The Death of Shallow Focus: How Panoptic Lens Technology Changes Everything

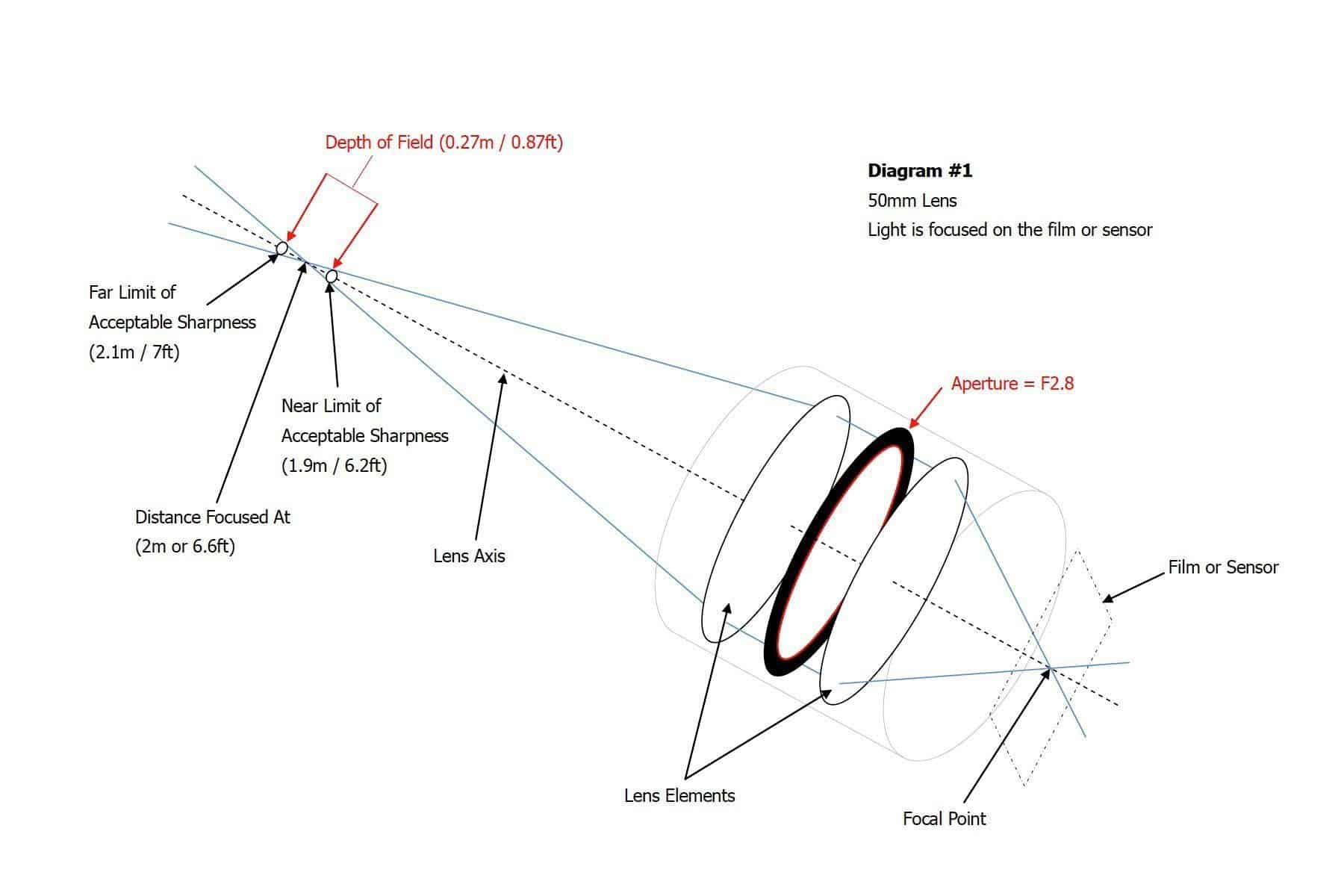

For over 150 years, photographers have lived with a frustrating limitation. Pick a subject to focus on, and everything else blurs. Move the focus point, and your original subject fuzzes out. This optical constraint isn't a bug—it's fundamental to how lenses work. Light converges through glass in ways that create a single focal plane, that sweet spot of sharpness.

But what if that limitation simply ceased to exist?

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have demonstrated something remarkable: a computational lens system that brings every part of a scene into sharp focus simultaneously. Not through combining multiple exposures in post-processing. Not through aggressive digital sharpening that destroys image quality. But through actual optical innovation that lets each pixel focus independently.

This isn't science fiction. It's not even purely theoretical anymore. The researchers have built working prototypes, captured real images, and published peer-reviewed research documenting the breakthrough. The implications ripple far beyond Instagram aesthetics. This technology could transform microscopy, enable true depth perception for virtual reality, give autonomous vehicles unprecedented clarity when navigating complex environments, and fundamentally reshape how computational photography evolves over the next decade.

Understanding this technology requires stepping back into optical physics, learning how computational methods can reshape traditional hardware constraints, and recognizing why this breakthrough matters for imaging technology as a whole. Let's start with the fundamental problem.

The Depth of Field Problem: Why Traditional Lenses Can't Focus Everything

When you look at the world, your eye actually does something remarkable. It's constantly adjusting focus, shifting between near and far objects, integrating all that information into a cohesive visual experience. But when you look at a photograph, you're seeing a single frozen moment captured through an optical system that can only be sharp at one distance.

This limitation comes from basic physics. A lens focuses light by bending it through curved glass. The farther the lens sits from the image sensor, the closer the subject you're focusing on. The closer the lens gets to the sensor, the farther away your subject must be to appear sharp. There's no way around this relationship—it's built into the mathematics of refraction.

Photographers have learned to work with this constraint creatively. Portrait photographers use wide apertures (like f/1.8) to create extremely shallow depth of field, isolating a subject from a blurred background. Landscape photographers stop down to narrow apertures (like f/16) to maximize the depth of field, getting as much of the scene sharp as possible. Wedding photographers position subjects carefully in the focal plane. Macro photographers use specialized equipment to deal with microscopically thin zones of focus.

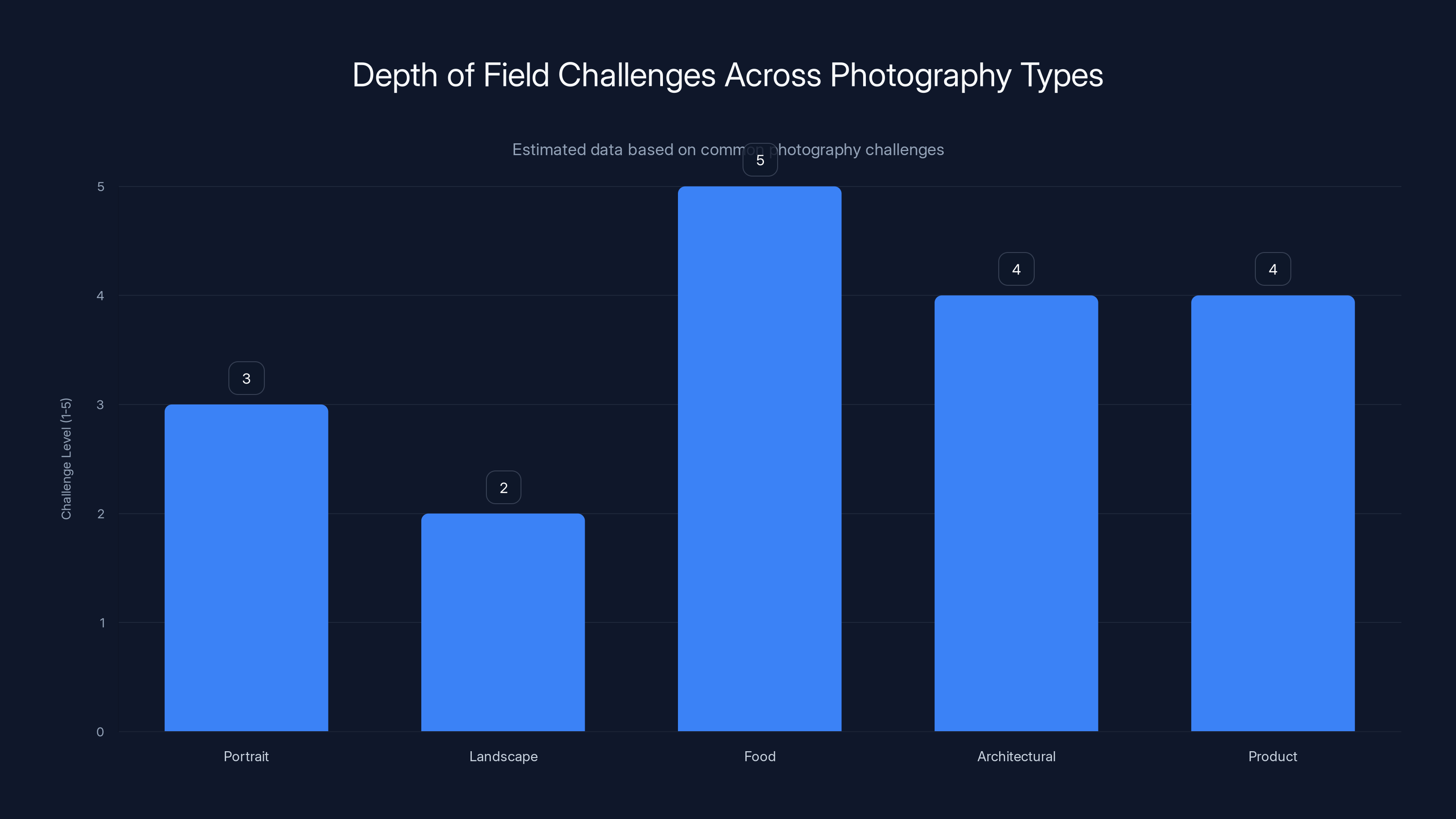

The depth of field problem becomes especially painful in specific scenarios. Food photography requires every detail of a dish to be crisp. Architectural photography struggles when you need both a sharp foreground element and a sharp background building. Product photography often needs the entire object in focus. Scientific imaging and medical research frequently require clear focus across varied depths. Autonomous vehicles need to track obstacles at many different distances simultaneously.

