The $408,000 Bet That Exposed Prediction Markets' Darkest Secret

Last week, something happened on a prediction market that shouldn't happen anywhere: someone made nearly half a million dollars betting on a major geopolitical event, right before it occurred. The timing wasn't luck. The account was brand new. The money appeared the day before a US military operation that most people didn't know was coming. And when the event unfolded exactly as the bet predicted, nobody involved seemed particularly concerned about what this revealed about how these markets actually work.

This isn't a story about one lucky trader. It's a story about an entire ecosystem built on information asymmetry, where people with access to classified government intelligence can place bets against people who have no idea those bets are coming.

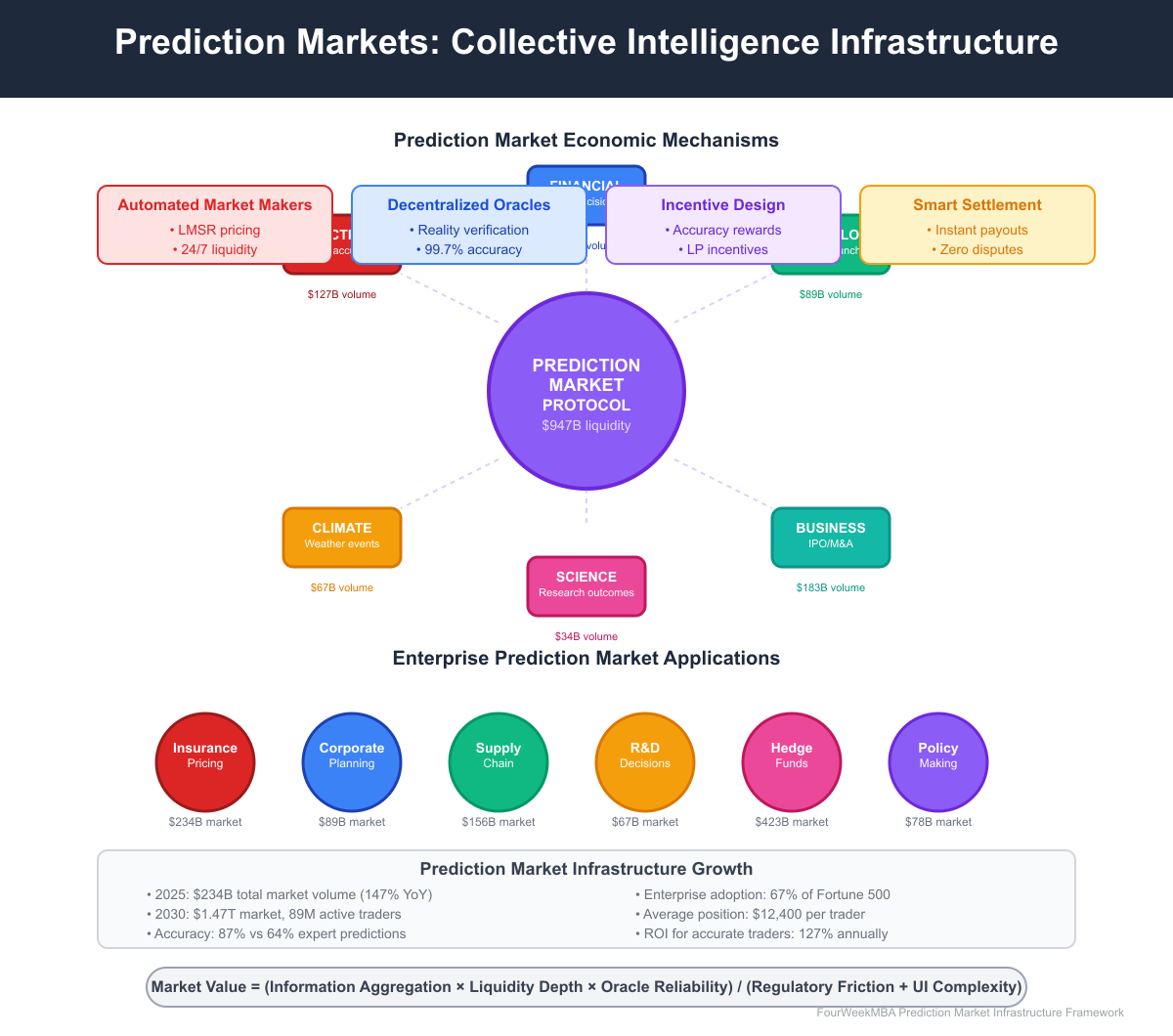

Prediction markets have become a multi-billion dollar phenomenon. Platforms like Polymarket, Kalshi, and others promise to harness the collective intelligence of crowds to forecast everything from election outcomes to corporate earnings to geopolitical events. They've attracted billions in trading volume, mainstream media coverage, and serious venture capital backing. Presidential candidates have promoted them. Silicon Valley treats them like the future of information markets.

But last week revealed something that crypto insiders and market observers have quietly known for years: these platforms are rotten with insider trading. And worse, the companies running them don't care.

Here's what we know about what happened, how it reveals systemic problems in prediction markets, why these platforms are essentially allowing legalized insider trading, and what it means for an entire industry betting on the idea that decentralized markets are incorruptible.

TL; DR

- A new Polymarket account invested 408,000 in profits

- The account was created less than a week before the bet, suggesting someone with foreknowledge of classified military operations was trading on that information

- Prediction market platforms actively encourage insider trading, viewing it as a feature, not a bug, because it attracts informed traders and provides liquidity

- Similar incidents have occurred repeatedly on platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket, with companies showing consistent indifference to obvious insider trading

- The lack of regulation and enforcement creates a system where access to classified government information becomes a direct profit opportunity

