Introduction: The New Frontier of Robotic Intelligence

When Lachy Groom walked into Physical Intelligence's San Francisco headquarters for the first time, the experience was nothing like the gleaming tech campuses most entrepreneurs showcase to investors. Instead of polished presentations and carefully choreographed demonstrations, he found himself in a concrete warehouse filled with robotic arms in various states of experimentation. One struggled with folding black pants. Another attempted to turn a shirt inside out with mechanical determination. A third peeled zucchini with surprising competence. This wasn't theater—it was the grinding, iterative work of building foundational artificial intelligence systems for physical machines.

Physical Intelligence represents a fundamental shift in how the technology industry approaches robotics. Rather than building robots designed for single, specific tasks, the company is developing generative AI models trained on robotics data that can teach machines to understand and execute a wide range of physical tasks. It's a "Chat GPT for robots" moment, and it's happening in real time across dozens of test stations, warehouses, and makeshift laboratories across the United States.

The company was founded by an exceptional team: Sergey Levine, an associate professor at UC Berkeley specializing in robotic learning; Chelsea Finn, who runs the learning lab at Stanford; and Karol Hausman, a Google Deep Mind researcher with teaching experience at Stanford. But it's Lachy Groom—a former Stripe employee and successful angel investor in companies like Figma, Notion, and Ramp—who brought the startup vision to life by recruiting this world-class team and securing the resources to build infrastructure at scale.

The timing couldn't be more critical. Manufacturing and logistics companies face unprecedented labor shortages. Warehouse automation is becoming essential rather than optional. Healthcare facilities struggle to find adequate staffing. Consumer applications for home robotics remain largely unfulfilled promises. Physical Intelligence's approach—building intelligence that generalizes across tasks—could unlock solutions to all these problems simultaneously.

This comprehensive guide explores what Physical Intelligence is building, how their approach differs from traditional robotics, the technical foundations that make their work possible, and what it means for enterprises considering robotic automation. We'll examine the practical applications already emerging, the timeline for commercial deployment, and how organizations should prepare for a future where robots become flexible, adaptable agents capable of learning new tasks through shared intelligence.

Understanding Physical Intelligence's Core Technology

Foundation Models for the Physical World

The central innovation at Physical Intelligence is the application of large foundation models to robotics. For nearly a decade, the AI industry has watched foundation models—models trained on enormous amounts of diverse data that can then be adapted for specific tasks—transform software development. GPT-4 can help with coding, content creation, analysis, and a thousand other tasks because it was trained on diverse internet data. Stable Diffusion can generate images across countless styles because it learned from billions of image examples.

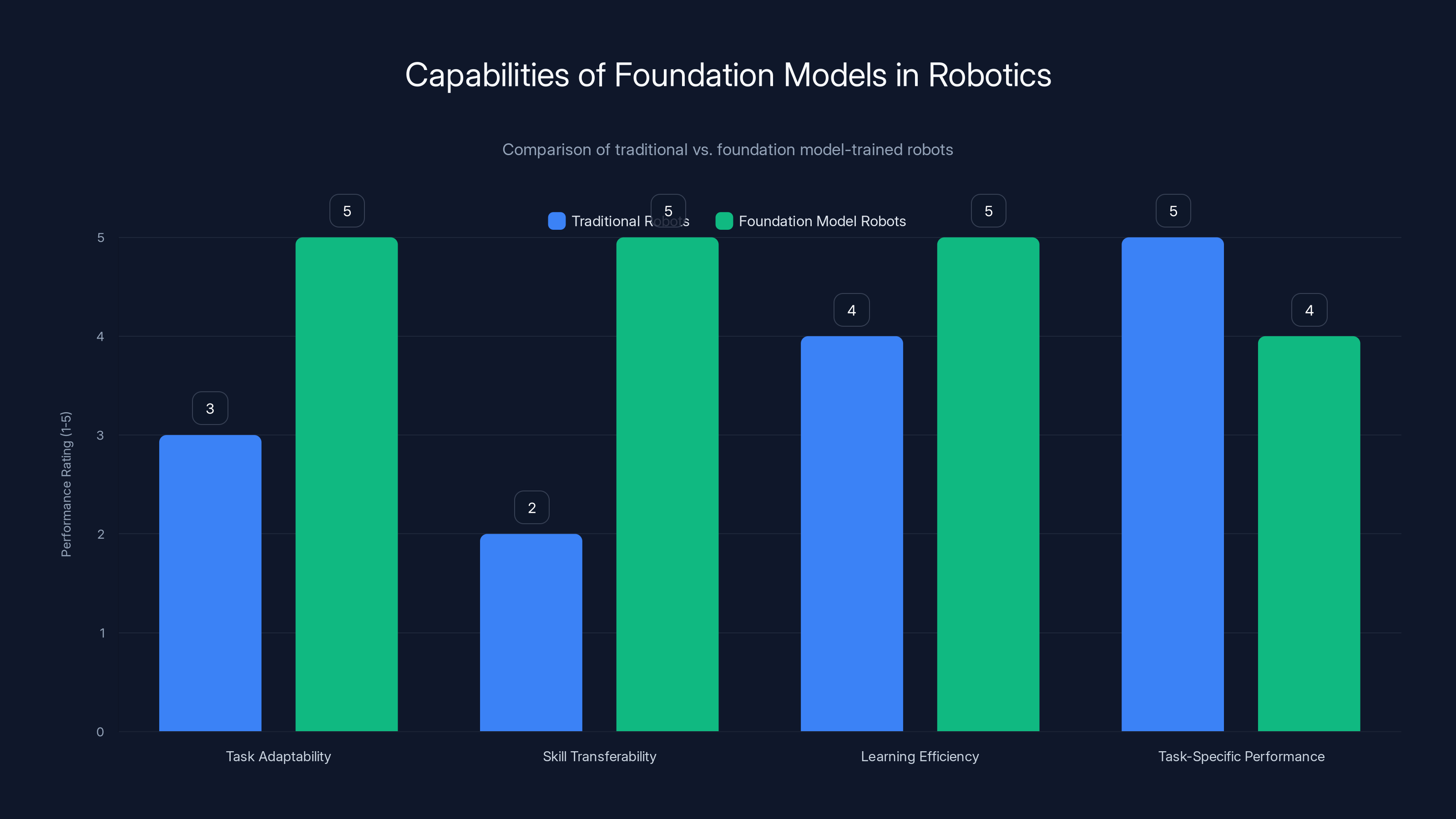

Physical Intelligence is translating this approach to the physical world. Instead of training separate specialized neural networks for each robotic task, they're building generalized models that learn the fundamental principles of physics, object manipulation, force application, and motor control. When you show such a model examples of how to fold different types of fabric, it can generalize those learnings to fold new materials it's never encountered. When it learns to grasp objects of varying shapes and textures, it develops transferable skills applicable to entirely different objects.

This approach has profound implications. A robot trained on traditional methods to stack boxes cannot suddenly become effective at picking tomatoes. A robot trained using Physical Intelligence's foundation models, having learned the underlying principles of grasping and manipulation, could adapt much more readily to new tasks. The intelligence is portable and composable rather than task-specific and brittle.

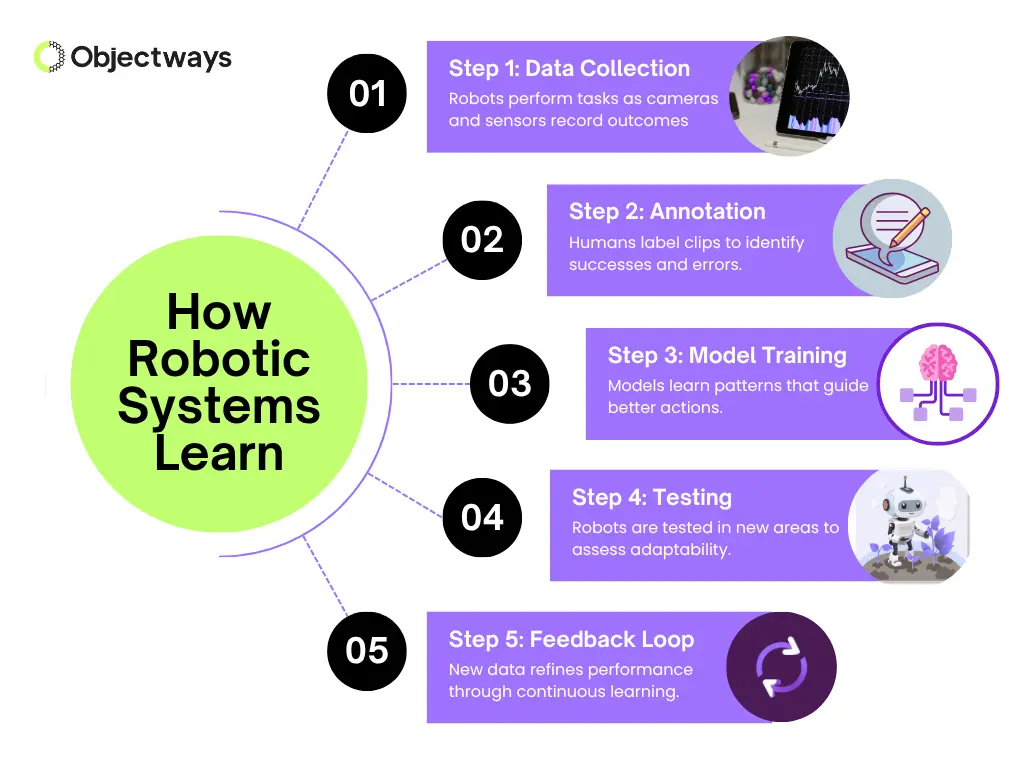

The Data Collection Pipeline

Physical Intelligence operates what Sergey Levine describes as a sophisticated continuous feedback loop. The process works like this: data collectors gather robotics information from multiple sources—the test stations in their San Francisco facility, warehouse installations across the country, small kitchens equipped with espresso machines and cooking tools, and any environment where they can deploy standardized hardware. That raw data trains new versions of their foundation models. When a model is trained, it returns to the test stations for evaluation and validation. If it performs well, it's deployed more broadly. If it fails in specific ways, the failure data feeds back into the next training cycle.

