Introduction: When a Tech Giant Becomes the Government's Surveillance Backbone

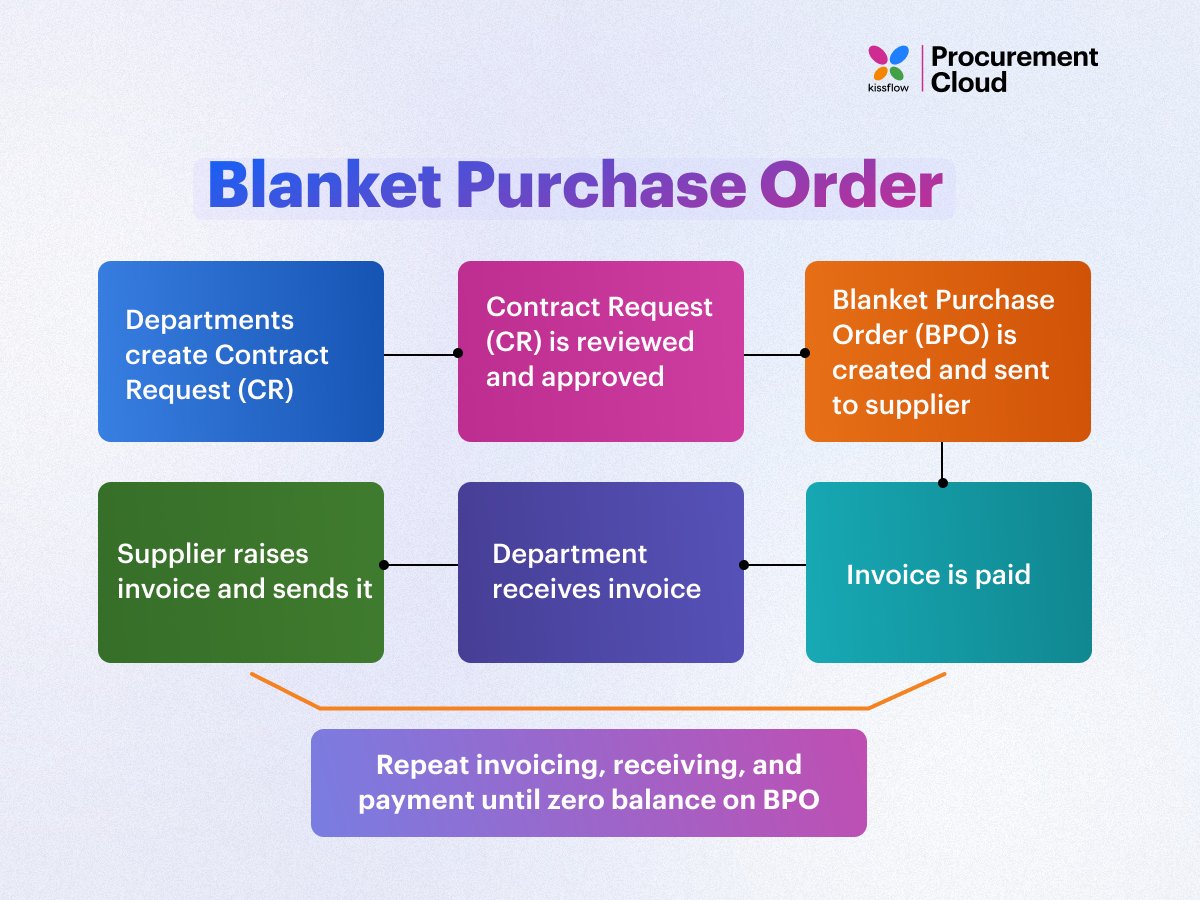

Last week, something massive happened in the world of government surveillance, and most people missed it entirely. Palantir, the secretive data analytics company that's been quietly building the infrastructure behind US immigration enforcement, just signed a $1 billion purchasing agreement with the Department of Homeland Security. But here's the thing: this wasn't a competitive bid. It was a blanket purchase agreement that essentially lets DHS agencies skip the entire bidding process and buy up to a billion dollars worth of Palantir's services whenever they want, as detailed by Wired.

If that sounds like a big deal, it's because it absolutely is. And if you're wondering why you haven't heard about it everywhere, well, that's part of the problem.

This agreement represents the culmination of years of increasingly controversial work between Palantir and some of the most sensitive government agencies in America. We're talking about tools that help Immigration and Customs Enforcement identify deportation targets. Systems that map out where immigrants are likely to be found. Software that provides what Palantir itself calls "near real-time visibility" into people's movements and behaviors, as reported by The New York Times.

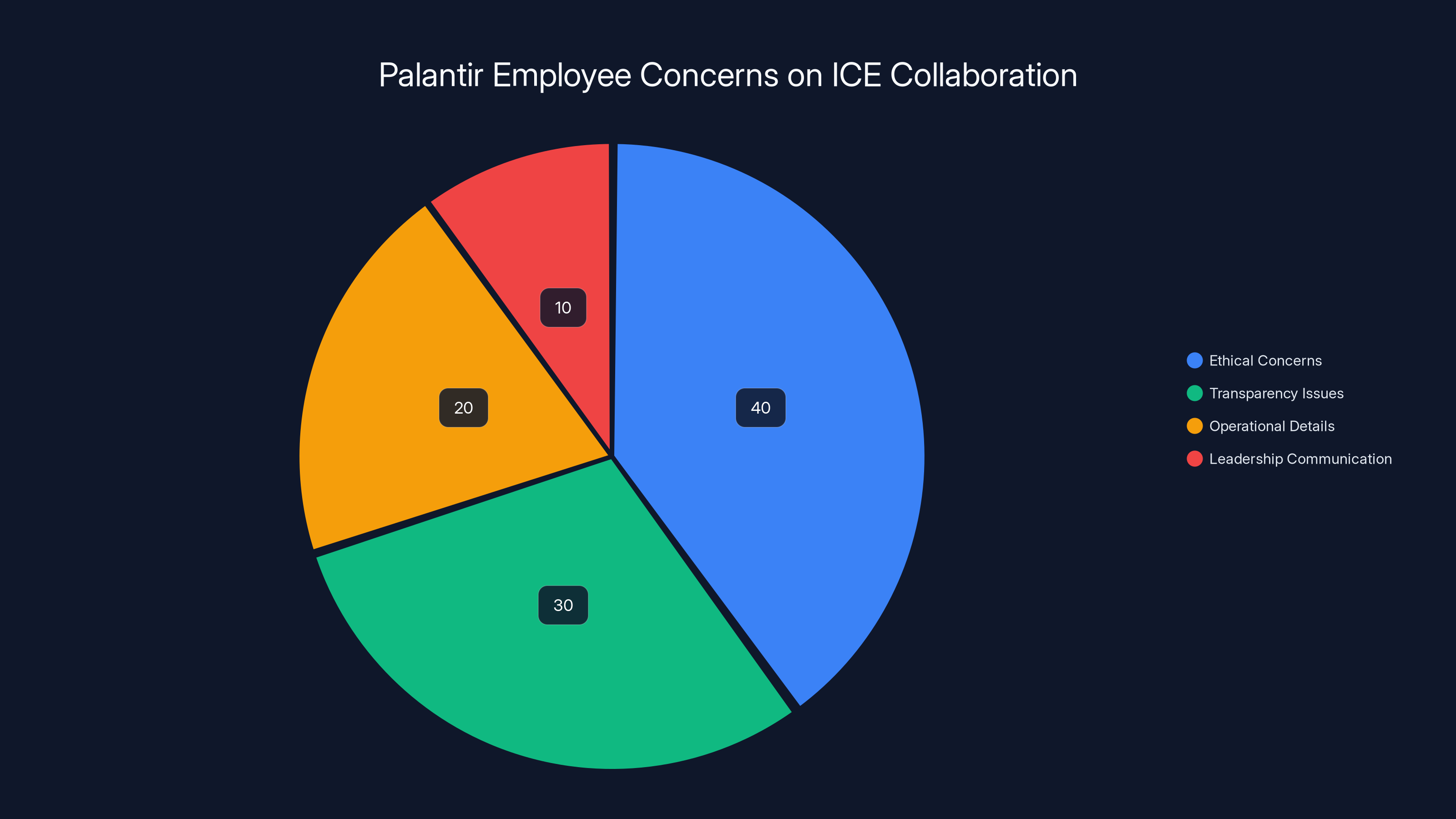

But here's what makes this moment particularly important: inside Palantir's own offices, employees are having a reckoning. They're asking hard questions about whether the tools they're building align with their values. Some are demanding transparency. Others are walking away from the company entirely. In January, after a nurse named Alex Pretti was shot and killed in Minneapolis, Palantir's Slack channels exploded with staff demanding answers about how their technology was being used by ICE, as noted by Wired.