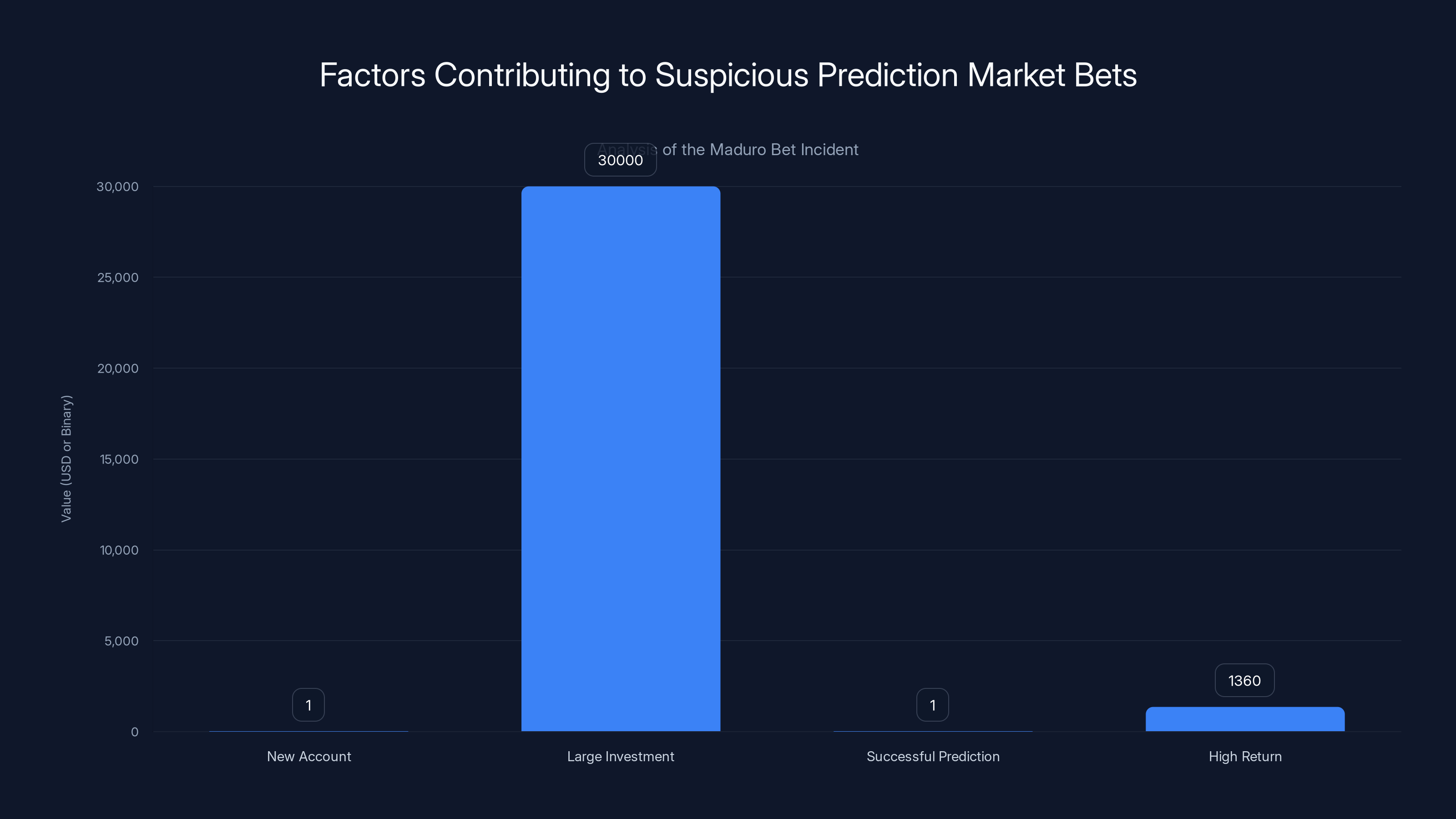

The Maduro bet was suspicious due to a combination of a new account, a large $30,000 investment, a successful prediction, and a 1,360% return, suggesting possible insider trading.

The Timeline That Doesn't Add Up

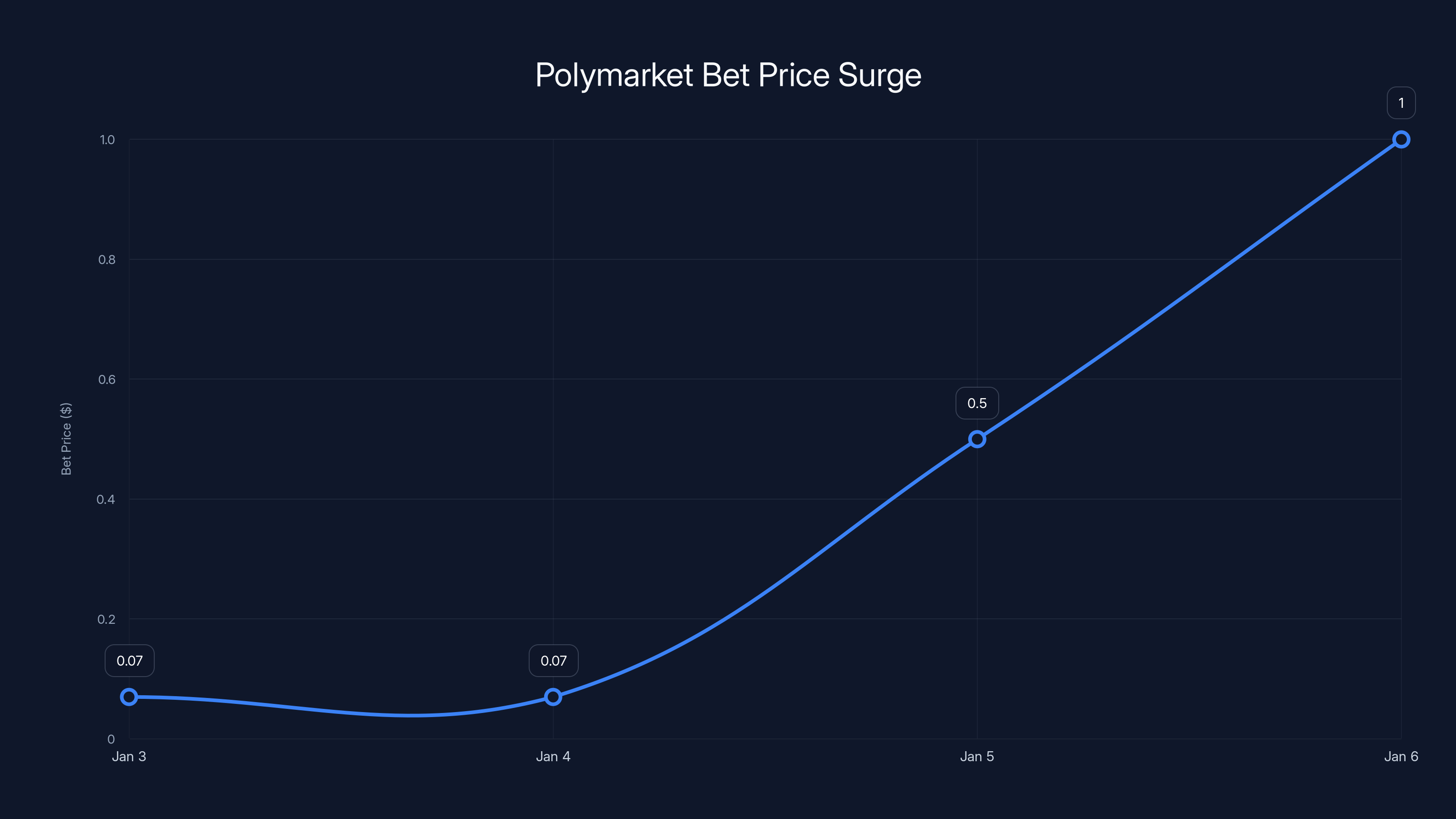

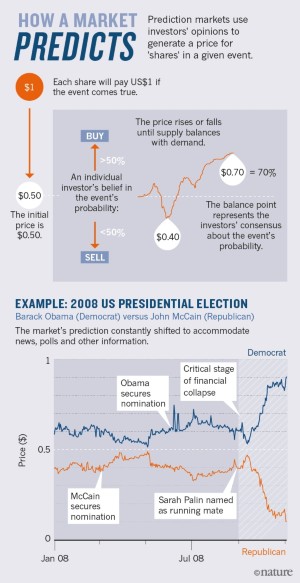

On the surface, the numbers are simple. On Friday evening, January 3rd, 2026, bets on Polymarket that Nicolás Maduro would be "out by January 31, 2026" were trading at around $0.07 per share. This meant the market believed there was roughly a 7% chance Maduro would be removed from power within the next month.

That's already suspicious. Why would the market price this at 7% when Venezuela's political situation had been relatively stable? What information were traders responding to?

But here's where it gets weird. Within 24 hours of those Friday evening prices, a newly created account dumped tens of thousands of dollars into these same bets. The account was brand new—created less than a week before the trades. No trading history. No reputation. No reason to trust this account existed.

The person running this account invested

That's a 1,360% return in two days.

Let's pause on that number. A 1,360% return in 48 hours isn't investing. It's not market timing. It's not research or analysis or good judgment. That's not how markets work for anyone except people who know something nobody else knows.

The specifics matter here. The account wasn't just betting on "Maduro eventually gets removed." It was betting on a specific timeframe: "by January 31, 2026." That's a narrow window. Someone had to believe Maduro's removal would happen within the next four weeks. And they had to believe it strongly enough to risk over $30,000.

Then the military operation happened. And they were right.

This isn't a coincidence. This is what insider trading looks like. Someone with access to classified information—likely about planned military operations—used that information to make a guaranteed profit on a betting platform that was supposed to aggregate the wisdom of informed crowds.

