Introduction: A Planet Out of Balance

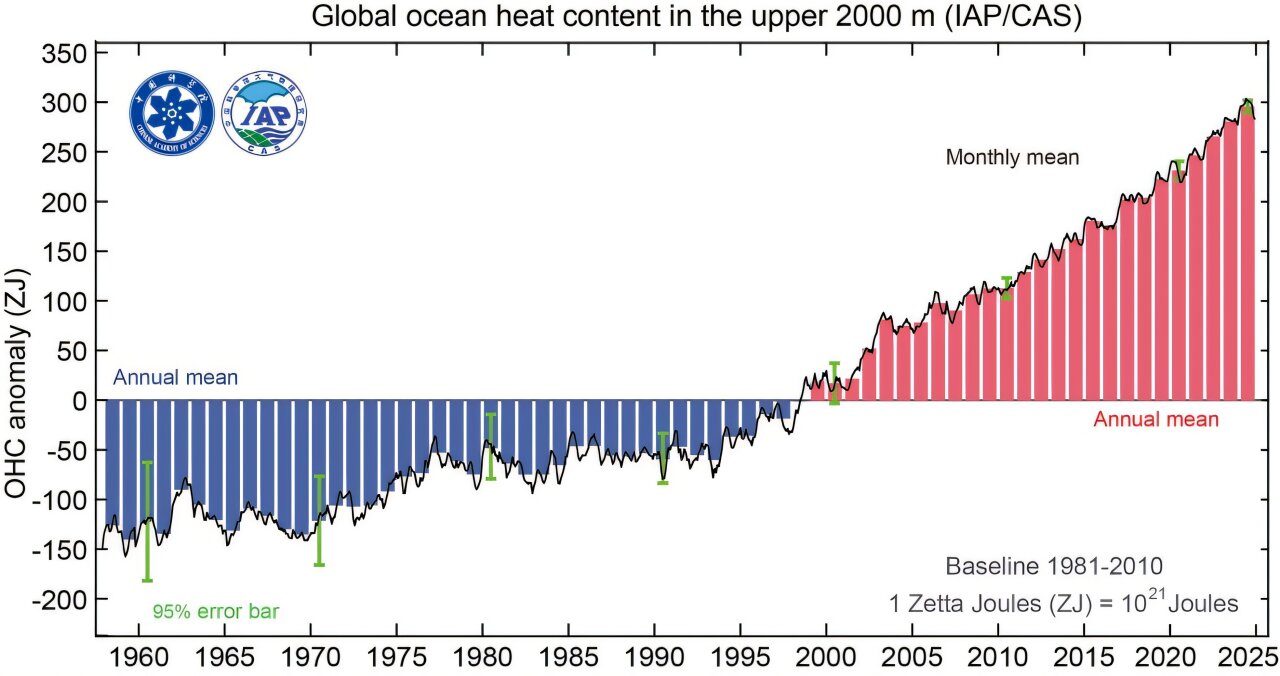

Imagine if someone told you that the world's oceans just absorbed enough energy to simultaneously boil 2 billion Olympic swimming pools. That's not hyperbole or a worst-case scenario buried in climate models. That's what actually happened in 2025, as reported by Scientific American.

For the eighth year running, ocean temperatures hit a new record. And not by a little bit. The amount of heat absorbed jumped dramatically from the previous year. We're not talking about surface-level warming that makes a nice beach day slightly hotter. We're talking about the deep ocean, the massive thermal sink that holds more than 90 percent of all excess heat trapped on our planet, according to Britannica.

This pattern matters in ways that go far beyond water temperature statistics. Ocean heat isn't just an environmental issue—it's the foundational metric for understanding whether climate change is actually accelerating or stabilizing. And right now, every single year of data is screaming that things are getting worse, not better, as highlighted by AOL.

