The AI Power Crisis: Why Meta Is Going Nuclear

There's a problem hiding in plain sight at the world's largest tech companies. It's not a security breach, a regulatory crackdown, or a market crash. It's electricity.

Artificial intelligence training and inference consume staggering amounts of power. A single query to a large language model uses roughly the same electricity as charging your phone. Scale that to billions of queries daily, and you're looking at power requirements that rival small cities. Meta, OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft have all realized the same thing: they can't build their AI futures on the grid as it exists today.

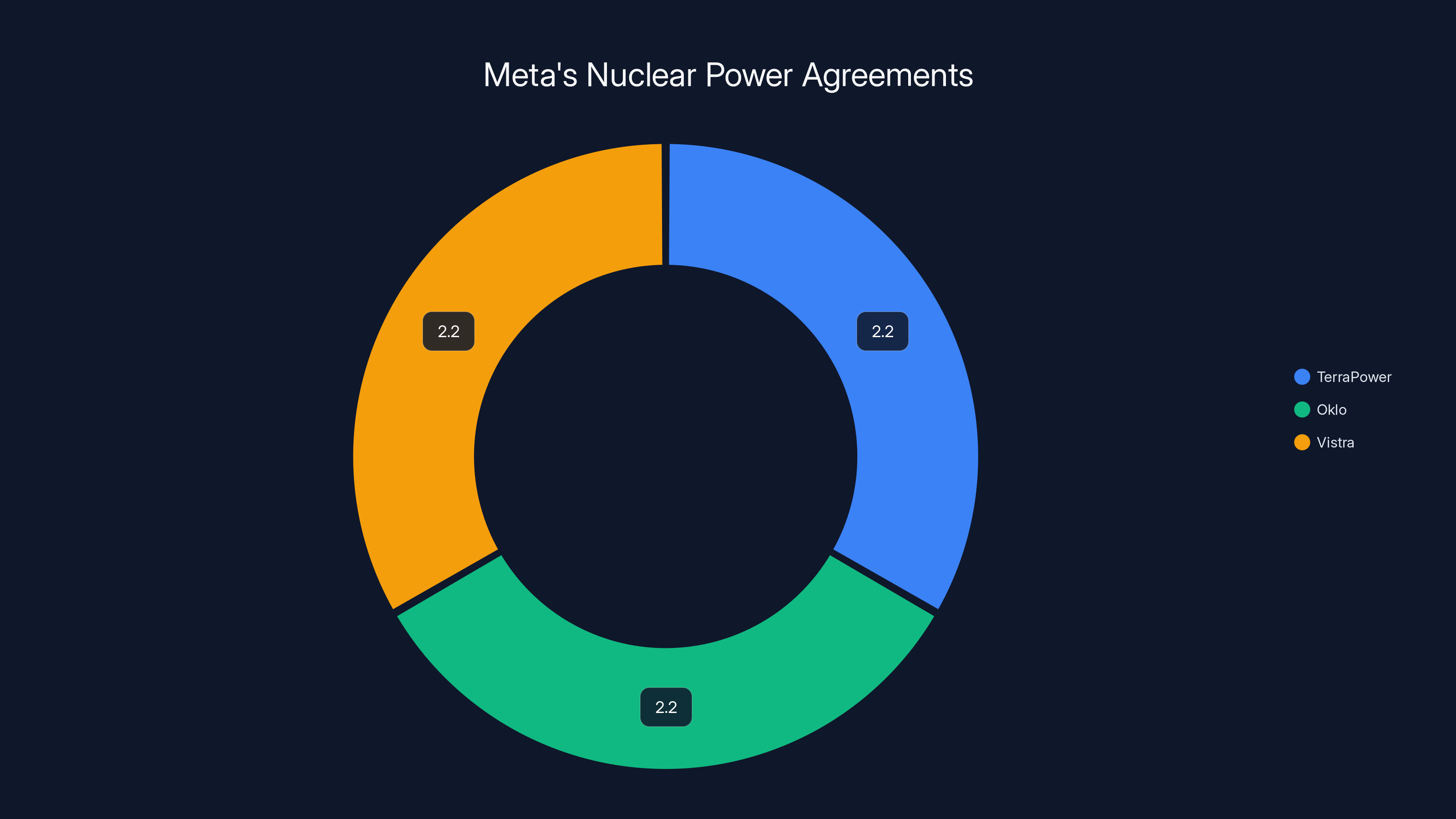

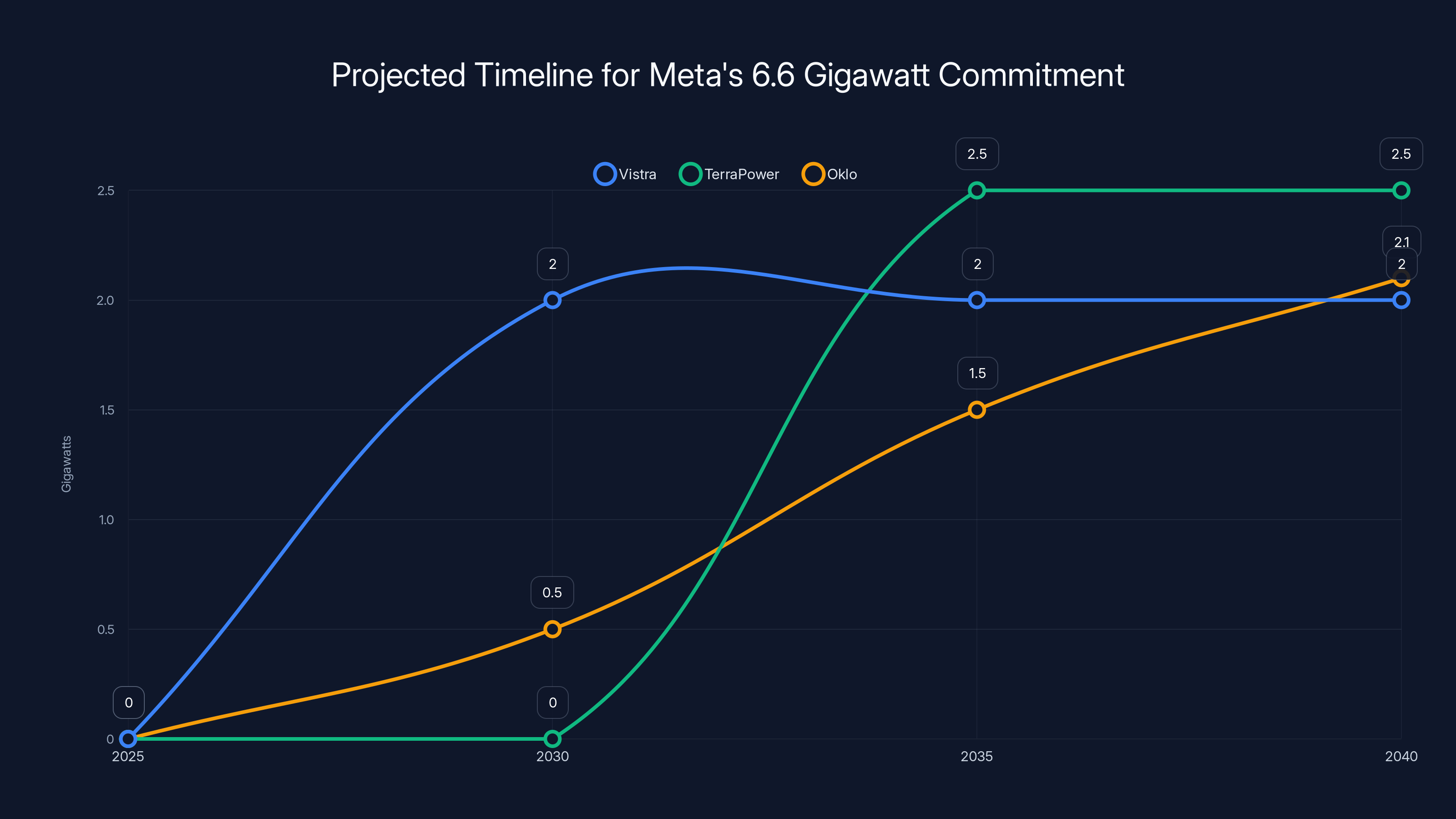

So Meta just made a historic bet. The company announced partnerships with three nuclear energy providers—Terra Power (backed by Bill Gates), Oklo (backed by Sam Altman), and Vistra—to secure 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear power by 2035. To put that in perspective, that's enough electricity to power all of Ireland. The first reactors could come online as early as 2030.