How Prediction Markets Became an Insider Trading Playground

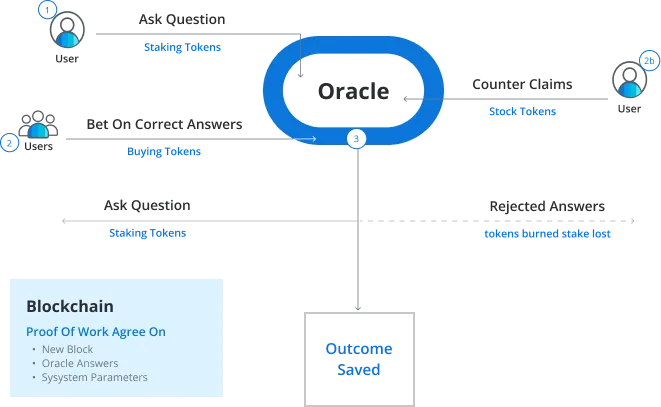

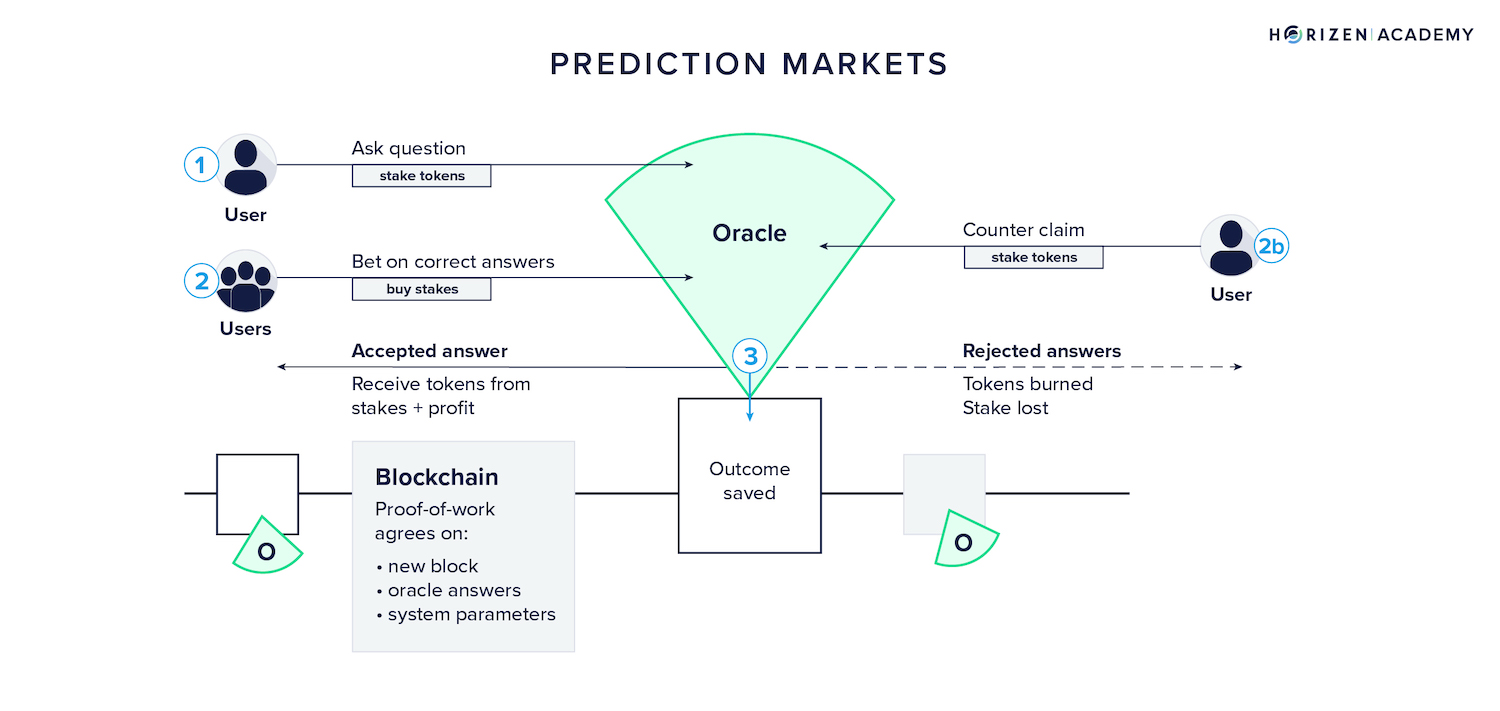

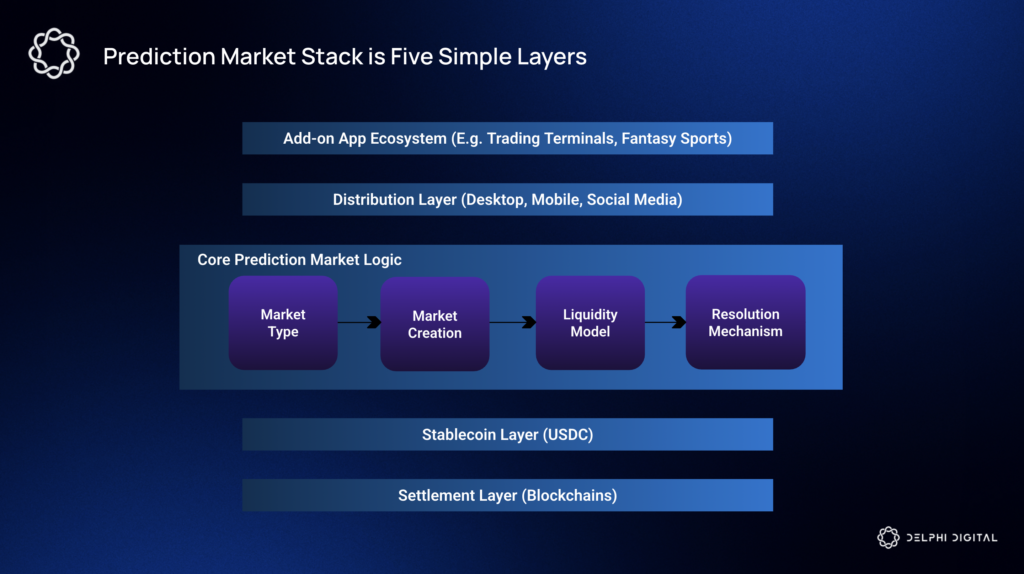

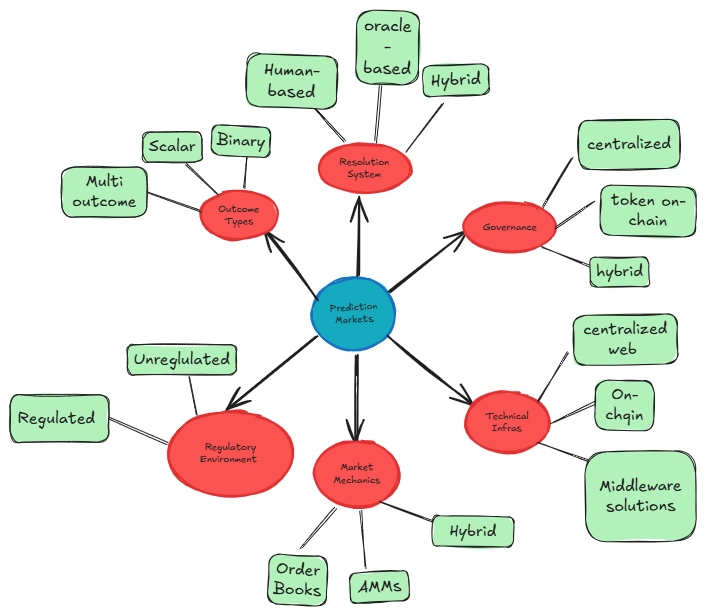

Understanding how we got here requires understanding what prediction markets actually are and why they're so vulnerable to abuse.