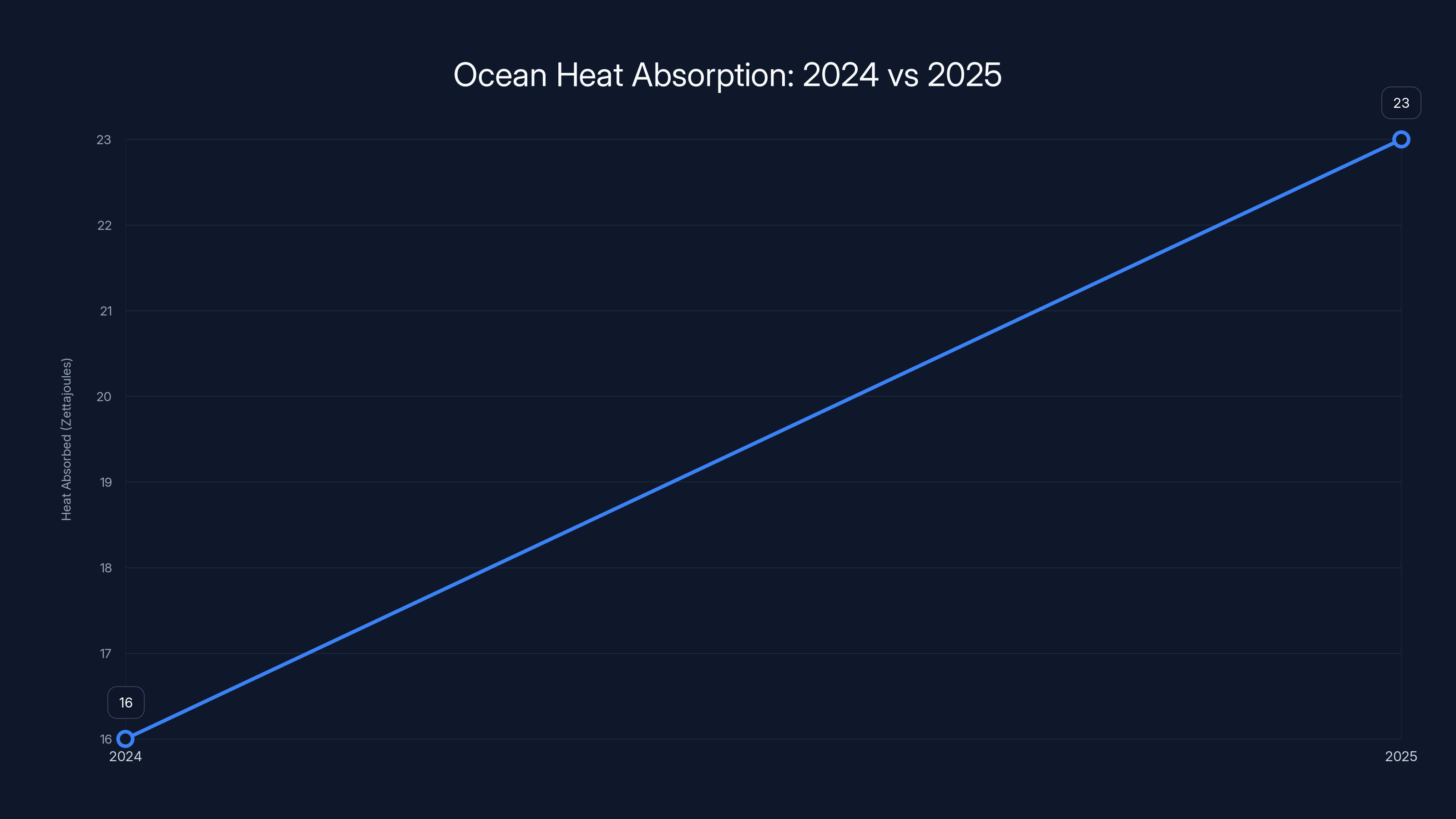

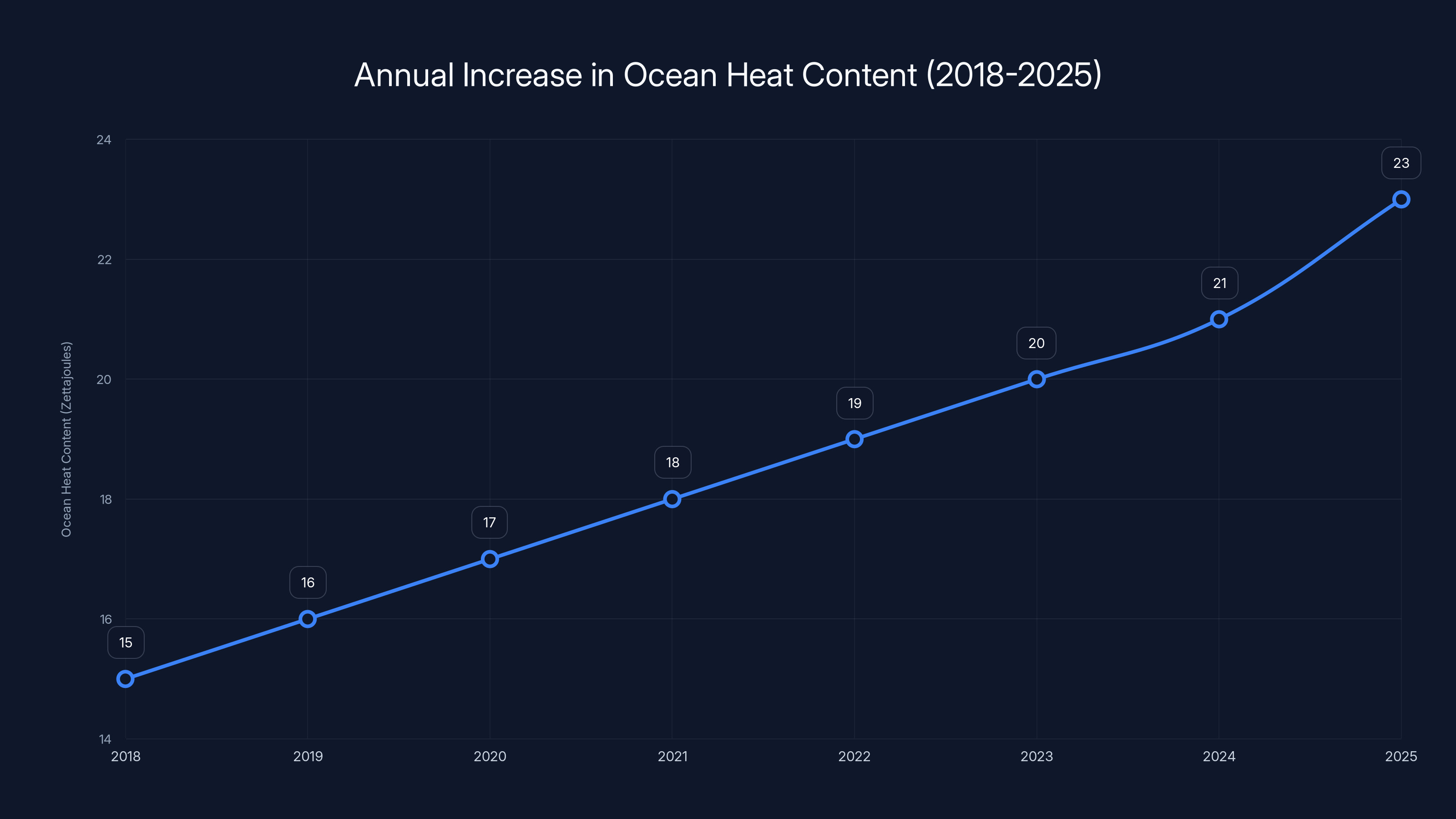

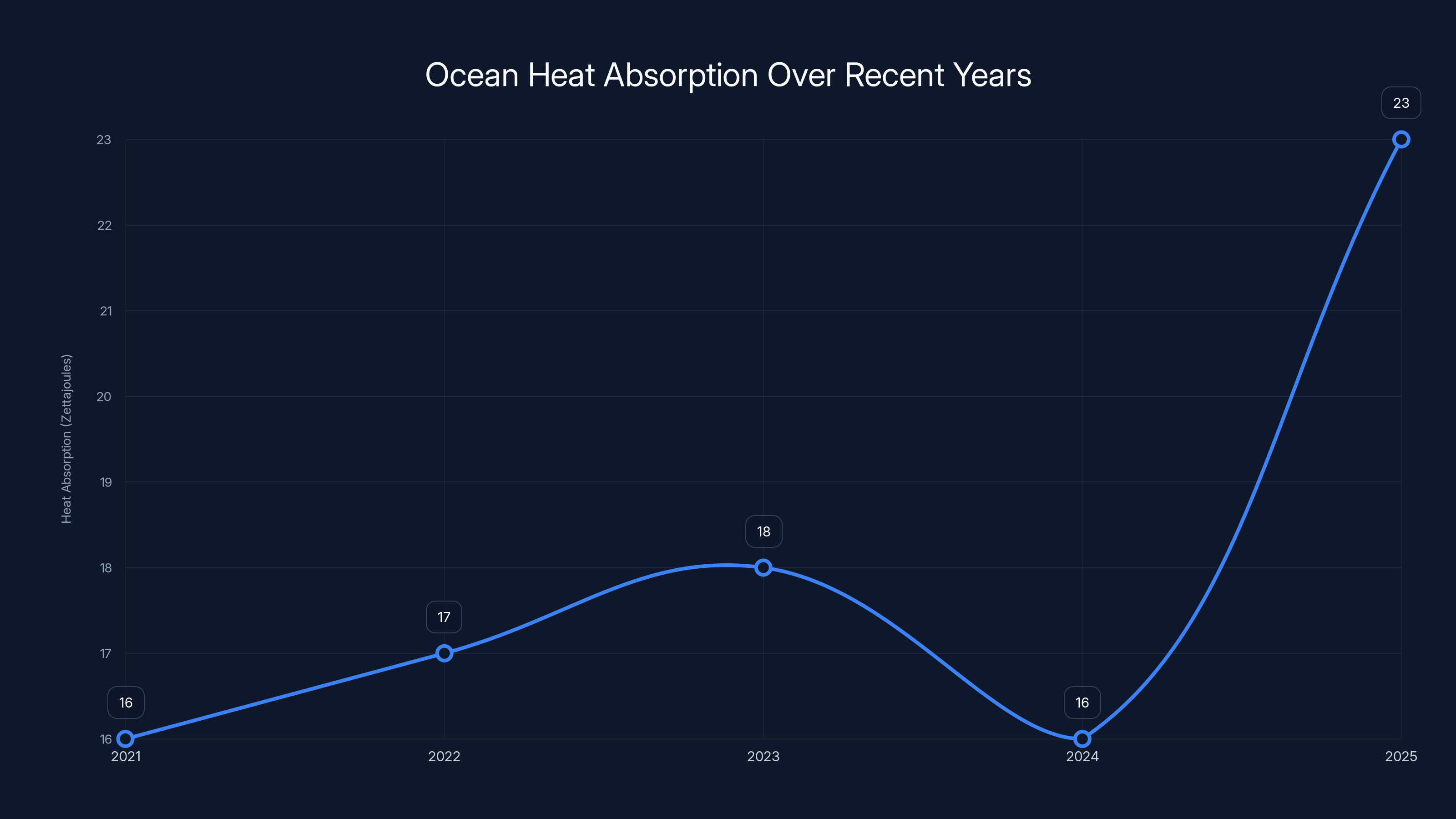

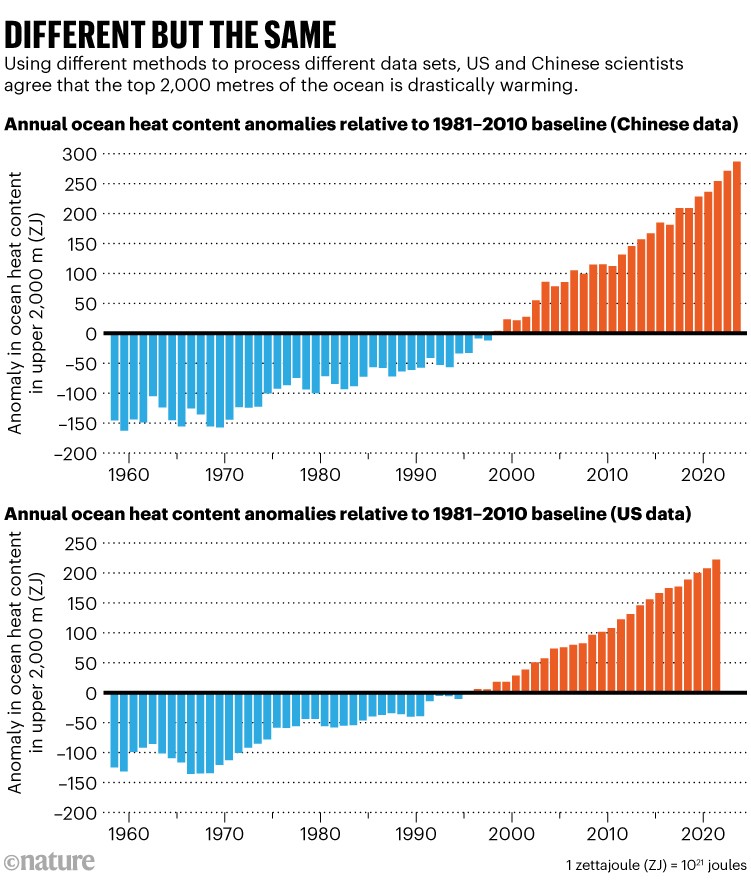

The research comes from over 50 scientists across the United States, Europe, and China who study ocean heat content using multiple independent datasets. They published their findings in Advances in Atmospheric Science, and the numbers are impossible to ignore. In 2025, the world's oceans absorbed 23 zettajoules of additional heat. That's 23 followed by 21 zeros. For context, that's 43 percent more heat than they absorbed in 2024.

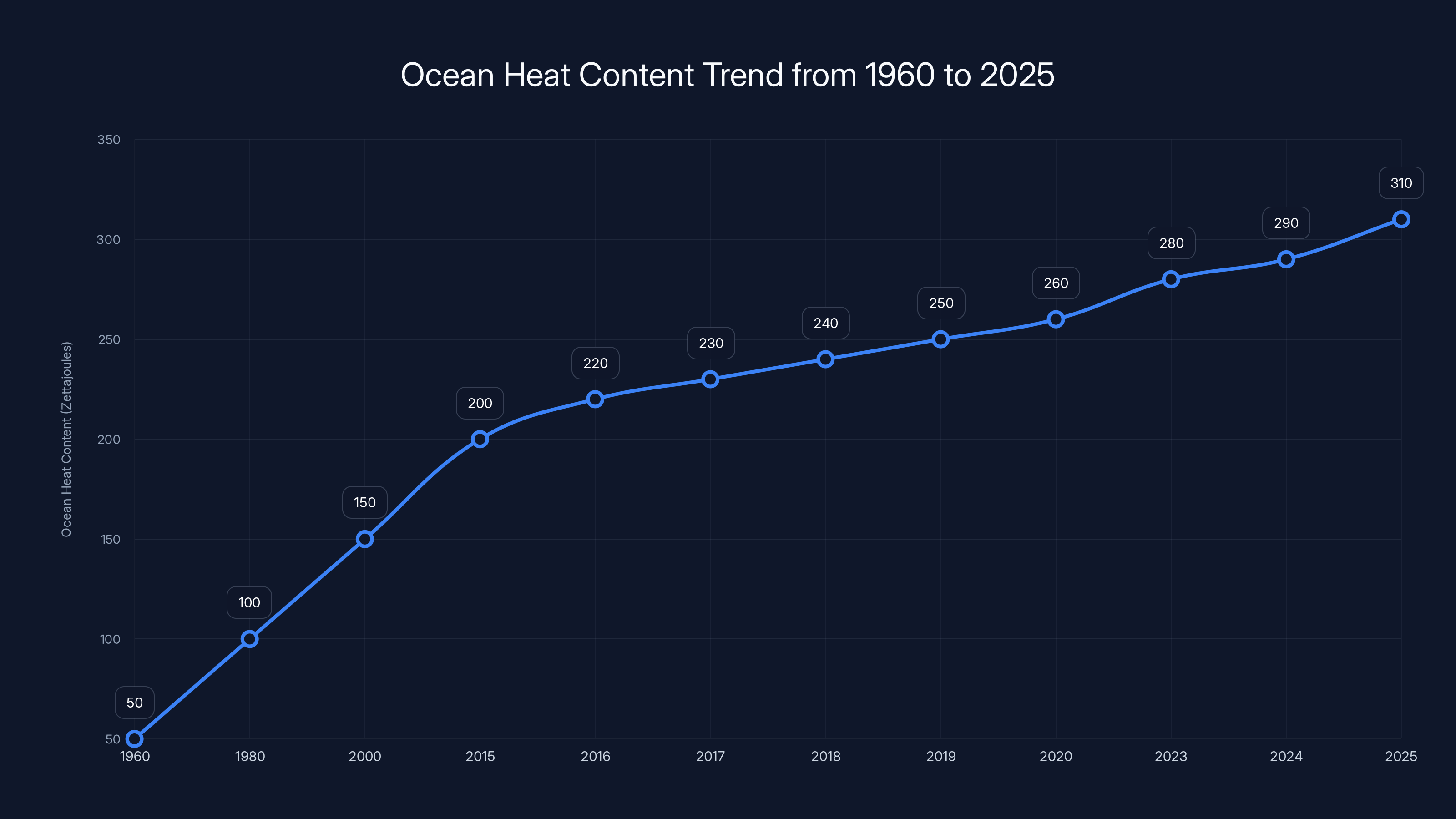

Here's what makes this genuinely scary: we've known about this problem for decades. Scientists have been measuring ocean temperatures seriously since the 1960s. The warming didn't sneak up on anyone. But the acceleration keeps shocking people anyway. Each year, researchers brace themselves for record-breaking data, and each year, the records are more extreme than the last time they predicted them, as noted by Mirage News.

The oceans are our planet's largest heat sink, and they're filling up fast. Understanding what's happening down there—beneath the waves where most people never look—is the key to grasping whether we're actually facing a climate crisis or just experiencing normal variability. Spoiler alert: it's the former.

