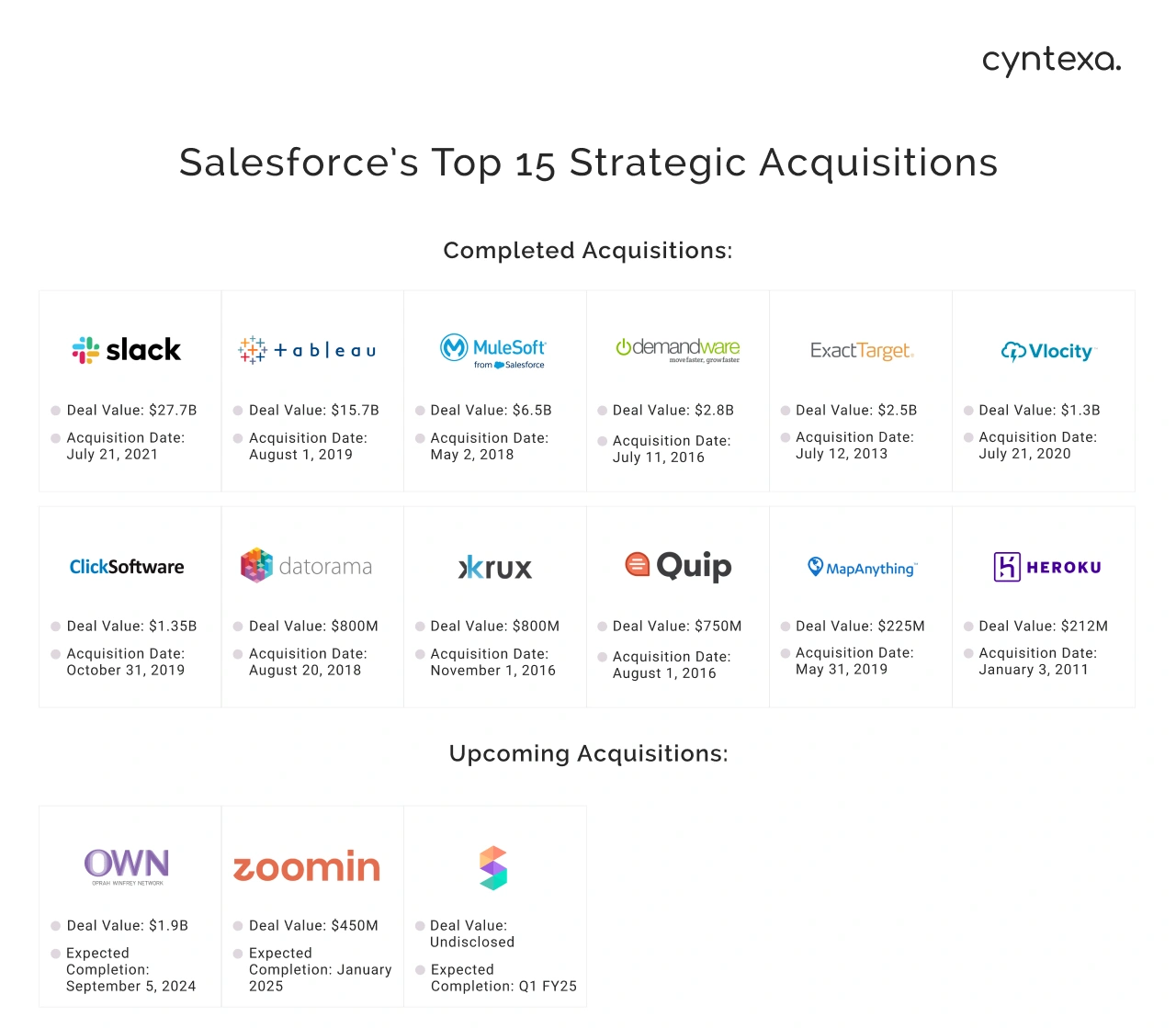

Own's $2B Salesforce Acquisition: The Complete Strategy & Lessons for SaaS Founders

Introduction: From "Dumbest Idea" to Billion-Dollar Exit

In 2008, a software entrepreneur named Sam Gutmann sat in a board meeting for his first company and heard an idea that made him stop the meeting cold. A venture investor had written on the whiteboard: "Backup for Salesforce." Sam's reaction was immediate and dismissive: "That's the dumbest idea I've ever heard."

Six years later, Sam Gutmann would become the CEO of that exact company—Own—and lead it to a $2 billion acquisition by Salesforce, one of the largest software acquisitions in history. This remarkable pivot from skeptic to architect of a category-defining business reveals profound insights about market timing, founder conviction, product focus, and the often-counterintuitive decisions that separate billion-dollar companies from cautionary tales.

The Own acquisition represents far more than a successful exit. It's a masterclass in disciplined growth, strategic focus, and the willingness to abandon initial beliefs when market data tells a different story. In an era where SaaS founders are constantly pressured to expand features, chase adjacent markets, and scale aggressively, Own's path to $2 billion success stands in stark contrast—built on saying "no" more often than saying "yes."

This comprehensive analysis explores the strategic decisions, leadership principles, and execution frameworks that transformed Own from a "stupid idea" into a market-dominating platform that Salesforce valued at two billion dollars. Whether you're building a SaaS company, leading a critical infrastructure business, or navigating the complex decisions around product expansion, Own's journey offers actionable lessons that transcend the backup software space.

The story begins not in Silicon Valley boardrooms or venture capital pitch meetings, but in an unexpected place: a coffee shop in Herzliya, Israel, where chance encounters and genuine listening would set the stage for a decade-long company-building journey.

