Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]

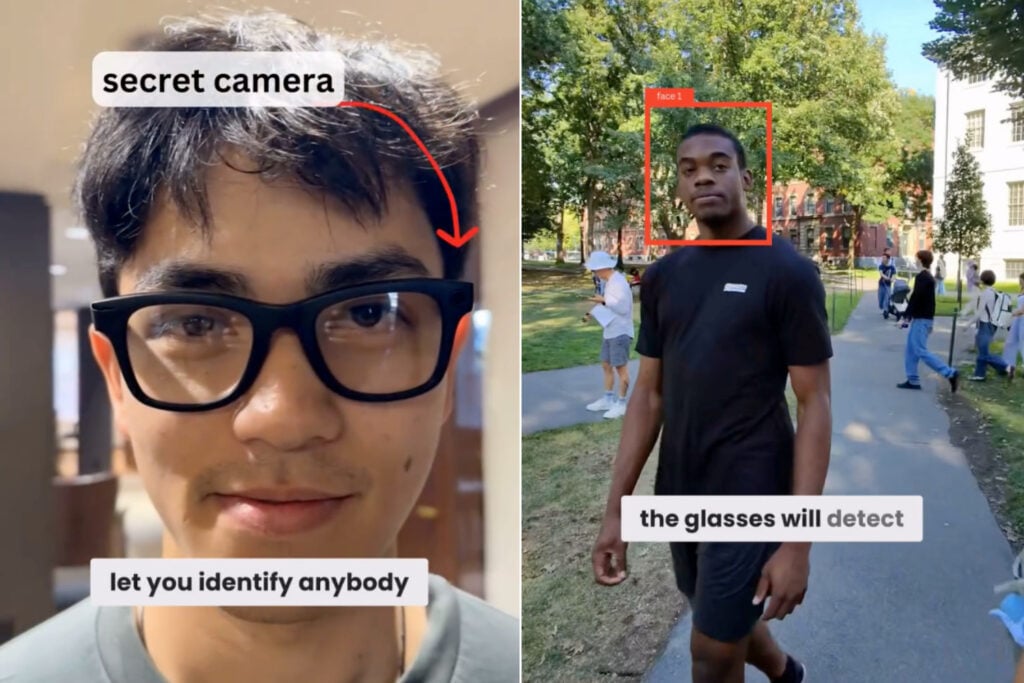

Meta is making a controversial move that would fundamentally change how we interact with people we meet. The company is reportedly planning to integrate facial recognition directly into its Ray-Ban smart glasses, potentially launching the feature as soon as 2025. This isn't some distant sci-fi scenario anymore—it's happening right now, and it raises some seriously uncomfortable questions about privacy, surveillance, and where technology is heading.

Let me be straight with you: facial recognition in wearable glasses is a powder keg. It combines two technologies that people are already nervous about, wraps them together, and puts them on your face. It's the kind of innovation that makes you wonder if we should, rather than whether we can.

But here's what's actually happening behind the scenes, what the technology does, why Meta thinks this is a good idea despite the backlash, and what it means for the rest of us.

TL; DR

- Meta's Name Tag feature could identify people and pull information from their social profiles using AI-powered facial recognition in Ray-Ban glasses

- Privacy concerns are massive: Critics worry about unauthorized identification, surveillance, and tracking in public spaces without consent

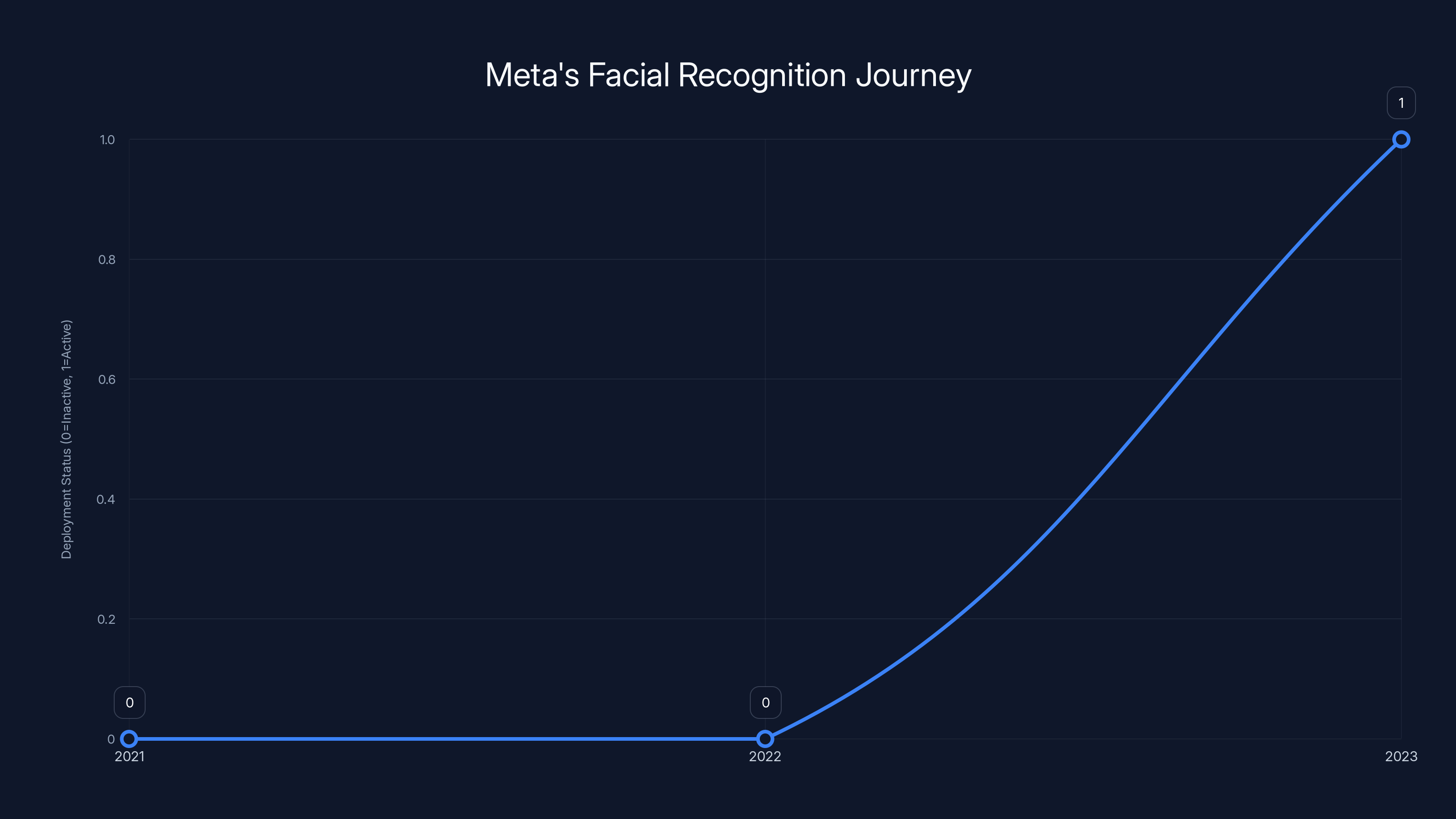

- Meta shelved this before: The company abandoned facial recognition plans for first-generation smart glasses after pushback, now reviving them

- Launch window is tight: Internal documents suggest Meta plans a 2025 rollout, possibly targeting a politically distracted environment

- Not full surveillance: Meta claims it won't enable universal facial recognition—it'll only identify people you're already connected to or public Instagram accounts

