How Disinformation Spreads on Social Media During Major Events: The Maduro Capture Case Study

You've probably seen it happen. A major breaking news story drops, and within minutes your feed is flooded with videos that don't quite look right, images that seem oddly rendered, or clips you swear you've seen before. The problem isn't new, but it's getting worse. And what happened on social media after Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro's capture in early 2025 shows exactly how broken these platforms have become at handling moments of genuine geopolitical significance.

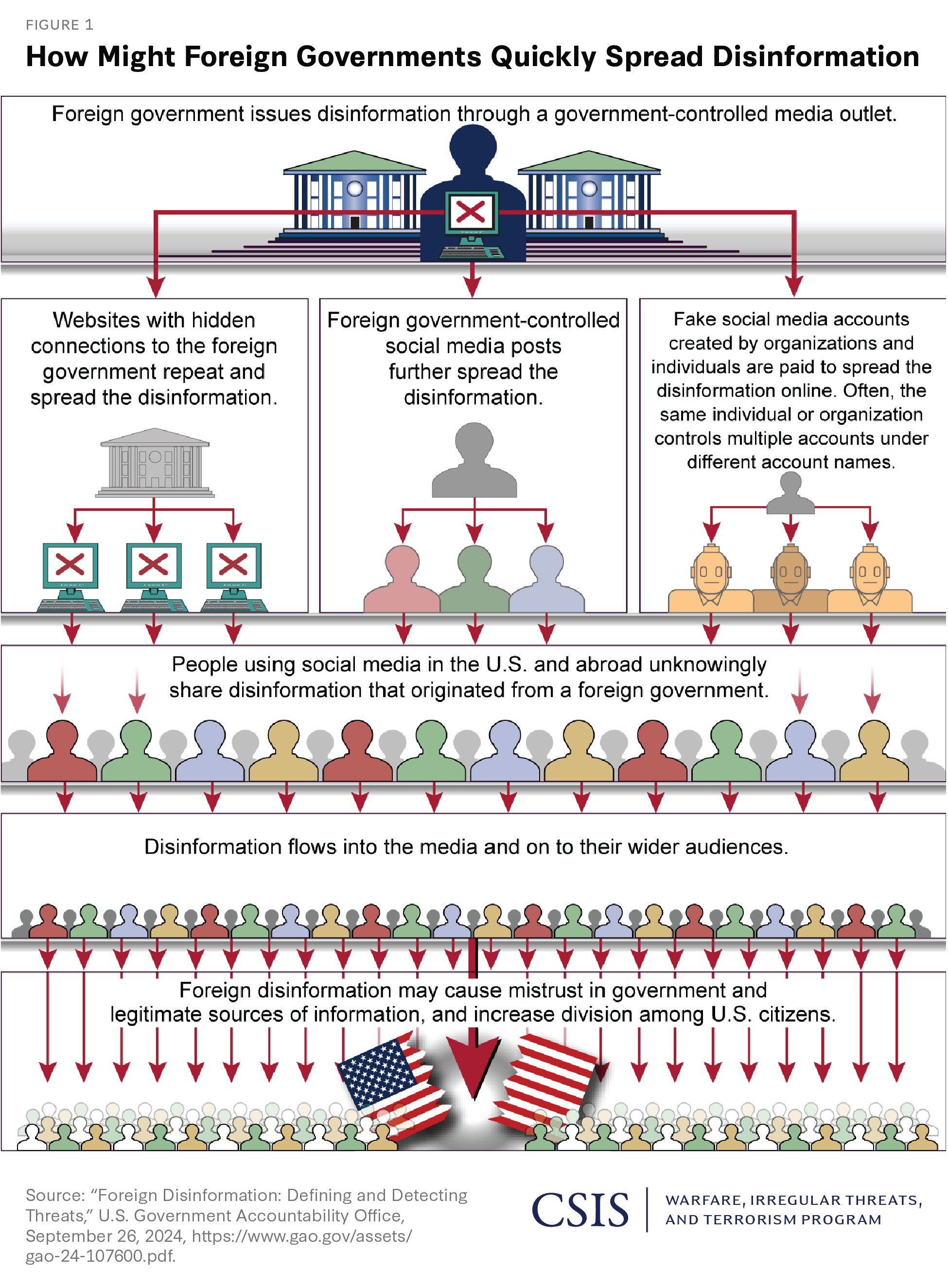

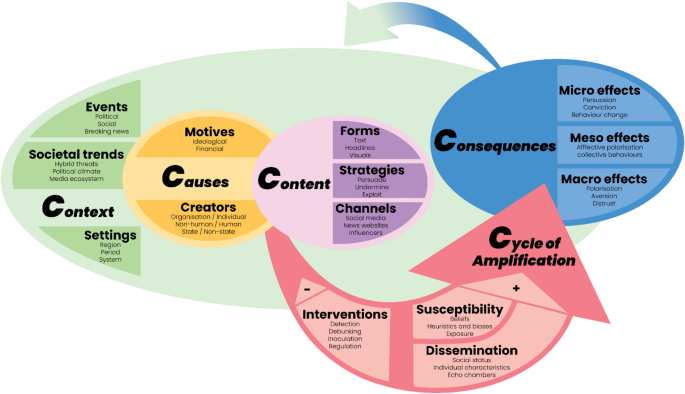

This isn't just about a few fake videos circulating for an hour before getting taken down. We're talking about a coordinated wave of misinformation that spread across multiple platforms simultaneously, racked up millions of views, and remained online for extended periods with minimal intervention from platform moderators. The incident reveals something critical about how social media companies have systematically deprioritized content moderation, how AI has made creating convincing fake media trivially easy, and how algorithmic amplification ensures misleading content reaches more people than accurate reporting.

What makes this case particularly telling is that it wasn't subtle. The fake images were identifiable as AI-generated using publicly available tools. The recycled footage was timestamped years earlier. The videos didn't require specialized knowledge to debunk. Yet they spread anyway, reaching hundreds of thousands of people who may never have seen corrections, or encountered corrections far later than the original false claims.

This is the state of information ecosystems in 2025. This article breaks down exactly what happened, why platforms failed to prevent it, and what these failures mean for how we'll navigate major breaking news in the future.

TL; DR

- Platforms were unprepared: Within minutes of Maduro's capture announcement, AI-generated images and old footage flooded Tik Tok, Instagram, and X without immediate removal.

- AI-generated content went viral: Multiple AI-synthesized videos showing fake arrests reached hundreds of thousands of views, with some based on a single Instagram post from a digital creator.

- Recycled footage spread as live coverage: Years-old videos were reposted as current footage from Caracas, with accounts gaining millions of views before removal.

- Platform responses were absent: Meta, Tik Tok, and X didn't issue statements, fact-check labels, or implement proactive removal strategies.

- Moderation is effectively gone: With companies slashing fact-checking teams and deprioritizing content review, misinformation now spreads faster than corrections.