The company's response? CEO Alex Karp recorded a video for employees explaining the immigration work, but according to people who watched it, he dodged the hardest questions. He told curious employees that if they wanted real details, they'd have to sign nondisclosure agreements first, as highlighted by Wired.

Now, with a $1 billion deal on the table, the stakes feel even higher. This article digs into what this agreement actually means, how Palantir's surveillance tools work, the internal tensions at the company, what regulators are actually doing about it, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- The Deal: Palantir just signed a 1 billion in services

- The Technology: Palantir has built tools for ICE including Immigration OS (near real-time immigrant tracking) and ELITE (mapping deportation targets from multiple data sources)

- The Conflict: Palantir employees are increasingly uncomfortable with immigration work, and the company is struggling to retain staff amid public criticism

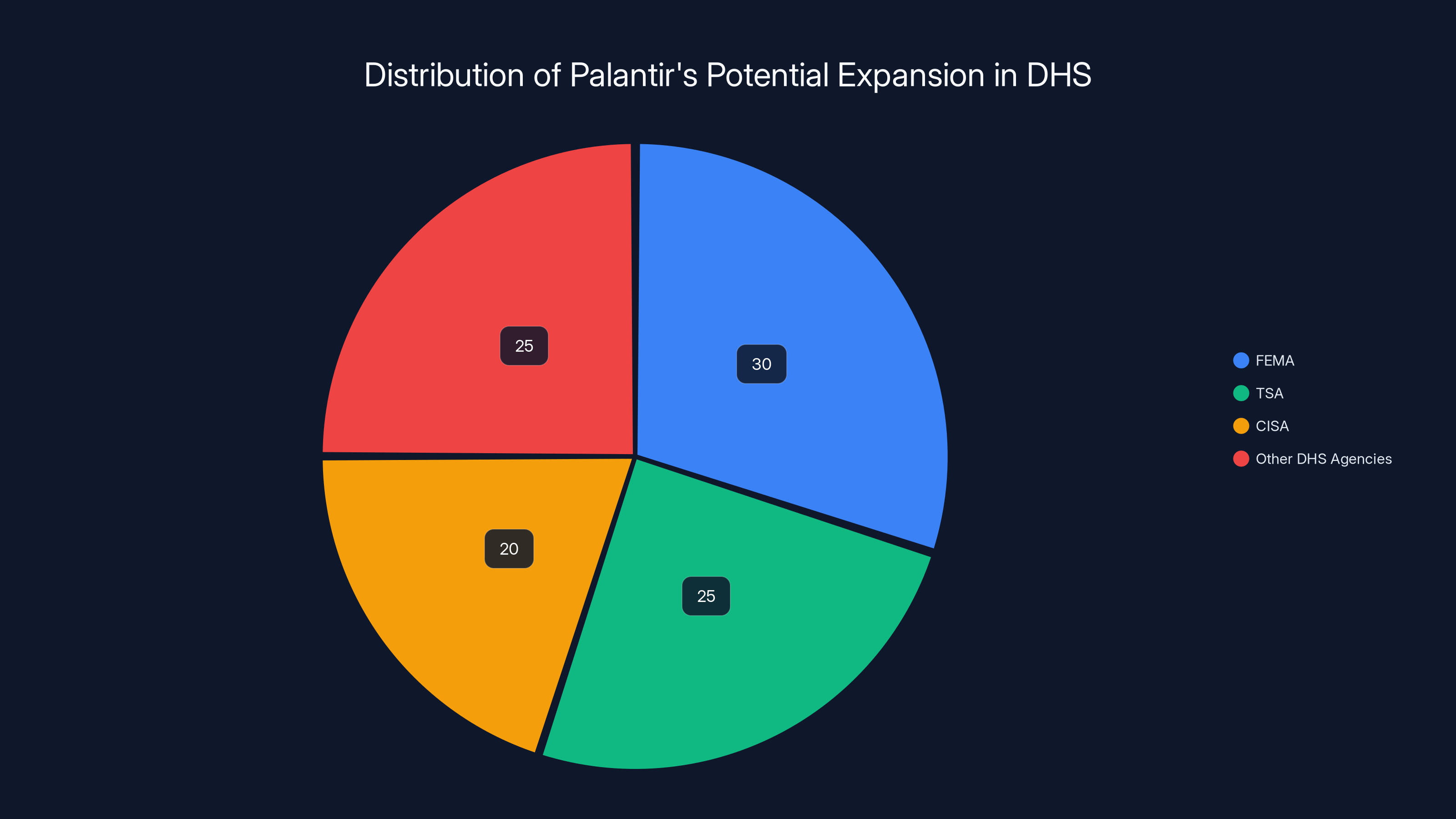

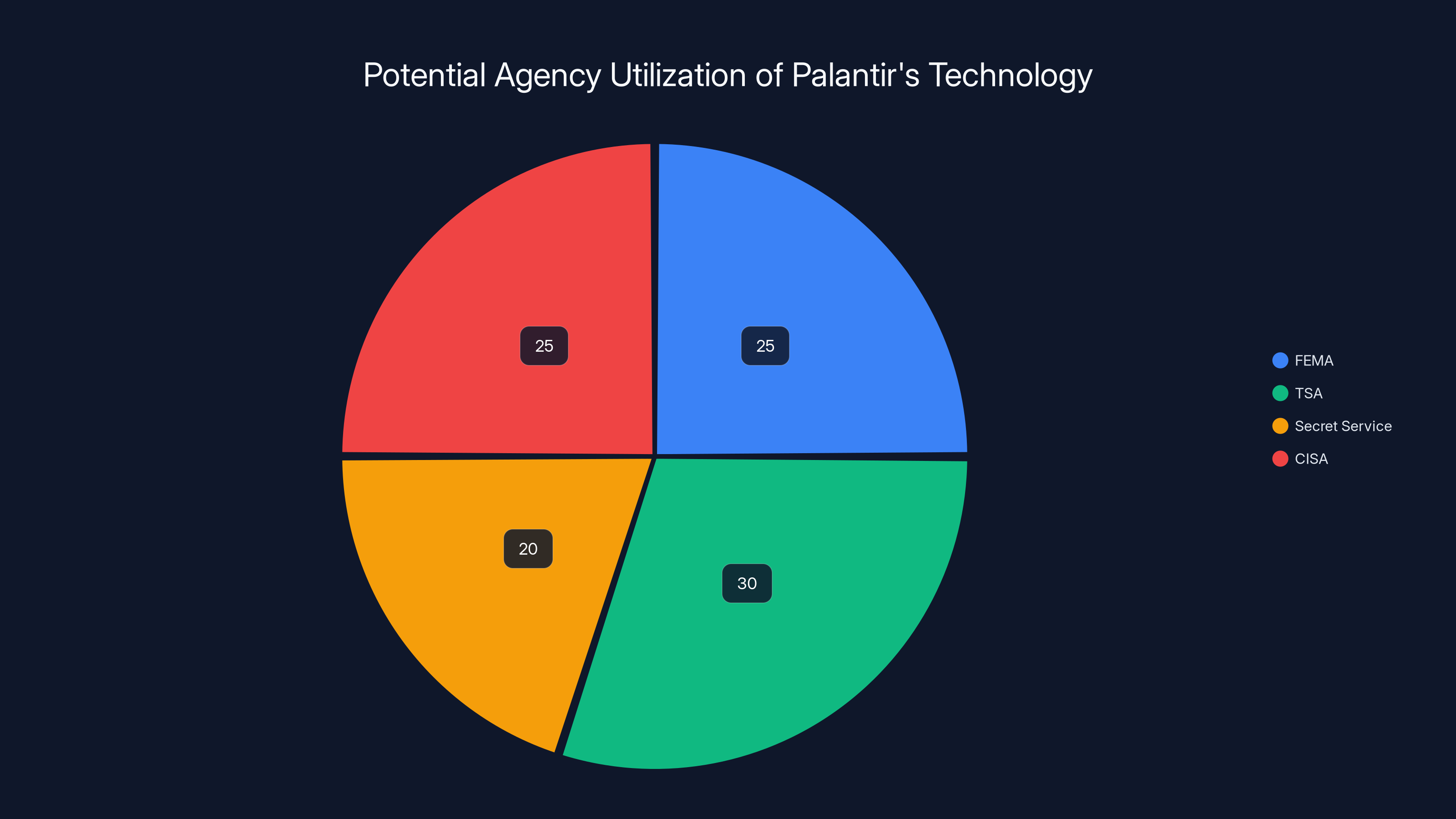

- The Expansion: The agreement opens doors for Palantir to sell its services to FEMA, TSA, the Secret Service, and cybersecurity agencies across DHS

- The Question: Whether advanced surveillance tools in government hands actually protect civil liberties or enable the exact dragnet operations that critics fear

Estimated data shows potential market share distribution for Palantir within DHS agencies post-BPA. FEMA and TSA are expected to be major beneficiaries.