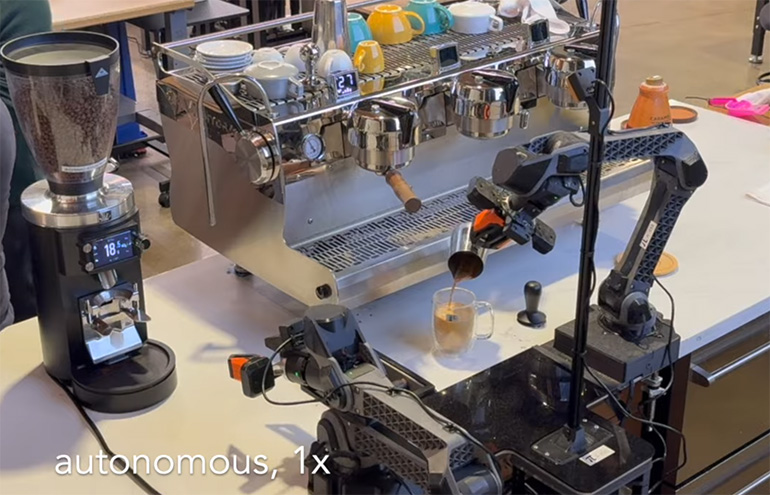

This isn't unique to Physical Intelligence—many AI companies use similar approaches. What makes Physical Intelligence's pipeline distinctive is the standardization of hardware and the diversity of tasks. Rather than collecting data from hundreds of proprietary robotic systems designed for specific industries, they use off-the-shelf robotic arms costing approximately $3,500 and expose them to a carefully curated range of physical challenges. The espresso machine, the zucchini peeler, the laundry folding station—each is deliberately chosen to teach the model something fundamental about physics and manipulation that will transfer to new domains.

Levine notes that the material cost of these arms, if manufactured in-house, would drop below

Why Generalization Matters More Than Hardware

There's a counterintuitive truth embedded in Physical Intelligence's approach: good intelligence compensates for imperfect hardware. A few years ago, Levine observes, roboticists would have been shocked that arms costing $3,500 could accomplish anything useful. Today, with sufficiently advanced models, these unglamorous machines perform complex tasks that would have required custom-engineered solutions just years ago.

This inverts the traditional robotics philosophy. Historically, companies built better hardware, expecting that would solve problems. Boston Dynamics spent years building increasingly impressive robots that could run, climb, and dance. Tesla is investing heavily in Optimus, a humanoid robot designed from first principles. These approaches prioritize mechanical perfection.

Physical Intelligence's approach prioritizes intelligence. The reasoning is simple: if you have a model that can generalize across tasks and environments, you can use less sophisticated hardware because the intelligence layer compensates for hardware limitations. Conversely, the most advanced hardware becomes useful only when paired with sufficiently intelligent control systems. By inverting the optimization priority, Physical Intelligence opens a path to rapid scaling that hardware-first approaches cannot match.

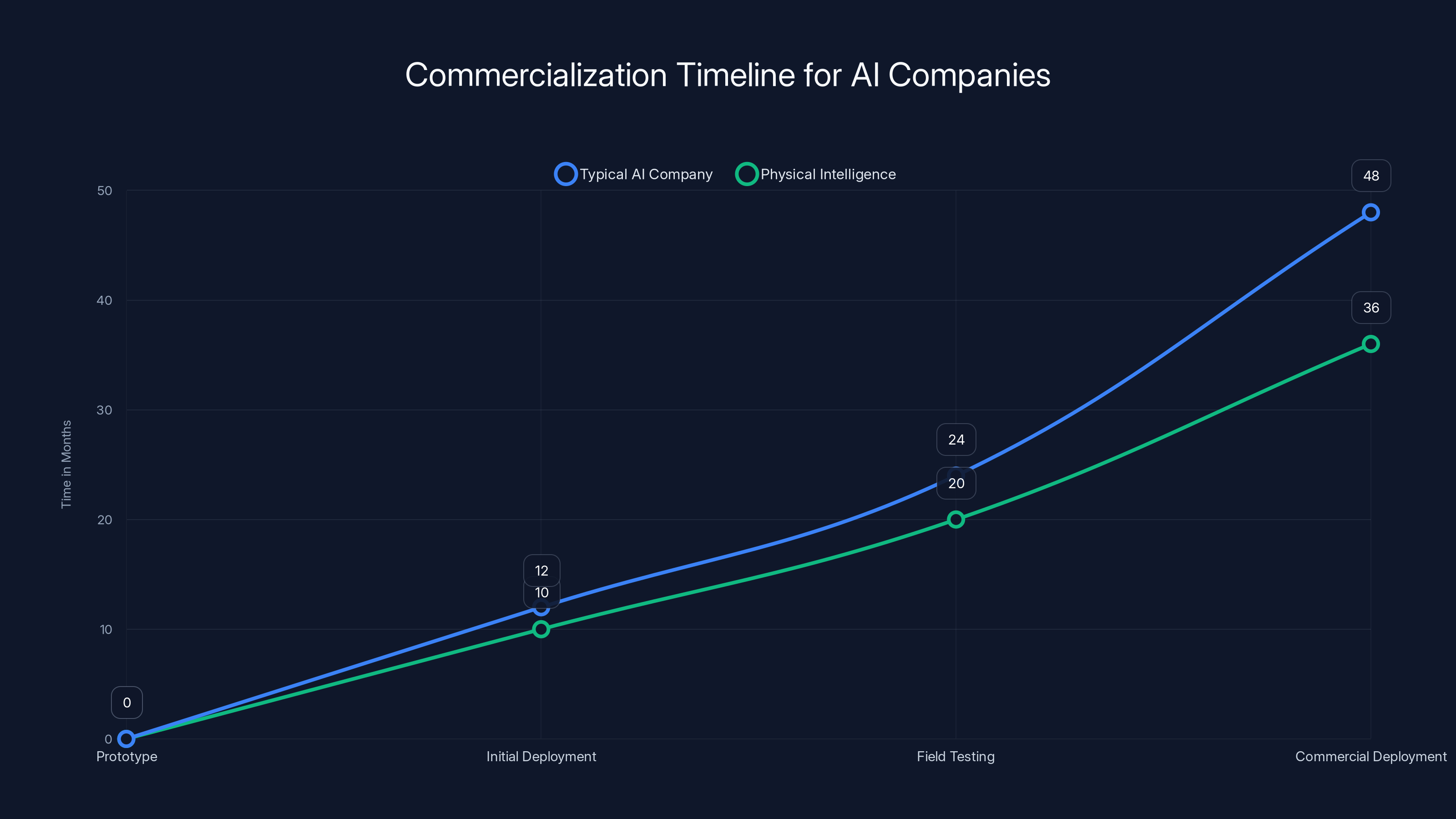

Physical Intelligence is projected to reach commercial deployment faster than typical AI companies, potentially in 36 months due to experienced team and strong funding. Estimated data.

The Founding Team and Strategic Vision

Sergey Levine: Decades of Robotics Research

Sergey Levine brings a unique combination of academic rigor and practical vision to Physical Intelligence. As an associate professor at UC Berkeley, his research has focused on how robots can learn from diverse data sources and how machine learning can enable flexible robotic behavior. Unlike many academic researchers who stay primarily focused on publications and funding cycles, Levine has maintained deep connections to industry problems and practitioners.

His research group has explored imitation learning—where robots learn by observing demonstrations—and reinforcement learning in robotic contexts. This background is crucial because it means Physical Intelligence's approach isn't based on untested theories but on years of published research that has been validated in peer review. The foundation models they're building aren't speculative concepts but practical applications of ideas that Levine and colleagues have been refining for over a decade.

When Levine gestures toward the robotic arms attempting various tasks and describes the approach as "Chat GPT for robots," he's translating complex concepts into understandable language. But he's also accurately capturing the philosophical shift: just as Chat GPT emerged when transformer architectures met large-scale text data, robot capabilities emerge when foundation models meet diverse physical-task data.

Chelsea Finn: Learning at Scale

Chelsea Finn, who completed her PhD under Levine's supervision at UC Berkeley before establishing her own laboratory at Stanford, represents the next generation of robotics researchers. Her work focuses on learning algorithms that work efficiently even when data is limited and on meta-learning—teaching systems to learn how to learn more effectively. This background directly addresses one of robotics' critical challenges: each new task doesn't require re-collecting millions of examples if the system can learn quickly from smaller datasets.