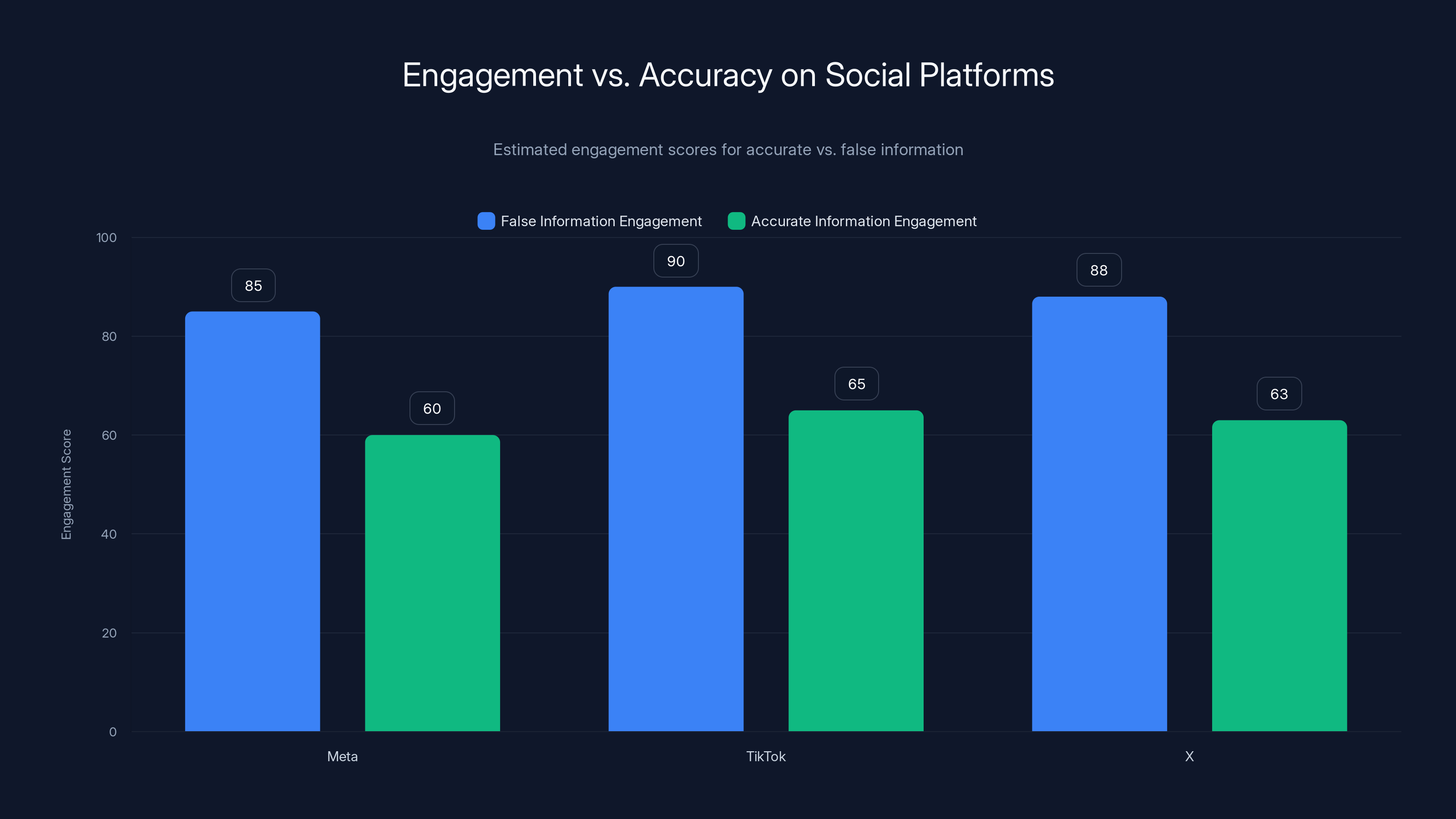

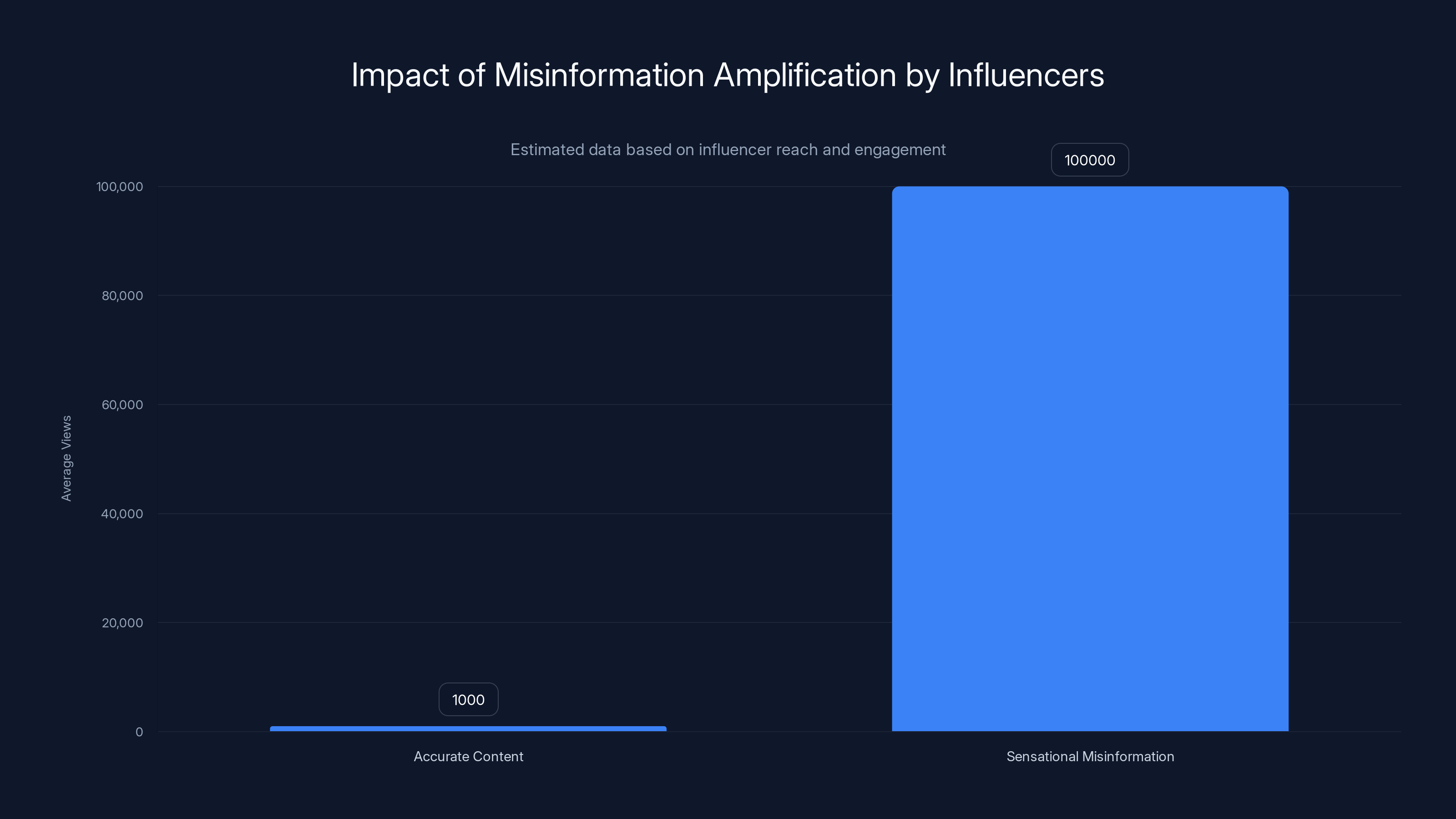

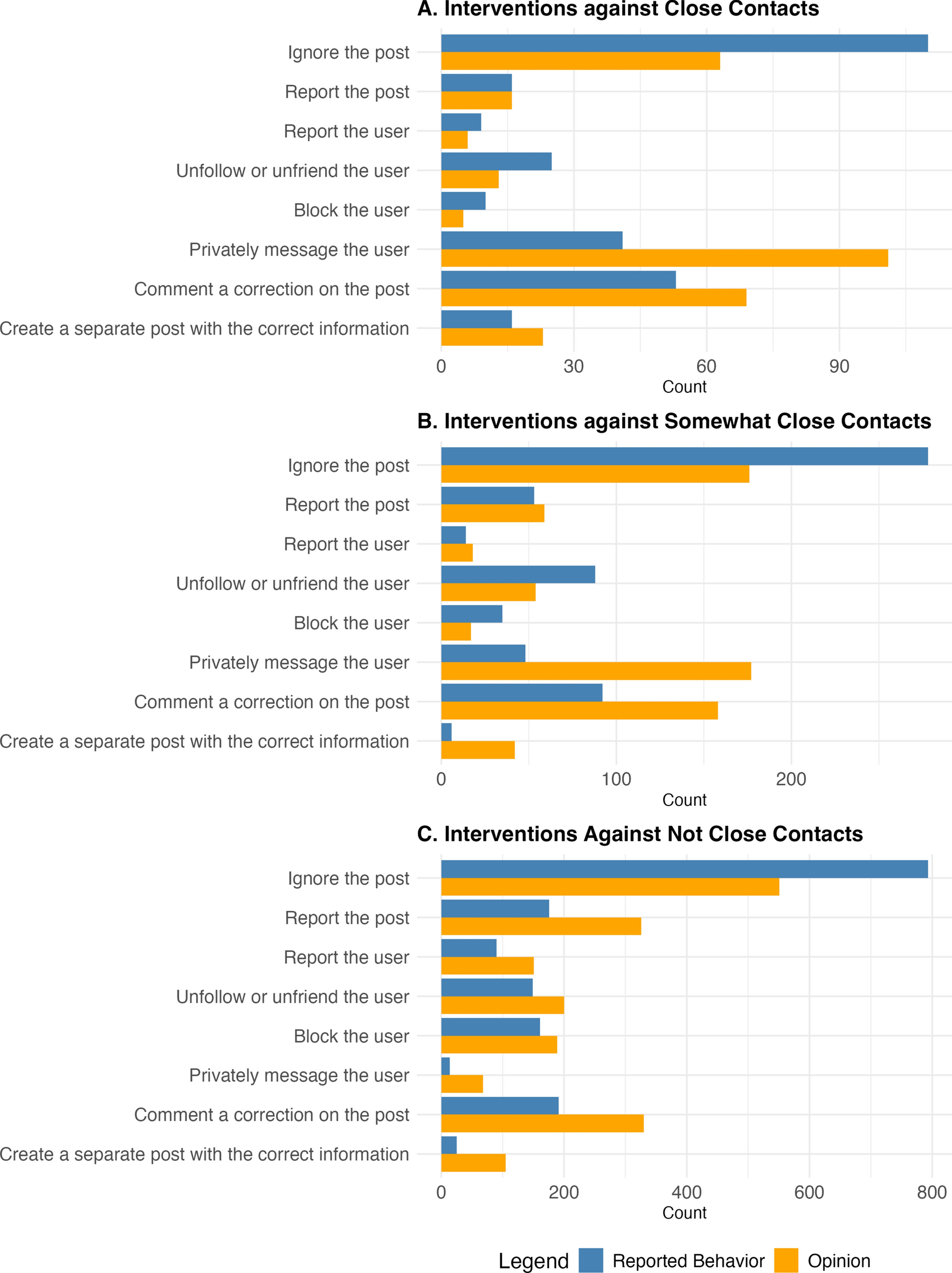

Estimated data shows false information consistently drives higher engagement across platforms compared to accurate information, highlighting the business model conflict between engagement and accuracy.

The Timeline: How Misinformation Spread in Real Time

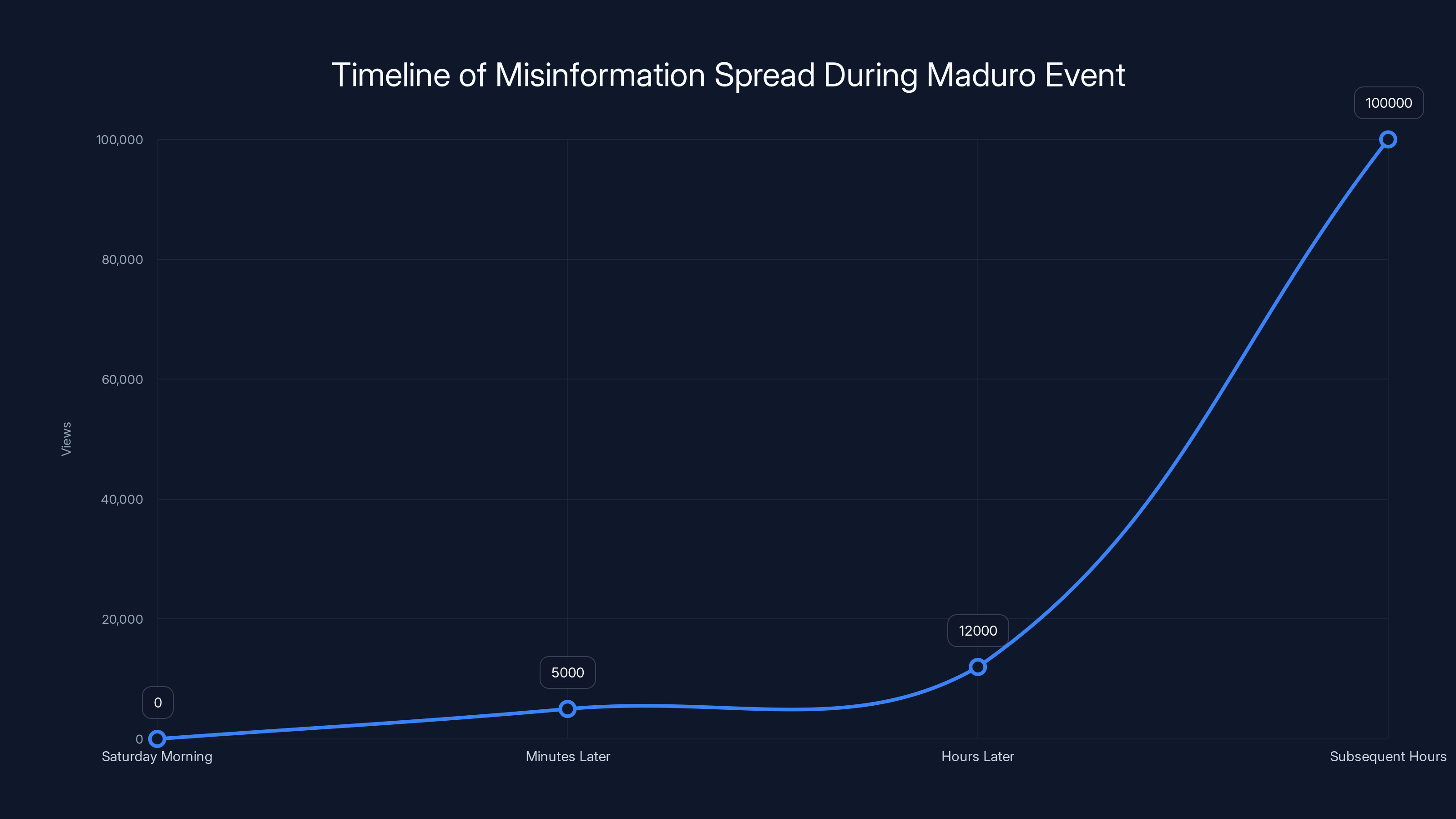

Understanding the Maduro disinformation event requires understanding the sequence. Timing matters because it shows that viral spread happened before any meaningful platform intervention could theoretically occur.

On Saturday morning in the early hours, Donald Trump announced on Truth Social that US troops had captured Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. The announcement read: "The United States of America has successfully carried out a large scale strike against Venezuela and its leader, President Nicolas Maduro, who has been, along with his wife, captured and flown out of the Country."

Within minutes—not hours, but minutes—fake content began circulating. A AI-generated image showing two DEA agents flanking Maduro appeared across social platforms simultaneously. The image looked plausible to the untrained eye. The lighting seemed reasonable. The composition matched other law enforcement photos. But it was entirely synthetic.

Hours later, US Attorney General Pam Bondi announced on X that Maduro and Flores had been indicted in the Southern District of New York on charges of narco-terrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation, and weapons possession. This legitimate news provided more fuel for misinformation spreaders who now had additional context to build false narratives around.

By this point, the fake content had already gained substantial traction. On Tik Tok specifically, multiple AI-generated videos purporting to show Maduro's arrest had accumulated hundreds of thousands of views. These videos appeared to originate from a single source: an Instagram digital creator named Ruben Dario who had posted AI-generated images that received over 12,000 views. Other creators had then taken these images and weaponized them using video generation tools, creating the false arrest videos.

Simultaneously, a different category of misinformation was spreading. Old footage from 2024 showing people taking down a Maduro poster was being reposted as current footage from Saturday's capture. High-profile influencers like Laura Loomer amplified this recycled content on X, claiming it showed Venezuelans celebrating in the streets during the US operation. The original video had been filmed nearly a year prior, but most people sharing it had no way to verify the actual date.

Another post by an account calling itself "Defense Intelligence" showed combat footage and claimed it depicted the US assault on Caracas. The video had been originally posted on Tik Tok in November 2025. By the time WIRED was reporting on the disinformation, this misleading post had been viewed over 2 million times on X. It remained online despite the false claim.

The entire cycle from announcement to widespread viral misinformation took less than two hours. Platform responses, by contrast, were either nonexistent or came days later as addendums to fact-checking articles.

