Introduction: When Safety Nets Become Surveillance Tools

Imagine you need to visit your local Social Security office to update your bank account information. It's a routine task that millions of Americans handle every year. But here's what you might not know: if you're not a citizen, that simple appointment could now become a target for federal immigration agents.

The Social Security Administration has quietly begun sharing appointment details with Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. When ICE asks whether someone has an upcoming appointment, SSA workers are now instructed to provide the date and time. This isn't buried in fine print or hidden in bureaucratic policy documents. It's a verbal directive that fundamentally reshapes how a government agency meant to serve all people now operates, as detailed by Wired.

This shift represents something much larger than a simple data-sharing agreement. For decades, the SSA operated as what government officials called a "safe space." People could walk through those doors regardless of immigration status. They could access benefits they were legally entitled to without fear of apprehension. That social contract has been shattered, as noted by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

What makes this particularly alarming isn't just the policy itself. It's the way it was implemented: quietly, verbally, to select offices. It's the lack of formal updates to the official rules. It's the chilling effect it will have on millions of people who need services but now face the prospect of immigration enforcement while seeking help.

The implications ripple far beyond Social Security offices. This precedent signals that other government agencies could follow suit. If the SSA can be transformed into an extension of immigration enforcement, what's to stop the IRS, the Department of Health and Human Services, or local health departments from doing the same?

This isn't about immigration policy debate. Reasonable people disagree on immigration enforcement. But this crosses a different line entirely: it weaponizes access to essential government services and uses the infrastructure built to help people against them.

Let's examine what happened, why it matters, and what the consequences could be for millions of Americans and noncitizens living in the United States.

TL; DR

- The Directive: Social Security Administration workers are now instructed to share in-person appointment details with ICE agents, marking a dramatic policy shift from decades of precedent

- The Scope: This applies to citizenship and immigration information already being shared, but now extends to real-time appointment scheduling details that could enable targeted enforcement

- The Legal Problem: A federal judge has already ruled that the IRS and SSA cannot share taxpayer data with DHS or ICE in another case, creating legal conflict, as reported by the Asian Law Caucus

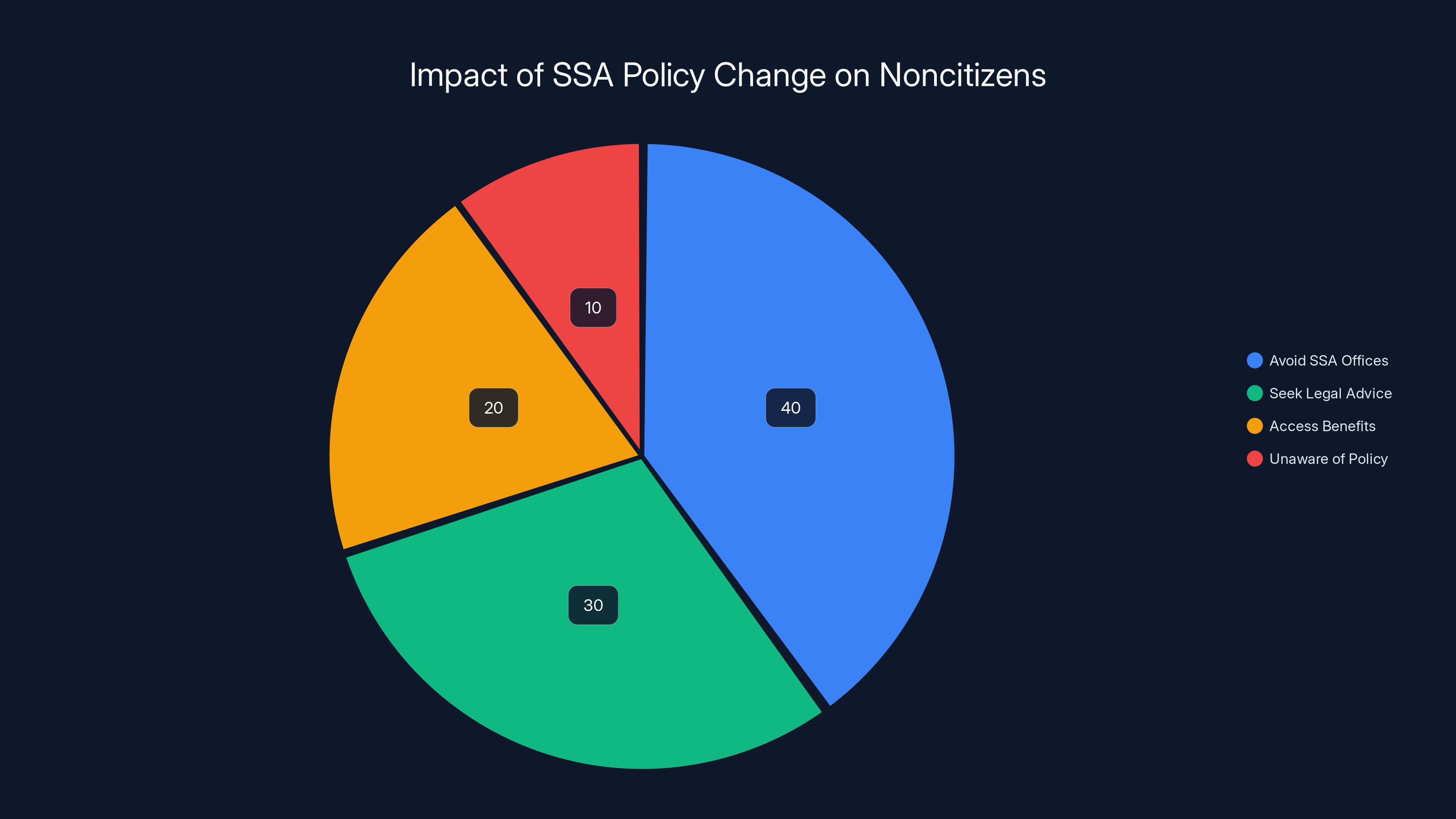

- The Real Impact: Noncitizens and mixed-status families will likely avoid SSA appointments, losing access to earned benefits and critical services

- The Precedent: Once a government agency becomes an enforcement tool, rebuilding public trust becomes nearly impossible

The timeline shows key moments in the evolution of data sharing policies under the Trump administration, highlighting the consolidation of immigration enforcement power. (Estimated data)

The Quiet Policy Shift Nobody Saw Coming

The order arrived as a verbal directive. No official policy memo. No public announcement. No formal rule change. SSA employees at certain offices received instructions that fundamentally altered how they interact with the Department of Homeland Security, as reported by Wired.

If ICE comes asking, they're now told to confirm whether someone has an upcoming appointment and provide the specific date and time. This breaks with historical practice. For nearly a century, the SSA maintained what officials describe as a firewall between immigration enforcement and benefit administration.

