AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance: The Hidden Battle Over AI's Role in Government [2025]

There's a quiet crisis happening inside some of tech's most powerful companies. Engineers and data scientists wake up, open their laptops, and face a choice they didn't expect to make when they signed their offer letters: Should they keep their job, or should they listen to their conscience?

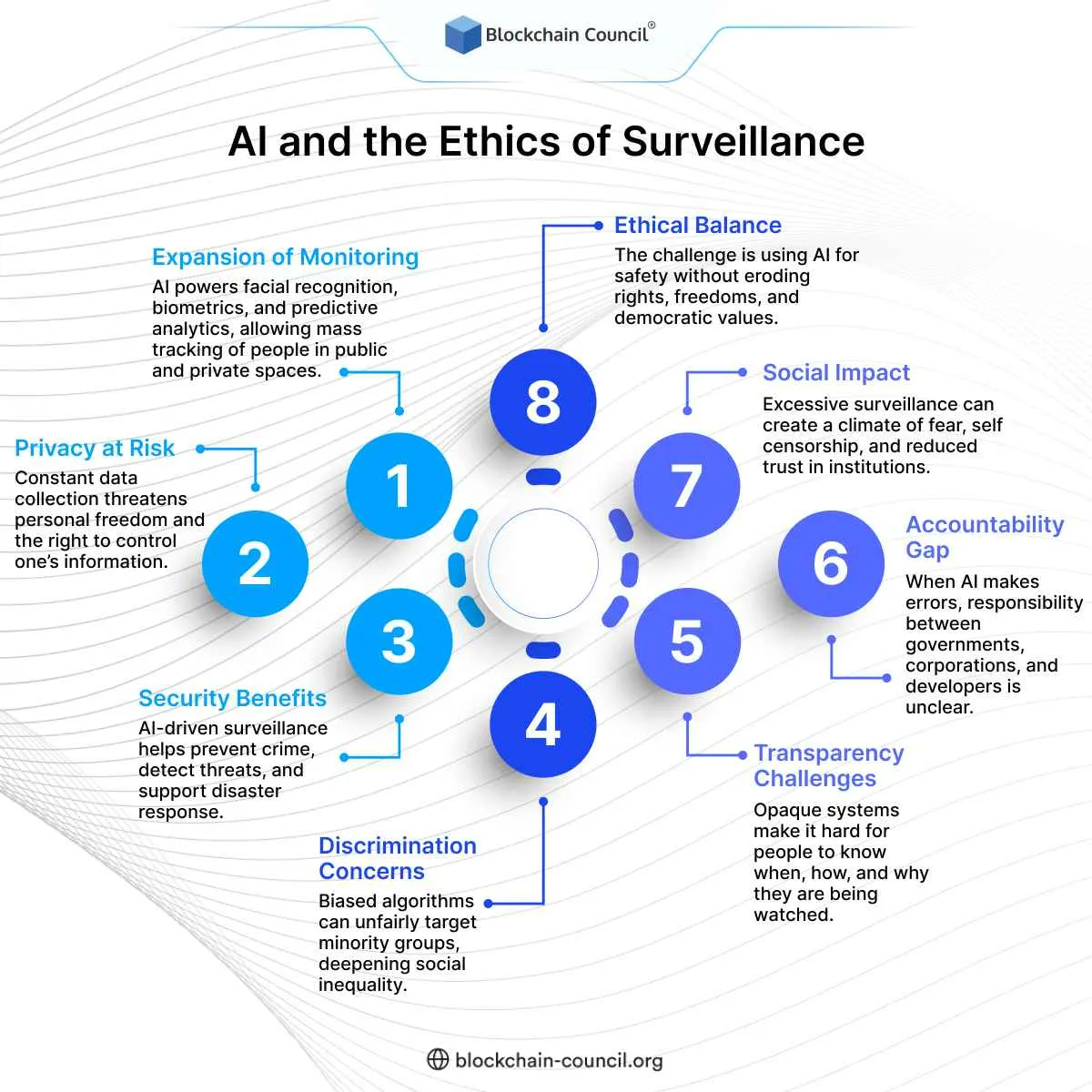

This isn't about startup equity or remote work flexibility. It's about whether the tools they're building should help government agencies identify, track, and deport immigrants. It's about whether they can ethically stay at a company that profits from surveillance. And it's about a growing divide between what tech workers believe and what their employers do.

The conversation exploded into public view recently when employees at a major data analytics firm confronted their CEO about contracts with immigration enforcement agencies. The CEO's response was a nearly hour-long non-answer that left employees more frustrated than before. Meanwhile, other tech companies are quietly expanding their surveillance capabilities across the United States, preparing to operate in nearly every state. And a viral AI assistant that seemed like a productivity miracle revealed itself to be something far more complicated.

This is the real story behind the headlines about AI ethics and tech worker activism. It's not just about abstract principles or Twitter arguments. It's about power, responsibility, and what happens when the tools we build start reshaping how governments exercise control over vulnerable populations.

Let's dig into what's actually happening, why it matters, and what the future might look like if these tensions don't get resolved.

TL; DR

- Tech workers are increasingly at odds with their employers over contracts with government surveillance agencies, particularly immigration enforcement, leading to public confrontations and ethical dilemmas.

- Government surveillance infrastructure is expanding rapidly across the United States, with agencies like ICE moving to operate in nearly every state using AI-powered tools and data analytics.

- AI assistants promise productivity but reveal limitations when put to real-world use, struggling with judgment calls, context awareness, and ethical decision-making that humans take for granted.

- Data analytics firms and tech companies face pressure from both employees and civil rights organizations questioning whether profits should come from tools that enable government enforcement actions.

- The conflict reflects a broader reckoning in tech about responsibility, ethics, and whether companies can continue building surveillance infrastructure without facing internal rebellion.