What Exactly Is a Blanket Purchase Agreement, and Why Should You Care?

Let's start with the mechanics, because understanding what just happened requires understanding how government contracting actually works.

Normally, when a federal agency wants to buy something expensive, there's a process. They have to put the work out for competitive bid. Multiple companies submit proposals. The government evaluates them. Someone wins, someone loses. It's supposed to ensure fair competition and the best use of taxpayer dollars.

A blanket purchase agreement (BPA) changes that game fundamentally. Instead of competitive bidding for each new project, the government pre-approves a vendor for a specific type of work, up to a specific dollar amount, over a specific time period. In this case, it's Palantir, for $1 billion, over five years, as explained by Homeland Security Today.

What this means in practical terms: any DHS agency that needs Palantir's software services can now just call them up and order it without having to justify that choice through competitive bidding. Want to expand the tool used to track immigrants? Just order it. Need new analytics software for the Secret Service? Palantir's already approved. It's bureaucratic efficiency on steroids, and it completely removes a crucial safeguard that was theoretically supposed to prevent any single vendor from becoming too essential to too many government functions.

Palantir executives are pretty open about why this matters to them. In the email announcing the deal to employees, Akash Jain, the company's chief technology officer, didn't hide his excitement. This agreement, he wrote, could let the company expand across DHS into agencies like FEMA, the TSA, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. It opens doors that weren't as easily accessible before, as reported by The Colorado Sun.

For DHS agencies, there's an obvious appeal: Palantir already knows their systems, their data architecture, their business processes. Training new contractors would take time and money. Sticking with what you know is simpler.

But here's where it gets complicated. When you remove competitive pressure from a market, you also remove one of the primary incentives for a company to keep prices reasonable, to innovate faster, or to be especially responsive to customer concerns. You've just told Palantir: you've got this. Build more tools. Expand to new agencies. You don't have to convince anyone that you're the best option anymore.

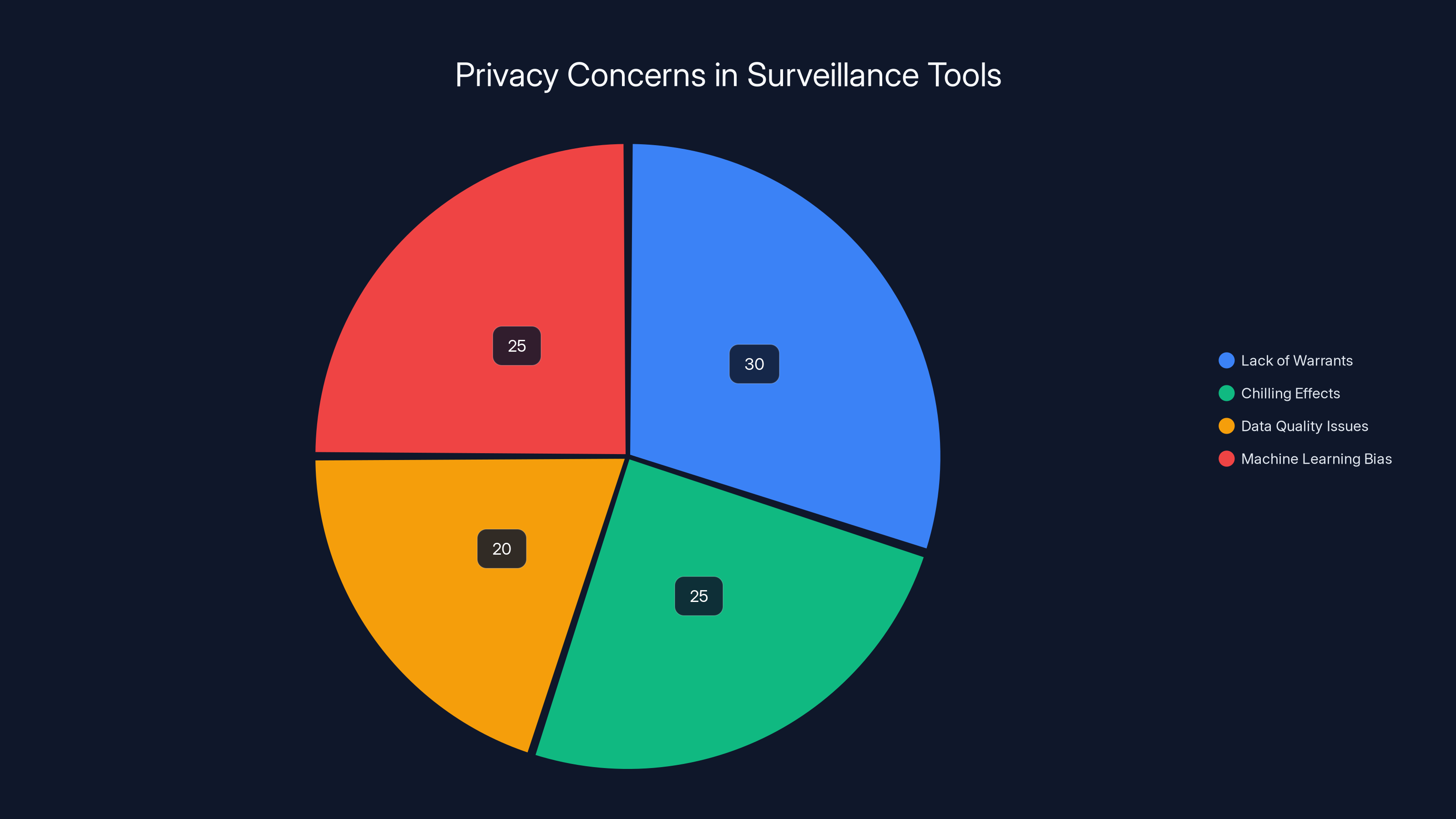

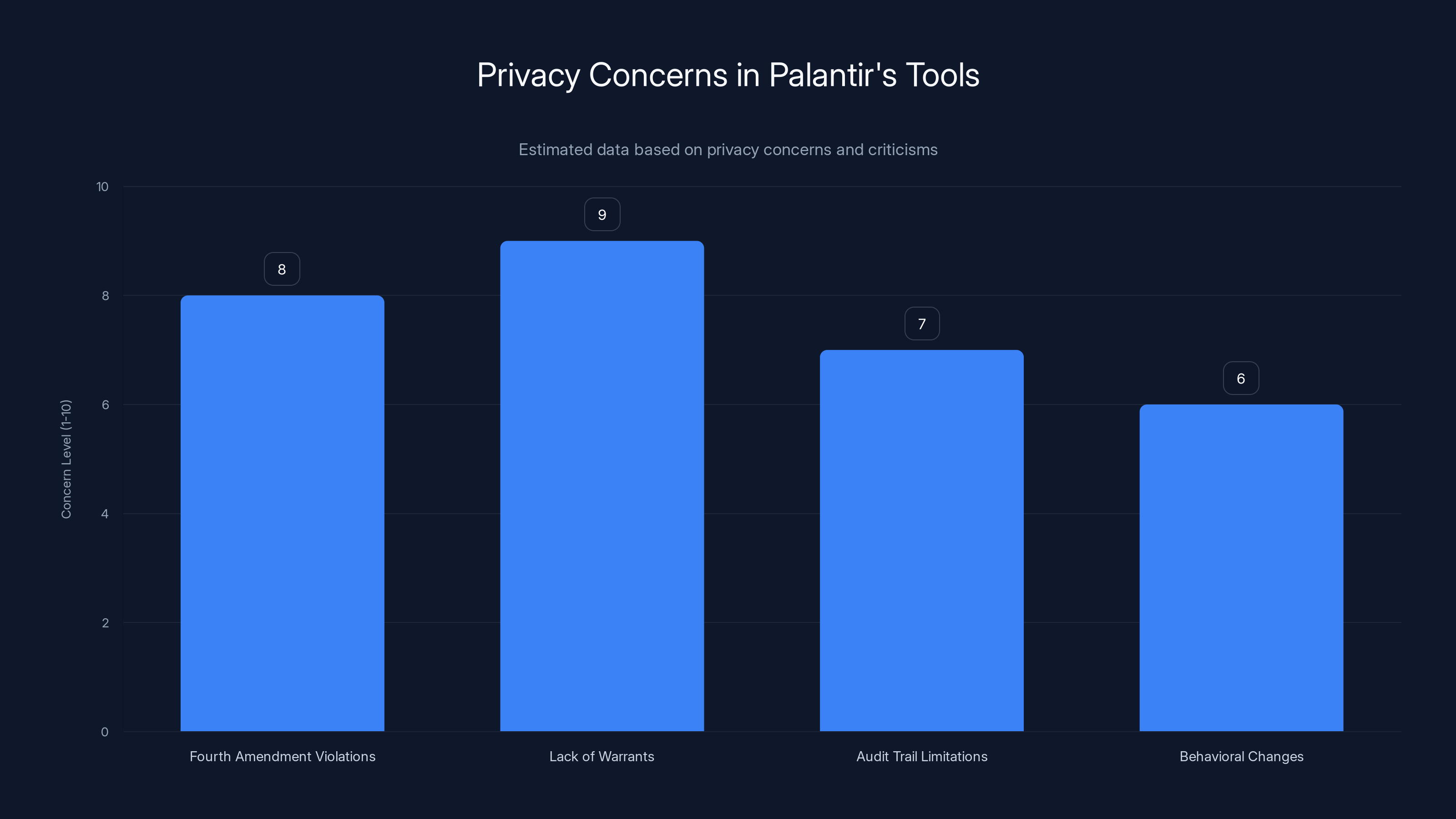

Estimated data shows that lack of warrants and machine learning bias are major privacy concerns, each accounting for about 25-30% of the issues raised.

