—learning curves take longer in highly regulated industries

- The first-of-a-kind problem is acute in nuclear: early reactor units will be extremely expensive, and companies may only build a handful before designs lock in

![Nuclear Startups and Small Modular Reactors: Can Manufacturing Really Fix the Problem? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nuclear-startups-and-small-modular-reactors-can-manufacturin/image-1-1768149327204.jpg)