The Day Anthem Died: What Happened When EA Pulled the Plug

On January 12, 2025, something changed forever for the Anthem community. EA didn't announce it with fanfare or apologies. They just quietly flipped a switch, and the multiplayer servers that kept BioWare's sprawling sci-fi adventure alive went dark. No warning to the thousands of players still logging in. No countdown timer. Just gone.

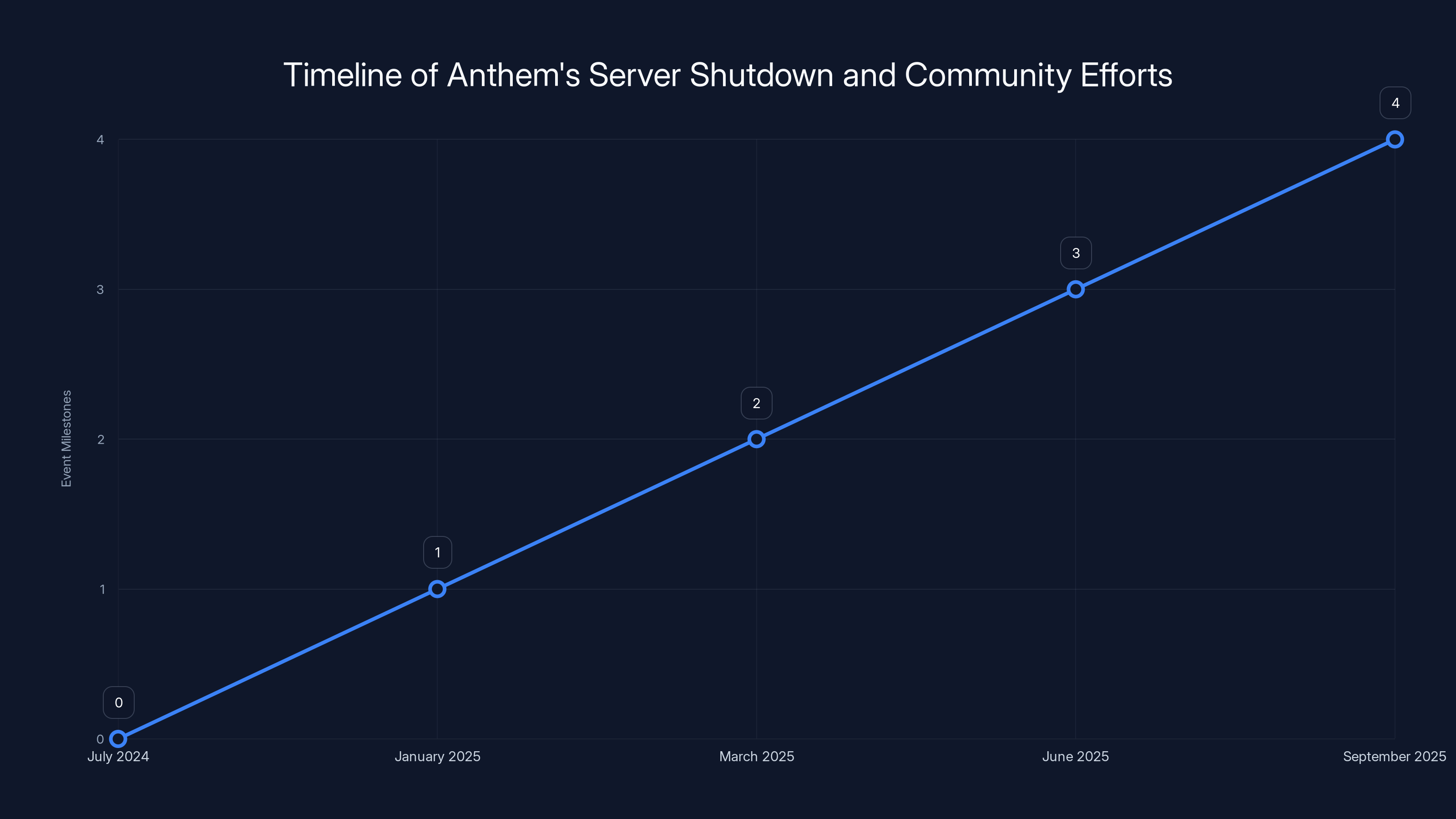

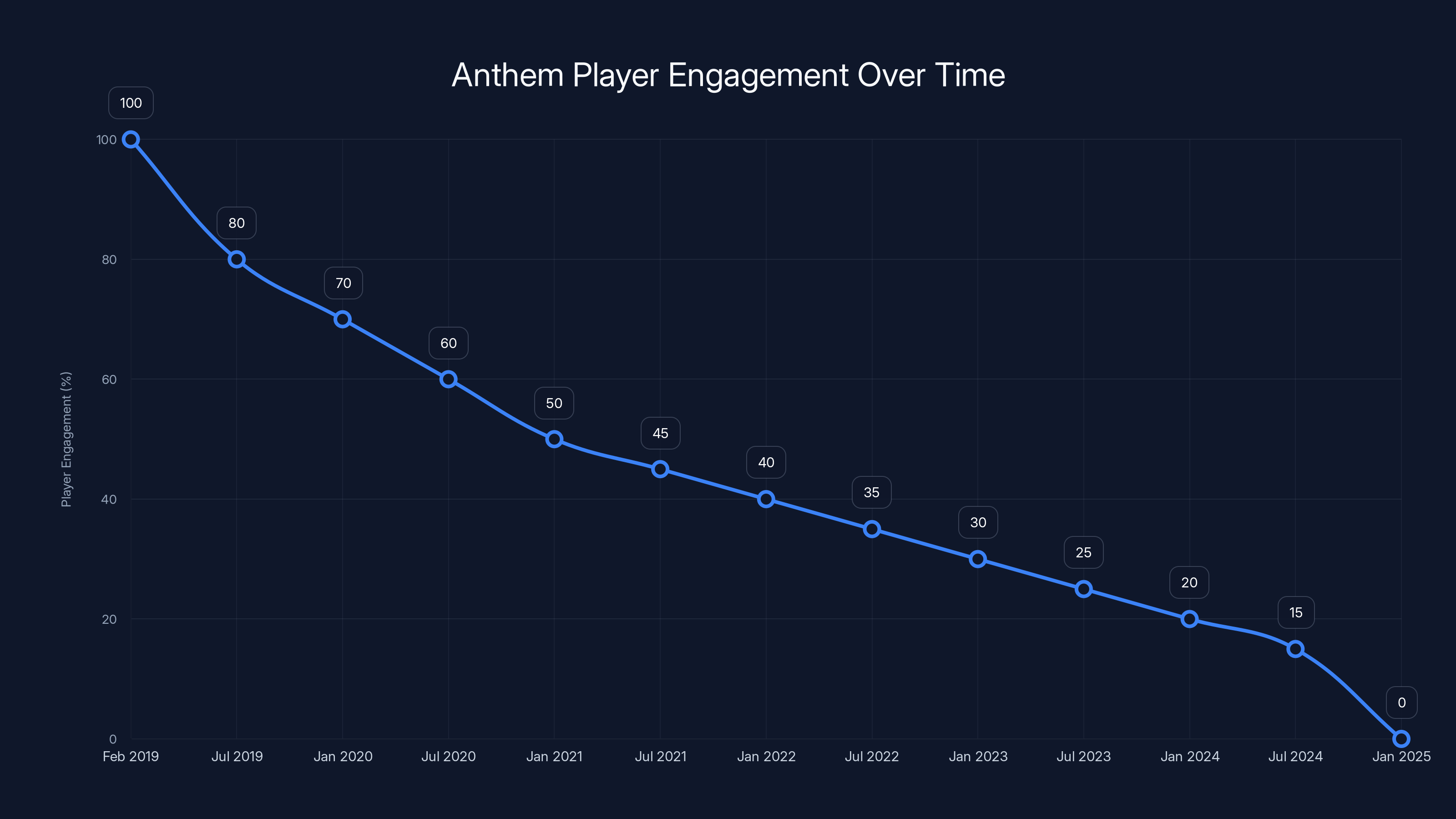

For anyone who bought Anthem expecting years of updates and seasonal content like Destiny or The Division, this moment must have felt like a punch in the gut. The game that launched in February 2019 with ambitions of becoming the next live-service phenomenon never really got there. Years of rough launches, broken promises, and community frustration led to this inevitable end. When the shutdown announcement came in July 2024, most people figured Anthem would be dead and buried within months, as noted by GameSpot.

Then something unexpected happened.

Within days of the server shutdown, a proof-of-concept video surfaced online showing Anthem actually loading on a private server. Real menus. Real character data. Real gameplay systems firing up without any connection to EA's infrastructure. It was rough around the edges, glitchy in places, and far from finished. But it worked. Even partially. Even theoretically impossible, the community had done what seemed unthinkable: they'd brought Anthem back from the dead.

The team behind this resurrection calls themselves The Fort's Forge, a Discord server where volunteer engineers and developers have been tearing apart Anthem's code like computer archaeologists, searching for the blueprints that might bring the game back to life. But here's what the viral proof-of-concept video doesn't show you: the absolute nightmare of complexity hiding beneath the surface. The real story isn't about triumph. It's about discovering that saving Anthem is far, far harder than anyone expected.