Finn's presence on Physical Intelligence's founding team signals a commitment to research-grade rigor in a startup context. She brings both theoretical sophistication and practical understanding of what deployment-ready systems require. Her research on few-shot learning is particularly relevant: if robots can learn new tasks from relatively few examples, the time from identifying a customer need to deploying a solution compresses dramatically.

Karol Hausman: Bridging Industry and Academia

Karol Hausman's career path—from Google Deep Mind to Stanford—positions him as the bridge between cutting-edge research and commercial viability. Deep Mind's robotics work has explored everything from robotic grasping to multi-robot coordination. His teaching at Stanford kept him connected to emerging research while his industry experience provided practical context.

Hausman brings expertise in robotic learning systems that scale, in managing complex robotics infrastructure, and in translating research findings into deployed systems. This is particularly important because many roboticists can design systems that work in controlled labs but falter in real-world deployment. Hausman's background suggests Physical Intelligence's team thinks about real-world robustness from day one.

Lachy Groom: Vision and Execution

Lachy Groom's role might seem unexpected in a technical robotics company. At 31, Groom is not a roboticist. He sold his first company nine months after starting it at age 13 in Australia. After moving to the United States, he became an early employee at Stripe, where he gained intimate understanding of how platforms scale, how companies build for network effects, and how to think about economic models and unit economics.

Groom's five years as an angel investor before Physical Intelligence were formative. His portfolio included Figma (which scaled the design tool market), Notion (which created a category of flexible productivity tools), Ramp (which simplified corporate expense management), and Lattice (which modernized HR systems). These aren't just successful companies—they're companies that each identified a problem, built a platform that offered generalized solutions, and scaled into massive categories.

Groom brought similar thinking to Physical Intelligence: What if robotics wasn't a collection of specialized solutions but a platform? What if, like Figma, you built tools that worked across different use cases? What if you thought about unit economics and scalability from the beginning rather than treating those as afterthoughts?

When Groom decided to leave the investor role to work full-time at Physical Intelligence, his decision was based on simple criteria: the team included people who'd been working on this problem for decades and who believed the timing was finally right. For a founder with his track record, that conviction was sufficient. His role isn't to solve robotics challenges—his teammates have decades for that. His role is to ensure that whatever they build can actually scale, reaches customers, and creates genuine economic value.

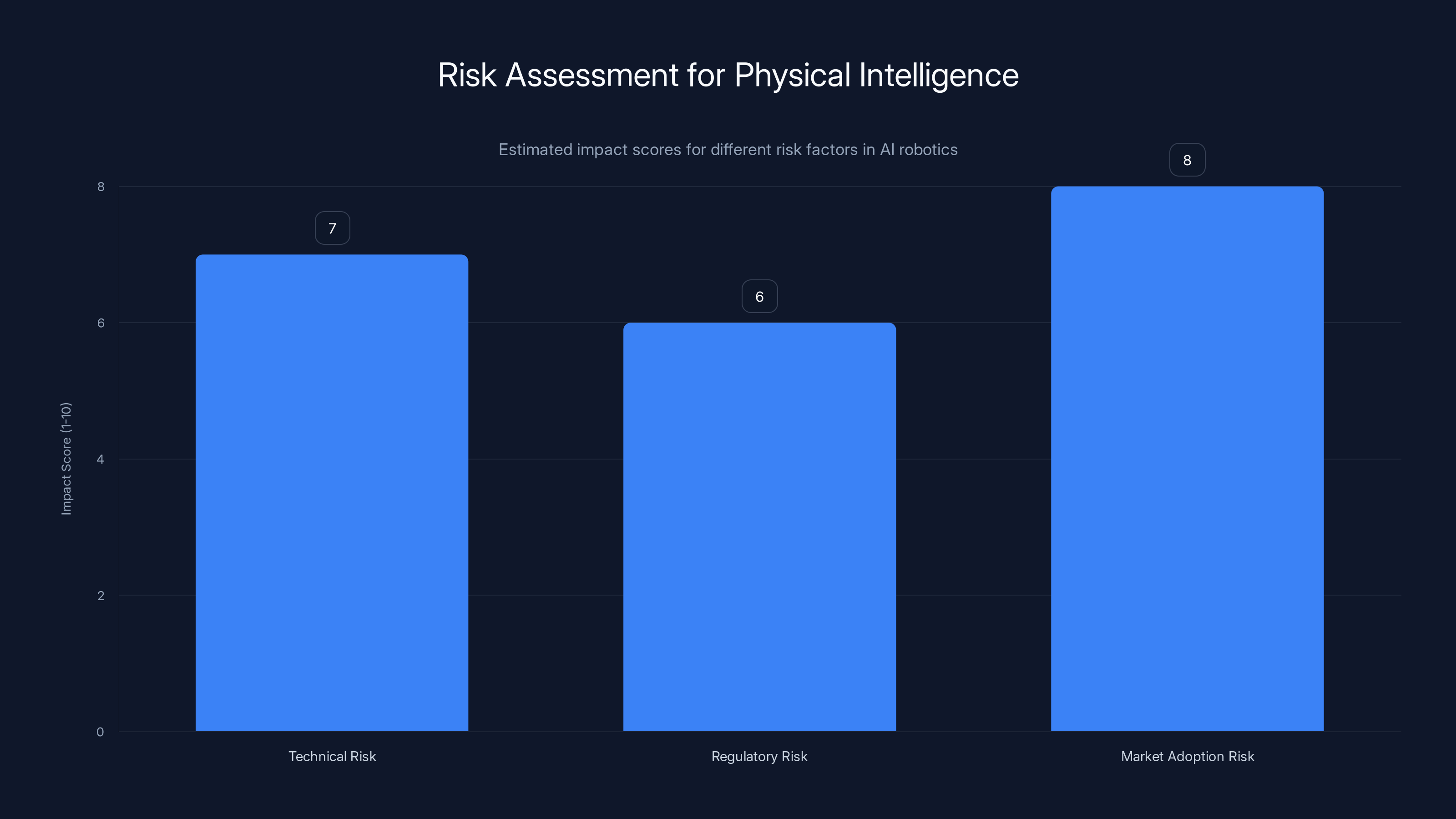

Market Adoption Risk is estimated to have the highest impact on Physical Intelligence's success, followed by Technical and Regulatory Risks. Estimated data.

Technical Deep Dive: How Foundation Models Work in Robotics

From Vision to Action: The Perception-to-Control Pipeline

Robotic systems must solve an unusual problem: they receive visual input about their environment and must translate that perception into physical actions. A human sees a pile of laundry and knows instinctively how to approach folding a particular shirt. A robot must detect the shirt in the image, understand its current configuration, recognize the goal state, and then issue motor commands to achieve that goal.

Traditionally, this has been solved through task-specific programming. Engineers would write code: if you detect a rectangular object, apply force here; if you encounter resistance, increase torque; if the object rotates unexpectedly, adjust your approach. This works for highly controlled environments but fails catastrophically in the real world where variation is constant.

Foundation models approach this differently. Rather than encoding specific rules, they learn statistical patterns from diverse examples. If you show a model thousands of examples of folding different fabrics, applying different forces, and encountering different kinds of resistance, the model learns something deeper: a general understanding of how objects respond to forces and how to achieve particular configurations. This learned understanding transfers to situations the model has never explicitly encountered.

The technical implementation involves several components working together. First, visual encoders extract relevant features from camera input. Rather than transmitting full image data (which would be computationally expensive), encoders compress visual information into representations that capture essential details. These representations flow into a world model—a neural network that understands how the physical world responds to actions. Finally, a policy network translates the world model's predictions into motor commands sent to the robot's actuators.

Multi-Modal Training Data and Task Diversity

The quality of foundation models depends critically on training data diversity and quality. Physical Intelligence addresses this through deliberate task selection. Their test kitchens aren't just for show—they serve a specific research purpose. An espresso machine presents challenges around precise force application, understanding fluid dynamics, and adapting to component variation. Cooking tasks expose the model to food items with varying textures, different cooking utilities, and the consequences of imprecise actions.

The diversity isn't random. Each task is chosen to teach the model something fundamental that will transfer to new domains. Learning to peel vegetables teaches general principles of reducing force when resistance decreases. Learning to fold different fabric types teaches generalization across similar but distinct tasks. Learning to operate kitchen equipment teaches adaptation to mechanical systems with different force-feedback characteristics.

This approach parallels how large language models are trained on diverse internet data. Just as GPT-4 learns language patterns from books, code, articles, and conversations—and this diversity enables it to adapt to writing in styles it never explicitly learned—robotic foundation models learn from diverse physical tasks and can adapt to new tasks drawing on learned principles.

Transfer Learning and Few-Shot Adaptation

One of foundation models' most powerful capabilities is transfer learning: the ability to adapt to new tasks by building on learned fundamentals rather than starting from scratch. If a robot has learned general grasping principles from thousands of examples, it can often adapt to a new object type with far fewer examples than would be required for a system trained from scratch.

Physical Intelligence's commitment to few-shot adaptation is strategically important. If deploying a robot at a new warehouse required collecting thousands of images of local tasks and retraining for weeks, the service would never reach small and medium businesses. But if a robot can adapt to local conditions by observing a human perform the task a few times, deployment becomes practically feasible.

