Spotify's Secret Court Order Against Anna's Archive: Inside the Domain Takedown Battle

In early January 2025, something quietly happened in the digital underground that would reshape the conversation around copyright enforcement, shadow libraries, and the limits of internet control. The Anna's Archive .org domain vanished. Gone. When the site's operators first noticed, they shrugged it off as routine. "Shadow libraries get suspended all the time," they said. "Probably not about the Spotify scrape."

They were wrong.

What actually happened was far more calculated and troubling than a random domain registry hiccup. Spotify, working alongside Sony, Warner, and Universal Music Group, had quietly filed a lawsuit in federal court. Not in public. Under seal. With no warning to the targets. A judge granted them a temporary restraining order the same day they asked for it. By the time Anna's Archive operators realized what was happening, their primary domain was already gone, and they were reading about it in court documents instead of from a lawyer.

This case illuminates something fundamental about how power operates on the internet in 2025. It's not always a public battle. Sometimes it's a sealed lawsuit, an ex parte hearing, and a fait accompli. Sometimes you don't get to defend yourself until after you've already lost.

Let me walk you through exactly what happened, why it matters, and what it reveals about the future of copyright enforcement online.

The Spotify Scraping: What Actually Happened

Anna's Archive isn't your typical pirate site. It doesn't host movies or stream songs. It's more philosophical than that. The project positions itself as a preservation effort, a digital library for public benefit, scraping metadata and content from everywhere to build an archive that can't be censored or taken down.

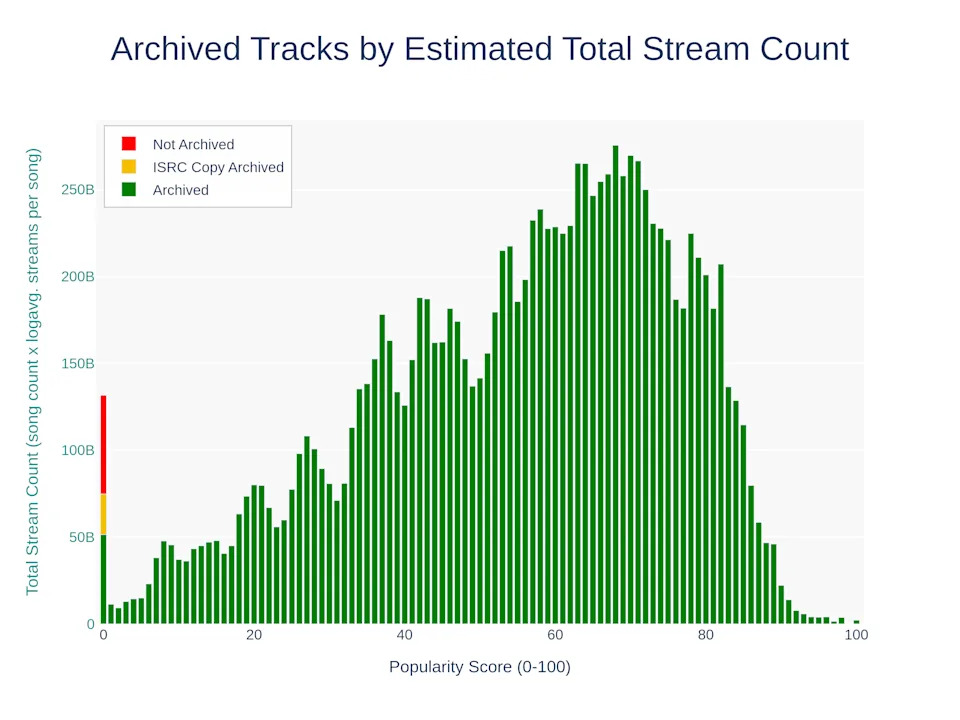

In late 2024, someone associated with Anna's Archive decided to download Spotify's entire catalog. Not just metadata. The actual audio files. Millions of songs. The scope was massive. Spotify has over 100 million tracks in its library. Grabbing all of them wasn't a casual afternoon project. It required coordination, bandwidth, and patience.

What made this different from typical music piracy wasn't the scale. It was the intent. The operators didn't immediately release the files. Instead, they sat on them. They announced the backup and suggested they'd release it eventually, but only if certain conditions were met. This wasn't pure piracy in the traditional sense. It was leverage wrapped in the language of digital preservation.

Spotify and the record labels watched this develop with obvious alarm. They weren't just worried about the current backup. The court filings make clear they feared what would happen next. Anna's Archive operators, they argued, would release the files publicly if given any warning. They'd move their infrastructure offshore. They'd activate "contingency plans" to stay ahead of enforcement. In other words, they'd do exactly what any competent adversary does when confronted by legal action.

So the music companies made a calculated decision: don't give them a chance.

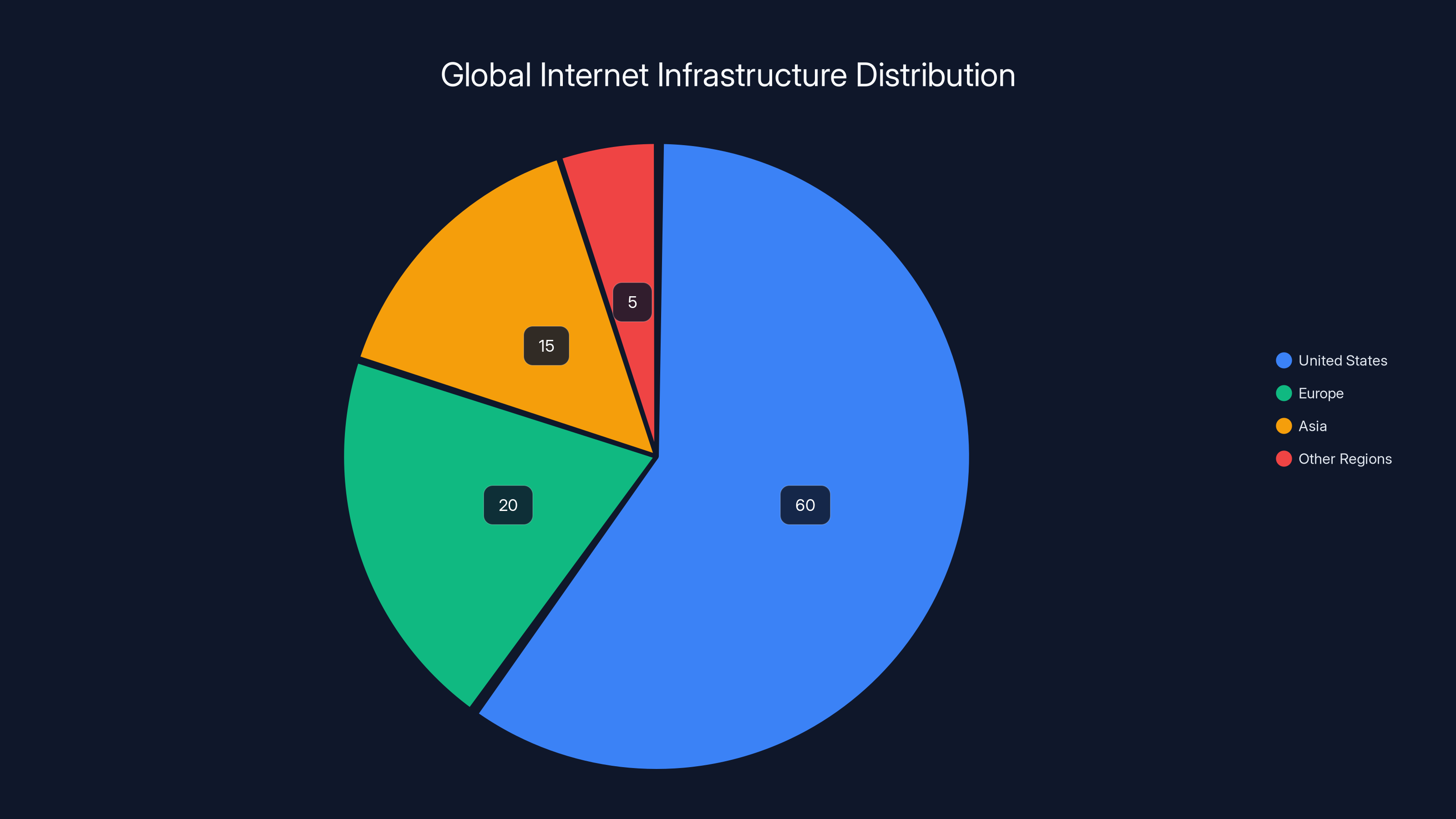

Estimated data shows that 60% of internet infrastructure is based in the United States, highlighting the significant leverage US court orders have over global internet operations.