Laurie, the project administrator who helped organize The Fort's Forge, told me directly: "People are getting excited, and naturally people are going to get their hopes up. I don't want to be the person that's going to have to deal with the aftermath if it turns out that we can't actually get anywhere."

That anxiety isn't pessimism. It's realism. Because once you start digging into how Anthem actually works, you realize how deeply EA's proprietary Frostbite engine is baked into every single system. And that's where the problem starts, as detailed in IGN.

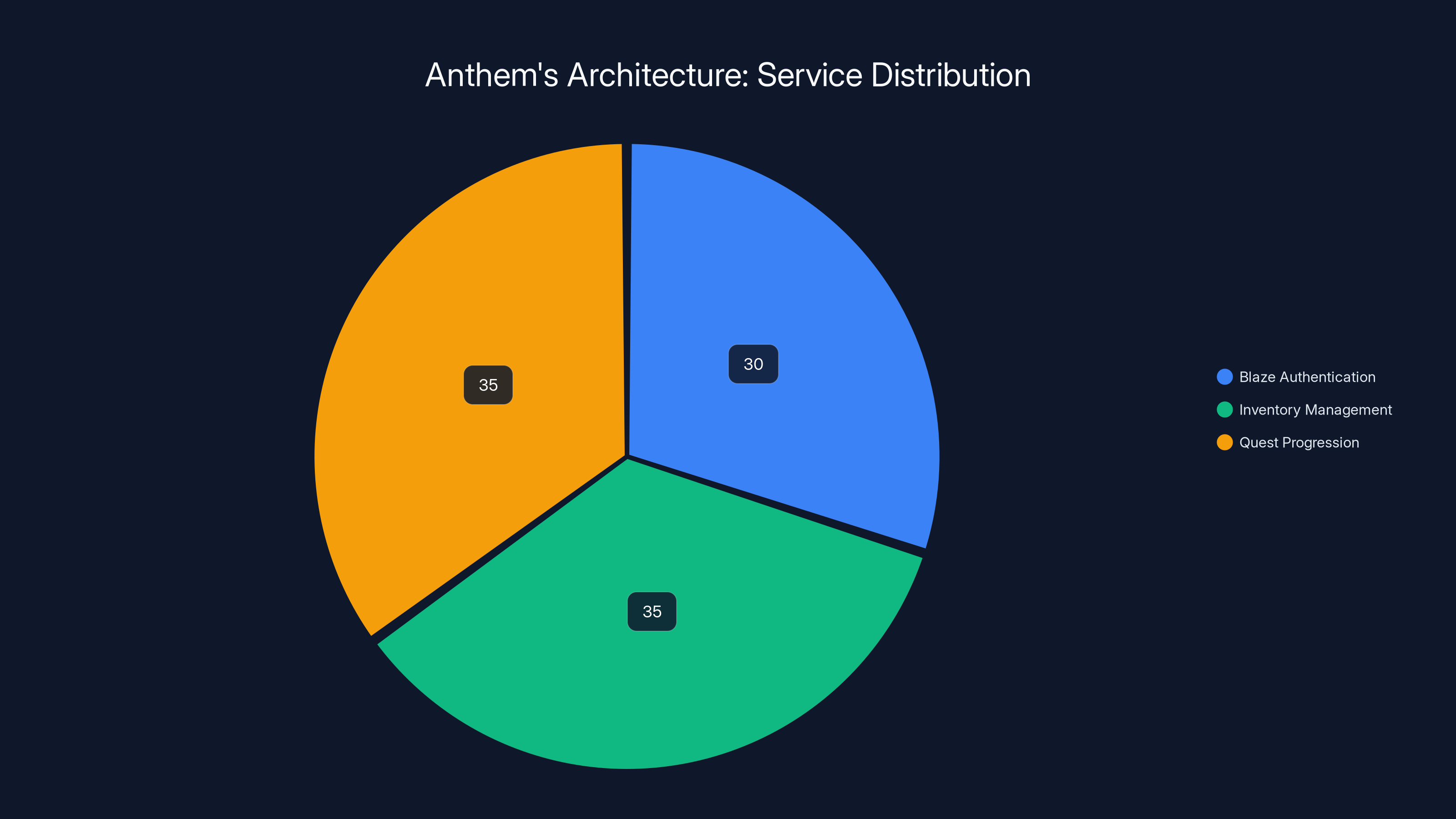

Understanding Anthem's Architecture: Three Distinct Services Holding It Together

When The Fort's Forge started analyzing Anthem's network traffic in September 2024, they realized the game wasn't some monolithic beast. Instead, it relied on three separate but interconnected services working in concert. Understanding these services is critical to understanding why bringing Anthem back online is such a technical nightmare.

The Blaze Authentication Server

The first service is called Blaze, and it's EA's answer to player authentication. Think of Blaze as the bouncer at an exclusive club. When you try to launch Anthem, the game client reaches out to Blaze and essentially says: "Hey, I'm player X with these credentials. Do I have permission to log in?" Blaze checks its database, confirms you own the game, verifies your account hasn't been banned, and either waves you through or shuts you down.

