Could You Walk on the Seafloor With an Upside-Down Rowboat? The Physics Behind Jack Sparrow's Impossible Escape

There's a scene in the original Pirates of the Caribbean that's stuck with me for nearly two decades. Captain Jack Sparrow and Will Turner, desperate to escape Port Royal, hoist an overturned rowboat above their heads and walk along the seafloor toward a ship anchored offshore. It's absurd. It's brilliant. It's the kind of thing that makes you immediately ask: could this actually work?

Most movie physics is complete nonsense, and honestly, that's fine. Movies don't need to follow Newton's laws to be entertaining. But this particular scene is different. It's not just spectacle. It's asking a legitimate question about buoyancy, pressure, and the forces that govern how objects behave in water. And unlike most Hollywood physics, this one is actually fun to work through with real math.

I'm not going to tell you that you should try this yourself (please don't), but I am going to show you exactly why it wouldn't work, what would need to change to make it viable, and what happens to air as you descend deeper into the ocean. Because here's the thing: understanding this scenario teaches you something genuinely useful about how the physical world works.

So let's abandon our modern sensibilities, grab some diving goggles, and figure out whether you could actually become a swashbuckling oceanographer using nothing but a small wooden boat and pure desperation.

TL; DR

- Buoyancy creates an upward force of roughly 6,600 pounds on a standard rowboat, far exceeding its actual weight

- You'd need 3+ tons of ballast (like gold) to keep the boat and crew on the seafloor without sinking further

- Air compression at depth reduces buoyancy slightly, but not enough to solve the weight problem

- Water pressure increases dramatically with depth, making breathing difficult and dangerous even if the boat stayed down

- The deeper you go, the less air you have, requiring either constant air supply or regular resurfacing

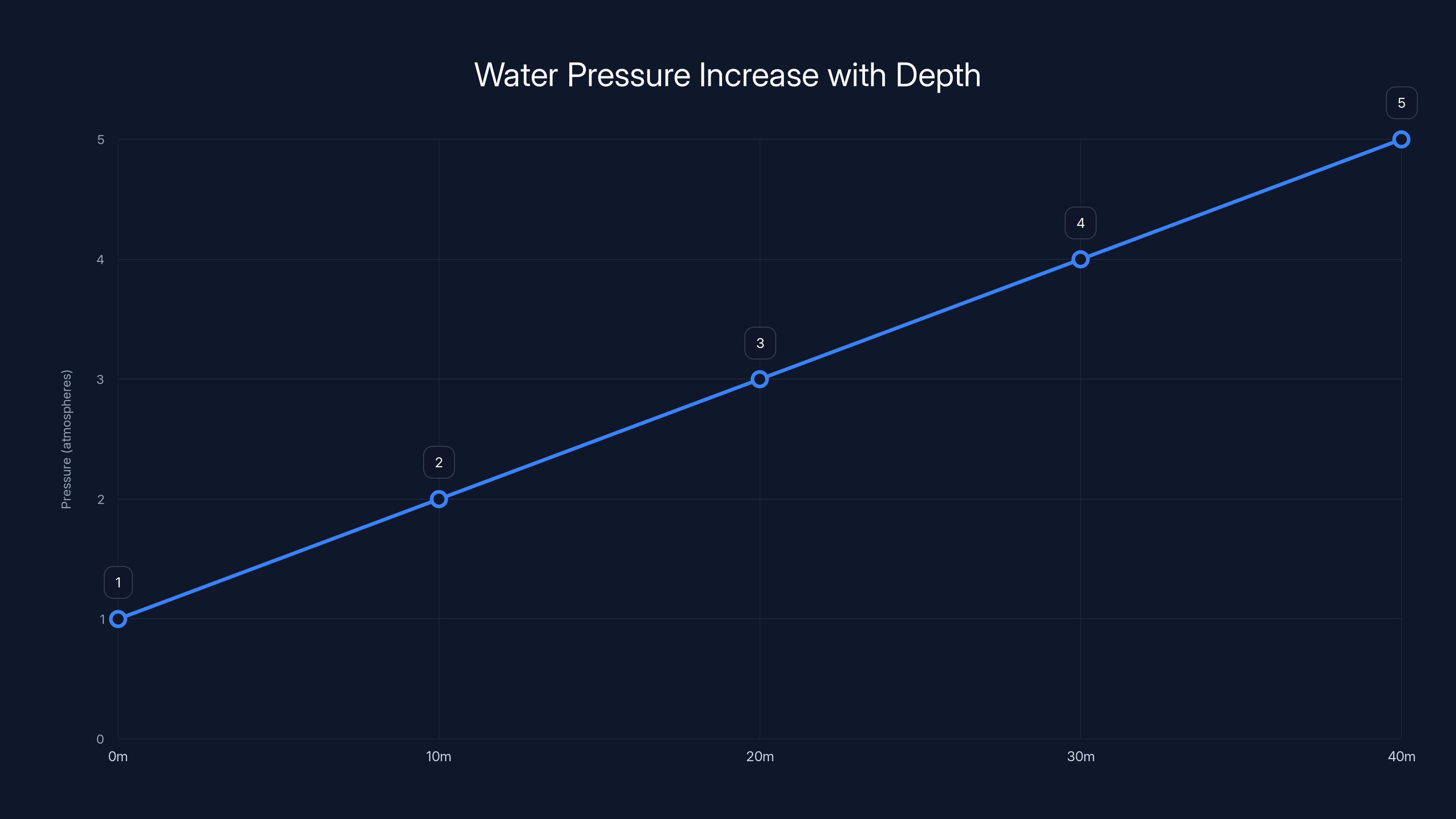

Water pressure increases by 1 atmosphere for every 10 meters of depth, reaching 5 atmospheres at 40 meters. This linear relationship is crucial for divers to understand pressure changes.

The Fundamental Problem: Understanding Buoyancy and Weight

Let's start with the obvious question: why does anything float? The answer lies in density, and it's more intuitive than you might think.

Imagine two blocks, each exactly one cubic foot in volume. One is made of steel, the other of styrofoam. Both have mass, calculated as volume multiplied by density. Steel is roughly 8 times denser than water, so the steel block sinks. Styrofoam is much less dense than water, so it floats. This seems straightforward enough.

But here's where it gets interesting. What happens if you place a block of pure water into a lake? It doesn't sink, and it doesn't float. It just sits there, perfectly still, at neutral buoyancy. This tells us something crucial: the gravitational force pulling the water down must exactly equal some upward force pushing it up. That upward force is called buoyancy.

Buoyancy is fundamentally about displaced water. The ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes figured this out over 2,000 years ago while taking a bath. The water you displace exerts an upward force equal to the weight of that displaced water. So if you push a cubic foot of water aside, you get an upward force equal to the weight of a cubic foot of water, which is about 62.4 pounds.

Now apply this to our steel block. It still displaces one cubic foot of water, so it receives the same 62.4-pound upward buoyancy force. But steel is much heavier than water, so gravity wins, and it sinks. For styrofoam, the upward buoyancy force exceeds its weight, so it floats up.