Why would anyone need to go to an SSA office in person? The agency conducts the majority of its business over the phone. But certain situations still require in-person visits. If you're deaf or hard of hearing, you might need a sign language interpreter. If you need to change direct deposit information for sensitive reasons, you might prefer an in-person conversation. And here's the critical part: noncitizens are required by law to appear in person to prove continued eligibility for any benefits they receive.

This creates a trap. Legal immigrants, visa holders, and people with work authorization need to show up in person to keep the benefits they're entitled to. They have no choice. Now those required office visits could trigger immigration enforcement.

The directive wasn't formalized in the SSA's Program Operations Manual. No official public notice was updated to reflect this change. It exists in the gray space of unwritten directives, the kind that avoid public scrutiny precisely because they're communicated verbally and documented only in the memories of the people receiving them.

This approach raises serious questions about accountability. How do citizens and noncitizens even know this policy exists? How can someone give informed consent to something they don't know about? How can civil rights organizations challenge something that's never been formally announced?

Context: How We Got Here

This policy didn't emerge in a vacuum. It's the latest escalation in a years-long effort by the Trump administration to consolidate immigration enforcement power and expand access to personal data held by government agencies.

Back in April 2024, the Trump administration launched what some called a "data pooling" operation. It created unprecedented access to sensitive information from across the federal government: Social Security Administration records, Department of Homeland Security databases, Internal Revenue Service tax information. The goal was explicit: create a unified database for immigration enforcement.

By November, the SSA had made these arrangements official. The agency quietly updated a public notice stating it was now sharing "citizenship and immigration information" with DHS. Most people never saw this notice. Most media outlets didn't report it. It passed almost silently into the official record.

But government employees noticed. A former SSA official told journalists that it was "shockingly clear that there was interest in getting access to immigration data by the Trump administration." The language is careful, professional, but the meaning is unmistakable: something fundamental had changed.

Leland Dudek, who served as acting commissioner of the Social Security Administration, described what he was seeing as "SSA becoming an extension of Homeland Security." He wasn't using inflammatory language. He was describing structural transformation.

The SSA has existing data-sharing agreements with DHS. These agreements cover certain categories of information and include oversight mechanisms. Multiple people have to sign off. There's paperwork. There's a process. But someone's appointment time and schedule hadn't historically been included in those formal agreements.

Then came December 2024. The SSA updated its Program Operations Manual System to allow for what it called "as-needed disclosures" of "non-tax return information" to law enforcement outside of existing data-sharing agreements. These disclosures were supposedly to be approved by the SSA's general counsel on a case-by-case basis.

But here's where it gets murky. Dudek points out that the language creates ambiguity about where routine requests become routine practice. Once you start saying yes to ICE requests for appointment data, when does that become standard operating procedure? When does case-by-case become automatic?

Estimated data shows that Social Security services are most impacted by data-sharing policies, potentially affecting 40% of immigrant interactions with government services.

Who Gets Hurt: The Real-World Impact

The policy sounds abstract until you consider who actually shows up at SSA offices and what they stand to lose.

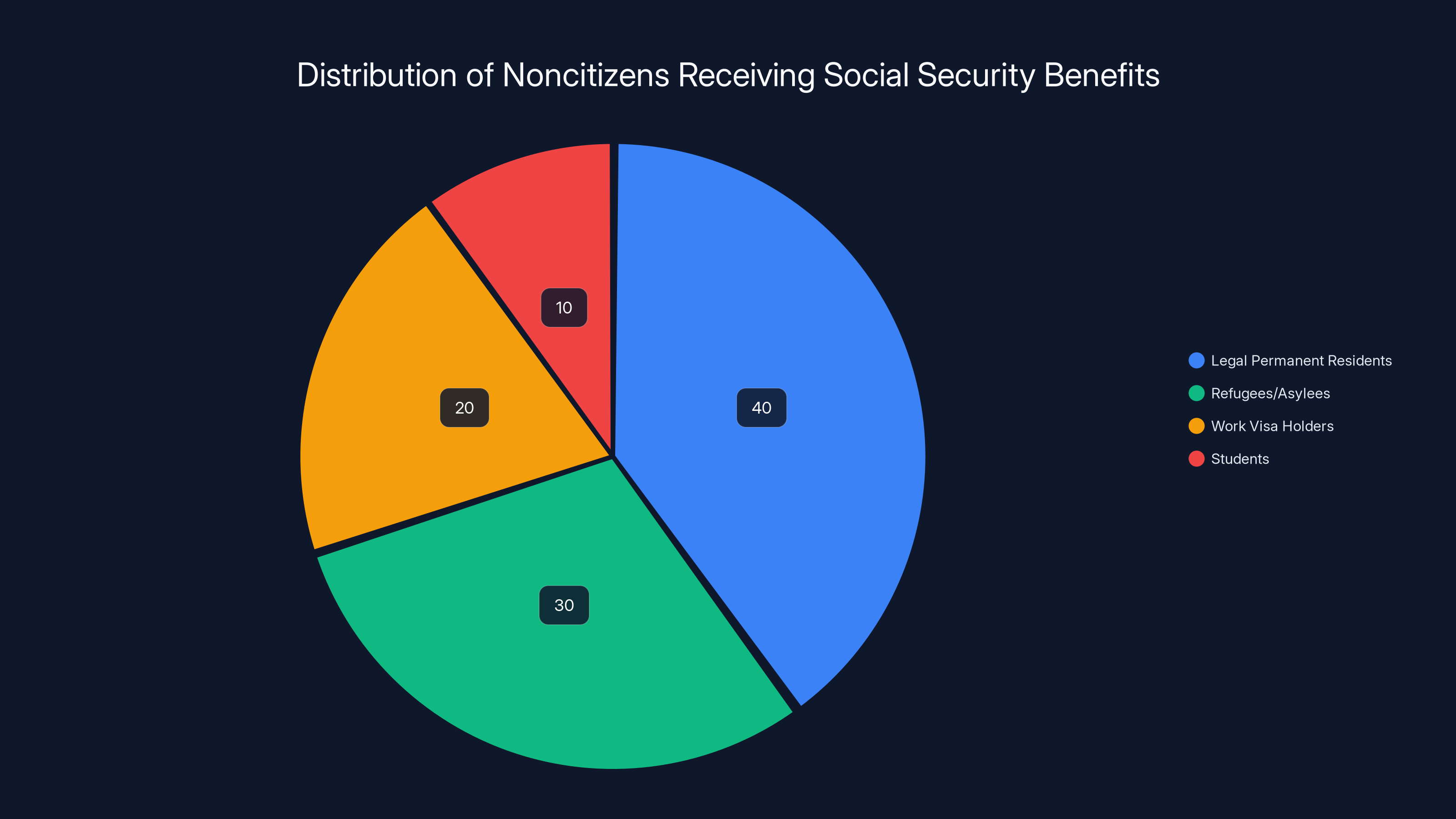

Immigrants with legal status need Social Security numbers. Students from other countries studying in the United States get Social Security numbers. People with work visas get Social Security numbers. Refugees and asylees get Social Security numbers. These aren't people breaking the law. They're people legally present in the country, working, paying taxes, contributing to communities.

