Pentagon's Influencer Press Corps Replaces Journalists: The Venezuela Test

When Nicolás Maduro vanished from public view in early 2025, something equally striking happened in the corridors of the Pentagon. The journalists who'd spent decades covering defense policy, military operations, and geopolitical strategy weren't the ones breaking the story. Instead, right-wing influencers with millions of social media followers—many with zero military journalism experience—flooded platforms with commentary, memes, and hot takes.

This wasn't an accident. It was the deliberate result of a fundamental restructuring of how the Pentagon communicates with the public.

Last November, the Defense Department implemented a press policy that effectively locked out traditional newsrooms. Major outlets like ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox News refused to comply with new restrictions that prevented journalists from accessing information the Pentagon hadn't officially released. Rather than fight for access, they pulled out. The Pentagon didn't miss them. Instead, the department handed press credentials to content creators like Tim Pool, independent commentators with massive followings but no background in defense reporting, and members of Turning Point USA, an organization known more for political activism than journalism.

The result is a cautionary tale about how institutions can weaponize information gatekeeping, and how the information ecosystem becomes vulnerable when legitimate journalism is replaced by ideological allegiance.

TL; DR

- Pentagon policy shift: The Defense Department implemented restrictions in November 2024 that effectively banned traditional mainstream media outlets from accessing non-public information

- Credentialing influencers: Right-wing content creators replaced departing journalists, with figures like Tim Pool and Turning Point USA members gaining official press access

- Absence of reporting: The newly credentialed influencer press corps failed to report any substantive information about the Venezuela operation, instead producing memes and political commentary

- Historical precedent: The situation mirrors Iraq War-era blogging, when pro-war commentators attacked mainstream journalists while amplifying government narratives

- Information control mechanism: The restructuring appears designed not for transparency, but to control messaging through ideologically aligned creators who amplify rather than scrutinize

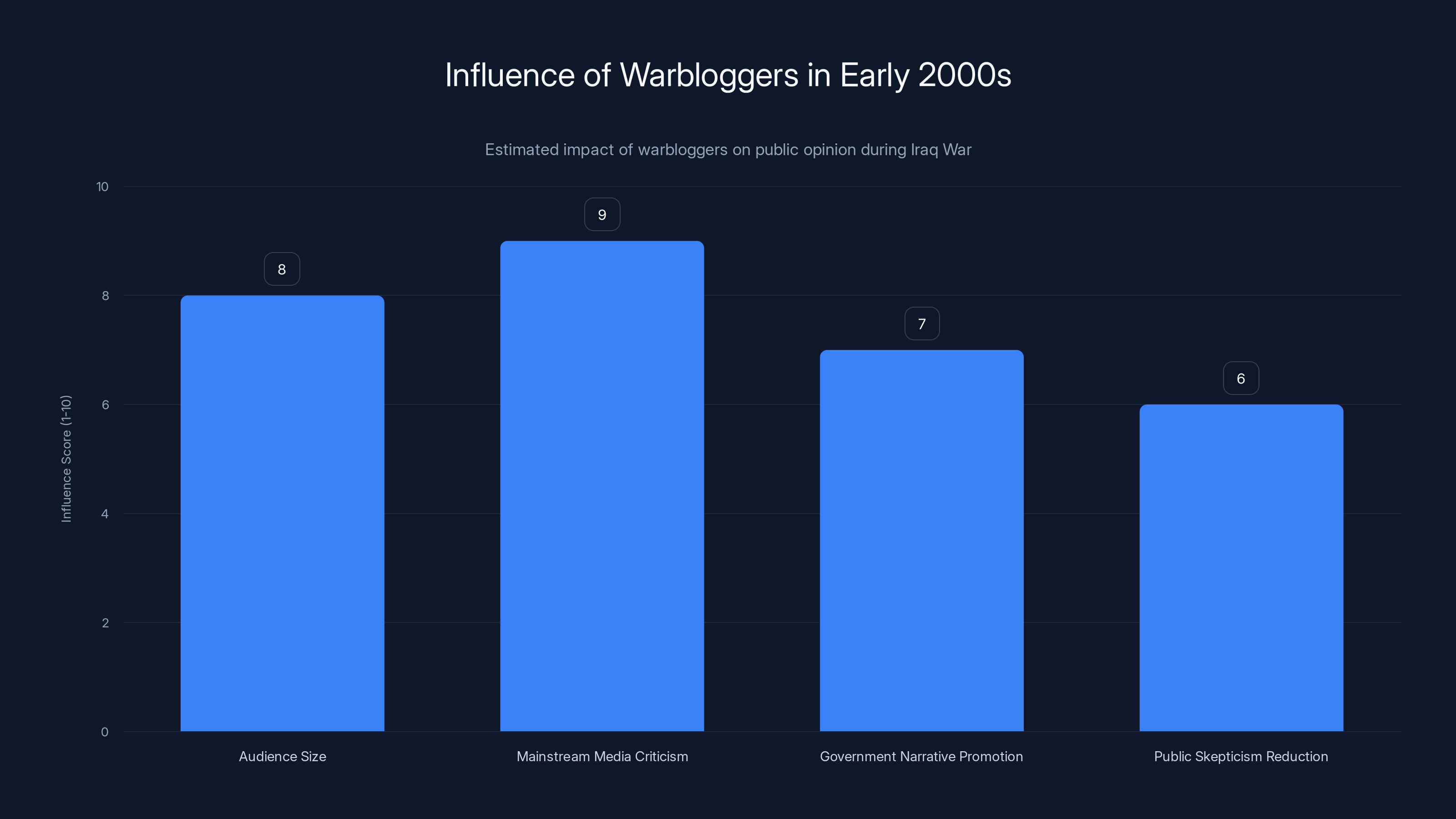

Warbloggers in the early 2000s had a significant impact on public opinion by criticizing mainstream media and promoting government narratives, reducing public skepticism. Estimated data.

How the Pentagon's Press Policy Changed Everything

The shift didn't happen overnight, but it was deliberate. In early November 2024, the Pentagon announced a new press credential policy that fundamentally altered access rules. The key restriction: journalists couldn't access information unless the Defense Department made it publicly available first.

This sounds mundane until you understand what it actually means. Traditionally, military journalists have had tiered access. They can request official comments, ask clarifying questions about operations, and receive background briefings. The new policy eliminated this. If the Pentagon hadn't formally announced something, journalists had no way to report on it—no matter how significant.

Major news organizations understood the implication immediately. If you can't do your job as a journalist, why keep your reporters there?

ABC pulled its Pentagon correspondent. CBS did the same. NBC's military beat reporter left the building. Even Fox News, hardly a bastion of liberal media, initially resisted the new terms. These weren't minor outlets staffed by one or two people. These were the organizations with institutional memory, experienced reporters who'd covered military operations for decades, and editorial processes designed to verify information before publication.

The vacuum they left was filled almost instantly. The Pentagon's new press secretary, Kingsley Wilson, who'd previously worked in digital media for the Center for Renewing America (a pro-Trump think tank), made clear how the institution viewed this exodus. "Legacy media chose to self-deport from this building," Wilson said at the first briefing with the new credentialed press corps. "We're not going to beg these old gatekeepers to come back, and we're not rebuilding a broken model to appease them. Instead, we're welcoming new media outlets that actually reach Americans."

This framing is revealing. The Pentagon wasn't simply replacing journalists with other journalists. It was explicitly welcoming a new type of media presence—one that "reaches Americans" in a fundamentally different way than institutional news organizations.