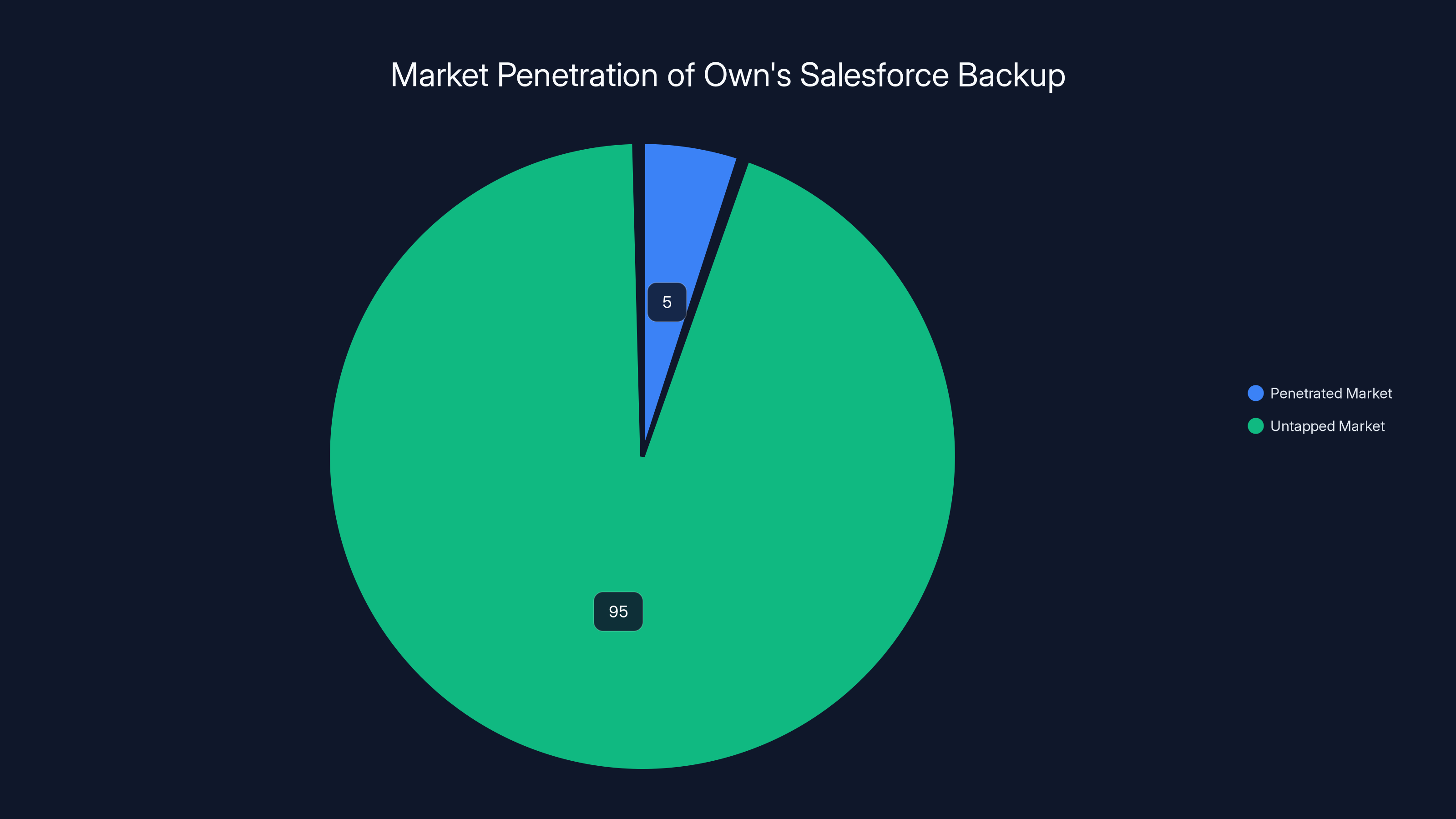

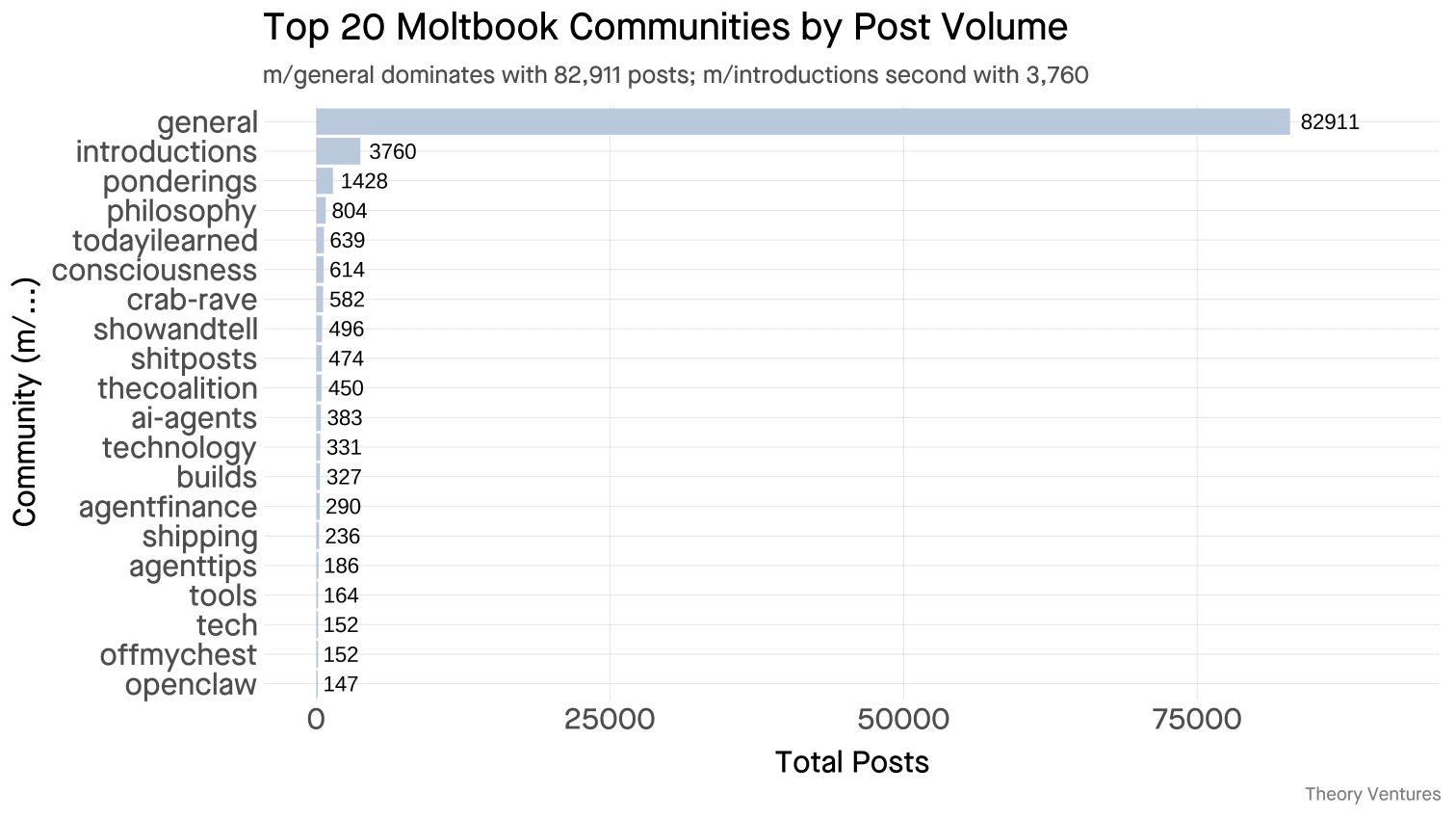

Estimated data shows that Own's Salesforce backup had only penetrated 5% of its potential market, leaving a vast 95% untapped, justifying the focus on Salesforce over other platforms.

The Unexpected Beginning: A Coffee Shop That Changed Everything

The Chance Encounter in Israel

Sam Gutmann's path to Own began with no intention whatsoever of starting a backup company. In 2014, Gutmann was on vacation in Israel with zero professional network in the country. He had already built one company and wanted to explore new opportunities, but he had no specific business plan or market thesis driving his travels.

While in Israel, Gutmann reconnected with a former colleague—a person who had worked at a venture fund that previously invested in Gutmann's first company. This colleague had left venture capital, traveled the world, and recently landed in Israel, where he was now job hunting. The two decided to grab a beer and catch up. During their conversation, the colleague mentioned an unofficial job interview coming up: "I'm meeting with two guys who started a backup company. Want to tag along?"

It was a casual invitation on a vacation day. No grand vision. No strategic plan. Just a chance to network and explore what was happening in the Israeli startup ecosystem. Gutmann agreed, and they drove to a city called Herzliya that Gutmann had never heard of.

The Founders' Clarity (and Ruthlessness)

When they arrived at the coffee shop, Gutmann met two founders: Ariel, the founding CTO, and his co-founder. The meeting that followed would set the trajectory for the next decade. But what makes this moment remarkable was not what the founders wanted from Gutmann—it was what they explicitly didn't want.

Midway through the conversation, the founders turned to Gutmann's colleague—the person who had come to interview for a job—and said something that was brutally honest: "Please stop selling yourself. We're not hiring a sales guy."

Then they turned to Gutmann, whom they'd just met: "We actually are hiring a CEO. Are you interested?"

This moment reveals an important principle that would define Own's entire trajectory: clarity of need and ruthless honesty about what the company required. The founders didn't hire based on resume polish, network, or conventional startup wisdom. They hired because they had diagnosed a critical gap—they needed a CEO—and they had just met someone who fit that need.

Gutmann, stunned by the directness, agreed to explore the opportunity. That one-hour coffee meeting on a vacation ruined the rest of his planned time off. But ten years later, when Salesforce acquired Own for $2 billion, that coffee shop conversation proved to be one of the most consequential meetings in SaaS history.

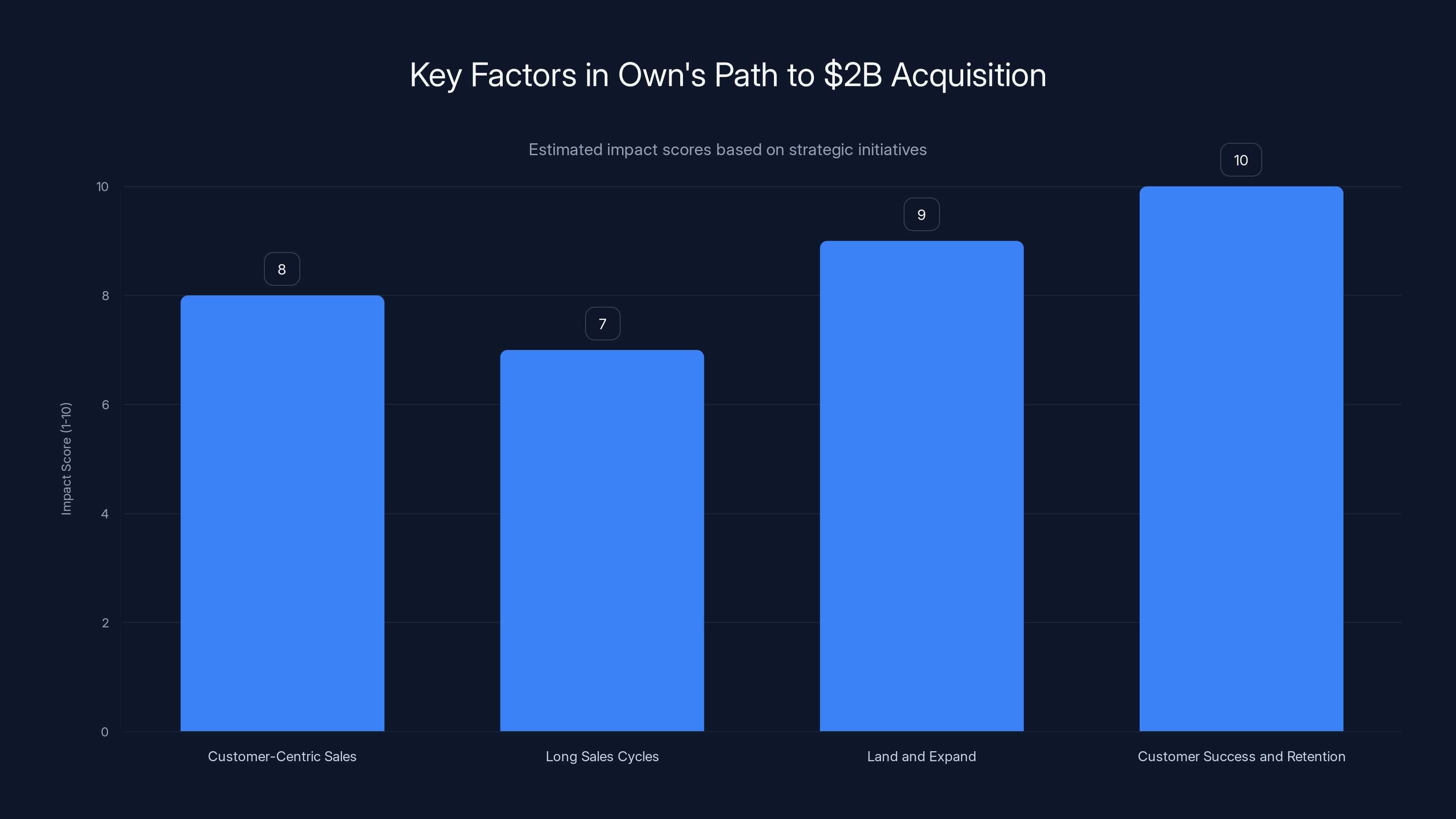

Customer success and retention had the highest impact on Own's path to a $2B acquisition, followed closely by the 'Land and Expand' strategy. (Estimated data)

The Irony: How Skepticism Became Conviction

The 2008 Board Meeting That Changed Everything

The most important aspect of Own's origin story isn't that the company was founded to solve backup for Salesforce. It's that Sam Gutmann, the person who would build that company, initially thought it was a terrible idea.

In 2008, six years before joining Own, Gutmann was serving on a board for his first company—an online backup service. The company helped individuals and businesses back up their data to the cloud using encrypted servers. It was a legitimate business addressing a real problem in the pre-cloud era.

During a growth strategy meeting, the board chairman walked up to a whiteboard and wrote in red marker: "Backup for Salesforce." The idea was simple: if backup was valuable for general data (email, documents, files), shouldn't it be equally valuable for Salesforce data?

Gutmann's immediate reaction was dismissive. He stopped the meeting and declared: "That's the dumbest idea I've ever heard."

Why was his reaction so negative? Several factors contributed to his initial skepticism:

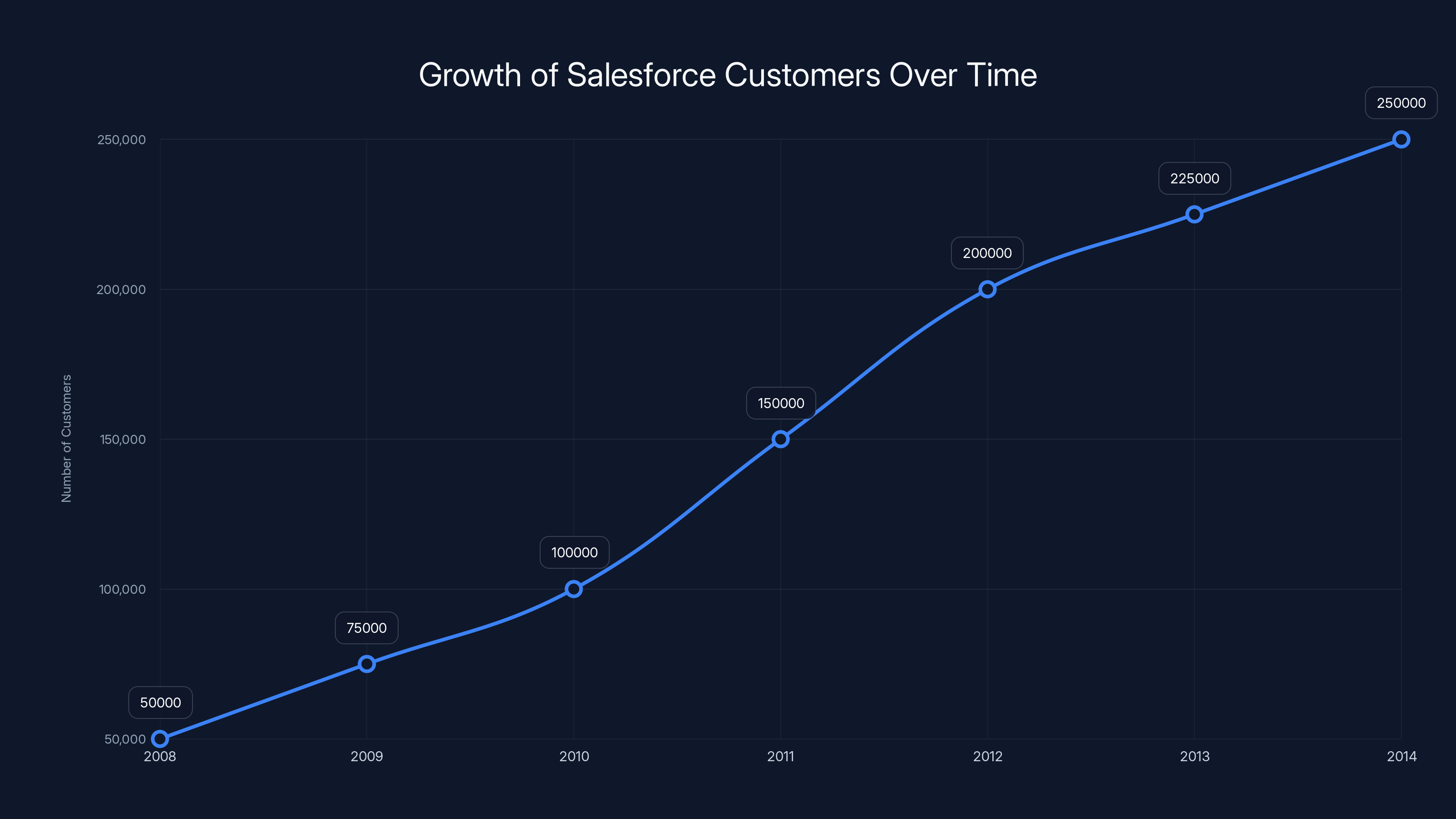

Market Size Uncertainty: In 2008, Salesforce had roughly 50,000 customers. While a growing number, it seemed like a niche market compared to the broader backup space.

Assumption of Platform Reliability: Conventional wisdom suggested that Salesforce, as a major platform provider, would handle data protection. Why would customers need a separate backup solution?

Perceived Feature Bloat: Backup might seem like a checkbox feature, not a standalone business.

Execution Complexity: Building backup specifically for Salesforce required deep technical integration and ongoing maintenance as Salesforce evolved its platform.

The Data That Changed His Mind

Six years later, when Gutmann actually met the Own founders, something fundamental had shifted in the market landscape. It wasn't that Salesforce became a bigger platform (though it did). It was that Gutmann had accumulated enough data and pattern recognition to overturn his initial dismissal.

The key insights that changed his mind:

Scale of Salesforce Adoption: By 2014, Salesforce had grown to approximately 250,000 customers, and the growth trajectory was accelerating. This wasn't a niche anymore—it was a major enterprise software category.

Shared Responsibility Models: All cloud providers, including Salesforce, explicitly stated in their terms of service that users bore responsibility for their own data protection. Platform vendors handled infrastructure. Users handled their own backup and disaster recovery strategy.

Enterprise Data Vulnerabilities: Beyond platform outages, Salesforce users faced increasingly sophisticated threats:

- Account takeovers and unauthorized access

- Malicious deletions by compromised accounts

- Data corruption from misconfigurations

- Permanent deletion requests that couldn't be undone

- Ransomware attacks targeting SaaS applications

The 300+ Application Problem: Gutmann recognized that most enterprises don't use just Salesforce. They use 300+ SaaS applications on average. Each application represents the same vulnerability—data that the user is responsible for protecting, but the platform vendor is responsible for securing the infrastructure.

Gutmann now saw the pattern clearly. The question wasn't "Is backup necessary for Salesforce?" but rather "Why wouldn't every Salesforce customer have a data protection strategy?"

He compared it to an apartment building analogy: the landlord maintains the building's infrastructure, structural integrity, windows, pipes, and elevator systems. But residents are responsible for everything inside their unit—furniture, electronics, personal items. If you lost everything in your apartment, the landlord's insurance wouldn't cover your losses. You need your own renter's insurance.

This shift from dismissal to conviction highlights a critical success factor in Own's journey: the founder's willingness to update his views when market data changed. Gutmann didn't cling to his 2008 opinion. He recognized that his "priors"—his initial beliefs about the market—were wrong.

Product-Market Fit: How a Disaster Recovery Lab Became a Category Leader

Origins in Data Recovery

The founding story of Own reveals an interesting paradox in SaaS businesses: the best companies often start by solving a problem that already exists in the physical world, then adapt that solution to the digital era.

In the pre-cloud days, Ariel and his co-founder ran a traditional disaster recovery lab. This wasn't a software company—it was a physical operation. Customers would bring in water-damaged phones, hard drives with failed RAID arrays, corrupted databases, and other storage devices. The team would attempt to recover data using specialized equipment and techniques. It was skilled, labor-intensive work, and it solved a real problem for businesses that had lost critical information.

Around 2010, something fundamental began happening to their business. Customers started arriving with a new type of problem that the lab couldn't solve: data loss in the cloud.

A customer would say: "You recovered data from my server before. Now I've lost something in the cloud. Facebook shut down my business account permanently. Can you help?" Or: "I deleted an important Google Sheet by mistake and it's gone from my trash folder. Is there any way to recover it?"

The founders faced a hard truth: they had no way to help these customers. Unlike a physical hard drive, they didn't have access to Facebook's or Google's servers. They couldn't open up a cloud platform and recover deleted data. They were facing the limits of physical disaster recovery in an increasingly cloud-based world.

The Aha Moment: Cloud = New Vulnerability

These conversations were more than anecdotes—they represented a fundamental market shift. Every conversation was a data point indicating that:

- Cloud platforms were becoming critical to business operations

- Data loss in the cloud was a real problem

- Cloud platforms themselves couldn't recover that lost data

- There was no existing solution

Instead of viewing these conversations as failures, the founders recognized them as market validation. The fact that customers were asking for help meant they understood the problem. They just needed someone to solve it.

This recognition led to a critical decision: pivot from physical disaster recovery to digital data protection. Specifically, create backup solutions for the cloud platforms that were increasingly critical to business operations.