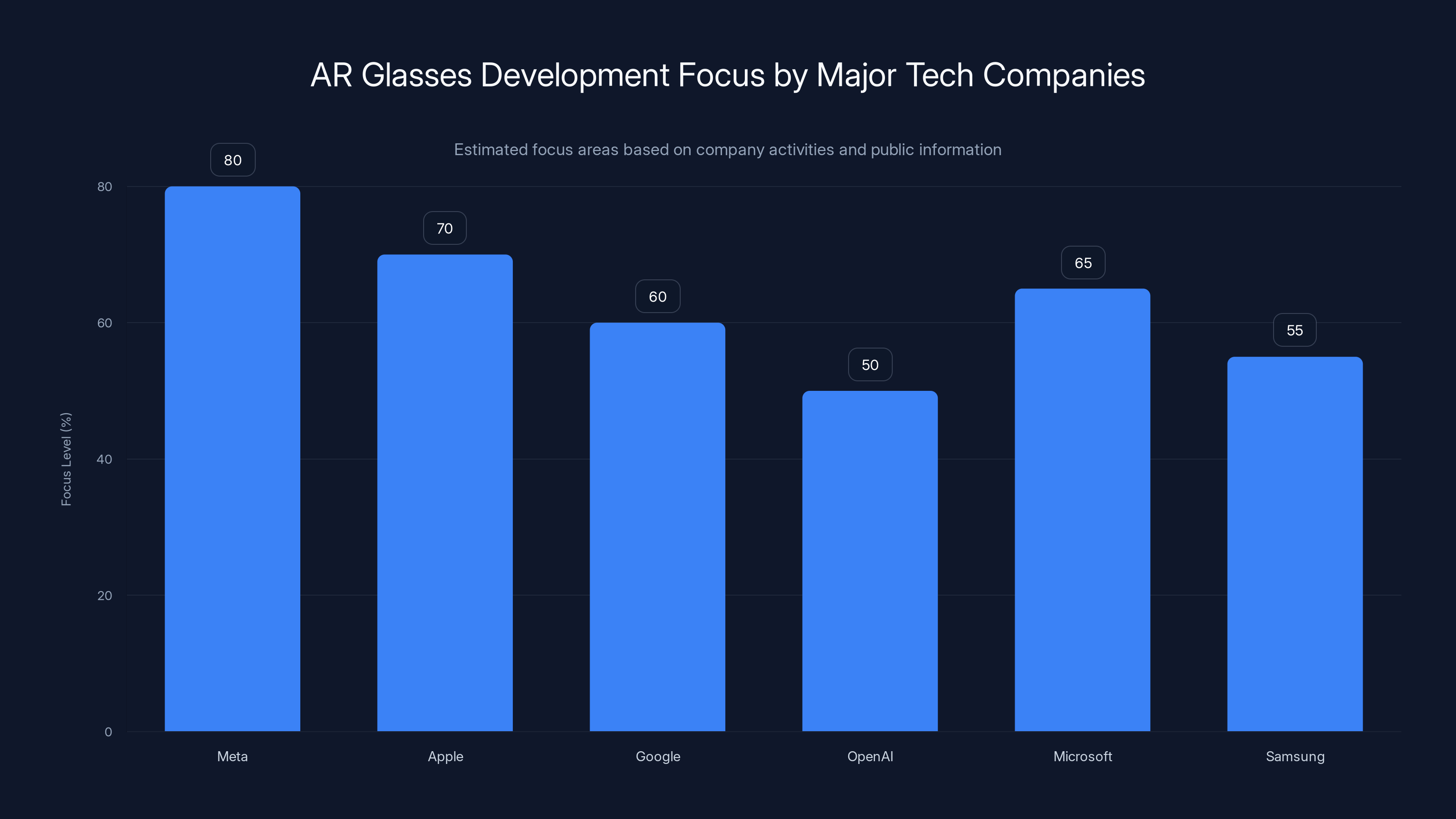

Meta leads in AR glasses development focus, closely followed by Apple and Microsoft. Estimated data based on company activities.

What Is Meta's Name Tag Feature?

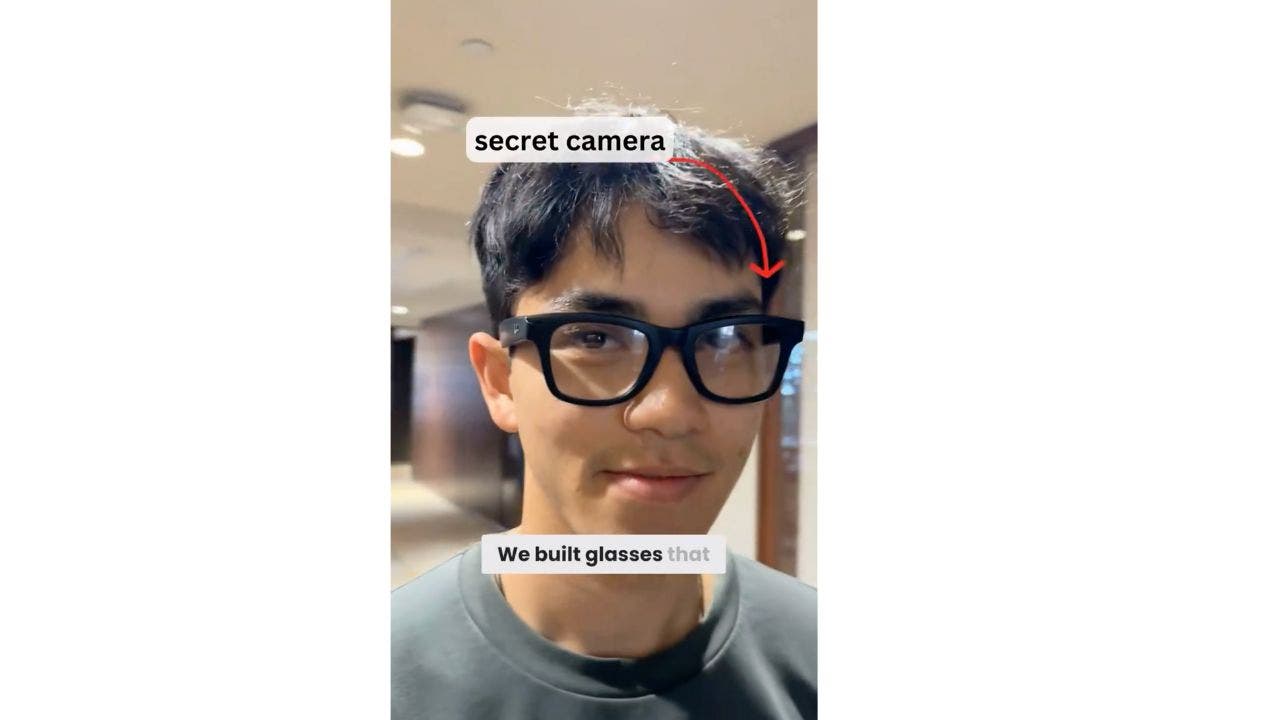

Meta's internal codename for this project is "Name Tag," and it's exactly what it sounds like. Imagine pointing your Ray-Ban smart glasses at someone and instantly knowing who they are, what they do, and what they've shared publicly online. The glasses would use on-device AI to recognize faces in real-time and cross-reference them against Meta's vast database of user profiles.

The feature is designed to work with faces of people you're already connected to through Instagram, Facebook, or WhatsApp. In theory, you could look at a colleague across a conference room and automatically see their profile information without asking them directly. For strangers, Meta is considering showing information from public Instagram accounts—essentially pulling data that's already publicly available but aggregating it in a way that's never been possible before.

Here's the technical side of how this would actually function. The glasses have built-in cameras constantly capturing video of the world in front of you. When you activate the Name Tag feature, the device runs facial recognition algorithms on that video stream. These algorithms convert faces into mathematical representations (called embeddings), which are then matched against Meta's database of known faces. The entire process happens on the device itself, which Meta says is a privacy feature—the actual face data doesn't leave the glasses.

But here's the catch: while the face data might stay local, the identification results and profile lookups absolutely require sending information to Meta's servers. Your glasses know who you're looking at, and Meta knows that you're looking at them. That's the real privacy concern, and Meta's technical approach doesn't solve it.

The feature supposedly wouldn't enable truly universal facial recognition—you can't point your glasses at a random person on the street and get their entire identity and location history. Meta says it's limiting this to people in your social network or those with public profiles. But that distinction matters less when you consider how many people have Facebook or Instagram accounts, and how much information is technically public even when people don't realize it.

