Introduction: The Strange, Wonderful World of One-Copy Sales

Every month, something magical happens in the video game industry. Buried deep within spreadsheets and retail databases, games sell. Not hundreds of thousands. Not thousands. Just one. A single physical copy shows up at a register somewhere in America, gets scanned, and becomes part of video game history.

Mat Piscatella, a senior analyst at Circana, started noticing this phenomenon and decided to share it with the internet. His monthly threads on Bluesky have become unexpectedly viral—not because they're groundbreaking industry news, but because they're genuinely delightful. The Xbox 360 version of Burnout Paradise. Hasbro Family Game Night 3 for PS3. Games so obscure that most people didn't even know they existed are suddenly getting their moment in the sun, purchased decades after release by someone, somewhere.

But here's what makes this fascinating: it's not random. It's not a glitch in the data. These aren't imaginary sales or database errors. They're real transactions from real retailers, and they reveal something profound about how the video game market actually works—something that industry reports and AAA game launches completely miss.

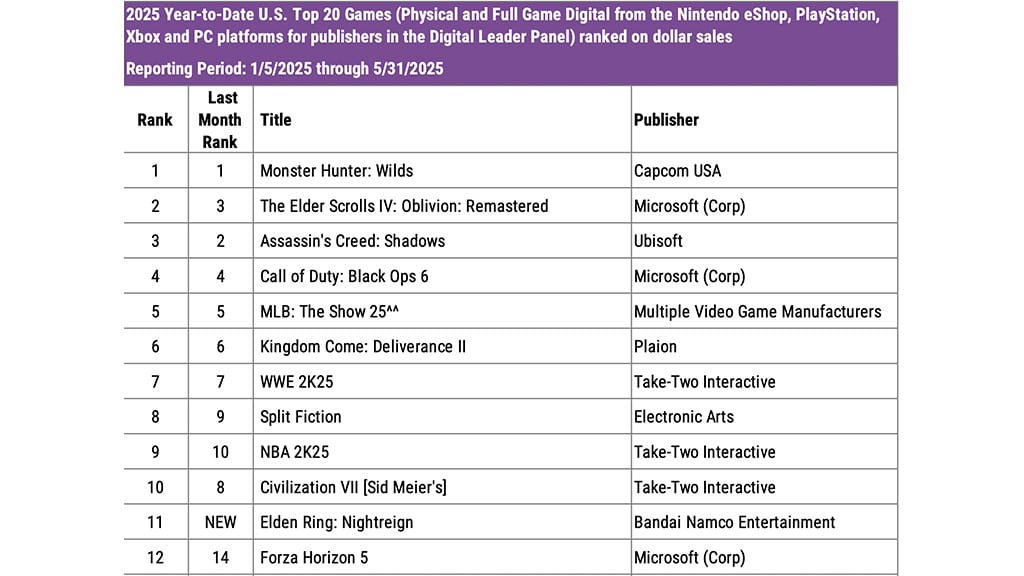

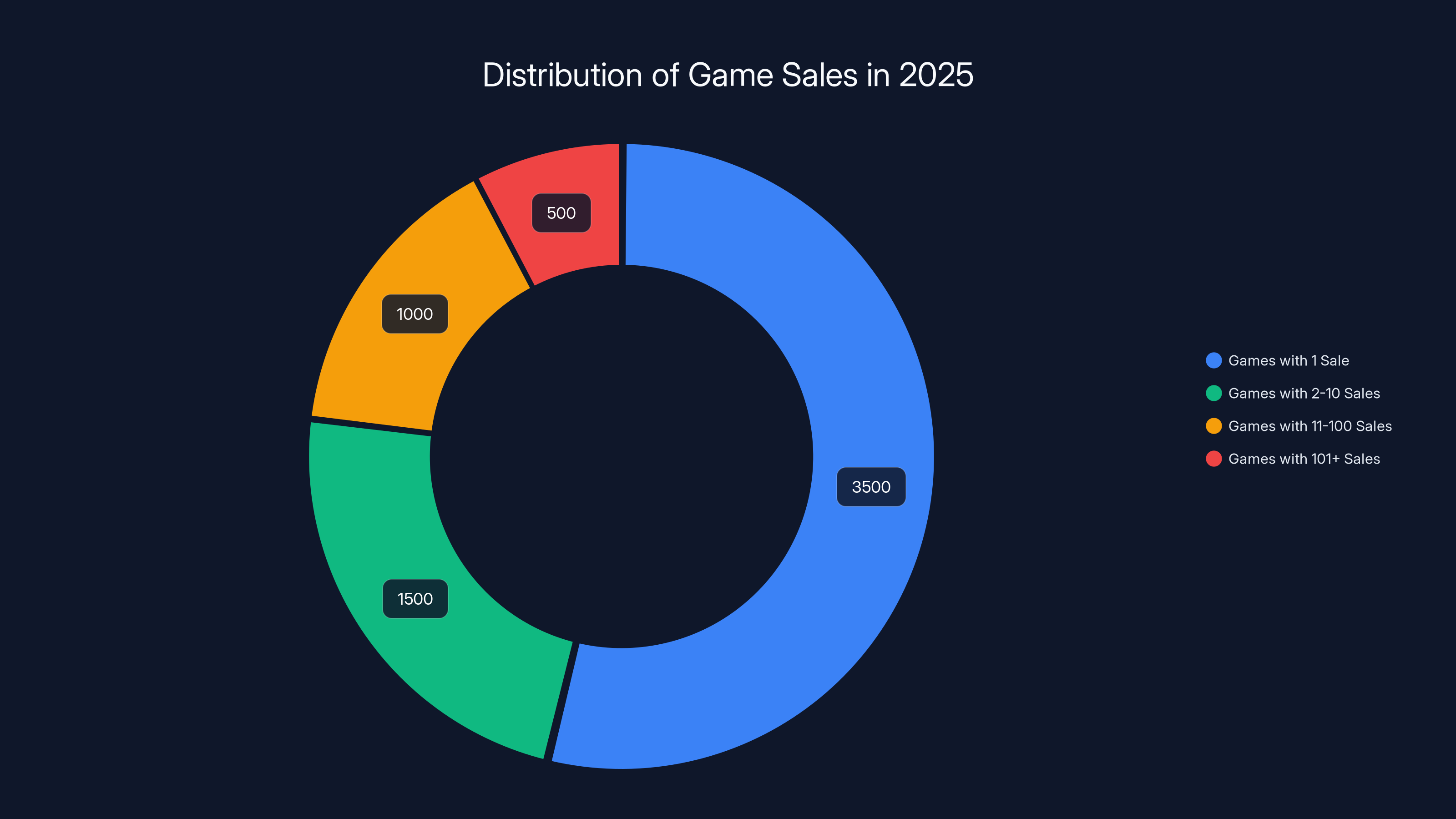

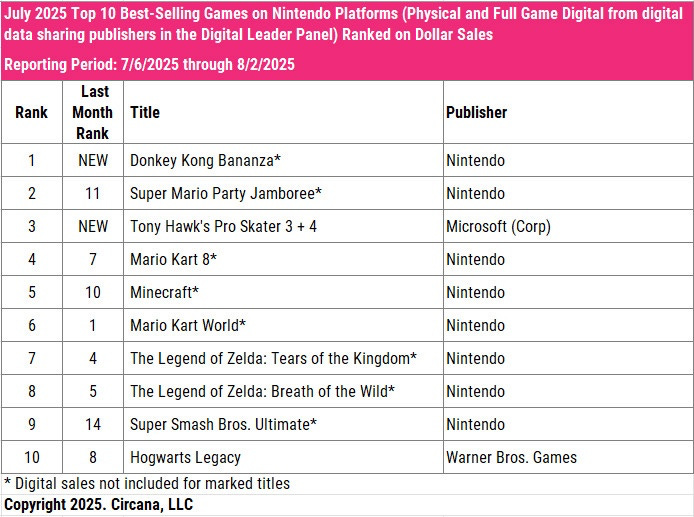

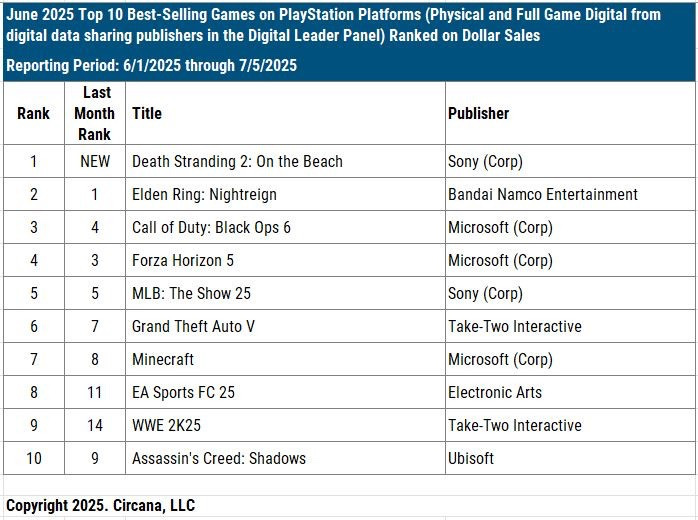

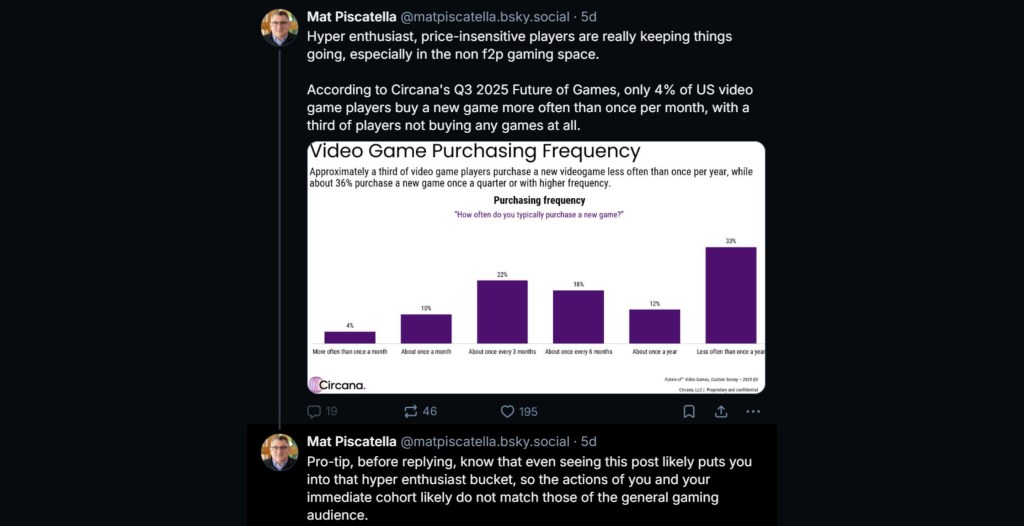

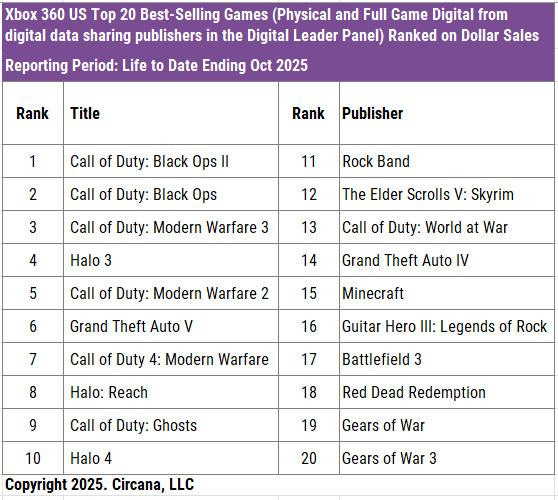

The conventional gaming narrative focuses on the blockbusters. Play Station 5 shortages. Xbox Game Pass milestones. Call of Duty franchise sales. But the real story? The story nobody talks about? It's in the tail. It's in the thousands of games selling between one and five copies per year across all platforms. It's in the reality that over 3,500 different games sold at least one physical unit at retail in 2025 alone, as highlighted by Circana's reports.

This article dives deep into the mechanics of how game sales data actually works, why single-copy sales matter more than you'd think, what they reveal about retail ecosystems, and what this bizarre, wonderful corner of the gaming industry tells us about consumer behavior, digital transformation, and the future of game distribution. We'll explore the infrastructure behind tracking these sales, examine real examples of games that sold just one copy, and understand why a boring analyst posting treasure-hunting lists has somehow tapped into something people genuinely care about.