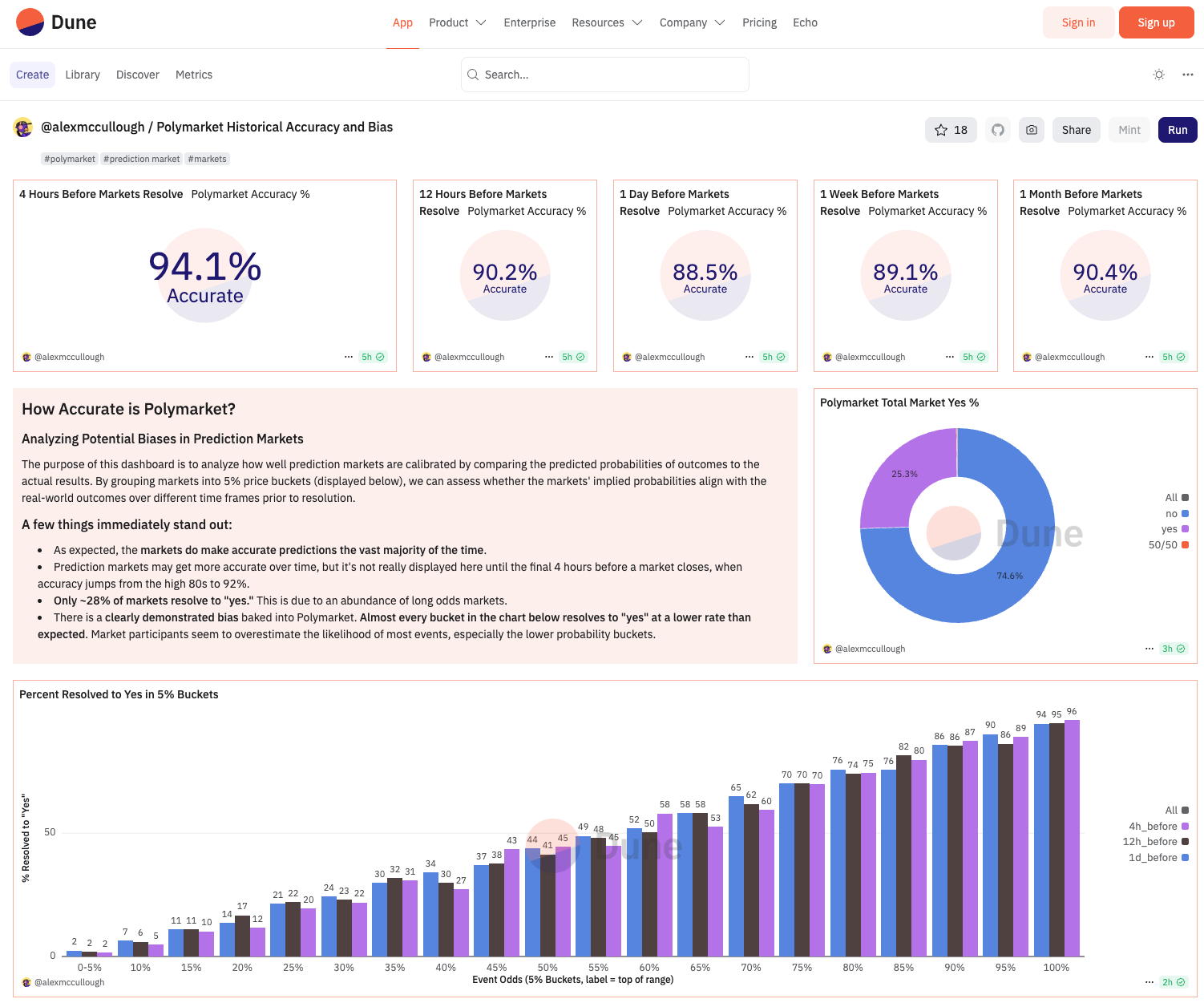

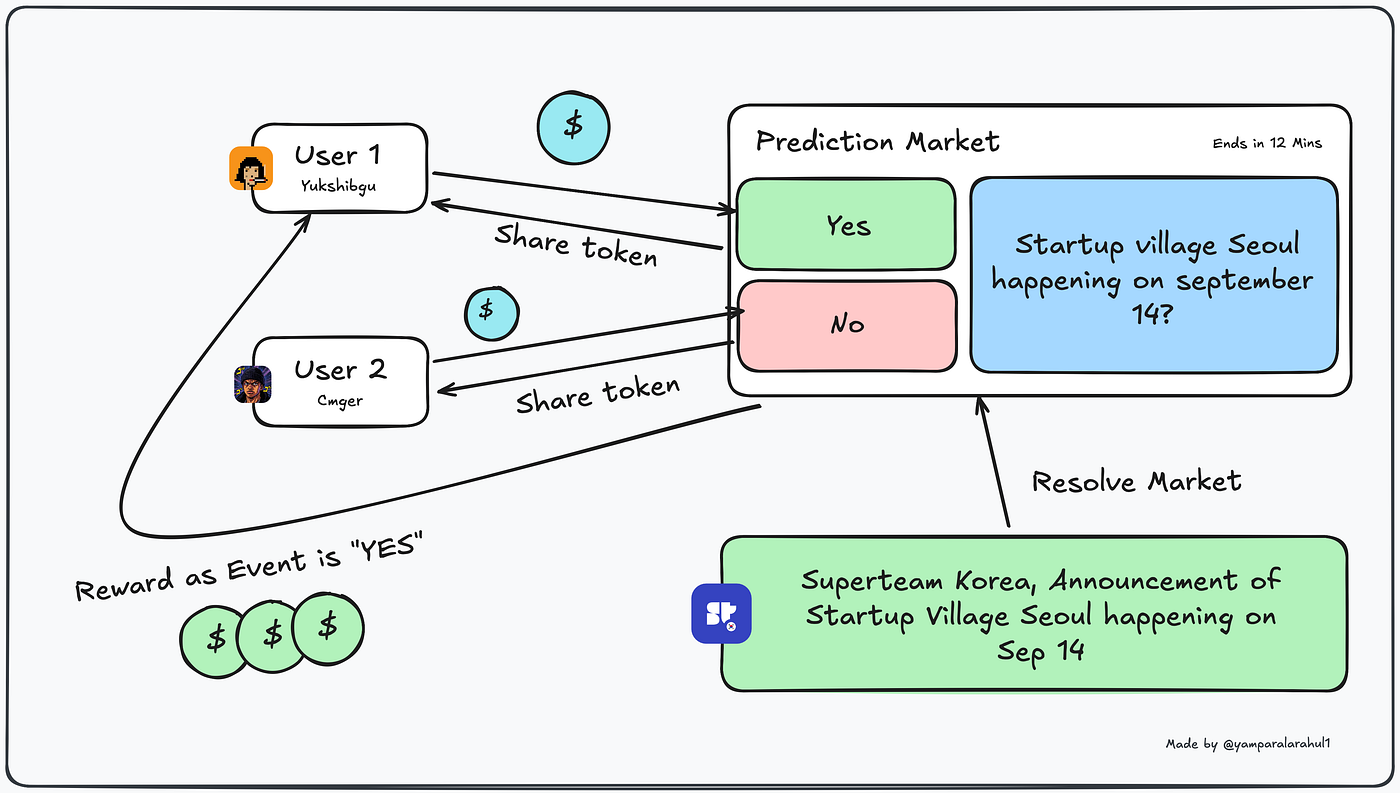

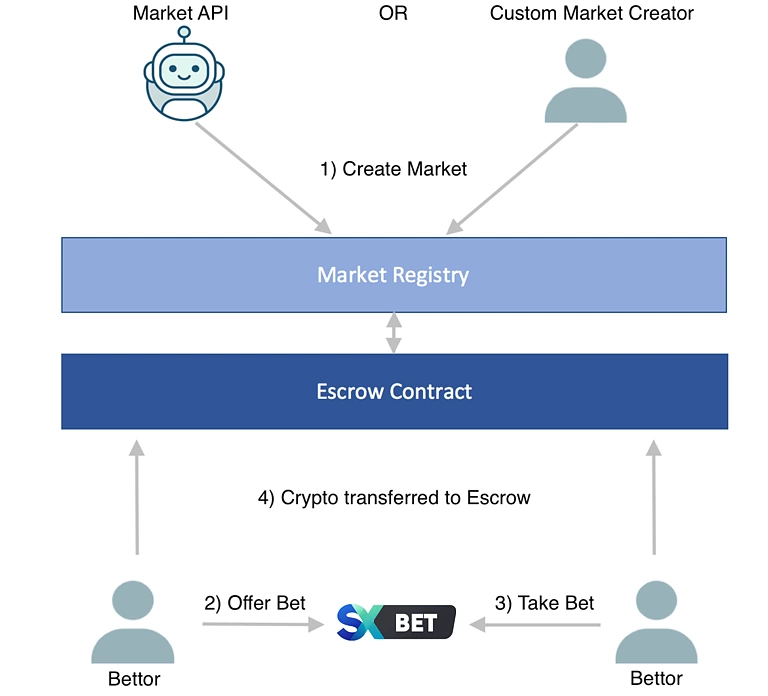

Prediction markets function on a deceptively simple premise: create a marketplace where people can buy and sell contracts based on future outcomes, and the market price of those contracts will reflect the crowd's true belief about what will happen. Want to know the probability of a recession? Look at the price of recession contracts. Want to predict election outcomes? Check the market price of candidate contracts.