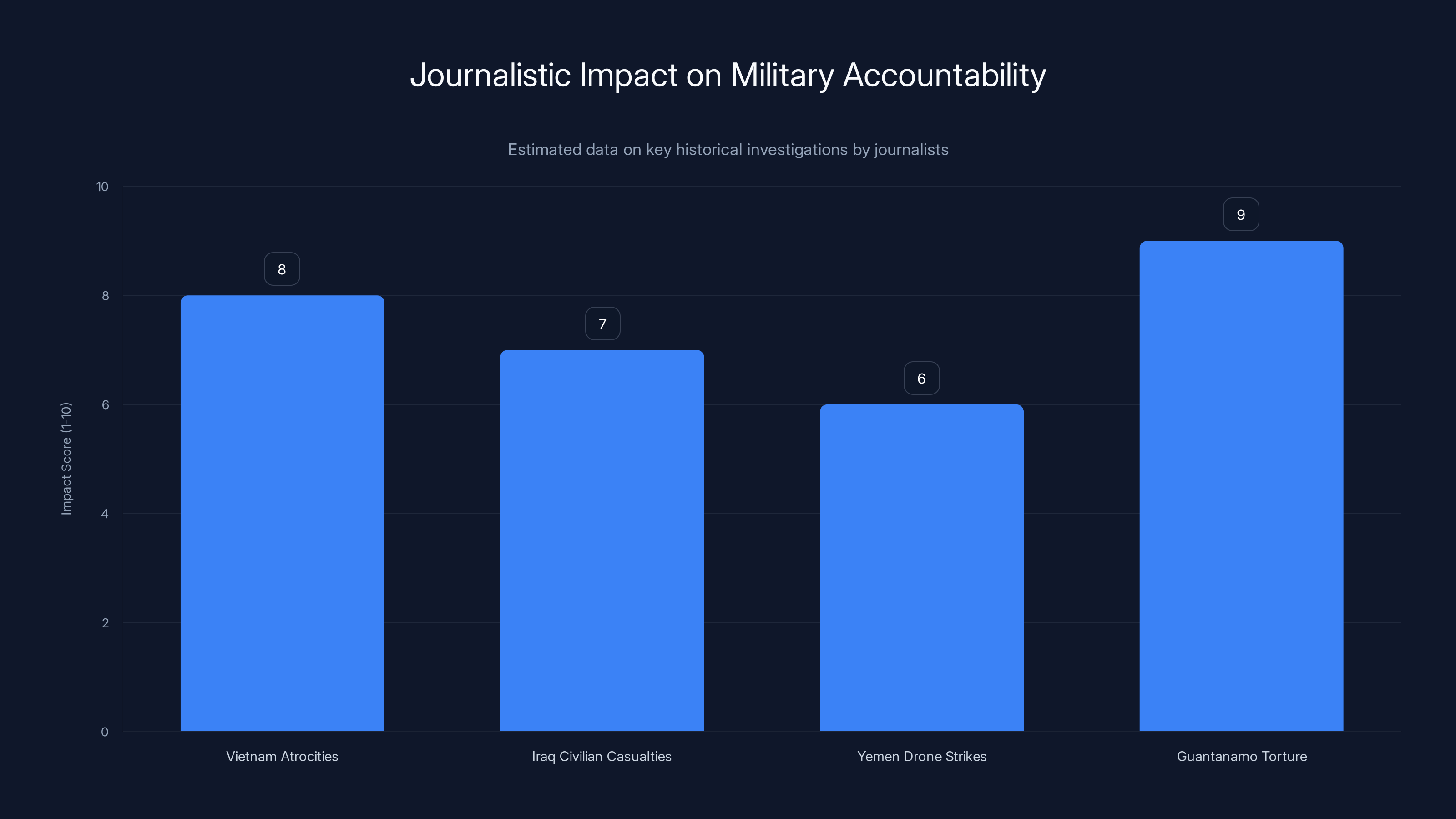

Estimated data suggests that journalistic investigations have had a significant impact on military accountability, with notable cases like Guantanamo torture scoring highest in impact.

The New Pentagon Press Corps: Who They Actually Are

Understanding who got credentials requires understanding the ecosystem that filled the void. These aren't alternative news outlets in the traditional sense. They're individual creators, political organizations, and influencers with specific ideological commitments.

Tim Pool represents one category: the independent political commentator with substantial reach. Pool has built an audience in the millions by producing commentary-heavy content that appeals to right-leaning viewers skeptical of mainstream institutions. His presence in the Pentagon press corps signals that the institution values reach over expertise in military affairs.

Turning Point USA members represent another category: politically organized groups with infrastructure but limited journalism experience. Turning Point USA is known primarily for college campus activism and political organizing, not defense reporting. Monica Paige, described as a reporter for the organization, uses her Turning Point credential to cover Pentagon operations—despite no demonstrated background in military journalism.

Then there are the individual creators. Cam Higby, a right-wing influencer with significant social media presence, received credentials. So did Lancevideos, another creator whose content typically blends politics with commentary rather than investigative reporting. Joey Mannarino, with over 650,000 followers on X (formerly Twitter), got access.

The common thread binding all of them isn't journalistic training. It's ideological alignment. These creators, when given access to military operations, don't ask the hard questions about why operations happen, whether they're legally justified, or what the actual outcomes are. Instead, they amplify the institutional narrative and attack those who question it.

This matters because credentialing confers legitimacy. When someone has official Pentagon press credentials, they appear in official briefing photos. They get listed as members of the press corps. Their questions are documented. The credential transforms them from commentators into something that looks, on the surface, like actual journalists.

The Venezuela Operation: What the New Press Corps Actually Covered

The real test of this system came almost immediately. In early 2025, Nicolás Maduro disappeared. Within hours, U. S. military involvement became clear—though the Pentagon's official statement was minimal. A major geopolitical event was unfolding in real time, and the Pentagon's newly credentialed press corps had access to official briefings and press materials.

So what did they report?

Virtually nothing substantive. Instead of investigating the operation, the credentialed influencers did what they were apparently designed to do: enforce messaging and attack skeptics.

Laura Loomer, a prominent right-wing personality, began crowdsourcing information about Pentagon press officials who might have leaked details to—of all outlets—the mainstream media. She was looking for leakers. Not sources. Not people with information to verify. Leakers who'd supposedly talked to journalists she disagreed with.

Cam Higby, one of the newly credentialed influencers, spent Saturday morning calling for better Pentagon public relations content. Not asking questions about the operation. Not reporting on its legality or justification. Asking for "a sick edit"—implying the Pentagon should produce more compelling propaganda-style social media content.

Monika Paige from Turning Point USA used the moment to attack the Biden administration, reposting a 2020 Joe Biden quote about Trump's admiration for dictators alongside an image of blindfolded Maduro. This wasn't reporting on the operation. This was using the operation as a political weapon to criticize a previous administration.

Joey Mannarino spent Sunday debating whether Vice President JD Vance or Marco Rubio should run for president in 2028. While a significant geopolitical operation was underway, one of the Pentagon's newly credentialed press members was discussing internal Republican politics.

Meanwhile, several of these credentialed influencers pivoted to covering alleged childcare fraud in Minnesota—the same story that a viral You Tube video had recently promoted. Local Minnesota outlets had actually been covering this story for years, but the Pentagon press corps was just discovering it, amplifying it, and presenting it as breaking news.