TL; DR

- Circana tracks game sales through agreements with all major retailers, capturing point-of-sale data for physical game sales across North America

- Over 3,500 games sold at retail in 2025, with more than 1,000 games selling between one and five physical copies annually

- Single-copy sales are real transactions, not database errors—dusty inventory, lost stock, or rare collector purchases that eventually find their way to a register

- The data reveals hidden patterns about retail inventory management, consumer behavior, and how long-tail games survive in the market

- Mat Piscatella's monthly threads turned obscure sales data into viral content by framing it as a treasure hunt, connecting gamers to forgotten titles and memories

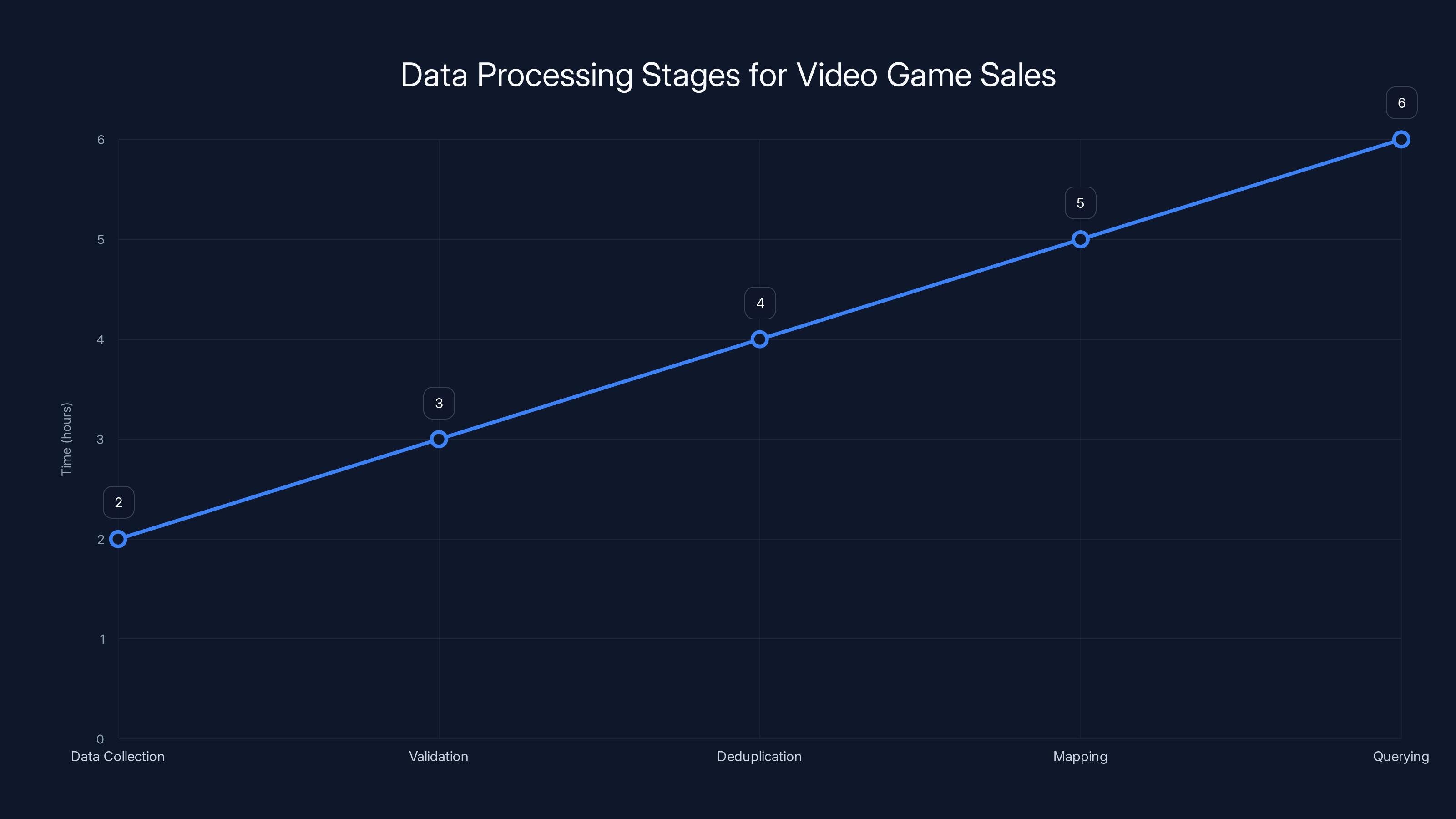

Estimated data shows that querying and mapping stages take the longest time in Circana's data processing pipeline for analyzing one-copy sales.

What Is Circana and How Does It Track Video Game Sales?

Circana isn't a household name, but it should be. The company is essentially the NSA of consumer retail data—it aggregates point-of-sale information from virtually every major retailer in North America and synthesizes it into actionable intelligence about what people are buying, when they're buying it, and how much they're paying.

Founded through the merger of IDC's consumer market research division and other data firms, Circana has deep relationships with every major retailer you can think of. Best Buy, Walmart, Target, Game Stop, and countless others feed their sales data directly into Circana's systems. For video games specifically, the company has built a sophisticated tracking infrastructure that captures physical game sales across console, handheld, and PC platforms.

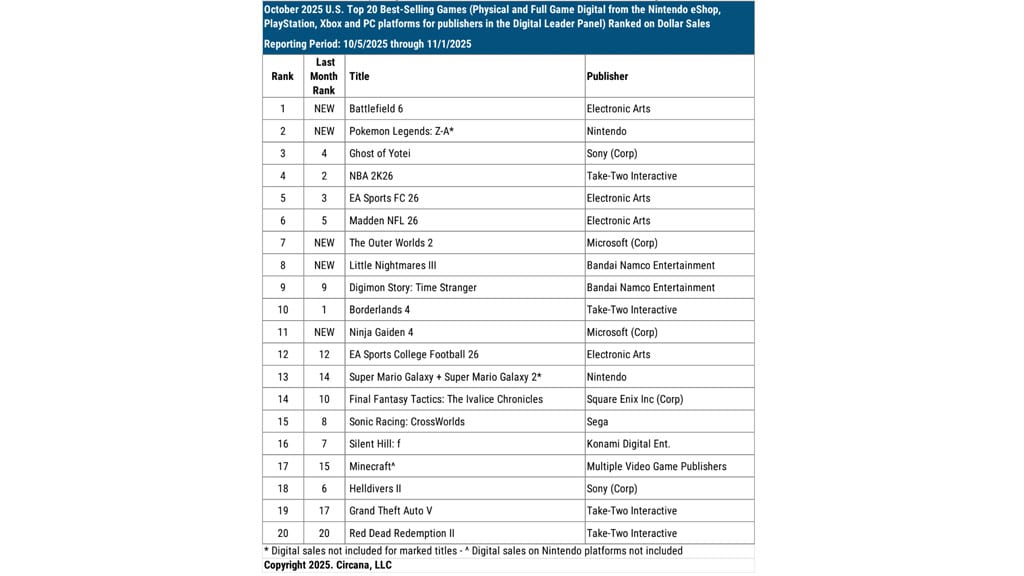

Mat Piscatella has been tracking video game sales data for over a decade. He's the go-to analyst when major outlets need comment on industry trends, and his monthly reports are treated as gospel by industry insiders. When he talks about Battlefield 6's launch being huge in October or November being historically bad for hardware, people listen because the data is comprehensive and verified.