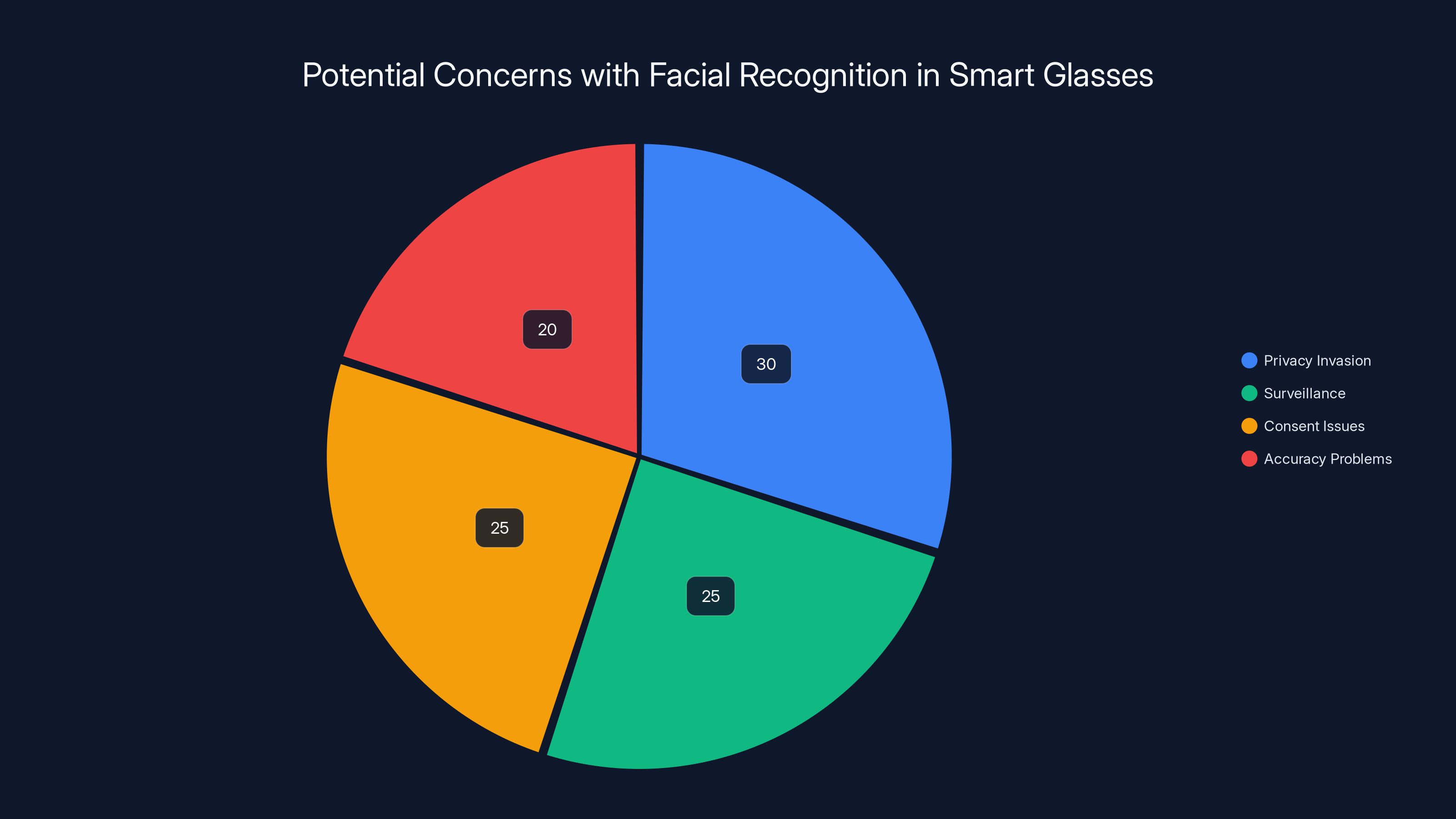

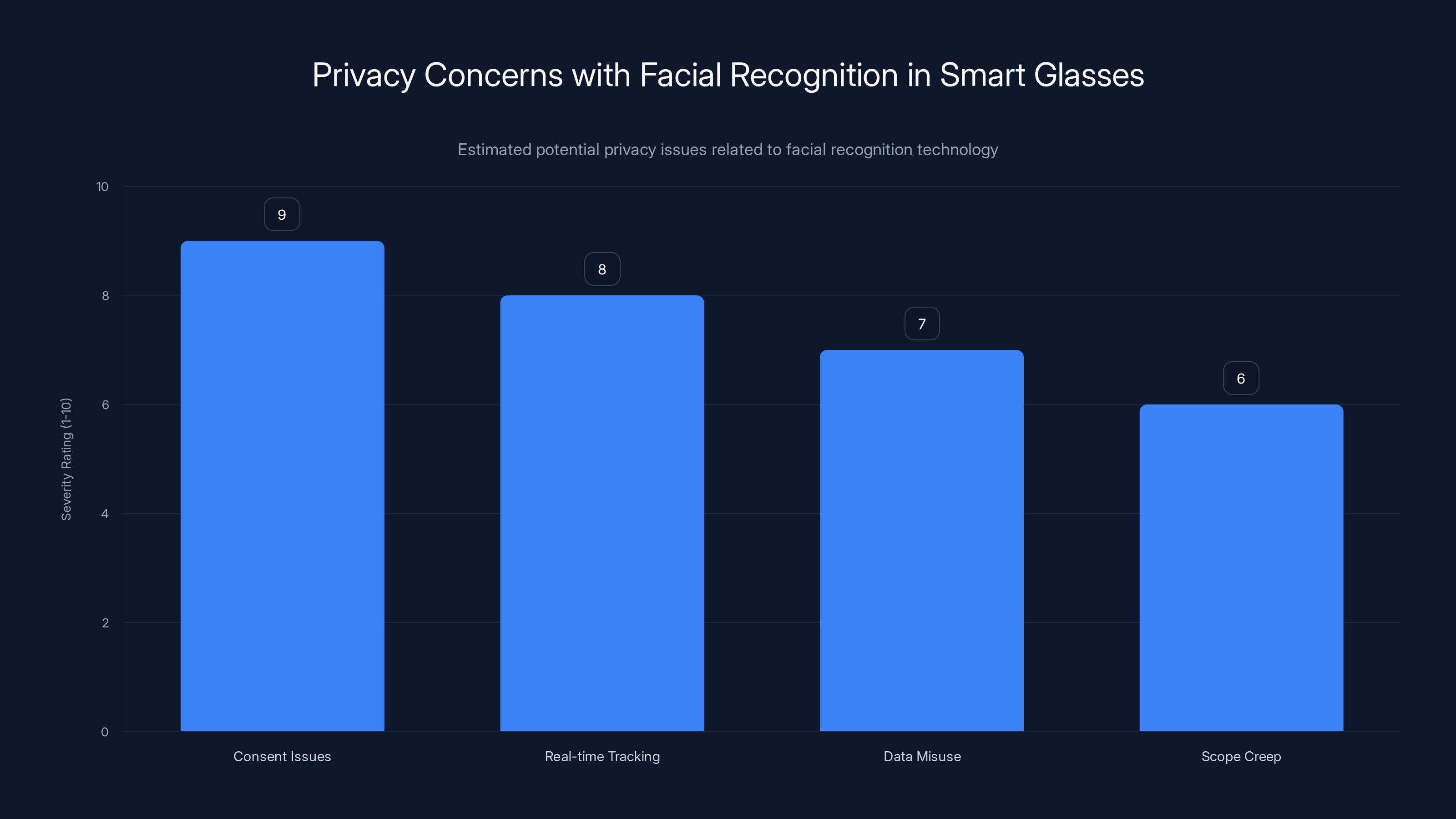

Privacy invasion and consent issues are the top concerns regarding facial recognition in smart glasses, followed by surveillance and accuracy problems. (Estimated data)

The History: Why Meta Abandoned Facial Recognition Before

This isn't Meta's first rodeo with facial recognition, and the previous attempt didn't go well. Back in 2021, Meta made a significant decision: it shut down Facebook's Face Recognition system entirely. This system had been used for automatically tagging people in photos and identifying faces in images posted to the platform.

The backlash was immediate and intense. Privacy advocates, regulators, and everyday users were alarmed by the idea of Meta automatically identifying people's faces without explicit permission. The company faced scrutiny from privacy groups, potential regulatory action, and negative media coverage that just wouldn't stop. The reputational damage was real, and Meta decided it wasn't worth it—at least not then.

But the story didn't end there. By 2023, Meta brought facial recognition back, repackaged as a tool for detecting scam ads and impersonation. This version was narrower in scope and had a consumer-facing benefit: it helped protect against fraudsters using celebrities' faces to sell fake products. Meta marketed it as a security tool, which made it easier to justify publicly.

The company expanded this feature beyond the US, rolling it out to Instagram and Facebook users in the United Kingdom, Europe, and South Korea. Each region had slightly different regulations and privacy concerns, but Meta found ways to make it work. The strategy was smart: make the feature useful for security, keep it focused on a specific problem, and gradually expand its reach.

When Meta first launched its Ray-Ban smart glasses in 2023, facial recognition was notably absent. That wasn't accidental. Internal documents show that Meta explicitly decided against including this feature in the first version, partly because they knew the privacy backlash would be significant. They wanted the product to establish itself, build market share, and create a loyal customer base before introducing the controversial feature.