In the original architecture, Blaze handled the basic handshake. It didn't store inventory data. It didn't track quest progression. It just confirmed identity and authorized access. From a reverse-engineering perspective, this is the easy part. Ness 199X and the Fort's Forge team were able to emulate basic Blaze functionality relatively quickly because the authentication flow is standardized and well-understood.

The challenge with Blaze isn't the concept. It's that EA implemented it with specific security requirements, encryption protocols, and specific response formats that Anthem's client expects. Get the format wrong by a single byte, and the client rejects it. Get the encryption wrong, and the handshake fails. But once The Fort's Forge reverse-engineered how Anthem's particular implementation worked, they could replicate it.

Andersson 799, one of the developers working on the proof-of-concept, said he was able to craft Blaze responses by simply replaying captured network packets. "I basically made the tool to just simply reply with the packet captures that I got," he explained. That simplicity is deceptive. It only works if you understand exactly what the client is expecting and can provide exactly that response, nothing more, nothing less.

BioWare Online Services (BIGS): The Inventory and Progression Backbone

Once you're authenticated through Blaze, the second service kicks in. BioWare Online Services, abbreviated as BIGS, is essentially a JSON web server that tracks everything about your character: inventory, experience points, quest progression, cosmetics, crafting materials, and every other piece of persistent data that makes your character feel like yours.

BIGS is more complex than Blaze because it needs to store, retrieve, and update massive amounts of character data dynamically. When you complete a mission, BIGS records that. When you craft new equipment, BIGS updates your inventory. When you earn experience, BIGS increments your level counter. All of this happens with hundreds or thousands of players simultaneously, so BIGS needs to handle concurrent requests efficiently without corrupting data.

From The Fort's Forge's perspective, BIGS is more manageable than the Frostbite engine itself because it's essentially just a database with an API layer on top. JSON web servers are well-understood technology. The team can intercept network traffic, see what data Anthem's client is requesting, and figure out how to serve that data locally.

But here's where it gets interesting: player character data becomes inconsistent across different systems. A player might have logged 50 hours into Anthem before the servers shut down. The Fort's Forge wants to ensure that when Anthem comes back online, that player logs in and finds their character exactly as it was left. Ness mentioned that contributors to the project who used his packet logger tool in September should be able to fully recover their characters if and when a playable version emerges. That's a meaningful promise because it suggests the team has a way to preserve and restore the actual character data people invested time into building.

The Frostbite Multiplayer Engine: Where Everything Falls Apart

Here's where things get genuinely terrifying for The Fort's Forge.

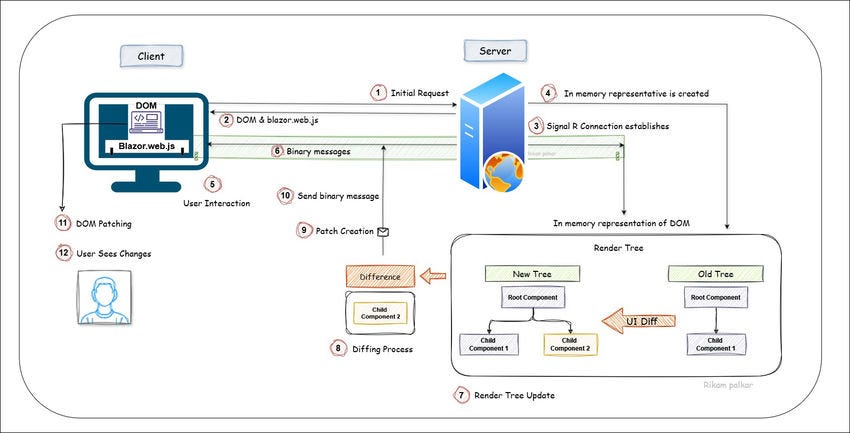

The first two services, Blaze and BIGS, are relatively contained problems. They're authentication and data storage, and those are solved problems in computer science. But the third service, the Frostbite multiplayer engine itself, is where Anthem's architecture does something fundamentally unusual.

Frostbite is a game engine built by DICE and evolved by EA over nearly two decades. It powers everything from Battlefield games to Mass Effect: Andromeda to Star Wars: The Old Republic. But here's the weird part: Frostbite doesn't distinguish cleanly between client and server. Instead, it runs gameplay in what EA calls a "server context," and that context can exist either locally on your machine or remotely on EA's servers.

This is where Ness 199X explained something that made The Fort's Forge's challenge click into sharp focus. "Due to how Frostbite is designed, all gameplay in a Frostbite game runs in a 'server' context," he told me. "Even in a single-player game like Mass Effect: Andromeda, the client just creates a separate server thread and pipes all the traffic internally."

In single-player Frostbite games, the engine creates a local server instance on your machine and has the client communicate with that local server as if it were remote. But Anthem was designed as a multiplayer game from the ground up, so all that level loading, NPC spawning, player positioning, and real-time gameplay state was handled by remote servers at EA's data centers.

Andersson 799 ran into this immediately when testing. "The game couldn't load into the level without that data," he said, referring to the critical server-side data that Anthem needed to function. This isn't a small problem. This is the entire foundation of how Anthem plays.

But Ness sees a potential path forward. He noticed that Fort Tarsis, Anthem's social hub area where players gather between missions, actually runs offline using local data. The game pipes that local data through a local "server" thread, and Fort Tarsis works fine without connecting to EA's systems. This suggests something crucial: maybe all of Anthem's level data exists in the client already, dormant and waiting to be awakened, as discussed in Polygon.

Estimated data showing the distribution of responsibilities among Anthem's core services. Blaze handles authentication, while other services manage inventory and quest progression.

The Hidden Complexity: Why Anthem Doesn't Behave Like Other Frostbite Games

Here's the frustrating part for The Fort's Forge: Anthem acts like a standard Frostbite game in most ways, but then it does bizarre things that make reverse-engineering it feel like trying to follow a map that occasionally contradicts itself.