The mechanics of how this tracking works are straightforward but require massive infrastructure. When a game sells at a retail register, that sale gets scanned and recorded. If that retailer shares point-of-sale data with Circana (which the major ones do), that transaction immediately enters Circana's database. The company then aggregates this data, removes outliers, validates it against multiple sources, and produces market analysis.

The brilliance of this system is that it captures something that digital sales platforms often obscure: actual consumer purchase behavior at the moment of transaction. There's no algorithm suggesting what people might want to buy. There's no recommendation engine. Just real people, in real stores, deciding to purchase a specific game at a specific time.

For Piscatella, having access to this granular data meant he could see not just which games were selling millions of copies, but also which games were selling one, two, or five copies. Most analysts would ignore those data points—they're noise, statistically insignificant. But Piscatella recognized something more interesting: they were data points that told a story about how retail actually works.

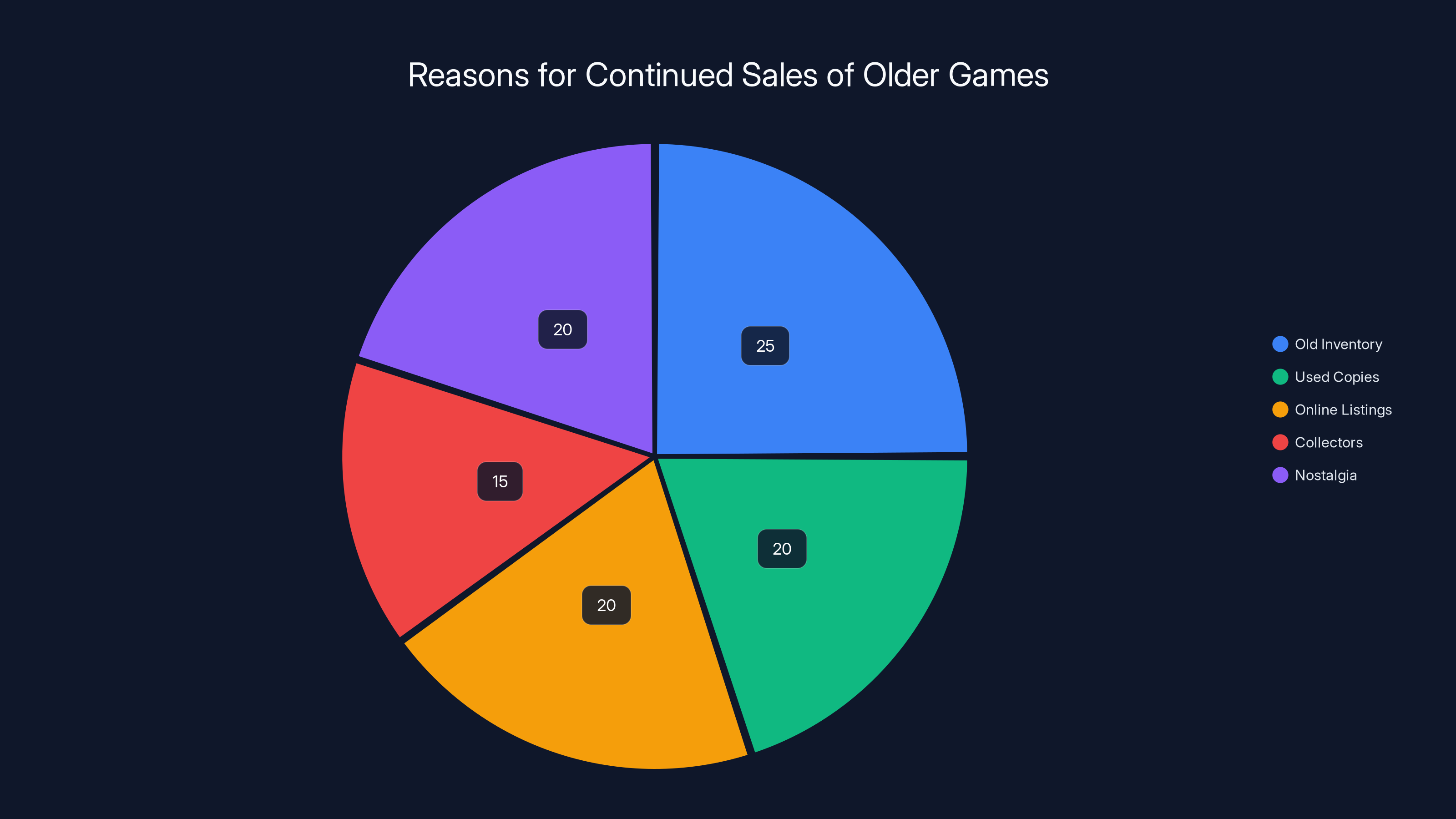

Older games continue to sell due to a mix of old inventory, used copies, online listings, collectors, and nostalgia. Estimated data.

How the Single-Copy Sales Lists Started: A Bluesky Conversation

The origin story of Piscatella's viral one-copy game lists is refreshingly simple: someone asked him a question.

On Bluesky, a social media platform that's become increasingly popular with tech workers, journalists, and gaming industry professionals, a user asked Piscatella whether he had data on games that sold exactly one physical copy in a given month. It's the kind of quirky question that most people would dismiss, but Piscatella saw the potential. He had the data. Why not share it?

What happened next was unexpected. The response was overwhelming. People weren't just interested in the data—they were fascinated by it. The combination of nostalgia (seeing old games they'd forgotten about), discovery (learning about games they'd never heard of), and the weird treasure-hunt aspect of it all created something genuinely engaging.

When the October 2024 list dropped, it included games that read like an archaeological dig through retail history. Burnout Paradise on Xbox 360—a game that's over 15 years old. Hasbro Family Game Night 3 for PS3—a licensed board game adaptation that most people forgot existed within weeks of purchase. These weren't games at the pinnacle of quality or cultural impact. They were games that somehow survived in the market, hidden in store stockrooms, found by someone, and finally purchased.

People started asking him to do it regularly. "So long as it stays fun, I reckon," Piscatella told The Verge when asked about continuing the monthly lists. He got it. The appeal wasn't the data itself—it was the story the data was telling. Each one-copy sale was a mystery. Why was a Hasbro Family Game Night 3 sitting on a shelf somewhere? How did someone end up buying it in 2024? Was it a collector? A parent who didn't check reviews? A clearance bin purchase at 11 PM?

The genius of the format is that it democratizes data. Usually, when people see analyst reports, they're dense, academic, and focused on business intelligence. Piscatella's threads are the opposite. They're playful. They're human. They acknowledge the absurdity: "I feel sorry for the poor soul who purchased Metroid: Other M for the Wii last year." That's not the language of professional analysis. That's the language of someone who gets it—who understands that video game purchases are often irrational, nostalgic, and deeply personal.

The Scale of the Long Tail: 1,000+ Games Selling Single Digits Annually

Now here's where the data gets genuinely interesting, because it's not just a few games selling one copy. It's thousands.

According to Piscatella, during 2025, more than 1,000 games sold between one and five new physical units in the US across all platforms. Think about that number. Not 100. Not 500. Over 1,000 different games. Each one represented by a handful of transactions. Each one still moving through retail systems decades after release.

But that's just the tip of the iceberg. The full picture is even more dramatic: over 3,500 different games sold at least one new physical unit at retail last year. That's 3,500 SKUs generating actual revenue, however minimal, from a retail system that most people assume is dominated by five to ten AAA titles.

The scale of this reveals something fundamental about how retail inventory actually works. Most people imagine retail as a well-oiled machine where products are precisely inventoried and old stock is cleared out. The reality is messier. Retailers have warehouses. They have display cabinets. They have back rooms. They have items that get buried, lost, or forgotten. When a new manager takes over a Game Stop, they might find a stack of PS3 games that nobody's seen in years. When a store renovates, they might uncover old inventory in a corner. That inventory doesn't disappear. Eventually, someone buys it.

Circana's ability to track these sales is crucial because it reveals a market dynamic that most analysis ignores. The gaming industry loves to talk about the "Big Three" consoles and the top 10 games. But the real retail ecosystem is far more complex. There are games from 2008 still selling in 2025. There are regional releases that never charted on any major list. There are licensed games from cartoon properties that disappeared in a year. All of them are still in the system. All of them are still being purchased.

This has real implications for retailers. A game that sells one copy per month might seem worthless, but it still takes up shelf space, requires SKU management, and generates data entry work. From a pure business perspective, it's a liability. But retailers can't just delete these SKUs from their systems. Customers still occasionally ask for them. Systems still track them. And because of the way retail inventory works, some of that old stock will eventually move.

The economics of the long tail are worth understanding because they affect how games are distributed and archived. When a physical copy sells at retail—even just one—it's evidence that someone valued that product enough to exchange money for it. That's not nothing. That's real market signal, even if the volume is trivial.

In 2025, over 3,500 games sold at least one physical unit, highlighting the enduring legacy and diversity of video game culture. Estimated data shows a significant portion of games sold only one copy, emphasizing the beauty of the gaming long tail.

Why These Sales Matter: The Treasure Hunt Effect

On the surface, single-copy sales seem worthless. From a business perspective, they're noise in the data. Publishers don't care if one copy of a 2010 game sells in 2025. They've already moved on to new projects. Retailers don't care because they've already written off the inventory cost. Consumers rarely know or care about these fringe sales.