Now, three years after shutting it down, Meta believes the timing is finally right to reintroduce facial recognition—this time through wearables. The company's reasoning is that smart glasses are a different form factor than social media platforms. People expect glasses to have cameras and AI features. The privacy concerns feel different to users when the technology is on your face rather than on Facebook's servers.

But that reasoning doesn't make the privacy problems go away. If anything, it makes them worse.

How the Technology Actually Works

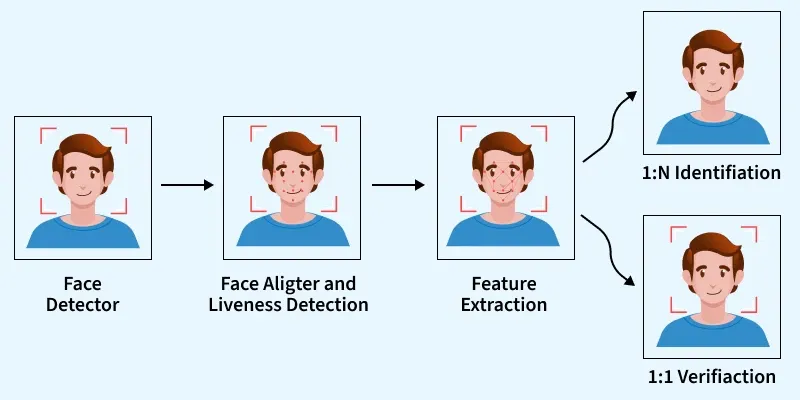

Understanding how Meta's Name Tag would function requires breaking down the facial recognition process into its core components. It's not magic, but it is sophisticated AI working in real-time on your glasses.

First, the glasses' camera captures video continuously. The frames-per-second rate matters because facial recognition works better with multiple angles and expressions. Modern AI models trained on millions of faces can recognize people accurately from various angles, lighting conditions, and even with partial occlusions like glasses or hats.

Next comes feature extraction. The AI model scans each face in the camera's view and identifies key points: the distance between eyes, the shape of the jawline, the position of the nose, the height of the cheekbones. These measurements are converted into a numerical vector—think of it as a mathematical fingerprint of a face. This process is called creating an embedding, and it's what allows the system to compare faces without storing actual images.

Here's the critical part: this embedding is then compared against a database of known faces. Meta has billions of faces in its systems—scraped from Facebook, Instagram, and other sources. The algorithm searches for the closest match in that database. When a match is found with sufficient confidence, the system retrieves the associated profile information.

The confidence threshold is important. Set it too high, and the system misses faces it should recognize. Set it too low, and you get false positives—someone who looks similar to your friend gets identified as them. Meta would need to find the right balance, which is an ongoing machine learning problem.

Once a face is matched, the glasses can instantly pull information from that person's public profile. If they have location data shared, you might see where they live or work. If they've posted their job title and company, that appears. If they have recent Instagram stories, those could be displayed. The glasses become a window into someone's publicly shared (or semi-publicly shared) information, but with instant, automatic, context-aware retrieval.

The processing speed matters enormously. If facial recognition takes 5 seconds, the feature is useless. By the time the glasses identify someone, the interaction is already over. Modern on-device AI can process this in milliseconds now. The bottleneck isn't recognition anymore—it's the latency of pulling profile data from Meta's servers.

Meta's advantage here is scale. The company has invested billions into AI infrastructure, trained models on unprecedented amounts of facial data, and built systems that can match faces at massive scale. Smaller competitors simply don't have the technological capacity to do what Meta can do. This is partly why Meta believes facial recognition would give it a competitive edge against companies like Open AI, which is rumored to be working on smart glasses of its own.

Meta initially abandoned facial recognition in 2021 due to privacy concerns but reintroduced it in 2023 with a focus on security and fraud prevention. Estimated data.

Privacy Concerns: The Real Issues

Let's talk about why people are genuinely alarmed by this. Facial recognition in smart glasses creates a unique privacy problem that's different from anything we've dealt with before. This isn't about a company storing your data—it's about enabling real-time identification and tracking in physical space.

The fundamental concern is consent. When someone wears Ray-Ban smart glasses with facial recognition enabled, they're taking on the power to identify anyone they look at without that person's knowledge or permission. The person being identified has no idea they're being scanned. They can't opt out. They can't even know it happened. This is qualitatively different from posting a photo to Instagram where you understand you're sharing that image publicly.

Consider a practical scenario: a law enforcement officer wearing these glasses could identify protest participants in real-time, documenting who showed up and potentially using that information for harassment or targeting. An abusive partner could use them to track an ex-partner in public spaces. Retailers could use them to identify people with negative purchase histories and deny them service. Employers could monitor employees' whereabouts and social connections in ways that feel totalitarian.

Meta claims the feature won't enable true universal recognition—it will only identify people you're already connected to or who have public accounts. But that distinction barely holds water. On platforms like Facebook and Instagram, the definition of "public" is fluid. Information you think is private often leaks or becomes accessible through data brokers. People frequently don't understand their own privacy settings. What Meta considers "public" and what people think they've actually shared publicly are often wildly different.

There's also the problem of scope creep. Meta promises limited facial recognition today. But what about tomorrow? The feature could gradually expand. What starts as identifying friends could become identifying everyone in your network. What begins as accessing public profiles could expand to accessing semi-private information. Companies rarely restrict their own technological capabilities once they've built them.

Regulatory frameworks haven't caught up to this technology. The European Union has strict regulations on facial recognition in public spaces, but the US does not. Meta's internal memo, reported by the New York Times, explicitly states that the company plans to launch this feature during a "dynamic political environment" where civil society groups would be distracted by other concerns. That's not a coincidence—it's a strategic calculation that this is the best time to release something controversial.

There's also the infrastructure problem. Meta's glasses are connected devices, always communicating with the cloud. That creates a permanent record of who you've looked at, where you were, and when. This log exists in Meta's systems indefinitely. Even if the company promises not to use it for certain purposes today, that data is available for future use, government requests, or potential breaches.

Meta's argument about on-device processing is misleading. Yes, the facial recognition happens locally on the glasses. But that's the easiest part of the privacy problem. The hard part—identifying you from your face and pulling your personal information—requires sending data to Meta's servers. The company knows you looked at specific people in specific places at specific times. That's the real surveillance concern.

What Meta Is Saying: The Company's Justification

Meta hasn't publicly detailed its Name Tag feature, but internal documents and statements from company officials provide insight into the company's thinking. The core argument is that this is a natural extension of smart glasses functionality. Glasses have cameras. Cameras can be used for recognition. Modern AI makes this practical. Therefore, Meta should build it.

The company's secondary argument is competitive necessity. Smart glasses are going to be a major computing platform. If Meta doesn't add facial recognition capabilities, competitors will. Apple, Google, Open AI, and others are all developing AR glasses or smart eyewear. Meta needs differentiated features to win in that market. Facial recognition is a powerful differentiator.

Regarding privacy, Meta points to its technical choices. The company claims facial recognition runs on-device, meaning your actual face images don't get sent to Meta's servers. That's presented as a privacy feature. The company also argues that it's limiting the feature to people you're already connected to, not enabling universal identification of strangers.

Meta also highlights the security applications. Facial recognition can help authenticate users, prevent fraud, and protect against scams. If people are going to use this technology anyway (and they will), Meta argues it should build it responsibly with privacy controls, rather than leaving it to less thoughtful actors.

The company's internal memo revealed something particularly telling: Meta explicitly decided to launch during a period of political distraction when advocacy groups would be focused elsewhere. This wasn't presented as an accident or a convenient timing coincidence—it was strategy. The company recognized that the public backlash would be significant if people were paying attention, so it decided to time the launch accordingly.

That's honest in a way that's also deeply cynical. Meta isn't arguing that people shouldn't be concerned about facial recognition. It's just betting that people won't be paying enough attention to mount an effective opposition.