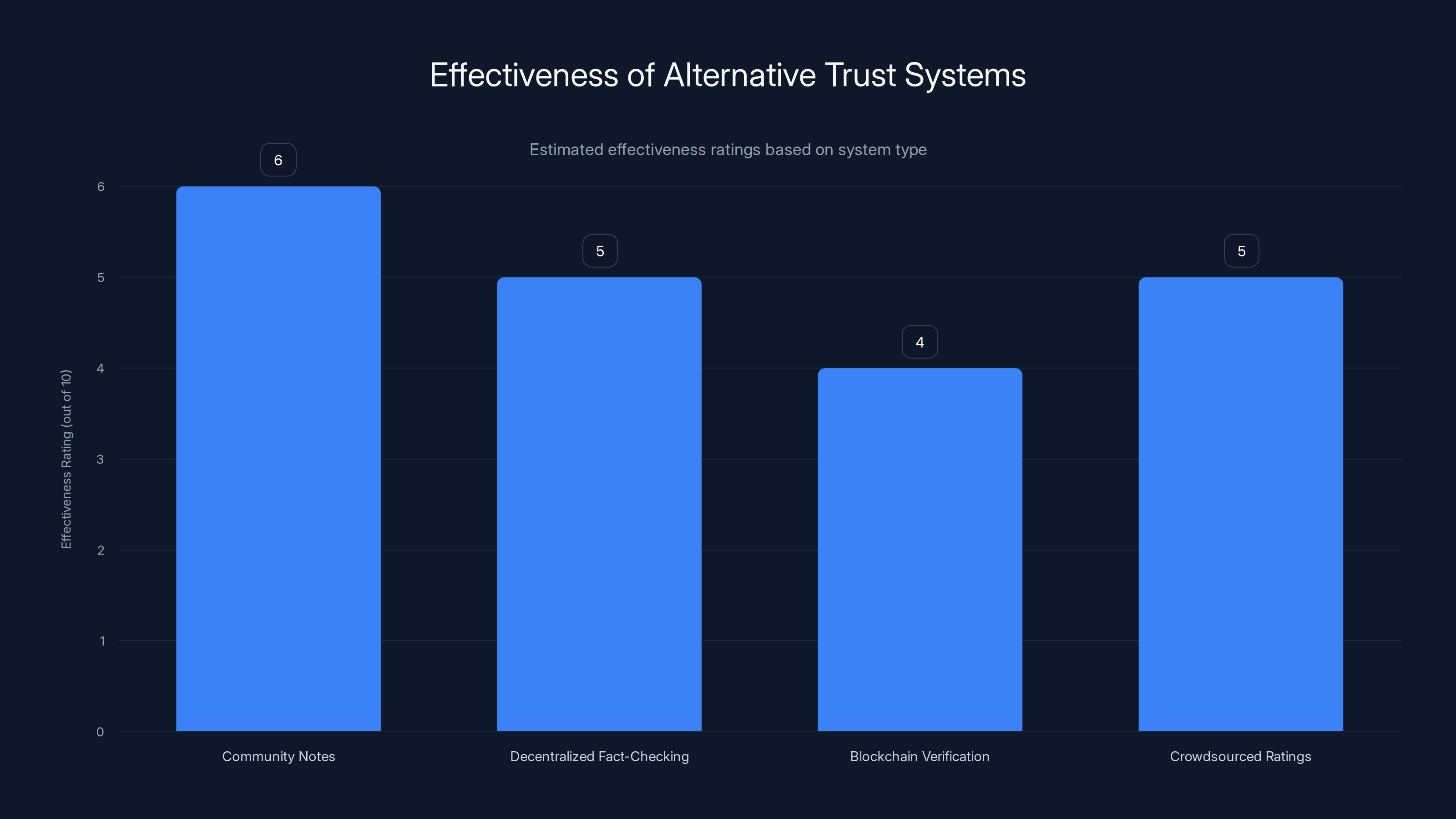

Community Notes are moderately effective for verifiable claims but struggle with rapid news. Decentralized systems face challenges with gaming and complexity. Estimated data.

How AI-Generated Images Became Impossible to Spot

The most striking element of the Maduro misinformation event was how convincing the AI-generated images were to casual observers. This raises a fundamental question: when synthetic media becomes indistinguishable from authentic media, what does that mean for public discourse?

The fake image showing two DEA agents with Maduro was produced using modern generative AI tools. Most people who saw it wouldn't have questioned its authenticity. The composition was professional. The lighting was consistent. The details were rendered with enough fidelity that it passed initial visual inspection.

To confirm the image was fake, WIRED used Synth ID, a detection technology developed by Google Deep Mind. Synth ID works by identifying invisible digital signals—watermarks embedded by Google's AI tools during the generation or editing process. When WIRED's researchers ran the Maduro image through this analysis, Google's Gemini chatbot provided a detailed technical breakdown: "Based on my analysis, most or all of this image was generated or edited using Google AI. I detected a Synth ID watermark, which is an invisible digital signal embedded by Google's AI tools during the creation or editing process. This technology is designed to remain detectable even when images are modified, such as through cropping or compression."

This detection method works, but it has a critical limitation. Synth ID detection requires active analysis using specialized tools. It doesn't work automatically on platforms. A Tik Tok or Instagram user won't know an image is AI-generated unless they deliberately run it through Google's detection tool or rely on fact-checkers who have done so. For the millions of people who saw the fake Maduro image in their feeds, there was no automatic indicator of its synthetic nature.

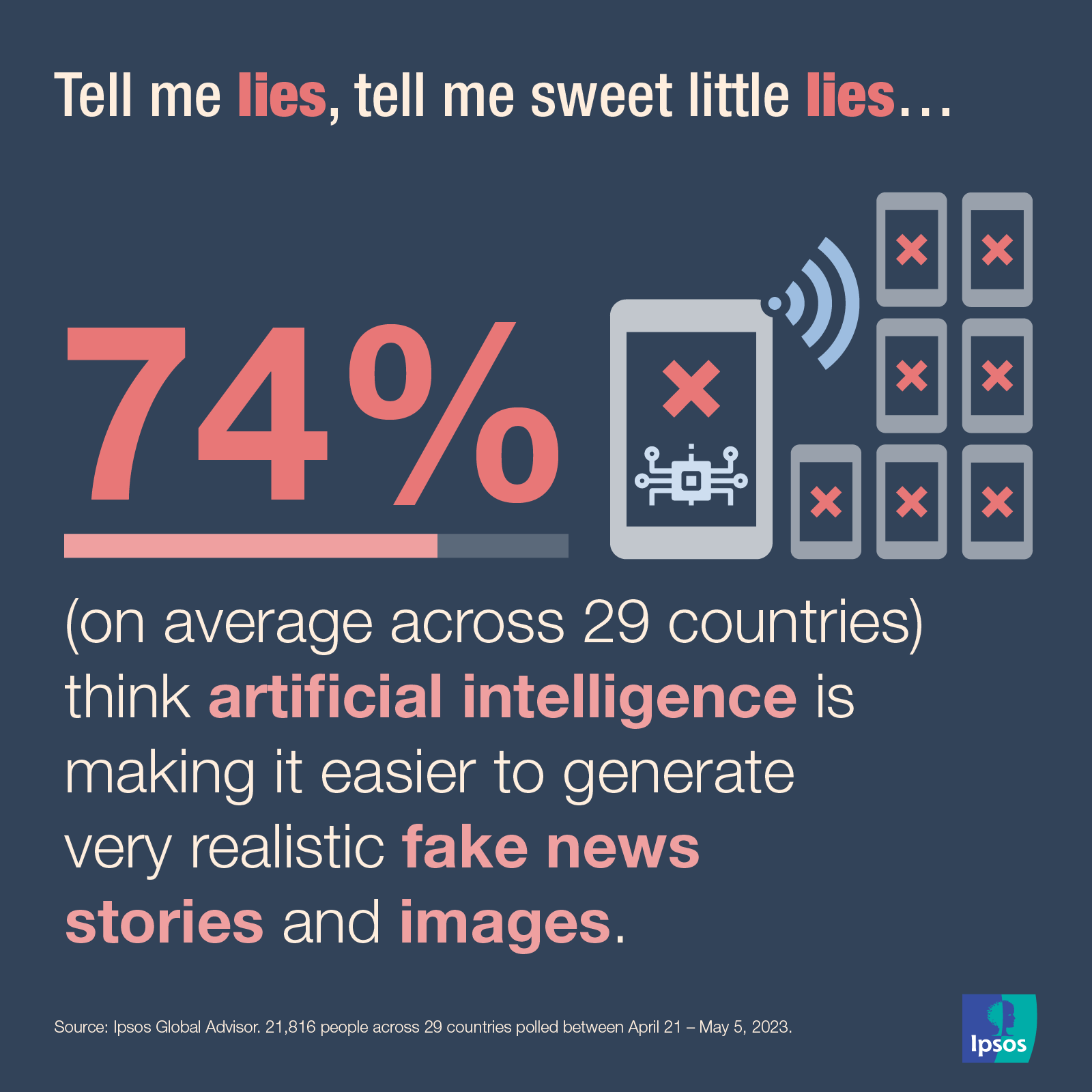

The broader pattern here is troubling. In 2020, AI image generation was still visibly imperfect. You could spot artifacts, warped hands, inconsistent details. By 2024-2025, that's largely changed. Tools like Midjourney, DALL-E 3, and Stable Diffusion produce images that are genuinely difficult to distinguish from photographs without expert analysis or watermark detection.

Some platforms attempted to address this problem. X's Grok AI chatbot, when asked to analyze the Maduro image, did correctly identify it as fake. However, Grok made an error in its reasoning—it falsely claimed the image was an altered version of Mexican drug boss Dámaso López Núñez's arrest from 2017. This is an important distinction because it shows that even when detection occurs, the explanation can be misleading.