But Piscatella recognized something smarter: people care about the story.

When you see that Burnout Paradise for Xbox 360 sold one copy in October 2024, your brain does something interesting. It starts storytelling. Who bought it? Why did they buy it? Was it a childhood favorite they wanted to revisit? Was it a collector hunting for a specific variant? Was it someone who walked into a Game Stop, saw it on a clearance shelf, and had a moment of nostalgia?

That storytelling is the treasure hunt. The data itself is just numbers. The treasure hunt is the human interpretation. And it turns out, people find that compelling.

This reveals something important about how we consume information. We don't actually want pure data. We want data with narrative. We want to understand the "why" behind the numbers. A list showing that some game sold one copy would be boring. But a list that says "someone, somewhere, bought Metroid: Other M for the Wii in 2024, and I feel sorry for them"—that's engaging. That's human. That's the kind of data that makes you want to share it with friends.

From a platform perspective, Piscatella's threads are perfect content. They're consistent (monthly), they're unique (nobody else has this data), they're shareable (people love showing them to friends), and they drive engagement (replies are full of people sharing their own gaming memories). The algorithm loves this stuff, which is why his Bluesky account exploded in followers.

But there's a deeper insight here too. These one-copy sales are evidence of market resilience. They show that the gaming retail ecosystem is still vibrant enough to move products from years past. They show that consumers are still buying physical games, even old ones, even obscure ones. In an era where everyone predicted physical game retail would be dead by 2020, these sales are a quiet rebellion against that prediction.

The Reality Behind One-Copy Sales: Hidden Inventory and Lost Stock

When Piscatella says a game sold one physical copy, he's not being poetic. It's literally one unit, scanned through a register, captured in point-of-sale data. But how does a game end up being sold in the first place? How does inventory from 2008 end up on a shelf in 2024?

The answer is that retail is messy.

Retailers like Best Buy, Walmart, and Game Stop operate on a supply chain that's designed for efficiency, but efficiency doesn't account for every variable. Games get shipped to stores, displayed, sold. When they don't sell, they get moved to clearance sections. But not all inventory gets cleared. Some of it gets lost. Some of it gets buried under newer products. Some of it sits in a back room, forgotten, until someone reorganizes and rediscovers it.

Mat Piscatella's theory: "Perhaps it was a unit that had been lost somewhere in the back, or was buried under a display, or who knows." That's the official story, and it's probably accurate for a significant portion of these sales. A store manager cleaning out a stockroom finds a box of PS3 games from 2012. One of them is Hasbro Family Game Night 3. It's in decent shape. It goes back on the shelf. Someone buys it. Data recorded.

Another possibility: online inventory. Retailers maintain massive online catalogs that include products they don't physically stock in stores but can ship to customers. Walmart or Target might list a game from 2010 in their online system, not because they actively stock it, but because it's still in their catalog. A customer finds it through a search, orders it, and suddenly—one-copy sale captured. This is particularly common with games that were released but never heavily promoted or with licensed games from shows or movies.

There's also the collector and completist angle. Serious gamers who are trying to build complete physical libraries sometimes spend hours searching retailer databases for obscure games still available for purchase. They might find a game that was released in 2008, see that one copy is in stock at a store 200 miles away, and order it online for shipment. That's a conscious purchase decision, not random retail discovery.

And then there are the genuinely weird purchases. Someone walking into Game Stop, spotting a game they remember from childhood, and buying it on impulse despite reviews being terrible. Someone buying a game as a gag gift. Someone who doesn't check what they're buying and accidentally purchases a children's board game adaptation instead of the actual board game.

The point is: these sales are real. They're not database errors. They're actual humans, making actual purchasing decisions, in actual retail locations. The fact that they're rare doesn't make them less real.

In 2025, over 1,000 games sold between 1-5 units, highlighting the long tail effect in retail game sales. Estimated data.

Historical Context: How We Got Here

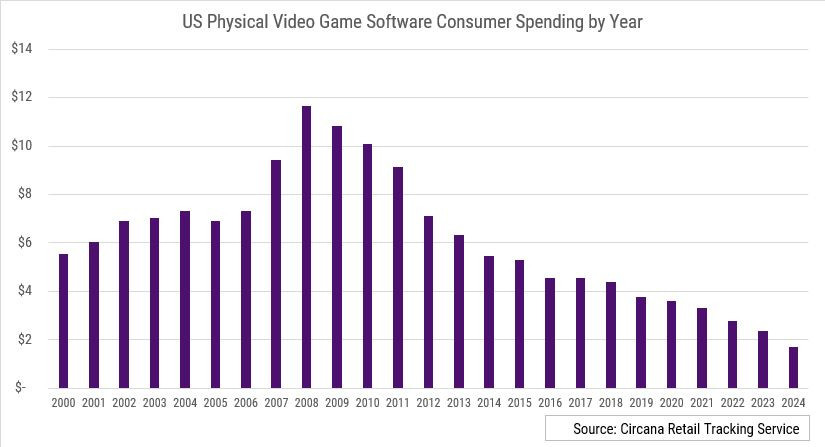

Understanding one-copy game sales requires understanding how we got to a point where a 15-year-old game can still be purchased at retail.

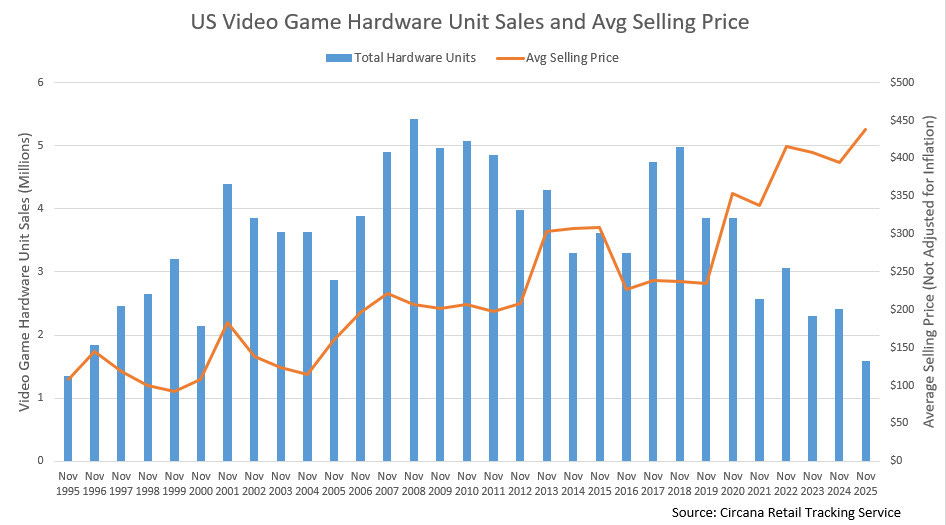

The video game retail ecosystem developed in the 1980s and 1990s as a supplement to traditional retail. Game stores emerged—specialized retailers like Babbage's, Electronics Boutique, and eventually Game Stop, which consolidated the market. These stores stocked games across all platforms and served as the primary distribution channel for game purchases.

For decades, this was the dominant model. You wanted a game, you went to a game store or Best Buy. The model worked well for new releases and bestsellers. Publishers manufactured physical copies, retailers stocked them on day one, consumers bought them, and inventory rotated quickly.

But there was a structural inefficiency built into this system: once a game stopped selling, retailers couldn't immediately remove it from their systems. They had to clearance it, mark it down, and eventually it might get donated or destroyed. But in that interim period, sometimes for years, the game still technically existed in the retail ecosystem.

