Introduction: The Hidden Cost of Blue Destruction

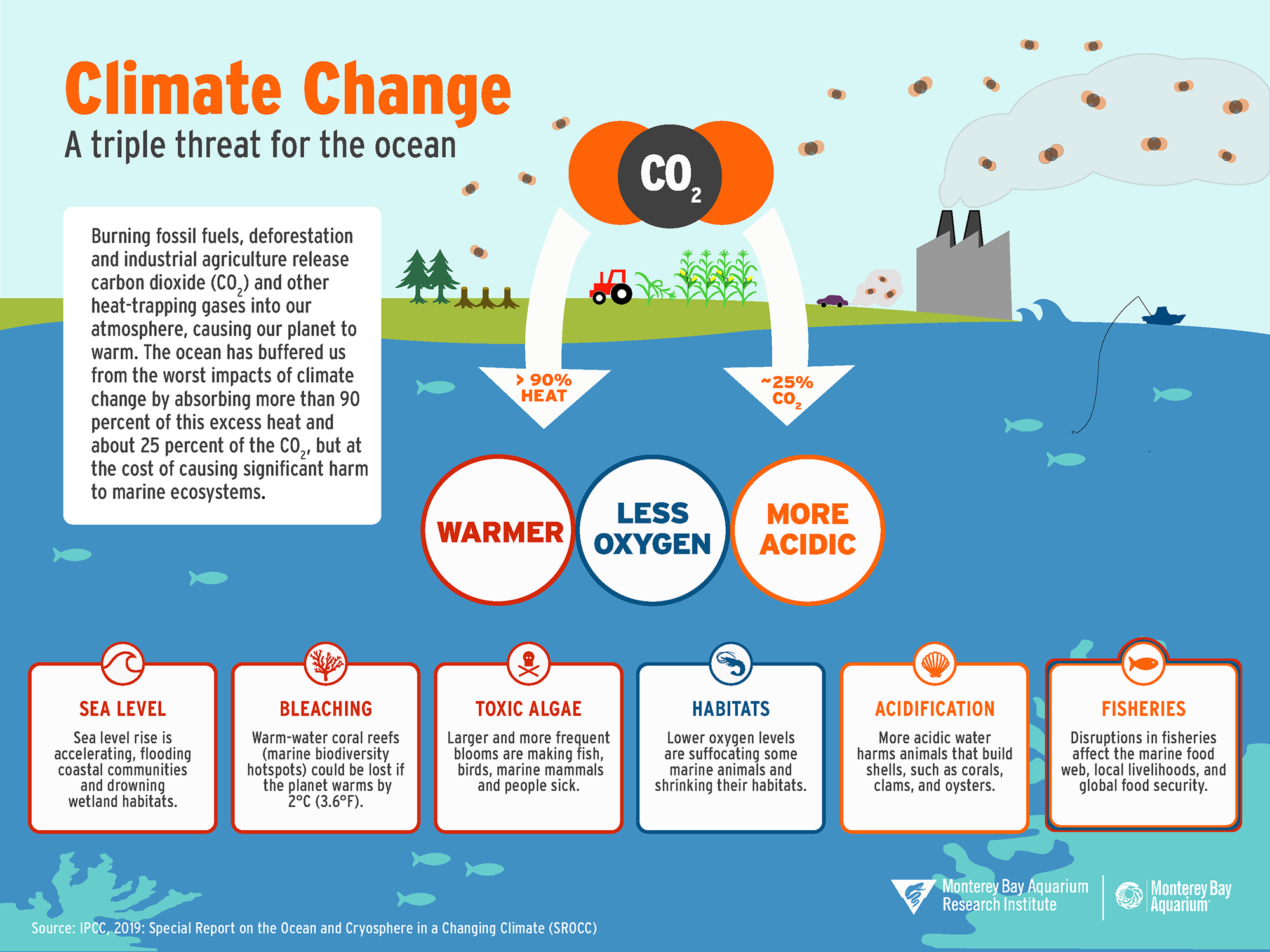

We've been doing the climate math all wrong. For decades, economists and policymakers calculated the price of climate change using a number that was fundamentally incomplete. They'd measure carbon emissions, estimate agricultural losses, factor in infrastructure damage, and arrive at a cost per ton of carbon dioxide. The problem? They left out 70 percent of the planet.

The ocean barely registered in these calculations. It was treated like a free good, something with essentially zero economic value in the climate ledger. That oversight just got exposed as one of the most consequential accounting errors in modern history.

In January 2025, researchers at the University of California, San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography published a study that fundamentally rewrites how we understand climate economics. By including ocean damage in the social cost of carbon calculation, they discovered the true price of our emissions is nearly double what we thought. We're not talking about a minor adjustment. We're talking about roughly $2 trillion in annual ocean-related climate damages when projected forward to 2100.

Let that sink in. That's trillion with a T. Every single year. The gap between what climate economists claimed was the cost of climate change and what it actually costs represents a multi-trillion-dollar blind spot in climate finance, insurance markets, policy analysis, and corporate decision-making.

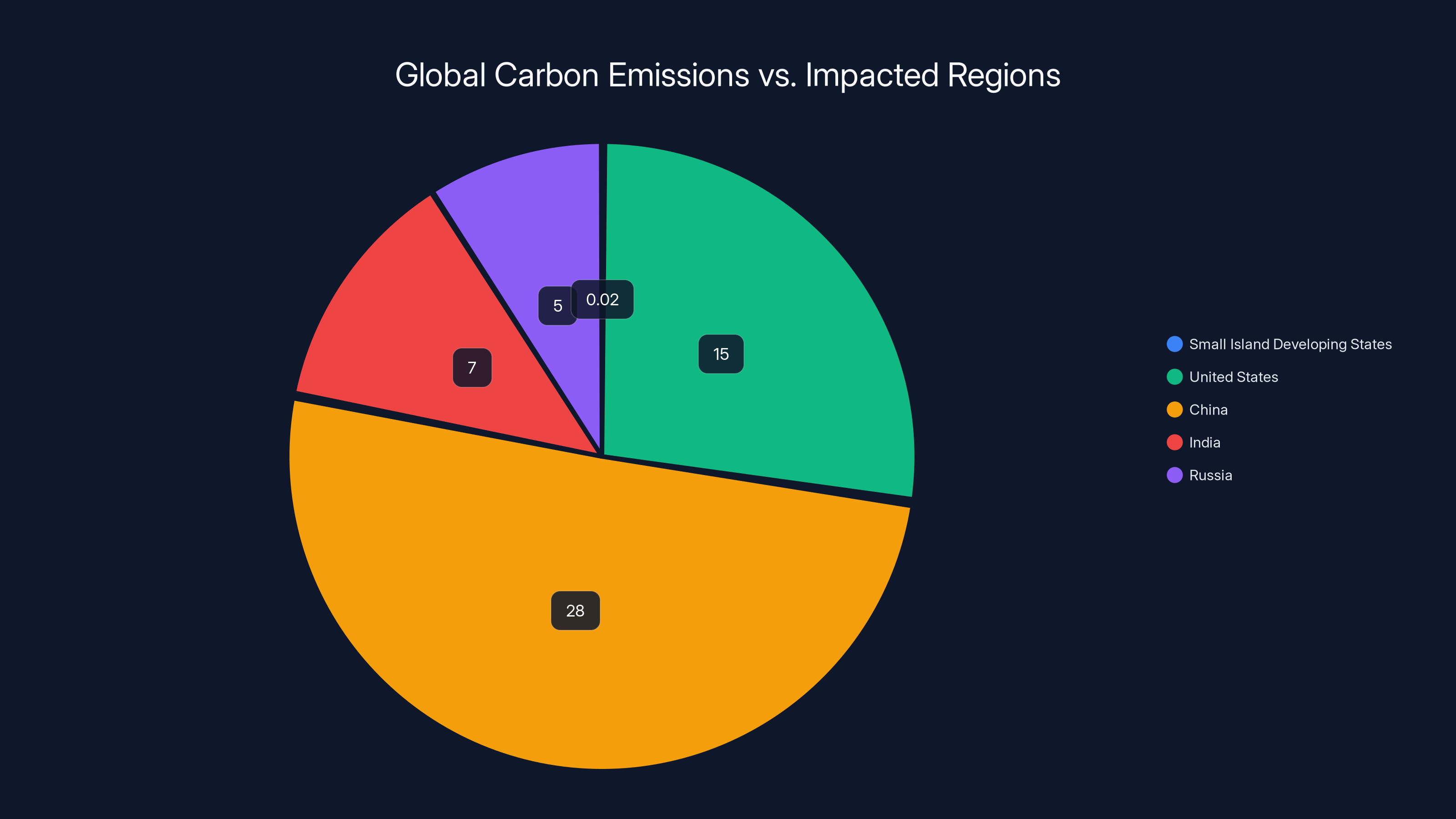

This isn't just an environmental story. It's an economic reckoning. It's a geopolitical one too. Because the countries that emit the most carbon aren't always the ones paying the biggest price. And when you add oceans to the equation, the injustice becomes impossible to ignore. Island nations that contributed almost nothing to the climate crisis face catastrophic losses in fisheries, tourism, and basic food security. That's not a side effect of climate change. That's a core feature of the economic harm.

What's remarkable is how long it took for someone to actually count the ocean. The social cost of carbon has been around for decades. It's one of the most powerful economic tools we have. But it was blind to an entire hemisphere of damage.