Meanwhile, Chat GPT, when asked about the Maduro capture on Saturday morning, strongly denied it had happened at all. The AI model had outdated training data and didn't recognize the event as real. This created an ironic situation where one AI system (Chat GPT) was skeptical of real news, while another AI system (Grok) was attempting to fact-check AI-generated misinformation.

The fundamental issue is this: the tools exist to detect synthetic media, but they're not integrated into social platforms where the vast majority of people encounter information. You need to actively choose to use them. Most people don't.

The Viral Video Problem: One Fake Image, Infinite Variations

The real multiplication of misinformation didn't happen at the image level. It happened when creators took those AI-generated images and fed them into video generation tools, creating video content from still images.

On Tik Tok, multiple videos appeared showing Maduro's arrest in motion. These videos weren't new recordings. They were AI-generated animations based on the fake still images. A single source image could be transformed into dozens of variations using different video tools, filters, and editing techniques. Each variation felt slightly different, which helped them bypass platform algorithms looking for duplicate content.

These videos accumulated views at an extraordinary pace. Within hours, videos based on the original Ruben Dario Instagram post had reached hundreds of thousands of Tik Tok users. Some individual videos exceeded 500,000 views. The engagement was genuine—people were commenting, sharing, and creating their own versions.

What's particularly insidious about video misinformation is that it's harder to debunk than still images. A video has narrative weight. It has motion and audio, which create a sense of authenticity. Even when viewers suspect something might be fake, the production value makes them hesitate. "Maybe I'm wrong," they think. "This looks pretty real."

Video generation technology has improved dramatically. In 2023, obvious artifacts still appeared—warped faces, inconsistent lighting, temporal glitches. By 2025, these issues are largely resolved. Tools like Runway, Synthesia, and D-ID can create convincing video content from still images. Some require text prompts and voice input. Others can work directly from images.

The problem is that none of these tools are built with watermarking or traceability at the forefront. Yes, some AI video tools include Synth ID watermarks, but this is inconsistent. A creator could generate a video in one tool, export it, import it to another tool for editing, and the watermark might be lost or degraded in the process.

Tik Tok's algorithm amplified this content aggressively. The platform's recommendation system is optimized for engagement, not accuracy. Controversial, surprising, or shocking content performs well algorithmically. A fake video of a US arrest of a foreign leader is exactly the type of high-engagement content that Tik Tok's algorithm will push to more users.

The platform made no effort to slow this spread. There were no friction mechanisms, no warning labels, no removal. Tik Tok, Meta, and X all declined to comment on their moderation response when WIRED reached out.

Estimated data shows a decline in moderation efforts by major platforms from 2020 to 2025, reflecting a shift towards less costly and controversial strategies.

Recycled Footage as Breaking News: The Old Becomes New

While AI-generated content spread rapidly, equally problematic was the recycling of old footage as current events. This is one of the oldest forms of social media misinformation, yet it remains effective because it requires less technical sophistication than creating synthetic media.

The video showing people taking down a Maduro poster was originally filmed in 2024. This isn't a marginal difference. It's nearly a year old. Yet when it circulated on Saturday morning, it was presented as footage from the events unfolding in Caracas during Maduro's capture.

Laura Loomer, a prominent influencer with substantial reach, shared this video on X with the caption: "Following the capture of Maduro by US Special Forces earlier this morning, the people of Venezuela are ripping down posters of Maduro and taking to the streets to celebrate his arrest by the Trump administration."

The framing was explicit. The video was presented as current footage showing Venezuelan citizens celebrating. There was no caveat, no "earlier footage showing celebrations," no uncertainty. The implication was that this was happening right now, as part of the response to Maduro's capture.

Loomer eventually removed the post, but not before it had been seen, liked, retweeted, and shared thousands of times. The removal didn't undo the spread of the narrative. People who saw the initial post retained the false impression even after the post was gone.

This pattern repeated across multiple accounts. The "Defense Intelligence" account's post of November 2025 Tik Tok footage, presented as Saturday's assault on Caracas, exemplified the same problem. Old footage, new context, instant credibility problem.

The reason recycled footage spreads so effectively is that it contains authentic elements. The video is real. It was filmed by real people and genuinely shows what it depicts. The only false element is the temporal and contextual framing. But that false framing is everything. The same video of a protest in 2024 tells a completely different story when labeled as happening in 2025 in response to a specific geopolitical event.

Identifying recycled footage requires temporal context that most people don't have access to. You'd need to know when the original was posted, who posted it, and where it was filmed. Reverse image searching can help, but it requires active effort. Most social media users don't perform reverse searches. They see a video that looks plausible and moving, and they share it.

Platforms could implement technical solutions to flag recycled content. You Tube, for instance, has systems that identify when video content has been uploaded multiple times and can tag rereleases as such. Tik Tok and X don't use equivalent systems. They could, but they don't prioritize it.

The choice not to implement these solutions relates to a broader platform strategy: keeping friction low and engagement high. Slowing down the spread of content—even misleading content—requires resources and risks reducing overall platform usage if users feel content is being suppressed.

Platform Responses: Absence as Strategy

One of the most striking aspects of the Maduro misinformation event was what didn't happen. There were no immediate statements from Meta, Tik Tok, or X about their moderation approach. No fact-check labels were proactively applied to viral misinformation. No emergency response protocols were activated.

When WIRED reached out to all three platforms requesting comment on their moderation efforts, they received no responses. This silence is informative. It suggests either that no coordinated moderation effort occurred, or that the platforms didn't consider the situation significant enough to warrant a public communication.

This represents a dramatic shift from even five years ago. In 2020, during the US election and the COVID-19 pandemic, major platforms were aggressively fact-checking, removing content, and publishing regular transparency reports about their moderation actions. Platform executives appeared on news programs to defend their efforts. There was, at least, a performative commitment to fighting misinformation.

By 2025, this has largely evaporated. Meta has scaled back its fact-checking operations significantly. The company announced major shifts in its content moderation approach, moving away from third-party fact-checkers toward community-based notes systems. Tik Tok has deprioritized content moderation as a cost-cutting measure. X, under new leadership, dissolved its entire fact-checking program and eliminated many content moderation roles.

These aren't subtle shifts. They represent fundamental repositioning of how these companies approach their responsibility for information quality on their platforms. The rationale, from the platforms' perspective, is roughly: fact-checking is expensive, controversial, and may reduce engagement. Community-based correction systems are cheaper and potentially less controversial, though less reliable.

The result is exactly what we saw with Maduro misinformation. Viral spread with minimal friction. Users can encounter false information, but if they're motivated to fact-check, they'll find community notes or fact-check articles eventually. The platforms themselves aren't actively intervening.

For major breaking news events, this approach creates information chaos. During the first few hours after Maduro's capture, the average user on Tik Tok or X would have encountered more AI-generated fake content than legitimate reporting. The algorithmic feed naturally prioritizes emotional, high-engagement content. Misinformation is often more emotional and surprising than factual reporting.

One specific failure was platform handling of AI-generated content. X's Grok model could identify the fake image, but this correction wasn't visible to most users. They would have needed to encounter the specific correction or seek it out. For the millions who saw only the initial post, no correction was forced into their feed.

The absence of platform response also meant that the original sources of misinformation faced minimal consequences. Ruben Dario's Instagram post, which spawned multiple viral Tik Tok videos, wasn't removed or labeled. The "Defense Intelligence" X account that spread the miscontextualized combat footage continued operating normally. Laura Loomer eventually removed her post, but this was apparently voluntary—no platform enforcement occurred.

Algorithmic amplification and AI tools accessibility are leading factors in misinformation spread during breaking news events. (Estimated data)

The Role of Influencers and Amplification Networks

Misinformation doesn't spread randomly. It spreads through specific networks and is amplified by specific accounts. The Maduro event reveals how influencers and high-follower-count accounts play a critical role in taking niche false information and making it mainstream.

Laura Loomer isn't an average Tik Tok creator. She's a prominent political influencer with hundreds of thousands of followers. When she shares content, it reaches a massive audience instantly. Her post about the poster-removal video wasn't just her personal observation—it was an act of amplification that took a piece of content and exposed it to orders of magnitude more people.

This pattern is systematic. Throughout the Maduro event, various high-profile accounts shared and amplified false content. Some were explicitly political. Others were just accounts that build audiences by sharing "shocking" or "surprising" content without concern for accuracy.