When a child is a U.S. citizen but a parent is not, that parent often needs to accompany the child to SSA appointments. The parent has direct deposit accounts tied to benefits the family receives. The child might have an SSN issue that only the parent can resolve. Now that parent risks apprehension simply by going to help their citizen child.

Think about what this means in practice. A woman with legal work authorization needs to update her direct deposit because her bank changed. She has two choices: don't update it and risk missing benefits, or show up at the SSA office and risk being detained. A father is a legal permanent resident (green card holder) but is in removal proceedings for a technical immigration violation. He needs to verify his continued benefit eligibility or lose the assistance his family depends on. But he knows that walking into an SSA office might be the moment he gets arrested.

These aren't hypothetical scenarios. Immigration attorneys report that clients are already expressing this exact fear. The policy, despite being only recently announced, is already having a chilling effect.

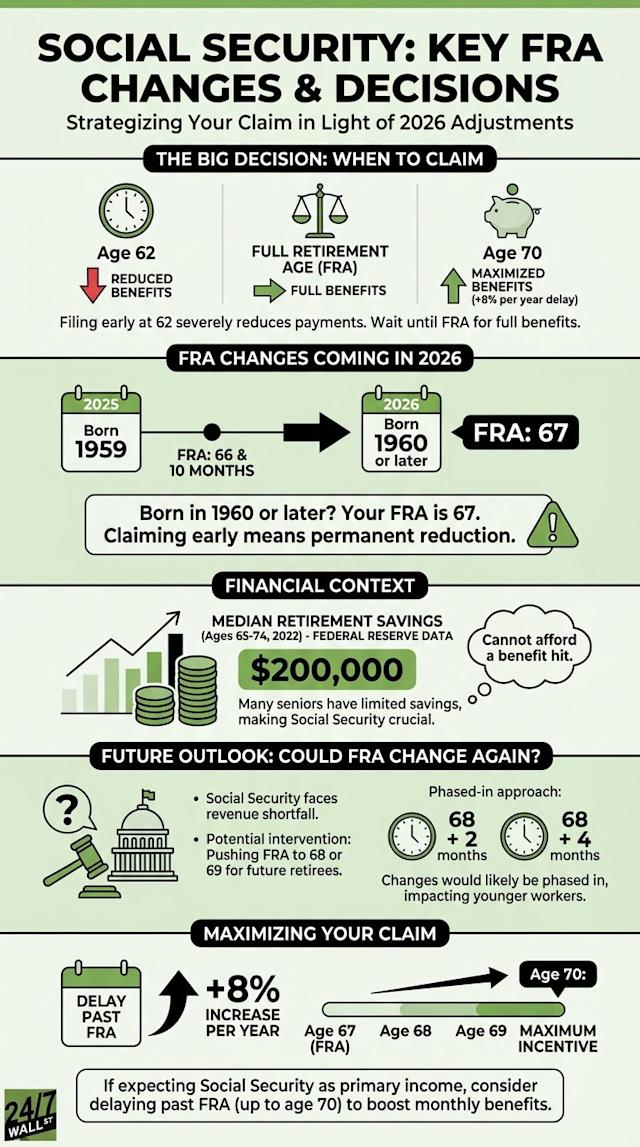

According to data from the SSA's own records, roughly 5.5 million noncitizens currently receive some form of Social Security benefits. Many of these are legal permanent residents who paid into the system while working. Many are refugees who were granted asylum. Many are people with valid work visas. All of them now face a choice: access the benefits they're entitled to, or protect themselves from potential enforcement.

The economic impact extends beyond the individuals directly affected. Families lose income. Children lose support payments. Elderly people lose retirement benefits they earned. Communities lose economic activity as people stop accessing services and limit their public presence.

Breaking Precedent: How the SSA Became Different

Historically, the SSA held a unique position in the federal government. It wasn't law enforcement. It wasn't immigration enforcement. It was a benefit-paying agency that served the public.

Leland Dudek explains that historically, the only time someone would be arrested at an SSA office was if they had threatened the agency or its staff. It happened. But it was rare. And it went through channels. The office manager would be informed. A representative from DHS would be coordinated with. There was a process. There was accountability.

Now consider the new directive. Someone's appointment is coming up. No crime has been alleged. No threat has been made. No warrant exists. But ICE calls and asks, "Does John Smith have an appointment on Thursday at 2 PM?" The answer is now yes. The information is provided. And ICE shows up.

Dudek points out the profound shift in how government works: "On multiple occasions I've had to hand over information to law enforcement, but there's a process, paperwork, multiple people signing off. This appears to tell us to ignore that policy without actually updating it. It's really worrying."

The concern isn't abstract procedural worry. It's about the difference between rule of law and arbitrary enforcement. The difference between due process and surveillance. The difference between a government that serves its people and a government that uses service as a tool for control.

Why does precedent matter? Because once you break it, rebuilding trust becomes nearly impossible. Dudek crystallizes the problem: "If a person is due a benefit, SSA is there for them and no harm will come to them. Why would the public trust SSA anymore?"

This is the actual cost of the policy. It doesn't just harm the people directly affected. It undermines the social contract underlying the entire system. It says to every noncitizen in America: government agencies that claim to help you are actually surveilling you. Your immigration status is being shared. Your location can be tracked through your benefits appointments.

That knowledge changes behavior. People stop showing up. They stop applying for benefits they're entitled to. Entire communities become invisible to government services.

The Legal Minefield: When Courts Push Back

The Trump administration's data-sharing agenda has already hit serious legal obstacles. In December 2024, a federal district judge in Massachusetts ruled that the IRS and SSA could not share taxpayer data with DHS or ICE, as covered by the Asian Law Caucus.

Judge Judith C. Fitzgerald issued an order finding that the data-sharing arrangement likely violated privacy rights and statutes that specifically protect tax return information from being shared for immigration enforcement. The ruling was narrow in scope, applying initially to the specific case, but the implications are broad.

Here's what makes this legally significant: the judge found that existing law already prohibited what the administration was trying to do. The statutes protecting tax return information from disclosure for immigration enforcement are old. They predate modern data-sharing arrangements. But they're also clear.

The ruling creates direct conflict with the SSA's new policy. If the courts determine that sharing citizenship and immigration information with DHS violates privacy laws or exceeds the SSA's statutory authority, then the appointment-sharing directive could be struck down entirely.

But there's a timing problem. The ruling applies to the specific case, not government-wide. The Trump administration could challenge it, appeal it, or simply ignore it while litigation continues. In the meantime, the directive continues. In the meantime, people continue avoiding SSA offices.

Privacy advocates are already building legal challenges. The data-sharing raises Fourth Amendment questions about unreasonable searches. It raises due process questions about using government services to facilitate enforcement. It raises statutory interpretation questions about whether the SSA has authority to share information this way.

But legal challenges take time. Precedent takes longer still. By the time courts resolve these questions, the damage might already be done.