The Sealed Lawsuit: Playing Defense Without Opposition

In late December 2024, Spotify and the three major record labels filed a lawsuit in US District Court for the Southern District of New York. The case was immediately sealed. No public docket. No notice to the defendants. Just a complaint sitting in a judge's chambers waiting for attention.

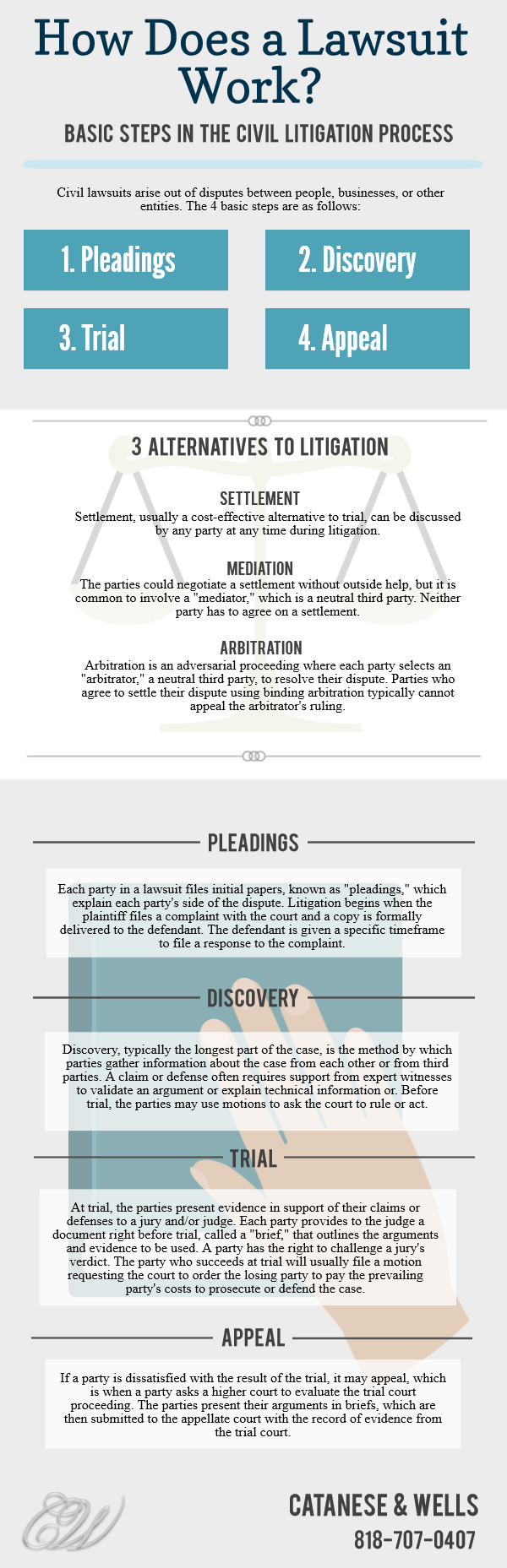

This matters because it's the opposite of how the legal system is supposed to work. In normal litigation, both sides get to present arguments. A judge hears from plaintiffs and defendants before making decisions. The court has every incentive to hear both perspectives because a one-sided decision is more likely to get reversed on appeal.

But this wasn't normal litigation. This was an ex parte temporary restraining order, which means "without the other party." These exist for genuine emergencies. If someone's committing a crime right now, you don't wait three weeks for a trial. You get an emergency order, execute it, and then give the other side their chance to be heard later.

The music companies argued their situation met that standard. If they gave Anna's Archive notice, the lawyers wrote, the operators would "almost certainly release the sound recordings that it has illegally copied from Spotify to the public immediately and activate contingency plans to relocate its infrastructure outside of the United States."

Was that prediction accurate? Maybe. The Anna's Archive operators clearly know how to stay ahead of enforcement. They run on multiple domains in multiple jurisdictions with anonymous payment methods and bogus registrations. They've built redundancy into their operation. Giving them a heads-up would almost certainly trigger some kind of response.

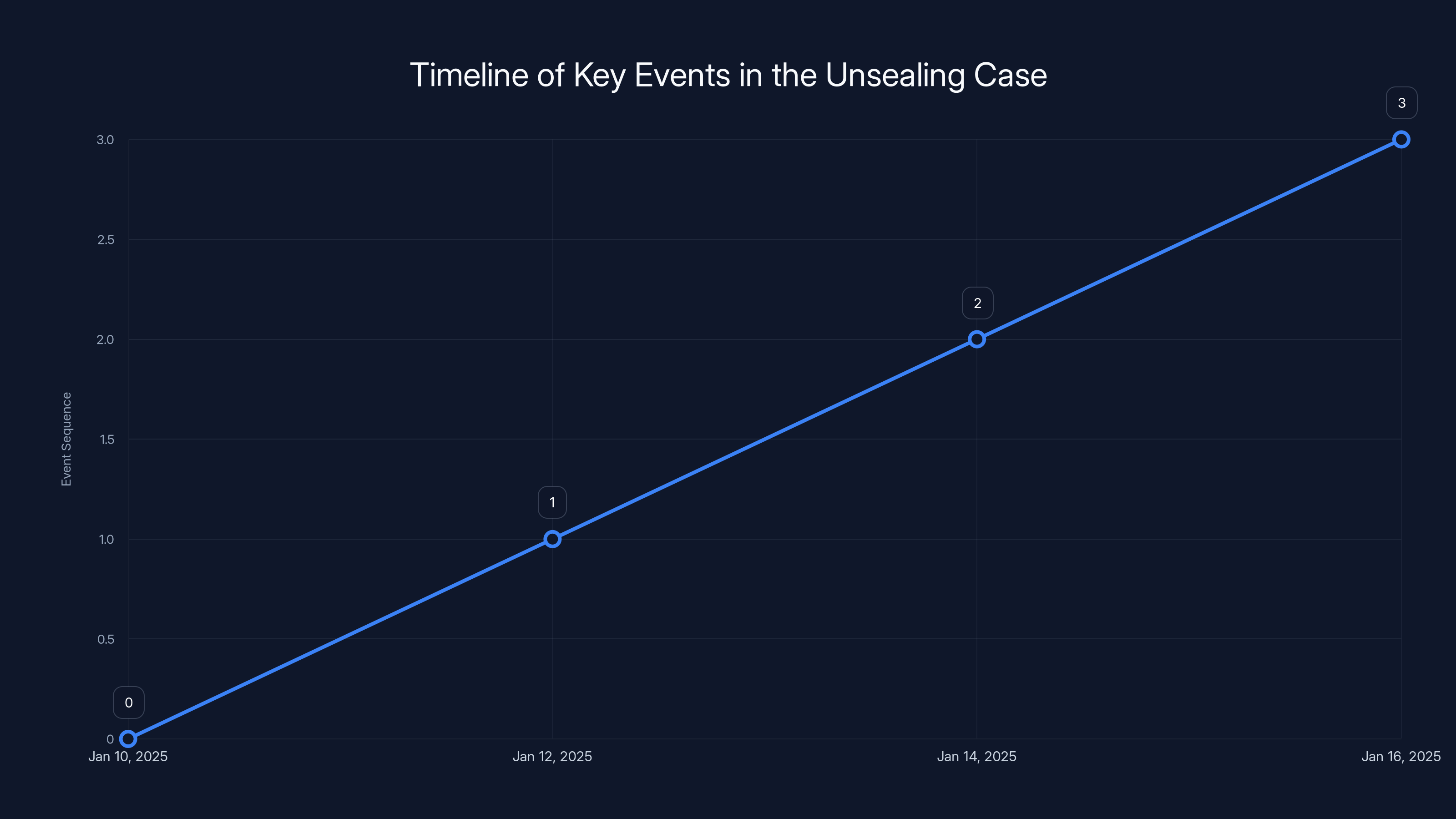

A judge agreed. On January 2, 2025, the court granted the temporary restraining order the same day it was requested. The order directed two key entities: the Public Interest Registry (PIR), the nonprofit that manages .org domains, and Cloudflare, the internet infrastructure company that provides DNS services for Anna's Archive's alternative domains.