None of them reported anything substantive about the Venezuela operation. None received—or apparently sought—actual briefings about the military action. The Pentagon's new press corps wasn't investigating the story. It was performing loyalty.

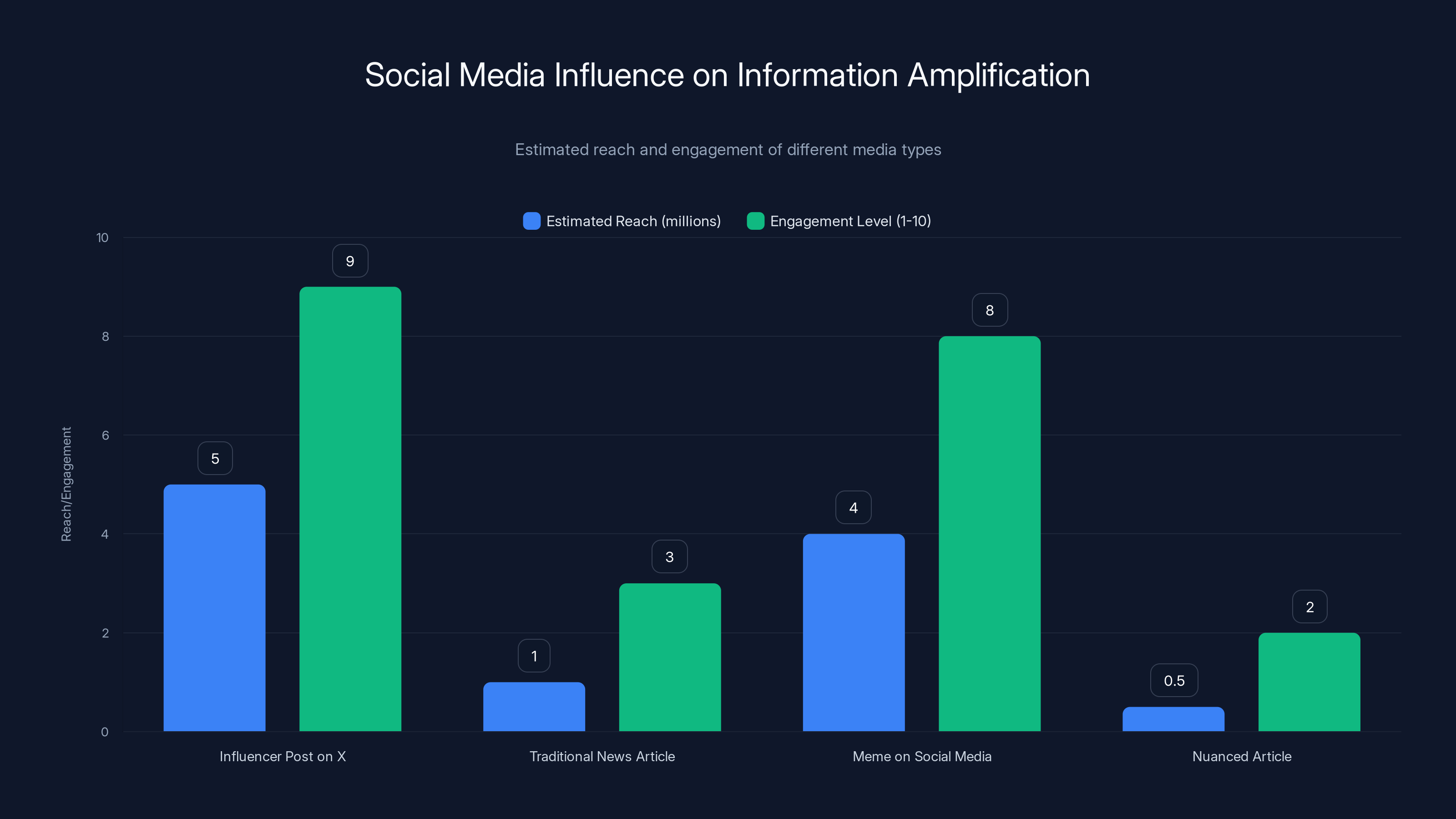

Influencer posts on platforms like X have a significantly higher reach and engagement compared to traditional news articles, driven by algorithmic amplification and direct audience access. Estimated data.

The Iraq War Playbook: How This Happened Before

This moment feels grimly familiar if you remember the early 2000s. When the United States invaded Iraq, a different information ecosystem existed, but the mechanics were strikingly similar.

During the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the Iraq invasion, pro-war bloggers built massive audiences by doing exactly what the Pentagon's new press corps is doing now. They attacked mainstream journalists who questioned the war. They promoted government narratives without scrutiny. They positioned themselves as alternative voices to corrupt institutions—all while enforcing strict loyalty to the military operation itself.

These early-2000s "warbloggers," as they became known, built entire platforms on attacking writers who expressed skepticism about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction claims, the legal justification for invasion, or the strategic wisdom of the operation. Mainstream reporters who asked tough questions were painted as unpatriotic, biased, or part of some establishment conspiracy.

The warbloggers didn't just comment on news. They attempted to control the information environment itself. When mainstream outlets reported information critical of the war, warbloggers mobilized their audiences to attack those outlets, their reporters, and their credibility.

What made this effective wasn't the warbloggers' journalism. It was their audience size and their willingness to weaponize that audience against skeptics. They didn't need to be right. They needed to be loud enough that doubt became unfashionable in certain circles.

The Pentagon's new press corps operates under similar logic. When Lancevideos, one of the newly credentialed influencers, called congressional critic Thomas Massie a "libtard" for questioning the Venezuela operation, he wasn't engaging in journalism. He was enforcing narrative loyalty through social pressure. When he wrote "Could Iran be next? USA kidnapping spree must continue," he wasn't reporting. He was amplifying an institutional position while attacking those who might question it.

Historians and media analysts have extensively documented how this early-2000s information environment degraded public understanding of the Iraq War. The ability to ask critical questions atrophied. Dissent became associated with unpatriotic behavior. The mainstream outlets that did ask tough questions—and got the story wrong despite their questions—became targets for attacks that overshadowed their actual reporting.

The pattern is repeating with different technology and different political figures, but the underlying mechanism is identical: replace accountability-focused journalism with ideology-focused commentary, then use scale and coordination to enforce narrative discipline.

What "Reaching Americans" Actually Means

When Kingsley Wilson said the Pentagon was welcoming outlets that "reach Americans," he wasn't making a statement about audience size alone. He was articulating a specific vision of what the Pentagon wants from its information operation.

Traditional news organizations reach Americans through institutional platforms. They have editorial standards, correction policies, and—theoretically—institutional accountability. If a reporter gets something wrong, the newsroom has mechanisms to address it. If an editor makes a call that seems biased, there's a process for appeal.

The influencers the Pentagon credentialed reach Americans through algorithmically amplified content, parasocial relationships, and direct engagement. Tim Pool's millions of followers follow him because they trust his judgment and worldview, not because they trust an institution. When Pool presents Pentagon information, his audience receives it filtered through his credibility and perspective.

This creates a specific advantage for institutional messaging: the filter appears to be individual rather than institutional. When The New York Times reports something, readers understand an institution is communicating. When Tim Pool reports something from Pentagon briefings, his audience may perceive it as an individual's independent assessment—even if it's directly from official briefings.