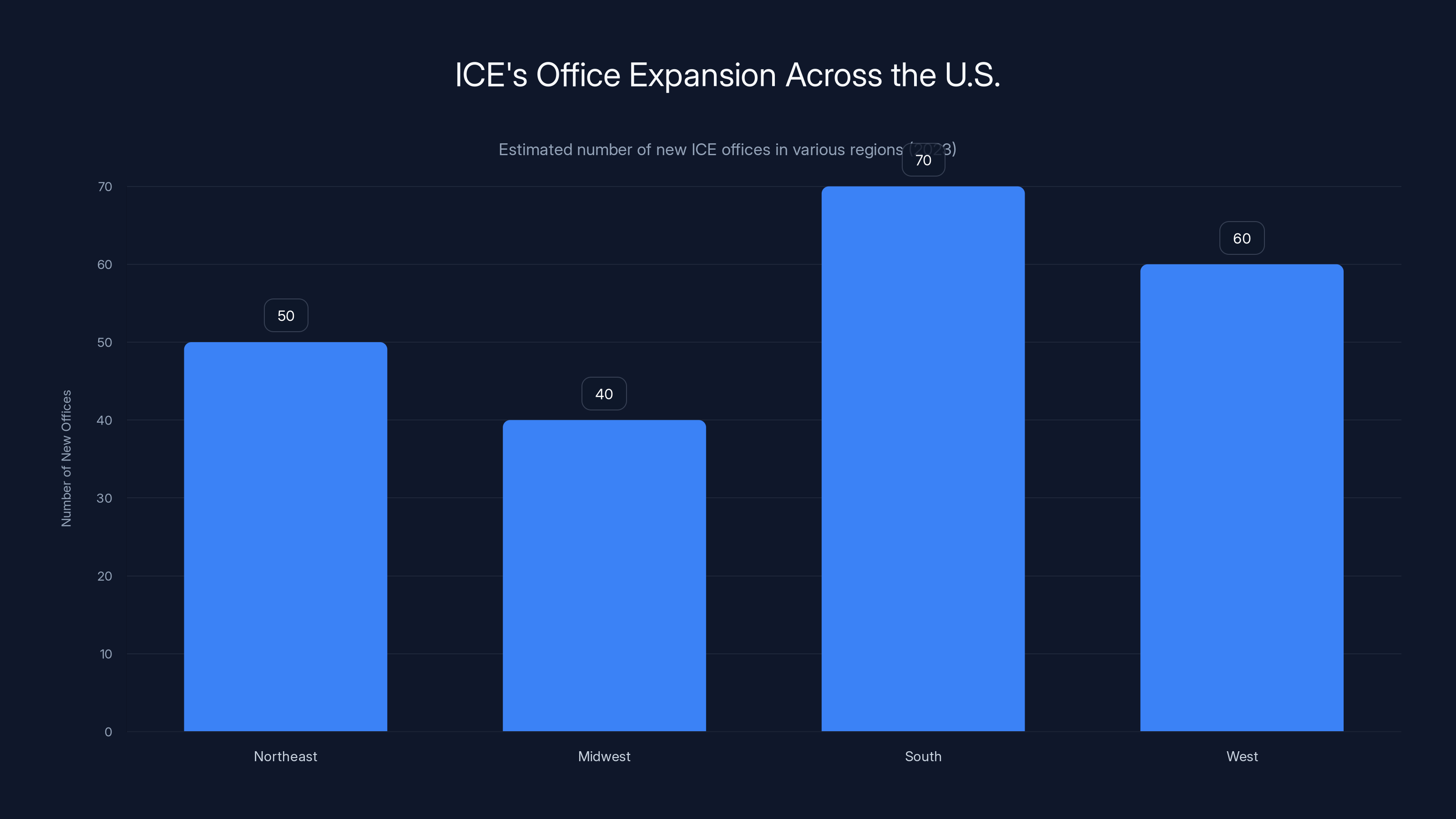

ICE is estimated to have expanded its office presence significantly across all U.S. regions, with the South seeing the highest increase. Estimated data.

The Broader Expansion: ICE's Growing Federal Footprint

The appointment-sharing directive exists within a much larger context: ICE is expanding dramatically across the United States.

Recent reporting reveals that ICE is leasing office space in cities and towns throughout the country as part of what's been described as a secret, monthslong expansion campaign. This isn't just rhetorical expansion. This is physical, infrastructure-level growth, as detailed by CNN.

Why does this matter for the SSA policy? Because it shows ICE's operational capacity and reach are growing at the exact moment the Trump administration is giving ICE access to more government databases and appointment information.

ICE currently operates with enormous authority. The agency doesn't need a warrant to conduct immigration enforcement in some circumstances. It can use administrative immigration law rather than criminal law. It operates with minimal transparency and limited judicial oversight compared to criminal law enforcement.

Now imagine that expanded ICE infrastructure combined with real-time appointment data from the SSA. Imagine ICE stations in every region, receiving appointment notifications. Imagine the agency showing up at SSA offices, knowing exactly when vulnerable populations will be present.

This isn't speculation. This is what the policy enables. This is what the directive facilitates.

The timing of ICE's expansion and the SSA's policy change suggests coordination. The administration is building enforcement capacity while simultaneously giving enforcement agencies access to the data that will make that capacity most effective.

Structural Problems: When Process Disappears

One of the most troubling aspects of the directive is how it was implemented: verbally, to selected offices, without formal policy updates.

This creates multiple structural problems. First, it avoids public notice requirements. Government agencies are generally required to give the public notice and an opportunity to comment on major policy changes. That didn't happen here. There was no Federal Register notice. No public comment period. No transparency.

Second, it creates inconsistency. Some SSA offices might receive the directive. Others might not. Some might interpret it broadly. Others narrowly. There's no uniform implementation, no official guidance, no way for people to know which offices are sharing information and which aren't.

Third, it bypasses internal approval processes. The SSA has a general counsel. The agency has a formal rule-making process. The statute creating the SSA specifies certain procedures for sharing information with outside agencies. Those procedures weren't followed here.

Dudek explains the implications: "This appears to tell us to ignore that policy without actually updating it." In other words, the directive is telling SSA workers to violate their own agency's procedures without officially changing those procedures. That creates legal risk for individual workers. It also makes it harder for courts to understand what the actual policy is, since it exists only as an unwritten verbal instruction.

This approach also prevents accountability. If something goes wrong, if someone is arrested wrongly, if information is shared inappropriately, the verbal directive structure makes it harder to trace responsibility. Nobody signed off. Nobody put it in writing. It's a ghost policy.

The Historical "Safe Space" Principle

To understand why this policy is such a radical departure, you need to understand what the SSA was designed to be.

When Congress created Social Security in 1935, it did so as a social insurance program. The idea was that workers would contribute throughout their careers, and when they retired, became disabled, or died, their families would receive benefits based on those contributions.