For decades, the workaround was simple: shoot multiple images at different focal distances, then use computational methods to merge them. Focus stacking, as it's called, involves taking five, ten, sometimes fifty overlapping shots and blending them together. This works reasonably well, but it requires static subjects and careful camera positioning. It's slow, it's complicated, and it introduces artifacts when subjects move between exposures.

The Carnegie Mellon breakthrough attacks this problem from a completely different angle. Instead of accepting the optical limitation and working around it computationally, what if you could change the optical hardware itself?

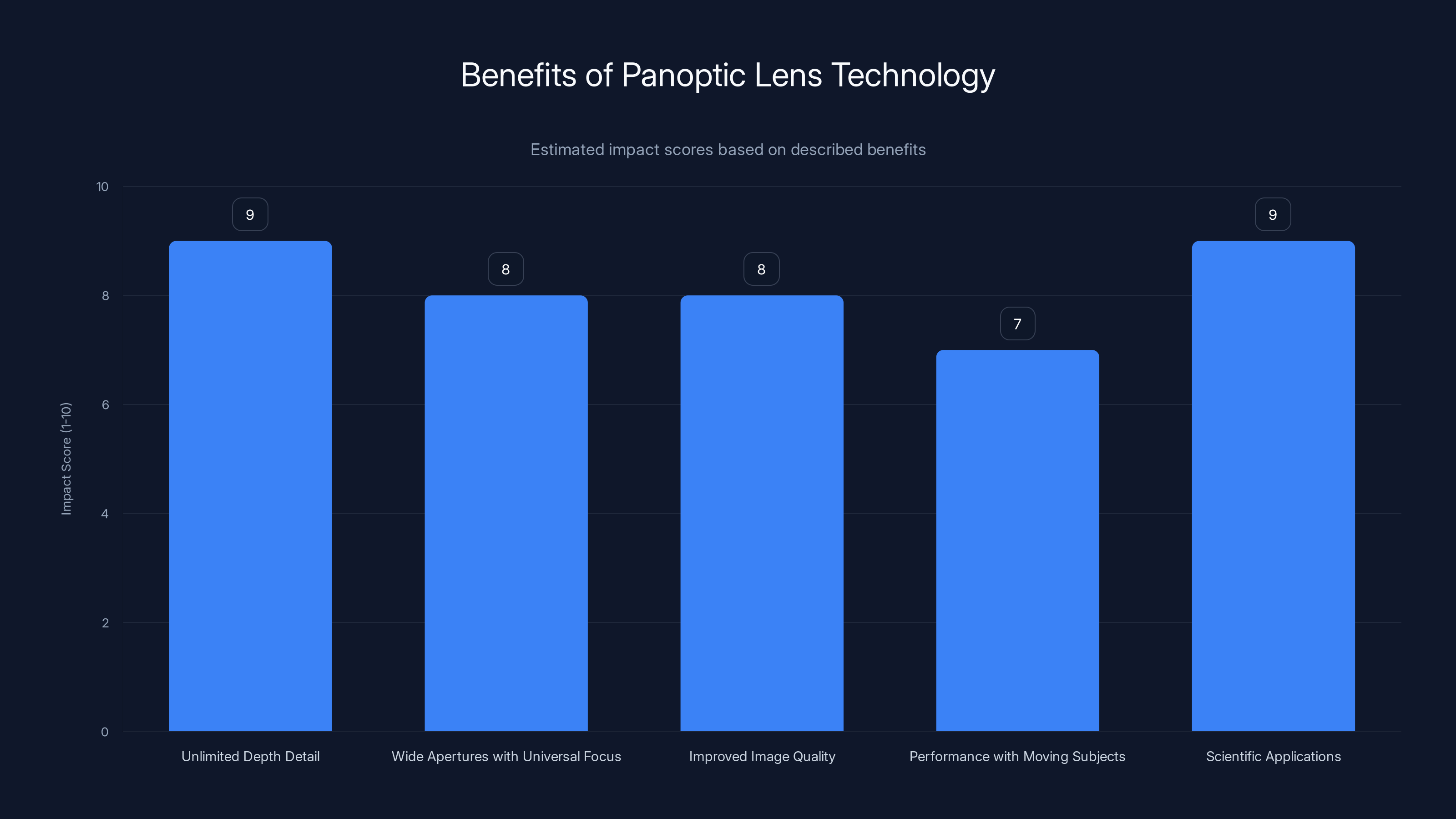

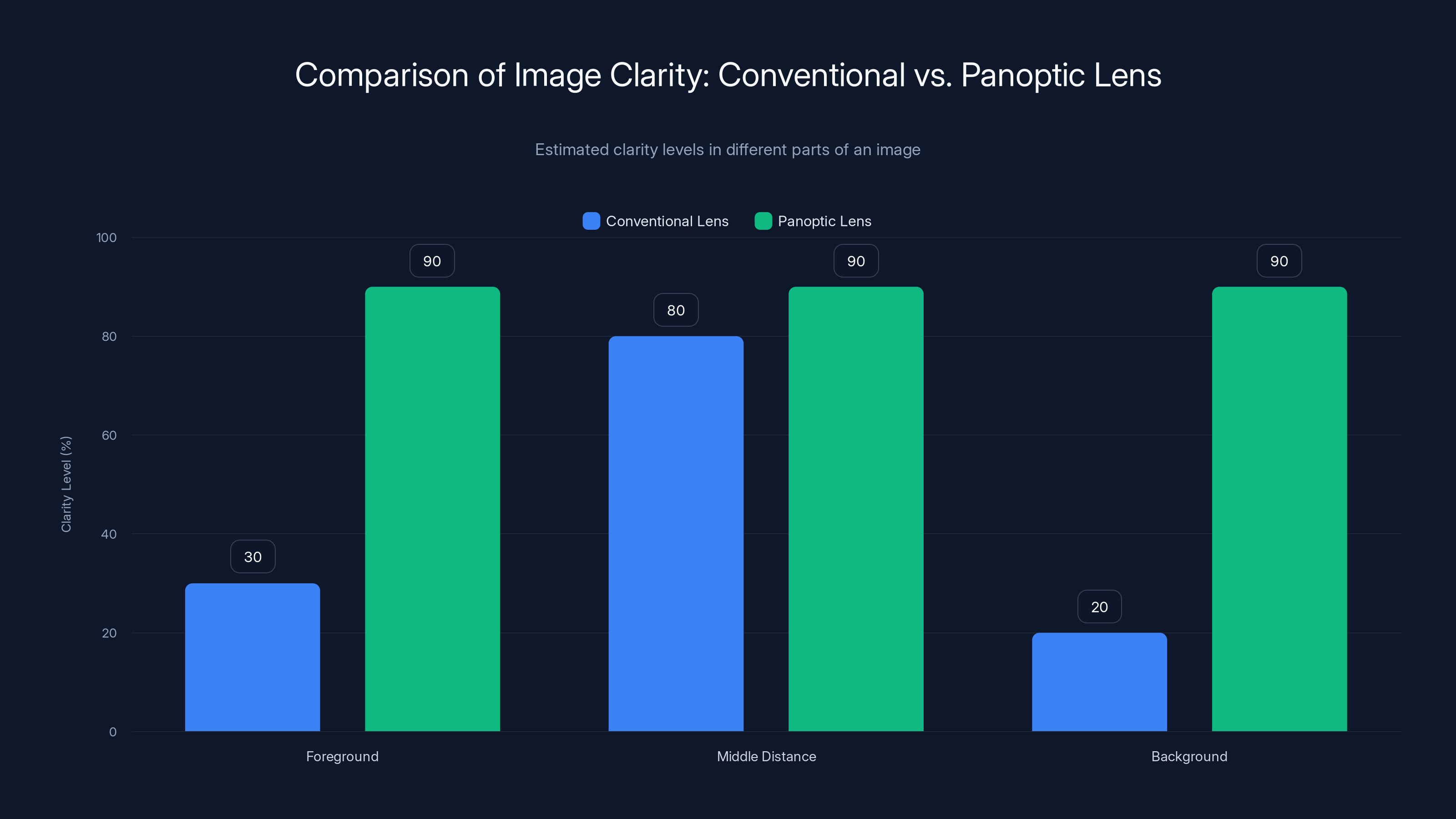

Panoptic lens technology offers significant benefits, particularly in capturing unlimited depth detail and enhancing scientific applications. (Estimated data)