TL; DR

- Record-Breaking Eighth Year: Oceans absorbed 23 zettajoules of heat in 2025, the most since modern measurements began in the 1960s

- Dramatic Jump: 2025 saw a 43% increase in ocean heat absorption compared to 2024, equivalent to 12 Hiroshima bombs worth of energy

- Deep Ocean Matters: Most heat goes into deep ocean layers, not surface temperatures, making ocean heat content the most reliable climate indicator

- Decades of Data: Multiple independent research teams using Argo floats, satellites, and marine animal sensors all confirm consistent warming patterns

- Human Impact Clear: Fossil fuel use since the industrial revolution has fundamentally altered ocean temperature patterns and marine ecosystems

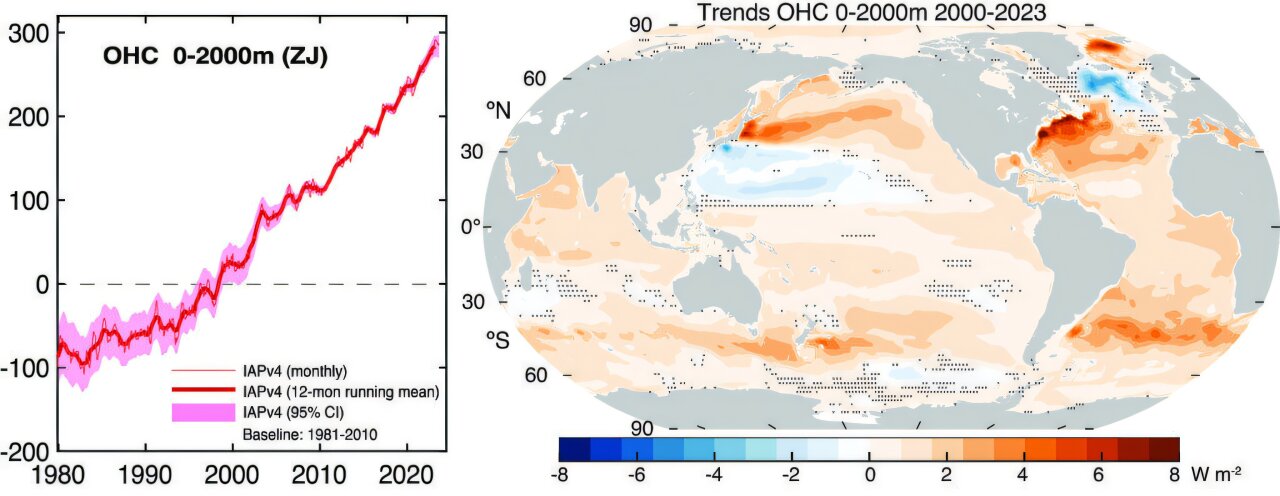

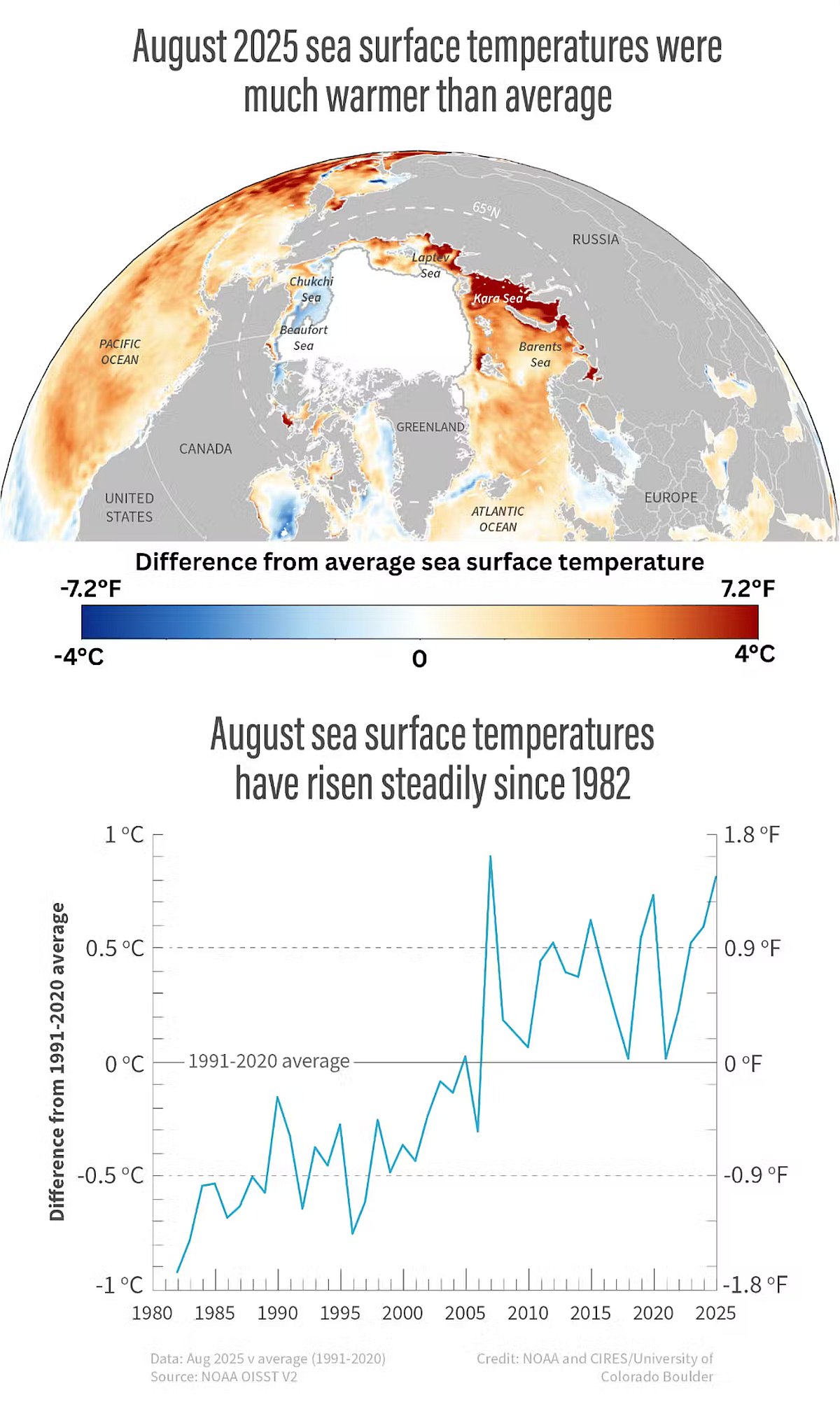

The trend line shows a significant increase in ocean heat content from 1960 to 2025, with a notable acceleration in recent years. Estimated data highlights the largest single-year increase from 2024 to 2025.

What Happened in 2025: The Year Records Broke Again

The numbers landed like a punch to the gut for climate scientists. In 2025, the world's oceans absorbed an additional 23 zettajoules of heat. This wasn't a surprise—scientists had been predicting acceleration for years. But the magnitude still shocked most people paying attention, as detailed by The Invading Sea.

To understand why this matters, you need to grasp what a zettajoule actually represents. A joule is how scientists measure energy. A single joule powers a lightbulb for roughly one second or slightly warms a gram of water. A zettajoule is one sextillion joules. The sheer scale makes it almost impossible to conceptualize without analogies.

John Abraham, a thermal science professor at the University of St. Thomas and one of the study's lead authors, spends a lot of time explaining this to journalists, policymakers, and concerned citizens. His favorite analogy is comparing the energy to atomic weapons. The 23 zettajoules absorbed in 2025 equals the energy released by 12 Hiroshima bombs, all detonating simultaneously in the ocean. His alternative comparisons are equally staggering: the energy required to boil 2 billion Olympic swimming pools, or more than 200 times the entire electrical consumption of every human on the planet.

When Abraham talks about 2025, he doesn't use academic language. He calls it a "bonkers, crazy warming year." In peer-reviewed science, he notes with a hint of dark humor, this actually is the technical term.

The increase from 2024 to 2025 was particularly dramatic. In 2024, the oceans absorbed 16 additional zettajoules. In 2025, that number jumped to 23. That's a 44 percent increase in a single year. For people tracking climate data, this isn't just another data point on a curve. It's evidence that the system is destabilizing in real time.

What makes this especially significant is that 2025 developed a weak La Niña event at the end of the year. La Niña typically reduces the amount of heat the ocean absorbs in a given year because it creates cooler sea surface temperatures in certain regions. Despite this natural cooling phenomenon working against higher heat absorption, the oceans still set a record. The fact that natural variability couldn't slow the warming trend shows how overwhelmingly powerful the underlying human-caused warming signal has become, as reported by Wired.

In 2025, oceans absorbed 23 zettajoules of heat, a 44% increase from 2024's 16 zettajoules, highlighting a significant acceleration in ocean warming.