The Technical Anatomy of a Domain Takedown

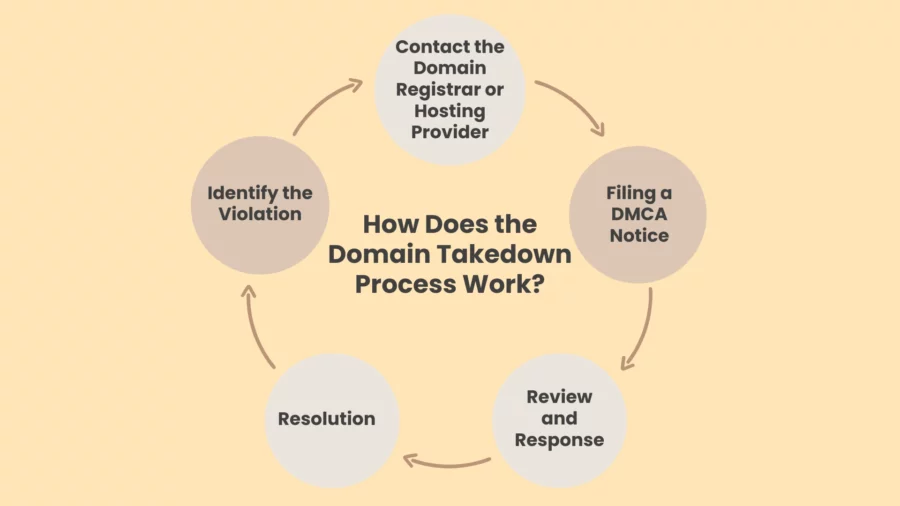

To understand how this actually worked, you need to know what PIR and Cloudflare can actually do.

PIR manages the .org registry. That means PIR maintains the authoritative list of which .org domains exist and who controls them. When someone wants to register annas-archive.org, they don't go directly to PIR. They go through a registrar, which is a company licensed to sell domains on PIR's behalf. There are thousands of registrars worldwide, including big names like Go Daddy and Namecheap.

The relationship looks like this: Registrant → Registrar → PIR. PIR has authority over the whole chain. If PIR tells a registrar "stop responding to queries for this domain," the registrar has to comply. And if that happens, the domain is effectively dead. Your computer asks "where is annas-archive.org?" and gets no answer, or gets an answer that says "this domain doesn't exist."

Cloudflare is different. Cloudflare is a middleman service. When you point your domain at Cloudflare's nameservers (which Anna's Archive did for multiple domains), Cloudflare intercepts all the DNS queries. Users ask Cloudflare "where is annas-archive.li?" and Cloudflare says "over here" and connects them to the actual server hosting the site.

This is more sophisticated than basic DNS. It's called a reverse proxy. Cloudflare sits between users and the origin server, which means they can see all traffic, modify headers, block requests, implement rate limiting, and more. From the record companies' perspective, Cloudflare was the perfect pressure point. They could technically choke off access to Anna's Archive's .li and .se domains even though those domains were registered outside the United States.

The temporary restraining order basically said: "PIR, suspend the .org domain. Cloudflare, stop providing nameserver service for the .li and .se domains. Do it today. Do it without telling the targets." And they did. By January 2, the .org domain was gone. By January 6, Cloudflare had also suspended service for the other domains.

But here's the thing about multiple domains and distributed infrastructure: one takedown doesn't mean total death.

Estimated timeline showing the progression of events leading to the unsealing of the case. Key actions occurred rapidly, emphasizing the urgency perceived by the plaintiffs.

The Persistence of Distributed Systems

Anna's Archive didn't disappear. It adapted.

The court filings show why the music companies were nervous about this scenario. Anna's Archive had already registered alternative domains in different jurisdictions. The main one that kept working was annas-archive.gs, registered in South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. South Georgia doesn't have the same enforcement relationships with US companies that the .org registry does. And if that goes down, there are likely other backups.

Moreover, as the court documents noted, Anna's Archive's operators are "completely anonymous, or in one instance, registered to what appears to be a bogus company with a dubious address in Liberia, which is not a party to the Hague Convention." The Hague Convention is an international treaty about serving legal documents. Countries that aren't part of it are harder to enforce against because you literally can't serve them notice.

This is the fundamental asymmetry of internet enforcement in 2025. The record companies have lawyers, money, and relationships with major US infrastructure providers. Anna's Archive has anonymity, multiple jurisdictions, and the willingness to operate outside legal structures entirely. You can take down their main domain. You can pressure their DNS provider. You can even get a court order. But if their operators have planned properly, none of that completely stops them.

Anna's Archive is still accessible as of early 2025. Not on the .org domain. But on other domains that aren't under US jurisdiction. The temporary restraining order achieved its immediate goal (getting the .org domain suspended before the operators could act) but didn't achieve the ultimate goal (permanently taking down Anna's Archive).

This is important because it shows both the power and the limits of copyright enforcement.

The Unsealing: When Secret Orders Become Public

On January 16, 2025, a judge ordered the case unsealed. The reason: "the purpose for which sealing was ordered has been fulfilled." In other words, the original purpose of keeping it secret (preventing Anna's Archive from moving their data before the domain was suspended) was no longer relevant because the suspension had already happened.

Once the documents became public, the internet could see exactly what happened. The complaint. The temporary restraining order. The motion for a preliminary injunction. Everything. And the details revealed just how carefully the music companies had planned this operation.

The request for anonymity hadn't been casual. The plaintiffs explicitly told the judge: "If Anna's Archive receives notice that the Record Company Plaintiffs are seeking this temporary restraining order, it will almost certainly release the sound recordings that it has illegally copied from Spotify to the public immediately."

Note the certainty. Not "might." Will. Almost certainly. The record companies had studied Anna's Archive's behavior and determined that giving notice would trigger the exact outcome they were trying to prevent. They needed speed more than fairness.

This decision to proceed ex parte raises real questions. Is emergency speed justified when the target is a website serving music rather than, say, stolen nuclear secrets? Different people will answer that differently. But what's clear is that the system allowed it. The judge was convinced. The order was issued. The domain was taken down within hours.

The Notification Problem: Learning About Your Own Case From the News

Anna's Archive's operators didn't find out they'd been sued until after the takedown. That's not an exaggeration. The order specifically stated that Anna's Archive "receive notice of the case by email only after the order is issued by the Court and implemented by PIR and Cloudflare."

So the sequence was:

- Domain vanishes

- Operators notice and wonder why

- Hours or days later, they get an email notifying them of the lawsuit

- They read court documents about what just happened

This is legally permissible for emergency orders, but it's profoundly asymmetrical. The plaintiffs got to choose the timing, choose the jurisdiction, and choose to proceed entirely in secret before any defense was mounted. The defendants found out after the damage was done.

When the case was unsealed and the documents went public, Anna's Archive's operators posted their own analysis. They noted that they hadn't actually released the Spotify recordings yet. They'd released metadata, but not the actual audio files. So why the emergency? The music companies' answer was that the risk of future release was sufficient justification.

You could argue either way on that. Emergency relief is supposed to prevent imminent irreparable harm. Does a threat to release music files in the future meet that standard? Or should the injunction have been slower, more deliberate, giving the defendants notice and a chance to respond?