The Computational Lens: Reimagining Optics Through Software and Hardware

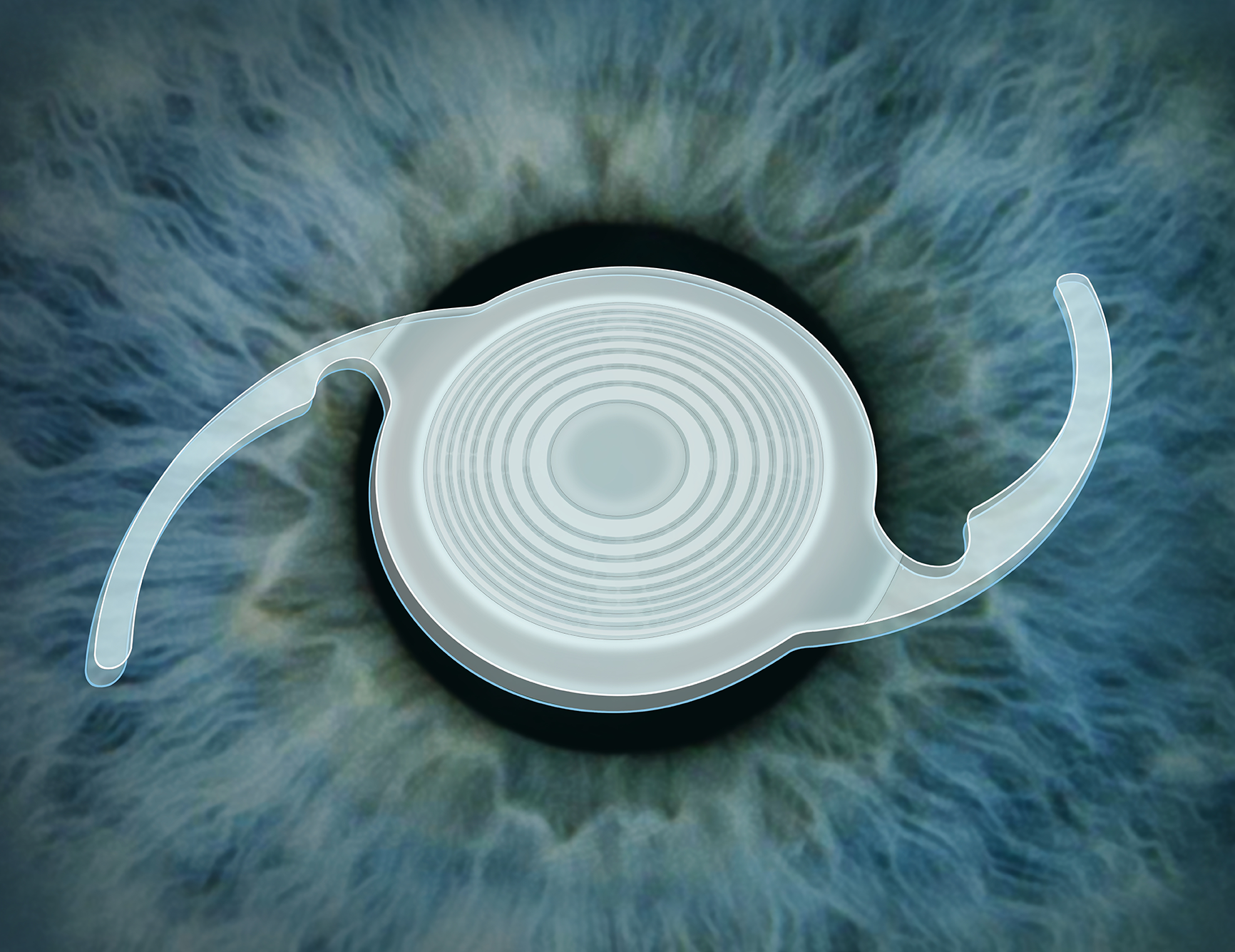

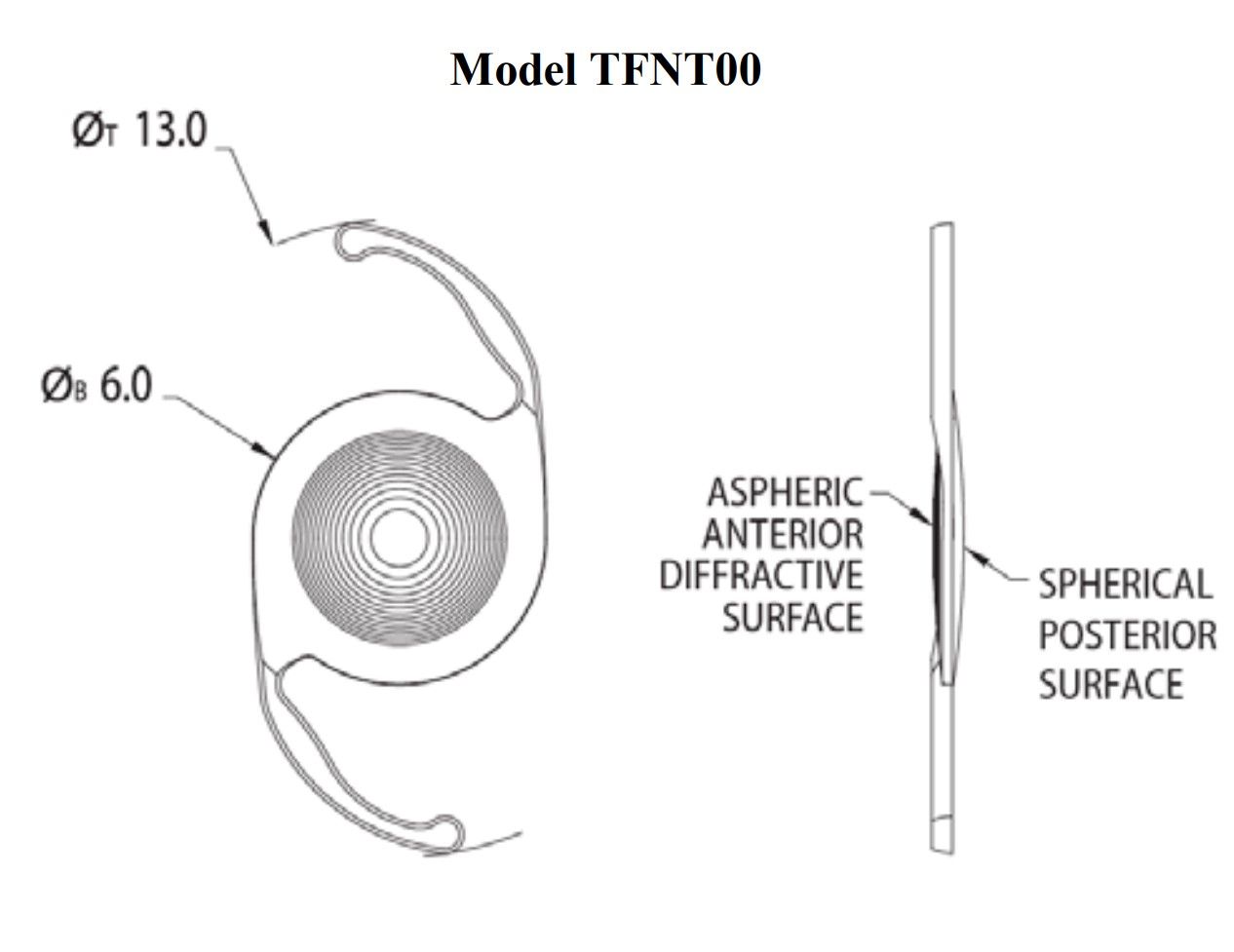

The heart of the CMU system is something they call a "computational lens." This isn't a traditional lens in the optical sense. It's a hybrid device that combines traditional optical elements with digital control systems, allowing different parts of the lens to focus at different depths.

The system uses several components working in concert. The first is a Lohmann lens—a pair of cubic lenses that can shift position relative to each other. By adjusting their alignment, the system can tune focus characteristics across the entire image. But a Lohmann lens alone can't deliver panoptic focus. You'd still get varying focus across the image, not simultaneous sharp focus everywhere.

That's where the spatial light modulator comes in. This device sits behind the Lohmann lens and controls how light bends at each individual pixel. Think of it as a grid of millions of tiny lenses, each one adjustable independently. By programming different focus characteristics for different pixels, the system can ensure that a pixel capturing a close object focuses differently than a pixel capturing a distant object—all within the same exposure.

But having the optical hardware is only half the battle. The system needs to know which pixels should focus at which depths. This is where the autofocus algorithms become critical. The researchers integrated two complementary autofocus approaches.

Contrast-Detection Autofocus (CDAF) analyzes the image in regions and finds the focus setting that maximizes contrast in each region independently. High contrast indicates sharpness. By maximizing contrast across all regions simultaneously, the system can keep everything sharp. This approach works through analyzing the image content itself and is computationally elegant.

Phase-Detection Autofocus (PDAF) takes a different approach. It analyzes the phase of light hitting different parts of the sensor and detects whether content is in focus and which direction to adjust for better focus. This is the same technology used in many modern smartphone cameras for fast autofocus. By combining these two approaches, the system can adapt to different types of subjects and lighting conditions.

The genius of the approach lies in real-time decision making. The camera isn't choosing a single focal distance and staying with it. Instead, during the exposure, the system is continuously analyzing different regions of the scene and adjusting focus characteristics pixel-by-pixel to keep everything sharp. It's happening so fast and seamlessly that it feels instantaneous to the user.