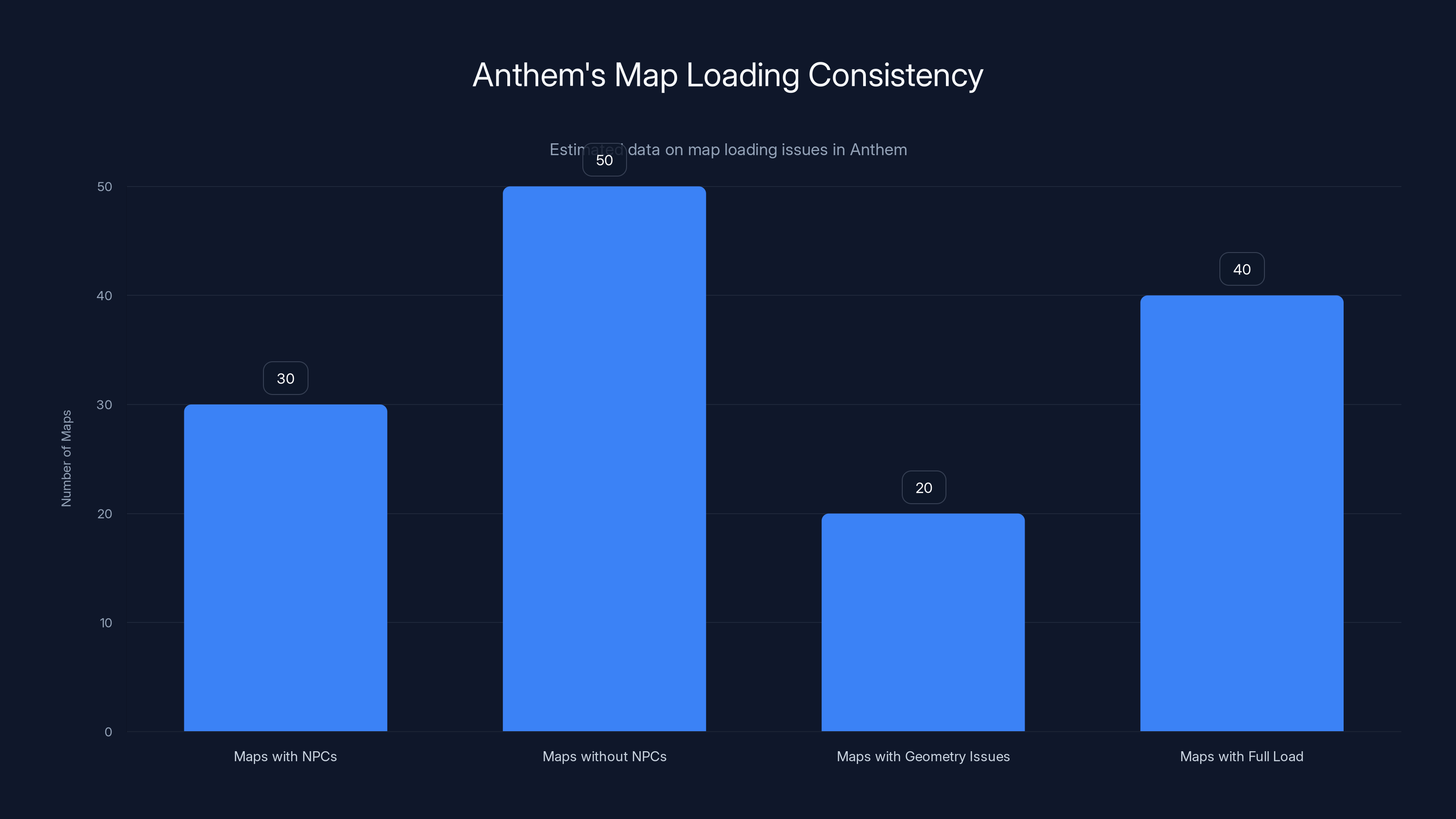

When Ness and the team tried loading different mission maps, they encountered bizarre inconsistencies. Some maps would spawn NPCs correctly. Other identical-looking maps would spawn nothing. The game would load the level geometry fine but fail to populate the world with enemies, civilians, or interactive objects. Every time they investigated, they'd hit dead ends.

"For example, when we try to load most maps, no NPCs spawn, but in some maps they do," Ness explained with a mixture of frustration and intrigue. "And we have yet to determine why."

These aren't bugs in The Fort's Forge's emulation. These are the actual quirks of how Anthem's networking was implemented. Somewhere in Anthem's code, there's logic that determines when to spawn NPCs and when to skip them. The team can see the effects of that logic, but they can't pinpoint the cause.

Ness has a theory. Anthem, being an online RPG, keeps extensive player data as part of its runtime state. Quest progression, collected items, completed objectives, character progression, cosmetics applied—all of this exists not just in BIGS but potentially in the game's session state as well. When the game tries to load a level, it might reference that player data to determine what NPCs should appear, what objectives are active, what environmental changes have been made. If any of that data is malformed or missing, the game might bail on spawning NPCs rather than showing the wrong ones.

"To be honest we're not entirely sure how deep the connection goes," Ness admitted, acknowledging the limits of what reverse-engineering can reveal when you don't have source code or documentation.

This is where Anthem's design philosophy works against preservation efforts. The game wasn't built with modularity in mind. Every system is intertwined with every other system. You can't isolate the NPC spawning logic from the player progression logic from the quest tracking logic. Pull one thread and you might unravel the whole thing.

This timeline illustrates the progression from the announcement of Anthem's server shutdown to ongoing community preservation efforts. Estimated data.

The Proof of Concept: What Actually Works Right Now

Despite all these obstacles, The Fort's Forge managed to create something that stunned the gaming community: a working Anthem server, even if it's barely functional.

Andersson 799 built what he calls a "barebones Anthem private server" using the packet captures he'd collected during his testing. He set up basic Blaze emulation to handle authentication. He got BIGS responses working well enough to load player profiles and basic character data. And then, somehow, he got Anthem to actually boot up, load into the social hub, and display character information.

The video he posted showed real menus. Real character models wearing real cosmetics. Real player names and profile data. It wasn't polished. The interface looked janky, probably because of missing textures or rendering issues. But it was unmistakably Anthem running on infrastructure that wasn't controlled by EA.

When Andersson loaded the game with his private server setup, the client connected. It authenticated. It pulled character data. And it entered the game world. That's not theoretical anymore. That's proof.

But here's the crucial caveat: this only works in the safe zone. Fort Tarsis, the social area, works because it doesn't require the Frostbite multiplayer engine to do complex things. It's a relatively static environment. The proof-of-concept doesn't actually show anyone loading into a mission and playing. Nobody's fighting enemies. Nobody's completing objectives. Nobody's experiencing Anthem as a playable game.

That's the distance between proof-of-concept and actual revival. It's the distance between saying "yes, this can technically work" and actually making the game playable again, as discussed in IGN India.

The Client-Server Architecture Problem: Data Dependency and Runtime State

Here's the architectural nightmare that keeps The Fort's Forge awake at night: Anthem's client and server are deeply entangled in ways that most modern games explicitly avoid.

In a well-designed multiplayer game, the client is essentially dumb. It displays graphics, handles input, and sends commands to the server. The server processes those commands, updates game state, and sends back the results. The client trusts the server absolutely. If the server says you don't have an item, you don't have it. If the server says an enemy is at position X, that's where it is.

But Anthem was built with a different philosophy. The engine itself, Frostbite, was designed to run "server contexts" locally or remotely interchangeably. This means Anthem's client needs to have a lot of self-contained game logic. It needs to be able to run missions locally if necessary. It needs to have NPC AI, physics simulations, and world state management baked in.

The problem is that all of this local simulation was still dependent on server-provided data. The server would initialize the simulation with mission parameters, NPC configurations, environmental settings, and player progression data. The client would then run that simulation forward, but the outcome was always tethered to what the server provided initially.

When The Fort's Forge tries to recreate that, they need to not just emulate the server responses but understand every single piece of initialization data that the original server provided. They need to know not just what the server said, but why it said it, because Anthem's client logic was built around those specific responses.

This is why local level data is so critical. If Ness is right that all the mission logic exists in the client already, then The Fort's Forge might be able to bypass the complex server initialization by simply enabling that dormant code. But that "if" is doing a lot of work, and they're not certain yet.