The Pentagon essentially gets to delegate messaging to people whose audiences trust them as individuals. This is far more effective than traditional press releases or official statements, which audiences expect to be self-serving.

Moreover, these creators are incentivized to amplify rather than question. Their audiences don't follow them for accountability journalism. They follow them for political commentary that aligns with existing beliefs. Asking hard questions about whether a military operation is legal or wise would alienate the audience that these creators depend on.

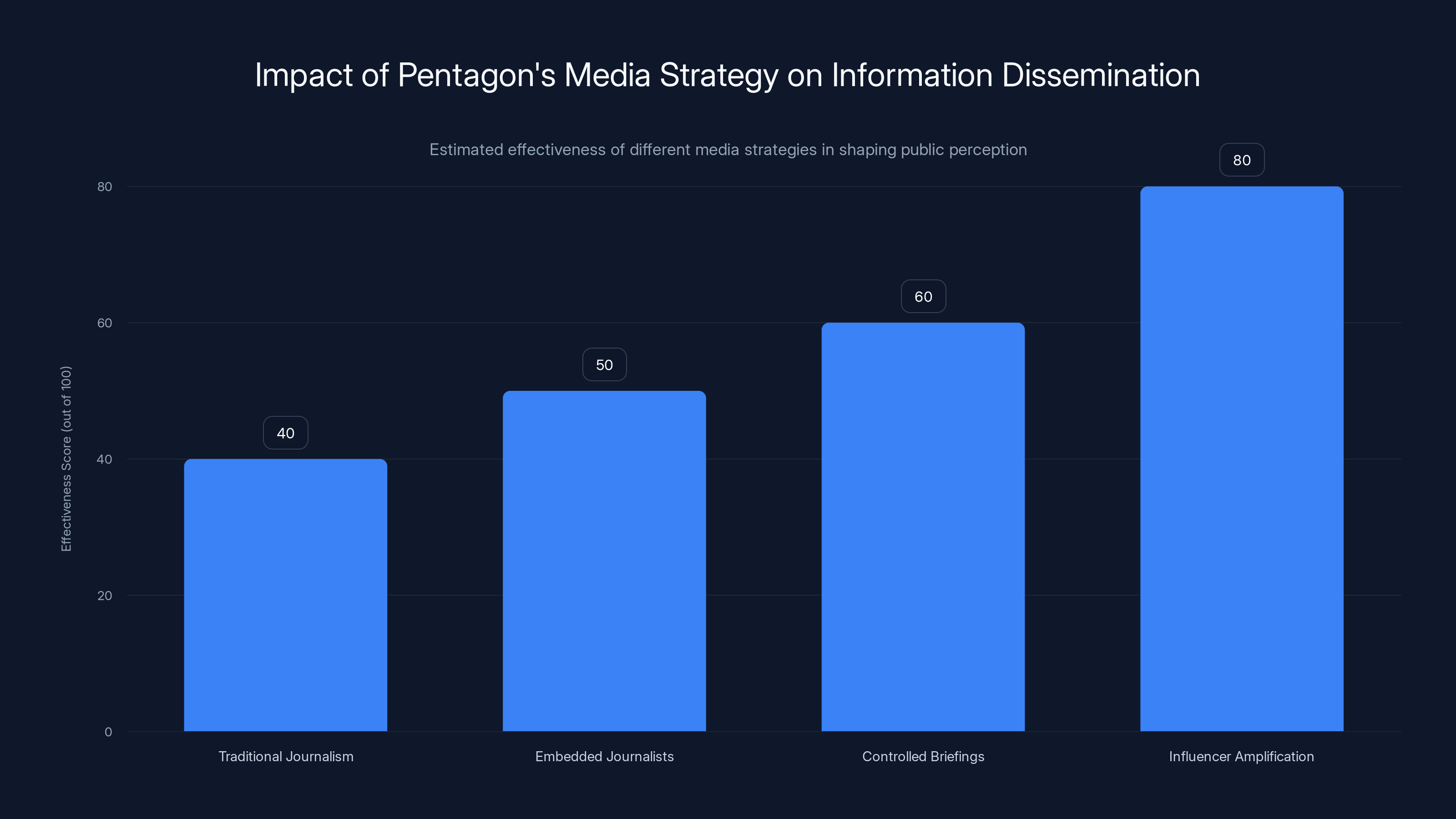

Influencer amplification is estimated to be the most effective strategy for shaping public perception, surpassing traditional methods. Estimated data.

The Absence of Actual Reporting

The most striking aspect of the new Pentagon press corps's coverage of the Venezuela operation is what's missing: actual reporting.

No one asked basic questions. No one requested official justification for the operation. No one investigated the legal basis. No one reported on outcomes, casualties, or strategic objectives. The newly credentialed influencers had access to the Pentagon—ostensibly to report on military operations—and used that access to produce memes and political commentary.

This is revealing because it demonstrates the true function of this restructuring. It's not about creating new avenues for information to flow to the public. It's about creating new mechanisms for controlling which information flows and how.

A working press corps exists to surface information the institution prefers to keep hidden. It asks uncomfortable questions. It investigates claims that officials make. It serves the public by trying to understand what powerful institutions are actually doing behind the scenes.

The Pentagon's new press corps does the opposite. It takes what the institution wants public and amplifies it. It attacks people who ask the uncomfortable questions that departing mainstream journalists might have asked.