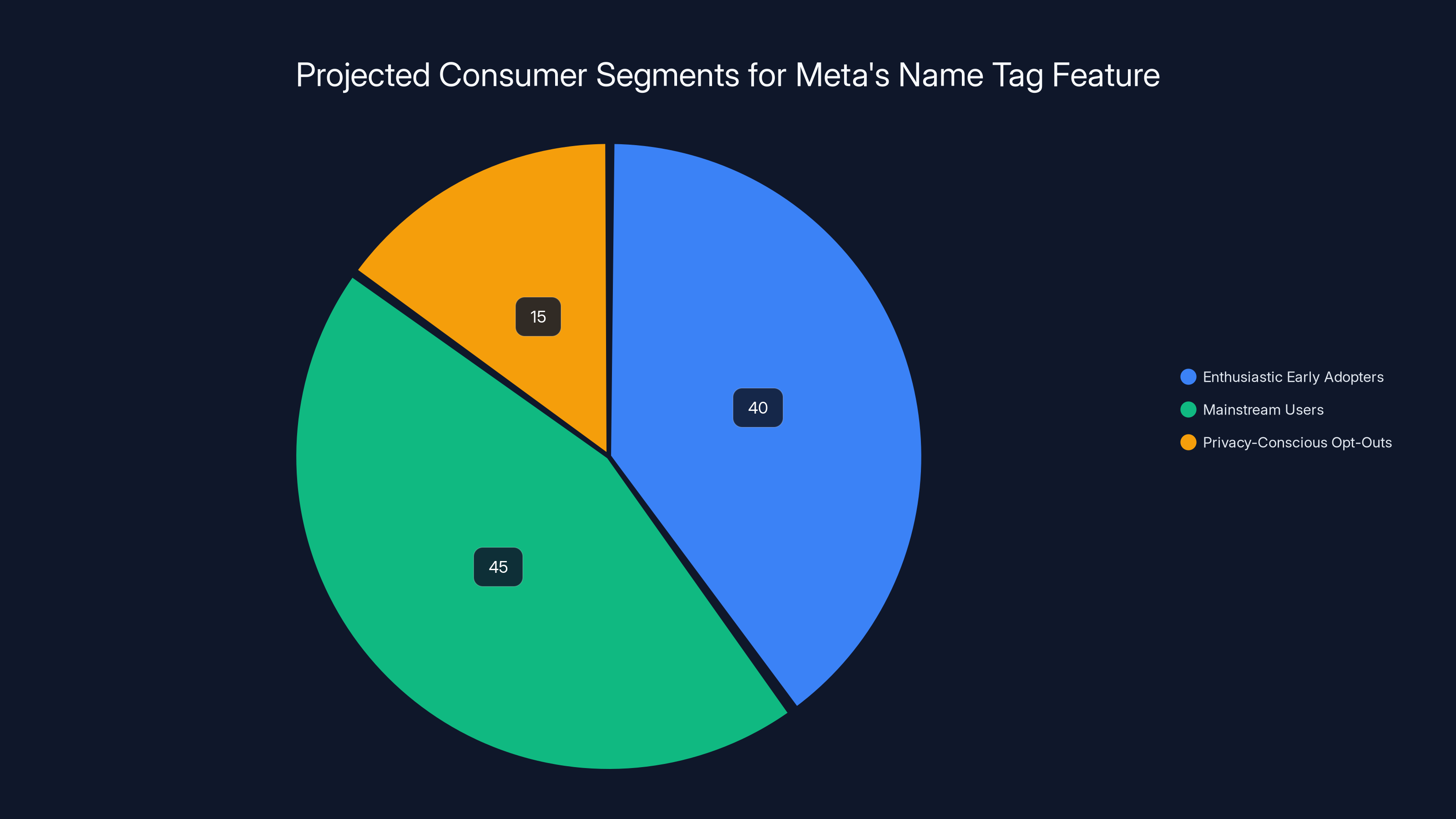

Estimated data suggests that early adopters and mainstream users will make up the majority of Meta's Name Tag feature users, despite privacy concerns.

The Competitive Landscape: Why Now?

Meta isn't alone in exploring smart glasses and facial recognition. The broader technology industry is moving toward AR and smart eyewear as the next major computing platform. Meta's move needs to be understood in this competitive context.

Apple has been rumored to be working on AR glasses for years. The company has acquired multiple AR companies, filed patents on relevant technology, and made strategic hires in the AR space. Apple's approach tends toward privacy, but the company hasn't ruled out facial recognition features if they believe they can be implemented responsibly. The potential market for AR glasses is enormous, and Apple doesn't like missing big platforms.

Google has a longer history with smart glasses through Google Glass, which was a commercial failure that created privacy backlash. The company learned that lesson and has been more cautious, but it's still investing in AR technology. Google has the advantage of already operating powerful facial recognition systems through its various products and services.

Open AI is developing Humanoid AI and has partnerships with hardware companies. While Open AI hasn't explicitly stated it's building smart glasses, the company's trajectory suggests it will eventually compete in that space. Open AI's glasses would likely emphasize real-time AI assistance and information retrieval—and facial recognition would be valuable for those use cases.

Microsoft has Holo Lens, primarily positioned for enterprise and industrial use cases, not consumer applications. But the company has been investing heavily in AI, particularly through its partnership with Open AI. AR glasses from Microsoft would likely blend Holo Lens technology with consumer-friendly design.

Samsung produces displays and has made prototype AR glasses. Meta's Ray-Ban partnership gives Meta an advantage in consumer distribution—Ray-Ban is a recognizable brand that people actually want to wear, unlike Google Glass which looked like a spy gadget.

In this landscape, facial recognition becomes a key differentiator. It's a feature that legitimately adds value (instant contact information, real-time context about people you're meeting), and it's a capability that Meta can implement at scale because of its existing AI infrastructure and massive user database.

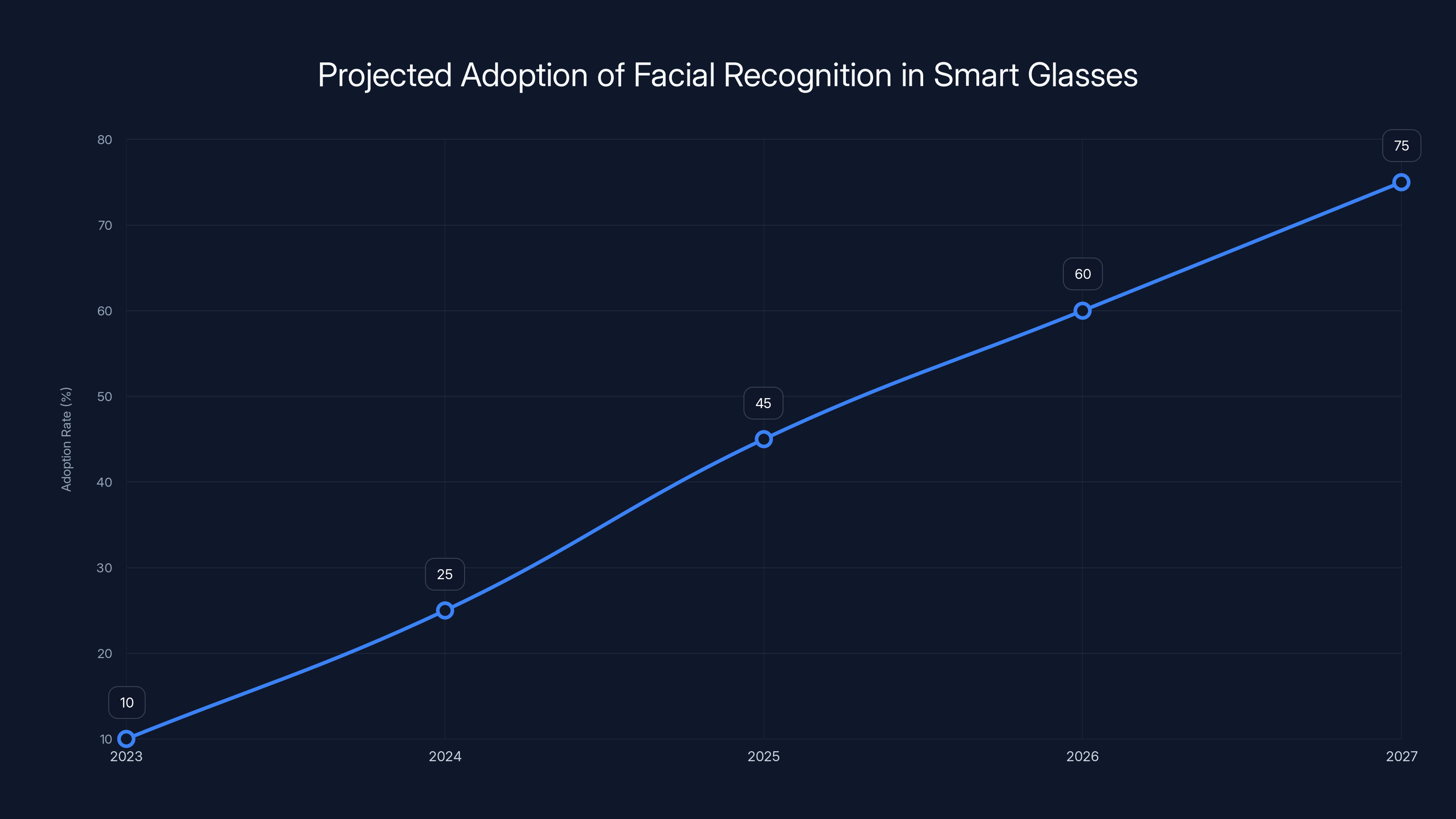

The smart glasses market is still small, but analysts expect explosive growth. IDC estimates that the market for AR glasses specifically will grow from approximately 2 million units in 2024 to over 100 million units by 2028. That's a 50x increase in less than four years. The company that wins in smart glasses during that growth period will establish itself as the platform leader and will be extremely difficult to displace.