This capability is what Sergey Levine references when discussing how good intelligence compensates for imperfect hardware. A less capable perception system might require perfectly consistent lighting and clearly visible objects. A model trained on diverse real-world data can handle variable lighting, partial occlusion, and novel object types because it has learned fundamental principles of object recognition that generalize.

Scaling Laws and Model Emergence

Foundation models exhibit emergent properties: as they're trained on larger datasets with more capacity, they develop new capabilities that weren't explicitly programmed and that didn't appear in smaller models. This emergence is a key advantage of the foundation model approach over traditional robotics software.

In language, this emergence manifests as the model suddenly developing chain-of-thought reasoning, or code generation ability, or reasoning about questions phrased in ways it was never explicitly trained on. In robotics, similar emergence might mean a model suddenly becomes capable of teaching other models, or of planning multi-step sequences of actions, or of communicating its uncertainty and asking for help.

Physical Intelligence's infrastructure—their distributed data collection, their continuous training pipeline, their commitment to standardized hardware that enables scaling—is all designed to benefit from these scaling properties. Each new robotic installation isn't just a customer deployment; it's a data collection opportunity that makes the foundation models smarter for all future customers.

Commercial Applications and Use Cases

Warehouse Automation and Logistics

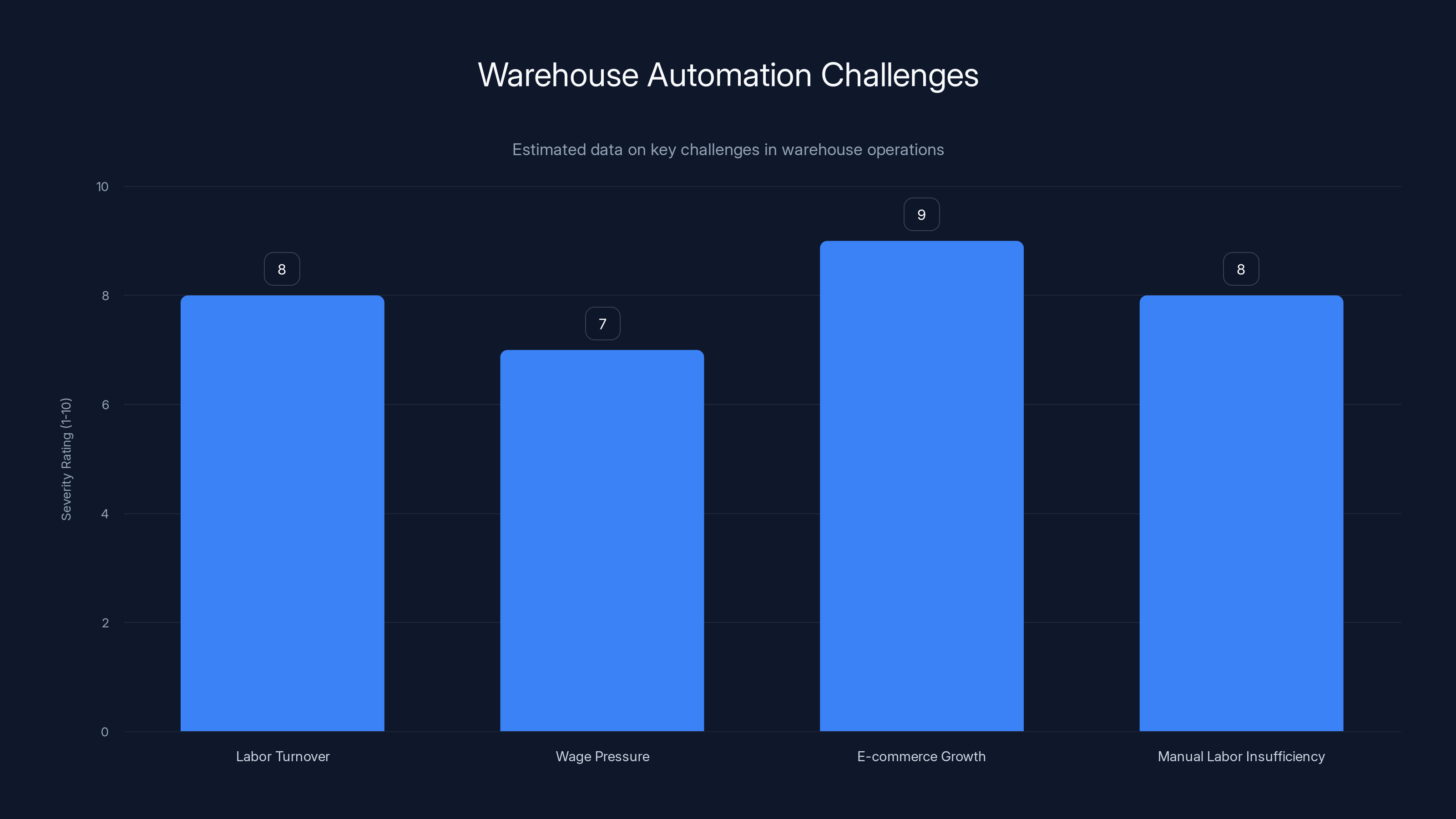

Warehousing represents the most immediate commercial opportunity for Physical Intelligence's technology. Modern warehouses face acute labor challenges: working conditions are difficult, employee turnover exceeds 50% annually in many facilities, and wage pressure is increasing. Simultaneously, e-commerce volume continues growing, making manual labor increasingly insufficient even as labor becomes more expensive.

Current warehouse automation is narrow. Conveyor belts, sorting machines, and automated storage systems each solve specific problems but don't adapt to variation. When a shipment contains items that aren't standard boxes, human workers must intervene. When seasonal product mix changes, equipment must be reconfigured or replaced. When a new customer with different requirements comes online, solutions must be custom-engineered.

Flexible robotic arms trained on Physical Intelligence's foundation models could adapt to these variations. The same arm that sorts packages could pick items from shelves, pack boxes, palletize goods, or perform dozens of other warehouse tasks—and adapt as tasks change. For logistics companies managing thousands of SKUs with varying dimensions, weights, and fragility, this flexibility is transformative.

The economics work at scale. A flexible robotic system that can be deployed across multiple tasks and that adapts quickly to new environments could justify capital investment that task-specific equipment cannot. Labor costs at $20-30 per hour can be justified for variable, difficult tasks only if automation costs can match or undercut labor's blended cost over equipment lifetime.

Healthcare and Assisted Living

Healthcare facilities face unique challenges where flexibility is essential. Patient rooms are inherently variable—different layouts, different patient capabilities, different care needs. A robot useful in one environment might be nearly useless in another. Simultaneously, healthcare labor shortages are among the most acute across all industries. Senior care facilities particularly struggle with staffing.

Applying Physical Intelligence's technology to healthcare means robots that can assist with patient transfer, help with bathing and grooming, fetch items, perform basic cleaning, and adapt as patient conditions change. Unlike manufacturing where tasks repeat, healthcare robotics must handle enormous variation and adapt quickly.

The training approach matters here. Rather than hand-programming responses to every scenario, Physical Intelligence's foundation models could learn general principles of gentle handling, body mechanics, and patient assistance from diverse training data. A model trained across many patient scenarios could adapt to the unique needs of an individual patient by observing how care providers approach that patient.

Food Service and Commercial Kitchen Operations

Commercial kitchens are another domain where Physical Intelligence is investing heavily. The espresso machines and cooking stations in their test kitchen aren't gratuitous—they're infrastructure for training models to work in food service environments. This is strategically important because food service combines multiple challenges: food has variable properties, equipment varies, and customer preferences change frequently.

Applications range from restaurant chains automating repetitive prep work—chopping vegetables, portioning proteins, plating dishes—to commercial kitchens solving labor shortages during peak hours. More ambitiously, flexible robotic systems could enable small food businesses to offer products at scales that would otherwise require hiring multiple staff members.

The training data from food preparation is particularly valuable to foundation models generally because it teaches principles about force adaptation, detecting doneness, recognizing when food has reached a target state, and responding to unexpected changes. These skills transfer to any task requiring sensitive force control and adaptation to feedback.

Manufacturing and Assembly

While manufacturing automation is well-established, current approaches assume stable production runs of standard products. Product variety, customization, and shorter product lifecycles are pushing manufacturers toward more flexible automation. Physical Intelligence's technology enables plants to rapidly retool when product mix changes or new products come online.

A traditional assembly line might require weeks to reconfigure for a new product variant. A flexible robotic system could potentially adapt in hours or days by learning from technicians demonstrating the new assembly sequence. This capability particularly benefits contract manufacturers who work with multiple customers and cannot afford extensive reconfiguration between customer-specific products.

Warehouse operations face significant challenges with high labor turnover, increasing wage pressure, and growing e-commerce demands. Estimated data.

Competitive Landscape and Alternative Approaches

Traditional Robotics Companies

Companies like ABB, KUKA, and Fanuc have dominated industrial robotics for decades. Their strength lies in reliability, proven performance in high-volume manufacturing, and extensive installation bases. However, their approach is fundamentally task-specific: robots are designed and programmed for particular applications, and reconfiguration is expensive.