Estimated data shows that a significant number of maps in Anthem fail to load NPCs, highlighting the game's complex loading logic. Estimated data.

Crowdsourced Preservation: How Packet Logging Changed Everything

One of the smartest moves The Fort's Forge made was releasing a packet logger tool in September 2024. This tool lets individual players capture their own network traffic between their Anthem client and EA's servers. It's a surprisingly elegant solution to a difficult problem.

Why does this matter? Because raw packet data is the closest thing to primary source material you can get in game preservation. It's not a decompiled executable that might be incomplete or corrupted. It's not reverse-engineered code that might be missing context. It's the actual data flowing between the client and server, exactly as they spoke to each other when Anthem was alive.

When you run the packet logger, you're capturing the authentic conversations between Anthem's systems. You see what the client asks for. You see what the server responds with. You see the exact formats, the exact values, the exact timing. Over time, as dozens or hundreds of players logged their packets, a mosaic of real data accumulated. This crowdsourced dataset became invaluable evidence for understanding how Anthem actually worked.

It also serves another purpose: preservation of individual player progress. Those packet logs contain character data. If a player logged their packets before the shutdown, their character data is now preserved forever. When (or if) Anthem comes back online, those players might actually be able to recover their characters exactly as they left them. Ness promised this explicitly, which is a meaningful gesture toward the players who invested time in the game.

This approach to preservation is novel. Most game preservation happens through emulation of old hardware or reverse-engineering of legacy code. But crowdsourced packet logging is something different. It's a way for the community to collectively document how a game worked before it dies, creating a distributed archive that no single entity controls.

The Broader Implications: Why This Matters Beyond Anthem

The Anthem revival effort is significant for reasons that extend far beyond one abandoned game. It's about gaming preservation, corporate control, and whether players have any right to keep playing games they paid for.

When EA shut down Anthem's servers, the company technically had every right to do so. The game's terms of service almost certainly state that server access is provided "as is" and can be discontinued at any time. Players never actually owned Anthem. They licensed it. The moment EA decided that running Anthem's servers wasn't profitable, the company pulled the plug.

This is increasingly the normal state of affairs in gaming. Destiny 2 will eventually shut down. Anthem has already shut down. Blizzard shut down World of Warcraft's Vanilla servers years ago. Server closures are becoming routine. Any game that depends on central servers is fundamentally at risk of disappearing forever.

The Fort's Forge is saying: no, that's not acceptable. Games should persist. They should be preserved. Cultures invest in these games, communities form around them, and when they disappear, something of value is lost.

This isn't just nostalgic thinking. Libraries preserve books. Museums preserve art. Archives preserve historical documents. Why shouldn't games, which are increasingly recognized as art and cultural artifacts, be preserved the same way?

The challenge is that games are different from books or movies. They're interactive. They change. They're often designed to be experienced as part of a service rather than a standalone product. Preserving a game for historical and cultural reasons is exponentially harder than preserving a film or a novel.

But The Fort's Forge is proving it's possible. Even with incomplete information and no official cooperation from EA, motivated volunteers are managing to resurrect a complex multiplayer game. That's a statement about what's possible when preservation is treated as important enough to invest time and effort into, as highlighted by Ars Technica.

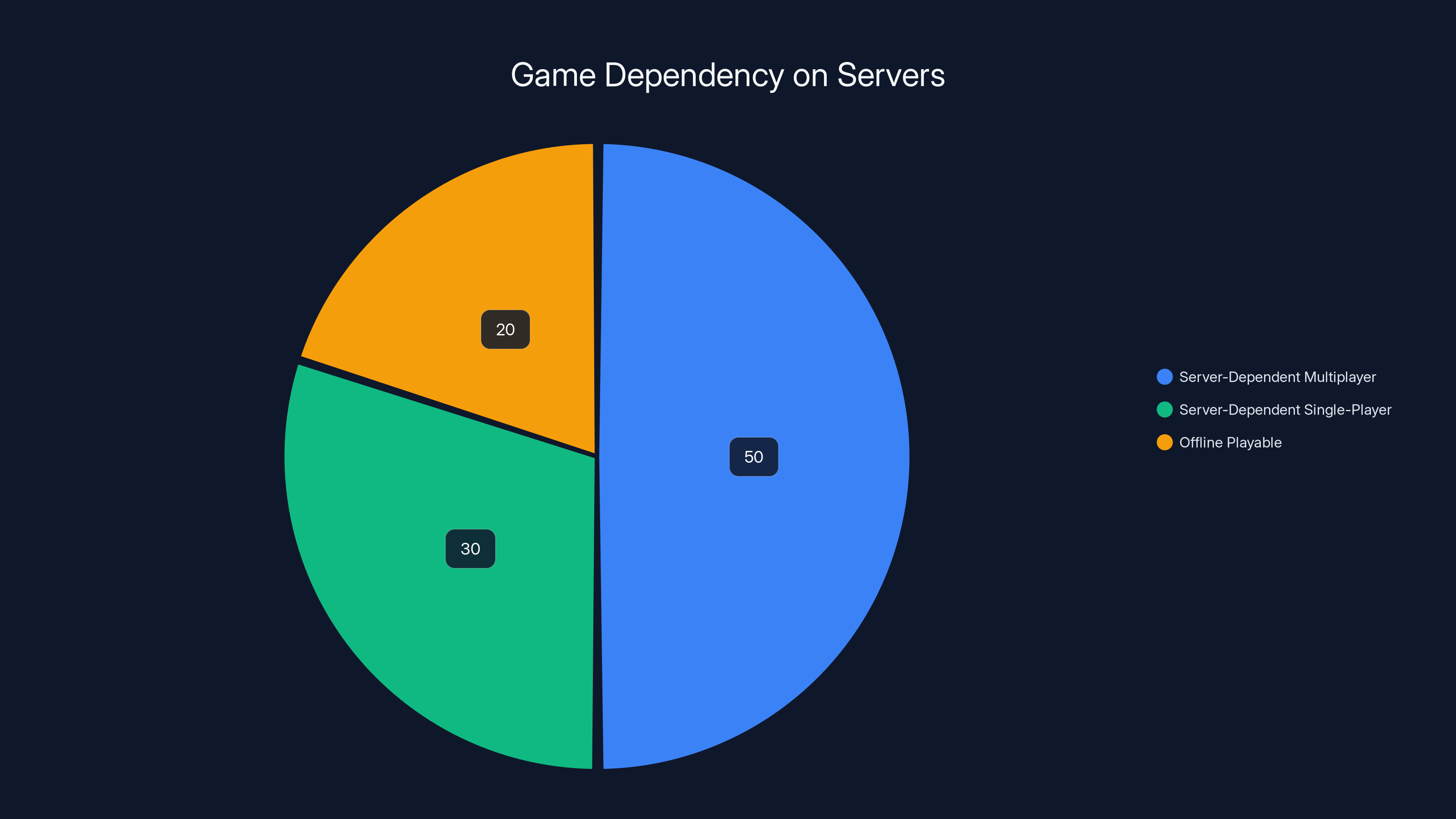

Estimated data shows that 80% of modern games require server connectivity, highlighting the industry's shift towards server-dependent gaming experiences.