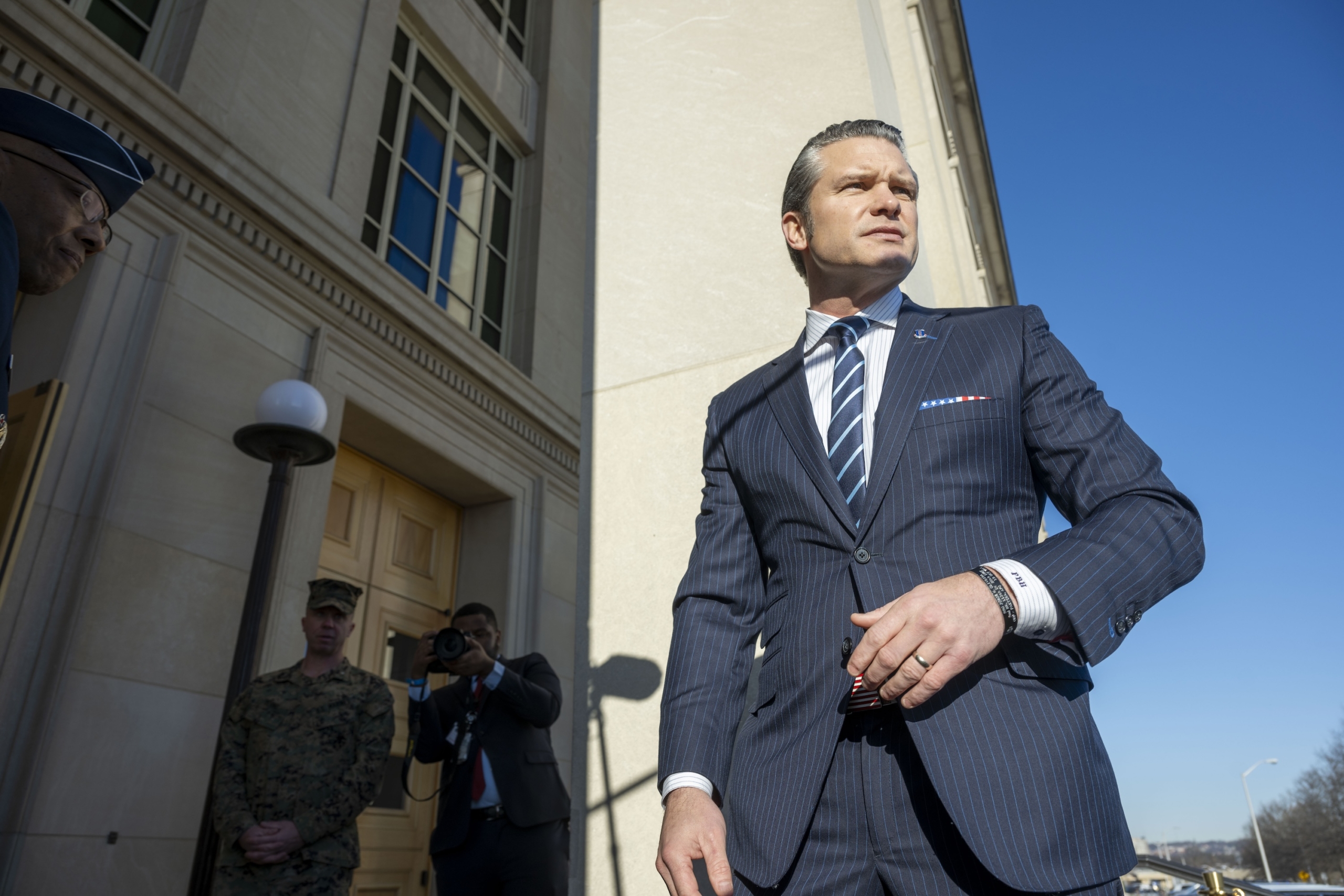

When Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth launched the "Arsenal of Freedom Tour" in late January 2025, only one mainstream outlet accompanied him: CNN. The rest were right-wing media figures, including John Konrad, who was overheard trying to get Hegseth to autograph a book he'd authored. This wasn't a press tour. This was a publicity tour with messaging allies.

The handful of mainstream journalists who did participate weren't there as skeptical observers. They were part of an orchestrated image-building exercise.

Information Control in the Digital Age

What the Pentagon has effectively done is implement a form of information control specifically designed for the digital media landscape. It's not censorship in the traditional sense. It's channel management.

Traditional press restrictions were obvious. You couldn't access something, so you reported on something else or criticized the restriction itself. The Pentagon's new system is subtler. It grants access to creators who won't use it to scrutinize power. It creates an appearance of press freedom—there's still a press corps, there are still briefings—while ensuring that the press corps lacks the incentive or infrastructure to do investigative work.

Moreover, the system leverages the scale of digital platforms. When a right-wing influencer with millions of followers posts content from Pentagon briefings, that content reaches far more people than a traditional news article would. The Pentagon gets unprecedented distribution for its message, filtered through figures its target audience already trusts.

This is asymmetrical in a crucial way. Mainstream outlets that remain outside the system can report on Pentagon operations, but they do so at a disadvantage. They don't have access to the same briefings. They can't claim to be "at the briefing." Meanwhile, credentialed influencers can present official information with the implicit credibility that comes with being inside.

The strategy essentially weaponizes the fragmentation of the media landscape. In an era where people get news from dozens of sources, the Pentagon identified the sources most aligned with its institutional interests and gave them preferential access. Those sources then amplify Pentagon messaging to their specific audiences, creating the appearance of diverse coverage while actually narrowing the range of acceptable perspectives.

Technologist and writer Charlie Warzel has described similar dynamics in other institutional contexts, noting how algorithmic amplification and audience fragmentation make coordinated messaging strategies far more effective than they were in previous eras. A unified message, distributed through multiple trusted voices to segmented audiences, creates perception of consensus even when actual consensus is manufactured.

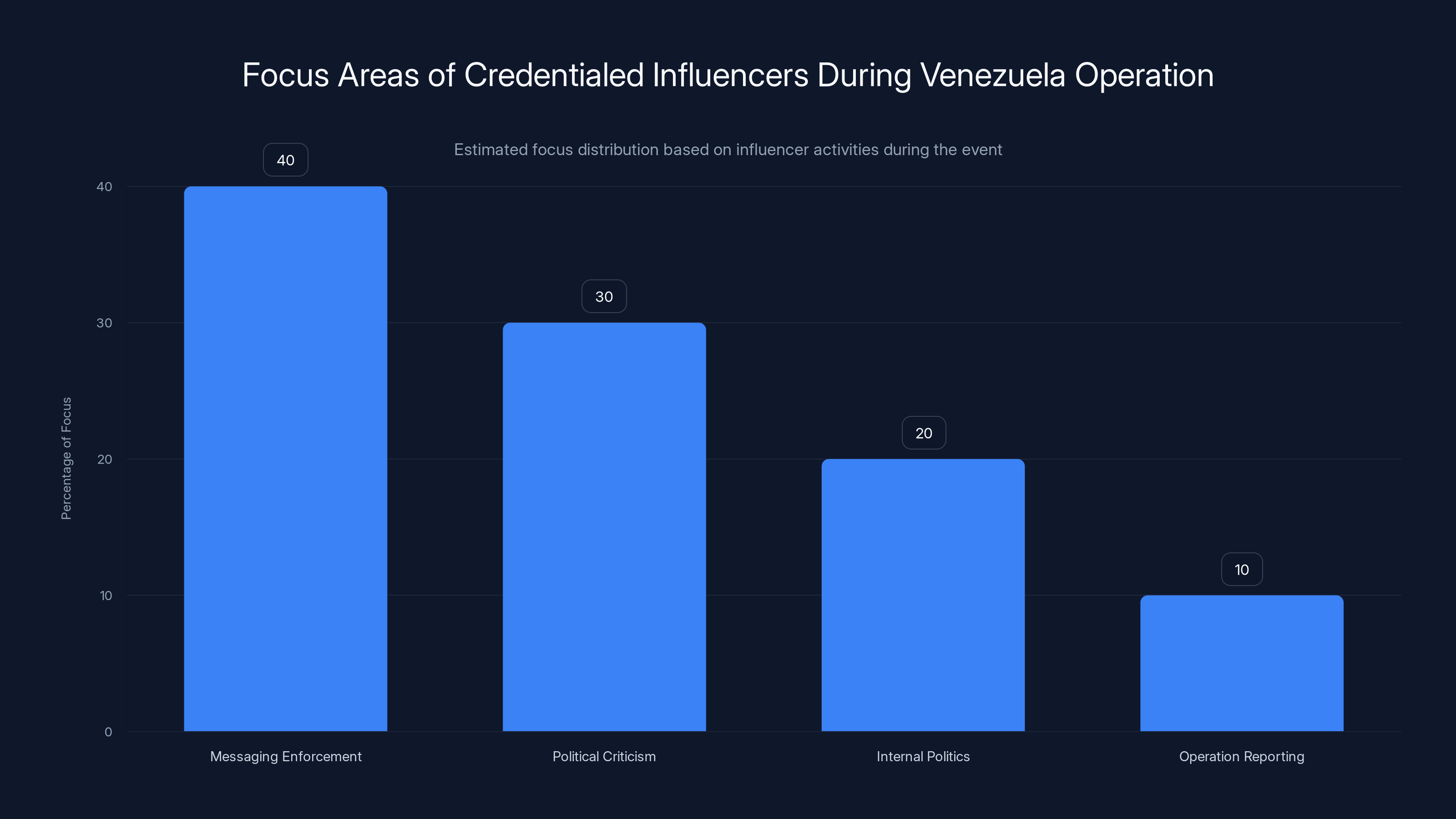

Estimated data suggests that credentialed influencers focused more on enforcing messaging and political criticism than on substantive reporting of the Venezuela operation.