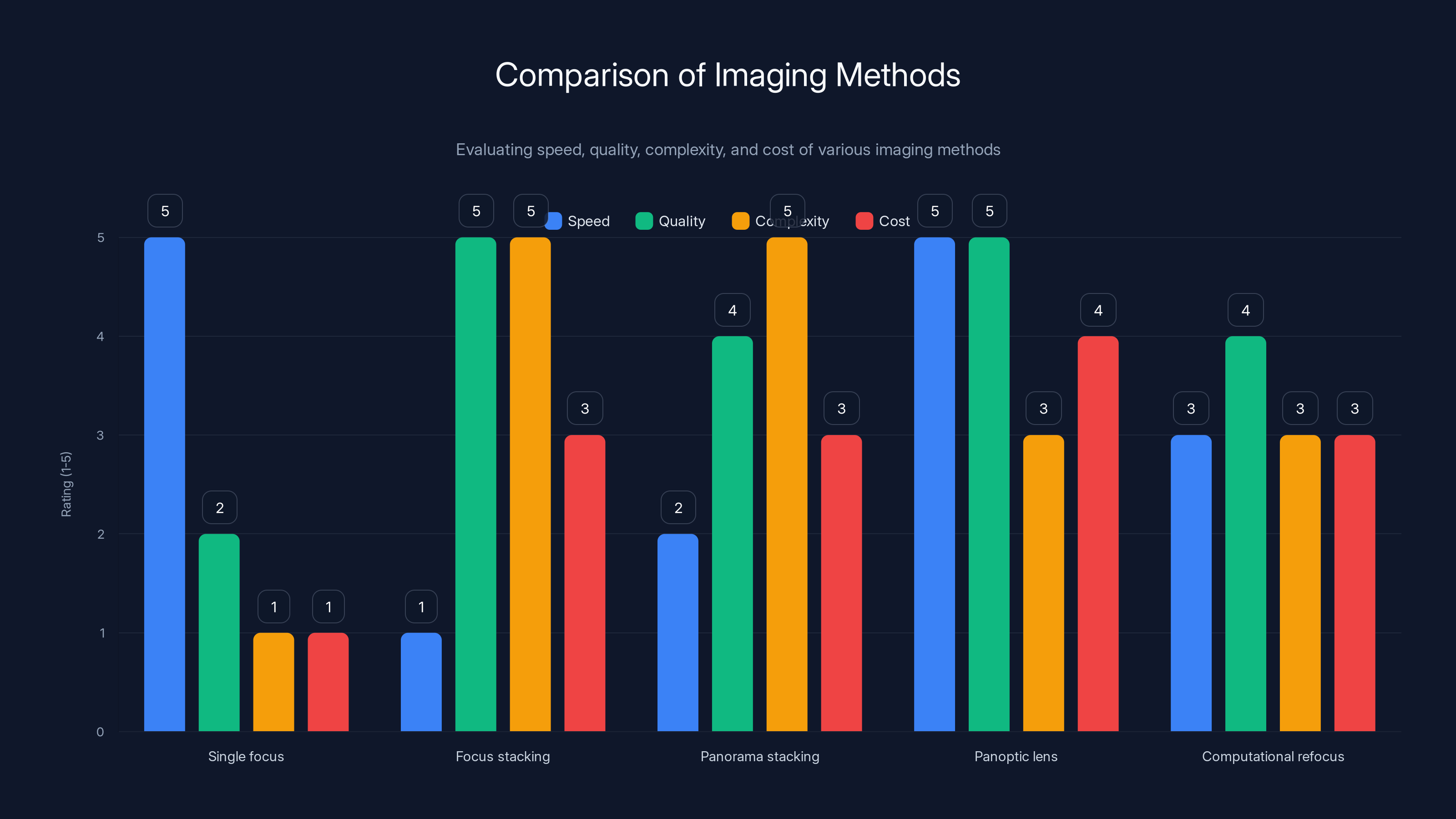

Panoptic lens technology offers excellent image quality and speed, making it ideal for dynamic subjects, despite its higher cost. Estimated data.

Comparison: Panoptic Lens vs. Traditional Methods

Understanding what makes panoptic lens technology remarkable requires comparing it to existing approaches for achieving sharp images across varied depths.

| Method | Speed | Quality | Complexity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single focus | Instant | Limited depth | Minimal | Low |

| Focus stacking | Very slow | Excellent | High | Medium |

| Panorama stacking | Slow | Good | High | Medium |

| Panoptic lens | Instant | Excellent | Moderate | High |

| Computational refocus (light field) | Medium | Very good | Moderate | Medium |

Focus stacking remains the gold standard for maximum image quality when you're willing to invest time. A photographer can take twenty shots at different focal distances and blend them perfectly. But this only works for stationary subjects. The moment something moves, the approach breaks down.

Panoptic lens technology matches or exceeds the quality of focus stacking while capturing everything in a single exposure. That single exposure capability means it works with moving subjects, works in real-time, and produces consistent results without the artifacts that sometimes appear at blend boundaries in focus-stacked images.

Real-World Imaging: What These Photos Actually Look Like

The CMU team demonstrated their breakthrough using real photographs. When comparing a conventional lens photograph to an image captured through their panoptic lens system, the difference is immediately striking. The conventional photo shows the typical depth-of-field effect: a sharp subject in the middle distance with foreground and background completely blurred. The panoptic lens image shows everything in perfect focus from the nearest object to the farthest background.

The detail is remarkable. You can count individual leaves in both foreground and background foliage. Window details are sharp both on a nearby wall and on a building ten times farther away. Complex scenes with multiple planes of depth—exactly the scenarios that have always challenged photographers—suddenly become easy to capture in perfect detail.

But here's something counterintuitive: the images don't look unnatural. They don't have that artificial hyperclarity that comes from aggressive sharpening. Instead, they just look like what you see when you look at a scene—everything relatively sharp because your eye is constantly adjusting focus as you scan the scene. The panoptic lens essentially captures that integrated visual experience in a single image.

This points to an important distinction. Humans don't see depth of field. We see a sharp world because our brain integrates information from constant tiny eye movements and autofocus adjustments. Shallow depth of field is actually an artistic convention in photography, not a representation of how we naturally see. Panoptic lens technology aligns imaging with actual human vision more closely than traditional photography ever could.

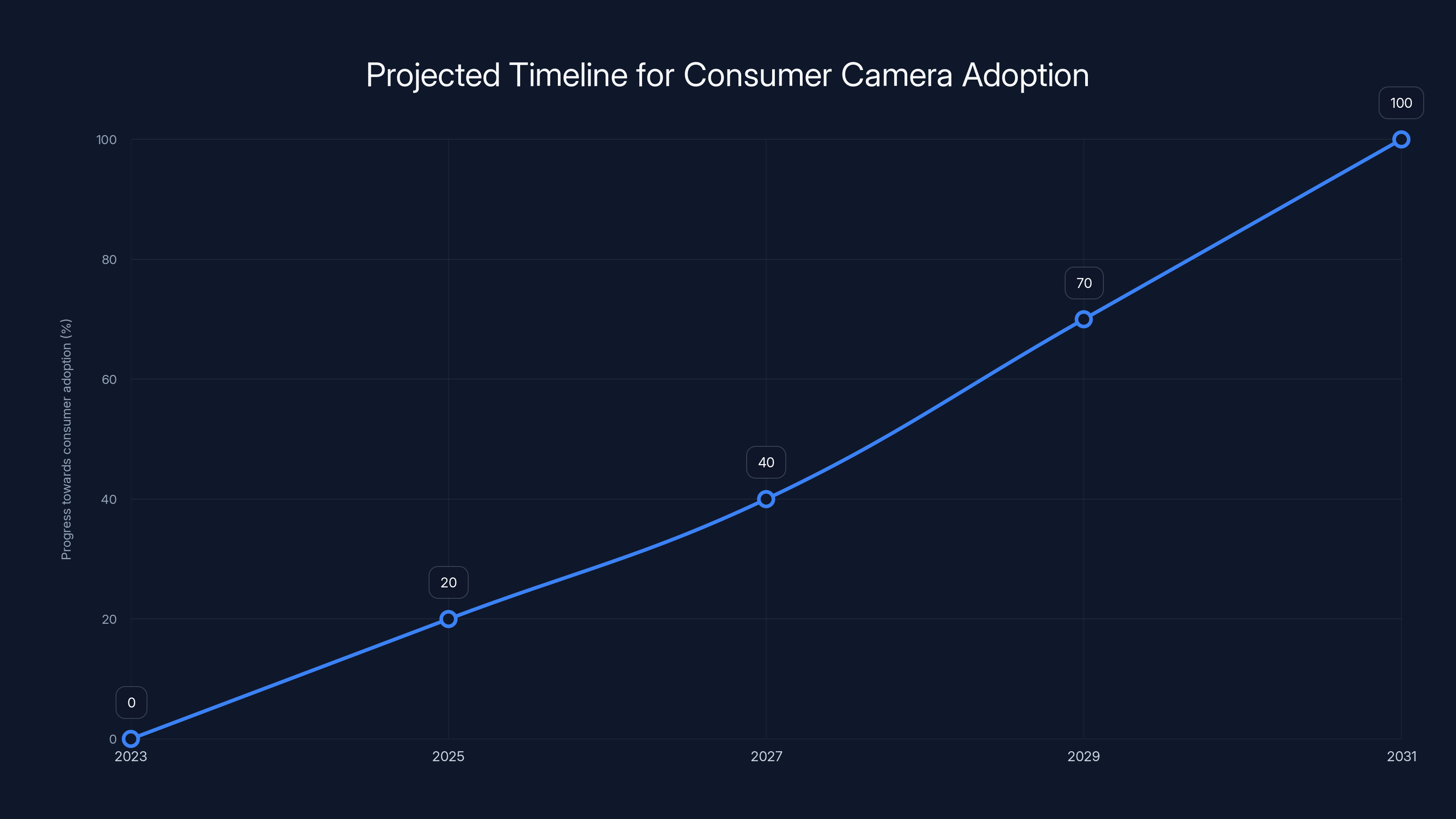

Estimated data suggests that consumer adoption of panoptic lens technology could be achieved by 2031, following trends similar to past optical innovations.