Humans sit right in the middle. Our bodies are roughly 60% water, which makes us almost neutral in buoyancy. That's why you feel weightless when you swim. The buoyancy force nearly cancels out gravity. You're not actually weightless—gravity is still pulling on you—but the water is pushing back up almost equally hard.

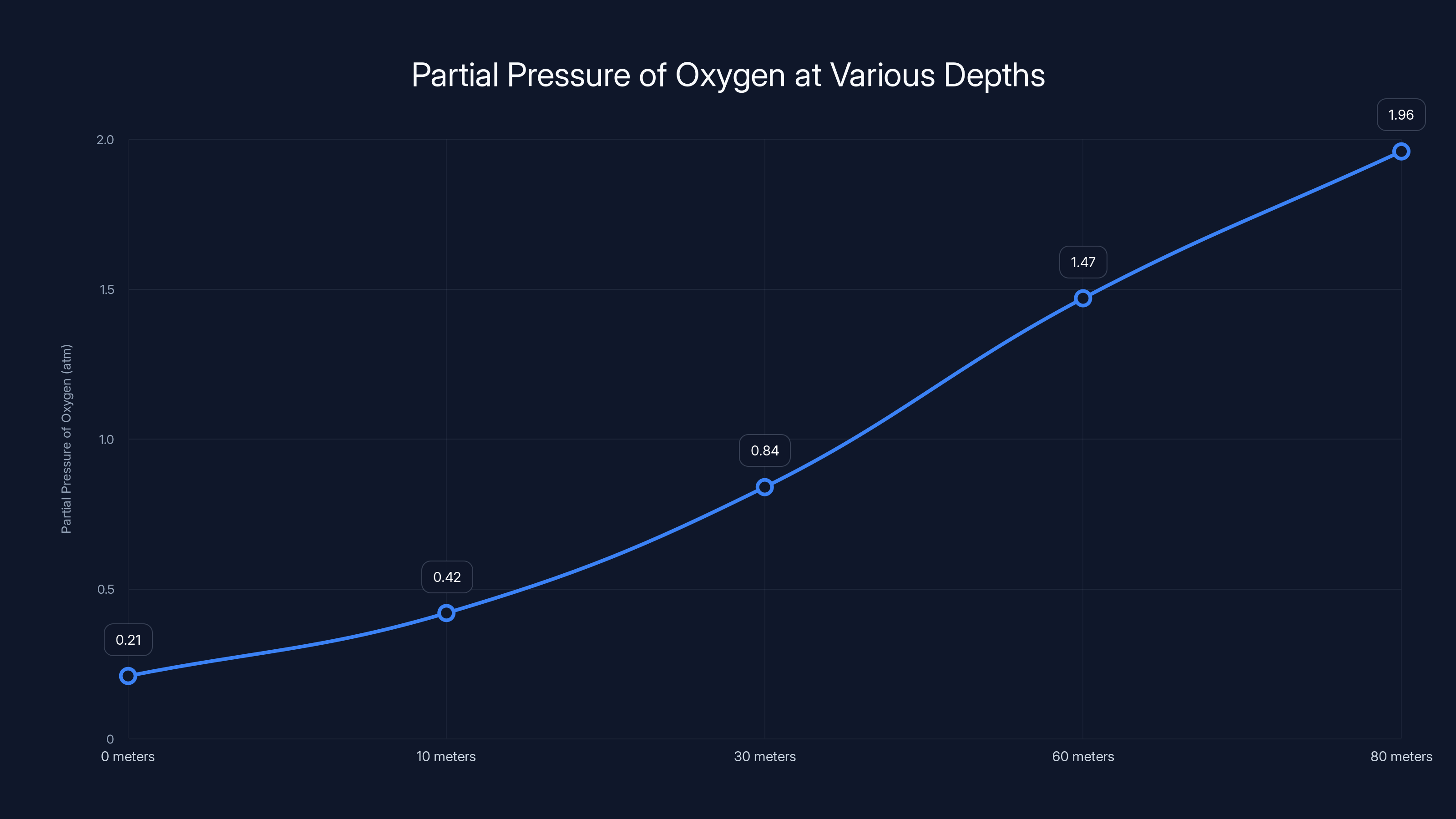

The partial pressure of oxygen increases with depth, reaching dangerous levels beyond 60 meters, risking oxygen toxicity. Estimated data based on typical atmospheric conditions.

Calculating the Buoyancy Force on a Rowboat

Let's get specific about the rowboat scenario. Imagine a standard dinghy or small rowboat with a volume of about 3 cubic meters when the interior is filled with air. What's the buoyancy force acting on it?

The formula is straightforward: Buoyancy Force = ρ × V × g, where:

- ρ (rho) is water density: 1,000 kilograms per cubic meter

- V is the volume of the boat: 3 cubic meters

- g is gravitational acceleration: 9.8 meters per second squared

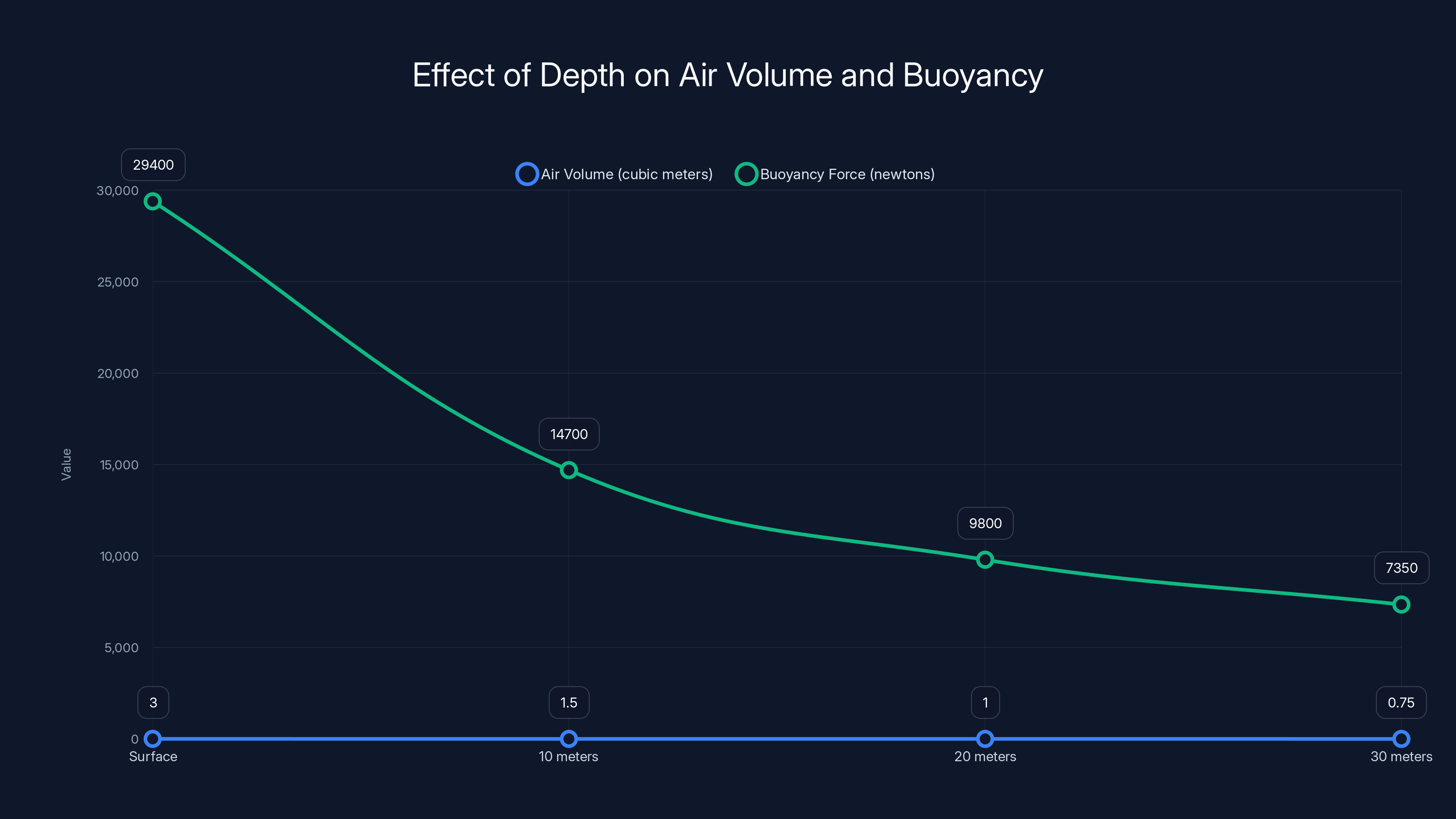

Do the math: 1,000 × 3 × 9.8 = 29,400 newtons, or roughly 6,600 pounds of upward force.

Now, how much does a rowboat actually weigh? A small fiberglass dinghy might weigh 300 to 500 pounds. Add two grown men (roughly 350 pounds combined), and you're looking at 650 to 850 pounds total. The buoyancy force is nearly 8 times greater than the weight of the entire system.

This is the central problem. The boat wants to shoot upward like a cork. Jack and Will wouldn't be calmly strolling along the seafloor. They'd be fighting against an upward force equivalent to having a thousand-pound rope tied to their waists, pulling them skyward.

The Ballast Problem: Why You Can't Just "Hold It Down"

If the buoyancy force is so strong, why can't Jack and Will just push harder? Why can't they keep the boat pinned to the seafloor through sheer determination?

The answer comes down to force and mechanics. The buoyancy force doesn't originate from the boat itself. It's created by the pressure difference between the water below the boat and the water above it. The water underneath pushes up harder than the water above pushes down. The stronger this push, the harder it is for Jack and Will to resist it.

Imagine trying to hold a beach ball underwater. That's essentially what they're doing, except the beach ball is made of wood and the pressure underwater is far greater. At some point, your muscles give out. The beach ball wins.

The only way to keep the boat on the seafloor is to add negative buoyancy. You need the boat and crew combination to be heavier than the water they displace. You need ballast.

How much ballast? Remember, the buoyancy force is 6,600 pounds, and the boat plus crew weighs 650 to 850 pounds. You need an additional 5,750 to 6,000 pounds of weight. That's nearly 3 tons.

What's dense and portable? Gold is a good example. Gold has a density of about 19,300 kilograms per cubic meter, roughly 19 times denser than water. So to get 3 tons of additional weight, you'd only need about 345 pounds of gold. That's one small chest, maybe five or six large bars.

But here's the catch: carrying gold down to a beach in broad daylight while trying to escape is not exactly inconspicuous. The British Navy might notice. Also, gold is expensive, and I doubt Jack Sparrow had that kind of capital sitting around on the Black Pearl.