The incentive structure is clear. Misinformation performs well algorithmically. It generates engagement. It drives follower growth. A creator who shares accurate, measured reporting might accumulate 1,000 views. The same creator sharing sensational false information might accumulate 100,000 views. This economic incentive drives creators toward misinformation.

Influencers also create what researchers call "cascading misinformation." One influencer shares false content. Other creators, seeing the engagement on the first post, create similar content. Different creators then remix, reword, and recreate variations. By the time content has cycled through multiple creators, the original source is completely obscured.

During the Maduro event, this happened with extreme speed. The original AI-generated image spawned multiple video variations within hours. Each variation had different creators, different captions, different contexts. Yet they all traced back to the same false source.

X specifically enabled this cascading effect through its quote-retweet feature. A single post about the fake Maduro arrest could be quote-retweeted hundreds of times. Each quote-retweet could add new commentary, new framing, new claims. The original post remained visible, but so did all the derivative posts, creating a dense network of related misinformation.

Influencer networks also create redundancy that protects false information from removal. If one account sharing the false content gets suspended, others are still sharing it. Removing misinformation becomes a game of whack-a-mole where the mole can reproduce faster than you can whack.

AI as Both Problem and Attempted Solution

The Maduro misinformation event demonstrates a crucial paradox of 2025: AI is simultaneously the primary source of new misinformation and the primary tool platforms are relying on to detect and combat it.

The fake images were created with generative AI. The videos were created with AI video synthesis tools. The text commentary amplifying these materials was sometimes generated with language models. Yet detection of this misinformation relied on AI analysis (Synth ID, Grok analysis, computer vision algorithms).

This creates an arms race dynamic. As detection improves, generation tools improve to evade detection. Watermarks can be degraded through compression and re-encoding. Detection algorithms can be studied and circumvented. This isn't theoretical—researchers have already published papers on watermark removal techniques and adversarial attacks on detection systems.

Platforms are betting that AI detection will win this race. But this bet assumes significant resources invested in running detection systems at scale. It assumes continuous updating as generation techniques evolve. It assumes that false negatives (undetected synthetic content) are acceptable up to some threshold.

They're not betting on human moderation at scale. That would be expensive and slow. Human moderators reviewing every post, image, and video across billions of pieces of content would require more people than platforms are willing to employ.

Google's Synth ID watermarking technology was actually one of the success stories of the Maduro event. It worked to detect the synthetic image. But here's the limitation: Synth ID only works on images processed through Google's AI tools. If someone generates an image using Midjourney or another non-Google tool, Synth ID detection won't work. Other detection tools exist, but they're less reliable and not integrated into major social platforms.

The asymmetry is profound. Creating misinformation with AI is easy and requires no special resources. Detecting and removing it requires specialized tools, constant updating, and significant computational resources. For platforms operating on thin profit margins and focused on engagement, the detection side of this equation is underinvested.

There's also the question of what happens to detected synthetic content. Does it get removed entirely? Does it get labeled as AI-generated? Does it stay up but get deprioritized in recommendations? Different platforms have different policies, and policies change frequently. This inconsistency means that creators can simply post the same false content to multiple platforms and expect different moderation outcomes on each.

The attempted solution of community notes (X's approach) and community correction (Meta's recent pivot) relies on users to identify false content and leave accurate information in the form of notes. This works when communities are well-informed and engaged. During breaking news, when information is uncertain and evolving, it's much less effective. The fastest, most confident people will write notes, regardless of whether they're actually correct.

The misinformation spread rapidly, reaching over 100,000 views within hours of the initial post. Estimated data based on narrative sequence.

Breaking News Environments and Information Uncertainty

Breaking news creates specific conditions that misinformation thrives in: information uncertainty, information hunger, and rapid distribution.

When Trump announced Maduro's capture, the immediate questions were obvious. Was it real? What actually happened? What would happen next? Details were scarce. Official statements were minimal. The situation was evolving.

In this environment, people fill information gaps with speculation. If no reliable sources are available, they'll believe speculation from sources they encounter. If multiple sources are available but contradictory, they'll believe sources that align with their existing beliefs.

Misinformation about Maduro benefited from this dynamic. People hungry for details about the capture encounter a fake image showing DEA agents. The image is recent (they assume, because it's circulating now). It shows something relevant (what they were already thinking about). It feels like real information.

The first information someone encounters on a topic disproportionately shapes their understanding. This is the "illusory truth effect." Even when later corrections are issued, they don't fully displace the initial impression. The false image of Maduro's arrest, once seen, becomes part of viewers' mental model of what happened, even if they later learn it was fake.

During breaking news, social media algorithms amplify exactly this dynamic. They boost novel, surprising, high-engagement content. Misinformation is novel and surprising (if the false image looks plausible, it's new information to the viewer). It generates engagement (shares, likes, comments, replies). The algorithm doesn't care whether the content is accurate.

Traditional media outlets have structures to slow this down. Reporters verify before publishing. Editors review before publication. Legal teams check for liability. These processes take time—sometimes hours. By the time a traditional news outlet publishes carefully verified reporting about Maduro's capture, millions have already encountered false information on social media.

This is a fundamental structural problem with how information flows in 2025. Social media is optimized for speed and engagement. Accurate reporting is optimized for verification and reliability. Speed wins the distribution race almost every time.

One potential mitigation is slowing down social media during breaking news. Reduce algorithmic amplification, require waiting periods before sharing, implement friction that makes people think twice. But platforms resist friction because it reduces engagement. They might lose users to competitors who don't have friction.

Some platforms experimented with friction during the COVID-19 pandemic and early elections. They saw reduced sharing of misinformation, but also reduced overall engagement. They scaled back these experiments and returned to frictionless sharing.

The Business Model Problem: Engagement Over Accuracy

Understanding why platforms don't effectively combat misinformation requires understanding their business model. It's not that platforms lack the technical capability. They lack the business incentive.

Meta, Tik Tok, and X derive revenue from advertising. Advertisers pay based on user engagement. User time spent on platform and interactions (likes, shares, comments) drive revenue. Content that maximizes engagement gets amplified. Content that's accurate but less emotionally stimulating gets buried.

This creates a direct conflict between business incentives and information quality. Spending resources to combat misinformation reduces engagement (people see fewer shocking, false posts). Fewer interactions mean lower ad revenue. It's a direct line from accurate information moderation to lower profits.

This isn't speculation. Research has shown that false information consistently outperforms accurate information in terms of engagement metrics. False information is more surprising, more emotional, more likely to generate strong reactions. In a system optimized for engagement, false information is literally more profitable.

Platforms could internalize the social cost of misinformation. They could say, "We'll accept lower engagement in exchange for better information quality." But that would mean accepting lower revenues. It would mean competitors who don't implement the same restrictions would gain market share. It would mean explaining to shareholders why revenues declined.

No major platform has chosen this path. Some invested in moderation for reputational reasons (responding to pressure from governments, media, civil society groups). But as the pressure decreased and as misinformation spread became routine, the investment waned.

Meta illustrates this pattern clearly. In 2016-2020, the company faced intense pressure over election misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine misinformation. It invested heavily in fact-checking, hired hundreds of moderators, deployed detection systems. By 2023-2024, as the public focus shifted to other issues, the investment decreased. The company announced plans to reduce fact-checking and shift to community notes. The change wasn't because fact-checking was ineffective. It was because the reputational pressure that motivated the investment had declined.

X's evolution is even more explicit. After Elon Musk's acquisition, the company eliminated its fact-checking program, laid off the vast majority of its moderation staff, and deprioritized misinformation concerns. The rationale offered was that this would "restore freedom of speech." The economic reality was that this saved significant operating costs and potentially increased engagement (people share more when moderation is light).

Tik Tok faces pressure from different sources (potential regulation, government scrutiny), but faces similar business model incentives. Better content moderation means lower engagement, lower user time on platform, lower revenue.

The business model problem is fundamental because it affects all platforms equally. Restructuring how platforms derive revenue would be necessary to change the incentive structure. Platforms could be nonprofit, funded by subscription, funded by government, or funded by some other mechanism. None of these alternatives have gained traction with platforms or users.

Estimated data shows sensational misinformation can receive 100 times more views than accurate content, highlighting the economic incentive for influencers to spread false information.

Regulatory Responses and Their Limitations

Governments around the world have attempted to regulate social media misinformation. These efforts face fundamental challenges that became apparent during the Maduro event.

The European Union's Digital Services Act mandates that platforms conduct due diligence on illegal content and misinformation. But the law doesn't specify what due diligence means or what outcomes platforms must achieve. Some interpret it as requiring rapid removal of flagged content. Others interpret it as requiring transparency about how platforms identify and handle misinformation. No precise legal standard exists.