Meta is making a bet that it would rather own the smart glasses market with facial recognition than lose market share to competitors and lose the entire platform. That's a calculation about the future of computing, not just about privacy.

Timeline and Launch Strategy

According to reports, Meta is planning to launch the Name Tag feature sometime in 2025. This isn't confirmed by Meta officially, but the internal documents reviewed by journalists suggest the company is serious about this timeline. The company is explicitly planning the launch during a period it believes will be favorable—a time when public attention is elsewhere and opposition groups are stretched thin.

The phased approach matters. Meta isn't going to activate facial recognition for all Ray-Ban smart glasses users on day one. The company will likely start with a limited beta or opt-in feature. Early adopters and power users will get access first. As the feature matures and potential privacy issues are addressed, it will expand to more users.

This staged approach accomplishes multiple things. First, it allows Meta to gather real-world data about how the feature actually performs. Facial recognition works differently in the wild than in laboratories. Different lighting, different face angles, different use cases—all of these will affect accuracy. Early data will help Meta refine the system.

Second, it buys Meta time on the regulatory front. By the time regulators start taking action, the feature will already be embedded in user behavior and expectations. People will have adapted their usage patterns. It's much harder to pull back something that's already deployed than to prevent it from being deployed in the first place.

Third, it allows Meta to monitor public reaction and adjust messaging accordingly. If there's a massive backlash, Meta can pause the expansion, tweak the privacy controls, and reframe the feature as less invasive than it actually is.

The 2025 timeline is aggressive but realistic. Meta has the technical capability to build this. The company's AI team is world-class. The infrastructure exists. The only real obstacles are regulatory and reputational, and Meta seems willing to accept those risks.

Estimated data suggests a significant increase in the adoption of facial recognition in smart glasses, driven by Meta's strategy. Regulatory actions could alter this trajectory.

Technical Limitations and Failures

Here's something important that often gets overlooked: facial recognition isn't perfect, and it will fail in ways that create real problems.

Facial recognition accuracy depends heavily on the training data. If the models are trained primarily on faces of one ethnicity, they perform much worse on other ethnicities. This is a well-documented problem in computer vision called demographic bias. Meta has billions of faces in its training data, but those faces aren't evenly distributed. Western, particularly American, faces are overrepresented. Faces of people from certain regions and ethnic backgrounds are underrepresented.

The practical consequence: if you're South Asian, East Asian, or from many African countries, Meta's facial recognition system will be more likely to misidentify you. It might confuse you with someone else entirely. In the context of smart glasses that pull up personal information about someone, this is a serious problem. Getting someone's identity wrong means the wrong information is displayed—potentially embarrassing or harmful information about someone else.

There's also the problem of identical twins or very similar-looking people. Facial recognition struggles with these cases. You look at your twin brother, the glasses identify your twin sister instead. That's a failure mode that happens regularly in real-world use of facial recognition systems.

Age is another factor. Facial recognition accuracy drops significantly for young children and elderly people. The algorithms have more trouble with faces that are very different from the average face in the training data.

Lighting conditions matter enormously. Facial recognition works better in bright, well-lit environments and worse in dim lighting, backlighting, or unusual shadow conditions. If you're looking at someone in a bar or at night, the system's accuracy will drop significantly.

Partial occlusions—glasses, hats, facial hair, makeup, masks—all reduce accuracy. Someone who has grown a beard since their last profile photo might not be recognized. Someone wearing sunglasses (ironic, given these are glasses themselves) will be harder to identify.

Meta will deal with these limitations by requiring a certain confidence threshold before displaying information. If the system isn't confident enough that it's identified someone correctly, it won't show information. But this creates a different problem: the feature becomes less useful when it's less certain. And there's a question of whether Meta sets the threshold appropriately, or whether it lowers it to make the feature more broadly useful, accepting higher error rates.

Another limitation is the database problem. Meta can only identify people who are in its facial database. For people who don't use Facebook or Instagram, or who have never uploaded a profile photo, the system won't recognize them. This actually creates an interesting discriminatory effect: people who are online and active on Meta's platforms are more identifiable than people who avoid those platforms.

Regulatory Landscape and Legal Challenges

Meta doesn't operate in a regulatory vacuum, though sometimes it acts like it does. Different regions have different rules about facial recognition, and Meta will need to navigate those differences carefully.

The European Union is the most restrictive. The EU's AI Act, which is coming into effect gradually, classifies real-time facial recognition for identification in public spaces as a prohibited high-risk use. Some exceptions exist for law enforcement and national security, but commercial use is basically off the table. If Meta tries to launch facial recognition in smart glasses in the EU, it will immediately violate the law.

This means Meta will need to geofence the feature. It will work in the US, parts of Asia, and other regions, but it won't work in the EU. This creates a strange technical problem: the same glasses will behave differently depending on where you are. This has precedent (tech companies already do this), but it's cumbersome and creates enforcement challenges.

The United Kingdom, post-Brexit, has more flexibility than the EU. The UK has been hesitant about facial recognition but hasn't banned it outright. Meta will likely lobby the UK government to allow the feature, positioning it as a competitive necessity and employment advantage if the UK wants to keep tech companies operating there.

Canada, Australia, and other developed democracies are developing their own frameworks. Most are moving toward stricter regulation of facial recognition, but none have outright bans like the EU. Meta will work with these governments to find regulatory approaches that allow the company to operate.

The US is the least restrictive major market. There's no comprehensive federal law against facial recognition. Some state laws provide restrictions, and cities like San Francisco have banned government use of facial recognition, but there's nothing stopping Meta from deploying this feature. This is why Meta is focusing on the US market first.

There's also the question of biometric privacy laws. Different states have different standards. Illinois has BIPA (Biometric Information Privacy Act), one of the strictest. California has its own privacy regulations. Meta will need to comply with these state laws in addition to federal rules.

The FTC (Federal Trade Commission) has also expressed interest in facial recognition practices. The FTC has previously fined Meta for privacy violations and has shown willingness to regulate the company. The company needs to anticipate that the FTC might take action against Name Tag if it determines that Meta is engaging in unfair or deceptive practices.

International pressure is another factor. Privacy advocates, civil society organizations, and even some governments have called for restrictions on facial recognition in wearables. If Meta launches Name Tag and faces significant international criticism, that could create enough pressure for faster regulatory action.

The legal challenges will be substantial, and they'll likely take years to fully resolve. But that's partly why Meta is launching now—the company would rather deal with legal action after the feature is deployed than never deploy it at all.

Estimated data shows that consent issues are the most severe privacy concern related to facial recognition in smart glasses, followed by real-time tracking and data misuse.

Real-World Use Cases and Applications

Beyond the privacy concerns, facial recognition in smart glasses actually does have legitimate use cases. Understanding these makes it harder to simply dismiss the technology as purely dystopian.

For people with visual impairment, facial recognition could be genuinely helpful. Smart glasses that could identify people and provide audio descriptions would create significant accessibility improvements. Imagine someone with low vision attending a party, and their glasses could tell them who they're talking to and provide context about that person. This is an actual accessibility win.

Professional networking is another legitimate use case. Imagine you're at a conference wearing smart glasses with facial recognition. You walk past someone in the hallway, and your glasses tell you that you have 12 mutual connections and that this person wrote a paper you cited in your own research. That's useful information that could facilitate networking and collaboration.

For people with prosopagnosia (face blindness), a condition that prevents the brain from recognizing faces, smart glasses with facial recognition would be life-changing. People with this condition have real difficulty navigating social situations. Being able to identify people automatically would genuinely improve their quality of life.

In professional contexts, facial recognition could speed up authentication and security. Instead of typing a password or scanning a badge, you could be recognized by your glasses. This makes security faster and easier.

Meta could position this feature as helpful for memory. If you want to remember someone you met at an event, your glasses could automatically save that interaction. Later, you could search for "people I met at Tech Conf 2025" and see a list with photos and context. That's genuinely useful for people with poor memory or for people who meet many new people professionally.