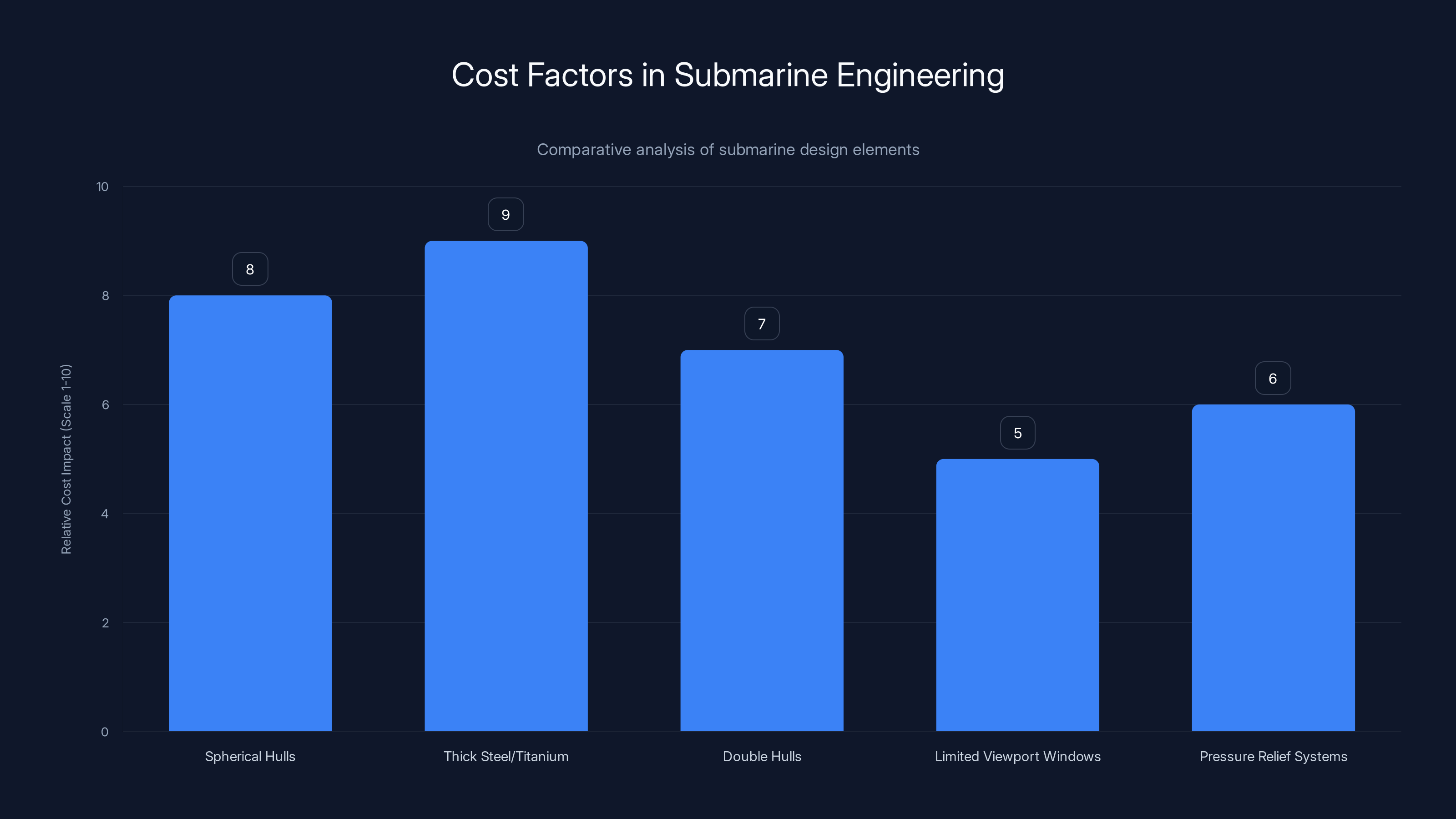

The chart highlights the relative cost impact of various submarine design elements. Thick steel or titanium and spherical hulls have the highest cost impact due to their material and manufacturing complexities. Estimated data.

What Happens to Air at Depth: The Ideal Gas Law

Now here's where the physics gets more interesting. As the boat descends deeper underwater, the pressure increases. And as pressure increases, the air inside the boat gets compressed. This reduces the volume of the air pocket, which reduces the buoyancy force.

Does this compression solve the problem? Does it reduce the buoyancy enough that the crew could stay on the seafloor without massive amounts of ballast?

To answer this, we need the ideal gas law: PV = n RT

Where:

- P is pressure

- V is volume

- n is the amount of gas (in moles)

- R is a constant (8.314 joules per mole-kelvin)

- T is absolute temperature

Assuming the amount of air trapped in the boat and the temperature both stay constant, we can simplify this to Boyle's Law: P₁V₁ = P₂V₂. In other words, pressure and volume are inversely proportional. When pressure increases, volume decreases by the same factor.

At the ocean surface, atmospheric pressure is 101,325 pascals (or about 14.7 pounds per square inch). Every 10 meters of seawater adds approximately another 100,000 pascals of pressure. So:

At 10 meters depth: Total pressure = 201,325 pascals, or roughly double atmospheric pressure

At 20 meters depth: Total pressure = 301,325 pascals, or roughly triple atmospheric pressure

At 30 meters depth: Total pressure = 401,325 pascals, or roughly quadruple atmospheric pressure

Applying Boyle's Law, if the boat starts at the surface with 3 cubic meters of air at 1 atmosphere of pressure, and descends to 30 meters where pressure is 4 atmospheres:

V₂ = (P₁ × V₁) / P₂ = (1 × 3) / 4 = 0.75 cubic meters

The air volume shrinks to just one-quarter of its original size. This dramatically reduces the buoyancy force. At 0.75 cubic meters:

New Buoyancy Force = 1,000 × 0.75 × 9.8 = 7,350 newtons, or about 1,650 pounds

This is an 8-fold reduction from the original 6,600 pounds. It's significant. But remember, the boat and crew still only weigh 650 to 850 pounds. The buoyancy force is still nearly double the weight. You'd still need roughly 1,000 pounds of additional ballast to achieve neutral buoyancy.

Pressure and the Human Body: Why Breathing Gets Harder

Let's assume Jack and Will somehow solved the buoyancy problem. They've loaded the boat with gold, they're descending slowly, and the air is compressing nicely. Can they actually breathe?

Yes, technically. The air inside the boat remains breathable because the air molecules are the same, just compressed together. Carbon dioxide is still carbon dioxide whether it's at 1 atmosphere or 4 atmospheres of pressure.

But there's a significant catch: as the air compresses, the partial pressure of oxygen increases. This creates a dangerous condition called oxygen toxicity. When the partial pressure of oxygen exceeds about 1.4 atmospheres, humans begin experiencing symptoms similar to nitrogen narcosis. Vision problems, tremors, twitching, and ultimately loss of consciousness can occur.

Let's do the math. At 30 meters depth (4 atmospheres total pressure), the partial pressure of oxygen is roughly 4 times whatever it was at the surface. Normal atmospheric air is about 21% oxygen. At the surface, the partial pressure of oxygen is 0.21 atmospheres. At 30 meters in a compressed air pocket, it becomes 0.21 × 4 = 0.84 atmospheres.

Okay, so at 30 meters, oxygen toxicity isn't an immediate threat. But go deeper. At 60 meters (7 atmospheres), the partial pressure becomes 0.21 × 7 = 1.47 atmospheres, which is right at the danger threshold. Beyond this depth, the crew would face serious physiological risks.

There's also the problem of carbon dioxide buildup. As Jack and Will breathe the air inside the boat, they produce carbon dioxide. The air gets progressively more toxic. At the surface in a closed room, you'd notice this pretty quickly. You'd start getting a headache, feeling foggy, and eventually pass out. Underwater, where you can't easily escape, this becomes life-threatening.