The Technology: How Palantir Powers Immigration Enforcement

Understanding Palantir's $1 billion deal requires understanding what they actually built for ICE and DHS. And this is where things get genuinely sophisticated and genuinely concerning.

Immigration OS: The Real-Time Tracking System

Last year, reports emerged that Palantir had built something called Immigration OS. The purpose? To provide what Palantir itself described as "near real-time visibility" on immigrants in the United States, particularly those self-deporting. ICE paid Palantir $30 million specifically for this tool, as detailed by 404 Media.

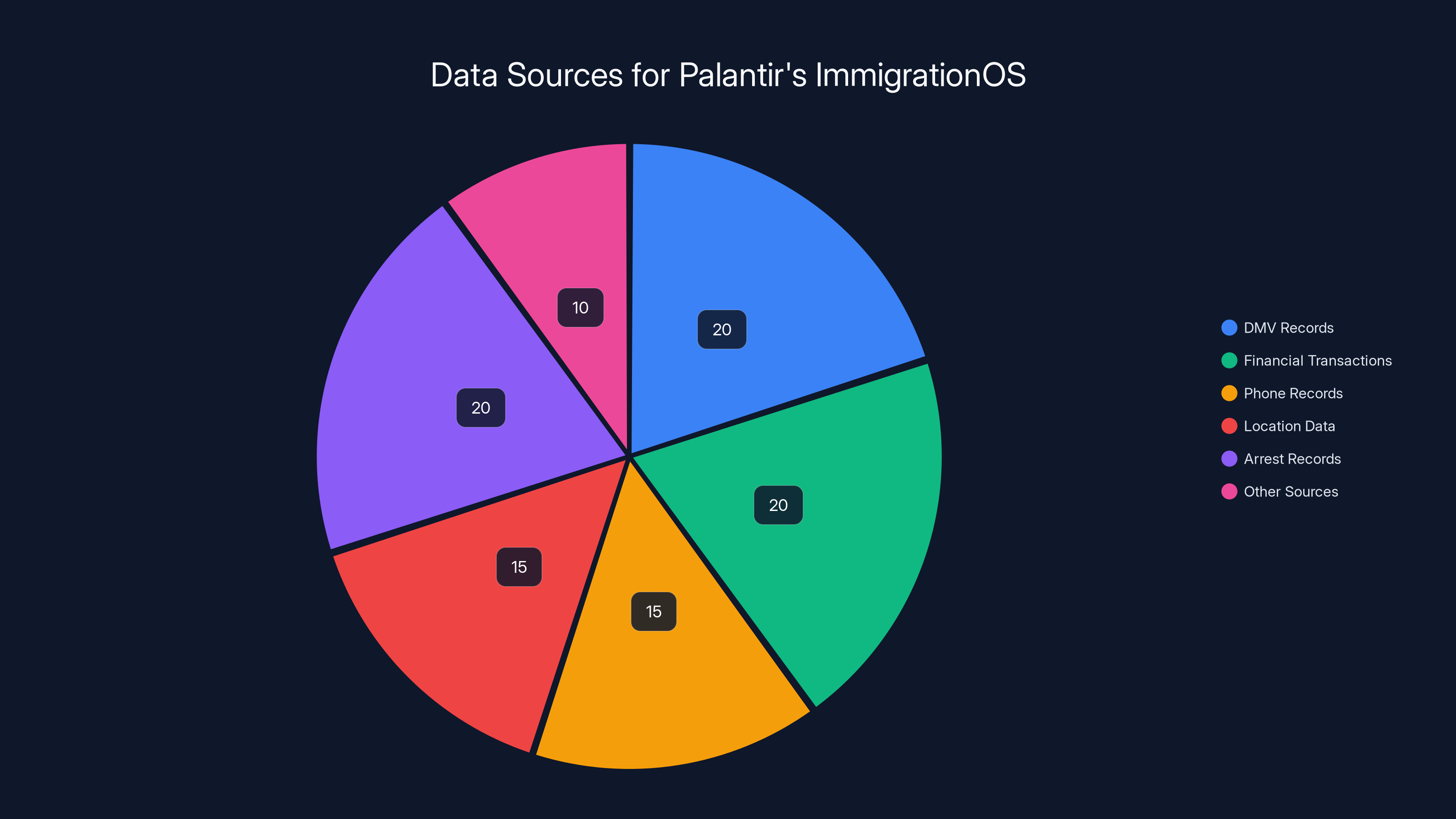

Now, "near real-time visibility" is bureaucratic language. What it actually means is the ability to know where people are and what they're doing almost as it happens. Palantir accomplishes this by pulling data from multiple sources: DMV records, financial transactions, phone records, location data, and arrest records. The system likely integrates with facial recognition databases. It probably connects to immigration detention facilities' booking systems. It might even pull data from healthcare providers when someone gets treated for an injury.

The way Palantir's systems work, at a technical level, is by building what's called a "knowledge graph." Imagine a web of connected dots. Each dot is a person, a phone number, a financial transaction, an address, a vehicle registration. The lines connecting the dots represent relationships: this phone number called that phone number, this person lived at that address, this credit card was used at this store. Machine learning algorithms then look for patterns that match whatever criteria ICE is searching for.

For immigration enforcement, the criteria could be: immigrants who are likely to self-deport, immigrants with certain characteristics, immigrants without legal status who have triggered any flag in any system.

The power of this system is that it doesn't require perfect information. If you're 70% sure someone is undocumented, and 60% sure they're in a particular state, and 50% sure they'll be at a certain location because they've established a pattern, those probabilities multiply in the system's algorithm. Suddenly, your total confidence level might be 21% accurate on any individual prediction, but when you run millions of these calculations, you catch thousands of people you're looking for.

ELITE: The Deportation Targeting Tool

More recently, Palantir developed something called Enhanced Leads Identification and Targeting for Enforcement (ELITE). The name itself is almost comically transparent about what it does: it identifies and targets people for enforcement action. Specifically, deportation, as explained by Wired.

ELITE works by creating maps. Literal, geographic maps showing where potential deportation targets are likely to be found. The system pulls data from DHS databases, yes, but also from the Department of Health and Human Services. This is particularly chilling because HHS data can include information about people who sought healthcare, people who applied for benefits for their children, people who went to the emergency room.

The integration of HHS data into a tool designed specifically for deportation targeting means that seeking healthcare, one of the most basic human needs, has become a data point that can be used against you in immigration enforcement.

According to reporting on how ELITE works, the system creates "thermal maps" showing concentrations of people who match certain criteria. ICE agents can then use these maps to focus enforcement operations in specific neighborhoods, specific areas, sometimes specific buildings.

Again, at a technical level, this is sophisticated. But at a human level, it's terrifying. It means that a Syrian family that went to the ER during a flu season is now a data point on a map. A Dominican woman who applied for WIC benefits for her kids is now flagged. A Vietnamese refugee who called a DHS number to update his address is now trackable.

The Internal Rebellion: What Palantir Employees Actually Think

Here's something that doesn't usually make headlines about defense contractors: their employees sometimes actually care about ethics.

At Palantir, that's been creating real problems lately. And the company's leadership seems genuinely unsure how to handle it.

The Breaking Point: Alex Pretti and the January Reckoning

In January 2025, a Minneapolis nurse named Alex Pretti was shot and killed. Reports suggest the incident involved immigration enforcement dynamics. Within hours of news spreading about her death, Palantir's internal Slack channels exploded. Employees started asking questions that their company had been avoiding, as reported by Minnesota Reformer.

How exactly does our technology power ICE? What happens when immigrants are identified by our systems? Are we comfortable with that? Should we be?