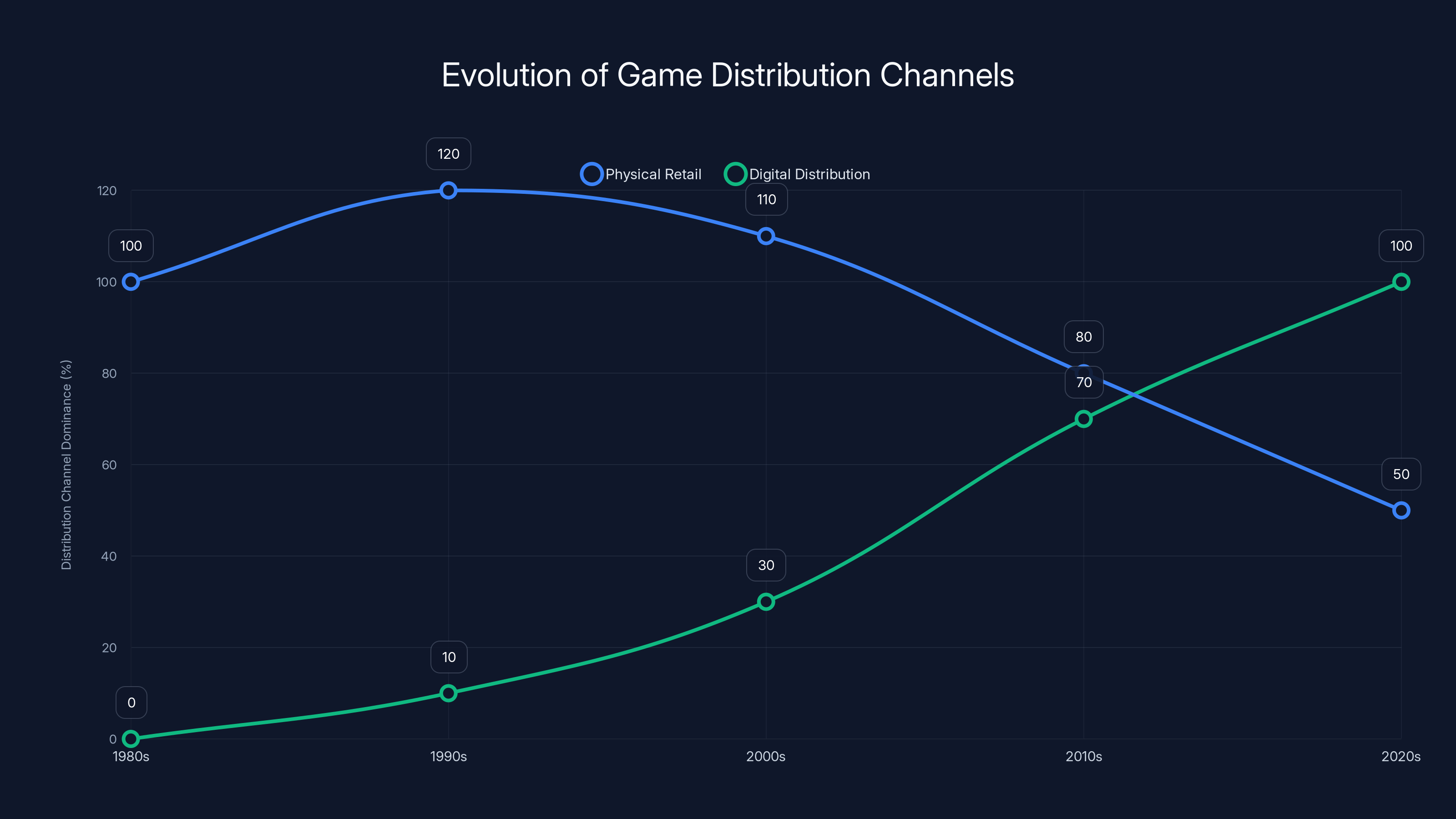

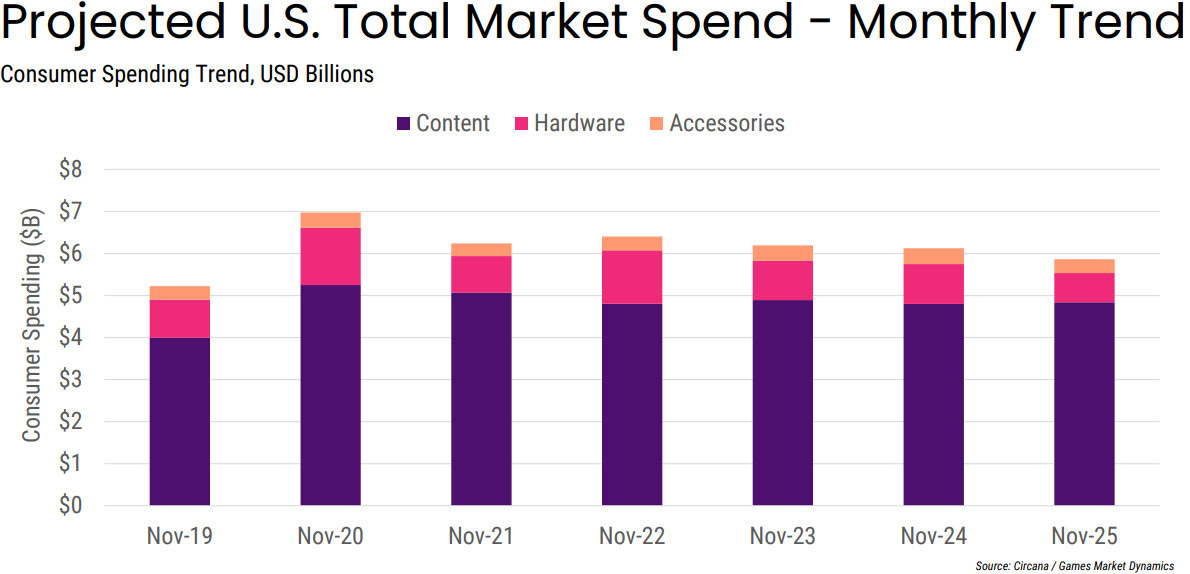

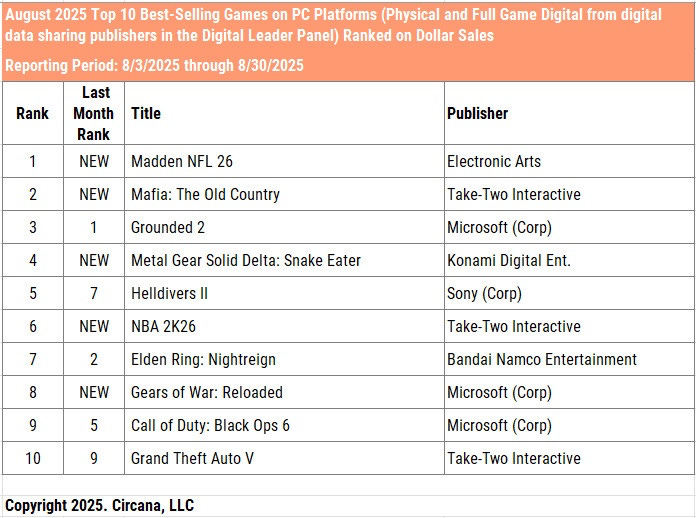

The digital transition accelerated starting around 2010. Steam grew on PC. Console digital stores launched. Epic Games and GOG emerged. The economics of digital distribution meant that publishers could sell games indefinitely without managing physical inventory. A game from 2008 could be for sale digitally in 2025 with zero additional costs.

But physical retail didn't disappear. It contracted. Game Stop, once a seemingly unstoppable force with thousands of stores, began a slow decline. Best Buy reduced game section sizes. Walmart consolidated gaming departments. But the infrastructure remained.

And here's the key insight: when retail infrastructure contracts, the long tail becomes more visible. When Game Stop had 6,500 stores, the cumulative effect of thousands of one-copy sales was spread across so many locations that it was invisible. But as stores closed, that same long tail concentrated. The games that were selling one copy per month across five locations were now selling one copy per month across two locations. It became noticeable.

Circana's data capturing all of this represents a shift in how we understand gaming retail. For the first time, we have complete visibility into the long tail. We can see that 3,500 games sold in 2025, not just the top 10. We can see that some games are still viable sellers 15+ years after release. We can see the complete picture of consumer behavior instead of just the blockbuster side.

The Data Collection Infrastructure Behind the Scenes

Captioning one-copy sales requires sophisticated infrastructure that most people don't think about.

Circana maintains relationships with retailers through contractual agreements that mandate regular data transmission. When a game sells at Best Buy's register, that transaction gets logged into Best Buy's point-of-sale system. Best Buy then sends batch reports to Circana (usually daily or weekly) containing all relevant transaction data: product SKU, timestamp, price, discount applied, location, and transaction ID.

This data arrives at Circana's aggregation servers, where it gets validated and deduplicated. Circana needs to ensure it's not double-counting sales or missing locations. They cross-reference data with other retailers to ensure consistency. If multiple retailers report the same sale, it gets flagged. If data is missing from a retailer that usually reports, investigations begin.

For video games specifically, the data needs additional processing. SKUs (stock keeping units) need to be linked to actual game titles. A product code like "0012345678" needs to be mapped to "Burnout Paradise, Xbox 360." This requires maintaining a master catalog of every game ever released, with multiple identifiers (UPC, EAN, retailer-specific codes).

Once the data is cleaned and mapped, Circana's analysts like Piscatella can query it. He's asking questions like: "What games sold exactly one physical unit in October 2024 across all US retailers?" The database needs to search through hundreds of millions of transactions to find matches.

That's computationally non-trivial. For a single month's data to identify all one-copy sales, the system needs to:

- Filter transactions to games only (excludes hardware, accessories)

- Filter to US retailers only (their agreement covers North America but Piscatella focuses on US)

- Group by product SKU and sum quantities

- Filter to products where total quantity equals 1

- Map SKUs to human-readable game titles

- Sort for presentation

The data cleaning is where the real work happens. Retailers' point-of-sale systems can introduce errors. A game might be scanned incorrectly. A transaction might get split across multiple entries due to payment processing. A return might not be recorded as a return and instead shows as a negative sale. All of this needs to be accounted for.

Circana's methodology is proprietary, but based on industry standard practices, they likely use:

- Automated anomaly detection to flag suspicious patterns

- Manual review of anything unusual

- Cross-validation with multiple data sources

- Quarterly audits comparing their findings with publishers' own sales data

- Seasonal adjustment factors (accounting for returns, holiday purchases, etc.)

The accuracy of this data is crucial because it forms the basis of industry analysis and business decisions. Publishers use it to plan future releases. Retailers use it to decide what products to stock. Investors use it to evaluate gaming companies. If the data was inaccurate, the entire information ecosystem would fail.