TL; DR

- Ocean damages increase global climate costs 91%: The social cost of carbon jumps from 97.20 per ton when ocean impacts are included, fundamentally changing climate economics.

- **2 trillion per year.

- Island economies face disproportionate harm: Nations dependent on ocean resources for food security and economic survival face the steepest costs despite minimal contribution to climate change.

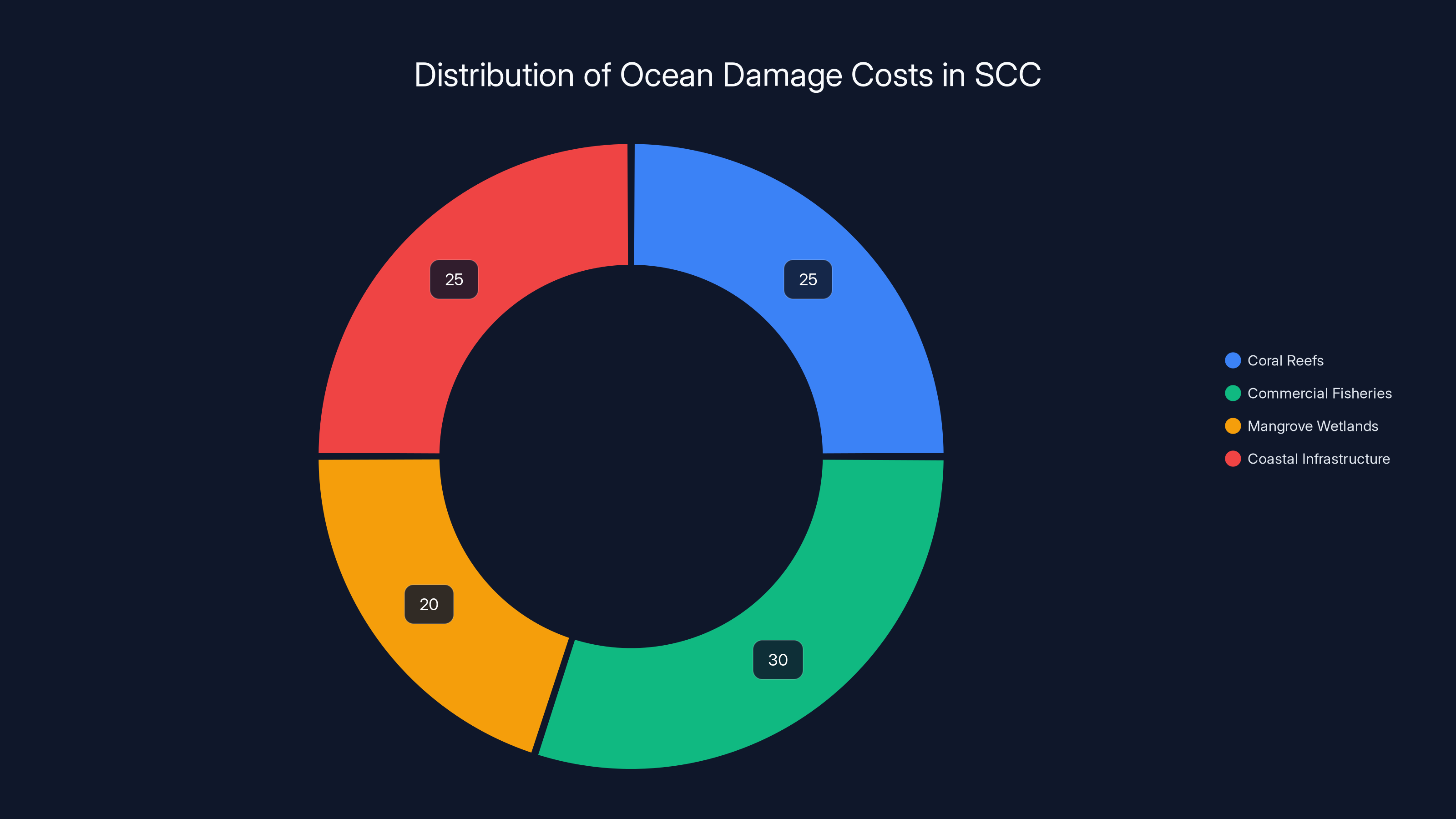

- Multiple sectors affected: The study quantifies damage across four key sectors: coral reefs, mangrove ecosystems, commercial fisheries, and coastal port infrastructure.

- Economic decision-making still ignores ocean: Despite this research, policymakers and federal agencies continue excluding ocean damages from cost-benefit analyses when evaluating climate policy.

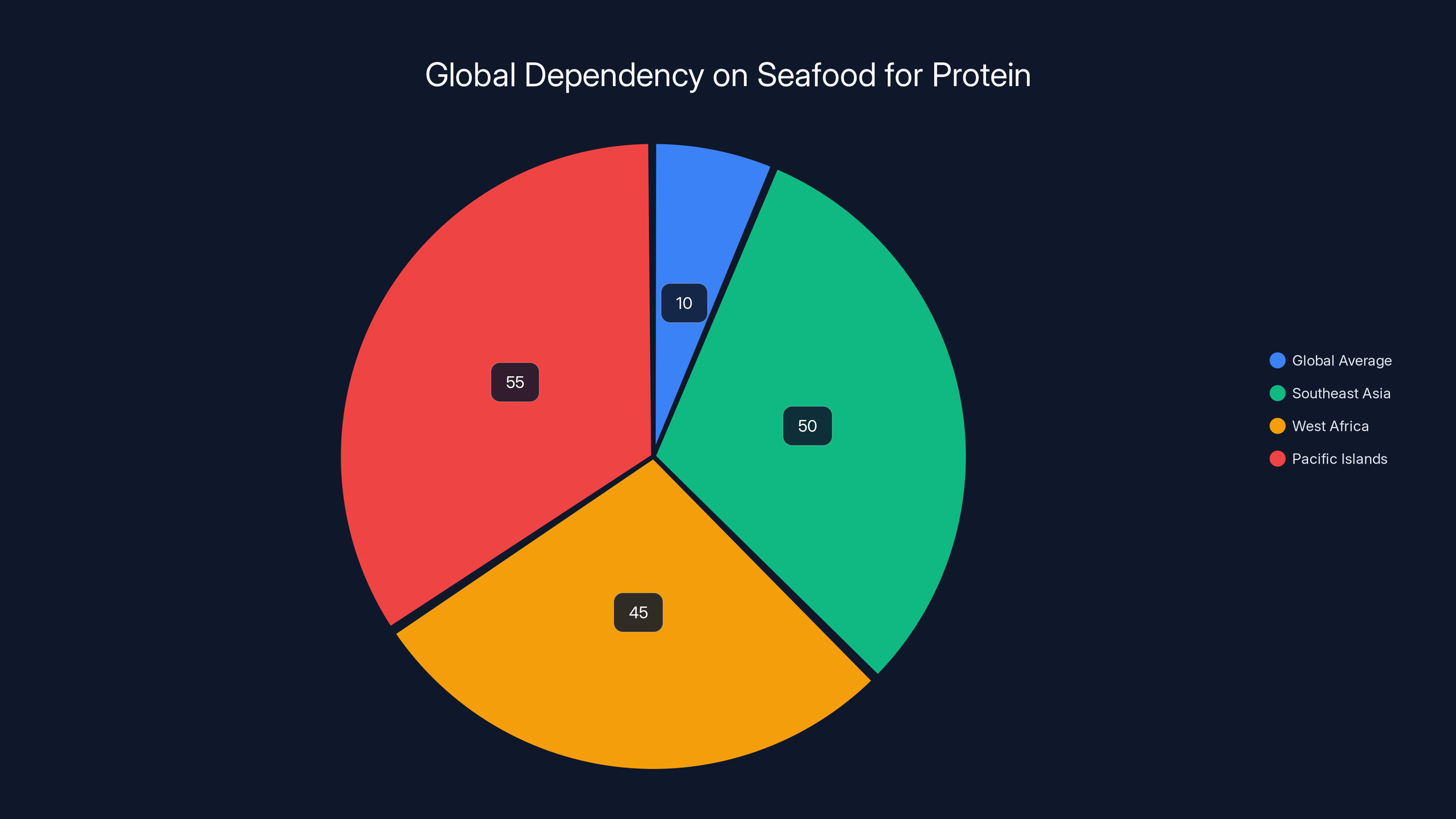

In low-income regions like Southeast Asia, West Africa, and Pacific Islands, seafood provides 40-60% of dietary protein, compared to the global average of 10%. Estimated data.

What Is the Social Cost of Carbon?