The SSA wasn't a law enforcement agency. It wasn't designed to exclude anyone from receiving services. It was designed to be accessible to everyone who qualified. The agency operated on the principle that if you'd paid into the system, you were entitled to benefits, period. No questions about immigration status. No requirements to verify citizenship. Just benefits based on contributions.

Over time, this evolved into an explicit principle. The SSA was meant to be a "safe space." A place where people could conduct essential business without fear of law enforcement. This principle extended not just to benefits applicants but to anyone who needed to access the agency: employees of noncitizen beneficiaries, relatives helping with paperwork, advisors assisting with complex cases.

The principle wasn't just humanitarian, though it was that. It was also practical. If people feared that entering an SSA office would trigger immigration enforcement, they wouldn't go. They'd lose access to benefits. They'd avoid paying taxes. They'd withdraw from legal status channels and move into informal or illegal economic activity.

Governments learned this lesson decades ago. When you want people to access government services, you don't scare them with law enforcement at the service location. You create safe spaces. You build trust. You separate service provision from enforcement.

Several nations have learned this lesson through hard experience. The UK's National Health Service, for example, explicitly prohibits immigration enforcement at health facilities to ensure people don't avoid medical care out of fear. Australia's safety net welfare system similarly creates barriers between benefit administration and immigration enforcement.

The principle is simple: if you mix service and enforcement, you lose both. People stop accessing services, and you get less compliance, less voluntary participation, less social cohesion.

Now the SSA is breaking that principle. It's explicitly choosing to mix service provision with enforcement. It's saying we'll use appointment information to facilitate apprehension. It's dissolving the historical firewall.

Leland Dudek, as someone who actually ran the agency, understands what this means: "This diminishes the value of what SSA is to the public." That's not nostalgia. That's professional assessment of institutional damage.

Estimated data shows that 40% of noncitizens avoid SSA offices due to the new policy, highlighting significant chilling effects on benefit access (Estimated data).

Mixed-Status Families: A Specific Crisis

One group faces particular vulnerability under this policy: mixed-status families.

A mixed-status family typically has at least one person who is a U.S. citizen and at least one person who is not. Often, the noncitizen is a parent of a citizen child. Sometimes it's a spouse. Sometimes it's both.

These families often depend on SSA services. A U.S. citizen child might receive survivor benefits because a parent died. A noncitizen parent might receive benefits based on work history. The family might have complex benefit arrangements that require in-person verification.

Now consider what the policy means for such a family. The parent knows that going to the SSA office to verify continued eligibility could result in apprehension. But without verification, benefits end. Without benefits, the family loses income. The citizen child is harmed, even though the child has done nothing wrong and is entitled to those benefits.

What choices does that parent face? Stop going to SSA appointments and lose benefits for themselves and potentially their children? Risk apprehension by showing up? Ask someone else to handle it, assuming someone else can legally do so? Try to prove continued eligibility by mail, when the law requires in-person verification?

These aren't easy choices. There's no good option. The policy creates an impossible situation that specifically targets families that include noncitizens.

Immigration attorneys who work with families are already seeing the impact. Clients are calling asking whether it's safe to go to SSA appointments. Parents are reluctant to take their children to necessary appointments because they fear apprehension. Families are avoiding a government service because they fear government enforcement.

If this is the intended outcome, it's effective policy. If it's an unintended consequence, it's a significant oversight. Either way, it's a serious problem.

Information Sharing Agreements: The Gray Areas

The SSA has formal data-sharing agreements with DHS. These agreements were made public, or at least entered into official record. They cover certain categories of information.

But here's where the existing agreements and the new directive create tension. The formal agreements likely don't specifically include "appointment dates and times for in-person office visits." That's a specific type of information that probably wasn't contemplated when the agreements were written.

Dudek explains the traditional process: information sharing with law enforcement happens on a case-by-case basis, with paperwork, with multiple people signing off. There's a record. There's accountability. It's trackable.

The new directive seems designed to bypass that process. It says: if ICE asks about an appointment, provide the information. No paperwork. No sign-offs. Just provide it. The directive is phrased to make it seem routine, almost ministerial. But it's actually a significant expansion of information sharing.

This creates a logical problem. If the information is covered by existing data-sharing agreements, why issue a new verbal directive? Why not update the formal agreements? The fact that officials chose to use a verbal directive suggests they believed the existing agreements didn't cover appointment data, and they wanted to authorize sharing anyway while avoiding the formal notice and transparency that would come with updating agreements.

This is governance through shadow policy. Real decisions being made through unofficial channels. Real changes in how government works, implemented in ways that avoid formal processes and public notice.

Technology and Surveillance: The Infrastructure Impact

The SSA shares appointment information through multiple systems. Some appointments are scheduled through phone systems. Others go through the SSA's online appointment tool. Some are managed through regional office systems.

Now imagine ICE needing to receive appointment information in real-time. What infrastructure would that require? Would the SSA create a feed to DHS systems? Would SSA employees manually provide information when asked? How would this work technically?

The answer matters because it determines the scope of surveillance and the potential for abuse. If information flows automatically to ICE systems, then ICE has real-time knowledge of SSA visitor schedules. That enables coordinated enforcement operations. If information is shared only when directly requested, it's somewhat more limited, though still problematic.

Neither approach is acceptable, but the infrastructure determines the scope of harm and the difficulty of oversight.

The SSA likely doesn't currently have the technical infrastructure to automatically push appointment data to ICE systems. That would be a separate technical project. But that project could be underway. The verbal directive might be the policy groundwork for a larger technical integration.

This connects to the broader data-pooling initiative the Trump administration launched. The goal was to create unified databases combining SSA, IRS, and DHS information. Such unified databases would require significant technical integration. They'd require building APIs and data flows between agencies.

The SSA appointment-sharing directive might be a pilot program or testing ground for that larger technical integration project.

Estimated data shows that legal permanent residents make up the largest group of noncitizens receiving Social Security benefits, followed by refugees/asylees and work visa holders. Estimated data.

The Department of Government Efficiency Connection

There's an interesting paradox in recent SSA history. The so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) previously tried to eliminate SSA phone-based services. The initiative faced massive public backlash and was rolled back.

But now, as the SSA increasingly shares appointment information with ICE and creates risk around in-person office visits, the agency will likely see reduced in-person appointment demand as people avoid offices out of fear of enforcement.

The effect might accomplish what DOGE originally intended. If people stop using SSA services because they fear enforcement, the agency's workload appears to decline. Offices might close due to reduced traffic. Services might consolidate. The agency's footprint shrinks.

This might be coincidental. But it's worth noting that different arms of the administration are making moves that, while not explicitly coordinated, push in the same direction: reduction of public access to SSA services.

International Precedent: What Other Countries Learned

Other nations have grappled with the question of mixing service provision and enforcement. Some learned hard lessons.

In the UK, the National Health Service explicitly prohibits immigration enforcement at health facilities. The principle is that people shouldn't avoid medical care out of fear of enforcement. The service provision is more important than any potential enforcement gain.