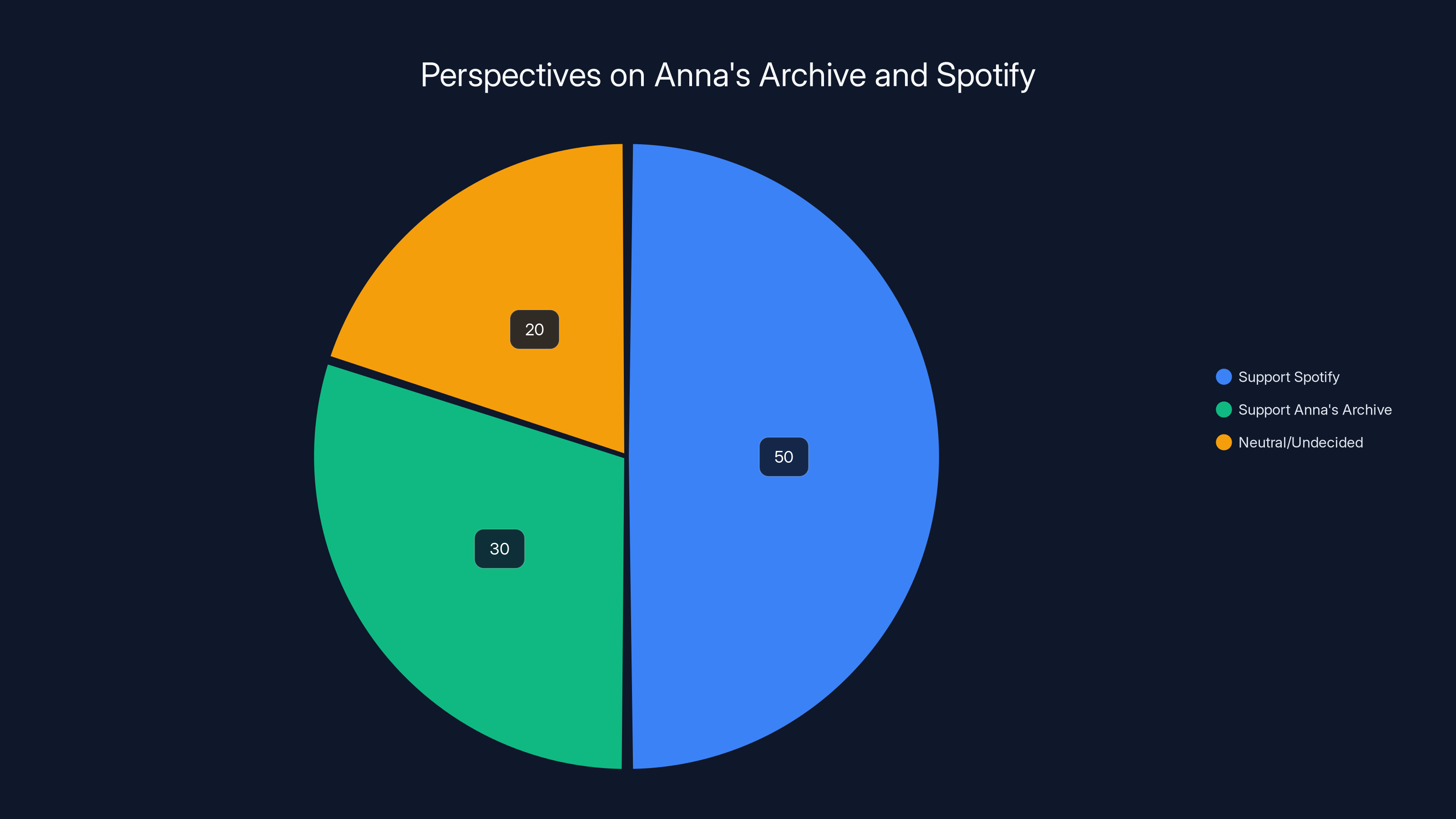

Estimated data shows a split in public opinion, with a majority supporting Spotify's stance, but a significant portion also sympathizing with Anna's Archive's library-like positioning.

How PIR and Cloudflare Became Enforcement Tools

One of the most interesting dynamics in this case is how two infrastructure companies became instruments of copyright enforcement.

Neither PIR nor Cloudflare broke any laws by complying with the court order. They had a legal obligation to obey US court orders. But their compliance transformed them into enforcement agents. They didn't sue anyone. They didn't make arguments about copyright. They just executed orders handed to them by the court.

This matters because it shows how copyright enforcement has evolved. It used to be that taking down online content meant suing the operator directly, seizing their servers, or compelling the hosting company to remove files. Those things still happen, but increasingly, enforcement targets infrastructure providers instead.

Why? Because infrastructure providers like Cloudflare are more responsive than anonymous operators. They're in the United States. They have lawyers. They care about maintaining relationships with governments and law enforcement. They comply with court orders quickly.

Cloudflare, in particular, has become a flashpoint in these debates. They sit in the middle of massive amounts of internet traffic. If they refuse to serve a domain, that domain becomes much harder to access from most parts of the world. They have enormous power, which is why both civil rights organizations and copyright holders want to influence their policies.

Cloudflare's stated position is that they comply with valid court orders but are "not a judge." If a government, company, or individual thinks content is illegal, they need to go through proper legal channels to get Cloudflare to take action. They won't act on complaints alone. They need a court order.

In this case, they got exactly that.

The Strategic Question: Is This Copyright Enforcement or Oppression?

This is where the case gets genuinely complicated, and reasonable people disagree.