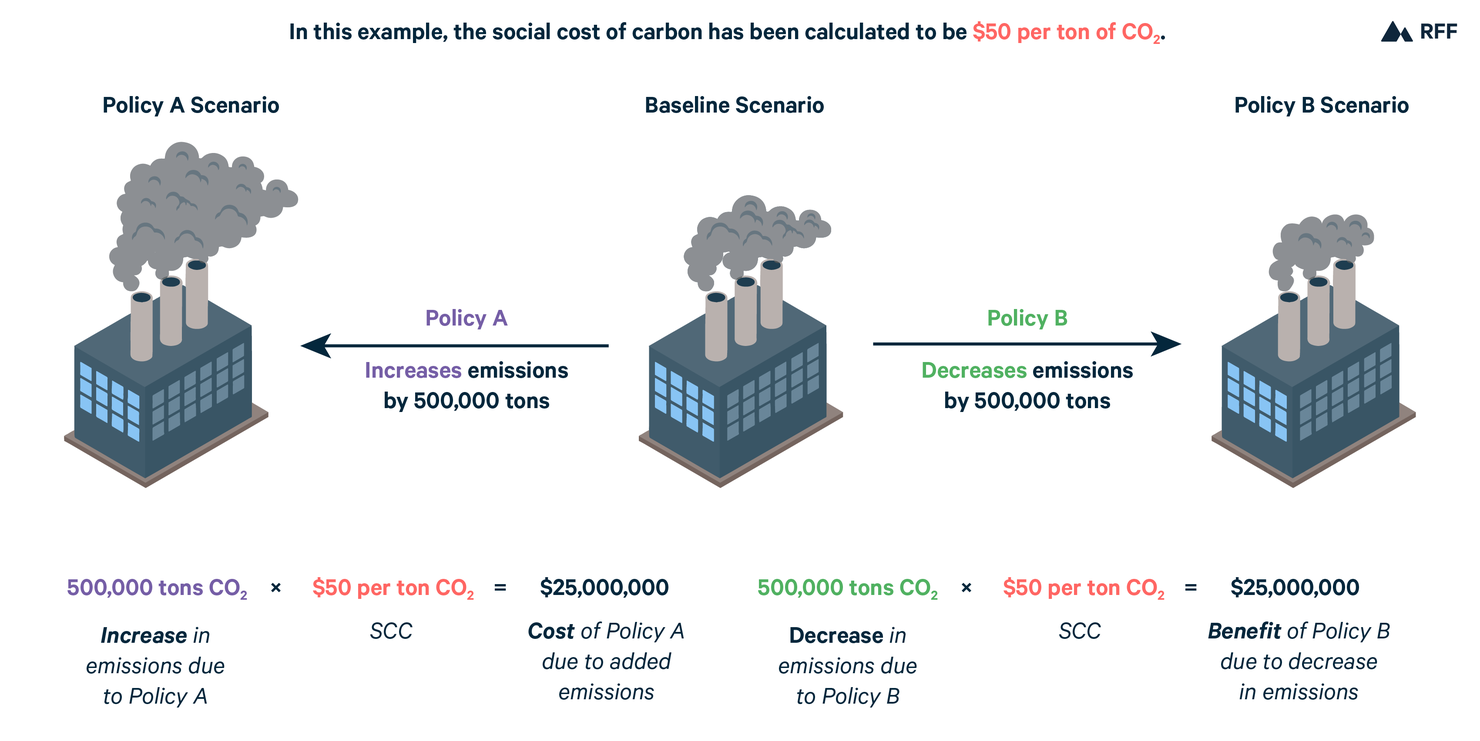

Before we can understand what changed, we need to understand the tool that changed. The social cost of carbon (SCC) is arguably one of the most important economic metrics you've never heard of.

Here's the basic concept: every time someone burns a gallon of gasoline, a factory emits a ton of industrial steam, or a farm runs its equipment, carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere. That carbon dioxide has consequences. It warms the planet. That warming causes damage. The social cost of carbon tries to put a number on that damage per unit of emissions.

It's an actuarial problem. If you know the emission rate, if you can model what warming it causes, if you can estimate the economic harm from that warming, you can theoretically assign a cost to each ton. That cost represents the total economic harm inflicted by that specific unit of carbon.

Why does this matter? Because it affects policy decisions worth trillions of dollars. When the EPA considers whether to tighten pollution standards, they run a cost-benefit analysis. The benefits are calculated using the social cost of carbon. Same thing when governments decide whether to fund renewable energy infrastructure, whether to subsidize electric vehicles, or whether to impose carbon taxes. The SCC is the fulcrum on which these decisions balance.

Think of it like this: if the SCC is low, then carbon is cheap to release. The benefits of avoiding emissions don't justify the costs of prevention. If the SCC is high, then every ton of carbon is expensive, which means aggressive climate action is economically rational.

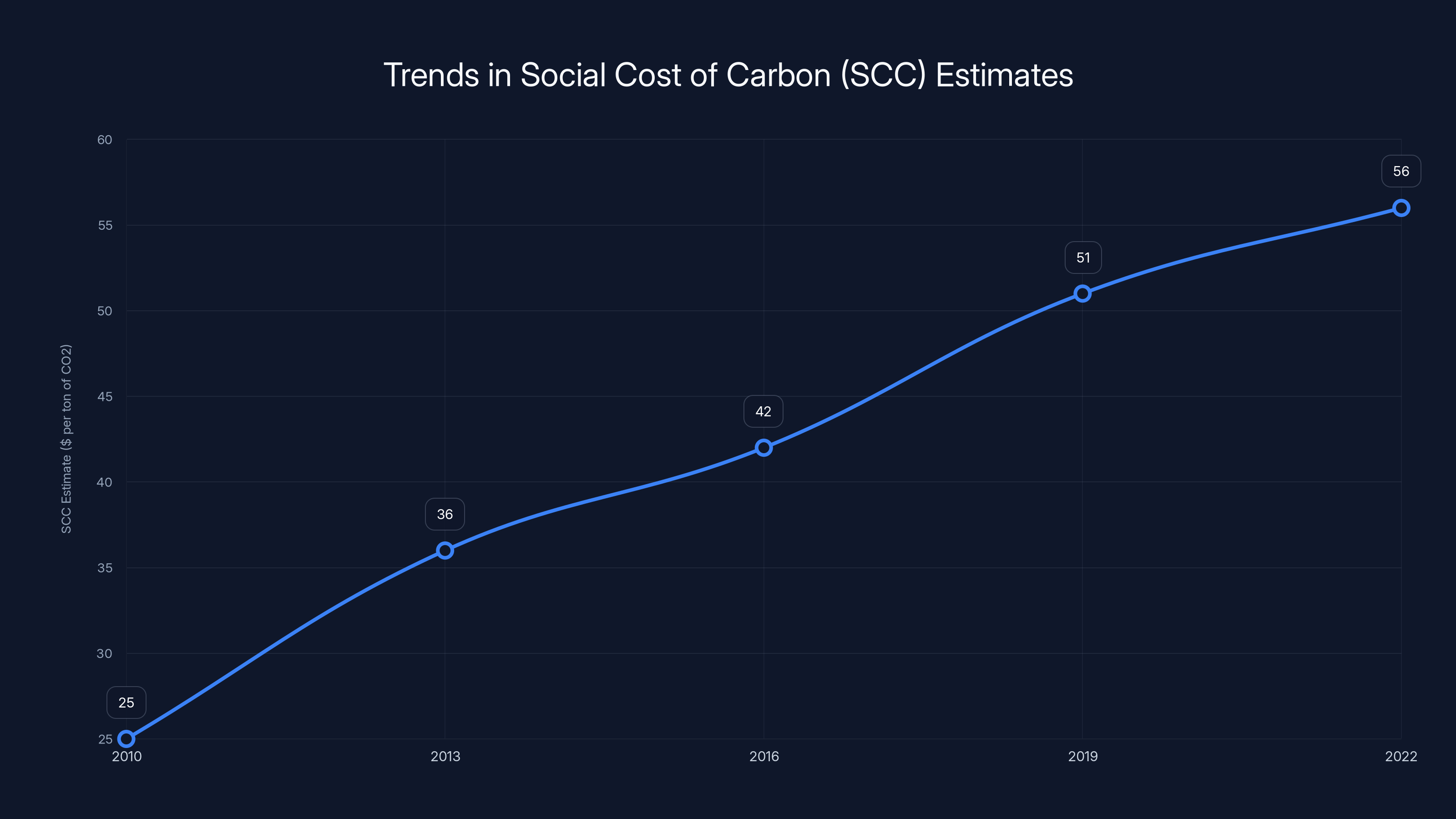

For years, the standard estimate hovered around $51 per ton of CO2. That number has been used in thousands of policy decisions across the U.S. government. The Office of Management and Budget used it. The EPA used it. Federal agencies making decisions about infrastructure, transportation, and energy all relied on it.

But that $51 number was incomplete. It counted climate damages to agriculture, health, and property. It didn't count the ocean.