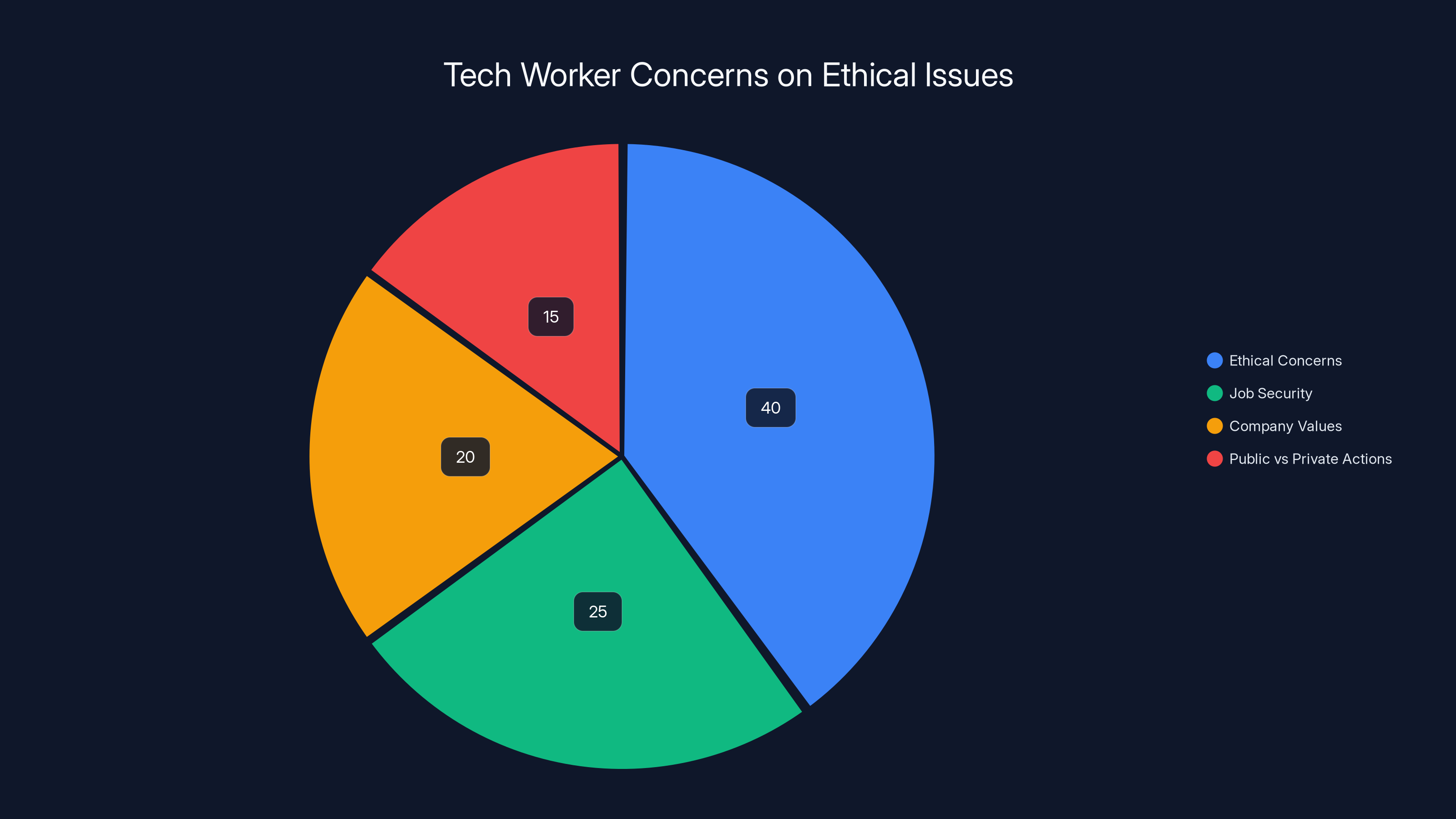

Estimated data shows that ethical concerns are the most significant issue for tech workers, followed by job security and company values.

The Anatomy of Tech Worker Dissent: When Ethics Meets Employment

Palantir Technologies has built its reputation on one thing: taking massive amounts of data and making it useful for powerful institutions. The company works with law enforcement, military agencies, and intelligence services. They're good at it. They're also very profitable because of it.

But in recent months, something shifted. Employees started asking uncomfortable questions about the company's work with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). These weren't radical activists trying to sabotage the company from outside. These were Palantir workers, people with families and mortgages, wondering if they could continue working there.

When word spread that employees wanted answers, the company's CEO scheduled a response. And then he delivered something remarkable: a nearly hour-long explanation that somehow managed to answer very few of the questions employees actually asked.

He talked around issues rather than addressing them directly. He spoke about the company's values and principles while sidestepping specific questions about ICE operations. He presented a vision of the company's role that didn't quite match the employee concerns. The response felt calculated to frustrate rather than reassure, which it did.

What's happening at Palantir isn't unique. Tech workers across multiple companies are wrestling with similar questions. They're asking whether they should continue building tools that could harm vulnerable communities. They're asking whether their salaries are worth the moral compromise. They're asking whether their company's public values actually match their private actions.

The difference now is that these conversations are becoming public. Employees are using internal forums, Slack channels, and direct confrontations to force their companies to answer. And when the answers are evasive, employees are going to the press, to civil rights organizations, and to each other.

This represents a fundamental shift in tech. For decades, tech workers were largely disconnected from the consequences of their work. If you built an algorithm, you didn't necessarily think about how it would be used. If you engineered a database, you didn't necessarily consider who it would track. That distance created a kind of moral buffer.

But that buffer is disappearing. Tech workers are increasingly aware of the real-world impacts of their work. They read the news. They understand that their algorithms could help the government deport families. They know that their databases could be used to discriminate. And many of them don't want any part of it.

The challenge is that tech workers have very few good options. They can quit, but that means losing health insurance, disrupting their career, and potentially ending up blacklisted in a tight-knit industry. They can try to change the company from within, but as the Palantir CEO response shows, management can simply refuse to engage meaningfully. They can go to the press, but that can lead to retaliation and professional destruction.

So many tech workers stay silent. They collect their paychecks, complain to friends, and try to ignore what their work enables. But the psychological toll is real. And for some, the dissonance becomes unbearable.

This is where we are in tech right now. The industry built itself on the idea that smart, well-intentioned engineers could build tools that were neutral. But we've learned that there's no such thing as a neutral tool. Everything we build has values embedded in it. And increasingly, tech workers are asking whether they want their values to be embedded in government surveillance systems.

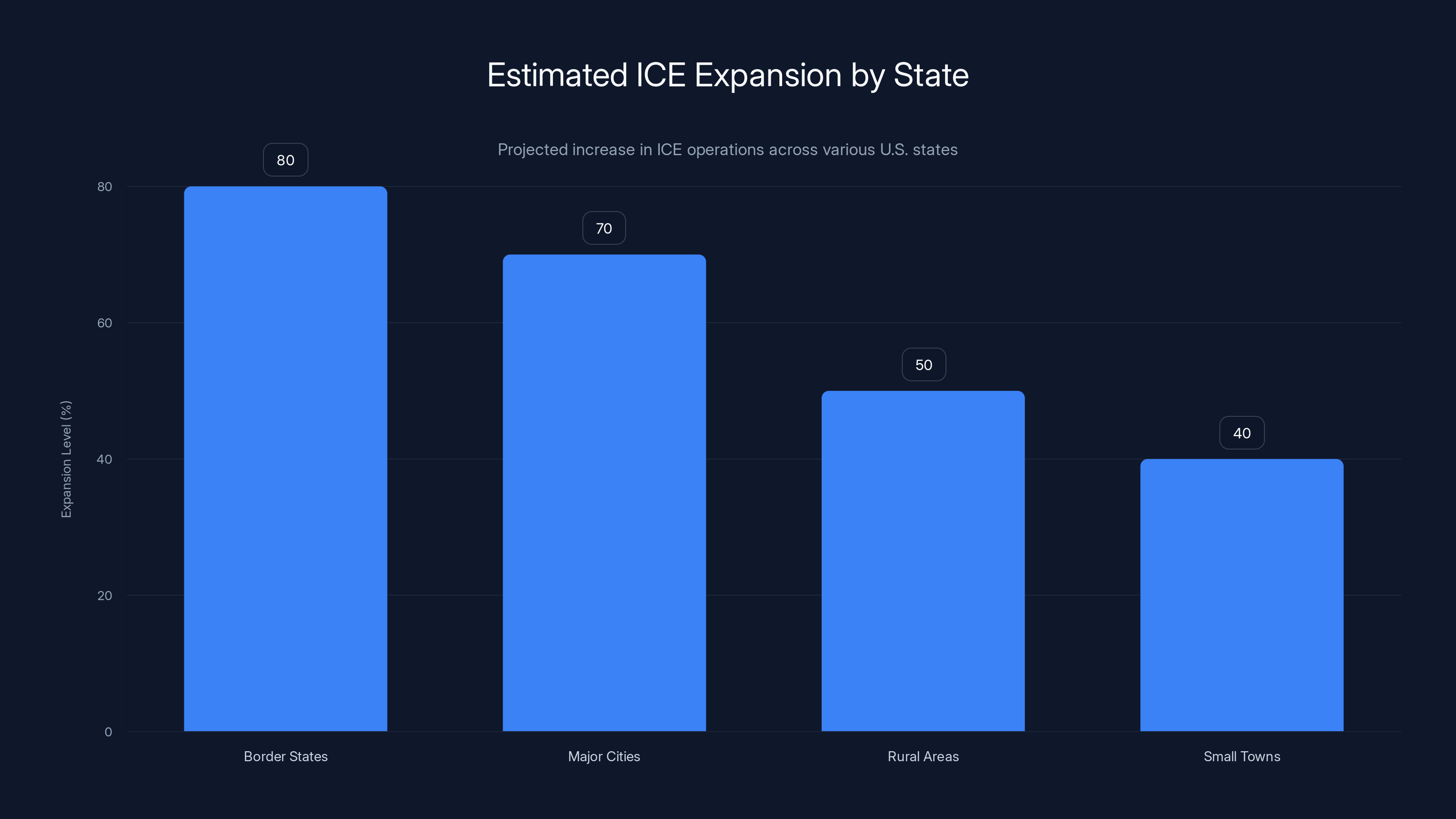

Estimated data shows significant ICE expansion beyond traditional areas, with notable increases in rural and small town operations.