These companies are aware of AI advances but have proven slow to integrate foundation models into their products. Their business models depend on long installation cycles and substantial professional services revenue, which actually disincentivizes the kind of plug-and-play, rapidly deployable systems that AI-driven generalization enables. A robot that customers can deploy and adapt themselves is a robot that generates less long-term professional services revenue.

Physical Intelligence's advantage is that they're building from the AI-first principles rather than trying to retrofit AI onto legacy systems. This matters more than it might initially appear. A robot designed from day one to be trained on diverse data and adapted quickly will have architectural advantages over a robot retrofitted with AI capabilities.

Robotics-Focused AI Startups

Several other startups are pursuing similar foundation model approaches in robotics. Some focus on specific domains—one company might specialize in manipulation, another in mobile robotics, another in specific industries like agriculture. This domain focus has advantages: you can optimize data collection, tailor models to specific constraints, and build customer relationships in your niche.

Physical Intelligence's advantage is breadth combined with depth. By training on diverse tasks rather than optimizing for one vertical, they develop models that generalize more broadly. This enables them to serve multiple industries simultaneously and to benefit from data collected in one domain improving performance in others. It's a higher-risk strategy—trying to be excellent at many things rather than exceptional at one—but it has higher upside if executed successfully.

Software-Based Approaches: Digital Twins and Simulation

Some companies focus on simulation and digital twins—creating accurate virtual models of robots and environments that can be used for planning and training. This approach has real advantages: you can test thousands of scenarios in simulation before deploying anything physical, and you can iterate quickly without physical hardware.

The challenge with pure simulation approaches is the reality gap. A robot trained entirely in simulation often fails in the real world because the simulation can't capture all real-world details. Physics simulators can approximate reality but not capture it perfectly. Wear on hardware, subtle material properties, environmental conditions—simulation inevitably oversimplifies these factors.

Physical Intelligence's commitment to real-world data collection, even though it's slower and more expensive than pure simulation, directly addresses this problem. Their models are trained on real robots in real environments, which means they learn the actual patterns rather than simulated approximations.

Humanoid Robotics and Specialized Hardware

Companies like Boston Dynamics and Tesla's Optimus are investing heavily in humanoid robot platforms. The reasoning is that humans are optimized for navigating human environments, so copying human form factors makes sense. Humanoid robots can use existing tools, fit through doorways, and work on stairs.

Physical Intelligence's strategy is notably different. They're not betting on humanoid form factors. They're using off-the-shelf, cheap industrial arms because they believe intelligence can compensate for sub-optimal hardware. A non-humanoid robot with superior AI might accomplish more than a humanoid robot with inferior AI. This is a more contrarian bet, and it's unclear who will ultimately be proven correct. However, Physical Intelligence's advantage is faster iteration: cheap hardware enables deploying many more systems, collecting far more data, and improving models more rapidly than a company constrained by the expense of humanoid hardware development.

Market Dynamics and Commercialization Timeline

Current Deployment Status

Physical Intelligence is in the phase where they're deploying test systems to customer environments—warehouses, facilities, locations where they can gather real-world data while providing preliminary value to early customers. This is typical for companies with advanced AI: you want real-world feedback and data collection to be happening in parallel with technical development.

What varies is the timeline to commercial viability. Some companies move from prototype to production-ready systems in 18-24 months. Others take 4-5 years. The variability depends on how close early prototypes are to what customers actually need and how much engineering remains before systems are reliable enough for production environments.

Physical Intelligence's timeline is compressed somewhat by the quality of their team and their access to funding. Having founders with decades of research experience and an investor (Groom) who has invested in companies at precisely the point where they transition from promising to dominant means they're probably moving faster than startups with less experienced teams.

Required Engineering Maturity for Commercial Deployment

When Physical Intelligence's systems begin commercial deployment, they'll need to meet significant reliability requirements. Warehouse customers operating 24/7 expect equipment availability above 95%. A system that works perfectly 90% of the time and requires human intervention 10% of the time isn't worth deploying at scale.

Achieving this reliability requires not just strong AI models but robust software engineering: graceful degradation when something goes wrong, clear error messages that operators can respond to, integration with existing warehouse management systems, redundancy and failover capacity, and extensive field testing in actual conditions.

This engineering work is substantial and often underestimated by companies coming from AI backgrounds. The model is 50% of the solution; the other 50% is making sure the model is wrapped in production-grade software that can be deployed, monitored, maintained, and upgraded at scale. Physical Intelligence's team includes engineers who have worked on production systems at scale (Groom's experience at Stripe is particularly relevant here), which probably means they're more realistic about this engineering effort than typical academic-founded startups.

Pricing and Economic Models

Physical Intelligence will need to develop pricing models that work for different customer segments. A major e-commerce logistics company handling millions of packages daily can justify significant capital investment. A small manufacturer with dozens of employees needs dramatically different economics.

Likely pricing models include:

- Capital equipment sales: Customers buy robots outright, similar to traditional robotics. Margins are probably 40-60%, which is typical for specialized equipment.

- Leasing models: Robots deployed on monthly or annual leases with service and support included. This is more customer-friendly for operations with capital constraints.

- Per-use pricing: Customers pay per task completed or per hour of operation. This could work for certain use cases and generates data about economic value created.

- Subscription intelligence: The robot hardware is relatively inexpensive; value accrues from updated models that improve performance. Subscription fees for model updates could become significant revenue.

Most likely, Physical Intelligence will eventually support multiple pricing models depending on customer type and use case. This flexibility is an advantage of software-centric approaches: pricing can be adjusted post-deployment without hardware changes.

Funding Requirements and Path to Profitability

Building large foundation models is expensive. Training costs, hardware for test facilities, recruiting top-tier talent, and managing infrastructure at scale all require substantial capital. Physical Intelligence has undoubtedly raised significant funding, though specific amounts may not be public.

Path to profitability depends on their commercialization strategy. If they focus initially on premium customers—major logistics companies with massive facilities—they can potentially reach positive unit economics relatively quickly. Each deployed system generates data that improves all their models, creating increasing returns to scale.

Alternatively, if they pursue market penetration, investing initially in customer acquisition and potentially taking losses on early deployments to gather data, profitability might come later but market position would be stronger. Groom's background in platform companies suggests he's probably thinking about long-term market position rather than short-term profitability, which means the latter path is plausible.

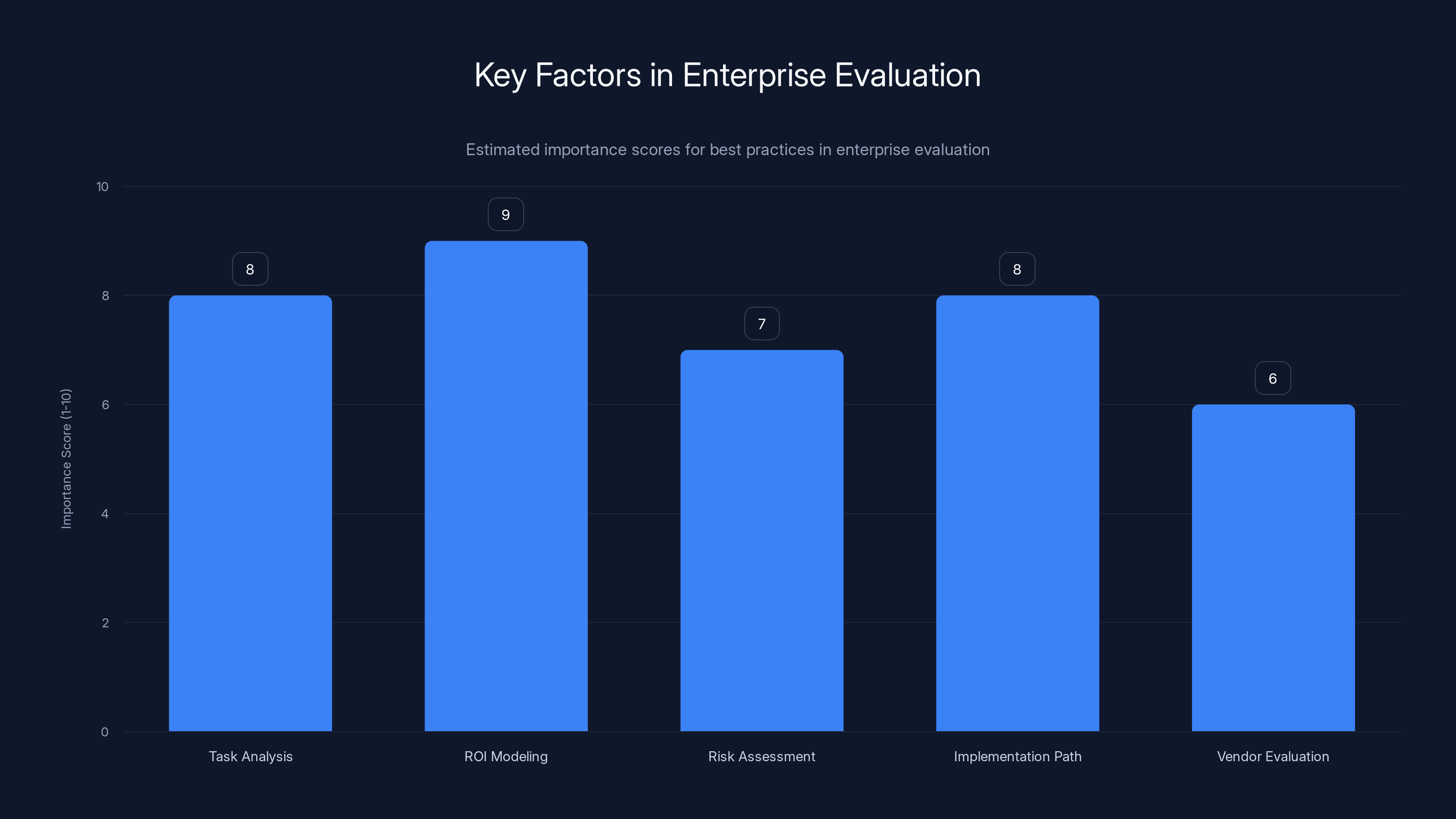

ROI Modeling and Task Analysis are critical in enterprise evaluation, scoring highest in importance. Estimated data.