This isn't a press release buried on page 12. This is Meta announcing it's becoming one of the largest corporate nuclear power purchasers in American history. It's a signal that the AI arms race has entered a new phase, where energy infrastructure isn't a commodity—it's a competitive moat.

But here's what most coverage missed: this deal reveals something fundamental about the future of tech, energy policy, and the race for AI supremacy. The companies winning the AI competition won't be the ones with the smartest algorithms. They'll be the ones who can reliably power those algorithms.

Let's dig into what Meta's nuclear gamble means, why it matters, and what it tells us about where tech is headed.

Understanding the Energy Hunger of Modern AI

I need to give you some numbers first, because they sound outrageous until you sit with them for a moment.

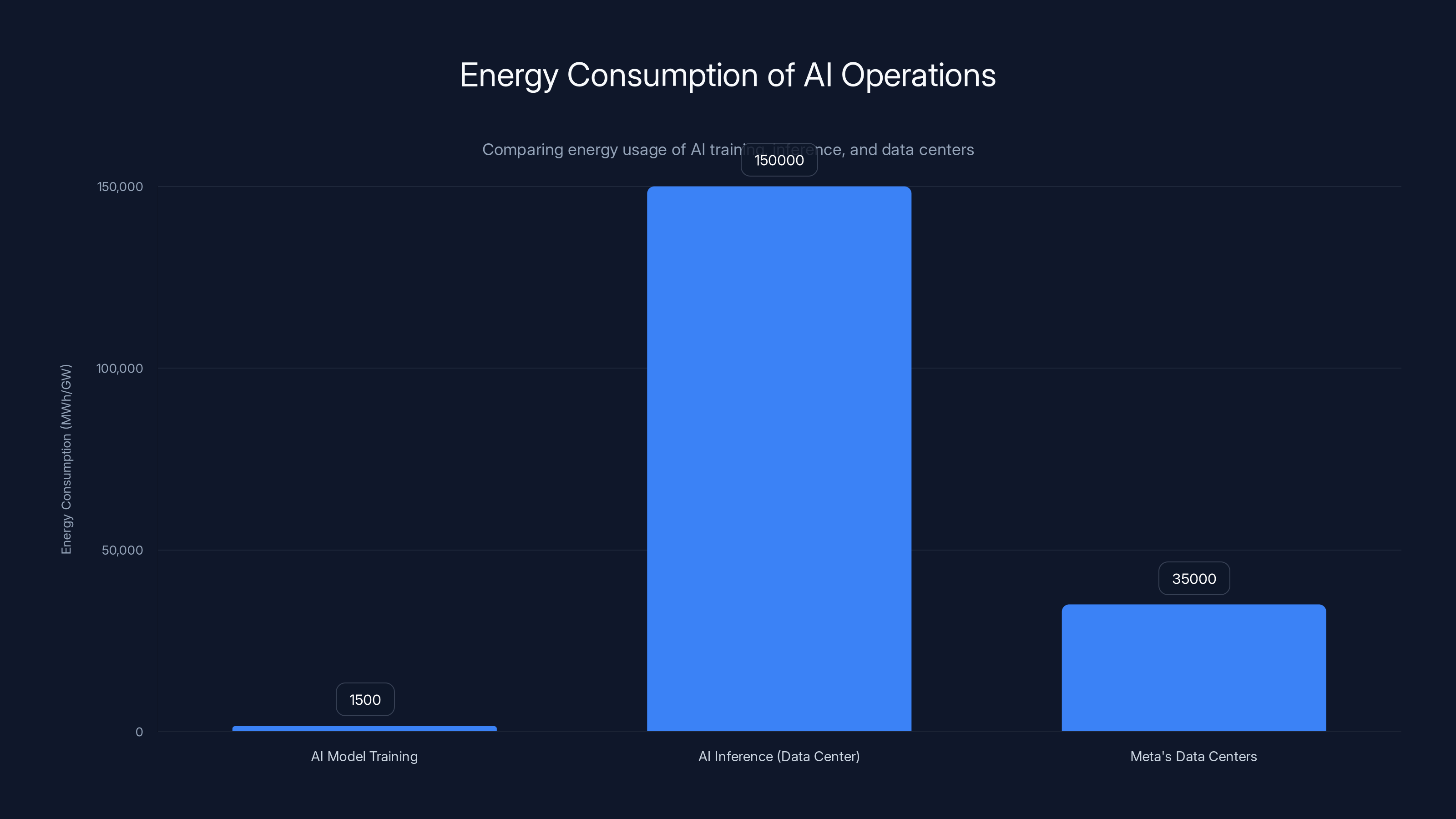

Training a single large language model can consume between 1,300 to 1,700 megawatt-hours of electricity. That's the annual household electricity consumption of 130 to 170 American homes. For one model. From one company.

But training is just the appetizer. Once a model is live, inference—running predictions on that model—creates ongoing power demand. A single data center running modern AI models might consume 100 to 200 megawatts continuously. That's comparable to a small coal plant running 24/7.

Meta's data centers currently consume an estimated 30 to 40 gigawatts of power across all operations. When you factor in the next generation of AI models, supercluster compute systems, and expanding inference workloads, that number could double within five years.

Here's the catch: the electrical grid isn't designed for this. Most grid infrastructure was built in the 1970s and 1980s with the assumption that data centers would be modest users of power. They're now among the largest consumers in their regions, and the demand is accelerating.

Renewable energy (solar and wind) seems like the obvious answer. It's clean, costs are dropping, and it's politically popular. But renewables have a fundamental problem for data center operators: intermittency. Solar works during the day. Wind works when it's windy. But AI inference doesn't pause when the sun sets. Your Chat GPT queries don't wait for favorable wind conditions.

This is where nuclear enters the conversation. Nuclear plants run 24/7, baseload power with capacity factors (percentage of maximum power delivered) around 92 percent. They're carbon-free, incredibly reliable, and dense—a single reactor produces gigawatts from a footprint smaller than a modern shopping mall.

For Meta and other tech giants, nuclear isn't an environmental choice. It's a practical necessity dressed in a sustainability marketing campaign.