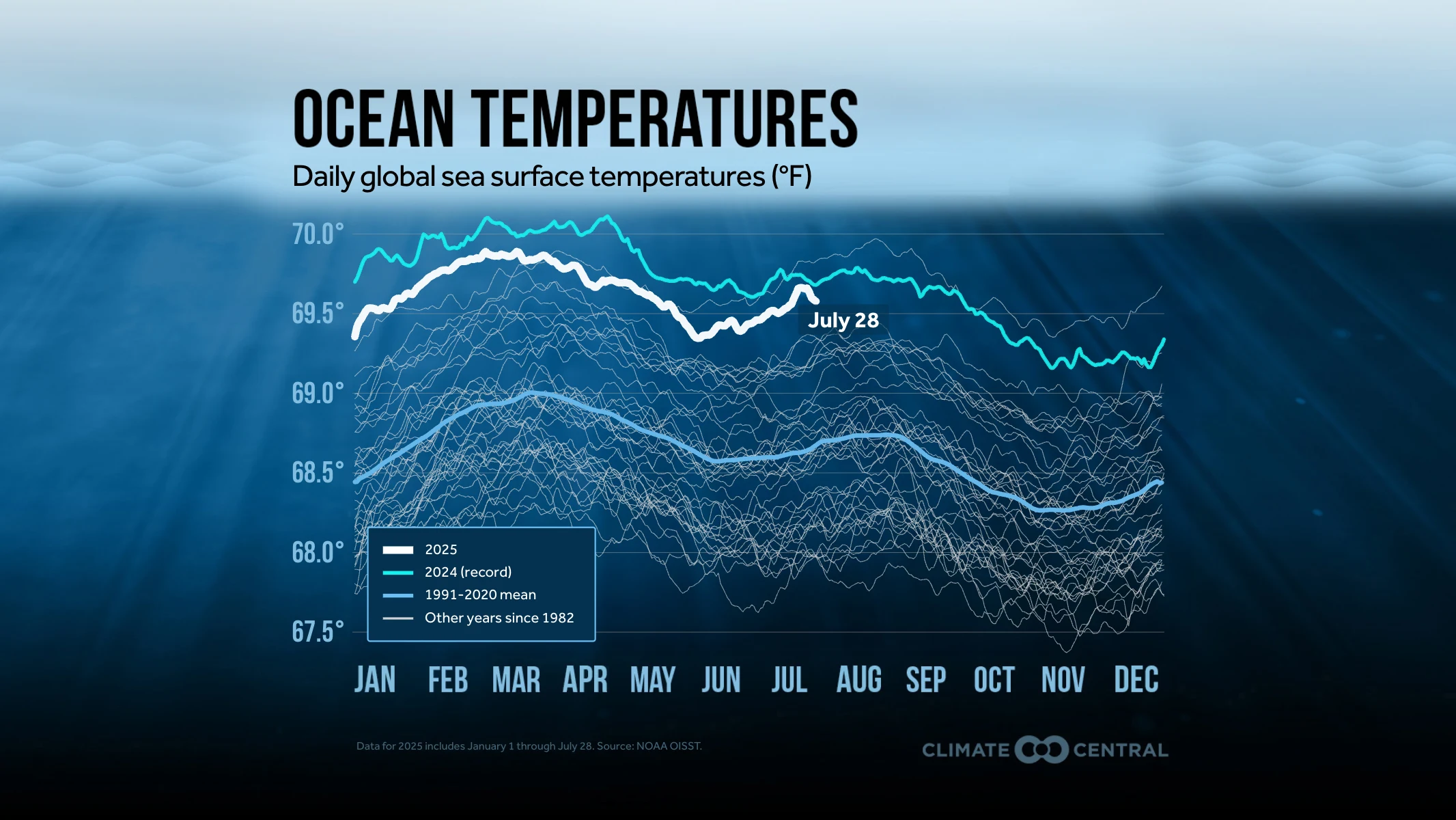

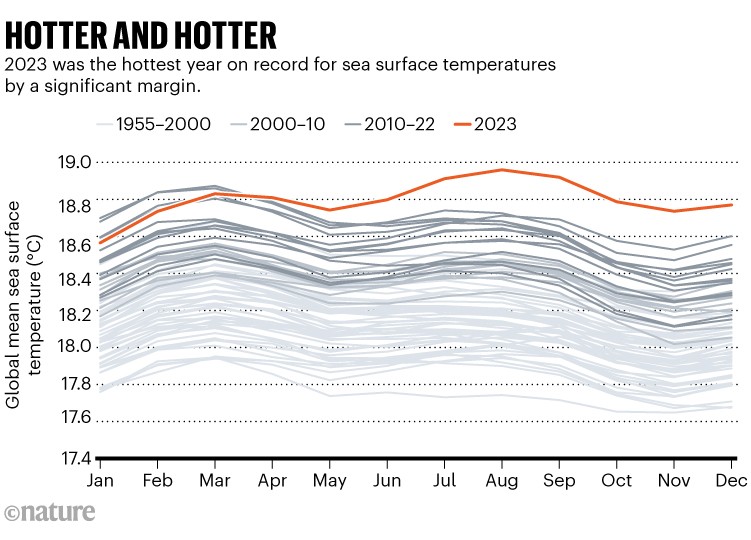

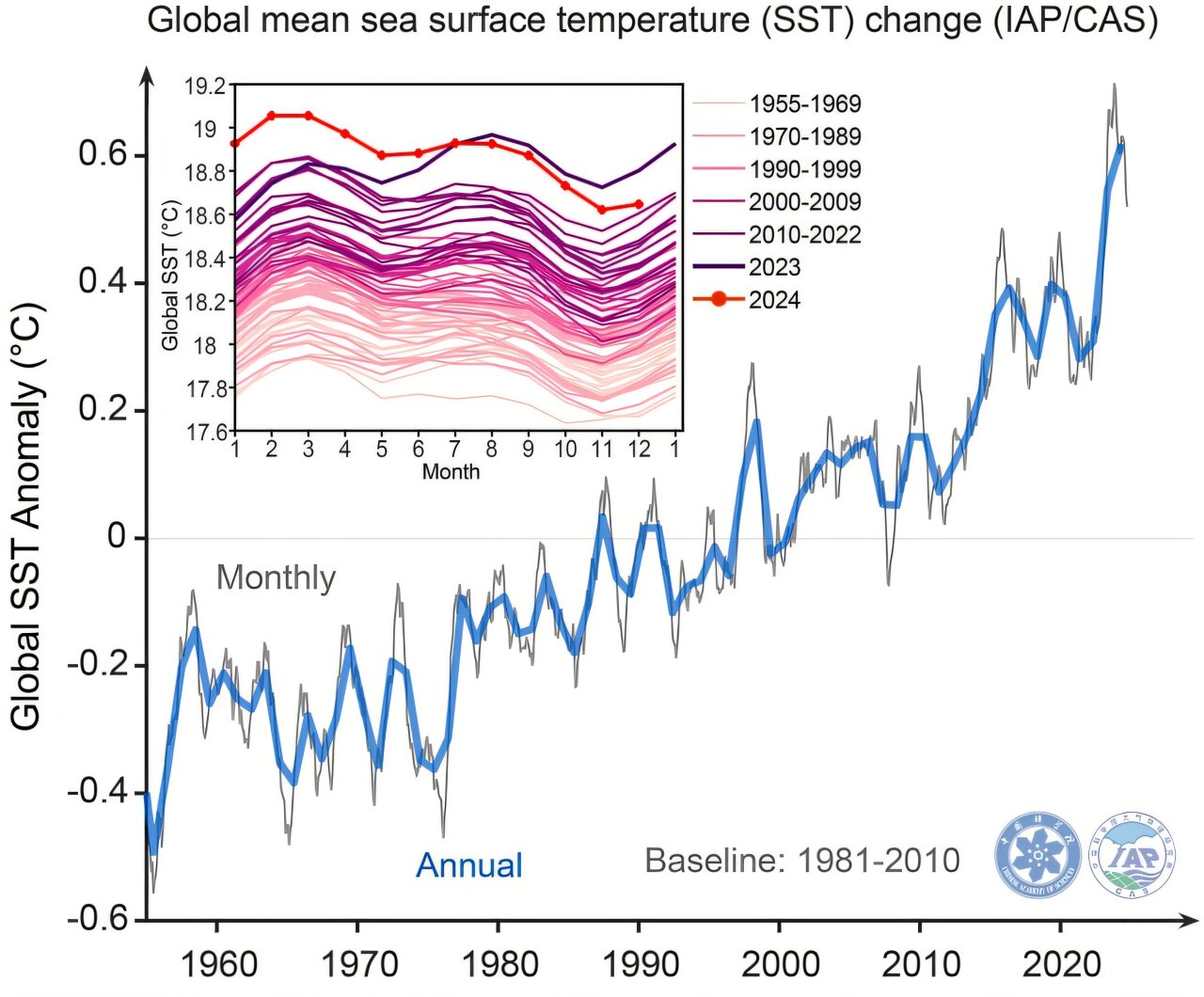

The Difference Between Surface Temperatures and Ocean Heat Content

Here's where things get confusing for most people following climate news. Surface ocean temperatures in 2025 were actually slightly lower than 2024, which holds the record as the hottest year since modern measurements began. How can the ocean be absorbing more heat while surface temperatures drop? The answer reveals something crucial about how climate change actually works.

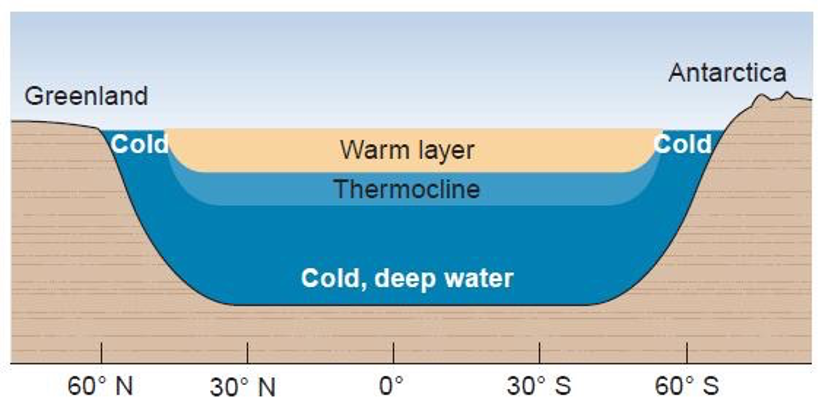

Most people think ocean warming means warmer beaches and swimsuit-friendly water everywhere. That's surface-level thinking, literally. The ocean's surface is a thin skin floating on top of something vastly larger and more complex. About 90 percent of the excess heat trapped in our atmosphere goes into the ocean, but most of that heat doesn't stay at the surface. It sinks.

Water is a weird substance with unique thermal properties. When surface water gets heated, it becomes less dense and wants to stay on top. But the ocean has currents and circulation patterns that push warm water downward into the deeper layers. Over months and years, heat gradually migrates into the thermocline and beyond, down to the abyssal depths where the water is so dark and cold that most humans never think about it.

Zeke Hausfather is a research scientist at Berkeley Earth and a coauthor of the ocean heat study. He explains this disconnect with a helpful analogy: "If the whole world was covered by a shallow ocean that was only a couple feet deep, it would warm up more or less at the same speed as the land. But because so much of that heat is going down in the deep ocean, we see generally slower warming of sea surface temperatures than those on land."

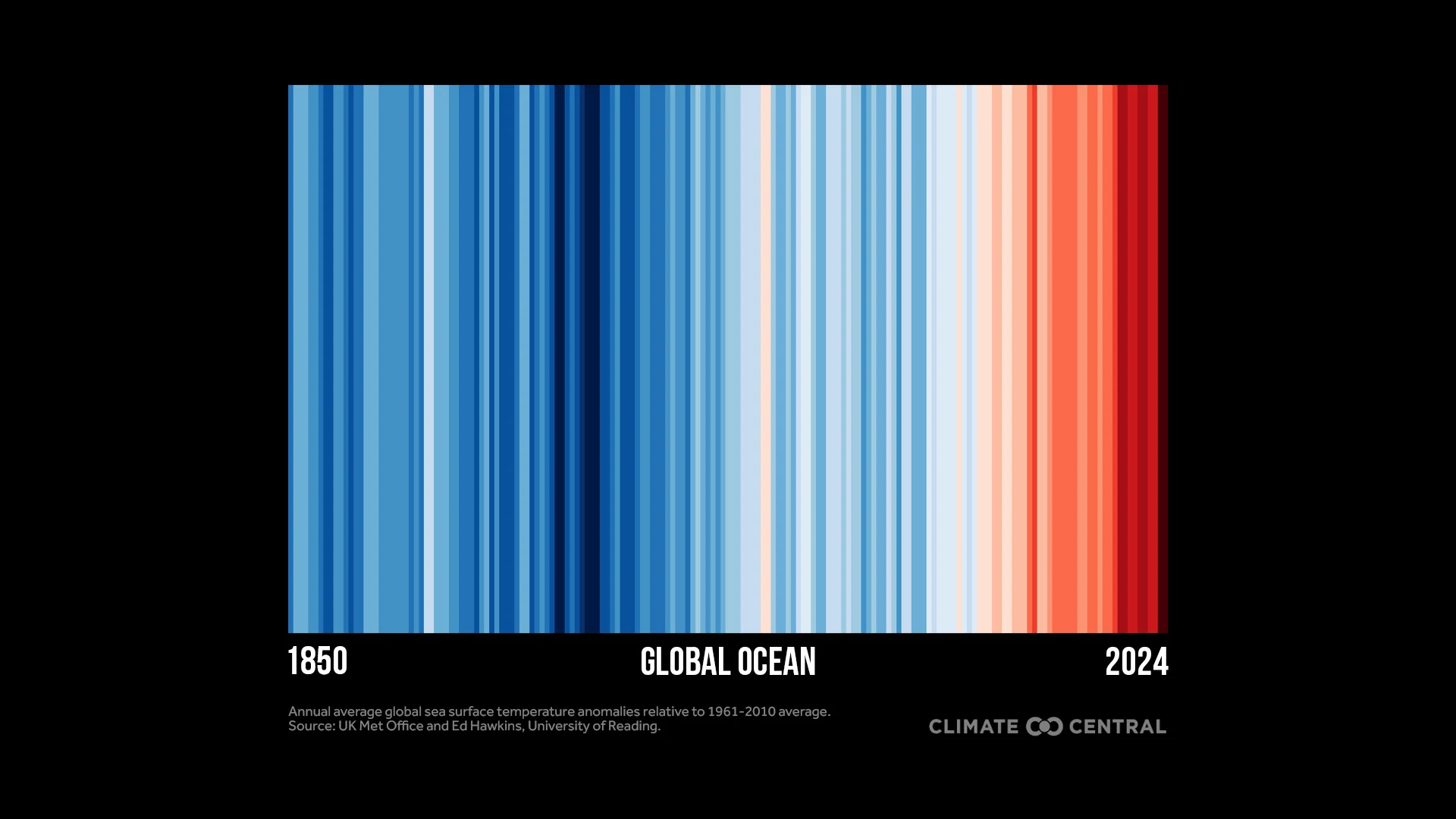

This matters because global temperature records—the ones used to determine hottest years on record—primarily capture surface measurements. Sea surface temperatures have definitely risen since the industrial revolution thanks to fossil fuel use. But they don't tell the whole story. The real heat accumulation is happening below.