Australia's welfare system similarly separates benefit administration from immigration enforcement. The government concluded that if welfare officers could turn people in to immigration authorities, people would avoid welfare services, and the program would fail.

Canada's system explicitly protects social services from being weaponized for immigration enforcement. The principle is that social policy and immigration policy should operate in separate spheres.

These aren't sentimental policies. They're pragmatic. They're based on understanding that if government services become surveillance tools, people stop accessing them. And if people stop accessing services, the services fail and the government loses visibility into vulnerable populations.

The United States is now moving in the opposite direction. It's explicitly choosing to weaponize government services as enforcement tools. The question is whether the government understands the costs.

Chilling Effects: The Invisible Harm

Policy harms aren't always visible in arrests and enforcement actions. Sometimes the real harm is in the behavior people change to avoid harm.

When people know that accessing a government service might trigger enforcement, they change their behavior. They don't go. They don't apply. They don't seek help they need. This creates invisible but very real costs.

A noncitizen who needs to change direct deposit information might just live with using a bank that has worse terms. A legal permanent resident who qualifies for certain benefits might simply not apply. An elderly person entitled to supplemental income might skip applying to protect themselves.

These individual decisions are completely rational. They're correct risk assessments. But they aggregate into significant social costs.

Research on immigration enforcement and access to services shows clear chilling effects. When enforcement increases, service usage drops. People become more isolated. Communities withdraw from public systems.

In some cases, chilling effects extend beyond the directly threatened population. Citizen children of noncitizen parents might avoid SSA offices because they fear bringing their parents to enforcement risk. Entire families might avoid public systems.

The long-term cost of this isn't just the benefits that people don't receive. It's the loss of community connection, the increase in informal economic activity, the decline in public trust, and the social fragmentation that follows.

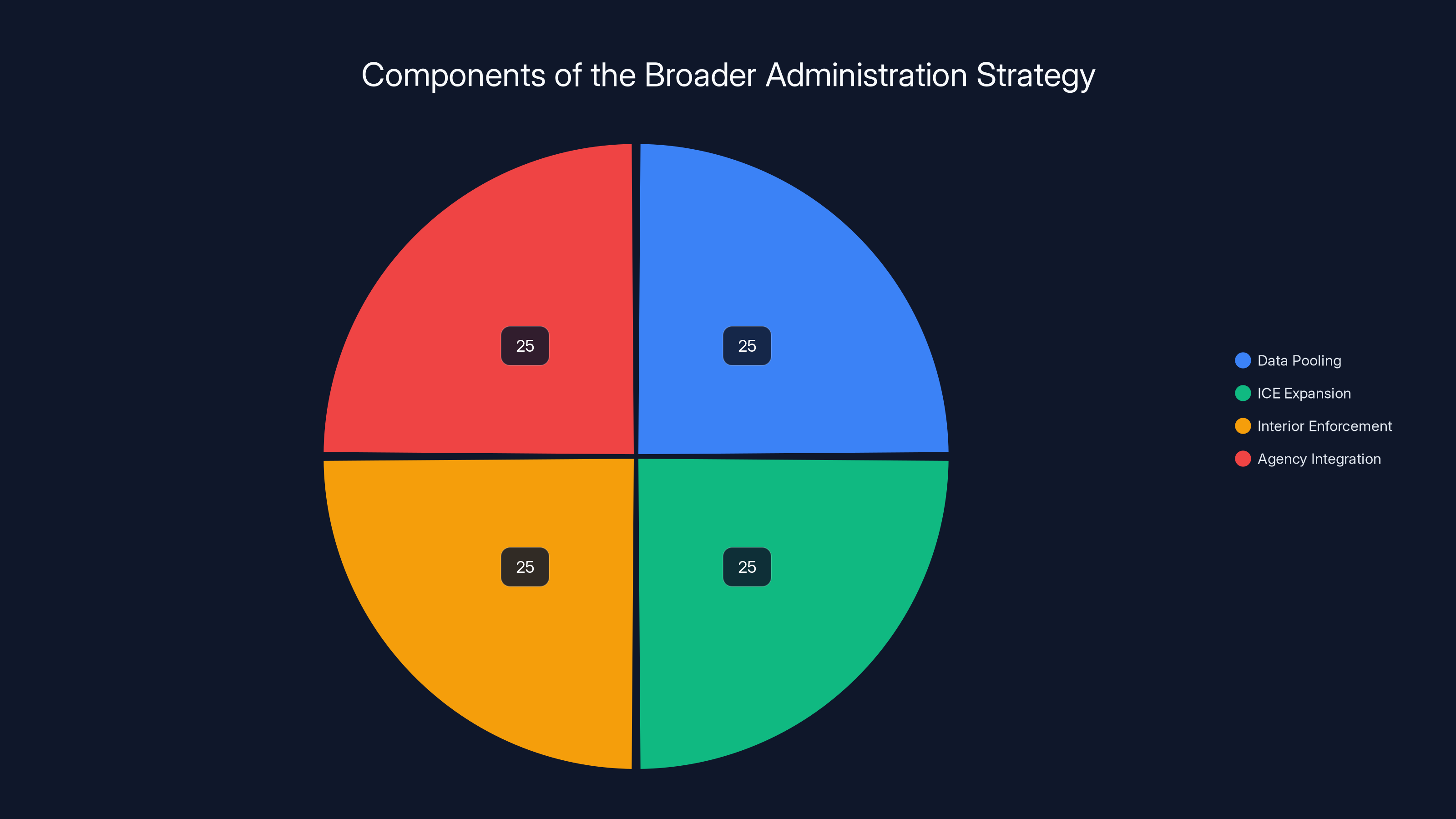

The administration's strategy equally focuses on data pooling, ICE expansion, interior enforcement, and agency integration. (Estimated data)

Rebuilding Trust After Weaponization

Once a government agency becomes an enforcement tool, rebuilding public trust becomes extraordinarily difficult.

People remember. If the SSA becomes known as a place where people get arrested, that knowledge persists. Even if the policy changes, the memory doesn't. People will avoid the agency for years, possibly decades.

This is particularly damaging for agencies like the SSA that depend on public trust and voluntary compliance. The agency doesn't force people to sign up for benefits. It doesn't force people to provide information. It depends on people coming forward voluntarily.

Once that voluntary participation breaks down, it's hard to restore. You can change policy, but you can't quickly change institutional memory.

Leland Dudek gets at this directly. "Why would the public trust SSA anymore?" That's not a rhetorical question. It's an expression of genuine concern about institutional damage that could take years to repair.

Rebuild attempts would require explicit steps: formal policy reversals, public commitments to protection, enforcement mechanisms ensuring the agency doesn't become an enforcement tool again. Even those steps might not be enough. The damage might be permanent.

The Broader Administration Strategy

The SSA policy doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader administration strategy to consolidate immigration enforcement across the federal government.