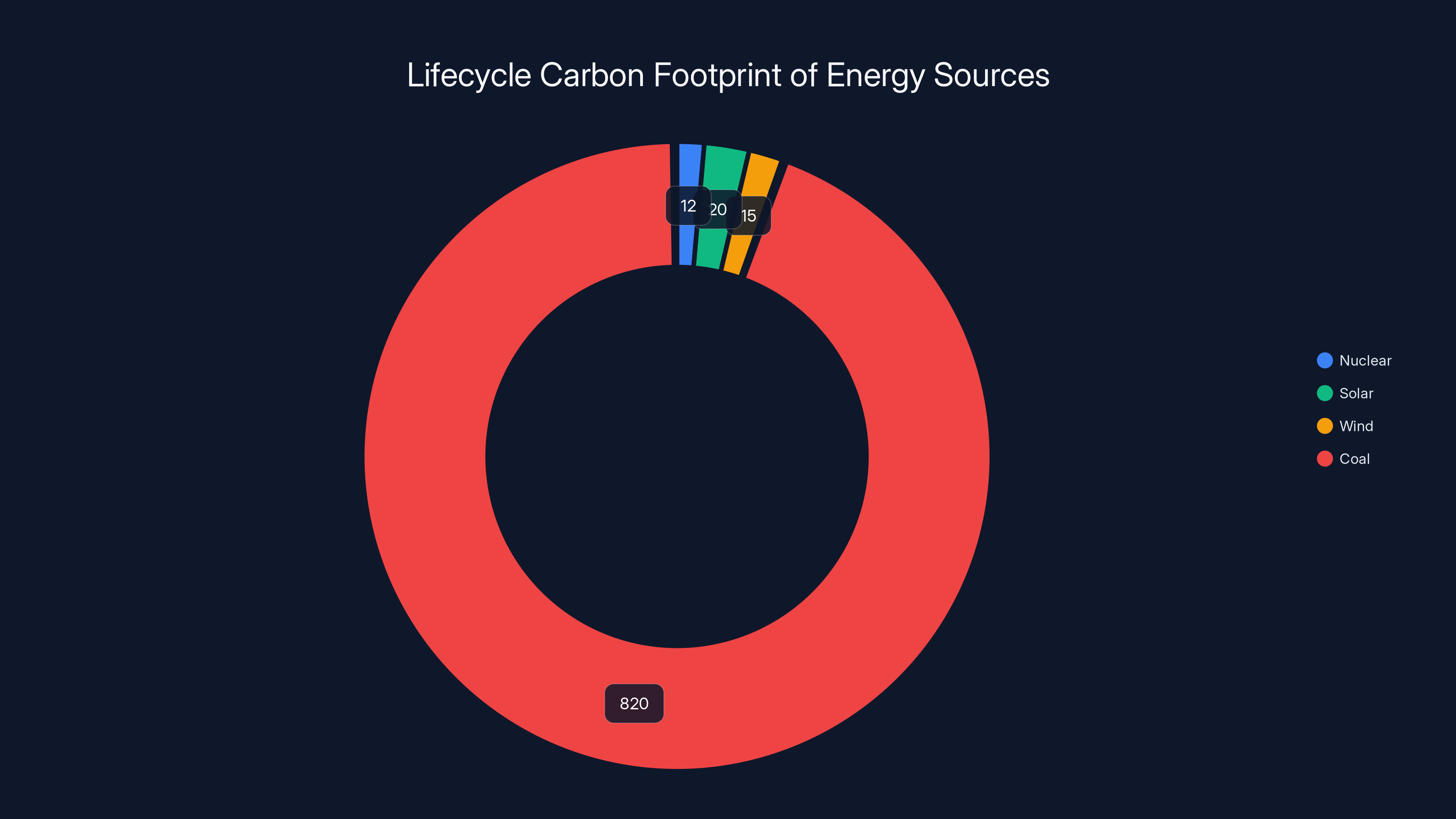

Nuclear, solar, and wind have significantly lower lifecycle carbon footprints compared to coal. Nuclear is comparable to wind and solar, despite initial construction emissions. Estimated data.

The Players: Terra Power, Oklo, and Vistra

Meta's deal involves three very different types of nuclear operators, each bringing something distinct to the table.

Terra Power, backed by Bill Gates, represents the moonshot thinking. The company has spent over a decade developing advanced reactor designs, specifically Natrium reactors that use molten salt cooling instead of water. Natrium reactors are smaller than traditional reactors, generate less waste, and can be built more quickly. They're not theoretical—Terra Power broke ground on a demo plant in Wyoming a few years ago.

The appeal for Meta is simple: Terra Power can build new capacity rather than relying on aging nuclear infrastructure. By 2035, having fresh Natrium reactors online could provide significant power. But there's also a timeline risk. Advanced reactors have never been built at scale in the United States. Regulatory approval, construction delays, and technical issues are all possible.

Oklo, Sam Altman's nuclear play, focuses on microreactors. These are tiny—think the size of a large shipping container—and designed to be deployed in clusters. One interesting angle: Oklo's reactors run on spent nuclear fuel from existing reactors, turning waste into an asset.

For data center operators, microreactors offer modularity. Instead of betting everything on one massive plant, you can install multiple smaller reactors, spreading risk and adding flexibility. Oklo's power output per reactor is modest, but scale matters more than single-reactor capacity.

Vistra is the established player. It's a major energy company that already operates nuclear plants, coal plants, and battery storage. Vistra brings operational expertise, regulatory relationships, and existing infrastructure. The company already manages multiple nuclear facilities, so adding more capacity is familiar territory.

Vistra's role in Meta's deal is stabilizing. While Terra Power and Oklo bring innovation, Vistra brings reliability. The company can likely deliver megawatts to Meta faster than the advanced reactor startups.

What's remarkable is that Meta found room for all three. This isn't a "pick your favorite" situation. It's Meta saying: we need everything. We need proven capacity from Vistra, next-generation tech from Terra Power, and scalable solutions from Oklo.

The 6.6 Gigawatt Commitment: What It Actually Means

Numbers this large become abstract. Let me ground 6.6 gigawatts in reality.

One gigawatt of power running continuously for a year produces about 8.76 terawatt-hours of electricity. That's enough to power roughly 800,000 homes for a year. Six gigawatts is enough for 4.8 million homes.

But here's the subtlety: 6.6 gigawatts is a target by 2035. That's ten years away. It's not power Meta has today. It's not even power Meta will definitely have then, because advanced reactor projects slip.