EA and BioWare's Position: Why the Company Wants This Dead

It's worth understanding EA's perspective here, not to defend it, but to understand the incentives at play.

EA spent significant resources building and maintaining Anthem's servers over the better part of a decade. The game was a financial disappointment, and keeping those servers online represented pure cost with no revenue return. From a business perspective, shutting down servers for an unsuccessful game makes perfect sense. Why spend money on something that generates no income?

But there's another layer to this. Anthem's shutdown might also be partly about legal liability and corporate control. If The Fort's Forge successfully revives Anthem as a fully playable private server, that raises questions about why EA spent money on official servers in the first place. If a small team of volunteers can do it, the optics aren't great.

There's also the intellectual property question. Anthem's code, assets, and design are all proprietary EA/BioWare property. Every aspect of The Fort's Forge's work exists in a legal gray area. The team isn't distributing the game itself, just tools and documentation for reverse-engineering it. But EA could theoretically send cease-and-desist letters if it wanted to shut down the project.

The fact that EA hasn't done so yet might reflect either that the company doesn't consider The Fort's Forge a significant enough threat to bother, or that EA has chosen, informally, to look the other way. Some game companies (like Jagex with RuneScape private servers) aggressively pursue preservation efforts. Others effectively tolerate them.

EA's public statements on Anthem's shutdown were minimal. No apologies, no offers to open-source the game, no collaboration with preservation efforts. Just operational efficiency: the servers are being decommissioned, please stop playing.

The Technical Roadmap: What The Fort's Forge Is Actually Trying to Accomplish

When you talk to Ness and Andersson about their actual goals, it becomes clear that there's a roadmap, even if it's more aspiration than confirmed plan.

The immediate goal, basically achieved, is getting the authentication and player data systems emulated well enough that players can log in and see their characters. That's proof-of-concept territory, and they're there.

The next tier is getting basic level loading to work. Ness believes that the level data and associated logic might already exist in the client. If that's true, the team could patch the client to enable those local systems and bypass the need for remote servers. This would be the critical step: moving from "you can log in" to "you can actually play."

The third tier is full mission functionality: enemies spawning correctly, quests tracking properly, loot dropping consistently. This is where that mystery of selective NPC spawning becomes critical. Until The Fort's Forge figures out why some maps spawn NPCs and others don't, they can't confidently enable all missions.

The final tier, if they even get there, is online multiplayer. Fort Tarsis is offline-capable, but Anthem's actual gameplay involves up to four players cooperatively flying around in Javelins, fighting enemies and collecting loot. Implementing peer-to-peer multiplayer or a distributed server infrastructure would be exponentially more complex than the single-player mission loading they're currently working on.

Each of these tiers has compounding complexity. But notably, Ness and Andersson seem to think tier two is actually achievable. They have evidence that level data exists in the client. They have proof that the game can run locally. The path isn't clear, but it's not impossible either.

Here's the thing that makes this remarkable: they're doing this with zero official support, incomplete information, and without access to EA's source code. If they succeed even partially, it will be because they figured out, through sheer determination and technical skill, how to make an EA game work without EA's permission or collaboration.

Estimated data suggests a balanced likelihood of EA taking various actions against The Fort's Forge, with no action being equally probable.

The Frostbite Engine Problem: Why EA's Own Technology Is the Real Obstacle

Here's an irony that probably isn't lost on anyone at EA: the company's proprietary Frostbite engine, built over years as a competitive advantage, is now the thing making it hardest to preserve Anthem.

In many ways, Frostbite is a brilliant engine. It powers some of the industry's most successful franchises. But it was designed with certain assumptions that make preservation difficult. The blurred client-server boundary, while potentially elegant for some use cases, creates exactly the kind of architectural entanglement that makes reverse-engineering a nightmare.

If Anthem had been built on a more standard architecture with clear separation between client and server, The Fort's Forge's job would be simpler. They could stub out the server, provide the necessary responses, and call it done. But Anthem requires understanding not just what data the server provides, but how the client uses that data in intricate ways.

Frostbite also likely uses custom serialization formats, custom networking protocols, and custom optimization tricks that don't translate well to different environments. What works perfectly when both the client and server are running identical Frostbite code becomes fragile when you're trying to emulate one side with a different system.

This raises a broader question: should game companies design systems with preservation in mind? Should they build games in modular ways that allow them to be preserved later? Should they use standard protocols and open formats instead of proprietary systems?

The answer is probably yes, but it's a long-term structural change that would require companies to deprioritize short-term competitive advantage for long-term preservation. And that's not a trade EA seems willing to make, given how completely they shut down Anthem's infrastructure.

The Human Element: Why Volunteers Are Doing EA's Job

Perhaps the most surprising thing about The Fort's Forge is that it exists at all. Why would dozens of developers spend unpaid hours trying to resurrect a game that most people have already abandoned?

Laurie's answer was telling: the initial motivation was "little more than spite for EA and BioWare." That's refreshingly honest. The team wasn't motivated by love of Anthem specifically. They were motivated by outrage at the principle that a game, once bought and played, could simply be deleted from existence without consent.

But that initial spite evolved into something else: genuine technical interest. Ness, who admits he "never really played much Anthem" before learning it was shutting down, became fascinated by the reverse-engineering challenge. Andersson 799 brought years of Frostbite knowledge to bear on a problem he'd never encountered before.

And there's something else: preservation ethics. These volunteers see themselves as custodians of culture. Games matter to people. Anthem mattered to thousands of players who formed friendships, invested time, and engaged with creative works. Letting that disappear seemed wrong.

This is worth contemplating from a corporate perspective. EA outsourced game preservation to volunteers because the company had no interest in doing it themselves. The players are so committed to their game that they're doing the preservation work that a multibillion-dollar company won't do.

It's simultaneously impressive and infuriating. Impressive because it shows what community motivation can accomplish. Infuriating because it reveals that we've normalized corporate abandonment of digital products and expect individual enthusiasts to clean up the mess.

Anthem's player engagement steadily declined from its launch in February 2019 until the server shutdown in January 2025. Estimated data shows a significant drop in player numbers over the years.

The Legal Gray Area: Preservation Rights vs. Intellectual Property

Here's where things get murky. The Fort's Forge isn't breaking any laws that I can identify, but they're not operating in clear legal territory either.

The project doesn't distribute Anthem itself. They don't provide copies of the game client. What they're doing is creating tools to reverse-engineer the game's protocols and potentially patching the client to enable offline functionality. That's a very different thing from piracy.

But it does involve analyzing proprietary code. It involves understanding how EA's systems work. It potentially involves circumventing access controls. The DMCA has provisions against circumventing technical protection measures, and depending on how those protections are structured, The Fort's Forge's work might theoretically violate the law.

In practice, EA would almost certainly need to take action to enforce its legal rights. The company could send cease-and-desist letters. It could threaten legal action. It could argue that The Fort's Forge's work violates intellectual property law and demand that the project be shut down.

So far, it hasn't. Whether that's because EA doesn't care, doesn't notice, or is strategically choosing to let this play out is unclear. But the legal ambiguity hangs over the project nonetheless.