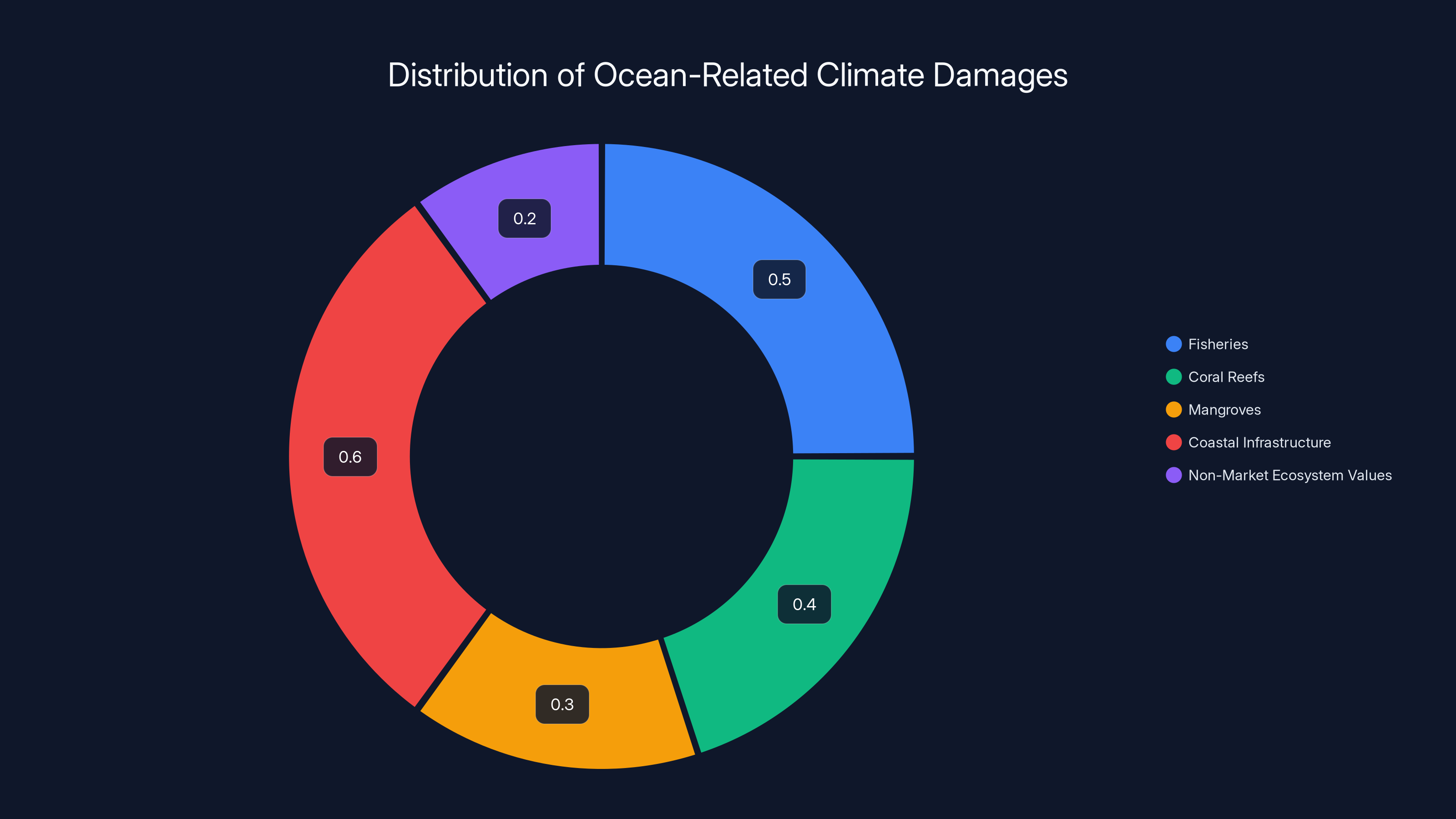

Ocean-related damages are projected to total approximately $2 trillion annually by 2100, with significant contributions from fisheries, coral reefs, mangroves, and coastal infrastructure. Non-market ecosystem values could account for 20-40% of these damages. Estimated data.

How Ocean Damage Was Excluded from Climate Economics

This part of the story is both fascinating and infuriating. The omission of ocean damage wasn't the result of some deliberate conspiracy. It was more like institutional blindness, the kind that happens when a calculation gets set in stone and nobody bothers to question what's missing.

The social cost of carbon framework emerged in the 1990s as climate science became more rigorous. Economists built models that could estimate warming scenarios, predict which regions would be affected, and quantify economic losses. They included agricultural impacts, because farming is easy to measure economically. A yield drops, a price rises, you can calculate the loss.

They included property damage from extreme weather. They included health impacts from heat stress and air pollution. They even tried to include ecosystem losses, though assigning monetary value to ecosystems is notoriously tricky.

But the ocean? The ocean got left out. Partly because ocean systems are complex and hard to model. Partly because commercial fisheries, while significant, don't represent as large a share of GDP as terrestrial agriculture in wealthy countries. Partly because coral reefs are far away and seem less relevant to policymakers in inland nations.

But mostly it was because of a conceptual gap. When economists thought about climate damages, they thought about things you could see from land. Coastal flooding, agricultural collapse, infrastructure destruction. The ocean existed in their models as a background feature, not as an economic system in its own right.

This matters because it meant that policies affecting the ocean got evaluated on an incomplete cost-benefit analysis. If you're deciding whether to approve a new coal plant, and you're calculating whether the climate costs outweigh the economic benefits, you're using a metric that assigns essentially zero value to ocean ecosystem destruction. That plant might warm the ocean by a measurable amount. That warming might devastate fisheries and coral reefs. But in the cost-benefit calculation, it barely registers.

It's like calculating the cost of a car accident but only counting the damage to the vehicle, not the hospital bills.

The Study That Changed Everything: Methodology and Scope

The research that exposed this blind spot wasn't done by a single economist in an office. It was a massive collaborative effort that took nearly five years and involved scientists from multiple disciplines. Bernardo Bastien-Olvera led the team at Scripps, but he brought in fisheries experts, coral reef biologists, marine ecologists, and climate economists. The diversity of disciplines was crucial, because quantifying ocean damage requires understanding systems that operate at very different scales and timescales.

The team started with a fundamental question: what parts of the ocean economy are most vulnerable to climate change? They settled on four key sectors that could be modeled with reasonable confidence.

First, coral reef ecosystems. Coral reefs are among the most productive ecosystems on the planet per square meter. They support fisheries, provide tourism revenue, protect coastlines from storms, and harbor massive biodiversity. When ocean temperatures rise, corals bleach and die. That's not just an environmental loss. It's an economic one. The study estimated coral damage by modeling bleaching events under different warming scenarios, then assigning economic values based on fishing revenue, tourism value, and ecosystem services like coastal protection.

Second, mangrove ecosystems. Mangroves are coastal forest systems that exist in the interface between land and ocean. They're nurseries for commercially important fish species. They provide flood protection. They store carbon. As sea levels rise and temperatures shift, mangrove forests retreat and collapse. The economic losses include lost fisheries productivity and reduced coastal protection.

Third, commercial fisheries. This is the most straightforward to model economically because fisheries already have market prices. As ocean temperatures warm, fish distributions shift. Some species move to deeper or colder water. Fishing communities that have operated in the same areas for generations suddenly find their catches declining. The economic impact is the difference between baseline fishing productivity and projected productivity under various warming scenarios.

Fourth, coastal port infrastructure. Ports are the gateways for global maritime trade. As sea levels rise and storm intensity increases, ports face physical threats. Breakwaters and levees become inadequate. Dredging becomes more frequent. Eventually, ports must relocate or undergo massive upgrades. The study included both direct damage costs and adaptation costs.

For each sector, the team estimated both direct market losses and non-market values. The market losses are easier to calculate. Fewer fish caught equals fewer dollars earned. That's straightforward. Non-market values are harder. These include things like the option value of preserving a coral reef ecosystem for future generations, even if nobody currently fishes it or visits it. There's also what economists call existence value. Most people will never see a deep-sea hydrothermal vent or watch a coral spawning event at full moon. But many care that these things exist. That caring has real economic significance, even if it doesn't show up in a ledger.

The team synthesized global climate models with economic data to create scenarios. They looked at warming trajectories, assessed how each degree of warming would affect fish populations and coral survival rates, translated those impacts into economic terms, and then calculated the social cost of carbon that would be required to account for these damages.

The result: when oceans are included, the social cost of carbon becomes

Small Island Developing States contribute less than 0.02% of global emissions yet face severe impacts, while the top emitters contribute over 50% but experience less existential threats. Estimated data.

The $2 Trillion Figure: Breaking Down Annual Ocean Damages

So where does the $2 trillion number come from? It's a projection, not a current observation. The study uses global carbon emissions predictions and multiplies those emissions by the ocean-adjusted social cost of carbon to estimate total annual damages when projected to 2100.

Let's do the math. In 2024, global CO2 emissions reached approximately 41.6 billion tons. If we multiply that by

But the $2 trillion figure from the study is a projected value for 2100. As emissions continue to rise (at least in the near term), as climate impacts compound, and as infrastructure becomes more vulnerable, the annual damages will increase.

Breaking this down by sector helps illustrate what $2 trillion actually means. The study doesn't assign equal damage to all sectors, because climate impacts are not equally distributed across marine systems.

Fisheries represent the largest component of ocean economic damages. Roughly 10 percent of the world's population depends on seafood as their primary protein source. That's nearly a billion people. Global fishing generates over $200 billion annually in direct economic value, and that doesn't include the value of fish as a food security foundation for many developing nations. When fish populations collapse due to warming, acidification, and oxygen depletion, the consequences ripple through food systems, employment, and nutrition in ways that are difficult to fully quantify.

Coral reef damage is the second major component. Coral reefs provide over $375 billion annually in ecosystem services including fisheries support, tourism, and coastal protection. A warming ocean isn't just bleaching corals. It's eliminating nurseries for juvenile fish, reducing coastal protection against storms, and destroying tourism economies in regions like the Caribbean and Southeast Asia that depend on diving and snorkeling revenue.

Mangrove damage follows similar patterns. Mangroves are even more productive than coral reefs per square meter in terms of fisheries support. When mangrove forests die, you lose both the ecosystem services and the biodiversity they support.

Coastal infrastructure damage includes both direct physical destruction and adaptation costs. Ports need to raise sea walls. Coastal roads need elevation. Some areas become literally uninhabitable, requiring managed retreat and resettlement. The costs accumulate because adaptation is never a one-time event. It's continuous as conditions change.

The Inequality Problem: Who Pays the Price?

Here's where the ocean damage story becomes a global justice issue. The economic harm is not distributed equally. It concentrates in regions that have contributed least to the climate crisis.