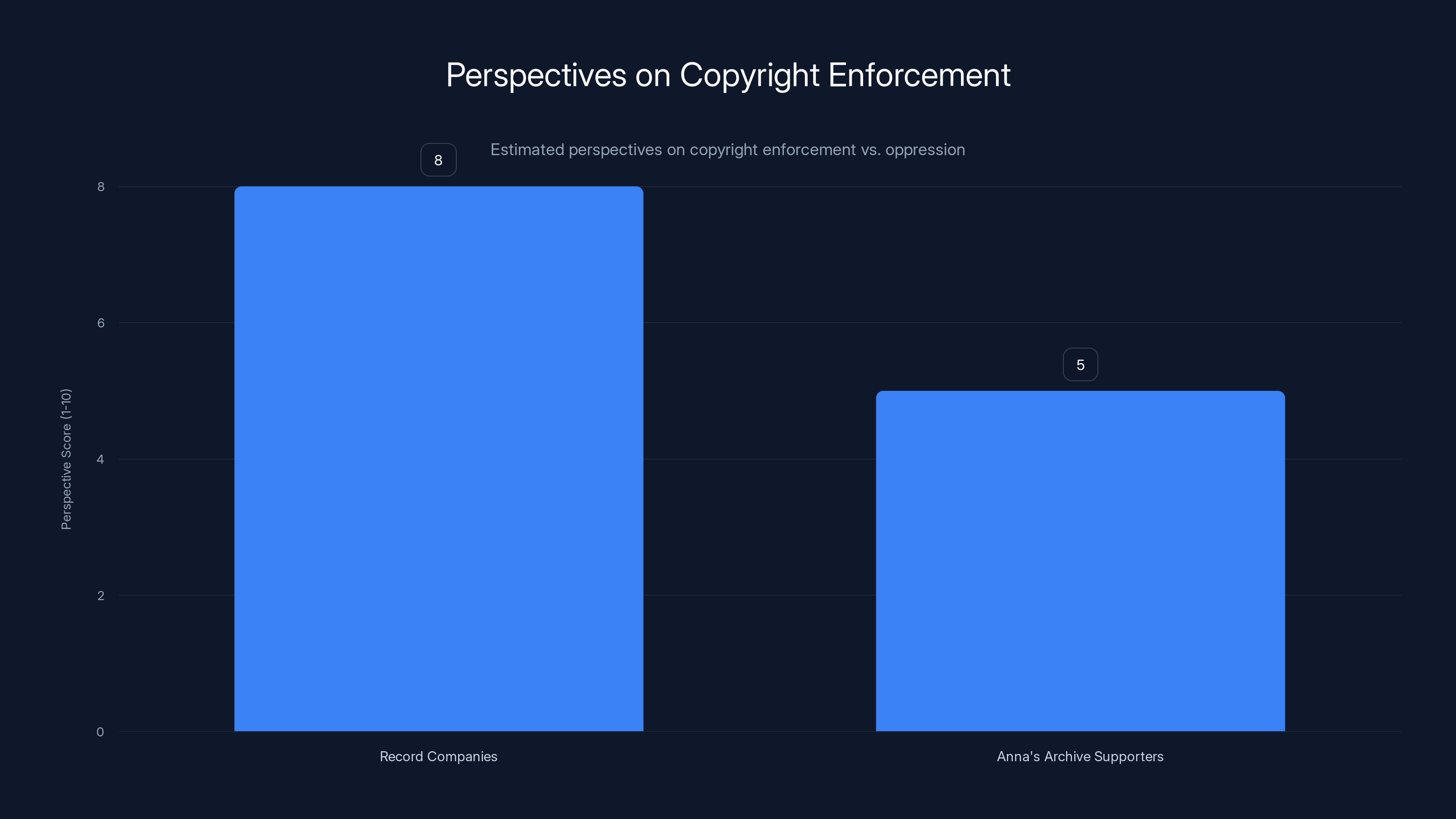

From the record companies' perspective, this is straightforward: Anna's Archive illegally copied millions of songs. The companies own those songs. They're losing money every day those files exist and might be distributed. The law gives them the right to enforce their copyright. They used the legal system properly. They got a court to agree with them. The enforcement worked.

From Anna's Archive supporters' perspective, this is corporate overreach: A group of mega-corporations used their wealth and legal resources to shut down a nonprofit library operating in good faith (according to their argument) with no notice or chance to respond. The founders couldn't even hire lawyers before their primary domain was gone. The anonymity of Anna's Archive's operators made it impossible to serve them properly. The whole operation felt designed to prevent any defense.

Neither perspective is obviously wrong. The companies did break copyright law. They did break it intentionally. But the speed and secrecy of the enforcement was extraordinary by normal legal standards.

There's a broader question underneath this case: What should happen when powerful institutions can move faster than individual operators, even when those operators are allegedly breaking the law? The legal system is supposed to provide due process. It's supposed to give both sides a chance to argue. But when one side can get a judge in a sealed courtroom in a day, and the other side doesn't even know about it until after the enforcement, due process becomes performative.

Anna's Archive's operators eventually filed a response to the preliminary injunction motion. They argued that the temporary restraining order was issued improperly, that they should have received notice, and that the music companies hadn't shown the risk was as imminent as claimed. But they were arguing these points after the damage was done. The .org domain was already suspended. The public had already noticed. The narrative was already set.

The Preliminary Injunction: Making It Permanent

The temporary restraining order was supposed to be emergency relief, good only until the case could be properly litigated. By law, TROs last 14 days unless extended. After 14 days, if the plaintiffs want the restrictions to continue, they need to get a preliminary injunction.

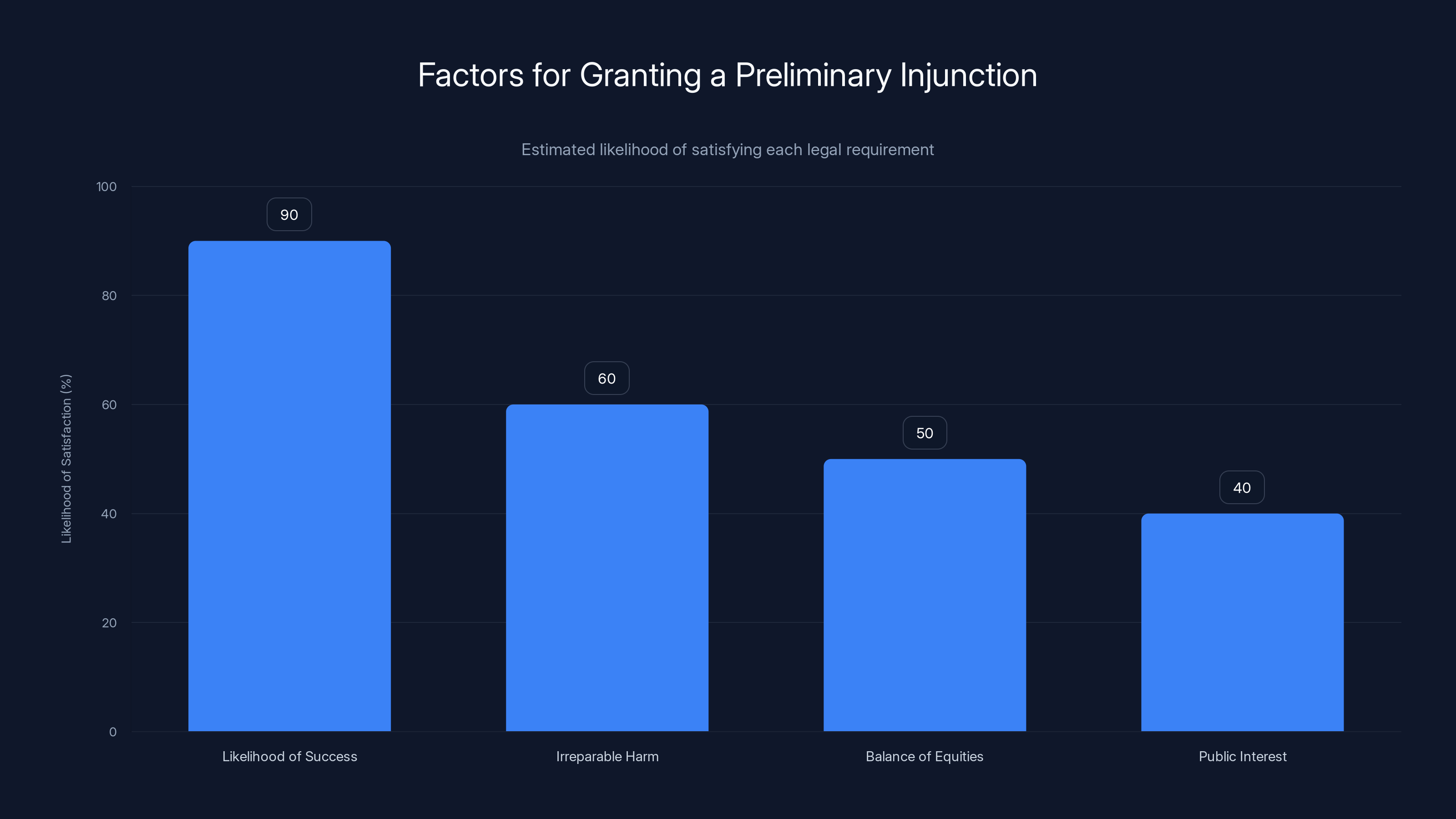

A preliminary injunction is harder to get than a TRO. It requires the plaintiffs to show: (1) reasonable likelihood of success on the merits, (2) irreparable harm if the order isn't issued, (3) that the balance of equities favors the plaintiff, and (4) that the injunction is in the public interest.

For obvious copyright infringement, the first factor is almost always satisfied. Spotify owns its music. Anna's Archive copied it. That's pretty clear.

The other factors are more debatable. Is allowing Anna's Archive to continue operating causing irreparable harm? That depends on how much piracy actually happens through Anna's Archive versus other methods. Are the equities in balance? That depends on whether you think copyright holders' interests outweigh the interests of preserving knowledge and preventing censorship. Is the injunction in the public interest? Different people will definitely disagree.

But the point is, once the preliminary injunction was granted (and the record companies almost certainly requested it), the domain suspension could continue indefinitely, pending a full trial on the merits.

At some point, if the case goes to trial, Anna's Archive would have a chance to present their defense. But that could take years. Meanwhile, the .org domain is gone, Cloudflare has stopped serving the .li and .se domains, and the practical effect is that Anna's Archive is less accessible to casual users who don't know the backup domains.

Estimated data shows the delay in notification to defendants in emergency legal cases, highlighting the asymmetry in the process.

The Jurisdictional Problem: Suing Anonymous Operators

Here's a problem the court documents highlight: Anna's Archive isn't a company. It doesn't have a CEO or a registered office. It's a project run by anonymous operators who probably don't live in the United States.