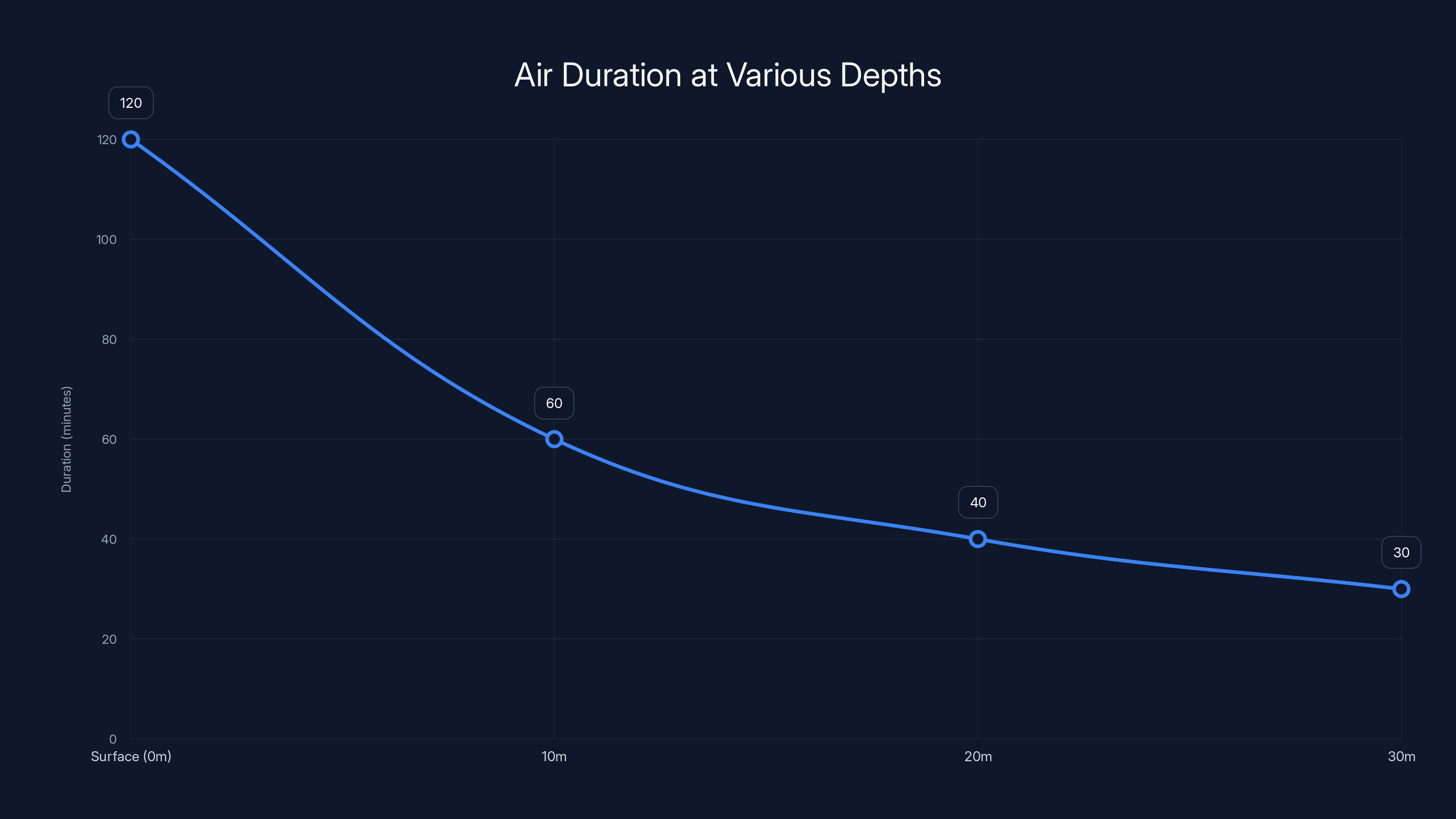

As depth increases, air volume decreases and buoyancy force reduces significantly due to increased pressure, following Boyle's Law.

The Duration Problem: How Long Can the Air Last?

Even if we ignore the compression and pressure issues, there's a simple fact: a finite amount of air only lasts so long when people are breathing it.

A human at rest breathes roughly 10 to 15 liters per minute. At moderate activity (like walking), this increases to 20 to 30 liters per minute. Let's assume Jack and Will are walking carefully on the seafloor at about 1 meter per second, so they're moderately active. Call it 25 liters per minute combined.

They have 3 cubic meters of air to start with, which equals 3,000 liters. At 25 liters per minute:

Duration = 3,000 liters / 25 liters per minute = 120 minutes

That's 2 hours. Sounds reasonable, right? Walk to the ship, climb aboard, retrieve the compass, get out. You could do it in 2 hours.

But wait. The boat is descending. The air is being compressed. At 10 meters depth with double the pressure, the volume shrinks to 1.5 cubic meters, or 1,500 liters. At 20 meters with triple pressure, it's down to 1,000 liters. At 30 meters with quadruple pressure, you have 750 liters left.

Worse, the effective volume keeps decreasing as they go deeper. And remember, the water around them is also denser at depth. The ambient water pressure means the human body is experiencing compression, which affects physiology in ways that increase oxygen consumption.

So your 2-hour window is really more like 45 minutes to an hour in practical terms. And that assumes they're not panicking, they're moving efficiently, and they don't encounter any complications.

The Structural Problem: Can the Boat Handle It?

Let's zoom out for a moment. We've been assuming the boat stays intact, the air stays contained, and everything holds together. But at depth, structural stress becomes significant.

Water pressure increases by about 1 atmosphere (101,325 pascals) for every 10 meters of descent. This pressure acts on every surface of the submerged boat. A rowboat isn't built to handle this kind of stress. The wooden hull would warp and crack. The seams would open up, letting water pour in. The frame would buckle.

Modern submarines can withstand crushing pressure because they're specifically designed for it. They have reinforced hulls, often spherical or cylindrical (shapes that distribute stress evenly), made from high-strength materials like steel or titanium. A wooden rowboat has none of these features.

At 10 meters depth, the pressure difference between inside and outside the boat is about 1 atmosphere (100,000 pascals). That's equivalent to about 2,000 pounds of force pushing inward on every square meter of hull surface. A typical rowboat hull might be 20 to 30 square meters. Do the math: you're looking at 40 to 60 million pounds of crushing force trying to collapse the boat.

It would hold for a few minutes, maybe. Then water would start leaking in. The air pocket would get smaller. The buoyancy would decrease. You'd sink faster. Soon you'd be underwater without any air at all.

As Jack and Will descend, the air duration decreases significantly due to increased pressure, reducing from 120 minutes at the surface to just 30 minutes at 30 meters depth. Estimated data based on typical conditions.

If You Actually Had to Do This: A Practical Solution

Let's say you absolutely had to walk along the seafloor with breathing apparatus similar to the movie's concept. What would you actually need?

For shallow depths (5 to 10 meters):

-

A reinforced air chamber made of steel or aluminum, not wood. Think more like a small submarine bell than a rowboat. It needs to handle pressure differentials without deforming.

-

Sufficient ballast to overcome buoyancy. For a 500-pound chamber, you'd need about 2 to 3 tons of additional weight. Distribute it around the chamber for stability.

-

Air supply that accounts for compression and consumption. Either bring extra compressed air, or rig up a line to surface-based pump that continuously supplies fresh air.

-

Exhaust management to remove carbon dioxide. Without this, you're breathing your own waste products. A simple chemical absorber (like calcium hydroxide) can work for a few hours.

-

Time limit of about 1 to 2 hours before oxygen toxicity, carbon dioxide buildup, or structural failure becomes critical.

For moderate depths (10 to 30 meters):

You'd need to add:

-

Nitrogen/oxygen adjustment if you stay long. Breathing compressed air at depth causes nitrogen narcosis. Professional divers use special gas mixtures with higher oxygen and added helium to mitigate this.

-

Decompression stops on the way up. If you've been at depth long enough, nitrogen dissolves into your tissues. Coming up too fast causes the nitrogen to form bubbles, leading to decompression sickness (the bends). Modern dive computers calculate safe ascent rates.

-

Multiple air reserves and emergency systems. If your primary air supply fails at 25 meters, you need a backup, or you could die before reaching the surface.

For anything deeper than 30 meters, you're basically building a submersible. At that point, you've moved far beyond the spirit of the original plan.

The Historical Context: Why This Scene Works

The Pirates of the Caribbean scene works because it's clever. The filmmakers found something that sounds impossible but feels like it could work, if you don't think too hard about it. Walk on the seafloor under a boat? Well, boats float. Air keeps you alive. Put them together and... maybe?

But it's also a scene that reveals what makes physical intuition so tricky. We have good instincts about weight and floating. We've stood in water and felt lighter. But buoyancy is counterintuitive. The force doesn't come from the boat or the air. It comes from the pressure of surrounding water. You can't overcome it with muscle strength alone.