For a company that has built its mystique on opacity, having thousands of employees simultaneously demanding transparency is a genuine problem. You can't tell people "trust us" when people are dying and your tools helped identify them.

Palantir's response was to update its internal wiki with information about its ICE work. But according to people familiar with the update, it didn't say much that wasn't already known. Yes, we work with ICE. Yes, we've built tools for them. But detailed information about how those tools actually function? You'd need to sign an NDA to learn that.

Then CEO Alex Karp recorded a video for employees. A nearly hour-long conversation with Courtney Bowman, Palantir's global director of privacy and civil liberties engineering. And here's where it gets interesting: according to people who watched it, Karp didn't actually answer the hardest questions. When employees asked directly about how Palantir's technology enables ICE deportations, Karp deflected. The real conversation, he suggested, could happen if employees signed nondisclosure agreements, as noted by Wired.

Which is, in a way, the perfect encapsulation of the problem. Palantir's position seems to be: "Yes, we do sensitive work. No, we can't tell you about it. But trust us, it's fine. And if you want to know more, you'll have to sign away your ability to talk about what you learn."

The Staffing Implications

When you have internal resistance from employees who built your products, you have a staffing problem. Palantir knows this. That's why Akash Jain's email about the new DHS deal included a recruiting pitch. "If you are interested in helping shape and deliver the next chapter of Palantir's work across DHS, please reach out," he wrote. Then, in a line that probably sounded better in his head: "There will be a massive need for committed hobbits to turn this momentum into mission outcomes," as highlighted by CBS News.

Yes, Palantir actually calls its employees "hobbits" because of founder Peter Thiel's apparent obsession with Lord of the Rings. Whether that affectionate nickname still feels affectionate when you're being asked to work on immigration enforcement remains unclear.

But the pitch reveals the real anxiety: Palantir is going to need significantly more engineering talent to build out the expanded DHS work that this $1 billion agreement enables. And they need that talent to come voluntarily, from employees who have real choices about where to work.

In Silicon Valley, there's still a significant number of engineers who actually care whether the work they do contributes to human flourishing or human suffering. Getting them excited about building better deportation technology is going to be a tough sell.

Estimated data shows that DMV records, financial transactions, and arrest records each contribute significantly to Palantir's ImmigrationOS tracking capabilities. Estimated data.

The Expansion Problem: What This $1 Billion Deal Actually Opens

When you read Akash Jain's email about the new DHS blanket purchase agreement, one thing jumps out immediately: Palantir is not just expanding immigration enforcement. It's positioning itself to become a core technology provider across the entire Department of Homeland Security.

From ICE to FEMA to CISA

The explicit agencies Jain mentions as potential customers for this expanded work include:

-

FEMA: The Federal Emergency Management Agency, which handles disaster response. Why would FEMA need Palantir's immigration-tracking systems? Possibly they wouldn't. But Palantir's core capability is data integration and analysis. A hurricane hits, suddenly FEMA could use Palantir's systems to track displaced people, coordinate resources, analyze damage patterns.

-

TSA: The Transportation Security Authority runs airport security. Palantir's tools could identify security threats, integrate passenger data, cross-reference watch lists. This is less of a stretch than FEMA, but the implications are still massive.

-

Secret Service: Presidential protection and financial crime investigation. If the Secret Service integrates Palantir's systems, it would mean the technology becomes central to protecting the president and investigating counterfeiting. It would give Palantir visibility into security operations at the highest levels of government.

-

CISA: The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Here, you can see how Palantir's technology could genuinely fit: helping identify cybersecurity threats across critical infrastructure. But it also means Palantir becomes entangled in the security of the nation's most important systems.

The Scope Creep Problem

Once you've given one vendor a $1 billion purchasing agreement, all sorts of things become possible that wouldn't have been explicitly authorized. A DHS official at FEMA wants Palantir to analyze disaster relief distribution? They can order it. Someone at the Secret Service thinks Palantir's tools could help with counterfeiting investigations? They can order it. A cybersecurity team at CISA wants to experiment with using Palantir for threat detection? They can order it.

None of these decisions have to go through competitive bidding. None of them require explicit congressional approval. They're just... enabled by the purchasing agreement.

This is how you end up with a situation where a company designed to help ICE identify immigrants for deportation eventually has its tools integrated into nearly every aspect of homeland security operations. Not through some master plan, but through thousands of small decisions, each one individually defensible, that collectively add up to massive consolidation of power in a single vendor's hands.

The scariest part? If Palantir's systems become central to CISA cybersecurity operations, for example, then removing them becomes genuinely difficult. You'd have to replace them. Rebuild the integration with every agency that depends on them. It's technical lock-in, and it creates massive switching costs that make it nearly impossible for the government to switch vendors later.

The Privacy Concerns: What Critics Actually Worry About

When Akash Jain defended Palantir's immigration work in his email, he made an argument about privacy protections. Palantir's tools, he wrote, "help enable accountability through strict controls and auditing capabilities, and support adherence to constitutional protections, especially the Fourth Amendment."

This statement requires unpacking, because it reveals the fundamental disagreement between what Palantir says its tools do and what critics believe they actually enable.

The Fourth Amendment Question

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. In traditional constitutional terms, that means the government generally needs a warrant to search your home or seize your property. But the Fourth Amendment was written in 1791, before the digital age, before knowledge graphs, before the possibility of tracking millions of people simultaneously.

Does a knowledge graph that connects your financial records, your location history, your phone calls, and your HHS records constitute a "search" in Fourth Amendment terms? Arguably, yes. Should it require a warrant? Arguably, yes. Does the government actually get warrants before running Palantir queries on immigrants? Evidence suggests: frequently not, as highlighted by Britannica.

Palantir's argument is that their tools have "strict controls and auditing capabilities." Which means they have features that log who accessed what data and when. Audit trails are good. They make it possible to discover if someone misused the system. But they don't prevent the misuse from happening in the first place. An audit trail that shows an ICE agent improperly accessed data about a US citizen is useful for prosecution, but it doesn't un-search the data they accessed.

The Chilling Effect Problem

There's something else going on that's harder to measure but equally important. When people know they're being tracked, they change their behavior. If immigrants know that seeking healthcare might trigger their inclusion in a Palantir system designed to identify deportation targets, they might not seek healthcare. If people know their phone calls are being integrated into immigration enforcement data, they might not call family members. If parents know that applying for benefits for their children might flag them in a system, they might not apply.

This is called the "chilling effect," and it's one reason why privacy experts are concerned about surveillance technology even when it's used "correctly." The surveillance itself, independent of whether it catches anyone, changes behavior in ways that can be harmful.

An undocumented parent who doesn't seek healthcare because they're afraid of deportation is experiencing a real harm, even if they never actually get deported. They're experiencing illness untreated. Their children are experiencing a parent under constant stress. These are real consequences of surveillance systems, even when the systems function exactly as designed.

The Data Quality Problem

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: Palantir's systems are only as good as the data they ingest. And government databases are notoriously full of errors.

DMV records have false positives. Financial transaction data can be misinterpreted. Facial recognition systems, which are likely integrated into this system, have accuracy rates that vary by race, with studies showing error rates up to 35% for some demographics when compared to others.

When you build a knowledge graph that multiplies probabilities across thousands of data points, small errors compound. A mistaken address in one database, combined with an incorrect name match in another, combined with a coincidental phone number pattern, could theoretically add up to a false positive that flags an innocent person as a deportation target.

Palantir says it has safeguards. But once a person is flagged by this system, they're in ICE's sights. Proving your innocence is harder than not being flagged in the first place.

Critics express high concern over Fourth Amendment violations and lack of warrants in Palantir's operations, with significant worries about audit trail limitations and behavioral changes. (Estimated data)

The Regulatory Response: Are Lawmakers Actually Doing Anything?

One might hope that Congress, having noticed that a single company is now essentially directing immigration enforcement policy, would do something about it. The evidence so far is mixed.

Congressional Attention and Inattention

Several Democratic Congress members, particularly those interested in immigration and civil liberties issues, have raised concerns about Palantir's work with ICE. Pramila Jayapal and other progressive representatives have called for investigations. But "called for investigations" is Washington-speak for "probably won't happen without a lot more public pressure," as noted by Wired.

The challenge is that Palantir has significant political support. The company has contributed to both Democratic and Republican causes. Its founder, Peter Thiel, has ties to conservative movements. Its technology is genuinely useful for government operations, even if it's also genuinely concerning for civil liberties. Politicians don't want to be seen as "soft on immigration" or "opposing security," even when they're uncomfortable with how immigration security is being handled.

So what you get is a kind of polite disagreement. Some Congress members express concern. They send letters. They hold hearings where Palantir executives testify vaguely about their commitment to privacy and civil liberties. Nothing changes.