In theory, this creates incentives for informed traders to participate. If you have genuine insight into what will happen, you can profit by trading against less-informed participants. This should attract people who actually know things—analysts, experts, people with deep research. The theory says competition between informed traders will gradually push prices toward the true probability of events.

It sounds elegant. In practice, it creates a system that actively rewards insider trading and then pretends to be shocked when it happens.

Here's the fundamental problem: prediction markets don't distinguish between different types of information. They don't care whether your insight comes from careful research and analysis or from a classified Pentagon briefing. A profitable trade is a profitable trade. From the platform's perspective, both are equally valuable.

In fact, platforms arguably prefer informed traders—including those trading on inside information—because informed traders provide liquidity and make markets more efficient. This is actually a feature of how prediction markets are designed. They want people who know things to trade. The more informed the traders, the better the market supposedly works.

But this creates a massive perverse incentive. Government employees, military strategists, diplomats, intelligence officials—people with systematic access to classified information—have genuine information advantages in certain markets. They know whether military operations are planned. They know about economic policy decisions before they're announced. They know about regulatory changes before they're public.

And prediction markets give them a direct mechanism to profit from that information.

Multiple former officials and policy experts have pointed out the obvious conflict here. You're creating a situation where someone working in the Pentagon can literally make six figures by betting on outcomes of military operations they're helping plan. You're incentivizing people with classified information to participate in these markets.

The response from prediction market companies has been consistent: we don't care. Or more specifically, as one investor quoted in coverage of similar incidents pointed out: insider trading isn't just allowed on prediction markets—it's encouraged. The platforms frame this as a feature of how decentralized and efficient markets work. They celebrate the fact that informed traders can profit.

Federal employees could potentially earn significantly more from insider trading than from their salaries, with single trades yielding up to

Previous Insider Trading Incidents: A Pattern of Indifference

The Maduro bet isn't the first time this has happened. It's not the second. There's a consistent pattern of obvious insider trading on prediction markets, followed by platform indifference, followed by the next obvious insider trade.

Consider the track record. Kalshi, another major prediction market platform, has fielded bets about economic data before that data was released. Someone with access to the actual economic data—potentially a government employee—placed bets that turned out to be suspiciously accurate. The timing suggested advance knowledge.

Polymarket has seen similar incidents. Bets have been placed on outcomes of elections and political events with timing and precision that suggested someone involved in those processes had leaked the information or was trading on their own knowledge.

In virtually every case, when these incidents have been reported, the platform response has been to shrug. Sometimes they've acknowledged the trade. Occasionally they've expressed mild concern. But the actual response—banning accounts, investigating whether the trader had access to classified information, implementing detection mechanisms for suspicious trades—that doesn't happen.

Polymarket and Kalshi have both received inquiries about these incidents. When asked for comment on insider trading specifically, platforms tend to give variations of the same response: this is how markets work. Informed traders have advantages. That's not a bug, it's a feature.

One way to think about this: if a hedge fund placed all its trades on the stock market based on information stolen from government agencies, that would be a federal crime. The trader would face prison time. The fund would face massive penalties. SEC enforcement would be severe and public.

But on prediction markets, the exact same activity—trading on classified government information—is presented as the market functioning as intended.

This is partly because prediction markets exist in a regulatory gray zone. They're not officially recognized as financial markets the way traditional stock exchanges are. They operate under different rules. Some operate in other countries specifically to avoid US regulation. They're not subject to the same SEC oversight as traditional markets. There's debate about whether they even fall under insider trading statutes.

But it's also partly because the platforms have made a calculated decision: they would rather have loose rules that allow insider trading than strict rules that might reduce overall trading volume. More traders, even if some of them are trading on classified information, means more liquidity, more volume, more fees, more platform growth.

Inside Information as a Commodity: How Federal Employees Became Traders

To understand why this keeps happening, you need to understand the incentives involved.

Let's say you're a mid-level employee at the State Department. You make maybe

Now someone points you toward Polymarket. You create an account under a different name, fund it with cryptocurrency that's harder to trace, and you start placing bets on outcomes you know are coming. A military operation you know about. A diplomatic agreement you're helping negotiate. A policy decision that will be announced next month.

Suddenly, you're not making

And the platform doesn't care. The government hasn't prosecuted anyone. There's no detection mechanism. There's no real way to get caught.

From an incentive structure perspective, this is catastrophic. You've created a system where the best way to profit is to have access to classified information. You've given federal employees—people who are trusted with national security information—a direct mechanism to monetize that trust.

You've essentially made insider trading part of the federal benefits package.

The platforms claim they can't do anything about this because they don't know who's behind the accounts. Users can be pseudonymous or anonymous, funded with cryptocurrency, operating across jurisdictions. But this is a choice platforms made. They could implement know-your-customer requirements. They could flag suspicious trades that match the timing of government announcements. They could report suspicious activity to relevant authorities.

They don't. They won't. Because doing so would reduce the participation of "informed traders"—which is platform-speak for people trading on information advantages, many of which are illegally obtained classified information.

Why Regulation Has Failed to Keep Up

Regulatory agencies are years behind on this issue. The SEC has primary jurisdiction over insider trading in traditional markets, but prediction markets operate in a genuinely ambiguous space.

Traditional insider trading rules apply to "securities" traded on regulated exchanges. Prediction market contracts might not technically qualify as securities. Many prediction market platforms are incorporated outside the US specifically to avoid SEC jurisdiction. The legal framework for what counts as illegal insider trading on these platforms is genuinely unclear.

This isn't an accident. Platform founders and early advocates deliberately set up these markets in legal gray areas. They argued that prediction markets should be regulated differently because they're not really financial instruments, they're information markets. The trades aren't about moving money around—they're about aggregating information.

That argument was always intellectually dishonest. People trade prediction markets for money. They profit from correctly predicting outcomes. That's financial trading, regardless of how you frame it. But the legal ambiguity gave platforms plausible deniability.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department doesn't have clear protocols for investigating insider trading on prediction markets. Are these federal crimes? Do they fall under the Espionage Act because classified information is being traded on? Is it wire fraud? The legal framework is muddled.

By the time regulators figure out the legal basis for enforcement, there will have been billions of dollars in trades that potentially violated insider trading statutes. Thousands of federal employees will have made unauthorized profits from classified information. And the platforms will have become too large and too politically connected to shut down.

This is a classic regulatory arbitrage situation: platforms operate in legal gray areas specifically because regulations haven't caught up. Enforcement lags behind innovation. By the time the legal framework clarifies, the market is already established.

The investment in the Maduro trade saw a dramatic increase in return, reaching 1,360% within 48 hours due to insider knowledge. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Maduro Trade: A Case Study in Perfect Timing

Let's zoom back in on the specific details of the Maduro bet, because the specifics tell you exactly how this insider trading works in practice.

The bet was on a very specific outcome: Maduro would be "out" by January 31, 2026. Not eventually. Not someday. By a specific date four weeks away. That's a narrow prediction window.

On Friday evening, January 3rd, the market was pricing this at about 7%. That's how much the crowd thought this was likely. The market had no special information. There was no particular news that day suggesting Maduro's removal was imminent.

But someone did have special information. Someone knew a military operation was being planned. Someone knew it would happen within days. Someone had high-level knowledge of classified military operations.