This highlights why preservation infrastructure should probably come from official sources. If EA wanted to ensure that Anthem could be preserved, the company could open-source critical systems, provide documentation, or license the game for preservation purposes to organizations like the Library of Congress or Internet Archive. But that requires companies to think beyond quarterly earnings and consider long-term cultural impact.

What Success Would Look Like: Different Scenarios and Outcomes

When we talk about "reviving Anthem," what does that actually mean? The answer is less clear than it might seem.

Scenario one is the "Fort Tarsis" scenario: The Fort's Forge successfully emulates enough of EA's backend that players can log in, see their characters, and hang out in the social hub. The game runs locally but offline and single-player only. This is already partially achieved.

Scenario two is the "offline campaign" scenario: players can load into missions and experience Anthem's storyline solo. NPCs spawn correctly. Loot drops. Progression tracks. This would make Anthem a fully playable single-player game again, divorced from the original multiplayer experience but meaningful nonetheless.

Scenario three is the "multiplayer restored" scenario: The Fort's Forge figures out how to implement cooperative multiplayer, either peer-to-peer or through a community-run server. Four players can jump into Javelins, fly through Anthem's world, fight enemies together, and experience the game as it was originally designed. This is the dream scenario and also the most technically difficult.

Each of these represents exponentially more work. Scenario one they're close to. Scenario two they're actively pursuing. Scenario three is probably years away, if possible at all.

The reality is that The Fort's Forge might achieve something in between. A playable Anthem that's 80% as good as the original, with limitations and quirks but genuinely fun to play. That would still be a success. It would prove the principle that community-driven preservation can work for complex modern games.

But here's the optimistic ceiling: even if The Fort's Forge succeeds completely, only a fraction of Anthem's former player base will probably ever play it. Most people have moved on. The window to save Anthem as a living game has probably already closed. What The Fort's Forge is trying to do isn't bring Anthem back as a service. It's preserve Anthem as a historical artifact and a playable game for anyone who wants to experience it.

That's preservation in its most meaningful form.

The Broader Gaming Industry Context: When Does a Game Die?

Anthem is just one data point in a larger trend: increasingly, games have expiration dates.

Once upon a time, games were products. You bought them and you owned them. They ran offline or connected to servers, but the servers weren't essential to the product continuing to exist. If you had Super Smash Bros. on cartridge, you could play it forever.

Modern games are increasingly services. They require authentication. They require server connectivity for features you might care about. They get updated continuously. The day the servers shut down, the game effectively ends, even though your copy of the software still exists on your hard drive.

This shift has happened gradually, but it's now near-total. Most modern multiplayer games are server-dependent. Many single-player games require authentication or require online features. Some games are designed so that critical content is downloaded from servers that can theoretically disappear at any time.

The gaming industry has essentially decided that games don't need to be permanent. They need to be profitable while they're active and then disposable once they're not. Digital media companies have gotten really good at normalizing this.

Anthem is extreme because the game is completely unplayable without servers. But it's also just an obvious example of a trend that affects most modern games to some degree. Destiny will shut down eventually. Overwatch 2 will shut down eventually. Even World of Warcraft will shut down eventually, and when it does, thousands of hours of collective human experience in that world will effectively vanish.

The Fort's Forge's effort to preserve Anthem is implicitly an argument that this situation is wrong. That games should be designed to be preservable. That companies should plan for what happens when a service shuts down. That players should have some right to keep playing games they bought.

It's a radical position in gaming's current corporate environment. Most companies would never voluntarily cede control over their games like that. But The Fort's Forge's success, even partial success, might change the conversation.

The Emotional Labor: Why This Matters to Communities

All the technical discussion in the world misses something important: Anthem meant something to people.

Yes, the game had problems. Yes, it never reached its potential. But players invested time in Anthem. They formed friendships. They created communities. Some people probably played Anthem as a refuge during difficult times. The game was woven into people's lives.

When EA shut down the servers, the company sent a message: your investment means nothing. Your community means nothing. The experience you shared means nothing. Once we stop profiting from this, it stops existing.

That's brutal, honestly. It's treating games purely as commodities with no cultural or personal value. It's stripping away agency from players and treating them as renters rather than owners of the experiences they participate in.

The Fort's Forge's project is partly technical, sure, but it's also an act of resistance. It's saying: this game mattered, and we're not letting it disappear just because a corporation decided it's not worth the server costs anymore.

That emotional dimension is worth acknowledging because it's probably the real driving force behind the project. Technical skill is necessary, but passion is what keeps people working on something when it's difficult and time-consuming and they're not getting paid.

Laurie's anxiety about managing expectations makes more sense in this light. The project isn't just a technical challenge. It's carrying the hopes of a community. People are watching and hoping and imagining playing Anthem again. That's a lot of weight to carry.

The Long Road Ahead: What The Fort's Forge Needs to Do

If you're asking whether Anthem will come back online and be fully playable, the honest answer is: probably not completely, but maybe enough.

The Fort's Forge has a clear roadmap, roughly sorted by difficulty:

First, they need to fully understand and emulate the Blaze and BIGS systems. They're mostly there, but some edge cases and specific data fields probably need refinement. This is a solvable problem.

Second, they need to figure out the NPC spawning mystery. Why do some maps spawn NPCs and others don't? This is likely about understanding dependencies between player progression data and game state. Once they solve this, they'll know a lot more about how Anthem's underlying systems interact.

Third, they need to enable or recreate the local mission logic. Ness believes this logic exists in the client already. If so, it's a matter of understanding how to activate it. If not, they'll need to reverse-engineer mission logic from game behavior, which is much harder.

Fourth, they need to handle the random problems they haven't anticipated yet. When reverse-engineering complex systems, you always discover surprises. There will be subsystems nobody expected, cryptic data structures that don't make sense, special cases that contradict the general rules.

Fifth, if they've made it this far, they might consider multiplayer. But that's almost certainly a "someday" goal rather than an immediate one.

Each of these steps requires sustained effort from people who aren't being paid. It requires technical expertise that's rare and specialized. It requires patience when things don't work and optimism when progress stalls.

Will The Fort's Forge complete the entire roadmap? Honest answer: probably not. Will they get far enough to give players something meaningful? That's more likely.

The Future of Game Preservation: What Anthem Teaches Us

The Anthem revival effort teaches several important lessons about game preservation going forward.

First, preservation is possible even without official support. The Fort's Forge is proving that motivated volunteers can reverse-engineer complex systems and make dead games playable again. This is an existence proof. It means future preservation efforts can reference this as an example.

Second, preservation requires the right kind of technical expertise. Not everyone can do what Ness and Andersson are doing. This creates a bottleneck. We need more people learning these skills, and we need institutions (universities, archives, preservation organizations) treating reverse-engineering and game preservation as legitimate fields of study.

Third, preservation is easier if companies cooperate. The Fort's Forge is working against EA at every step, trying to figure out proprietary systems with no official documentation. Imagine how much faster preservation could happen if EA open-sourced critical systems or provided documentation to preservation organizations.