Integration with Broader AI Trends

Foundation Models Across Industries

Physical Intelligence isn't inventing the foundation model paradigm—they're applying it to a new domain. The success of foundation models in language (GPT), vision (CLIP, Stable Diffusion), and code has established the pattern: train on massive diverse data, fine-tune for specific applications, and benefit from surprising emergent capabilities.

What's distinctive about applying this to robotics is that training data is expensive to generate. Language training data exists in abundance on the internet. Vision data can be scraped at massive scale. Robotics data requires actual robots taking actions in environments. This is why Physical Intelligence's distributed data collection infrastructure is so strategically important—it's their competitive moat.

As foundation models proliferate across industries, we'll see a consistent pattern: first-mover companies in each domain (OpenAI with language, Stability.ai with images, Physical Intelligence with robotics) establish strong positions because they invested in data infrastructure early when others didn't recognize its importance.

Integration with Edge Computing and Distributed Systems

Physical Intelligence's models will need to run on edge hardware at robots, not just on centralized cloud servers. This isn't just a technical preference—it's necessary for reliability. A warehouse robot can't be disabled by cloud connectivity issues. A robot assisting a patient can't require network connectivity to functioning.

Edge deployment requires model compression and optimization. The foundation model trained on petabytes of data in cloud GPUs must be compressed to run efficiently on the compute available on a robot. This is technically challenging but solvable, and companies like TensorFlow have made it easier.

Likely future architecture: a large model trains in the cloud on diverse data. That model is compressed and deployed to robots. Robots use the deployed model for inference and collect error data. Error data feeds back to cloud systems, which retrain and improve the model. Updated models are pushed back to robots. This cycle enables continuous improvement while maintaining the ability to operate offline.

Connections to Broader Robotics Platforms

Successful robotics platforms typically become ecosystems. Much like how iOS and Android became platforms for applications beyond the phone manufacturer's initial vision, Physical Intelligence's models could become a platform for robot applications they didn't initially envision.

Companies building specific robot applications—specialized hardware for agriculture, or healthcare, or other domains—could license Physical Intelligence's foundation models and build on top of them. This would be analogous to how Hugging Face has become a platform for language model applications: researchers and companies build specific applications on shared foundation models rather than training everything from scratch.

This ecosystem approach, if realized, would dramatically increase Physical Intelligence's market size. They wouldn't be limited to the applications they can build themselves but would benefit from the creativity of thousands of developers and companies building on their infrastructure.

Implementation Considerations for Enterprise Adoption

Infrastructure Requirements

Organizations considering Physical Intelligence's systems (once they become commercially available) need to think about infrastructure beyond the robots themselves. This includes:

- Network infrastructure: Robots need reliable connectivity for operation and model updates. Wireless networking must be reliable in factory environments where interference and dense RF environments are common.

- Data infrastructure: Systems collecting data from robots need to handle volume and process data for model training. On-premise or cloud deployment affects architecture choices.

- Integration points: Robots must integrate with warehouse management systems, manufacturing execution systems, or other operational systems. APIs and connectors need to be developed.

- Physical space: Robots need charging infrastructure, maintenance stations, and safe working zones. Physical design of facilities might need adjustment for human-robot collaboration.

Enterprise IT organizations often underestimate infrastructure requirements for robotics, treating robots as appliances rather than systems. Physical Intelligence's success depends partly on how thoroughly they address these infrastructure requirements either directly or through partner integrations.

Workforce Transition and Training

Deploying robots that automate tasks inevitably raises questions about worker displacement. Organizations need to think carefully about this and develop training programs that reskill workers for higher-value work. A warehouse that automates routine picking might need more workers trained in robot maintenance, system operation, and exception handling.

Companies that manage this transition well—investing in workforce development, maintaining stable employment while shifting roles, and treating workers as assets to be developed—end up with more engaged and productive workforces. Companies that treat automation as an opportunity to reduce headcount tend to face culture problems, retention challenges, and reduced quality.

Physical Intelligence will likely encourage customers to think about workforce transition positively, not because of altruism but because customers who handle transitions well become better references and have happier operational teams that cooperate more effectively with robots.

Maintenance and Ongoing Support

Robotics systems require more ongoing maintenance and support than typical software. Hardware wears, degrades, and eventually needs replacement. This creates an opportunity for service revenue, but it also creates a responsibility to ensure customers can access support when they need it.

Companies deploying Physical Intelligence systems need to factor in ongoing maintenance costs, potential downtime, parts replacement, and access to technical support. This is where robotics differs from pure software—you can't update a robot's motor with a software patch. When hardware fails, the robot is down until replacement arrives and is installed.

Foundation model-trained robots exhibit superior adaptability and skill transferability compared to traditional robots, indicating a more versatile and efficient approach. Estimated data based on described capabilities.

Future Roadmap and Long-Term Implications

Multi-Modal Learning and Cross-Domain Transfer

The next frontier beyond current foundation models is true multi-modal learning: models that understand text, vision, and physical interaction simultaneously. A robot that can read instructions, understand images of the environment, and understand physical feedback could handle dramatically more complex scenarios.

Physical Intelligence is probably already exploring this. A model that understands natural language instructions, can process images of environments, and can interpret physical feedback from manipulating objects could approach human-level reasoning about physical tasks. This is significantly harder than single-modality foundation models, but the potential capabilities justify the effort.

Reasoning and Planning at Scale

Current large language models are surprisingly good at reasoning, but only for tasks within the domain of language. Extending reasoning capabilities to physical planning—thinking through multi-step sequences of actions, anticipating consequences, backtracking when initial approaches fail—requires both better models and better training approaches.

Robotics is an ideal proving ground for planning and reasoning research because physical world consequences are clear and measurable. A plan that doesn't work will be immediately obvious when the robot fails. This provides strong learning signal that could drive advancement in reasoning capabilities more effectively than reasoning benchmarks based on text.

Scaling to Complete Autonomy

The ultimate goal of robotics research has always been complete autonomy: robots that can understand goals expressed in natural language and pursue those goals with minimal human direction. Current systems still require substantial human supervision, clear task definitions, and limited scope of action.

Physical Intelligence's foundation models are a significant step toward this goal. Rather than requiring explicit programming of behavior, they can be adapted to new tasks through example or instruction. But true autonomy still requires additional capabilities: understanding complex multi-step goals, reasoning about tradeoffs and constraints, asking for help when appropriate, and explaining their reasoning to human supervisors.

These capabilities are beyond current foundation models but not impossibly far. The combination of better models, better training approaches, and more diverse training data could plausibly enable significant progress in the next 5-10 years.

Alternative Solutions and Complementary Approaches

For Enterprises Seeking Robotic Automation Solutions

When evaluating robotics solutions for enterprise deployment, organizations have several alternatives worth considering alongside Physical Intelligence:

Traditional Industrial Robotics (ABB, KUKA, Fanuc) remain the established choice for high-volume manufacturing. Their advantages include extensive proven deployment history, robust support ecosystems, and reliability in controlled environments. They're ideal when you have stable, high-volume tasks that don't require frequent changes. The disadvantage is inflexibility and the cost of reconfiguration when requirements change.

Task-Specific Robotics Solutions (various startups focused on particular verticals) offer better economics for specific domains like food processing, agriculture, or healthcare. These companies often operate robots optimized for their specific domain, which can mean better performance for that use case but less flexibility across applications.

Humanoid Robotics Platforms (Tesla Optimus, Boston Dynamics, others) promise ultimate flexibility through human-form-factor robots. These are still mostly in research and early deployment phases, but they represent a fundamentally different approach: instead of training a robot to do human tasks, build a robot that can use human tools and navigate human spaces. The advantage is zero reconfiguration across diverse environments. The disadvantage is that humanoid robots are dramatically more expensive to develop and deploy, and are further from commercial maturity than specialized platforms.

Automation-as-a-Service Models where companies like OSARO or others sell robotic automation capabilities as a service rather than selling hardware. Customers pay for work completed rather than owning equipment. This transfers hardware and model risk to the service provider, which can be attractive for risk-averse organizations but typically costs more per unit of work than ownership.

For organizations specifically interested in AI-powered robotic intelligence comparable to Physical Intelligence, Runable offers an interesting alternative approach focused on automation and AI-driven workflows. While Runable emphasizes software automation, workflow coordination, and AI agents for content and documentation generation (at $9/month), it represents a different tier of automation—software-based rather than robotics-focused. Organizations looking for comprehensive automation solutions that include both software automation and task orchestration might consider platforms like Runable that handle the broader automation landscape, potentially complementing physical robotics with software-based automation for non-physical tasks.