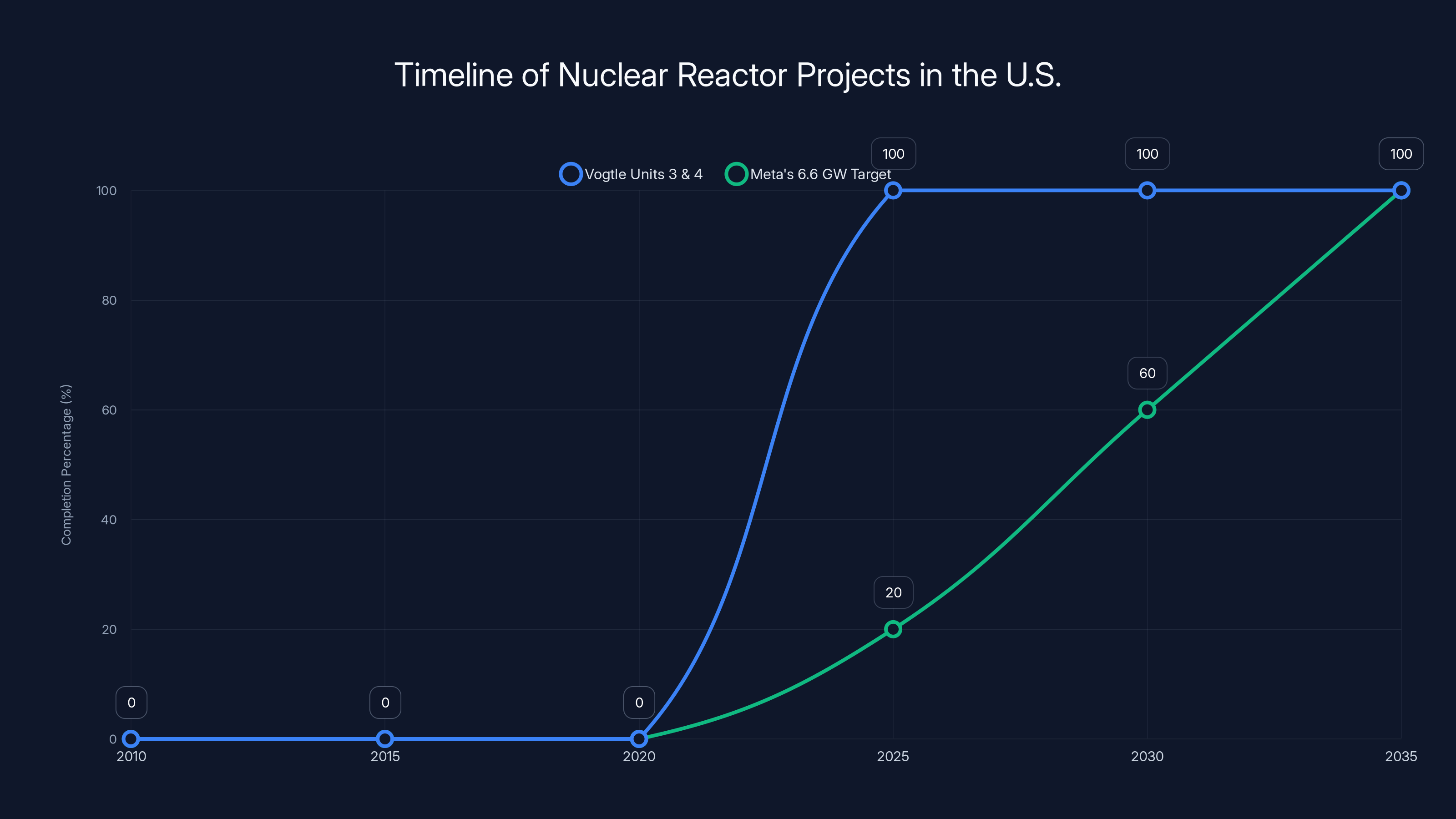

The timeline is important. Meta is committing to funding reactor construction, but these projects have a history of delays. The Vogtle expansion in Georgia, which added two reactors to an existing site, took 15 years to complete. The Oklo microreactors are cutting-edge, which means regulatory approval is uncharted territory.

What Meta is really doing is placing bets across multiple timelines. Vistra can probably deliver capacity by 2030. Terra Power might hit late 2030s. Oklo's deployment is more flexible—microreactors can go online in smaller batches. By spreading commitments across three partners with different timelines and technologies, Meta hedges against any single project failing or delaying.

The financial commitment is also interesting, though Meta hasn't disclosed numbers. The company says it will "pay the full costs for energy used by our data centers so consumers don't bear these expenses." Translation: this is expensive, and Meta is covering it. Advanced reactors cost billions to develop. Terra Power's Wyoming demo reactor ran over budget. Oklo's path to profitability is years away.

Meta is essentially funding the development of next-generation nuclear infrastructure. It's an investment in the future of both its own operations and the nuclear industry itself.

Meta's nuclear power agreements distribute 6.6 gigawatts evenly among TerraPower, Oklo, and Vistra, ensuring a balanced energy supply for its AI data centers. Estimated data.

Why Nuclear? The Competitive Advantage Angle

Here's where the strategy gets interesting. Nuclear power isn't just about solving the energy problem. It's about control.

When you rely on the grid, you're dependent on utility companies, regulatory bodies, and competing industries. During a heat wave, power prices spike. During a tight energy market, you compete with everyone else for available capacity. Your ability to scale AI operations becomes limited by factors you don't control.

But when you own or have long-term contracts for baseload nuclear power, you own your destiny. You know exactly how much power you'll have, exactly how much it will cost, and exactly when it will be available. This matters enormously when you're competing with Google, Amazon, and others for AI dominance.

AI model quality increasingly depends on compute. More compute means bigger models, better training, faster inference. But compute requires power. Companies that secure cheap, abundant, reliable power will win. Companies that don't will hit a ceiling.

Meta's nuclear deal is a public declaration that the company believes it will win the AI race—and it's willing to bet billions on the infrastructure to make that possible.

There's also a regulatory and political angle. Building new nuclear capacity is politically fraught. It requires federal approval, environmental review, and community support. By being the anchor tenant—the company funding construction and guaranteeing to buy the power—Meta gets influence over where reactors are built and how quickly they move through permitting.

This is how industry gets built. Railroads were financed by companies that needed to move goods. Electricity infrastructure was built by companies that needed power. Tech infrastructure is being built by companies that need compute and energy. Meta's nuclear deal is structural investment in the future of its own industry.

The Constellation Connection: Meta's Earlier Nuclear Bet

Meta's nuclear ambitions didn't start with Terra Power and Oklo. Last year, the company announced a deal with Constellation Energy to revive the retired Three Mile Island nuclear plant.

Yes, that Three Mile Island. The site of the worst nuclear disaster in US history. In 1979, a cooling system failure caused a partial meltdown. It killed the American nuclear industry for decades.

Constellation is reopening Unit 1 at the site, which had been shut since 1974 (the 1979 incident was Unit 2). The plant will have a capacity around 800 megawatts, and Meta has agreed to purchase most of that power through a long-term contract.

This deal was quietly significant but didn't get the attention it deserved. Here's why: it showed that Meta was already serious about nuclear. Here's why it matters now: it establishes a pattern.

The Three Mile Island deal gives Meta power in the near term (the plant is expected to come back online by late 2024). The new reactor builds from Terra Power, Oklo, and Vistra represent longer-term capacity expansion. Together, they show a company thinking about energy in 5-year, 10-year, and 20-year timeframes.

It also signals something important about nuclear's future in America. For decades, the industry was treated as a relic. New reactor projects were nearly impossible to get built. But the combination of climate pressure (nuclear is zero-carbon), energy security (we want domestic power generation), and AI demand (everyone needs power) is creating the first conditions in 40 years for nuclear expansion.

Meta's deals aren't saving nuclear. But they're the kind of anchor tenant commitments that make new nuclear projects viable.