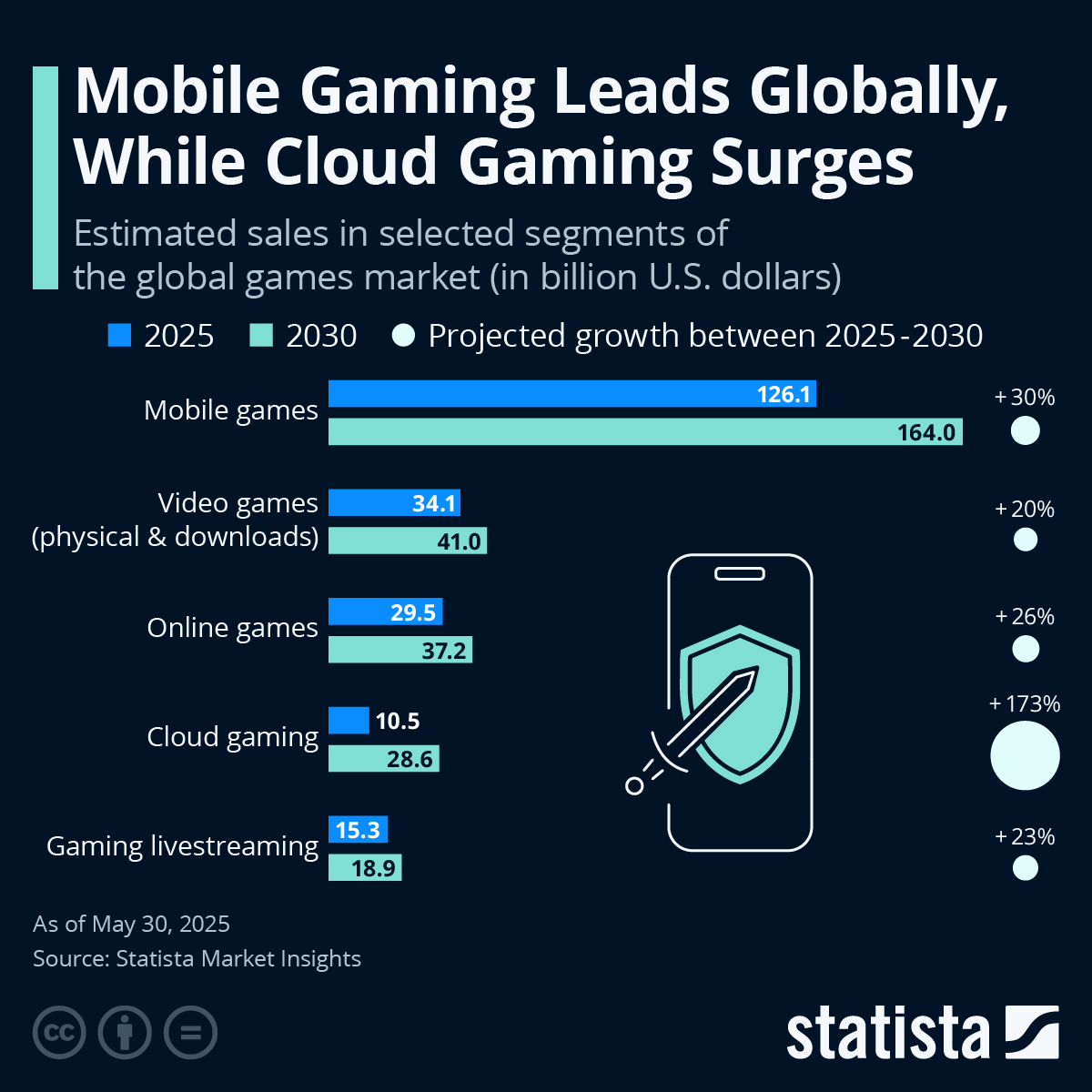

But here's the thing: even with all this infrastructure, Circana's data still has limitations. It only captures physical retail sales. Digital sales go unreported. Early access games, free-to-play games with purchase options, and subscription services aren't fully represented. Mobile games are barely tracked. The data is incredibly valuable, but it's still an incomplete picture of the gaming market.

The chart illustrates the shift from physical retail dominance in the 1980s and 1990s to digital distribution's rise in the 2010s and 2020s. Estimated data.

What Single-Copy Sales Reveal About Consumer Behavior

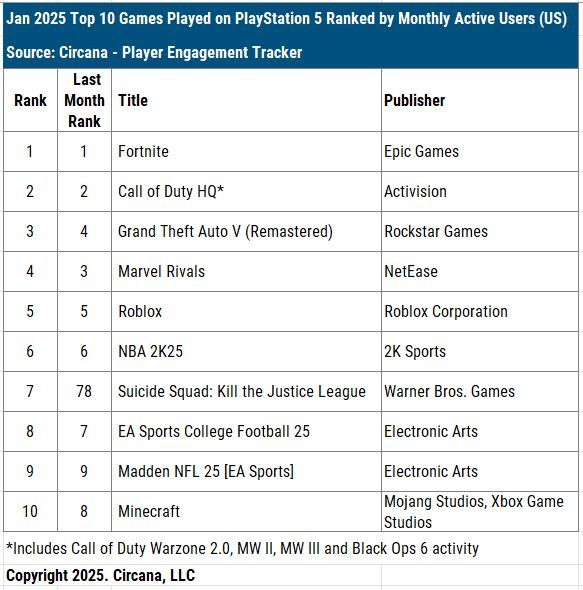

Beyond the fun factor, single-copy game sales reveal genuine consumer behavior patterns.

First, they prove that nostalgia is a real purchasing driver. People will buy games they remember from childhood even when better alternatives exist. Burnout Paradise selling one copy on Xbox 360 in 2024 is remarkable because multiple superior racing games are available, cheaper, and digitally distributed. Someone chose to buy that specific used or old-stock game. Why? Probably nostalgia.

Second, they reveal that physical game collecting is still a real activity. There's a subset of gamers—often called "completists"—who want to own the entire physical library of a franchise or console generation. They actively hunt for obscure SKUs. For these people, finding that one remaining copy of a rare game is a victory, and they'll pay for it.

Third, they show that casual consumers still exist who don't research before purchasing. Someone walked into a store and bought Hasbro Family Game Night 3 in 2024. That person either didn't check reviews, didn't care about reviews, or was buying it as a gift for someone else. These "impulse" purchases keep even terrible games in circulation.

Fourth, these sales demonstrate that retailers themselves still value completeness. Even though inventory turnover for a one-copy-per-month item is terrible, retailers maintain these SKUs in their systems because:

- It satisfies occasional customer requests ("Do you have this game?")

- It maintains the appearance of comprehensive selection

- Removing items from inventory systems is costly and manual

- Sometimes old stock is found and needs to be sold

Fifth, single-copy sales reflect the reality that product returns and destruction are imperfect. A game produced in 2008 that was destined for a retail shelf doesn't just disappear when it fails to sell. It gets moved around, stored, and sometimes ends up back on a shelf years later.

These behavior patterns matter because they inform how the industry thinks about distribution. Publishers can't assume that physical sales will stop immediately after a game's release window. They need to manage long-tail inventory. Retailers need to account for the fact that customer requests for old games will occasionally happen. Collectors need to know that opportunities to complete their libraries still exist in the retail system.

The Platform Effect: Why Bluesky Allowed This Content to Thrive

It's worth noting that Piscatella's one-copy game threads went viral on Bluesky specifically, not on more established platforms. This is significant.

Bluesky is a decentralized social network founded by Jack Dorsey that's been positioning itself as an alternative to X (formerly Twitter). It lacks the algorithmic recommendation engine that X uses, which means content spreads based on genuine user shares and engagement rather than algorithmic amplification.

For niche content like "games that sold one physical copy in October," this is actually ideal. The content won't get algorithmic suppression because the platform isn't trying to optimize for engagement metrics. It will spread if people find it genuinely interesting enough to share. And it turns out, people do find it interesting.

On X, this same content might get buried. The algorithm would flag it as "niche topic with limited appeal" and wouldn't promote it to the broader feed. On Tik Tok, it wouldn't work at all because the content doesn't fit the video-first format. On Linked In, it would be out of place in a professional context.

Bluesky's architecture—focused on threaded text and longer-form content, with a federated model that respects user choice—accidentally created the perfect platform for this type of analysis. Game industry professionals are already on the platform. They share the content with their networks. Networks engage with it. The thread gains visibility through pure human sharing.

This is worth understanding because it shows how platform design affects what kind of content thrives. Different platforms reward different content types. The fact that one-copy game sales became a viral phenomenon on Bluesky but would likely fail on other platforms reveals something about what each platform's community values.