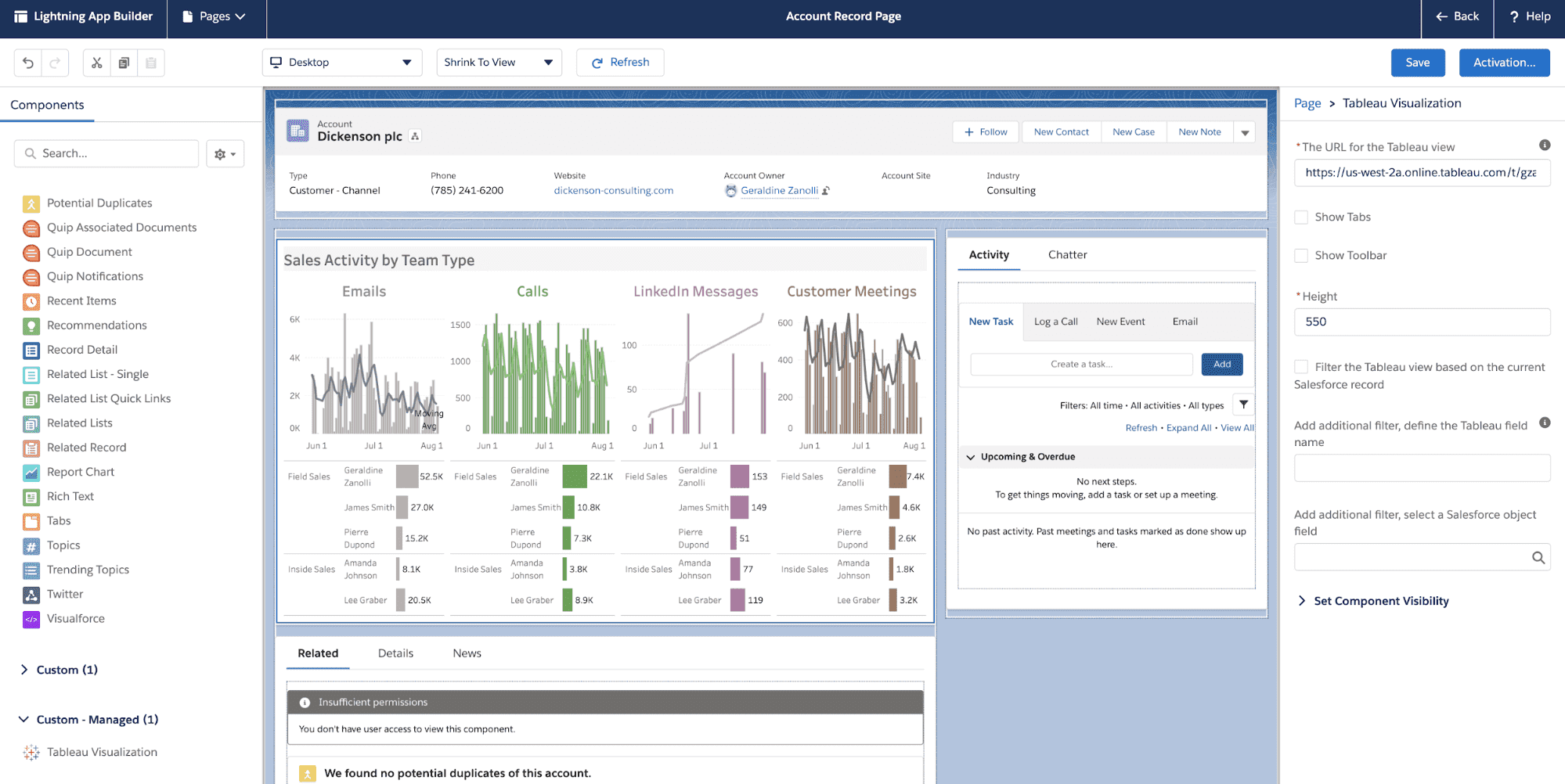

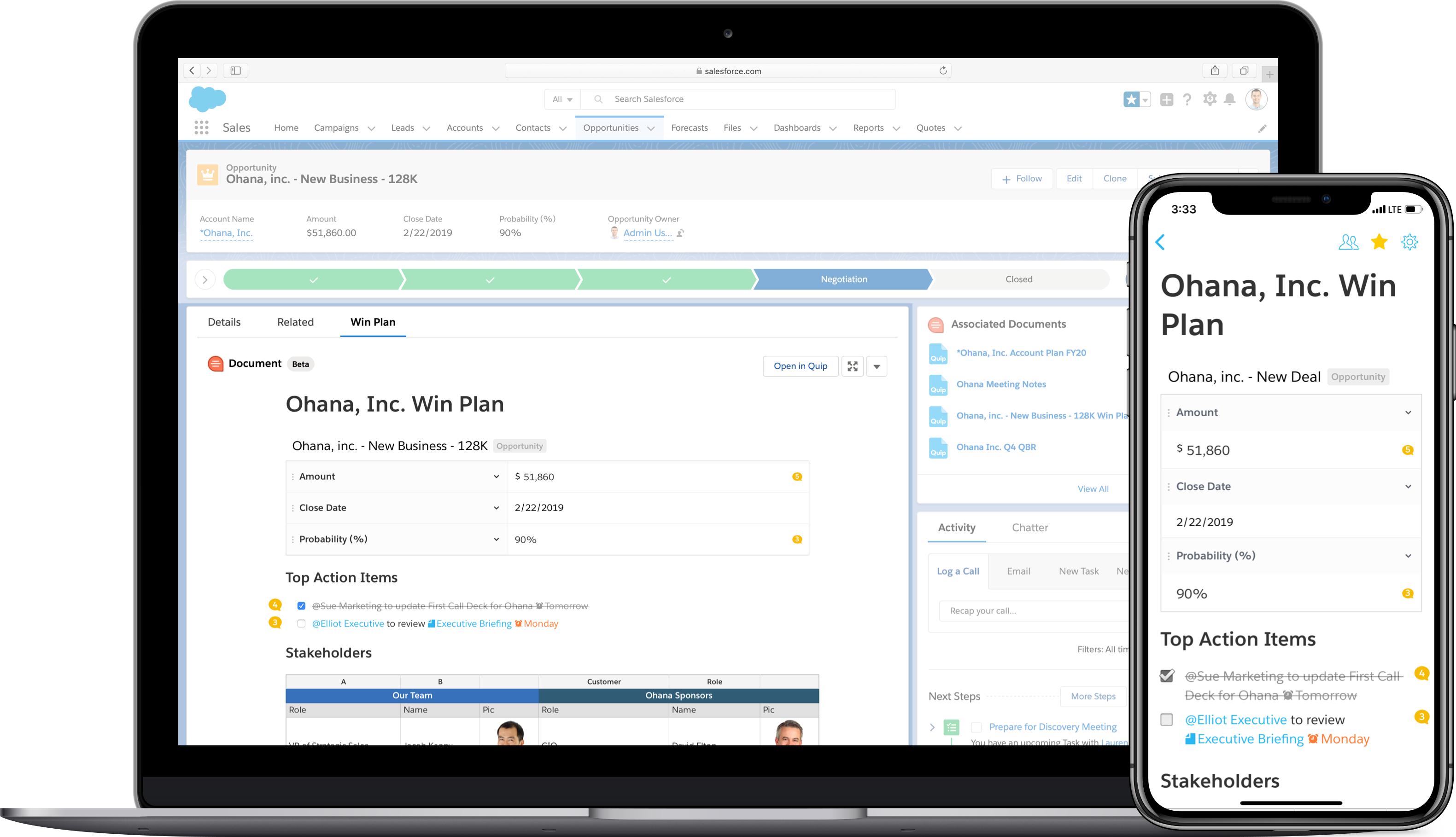

The founders began building a product to backup data from cloud SaaS applications. They started with Salesforce—the platform that would ultimately define Own's market position and growth trajectory. But they also explored backup solutions for ServiceNow, Microsoft 365, and other major platforms.

Salesforce customer base grew from 50,000 in 2008 to over 250,000 by 2014, highlighting significant market expansion. (Estimated data)

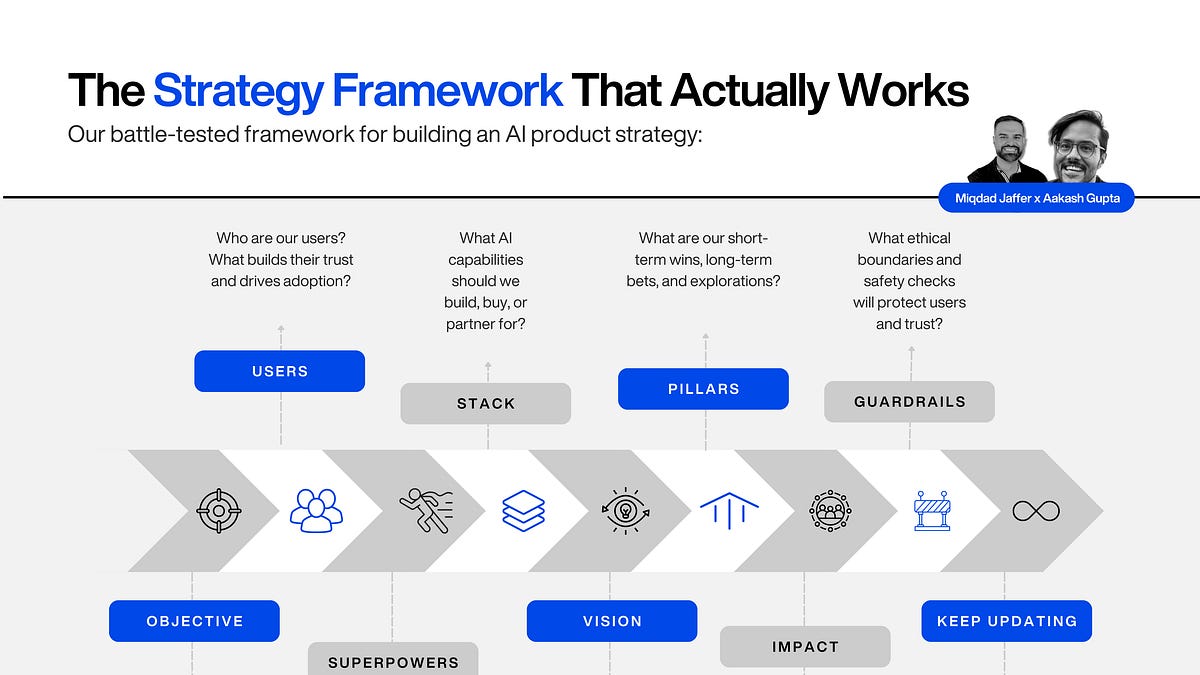

The Discipline That Defined Own: Saying No to Everything

Multi-Platform Readiness vs. Multi-Platform Launch

One of the most counterintuitive decisions in Own's growth strategy reveals a fundamental principle of SaaS success: premature expansion kills focus. By the time Own had been operating for a few years, the team had already developed backup solutions for multiple platforms. They had:

- Salesforce backup (the flagship product)

- ServiceNow backup (ready to launch)

- Microsoft 365 backup (developed and functional)

- Other enterprise platform backups (in various stages of completion)

These weren't prototypes or incomplete features. They were fully functional, revenue-ready products. The team had invested significant engineering resources in developing these solutions. From a feature portfolio perspective, Own was ready to announce itself as a multi-platform backup provider.

Then management made a decision that seems counterintuitive in retrospect, but proved to be one of the most strategically important choices in the company's history: they said no to launching all those other products. They killed the initiatives. They shut down the teams working on the non-Salesforce products. They made a conscious choice to keep Own focused on a single platform, despite having the technical capability to serve multiple markets.

Why make such a seemingly wasteful decision? The logic was rooted in a fundamental understanding of market penetration and execution depth:

Salesforce's market had barely been penetrated. Own had built the category, but the vast majority of Salesforce customers—we're talking about penetration rates in the single digits—didn't yet have backup solutions. The opportunity in front of Own was enormous and untapped. Why dilute the sales organization, engineering focus, and marketing effort across multiple platforms when the primary market (Salesforce) had so much room for growth?

This was the discipline of saying no. It would have been easy to say yes:

- Yes to ServiceNow backup (because they'd built it)

- Yes to Microsoft 365 backup (because the engineers had completed it)

- Yes to expanding into adjacent platforms (because the opportunity seemed obvious)

But every "yes" would have meant:

- Sales team splits across multiple products

- Marketing message dilution

- Engineering focus distributed across platform updates and integrations

- Customer success complexity multiplied

- Resource allocation across different platforms and their respective roadmaps

Instead, Own said no. They stayed laser-focused on Salesforce until they had reached a much deeper level of market penetration, built a war chest of resources, and could afford to truly execute on multi-platform offerings with the same level of excellence.

The $100M ARR Rule

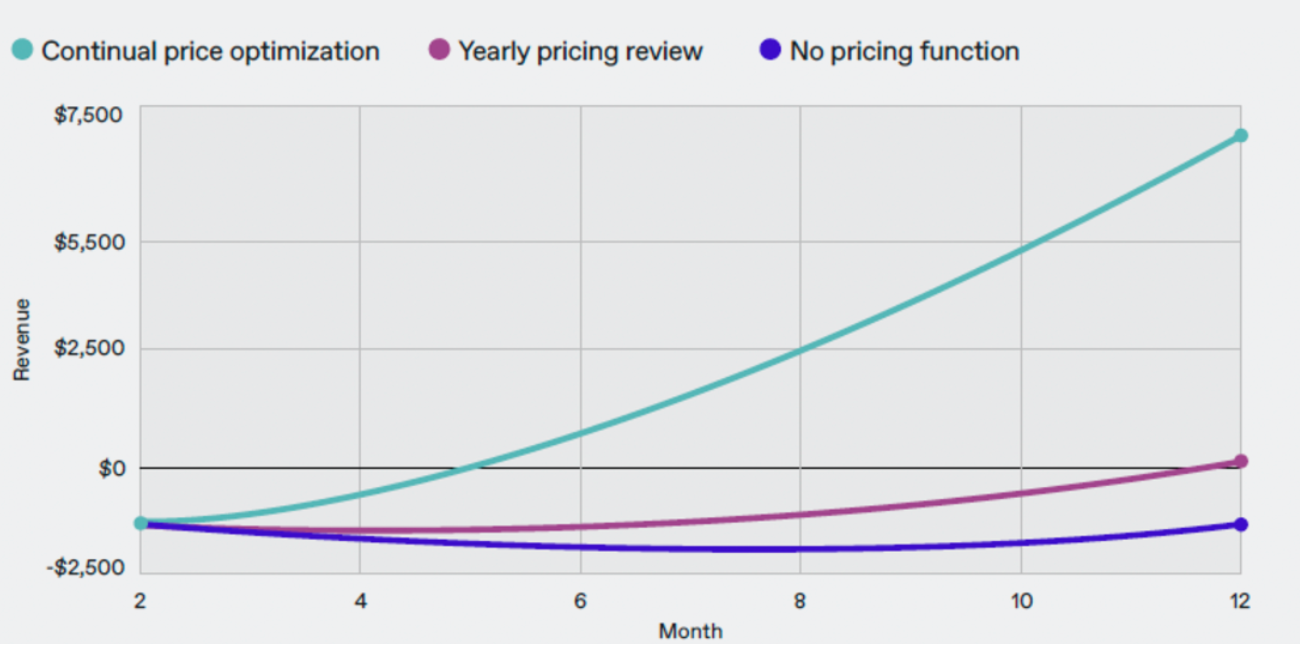

This discipline became formalized in a principle that Own adhered to religiously: don't expand into adjacent markets until your core market is single-digit penetrated AND you've reached $100M+ ARR.