Island nations in the Pacific and Caribbean are experiencing the most acute impacts. These countries have populations measured in tens of thousands or low hundreds of thousands. Their economies often consist of fishing, agriculture, and tourism. They have virtually no coal plants, no massive industrial sectors, minimal energy consumption. Yet they face existential threats from rising seas and warming oceans.

Small island developing states collectively contribute less than 0.02 percent of global carbon emissions. Yet they're among the first to experience climate tipping points. Their coral reefs are dying. Their fish stocks are moving away from traditional fishing grounds. Their coastlines are eroding. Some of these nations literally face the prospect of sinking beneath the ocean within a century.

Meanwhile, the major carbon emitters are largely temperate or continental nations. The United States, China, India, and Russia combined produce over 50 percent of global emissions. These countries have diverse economies, inland agriculture, and geographic distribution that provides some buffer against ocean impacts. A warming ocean is certainly a problem for them, but it's not an existential one.

This pattern extends to the global South more broadly. Island nations in Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and the Pacific face disproportionate ocean impacts. Coastal regions in Africa depend heavily on fish protein, but fishing is becoming less productive. South Asia's fisheries support hundreds of millions of people but face severe warming impacts. These regions are simultaneously the most dependent on ocean resources for food security and least responsible for the emissions causing the damage.

Moreover, these regions have the least capacity to adapt. Adaptation is expensive. Raising sea walls, relocating communities, developing alternative food sources, transitioning fishing fleets to new grounds, restoring ecosystems, all of this requires capital. Wealthy nations have that capital. Island nations typically don't.

The result is what climate scientists call climate injustice. The people who caused the problem least are suffering the consequences most. The nations with the greatest historical responsibility for emissions often have the greatest capacity to adapt. The reverse is true for vulnerable nations.

When you quantify ocean damage at $2 trillion annually, that number is not evenly distributed. A disproportionate share of it falls on nations that can least afford it. That's not just a statistical artifact. It's a moral and political reality that shapes climate negotiations, climate finance, and development policy.

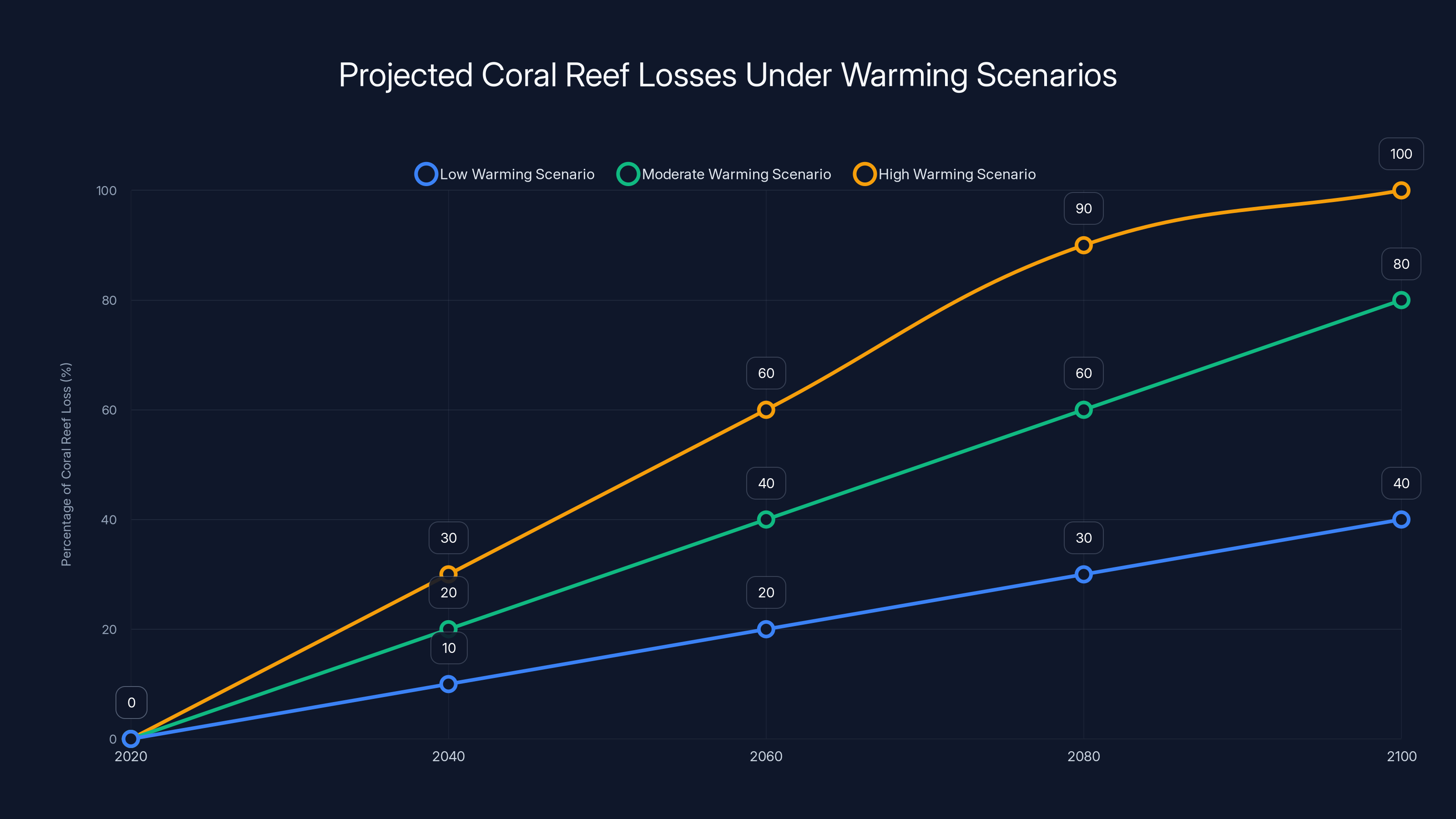

Estimated data shows coral reef losses could reach up to 100% by 2100 under high warming scenarios, highlighting the urgent need for climate action.

Coral Reefs: The Economic Canary in the Ocean

Coral reefs are the first major ecosystem to show how ocean damage translates to economic loss. They're also one of the most economically significant ecosystems per unit area on the planet.

A healthy coral reef generates roughly

But coral reefs are also extremely sensitive to temperature. When water temperature rises above the thermal tolerance of the symbiotic zooxanthellae that live inside coral tissues and provide the coral with nutrients, the coral expels them. Without these symbionts, the coral starves. This is coral bleaching. If temperatures return to normal within a few weeks, the coral can survive. But sustained elevated temperatures lead to death.

We've watched this play out repeatedly over the past two decades. The 1998 El Niño event caused the most severe coral bleaching ever recorded at that time. Nearly 16 percent of the world's coral reefs died. The 2010 coral bleaching event was worse. Then 2016, worse still. And 2023 saw what might be the most severe global coral bleaching event in history, affecting reefs from the Caribbean to the Great Barrier Reef to the reefs of Southeast Asia.

Each bleaching event isn't just an environmental tragedy. It's an economic one. When the Great Barrier Reef experienced severe bleaching in 2016, the impact on Australian tourism alone was estimated at $500 million. But that's just one reef system in one country. When you multiply that effect globally and extend it forward across decades, the numbers become staggering.

The Scripps study didn't just estimate current coral damage. It modeled what coral losses would look like under different warming scenarios through 2100. In moderate warming scenarios, roughly 50 percent of the world's coral reefs are projected to be functionally extinct. In high warming scenarios, the figure approaches 99 percent.

Functionally extinct means the reef still exists structurally, but the ecosystem is broken. The biodiversity collapses. The fish nurseries disappear. The tourism value evaporates. The coastal protection is lost. The ecosystem services are gone. Economically, a functionally extinct reef is nearly as damaging as a reef that's physically destroyed.

What makes coral damage particularly insidious is that it's largely irreversible on human timescales. Unlike some climate impacts that can be adapted to, once a coral reef dies, restoring it takes decades and enormous effort. We're learning to do coral restoration, but the rate at which we can rebuild reefs is orders of magnitude slower than the rate at which we're destroying them.

The economic implication is that coral damage isn't like a stock market crash that eventually recovers. It's more like permanent loss of productive capital. When the Scripps team calculated the value of future coral losses, they had to account for that permanence.

Fisheries Collapse: Protein Security for Billions

Coral reefs are economically significant, but fisheries are economically massive and far more essential for human survival. Over 10 percent of the world's population depends on seafood as the primary source of animal protein. That's roughly 800 million to 1 billion people.

For low-income countries, this dependency is even more pronounced. In Southeast Asia, West Africa, and Pacific island nations, seafood provides 40 to 60 percent of dietary protein. These aren't luxury imports. They're foundational to nutrition, food security, and economic development.

Global fisheries generate over $200 billion in direct economic value annually. When you include indirect effects, processing, distribution, and everything downstream, the total economic value of seafood is substantially larger. But the economic metrics don't fully capture the significance. Fisheries are how millions of people earn livelihoods. They're how communities maintain cultural traditions spanning centuries. They're how fishing-dependent nations maintain autonomy and economic independence.

Climate change threatens all of this through multiple mechanisms. First is direct temperature change. Most commercial fish species have thermal tolerance windows. They thrive in certain temperature ranges and decline outside those ranges. As ocean temperatures warm, species distributions shift. Fish that were abundant in a region for generations move to deeper, colder water or to higher latitudes. A fishing community that has operated successfully in the same location for 200 years suddenly finds the fish are gone.