Hybrid Approaches Combining Multiple Solutions

Many enterprises find the best path forward combines multiple solutions. A warehouse might use:

- Physical Intelligence robots for variable picking and packing tasks

- Traditional conveyor and sorting systems for routine part-to-part tasks

- Task-specific robots for standardized, high-volume operations

- Human workers for exception handling, quality checks, and tasks requiring judgment

This hybrid approach isn't failure to choose one solution but pragmatic recognition that different tools solve different problems optimally. Organizations should evaluate solutions based on specific task characteristics rather than trying to force one platform to do everything.

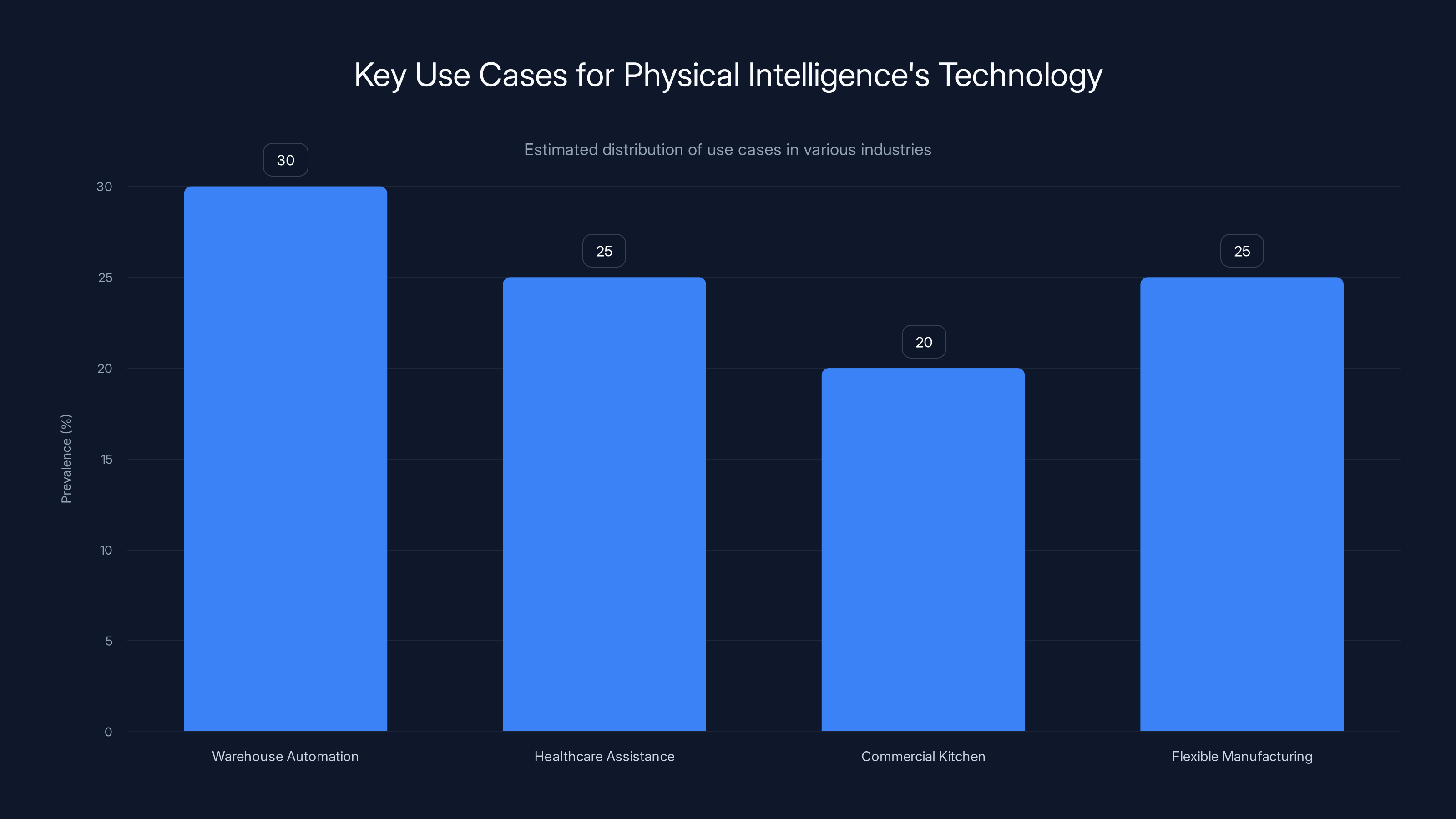

Physical Intelligence's technology is primarily applied in warehouse automation, healthcare, commercial kitchens, and flexible manufacturing, with each sector having significant but varied prevalence. Estimated data.

Risk Factors and Realistic Assessment

Technical Risk: Model Generalization

The central bet of Physical Intelligence's approach—that foundation models will generalize robustly across diverse tasks and environments—is reasonable but not certain. There are plausible scenarios where models trained on diverse data don't generalize well, where performance degrades outside training distribution, or where edge cases require continuous human intervention.

This risk diminishes over time as the company accumulates more diverse training data, but in early deployment phases, customers might encounter situations where the robot doesn't behave as expected. Organizations considering Physical Intelligence need to evaluate whether their use case requires near-perfect reliability or whether some failure rate is tolerable.

Regulatory and Safety Risk

Robots operating in human-occupied spaces create regulatory challenges. Workplace safety regulators have increasingly strict rules about human-robot collaboration. Healthcare regulators will have strict requirements about robots assisting with patient care. Food safety regulators will have requirements about robots in kitchens. Physical Intelligence's technology is good, but regulatory compliance is orthogonal to technical capability.

The company needs to invest in safety certification, compliance documentation, and working with regulatory bodies. This is primarily a business development problem, not a technical one, but it's a real risk that could delay commercialization or increase costs.

Market Adoption Risk

Even if Physical Intelligence's technology works perfectly, adoption might be slower than expected if:

- Customers are risk-averse and prefer proven traditional solutions

- Integration with legacy systems proves more difficult than anticipated

- Skilled workforce for managing AI-powered robots is scarce

- Capital costs prove too high for smaller organizations

- Public perception or worker sentiment turns negative toward robotic automation

Historically, new automation technologies take longer to deploy widely than early proponents expect. Nuclear power was supposed to be too cheap to meter. Automation was supposed to eliminate jobs entirely. Drones were supposed to deliver packages ubiquitously by 2015. Reality is more complex than optimistic projections.

Physical Intelligence will likely succeed, but probably on a slower timeline and smaller scale initially than the most bullish projections suggest.

Competitive Risk

The robotics space is attracting significant investment and talent. Other well-funded startups are pursuing similar approaches. Larger companies like Tesla, Boston Dynamics, and traditional robotics manufacturers are developing AI capabilities. Physical Intelligence's advantage right now is team quality and early-mover status in the foundation model space, but these advantages can erode.

The company needs to move quickly to:

- Deploy systems that generate real-world data

- Build relationships with important customers

- Establish standards and ecosystems that lock in partners

- Continue recruiting and retaining world-class talent

Failure on any of these fronts could result in a situation where Physical Intelligence's technology is excellent but they're not the company that profits from it because competitors moved faster to commercialization or customer adoption.

Best Practices for Enterprise Evaluation

Assessment Framework

Organizations evaluating Physical Intelligence or similar platforms should develop a structured assessment framework:

1. Task Analysis: Clearly define the tasks you want to automate. Are they truly variable or are they routine with occasional exceptions? Are they suitable for robots or would software automation be more appropriate? What's the frequency of task variation?

2. ROI Modeling: Develop detailed ROI models including capital costs, operating costs, training costs, infrastructure investment, and realistic timelines to positive ROI. Be honest about failure scenarios and include contingency.

3. Risk Assessment: Identify risks specific to your organization: regulatory requirements, safety concerns, integration challenges, workforce implications, and strategic risks if automation changes your competitive positioning.

4. Implementation Path: Consider phased implementation starting with lower-risk pilots rather than full-scale deployment. Determine success metrics for pilots that would justify broader rollout.

5. Vendor Evaluation: Assess vendor stability, team quality, roadmap credibility, support capabilities, and financial health. Consider whether you're comfortable betting on this company's long-term success.

Pilot Program Design

If you proceed with evaluation, design pilots carefully:

- Scope: Start with a specific, well-defined task in a contained environment rather than trying to automate your entire operation.

- Metrics: Define success metrics in advance. What level of reliability is required? What speed improvement justifies deployment? What worker feedback would indicate the system is acceptable?

- Support: Plan for close collaboration with vendors during pilots. You'll need engineers on site, you'll need to be willing to share data about failures, and you need to commit to working through problems rather than immediately abandoning the approach.

- Learning: The goal of a pilot is to learn whether this approach works for your operation and what challenges you'll face at scale. Treat it as experimentation, not a prove-it phase where you're only satisfied if everything works perfectly immediately.

The Broader Implications of AI-Powered Robotics

Economic Impact

If Physical Intelligence and similar companies succeed in creating genuinely flexible, affordable robotics systems, the economic implications are substantial. Industries currently relying on massive human labor forces—logistics, food service, healthcare, manufacturing—could experience significant productivity improvements.