The logic is mathematically sound. When a company is in an early-stage market with single-digit penetration, the opportunity within that market is typically so large that the opportunity cost of distraction is enormous. At Own, they calculated:

- Salesforce TAM (Total Addressable Market): Hundreds of thousands of potential customers

- Current penetration: Single digits

- Average deal value: Growing with customer size

- Expansion revenue potential: Significant (increasing backup volumes as customers' Salesforce instances grew)

Underneath these numbers was a fundamental principle: maximize the capture rate in an emerging category before the category becomes competitive. The first backup provider for Salesforce had an advantage that wouldn't last forever. As the category matured, competitors would arrive. The window to establish dominance was time-limited.

By the time Own finally did expand beyond Salesforce—acquiring competitors in other verticals, building native solutions for other platforms—they had built such a powerful brand, such a loyal customer base, such deep technical expertise, and such significant resources that entering adjacent markets wasn't starting from zero. They were extending dominance, not starting over.

Killing Products That Weren't Working

Focus meant something else too: the willingness to kill products, features, and initiatives that weren't generating revenue. In many SaaS companies, there's a bias toward hoarding features. Engineers build something, and even if it's not being used, there's resistance to removing it because "someone might use it someday" or "it was expensive to build."

Own had a different mentality. They would build features, launch them, measure adoption and revenue impact, and if the data showed that customers weren't paying for it or using it, Own would kill it. This wasn't framed as failure—it was framed as learning and optimization.

This pruning process served multiple purposes:

Reduces Technical Debt: Every feature maintained is a feature that must be updated, tested, and integrated with new platform versions. Killing unused features reduces the burden on engineering.

Clarifies Product Message: When your product is focused, customers understand what you do. Own does backup for Salesforce. That clarity is powerful in competitive markets.

Improves Unit Economics: Resources directed toward killing unused features are resources freed up to improve the core offering, support existing customers, or invest in sales and marketing.

Enables Faster Innovation: When the team isn't maintaining 10 different products, they can move faster on the core product.

The result of this discipline? Own achieved 100%+ annual growth rates throughout their trajectory to $2B acquisition. In the backup and disaster recovery space, these growth rates are extraordinary. They indicate a company that is capturing market share faster than the market is growing, with strong product-market fit and efficient go-to-market execution.

Financial Discipline: The CEO Who Ran His Own Financial Model

Manual Excel Models at Scale

One of the most surprising revelations about Own's execution comes from their approach to financial planning and analysis. When the company was growing rapidly—eventually reaching $200M ARR—you might expect them to have a sophisticated FP&A (Financial Planning and Analysis) department, with enterprise financial planning software, multiple analysts, and a complex reporting infrastructure.

Own did have all of that infrastructure available. An outsourced CFO firm approached management and offered a standard service: let our FP&A team manage your financial planning and analysis, freeing up your CEO to focus on business strategy.

This offer was sensible on its face. Modern CFO firms are professional, experienced, and handle this kind of work for hundreds of companies. It's a standard practice in scaling organizations.

Sam Gutmann said no.

Instead, Sam continued to personally run the financial model himself, in Excel, until the company reached $200M+ ARR. Every investment in the company—every hire, every software purchase, every marketing campaign—traced back to a specific cell in Sam's Excel model. When the finance team wanted to recommend an investment, they didn't need to write a proposal. They needed to show how it impacted the Excel model and the financial projections.

This personal involvement had profound consequences.

The Financial Precision That Drives Accuracy

The outsourced CFO firm had worked with hundreds of SaaS companies. After a year of working with Own, they told Sam something remarkable: "You're the only founder where our FP&A team isn't doing this for you. You're also the only company actually making their numbers."

Think about what this statement implies. The finance firm had direct experience with many companies' financial performance. In the typical SaaS company, the financial projections the team makes—the revenue targets, cost assumptions, and growth rates they forecast—often don't match reality. Companies miss guidance or have to revise projections downward.

But Own consistently hit their financial targets.

Why? The hypothesis: when the CEO is personally responsible for maintaining the financial model, the rigor required to keep that model accurate translates into more accurate business execution. The CEO can't lie to themselves about whether an initiative is hitting its targets because they have to update the cells in the Excel model themselves.

This creates several dynamics:

Allocation Accountability: When every dollar is mapped to a cell in the model, it's harder to spend money on low-impact initiatives. The model forces visibility into ROI.

Early Warning System: As the CEO updates the model monthly, quarterly, or as deals close, trends become visible much faster than in a typical financial reporting structure. If a product line isn't hitting targets, the CEO knows immediately.

Disciplined Trade-Offs: When the CEO understands how each investment impacts overall financial trajectory, decisions about where to allocate resources become more disciplined.

Communication Clarity: The CEO can discuss financial strategy not as abstract concepts but as concrete numbers in the model. This creates shared understanding across the organization.

Scaling the Model

It's worth noting that Gutmann didn't maintain this approach forever. At some point, as the company scaled further, the manual Excel model became less practical. But by that point, Own had built a financial culture where accuracy was valued, where investments were tied to outcomes, and where financial discipline was embedded in decision-making.

This approach illustrates a broader principle in startup finance: the financial model is not just a planning tool, it's a strategic document that shapes how you think about your business. When the CEO is deeply connected to the financial model, the model becomes more than projections—it becomes the framework for decision-making.

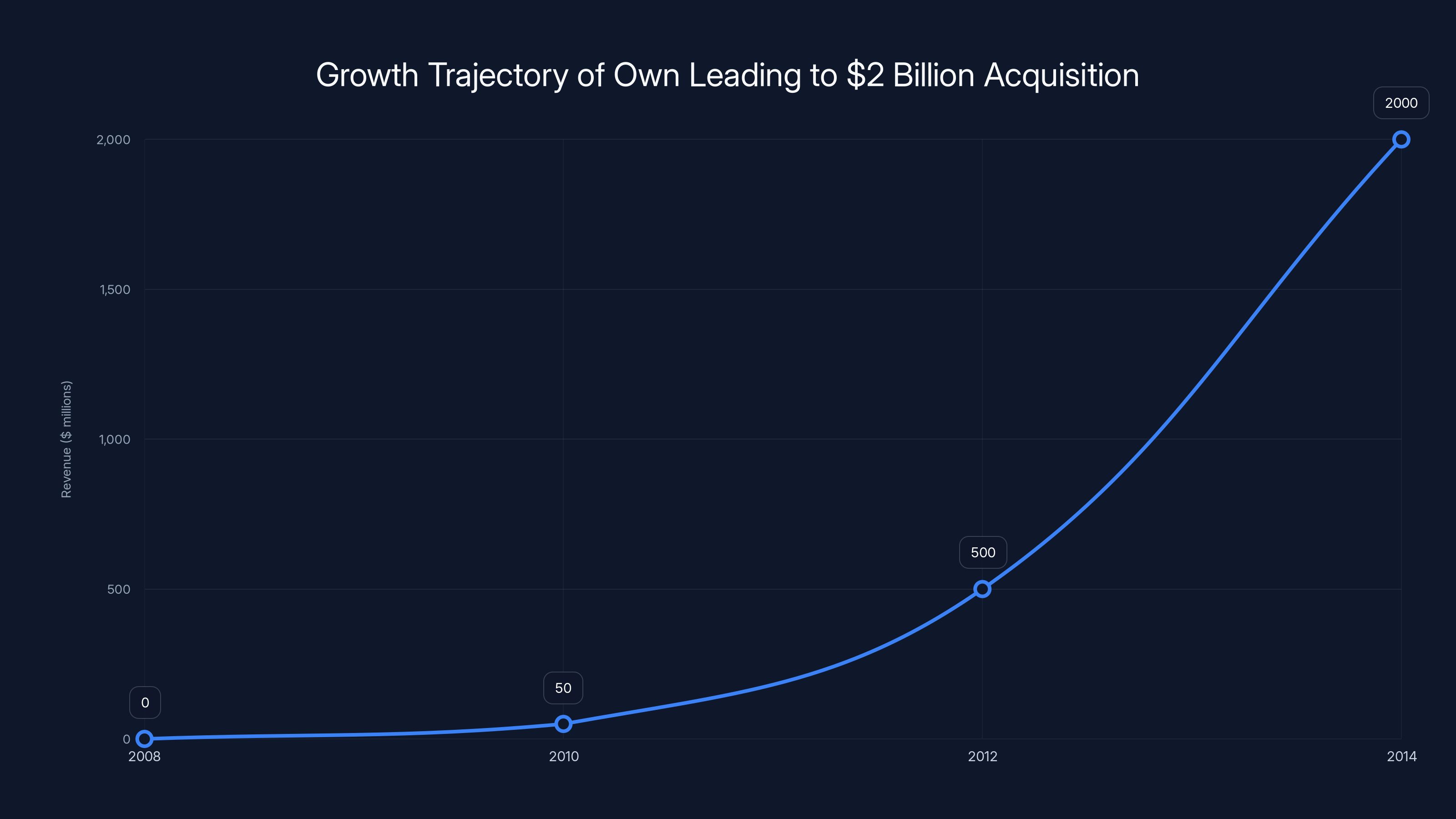

Estimated data shows Own's exponential growth from inception to a $2 billion acquisition by Salesforce in 2014, highlighting the impact of strategic focus and market timing.

Competitive Response: When Platform Vendors Can't Match Focus

Salesforce's Defensive Strategy

As Own grew and demonstrated clear product-market fit, Salesforce—the platform that Own depended on—recognized the threat. When a third-party company builds a critical offering on top of your platform, and that company is capturing significant value from your customers, your strategic choices are limited:

- Acquire the company (which ultimately happened)

- Build competing functionality yourself

- Partner with the leader

- Block or restrict the competitor's access

Salesforce, being a well-run company with resources to match, chose option 2 first: they decided to build backup functionality into Salesforce itself.

On the surface, this should have been devastating for Own. Salesforce had:

- Direct access to customer data

- Ability to integrate backup into the product UI

- Millions of customers to reach with built-in backup

- Engineering resources far exceeding Own's

- No need to convince customers to adopt a separate product

In theory, Salesforce should have dominated the backup category.

They didn't.

Why Platform Vendor Solutions Fail

Salesforce launched their backup product. It didn't gain meaningful adoption. They tried again, refined the approach, and tried once more. It still didn't work.

Meanwhile, Own continued to grow, and their customers continued to value Own's backup more than Salesforce's native offering.