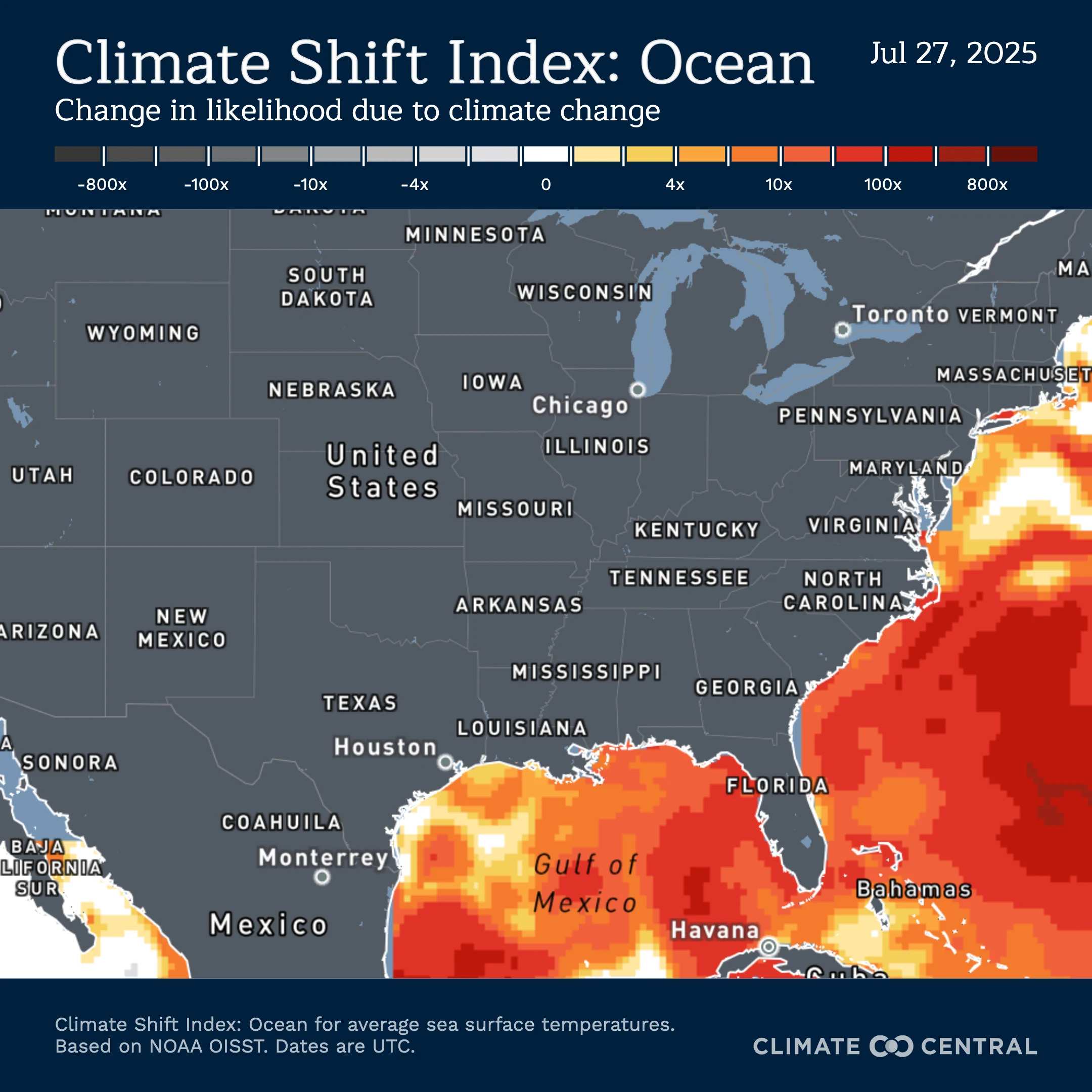

Surface temperatures are what directly impact human societies in obvious ways. They influence weather patterns, affect the ocean life we harvest and interact with, and determine whether a beach feels pleasant in summer. But for understanding whether climate change is actually getting worse, ocean heat content is far more reliable. It's the planet's thermostat, and the reading keeps climbing higher, as noted by Climate Central.

Why Ocean Heat Content Is the Most Reliable Climate Metric

Hausfather says something that should shake anyone thinking seriously about climate change: "Ocean heat content is in many ways the most reliable thermostat of the planet. That's where all the heat is going, and that's the reason why almost every year we set a new record for ocean heat content, because there's so much heat being absorbed by the ocean."

Think about what that statement implies. We have a direct measurement of how much energy is accumulating in Earth's climate system. It's not a proxy. It's not an estimate based on atmospheric readings or climate models run on computers. It's actual measurements of actual water temperature at actual depths across the actual ocean. And those measurements show consistent, accelerating accumulation of thermal energy.

Why does ocean heat content matter more than surface temperatures? Because the ocean is massive. The sheer volume of water is almost incomprehensible. The Pacific Ocean alone covers 165 million square kilometers and averages 4,000 meters deep. The water's massive thermal capacity means it acts as a buffer for the entire climate system. When heat gets absorbed by the ocean, it's essentially sequestered from the atmosphere.

This has both good and bad implications. On the positive side, the ocean absorbs heat that would otherwise make the atmosphere even hotter, potentially triggering more severe weather extremes. On the negative side, that heat doesn't disappear. It stays in the ocean. And a warmer ocean changes everything about marine ecosystems, ocean chemistry, and long-term climate patterns.

The consistency of the record-breaking pattern is what alarmed researchers most. Eight consecutive years of record ocean heat content isn't a coincidence or natural variability. It's a signal. And not a subtle one. Every measurement system available—Argo floats, satellite data, buoy networks, ship-based observations—all independently confirm the same trend, as reported by Science Daily.

Raphael Kudela is an ocean science professor at UC Santa Cruz who wasn't involved in the study but has reviewed similar research. He notes: "What people often don't grasp is that it's taken 100 years to get the oceans that warm at depth. Even if we stopped using fossil fuels today, it's going to take hundreds of years for that heat to circulate back out of the ocean."

This is the climate commitment problem that keeps oceanographers awake at night. The warming we're experiencing now is partly from carbon dioxide we emitted decades ago. The warming locked in for the next few centuries comes from what we're emitting right now. We're not just dealing with current problems. We're compounding future problems every single year we maintain high emissions.

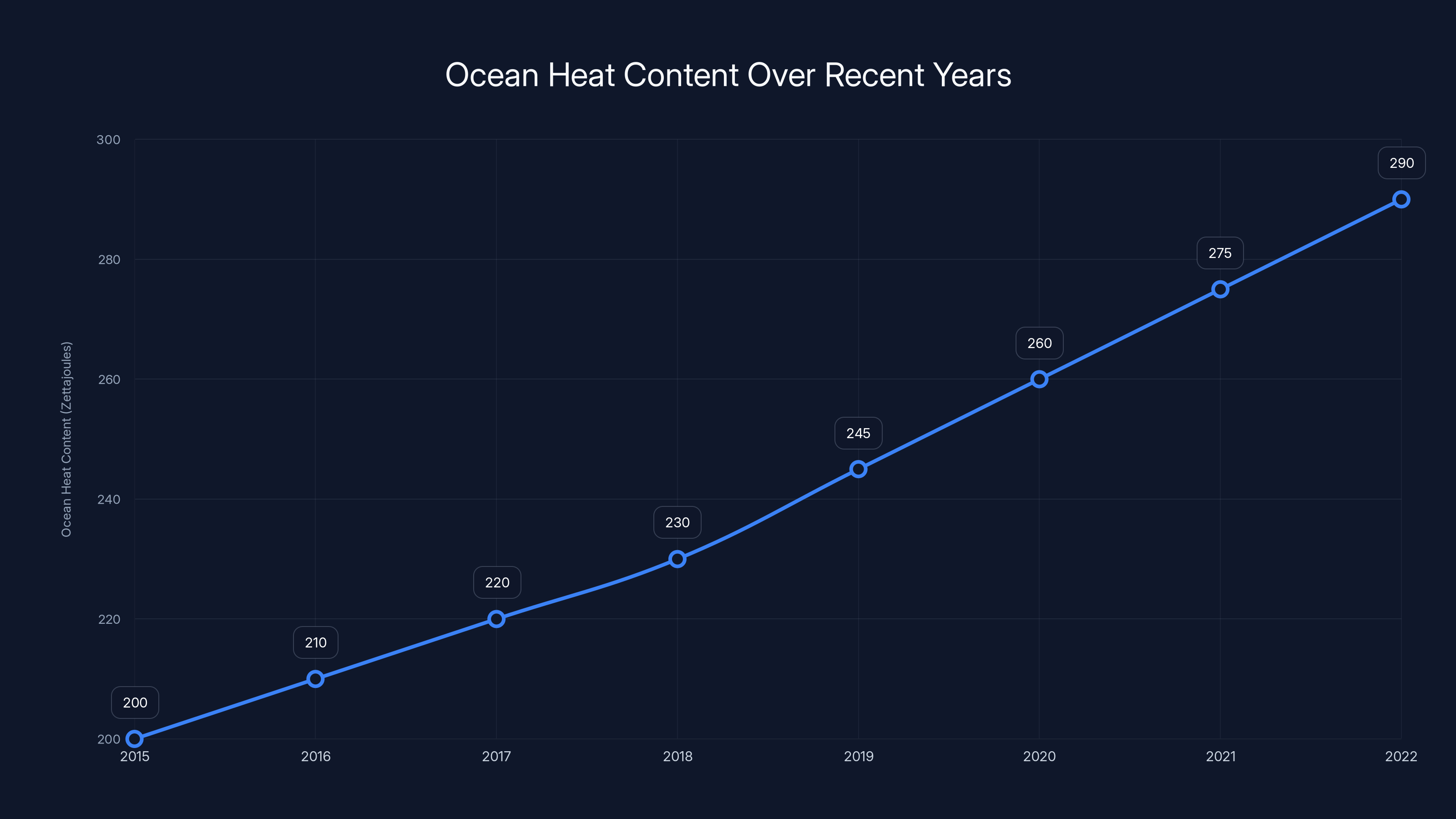

The chart shows a consistent increase in ocean heat content over the past eight years, highlighting the ocean's role in absorbing excess heat from the atmosphere. Estimated data based on trends.

How Scientists Measure Ocean Heat: From Franklin to Argo Floats

Measuring ocean heat content at scale is surprisingly complicated. For centuries, humans couldn't see beneath the waves with any precision. Benjamin Franklin, during his transatlantic voyages in the late 1700s, recorded sea surface temperatures. That was cutting-edge oceanography at the time. In the 1870s, the HMS Challenger expedition revolutionized the field by taking temperature measurements at deeper depths, essentially inventing modern oceanography.

But regularly, systematically measuring temperatures substantially below the surface remained nearly impossible until very recently. The earliest reliable data the current study uses dates back to the 1960s, when some navies began taking measurements of deep ocean temperatures. That might seem like a long time, but for understanding climate trends that play out over decades and centuries, 60 years of data is relatively short.

The game-changer came with Argo floats. The international Argo network, deployed starting in the early 2000s, consists of over 3,500 robotic buoys distributed across the world's oceans. These devices are mechanical marvels of simplicity and effectiveness. An Argo float sinks down to a programmed depth—typically around 2,000 meters—where it waits for a predetermined time. It then rises toward the surface, measuring water temperature and salinity at regular intervals as it ascends. When it reaches the surface, it transmits its data via satellite to research centers, then cycles back down to repeat.

The beauty of Argo floats is their ubiquity and consistency. You've got thousands of these devices constantly collecting data across every major ocean basin. The measurements are standardized, automated, and not subject to human observation bias. They revolutionized our understanding of deep ocean temperatures in ways that weren't previously possible.

But Argo floats are just one piece of the data puzzle. The study the 50+ scientists published uses a mix of data sources: Argo floats, temperature measurements from buoys, readings taken from ship hulls, satellite observations, and something that sounds almost fantastical—instruments mounted on marine mammals.

Yes, that's real. Researchers actually attach temperature sensors to seals, whales, and other diving mammals that swim under arctic ice and in remote regions where robotic instruments can't easily reach. As these animals dive and hunt, the sensors collect temperature data. It's a clever workaround for areas where traditional instrumentation would be impossible or prohibitively expensive.

The study also employs sophisticated algorithmic models trained on extensive datasets of ocean measurements. These models can fill gaps in coverage and help interpolate between measurement points. The algorithms aren't pure guessing—they're trained on actual measured data and validated against independent observations.

Raphael Kudela, in assessing this methodology, noted: "It's really quite impressive that they get such consistent results using multiple datasets." When independent measurement systems all point toward the same conclusion, it's nearly impossible to argue the findings are an artifact of methodology. The consistency itself becomes proof.

The Role of El Niño and La Niña in Ocean Heat Patterns

Anyone who follows climate and weather news has probably heard about El Niño and La Niña. These are the ocean's mood swings, patterns of natural variability that can significantly influence climate over months or years. Understanding how they interact with long-term ocean warming is crucial for interpreting the data.