The Optical Physics Behind the Breakthrough

To truly understand why this is significant, you need to grasp the optical mathematics that traditional lenses follow. A simple lens equation governs how any single-element lens focuses light:

Where

Traditional lens design has always accepted this constraint and optimized within it. Better lens coatings reduce glare. Aspherical elements reduce aberrations. Multiple lens elements improve corner sharpness. But no traditional design can overcome the fundamental limitation that a fixed optical system focuses at one distance.

The Lohmann lens component adds a degree of freedom that traditional lenses lack: variable curvature. By sliding one lens element relative to another, the system changes the effective focal length continuously. But this alone still produces a single focal plane—just a tunable one.

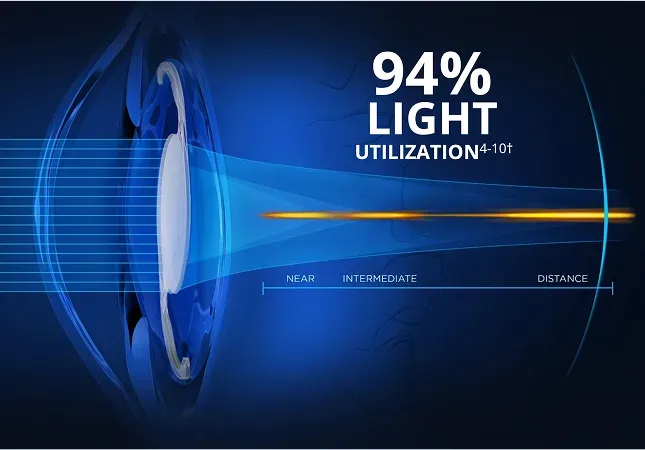

The spatial light modulator is where the true breakthrough happens. This device operates on a completely different principle. Instead of accepting that light must converge to a single point, it modulates the phase of light passing through each pixel. Phase modulation is a spatial filtering technique that can create complex wavefronts instead of simple convergent light.

By precisely controlling the phase at millions of points across the image, the system can create a wavefront that converges differently at different image locations. A pixel imaging a nearby object gets a wavefront that converges near to the lens. A pixel imaging a distant object gets a wavefront that converges far from the lens. All of this happens within a single optical path during the same exposure.

This is computationally intensive to calculate. The researchers needed to solve an inverse problem: given the depths of different scene elements and desired properties of the output image, what phase pattern at the spatial light modulator would produce perfect focus everywhere? Their solution involved sophisticated optimization algorithms that map scene geometry to modulator control signals in real time.

From Lab to Market: The Path to Consumer Cameras

The natural question when hearing about this breakthrough is: when can I buy a camera with this technology?

The honest answer: probably not soon, and maybe not for a while.

The current system is complex, expensive, and requires substantial computational power. The spatial light modulator devices are precision optical components that cost thousands of dollars. The autofocus algorithms require significant processing power. The entire system needs sophisticated calibration before use.

Most importantly, the system hasn't yet been miniaturized. Current prototypes are lab demonstrations mounted on optical benches. They're not portable, not integrated into camera bodies, and nowhere near the form factor of professional or consumer cameras.

Historically, this is the typical progression for optical innovations. When digital imaging first appeared, it seemed impossibly complex and expensive. Now it's everywhere because the underlying technology proved viable and miniaturization became achievable.

For panoptic lens technology to reach consumers, several things need to happen. The spatial light modulator devices need to become smaller and cheaper, likely through advances in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) or liquid crystal technology. The computational requirements need to decrease through algorithm optimization and specialized hardware acceleration. The overall system architecture needs to be re-engineered to fit inside a camera body.

There's also the question of whether the market actually wants this. Shallow depth of field is deeply embedded in photography culture. Portrait photographers create their reputation on background blur. Cinema uses shallow focus as a storytelling tool. Entire genres of photography are built around depth-of-field as an artistic element.

Panoptic lens technology doesn't eliminate shallow depth of field as an option. You could still choose to apply depth-of-field effects in post-processing if desired. But its availability would shift artistic conventions. Some photographers would embrace it enthusiastically. Others might resist the loss of depth of field as a compositional constraint.

Different photography types face varying levels of depth of field challenges, with food and architectural photography often requiring more precise focus control. Estimated data.

Beyond Photography: Applications in Science and Industry

While consumer photography applications grab headlines, the broader implications of panoptic lens technology extend far beyond taking better pictures.

In microscopy, depth of field is a critical limitation. Modern microscopes can achieve incredible magnification—seeing individual cells, bacteria, even viruses—but the depth of field shrinks proportionally. At high magnification, focus is measured in micrometers. Researchers constantly struggle to image thick biological samples where different structures exist at different focal depths. Panoptic lens technology in microscopes could image entire cell layers in sharp focus, enabling new research methodologies and reducing image processing complexity.

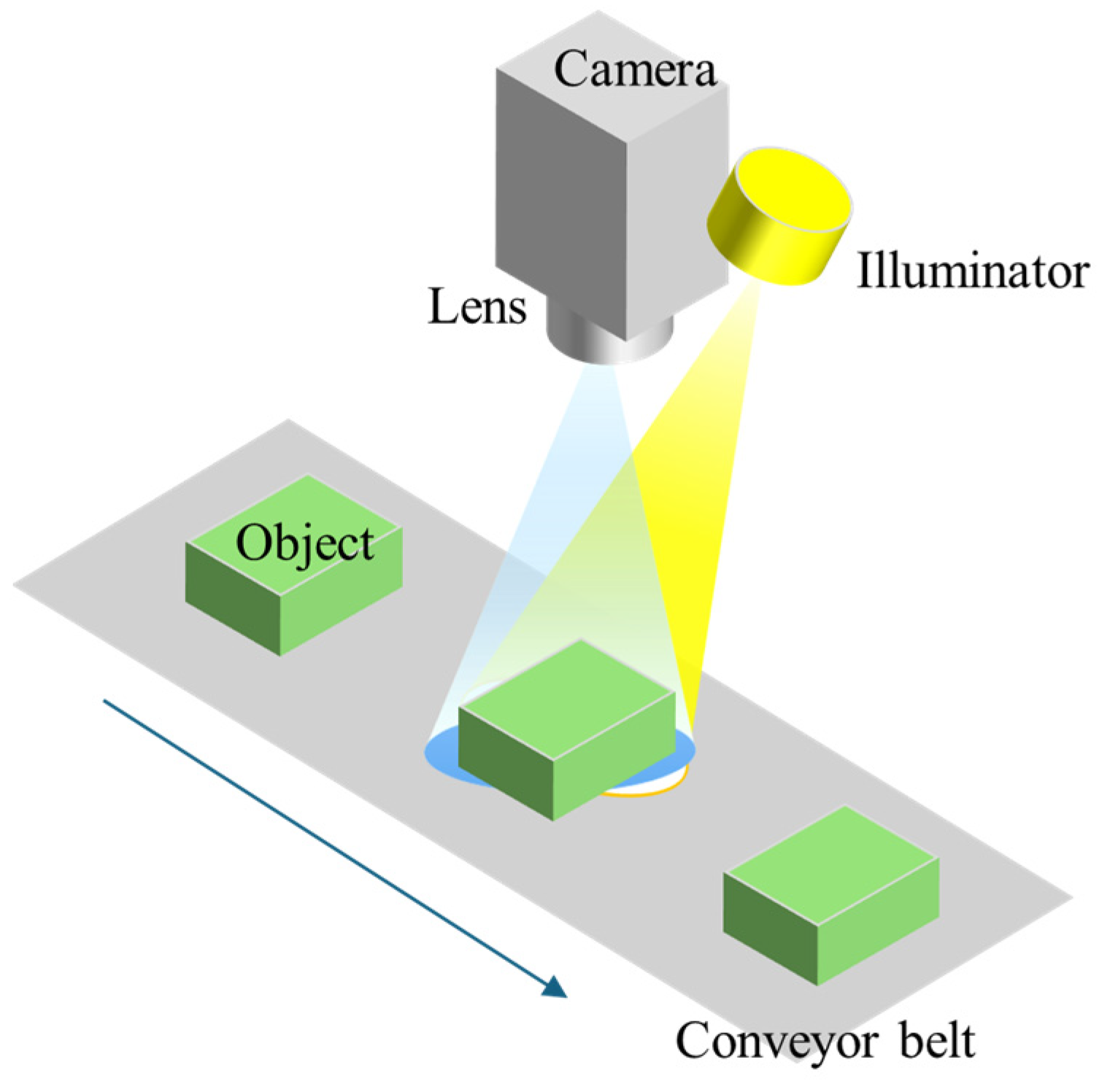

Autonomous vehicles face a different depth challenge. Computer vision systems for self-driving cars need to detect and track objects at varying distances. A pothole two feet away requires sharp focus. A pedestrian fifty feet away requires equally sharp focus. Oncoming traffic two hundred feet away can't be missed. Current camera systems handle this through computational tricks—multiple exposures, clever algorithms—but panoptic lens technology would natively provide the visual information without computational complexity. This could reduce processing latency and improve reliability of perception systems.