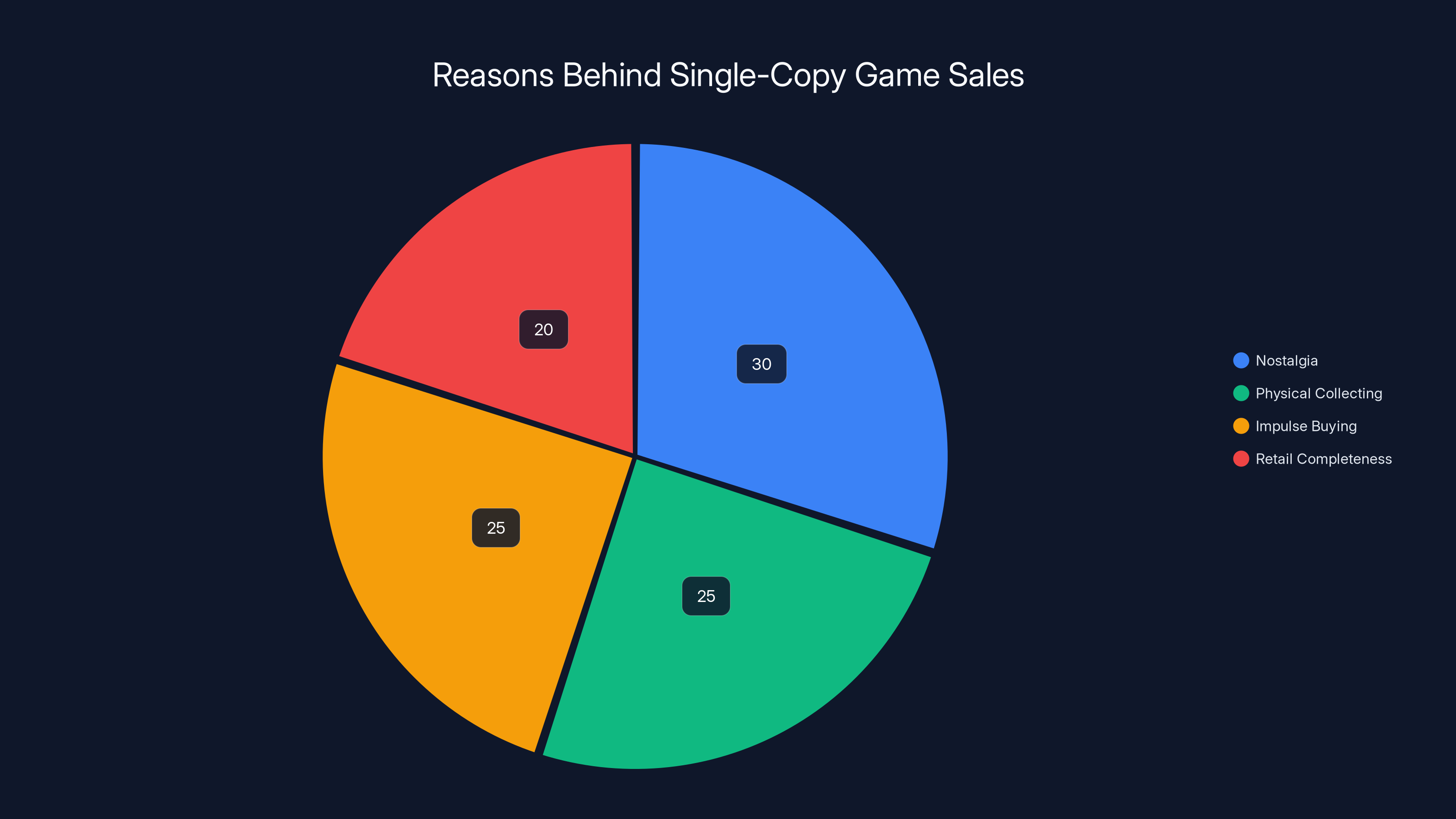

This pie chart estimates the distribution of reasons behind single-copy game sales, highlighting nostalgia and collecting as major factors. Estimated data.

The Economics of Long-Tail Retail

From a pure business perspective, selling one copy of a game annually is economically insignificant. The gross margin on a

But long-tail economics aren't about individual transactions. They're about aggregate effects.

When you have 1,000+ games selling between one and five copies annually, you have maybe 3,000-5,000 total physical units sold of games that most people assume are completely dead. That's 3,000-5,000 transactions processed, 3,000-5,000 customers satisfied, and maybe $50,000-100,000 in gross revenue across the entire long tail.

For a company like Game Stop, which is desperately trying to survive in a contracting market, even marginal revenue matters. Every transaction is cash flow. Every customer visit is an opportunity to sell something else (accessories, in-store credit, newer games). The long tail isn't profitable, but it's not supposed to be. It's supposed to keep the lights on.

For publishers, long-tail sales are usually handled through buydown agreements where the publisher either accepts a lower margin or the retailer absorbs the cost entirely. It's a way to clear inventory that nobody wants. But occasionally, a player in the system is surprised by a late sale.

The real insight is that the economics of physical retail have always included this tail. Publishers manufacture millions of copies. Some sit on shelves. Some get returned to warehouses. Some eventually get sold for pennies. The fact that Circana can now track this tail transparently is new, but the phenomenon itself is ancient.

The Impact on Game Preservation

Here's an angle that deserves more attention: single-copy sales are good for game preservation.

When a game is only available digitally, there's a single point of failure. If a digital store goes offline, if a licensing agreement expires and the game is delisted, if a publisher revokes access—poof, the game is gone. Digital preservation requires active curation and infrastructure, which is fragile.

When a game can still be purchased physically, even as a one-copy sale, it means there's still active demand. There's still someone who cares enough to hunt for it and buy it. There are still copies in the ecosystem that haven't been destroyed or lost. That's genuinely important for long-term preservation.

Consider this: Burnout Paradise sold one copy in October 2024. That means there's at least one person who values it enough to buy it in 2024. That person now owns a physical copy that can be preserved, played, modded, or preserved indefinitely. No licensing agreement can take that away. No digital store shutdown can remove it from existence.

This is particularly relevant for licensed games that are vulnerable to delisting. When a game's licensing agreement expires (for a sports franchise, a movie tie-in, or a music library), publishers often delist the game from digital stores. Players can no longer purchase it legally. But if that game is still selling physical copies—even just one per year—it remains in the ecosystem and accessible.

Citing game preservation scholars and archivists, there's been growing concern about "digital bit rot" and the vulnerability of digital-only media. The Internet Archive has been working on game preservation, but there are limitations to archiving digital games due to DRM (digital rights management) and licensing restrictions. Physical copies exist outside these restrictions.

So when Piscatella posts that Metroid: Other M sold one copy for the Wii, that's not just fun trivia. That's evidence that a physical copy of that game is still in circulation, still owned by someone, still playable. For a game that's no longer manufactured and only available through digital purchases on the Wii U e Shop, that's meaningful.

The Future of Physical Game Retail

Where is this heading? That's the question everyone wants answered.

On one hand, digital gaming is clearly dominant and growing. Newzoo and other gaming analytics firms report that digital revenue has exceeded physical retail revenue by a significant margin for years. Physical retail is shrinking. Game Stop is a zombie company kept alive by nostalgia and institutional inertia, not by strong business fundamentals.

On the other hand, physical game sales haven't disappeared. Despite predictions in 2015 that physical retail would be dead by 2020, it's still around. It's smaller, but it's resilient. And the existence of 3,500 games selling at least one physical unit in 2025 suggests there's still enough demand to keep the ecosystem functioning.

Mat Piscatella's monthly lists are actually a bellwether for this trend. If physical retail were truly dying, these lists wouldn't be interesting. They'd be listing games that barely sold any copies. But instead, the lists are dominated by real, recognizable games that sold one or two copies. That means the tail is healthy enough to create interesting data.

The likely future is continued consolidation with a long tail. Game Stop will probably continue shrinking. Walmart and Target will reduce gaming sections further. Best Buy will focus on consoles and accessories rather than games. But retailers will still exist. Online retailers will become more important. And the long tail will remain because there's always some inventory that hasn't sold.

For consumers, this means physical games will become increasingly special. A physical game won't be the default distribution method. It'll be a choice, often more expensive than digital, but offering permanence and ownership. Collectors will continue hunting for rare physical copies. Completists will hunt through retail databases for obscure SKUs. And once a year or so, someone will buy a 15-year-old game that's been sitting in a warehouse, and Mat Piscatella will post about it on Bluesky.

Real Examples: Games That Sold One Copy

Let's look at some specific examples from Piscatella's lists to understand what's actually selling.

Burnout Paradise, Xbox 360 (October 2024): This is fascinating because Burnout Paradise was a successful franchise entry, widely praised, and has been re-released multiple times. Why would someone buy a physical Xbox 360 copy in 2024 when the game is available digitally on newer systems? Possible answers: someone completing a physical Xbox 360 library, someone who lost their original copy and found a used copy, someone who prefers the original version over remakes. Whatever the reason, this represents a buyer who had specific preferences.

Hasbro Family Game Night 3, PS3 (October 2024): This is a licensed game from 2012 based on Hasbro board games. It was almost certainly a bargain-bin game. Someone bought it—maybe for a PS3 collector, maybe as a joke, maybe not understanding what they were buying. But it moved. That single sale means someone out there now owns this game, has paid for it, and is presumably playing it or has added it to their collection.

Metroid: Other M, Wii (mentioned in the article): This is particularly interesting because it's a controversial game. Metroid: Other M was criticized for its story and gameplay. Yet someone bought it for their Wii in 2024. That person didn't care about the negative reviews. They wanted to play a Metroid game on Wii, and this was the one available.

These examples illustrate that single-copy buyers are making deliberate choices. They're not random. They're not accidents. They're people who have specific preferences, and those preferences lead them to buy old, obscure games that most people have forgotten about.

The Data's Limitations: What Circana Data Doesn't Tell Us

Before we conclude, it's important to acknowledge that Circana's data, while comprehensive, has real limitations.

First, it doesn't track digital sales. Every game sold on Steam, on Play Station Network, on Game Pass, through Epic Games Store—none of that appears in Circana's reports. For a more complete picture of gaming sales, you'd need data from multiple sources. Valve doesn't publish Steam sales figures. Microsoft doesn't publish Game Pass detailed breakdowns. Sony and Nintendo don't fully disclose digital sales. So the real gaming market is much larger than Circana's data suggests.

Second, it doesn't track used sales or resales. Game Stop sells used games. Facebook Marketplace has people selling physical games. Local game shops trade in used games. None of that appears in "new retail" data. Someone could buy the same physical copy of Burnout Paradise five times (used) through various channels, but Circana would only count it once if it was purchased new at retail.

Third, it doesn't fully account for international sales. Circana focuses on North America primarily, with some data on Europe. Asia and other regions are underrepresented or not tracked. A game might be selling thousands of copies in Japan and virtually nothing in North America, but Circana's US-focused data wouldn't reflect that.

Fourth, mobile games are barely tracked. Sensor Tower and other mobile analytics firms track app store sales, but that's separate from Circana's physical retail data. Mobile represents a huge portion of gaming revenue but is invisible in these reports.

Fifth, there's a selection bias toward older, physical games. Games that have been in retail inventory for years are more likely to appear on these one-copy lists. New games that are primarily sold digitally will never appear. This creates a database that skews heavily toward legacy content.

Understanding these limitations is important because it prevents over-interpreting the data. Circana provides a clear view of physical retail sales in North America. That's valuable. But it's not the complete picture of gaming sales.

Lessons for the Gaming Industry

What should publishers, retailers, and developers take away from all of this?

For publishers: The existence of the long tail means physical games have value for longer than expected. A game released in 2010 might still be generating revenue in 2025 through physical sales. Don't rush to completely sunset older titles. There's still a market, however small.