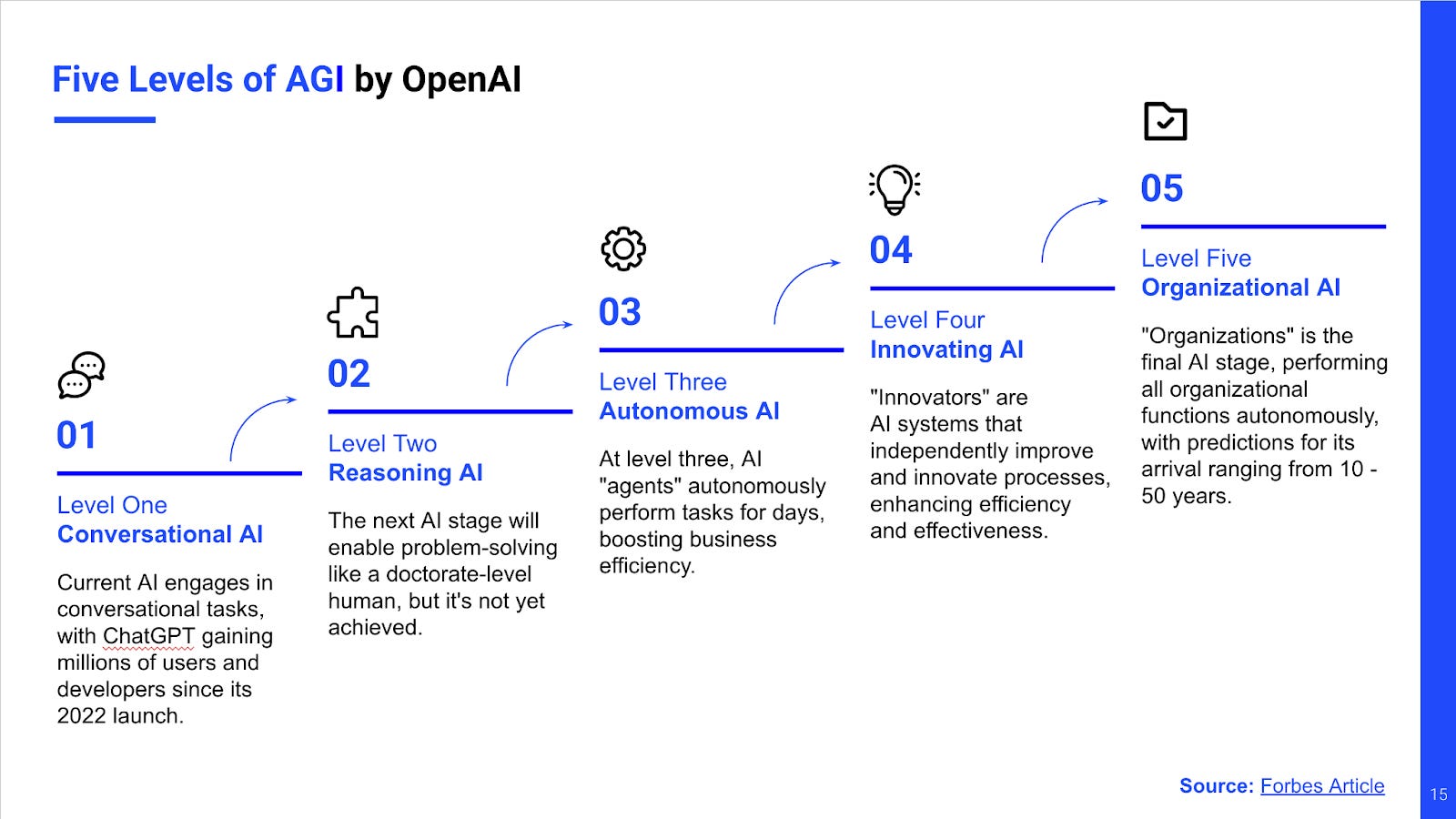

Why did the incumbent vendor's solution fail while the specialized competitor's product succeeded? This illustrates a fundamental dynamic in software markets: when you have 1,000 people waking up every single day focused on being the best backup solution for Salesforce, and your competition has 150 other products to sell, the specialist will almost always win.

Here's the economic reality inside Salesforce:

Resource Allocation Problem: Salesforce's product organization has to allocate resources across hundreds of products and features. Backup for Salesforce is one feature among thousands. The team working on backup has to compete internally for resources with features that might generate more revenue or serve larger customer segments.

Incentive Misalignment: Inside Salesforce, the success metric for a given feature isn't usually "maximize backup adoption." It's often "maintain customer satisfaction" or "reduce churn." These are important metrics, but they don't drive the same intensity of focus that Own's team experiences.

Depth vs. Breadth Trade-off: A feature inside an existing product must be integrated with hundreds of other features, must follow platform architecture, must work with existing authentication and data models. This complexity often forces compromises. Own could optimize every architectural decision specifically for backup.

Customer Education: Salesforce customers already hear from Salesforce about features available within the platform. But customers may not know that backup is critical until they've experienced data loss or talked with experts about disaster recovery. Own's entire go-to-market strategy revolves around educating customers about backup importance. Salesforce's backup feature has to compete for attention in their product messaging.

Perceived Vendor Lock-in: Some customers worry about using Salesforce's backup solution. If Salesforce has your data and owns the backup, and a dispute arises, where do you stand? Third-party backup providers can position themselves as neutral, independent protectors of your data.

The Principle: Ideas Are Worthless, Execution Is Everything

This competitive dynamic taught Own's leadership a critical lesson that shaped company culture: ideas are worthless. It's all about execution.

Salesforce had the idea of backup. They had the resources. They had the customer relationships. On paper, they should have won. But Own won because they executed better.

When Gutmann would discuss this principle with other founders, it resonated strongly. In entrepreneurship, we often get caught up in the novelty of an idea: "Our idea is so unique that no one else will think of it, and therefore we'll have first-mover advantage."

But this fundamentally misunderstands competitive advantage. The source of competitive advantage isn't idea novelty—it's execution quality. Own didn't win backup for Salesforce because no one else thought of it (Salesforce obviously thought of it). Own won because:

- They executed the product better

- They understood customer needs more deeply

- They supported their customers more effectively

- They iterated faster

- They didn't dilute focus with other products

- They built a brand as the backup category leader

This insight shapes hiring, product prioritization, and decision-making. When Own evaluated partnerships or new opportunities, they asked: "Can we execute this better than everyone else?" If the answer was no, they said no.

Leadership: The Hardest Decision Founder-CEOs Face

The Founder Replacement Problem

In every scaling SaaS company, there comes a moment that tests founder leadership: the realization that a co-founder or key leader who built the company might not be the right leader for the next phase of growth.

This is perhaps the most emotionally difficult decision a founder-CEO ever faces. These people:

- Took massive personal risk to start the company

- Likely sacrificed years of life building the business

- Have deep emotional attachment to the organization

- Are friends with the founder-CEO

- Deserve credit for the company's initial success

But as companies scale, requirements change. The CEO who was perfect for building a product from zero to product-market fit might not be the CEO who scales the company from

Own faced this decision, as do most scaling SaaS companies.

The Collective Insight

At a CEO roundtable where Gutmann participated with other scaling founders, the conversation eventually turned to leadership changes. Almost every founder present had made or was contemplating a change to their founding team—replacing someone who had been critical to the company's success.

The vulnerability in the room was remarkable. Founders aren't typically encouraged to discuss these painful decisions publicly. But when the conversation opened up, a pattern emerged.

The moderator asked a simple but devastating question: "How many of you would make that decision six months earlier if you could go back in time?"

Every hand went up.

Not most hands. Not many hands. Every single hand.

This unanimity across dozens of experienced founders pointed to a universal truth: the decision to replace a founder or key leader is always the right decision, and it always takes too long.

Why the Delay Happens

The delay happens for understandable reasons:

Emotional Attachment: These are friends. The decision feels like a personal betrayal, even though it's ultimately a business decision.

Loyalty: The person helped build the company. There's a sense that you "owe" them continued opportunity.

Uncertainty: What if you're wrong about the decision? What if the new leader doesn't work out?

Transition Risk: Leadership changes introduce uncertainty. Employees wonder if their leader is next. Customers might worry about continuity.

Ego: Acknowledging that someone on your founding team isn't suited for the next phase is acknowledging that you made a hiring mistake or didn't develop them effectively.

Lack of Urgency: Often the person isn't "failing" in their role—they're just not scaling as fast as the company needs. It's hard to make a drastic change when the status quo isn't broken.

The Real Cost of Delay

What founders learned through experience was that the cost of delay was higher than the cost of the change itself.

While a key leader is in a role that no longer fits their capabilities:

- They're making decisions that might not be optimal for a scaling organization

- They're managing teams when the team structure needs evolution

- They're likely frustrated themselves (many leaders intuitively sense when they're in over their heads)

- They're slowing down decision-making and execution

- They're potentially damaging their own career by staying too long in a role they can't grow into

- They're preventing the company from bringing in the leader needed for the next phase

The pain of making the change upfront is less than the pain of delaying while organizational performance suffers.

Own, like most scaling SaaS companies, had to make these decisions. By doing so decisively and thoughtfully, the company maintained momentum and brought in leadership capable of scaling Own from product-market fit to a $2B acquisition.

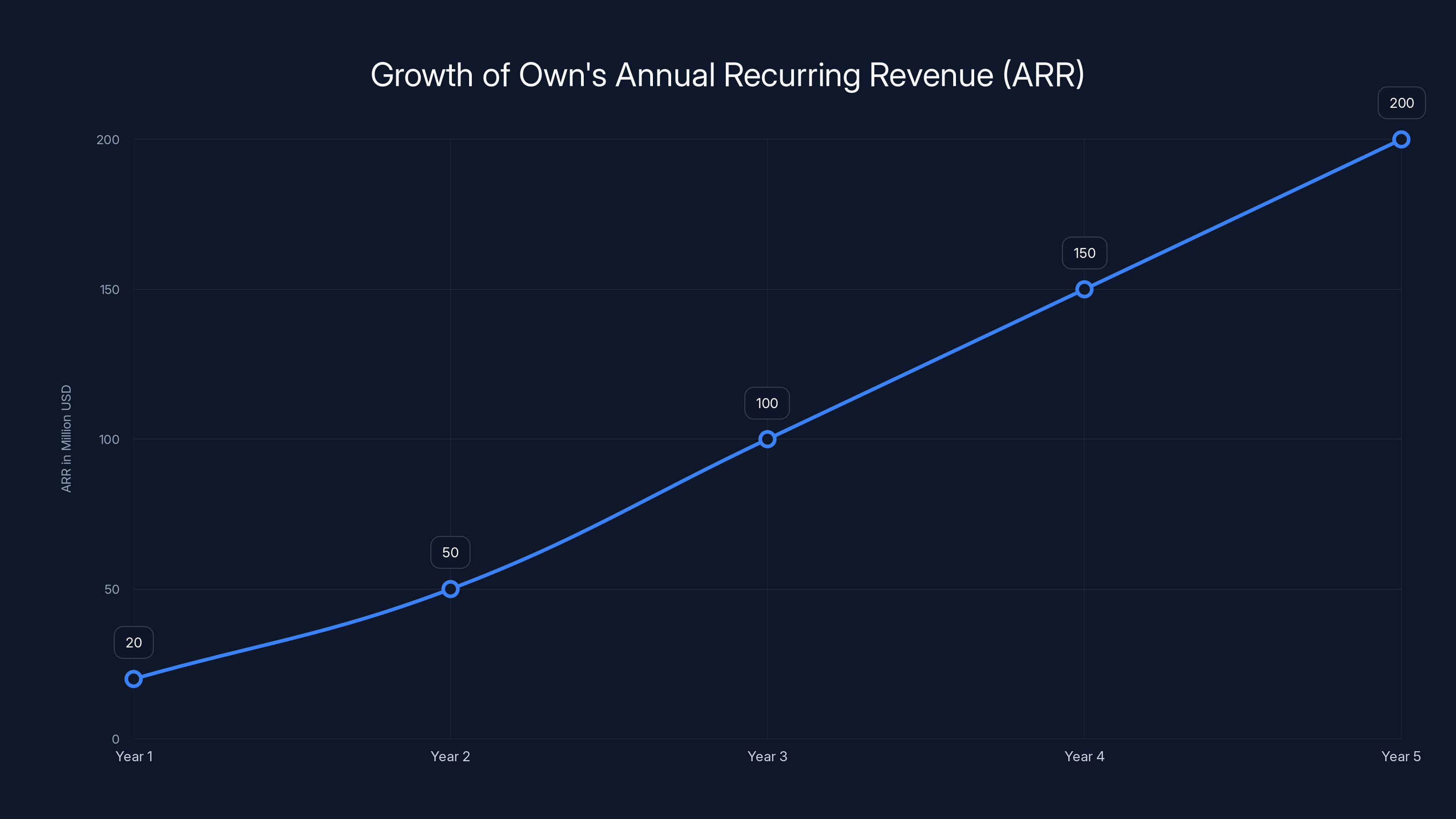

Estimated data shows Own's ARR growing from

The Backup Market: Why It Became Critical

The Shared Responsibility Model

All major cloud providers—Salesforce, Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, and others—operate under what's called the "shared responsibility model." This is communicated in their terms of service, sometimes prominently, sometimes buried in legal documents.