Second is acidification. The ocean absorbs about 25 percent of the carbon dioxide we emit. When CO2 dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid. The pH of the ocean is declining. This seems like a small number until you understand that the pH scale is logarithmic. A change from pH 8.2 to pH 8.1 represents a 30 percent increase in acidity. For shellfish and mollusks, acidification is catastrophic. Their shells and skeletons become harder to build. Larvae are particularly vulnerable. An acidified ocean can prevent larval development, which disrupts recruitment and leads to population crashes even in adult populations.

Third is oxygen depletion. Warming water holds less dissolved oxygen. Simultaneously, decomposing organic material consumes oxygen faster in warmer water. The result is the expansion of dead zones, regions where oxygen concentrations are so low that most fish cannot survive. These dead zones have grown substantially in recent decades, and they're projected to expand further.

Fourth is disruption of primary productivity. Fish populations depend on lower trophic levels. The base of the food chain is phytoplankton and zooplankton. These are sensitive to temperature, nutrient availability, light, and timing. Climate change alters the seasonal cycles that have synchronized with fish reproduction for millions of years. Spring arrives earlier. Phytoplankton blooms shift in timing. Larval fish hatch and find their food source hasn't yet emerged. The mismatch between predator and prey can cascade through the entire food web.

The Scripps study estimated fisheries losses by modeling how fish populations would respond to warming across the major ocean basins. They found that global fisheries productivity would decline under all warming scenarios, but the decline is not uniform. Tropical fisheries face steeper declines than temperate fisheries, primarily because tropical species are already living near their thermal limits and have less room to adapt.

This has an obvious geographic implication. Low-latitude developing nations depend more heavily on tropical fisheries. They'll face steeper declines in catch. Simultaneously, they have less economic capacity to adapt by moving to different fisheries, importing alternatives, or transitioning workers to new industries.

When you add up the direct losses from reduced catch, the indirect losses from supply chain disruption, the health impacts from reduced protein availability, and the social costs of fishing community collapse, the economic damage from fisheries disruption alone is in the hundreds of billions to low trillions annually when projected to 2100.

The Scripps study included ocean damages in the SCC, with coral reefs, fisheries, mangroves, and infrastructure each contributing significantly to the $97.20 per ton cost. Estimated data.

Mangroves, Wetlands, and Coastal Protection: The Infrastructure Perspective

Most people think of ocean ecosystems as separate from terrestrial economics. But mangrove forests blur that boundary. Mangroves are forest ecosystems that live at the interface between land and ocean, in brackish water and tidal environments.

They're among the most productive ecosystems on the planet. Per square meter, they rival coral reefs in terms of biological productivity. Much of that productivity goes into supporting fish. Mangrove forests are nurseries for juvenile fish of commercially important species. Fish populations that people fish in open ocean often spend their larval and juvenile stages in mangrove nurseries.

Mangroves provide additional ecosystem services beyond fisheries support. They're extraordinary carbon stores. A hectare of mangrove forest can store as much carbon as 15 hectares of terrestrial forest. They provide coastal protection by dissipating wave energy and stabilizing sediments. They filter water, remove excess nutrients, and support biodiversity that's otherwise found nowhere else.

Economically, mangrove loss translates to multiple impacts. First is the loss of fisheries support. When mangroves die, juvenile fish survival declines, leading to reduced populations of adult fish. Second is loss of coastal protection. Without mangrove forests to buffer them, coastal communities face increased flooding, erosion, and storm damage. Third is loss of other ecosystem services including water filtration and carbon storage.

Mangrove loss is already happening. Development pressure, aquaculture expansion, and climate change have already destroyed roughly 35 percent of the world's mangrove forests in the past 50 years. The remaining 35 percent face increasing stress from sea-level rise, changing precipitation patterns, and saltwater intrusion.

As oceans warm and sea levels rise, mangroves experience saltwater inundation of their root systems at higher frequencies. Mangrove adaptation is limited. They can migrate inland if space permits, but in densely developed regions, that space doesn't exist. In many regions, mangroves will effectively be squeezed between rising seas and human development, leading to collapse.

The economic value of mangrove ecosystems has been estimated at roughly $200 billion annually globally, though different studies produce different numbers depending on methodology. What's clear is that the loss is economically significant and concentrated in developing regions that can least afford it.

When the Scripps team included mangrove ecosystem damage in their social cost of carbon calculation, it added a meaningful component to the total ocean damage figure. It also highlighted an often-overlooked aspect of climate economics: the damage isn't just from what we destroy directly. It's from what we fail to maintain and protect. Mangrove forests require certain environmental conditions to survive. Climate change degrades those conditions. The resulting loss is climate damage, even though mangroves aren't being intentionally destroyed.

Coastal Infrastructure: The Adaptation Cost Nobody Wanted to Count

Coral reefs, fisheries, and mangroves are ecosystem damages. But there's also the concrete question of what happens to the infrastructure that human societies built in coastal areas.

Roughly 40 percent of the world's population lives within 100 kilometers of the coast. In developing nations, the figure is even higher. That's roughly 3 billion people with homes, businesses, and infrastructure in proximity to the ocean. Some of that infrastructure is permanent: ports, roads, power plants, housing, farmland.

Rising seas threaten all of it. Storm surge flooding reaches farther inland. High tide floods streets and basements. Saltwater intrusion contaminates aquifers and agricultural land. Erosion removes land, requiring defensive structures. Eventually, people must either abandon the land or retreat inland.

The economic costs include both direct damage and adaptation costs. Direct damage is what you see when a hurricane hits or a flood damages property. Adaptation costs are what you pay to prevent that damage: sea walls, levees, improved drainage, elevated roads, mangrove restoration for wave protection, and managed retreat when adaptation becomes impossible.

Climate economists estimate that the global cost of coastal adaptation alone will be in the hundreds of billions annually by 2050 and could exceed $1 trillion annually by 2100 if we continue current emissions trajectories. That's just the adaptation cost. Add in direct damage from increasingly severe storms and coastal flooding, and the total economic impact is staggering.

The distribution of these costs is globally important. High-latitude developed nations have the economic capacity to build expensive protective infrastructure. The Netherlands has spent centuries engineering protection from rising seas. Japan and Singapore both have advanced coastal protection systems. Australia and the United States can afford elevated roads and improved drainage.

But small island nations and low-lying coastal nations in the developing world often cannot. Bangladesh has 160 million people living in a low-lying delta. Sea-level rise threatens massive areas. The country can build some protection but cannot protect all at-risk areas. Eventually, large-scale population displacement becomes necessary. That's not just an economic problem. It's a humanitarian catastrophe.

The Scripps study included coastal adaptation costs in their ocean damage estimates. This was crucial because it captured not just the environmental damage but the economic burden of response. Adaptation is not free. It's not even cheap. And when it becomes impossible, the costs transform from adaptation costs into displacement costs, lost livelihoods, and human suffering.

What makes this particularly relevant is that adaptation costs scale with warming. A 1.5-degree warming scenario requires a certain amount of adaptation. A 2-degree scenario requires significantly more. A 3-degree scenario requires adaptation that's economically infeasible in many regions. This nonlinear relationship between warming and cost is important when evaluating the economic case for aggressive emissions reductions versus letting warming continue and paying adaptation costs.

The social cost of carbon has increased over the years, reflecting growing awareness and research on climate impacts. Estimated data.

Non-Market Values: When Economics Tries to Quantify the Sacred

Everything discussed so far has an economic market. Fish have prices. Coral reefs have tourism value. Mangroves have fisheries support that generates income. Coastal infrastructure has replacement costs. But there's another category of value that's harder to quantify: non-market value.

People care about oceans for reasons that aren't economic in the traditional sense. They care about coral reefs existing even if they'll never visit one. They care about deep-sea ecosystems even though they'll never see them. They care about species preservation even when those species have no direct economic value. They want to pass a healthy ocean to their children. These values are real. They influence behavior, policy preferences, and moral reasoning. But they don't show up in market prices.

Economists have developed methods to quantify non-market values, though the methods are imperfect. One approach is stated preference studies. Researchers ask people how much they'd be willing to pay to protect a particular ecosystem. Another approach is revealed preference studies. Researchers observe where people travel and what they spend money on, then infer the value they place on certain environments. A third approach is hedonic pricing. Researchers observe that homes with ocean views cost more, and attribute the price difference to the value of the view.

The Scripps team included non-market value in their social cost of carbon calculation. They estimated that the existence value, option value, and bequest value of ocean ecosystems add substantial costs to climate change damages.

How substantial? The research suggests that non-market values might represent 20 to 40 percent of total ocean damages. That's enormous. It means that even if we only cared about market economic effects, we'd be underestimating damages by nearly half.

This creates a philosophical problem for policymakers. How do you include intangible values like existence value in cost-benefit analysis? How do you assign a number to someone's desire for a future generation to experience the natural world? These questions don't have clean answers, but ignoring them entirely is also intellectually dishonest. People clearly value these things. Pretending they have zero economic value is just as arbitrary as any estimate you might make.

The Scripps team's approach was to include multiple valuation approaches and present ranges rather than point estimates. For some ocean systems, the existence value is well-researched. For others, it's more speculative. The team was transparent about this uncertainty.

What's important is that by including non-market value at all, the study elevated an often-ignored aspect of economic decision-making. It recognized that climate damages aren't just about lost GDP and increased costs. They're also about lost opportunities for human flourishing, reduced environmental beauty, and narrowed options for future generations.