Virtual reality headsets have been struggling to achieve true depth perception. Current VR displays show the same virtual image distance regardless of where you focus your eyes. This mismatch between accommodation (the eye's focusing mechanism) and convergence (where your eyes point) is a primary cause of VR-induced eye strain. If panoptic lens technology could enable depth-varying focus in VR displays, it could solve this problem and dramatically improve the VR experience.

Medical imaging benefits similarly. Endoscopic procedures require surgeons to navigate complex 3D anatomy while looking at a 2D monitor. If that monitor could show everything in sharp focus at all depths, it would reduce cognitive load and enable faster, more accurate procedures. Surgical planning becomes easier when you can see anatomy clearly at multiple depths simultaneously.

Astronomical observation represents another frontier. Telescopes are limited by aperture and atmospheric distortion. If panoptic lens systems could maintain focus across the expanded depth of focus that telescopes require, it could enable new observation techniques and improve data quality.

Scientific imaging more broadly—from materials science to fluid dynamics to biological research—could be transformed by equipment that naturally provides sharp imagery across multiple planes of focus.

The Role of Computational Photography in Modern Optics

Panoptic lens technology represents a philosophical shift in how we think about cameras. For most of photography's history, the camera was a purely optical device. Light entered through a lens, hit a sensor, and created an image. The computational layer was minimal.

Digital photography introduced computational elements—white balance correction, noise reduction, image compression—but the core capture remained optical. You captured what the optics gave you, then improved it through software.

Panoptic lens technology inverts this relationship. The optical system and computational system are inseparably intertwined. You can't explain what the camera captures by looking at just the optics or just the software. You need to understand how they work together.

This is part of a broader trend in modern imaging technology. Computational photography—using algorithms to enhance, extend, or fundamentally change how cameras capture images—has become the dominant frontier in camera innovation. Smartphone cameras use computational approaches to achieve effects that would require expensive hardware on traditional cameras. Night mode synthesizes multiple exposures. Portrait mode creates depth-of-field effects through computational segmentation. Zoom works through cropping and upsampling rather than physical lens elements.

Panoptic lens technology extends this trend by making computation a fundamental part of the optical path itself. The spatial light modulator is essentially a programmable optical element. Different programs loaded into it could change its behavior fundamentally.

This opens interesting possibilities. The same hardware might switch between panoptic focus mode (everything sharp) and traditional depth-of-field mode (shallow focus for artistic effect) through software changes. It might adapt its focus characteristics to the specific scene being captured. Professional versions might enable specialized behavior for microscopy, astronomy, or other technical applications.

The implications for camera design are profound. As optics become more dependent on computation, camera manufacturers will compete partly on processing power and algorithm sophistication rather than just optical quality. AI could optimize focus strategies in real-time based on scene analysis. Machine learning could improve autofocus speed and accuracy.

The panoptic lens maintains high clarity across all image sections, unlike conventional lenses which blur the foreground and background. Estimated data based on typical lens performance.

Technical Challenges Remaining

As exciting as panoptic lens technology is, significant challenges remain before it becomes commercially viable.

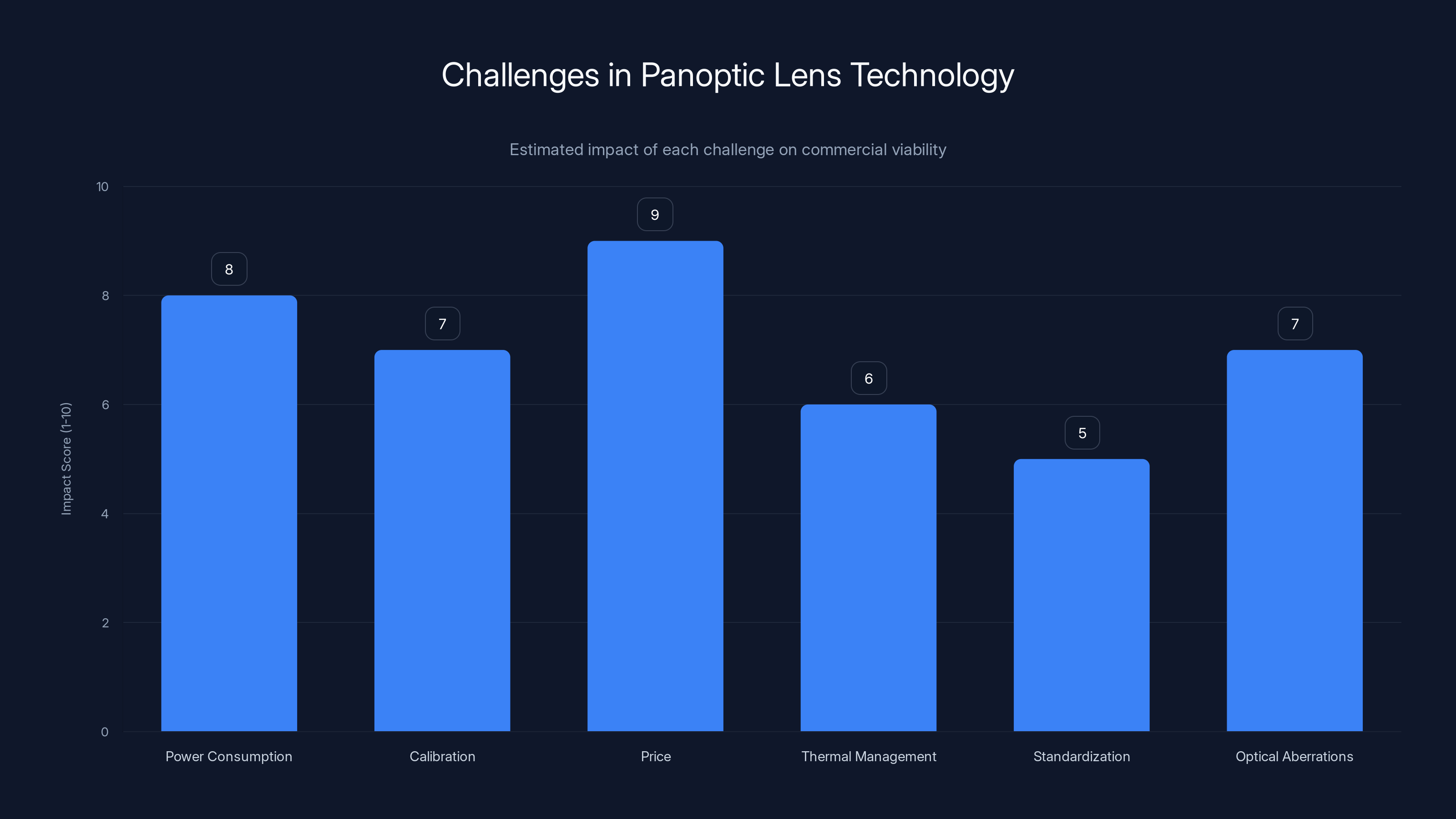

The first challenge is power consumption. Real-time computation of phase modulation patterns for millions of pixels requires substantial processing power. Each exposure would demand rapid calculations. In a consumer camera context, this would drain batteries quickly. Smartphone integration would be particularly challenging.

Calibration represents another hurdle. The spatial light modulator, Lohmann lens, and sensor all need to be precisely aligned and calibrated. Any misalignment degrades image quality. Environmental factors like temperature changes could shift the optical path. The system might need periodic recalibration. This is manageable in laboratory conditions or professional equipment but becomes a liability in consumer products.

Price represents an obvious barrier. Spatial light modulator devices cost thousands of dollars currently. Even if miniaturization reduces this to hundreds of dollars per unit, it would make cameras significantly more expensive. The computational overhead might require specialized hardware accelerators, adding further cost.

Thermal management could become problematic. The spatial light modulator generates heat when operating continuously. Fitting this into a compact camera body while keeping temperatures in acceptable ranges requires clever thermal engineering.

There's also the question of standardization. Does the industry adopt panoptic lens technology as a new standard? Or do specialist applications (microscopy, surveillance, autonomous vehicles) adopt it first while consumer cameras slowly follow? The answer affects the timeline and business case significantly.

Optical aberrations at the edges of the image field present another challenge. Even the best computational approaches can't completely eliminate optical imperfections. Getting truly uniform focus across the entire image frame, especially in the corners, requires more refinement.

Competitive Approaches and Alternative Technologies

Carnegie Mellon isn't the only research group pursuing solutions to the depth-of-field problem. Other approaches exist, each with different trade-offs.

Light field cameras represent one major alternative. These capture information about not just the intensity of light at each pixel, but also the direction the light is traveling. This allows computational refocusing after capture—essentially rendering different focal planes from a single exposure. Companies like Lytro pioneered this technology, though it never achieved mainstream adoption. Light field cameras sacrifice some resolution to capture directional information, and computational refocusing can't achieve the same quality as native focus.

Plenoptic imaging, which is conceptually similar to light field capture, offers another path. It's more successful in specialized applications than consumer cameras, but still involves quality trade-offs.

Wavelength-dependent focusing uses the fact that different colors of light focus at slightly different distances. By using this natural property, some researchers have developed systems that can keep different wavelengths in sharp focus simultaneously. This is promising for certain applications but doesn't solve the problem for monochromatic subjects.