The music companies sued "Anna's Archive" as if it were a legal entity. But what is Anna's Archive exactly? A nonprofit? A collective? A for-profit enterprise? The court documents don't clearly establish that Anna's Archive is even a legally cognizable entity that can be sued.

There's a person or group of people running Anna's Archive. They're the ones who should probably be sued. But they're anonymous. Finding them, identifying them, and serving them with legal papers is much harder than ordering a domain registrar to pull a domain.

The record companies' own filings acknowledge this: "The websites Anna's Archive uses are either completely anonymous, or in one instance, registered to what appears to be a bogus company with a dubious address in Liberia, which is not a party to the Hague Convention."

This is a feature, not a bug. Anna's Archive is designed to be hard to shut down legally because the operators are hard to identify and hard to reach. The only way to really enforce against something like that is to go after the infrastructure: the domains, the servers, the DNS providers, the payment processors. And that's exactly what Spotify did.

The Record Companies' Victory and Its Limits

Spotify and the three record companies won this round. They got the domain suspended. They stopped (or at least slowed) the distribution of their copyrighted works. They demonstrated to other potential pirates that they have both the resources and the legal sophistication to pursue enforcement through the court system.

But did they actually solve the problem? Anna's Archive is still running on backup domains. The Spotify metadata (though not the audio files) was already released. Anyone determined to find the data could still access it. And most importantly, they demonstrated a playbook for how to distribute a major music catalog, which other operators could learn from.

In enforcement terms, this is a classic pyrrhic victory. You win the battle but don't address the underlying issue. Tens of thousands of people now know that Spotify's entire catalog can be downloaded and backed up. If Anna's Archive had just disappeared quietly, fewer people would have known about it. Instead, the lawsuit drew international attention to exactly what they were trying to hide.

This is a known problem in IP enforcement. The remedy itself becomes the story. By suing Anna's Archive in a high-profile way, the music companies inadvertently advertised what Anna's Archive does. The Streisand Effect in action.

That said, from the companies' perspective, the alternative (doing nothing) was worse. If they didn't enforce, it sets a precedent that large-scale copyright infringement is acceptable if the operator is anonymous enough.

The Broader Implications for Internet Enforcement

This case demonstrates several trends in how copyright enforcement and internet control are evolving in 2025.

First, the willingness to use sealed, ex parte court orders to preempt responses. This isn't new, but it's becoming more common. Speed is prioritized over due process when the stakes are high enough.

Second, the targeting of infrastructure companies rather than individual operators. PIR and Cloudflare didn't infringe any copyright. But they could be forced to participate in enforcement anyway. This creates perverse incentives for infrastructure companies to over-comply with requests, since the legal standard is just "if you have a court order, you have to comply."

Third, the recognition that the internet is both distributed and surprisingly concentrated. Anna's Archive was distributed across multiple domains in multiple jurisdictions. But almost all of those domains still relied on US-based infrastructure (Cloudflare's nameservers) or US-based registries (.org). There was a chokepoint, and the companies found it.

Fourth, the limits of enforcement. Even with a court order, a temporary restraining order, cooperation from major infrastructure companies, and the power of the US government behind them, the companies couldn't permanently take down Anna's Archive. The site is still accessible. The data is still available. The infrastructure is just less convenient to access.

Estimated data shows a higher score for record companies' perspective on enforcement, while Anna's Archive supporters view it as oppressive. (Estimated data)

Questions About Proportionality and Public Interest

There's a deeper question lurking underneath this case: Is this enforcement proportional, and is it actually in the public interest?

From one angle, Anna's Archive had no right to Spotify's copyrighted works. Spotify pays billions of dollars to music rights holders. If people can just download the entire catalog for free from a backup, Spotify's business model collapses. The companies were right to defend their property.

From another angle, Anna's Archive positioned itself as a library, not a piracy site. Libraries preserve knowledge. They make things accessible. Some of the people using Anna's Archive might be doing so for legitimate reasons: researchers, archivists, people in countries where Spotify doesn't operate. Taking down the whole site affects all of them equally.

The court documents don't show that the judge considered whether there was any legitimate purpose for having a backup of Spotify. The case was framed entirely as a piracy issue. And legally, that's correct. Copying without permission is infringement, full stop. But just because something is legally correct doesn't mean it's wise policy.

There's an implicit argument in the record companies' filings: No legitimate purpose could possibly justify having a backup of Spotify's entire catalog. If someone wants to preserve music, they should use Spotify themselves. If they want to research music availability, they should do it through proper channels. If they want offline access, they should use Spotify's actual offline features.

That's not an unreasonable position. But it's also closing off options that users might have benefited from.

What Happens Next

The preliminary injunction hearing presumably happened in mid-January 2025. The record companies almost certainly got what they wanted. The domain suspension will likely continue indefinitely, at least until a full trial on the merits (which could take years or never happen).

Anna's Archive will continue to operate on backup domains. They'll adapt. They might implement more security. They might move more of their infrastructure outside the US.

Other shadow libraries are watching. They're noting the playbook: get a court order, move fast, don't give the target notice, lean on infrastructure providers. Some of them are probably already implementing countermeasures.

The record companies will claim victory, and they're not wrong. They stopped (or slowed) the distribution of their intellectual property. But they haven't solved the underlying problem. As long as people want to preserve and share copyrighted works outside of official channels, there will be organizations like Anna's Archive trying to do it.

The fundamental asymmetry remains: The companies can pursue legal action and win court orders. The operators can hide, move infrastructure, and prepare contingency plans. It's an arms race, and this case is just one battle in a much longer war.

The Technical Perspective: How Domain Enforcement Actually Works

Let's dig deeper into the technical mechanics of how domains get suspended, because that's where the actual leverage in this case existed.

When you type "annas-archive.org" into your browser, your computer doesn't automatically know where to find that site. It needs to ask. First, it queries a recursive resolver (usually operated by your ISP or a service like 8.8.8.8 from Google). The resolver asks the root nameservers "where do I find .org domains?" They respond with the address of the .org nameservers (operated by PIR). The resolver then asks PIR's nameservers "where is annas-archive.org?" PIR responds with the answer.

If PIR says "I don't have that domain," the query fails. Your browser shows an error. The website is unreachable.

PIR has this power because they're the authoritative registry for .org. Every .org domain that exists exists because PIR says it does. If PIR revokes it, it's gone. This is why the temporary restraining order specifically targeted PIR. The order basically said: "Stop advertising that annas-archive.org exists."

For the .li and .se domains (Lithuania and Sweden), the situation was technically different but functionally similar. Those domains were registered with registrars outside the US, so PIR didn't have direct control. But both .li and .se rely on internet infrastructure that runs through the US at some point. More importantly, Anna's Archive was using Cloudflare as their DNS provider.

Cloudflare operates what they call an "authoritative nameserver" service. When you use Cloudflare to manage DNS for a domain, you point your domain registrar to Cloudflare's nameservers. Then Cloudflare responds to DNS queries for your domain. If Cloudflare stops responding, the domain is effectively dead (unless there are redundant DNS providers, which Anna's Archive may or may not have had).

The temporary restraining order targeted both PIR and Cloudflare. PIR suspended the .org domain (which they control absolutely). Cloudflare stopped responding to queries for the .li and .se domains (which they provided DNS for).

This is the technical leverage in copyright enforcement: Most domains, even those registered outside the US, depend on US-based infrastructure to be functional. Take out Cloudflare, and the domain stops working. Take out Verisign (which manages .com) and half the internet disappears. This concentration of control is what makes enforcement possible.

Likelihood of success is high due to clear copyright infringement, but other factors like irreparable harm and public interest are more contentious. Estimated data.

The Payment Processing Angle: The Missing Weapon

Interestingly, the court documents don't mention payment processors. Stripe, Pay Pal, and other companies that handle online payments are often part of enforcement strategies. If you cut off someone's payment processing, you starve them of revenue.