The model is simple in concept but profound in its implications: the cloud provider is responsible for the security and availability of the infrastructure. The customer is responsible for the security and availability of their data.

For Salesforce specifically, this means:

Salesforce Responsibility:

- Maintaining the Salesforce platform servers

- Protecting the data center from physical threats

- Providing authentication systems

- Encrypting data in transit

- Implementing access controls

- Patching vulnerabilities

- Maintaining business continuity for the platform itself

Customer Responsibility:

- Protecting their own login credentials

- Identifying sensitive data and applying appropriate security controls

- Ensuring they have backups of critical data

- Protecting against data loss due to deletions (accidental or malicious)

- Recovering from ransomware attacks

- Maintaining compliance with data retention requirements

- Responding to data breaches or unauthorized access

This division made logical sense. Cloud providers couldn't realistically take responsibility for every customer's data recovery needs—they would need to backup every customer's database continuously, which would multiply infrastructure costs and complexity. So they pushed the responsibility back to customers.

The Data Loss Scenarios

The shift from this theoretical model to practical business needs became clear as enterprise use of Salesforce grew. Real companies faced real data loss scenarios:

Accidental Deletions: Salesforce's standard data retention involves a "recycle bin" where deleted records can be recovered for a limited time. But if you've permanently deleted data, it's gone from the recycle bin. Salesforce won't recover it.

Malicious Deletions: A compromised account, a disgruntled employee with admin access, or a system integration bug could result in massive amounts of data being deleted. Again, once it's gone from the recycle bin, it's permanently gone.

Ransomware and Corruption: As enterprises connected Salesforce more deeply with other systems, and as automation (APIs, integrations, custom code) became more sophisticated, the risk of corruption increased. Malware could modify Salesforce data at scale. Buggy integrations could corrupt critical fields.

Account Takeover: If an attacker gained access to a Salesforce administrative account, they could change configurations, delete users, or export all customer data. Until this was discovered and remedied, the damage could be extensive.

Service Unavailability: While Salesforce maintains high uptime (typically 99.9% or better), that means there could be several hours of downtime per year. For some businesses, that's unacceptable.

Regulatory Compliance: Certain industries (finance, healthcare, legal) have strict data retention requirements. You might be required to keep data for 7 years. If Salesforce deleted your data prematurely, you'd be in violation.

The Backup Solution

Own's backup solution addressed these scenarios by:

Continuous Backup: Backing up Salesforce data continuously (typically in sync with how frequently data changes)

Point-in-Time Recovery: If data was deleted or corrupted, you could restore it to a specific point in time before the problem occurred

Retention Policies: Applying policies to retain backups for as long as needed (important for compliance)

Granular Recovery: Recovering a single deleted record, a user's data, or an entire organization

Multi-Tenancy and Security: Ensuring that backups were encrypted, isolated by customer, and accessible only to authorized personnel

Integration with Salesforce Workflows: Making backup easy to manage from within Salesforce itself, not requiring customers to learn a separate system

As enterprise adoption of Salesforce grew, and as data in Salesforce became increasingly critical to business operations, backup shifted from a nice-to-have to an essential requirement. Companies couldn't afford to lose their Salesforce data.

The Path to $2B: Execution at Scale

Scaling the Sales Organization

Own's path from seed funding to $2B acquisition required building a world-class sales organization. This is where Gutmann's initial skepticism about his ability to run the company became an asset. Unlike founders who are highly technical but lack sales expertise, Gutmann had come from sales backgrounds and had built sales organizations before.

His experience shaped Own's sales strategy in important ways:

Customer-Centric Sales: Rather than trying to force customers into a buying process, Own invested in understanding each prospect's unique situation, their risk tolerance, and their specific data protection needs.

Long Sales Cycles: Enterprise software often involves evaluation periods of 6+ months. Own's sales organization was structured to support these longer cycles, with customer success teams engaging early and often.

Land and Expand: Own's initial strategy focused on dominating the backup market, then expanding with additional offerings as customers wanted more comprehensive data protection solutions.

Customer Success and Retention

With enterprise software, acquiring a customer is only the beginning. The real value comes from retaining customers and expanding with them.

Own built customer success operations that went beyond basic support:

- Dedicated customer success managers for large accounts

- Proactive monitoring of customer backup health

- Regular check-ins about data protection posture

- Training on backup best practices

- Planning for disaster recovery scenarios

This investment in customer success resulted in high net revenue retention (NRR), a metric that shows whether existing customers are expanding or contracting their spending. High NRR (often 120%+) means that despite customer churn, remaining customers are spending more, and the company's revenue pool is expanding.

Financial Performance

Own's path to acquisition was marked by:

Consistent Growth: Growing 100%+ annually meant doubling revenue every year. This is extraordinary growth that requires both great product and great execution.

Profitability: By the time Own was approaching acquisition, the company was likely profitable or near-profitable. This isn't always necessary for an acquisition, but it demonstrates operational excellence and financial sustainability.

Customer Concentration: While Own had thousands of customers, some percentage of revenue came from large customers. Maintaining and expanding these key accounts while also winning net-new customers required sophisticated account management.

Market Leadership: By the time of acquisition, Own was so clearly the leader in Salesforce backup that they effectively owned the category. There were competitors, but Own's market share, brand recognition, and customer satisfaction were dominant.

At a CEO roundtable, 100% of founders indicated they would have made leadership changes earlier if given the chance, highlighting a common delay in decision-making.

Strategic Expansion: Multi-Platform Success

Moving Beyond Salesforce

After achieving single-digit penetration dominance in Salesforce (meaning most major Salesforce customers had Own backup), the company finally began expanding to other platforms.

Interestingly, they didn't necessarily build everything themselves. They acquired competitors:

- Backup solutions for ServiceNow

- Backup solutions for Microsoft 365

- Backup solutions for other enterprise platforms

This acquisition strategy made sense because:

Speed to Market: Acquiring a competitor who already had product-market fit, customers, and a team was faster than building from scratch.

Customer Retention: Rather than competing for the same customer base, Own acquired the competitor and absorbed their customers into a unified platform.

Team and Talent: The acquiring team brought expertise, customer relationships, and market knowledge.

Multi-Platform Offering: Own could now offer backup for Salesforce, ServiceNow, Microsoft 365, and other platforms, making the company more valuable to enterprise customers using multiple platforms.

This multi-platform expansion probably made Own significantly more attractive to Salesforce as an acquisition target. A company that had mastered Salesforce backup and extended to other platforms represented a more complete solution.

The Acquisition Thesis

Why Salesforce Acquired Own

When Salesforce ultimately decided to acquire Own for $2 billion, the strategic logic was clear:

Closing a Product Gap: Backup was clearly important to Salesforce customers. Own had proven there was significant demand. Salesforce could have continued trying to build this themselves, but Own had already won the market.

Customer Value: Instead of requiring customers to buy separate backup from Own, Salesforce could integrate the offering into the core platform, making it more convenient for customers.

Revenue Opportunity: Salesforce could integrate Own's revenue into their own financial results. Depending on Own's subscription model and ASP (Average Selling Price), this could represent significant incremental revenue.

Competitive Moat: As cloud adoption accelerated, data protection became increasingly important. Owning the leading backup solution for Salesforce strengthened Salesforce's competitive position against other platforms.

Ecosystem Health: Salesforce's ecosystem of partners and adjacent solutions is a key part of its strategy. Acquiring the clear leader in a critical category signals commitment to ecosystem completeness.

The $2B Price Tag

To understand if $2B was a fair price, you'd want to know:

- Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR): The amount of revenue Own was generating annually from ongoing subscriptions

- Revenue Multiple: $2B ÷ ARR = the multiple Salesforce paid

- Growth Rate: Fast-growing SaaS companies command higher multiples

- Profitability: Profitable companies command higher prices

- Strategic Value: There may be synergies that justify paying a premium

For context, Salesforce acquisitions have often been in the $1-5B range, and they typically acquire companies with significant growth and strong market positions.

A

Lessons for SaaS Founders

1. Update Your Views When Data Changes

Gutmann's evolution from "that's the dumbest idea" to building the category is a masterclass in intellectual humility. As a founder, your initial thesis about your market might be wrong. Be willing to let data change your mind.

This doesn't mean being inconsistent or easily swayed. It means systematically gathering data about your market, your customers, and competitive dynamics, then updating your mental models accordingly.

2. Focus Is Harder Than Expansion

Saying no to expansion opportunities is genuinely hard. It's especially hard when you've already built the products—the sunk cost fallacy makes you want to launch them.

But Own demonstrated that maintaining focus on a single platform, until you've achieved deep penetration, is more valuable than expanding prematurely.

As you scale, periodically ask: "Are we penetrating our core market deeply, or are we spreading too thin?"

3. Financial Discipline Drives Execution

The CEO running his own financial model sounds like an inefficient use of time. But it created accountability and alignment between financial planning and business execution.

Invest in financial systems and processes, but ensure that the CEO understands the financial model deeply. Your model becomes your strategy.

4. Execution Matters More Than Ideation

Own didn't invent the idea of backup for SaaS. They just executed better than everyone else, including the platform vendor who should have dominated.

As a founder, you're not trying to have the most original idea. You're trying to execute better than alternatives.

5. Founder Transitions Are Painful But Necessary

Most scaling companies will need to make difficult decisions about founder roles. The research shows that these decisions are usually right, and they're usually delayed.

If you're facing this decision, remember the CEO roundtable: almost everyone would make the change six months earlier if they could.

6. Build for Scalability, Not Just Current Needs

Own's architecture, customer success processes, and sales organization had to be built to scale. You can't build for hundreds of customers and then rebuild for thousands.

As you scale, constantly ask: "Does this process/system/team structure work at 10x our current size?"

The Backup Market Today

Competitive Landscape

After Own's acquisition by Salesforce, the backup market has continued to evolve. There are now multiple competitors offering backup and disaster recovery:

Traditional Backup Vendors: Companies like Veeam, Commvault, and others have expanded into SaaS backup.

SaaS-Native Backup: Companies specifically focused on backing up SaaS applications (beyond what Own was doing at acquisition).