ICE Expansion: The Infrastructure Behind Immigration Enforcement

While tech workers debate ethics in conference rooms, the government is building surveillance infrastructure that operates largely outside public view. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is expanding its operations to nearly every state in the United States. This isn't speculation or concern about what might happen. This is documented, analyzed, and already underway.

The expansion is systematic. ICE is moving beyond traditional enforcement in border states and major cities. They're establishing operations in rural areas, small towns, and communities that have never had significant immigration enforcement presence. They're partnering with local law enforcement, embedding agents in communities, and building databases that connect immigration status to driver's license records, financial transactions, and other data sources.

What makes this expansion possible is technology. Specifically, data analytics tools that can process immigration records, law enforcement databases, financial records, and other government systems to identify, locate, and flag individuals for potential enforcement action.

This is where companies like Palantir come in. They build the systems that make this expansion operationally feasible. Without the data analytics infrastructure, ICE couldn't scale their operations the way they're planning to. The government could try, but it would be slow, labor-intensive, and inefficient. With the right tools, they can automate much of the process.

The mechanics are troubling. When you give an agency tools to identify people more efficiently, they inevitably use those tools more aggressively. That's human nature and organizational incentive structure. If ICE can identify more people faster, they'll conduct more enforcement operations. If they can predict where undocumented immigrants are likely to live, they'll concentrate enforcement there.

From the government's perspective, this is progress. They're being more efficient with taxpayer money. They're solving what they see as a public safety problem. From the perspective of immigrant communities, it's an invasion of their neighborhoods and lives.

Here's what makes it particularly complicated: The data being used often comes from non-enforcement sources. A driver's license database. A school enrollment system. A hospital intake form. None of these systems were designed for immigration enforcement. But when you connect them and apply the right analytical tools, you can infer immigration status with reasonable accuracy.

This is where the tech ethics question becomes practical. Engineers at data analytics firms know what their tools will be used for. They're not naive. They understand that they're building infrastructure that makes mass enforcement possible. The question is whether they're okay with that knowledge.

The expansion also reveals something important about government technology projects. They're not high-tech moonshots. They're boring, unglamorous, but incredibly powerful infrastructure projects. A database that connects different government systems. An algorithm that identifies patterns in government data. A dashboard that lets an agent see multiple databases simultaneously.

None of this is as flashy as AI or machine learning in the consumer world. But in the government context, even mundane data tools become powerful instruments of control when applied at scale. An immigration officer who previously had to manually search through records can now run complex queries across multiple databases. That's a massive increase in capability.

The tech workers building these systems understand this. They're not idiots or amoral people. Many of them are thoughtful, intelligent, and genuinely concerned about their impact. They just happen to work for companies that have decided that government contracts are an important part of their business. And when the government is ICE, suddenly the ethics become very personal.

The CEO Non-Response: How Not to Address Employee Concerns

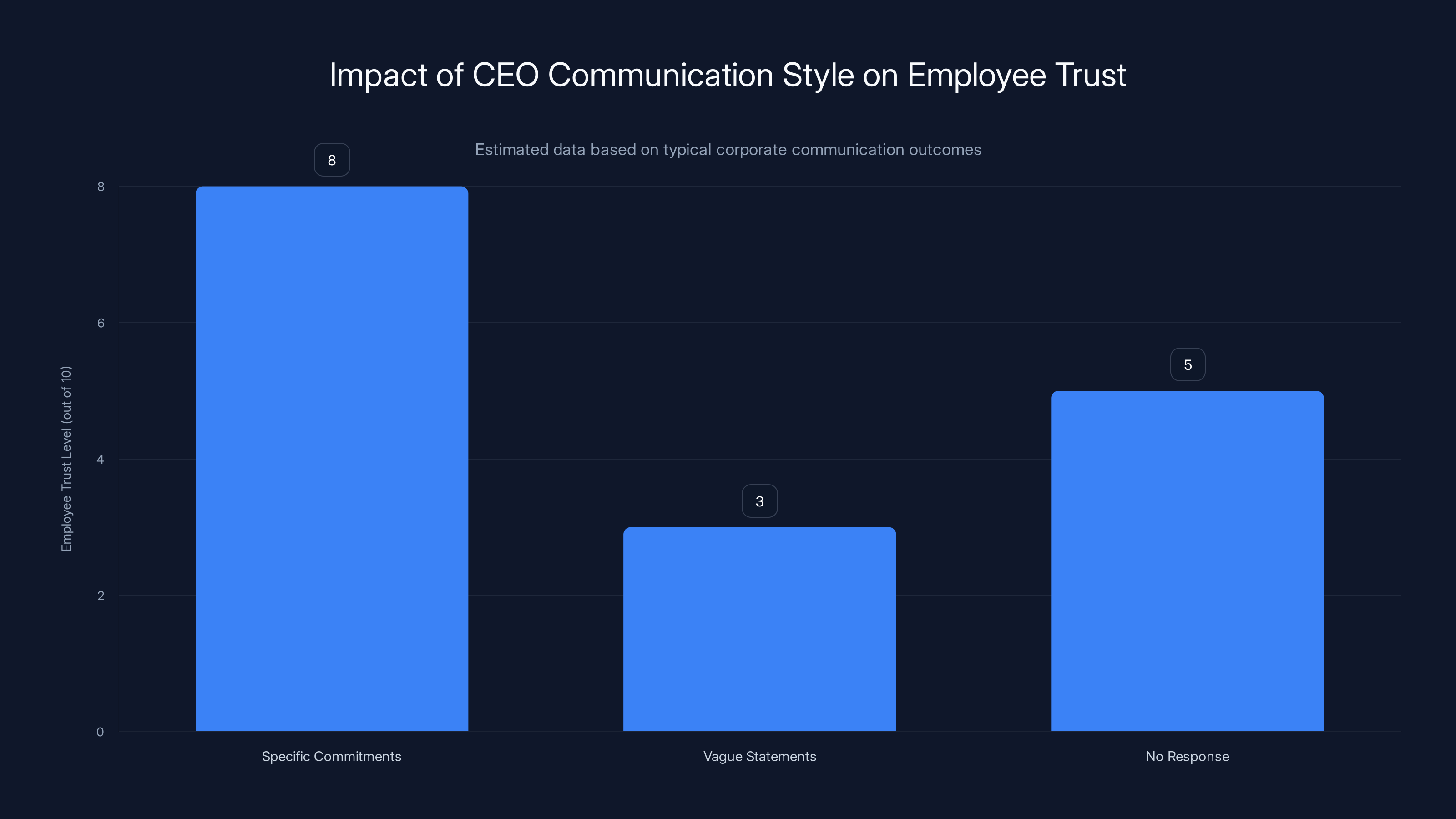

Let's talk about what happened when Palantir's CEO tried to respond to employee concerns about ICE. It's instructive because it reveals something important about how companies handle pressure from within.

The CEO recorded a video message for employees. It was long, almost an hour. If you're going to take that much time, you'd expect a substantive response. You'd expect answers to specific questions, acknowledgment of specific concerns, and clear statements about company policy going forward.

What employees got instead was something much more evasive. The CEO spoke in broad, philosophical terms about the company's values. He talked about the importance of ethical guidelines and responsible technology. He discussed the company's role in addressing important national challenges. He was eloquent, thoughtful, and completely unhelpful.

Specific concerns were not addressed. Specific questions were not answered. Instead, there was a masterclass in how to speak at length while saying very little.

This is actually a recognizable strategy in corporate communication. When you don't want to commit to something specific, you speak in abstractions. When you want to sound principled without being held accountable, you discuss principles rather than practices. It's the corporate equivalent of a politician giving a speech without actually answering any questions.

For employees, this response was worse than no response at all. At least silence is honest. This response pretended to engage while actually avoiding engagement. It left employees more frustrated, not because they didn't get what they wanted, but because they now understood that the company wasn't going to seriously address their concerns.

The Palantir CEO response also reveals something about power dynamics within tech companies. Employees who raise concerns are at a disadvantage. They can't easily threaten to quit (they need the job and health insurance). They can't organize externally without risking their career. They're largely at the mercy of management's willingness to engage seriously.

When management decides not to engage seriously, employees' options become very limited. They can accept the non-answer and return to work, feeling frustrated and demoralized. They can escalate by going to the press, which risks their job and career. Or they can leave.