The Broader Implications for Military Accountability

The immediate Venezuela coverage is concerning enough. But the longer-term implications for military accountability are potentially more serious.

Throughout American history, the military's relationship with the press has been contentious but essential. Journalists embedded with troops in Vietnam reported atrocities that military officials wanted hidden. Reporters at major outlets investigated civilian casualties in Iraq, drone strikes in Yemen, and torture at Guantanamo Bay. None of this reporting was easy or welcome. But it happened because journalists had access and incentive to investigate.

When those journalists left the Pentagon building, that investigative capacity left with them. The new press corps doesn't have the training to investigate military operations. It doesn't have the editorial infrastructure to verify claims. It doesn't have the professional incentive to ask hard questions.

Moreover, if this model proves successful in controlling Pentagon messaging, it's likely to spread. Other institutions have watched how the military managed to replace skeptical journalists with ideological allies. The State Department might consider similar policies. Agencies with controversial operations might see the Pentagon as having cracked the code for message control.

The implications extend beyond government, too. If major institutions can successfully replace institutional press with ideologically aligned commentators, the entire concept of public accountability through journalism becomes degraded. It's replaced by something that looks like press coverage but functions more like marketing.

Credentialing as a Tool of Narrative Control

The mechanics of credentialing matter more than they might appear. A credential isn't just access. It's legitimation. It's a signal that says "this person is authorized to speak about this institution's affairs."

When major news organizations had Pentagon credentials, their reporters' presence at briefings carried institutional weight. Editorial boards stood behind reporting. Correction processes existed. Legal teams reviewed claims before publication. The credential came with infrastructure that implied accountability.

The new credentialed influencers lack this infrastructure. They answer to no one but their audience and their own judgment. If they report something incorrect, there's no correction process. If they make inflammatory statements while credentialed, there's no editorial review. The credential grants authority without any corresponding accountability.

This transforms the credential from a symbol of access into a symbol of allegiance. The Pentagon is essentially saying: "We trust you because we know you won't scrutinize us. Here's the credential to prove it."

Historically, authoritarian governments have used similar tactics. They'll credential friendly media while blocking independent outlets. The friendly media gets access, prestige, and official support. The independent media gets marginalized. Over time, the public's perception shifts. The credentialed outlets become "real" media while independent outlets become "alternative" or "biased."

America's military isn't an authoritarian government, but it's an institution with enormous power and a vested interest in controlling its public image. The tools available to it have evolved. The Pentagon can't formally bar independent journalism, but it can restructure access in ways that incentivize the kind of coverage it wants while making skeptical reporting harder.

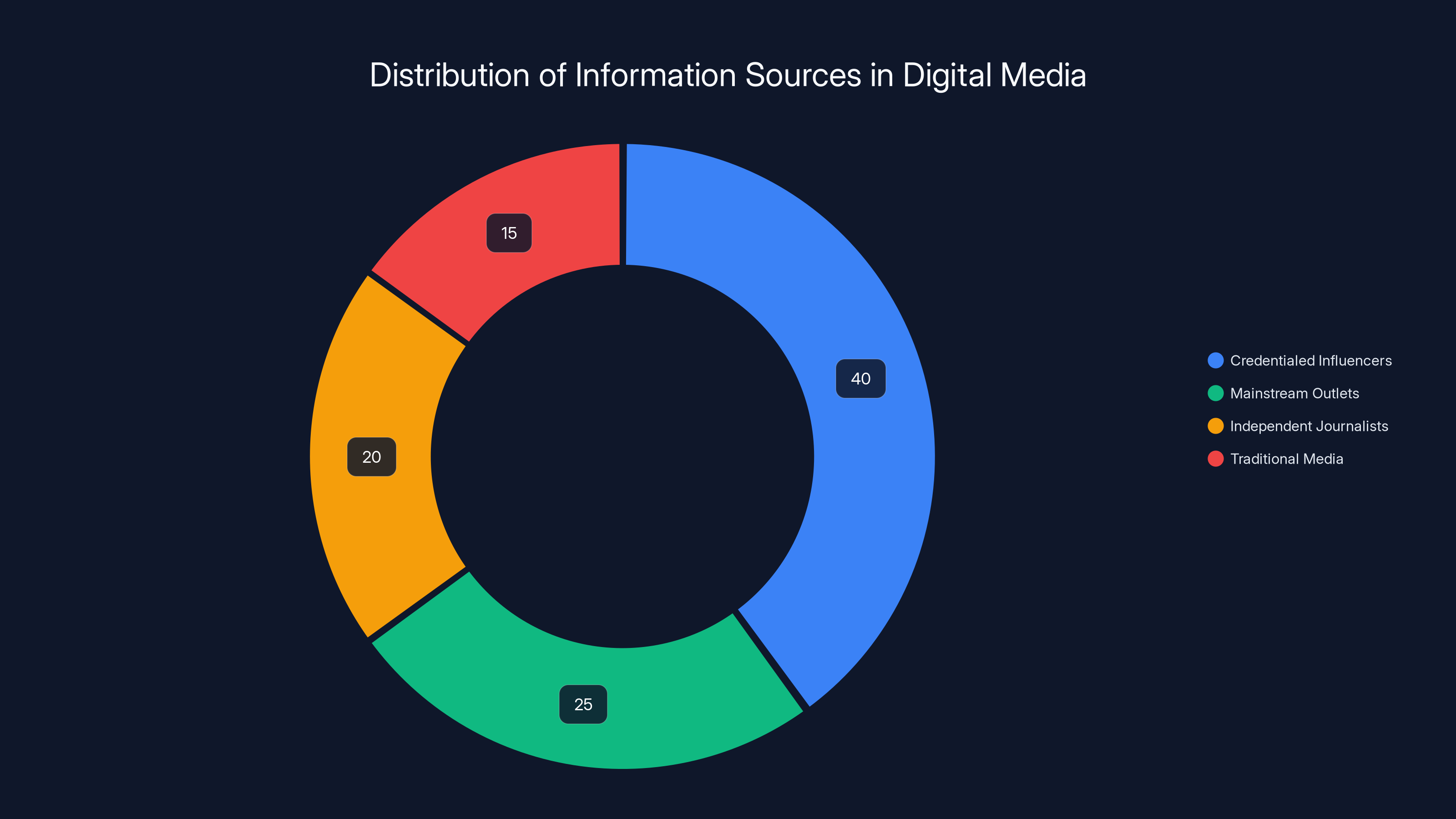

The Pentagon's strategy focuses on credentialed influencers, who receive 40% of the information access, to control narratives in the digital age. Estimated data.

What Happened to the Mainstream Pentagon Reporters

The journalists who left the Pentagon didn't disappear. But they're operating at a disadvantage compared to their credentialed counterparts.

When CBS's Pentagon correspondent left, the network didn't fold its defense reporting. But CBS reporters trying to cover Pentagon stories now do so without official access to briefings. They can file FOIA requests, request comments from official spokespeople, and try to develop sources within the institution. But they're not sitting in the briefing room anymore.