The United States has no comprehensive federal regulation of misinformation. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shields platforms from liability for user-generated content, creating limited legal incentive to moderate. Bipartisan efforts to reform Section 230 have stalled in Congress for years. Proposals to specifically regulate AI-generated content remain in early stages.

Other countries have implemented stricter approaches. Singapore's Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act mandates rapid removal of "false statements of fact" deemed to be in the public interest to correct. But defining what constitutes a "false statement of fact" during breaking news—when facts are still emerging and uncertain—is practically impossible. The law risks being used to suppress legitimate news.

During major geopolitical events, regulatory questions become especially fraught. Who determines what's false? The government? Independent fact-checkers? The crowd? All of these have limitations. Governments have incentives to suppress information that's inconvenient but true. Fact-checkers have limited resources and can't verify everything in real time. Crowdsourced correction is unreliable during uncertainty.

The Maduro event raised these issues without resolving them. US regulation would presumably favor US government determinations of what happened. But other governments would have different views. Venezuelan government sources might have denied the capture entirely. This creates conflict between different regulatory frameworks and different facts on the ground.

Regulation also faces a fundamental technological problem: speed. Regulatory action takes time. Investigation takes time. Appeals take time. Meanwhile, misinformation spreads in hours. By the time a regulatory body has determined that content is false and must be removed, it's already been seen by millions and reshared countless times.

Some regulatory proposals suggest proactive measures like watermarking all AI-generated content. The concept is appealing—every synthetic image would be automatically marked as such. But implementation faces challenges. Watermarks can be removed (though detection tools can find signs of removal). International coordination would be necessary because generators could simply operate from countries without watermarking requirements. Legitimate AI use cases (creating art, illustrations, visual effects) would also face burdens.

Alternative Trust Systems and Their Shortcomings

As traditional content moderation has proven expensive and controversial, some platforms and researchers have explored alternative systems. These include community notes, decentralized fact-checking, blockchain-based verification, and crowdsourced rating systems.

X's Community Notes system is the most implemented alternative. Under this model, X users add context or corrections to posts that they believe are misleading. If enough users agree with a note, it becomes visible to others. The idea is that rather than platform employees deciding what's accurate, the community does.

Community Notes worked moderately well for certain types of misinformation (easily verifiable false claims, like incorrect statistics). During breaking news, its limitations became apparent. The Maduro event happened fast. By the time community notes could be added to false posts, those posts had already circulated widely. And because people had different interpretations of what happened (is the capture verified? what are the details?), achieving consensus on notes was more difficult.

Decentralized fact-checking systems propose that anyone can become a fact-checker, and their reputation score determines how much weight their corrections receive. This theoretically harnesses distributed knowledge and reduces reliance on institutions. In practice, reputation systems can be gamed, and fact-checking requires specialized knowledge (like understanding geopolitical context) that not all users possess.

Blockchain-based verification systems propose creating permanent, timestamped records of claims and corrections. This would help identify recycled content and track how information evolved. Some experimental systems exist, but none have achieved widespread adoption. They're also complex enough that average users won't interact with them.

All of these alternatives share a problem: they require user engagement. They work only if users actively participate in correction, verification, and fact-checking. During breaking news, users are typically consuming information, not contributing to verification systems. The people who do contribute are self-selected and might have their own biases.

They also don't address the fundamental algorithm problem. Even if community notes exist, the algorithm might not show them. The false post might be amplified to millions while the correction is never seen by most viewers.

The Future of Breaking News in a Misinformation Age

Assuming the current trajectory continues, breaking news events in the coming years will likely follow similar patterns to the Maduro event: rapid spread of misinformation, platform responses that are slow or absent, and a fractured information environment where different people encounter dramatically different versions of what happened.

Several developments could change this trajectory. Advances in AI detection could make synthetic media identification more reliable and faster. But as discussed, this technology races against improvements in generation technology. It's unclear which will win.

Regulatory pressure could force platforms to invest more heavily in moderation. But regulation typically lags behind technological change, and different countries will regulate differently. A global information environment with different rules in different regions creates its own complications.

User behavior could shift. If enough people become skeptical of breaking news on social media, they might rely more on traditional news sources. But this requires sophisticated media literacy that large portions of the population don't have.

Business model changes could realign incentives. If platforms adopted subscription models without advertising, engagement wouldn't directly determine revenue. But switching from ad-supported to subscription would likely reduce user bases substantially.

Likely, the future will involve a combination of technical improvements (better detection, watermarking), regulatory pressure (especially from the EU), and user fragmentation (different segments relying on different information sources). This fragmentation itself becomes problematic because it prevents shared agreement on basic facts.

The specific case of US-Venezuela relations and the Maduro situation demonstrates the geopolitical aspect of misinformation. US-based platforms make judgment calls that affect how Americans understand foreign policy. Different countries might have different interests in how this event is framed. Misinformation spreads differently in Spanish than English, reaches different audiences, reflects different narratives.

How to Navigate Misinformation During Breaking News

Until systems improve, individual media consumers need strategies for avoiding misinformation during breaking news events.

First, implement a waiting period. The first reports of any major event are almost certainly incomplete and partially inaccurate. Waiting 30-60 minutes for established news organizations to report and verify significantly reduces the chance you'll spread false information. In 30 minutes, fact-checkers can begin analyzing, journalists can reach sources, and confusion can be partially resolved.

Second, verify source credibility. Not all accounts sharing information are equally reliable. Official government accounts, established news organizations, and subject-matter experts are more reliable than random users, viral accounts, and accounts created recently. Check account creation date, follow history, and previous posts before trusting new content.

Third, reverse image search suspicious images and videos. Google Images and Tin Eye can show you where an image previously appeared. This helps identify recycled content.

Fourth, look for consistent reporting across multiple sources. If only one source is reporting something, or if different sources tell contradictory versions, the situation is still uncertain. Be skeptical of any single-source claims.

Fifth, read the full article or context, not just headlines or clips. Sensationalized headlines often misrepresent the actual content. Quotes taken out of context mislead. Seeing the full story helps you understand nuance that misinformation strips away.

Sixth, question your own biases. Stories that align with your existing worldview are more likely to be believed even if they're false. Question those stories more intensely, not less. This cognitive bias (confirmation bias) is one of the most powerful forces driving misinformation spread.

Seventh, use trusted fact-checking resources. Snopes, Fact Check.org, Politi Fact, and others maintain databases of debunked misinformation. They update during major events and can help you verify claims quickly.

Eighth, be aware of your own certainty. If you're completely sure about complex events based on social media information, you're probably overconfident. Complex geopolitical events involve uncertainty. Real experts express uncertainty. Be suspicious of anyone who claims complete certainty about what happened.

The Role of Automated Tools in Detection and Amplification

Automated systems play a paradoxical role in the misinformation environment. The same types of algorithms that amplify misinformation could theoretically detect and demote it. But platforms have chosen to optimize algorithms for engagement rather than accuracy.

Automated detection systems already exist. They can identify known recycled footage by comparing against databases of previous uploads. They can flag suspicious engagement patterns (a post suddenly getting thousands of shares from similar-looking accounts in a short timeframe). They can use computer vision to identify images that have been previously flagged as misinformation.

But these systems require active maintenance and updating. Every new variation, new account, new distribution method requires system updates. This creates an ongoing cost that platforms would rather avoid.

Worse, automated systems generate false positives. They might flag legitimate content as misinformation. They might suppress accurate news that gets flagged by algorithms as suspicious. Over-reliance on automation creates new problems even as it solves the misinformation problem.

The Maduro event showed that platforms had some automated detection capability. Grok could identify the fake image. Google's detection could identify Synth ID watermarks. But these detections weren't automatically surfaced in user feeds. Users had to actively seek them out.

Meanwhile, the algorithms amplifying the false content ran unmodified throughout the event. Tik Tok's recommendation system continued boosting the fake arrest videos. X's algorithm continued amplifying the "Defense Intelligence" account's misleading post. Instagram continued displaying the original Ruben Dario post that started the cascade.

Comparative Analysis: How Different Platforms Handled the Crisis

The three major platforms involved—Tik Tok, Instagram/Meta, and X—had different responses and different structural approaches to the misinformation event.

Tik Tok's approach was primarily algorithmic amplification without intervention. The platform's algorithm boosted viral content, including the AI-generated arrest videos. The company made no public statements, issued no fact-check labels, and didn't remove content based on falsity (some might have been removed for other policy violations). The fast spread on Tik Tok reflects the platform's structure: short-form video, strong recommendation algorithm, and light moderation.