The Math Behind the $97.20 Price Tag: From Data to Policy

Understanding how the Scripps team got from their ocean damage estimates to the revised $97.20 social cost of carbon requires understanding how SCC calculations work generally.

The basic formula is:

Where:

- = damages in yearfrom one additional ton of carbon

- = discount rate (how much we value future damages versus present damages)

- The sum is over all time periods from present to 2200 or beyond

The calculation is forward-looking. You estimate how much damage an additional ton of CO2 will cause every year into the future, then sum those damages discounted back to present value. The discount rate is crucial because it determines how much weight future damages receive in the calculation.

For the SCC calculation, the Scripps team took existing climate damage models and added ocean-specific damage modules. They plugged in warming scenarios from climate models. They estimated how each degree of warming would affect coral reefs, fisheries, mangroves, and coastal infrastructure. They assigned economic values to those physical impacts. Then they integrated everything into the SCC framework.

The result was that ocean damages added roughly

The Scripps team presented not a single number but a range. The $97.20 is a reasonable central estimate, but the true number might be lower (if we're overly pessimistic about ocean impacts) or higher (if we're underestimating some effects). The key point is that ocean damages are in the range of tens of dollars per ton, which is a substantial revision to the previous estimate.

What's politically important is that this number is now available for policymakers to use. Whether they will is another question entirely.

Policy Implications: How This Changes Climate Economics

So the SCC is higher than we thought. What does that actually mean for policy?

It means the case for aggressive emissions reductions becomes economically stronger. When you're evaluating whether to invest in renewable energy, the benefits of avoiding emissions are now higher. The break-even point shifts. Technologies that weren't economically justified at a

It means costs of climate inaction are higher than we calculated. The benefits of preventing warming through mitigation are nearly double what we previously estimated. The economic case for climate action gets stronger.

It means policies affecting the ocean should be reconsidered. If you're evaluating a proposal that would affect ocean ecosystems, the climate damages from associated emissions are now higher. That fishing industry subsidy that looked economically rational becomes harder to justify if you're properly accounting for ocean damages from the emissions it induces.

But here's the catch: none of this automatically happens. The SCC is just a number. It's useful for policy evaluation only if policymakers actually use it.

In the United States, the situation is complicated. Federal agencies like the EPA and the Department of Energy use the SCC in regulatory analysis. A higher SCC makes it easier to justify new environmental regulations. But political pressure can override the SCC. The Trump administration in 2025 instructed federal agencies to stop using ocean-inclusive damage estimates in cost-benefit analyses unless required by law. That's a significant policy setback that prevents the higher SCC from changing actual policy decisions.

International climate negotiations might be more responsive. The social cost of carbon is increasingly used in climate finance discussions. A higher SCC strengthens the economic case for climate finance, which is money from developed nations to developing nations to help them adapt to and mitigate climate change. If ocean damages represent $2 trillion annually, the argument for allocating climate finance to ocean-vulnerable nations becomes more compelling.

But again, this depends on whether climate negotiators actually incorporate the research. There's often a lag between scientific understanding and policy implementation. The SCC has been evolving for decades, and policy adoption has been slow and incomplete.

The research is clear on the direction: ocean damages are real, substantial, and previously uncounted. How quickly this gets reflected in policy is a separate question determined by politics, not science.

Global Inequity: Why the Crisis Isn't Shared Equally

The simplest way to understand why ocean damage carries such global significance is to look at who depends on oceans most and who's responsible for climate change least.

Island developing states are the most vulnerable. These nations are often small, geographically isolated, and economically dependent on ocean resources. Their entire economies can be built around fishing and tourism. When warming threatens fish stocks and coral reefs, they face economic collapse. When sea levels rise, they face physical inundation. They're experiencing climate impacts that other nations won't feel for decades, if ever.

Meanwhile, their contribution to global emissions is minuscule. Tuvalu, a nation that faces existential threat from rising seas, contributes approximately 0.00001 percent of global carbon emissions. Kiribati and Marshall Islands are similar. These nations didn't industrialize. They don't have coal plants. They don't have massive manufacturing sectors. Their emissions come from basic living: food preparation, electricity generation, transportation. Yet they're experiencing the most severe consequences.

This is the fundamental injustice of climate change. The distribution of cause doesn't match the distribution of consequence. The nations most responsible for emissions are largely temperate nations that industrialized first: the United States, Europe, Russia, Japan, China. These nations have also developed economic capacity to adapt to climate impacts. They have resources for defensive infrastructure, economic diversification, and technology investment.

Small island states have none of these advantages. They're often post-colonial nations with limited economic development, limited financial resources, and limited political influence. When their coral reefs die, they can't relocate the ecosystem. When fish stocks collapse, they can't import alternatives indefinitely. When sea levels rise, they have nowhere to go.

The Scripps study quantifies this injustice. When you assign dollar values to ocean damages, you discover that the largest damages in absolute terms might be in wealthy nations with significant coastal development. But the damages as a percentage of GDP are catastrophic for small nations, and the damages per capita are staggering.

This has implications for climate finance. If wealthy nations truly accept responsibility for emissions damages, then the economic case for transferring resources from wealthy to vulnerable nations becomes much stronger. A $2 trillion annual damage bill suggests that climate finance should be scaled accordingly. Current climate finance commitments are in the tens of billions annually. That's roughly 1-2 percent of estimated damages. It's clearly insufficient.

The Scripps team was explicit about this. Their hope was that quantifying ocean damages would strengthen the moral and economic argument for climate finance, particularly for island nations and ocean-dependent coastal regions in the developing world.

Whether it will is an open question. Climate finance is politically fraught. Wealthy nations resist transfers that are too large. Developing nations argue that any amount is insufficient given the injustice. The research provides a data point in these negotiations, but data alone doesn't determine outcomes.

The Blue Economy: Recognizing Ocean Value in Economic Systems

Part of why the ocean was excluded from climate economics for so long is that the ocean economy is largely invisible in conventional economic accounting. When economists think about the economy, they think about GDP, which measures market transactions. The ocean provides many services that don't show up in GDP.

Fish swimming in the ocean have no market price. When they're caught and sold, the fish have a price, but the ecosystem service of producing those fish doesn't. A coral reef has no official economic value. The tourism revenue from people visiting reefs is counted in GDP. The reef itself is not. Mangrove forests have no market price. The fisheries they support do.

This creates a systematic bias in economic decision-making. Activities that destroy ecosystem services appear more profitable than they actually are because the cost of destruction isn't captured in prices. A shrimp farm that converts a mangrove forest appears highly profitable on its ledger. The cost of losing the mangrove ecosystem—the lost fisheries productivity, the lost carbon storage, the lost coastal protection—doesn't appear on the farm's balance sheet. From the farm's perspective, the mangrove forest was worth nothing.

The ocean economy, or blue economy as it's increasingly called, is an attempt to correct this bias. It recognizes that the ocean generates economic value through multiple channels: fisheries, tourism, shipping, pharmaceuticals, energy, carbon storage, and others. It's an attempt to assign economic value to ocean ecosystem services so that those services are visible in economic decision-making.

The Scripps study is part of this larger movement toward recognizing ocean value. By incorporating ocean damage into the SCC, they're making ocean ecosystem services visible in the economic framework that governments use for policy evaluation.

This is not a trivial change. If ocean ecosystem services are recognized as economically valuable, then policies that protect oceans become economically rational. A coral reef restoration project isn't just environmental spending. It's investment in productive capital. A fisheries management system that sustains fish populations isn't just conservation. It's protection of a natural asset.

The blue economy framing is gaining traction in development policy, international negotiations, and some national governments. The Caribbean Development Bank, the World Bank, and various UN agencies are increasingly framing ocean protection as economic development. This is important because it potentially shifts ocean protection from the environmental policy silos to the economic development mainstream. Environmental protection is seen as something that costs money. Economic development is seen as something that makes money. If ocean protection is framed as both, it gains political traction.

The Scripps research provides concrete data supporting this reframing. Ocean services are worth nearly $100 per ton of carbon emissions in damages prevented. That's a meaningful economic value.

Implementation Challenges: Making the Science Matter

Having a higher SCC is great from an economic perspective. Actually implementing that higher number in policy decisions is another matter entirely.

First, there's the technical challenge. The SCC is already complicated. It requires climate models, economic models, assumptions about future population and consumption, discount rate choices, and valuations of ecosystem services. Adding ocean-specific damages adds another layer of complexity. Policymakers and economists need to understand where the number comes from and what assumptions drive it. That's hard. Most people don't read economic papers.

Second, there's the political challenge. A higher SCC strengthens the economic case for climate action, which threatens industries and actors who profit from business-as-usual. Coal companies, oil companies, and others with interests in continued fossil fuel use will argue that the ocean damages are overstated, the valuation methods are flawed, or the discount rate is too low. These are not unreasonable objections. They're standard critiques of SCC estimates. But they'll be mobilized to prevent adoption of the higher number.

Third, there's the jurisdiction challenge. The SCC is most directly used by the U.S. federal government in regulatory analysis. But the U.S. is not the only relevant jurisdiction. International bodies, national governments, and subnational jurisdictions all make climate and environmental decisions. Getting all of them to adopt the same higher SCC is a coordination problem.

Fourth, there's the uncertainty challenge. The ocean SCC has wider uncertainty bounds than the terrestrial SCC. Coral reef damage estimates depend on how we model bleaching, which depends on understanding of coral physiology that's still evolving. Fisheries impacts depend on understanding of fish distribution and adaptation that's subject to debate. The teams can bracket the uncertainty with low and high estimates, but it's harder to build policy on ranges than on point estimates.