This matters tactically. When a story breaks, having someone already in the building who can immediately get official comment or clarification is valuable. Being locked out means chasing the story from the outside, always a step behind the official narrative.

Moreover, the departure of mainstream outlets created a narrative problem for those outlets. They pulled out because they believed the policy was unfair and restrictive. But to the general public, it might look like they chose to leave rather than adapt. The Pentagon's framing—that legacy media "self-deported"—influences public perception of why mainstream journalists aren't at briefings anymore.

The journalists who left also lost the implicit credibility that comes from being part of the official press corps. When a reporter is listed as part of the Pentagon press corps, their reporting carries a certain authority. They had access. They were inside. Once they're outside, their reporting might seem more adversarial, more prone to bias, even if it's actually more skeptical and accurate.

This is a subtle but powerful advantage for the credentialed influencers. Their reporting will be perceived as insider information because they literally have insider access. Reporting from outside journalists will be perceived as criticizing from the margins.

The Role of Social Media in Amplification

None of this would work without social media. The Pentagon's new strategy is fundamentally dependent on platforms like X (formerly Twitter), where influencers can reach millions with a single post.

When the credentialed influencers post about Pentagon operations, their content gets algorithmically amplified to their followers. A post from Tim Pool about the Venezuela operation reaches millions of people within hours. A traditional news article requires readers to navigate to a website, and its reach is limited by the outlet's subscriber base and news aggregator placement.

The Pentagon doesn't have to force anything. It simply grants credentials to people whose content performs well on social platforms, knowing that those people will amplify Pentagon-adjacent messaging to massive audiences.

Social media algorithms also reward engagement, which means conflict and strong opinions outperform nuance. A nuanced exploration of whether a military operation was legally justified doesn't generate as much engagement as a meme mocking congressional skeptics. The incentive structure of social platforms pushes credentialed influencers toward the kind of coverage the Pentagon wants—emotionally resonant, ideologically aligned, and lacking in critical scrutiny.

Moreover, social media has created a direct line from creators to their audiences that bypasses institutional gatekeepers entirely. When a New York Times reporter publishes something, editors review it first. When an influencer posts on X, it goes live immediately. The Pentagon's credentialing strategy essentially bypasses all the institutional safeguards that traditionally constrained military messaging.

This creates an information asymmetry. The military can reach the public instantly through ideologically aligned creators. Mainstream outlets trying to report critically on military operations have to navigate institutional processes and compete in an attention economy where their more nuanced reporting loses out to the viral memes and hot takes of the credentialed influencers.

Lessons From Previous Military-Media Conflicts

The Pentagon's new approach isn't unprecedented, but previous attempts have generally not worked out well for military institutions.

During the Vietnam War, the military attempted to control media coverage through official channels. Reporters were embedded with troops, but they had enough freedom to report what they actually saw, including atrocities and strategic failures. When the Tet Offensive happened and the military's official narrative proved false, it was journalists reporting from the field that revealed the reality. The military lost control of the narrative because it couldn't prevent journalists from actually investigating.

The military learned from this. After Vietnam, it implemented the pool system during operations like the Gulf War, where journalists were carefully managed through official military handlers. Reporters had access, but limited access, and under controlled conditions. This worked somewhat, but it also created skepticism among journalists about the information they were receiving. Many reported that they were being managed, which itself became a story.

Later operations in Afghanistan and Iraq involved embedded journalists with various degrees of freedom. These embeddings produced reporting that was sometimes favorable to the military and sometimes critical. The military got some of the favorable coverage it wanted, but it couldn't prevent critical reporting entirely.

The Pentagon's new approach is different. Rather than managing journalists, it's replacing them with non-journalists. Rather than restricting access, it's granting exclusive access to allies. Rather than attempting to control narrative through official channels, it's using social media influencers to create alternative narratives.

Historically, this strategy has been most effective in the short term but has often backfired over time. When institutions rely on ideological allies rather than skeptical journalists, they lose the ability to correct their own mistakes. They build echo chambers that reinforce institutional assumptions even when those assumptions are wrong.

The Iraq War provides the clearest example. The warbloggers of the early 2000s successfully promoted the invasion through their alternative media channels. But they also prevented the kind of scrutiny that might have identified problems with the military's initial plans or strategic assumptions. By the time skepticism emerged, thousands of people had died and trillions of dollars had been spent.

A press corps that actually investigated the pretexts for war, interrogated strategic assumptions, and reported honestly on the challenges of occupation might have prevented some of that carnage. Instead, the public got amplified propaganda from ideological allies who lacked the tools or incentive to scrutinize power.

What Accountability Looks Like in a Post-Credential Era

If mainstream journalists can't access the Pentagon, and ideological influencers won't scrutinize it, where does accountability come from?

Potentially from Congress, though Congress has its own incentive problems. Members of Congress with military committees have relationships with defense contractors and constituents who work in defense industries. Aggressive oversight can be politically costly.

Potentially from whistleblowers, though whistleblowers risk their careers and face legal jeopardy. Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden both revealed classified information about military operations. Both faced serious legal consequences. The system doesn't protect people who leak information to journalists—in fact, it punishes them.

Potentially from overseas journalists and human rights organizations. International outlets and NGOs can investigate American military operations without needing Pentagon credentials. Their reporting is often more critical and detailed than American outlets produce. But their reach within the United States is limited.

Potentially from within the military itself. Some officers and enlisted personnel will speak to journalists, even without Pentagon credentials. These military insiders can describe what actually happened on the ground. But they're limited by their own access and the risk they take by speaking out.

None of these alternatives are as effective as a strong independent press with institutional resources and legal support to investigate powerful institutions. Which is precisely why the Pentagon restructured its press credentialing system. By removing the institutional press, it eliminated the most significant accountability mechanism available.

The Future of Military-Media Relations

If the Pentagon's new strategy proves successful in controlling messaging, we should expect to see similar approaches adopted by other institutions.

The State Department might credential ideologically aligned influencers to amplify its foreign policy messaging. Intelligence agencies might use similar tactics to shape public understanding of surveillance operations. Agencies with controversial programs might replace skeptical journalists with friendly commentators.

Over time, this could fundamentally degrade the role of an independent press in American democracy. If major institutions can effectively bypass institutional journalism and communicate directly to the public through ideologically aligned creators, the press's watchdog function atrophies.

This doesn't necessarily mean the press disappears. But its function changes from accountability to amplification. Rather than investigating power, it becomes a tool that power uses to reach the public.

There are countervailing forces, though. Journalists who lose access to institutions don't stop trying to report on those institutions. Freedom of information requests, congressional sources, leaked documents, and international reporting can all substitute for direct access. It's harder, slower, and less immediately impactful. But it's possible.

Moreover, the public's understanding of media incentives is gradually improving. The more people understand that influencers are incentivized to amplify rather than scrutinize, the more skeptical they might become of influencer commentary on institutional operations. A credentialed influencer might have more apparent access than a non-credentialed journalist, but the infrastructure for skepticism might develop to counteract that appearance.

There's also the possibility that this strategy backfires. If the credentialed influencers completely fail to investigate actual wrongdoing—if military operations cause problems that should have been reported on but weren't because the press was too busy making memes—the public might eventually lose trust in both the military and the influencers who failed to scrutinize it.