What This Means for Other Tech Companies

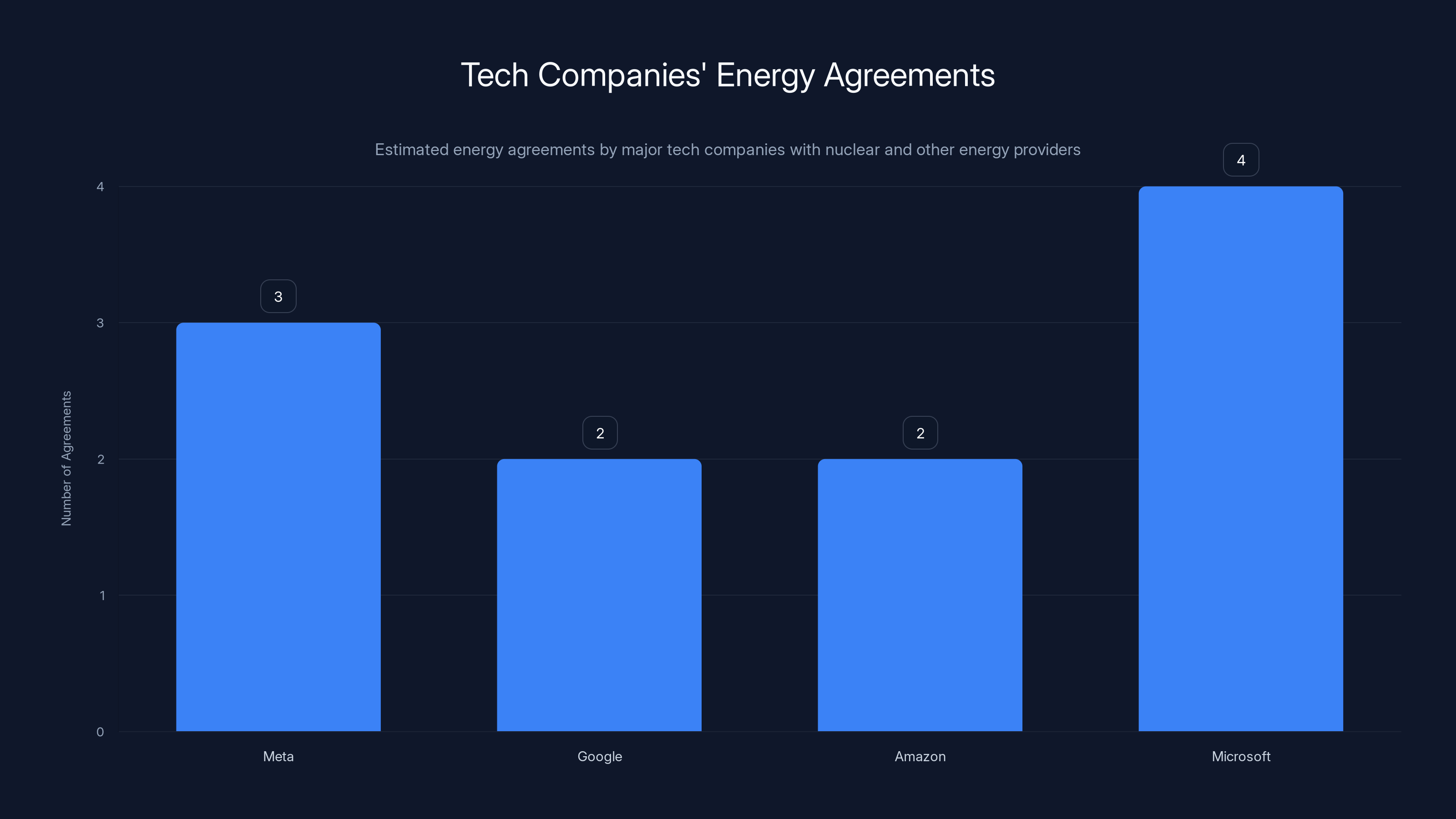

Meta isn't alone. Google and Amazon are making similar moves.

Google signed a power purchase agreement with Kairos Power to supply electricity from advanced reactors. Amazon signed agreements with Energy Northwest and possibly others. Microsoft has agreements with various energy providers including nuclear options.

What Meta's deal makes explicit is something the industry has been whispering: tech companies are now the largest players in energy markets. They're not buying leftover capacity. They're funding the construction of new infrastructure.

This creates interesting dynamics. Utilities used to plan capacity based on forecasted population and economic growth. Now they're planning based on tech company energy demands. A single data center can consume more power than a mid-sized city.

For other tech companies, Meta's nuclear push creates competitive pressure. If Meta secures long-term, cheap nuclear power and competitors don't, Meta gains a structural advantage in AI compute costs. This could drive a nuclear bidding war among tech giants.

We might see OpenAI, Anthropic, or other AI companies making similar announcements. The race for AI dominance is increasingly a race for energy dominance.

AI model training consumes 1,300-1,700 MWh, while inference in data centers can reach 100-200 MW continuously. Meta's data centers use 30-40 GW, potentially doubling in five years. (Estimated data)

The Advanced Reactor Revolution: Why It Matters Now

For 30 years, nuclear innovation stalled. Every reactor built in the United States was a variation on light water reactor designs from the 1970s. The industry became conservative, defensive, and slow.

But starting in the 2010s, a new generation of nuclear companies emerged. They weren't bound by the legacy of the nuclear industry. They designed new reactor types, smaller reactors, safer reactors.

Terra Power's Natrium reactor uses molten salt instead of water for cooling. This has advantages: molten salt can handle higher temperatures, which means better thermodynamic efficiency. It also means the reactor can be smaller while producing the same output.

Oklo's microreactors are modular. Instead of one massive 1,000-megawatt reactor, you deploy multiple 10-megawatt units. This creates redundancy, allows for phased expansion, and reduces the risk if a single unit fails.

X-energy, Nu Scale, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, and others are all developing alternative designs. Most are in early stages, but the portfolio approach means some will succeed.

Meta's deal with these companies is a bet that advanced reactors will work better than traditional ones. It's also a bet that they'll be built faster and safer.

Here's the practical implication: Meta's 6.6 gigawatt target by 2035 would have been technically impossible ten years ago. The nuclear industry simply wasn't capable of building that much new capacity. But with advanced reactors, it's ambitious but possible.

This is how technology transitions work. New entrants (Terra Power, Oklo) develop new designs. Big customers (Meta) commit to buying power. Regulatory frameworks evolve. Over a decade or two, the old way of doing things gets replaced.

We're watching nuclear power enter that transition now.

The Environmental Narrative: Clean Energy vs. Reality

Meta's announcements are heavy on environmental claims. Nuclear power is zero-carbon. Building new reactors fights climate change. AI innovation supported by clean energy creates a better future.

This is true. But it's incomplete.

Nuclear power generation itself produces no carbon emissions. But building nuclear plants requires massive amounts of materials and energy. Mining uranium, enriching it, manufacturing reactor components, transporting them—these all have carbon costs.

That said, over a reactor's 60-year operating life, the carbon cost of construction is amortized to near-zero. A reactor operating for six decades produces electricity with a lifecycle carbon footprint comparable to wind and solar.

The honest take: nuclear is clean energy. It's also the most land-efficient energy source. A nuclear plant produces gigawatts from a few acres. Solar and wind need exponentially more land to produce the same power.

But here's the thing: the environmental framing is partially marketing. Meta's primary motivation isn't climate justice. It's competitive necessity. The company needs power. Nuclear is the most reliable, dense, and controllable way to get it. The climate benefits are real but secondary.

We should be clear-eyed about this. Tech companies are buying nuclear power because it solves their business problems, not because they're climate heroes. That they're reducing carbon emissions in the process is good. But it's important not to confuse competitive necessity with environmental virtue.

Regulatory and Political Hurdles Ahead

Here's where the rosy scenario gets complicated.

Building nuclear reactors in the United States is hard. Not scientifically hard—advanced reactors are proven designs. But bureaucratically hard. The regulatory process takes years. Environmental reviews take years. Community approval processes take years.

Vogtle Expansion Units 3 and 4 in Georgia broke ground in 2013 and won't begin operation until 2025 (or later). That's over a decade. Costs ballooned from an initial estimate of

Meta's 6.6 gigawatt target by 2035 requires completing multiple reactor projects on aggressive timelines. If any major project slips by 2-3 years, Meta won't hit the target.

Regulatory reform is part of the equation. Both Democratic and Republican administrations have recognized that nuclear permitting is too slow. Recent legislation has streamlined some processes for advanced reactors. The Biden administration pushed to accelerate nuclear development. The Trump administration is likely to continue this, as both parties now see nuclear as essential to energy security.

But even with streamlined permitting, building nuclear plants takes time. You can't compress physics and engineering timelines just because you're well-funded.

There's also the waste question. Nuclear plants generate radioactive waste. The United States still doesn't have a permanent repository (Yucca Mountain was shelved decades ago). Waste management is a political problem more than a technical one—the technology for storing waste safely exists, but communities don't want it in their backyard.