Historically, deep-sea exploration didn't really become possible until we invented better technology. The diving bell, which works on a similar principle to the rowboat (air pocket trapped underground for breathing), dates back to the 1600s. The Jamaican scientist and engineer William Phips used diving bells in 1687 to salvage treasure from sunken ships near Hispaniola. He actually recovered significant amounts of gold and silver.

But even with a diving bell, staying underwater was limited. You needed to be relatively shallow (under 40 feet), and you could only stay down for 10 to 30 minutes before the air ran out or became too toxic. It wasn't until the 20th century, with scuba tanks and submarine technology, that deep-sea exploration became practical.

The Pirates scene is basically a 17th-century concept played out in 21st-century cinema. It's fun precisely because it's technically wrong but conceptually honest. It respects the physics enough to not have them just swimming through the water like fish, but it ignores the engineering realities that would make the thing actually work.

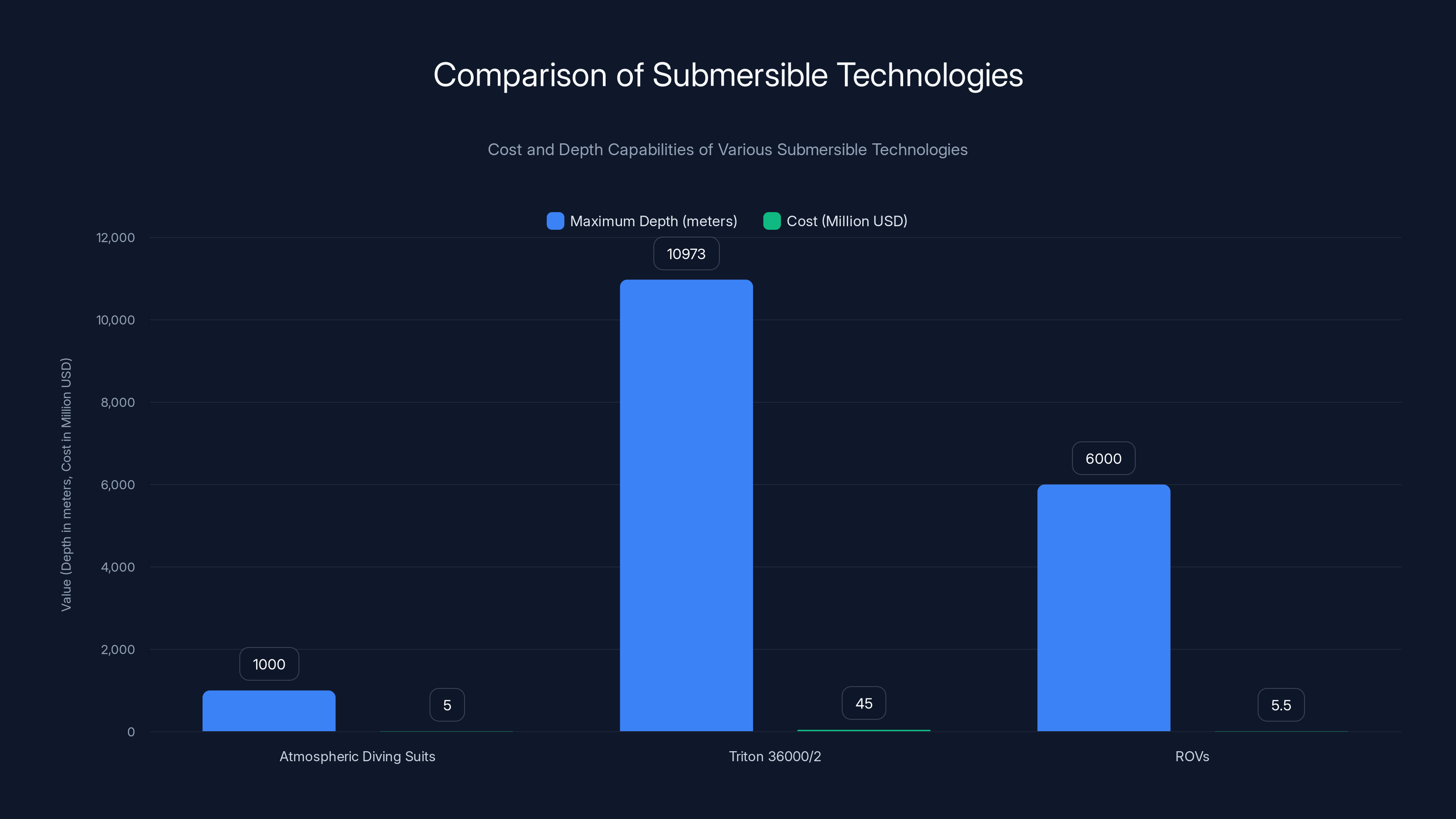

Atmospheric diving suits can reach depths of 1,000 meters at a cost of several million dollars. Triton 36000/2, capable of reaching 36,000 feet (10,973 meters), costs between

Comparing Real Submersible Technology

If you want to walk on the seafloor today, you have options. They're all expensive and far more sophisticated than a rowboat.

Atmospheric diving suits (ADS) are essentially one-person submarines. The pilot sits in a titanium sphere that maintains surface pressure (1 atmosphere) while the exterior experiences crushing ocean pressure. Mechanical arms allow manipulation. Depth: up to 1,000 meters. Cost: several million dollars.

Submersibles like the Triton 36000/2 can dive to 36,000 feet, reaching the deepest parts of the ocean. They're designed for three people, with reinforced titanium hulls, life support systems, and equipment bays. Cost:

ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) are robots controlled from the surface via cable. They don't need to keep anyone alive, just keep a camera and sensors working. Much cheaper (

All of these are orders of magnitude more complex than a wooden boat, because the ocean is extremely hostile to human life. Even air, it turns out, isn't enough.

Why Movies Get Physics Wrong (And Why It Matters)

Most movies get physics wrong. It's not because filmmakers are ignorant. It's because physics doesn't always make for good cinema. A scene where characters slowly descend in a titanium sphere, spend 20 minutes managing life support systems, and carefully decompress on the way up is accurate but boring. A scene where they walk across the seafloor under a boat is absurd but exciting.

The movie chose spectacle over accuracy. That's a legitimate creative choice. But understanding why it doesn't work teaches you something real. You learn about buoyancy, pressure, gases, and the forces that govern fluid mechanics. You learn why submarines are built the way they are. You learn that the ocean isn't just wet—it's physically hostile in ways you might not have considered.

Physics is everywhere. It's not just in textbooks or laboratories. It's in movies, in engineering failures, in everyday situations. Developing intuition about how the physical world works makes you better at understanding why things are designed the way they are, what could go wrong, and what creative solutions might actually work.

Jack Sparrow's underwater stroll won't work. But the fact that you now understand why makes you smarter than you were five minutes ago.