The Executive Branch Constraints

The executive branch, theoretically, has more direct control over government spending. An administration that wanted to limit Palantir's role in immigration enforcement could do so. But here's the problem: Palantir's systems are now deeply integrated into ICE operations. ICE actually runs on Palantir software in many cases. To remove it, you'd have to replace it with something else, and you'd have to do it while maintaining immigration enforcement operations.

It's technically possible, but politically and bureaucratically expensive. And for an administration focused on immigration enforcement, Palantir's tools are actually valuable. They work. They find people. If you're an administration that wants to prioritize immigration enforcement, Palantir is your company.

This is why the Biden administration didn't cancel the relationship, and why a Trump administration probably won't either, even as both make different rhetorical claims about immigration policy.

State-Level Alternatives

The most interesting regulatory action on Palantir has actually come from state governments, not federal ones. Several states have considered or passed legislation restricting how private data is shared with federal immigration enforcement. California, in particular, has limited data-sharing between state agencies and ICE. But here's the irony: Palantir's tools don't necessarily need state cooperation. They work with federal data. And there's limited state power to restrict federal agencies from accessing data sources that exist in federal databases.

What might actually matter is pressure on tech workers to refuse to work for companies doing immigration enforcement, combined with public pressure on government agencies themselves to limit the scope of surveillance. But that's not regulatory action. That's cultural pressure. And cultural pressure moves slowly.

Palantir's Defense: The Company's Own Argument

It's worth actually engaging with Palantir's position, rather than just dismissing it, because the company does make some arguments worth taking seriously.

The Legality Argument

Palantir's position is fundamentally that the company builds tools that help government agencies do what those agencies are legally authorized to do. ICE is legally authorized to enforce immigration law. Therefore, building tools that make ICE more effective is not, according to Palantir, ethically problematic.

This is a version of the "we're just a vendor" defense that many technology companies use. We didn't write immigration law. We don't decide who gets deported. We just made the tools more efficient.

There's something to this argument. Companies do serve government. Palantir isn't uniquely evil for doing so. Microsoft sells software to ICE. Amazon provides cloud services to federal agencies. The question of whether private companies should serve government functions is a separate question from whether Palantir specifically has done something wrong.

The Effectiveness Argument

Palantir also argues that its tools, by making immigration enforcement more efficient and more data-driven, actually lead to better outcomes. The company's Jain wrote that Palantir's systems "help enable accountability through strict controls and auditing capabilities."

The idea here is that human immigration agents, left to their own devices, might rely on hunches, stereotypes, or biases. Palantir's data-driven systems, by contrast, make enforcement more systematic, more auditable, more accountable. A decision made based on data and logged in Palantir's system can be reviewed. A decision made on a hunch cannot.

There's a certain logic to this. Data-driven decisions are, in principle, more transparent and auditable than intuitive ones. But the assumption embedded here is that data is neutral and bias-free. In practice, data reflects the biases of the systems that generated it and the biases of the people who set up the algorithms.

If a system is trained on historical enforcement data, and historical enforcement has targeted certain communities more heavily, then the system will learn to target those communities. You haven't eliminated bias, you've just made it harder to see.

The Transparency Argument

Final defense: Palantir says it's actually more transparent than alternatives. The company has published reports on its approach to government technology. It's hired privacy professionals like Courtney Bowman to oversee civil liberties considerations. It's engaged with civil liberties groups, even if these conversations haven't been entirely satisfying.

Compare this to other defense contractors or security companies that simply don't discuss their government work at all. At least Palantir is willing to have the conversation.

The counterargument, of course, is that transparency that doesn't include real information isn't actually transparency. Saying "we have strict controls" without explaining what those controls are, or without independent audits of those controls, isn't really transparency. It's transparency theater.

Estimated data suggests Palantir's technology could be evenly distributed among DHS agencies, with TSA potentially having the highest utilization due to security needs.

The Technical Reality: How Surveillance Systems Actually Work

To understand what Palantir's tools are actually capable of, it helps to understand the technical architecture that makes them possible.

Data Integration as the Core Problem

Palantir's fundamental capability is data integration. The company takes disparate data sources—immigration records, financial records, phone records, location data, health records—and connects them into a unified system where an analyst can search across all of them simultaneously.

This is genuinely hard to do technically. Data in the DMV might be formatted differently from data in a phone company's system. Information about a person in an immigration database might use a slightly different spelling of their name than in a bank's fraud detection system. Building systems that can integrate all this while managing errors and inconsistencies is non-trivial engineering.

But here's what makes it powerful: once you've integrated all this data, you can ask questions you couldn't ask before. Not "is this person in our immigration database," but "who is this person connected to, where have they been, what patterns do their financial transactions show, who calls them on the phone."

These are network analysis questions. They require integrated data. And they're impossible without systems like Palantir's.

The Machine Learning Layer

Once Palantir has integrated all this data, it can apply machine learning algorithms to identify patterns. These algorithms can do things like:

- Predict likely locations: Based on historical behavior, phone location data, and known associates, where is a particular person likely to be at a particular time?

- Identify communities: Who is in a social network with someone you're interested in? Who are the connectors between different groups?

- Pattern matching: Which financial transactions look suspicious? Which phone call patterns match known smuggling routes?

- Risk scoring: Given a bundle of characteristics, how likely is a person to commit a particular crime or violate a particular law?

None of these, individually, is necessarily problematic. The issue is that when you combine them, you get a system that can identify people for deportation before they've done anything wrong, based on predictions about what they might do.

The Interface Layer

What an ICE agent actually sees when using Palantir is a map interface. They see neighborhoods where "persons of interest" are concentrated. They see networks of connections. They see historical patterns. The system is designed to guide enforcement decisions.

But here's what they might not see: how certain the system actually is about any particular prediction. An interface that says "deportation targets likely in this neighborhood" is more compelling than one that says "our algorithms think there's a 23% chance there are targets in this neighborhood." Human psychology means that information presented as confident has more impact than information presented as uncertain, even if both are equally true.

Interface design in surveillance systems is a civil liberties issue that doesn't get enough attention. How you present uncertainty, how prominent certain information is, how much context you provide, all of that shapes how the tool is actually used.

The International Dimension: Palantir's Global Surveillance Business

It's worth noting that Palantir's immigration work isn't just a US thing, and this DHS deal isn't just about the US.

Palantir's Foreign Government Clients

Palantir has, over the years, contracted with governments around the world to build surveillance systems. The company has worked with contractors in the Middle East. It's worked with governments on border security. While the company is careful not to explicitly market surveillance capabilities, the tools it builds are, in many cases, used for surveillance.

The worry from civil liberties groups is that Palantir is essentially exporting surveillance infrastructure globally. A tool built for immigration enforcement in the US can be redeployed for political surveillance in another country. Technology doesn't have inherent morality, but the ways it's used do.

The Export Control Question

There's a legal question here about whether Palantir's tools should be subject to export controls. The US has export controls on certain technologies, particularly military and surveillance technologies, based on the idea that some tools are too dangerous to let other countries have. But commercial data analytics software isn't typically restricted.

So Palantir can sell similar systems to allied governments, and potentially even to companies in other countries that do business with governments. The tools end up globally distributed, even if Palantir itself isn't explicitly selling them to every regime you'd worry about.

Estimated data suggests that ethical concerns are the primary issue among Palantir employees regarding ICE collaborations, followed by transparency issues.

What Happens When Surveillance Becomes Routine

One of the scarier aspects of the Palantir situation is how normal it's becoming. A billion-dollar government contract with a defense contractor used to be news. Now it's just business as usual. Congress doesn't investigate. Regulators don't block it. Tech workers grumble on internal Slack channels.

This normalization is actually the real danger. We're sliding into a world where certain companies have integrated so deeply into government functions that replacing them becomes impossible, and their business model becomes simply "help government operate more efficiently in ways that are increasingly invasive."

What prevents this from being a dystopian nightmare is not technology companies being good actors or government agencies being restrained. It's public awareness and cultural pressure. When people understand what's happening and object to it, change becomes possible. When it's hidden behind procurement processes and nondisclosure agreements, change becomes unlikely.

This is why the internal tension at Palantir actually matters. It's one of the few checks on the system. When employees refuse to participate, the company has to either change its business model or lose talented people. When the public objects, politicians eventually have to respond. Neither of these forces is particularly strong right now, but they're the ones that exist.

The Future: What Comes After This Deal

Looking forward, there are several possible futures here, and they depend largely on choices that haven't been made yet.

Scenario One: Deepening Integration

In this scenario, Palantir succeeds in expanding across DHS. The company's tools become central to operations at FEMA, TSA, CISA, and the Secret Service. Palantir becomes not just another defense contractor, but a core piece of government infrastructure. The company becomes even less replaceable, and the political costs of any regulation become even higher.