Meta's partnership with Oklo partly sidesteps this because microreactors can use spent fuel from existing reactors, turning waste into fuel. But Terra Power and traditional reactors will still generate waste that needs disposal.

These aren't showstoppers, but they're real constraints on how quickly Meta's nuclear buildout can happen.

The Vogtle Units 3 & 4 project highlights the lengthy timeline for nuclear projects, taking over a decade to complete. Meta's ambitious 6.6 GW target by 2035 requires significant acceleration in project timelines. (Estimated data)

The Global Angle: Who Else Is Going Nuclear?

Meta's deal is significant, but it's not unique. Tech companies worldwide are pursuing nuclear power.

Google's partnership with Kairos Power is part of a broader strategy to power AI infrastructure with clean energy. The company has been aggressive about renewable contracts for years and is now adding nuclear to the mix.

Amazon, Microsoft, and others are quietly negotiating with utilities and nuclear operators. In Europe, companies are looking at existing nuclear capacity. France, with its abundant nuclear power, is becoming an attractive location for AI data centers.

China is building nuclear plants at an unprecedented pace, largely to power manufacturing and AI operations. By 2030, China will likely have more nuclear capacity than the United States.

This creates a geopolitical angle. Nuclear power is increasingly tied to AI capability. Countries with abundant clean power have structural advantages in hosting data centers and AI infrastructure. This gives governments incentive to accelerate nuclear development as a strategic priority.

Meta's deal, combined with similar moves from other tech giants, is likely to trigger government-level energy policy shifts. If AI is strategically important (and most governments believe it is), then energy infrastructure is strategically important.

We may see more government funding for advanced nuclear, faster permitting, and explicit priorities around nuclear development for AI.

The Cost Question: Is Nuclear Really Affordable?

Meta says it will "pay the full costs" for the nuclear power. But what does that mean?

Advanced nuclear is expensive. Terra Power's Wyoming project was originally estimated at $2 billion and may cost significantly more. Oklo's microreactors cost millions per unit to design and build. These are not cheap technologies.

However, cost curves matter. When you build the first-of-a-kind reactor, it's expensive. But building the tenth of the same design becomes cheaper. As advanced reactor manufacturers build more units, costs come down.

Meta's commitment to buy power from multiple projects helps this cost curve. By providing demand certainty, Meta makes it financially viable for companies to invest in manufacturing and optimization.

The real cost question is: what's the alternative? If Meta needed to rely on grid power for AI compute, it would face competing demand during peak hours, price spikes during shortages, and expansion limitations as utility capacity hits ceiling. Having dedicated nuclear power might cost more per megawatt-hour than average grid prices, but it's far cheaper than not having power when you need it.

For Meta, the nuclear bet is an insurance policy. It guarantees access to reliable power at a known cost, eliminating a strategic risk.

What About Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)?

When you read about the nuclear future, you'll hear the acronym SMR: Small Modular Reactor.

SMRs are a different category from what Meta is buying. They're smaller (typically 10-50 megawatts), modular (designed to be mass-produced), and potentially cheaper per unit than large reactors.

The promise of SMRs is that they could be deployed at scale across many sites, rather than building massive plants in select locations. Factory manufacturing means potential cost reductions through economies of scale.

But SMRs haven't yet proven they're actually cheaper. Per-megawatt costs are often higher than conventional reactors because you lose economy of scale on individual projects. To make SMRs financially viable, you need massive volume.

Oklo's microreactors are sort of in the SMR family, though at the very small end of the spectrum. Oklo is explicitly betting that deployment volume will drive costs down.

Meta's partnerships with Oklo (microreactors) and Terra Power (smaller Natrium reactors) include smaller-scale technologies. The company is diversifying across reactor types and sizes.

But for Meta's near-term needs (2030 and earlier), the company is likely relying more on traditional reactor capacity from Vistra, not waiting for SMRs to mature.

Estimated deployment timeline shows Vistra potentially delivering by 2030, TerraPower by late 2030s, and Oklo with flexible deployment. Estimated data.

The Prometheus Supercluster: Meta's AI Engine

All of this nuclear power is going to run something: Meta's AI infrastructure.

One specific project getting power from the new nuclear agreements is Prometheus, described as Meta's first supercluster computing system. The term "supercluster" is Meta's term for enormous AI training and inference infrastructure.

Prometheus is expected to come online in New Albany, Ohio, sometime in 2024 or 2025 (the timeline has been unclear). It will contain tens of thousands of AI accelerators (likely GPUs or custom chips) networked together.

A supercluster this size would require hundreds of megawatts of power continuously. It's the kind of power demand that makes nuclear commitments necessary.

Meta is planning multiple superclusters. Prometheus is the first. If the company follows through on its AI ambitions, it will need several more. This is why the 6.6 gigawatt commitment exists—it's scaling to support multiple superclusters.

For context, Google probably has even larger AI training clusters. OpenAI is building massive compute infrastructure. But Meta is making its infrastructure investments very public, treating AI infrastructure as a competitive narrative.

Promethus and future superclusters are where Meta's nuclear power strategy connects to actual product. This is where the investment becomes tangible.

Timeline Reality Check: What's Actually Possible by 2035

Let me be skeptical for a moment, because the industry loves optimistic timelines.

Meta's 6.6 gigawatt target by 2035 is ten years away. In the nuclear industry, ten years is optimistic. Large projects slip. Regulatory approval takes longer than expected. Construction hits obstacles.

What's actually realistic?

Vistra's existing reactors are already operational, so additions or extensions from that partnership could deliver power sooner. By 2030, perhaps 1-2 gigawatts from Vistra.

Terra Power's Natrium reactors are more ambitious. The first commercial plant would be new construction. Even with streamlined permitting, getting from permit to operation probably takes 5-7 years. So a first plant online in 2028-2030, with potential additional capacity by 2035.

Oklo's microreactors are wildcard. They're cutting-edge technology with unproven regulatory pathway. The company is planning a 10-megawatt first deployment soon, but scaling to gigawatt-level capacity requires multiple deployments. This could happen by 2035, but it's one of the riskier bets.

Realistically, Meta probably gets 3-4 gigawatts by 2035, with the possibility of hitting 6.6 if everything goes better than expected. Hitting exactly 6.6 on schedule would require flawless execution across three separate companies with different timelines.

But here's the thing: even delivering 4 gigawatts is historic. It's orders of magnitude more nuclear capacity than any corporation has ever secured. It's enough to power multiple superclusters and establish Meta as a major energy consumer.

The 6.6 gigawatt number is a target, not a guarantee. But it shows ambition and commitment. It signals that Meta is serious about solving the power problem.

What This Means for the AI Industry

We're reaching an inflection point. For the past decade, the limiting factor in AI scaling was compute—how many chips could you afford and how quickly could you get them. The chip market was constrained by supply and cost.

Now, the limiting factor is shifting to power. You can manufacture chips, but can you power them?

This creates a new competitive dynamic. AI companies that secure cheap, reliable, abundant power will win. Companies that don't will hit a ceiling.

Meta's nuclear strategy is a recognition of this reality. By securing long-term nuclear power, Meta is locking in a competitive advantage. The company won't be constrained by energy costs or availability the way competitors relying on grid power might be.

OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and others will likely follow with similar commitments. We'll probably see announcements from multiple companies over the next couple of years.

But there's only so much nuclear capacity available. Not every AI company can build new reactors. This could create a stratification in the AI industry: companies with power and companies without.

The companies with power will be able to build bigger models, train them faster, and run more inference. This translates to better AI products. It translates to capturing more value in the AI market.

Meta's nuclear deal isn't just about energy. It's a strategic move in the AI race.