El Niño occurs when unusually warm water in the western Pacific Ocean shifts eastward, disrupting normal trade wind patterns and ocean circulation. This phenomenon causes increased evaporation, changes rainfall patterns across continents, and typically results in warmer sea surface temperatures globally. It usually lasts for a year or two before the system reverses. La Niña is the opposite pattern—unusually cool water in the eastern Pacific suppressing sea surface temperatures and shifting weather patterns in the opposite direction.

These cycles have always existed, long before humans started burning fossil fuels. They're part of natural climate variability. The challenge for scientists is distinguishing between warming caused by these natural cycles and warming caused by increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Here's where 2024 and 2025 become particularly instructive. 2024 was classified as the hottest year on record by most metrics, and it came at the tail end of a strong El Niño event. El Niño boosts sea surface temperatures, which contributes to global temperature records. You might expect 2025 to be slightly cooler since the El Niño weakened and a weak La Niña developed. Normally, La Niña would reduce ocean heat absorption.

Instead, ocean heat content in 2025 soared to record levels despite the natural cooling influence of developing La Niña conditions. This is what makes the data so significant. The underlying human-caused warming trend is so dominant that it's overwhelm natural variability. A condition that normally reduces heat absorption only minimally dented the record warming.

This pattern has critical implications. If human-caused warming is so strong that it dominates over natural cycles, then expecting natural variability to provide relief is wishful thinking. We can't count on La Niña to cool things down. We can't assume that the next decade will be naturally cooler. We're in a regime where the signal is so powerful that year-to-year noise barely matters anymore, as noted by The Guardian.

The study also notes that 2024's status as the hottest year despite absorbing less ocean heat demonstrates how El Niño warming affects surface temperatures differently than deep ocean heating. Surface temperatures are more directly influenced by the current El Niño or La Niña state. Deep ocean heat reflects the long-term accumulation of energy from all sources. Both metrics matter, but they tell different stories about different timescales.

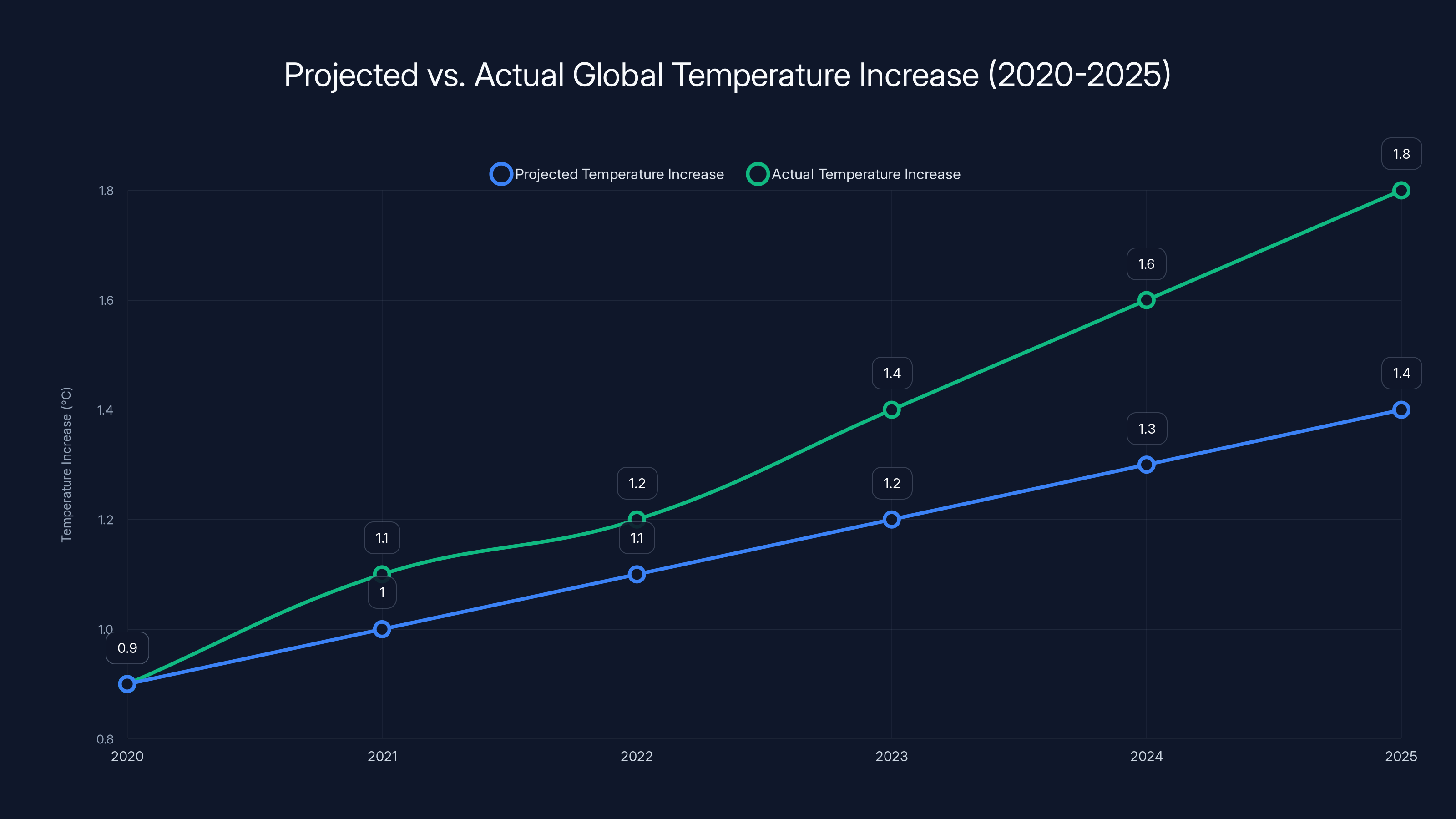

The actual global temperature increase from 2020 to 2025 exceeded climate model projections, indicating potential underestimation of climate sensitivity or feedback mechanisms. Estimated data.

The Fossil Fuel Connection: Why This Is Happening

None of this happens in a vacuum. The ocean heat content isn't rising because of cosmic rays or solar cycles or any of the alternative explanations that sometimes get mentioned. It's rising because of carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases humans pump into the atmosphere every single day.

The physics is straightforward and was understood well over a century ago. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases let visible light from the sun pass through to Earth's surface. But they absorb infrared radiation (heat) that bounces back up from the surface. This trapped heat has to go somewhere. About 90 percent of it ends up in the ocean.

Since the industrial revolution, humans have burned coal, oil, and natural gas at ever-increasing scales. We've also cleared forests, which previously absorbed carbon dioxide, replacing them with development. We've added roughly 50 percent more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than existed for the previous 800,000 years. This isn't conjecture or modeling. It's basic atmospheric chemistry and historical measurement.

The ocean has been absorbing the excess heat for all this time. It's like a massive, slow-acting sponge. Year after year, more heat gets absorbed. The deeper it penetrates, the longer it stays. A water molecule at 3,000 meters depth might take centuries to return to the surface. The heat trapped down there is essentially locked in for generations.

When Hausfather and colleagues discuss the implications, they emphasize something crucial: even if humans stopped using fossil fuels tomorrow, the ocean would continue releasing heat slowly back to the atmosphere for centuries. The warming we're experiencing now is partly due to emissions from decades ago. The warming guaranteed to happen in the future is due to what we're emitting right now.

This is what scientists call "committed warming" or "climate commitment." It's the warming that's already baked into the system regardless of what we do tomorrow. The amount of committed warming depends on how much carbon we've already added and how long it lingers in the atmosphere. But the basic principle is simple: today's emissions commit us to specific amounts of future warming.

For the ocean specifically, Kudela's observation about timescales is sobering: "Even if we stopped using fossil fuels today, it's going to take hundreds of years for that heat to circulate back out of the ocean." That's not a reason to give up and do nothing. It's an urgent call to stop adding more heat to a system that's already dangerously warm.

Impacts on Marine Ecosystems: What Happens When Oceans Get Hotter

Warmer ocean temperatures aren't just a statistic. They're restructuring marine ecosystems in real time. Fish species are migrating toward the poles as their preferred temperature ranges shift. Coral reefs, which thrive in narrow temperature bands, are experiencing bleaching events with increasing frequency and severity. Oxygen-depleted zones are expanding as warmer water holds less dissolved oxygen. Kelp forests are vanishing. Shellfish populations are declining. The list goes on.

The problem is that ocean ecosystems evolved over millions of years in relatively stable temperature conditions. Most marine species have narrow thermal tolerance ranges. When water temperatures change faster than organisms can adapt—and the current rate of warming is extraordinarily fast in evolutionary terms—they either migrate, fail to reproduce, or die.

Marine heatwaves, driven by anomalously warm water masses, have become increasingly common. These aren't just uncomfortable for sea creatures. They trigger cascading ecological effects. A marine heatwave in Australia in 2016 decimated rock lobster populations and altered fishing communities that depended on them. A 2019 heatwave off the Pacific coast of North America caused massive die-offs of seabirds and triggered harmful algal blooms.

The problem compounds because different species respond differently. Predator populations might thrive in warmer water while prey species collapse. Invasive species from warmer regions might establish themselves in newly warming areas. Entire food webs can reorganize. The creatures humans depend on for food—fish, shellfish, seaweed—are all experiencing these ecological pressures.

Coral reefs are perhaps the most visible casualty. Coral animals form symbiotic relationships with zooxanthellae, microscopic algae that live in the coral tissue and provide energy through photosynthesis. When water gets too warm, corals expel the zooxanthellae in a stress response called bleaching. The coral can survive the bleaching temporarily, but if water temperatures don't cool down, the coral starves and dies. Over the past few years, we've witnessed multiple global coral bleaching events affecting reefs across the Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean.

When coral reefs die, entire ecosystems collapse. Reefs provide nurseries for young fish, shelter for countless organisms, and protection for coastlines from storms. Communities that depend on reefs for fishing, tourism, or coastal protection face economic and food security crises.

Ocean acidification adds another layer of complexity. When seawater absorbs carbon dioxide, it forms carbonic acid, making the ocean more acidic. This affects creatures with calcium carbonate shells or skeletons—pteropods, corals, mollusks, and many others. Even small changes in pH can impair development, reduce shell hardness, and harm sensory abilities in these organisms.

The creatures at the bottom of food webs are often the most vulnerable. If tiny pteropods (sea butterflies) that feed on phytoplankton are harmed by acidification, it affects everything that eats them, all the way up to whales. The impacts ripple through ecosystems in ways that are hard to predict but easy to recognize in retrospect.

Ocean heat content has been increasing annually, with a dramatic 43% rise in 2025 compared to 2024, indicating accelerating climate change impacts. Estimated data.