Fourth, legal clarity would help. The Fort's Forge operates in legal ambiguity. If there were clear preservation rights written into gaming law, if companies had obligations to support preservation, if organizations had clear legal authority to preserve games, progress would be faster and more certain.

Fifth, communities are willing to preserve their own games if they care enough. The real lesson of The Fort's Forge is that players don't passively accept game deaths anymore. They're organizing, learning, and fighting back. Companies that expect to control narrative around their games after shutdown might find that expectation increasingly unrealistic.

Fifth, crowdsourcing matters. The packet logger tool turned individual players into citizen archivists. By distributing the preservation work, The Fort's Forge created redundancy and expanded the dataset available to developers. This might be a model for future preservation efforts.

Sixth, preservation infrastructure should be public goods. If games are going to die, there should be formal institutions (government agencies, libraries, non-profits) tasked with preserving them. Right now, it falls to volunteers. That's not sustainable long-term.

What Players Can Do: How You Can Support Game Preservation

If you care about preserving games and keeping Anthem alive, there are things you can actually do.

First, if you played Anthem, locate any packet logs you might have created and preserve them somewhere safe. These are irreplaceable primary source material. Back them up, share them with preservation communities, make sure they're not lost.

Second, support The Fort's Forge and other preservation efforts. Follow their Discord. Report bugs. Contribute code if you have the skills. Even documentation and organizational work helps.

Third, advocate for preservation rights in gaming. Support organizations fighting for the right to preserve and modify software you own. Vote for politicians who support digital preservation and against companies that actively fight it.

Fourth, buy and play games from companies that support preservation. If a game publisher makes it easy to preserve their games after shutdown, reward that with your money. Let the market know that preservation matters.

Fifth, speak up publicly. Tell people why you care about game preservation. Make it clear that this isn't niche hobby stuff—it's about culture, history, and ownership rights.

Sixth, learn some basic reverse-engineering skills. This isn't secret knowledge. Universities teach this. Game modding communities develop these skills informally. The more people who understand how to analyze and modify games, the stronger preservation efforts become.

Seventh, if you're in the game industry, design games to be preservable. Use open formats when possible. Plan for what happens when your servers go offline. Think about the long-term legacy of your work, not just the short-term profit.

FAQ

What happened to Anthem's servers?

EA shut down Anthem's official servers on January 12, 2025, making the game completely unplayable online. The company decided maintaining servers for a financially underperforming game wasn't worth the infrastructure costs. When the shutdown was announced in July 2024, the community began preservation efforts knowing the game would disappear entirely.

Why can't players just play Anthem offline if they own it?

Anthem was designed with server-dependent architecture. The game can't load levels, spawn enemies, track progression, or function in any meaningful way without connecting to EA's Blaze authentication server and BioWare's online services. The client relies on remote servers to provide critical gameplay data, making the game completely non-functional locally without reverse-engineering and emulation.

What is the Frostbite engine and why does it make revival harder?

Frostbite is EA's proprietary game engine used across multiple franchises. It's designed with an unusual architecture where gameplay runs in "server contexts" that can be local or remote. Anthem heavily relies on this remote server-side logic, meaning The Fort's Forge must not just emulate server responses but understand and recreate complex game simulation that was never meant to run without EA's infrastructure.

What did the proof-of-concept video actually show?

The Fort's Forge released a video showing Anthem loading with functional Blaze authentication and BioWare Online Services emulation. Players could log in, see their characters with correct cosmetics and inventory data, and navigate Fort Tarsis. However, it was proof-of-concept only. The video didn't show anyone loading into a mission or actually playing the game with NPCs spawning and enemies to fight.

What's the packet logger tool and why does it matter?

Ness 199X created a tool that lets players capture network traffic between their Anthem client and EA's servers. This crowdsourced approach creates a detailed archive of how Anthem's systems actually communicated. These packet logs become primary source material for understanding Anthem's protocols and allow players to preserve their character data for potential recovery when a private server version becomes available.

Will Anthem ever be fully playable again?

Probably not in its original multiplayer form, but single-player campaign functionality is achievable. The Fort's Forge has concrete evidence that mission logic and level data exist in the client. They're working on enabling that local functionality, which could make Anthem playable offline as a single-player experience. Full cooperative multiplayer is technically possible but would require exponentially more effort and years of development.

Is what The Fort's Forge is doing legal?

That's legally ambiguous. They're not distributing Anthem or breaking any clear laws, but they're analyzing proprietary code and potentially circumventing access controls, which could theoretically violate the DMCA. However, EA hasn't taken action against them, either through deliberate choice or lack of concern. The legal status would likely only become clear if EA sued, which hasn't happened.

Why doesn't EA just open-source Anthem to help preservation?

Open-sourcing would require the company to admit the game's failure and relinquish control of proprietary assets. EA could face complications with licensing of third-party libraries and content. Additionally, company incentives don't align with preservation. EA benefits more from moving players toward newer titles than from cooperating on preserving older games. Without legal pressure or public backlash, companies have little motivation to support preservation.

What can I do to help preserve Anthem or other games?

You can join The Fort's Forge Discord to contribute skills, back up any packet logs you created, share information about the project, and advocate publicly for game preservation rights. More broadly, support organizations fighting for right-to-repair and right-to-preserve legislation, purchase games from companies that enable preservation, and advocate for emulation and modification rights in digital media.

Why should anyone care about preserving Anthem specifically?

Anthem represents a broader principle about digital culture and ownership. When companies treat games as temporary services rather than lasting cultural works, thousands of hours of player investment disappear. Preserving Anthem affirms that games matter, that player communities matter, and that corporations shouldn't have the unilateral right to erase cultural artifacts just because they're no longer profitable.

Key Takeaways

- EA's Anthem servers shut down January 12, 2025, but The Fort's Forge community project proved partial revival is possible with a proof-of-concept showing authentication and character data loading

- Anthem's architecture depends on three services: Blaze (authentication), BIGS (player data), and the Frostbite multiplayer engine, where server-side logic creates the biggest reverse-engineering barrier

- The Frostbite engine's unusual client-server architecture, designed for flexibility, actually makes preservation exponentially harder because gameplay logic is distributed unpredictably between client and server

- Crowdsourced packet logging from September 2024 created primary-source documentation of how Anthem's systems actually communicate, becoming essential preservation data and enabling character recovery

- Mysterious inconsistencies like selective NPC spawning on identical-looking maps reveal deep system dependencies that The Fort's Forge still doesn't fully understand after reverse-engineering the game

Related Articles

- Nintendo Switch 2 Game-Key Cards Debate: Why Sega's Choice Matters [2025]

- GameCube Games Leaked for Nintendo Switch Online [2025]

- Virtual Boy Games on Nintendo Switch Online: Complete Guide [2025]

- The Hidden World of Single-Copy Game Sales: What Circana's Data Reveals [2025]

- Nintendo Switch 2's GameCube Library: Why It's Missing the Console's Best Games [2025]

- Spotify's Secret Court Order Against Anna's Archive [2025]

![Reviving Anthem After Server Shutdown: Why EA's Frostbite Engine Makes It So Hard [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/reviving-anthem-after-server-shutdown-why-ea-s-frostbite-eng/image-1-1769627232679.jpg)