In this scenario, the company eventually also expands internationally. Foreign governments adopt similar systems. Within 15 years, it's normal for governments to have real-time visibility into the movements of millions of people. Immigration enforcement, border security, and counter-terrorism all become more efficient and more comprehensive.

This is probably good news for people who prioritize security and bad news for people who prioritize privacy. It might catch more criminals. It will definitely track more citizens.

Scenario Two: Regulatory Pushback

In this scenario, public awareness about what Palantir's systems actually do, combined with pressure from civil liberties groups and tech workers, eventually leads to regulation. Perhaps Congress passes a law limiting how government agencies can use predictive systems. Perhaps there's a national data privacy law that constrains the data available to feed into these systems. Perhaps a new administration decides to reduce immigration enforcement and therefore reduces Palantir's role.

In this scenario, Palantir's US government business shrinks, but the company pivots to international markets and commercial customers. The company might eventually be less integrated into US government operations, but surveillance technology itself becomes more prevalent globally and commercially.

Scenario Three: The Whistleblower Moment

In this scenario, either a Palantir employee or a government official leaks substantial details about how Palantir's systems actually work and what abuses they've enabled. This becomes a major scandal. Congressional hearings actually investigate, rather than just asking questions. Journalists expose specific cases where Palantir's tools led to wrongful deportations or targeting of US citizens.

In this scenario, public outrage actually drives policy change. Perhaps the contract gets terminated. Perhaps Palantir is restricted from working with ICE. Perhaps a broader reckoning happens about surveillance and government technology.

No one knows which of these scenarios is most likely. But the DHS deal suggests that without significant external pressure, Scenario One seems to be the path Palantir is already on.

What Should Happen: Regulatory Framework Recommendations

If policymakers took this seriously, what would they actually do?

Requirement One: Public Audits of Surveillance Systems

Government agencies should be required to publish regular, independent audits of surveillance systems they use. Not classified audits that only people with security clearances can see. Public audits that citizens and their representatives can actually evaluate.

These audits should include:

- False positive rates for system predictions

- Demographic breakdown of who is targeted by the system

- Historical cases where the system was wrong with documented consequences

- Comparison between system predictions and actual outcomes

Transparency is a basic requirement for a democratic society. If the government is using surveillance tools to locate and deport people, citizens have a right to know how accurate those tools are and whether they work as claimed.

Requirement Two: Competitive Rebidding for Expansions

Rather than blanket purchase agreements that last five years, government could require competitive rebidding every 18 months. This would prevent vendor lock-in and ensure that alternatives are regularly evaluated.

It would also create incentives for competitors to develop better tools. If Palantir knows that every 18 months their contract could be competed away, they have stronger incentive to actually innovate and improve their systems.

Requirement Three: Warrants for Individual Queries

Companies like Palantir should be required to log when government agents access their systems, what queries they run, and what data they pull. But more importantly, certain high-sensitivity queries should require a warrant.

When an agent wants to search across the immigration records, financial records, and location history of a specific person, that should require a warrant. It's a search in Fourth Amendment terms, and it should require judicial approval.

Requirement Four: Prohibition on Certain Data Integrations

Health data and financial data for individuals should probably be prohibited from integration with immigration enforcement systems. The chilling effect of knowing your healthcare might trigger immigration enforcement is simply too strong.

Similarly, data from voluntary benefit programs should be separated from enforcement data. If you're seeking benefits for your children, that shouldn't automatically feed into a system that targets you for deportation.

Requirement Five: Technical Accountability

Software systems used for surveillance should be subject to regular technical audits by independent experts. Not by the companies that built them, but by external parties that have genuine expertise in machine learning, security, and database systems.

These audits should specifically look for:

- Bias in training data or algorithmic decision-making

- Incorrect integration of data from different sources

- False positive rates

- Cases where system errors led to real-world harms

The Economic Side: Why Palantir Matters Beyond Immigration

It's worth understanding Palantir as more than just an immigration enforcement company, because the immigration work is actually just one piece of a much larger business.

Government Revenue vs. Commercial Revenue

Palantir has been historically dependent on government contracts. The company was founded with CIA funding and has long been primarily government-focused. But in recent years, the company has been trying to expand into commercial markets.

However, government contracts are actually Palantir's crown jewels. They're more profitable, more stable, and they serve as references for everything else the company does. When Palantir can say "we work with the US government," that carries weight. When the company can point to having solved complex data integration problems for government agencies, that becomes a selling point for commercial customers.

The $1 billion DHS deal matters not just for the money, but because it cements Palantir's position as the company the US government trusts with its most sensitive data. That position is worth far more than the billion dollars itself, as noted by Wired.

The Defense Industrial Complex Connection

Palantir, while not traditionally thought of as a defense contractor in the way that Lockheed Martin or Raytheon are, is absolutely part of the defense ecosystem. The company's founders have ties to the intelligence community. The company's advisory board includes government officials. The company benefits from government spending and, in return, gives the government capabilities it couldn't build internally.

This relationship creates a kind of immunity from criticism. Question Palantir's immigration work? Well, the company has national security implications. Question what the company charges the government? Well, the company is doing sensitive work that few companies can do.

It's a classic defense contractor dynamic: create a capability that the government becomes dependent on, become essential to government operations, therefore become politically untouchable.

What Workers Actually Think: The Internal Perspective

One of the most interesting aspects of the Palantir situation is the internal staff conflict. What are Palantir employees actually thinking and feeling about their work?

The True Believers

Not all Palantir employees are uncomfortable with immigration work. Some genuinely believe in it. They think immigration enforcement is legitimate, that ICE's mission is necessary, and that making ICE more efficient is good policy.

For these employees, the recent scrutiny has been annoying and unfair. They're doing important work for a legitimate government agency. Why should they apologize for that?

Palantir's leadership is betting that there are enough true believers to staff the expanded work that the $1 billion deal enables. But the company is also clearly worried that there aren't quite enough, which is why Jain's email included a recruiting pitch.

The Principled Objectors

On the other end of the spectrum are employees who think immigration enforcement as currently practiced is fundamentally unjust. To these employees, making deportations more efficient isn't a good thing. It's participating in a system they find morally wrong.

For these employees, working at Palantir has become uncomfortable. The company's defense of its immigration work hasn't convinced them. The opportunity to sign an NDA and learn more about what they've been building actually sounds worse, not better.

These are the employees most likely to leave. And smart tech companies actually care when idealistic engineers leave, because those tend to be the best engineers.

The Middle Ground

Most employees are probably somewhere in the middle. They find the immigration work ethically troubling but not so troubling that they're willing to sacrifice a high-paying job at a prestigious company over it. They'd prefer if Palantir moved away from immigration enforcement, but they're not going to actively resist.

For Palantir, this middle group is actually the important one. If you can keep them relatively satisfied, the company can operate without massive staff revolt. But if the company pushes too hard on the immigration expansion, some of this middle group moves to genuine objection.

International Precedent: How Other Countries Handle Surveillance

The US isn't the only country dealing with government surveillance and the role of private companies in enabling it. Looking at how other democracies are handling similar issues might be instructive.

The EU Approach: Stronger Privacy Regulation

Europe has generally moved toward stronger privacy protections through regulations like GDPR. These regulations constrain how data can be collected, shared, and used. They require consent in many cases. They give individuals rights to access and delete their data.

Under GDPR, some of what Palantir does in the US would be legally questionable. The integration of health data with enforcement data, for instance, would face significant regulatory scrutiny. The lack of individual consent for data sharing would be problematic.

European countries also tend to have stronger public oversight of government surveillance. When intelligence agencies want to implement surveillance systems, there's often public debate and regulatory review.

The tradeoff is that European security agencies sometimes complain that strong privacy protections make their jobs harder. But the European democratic consensus seems to be that privacy is worth some security costs.

The Chinese Approach: Surveillance Without Apology

At the opposite extreme, China has implemented surveillance systems at scale, with relatively little concern for privacy or consent. Facial recognition, behavioral tracking, and predictive systems are deployed openly.

The interesting thing about China from a Palantir perspective is that Palantir has been less present there. Chinese companies like Alibaba and Tencent have built the surveillance infrastructure. China built its own surveillance capability rather than outsourcing to foreign companies.

But China's approach is instructive for what could happen if surveillance systems become too consolidated. In China, the state has near-total visibility into citizen behavior. There's almost no privacy. And the system is used not just for law enforcement but for political control.

The Middle Ground: Canada and UK

Canada and the UK have surveillance systems that are more extensive than Europe's but more privacy-protective than China's. Both countries have data protection regulations, though less strict than GDPR. Both have public debate about surveillance. Both have legal frameworks constraining government access to personal data, though the frameworks are imperfect.