Platform-Native Solutions: Salesforce, Microsoft, Google, and other platforms have invested in improving their native backup and recovery capabilities.

The category Own pioneered—standalone backup for SaaS applications—has matured from an emerging market to an established market with multiple vendors.

Market Adoption

Today, backup for Salesforce is no longer a question of "if" but "how and with whom." Most enterprise Salesforce customers have some backup solution in place. The questions have evolved:

- What level of granularity for backup and recovery?

- How long should backups be retained?

- How should backup integrate with compliance requirements?

- Should backup come from the platform vendor or a third party?

These nuances show a mature market with sophisticated customers.

Parallel Approaches in the Market

For teams looking to build in adjacent markets or develop automation and productivity solutions, Runable offers AI-powered platforms for content generation, workflow automation, and developer productivity. Similar to how Own focused ruthlessly on a single problem for Salesforce until achieving dominance, Runable concentrates on empowering teams with AI agents for document generation, automated workflows, and productivity tools at a cost-effective $9/month, making sophisticated automation accessible without the complexity of enterprise platforms.

Teams prioritizing operational focus and execution depth—much like Own demonstrated—often find that specialized, focused solutions outperform broader platforms in specific use cases.

The Broader Implications of Own's Success

Category Creation vs. Market Participation

One of Own's most remarkable achievements was category creation. Before Own, there was no "Salesforce Backup" category. Companies didn't have a line item in their IT budgets for Salesforce backup. The category didn't exist.

Own's success was partly about identifying that the category should exist (shared responsibility model meant customers needed backup) and then dominating it before competitors arrived.

This illustrates an opportunity for founders: sometimes the biggest wins come not from competing in an established category, but from creating a new category that becomes essential.

The Power of Saying No

In our era of rapid growth and "move fast and break things," Own's disciplined "no" is a reminder that focus is a competitive advantage.

The companies that scale fastest aren't always the ones trying to do the most. They're often the ones doing one thing extraordinarily well until they have the resources and expertise to do other things well.

From Founder to CEO

Gutmann's journey from skeptic to category-defining CEO illustrates how the right founder matters less than the right leader. Gutmann wasn't the original technical founder. He was someone who recognized a market opportunity and decided to bet his career on it.

This is important because it means CEO positions at high-growth companies don't require a track record of infinite success. They require intellectual honesty, focus, and the willingness to learn.

Conclusion: Building for a $2B Exit

Own's path from "dumbest idea ever" to $2 billion Salesforce acquisition provides a roadmap for scaling SaaS companies in the 2020s and beyond. The key lessons extend far beyond the backup space.

Market timing and intellectual humility matter more than initial conviction. Gutmann's willingness to change his mind about the Salesforce backup market—based on data and pattern recognition—turned a skeptic into a builder. For founders, this means staying connected to customer feedback, market trends, and competitive dynamics. Your initial thesis might be wrong. Good founders update their beliefs when evidence warrants.

Focus and discipline are underrated competitive advantages. In a world where growth is celebrated and expansion is encouraged, Own chose a different path: dominate a single platform until achieving deep penetration, then expand deliberately with the resources and expertise to execute well. This isn't a conservative strategy—it's a focused strategy that enabled sustainable growth and market dominance.

Financial rigor and CEO involvement in P&L matters. The image of a CEO manually running financial models sounds outdated in an era of sophisticated FP&A software. Yet Own's CEO personally maintaining the financial model—and the company hitting their targets more consistently than peers—suggests that CEO-level understanding of your financial trajectory drives better execution. Your model is your strategy.

Ideas are worthless relative to execution. Salesforce clearly thought of backup. They had resources to build it. Yet Own's focused execution beat their efforts. In a competitive market, differentiation comes from execution quality—how you hire, how you serve customers, how you build product, how you organize your sales and success teams. The novelty of the idea matters far less than how well you execute it.

Leadership transitions, while painful, are often necessary. The most experienced founders and CEOs in the industry universally agreed they would make founder/leader transitions sooner if they could do it over. If you're facing this decision, you're probably in the majority of scaling companies.

Acquisition by a platform vendor can be strategic success, not failure. Own wasn't a "acqui-hire" or a company that failed to establish itself. It was acquired for $2 billion by Salesforce because Own had achieved such dominance in the category that Salesforce needed to own it to maintain their platform's completeness. This is a successful outcome, even though Own might have continued scaling as an independent company.

As you build your own SaaS company or lead your organization, Own's journey offers a template for thinking about focus, execution, financial discipline, and the difficult leadership decisions that separate good companies from great ones. The path from "stupid idea" to "billion-dollar acquisition" isn't necessarily about being first or being smartest. It's about being disciplined, focused, and relentlessly oriented toward execution.

The next Own-size success might be building on top of platforms that don't yet realize they need a particular feature. It might be serving a market where current vendors are distracted. It might be focusing so deeply on customer success that you become indispensable to thousands of companies.

The path is rarely a straight line from idea to acquisition. But Own's story shows that founder conviction, market timing, execution excellence, and the humility to update your views can compound into something truly special.

FAQ

What was Own's primary product offering?

Own built backup and disaster recovery solutions for Salesforce, allowing enterprises to protect their Salesforce data against accidental deletions, malicious actions, system errors, and platform outages. The company eventually expanded to offer backup solutions for other major SaaS platforms like ServiceNow and Microsoft 365 through both organic development and acquisitions.

Why did Sam Gutmann initially dismiss the Salesforce backup idea as "the dumbest idea ever"?

In 2008, when Gutmann heard the backup-for-Salesforce idea, Salesforce had only about 50,000 customers, and there was an assumption that a major platform vendor would handle data protection comprehensively. The idea seemed like a niche market with limited addressable size. By 2014, Salesforce had grown to 250,000+ customers, and Gutmann recognized the pattern of shared responsibility models across all cloud providers, causing him to completely reverse his initial assessment and join Own as CEO.

How did Own maintain 100%+ annual growth rates while staying focused on a single platform?

Own adhered to a disciplined principle: don't expand into adjacent markets until your core market has single-digit penetration AND you've reached $100M+ ARR. By saying no to launching pre-built backup solutions for ServiceNow, Microsoft 365, and other platforms despite having them ready, Own kept the sales organization, engineering teams, and marketing efforts focused entirely on dominating Salesforce. This laser focus allowed them to achieve deeper market penetration and higher growth rates than they would have achieved spreading resources across multiple platforms.

What role did financial discipline play in Own's success?

Sam Gutmann personally maintained Own's financial model in Excel until the company reached $200M+ ARR, rather than outsourcing FP&A to a specialized firm. This direct involvement created accountability for every investment decision—each expense tied directly to a cell in the financial model. An external CFO firm noted that Own was the only company among their clients where their FP&A team wasn't managing the finances, and also the only company consistently hitting their projections, suggesting that CEO-level financial rigor drives better execution.

Why couldn't Salesforce's native backup solution compete with Own's offering?

Although Salesforce had vastly more resources, technical access to their platform, and direct customer relationships, Own's specialized focus proved more valuable than platform vendor resources. Salesforce's backup feature had to compete internally for resources with hundreds of other products, while Own's entire organization focused exclusively on backup excellence. Additionally, customers sometimes preferred independent third-party backup providers for perceived neutrality and to avoid vendor lock-in, trusting Own as a specialist more than a feature within the larger platform.

What is the shared responsibility model and why did it create an opportunity for Own?

Cloud providers like Salesforce explicitly state that they're responsible for infrastructure security and platform availability, while customers are responsible for protecting their own data and ensuring backups. This division of responsibility meant that even though Salesforce provided a secure infrastructure, customers still needed independent backup solutions to protect against data loss from accidental deletions, malicious actions, system errors, or integration failures. Own's entire value proposition was built around fulfilling the customer's side of this shared responsibility.

How did Own's acquisition of other backup platforms accelerate its expansion beyond Salesforce?

Rather than building backup solutions from scratch for ServiceNow, Microsoft 365, and other platforms, Own acquired existing competitors in these spaces. This approach provided speed to market, retained existing customer bases, absorbed talented teams with platform expertise, and allowed Own to offer a unified multi-platform backup solution. This expansion made Own more attractive to enterprise customers using multiple SaaS platforms and ultimately more valuable to Salesforce as an acquisition target.

What was the strategic value of the $2B acquisition price for Salesforce?

Salesforce's $2 billion acquisition of Own represented a strategic decision to own the category-leading backup solution rather than continue competing with Own's specialized product. By acquiring Own, Salesforce closed a product gap in their platform completeness, provided integrated backup to their customer base, captured Own's recurring revenue, and prevented a competitor from potentially acquiring Own or using backup capabilities to build alternative ecosystems around Salesforce data.

How did Own's approach to saying no to expansion opportunities differ from typical SaaS growth strategies?

Most SaaS companies actively pursue expansion opportunities—launching adjacent products, entering new verticals, and diversifying revenue streams. Own inverted this approach, killing products that weren't generating revenue and refusing to launch multi-platform backup until they had achieved deep penetration of the Salesforce market. This counter-intuitive strategy—saying no despite having built the products—resulted in higher growth rates and market dominance rather than the broader market coverage that expansion would have provided.

What principles from Own's success translate to other SaaS businesses beyond backup and disaster recovery?

Own's principles apply across SaaS categories: market timing and willingness to update beliefs based on data, relentless focus on a single market until deep penetration, CEO-level financial rigor, disciplined execution versus idea novelty, difficult but necessary leadership transitions, and building for scalability while maintaining focus. These principles suggest that sustainable SaaS success comes from choosing a specific problem, becoming obsessively good at solving it, building financial discipline into operations, and expanding only when you've exhausted the primary market's potential.

Key Takeaways

- Market timing and intellectual humility matter more than initial conviction—Gutmann's willingness to reverse his 'dumbest idea' assessment demonstrates importance of updating beliefs with data

- Single-platform focus until deep penetration outperforms premature multi-market expansion—Own's discipline to kill pre-built products and stay focused on Salesforce drove 100%+ annual growth

- CEO-level financial rigor and direct model ownership drive consistent execution—Own's CEO-managed Excel model resulted in company hitting projections while competitors consistently missed theirs

- Execution quality matters infinitely more than idea novelty—Salesforce's native backup solution failed despite platform advantages because Own's focused team executed better

- Difficult leadership transitions are universally regretted as being delayed—experienced founders unanimously agreed they would replace key leaders six months earlier if given the chance

- Category creation and dominance can drive billion-dollar valuations—Own didn't compete in established markets; it created the Salesforce backup category and owned it

- Platform acquisition can represent strategic success, not failure—$2B acquisition by Salesforce validated Own's market dominance and value creation

Related Articles

- Masking Net New Customer Slowdowns: The #1 B2B SaaS Growth Deception [2025]

- AI in Contract Management: DocuSign CEO on Risks & Reality [2025]

- Nvidia's $100B OpenAI Investment: Reality vs. Reports [2025]

- Airtable Superagent: AI Agent Features, Pricing & Alternatives [2025]

- Nvidia's $2B CoreWeave Investment: AI Infrastructure Strategy Explained

- Hubristic Fundraising: Brex's $5.15B Acquisition & Lessons [2025]