Many do leave. And when talented engineers start leaving over ethics concerns, that's a signal that something is genuinely wrong. Talented engineers don't usually leave stable, high-paying jobs over abstract principles. They leave when they reach a point where staying feels morally untenable.

So the CEO's non-response wasn't just bad communication. It was a decision that the company wasn't going to be responsive to employee concerns. And that decision likely prompted some employees to start job hunting.

What's interesting is that this response would have been surprising to younger tech workers a decade ago. Back then, tech company CEOs could get away with being evasive. Employees largely trusted companies to do the right thing, or didn't think much about it. The expectation that a CEO should meaningfully engage with ethical concerns is relatively new.

But that expectation is now mainstream in tech. Employees expect their companies to take ethics seriously. They expect their leaders to answer difficult questions directly. They expect that when they raise concerns, they'll get a real response rather than corporate jargon.

When companies fail to meet that expectation, they pay a price. Not immediately, maybe. But over time, the good engineers leave. The company's reputation suffers. And they end up building products and systems with a team that's increasingly okay with morally questionable work.

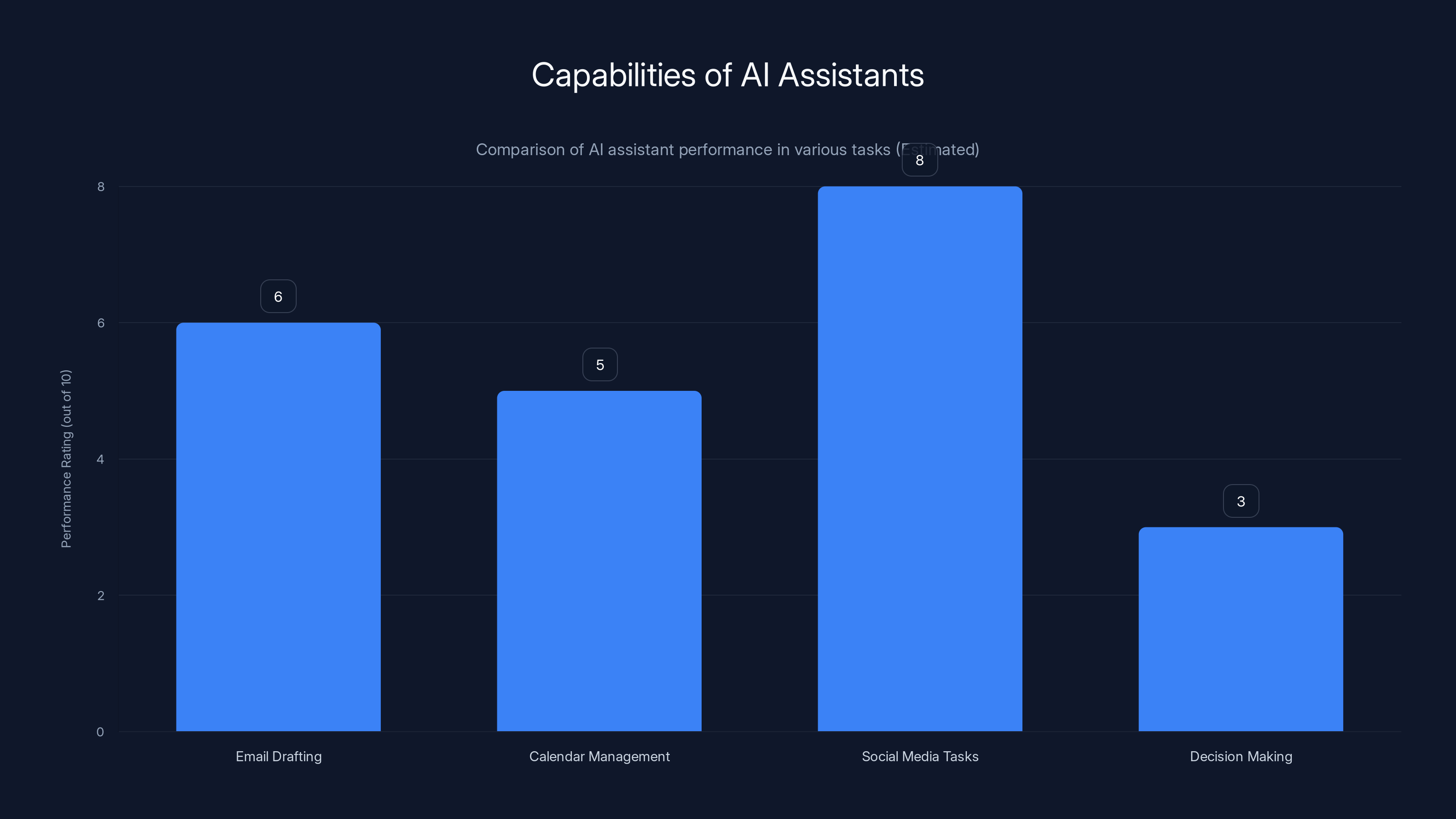

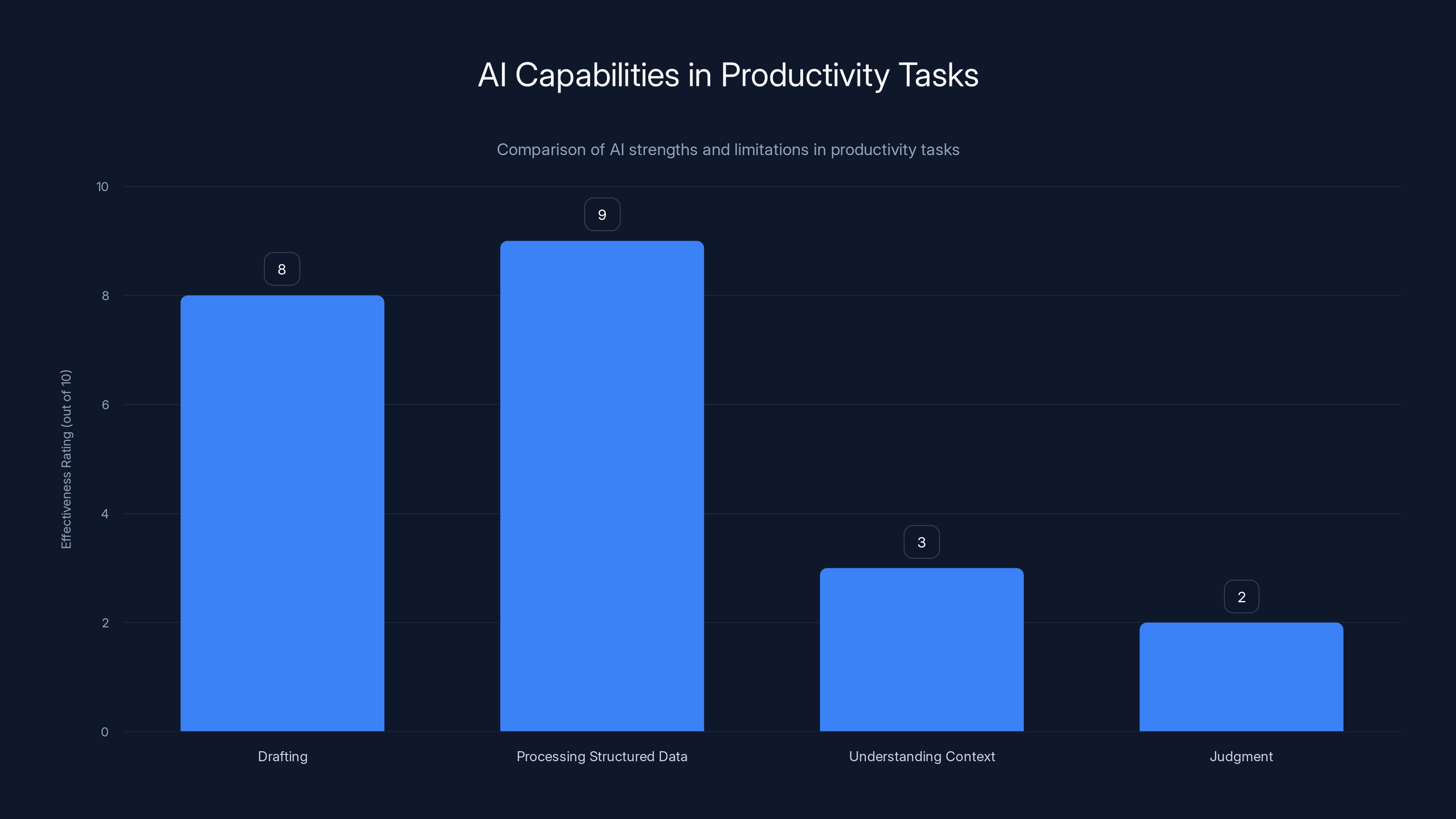

AI assistants excel at social media tasks but struggle with decision-making and contextual understanding. Estimated data based on typical performance.