History suggests that information systems built on propaganda rather than accountability tend to be brittle. They work well until they don't, and when they fail, they fail completely. The early-2000s warbloggers seemed powerful and convincing until the Iraq War's problems became undeniable. At that point, their credibility collapsed and the institutions they'd defended looked worse for having hidden the truth.

The Pentagon's new press corps might face similar dynamics. Right now, the Venezuela operation is relatively simple to message. But military operations rarely stay simple. When complications emerge, when casualties mount, when strategic assumptions prove wrong, the credentialed influencers will face a choice: continue amplifying the military's narrative despite evidence of problems, or start investigating honestly and risk losing their credentials and the access that defined their relevance.

Most will choose the former. Which means that when the real accountability eventually arrives—through congressional investigations, through international scrutiny, through leaked documents—the public will understand that the credentialed press corps was complicit in hiding the truth.

FAQ

Why did the Pentagon ban traditional journalists from its press corps?

The Pentagon didn't formally ban traditional journalists, but it implemented access restrictions that made coverage difficult. Journalists couldn't access non-public information unless the Pentagon released it officially. Major outlets found these restrictions too limiting and pulled their reporters out. The Pentagon then characterized this as media "self-deporting" rather than acknowledging its own policy changes drove them away.

What makes the new credentialed influencers different from traditional Pentagon reporters?

Traditional Pentagon reporters had training in military affairs, institutional editorial oversight, and professional standards for fact-checking and correction. The new credentialed influencers are political commentators without military journalism background or institutional accountability mechanisms. Their audiences follow them for political commentary, not investigative reporting, so they're incentivized to amplify rather than scrutinize.

Did the influencer press corps report on the Venezuela operation?

No. Despite having access to Pentagon briefings about a major military operation, the credentialed influencers produced no substantive reporting. Instead, they created memes supporting the operation, attacked congressional skeptics, discussed unrelated stories, and debated future presidential races. The absence of reporting demonstrates that access to information is not the same as commitment to investigating that information.

How is this similar to Iraq War-era coverage?

During the early 2000s, pro-war bloggers built audiences by attacking skeptical mainstream journalists while amplifying military narratives. The Pentagon's new strategy uses similar mechanics: replace skeptical journalists with ideology-aligned commentators, grant those commentators official access and credibility, and rely on them to amplify rather than scrutinize. The result is an information environment where critical perspectives become marginalized.

What alternatives exist for Pentagon accountability if traditional journalists can't access the institution?

Accountability can come from Congress through oversight hearings, from whistleblowers and military insiders willing to speak to journalists, from international media outlets, from freedom of information requests, and from leaked documents. However, none of these are as effective as a robust institutional press with dedicated military beat reporters and resources to investigate operations. This is precisely why institutions prefer to control press access rather than face skeptical questioning.

Could this credentialing strategy spread to other government agencies?

Yes. If the Pentagon's approach successfully controls messaging without direct censorship, other agencies with controversial operations—State Department, intelligence agencies, defense contractors—might adopt similar strategies. This would gradually erode the press's ability to investigate powerful institutions across government, fundamentally changing how accountability functions in American democracy.

What happens when the credentialed influencers are faced with evidence of military wrongdoing?

They'll likely continue amplifying the military's narrative rather than reporting honestly, because their relevance and access depends on institutional favor. This creates a brittle information system that works well until it doesn't. When problems eventually emerge through other sources—congressional investigations, international reporting, leaked documents—the public learns that the credentialed press was complicit in hiding the truth, destroying their credibility and making the institution look worse.

Why does credentialing matter more than actual access?

Credentialing confers legitimacy and authority. A credentialed influencer appears as part of the official information environment even if their coverage is less rigorous than non-credentialed journalists. The credential signals that someone is authorized to speak about an institution, which amplifies their perceived credibility with audiences. This appearance of official sanction is often more valuable than the actual access the credential provides.

Conclusion: When Institutions Replace Accountability With Allegiance

The Pentagon's restructuring of its press corps represents a crucial inflection point in how American institutions manage public information. It's not the first time the military has attempted to control its narrative. But it might be the most successful.

Previous approaches—embedding journalists, managing access, holding controlled briefings—attempted to work within the framework of a free press. The Pentagon's new strategy bypasses that framework entirely. Rather than trying to convince skeptical journalists that military operations are justified, it eliminates skeptical journalists and replaces them with people who won't ask hard questions.

This is effective in the short term. The Pentagon gets amplification for its messaging through creators with massive audiences. Those creators reach people who might not consume traditional news. The military's narrative propagates through ideologically aligned channels faster and more extensively than it would through institutional journalism.

But the long-term implications are troubling. When institutions successfully replace accountability with allegiance, democratic oversight becomes difficult. When the public can't rely on journalists to scrutinize power, accountability mechanisms degrade. When information systems are built on propaganda rather than investigation, they become brittle and prone to catastrophic failure.

The Venezuela operation will eventually become history. But the credentialing structure the Pentagon created is likely to persist. Subsequent military operations will be covered by this same press corps. Congressional critics will be attacked by credentialed influencers. Official narratives will propagate through social media while critical voices struggle for attention and access.

At some point—when military operations fail, when casualty figures emerge, when strategic assumptions prove wrong—the public might ask why credentialed journalists failed to investigate. The answer will be clear: they weren't credentialed to investigate. They were credentialed to amplify.

And by then, the institutions that benefited from this arrangement will have moved on to the next operation, the next narrative, the next effort to control what the public knows about how power is actually exercised.

The difference between this moment and previous eras isn't technology. It's not even the sophistication of propaganda. It's the wholesale replacement of an institution designed to question power with an institution designed to serve it. The Pentagon didn't invent this approach. But it might have perfected it.

For democracy to function, this needs to change. Institutions need skeptical oversight. The public needs access to information from sources committed to investigation rather than amplification. And journalists need the access and protection necessary to do the work that institutions like the Pentagon would prefer to keep hidden.

When those conditions disappear, what replaces them isn't a functional alternative. It's something that looks like accountability but functions as propaganda. And that distinction might be the most important story the Pentagon's new press corps will never report.

Key Takeaways

- Pentagon restructured press credentialing in November 2024, implementing restrictions that forced mainstream journalists to leave, replaced by right-wing influencers and political commentators

- New credentialed press corps failed to report any substantive information about Venezuela operation, instead producing memes and political commentary while attacking congressional skeptics

- Strategy mirrors Iraq War-era warblogger tactics that used ideological alignment to enforce narrative discipline and attack skeptical journalists

- Influencers lack institutional accountability mechanisms, editorial oversight, and professional incentive to investigate—they're positioned to amplify rather than scrutinize

- When institutions replace accountability-focused journalism with ideology-aligned commentary, they create brittle information systems vulnerable to catastrophic failure when problems eventually emerge

Related Articles

- WhatsApp Group Chats: Member Tags, Text Stickers & Event Reminders [2025]

- Nasal Saline Rinse for Cold Prevention: Ancient Ayurvedic Remedy Proven by Modern Science [2025]

- RFK Jr.'s Dead Bear Incident: What Public Records Actually Reveal [2025]

- Linux Distros vs Windows 11: Why Developers Are Switching [2025]

- Breville Luxe Brewer Review [2025]: Premium Drip Coffee Maker

- Switchbot's Onero H1 Laundry Robot: The Future of Home Automation [2025]

![Pentagon's Influencer Press Corps Replaces Journalists: The Venezuela Test [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/pentagon-s-influencer-press-corps-replaces-journalists-the-v/image-1-1767804034208.jpg)