Estimated data shows that Microsoft leads with the most energy agreements, indicating a strong push towards securing energy resources. Estimated data.

The Supply Chain Challenge: Building the Reactor Economy

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: reactor supply chains are basically nonexistent in the United States.

We haven't built new reactors in decades. The supply chains for reactor components, specialized materials, and skilled labor have atrophied. When you need high-strength reactor pressure vessels, specialized pumps, or expertise in reactor commissioning, you can't just order them off-the-shelf.

Meta's nuclear commitments will require rebuilding these supply chains. Terra Power, Oklo, and others will need to work with manufacturers, train workers, and establish production processes.

This is actually good news for suppliers and manufacturing companies. Heavy equipment manufacturers, specialty materials companies, and engineering firms will see new demand.

But it's also a constraint on how fast reactor deployment can happen. You can't double the speed of reactor construction if the supply chain can't support it. Materials have lead times. Skilled workers need training. Infrastructure needs to be established.

Meta's deal with multiple partners (Vistra, Terra Power, Oklo) hedges this risk. By spreading commitments across companies with different supply chains and timelines, Meta ensures that supply chain constraints on one partner don't block power delivery entirely.

The Geopolitical Implications

Let me zoom out for a second. What Meta is doing has geopolitical consequences.

For decades, the United States declined as a nuclear power. Capacity was mostly aging plants built in the 1970s. Innovation stalled. Policy was defensive. The rest of the world (particularly China and Russia) moved forward.

Now, the convergence of three forces—climate pressure, energy security, and AI demand—is forcing the U. S. to re-engage with nuclear power.

Tech companies are driving this change by providing demand certainty. Meta's deal says: we will buy the power, we will fund construction, we will support this industry.

This creates conditions for U. S. companies (Terra Power, Oklo) to compete globally. It creates export opportunities for American nuclear technology. It positions the U. S. as a leader in advanced nuclear design and deployment.

From a geopolitical perspective, this is strategically important. Countries with advanced AI infrastructure have advantages in AI innovation. Countries with abundant clean power have advantages in hosting data centers. The combination creates strategic dependency: AI leadership requires nuclear capacity.

China understands this. The country is building nuclear plants at record pace, partly to support AI infrastructure and data centers. India is pursuing nuclear expansion. Europe is reconsidering nuclear after years of phase-out plans.

Meta's deal is a signal to the U. S. government and to the world: nuclear power is back. It's not a relic of the past. It's essential to the future.

This will likely drive policy changes—more government funding for advanced nuclear, faster permitting, strategic investment in reactor manufacturing. We may even see nuclear become a trade priority, with the U. S. positioning advanced reactor technology as an export advantage.

Competitors' Responses: The Nuclear Bidding War

Meta made the first big public nuclear commitment, but others won't be far behind.

Google has already announced partnerships with Kairos Power. Amazon is likely negotiating with utilities. Microsoft has mentioned nuclear in its energy strategy.

But there's a constraint: there's only so much nuclear capacity. Not every tech company can sign a power purchase agreement with Terra Power or Oklo. If these companies are allocating capacity to Meta, they have less for others.

This creates a nuclear bidding war. Companies will compete on price, timeline, and capacity commitments. We'll probably see:

- Aggressive corporate commitments: Tech companies putting down large advance payments to secure capacity.

- Government involvement: Countries viewing nuclear capacity as a strategic asset and funding reactor construction.

- New entrant growth: Advanced reactor companies moving from startup to scaleup to major infrastructure providers.

- Consolidation: Smaller nuclear companies getting acquired by larger utilities or energy companies.

Within 5-10 years, the nuclear industry will look radically different from today. It'll be more dynamic, more capital-intensive, and more directly tied to AI infrastructure.

Meta isn't just solving its own power problem. It's catalyzing an entire industry transformation.

Alternatives Meta Considered (and Rejected)

It's worth asking: why nuclear? Why not just build massive solar and wind farms?

Meta probably considered this. The company is aggressive about renewable energy. But there are clear limitations:

Solar and wind are intermittent. AI inference doesn't pause at sunset. You'd need either massive battery storage (expensive and inefficient at data center scale) or overprovisioned renewable capacity with expensive excess during low-demand periods.

Land requirements are enormous. To generate 6.6 gigawatts from solar, you'd need roughly 2,000-3,000 square miles of solar panels (depending on location and sunlight). That's more land than Delaware. Land area is finite and expensive.

Grid integration is complex. Injecting gigawatts of variable renewable power into the grid requires new transmission infrastructure, storage, and demand management. It's possible but takes years and costs billions.

Supply chain is limited. Building that much solar and wind capacity would require tripling current global solar panel production. It's possible over a decade but not faster.

Nuclear avoids these problems. It runs 24/7. It requires minimal land. It doesn't require extensive grid upgrades. The supply chain is constrained, but Meta is helping to expand it.

There's also the environmental argument. Solar panels and wind turbines have manufacturing impacts. They require rare materials, have supply chain emissions, and generate waste at end-of-life. They're clean in operation but have lifecycle impacts.

Nuclear has zero operational emissions, minimal land use, and a concentrated fuel source. For powering data centers at massive scale, it's the most elegant solution.

Meta didn't choose nuclear because it's trendy or because Bill Gates convinced them. They chose it because it's the best technical solution to their power problem.

The Blockchain Irony: Meta's Nuclear Deal vs. Crypto Energy

Here's an interesting contrast worth mentioning.

Meta spent years dealing with backlash over Libra (now Diem), its cryptocurrency project. One major criticism was energy use. Crypto transactions require proof-of-work energy consumption, which seemed wasteful for financial transactions.

Fast forward to 2025, and Meta is securing nuclear power for AI. The energy intensity is comparable to crypto—training and running large AI models consumes similar amounts of electricity per computation.

But the public perception is completely different. Securing nuclear power for AI is seen as strategic and smart. Pursuing crypto was seen as frivolous and wasteful.

The difference is probably that AI has clearer economic and social utility. People use AI products daily. Crypto... well, crypto is still searching for killer applications beyond speculation.

But the irony is worth noting. Both are energy-intensive technologies. Both required rethinking infrastructure. The one that has clear value propositions wins the public relations battle and gets investment.

For Meta, the lesson is probably: focus on technologies with clear utility, and invest in infrastructure to support them. Don't pursue speculative technologies without solving the underlying economic problem first.

Long-Term Implications: 2030-2050

Let's think beyond 2035. What does the nuclear-powered AI future look like?

If Meta succeeds with 6.6 gigawatts by 2035, it will be hosting multiple superclusters training and running massive AI models. Competitors will have done similar deals. The U. S. will have rebuilt significant nuclear capacity.

By 2040-2050, we might see:

Regional AI hubs: Data centers clustered around nuclear plants, taking advantage of cheap power and waste heat recovery. Think of it like how chip fabs cluster around power sources.

Distributed small reactors: Oklo-style microreactors deployed across the country, supporting regional AI infrastructure. This decentralizes power and reduces transmission costs.

AI-specific nuclear plants: Reactors designed and operated specifically for data center power, with waste heat used for other purposes (district heating, industrial processes).

International competition: Countries racing to build nuclear capacity to attract AI infrastructure investment. The global competition for AI dominance becomes a competition for energy.

New nuclear economy: A whole supply chain ecosystem of companies designing, building, maintaining, and decommissioning reactors. This creates jobs, GDP growth, and strategic capabilities.

None of this is guaranteed. Regulatory, technical, or political obstacles could derail progress. But the conditions are now set for this kind of expansion.

Meta's nuclear deal is the opening move in a much larger story about how AI infrastructure gets powered for the next 25 years.

FAQ

What is Meta's nuclear power agreement?