Common Misconceptions About Underwater Breathing

People often think that underwater breathing is only a problem because of air supply. Run out of air, and you're in trouble. But there are actually multiple problems, and they compound in interesting ways.

Misconception 1: You just need air, regardless of depth.

False. The composition and density of the air matter. At extreme depths, even breathing "normal" air causes nitrogen narcosis. Divers call it being "drunk on nitrogen." The deeper you go, the worse it gets. Below about 40 meters on regular air, most people lose the ability to think clearly and make safe decisions.

Misconception 2: The body naturally adjusts to pressure over time.

Partially true. Your body can equalize the pressure in air spaces (like your ears and sinuses) if you do it slowly. But your tissues themselves can't adjust. Nitrogen dissolves into your bloodstream and tissues at depth. The deeper you go and the longer you stay, the more nitrogen accumulates. When you ascend, that nitrogen comes back out of solution. If you ascend too fast, it forms bubbles that block blood vessels and nerves, causing decompression sickness.

Misconception 3: Oxygen is oxygen. It doesn't matter how much pressure.

Wrong. The physiological effect of oxygen depends on its partial pressure, not just its percentage. At depth, the same percentage of oxygen in your air becomes physiologically much more potent. Too much oxygen at depth causes oxygen toxicity, which can trigger convulsions and loss of consciousness. Too little causes hypoxia. It's a narrow window.

Misconception 4: You can train your body to handle anything.

No. There are hard physical limits. The human body is about 60 percent water. At extreme depths, even the water inside your cells experiences crushing pressure. There's a theoretical limit called the "limit of deep diving" beyond which the human body simply cannot function, no matter how trained. Most estimates put this around 300 to 400 meters.

The Science of Why Pressure Increases With Depth

We've mentioned that pressure increases by about 1 atmosphere every 10 meters of depth. But why? Why is the relationship linear?

The answer is simple: water has weight. The pressure at any depth is the sum of the atmospheric pressure at the surface plus the weight of all the water above pushing down.

Mathematically: P = P_atm + ρ × g × h

Where:

- P is total pressure

- P_atm is atmospheric pressure at the surface (101,325 pascals)

- ρ is water density (1,000 kg/m³)

- g is gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s²)

- h is depth in meters

Let's apply this:

At 10 meters: P = 101,325 + (1,000 × 9.8 × 10) = 101,325 + 98,000 = 199,325 pascals (approximately 2 atmospheres)

At 20 meters: P = 101,325 + (1,000 × 9.8 × 20) = 101,325 + 196,000 = 297,325 pascals (approximately 3 atmospheres)

At 30 meters: P = 101,325 + (1,000 × 9.8 × 30) = 101,325 + 294,000 = 395,325 pascals (approximately 4 atmospheres)

The relationship is linear: for every additional meter, you gain about 9,800 pascals of pressure. For every 10 meters, you gain roughly one additional atmosphere.

This linear relationship is one of the things that makes underwater physics relatively predictable. You can calculate exactly what pressure you'll experience at any given depth. But it also means that as you go deeper, the forces increase relentlessly. There's no flattening out, no point where pressure plateaus. It just keeps increasing.

Real-World Consequences: Why Submarines Are Expensive

All of this pressure creates massive engineering challenges. Submarines have to resist crushing forces that would crumple a car like aluminum foil. The solutions are expensive and sophisticated.

Spherical hulls: The strongest shape to resist pressure. Stress is distributed evenly. But spheres are hard to manufacture and take up a lot of internal space.

Thick steel or titanium: Both materials can withstand high pressure, but they're expensive and add weight. Titanium is lighter than steel but costs 5 to 10 times more.

Double hulls: Some submarines have two complete hulls, one inside the other. The space between can be flooded in emergency or used for additional compartments. But you're essentially building two submarines to get the benefits of one.

Limited viewport windows: Reinforcing a large window to withstand crushing pressure is extremely difficult. Most submarines have minimal windows and rely on cameras and sonar instead.

Pressure relief systems: If the pressure differential exceeds the hull's design limit, the entire structure fails catastrophically. Submarines use sophisticated systems to ensure pressure never gets that high, often by controlling ballast water very carefully.

All of this explains why a oceangoing submarine costs

The Psychology of Depth: How Fear Affects Thinking

There's one more factor we haven't discussed: human psychology. The ocean at depth is frightening. Water over your head, pressure all around, darkness below, no immediate escape route. Fear changes how you think.

Divers talk about "rapture of the deep," the intoxication-like state caused by nitrogen narcosis at depth. But there's also panic and anxiety. If something goes wrong underwater, you can't just take a step back and reassess. You can't call for help easily. You can't move quickly in any direction without risking decompression sickness on the way up.

In the Pirates scene, Jack and Will are calm and methodical. In reality, walking the seafloor under a rowboat—assuming all the physics problems were solved—would be terrifying. You'd be experiencing nitrogen narcosis, you'd be aware that your air supply is limited, you'd hear the creaks and groans of the wooden boat around you, and you'd be one mistake away from drowning.

Human fear is a powerful motivator for good engineering design. We build submersibles to keep people calm and safe because panic underwater is deadly. The safest submarines put the crew in a pressurized cabin, not in a compartment where they're exposed to the surrounding environment. The moment you start feeling the pressure, the moment you know things could go wrong at any second, your decision-making degrades.

So, Could You Actually Do This?

Let's come back to the original question. Could you walk on the seafloor under an upside-down rowboat like Jack Sparrow?

The short answer: no. Absolutely not. Not without solving multiple engineering problems, and even then, only in shallow water for short periods.

The problems, in order of severity:

-

Buoyancy is too strong. The rowboat and its air pocket create an upward force of about 6,600 pounds. You'd need 3+ tons of ballast just to stay on the bottom. And you can't just strap it to the boat. You need it to hang below you somehow, which introduces new complications.

-

Pressure crushes the boat. A wooden hull can't withstand the pressure at even shallow depths. You'd need a reinforced steel or aluminum vessel, essentially a small submarine. That's not a rowboat anymore.

-

Air runs out quickly. You have 2 hours of air at most, probably closer to 45 minutes in any meaningful sense. And that's assuming you're not going deep, not getting anxious, and not making any extra effort.

-

Pressure changes the air composition. Compressed air at depth causes nitrogen narcosis, oxygen toxicity, and carbon dioxide buildup. You can't just breathe normally.

-

You need to decompress slowly. If you stay at depth long enough, you can't just swim up to the surface. You need to make decompression stops, taking 10 minutes to hours depending on depth and duration. Get this wrong and you develop the bends, which is agonizing and potentially fatal.

Could you theoretically do something similar with modern submersible technology? Absolutely. Could you spend a few hours walking around the seafloor? Yes, if you had a $50 million submarine and a crew of trained professionals.

But could you take a rowboat, flip it upside down, trap some air, and stroll across the ocean floor to escape the British Navy? No. The movie got it wonderfully wrong.