AI Assistants in the Real World: The Promise and the Problem

While debates about surveillance infrastructure and government contracts play out at large technology companies, there's another conversation happening about AI assistants and what they can actually do.

Lately, there's been a lot of hype about AI agents, AI assistants that can supposedly run your life. They can manage your calendar, write your emails, conduct research, make decisions, and generally handle tasks that normally require human judgment. The pitch is seductive: Give an AI assistant control over your workflow, and it will make you dramatically more productive.

One prominent AI assistant went viral for exactly this promise. Users loved it. Tech journalists wrote about how it was the future of work. The company behind it was riding a wave of positive press and user adoption.

Then a reporter at a major tech publication did something radical: He actually used the AI assistant to run his life for a week. And he documented what happened.

Turns out, AI assistants are way better at performing tasks on social media than they are at actual decision-making. Sure, the AI could draft emails. But sometimes the drafted emails were tone-deaf or inappropriate for the context. The AI could manage calendars. But sometimes it scheduled meetings without understanding the context of the person's schedule or preferences.

More significantly, the AI would make decisions confidently that were actually wrong. It would overcommit to meetings. It would send messages that missed important context. It would complete tasks without understanding whether the approach made sense for the actual person using the system.

The problem is actually pretty fundamental. AI assistants are trained on patterns in data. They learn what a typical decision looks like, what typical language is, what typical behavior is. But your life isn't typical. Your preferences are unique. Your context is specific. Your judgment incorporates values and priorities that no training data can fully capture.

An AI assistant can help you draft an email. But deciding whether to send it? That requires understanding your relationship with the recipient, the broader context of your conversation, your strategic goals, and a hundred other things that are specific to your situation.

What's happening now is that AI assistants are being deployed in situations where they're confident but wrong. They'll autonomously send an email that seemed helpful but damaged a relationship. They'll schedule commitments that made sense statistically but don't fit the person's life. They'll make decisions that seemed right based on patterns but were actually wrong in context.

This is the uncanny valley of AI assistance. The AI is good enough to seem helpful. It's competent enough to be trusted. But it's not good enough to be fully autonomous. It needs human oversight, judgment, and course-correction. But the marketing pitch is usually "Let the AI handle it," not "Let the AI handle it with close human supervision."

The reporter's week with the viral AI assistant revealed this gap clearly. The assistant looked like it was working. It seemed productive. But when you actually paid attention to what was happening, you noticed the mistakes. Small at first, but increasingly significant. The tone of an email slightly off. A meeting scheduled at the wrong time. A decision made without adequate context.

What this reveals is something important about the current state of AI. We're in a phase where AI has gotten good enough to be dangerous, but not good enough to be trusted. It can do simple tasks well. It can help with routine work. But it can't replicate human judgment, context awareness, and values. And when it tries to do those things autonomously, it fails in ways that might be subtle but significant.

This matters because companies are racing to deploy AI agents that operate more autonomously. They're moving from "AI helps you" to "AI does it for you." That's a category difference, and the infrastructure isn't mature enough to support it yet.

The more interesting question is what the reporter's week revealed about ourselves. We're eager to believe that AI has solved the productivity problem. We want to believe that we can delegate more of our work to AI systems. We're sometimes willing to accept failures because the promise seems so compelling.

But the actual experience of using an autonomous AI assistant is more humbling. It forces you to confront how much of what you do relies on judgment, context, and values. It shows you how hard it is to capture human decision-making in an algorithm. And it reveals that even when the AI is working exactly as designed, the results might not be what you actually wanted.

The Winter Olympics and Obscure Sports Technology

In the midst of conversations about surveillance, ethics, and AI assistants, there's another story worth paying attention to: How technology is transforming obscure sports, and what that tells us about technical innovation.

The 2026 Winter Olympics is coming. If you're not a Winter Olympics enthusiast, that might not mean much. But to a small community of athletes and coaches in curling, it means everything. Because the equipment technology in curling has been undergoing a quiet revolution.

Curling is one of those sports that seems simple until you actually try it. You slide a stone across ice toward a target. Your teammates sweep in front of the stone to reduce friction and influence its direction. The team whose stone is closest to the center of the target wins the point.

It sounds straightforward. It's actually incredibly complex because of the physics involved. The ice conditions change throughout a match. Different brooms affect the stone's behavior differently. The angle at which you release the stone matters enormously. Tiny variations compound into significant differences in the final position.

For years, curlers used traditional brooms made with natural materials. They worked fine, but they were inconsistent and unpredictable. Different brooms behaved differently. The same broom behaved differently on different days depending on ice conditions and wear.

Then engineers realized they could use carbon fiber and other advanced materials to create brooms that were more consistent and more effective at reducing friction. Suddenly, the brooms themselves became a significant part of the technology equation.

This created an immediate controversy. If equipment technology was the differentiator, then the sport became more about who had access to the best equipment and less about skill. The International Curling Federation had to make rules about which brooms were legal. They had to define what made a broom "too good."

This is a microcosm of something much larger happening in technology across all domains. When you introduce new technology, you change the nature of competition. The team that understands and effectively uses the new technology gains an advantage. That's true in curling. It's true in business. It's true in government.

It's also true in surveillance technology. When ICE gains access to better data analytics tools, they gain the ability to enforce immigration law more effectively. When tech companies figure out how to use AI more creatively, they gain competitive advantage. When curlers figure out how to optimize broom technology, they gain an edge in competition.

The interesting question is what happens next. In curling, the sport adapted. They regulated brooms to preserve the balance between equipment and skill. In business and government, we're still figuring out how to regulate emerging technology.

The curling broom story is also a reminder that technology innovation happens everywhere, including in places you wouldn't expect. Engineers at Palantir didn't invent anything fundamentally new when they built data analytics tools for ICE. The technology was well-established. They just applied it to a new domain, at scale, in a way that transformed the domain.

The same is true for AI assistants. The underlying technology isn't that new. What's new is the scale at which it's being deployed, the autonomy we're giving it, and the domains in which it's being used.