And that someone couldn't have gotten a better opportunity to profit.

The timing is almost absurdly perfect. The account was created less than a week before the bet. It made its major trades the day before the operation. The operation succeeded exactly as this person apparently knew it would. Within 48 hours, the investment had returned 1,360%.

There's a reason the trading community immediately flagged this on social media. This isn't ambiguous. This isn't a lucky guess or good research. This is someone who knew what was going to happen and bet accordingly.

Several investors and market commentators pointed out the obvious: if you see a pattern like this in traditional markets, federal prosecutors would be investigating within weeks. A brand new account dumping tens of thousands of dollars into a highly specific bet, followed by perfect accuracy about classified military operations, followed by massive profits—that's textbook insider trading.

On Wall Street, that trader would be facing federal charges. On Polymarket, nobody cared. The platform processed the trade. The profits were legitimate. Moving on.

Who Benefits From This System? (It's Not You)

When platforms defend insider trading on prediction markets, they use abstract arguments about market efficiency and information aggregation. But let's be concrete about who actually benefits.

The people who benefit: federal employees with access to classified information. Government officials. Military strategists. Intelligence community members. Anyone with systematic access to non-public information about outcomes prediction markets care about.

The people who lose: everyone else participating in these markets. Individual traders placing bets based on public information. Casual users trying to predict election outcomes or economic data. Anyone betting against someone who has access to classified information.

When a federal employee with access to military intelligence bets against you on a prediction market, you're not competing in a fair game. You're betting against someone who literally knows what's going to happen. You're going to lose.

Platforms will tell you that's how markets work—informed traders have advantages. Sure. But there's a difference between having better research or better analysis and having access to classified government information. The former is investing. The latter is fraud.

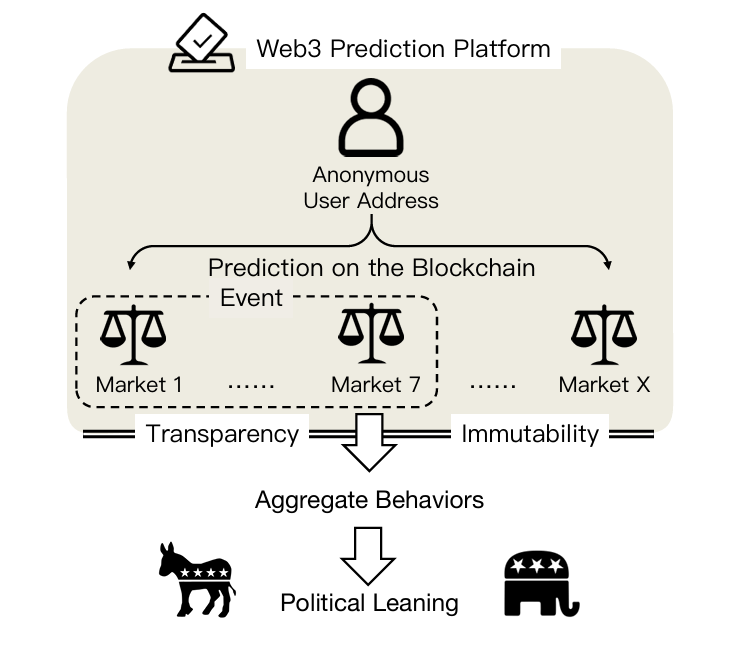

Prediction markets have positioned themselves as the future of how we aggregate information and make decisions. They've attracted serious venture capital, mainstream adoption, attention from policymakers. Some people have suggested using them to make actual government decisions because they're supposedly so good at predicting outcomes.

But if those markets are systematically infiltrated by people trading on classified information, they're not predicting anything. They're just showing us what federal employees know about what's going to happen. That's not wisdom of crowds. That's information leakage from government.

And it should terrify policymakers who are considering using these markets for anything important.

The Cryptocurrency Connection: How to Hide Your Identity

Part of what makes this possible is cryptocurrency. The Maduro trade was likely funded with crypto, moved through anonymous wallets, and then deposited on Polymarket in a way that makes it hard to trace back to any specific person.

Traditional financial platforms have know-your-customer requirements. You want to open a brokerage account? You need to provide ID, proof of address, source of funds. There's a paper trail. Regulators can follow the money and figure out who's trading.

Prediction markets don't require this, partly because many are built on blockchain and crypto-friendly infrastructure. You can fund a Polymarket account with crypto, remain pseudonymous, and trade without anyone knowing who you are.

This isn't a coincidence. The crypto-prediction market combination was deliberately created to enable exactly this kind of activity. The founders believed these tools should be decentralized and anonymous. They opposed traditional financial regulation. They wanted systems where you could trade without revealing your identity.

Those are great ideals if you believe finance should be beyond regulatory reach. They're catastrophic ideals if you're concerned about insider trading, market manipulation, and fair access to markets.

What crypto enables is a way for someone to take classified information, convert it into profits on an anonymous account, and then move those profits out of the prediction market platform back into cryptocurrency, all without anyone being able to draw a clear line from "federal employee with access to classified military information" to "person who profited from that information."

The Maduro trader likely did something like this: received cryptocurrency funding from a source that could be explained as personal savings or crypto holdings, moved it through several wallets to obscure its origin, deposited it on Polymarket under a pseudonymous account, made trades, and would have withdrawn profits back into crypto—all of which is basically untraceable if law enforcement isn't specifically investigating you.

Traditional insider trading is prosecutable partly because of the paper trail. The SEC and DOJ can follow your bank transfers, your brokerage statements, your communications about the trades. Crypto and anonymous platforms make all of that much harder.

The price of bets on Maduro's removal surged from

What Prediction Market Companies Actually Say (And What They're Not Saying)

When asked about insider trading, Polymarket and Kalshi tend to give similar responses. They say they're monitoring for suspicious activity. They say they have compliance teams looking at unusual trades. They say they're working with law enforcement when required.

But they also consistently defend the principle that informed traders should be able to trade. They argue that insider trading is priced into market efficiency—that markets work better when informed traders participate because it moves prices toward accurate predictions faster.

This is partly true in traditional markets. If insider trading is happening, market prices do reflect that information faster than they would otherwise. But that's a descriptive claim about how markets work, not a normative argument for why insider trading should be allowed.

The platforms frame this as: "We're not encouraging insider trading, we're just acknowledging that informed traders improve market efficiency." But acknowledging a problem and refusing to address it is effectively the same as encouraging it.

Neither platform has announced policies to aggressively investigate or prosecute insider trading. Neither has implemented the kind of detection systems that traditional exchanges use. Neither has committed to reporting suspicious activity to law enforcement without being compelled to do so.

When asked specifically about the Maduro trade, both platforms initially declined to comment. When they eventually responded, they gave vague statements about monitoring for suspicious activity but avoided committing to any specific investigation or enforcement action.

The message is clear: insider trading is happening, we see it, we're not going to seriously investigate it, and we definitely aren't going to shut down accounts or reverse trades based on it.

The Regulatory Gap: Why This Will Keep Happening

Until there's clear law and enforcement, insider trading on prediction markets will continue at scale.

The regulatory gap has several components. First, there's uncertainty about whether prediction market trades even fall under existing insider trading statutes. Traditional insider trading law applies to trading on material nonpublic information about securities. But are prediction market contracts securities? Different legal scholars argue different positions. Until a court definitively answers the question, prosecutors are hesitant to bring cases.

Second, prediction markets operate across borders and on decentralized platforms in ways that traditional markets don't. If a platform is incorporated in the Cayman Islands, does the SEC have jurisdiction? If trades happen on a blockchain-based system without a central clearing house, how do you even pursue enforcement? The legal infrastructure for regulation doesn't exist yet.

Third, there's a genuine lack of law enforcement resources focused on this issue. The SEC has limited resources and traditionally focuses on major stock market manipulation rather than niche prediction markets. Federal prosecutors in different jurisdictions have varying levels of interest in crypto-related financial crimes.