The data-pooling initiative that brought together SSA, IRS, and DHS information is one part. ICE's expansion into new offices is another part. Increased interior enforcement activities are a third part. The removal of traditional separation between service agencies and enforcement agencies is a fourth part.

The overall strategy seems designed to create a comprehensive enforcement infrastructure. Use every government agency as a potential source of information about immigration status. Use every government service location as a potential enforcement location. Create redundant systems so enforcement can happen from multiple angles.

This requires breaking down traditional barriers. It requires transforming agencies that were built as service providers into co-functioning enforcement tools. It requires convincing government employees to become part of the enforcement apparatus.

The SSA policy is one piece of that larger puzzle. It's significant not just because of what it does to the SSA, but because it demonstrates the administration's willingness to transform service agencies into enforcement agencies.

Whistleblower Concerns: Speaking Up Becomes Dangerous

SSA employees who disagree with the policy face their own risks.

The first person to tell journalists about the appointment-sharing directive spoke on condition of anonymity for "fear of retaliation." That's a significant phrase. A federal employee felt they couldn't speak openly about a policy change without risking their job.

That fear is probably justified. The Trump administration has explicitly criticized federal employees who leak or speak to media. There's been discussion of retaliation against bureaucrats seen as part of the "deep state." In that environment, an SSA employee who objects to a policy and speaks to media is taking real risk.

This creates a secondary problem. Employees know the policy exists. They know it's problematic. But they can't speak about it safely. The policy operates in a space where people can't effectively object or challenge it through normal channels.

This is part of why the verbal directive approach is so effective as a governance tool. It operates below the threshold where it can be easily challenged. It avoids formal records that could be challenged in court. And it uses fear of retaliation to prevent employee objections.

For a democratic society that depends on government transparency and accountability, this is deeply problematic. It means policies operate without proper oversight. It means the public doesn't know what's happening in government agencies. It means employees who might object can't do so safely.

Legal Pathways Forward: Potential Challenges

The appointment-sharing policy could be challenged through multiple legal routes. Some of those routes might work. Others might not.

First, there's the statutory question. Does the SSA have legal authority under the Social Security Act to share appointment information this way? That's a serious legal question. Congress specified what information the SSA can share, and with whom, and under what circumstances. Sharing appointment data might exceed that authority.

Second, there's the Fourth Amendment angle. Does sharing appointment information with ICE in a way that enables enforcement without a warrant violate Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches? That's a more complex question, but there's potential there.

Third, there's the Administrative Procedure Act angle. Did the SSA follow required procedures in implementing this policy? If the answer is no, the policy might be overturned on procedural grounds even if it might be permissible if done correctly.

Fourth, there's the equal protection angle. Does the policy discriminate against noncitizens in a way that violates equal protection principles? That depends on how courts interpret constitutional protections for noncitizens.

Fifth, there's the privacy statute angle. The ruling against the IRS and SSA data-sharing suggests there might be privacy statutes that protect against this kind of sharing. Those statutes could apply here.

The challenge is that litigation takes time. By the time cases work their way through courts, the policy has already changed behavior. People have already avoided SSA offices. Benefits have already gone unclaimed. The damage is already done.

The Role of Technology Companies and Data Brokers

One often-overlooked aspect of government data-sharing is how technology companies and data brokers interact with the process.

When government agencies share data, they often do so through technology systems. Companies like Palantir have explicitly defended their work helping ICE access and organize data. Other tech companies have provided infrastructure for government databases.

The appointment-sharing system might not exist yet, but if it does get implemented technically, it would require infrastructure. Who builds that? What access do those companies have? What happens to the data?

Palantir, in particular, has been open about its work with ICE. The company has argued that its technology is necessary for immigration enforcement. But that transparency also highlights how technology companies enable government surveillance.

As the SSA potentially develops technical systems to share appointment data, those systems will likely involve technology companies. The capabilities those companies build for government often later get used in ways that weren't originally planned.

This is worth monitoring. Technology implementation decisions can be even more consequential than policy decisions because they're harder to reverse.

The Intersection with IRS Data Sharing

The ruling against IRS and SSA data-sharing with DHS creates interesting legal dynamics.

The judge found that the agencies couldn't share the data in the way they were planning. But that ruling applies to that specific case. It doesn't automatically stop the SSA from sharing appointment data with ICE, though it might suggest the judge would find similar problems with that arrangement.

The SSA is now in an interesting legal position. It's being told it can't share certain categories of data, but it's simultaneously operating a policy to share different categories of data (appointment information) with the same agency (ICE, part of DHS).

This could actually be a vulnerability. If legal challenges to the IRS ruling establish precedent about SSA data-sharing limitations, that precedent might apply to the appointment-sharing policy too.

On the other hand, the administration might argue that appointment information is different from tax data or citizenship records. It's arguably less sensitive. That distinction might matter in court, or it might not.

The law in this area is currently in flux. Courts are still figuring out what exactly the limits are on government data-sharing for immigration enforcement.

Practical Guidance: What People Should Know

For anyone concerned about this policy, there are some practical steps to consider.

First, understand that this is a real policy affecting real people. Don't assume you're not affected because you're a citizen. If you're working with noncitizens, have relatives who are noncitizens, or care about civil liberties generally, you're affected.

Second, understand your options before you need them. If you need SSA services, research whether your specific office is implementing the policy. Ask directly. Request phone or virtual appointments if possible. Use representatives who might be able to handle some issues on your behalf.

Third, document any concerning interactions. If you're refused in-person appointment options, document that. If you're told about data-sharing, document that.

Fourth, consider supporting organizations fighting these policies. Civil rights organizations are already mobilizing. They need support.

Fifth, talk to people about this. The policy depends on silence. Public awareness creates pressure for change.

Looking Forward: What Happens Next

The SSA appointment-sharing policy is still in early stages. How it develops will depend on multiple factors: legal challenges, public pressure, internal resistance from SSA employees, and political changes.

In the short term, expect the policy to cause exactly what it's already causing: reduced in-person appointments as people avoid SSA offices, decreased services to noncitizens, and increased apprehensions at or near SSA offices.

In the medium term, expect legal challenges. Civil rights organizations are already preparing lawsuits. The question is whether those suits will succeed and how quickly.

In the longer term, expect either reversal or expansion. If the policy faces strong legal and public pushback, it might be reversed. If it doesn't face enough resistance, it could expand to other agencies.

The policy also creates incentives for technological integration. Once you've decided to share appointment data with ICE, why not create systems to do it automatically? Why not expand to other agencies? Why not create unified enforcement databases?

That's where the real danger lies. The appointment-sharing directive is just the beginning of what could become a comprehensive surveillance and enforcement infrastructure.

Conclusion: Democracy Requires Boundaries

Democratic societies function because government services exist in one sphere and government enforcement in another. You can access services without fearing enforcement. You can come forward without risking apprehension.

The Social Security Administration appointment-sharing policy tears down that boundary. It explicitly weaponizes access to government services as an enforcement mechanism.

This matters not because anyone thinks ICE enforcement is inherently wrong. People disagree about immigration policy. That's legitimate democratic debate.