Despite these challenges, there's reason for optimism. The research has been done. The number is out there. It's scientifically defensible and economically sound. Over time, as climate damages accumulate and become more visible, the political pressure to adopt more accurate damage estimates will increase. The question is whether that happens fast enough to change policy before we lock in additional warming.

The Scripps team was deliberately optimistic about this. They believe that making ocean damages visible in economic terms is a first step toward changing decision-making. They're right that awareness is necessary for change. Whether it's sufficient is less clear.

Future Research Directions: What Else Needs to Be Counted?

The Scripps study is groundbreaking, but it's not the final word on ocean damages. Researchers are already identifying gaps and areas for future work.

One area is Arctic ocean impacts. The study focuses on tropical and temperate oceans, where most human fishing occurs and where coral reefs are found. But the Arctic ocean is changing rapidly. Sea ice is disappearing. Ocean circulation patterns are shifting. Indigenous peoples who depend on Arctic marine resources face severe impacts. But the economic valuation of Arctic impacts is less developed than for tropical systems.

Another area is deep-sea ecosystems. The research focuses on shallow-water systems because those are economically important and relatively well-studied. But deep-sea ecosystems are being affected by warming, acidification, and oxygen depletion. These ecosystems harbor massive biodiversity and may contain compounds of pharmaceutical or industrial value. Understanding their economic value requires new valuation approaches.

A third area is ecosystem tipping points. The research assumes gradual damage from warming. But ocean systems have tipping points. A small amount of additional warming might trigger sudden ecosystem collapse. The economic consequences of tipping points are potentially catastrophic and qualitatively different from gradual damage. Better understanding of tipping point probabilities and implications is crucial.

A fourth area is human migration and conflict. The research quantifies economic damages, but one consequence of ocean damage is forced migration. Small island nations might become uninhabitable, forcing population relocation. Fishing communities will become economically unviable, forcing occupational transition. Mass migration creates political and social stresses. The economic costs of migration and associated conflict are not fully captured in the current analysis.

A fifth area is adaptation feasibility. The research quantifies damages, but some damages are ultimately unadaptable. You can't adapt to coral reef extinction. You can't adapt to small island inundation. You can't adapt an ocean ecosystem to a fundamentally different climate. Understanding which damages are adaptable and which are not is crucial for realistic damage estimation.

These directions point to a broader truth: the Scripps study opens a door rather than closing one. It makes visible what was invisible. But the full scope of ocean damage remains incompletely understood. Future research will likely reveal that ocean damages are even larger than current estimates.

Conclusion: The Ocean's Economic Awakening

For three decades, climate economists assigned a value of zero to the ocean. It wasn't a deliberate choice. It was a blind spot, an institutional artifact of how the field developed. But it had enormous consequences. It meant that policies affecting the ocean were evaluated on fundamentally incomplete information. It meant that the case for climate action was weaker than it should have been. It meant that the injustice of climate change went unquantified.

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography study changes that. By including ocean damages in the social cost of carbon, they've made visible what was invisible. They've quantified the injustice. They've demonstrated that the economic case for climate action is nearly twice as strong as we thought.

The practical implications are significant. A higher SCC makes emissions reduction more economically rational. It strengthens the case for climate finance to vulnerable nations. It suggests that policies harming ocean ecosystems should be reconsidered. But realization of these implications depends on whether policymakers actually use the research.

The political situation is complicated. The Trump administration has instructed federal agencies to ignore ocean damages in cost-benefit analysis. That's a major setback. But policymakers in other jurisdictions and at international levels may be more responsive. The research is published. The data are available. The argument is clear. Over time, the pressure to incorporate ocean damages into decision-making will likely increase.

Beyond the immediate policy implications, the study represents something deeper: a recognition that the ocean matters economically. For centuries, the ocean was treated as a boundary to human economy, not as part of it. The industrial age created economic systems that ignored the ocean's productive capacity, treating it as a waste sink and an inexhaustible resource. Climate change is forcing a reckoning with that assumption.

The ocean isn't a free good. It's not a waste dump with infinite capacity. It's a productive economic system that supports billions of people. Damaging it has costs. Large costs. Costs that are now being quantified and made visible.

For developing nations and island states that depend on oceans, this recognition is long overdue. These nations have known for decades that climate change was an ocean problem. Now the global economy has numbers that might finally make the world listen.

The question now is implementation. Will policymakers use the $97.20 figure in decisions? Will climate finance increase accordingly? Will ocean protection move from environmental silos to economic mainstream? Will the injustice be addressed?

The research provides the framework for yes answers to all these questions. Whether the answers are actually yes depends on factors beyond economics: political will, social pressure, and whether the cumulative damage eventually becomes undeniable. The Scripps study is a beginning, not an ending. It's a wake-up call. What we do with that call is entirely up to us.

FAQ

What is the social cost of carbon?

The social cost of carbon (SCC) is an economic metric that measures the total damages, in dollars, caused by one additional ton of carbon dioxide emissions. It includes damages across sectors like agriculture, health, and infrastructure, and is used by governments to evaluate climate policies and calculate whether emissions reduction efforts are economically justified.

How did the Scripps study change the social cost of carbon calculation?

The Scripps Institution study was the first SCC assessment to include ocean damages. By modeling impacts on coral reefs, fisheries, mangroves, and coastal infrastructure, researchers increased the SCC from

What are the four main sectors of ocean damage included in the study?

The research quantifies damages across coral reef ecosystems, which provide fisheries and tourism value; commercial fisheries that support food security for billions of people; mangrove wetlands that serve as fish nurseries and coastal protection; and coastal port infrastructure threatened by sea-level rise and extreme weather events.

How does ocean damage disproportionately affect developing nations?

Small island developing states and low-lying coastal nations depend heavily on ocean resources for food security and economic development, yet contribute minimally to global emissions. Meanwhile, wealthy nations that caused most emissions have the economic capacity to adapt. This creates a justice issue where those least responsible face the steepest consequences.

Why was ocean damage historically excluded from climate economics?

Ocean ecosystems are complex and difficult to model economically. Additionally, coastal nations that heavily depend on ocean resources were underrepresented in the development of climate economic frameworks, which emerged in wealthy, primarily terrestrial economies. The ocean was treated as economically worthless, a conceptual blind spot that persisted for decades.

What is non-market value and why is it important to climate economics?

Non-market value refers to economic worth that people assign to ecosystems even when they don't directly use them, including existence value (knowing something exists is valuable), bequest value (preserving it for future generations), and option value (maintaining future access). The Scripps study suggests these values represent 20-40 percent of total ocean damages, making them crucial to accurate damage assessment.

How will the higher social cost of carbon affect climate policy?

A higher SCC strengthens the economic case for emissions reduction, makes clean energy investments more justified, and increases the economic value of protecting ocean ecosystems. However, actual policy changes depend on whether government agencies and negotiators incorporate the research into decision-making, which remains politically contested.

What role can climate finance play in addressing ocean damages?

Climate finance from wealthy to developing nations can fund adaptation projects like mangrove restoration, coral reef protection, and fisheries management. The $2 trillion annual ocean damage figure suggests current climate finance commitments are far below what's needed, strengthening the argument for substantial increases in funding.

How do ocean ecosystem services relate to economic development?

The blue economy framework recognizes that ocean-based economic activities like fisheries, tourism, and pharmaceutical development, along with ecosystem services like carbon storage and coastal protection, represent productive economic capital. Protecting oceans becomes not just environmental policy but economic development strategy.

What are the main uncertainties in ocean damage estimates?

Key uncertainties include how coral ecosystems respond to different warming rates, how fish populations will adapt and migrate as oceans change, which ecosystem tipping points may be crossed, feasibility of large-scale adaptation, and the long-term productivity of damaged ecosystems. These uncertainties mean ocean damage estimates have wider ranges than some terrestrial damage estimates, but all evidence points toward substantial damages.

Key Takeaways

- The global cost of climate change nearly doubles when ocean damage is included, rising from 97.20 per ton of carbon dioxide

- Ocean-related damages across fisheries, coral reefs, mangroves, and coastal infrastructure total approximately $2 trillion annually when projected to 2100

- Small island nations and developing coastal regions face the steepest ocean-related climate impacts despite contributing minimally to global emissions

- Non-market ecosystem values representing existence, bequest, and option value could account for 20-40% of total ocean damages

- Current climate finance commitments of tens of billions annually are insufficient relative to estimated ocean damages of trillions

- Incorporating ocean damages into economic decision-making requires both scientific evidence (now available) and political will (still lacking in many jurisdictions)

- Future research directions include Arctic impacts, deep-sea ecosystems, tipping point probabilities, human migration costs, and adaptation feasibility analysis

Related Articles

- Best Water Leak Detectors [2026]: Complete Guide & Reviews

- Why Online Car Buying Still Isn't Happening [2025]

- Jones Hovercraft 2.0 Snowboard Review: Ultimate Powder & Freeride [2025]

- Best Juicers 2025: Cold Press vs Masticating vs Centrifugal [Guide]

- How 4K Blu-ray Transforms Classic Films: A Technical Deep Dive [2025]

- Responsible AI in 2026: The Business Blueprint for Trustworthy Innovation [2025]

![Ocean Damage Doubles Climate Change Costs: The $2 Trillion Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ocean-damage-doubles-climate-change-costs-the-2-trillion-cri/image-1-1768739820002.jpg)