The combination of legal uncertainty, jurisdictional complexity, and resource limitations creates a environment where insider trading can happen openly and nobody faces consequences.

What Should Happen vs. What Will Happen

Ideally, a situation like the Maduro trade would trigger immediate regulatory action. Law enforcement would investigate who placed the bet. They'd look at whether this person had access to classified military information. If so, they'd pursue insider trading charges under the appropriate statutes. The SEC would issue clear guidance about prediction market regulation. Congress would hold hearings.

There would be real consequences: individuals would face prosecution, platforms would be forced to implement compliance systems, and future insider trading would be deterred.

But that's the ideal outcome. The likely outcome is different.

What will probably happen: platforms will issue vague statements about "enhanced monitoring." There will be no criminal charges against the trader. Law enforcement will either decline to pursue it (citing jurisdictional or legal uncertainty) or pursue it quietly without much public information. Platforms will continue operating exactly as before. Similar trades will happen again. The cycle will repeat.

This will continue until either: a major political or public relations scandal forces Congress to act, a federal judge rules that insider trading statutes clearly apply to prediction markets, or law enforcement makes an example of someone with a particularly egregious trade—prosecuting them as a warning to others.

None of these seem imminent. Platforms have smart lawyers. Law enforcement is overextended. Congress moves slowly on financial regulation. And the prediction market industry has attracted enough venture capital and Silicon Valley support that defending it against regulation is well-funded.

So the status quo will persist: prediction markets will remain largely unregulated, insider trading will continue to happen openly, and federal employees will continue to profit from classified information with impunity.

Platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket often acknowledge insider trading incidents but rarely take concrete actions. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Bigger Problem: Should These Markets Exist at All?

Zoom out and there's a larger question: do we want prediction markets to exist in their current form?

The argument for prediction markets is straightforward: they aggregate information effectively, they provide genuine insights into what informed crowds believe about future events, and they're useful tools for understanding probability and managing uncertainty.

All of that's true in theory. In practice, prediction markets are becoming increasingly useful as tools for extracting profits from information asymmetry and insider knowledge rather than as tools for aggregating genuine collective intelligence.

If these markets primarily attract informed traders—and if a significant portion of "informed traders" are trading on classified or otherwise illegally obtained information—then they're not aggregating crowd wisdom. They're aggregating intelligence from people with information advantages they shouldn't have.

That changes what the markets are for and who benefits from them. Instead of tools for understanding probability, they become tools for monetizing classified information and creating profit opportunities for government employees with access to sensitive data.

Some countries and regulatory bodies are reaching the conclusion that prediction markets as currently structured shouldn't exist. The EU has moved toward restricting them. Some US regulators have expressed skepticism about their value. There's growing recognition that markets built on information asymmetry and insider knowledge are not the neutral, efficient information tools they're marketed as.

But in the US, the prediction market industry has positioned itself as part of the broader tech and crypto ecosystem that opposes regulation and argues for minimal oversight. That political alignment has been effective in blocking regulatory action so far.

How This Connects to Broader Crypto and Finance Issues

The Maduro trade isn't just about prediction markets. It's part of a broader pattern of how crypto and decentralized finance are being used to circumvent traditional financial regulation.

Crypto was originally marketed as a system beyond government control, where transactions couldn't be censored and individuals could have financial autonomy. What it's actually become—in large part—is a system for conducting financial activities that would be illegal on regulated platforms: money laundering, sanctions evasion, fraud, and yes, insider trading.

Prediction markets are just one application. You see the same pattern across crypto: platforms and systems designed to bypass regulation, which then get used for illegal activity, which the platforms argue they can't prevent because they're decentralized.

The Maduro trade is an example of how these systems enable specific federal crimes (trading on classified information) while maintaining plausible deniability because the platforms claim they can't identify users or monitor activity.

It's also an example of how the promise of "decentralization" and "no censorship" becomes, in practice, "no enforcement of illegal activity."

That's fine if you're ideologically opposed to financial regulation. But if you believe insider trading should be illegal—and most people do—then systems that enable insider trading while making enforcement nearly impossible represent a real problem.

The Response From the Prediction Market Community

Like any industry facing criticism, the prediction market community has developed defensive talking points.

They argue that insider trading is impossible to prevent completely on any market. Fair point. But that doesn't mean platforms should be indifferent to it.

They claim they can't identify users because of pseudonymity. True. But they could implement optional know-your-customer verification for users making large trades, flag accounts that show suspicious trading patterns, and cooperate with law enforcement investigations more aggressively.

They contend that insider trading improves market efficiency. Technically true, but that's not an argument for why it should be allowed, any more than the fact that heroin produces a high is an argument for why it should be legal.

They point out that the Maduro trade isn't proof of insider trading, just suspicion. Fair—nobody has direct evidence of what the trader knew. But the timing, the newness of the account, the investment size, and the accuracy of the prediction create a circumstantial case that's strong enough to warrant investigation. The absence of investigation isn't absolution of guilt.

Overall, the prediction market industry's response has been to defend the status quo against critics while making only cosmetic changes to compliance. They're betting—ironically, given what their platforms do—that regulatory attention will lag behind market growth and they can remain largely unregulated.

So far, that bet is paying off.

Insider trading is perceived to have the highest negative impact on trust in prediction markets, followed by the effectiveness of information aggregation. Estimated data.

What This Means for Cryptocurrency and Finance More Broadly

The Maduro trade is a test case for a broader question: can we trust decentralized or cryptocurrency-based financial systems to police themselves against illegal activity?

The answer so far appears to be no. When platforms are decentralized, pseudo-anonymous, and designed specifically to avoid traditional regulation, illegal activity flourishes. Platforms claim they can't prevent it, don't have the infrastructure to monitor it, and shouldn't be expected to regulate users.

But that's a choice. Platforms could implement more sophisticated compliance systems. They could require greater identity verification. They could flag suspicious activity and cooperate with investigators. Most traditional financial institutions do this because they face regulatory requirements.

Prediction markets choose not to do this because they believe it would reduce user participation and trading volume. They're making a calculation that accepting some level of insider trading and other illegal activity is worth the benefits of remaining a pseudonymous, minimally-regulated platform.

That calculation might be right from a business perspective. It's definitely wrong from a public policy perspective.

One of the promises of crypto and decentralized finance was that we could build systems that were both more efficient and more trustworthy than traditional finance. We'd eliminate intermediaries and their corruption. We'd move to systems based on transparent algorithms and open participation.

What's happened instead is we've built systems that are more efficient at certain things (moving money quickly, avoiding regulatory scrutiny) but less trustworthy when it comes to preventing fraud and illegal activity. We've removed guardrails without replacing them with alternatives.

The Maduro trade exemplifies this perfectly. A decentralized platform, designed to be regulation-resistant, ends up being fraud-resistant too in the opposite way: it enables fraud while making enforcement impossible.

What Happens Next

In the immediate term, probably nothing changes. The Maduro trade will fade from headlines. Polymarket and Kalshi will continue operating as they do now. The trader will keep their $408,000 in profits. Similar insider trading will happen again, and other traders will start looking for their own information advantages on these platforms.

In the medium term, there might be regulatory attention, but it will likely move slowly. Congress might hold hearings. The SEC might issue guidance. But actual enforcement actions and regulatory frameworks will take years to develop. By then, prediction markets will be even more entrenched.

In the long term, prediction markets face a genuine question about their legitimacy. If they become known primarily as tools for people with information advantages to profit at the expense of regular traders, their claimed value as information aggregation tools collapses. They become less useful for forecasting and understanding probability, more useful as vehicles for insider trading.

At some point, that becomes unsustainable. Either platforms implement real compliance measures and genuine enforcement, or they become marginalized as tools that nobody trusts because they're known to be infiltrated by insiders.

My guess is prediction markets will muddle through the middle ground: making some cosmetic compliance changes while remaining fundamentally unregulated, accepting insider trading as part of their business model, and attracting sophisticated traders who understand that information advantages are where the real profits are.

That outcome is worse than either alternative. It's worse than heavy regulation because insider trading keeps happening quietly. And it's worse than full deregulation because there's pretense of compliance that gives platforms cover while doing nothing to prevent fraud.