Regional Variations: Not All Oceans Warm Equally

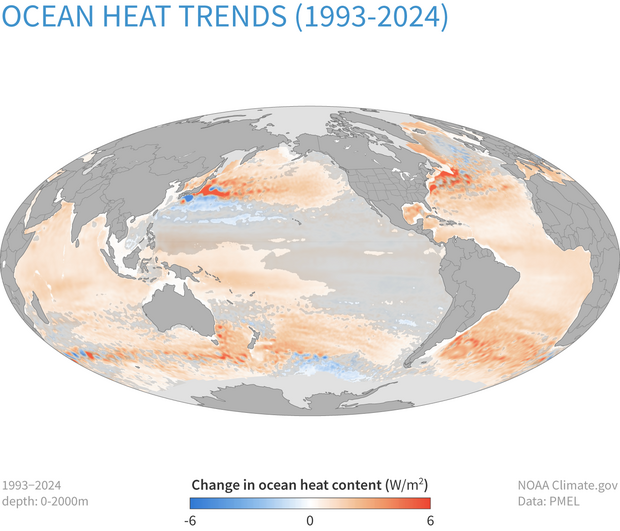

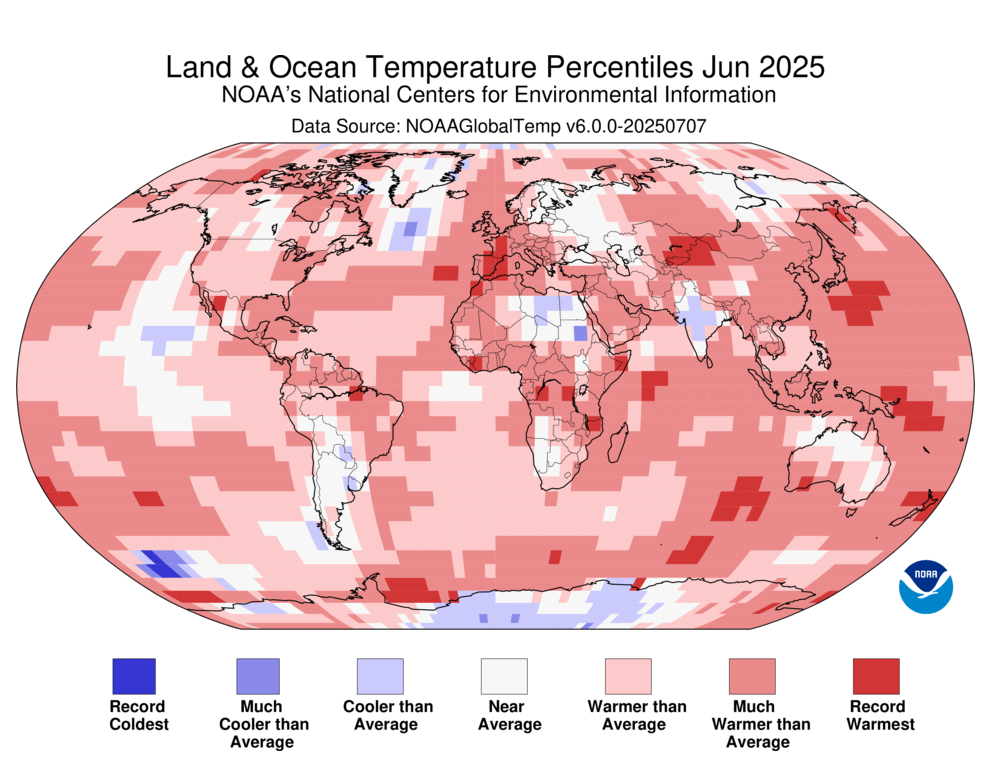

While global ocean heat content shows a clear upward trend, the warming isn't distributed evenly. Some regions are heating much faster than others. Understanding these regional differences matters because they drive local ecological changes and weather pattern shifts.

The Atlantic Ocean has been warming faster than the Pacific on average. The North Atlantic has been particularly affected, with some regions showing warming rates two to three times faster than the global average. This is partly due to changes in ocean circulation patterns. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream, has been weakening. This means less heat gets transported from the tropics toward the poles, causing some regions to warm while others cool slightly. But the overall pattern is toward more heat accumulation.

The Arctic Ocean presents a special case. Polar regions are warming faster than the global average in a phenomenon called "Arctic amplification." When sea ice melts, it reduces the ocean's reflectivity (albedo), causing more solar energy to be absorbed rather than reflected back to space. This creates a feedback loop where warming causes ice loss, which causes more warming. Arctic waters are warming at roughly twice the rate of the global ocean average.

Tropical oceans, while not warming as fast in absolute terms, are already close to the thermal limits many species can tolerate. A region that's 28 degrees Celsius on average is more vulnerable to reaching the 30+ degree threshold where corals bleach than a region that's 15 degrees on average. Tropical species also have narrower temperature tolerance ranges because they evolved in relatively stable conditions. This makes tropical ecosystems particularly vulnerable even though the actual temperature increases might be smaller.

The Mediterranean Sea, the Caribbean, the waters around East Asia, and other enclosed or semi-enclosed basins often show more extreme warming than open oceans. These regions have limited water exchange with broader ocean currents, so heat accumulates more intensely. Marine heatwaves in these areas have triggered ecological crises with local economic impacts.

Upwelling zones deserve special attention. In certain coastal regions, winds drive deep, cool, nutrient-rich water up toward the surface. These areas are incredibly productive biologically and support major fisheries. Warming affects upwelling systems in complex ways. Changes in wind patterns can reduce upwelling strength. Warmer surface water can inhibit the ascent of cold water. Even when upwelling continues, it brings up warmer water than it did historically. These changes cascading through productive fishing regions create real impacts for communities that depend on them.

Implications for Weather Patterns and Atmospheric Circulation

Warmer oceans don't just affect marine life. They fundamentally alter atmospheric circulation patterns that determine weather across the globe. This is where ocean warming becomes everyone's problem, not just fishers' and researchers' problem.

Ocean temperature influences how much water evaporates, which determines atmospheric humidity and the moisture available for precipitation. Warmer oceans mean more evaporation, more atmospheric moisture, and ultimately more potential for extreme precipitation events. This doesn't mean it rains more everywhere—some regions actually get drier as circulation patterns shift. But where it does rain, it can rain harder.

The jet streams—fast-moving rivers of air high in the atmosphere that steer weather systems—are influenced by temperature differences between the tropics and poles. As the Arctic warms faster than the tropics, this temperature gradient weakens. A weaker temperature gradient means the jet stream meanders more, potentially getting stuck in patterns that bring persistent weather features. This is one hypothesis for why heat domes, cold snaps, and other extreme weather events have become more common and longer-lasting.

Tropical cyclones (hurricanes, typhoons) are directly energized by warm ocean water. The warmer the water, the more potential energy is available to power storms. We're seeing evidence of stronger rapid intensification of storms and higher intensity storms overall. A warmer atmosphere also holds more moisture, which storms can tap into for precipitation. Cyclones are therefore becoming both stronger and wetter.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is showing signs of weakening. This system includes the Gulf Stream, which transports warm water northward toward the Arctic. AMOC weakening means less heat gets transported poleward, which actually causes some regions (like parts of Europe) to remain cooler than they would otherwise. But overall, it represents a disruption of a major planetary circulation system, with unpredictable consequences.

Monsoonal systems, which provide the majority of rainfall for billions of people, are shifting in intensity and timing. The Indian monsoon, the African monsoon, the Asian monsoon—all show changes correlated with ocean temperature patterns. When these shift, it affects agricultural production, water availability, and flood risk for vast populations.

The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and other multi-year climate patterns all operate against a backdrop of rising baseline temperatures. Natural variability still exists, but it's expressed around a warming trend. This means that "normal" years today are warmer than "normal" years a few decades ago, and extreme years are even more extreme.

In 2025, ocean heat absorption reached a record 23 zettajoules, marking a 43% increase from 2024. Estimated data based on reported trends.

The Timeline Problem: Why Waiting Makes Everything Worse

One of the hardest concepts for non-scientists to grasp is the lag between cause and effect in the climate system. We talk about "committed warming" and "climate inertia" in scientific papers, but the implications deserve plain language explanation.

When we emit carbon dioxide today, it doesn't cause all its warming immediately. Some warming happens within years or decades as the atmosphere adjusts. But much of the warming happens over centuries as the ocean slowly releases heat back to the atmosphere and as ice sheets gradually respond to warming. This is why even if we stopped all emissions tomorrow, temperatures would keep rising for quite some time.

The ocean's thermal mass is the culprit. It takes an enormous amount of energy to heat water compared to heating air or land. Conversely, it takes an enormous amount of time for that heat to dissipate. A water molecule that absorbs heat at the surface might take 1,000 years to return to the surface again, slowly releasing that heat to the atmosphere as it does.

This lag creates a paradox. The longer we wait to reduce emissions, the more committed warming we lock in. But because some of that committed warming won't materialize for centuries, people alive today might not experience the full consequences of the choices we're making right now. This temporal disconnect makes climate change psychologically difficult. There's no immediate feedback punishing overconsumption the way a credit card bill does.

But the urgency is real. The difference between 1.5 degrees Celsius of total warming and 2 degrees Celsius is enormous in terms of ecosystem tipping points, ice sheet stability, and permafrost thaw. The difference between 2 degrees and 3 degrees is even more dramatic. Every tenth of a degree of warming we avoid now prevents specific climate impacts later.

For the ocean specifically, the timeline is stark. Kudela's statement is worth repeating: "Even if we stopped using fossil fuels today, it's going to take hundreds of years for that [ocean] heat to circulate back out." The heat we're adding now will be releasing into the atmosphere and affecting weather patterns for centuries. We're not just dealing with our generation's climate. We're determining the climate our great-grandchildren and their descendants will experience.

There's also the tipping point problem. If ocean circulation systems fundamentally reorganize, if ice sheets begin collapsing faster than models predict, if methane releases from thawing permafrost accelerate—these aren't gradual changes. They're potentially abrupt reorganizations of planetary systems. And once they're triggered, they're essentially impossible to stop. The ocean warming we're measuring now could be pushing us toward some of these threshold points.

Comparing 2025 to Previous Record Years: A Trend Line

Looking at individual years is useful, but the bigger picture emerges when you see the trend. Let's walk through what the data shows from the 1960s onward, with particular attention to recent years.

For decades, ocean heat content increased gradually. The warming was real, but year-to-year variability sometimes masked the trend. You could have a slightly cooler year followed by a warmer year, making the trend less obvious. But starting around 2015-2016, something shifted. The year-to-year increases became more dramatic. More importantly, the floor kept rising. Even "cooler" years were warmer than previous decades' hottest years.

2016 was the previous record holder before the recent string of records. That was a strong El Niño year, which boosted heat absorption. Climate skeptics argued that once El Niño ended, temperatures would cool off. They didn't. The baseline kept rising.

2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 all set new records. Some years were influenced by weak El Niño conditions, others by neutral or weak La Niña conditions. The variability didn't matter. The underlying trend was inexorable. Then came 2023, which was even hotter. Then 2024, which was hotter still. And now 2025, which blew past all previous records.

The cumulative heat absorbed since 1960 is difficult to comprehend. It's in the hundreds of zettajoules. If you wanted to distribute that energy evenly across Earth's land surface, you could boil the soil. If you wanted to use it to generate electricity, it would supply the planet's total electrical demand for years. Instead, it's all sitting in the ocean, slowly penetrating deeper, altering chemistry and ecosystems.

What's particularly notable is how rapidly the recent records have accelerated. The jump from 2024 to 2025 is the largest single-year increase the researchers have measured. This suggests the system isn't slowly warming toward some new equilibrium. It's accelerating. Each year's temperature might not be a record, but the trend line is unmistakably steep.

When researchers analyze this data, they're not just looking at numbers. They're watching a planetary system respond to forced change in real time. The consistency across multiple measurement systems, the agreement with climate models, and the magnitude of recent increases all point toward one conclusion: we're in a period of rapid climate change, and the ocean is the primary expression of that change.

The Role of Climate Models: How Scientists Predicted This

One might ask: why were scientists surprised by the 2025 data if climate models have been predicting warming for decades? The answer reveals something important about how scientific prediction actually works.

Climate models have accurately predicted the general warming trend. They've been remarkably successful at forecasting long-term changes in global temperature and ocean heat content. The surprise isn't the direction of change. It's the magnitude and rate in very recent years.

Models show some uncertainty in predicting year-to-year variability, particularly the short-term impacts of things like El Niño cycles or volcanic eruptions. They're also somewhat uncertain about exactly how fast different processes occur. Some models predict faster ocean warming than others. Some predict more extreme weather intensity increases than others.

What's unusual about 2024-2025 is that the warming exceeded what most models predicted for this time period. This could mean a few things. It could mean that climate sensitivity (how much warming results from a given amount of carbon dioxide) is higher than modeled. It could mean that particular feedback mechanisms are stronger than expected. Or it could mean that we're on the high end of the probability distribution and experiencing a period of particularly rapid change by chance.