Metasurface optics represents a newer frontier. These are optical elements made from manufactured nanostructures that can manipulate light in ways traditional lenses can't. They're still largely in research phases but could potentially enable panoptic-lens-like effects through entirely different mechanisms.

Adaptive optics, borrowed from astronomical observation, uses deformable mirrors to continuously adjust focus. This approach has proven effective in specific applications but requires the optical system to be dynamic—changing shape continuously. The current panoptic lens approach is less dynamically demanding.

Panoptic lens technology has advantages over most alternatives: it works with any subject matter, doesn't sacrifice resolution, and the quality of focus-everywhere images matches or exceeds traditional approaches. These advantages suggest it could eventually become the dominant approach if the manufacturing and cost challenges can be overcome.

Price and power consumption are the most significant challenges for panoptic lens technology, with high impact scores indicating major barriers to commercial viability. (Estimated data)

The Future of Photography: What Panoptic Lenses Mean for Your Camera

Imagine opening your camera app five years from now. You frame a shot with shallow-depth-of-field bokeh background. You tap the shutter. Now you can decide post-capture exactly where the focus should be. Better yet, you select "panoptic mode" and everything is sharp. You zoom in on different parts of the image—the background is just as detailed as the subject.

Or you're a wedding photographer. A ceremony has guests at varying distances from your position. Traditional photography requires choosing which row of guests to focus on. With panoptic lenses, everyone is in perfect focus. Your editing workflow simplifies because you're not managing focus compromise anymore.

Or you're a product photographer. Photographing a luxury watch requires capturing incredible detail across multiple levels of depth. The watch case, the dial, the numerals, the crystal top all sit at different focal distances. Panoptic lens technology captures all of it in sharp focus in a single exposure.

These scenarios require panoptic lens technology to become smaller, cheaper, and easier to integrate into consumer cameras. The research from Carnegie Mellon demonstrates the fundamental concept works. The path from breakthrough to product is well-established for optical innovations: refine the approach, optimize the manufacturing process, reduce costs through scale, integrate into products.

However, this path isn't guaranteed. Some optical innovations that seemed promising never achieved commercial success. Others took longer than expected. The panoptic lens breakthrough is real and meaningful, but its path to your camera isn't predetermined.

What seems most likely is staged adoption. Professional applications—microscopy, industrial vision, autonomous vehicles—will probably see panoptic lens technology first. These applications have limited cost sensitivity and can justify expensive equipment if the capability advantage is large enough. Professional photographers in specialized niches might access this technology within five to seven years.

Consumer adoption would follow after costs decrease and systems are miniaturized. Full integration into smartphone cameras might take ten to fifteen years, though initial versions in professional mirrorless cameras could appear sooner.

The technology will also spark new artistic movements. When the technical limitation disappears, how will photographers adapt? Some will celebrate panoptic focus as liberation from a constraint that limited their vision for a century and a half. Others might deliberately choose shallow depth of field as an artistic statement precisely because it's no longer necessary.

Film cinematography could also be affected eventually. Cinema has used depth of field strategically—shallow focus isolates subjects, deep focus creates immersive scenes. If cinematographers could pan-focus different elements at different focal distances within the same shot, entirely new visual languages become possible.

Real Research Context: What the Carnegie Mellon Team Actually Demonstrated

It's worth understanding what exactly the researchers accomplished versus what's still theoretical. The CMU team published research documenting a working computational lens system. They demonstrated it with real photographs of actual scenes, not computer simulations.

The system successfully combined multiple optical components and autofocus algorithms to capture images with sharp focus across multiple depths. The resulting images showed genuine visual improvements over traditional depth-of-field-limited photographs. This is a genuine breakthrough—the core concept has been validated experimentally.

However, the current implementation is still far from consumer-ready. The system operates in controlled laboratory conditions. Processing speeds are slower than real-time video capture. The physical footprint is larger than any commercial camera. The computational requirements are substantial.

The researchers themselves described potential applications—autonomous vehicles, VR, microscopy—suggesting they understand the broader implications. Their discussion of future work indicates they're focused on miniaturization, speed improvement, and practical implementation rather than proving the concept works.

This is actually progress beyond what many breakthroughs accomplish. Many innovations that seem revolutionary in research papers never advance beyond proof-of-concept. The CMU team didn't just prove the concept works; they demonstrated it produces genuinely useful images.

The peer review process for their published research validated their methodology and findings. This isn't a press release or preliminary result—it's peer-reviewed scientific work that other researchers can reproduce and build upon.

This context matters because it helps calibrate expectations. This is a real breakthrough that will likely influence imaging technology development. It's not about to appear in your camera next month. But it's also not mere theoretical possibility. It's a working prototype that demonstrates genuine capability.

Panoptic Lens Technology and Artificial Intelligence Integration

One fascinating aspect of panoptic lens technology is how naturally it integrates with AI. The autofocus algorithms that optimize focus characteristics could be enhanced through machine learning. Instead of following fixed rules, AI could learn optimal focus patterns for different scene types.

Scene understanding through computer vision could inform autofocus strategy. The camera could recognize a landscape and apply panoptic focus across all depths. For a portrait, it might choose to add subtle depth-of-field effects despite the panoptic capability, using the additional focus information to enhance subject separation.

AI could also optimize for specific use cases. A medical imaging AI might prioritize sharp focus on relevant anatomy while accepting some blur in irrelevant structures. A surveillance camera AI might maintain equal focus on all depths for maximum situational awareness.

The spatial light modulator itself becomes programmable in ways that go beyond traditional optics. Different AI models could be deployed for different applications, essentially giving the same hardware different optical characteristics through software.

This convergence of optical innovation and AI represents the future of imaging technology. Cameras won't just capture light—they'll understand scenes, optimize their response, and learn from experience. Panoptic lens technology makes this convergence more powerful because the hardware itself becomes more flexible.

Smartphone cameras, which have led computational photography innovation, could integrate panoptic lens concepts in simpler forms initially. The processing power already present in modern phones could handle the necessary computations. The challenge is miniaturizing the optical components.

Once AI-informed panoptic lens systems become reality, the camera becomes far more intelligent. It doesn't just record what it sees; it captures what matters and optimizes the capture for specific purposes.

Economic and Market Implications

From a market perspective, panoptic lens technology represents a significant shift. Current camera manufacturers invest heavily in optical engineering—designing better lenses, multiple lens elements, specialized glass formulations. These are expensive but necessary for quality improvements.

Panoptic lens technology shifts leverage toward computational capability and precision manufacturing. The spatial light modulator requires sophisticated fabrication facilities. The software becomes equally important as the hardware. This could favor manufacturers with strength in both areas—companies like Apple, Google, Samsung—over traditional camera makers focused primarily on optical design.

Alternatively, traditional camera manufacturers might acquire or partner with companies developing spatial light modulator technology, just as they've acquired computational photography startups in recent years.

The market impact extends beyond camera hardware. Entire industries built around traditional depth-of-field limitations might shift. Speciality glass manufacturers have thrived creating expensive lenses designed to minimize depth-of-field effects or maximize it. Some of that market value could transfer to companies making optical modulators and computational systems.

Competition dynamics could also shift. Smartphone camera competition has commoditized many optical innovations quickly. Panoptic lens technology might follow a similar path—initial premium adoption, rapid cost reduction, eventual widespread availability.

Geographically, panoptic lens technology development might concentrate in regions with strong computational photography expertise and precision manufacturing capabilities—primarily East Asia, Silicon Valley, and other major tech hubs.

Surprisingly, panoptic lens technology might also impact used camera values. As the capability becomes more common, older cameras with traditional depth-of-field limitations might see value decrease. But this is speculative—entire new genres of cameras might emerge that aren't direct replacements for existing products.

Optical Myths Panoptic Lenses Will Shatter

Certain ideas about camera optics have been accepted as immutable truth for so long they feel like laws of physics. Panoptic lens technology challenges several of these assumptions.

Myth One: "You must choose between shallow depth of field and universal focus." Reality: Panoptic lenses can capture unlimited depth information and apply depth-of-field effects selectively in post-processing. You get both benefits.

Myth Two: "Better depth of field requires better lenses." Reality: With panoptic lenses, optical design becomes less critical for focus characteristics. The computation handles more of the work. Optical design still matters for resolution and aberration control, but it's decoupled from depth-of-field capability.

Myth Three: "You can't focus on everything without stopping down to narrow apertures and sacrificing light." Reality: Panoptic lenses maintain wide apertures while focusing everything. More light enters the camera while keeping everything sharp.

Myth Four: "Depth of field is an unavoidable optical effect." Reality: Depth of field is a feature of conventional single-focal-plane optics. Different optical approaches enable different capabilities.

Myth Five: "Cameras see the world as humans do." Reality: Cameras have always seen differently—with fixed depth of field instead of dynamic accommodation. Panoptic lenses actually bring camera vision closer to human vision.

These myths have influenced photography for so long they shaped entire artistic traditions. Challenging them is philosophically significant, not just technically important.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Visual Technology

The Carnegie Mellon panoptic lens breakthrough represents more than an incremental improvement in camera technology. It's a paradigm shift—a fundamental change in how imaging systems can work.

For 150 years, depth of field has been an unavoidable constraint. Photographers adapted creatively, developing aesthetic traditions around shallow focus and composition within tight focal planes. This constraint shaped artistic conventions so thoroughly that depth of field became considered a feature rather than a limitation.

Panoptic lens technology removes that constraint optically while maintaining the capability to apply depth effects computationally. This freedom could unleash new possibilities in photography, cinematography, microscopy, autonomous vehicles, and countless imaging applications.