But how you enforce immigration law matters. Do you enforce it through authorized channels with due process and oversight? Or do you use every government agency as an enforcement tool, mixing service provision with enforcement, creating fear around basic government access?

The SSA policy chooses the second approach. It transforms a service agency into an enforcement tool. It uses the promise of benefits as a lure to bring people to enforcement locations. It breaks down the historical firewall that protected people seeking government services.

Once you do that, you break something fundamental about how government works. You erode trust. You change the relationship between people and institutions. You create fear where there should be security.

Leland Dudek was right to be concerned. The SSA is becoming "an extension of Homeland Security." And once that happens, the agency stops being a social insurance program and starts being an enforcement apparatus.

The real question isn't whether this policy will work. It probably will, in the sense that it will enable some immigration enforcement. The question is what we lose by doing it. What happens when government agencies stop being places people can safely access services? What happens when immigrants stop reporting crimes because they fear apprehension? What happens when citizen children lose access to benefits because noncitizen parents are afraid?

These consequences might not matter to people focused solely on enforcement outcomes. But they should matter to anyone who thinks government should serve all people equally, treat people fairly, and operate within legal and constitutional boundaries.

The SSA appointment-sharing policy fails on all those measures. It's worth fighting.

FAQ

What is the Social Security Administration's appointment-sharing policy with ICE?

The SSA has implemented a verbal directive instructing employees to share information about in-person appointment dates and times with Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents when asked. This policy breaks from decades of precedent where the SSA operated as a "safe space" where people could access services regardless of immigration status. When ICE inquires whether someone has an upcoming appointment, SSA staff are now told to provide the specific date and time of that appointment.

Who is affected by this policy?

The policy primarily affects noncitizens including legal permanent residents, visa holders, refugees, asylees, and people with work authorization. However, it also impacts U.S. citizens in mixed-status families who need to accompany noncitizen relatives to SSA appointments, as well as citizen children of noncitizen parents who may avoid offices out of fear. Anyone seeking SSA services could potentially be affected if they're perceived as potentially undocumented or if they're associated with someone who is.

How does this policy conflict with existing law?

A federal judge in Massachusetts ruled in December 2024 that the IRS and SSA could not share taxpayer data with DHS or ICE, finding the practice likely violated privacy rights and statutes protecting tax information from immigration enforcement use. The Social Security Act also specifies what categories of information the SSA can share and with which agencies, potentially making the appointment-sharing directive exceed the agency's legal authority. Additionally, the policy appears to circumvent administrative procedures required by the Administrative Procedure Act.

Why is this policy considered a break from historical practice?

Historically, the SSA operated under the principle that it was a "safe space" where people could access services without fear of law enforcement. Information sharing with law enforcement followed formal processes with paperwork, multiple approvals, and case-by-case review. The current directive bypasses these procedures by being implemented verbally without formal policy updates, creating an unwritten policy that avoids transparency and accountability mechanisms.

What are the practical consequences of this policy?

People are already avoiding SSA offices due to fear of apprehension, causing them to miss appointments necessary to verify benefit eligibility. Mixed-status families face impossible choices between accessing needed services and protecting themselves from enforcement. Benefits go unclaimed, family income decreases, and citizen children are harmed when parents avoid required in-person appointments. The chilling effect extends beyond direct enforcement to changed behavior in accessing essential services.

What legal challenges might this policy face?

Potential challenges include statutory authority questions under the Social Security Act, Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches, Administrative Procedure Act violations for failure to follow notice and comment procedures, equal protection concerns about discrimination against noncitizens, and privacy statute violations. The recent Massachusetts ruling against IRS and SSA data-sharing suggests courts may be receptive to challenges against expanded information sharing for immigration enforcement purposes.

How does this fit into the broader Trump administration strategy?

The appointment-sharing policy is one element of a larger data-consolidation initiative designed to create comprehensive immigration enforcement infrastructure. This includes pooling data from the SSA, IRS, and DHS, expanding ICE's physical presence through new office leasing, and transforming service agencies into co-functioning enforcement tools. The strategy attempts to create multiple enforcement access points across government rather than limiting enforcement to traditional immigration channels.

What can individuals do if they need SSA services?

People should research whether their specific SSA office is implementing the policy, request phone-based or virtual appointments when possible, consider using representatives to handle some issues on their behalf, and document any concerning interactions. Those with concerns should contact civil rights organizations fighting the policy, as litigation is already being prepared. Speaking publicly and supporting organizations challenging the directive also creates pressure for policy reversal.

Why does separating service provision from enforcement matter?

When government services are weaponized for enforcement, people stop accessing them. This creates invisible but significant costs: foregone benefits, lost income for vulnerable families, reduced visibility into populations that need services, and decreased trust in government institutions. International examples from the UK, Canada, and Australia show that countries that explicitly separate service provision from immigration enforcement maintain higher service usage and better policy outcomes overall.

What historical precedent exists for this kind of policy separation?

The Social Security Act itself, created in 1935, was explicitly designed as a social insurance program separate from law enforcement. Tax return information has been federally protected from immigration enforcement use since 1976, when Congress specifically prohibited the IRS from sharing tax data with immigration authorities precisely to prevent mixing service and enforcement. These precedents reflect decades of understanding that mixing these functions undermines both.

Key Takeaways

- The SSA is now sharing appointment details with ICE, breaking 90 years of historical precedent where the agency operated as a safe space for service access regardless of immigration status

- The policy was implemented through verbal directives without formal rule changes, avoiding transparency, public notice, and accountability mechanisms

- Mixed-status families face impossible choices between accessing entitled benefits and protecting themselves from enforcement at government service locations

- A federal judge has already ruled that similar SSA and IRS data-sharing with immigration authorities likely violates privacy laws and statutory protections

- Chilling effects are already visible as noncitizens avoid SSA offices, foregoing benefits and creating secondary harm to citizen family members

- The policy represents part of a broader administration strategy to consolidate immigration enforcement across federal agencies and transform service agencies into enforcement tools

- Legal challenges are likely but face a timing problem: policy changes behavior immediately while legal resolution takes years

- International precedent from other democracies shows that separating service provision from enforcement is essential for maintaining trust and policy effectiveness

- Once government agencies become known as enforcement locations, rebuilding public trust takes decades even if policy reverses

- The policy has implications far beyond the SSA, potentially serving as a model for other agencies to follow similar enforcement-integration patterns

Related Articles

- ICE Expansion and Government Transparency: What Communities Need to Know [2025]

- CBP's Clearview AI Deal: What Facial Recognition at the Border Means [2025]

- iRobot's Chinese Acquisition: How Roomba Data Stays in the US [2025]

- Government Censorship of ICE Critics: How Tech Platforms Enable Suppression [2025]

- ExpressVPN ISO Certifications & Data Security [2025]

- AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance [2025]

![Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/social-security-data-handover-to-ice-a-dangerous-precedent-2/image-1-1771015143483.jpg)