For retailers: The long tail is important for store traffic and customer satisfaction even if individual transactions aren't profitable. When a customer walks in asking for a specific old game and you have it, they're buying other things too. The long tail supports the ecosystem.

For developers: Understanding that players hunt for old games creates opportunities for re-releases, collections, and preservation. The audience for your 10-year-old game hasn't gone away. They're harder to find, but they exist.

For gamers: Piscatella's lists are a reminder that physical games are finite. If you want to own a specific game forever, don't assume it'll be available digitally in 10 years. Physical copies are more permanent than digital licenses.

The Joy of Obscure Data

Ultimately, what Mat Piscatella discovered is that people love obscure data. Not for business reasons. Not for competitive advantage. Just for the joy of it.

Looking at a list of games that sold exactly one physical copy creates a specific emotional response. It's part nostalgia ("Oh, I remember that game!"), part discovery ("I didn't even know that existed"), part detective work ("I wonder who bought this"), and part connection ("This game is still alive in the world somewhere").

In a gaming industry increasingly focused on analytics, engagement metrics, and player monetization, there's something refreshing about data that's just genuinely fun. Piscatella wasn't trying to build a brand or create viral content. He was just sharing interesting data in a way that made it accessible and entertaining.

And it worked because he understood something fundamental: data becomes meaningful when it's connected to human stories. One-copy sales aren't interesting as business metrics. They're interesting because they're mysteries. They're interesting because each one represents a choice someone made to buy a specific game. They're interesting because they connect us to a past that we thought was gone but is actually still present, sitting on a shelf somewhere, waiting for someone to care enough to purchase it.

That's the real insight. Not about retail economics or data infrastructure. Just about the fact that the games we played, the memories we made, the joy we experienced—it's all still there, still accessible, still valuable. And occasionally, someone will find that old copy and buy it. And we get to know about it.

FAQ

What is Circana and what data does it track?

Circana is a market research firm that aggregates point-of-sale data from major retailers across North America, including all major gaming retailers and department stores. The company has contractual agreements with retailers to access their transaction data, allowing them to track physical game sales by product SKU, price, retailer, and timestamp. This makes Circana the primary source for North American physical video game sales data that the industry uses for analysis and reporting.

How does Circana identify games that sold only one physical copy?

Circana's systems track every transaction recorded in retailer point-of-sale systems. When a game is scanned at a register or purchased online through a retailer that shares data with Circana, it's recorded with the product SKU, quantity, and timestamp. By filtering their database to show all products where the total quantity sold in a given month equals exactly one unit, analysts like Mat Piscatella can generate lists of games with one-copy sales. The company then maps these SKU codes to human-readable game titles for presentation.

Why do games from 2008-2010 still sell at retail decades after release?

Games continue to sell at retail years after release due to several factors: retailers maintain old inventory in warehouses or back rooms that eventually gets discovered and put back on shelves, used copies get traded in and resold through retail channels, online catalogs keep products listed even if they're not physically stocked, collectors actively hunt for specific games to complete their libraries, and nostalgic consumers occasionally make impulse purchases of games they remember from childhood. Additionally, retailers can't simply delete products from their inventory systems, so old stock persists in the system until it either sells or is officially delisted.

What are the limitations of Circana's gaming sales data?

Circana's data only tracks physical retail sales in North America. It excludes digital sales through Steam, Play Station Network, Game Pass, Epic Games Store, and other digital storefronts. It doesn't include used game sales, international sales outside their tracked regions, mobile gaming revenue, or in-game purchases and DLC. This means Circana's picture of gaming sales, while comprehensive for physical retail, represents only a portion of total gaming revenue and misses large segments of the industry entirely.

Who is Mat Piscatella and why did he start posting about single-copy game sales?

Mat Piscatella is a senior analyst at Circana who specializes in video game industry analysis. He regularly posts detailed gaming sales trends and data to social media. The one-copy game sales lists originated from a Bluesky user asking him whether he had data on games that sold exactly one physical copy. Piscatella recognized the appeal—the combination of nostalgia, discovery, and treasure-hunting—and started regularly posting these lists. The threads went viral because they made technical data entertaining by framing it as a mystery.

How significant are one-copy sales to the overall gaming market?

Individually, one-copy sales are economically insignificant. A single copy of a clearance game generates minimal profit. However, collectively, they represent thousands of transactions annually. According to Piscatella, over 1,000 games sold between one and five physical copies in 2025, and more than 3,500 games sold at least one physical copy at US retail. While this tail doesn't drive major revenue, it demonstrates the breadth of games still available for purchase and reveals consumer behavior patterns that industry analysis often overlooks.

What does this data reveal about the future of physical game retail?

The continued existence of one-copy sales suggests physical game retail isn't dying immediately, but is consolidating and becoming niche. The fact that 3,500+ games still sold at retail in 2025 indicates demand exists beyond major blockbusters. However, the clear trend is toward digital distribution, with physical retail shrinking in store count and floor space. The long tail will likely persist because retailers can't easily eliminate it from their systems, but it will become less prominent. Physical games will increasingly become a collector's item rather than the default distribution method.

How does Bluesky's platform design enable this type of content to go viral?

Bluesky uses a decentralized architecture that differs from algorithmic social media platforms like X. Content spreads through genuine user shares rather than algorithmic recommendation, making niche topics more viable. Text-based, threaded content is the native format, ideal for sharing data lists. The platform's user base skews heavily toward tech industry professionals and gaming journalists who are naturally interested in gaming analytics. This combination of factors allowed Piscatella's posts to gain visibility through organic sharing among a engaged community.

Why does this data matter for game preservation?

Physical game copies represent a form of preservation independent from digital infrastructure and licensing agreements. When a game is only available digitally and licensing expires or digital stores shut down, the game becomes unavailable. Physical copies that still sell and exist in players' hands can be preserved indefinitely. Games with licensed content (sports franchises, movie tie-ins) are particularly vulnerable to digital delisting when licensing agreements expire. The fact that these games occasionally still sell physically means active copies remain in circulation beyond corporate control, ensuring long-term accessibility.

Conclusion: The Beauty of the Gaming Long Tail

Mat Piscatella stumbled onto something genuinely special when he started posting lists of games that sold a single physical copy. On the surface, it's boring data. Games with one sale annually have negligible business impact. They don't affect stock prices or publisher earnings reports. They're noise in the broader gaming market.

But Piscatella recognized that the most interesting data isn't always the most important data. Sometimes the most interesting data is the most human. It's the data that connects us to mysteries and stories. It's the data that proves the games we loved are still alive, still purchasable, still relevant to someone, somewhere.

The revelation that over 3,500 games sold at least one physical unit at retail in 2025 is a powerful statement about the breadth of gaming's legacy. It's proof that video game culture isn't just about the latest release or the most popular franchise. It's about all of it. Every game ever made, it seems, still has at least one person who cares enough to buy it.

For an industry obsessed with metrics and optimization, there's something beautifully inefficient about a game selling one copy. It's not scalable. It's not repeatable. It's not part of any business plan. It just is. Someone bought it. Circana tracked it. And we got to find out about it.

The long tail of gaming retail is thriving, not because it's profitable, but because it's persistent. It's resilient. It's proof that the choices we make as consumers, even one-copy-at-a-time, matter. They create a record. They create evidence. They keep products alive.

As physical retail continues to contract and digital distribution becomes increasingly dominant, these one-copy sales become more meaningful, not less. They're the last traces of a direct consumer-to-retailer relationship that defined gaming for decades. They're the proof that games from our past are still around, waiting for someone to discover them, value them, and buy them.

So the next time you see one of Piscatella's threads on Bluesky highlighting some obscure game that sold one copy, take a moment to appreciate what you're looking at. It's not just data. It's a treasure map. It's proof that somewhere in America, in a warehouse or on a shelf or in someone's online cart, there's a physical copy of a game that time forgot. And someone, against the odds, found it and wanted it badly enough to purchase it.

That's the real story here. Not about data infrastructure or retail economics. It's about the fact that games matter. They matter enough that even a single copy, sitting forgotten for years, can find its way to someone who cares. And in an industry that's increasingly focused on engagement metrics and player monetization, that's genuinely beautiful.

So keep an eye on those Bluesky threads. Hunt through retailer websites for the games on those lists. Find that old copy of Burnout Paradise or Hasbro Family Game Night 3. Prove that the long tail is still alive. Be part of the story. Become the one-copy sale.

Because you never know what you'll find in the data. And sometimes, the best gaming discoveries are the ones that shouldn't exist anymore, but somehow, miraculously, still do.

Key Takeaways

- Circana tracks physical game sales through point-of-sale data from all major retailers, capturing every transaction including single-copy sales

- Over 3,500 games sold at least one physical unit at US retail in 2025, with 1,000+ games selling between 1-5 copies annually

- Mat Piscatella's monthly Bluesky threads about one-copy sales went viral by framing data as a treasure hunt connecting nostalgia with discovery

- Single-copy sales reflect real consumer behavior: nostalgia purchases, collector hunting, impulse buys, and discovered old inventory from retail warehouses

- Physical game copies serve as important preservation medium independent from digital licensing agreements that can cause games to disappear from digital stores

Related Articles

- Devon Pritchard: Nintendo of America's New President [2025]

- Nintendo Switch 2's GameCube Library: Why It's Missing the Console's Best Games [2025]

- Ubisoft Cancels Prince of Persia Remake: What It Means for Gaming [2025]

- Ubisoft Cancels 6 Games Including Prince of Persia Remake [2025]

- Ubisoft Cancels Prince of Persia Remake: Inside the Major Gaming Restructure [2025]

- Bungie's Marathon Extraction Shooter Launches March 5th: Complete Guide [2025]

![The Hidden World of Single-Copy Game Sales: What Circana's Data Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-hidden-world-of-single-copy-game-sales-what-circana-s-da/image-1-1769271219741.jpg)