Anna's Archive apparently accepted cryptocurrency as well as traditional payment methods. That's much harder to shut down. You can't get a court order against Bitcoin. It's decentralized. But if they were also accepting credit cards or bank transfers, those could potentially be targeted.

The fact that the lawsuits focused on domains and DNS rather than payments suggests either: (1) Anna's Archive's payment infrastructure was already separate from their US operations, or (2) the record companies expected the domain suspension to be sufficient and didn't need to go after payments.

Most likely, Anna's Archive learned from other enforcement actions against similar sites. They kept their payment processing separate and in different jurisdictions. Smart operators know that revenue is often the first thing to be cut off.

Comparing This to Other High-Profile Takedowns

This Anna's Archive case follows a pattern we've seen before with other major piracy operations.

Thepiratebay.org was taken down in Sweden in 2006, but mirrors immediately appeared. It came back. Then it moved to .se, then .mn, then other domains. The site still exists in some form today despite being one of the most targeted piracy sites ever.

Megaupload, a file-hosting service used for piracy, was seized by the FBI in 2012. It was a much more dramatic enforcement action: law enforcement actually raided the company's offices, seized servers, arrested the founder. And yet clones appeared within weeks. Mega.nz (now Megaupload's successor) launched with stronger encryption specifically designed to prevent law enforcement from taking action again.

Kickass Torrents was shut down in 2015 when the FBI arrested its operator. Again, clones appeared. The domain name piratebay.info is one of many.

What these cases show is that domain takedowns are Pyrrhic victories. They disrupt access temporarily. They raise the cost of operation. But they don't permanently stop determined operators. The ecosystem adapts. New domains appear. Infrastructure moves. Operations relocate.

Anna's Archive, with its anonymous operators and multiple backup domains, should be particularly resilient. This takedown will slow them down, not stop them.

The Business Case for Enforcement

Why do the record companies pursue enforcement actions that they know won't completely work? Why spend money on lawyers and court cases if the outcome is temporary?

There are several reasons:

First, deterrence. By showing that they will pursue legal action, the companies hope to discourage others from starting similar projects. Maybe 100 people are thinking about building Anna's Archive clones. If they see Anna's Archive being sued, maybe 80 of them decide not to. That's valuable even if Anna's Archive itself continues.

Second, regulation. Copyright enforcement lawsuits create case law, legal precedent, and court records that companies and countries can point to when making policy. Every takedown sets a precedent that the next takedown can build on.

Third, practical impact. Even if Anna's Archive is accessible through backup domains, the takedown causes friction. Fewer people find it. Casual pirates are diverted to other services. These aren't huge wins, but they're measurable.

Fourth, signaling to investors and shareholders. By aggressively enforcing copyright, the companies signal that they're protecting the value of their intellectual property. Investors want to see companies defending their assets. A lawsuit is visible evidence of that.

Fifth, just on principle. If companies don't enforce their copyrights, they can lose them under some legal theories. Copyright has to be actively defended or it can be forfeited. So there's a legal reason to take action even if the action isn't perfectly effective.

The Global Enforcement Landscape

One interesting aspect of this case is that it was filed in New York, which happens to be a copyright enforcement hotspot. Why New York and not California or Texas or somewhere else?

Probably because several of the record companies (Sony, Universal) have major offices in New York. But also because the Southern District of New York has judges and courts that are familiar with copyright cases and knowledgeable about digital piracy. They've seen it before. They move quickly.

The music companies could have filed in different jurisdictions with different standards. Some countries are more protective of copyright; some are more protective of speech and privacy. The choice to file in SDNY suggests the companies wanted a jurisdiction they knew would be favorable.

This is increasingly true with internet enforcement globally. Companies forum-shop, filing in jurisdictions with favorable laws and judges. Anna's Archive, being anonymous and distributed, couldn't effectively choose their forum. They got sued in New York regardless of where they actually operate from.

Critical Analysis: Was This Enforcement Justified?

Step back for a moment and ask: Was what Anna's Archive did actually so wrong that it deserved this treatment?

From a pure legal standpoint, the answer is obviously yes. Copyright law is clear. Copying and distributing copyrighted works without permission is infringement. Anna's Archive did exactly that. The lawsuit and the takedown were legally justified.

But law and justice aren't always the same thing. And policy and law aren't always well-aligned.

Anna's Archive positioned itself as a library. Libraries preserve knowledge and make it accessible. Historically, libraries did this by purchasing copies and lending them. Modern libraries do similar things with digital materials (though with more licensing restrictions). Could Anna's Archive have been operating a legitimate library function?

The answer is probably no, or at least not in the way they were operating. They were making Spotify's entire catalog available without Spotify's permission or compensation. That's not how libraries work. Libraries pay for access; Anna's Archive didn't.

But there's still a broader question: Should Spotify's music be preserved somewhere? If Spotify ever goes out of business or deletes music (which it does, sometimes) or loses access to certain rights, is there value in having a backup somewhere?

One could argue yes. Digital preservation is a real problem. Many things that exist only digitally are at risk of being lost forever if the companies maintaining them go away or decide to delete them. Music, in theory, is subject to the same risk.

But Spotify is a financially stable company backed by major investors. The music industry is the primary defender of those rights. It's not like we're worried Spotify will suddenly disappear and take all music with it.

Still, the question of digital preservation and digital permanence is real. And Anna's Archive was genuinely trying to address it (or at least positioning itself as doing so). That doesn't make the copyright infringement okay, but it complicates the simple narrative of "site breaks law, gets sued, deserves what it gets."

What This Means for Internet Infrastructure Companies

From PIR and Cloudflare's perspective, this case shows both their power and their vulnerability.

They have power because they sit at critical chokepoints in the internet. Take them out, and websites disappear. Governments and corporations and rights holders all want that power available to them.

They're vulnerable because they can be compelled to exercise that power. Once a court orders them to do something, they have to do it. They don't get to decide whether the order is right or wise. They just have to comply.

This creates ongoing tension. Civil liberties groups and internet freedom advocates argue that infrastructure companies should resist overly broad orders and protect user privacy and access. Copyright holders and law enforcement argue that infrastructure companies should readily comply with court orders to prevent piracy and criminal activity.

Both sides are right about something. Courts orders should generally be complied with. But the power that infrastructure companies wield—the ability to make entire websites disappear—should probably be used cautiously.

Cloudflare has actually been in the middle of these debates before. They've had to decide whether to provide service to controversial websites. They generally try to stay neutral and comply with legal requirements while pushing back against illegal demands. In this case, they had a court order. They complied. That's the right move legally and operationally.

But it's worth noting that the outcome is that Cloudflare is now participating in copyright enforcement. They didn't want to. They were ordered to. But the effect is the same.

The Appeal and the Longer Legal Story

Anna's Archive almost certainly filed an appeal of the temporary restraining order and the preliminary injunction (if one was granted). The court documents released in January were the beginning of the case, not the end.

What happens on appeal? That depends on what arguments Anna's Archive made and how sympathetic the appellate court is to them.

They could argue:

- The temporary restraining order was issued improperly without adequate notice

- The music companies didn't meet the standard for emergency relief

- The injunction shouldn't apply to Anna's Archive as an entity because it's not properly defined

- There are First Amendment implications (though this is a weak argument for straight copyright infringement)

- The remedy (taking down a domain) is overbroad compared to the actual harm

None of these are strong arguments legally. The copyright infringement is clear. The companies' fear of distribution is reasonable. The court's decision to act quickly is within judicial discretion.

But on appeal, sometimes marginal arguments get traction if the appealing party can make a novel or interesting legal point. We'll see if Anna's Archive's lawyers can find one.

More likely, the preliminary injunction is upheld, the case goes to trial (potentially in a few years), the companies win at trial, and Anna's Archive continues to operate on backup domains indefinitely.

The Precedent This Sets

Every court case sets precedent. This one probably doesn't set dramatic new precedent because copyright enforcement is well-established law. But it does reinforce some things:

- Courts will grant emergency ex parte relief for copyright infringement if the defendant is likely to flee or destroy evidence

- Infrastructure companies can and will be ordered to comply with takedown orders

- Global distributed infrastructure is not necessarily a defense if the infrastructure passes through the US

- Anonymous operations don't exempt you from being sued; courts will just name you as "John Doe" or similar

- Cryptocurrency and anonymous hosting don't provide complete protection against enforcement

These are all things that were already known, but this case reinforces them with a recent, high-profile example.