But it's probably the most likely outcome, because it's the path of least resistance for both regulators and platforms. It's easy for platforms to claim they're monitoring when they have no intention of taking action. It's easy for regulators to claim they're developing enforcement when doing so is complex and resource-intensive. And it's easy for insider traders to keep operating because nobody is seriously trying to stop them.

The Maduro trade was a warning. Nobody listened.

The Broader Implications for Trust in Markets

Beyond prediction markets specifically, the Maduro trade raises questions about trust in any market that claims to aggregate information or predict outcomes.

If we're using prediction markets to inform policy decisions, as some have suggested, we need to know whether those markets are actually reflecting genuine probability assessments or just showing us what people with information advantages happen to know.

The difference matters enormously. A market price of 7% for "Maduro out by January 31" could mean two things: either the crowd genuinely believed this had a 7% chance (in which case the market was wrong and we can learn from that failure), or the crowd didn't have enough information to properly price this event and insider traders kept their knowledge hidden until the last moment (in which case the market was never providing useful information to begin with).

If prediction markets are infiltrated with insider traders, then their value as information aggregation tools collapses. They're not showing us what the crowd knows. They're showing us what people with information advantages know.

For policymakers considering using prediction markets to inform decisions, that's a crucial distinction. A market that properly aggregates crowd intelligence is genuinely useful. A market that primarily reflects insider knowledge is worse than useless—it's misleading.

This is why the platforms' refusal to address insider trading matters so much. They're not just enabling fraud. They're undermining the legitimate case for why prediction markets should be useful tools.

FAQ

What exactly is a prediction market and how does it work?

A prediction market is a platform where people can buy and sell contracts based on future outcomes. For example, you might buy a contract that pays

Why is the Maduro bet considered suspicious?

The Maduro bet was suspicious for several reasons: (1) the account was brand new, created less than a week before the trades; (2) the account invested over $30,000 the day before a classified military operation occurred; (3) the military operation succeeded exactly as the bettor apparently predicted; (4) the account made a 1,360% return in 48 hours, which requires perfect foreknowledge of the outcome. This pattern is consistent with someone trading on classified information about planned military operations, not with legitimate market research or analysis.

Is insider trading actually illegal on prediction markets?

That's genuinely unclear. Traditional insider trading law applies to trading on material nonpublic information about securities. But there's legal ambiguity about whether prediction market contracts qualify as securities and whether existing insider trading statutes apply to them. Some prediction market platforms are deliberately structured and located outside the US to avoid regulatory scrutiny. The legal framework for enforcement hasn't been clearly established, which is partly why insider trading happens openly on these platforms without consequences.

Why don't prediction market platforms prevent insider trading?

Platforms could implement know-your-customer verification, flag suspicious trades that match the timing of government announcements, and cooperate with law enforcement investigations. Most don't because they believe these measures would reduce trading volume and user participation. They've calculated that accepting insider trading is a worthwhile trade-off for maintaining a pseudonymous, minimally-regulated platform that attracts high-volume traders. The platform position is essentially: insider trading improves market efficiency, we can't prevent it anyway due to pseudonymity, so we don't try.

How common is insider trading on prediction markets?

There's no official data, but reports suggest it's fairly common. Similar suspicious trades have been flagged on Kalshi and Polymarket multiple times. The pattern is consistent enough that observers expect it to keep happening. Given the incentives involved—someone with access to classified government information can make six figures from a single trade with minimal risk of detection—there's little reason to believe the Maduro trade was an anomaly rather than an example of how these markets actually function.

What should happen to address this problem?

Options include: (1) implement clear legal frameworks making insider trading on prediction markets explicitly illegal; (2) require platforms to implement compliance systems and report suspicious activity; (3) have law enforcement actively prosecute cases where trading patterns suggest insider information; (4) restrict prediction markets from existing in their current form; or (5) require platforms to maintain identity information and cooperate with investigations. The combination of uncertainty about legal authority, resource limitations for enforcement, and platform resistance means none of these are happening quickly.

Could using prediction markets for government decisions be a bad idea?

If prediction markets are infiltrated with insider traders, they don't reliably aggregate crowd intelligence—they show what people with information advantages happen to know. Using such markets to inform policy decisions would actually introduce bias toward people with access to classified information rather than genuine collective intelligence. This is one reason policymakers should be skeptical of proposals to use prediction markets for important decisions when the markets aren't properly regulated.

How does cryptocurrency make insider trading on prediction markets easier to commit?

Cryptocurrency allows traders to fund accounts pseudonymously, move money through untraceable wallets, and withdraw profits back into crypto without creating a clear financial trail from "federal employee with classified information" to "person profiting from that information." Traditional financial platforms require know-your-customer verification that creates paper trails law enforcement can follow. Crypto-based systems don't, making insider trading much harder to prosecute.

Why hasn't anyone been prosecuted for insider trading on these platforms?

Multiple factors: legal uncertainty about whether insider trading statutes apply; jurisdictional complexity (many platforms operate outside the US); limited law enforcement resources focused on this issue; difficulty identifying traders due to pseudonymity; and platforms' resistance to cooperation with investigations. The combination of these factors means insider trading happens openly without consequences, which creates incentives for it to continue happening.

What does this mean for the future of prediction markets?

Prediction markets face a choice: either implement real compliance and enforcement measures (which will reduce trading volume), or remain permissive about insider trading (which will undermine their claimed value as information aggregation tools). The most likely outcome is they'll muddle through the middle—making cosmetic compliance changes while doing nothing to actually prevent insider trading, which means their value as reliable information sources will continue to degrade.

Key Takeaways

The Maduro bet exposes a systemic flaw in prediction markets that platforms show no interest in fixing. Someone apparently trading on classified information about a military operation made $408,000 in profits while the platforms that enabled this trade claimed they had no responsibility to investigate or prevent it.

This isn't a isolated incident or a lucky guess. The timing, the account age, the investment size, and the accuracy of the prediction create a circumstantial case suggesting insider trading. The lack of investigation or enforcement suggests prediction market platforms are indifferent to insider trading—or consider it a feature rather than a bug.

The implications are serious. If these markets are primarily useful for people with information advantages to profit at the expense of regular traders, they're not tools for aggregating collective intelligence. They're tools for monetizing classified information. That changes everything about whether prediction markets should exist in their current form and whether they should be used to inform policy decisions.

Regulation will eventually catch up. But until it does, expect more Maduro-like trades. Expect federal employees with access to classified information to continue profiting from that access. Expect prediction markets to continue claiming they can't prevent insider trading while doing nothing to try. Expect law enforcement to continue moving slowly while the markets keep operating as they do.

The Maduro trade was a warning about what prediction markets have become when left unregulated. Nobody acted on that warning. They won't need to until the next one.

Further Reading and Related Topics

For those interested in exploring these topics further, consider investigating: how traditional financial markets prevent insider trading through SEC oversight and enforcement; the regulatory frameworks different countries use to manage prediction markets; how cryptocurrency is changing financial crime enforcement; the case for and against using prediction markets to inform policy; and the broader tension between decentralization and regulation in financial systems.

These topics collectively explain why prediction markets have become such an interesting and problematic experiment in financial regulation and why the Maduro trade matters beyond just one lucky trader making a fortune.

Related Articles

- Volkswagen's ID. Polo EV Brings Back Physical Buttons: The Dashboard Revolution [2025]

- Hyundai CES 2026 Live Presentation: Holographic Windshield & Atlas Robot [2025]

- How Disinformation Spreads on Social Media During Major Events [2025]

- Apple's Budget MacBook: Rumors, Specs & Launch Date [2025]

- California's DROP Platform: Delete Your Data Footprint [2025]

- Watch PDC World Darts 2026 Final Free: Complete Live Stream Guide [2025]

![Polymarket's $408K Maduro Bet Exposes Prediction Market Insider Trading Problem [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/polymarket-s-408k-maduro-bet-exposes-prediction-market-insid/image-1-1767474362648.png)