The problem is that these legitimate use cases don't require Meta to build a system that identifies random people on the street. Meta could implement facial recognition in a way that's much more limited and privacy-respecting. The company could require active consent before using it on someone. The company could limit it to specific contexts. The company could build in privacy controls that actually work.

But Meta isn't doing that. Instead, the company is building the most powerful, least privacy-respecting version possible, then arguing that the technology itself is good and people just need to trust Meta's restraint.

Comparative Privacy Approaches

How Meta's approach to facial recognition compares to how other companies handle similar technology is instructive.

Apple has been vocal about privacy as a competitive advantage. The company has refused to implement features that would require extensive data collection, and it's positioned end-to-end encryption and on-device processing as core to its brand. If Apple implements facial recognition in smart glasses, the company would likely do so with much stronger privacy controls than Meta is offering. Apple would probably require explicit user consent before the glasses identify anyone, and it might not enable universal identification at all.

Google's approach is somewhere in the middle. Google collects enormous amounts of data and uses it for advertising and personalization, but the company has also shown some concern for privacy regulation. Google would likely implement facial recognition with granular privacy controls, allowing users to opt in or out on a case-by-case basis.

Open AI hasn't deployed consumer products at scale yet, so it's unclear how the company would handle facial recognition. But Open AI's positioning as a responsible AI company suggests it would be cautious about deploying surveillance-scale facial recognition.

Duck Duck Go and privacy-focused companies would almost certainly refuse to implement facial recognition at all, or would do so only in the most limited contexts with explicit consent.

Meta's approach is the most permissive and least privacy-respecting among major technology companies. That's partly because facial recognition serves Meta's business model well. The company makes money from advertising, and facial recognition generates data that Meta can use to understand and target users. Meta has financial incentive to make facial recognition powerful and pervasive.

This is the core problem: Meta's business model incentivizes the most surveillance-intensive version of facial recognition, not the version that's best for users.

The Political Context and Timing

One of the most revealing aspects of Meta's plan is the explicit attention to political timing. The company's internal memo stated that the US political environment presents an opportunity because civil society groups will be focused on other concerns.

This is strategy, not accident. Meta made a deliberate calculation that launching during a period of political distraction would reduce organized opposition. If the company launched during a period of high civic engagement on tech policy, the backlash would be much more effective. Privacy advocates have real power when the public is paying attention, but much less power when everyone is focused elsewhere.

This reveals something cynical about how Meta thinks about regulation and public opinion. The company doesn't believe its arguments are so compelling that they'll win in a fair fight with privacy advocates. Instead, the company believes it needs to launch while it can avoid the fight entirely.

The political context also matters for regulation. In a period of political instability and government dysfunction, regulatory agencies are less likely to move quickly against new technologies. If Congress is split and divided, it's harder to pass new technology regulation. If the executive branch is preoccupied with other issues, enforcement of existing rules is less likely.

Meta is essentially betting that the institutional capacity to regulate tech is so diminished right now that the company can deploy first and ask for forgiveness later. That's a plausible bet, given recent trends in US politics and regulation.

Consumer Adoption and Market Response

The success of Meta's Name Tag feature will ultimately depend on consumer adoption. Even if the feature launches, people need to actually use it. Privacy concerns aside, people might simply not want facial recognition in their glasses.

Ray-Ban smart glasses have a loyal user base already. These are people interested in AR, AI, and wearable technology. They're generally more tolerant of privacy tradeoffs than the average person, and they're often early adopters of new technology features. Meta's target market for Name Tag is probably these enthusiasts, not the general population.

Data from Facebook and Instagram suggests that when Meta launches privacy-invasive features, many people keep using the platforms anyway. The company's tracking pixel is everywhere despite privacy concerns. People use Instagram despite concerns about how the company collects their data. This suggests that Meta's cynical understanding of consumer behavior might be correct: people express privacy concerns, but they often accept privacy-invasive features if they perceive value.

On the flip side, there's a segment of people who value privacy enough to opt out of Meta's ecosystem. These people will either not use Ray-Ban glasses, or they'll disable the facial recognition feature completely. But that segment is smaller than the mainstream market.

Media coverage will matter. If the tech media treats facial recognition in smart glasses as a dystopian development (which many outlets will), that creates a cultural narrative that could limit adoption. People are influenced by what they read and watch about technology. Negative coverage could suppress demand.

Government action matters too. If regulators move to restrict or ban the feature, that could prevent Meta from fully rolling it out. But regulatory action takes time, and Meta is banking on being able to deploy before regulators can effectively stop it.

Alternative Futures and Scenarios

What happens next depends on choices by Meta, regulators, and consumers. Several scenarios are plausible.

The most likely scenario is that Meta launches the feature with significant privacy controls, faces criticism from advocacy groups and some media outlets, but successfully deploys it in the US market. Users who care about privacy will opt out. Users who don't care will use it. Over time, facial recognition becomes normalized in smart glasses. Competitors follow, and within five years, facial recognition is a standard feature in smart eyewear.

A second scenario involves significant regulatory pushback. The FTC could sue Meta over Name Tag, arguing that the feature constitutes unfair or deceptive practices. Congress could pass legislation restricting facial recognition. This would force Meta to disable the feature or heavily constrain it. This scenario is less likely than the first one, given current regulatory capacity, but it's possible.

A third scenario involves a privacy-focused competitor winning the smart glasses market. If Apple or another company launches smart glasses with much stronger privacy controls and refuses to implement facial recognition, consumers might prefer those glasses. This would put pressure on Meta to limit facial recognition or lose market share. This scenario is possible but requires that privacy-conscious consumers have enough market power to affect outcomes.

A fourth scenario involves a backlash narrative that spreads widely enough to constrain adoption. If the media covers facial recognition in smart glasses as a major surveillance threat, and if advocacy groups mobilize effectively, public pressure could prevent Meta from launching successfully. This is the scenario that Meta's timing calculation is designed to avoid.

Most likely, some combination of these occurs. Regulation happens, but it's slow and partial. Some consumers adopt the feature, others opt out. Media coverage is mixed. Within a few years, we reach a new equilibrium where facial recognition is possible in smart glasses but constrained by regulation and consumer preference in some markets.

The Bigger Picture: Where This Fits in Tech

Facial recognition in smart glasses isn't an isolated development. It's part of a broader trend toward ambient AI and pervasive computing that's reshaping how technology works.

For decades, computing was something you actively engaged with. You sat at a computer, opened an app, and used it. Then mobile changed that—you carried a computer with you. The phone became a persistent presence in your life. Apps notified you. The phone tracked your location. But the interaction was still relatively active. You chose to use it.

Ambient AI is different. It means AI integrated into the environment and into things you wear. Your glasses don't require active engagement. They're just there, constantly perceiving and understanding the world around you. You don't activate facial recognition, the glasses do that automatically and constantly.

This is a shift from computing as a tool you choose to use to computing as an environment you inhabit. And facial recognition is a crucial capability for making that work. Without facial recognition, smart glasses are just cameras recording the world. With facial recognition, they're intelligently understanding the world and pulling in contextual information.

Meta isn't alone in building toward this future. Every major tech company is moving in this direction. Google is building ambient AI into its services. Apple is integrating AI into devices. Amazon is putting cameras everywhere. Microsoft is thinking about AI-powered physical spaces.

Facial recognition is a lynchpin technology in this transition. It's what allows ambient AI to move from being a neat feature to being actually useful at scale.

The question isn't whether facial recognition will exist in smart glasses. It will. The question is what constraints and controls will exist around it. Will it be opt-in or opt-out? Will it require consent? Will there be regulatory limits on what information can be displayed? Will there be logging and transparency requirements?

Meta's strategy is to deploy first, hope to normalize the technology, and then deal with regulation later. If that works, Meta establishes the default behavior for the technology. Once people are used to facial recognition in glasses, it's much harder to restrict it later.

This is why the next 12 to 18 months are critical. The decisions Meta makes now will shape what's possible with smart glasses for years to come.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you're a consumer, you have agency here. First, understand the privacy implications of smart glasses before you buy them. Ask explicitly whether any glasses you're considering have facial recognition capabilities, and how those capabilities are implemented. Don't assume privacy is protected just because a company claims to do processing on-device.

If you value privacy, consider waiting to see how regulation develops before adopting smart glasses. The first generation will almost certainly have the fewest privacy protections. As regulation tightens, later generations will include stronger controls.

Educate yourself about facial recognition. Understand how it works, what it can and can't do, and what the legitimate privacy concerns are. This knowledge gives you better judgment about when to accept the technology and when to reject it.