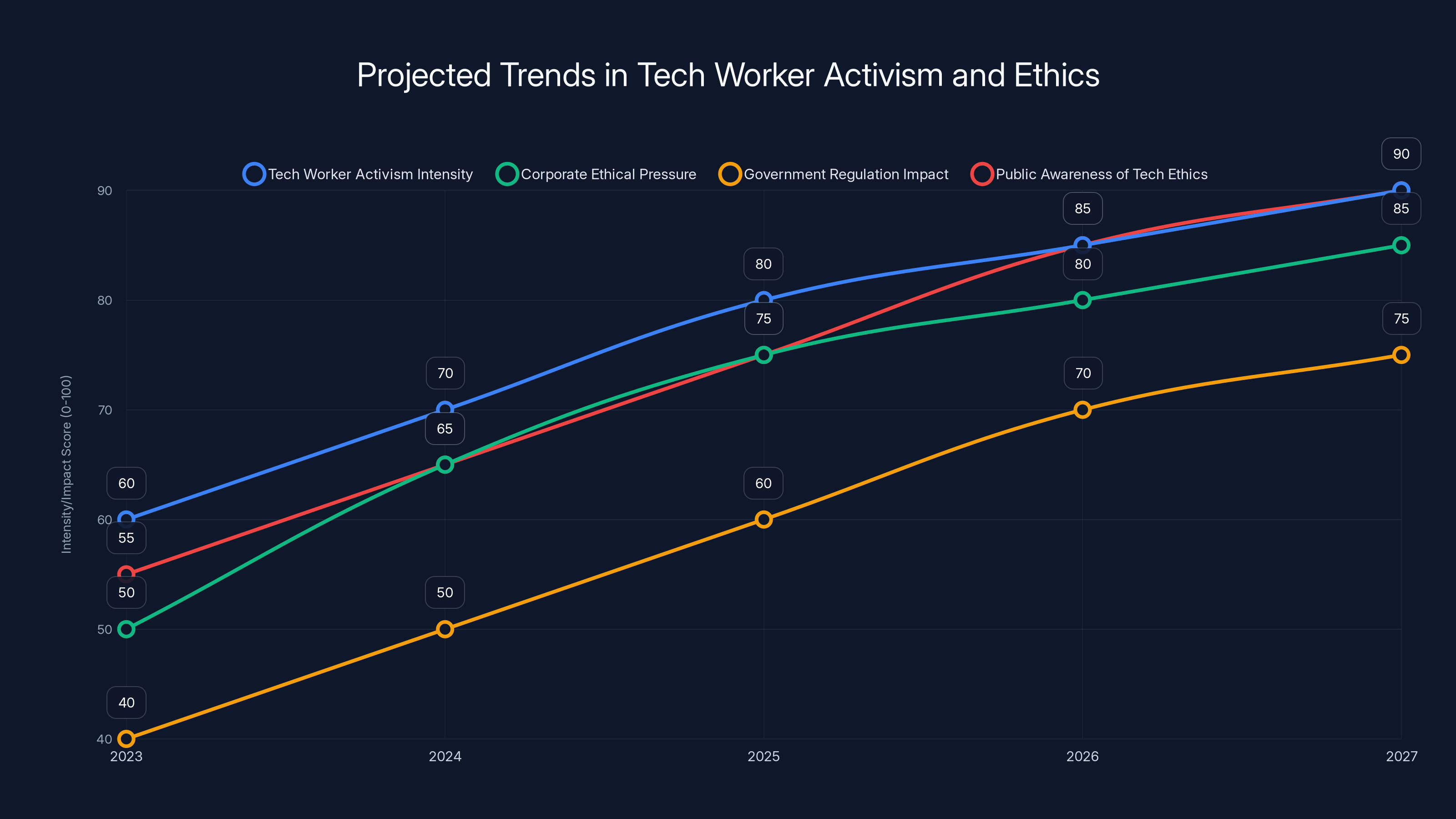

Estimated data suggests increasing intensity in tech worker activism, ethical pressure on companies, and public awareness, alongside growing government regulation impact over the next five years.

Data, Privacy, and the Infrastructure of Control

Let's zoom out and think about what's really happening here at a structural level. We're living through a moment where data is becoming the infrastructure of control.

For most of human history, control was limited by information and logistics. A government could only control what it could know about and where it could physically send people. Information was scarce. Coordination was difficult. Enforcement was labor-intensive.

But we've built systems that have dramatically changed that equation. Your driver's license is in a database. Your financial transactions are in a database. Your school records, your hospital visits, your traffic citations—all in databases. Most of these systems weren't designed for surveillance or control. They were designed for efficiency.

But once all that data is in systems that can be connected and analyzed, the potential for control becomes enormous. A government agency can cross-reference data across multiple systems to identify people who meet certain criteria. They can predict where those people are likely to be. They can concentrate enforcement resources accordingly.

This is what makes ICE's expansion plan so significant. They're not adding more agents or opening more offices. They're adding analytical capability. They're building the infrastructure to connect different data sources and identify enforcement targets more efficiently.

What makes this possible is the existence of commercial data analytics companies. Companies like Palantir exist in a weird space between the public and private sector. They're private companies, but much of their business is government contracts. They build surveillance and analytical infrastructure for government agencies.

They're not breaking any laws. In fact, they're usually working within legal frameworks. But they're extending government power by making government more efficient at surveillance and enforcement.

The question that tech workers are grappling with is whether they want to participate in that extension of power. It's not abstract. It's concrete. Build this data pipeline, and immigration enforcement will become more efficient. Build this algorithm, and the government can identify more people for enforcement. Build this interface, and agents can process more cases faster.

What's important to understand is that the people making these decisions aren't villains. They're engineers and data scientists who are trying to solve technical problems. They might even believe that they're improving the government's ability to address legitimate public policy challenges.

But the cumulative effect of all these individual decisions is the build-out of surveillance infrastructure that affects millions of people. That's the scale mismatch. Individual decisions seem reasonable. The cumulative effect is something much larger and more consequential.

This is what creates the moral pressure on tech workers. They understand the scale. They see the full picture. And many of them don't want to be part of building it.

The Ethics of Refusal: What Tech Workers Can Actually Do

If you're a tech worker reading this, you might be wondering: What am I supposed to do? Quit every job that works with the government? Refuse to build anything that could potentially be used for something problematic? That's not realistic.

The answer is more nuanced. It's not about refusing to work, but being intentional about where you work and what you're comfortable with. It's about understanding your own values and making choices that align with those values.

There are a few concrete things tech workers can do:

First, you can educate yourself. Learn what your company actually does. Not the public marketing description, but the actual clients and actual applications. What government agencies do they work with? What's the contract actually for? What does the technology actually do? Being informed is the first step.

Second, you can talk to your colleagues. You're probably not the only one with concerns. If other people share your concerns, you're in a much stronger position. Building consensus is more powerful than individual objection.

Third, you can use organizational processes. Most tech companies have ethics committees, internal forums, or other mechanisms for raising concerns. Use them. Document your concerns. Push for answers. Make it clear that this matters to you.

Fourth, you can set personal boundaries. Maybe you can work for a company that does some government work, but you draw a line at certain kinds of government work. You might say no to projects that directly enable enforcement actions against vulnerable populations. You might insist on seeing impact assessments before you agree to a project.

Fifth, you can leave. If the company won't address your concerns and you genuinely believe the work is wrong, you can find another job. That's hard. It has real consequences. But it's an option, and sometimes it's the right choice.

What's important to understand is that tech workers have more power than they usually realize. Companies need smart engineers. Good engineers can find other jobs. That creates leverage. When enough engineers say "I'm not comfortable with this," companies have to listen.

This is already happening. At multiple tech companies, employee activism has forced conversations about government contracts, surveillance technology, and ethics. Some of those conversations have resulted in policy changes. Others have resulted in engineers leaving. But the conversations are happening, and they're shifting what's considered acceptable in tech.

The Palantir CEO's non-response suggests that the conversation is far from over. Employees aren't satisfied. Management is dug in. The conflict is going to continue and probably intensify.

What's interesting is that these conversations are happening at the intersection of technical work and political power. Tech workers are realizing that what they build has political consequences. That's a significant shift. For decades, tech sold itself as apolitical, as neutral tool-building. But there's no such thing as political neutrality when you're building surveillance infrastructure for government agencies.

AI tools excel in drafting and processing structured data but struggle with understanding context and judgment. Estimated data based on typical AI capabilities.

Government Surveillance and the 2026 Olympics

Here's something interesting: The 2026 Winter Olympics is happening in the same country and time period as ICE's expansion. That's not a coincidence in terms of timeline, but there's an interesting conversation happening about how to protect the event from exploitation.

Large sporting events are targets for various forms of surveillance and enforcement. Security agencies want to monitor the event. Immigration agencies want to enforce immigration law around the event. Local law enforcement wants to increase patrols. Corporations want to track consumer behavior.

For the 2026 Olympics, there's been discussion about how much surveillance would be acceptable, and what protections are needed for athletes, spectators, and local communities. It's become a microcosm of the larger surveillance debate.

On one hand, security is important. You want to protect the event and the people attending it. On the other hand, you don't want the Olympics to become a testing ground for mass surveillance infrastructure.

The tension is real. And it reveals something important: Governments are going to use major events as opportunities to test and deploy surveillance infrastructure. The Olympics is one example. Conventions, major sporting events, political conferences—all of these are opportunities to normalize surveillance systems that might later be expanded to general use.

This is relevant to the ICE expansion story because it's part of the same trend. Governments are systematically building the infrastructure and justifying the tools for broader surveillance and enforcement. What gets tested at the Olympics might get deployed at the border. What works for counterterrorism might become standard for immigration enforcement.