Historically, such productivity improvements have eventually created new wealth that funds new industries and new jobs. But the transition periods are disruptive. Workers displaced from routine physical tasks need retraining for new roles. Communities built around industrial labor need economic transition support. Societies need to develop policies to ensure productivity gains benefit workers, not just capital owners.

Physical Intelligence's success, far from being just a company story, is actually a technology story with profound implications for how society organizes work and creates opportunity.

Labor Market Implications

The labor market for routine, repetitive physical work will diminish as robotics improve. This is bad news for workers currently in those roles but could be good news for labor economics overall if it forces wages for remaining human-required work higher and improves working conditions.

New labor demand will emerge for:

- Robot technicians and maintenance specialists

- Robot operators and supervisors

- AI trainers teaching robots new tasks

- Logistics and operations roles leveraging robotic systems

- Exception handlers dealing with situations robots can't manage

The net effect on employment depends partly on how quickly automation happens (faster means more dislocation) and partly on economic growth (strong growth creates new industries that absorb displaced workers).

Societal Considerations

Beyond economics, widespread deployment of robotics raises questions about safety, privacy, and control. Robots in human spaces need to be safe. Robots collecting data need to protect privacy. Robots making decisions need to be accountable. Physical Intelligence's success depends partly on their handling these considerations thoughtfully, not just on technical excellence.

Companies that think carefully about robot safety, that design systems with privacy protections built in, and that create clear accountability frameworks for robotic systems will build more trust with customers and regulators than companies that treat these as afterthoughts.

Conclusion: What Physical Intelligence Represents

Physical Intelligence is not just another robotics startup. It represents the maturation of ideas that have been developing in robotics and machine learning research for over a decade, finally achieving commercial viability through the convergence of three factors: sufficient computational resources, sufficient training data, and sufficient algorithmic advances.

Lachy Groom's decision to leave a comfortable life as a successful investor to build this company full-time reflects his conviction that the timing is genuinely right. The team—Sergey Levine, Chelsea Finn, Karol Hausman—brings decades of research credibility combined with practical deployment experience. Their approach of building generalized intelligence that compensates for imperfect hardware represents a genuine paradigm shift from traditional robotics thinking.

The company faces real challenges: technical risks around generalization, regulatory hurdles, market adoption uncertainties, and intense competition. But the problem they're solving—creating flexible, adaptable robotic systems that can work across diverse tasks and environments—is one of the most important problems in technology. Success here could unlock productivity gains across industries, reshape labor markets, and create a platform that becomes foundational to physical automation the way foundation models have become foundational to AI.

For organizations considering robotic automation, Physical Intelligence's eventual commercial offerings will be worth evaluating alongside traditional solutions. For investors and technologists, the company represents a compelling bet on whether foundation models can transfer from digital domains to the physical world. For society broadly, Physical Intelligence's success or failure will significantly influence whether automation benefits are widely distributed or narrowly concentrated.

The robots struggling to fold pants and peel vegetables aren't just experiments—they're the leading edge of a transformation in how physical work gets done. Whether you're an enterprise considering automation, an investor evaluating the robotics space, or simply interested in where technology is heading, Physical Intelligence deserves close attention. The intelligence layer they're building could prove as transformative to physical tasks as GPT has been to language tasks.

As Sergey Levine said, think of it like Chat GPT but for robots. The full implications of that analogy—the market opportunities, the displacement challenges, the economic restructuring—are just beginning to unfold. Physical Intelligence is positioned to be central to how that story evolves.

FAQ

What is Physical Intelligence and what problem does it solve?

Physical Intelligence is a robotics company building foundational AI models trained on diverse physical-task data, enabling robots to generalize across multiple tasks rather than requiring task-specific programming. The company solves the robotics industry's central challenge: how to create flexible, adaptable systems that can work across diverse environments and tasks, particularly in logistics, healthcare, manufacturing, and food service where labor shortages and task variation make traditional automation insufficient.

How do Physical Intelligence's foundation models differ from traditional robotics programming?

Traditional robotics uses task-specific programming where engineers write explicit code for each robotic task. Physical Intelligence trains general-purpose models on diverse physical-task examples, enabling robots to learn underlying principles of manipulation, force application, and task adaptation. This is analogous to how language foundation models like GPT understand language patterns from diverse text, allowing adaptation to new writing tasks without explicit reprogramming for each application.

What are the primary use cases for Physical Intelligence's technology?

Key applications include warehouse automation where robots adapt to varying package types and configurations, healthcare assistance where robots adapt to different patient needs and facility layouts, commercial kitchen automation including food preparation and espresso machine operation, and flexible manufacturing where robots reconfigure rapidly when product mix changes. The common thread is task variation and the need for robots to adapt rather than perform repetitive identical operations.

What makes Physical Intelligence's team and approach competitive?

The founding team includes Sergey Levine and Chelsea Finn, leading robotics learning researchers from UC Berkeley and Stanford with decades of published research, plus Karol Hausman from Google Deep Mind with industry deployment experience. Lachy Groom, a successful investor and Stripe veteran, brings execution expertise and understanding of platform scaling. Their approach prioritizes intelligence over hardware—using cheap off-the-shelf arms and letting advanced models compensate for hardware limitations—which enables faster iteration and scaling than hardware-first approaches.

What is the timeline for Physical Intelligence's commercial deployment?

The company is currently in the test and deployment phase with early customer installations generating real-world data. Based on typical AI company timelines, broader commercial availability for the specific systems Physical Intelligence develops probably occurs over the next 2-3 years, with market penetration accelerating if early customer results validate the approach. However, timelines are uncertain and depend on technical progress, regulatory approvals, and customer adoption rates.

How do Physical Intelligence systems handle situations they haven't been trained on?

Foundation models exhibit transfer learning capabilities—they can adapt to situations similar to their training distribution by applying learned principles to new scenarios. However, they're not infinitely flexible. Actions far outside the training distribution may fail, requiring human intervention. The company's approach involves continuous learning where failures generate data that improves models, plus careful selection of training diversity to ensure broad generalization. Early deployments will probably include human oversight for exception handling.

What infrastructure do enterprises need to deploy Physical Intelligence systems?

Organizations need reliable network infrastructure for robot connectivity and model updates, data infrastructure for processing robot-generated data, integration capabilities to connect robots with existing operational systems like warehouse management or manufacturing execution systems, physical space for robot charging and maintenance stations, and trained personnel to operate and monitor robotic systems. Safety infrastructure for human-robot collaboration is also essential.

How does Physical Intelligence's approach compare to humanoid robotics development?

Physical Intelligence uses standard industrial robot arms optimized for cost and standardization, betting that intelligence can compensate for non-humanoid form factors. Humanoid robotics companies like Tesla Optimus and Boston Dynamics develop human-shaped robots that can navigate human spaces and use human tools. Physical Intelligence's approach enables faster data collection and iteration; humanoid approaches offer greater flexibility across diverse environments. Both could ultimately succeed in different applications.

What risks could prevent Physical Intelligence's successful commercialization?

Key risks include model generalization failures where systems don't adapt as well as hoped outside training distribution, regulatory challenges for robots in human spaces, slower-than-expected market adoption due to customer risk aversion or integration challenges, and intense competition from established roboticists companies and other AI-focused startups. Additionally, labor market and policy responses to automation could create headwinds, and the timeline to profitability depends on moving faster than competing approaches.

How should enterprises evaluate whether Physical Intelligence's technology fits their needs?

Organizations should assess whether their automation tasks involve sufficient variation to justify flexible systems, develop detailed ROI models including all implementation and training costs, identify specific regulatory or safety requirements their robots must meet, and consider phased pilots in controlled settings before broader deployment. They should evaluate Physical Intelligence's team, financial stability, roadmap credibility, and support capabilities. Finally, they should be honest about their risk tolerance and ability to invest in change management as robots augment or replace human workers.

What broader implications might Physical Intelligence's success have?

If successful, Physical Intelligence could unlock significant productivity improvements in logistics, healthcare, manufacturing, and food service industries currently dependent on human labor. Economically, this could create new wealth but also cause labor market disruption requiring workforce retraining. Societally, it raises questions about safety, privacy, and accountability for autonomous physical systems. The technology could reshape how work is organized and create entirely new categories of work around robot management and exception handling.

Key Takeaways

- Physical Intelligence applies foundation model approach to robotics, enabling flexible adaptation across tasks rather than single-task specialization

- Team includes decades of published robotics research (Levine, Finn) combined with execution expertise (Groom's Stripe background and track record investing in scaled platforms)

- Key innovation is training general models on diverse real-world task data, betting that intelligence compensates for imperfect hardware

- Near-term applications include warehouse automation, healthcare assistance, commercial kitchen operations, and flexible manufacturing

- Enterprise adoption requires infrastructure planning, integration capabilities, regulatory compliance, and thoughtful workforce transition strategies

- Competitive landscape includes traditional robotics companies, specialized startups, humanoid robotics platforms, and service-based automation models

- For software automation needs, platforms like Runable offer complementary AI-powered solutions at different scales ($9/month automation and workflow tools)

- Timeline to commercial deployment likely 2-3 years, with adoption acceleration dependent on early customer success validation