And honestly? That's fine. Movies don't need to be scientifically accurate. But understanding why this particular scenario fails teaches you something real about how the physical world works. It teaches you that buoyancy is powerful, that pressure is relentless, and that the ocean is not a forgiving environment. It teaches you why submarines are built the way they are, why deep-sea exploration is so expensive and difficult, and why drowning is one of those dangers that's still genuinely dangerous even with modern technology.

Jack Sparrow is clever. But he's not clever enough to beat physics.

FAQ

Can air really hold you up underwater?

Yes, air creates upward buoyancy force because it's much less dense than water. However, the force is so powerful—6,600 pounds for a 3-cubic-meter air pocket—that it's nearly impossible to stay submerged without adding tons of ballast weight. Buoyancy isn't something you can overcome through determination alone.

What's the maximum depth a person can safely dive?

Recreational scuba divers typically don't go deeper than 40 meters due to nitrogen narcosis and oxygen toxicity. Technical divers with special training and gas mixtures can reach 100+ meters, but most diving deaths occur below 40 meters. The theoretical absolute limit for humans is around 300 to 400 meters, but that's in very specialized circumstances.

How quickly does water pressure increase as you go deeper?

Water pressure increases by approximately 1 atmosphere (101,325 pascals or 14.7 pounds per square inch) for every 10 meters of descent. This linear relationship means you can calculate the pressure at any depth using the formula P = P_atm + ρgh. At 30 meters, you're experiencing about 4 atmospheres of pressure.

Why does air compress underwater, and how much does it compress?

Air compresses due to Boyle's Law: as pressure increases, volume decreases proportionally (assuming temperature stays constant). At 30 meters depth where pressure is 4 atmospheres, a 3-cubic-meter air pocket compresses to 0.75 cubic meters—a 75% reduction in volume. This dramatically reduces buoyancy but also reduces breathing duration.

What is nitrogen narcosis, and when does it become dangerous?

Nitrogen narcosis is an intoxication-like state caused by breathing nitrogen at high pressures. It begins noticeably around 30 to 40 meters depth and becomes increasingly severe deeper. Symptoms include difficulty thinking clearly, euphoria or anxiety, tremors, and impaired judgment. Below 40 meters on regular compressed air, most divers experience significant cognitive impairment.

How do professional divers stay safe at depth?

Professional divers use multiple safety measures: special gas mixtures (like nitrox or trimix) to manage nitrogen and oxygen effects, strict depth limits based on their training, dive computers to track time and decompression requirements, and gradual ascent with decompression stops. They also use the buddy system and maintain constant communication. Even with all these precautions, deep diving remains inherently risky.

Could modern technology make the rowboat scene actually work?

Theoretically yes, but you'd need to replace the rowboat with a reinforced submarine hull (steel or aluminum, not wood), add thousands of pounds of ballast to overcome buoyancy, implement a sophisticated life support system to manage air quality and decompression, and operate at shallow depths (probably under 20 meters). At that point, you've spent millions of dollars and no longer have a rowboat—you have a submersible.

Why is decompression required when diving?

Decompression is required because nitrogen dissolves into your tissues and bloodstream at high pressures. If you ascend too quickly, the nitrogen comes out of solution too fast, forming bubbles in your blood vessels and tissues. These bubbles can block blood flow and cause decompression sickness (the bends), which is painful and potentially fatal. Slow ascent with decompression stops allows the nitrogen to harmlessly exit your system.

What's the deepest a person has ever dived?

The deepest scuba dive is around 332 meters, performed by Ahmed Gabr in 2014 using special equipment and gases. However, this took extraordinary precautions and involved extreme risk. For practical purposes, the deepest humans regularly work is around 300 meters in specialized saturation diving operations for offshore oil and gas work. Beyond that, the physics and physiology become nearly impossible to manage.

Can you train your body to handle extreme depth?

No. While training improves technique, decision-making, and safety practices, there are hard physical limits based on human physiology. Even the most experienced divers can't overcome nitrogen narcosis at very deep depths, oxygen toxicity with compressed air, or the crushing pressure itself. Every diver, no matter how trained, has a depth limit beyond which the human body simply cannot function.

Why are submarines so expensive?

Submarine cost comes from the engineering required to withstand crushing pressure. Hulls must be made of expensive materials like titanium or high-strength steel, reinforced to withstand forces that would crumple ordinary structures. Multiple redundant systems ensure safety. Life support systems must continuously manage oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. Navigation, propulsion, and communication systems add further complexity. You're not paying for size; you're paying for sophisticated engineering that keeps people alive in an environment actively hostile to human life.

Final Thoughts: The Intersection of Physics and Storytelling

The Pirates of the Caribbean rowboat scene endures because it perfectly captures the intersection of physics and imagination. It asks a question that sounds plausible on the surface but fails under scrutiny. It's exactly the kind of question that makes physics fun.

The real world has limitations. The ocean has limitations. Air has properties. Water has properties. These properties create rules, and those rules are what we call physics. Sometimes those rules enable amazing things, like modern submarines that can reach the deepest parts of the ocean. Sometimes they create barriers, like the impossible buoyancy force of an air pocket underwater.

But understanding these rules doesn't diminish the wonder of the world. If anything, it enhances it. Knowing why submarines are designed the way they are makes them more impressive, not less. Understanding the forces at work helps you appreciate the engineering cleverness of the solutions.

So could you walk on the seafloor under a rowboat like Jack Sparrow? No. But now you know exactly why, and that knowledge is more valuable than any cinematic fantasy.

Key Takeaways

- A 3-cubic-meter rowboat generates 6,600 pounds of buoyancy force, far exceeding its 850-pound weight, making it impossible to stay submerged without 3+ tons of ballast

- Water pressure increases by 1 atmosphere every 10 meters of depth, creating crushing forces that would collapse a wooden boat long before reaching significant depth

- Compressed air at depth causes nitrogen narcosis, oxygen toxicity, and carbon dioxide buildup—breathing under a boat gets progressively more dangerous the deeper you go

- Modern submarines solve these problems through reinforced titanium hulls, sophisticated life support systems, and cost millions of dollars because the ocean is fundamentally hostile to human presence

- Understanding why this movie scenario fails teaches genuine physics principles: buoyancy, hydrostatic pressure, the ideal gas law, and human physiological limits underwater

Related Articles

- Best Video Games of 2025: Complete Rankings & Reviews [2025]

- Sleep Number P6 Smart Bed Review: Full Analysis [2025]

- How Global Trade Power Is Shifting: The Tariff War's Hidden Weapon [2025]

- Trump's Mass Deportation Machine: How Federal Law Enforcement Replaced Militias [2025]

- Plants vs. Zombies: Replanted Review [2025]

- HP ZBook 8 G1i 14-Inch Review: Is This Workstation Worth It? [2025]

![Could You Walk on the Seafloor With an Upside-Down Rowboat? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/could-you-walk-on-the-seafloor-with-an-upside-down-rowboat-2/image-1-1766752666650.jpg)