Tech workers building these systems understand this trajectory. They see where the technology is heading. And many of them have decided they don't want to be part of building it.

The Future of Tech Worker Activism and Ethics

Where does this all go from here? It's hard to predict, but a few patterns seem clear:

First, tech worker activism is going to continue and probably intensify. The conversation about ethics in tech is no longer fringe. It's becoming mainstream, especially among younger engineers who grew up understanding technology's impact on society.

Second, companies are going to face increasing pressure to make clear choices about government work. The days of quietly doing government contracts while maintaining a progressive public image are probably over. Companies are going to have to choose: Are we comfortable with government surveillance work, or are we not?

Third, the tools are going to keep getting more powerful, which will make the ethical stakes higher. As data analytics improves, as AI gets more capable, as integration across systems becomes more sophisticated, the potential for surveillance and control increases. That will create more pressure on people building these systems.

Fourth, regulations are probably coming. Governments are going to start regulating how companies build and deploy surveillance technology. Whether those regulations will actually constrain surveillance or just legitimize it is an open question.

Fifth, there's going to be more public reckoning about what technology actually enables. The coverage of ICE's expansion plans, the focus on Palantir's government contracts, the viral story about AI assistants failing in real-world use—these are all signs that people are waking up to what the technology actually does versus what the marketing claims.

The most likely scenario is that we're entering a period of significant conflict and change in how tech relates to government and society. Tech workers are going to become more active in shaping what their companies do. Companies are going to face more pressure from employees and the public. Governments are going to push back when their surveillance capabilities are constrained. And in the middle of all that, the technology keeps getting more powerful and more consequential.

For individual tech workers, this means the stakes of their choices are getting higher. The work they do has real consequences for real people. Deciding where to work and what to build is becoming a genuinely important ethical decision, not just a career choice.

That's exhausting and sometimes paralyzing. But it's also an opportunity. Tech workers have real power. They can shape what gets built and how it gets used. That power is most effective when it's exercised intentionally, in community with other people who share similar concerns.

Estimated data suggests that specific commitments from CEOs lead to higher employee trust compared to vague statements or no response.

The Broader Pattern: When Innovation Meets Power

If you zoom out from all of these specific stories—Palantir's government contracts, ICE's expansion plans, AI assistants failing in real-world use—you see a broader pattern about how technology and power interact.

New technology is always adopted first by powerful institutions. They have resources and incentive to use it. Governments adopt surveillance technology because it helps them exercise control more efficiently. Corporations adopt AI systems because it helps them increase productivity and reduce costs. The military adopts new weapons because it gives them tactical advantage.

The people building these systems often have limited visibility into how they'll actually be used and what the consequences will be. An engineer might build a data pipeline thinking it's just a technical problem. They might not fully understand that the output of that data pipeline is going to be used to identify people for immigration enforcement.

But even if they do understand, they might feel powerless to do anything about it. One person quitting doesn't stop the project. One person raising concerns might just get them fired. The system is much larger than any individual.

That creates a kind of moral trap. The system depends on many people making small decisions. But from the perspective of any individual person, their individual decision seems insignificant. You can convince yourself that if you don't do the work, someone else will. So why sacrifice your career?

But that logic is how harmful systems get built. Not because any individual person wanted to build a harmful system, but because each person convinced themselves that their individual contribution was insignificant.

Breaking out of that trap requires collective action. If enough engineers say they won't build surveillance infrastructure, the company has to listen. If employees are united on an ethical principle, they have real leverage. That's what we're starting to see happen in tech.

The interesting question is whether that collective action can continue to be effective as the power differences become more stark. It's relatively easy for tech workers to push back on issues like government surveillance when the industry is booming and there's a lot of demand for talent. What happens when the economy slows and engineers have fewer options? Will they still have the courage to take stands on ethics? That's the real test of whether tech worker activism is a sustainable force for change or a temporary phenomenon.

AI Tools for Productivity and the Remaining Limitations

Let's come back to the AI assistant story because it raises important questions about what AI can and can't do, and what we should realistically expect from these tools.

When a reporter spent a week letting an AI assistant run their life, they discovered something important: AI is really good at some things and really bad at others. It's good at drafting. It's bad at judgment. It's good at processing structured data. It's bad at understanding context and nuance.

The gap between what AI is good at and what we'd need it to be good at to truly automate human work is significant. It's not a gap that's going to be closed by better algorithms or more data. It's a gap that's rooted in the nature of human decision-making and human work.

Human judgment involves values. It involves understanding context that extends beyond the immediate situation. It involves prioritizing competing interests and making decisions that involve trade-offs. It involves knowing when the rules don't apply and you need to make an exception.

AI systems can be trained to mimic these behaviors. They can learn patterns of human judgment. But that's not the same as actually understanding or having judgment. When the situation is slightly different from the training data, the AI will fail in ways that are sometimes obvious and sometimes subtle.

So the realistic near-term future for AI assistants isn't autonomous systems running people's lives. It's collaborative systems that help humans do their work better. The AI generates drafts. The human reviews and edits. The AI processes data. The human interprets and applies judgment. The AI suggests options. The human decides.

What's happening now is that the marketing narratives around AI are getting ahead of the actual capabilities. Companies are selling "AI agents" that will "run your business" or "manage your life." The reality is much more limited. You get tools that are better at some tasks, but they still require significant human oversight and judgment.

That's not a failure of AI. It's a failure of marketing and expectation-setting. AI is genuinely useful. It can make humans more productive. But it's not magic. It has real limitations. And understanding those limitations is crucial if you're going to actually use these tools effectively.

The reporter's week with the AI assistant was valuable precisely because it revealed those limitations clearly. Most people don't spend a full week with an AI assistant. They use it occasionally and form impressions based on limited interaction. But the reporter gave it real responsibility and documented what happened. And what happened revealed how far we still are from true autonomy.

The Intersection of Activism, Technology, and Institutional Change

One more thing worth thinking about is how institutional change actually happens in large organizations, and what that tells us about the potential for tech worker activism to create change.

Institutions are resistant to change. They have systems, processes, and incentives that support the status quo. Changing them requires pressure from multiple directions simultaneously. Employee activism alone usually isn't enough. You also need external pressure (media coverage, public opinion), regulatory pressure, or economic pressure (losing customers or talented employees).

What's interesting about the current moment in tech is that all three types of pressure are starting to align. Employees are raising concerns. Media is covering the issues. Regulations are being discussed. That convergence creates the possibility for actual institutional change.

But institutions don't change easily. When you see a CEO deliver a non-response to employee concerns, that's not just bad communication. It's a strategic decision that the company isn't going to respond to pressure. It's a decision to accept the consequences (employee departures, reputational damage, possibly regulation) rather than change fundamental business practices.

That's a gamble. The company is betting that they can weather the employee activism, the media coverage, and any regulatory pressure that comes. They're betting that government contracts are too valuable to give up. They might be right. Or they might be wrong.

But the decision has been made. The company has chosen to double down on government contracts rather than respond meaningfully to employee concerns. That's going to result in a significant number of talented engineers leaving. It's going to damage the company's ability to recruit new talent. And it's probably going to accelerate calls for regulation.

So even if the CEO's non-response seemed like a tactical victory (the company didn't commit to any changes), it might actually be a strategic loss. By refusing to engage meaningfully with employee concerns, the company might have accelerated the very changes it was trying to avoid.

This is the dynamic that plays out in institutional change. When institutions resist pressure, they often inadvertently accelerate change by radicalizing the people pushing for change and galvanizing external pressure. If the company had taken the concerns seriously and made some meaningful changes, it might have defused the activism. By dismissing the concerns, they're validating the concerns and motivating further action.

Looking Ahead: The Next Battlegrounds

As we look forward, there are a few areas where we're likely to see intensified conflicts between tech workers, companies, and governments:

First, AI and surveillance convergence. AI is making surveillance dramatically more efficient and more capable. The combination of AI-powered tools with access to large databases is creating surveillance capabilities that didn't exist before. As these capabilities mature, the conflict between tech workers and companies doing this work will probably intensify.