Meta has signed long-term power purchase agreements with three nuclear energy providers: Terra Power (backed by Bill Gates), Oklo (backed by Sam Altman), and Vistra. These agreements commit to delivering 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear power by 2035 to fuel Meta's AI data center operations. Meta is funding the construction of new nuclear reactors as part of these partnerships, with the first reactors potentially coming online as early as 2030.

Why does Meta need nuclear power?

Meta's AI infrastructure, particularly training and running large language models, requires enormous amounts of electricity. A single data center running advanced AI models can consume 100-200 megawatts continuously. Nuclear power provides reliable, 24/7 baseload electricity that solar and wind cannot match due to intermittency issues. Nuclear is also the most land-efficient and carbon-free option at the scale Meta needs.

What is Terra Power and why does Bill Gates back it?

Terra Power is an advanced nuclear company founded in 2006 and backed by Bill Gates. The company develops Natrium reactors, which use molten salt cooling instead of traditional water cooling. These reactors are smaller, generate less waste, and can potentially be built more quickly than conventional reactors. Gates is involved because he believes advanced nuclear is essential to solving climate change and meeting future energy demands.

What is Oklo and Sam Altman's involvement?

Oklo is developing microreactors, which are tiny modular nuclear reactors designed for distributed deployment. Sam Altman is an investor and board member. The microreactors have the advantage of being modular and scalable, and Oklo's design uses spent nuclear fuel from existing reactors as fuel, turning waste into an asset. This appeals to data center operators who want flexible, scalable power solutions.

How much power is 6.6 gigawatts?

Six point six gigawatts of continuous power could supply electricity to roughly 4.8 million homes for a year. To put it in perspective, this is enough to power all of Ireland. This massive capacity reflects Meta's expectation that AI compute infrastructure will be one of the largest electricity consumers in the coming decade.

When will the nuclear reactors actually come online?

Timelines vary by partner. Vistra, an established nuclear operator, might deliver capacity relatively quickly, possibly by 2028-2030. Terra Power's first commercial Natrium reactor is in early construction phases and could come online by late 2030s. Oklo's microreactors have a more uncertain timeline due to regulatory approval requirements for new reactor designs. The 6.6 gigawatt target by 2035 is ambitious and assumes execution across multiple projects with different timelines.

Is nuclear power environmentally friendly?

Nuclear power generation produces zero carbon emissions during operation, making it clean energy for combating climate change. However, the full lifecycle includes energy costs from uranium mining, enrichment, component manufacturing, and transportation. Over a reactor's 60-year operating lifetime, the total carbon footprint amortizes to near-zero per kilowatt-hour, comparable to wind and solar. Nuclear is also the most land-efficient power source, requiring far less area than solar or wind farms to produce equivalent output.

Why not just use solar and wind instead of nuclear?

Solar and wind are intermittent sources that depend on weather conditions. AI data centers operate 24/7 and cannot pause operations when the sun sets or wind stops blowing. You would need massive battery storage systems (expensive and inefficient at data center scale) or massive overprovisioning with waste. Solar farms to generate 6.6 gigawatts would require 2,000-3,000 square miles of panels, more land area than Delaware. Nuclear provides reliable, continuous baseload power from a much smaller footprint.

What does this mean for other tech companies?

Meta's nuclear commitment will likely trigger similar announcements from Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and other tech companies competing in AI. This creates a nuclear capacity competition and may drive a nuclear bidding war as tech companies secure long-term power contracts. Companies with access to cheap, abundant nuclear power will have competitive advantages in building and operating large AI models. This could create stratification in the AI industry based on access to energy infrastructure.

Could these nuclear projects fail or delay?

Yes. Nuclear projects historically face delays and cost overruns. The Vogtle expansion in Georgia took 15 years and costs tripled. Regulatory approval, supply chain constraints, and construction obstacles could push timelines. Advanced reactor projects face additional regulatory uncertainty since they're new designs. Realistically, Meta might deliver 3-4 gigawatts by 2035 rather than the full 6.6, but even this would be a historic commitment to nuclear power.

How does this impact energy policy and geopolitics?

Meta's nuclear investment signals that AI infrastructure will drive massive energy demand going forward. This is likely to influence government policy toward accelerating nuclear permitting, funding advanced reactor development, and treating nuclear capacity as strategically important. Other countries (particularly China) are also building nuclear capacity for AI infrastructure. This makes nuclear power a geopolitical factor in AI competitiveness, potentially making it a trade and strategic priority for the U. S. government.

Conclusion: The Future Runs on Nuclear

When historians look back at 2025, they might identify Meta's nuclear power agreements as a turning point. Not because the deal solves the energy crisis or because nuclear power suddenly becomes ubiquitous. But because it represents the moment when the AI industry stopped treating energy as a commodity problem and started treating it as a strategic asset.

For years, the bottleneck in AI development was compute hardware. How many chips could you build? How fast could you train models? The competition was about technology and engineering excellence.

Now, the bottleneck is shifting. You can build chips. You can engineer models. But can you power them reliably and cheaply? That's becoming the constraint.

Meta's bet on nuclear power—partnering with Terra Power, Oklo, Vistra, and Constellation—is a recognition that solving the power problem is as important as solving the compute problem. The company is willing to invest billions in nuclear infrastructure because it understands that energy access directly translates to competitive advantage.

This commitment will ripple through the tech industry, the nuclear sector, and energy policy. Other companies will follow with similar deals. Supply chains will rebuild. Regulatory frameworks will evolve. Over the next decade, nuclear capacity in the United States will expand more than it has in the previous 30 years.

Will Meta hit exactly 6.6 gigawatts by 2035? Probably not. Large infrastructure projects rarely execute perfectly. But hitting 3-4 gigawatts would still be extraordinary. It would establish Meta as a major nuclear power purchaser and demonstrate that advanced reactors can be built and deployed at scale.

The broader point is this: the future of AI infrastructure is increasingly intertwined with energy infrastructure. Companies that solve the power problem will win. Countries that build nuclear capacity will attract AI development. Technologies that require clean, abundant power will flourish.

Meta's nuclear gambit isn't about environmental virtue signaling or following trendy tech narratives. It's about recognizing a fundamental constraint and investing to overcome it. It's strategic thinking at scale.

We're witnessing the birth of the nuclear-powered AI era. And it started when a social media company decided that powering its supercomputers was worth reshaping the energy industry.

That's not just business. That's infrastructure transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Meta secured 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear power commitments from TerraPower, Oklo, and Vistra to power AI data centers through 2035

- AI model training and inference consume power equivalent to cities, making nuclear baseload electricity essential for scaling infrastructure

- Advanced reactor technologies like TerraPower's Natrium and Oklo's microreactors represent a nuclear industry renaissance after 30 years of stagnation

- Tech companies securing long-term nuclear power will gain competitive advantage in AI race as energy becomes primary infrastructure constraint

- Meta's nuclear investments signal broader industry shift where energy infrastructure is as strategically important as compute hardware for AI dominance

Related Articles

- Samsung AI Chip Boom Drives Record $13.8B Profits [2025]

- DDR5 Memory Prices Could Hit $500 by 2026: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Nvidia's Upfront Payment Policy for H200 Chips in China [2025]

- AI Factories: The Enterprise Foundation for Scale [2025]

- AMD Instinct MI500: CDNA 6 Architecture, HBM4E Memory & 2027 Timeline [2025]

- AI Isn't a Bubble—It's a Technological Shift Like the Internet [2025]

![Meta's Nuclear Energy Deal with TerraPower: The AI Power Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-nuclear-energy-deal-with-terrapower-the-ai-power-cris/image-1-1767985601794.jpg)