One concerning possibility is that the models underestimated how much additional warming would occur from causes beyond just increased carbon dioxide. For example, changes in atmospheric aerosols could be contributing. Reduction in certain industrial aerosols—"global dimming" effects—happened as emissions regulations were enacted in developed countries. Without those aerosols reflecting sunlight, Earth's surface receives more radiation. Changes in water vapor content, cloud cover, and other factors could also be playing a role.

The models are also constrained by what we understood about climate physics at the time they were constructed. New mechanisms are being discovered. For instance, research on how changing ice sheets and mountain snow cover affect planetary reflectivity is evolving. Models incorporating these newly understood mechanisms might produce different predictions.

But here's the crucial point: even if we were surprised by how fast things are warming, the direction is exactly what models predicted. Models said the ocean would warm. Models said warming would accelerate as carbon dioxide accumulated. Models said deep ocean temperatures would rise. Every single one of those predictions is proving accurate, just sometimes faster than expected.

This is why ocean heat content serves as an excellent proxy for whether reality is tracking with model predictions. The overall trajectory is what matters more than individual year predictions. And the trajectory is worse than many people realized.

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies: What Can We Do?

Understanding the problem is important, but so is understanding possible solutions. They fall into a few categories: reducing emissions (mitigation), adapting to changes already inevitable (adaptation), and research into more speculative solutions.

Emissions Reduction

The most effective solution remains reducing fossil fuel consumption. This is obvious but worth stating directly. Every ton of carbon dioxide we don't emit is a ton that won't trap heat for centuries. Energy transitions to renewables, electrification of transportation, efficiency improvements in buildings—these are proven technologies that work. The barriers are political and economic, not technical.

Timing matters enormously. If we rapidly transition away from fossil fuels in the next decade, we limit committed warming to perhaps 2-2.5 degrees Celsius. If we delay for another 20 years before making aggressive changes, we're looking at much higher ultimate warming despite eventual transition. The decade we're in determines the climate of the next century.

Adaptation to Unavoidable Change

Whatever emissions reductions happen now, some amount of ocean warming is already committed. Communities living on coasts, island nations, areas dependent on fisheries, regions vulnerable to changed precipitation patterns—these areas need to adapt. This means stronger infrastructure, different agricultural practices, managed retreat from some areas, marine protected areas to give ecosystems some resilience.

Adaptation is expensive and sometimes impossible. You can't adapt an island nation to complete submersion under the ocean. You can't adapt the entire global fishing industry instantly if fish stocks shift. But strategic adaptation in vulnerable regions can reduce suffering and economic loss.

Research Into Emerging Technologies

There's also ongoing research into technologies like direct carbon removal, ocean alkalinity enhancement, and other approaches. These remain experimental and expensive, but if deployed at scale, some could help. However, none of these are substitutes for emissions reduction. They're potentially useful supplements, but betting on them while continuing high emissions is like hoping a water filter will save you from jumping off a cliff.

Ocean Protection

One overlooked solution is marine protected areas and ecosystem restoration. If we protect kelp forests, seagrass meadows, mangrove forests, and coral reefs, they continue sequestering carbon and providing ecosystem services. Degraded ecosystems don't. Expanding marine protection and restoring damaged ecosystems isn't a climate solution on its own, but it's part of a comprehensive approach.

Shifting Perspectives

Perhaps the most critical shift is recognizing that ocean health is a global concern that affects everyone. Fishers depend on it. Coastal communities depend on it. The atmosphere's composition depends on it. The climate regulation it provides depends on it. It's not separate from human interests. It's fundamental to human survival.

The Path Forward: What This Means for Climate Action

The 2025 ocean heat records represent the latest data point in a long-term story of climate change. But they're a particularly striking data point. When every measurement system shows the same accelerating trend, when the magnitude of change exceeds predictions, when we see eight consecutive record years, it's difficult to interpret as anything other than a system in crisis.

This creates both urgency and opportunity. The urgency is obvious. We're running out of time to limit warming to any specific threshold. Every year of high emissions locks in additional centuries of ocean warming. The opportunity is that we know what solutions work. We have the technology. We have the resources. What we lack is political will and coordination at global scale.

The ocean warming affects everything else in the climate system. Warmer oceans drive stronger storms, change precipitation patterns, raise sea levels as water thermally expands and ice melts, acidify and deoxygenate, alter fish migration and abundance, trigger ecosystem reorganizations. It's the primary mechanism through which human carbon dioxide emissions translate into planetary-scale impacts.

For scientists studying this, the data is clear and consistent. For policymakers, the implications should be equally clear: continue current emissions trajectories, and you're essentially accepting severe climate impacts for centuries. Change course now, and you minimize the damage. There's no third option where things stay the same.

The eight consecutive years of record ocean heat content represent eight years of accelerating climate change. Unless something changes, the ninth, tenth, and eleventh years will probably be record years too. The data doesn't suggest we're approaching equilibrium. It suggests we're in a period of rapid acceleration that will continue as long as emissions remain high.

Whatever happens in climate negotiations, ocean heat content will continue climbing until atmospheric carbon dioxide stabilizes. Even then, warming will continue for centuries as that heat gradually propagates. We're not dealing with a problem that can be solved quickly. We're dealing with a long-term commitment we're making right now, one year at a time, one ton of emissions at a time.

FAQ

What is ocean heat content, and why does it matter more than surface temperature?

Ocean heat content measures the total thermal energy stored in the ocean from its surface down to deep depths. It matters more than surface temperature because about 90 percent of excess heat from greenhouse gases goes into the ocean, with most of it sinking to deeper layers where it remains for centuries. Surface temperatures are influenced by short-term weather patterns and seasonal cycles, while ocean heat content represents the true accumulation of energy in the climate system and is therefore a more reliable indicator of how rapidly climate change is progressing.

How do scientists measure ocean temperatures at depths of thousands of meters?

Scientists use multiple methods including Argo floats (over 3,500 robotic buoys that measure temperature while sinking and rising), satellite observations, temperature measurements from ship hulls and buoys, and even instruments attached to diving marine mammals like seals and whales. These measurement systems collect data across the global ocean and provide consistent, independent confirmation of warming trends, eliminating any possibility that results are artifacts of a single measurement method.

What does 23 zettajoules of heat actually mean in practical terms?

A zettajoule is one sextillion joules (23 followed by 21 zeros). To put this in perspective, the 23 zettajoules absorbed by oceans in 2025 equals the energy released by 12 simultaneous Hiroshima bombs, the energy required to boil 2 billion Olympic swimming pools, or more than 200 times all the electricity generated and used globally in a year. It's an almost incomprehensibly large amount of energy that's now stored in the world's oceans.

Why did ocean heat content increase more from 2024 to 2025 even though 2024 was the hottest year on record?

Surface temperatures and deep ocean heat accumulation respond differently to natural climate variations. 2024 was the hottest year partly because a strong El Niño event boosted surface temperatures. In 2025, a weak La Niña developed, which would normally cool ocean surfaces. However, the deep ocean's heat content continued accumulating at a faster rate than 2024, showing that the underlying human-caused warming is now so dominant that it overwhelms natural variability.

What happens to marine ecosystems when ocean temperatures increase?

Warmer oceans disrupt ecosystems by shifting species ranges toward the poles, triggering coral bleaching in tropical regions, reducing dissolved oxygen in deep waters, altering food web dynamics, and causing mismatches in breeding timing and food availability. Species experience stress when temperatures exceed their thermal tolerance ranges, causing migration, reproductive failure, or death. These changes cascade through ecosystems, affecting everything from tiny plankton to whales and impacting human fishing communities that depend on specific fish stocks.

If the ocean is warming, why don't we just reduce emissions slowly over several decades?

Every year of high emissions locks in additional centuries of future ocean warming due to the long lifespan of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the ocean's slow heat-release timescale. Waiting decades before aggressively reducing emissions means committing to far more severe climate impacts than reducing emissions rapidly now would cause. The difference between warming 1.5 degrees Celsius versus 2 degrees versus 3 degrees involves threshold changes in ice sheet stability, ecosystem collapse, and extreme weather intensity.

How are climate models performing given the unexpected rapid warming in 2024-2025?

Climate models have accurately predicted the general warming trend and the direction of climate change for decades. However, the rate of warming in very recent years has exceeded what many models predicted, suggesting that either climate sensitivity is higher than modeled, particular feedback mechanisms are stronger than expected, or we're experiencing a period of unusually rapid change. This doesn't invalidate models but rather indicates the real climate system may respond faster to greenhouse gas forcing than previously understood.

What can individuals do to help address ocean warming?

Reducing personal energy consumption, supporting renewable energy transitions, eating less energy-intensive food, reducing consumption of wild-caught fish from vulnerable stocks, and supporting policies that reduce emissions all have cumulative effects. More importantly, individuals can support broader systemic changes through political engagement and helping shift cultural attitudes toward valuing climate stability. While individual actions are important, the scale of the problem requires coordinated policy changes and global energy system transformation.

Conclusion: A Planet in Motion

The 2025 ocean heat data isn't an anomaly or a surprise. It's the continuation of a clear, consistent trend that's been building for decades. Eight consecutive years of record ocean heat content represents something more significant than just another hot year. It represents a climate system responding to human forcing in precisely the way physics predicts it should.

What makes 2025 remarkable isn't that it was hotter than 2024. What's remarkable is that it was so much hotter—43 percent more heat absorbed despite natural cooling influences from developing La Niña conditions. This isn't slow, incremental warming. This is acceleration. This is a system pushed far enough outside its normal range that it's responding with increasing intensity.

The ocean doesn't lie. It can't manipulate data. It can't have bias. It simply absorbs the excess heat that humans trap in the atmosphere and holds it, storing centuries of future warming in its depths. Every zettajoule represents choices we've made about how to power our civilization.

The implications extend far beyond oceanography. Warmer oceans mean disrupted ecosystems, shifted fisheries, altered weather patterns, rising seas, and acidified water. For billions of people whose lives depend directly or indirectly on healthy oceans, these aren't academic questions. They're existential concerns.

Yet the path forward remains clear even if it's become more urgent. Reducing emissions is the primary solution. It's not revolutionary. It's not even new. Every climate scientist has been saying the same thing for decades. Transition away from fossil fuels. Protect ecosystems. Adapt to unavoidable changes. Support research into emerging solutions. These aren't controversial or technically difficult. They're politically and economically challenging, but the technology exists.

What 2025's ocean data proves is that we don't have decades to figure this out. We have this decade. The choices we make in the next five to ten years will largely determine the climate of the rest of this century. That's not hyperbole. That's the output of climate physics and ocean dynamics.

The ocean has been absorbing heat on our behalf for centuries, muting climate impacts and giving us more time. It's given all the buffering it can. Now every choice we make about energy, consumption, and emissions is directly determining how rapidly the ocean will warm, how fast ice sheets will destabilize, and how severe the impacts will be for every ecosystem and community on the planet.

The 2025 records are a message written in water, in thermal energy, in accumulated heat. The ocean is telling us something. We can hear it clearly if we listen.

Key Takeaways

- Oceans absorbed 23 zettajoules of heat in 2025, the eighth consecutive record-breaking year, representing 43% more heat than 2024

- Deep ocean heat content is the most reliable indicator of climate change, with 90% of excess atmospheric heat being absorbed by oceans

- Warming oceans disrupt marine ecosystems through species migration, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, and altered food webs affecting global fishing

- Natural cooling cycles like La Niña no longer reduce ocean heat absorption, indicating the human warming signal has overwhelmed natural variability

- Committed warming will continue for centuries even if emissions stop today, making urgent action in the next decade critical for limiting future climate impacts

![Ocean Heat Records Shatter Again: What 2025's Climate Data Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ocean-heat-records-shatter-again-what-2025-s-climate-data-re/image-1-1767947898292.jpg)