Vocalize your preferences to companies and regulators. If you're opposed to facial recognition in smart glasses, say so. Contact your representative. Support organizations working on privacy. Companies and regulators respond to pressure.

If you're building technology, consider building privacy controls into facial recognition rather than hoping they'll be added later. Companies that win long-term will be those that respect user preferences, not those that push the hardest on surveillance.

FAQ

What exactly is facial recognition technology?

Facial recognition is an AI technology that identifies people by analyzing their faces. The system captures an image of a face, extracts key features (distance between eyes, shape of jawline, etc.), converts those features into mathematical data called embeddings, and compares the result against a database of known faces to find a match. It's the same technology used for security authentication on phones, but Meta's version in smart glasses would use it to identify people in the real world.

How would Meta's Name Tag feature work in Ray-Ban glasses?

When you're wearing Ray-Ban smart glasses with Name Tag enabled, the glasses constantly capture video of what you're looking at. When you look at a specific person, the on-device AI processes their face, creates an embedding, and searches Meta's database for a match. If the person is in your social network or has a public Instagram account, their profile information displays on your glasses' screen. The entire recognition process happens in milliseconds. The feature requires internet connectivity to pull profile information from Meta's servers.

Why is facial recognition in smart glasses controversial?

Facial recognition in wearables raises unique privacy concerns because it enables identification without consent. When someone wears smart glasses with this capability, they can identify anyone they look at without those people knowing they're being scanned. This creates potential for surveillance, harassment, and tracking. People might be identified in public without their knowledge, and that information could be used in ways they never consented to. Additionally, the technology has accuracy problems, particularly for certain ethnic groups, which could lead to false identifications.

Would facial recognition only work on people you already know?

According to Meta's statements, the initial version would only identify people you're already connected to on Meta's platforms or those with public Instagram profiles. However, this distinction doesn't provide strong privacy protection. Millions of people have Facebook or Instagram accounts, many with more information public than they realize. Additionally, once the technical infrastructure is built, expanding it to identify anyone is relatively simple, making this a potential privacy slippery slope.

When will Meta launch facial recognition in smart glasses?

Internal documents suggest Meta plans to launch the Name Tag feature sometime in 2025, potentially starting with a limited beta for early adopters and power users. The exact launch date hasn't been officially announced by Meta. The company is reportedly timing the launch during a period of political distraction to minimize organized opposition from privacy advocates and advocacy groups.

Is facial recognition legal in smart glasses?

Legality varies dramatically by region. The European Union's AI Act classifies real-time facial recognition for identification in public spaces as prohibited high-risk use, making it illegal for commercial applications. The United States has no comprehensive federal ban, though some states have their own regulations. Meta will likely need to geofence the feature, allowing it in the US and some other markets while disabling it in the EU and other restricted regions. Regulation is still evolving as governments develop frameworks for wearable facial recognition.

How accurate is facial recognition, and what could go wrong?

Facial recognition accuracy varies significantly based on lighting, angles, facial hair, glasses, and other factors. Studies have shown demographic bias, with the technology performing worse on darker-skinned individuals and people from certain ethnic backgrounds. Young children and elderly people also see reduced accuracy. In smart glasses, this means potential for false identifications, where the glasses might identify you as someone else entirely, displaying the wrong person's information. This is a serious problem when that person's private information is at stake.

What happens to the facial data and identification logs?

While Meta claims facial recognition processing happens on the device, the identification results and profile lookups must go to Meta's servers. This creates a permanent record of who you've looked at, where, and when. That log exists indefinitely in Meta's systems and could be accessed by government requests, sold to data brokers, or used for purposes users didn't consent to. On-device processing doesn't solve the fundamental privacy problem of Meta knowing your social interactions in real-time.

Can you opt out of being identified by smart glasses?

Currently, there's no mechanism for people to opt out of being identified by others' smart glasses. If someone else is wearing Ray-Ban glasses with facial recognition and looks at you, you won't know you've been scanned. You can't prevent your face from being recognized. This is different from most privacy settings, where you can control your own information. With facial recognition in smart glasses, you lose control over whether your face is scanned and matched against databases you may never agreed to.

What would stronger privacy protections look like?

Stronger privacy approaches could include requiring explicit consent before using facial recognition on someone (announced consent), limiting facial recognition to specific contexts rather than always-on, implementing transparency logs that show when you've been identified, restricting what information can be displayed after identification, or prohibiting certain uses like location tracking. The EU's approach is stronger—essentially banning facial recognition in public. A middle ground would allow the technology with significant constraints and oversight. Currently, Meta's approach has minimal privacy constraints.

What can I do about facial recognition in smart glasses?

Consumers can educate themselves about the technology and privacy implications, express concerns to elected representatives, support privacy advocacy organizations, and vote with their dollars by choosing products with stronger privacy protections. If you value privacy, you can avoid purchasing smart glasses until regulatory frameworks develop. Policymakers and companies respond to constituent pressure and market demand. Individual choices, aggregated across millions of people, do affect how companies develop and deploy technology.

The Road Ahead

Meta's push to bring facial recognition to smart glasses represents a critical moment in how technology develops. The company is making a calculated bet that it can deploy surveillance-scale facial recognition, normalize it through ubiquity, and then deal with regulation after the fact.

This is a specific choice Meta is making, not an inevitable result of technological progress. The company could build privacy-respecting smart glasses. It could require consent. It could limit facial recognition to specific use cases. But Meta isn't choosing those paths because the company benefits from surveillance-scale facial recognition. The data generated helps Meta's advertising business. The capability gives Meta competitive advantage. The normalization of facial recognition helps all of Meta's future plans for ambient AI.

The outcome of this situation depends on choices by regulators, consumers, and companies competing with Meta. If regulators act decisively, facial recognition in smart glasses could be constrained. If consumers demand privacy, companies will compete on that dimension. If competitors win the market by offering better privacy, Meta will lose market share.

But none of that is guaranteed. It's entirely possible that Meta's strategy works. Facial recognition becomes normalized. Surveillance in public space increases dramatically. Our baseline assumptions about privacy erode further. In five years, the idea that you could wear glasses without having your social network automatically scanned seems quaint.

The next year or two will be determinative. Meta is planning to launch right now, during this window. Privacy advocates and regulators have this moment to push back, to draw lines, to establish norms about what kinds of surveillance technology are acceptable in wearables.

After Meta launches, the battle becomes much harder. Technology deployed at scale is much harder to regulate or restrict. Users adapt. Competitors follow. What seemed outrageous becomes normal.

This is how surveillance infrastructure gets built in modern democracies: not through centralized, explicit decisions by governments, but through corporate choices enabled by public distraction and regulatory inaction. Meta isn't the villain here, exactly. The company is just being Meta: aggressive, willing to push boundaries, focused on competitive advantage and growth.

The question is whether the rest of us—regulators, advocates, competitors, consumers—will push back effectively before facial recognition in smart glasses becomes just another normal part of digital life.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's Name Tag feature would enable real-time facial recognition in Ray-Ban smart glasses, potentially launching in 2025

- The technology raises serious privacy concerns because it enables identification without consent, creating potential for surveillance and tracking

- Meta explicitly timed this launch for a period of political distraction when privacy advocates would be focused elsewhere

- The feature would initially only identify people in your social network or with public Instagram accounts, but the infrastructure enables universal recognition later

- Facial recognition accuracy problems, particularly demographic bias against darker-skinned individuals, create risk of false identifications

- Different regions have vastly different regulations: the EU prohibits it, the US has minimal restrictions, and other countries are developing frameworks

- Competitors like Apple, Google, and OpenAI are also developing smart glasses, making facial recognition a competitive differentiator

- Legitimate uses exist (accessibility, authentication, professional networking), but Meta's approach is the least privacy-respecting among major tech companies

- Smart glasses market is expected to explode from 2 million units in 2024 to 100+ million by 2028, making this platform crucial for Meta's future

Related Articles

- Ring Cancels Flock Safety Partnership Amid Surveillance Backlash [2025]

- AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance [2025]

- Facebook's Meta AI Profile Photo Animations: A Deep Dive [2025]

- Ring's Police Partnership & Super Bowl Controversy Explained [2025]

- QuitGPT Movement: ChatGPT Boycott, Politics & AI Alternatives [2025]

- Disney's Frozen Ever After: Animatronic Tech That 'Hopped Off Screen' [2025]

![Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-facial-recognition-smart-glasses-privacy-tech-and-wha/image-1-1770995421677.jpg)