The path from breakthrough to product is neither quick nor guaranteed. Miniaturization, cost reduction, and practical implementation all require substantial engineering work. Five to fifteen years before consumer availability seems realistic, with specialized applications adopting the technology sooner.

Yet the significance of the breakthrough is already clear. The researchers demonstrated that the optical limitation that has constrained imaging for over a century can be overcome. They did it with a working system that produces genuinely superior images. The question isn't whether panoptic lens technology is possible—it's definitely possible. The question is how quickly the technology can be refined, miniaturized, and deployed.

When panoptic lenses do become commonplace, they'll fundamentally change how we photograph, how we observe the microscopic world, how autonomous vehicles perceive their surroundings, and how we think about optics itself. The breakthrough comes from recognizing that optical constraints aren't immutable laws—they're design choices that computational approaches can overcome.

For photographers, this represents liberation from a fundamental constraint that has defined the medium since its inception. For scientists and engineers, it opens new capabilities in imaging-dependent research and technology. For technology companies, it represents a new frontier in computational imaging competition.

The experimental camera that can focus on everything at once is no longer just a theoretical possibility. It's a working demonstration of a future where depth of field becomes optional rather than inevitable—a future where imaging technology finally matches the sophistication of human vision.

TL; DR

- Panoptic Lens Breakthrough: Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University demonstrated a computational lens system that brings every part of a scene into sharp focus simultaneously, eliminating traditional depth-of-field limitations.

- How It Works: The system combines a Lohmann lens (adjustable curved lenses), a spatial light modulator (pixel-level optical control), and dual autofocus algorithms (CDAF and PDAF) to focus different image regions at different depths simultaneously.

- Current Status: The technology is a working prototype in laboratory conditions, not yet commercially available. Real photographs demonstrate genuine capability, but miniaturization and cost reduction are needed for market deployment.

- Timeline and Market: Consumer cameras might see this technology in 5-15 years, with professional applications and specialized industries (microscopy, autonomous vehicles, VR) adopting it sooner.

- Broader Implications: Beyond photography, panoptic lens technology could transform microscopy, autonomous vehicle perception, VR depth perception, medical imaging, and scientific research by providing native sharp focus across multiple depths simultaneously.

FAQ

What is panoptic lens technology?

Panoptic lens technology is an optical innovation that enables cameras to capture sharp focus across all depths simultaneously, rather than the traditional limitation of focusing on a single plane. Developed by Carnegie Mellon University researchers, the system uses a Lohmann lens (adjustable cubic lenses) combined with a spatial light modulator (a device that controls light bending at each pixel) along with sophisticated autofocus algorithms to achieve uniform focus across varied distances in a single exposure.

How does panoptic lens technology work?

The system works through three coordinated components. First, a Lohmann lens—two adjustable curved lenses that shift position—provides tunable focus characteristics. Second, a spatial light modulator acts as a programmable optical element, controlling how light bends at each individual pixel across the entire image. Third, dual autofocus algorithms (Contrast-Detection Autofocus and Phase-Detection Autofocus) analyze the scene and optimize focus settings pixel-by-pixel in real-time, ensuring different depths achieve sharp focus simultaneously during a single exposure.

What are the main benefits of panoptic lens technology?

The primary benefits include capturing unlimited depth detail in single exposures (eliminating the need for focus stacking), maintaining wide apertures while achieving universal focus (better light collection than traditional deep-focus methods), improving image quality through avoiding blend artifacts from multiple exposures, enabling better performance with moving subjects, and providing a foundation for computational photography integration. Additional benefits extend to scientific applications like microscopy, autonomous vehicle perception, VR depth perception, and medical imaging where simultaneous focus across multiple depths is critical.

When will panoptic lens cameras be available commercially?

Consumer cameras with panoptic lens technology are likely 5-15 years away from mainstream availability, depending on how quickly the technology can be miniaturized and manufacturing costs reduced. Professional and specialized applications—microscopes, autonomous vehicle systems, industrial imaging, and professional cinema cameras—will likely adopt the technology sooner, potentially within 5-10 years. Initial implementation in expensive professional equipment before eventual integration into consumer smartphones and cameras is the most probable path.

How is panoptic lens technology different from focus stacking?

Focus stacking involves capturing multiple images at different focal distances and blending them computationally—a slow, post-processing approach that only works with stationary subjects. Panoptic lens technology captures everything in sharp focus in a single exposure during capture itself. This single-exposure approach works instantly with moving subjects, produces images without blend artifacts, requires no post-processing, and works in real-time situations like video recording where focus stacking is impractical. The quality of panoptic-focused images matches or exceeds focus-stacked results while being faster and more practical.

What are the main technical challenges preventing commercialization?

Key challenges include miniaturizing spatial light modulator components from laboratory-size to camera-body-compatible dimensions, reducing costs (current SLM devices cost thousands of dollars), handling computational power requirements without excessive battery drain, maintaining precise calibration in consumer-grade conditions, thermal management of components generating heat during operation, eliminating optical aberrations that may persist at image edges, and developing manufacturing processes that can produce these precise optical systems at scale. Additionally, the technology must prove reliable in consumer conditions with varying temperatures, humidity, and handling.

How will panoptic lenses change photography as an art form?

Panoptic lens technology removes a fundamental constraint that has shaped photographic aesthetics for 150 years. While depth-of-field effects can still be applied selectively through post-processing, the loss of depth-of-field as a necessary limitation could shift artistic conventions. Some photographers may embrace panoptic focus for universal clarity, while others might deliberately choose shallow depth of field as an artistic statement precisely because it's no longer required. New visual languages and compositional approaches may emerge when focus is no longer a limiting factor. The technology liberates photographers from a technical constraint while making depth-of-field an aesthetic choice rather than an optical necessity.

What industries beyond photography will benefit most from panoptic lens technology?

Autonomous vehicles stand to gain significantly by having perception systems with native sharp focus at all distances simultaneously, improving object detection and classification reliability. Medical imaging and minimally invasive surgery benefit from endoscopes showing all anatomical depths in sharp focus. Scientific microscopy becomes more powerful when entire cell layers can be imaged sharply without focus stacking. Virtual reality achieves true depth perception and reduces eye strain by matching accommodation with convergence. Astronomical observation could improve through better focus across expanded depth ranges. Surveillance and security systems gain clearer information at all distances. These specialized applications will likely drive early adoption and justify initial high costs.

Is panoptic lens technology fundamentally different from how human eyes work?

Paradoxically, while traditional cameras have always worked differently from human vision (with fixed depth of field), panoptic lenses actually make cameras more like human vision. Human eyes don't have depth-of-field limitations—we see a sharp world because our brains constantly adjust focus through micromovements and accommodation adjustments. Panoptic lenses capture this integrated visual experience in single photographs, more closely matching human visual perception than traditional cameras ever could. However, humans do use depth of field in specific contexts (when fatigued, when focusing intently), so the comparison is complex.

Could panoptic lens technology eventually make traditional camera lenses obsolete?

It's unlikely that panoptic lens technology will completely replace traditional optical lenses in the near term. Traditional optics will likely persist in applications where simplicity, cost, and reliability are paramount, and in specialized applications where specific optical characteristics are desired. However, as panoptic lens systems become smaller and cheaper, they could eventually dominate in premium consumer cameras, professional equipment, and any application where flexibility in focus characteristics is valuable. Traditional lenses might remain in budget cameras and very specialized applications, similar to how film cameras persisted after digital adoption. The transition would likely span decades rather than being sudden obsolescence.

What research has validated panoptic lens technology?

The primary validation comes from peer-reviewed research published by Carnegie Mellon University researchers, who demonstrated working prototypes capturing real photographs that show genuine improvement over traditional depth-of-field-limited images. The research has undergone academic peer review, validating the methodology and findings. The system successfully integrated multiple optical components (Lohmann lens, spatial light modulator) with sophisticated autofocus algorithms to achieve the stated goal of sharp focus across variable depths. While the current system remains in laboratory conditions, the successful demonstration of working prototypes with high-quality output provides strong evidence that the fundamental concept is sound and viable for further development.

Key Takeaways

- Panoptic lens technology uses Lohmann lenses and spatial light modulators to achieve sharp focus at all depths simultaneously in a single exposure

- The breakthrough from Carnegie Mellon University demonstrates working prototypes capturing superior images without depth-of-field limitations

- Consumer camera adoption is likely 5-15 years away, while specialized applications in microscopy, autonomous vehicles, and VR could arrive sooner

- The technology removes a 150-year-old optical constraint, fundamentally changing how cameras capture and represent scenes

- Panoptic lenses will transform scientific imaging, autonomous vehicle perception, microscopy, and medical procedures by providing native sharp focus across multiple depths

Related Articles

- Xbox 2026 Predictions: Halo on PlayStation, Fable Returns [2025]

- Fallout Season 2 Episode 3 Release Date on Prime Video [2025]

- Windows 10's Legacy: What Microsoft Got Right (and How It Led to Windows 11 Problems) [2025]

- iMP Tech Mini Arcade Pro Review: Nintendo Switch Arcade Cabinet [2025]

- Essential Cybersecurity Habits for 2026: Expert Guide [2025]

- Elizabeth Lopatto: The Verge's Internet Typist on Beat Diversity [2025]

![Panoptic Lens Technology: The Camera That Focuses Everything at Once [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/panoptic-lens-technology-the-camera-that-focuses-everything-/image-1-1767020824635.jpg)