Canada, in particular, has been dealing with the exact question of whether to allow US companies to handle Canadian citizen data for US law enforcement purposes. The answer has been increasingly "no, we should build our own systems."

FAQ

What is a blanket purchase agreement and why is it different from other government contracts?

A blanket purchase agreement (BPA) is a pre-approved contract that allows a government agency to purchase up to a specified dollar amount from a selected vendor without going through competitive bidding for each individual purchase. Unlike traditional contracts where agencies must compete bids for each new project, a BPA simplifies procurement by pre-approving a vendor. In Palantir's case, DHS can now purchase up to $1 billion in services over five years from Palantir without requiring competitive rebids for new projects. This removes the market competition that typically helps keep prices reasonable and incentivizes vendors to innovate.

How does Palantir's technology actually identify immigrants for enforcement?

Palantir uses a technology called a "knowledge graph" that integrates data from multiple sources including immigration records, financial transactions, phone data, location information, and health records. The system connects these data points to create networks showing relationships and patterns. Machine learning algorithms then analyze these networks to predict locations where people matching certain criteria might be found or to identify communities with similar characteristics. Tools like Immigration OS provide real-time tracking, while ELITE creates geographic maps showing concentrations of potential enforcement targets, allowing ICE agents to focus operations in specific areas.

What are the main privacy concerns about these surveillance tools?

Privacy advocates raise several concerns: first, that Fourth Amendment protections may be violated because the government typically doesn't get warrants before running these searches; second, that chilling effects occur when immigrants avoid healthcare or benefits because they fear surveillance; third, that data quality issues and machine learning bias can create false positives leading to wrongful targeting; and fourth, that the integration of health and benefit data with enforcement systems creates perverse incentives against seeking help. Additionally, the opacity of these systems makes it difficult to verify whether they actually work as claimed or whether they disproportionately target certain communities.

Why are Palantir employees concerned about immigration work?

Palantir workers, particularly after the January 2025 death of Alex Pretti, began asking difficult questions about how the company's tools actually power immigration enforcement. Many employees were uncomfortable that the company was not transparent about how its systems are used, what harms they enable, or what alternatives exist. When CEO Alex Karp's video response to employee concerns largely avoided direct questions and suggested employees would need to sign NDAs to learn more, staff frustration increased. The situation created a conflict between employees who had moral objections to immigration enforcement and company leadership that wanted to expand that work.

What would stronger regulation of government surveillance look like?

Effective regulation would include: public, independent audits of surveillance systems showing false positive rates and demographic targeting patterns; competitive rebidding for government contracts every 18 months rather than long-term non-competitive agreements; warrant requirements for sensitive database queries affecting individuals; prohibition on integrating certain sensitive data types like health records with enforcement systems; and regular technical audits by independent experts to identify bias and errors. Such measures would increase transparency, prevent vendor lock-in, and create accountability that currently doesn't exist in classified government surveillance operations.

Could other companies replicate what Palantir does for immigration enforcement?

Technically, yes. Other data analytics companies could potentially build similar systems, and some have tried. But Palantir has significant advantages: decade-long relationships with DHS agencies, integrated systems already deployed, demonstrated capability with complex government data, and the network effects of being the established standard. Replacing Palantir would require DHS to migrate data and rebuild workflows with a new vendor, which is technically expensive and politically difficult. This switching cost is actually one of Palantir's most valuable assets. The company's dominance isn't based purely on technical superiority but on being entrenched in critical government operations.

What role did political considerations play in approving this $1 billion deal?

The deal seems to have had political support across the government, which isn't surprising given that both Democratic and Republican administrations prioritize immigration enforcement, though they may use different rhetoric about it. Congress hasn't objected significantly despite some oversight concerns raised by progressive representatives. The combination of Palantir's effectiveness for immigration enforcement, the company's political connections, and the general political bipartisan consensus around supporting immigration enforcement created an environment where the deal proceeded without significant obstacles. A future administration interested in reducing immigration enforcement pressure could theoretically terminate the relationship, but doing so would be technically and politically complex.

What international implications does Palantir's expansion have?

Palantir has contracts with foreign governments for border security and surveillance work. The surveillance infrastructure the company builds in the US could theoretically be exported to allied nations, and similar systems could be built internationally. This raises questions about whether US technology is being used to enable surveillance or enforcement practices in other countries that might not meet US legal or democratic standards. Additionally, as the US becomes known for sophisticated government surveillance enabled by commercial companies, it becomes harder for the US to criticize similar practices in other countries. The global precedent matters for international norms around surveillance and privacy.

How might this deal affect other government agencies beyond DHS?

The blanket purchase agreement opens doors for other federal agencies to adopt Palantir systems if they choose. While the agreement is specific to DHS agencies, the successful use of Palantir's technology in immigration enforcement could influence thinking at other departments considering data integration solutions. The precedent of a single vendor holding a billion-dollar government contract without ongoing competitive pressure might also influence how other agencies structure their contracts with large technology providers. This could shift government procurement more toward long-term non-competitive agreements with established vendors rather than maintaining competitive markets.

Conclusion: The Palantir Moment as a Referendum on Surveillance Democracy

The $1 billion Palantir contract with DHS is one of those moments where you can see a fundamental choice point in how modern democracies actually work. It's not as dramatic as other historical moments, but it might be equally consequential.

We're in a period where technology has made certain things possible that weren't possible before. Mass surveillance at scale. Real-time tracking of millions of people. Predictive systems that can identify and locate individuals based on probabilistic analysis of massive amounts of data.

The question is: do we want to live in that world? And if we don't, what are we actually willing to do to prevent it?

Because the uncomfortable truth is that we can't prevent it through technology. There's no technological defense against government surveillance. You can encrypt your messages, but the government can see your financial transactions. You can avoid social media, but the government has your phone records. You can hide where you live, but you still need to get a drivers license, see a doctor, apply for benefits.

The only way to actually prevent surveillance dystopia is through regulation, through political choices, through cultural values that say "no, even if you technically can track everyone, we're not going to." And those things are hard. They require sustained political pressure. They require voters to care about privacy enough to make it an election issue. They require tech workers to be willing to leave jobs over principle. They require journalists to keep reporting on what's happening.

Palantir's success at building tools for immigration enforcement and negotiating a $1 billion contract represents a kind of failure of all those mechanisms. The political pressure didn't stop it. The tech worker resistance wasn't strong enough. The press reported on it but it didn't become a major scandal. The regulatory agencies didn't block it.

So now we have a situation where, five years from now, Palantir's tools will probably be integrated into even more government agencies. Immigration enforcement will be more efficient. Other surveillance applications will presumably expand. And it will all seem normal because we'll have gradually gotten used to it.

This is how surveillance becomes normalized. Not through one dramatic decision, but through thousands of smaller decisions, each one individually defensible, that collectively add up to something nobody actually wanted.

The question now is whether anything changes. Whether civil liberties groups manage to make this a bigger political issue. Whether a whistleblower emerges with detailed information about harms caused by these systems. Whether the internal staff conflict at Palantir reaches a breaking point. Whether Congress actually investigates, rather than just asking questions.

Or whether we just move forward into a world where immigration enforcement is more efficient because the government can track people more effectively, and we accept that as normal, and move on to the next technology, and the next, until we're living in the kind of surveillance state that we would have thought impossible thirty years ago.

These are the stakes of the Palantir moment. And they matter far more than billion dollars in government contracts, important as those are.

Key Takeaways

- Palantir's $1 billion blanket purchase agreement with DHS removes competitive bidding and lets agencies skip the bidding process for services up to that dollar amount

- The company built ImmigrationOS providing real-time tracking of immigrants and ELITE system creating maps of deportation targets using integrated health, financial, and location data

- Internal Palantir employees are increasingly uncomfortable with immigration enforcement work, creating staff retention challenges that the company is trying to address with recruiting pitches

- The agreement opens doors for Palantir to expand beyond ICE into FEMA, TSA, the Secret Service, and CISA, creating potential government-wide technology consolidation

- False positive rates compound when multiple data sources with individual errors are integrated, meaning surveillance systems may flag innocent people based on flawed algorithms

Related Articles

- ICE Agents' Secret Forum: What Federal Officers Really Think [2025]

- Ring's Search Party: How Lost Dogs Became a Surveillance Battleground [2025]

- DHS Subpoenas for Anti-ICE Accounts: Impact on Digital Privacy [2025]

- DHS Subpoenas to Identify ICE Critics Online [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]

- How ICE Shifted From Visible Raids to Underground Terror in Minneapolis [2025]

![Palantir's $1 Billion DHS Deal: What It Means for Immigration Surveillance [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/palantir-s-1-billion-dhs-deal-what-it-means-for-immigration-/image-1-1771522938184.jpg)