Meta (Instagram) had somewhat similar approach but with different mechanisms. The platform's Instagram suggested and recommended the original Ruben Dario post to users. However, Meta has been experimenting with reducing misinformation in feeds, so some false content might have been slightly deprioritized. The company didn't issue public statements about its response to the Maduro misinformation specifically.

X had the most detailed response in the sense that its Grok chatbot was analyzing the false images and providing corrections. But these corrections were visible only to users who specifically asked Grok to analyze an image. The platform's algorithmic amplification continued to boost high-engagement posts, including misinformation. X didn't apply warning labels or remove false content based on falsity alone.

Across all three platforms, there was a clear pattern: reactive correction (available if users seek it out) rather than proactive prevention (stopping amplification before it spreads widely).

What Comes Next: Policy Proposals and Realistic Solutions

Several policy proposals aim to address social media misinformation more directly. Some are realistic, others face significant implementation challenges.

Transparency Requirements: Platforms could be required to report what misinformation they removed, why, and how often. This would create accountability and public visibility into moderation decisions. The EU's Digital Services Act includes transparency requirements. But what constitutes misinformation remains contested, making this difficult to standardize.

Algorithm Auditing: Independent auditors could examine recommender algorithms to understand how content spreads. This could reveal whether platforms are inadvertently amplifying misinformation. But algorithm auditing is technically complex and proprietary algorithms are protected by companies as trade secrets.

Watermarking Requirements: AI-generated content could be required to include identifiable watermarks. This would help identify synthetic media. But watermark removal is technically feasible, and watermarking adds compliance costs that might slow beneficial AI use.

Friction During Breaking News: Platforms could implement temporary friction (slowed sharing, warning labels, reduced algorithmic boost) during declared crisis events. This would slow misinformation spread. But defining which events qualify, who declares them, and whether the friction actually helps are complex questions.

Mandatory Fact-Checking: Platforms could be required to fact-check major claims before they spread widely. This would require massive resources and hiring many fact-checkers. It also creates bottlenecks that could suppress legitimate news.

Platform Liability Reform: Changing Section 230 to make platforms liable for misinformation would create incentives for better moderation. But this could also lead to over-moderation and suppression of legitimate speech. Different countries' approaches (EU vs. US) would create conflicts.

Most realistic short-term improvements involve a combination of approaches: some technical improvements (better detection, watermarking), some regulatory pressure (especially transparency requirements), and some user education (teaching people to be skeptical of breaking news on social media).

Longer-term improvements require fundamental changes that platforms have resisted: investment in human moderation, accepting lower engagement in exchange for accuracy, and potentially restructuring business models.

FAQ

What exactly happened with Nicolás Maduro's capture?

On Saturday morning, Donald Trump announced that US troops had captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. Hours later, US Attorney General Pam Bondi announced indictments against both on charges including narco-terrorism conspiracy and cocaine importation. The capture triggered a wave of misinformation across social platforms including AI-generated images, synthetic videos, and recycled old footage presented as current events.

How did AI-generated images spread so quickly?

A single AI-generated image showing fake DEA agents arresting Maduro was shared across multiple platforms and served as the source for multiple video variations. Other creators took this image and used video generation tools to create moving video versions. Different creators made their own variations, leading to a cascade of related synthetic media all tracing back to the original false image. The combination of easy AI generation tools and strong algorithmic amplification created exponential spread.

Why didn't social media platforms remove the misinformation faster?

Platforms have systematically reduced moderation resources and fact-checking capabilities. Meta, Tik Tok, and X all declined to comment on their response to the Maduro misinformation. The companies face business model incentives favoring engagement over accuracy. Misinformation generates more engagement than accurate reporting, creating conflict between what platforms optimize for (engagement) and what would reduce misinformation (friction and accuracy prioritization).

How can I identify AI-generated images during breaking news?

You can use tools like Google's Synth ID watermark detector, reverse image search on Google Images or Tin Eye, or ask AI chatbots like Chat GPT or Claude to analyze suspicious images. However, most people won't perform these checks, which is why misinformation spreads so quickly. The most practical approach is to wait for fact-checkers to analyze breaking news rather than relying on images circulating on social media.

Why is recycled footage so effective as misinformation?

Recycled footage is effective because it contains authentic video of real events—just from the wrong time or place. The video itself is genuine, making it feel credible. Only the contextual framing is false. Identifying recycled content requires temporal context and often reverse video search capabilities that most social media users don't utilize. A 2024 video of protests, relabeled as 2025 footage, tells a completely different story.

What can individual users do to avoid spreading misinformation?

Implement a waiting period before sharing breaking news (30-60 minutes allows initial fact-checking). Verify source credibility before trusting information. Use reverse image search to check if images are recycled. Look for consistent reporting across multiple sources rather than single-source claims. Question information that aligns perfectly with your existing beliefs. And consult established fact-checking organizations like Snopes or Fact Check.org before sharing major claims.

How do platforms' business models create incentives for misinformation?

Platforms derive revenue from advertising based on user engagement. False information consistently generates more engagement (shares, likes, comments) than accurate information because it's more surprising and emotional. Addressing misinformation requires moderating engagement-driving content, which reduces revenue. This creates a direct financial incentive for platforms to allow misinformation to spread. Changing this would require fundamental business model restructuring away from engagement-based advertising.

What role did influencers play in spreading Maduro misinformation?

Influencers like Laura Loomer amplified misinformation by sharing it to their large follower bases. Influencers are incentivized to share engaging content, and misinformation often drives more engagement than accurate reporting. When a high-profile account with hundreds of thousands of followers shares something false, it reaches vastly more people than the original source. This amplification effect means that misinformation can spread to millions in hours through influencer networks.

Are there effective technological solutions to prevent misinformation?

Some technological solutions show promise: better AI detection systems for synthetic media, watermarking for generated content, and algorithms that reduce amplification of unverified claims. However, these create arms races with generation technology improving to evade detection. Full prevention isn't technically feasible, but significant slowing is possible. The challenge is that implementing these solutions costs resources that platforms have been reducing.

What would actually solve the social media misinformation problem?

No single solution exists. Realistically, improvements require combination of approaches: regulatory pressure forcing transparency and moderation investment, business model changes (subscription-based rather than ad-based), user education about media literacy, and significant investment in detection and human moderation systems. Each of these faces substantial obstacles. Long-term, we may need to accept that breaking news on social media will always be partially inaccurate, and users need to rely on traditional news sources for verification.

The Maduro capture misinformation event was significant not because it was unique, but because it was typical. This is how social media now handles major breaking news: a combination of synthetic media, recycled content, rapid spread, influencer amplification, and minimal platform intervention.

What we're seeing is a information environment fundamentally different from a decade ago. Then, social media was an amplifier of news broken by traditional media. Now, social media is the primary news source for billions, and it's increasingly unreliable during moments when reliable information matters most.

The technical capabilities to address this exist. The regulatory frameworks to enforce solutions partially exist. What doesn't exist is sufficient business incentive. Platforms have calculated that the reputational cost of misinformation is lower than the revenue cost of preventing it. Until that calculation changes, misinformation will continue to spread faster than corrections, false information will reach more people than truth, and users will face an information environment they can't reliably navigate.

This isn't inevitable. It's a choice that platforms have made, repeatedly, since 2016. We're living with the consequences of those choices every time major news breaks. The question isn't whether this problem can be solved. The question is whether the incentives to solve it will ever align with the capabilities that exist.

Key Takeaways

- AI-generated images and videos spread virally within minutes of major breaking news, reaching hundreds of thousands of people before any fact-checking occurs

- Social media platforms have systematically reduced content moderation and fact-checking teams, choosing engagement metrics over information accuracy

- Recycled footage from previous events is recontextualized as breaking news, and platforms lack systems to identify and flag previously-circulated videos

- Misinformation generates 5x more engagement than accurate content, creating direct financial incentives for platforms to allow false information to spread

- Users can reduce misinformation exposure by implementing waiting periods, verifying sources, using reverse image search, and consulting fact-checkers during breaking news

Related Articles

- Why Quitting Social Media Became So Easy in 2025 [Guide]

- AI Chatbots and Breaking News: Why Some Excel While Others Fail [2025]

- Instagram's AI Media Crisis: Why Fingerprinting Real Content Matters [2025]

- AI Accountability Theater: Why Grok's 'Apology' Doesn't Mean What We Think [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness Role: What It Means and Why It Matters [2025]

- Satya Nadella's AI Scratchpad: Why 2026 Changes Everything [2025]

![How Disinformation Spreads on Social Media During Major Events [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-disinformation-spreads-on-social-media-during-major-even/image-1-1767465284217.jpg)