For future operators of shadow libraries or piracy services, the lessons are: (1) Don't assume anonymity protects you, (2) Don't assume non-US domains protect you, (3) Don't assume being sued under seal means you have time to move your stuff, (4) Plan for your infrastructure to be attacked at any time, (5) Have redundancy and backup systems.

For future companies protecting intellectual property, the lessons are: (1) The court system is willing to move fast in copyright cases, (2) Infrastructure companies will cooperate if you get a court order, (3) Ex parte relief is available when you need it, (4) Moving fast and denying the defendant notice is legally permissible and often strategically necessary.

The Broader Question: Piracy in 2025

This case reveals something important about the state of piracy and copyright enforcement in 2025.

Despite decades of lawsuits, arrests, and enforcement actions, piracy hasn't been eliminated. In fact, it's arguably become easier and more sophisticated. The technology gets better. The operations get more distributed. The operators get smarter about staying anonymous and resilient.

At the same time, enforcement has also evolved. It's faster, more sophisticated, and more willing to use emergency measures.

The result is an arms race that neither side is winning decisively. Companies take down sites; operators rebuild them elsewhere. Operators implement better security; companies find new enforcement angles. It's a perpetual conflict with no clear end state.

Streaming services like Spotify have reduced piracy somewhat (they're much more convenient than pirating), but they haven't eliminated it. There's always a percentage of users who will pirate for various reasons: they don't have money, they live in countries where services aren't available, they want offline access that services don't allow, they distrust the services themselves, they just enjoy the rebellious aspect.

As long as that demand exists, there will be operators willing to supply it, even if they risk legal action. Anna's Archive exists because there's demand for a complete music archive. The takedown might slow that demand down, but it won't eliminate it.

TL; DR

- Sealed Lawsuit: Spotify and three major record labels sued Anna's Archive in secret, with the case initially sealed from public view

- Emergency Order: A judge granted a temporary restraining order the same day it was requested, before Anna's Archive even knew they were being sued

- Domain Suspension: The .org domain was suspended within hours, along with Cloudflare DNS service for backup domains

- Limited Notification: Anna's Archive wasn't notified of the lawsuit until after the takedown was already implemented

- Site Persists: Despite the takedown, Anna's Archive remains accessible through alternative domains like .gs

- Asymmetric Enforcement: The case shows how the legal system can move faster than the defendants it targets, raising questions about due process versus emergency relief

- Infrastructure as Chokepoint: Most internet domains, even those registered outside the US, depend on US-based infrastructure (Cloudflare, registries), which creates enforcement leverage

FAQ

What is Anna's Archive?

Anna's Archive is a "shadow library" project that copies and preserves copyrighted works, particularly books and music, making them freely available online. The project positions itself as a digital preservation effort, though it operates in explicit violation of copyright law in most jurisdictions. The site is named after Alexandra Elbakyan, founder of Sci-Hub, another controversial shadow library focused on academic papers.

Why did Spotify sue Anna's Archive specifically?

Spotify and the record labels sued Anna's Archive because the site had downloaded Spotify's entire catalog (over 100 million songs) and announced plans to preserve and potentially distribute this content. Rather than waiting for the distribution to happen, the companies moved quickly to get a court order and shut down the site's primary domain before the operators could act on their stated plans.

How did the court order work technically?

The court ordered two organizations to stop serving Anna's Archive: the Public Interest Registry (PIR), which manages .org domains, and Cloudflare, which was providing DNS services for Anna's Archive's alternative domains. Once PIR stopped advertising that the .org domain existed and Cloudflare stopped responding to DNS queries for the other domains, accessing those sites became impossible for most users.

Could Anna's Archive continue operating after the domain suspension?

Yes, Anna's Archive has continued operating on alternative domains like annas-archive.gs (registered in South Georgia, outside US jurisdiction). The domain suspension caused friction and reduced casual access, but determined users can still find and access the site. The operators had planned for this possibility with backup infrastructure.

What does "ex parte" mean in this case?

Ex parte means "without the other party." An ex parte temporary restraining order is issued without giving the defendant notice or a chance to respond, which is only supposed to happen in genuine emergencies where waiting for the normal legal process could cause irreparable harm. In this case, the court agreed that giving Anna's Archive notice would allow them to distribute the music before enforcement could occur.

Is this type of enforcement common?

Copyright enforcement against piracy is common, but sealed lawsuits and ex parte orders are less common and more controversial. Most copyright cases are filed publicly, and defendants get notice. Using emergency procedures to deny notice is typically reserved for situations where there's a genuine immediate threat, which makes this case more aggressive than typical copyright enforcement.

What happens now with Anna's Archive's case?

The temporary restraining order eventually expires or gets converted into a longer-term preliminary injunction. The case will likely continue through litigation, potentially for years. Anna's Archive may appeal the orders, and there will be additional court hearings where both sides get to present their full arguments. Unless the operators are identified and arrested, or unless they voluntarily shut down, the site will likely continue operating on backup domains.

Could other countries' copyright holders use the same strategy?

Yes, any copyright holder in any country could potentially use similar strategies, but it depends on having access to courts willing to grant emergency relief and having infrastructure companies willing to comply with orders. The US has particularly strong copyright protections and infrastructure that's concentrated enough to make this strategy effective. Other countries' approaches vary significantly.

What's the difference between Anna's Archive and mainstream streaming services?

Mainstream streaming services like Spotify pay rights holders for the music they distribute, and they implement access controls (subscriptions, ads) to manage who can access content. Anna's Archive copies the content and makes it freely available without compensation to rights holders or any access controls. From a legal perspective, this is the crucial difference—payment, licensing, and rights management.

What does this case reveal about internet enforcement in 2025?

The case reveals that enforcement has become faster and more willing to use emergency procedures, that most domains ultimately depend on US-based infrastructure which creates enforcement leverage, that infrastructure companies will comply with court orders, and that sophisticated operators can anticipate enforcement and maintain backup systems that keep their operations partially functional even after successful takedowns.

This case represents a moment where traditional copyright enforcement law met modern distributed internet infrastructure and anonymous operations. The record companies won tactically—they got the domain taken down, they demonstrated that enforcement is possible, they showed they're willing to spend resources defending their intellectual property. But they didn't achieve total strategic victory. Anna's Archive is still online. The knowledge of how to download Spotify's entire catalog is now public. And every attempt at enforcement creates headlines and renewed attention.

It's this dynamic—temporary tactical victories that don't resolve the underlying strategic questions—that characterizes intellectual property enforcement in the modern internet. Neither side can completely win, but both sides will keep trying.

Key Takeaways

- Spotify and record labels filed a sealed lawsuit against Anna's Archive and obtained an ex parte temporary restraining order within 24 hours, taking down the .org domain before the operators knew they were being sued

- The enforcement strategy targeted infrastructure providers (PIR and Cloudflare) rather than individual operators, demonstrating how modern copyright enforcement leverages US-based internet infrastructure as chokepoints

- Ex parte emergency relief was granted because courts found that giving notice would allow Anna's Archive to distribute the copied music and move infrastructure before enforcement could occur

- Anna's Archive persisted through alternative domains (.gs, .li, .se), showing that domain suspension is tactically effective but strategically limited for truly distributed operations

- The case reveals the asymmetry in internet enforcement: companies can use sealed courts and emergency procedures to move faster than defendants can organize a legal defense

Related Articles

- Anna's Archive .org Domain Suspension: What It Means for Shadow Libraries [2025]

- Anna's Archive Court Order: Why Judges Can't Stop Shadow Libraries [2025]

- Nintendo Switch 2 Game-Key Cards Debate: Why Sega's Choice Matters [2025]

- Cloudflare's $17M Italy Fine: Why DNS Blocking & Piracy Shield Matter [2025]

- 20 Weirdest Tech Stories of 2025: From Fungal Batteries to Upside-Down Cars