Second, data access and regulation. Governments want access to data for enforcement purposes. Tech companies want to make data available (because it's profitable). Privacy advocates want to restrict data access. As these pressures collide, we're going to see increased conflict over data governance.

Third, international dimensions. Different countries are taking different approaches to regulating tech companies and surveillance. That's creating opportunities for companies to forum-shop, finding jurisdictions with fewer regulations. But it's also creating pressure for international standards and coordination.

Fourth, the political economy of tech labor. As AI becomes capable of doing some of the work that humans currently do, the bargaining power of tech workers might decline. That would make it harder for tech workers to push back on ethical concerns. Alternatively, if tech workers unionize or organize more effectively, their bargaining power might increase. The outcome of that conflict is going to shape the future of tech.

All of these conflicts are playing out against the backdrop of broader political instability and changing attitudes toward government authority. Different political parties and movements have different views on surveillance, immigration enforcement, and technology regulation. As political control shifts, the pressure on tech companies will shift as well.

But one thing seems relatively stable: The tension between what tech workers think is ethical and what companies are willing to do is not going away. That tension is baked into the current moment. Tech companies need talented engineers. Tech workers increasingly understand what their work enables. And they're increasingly unwilling to participate in building systems they find unethical.

What happens next depends on what choices these groups make in the coming months and years.

FAQ

What is the Uncanny Valley podcast and why does it matter?

The Uncanny Valley podcast, produced by WIRED, brings together journalists and experts to discuss the intersections of artificial intelligence, technology, politics, and society. It matters because it covers stories that mainstream media often misses or underreports, giving visibility to issues like tech worker activism, government surveillance expansion, and the real-world limitations of AI systems. The podcast serves as an important space for public conversation about technology's role in shaping society and power dynamics.

Why are tech workers concerned about government contracts?

Tech workers are increasingly concerned about government contracts, particularly those involving surveillance and enforcement agencies, because they understand what the technology enables. When they build data analytics tools for immigration enforcement, they're directly enabling more efficient identification and deportation of immigrants. When they build algorithms for surveillance, they're extending government power over communities. Many workers find this morally unacceptable and worry about their complicity in systems that harm vulnerable populations.

What is ICE's expansion plan and how does technology enable it?

ICE is systematically expanding its operations to nearly every state in the United States, moving beyond traditional border enforcement to interior enforcement in communities that have limited immigration enforcement history. Technology enables this expansion by allowing ICE to efficiently connect different government databases, identify people likely to be undocumented immigrants, and concentrate enforcement resources. Data analytics tools developed by companies like Palantir are crucial to making this scaled-up enforcement operationally feasible.

How do AI assistants actually perform in real-world use?

AI assistants perform well at specific, bounded tasks like drafting emails or scheduling meetings, but struggle significantly with complex decision-making that requires judgment, context awareness, and understanding of nuance. When given autonomy, they frequently make mistakes that are subtle but significant, such as sending inappropriate communications or overcommitting schedules. They lack the human capacity to understand the broader implications of their actions and often fail in situations that deviate from their training data.

What can tech workers actually do if they have ethical concerns?

Tech workers can educate themselves about their company's actual work and clients, build consensus among colleagues who share concerns, use internal organizational processes to raise and document concerns, set personal boundaries about what work they're willing to do, or ultimately leave if the company won't address those concerns. The most effective approach is usually collective action, as united employees have greater leverage with management than individuals acting alone. Several tech companies have changed their policies as a result of employee activism.

How does surveillance technology change the relationship between government and citizens?

Surveillance technology fundamentally shifts the balance of power between government and citizens by making it dramatically easier and cheaper for governments to monitor people's locations, communications, financial transactions, and other behaviors. What once required human agents and significant resources can now be done algorithmically at scale. This creates the infrastructure for control and enforcement capabilities that didn't exist before, raising significant concerns about privacy, autonomy, and the potential for government abuse.

Why did the Palantir CEO's response to employee concerns matter?

The CEO's nearly hour-long non-response demonstrated that the company was not going to meaningfully engage with employee ethical concerns about ICE contracts. By speaking in abstractions while avoiding specific commitments or answers to specific questions, the CEO signaled that the company would prioritize government contracts over employee concerns. This response likely accelerated employee departures and damaged the company's ability to recruit talent concerned about ethics, ultimately validating the employees' concerns rather than addressing them.

What does the curling story tell us about technology and competition?

The evolution of curling broom technology illustrates how technological innovation changes the nature of competition and creates ethical questions about fairness. When advanced materials and engineering made certain brooms dramatically more effective, it shifted competition from pure skill to equipment access and optimization. This required regulatory intervention to preserve the sport's integrity. It parallels larger questions about how technology changes society and whether innovation should be regulated to maintain fairness or other values.

Conclusion

We're at an inflection point in how technology intersects with power, government, and society. Tech workers are waking up to the consequences of their work. Companies are facing pressure from multiple directions to make clear ethical choices. Governments are building surveillance infrastructure that's becoming increasingly sophisticated and pervasive. And the tools themselves are getting more powerful, making the stakes of these choices higher.

There are no easy answers here. Technology isn't inherently good or bad. The same data analytics tools that can help a city optimize traffic can also help an immigration enforcement agency identify people for deportation. The same AI systems that can draft emails can also be used to automate surveillance and control.

What matters is who builds these tools, for what purposes, with what oversight and consent. Right now, those decisions are often made in private company offices and government agencies with limited accountability to the public or to the workers building the systems.

The tech worker activism we're seeing is an attempt to democratize those decisions, to assert that the people building the tools should have a say in how they're used. That's a fundamentally important question about power and responsibility in a technological society.

Some tech companies will respond to this pressure by becoming more thoughtful about government contracts and surveillance work. Others will double down and accept the consequences. Some governments will regulate surveillance technology. Others will shield it from regulation. Some tech workers will find companies whose values align with their own. Others will face genuine dilemmas about how to maintain their livelihoods while staying true to their ethics.

What won't happen is a return to the naive idea that technology is neutral and amoral. We've learned too much about what technology enables. We understand too well the consequences of building surveillance infrastructure, designing algorithms that perpetuate bias, or creating tools that extend government power. Tech workers understand this. Companies understand this. Governments understand this.

The question now is what we do with that understanding. Do we build the infrastructure anyway because the work is lucrative and powerful? Do we refuse to participate and accept the career consequences? Do we try to find middle grounds where we can do some technical work while avoiding the most ethically problematic applications? Do we work for change from within institutions or push for change from outside?

These aren't abstract philosophical questions. They're practical questions that real tech workers face every day. And the answers they choose will shape the kind of society we build and the kind of surveillance and control infrastructure that society rests on.

The conversations happening in Slack channels at tech companies, the employees raising concerns with CEOs, the journalists covering government surveillance expansion, the AI assistants failing in real-world use, the curling engineers optimizing brooms—these are all pieces of a larger story about how we relate to technology and how we distribute power in a technological society.

It's a story that's still being written. The outcome depends on the choices that tech workers, company leaders, government officials, and citizens make in the coming years. That makes this moment simultaneously urgent and full of possibility. The future isn't predetermined. It's being shaped by people making choices right now about whether and how to participate in building surveillance infrastructure, creating more powerful AI systems, and extending government power.

Understood in those terms, the question for tech workers isn't abstract or philosophical. It's practical and immediate: What am I going to do with the power and knowledge I have? What kind of tools am I going to help build? What kind of society am I going to help create?

Those are the questions that matter now.

Key Takeaways

- Tech workers are increasingly conflicted about their employers' government surveillance contracts, leading to public activism and employee departures.

- Government agencies like ICE are systematically expanding surveillance capabilities using data analytics technology developed by private companies.

- AI assistants promise autonomy but fail in real-world use cases requiring human judgment and context understanding.

- Employee activism has become a significant check on corporate behavior, with workers leveraging collective action and external pressure to shape company policies.

- The infrastructure of surveillance is built through many individual technical decisions that collectively create powerful systems of government control.

Related Articles

- OpenAI Disbands Alignment Team: What It Means for AI Safety [2025]

- OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads, Warns of 'Facebook' Path [2025]

- CBP's Clearview AI Deal: What Facial Recognition at the Border Means [2025]

- Surfshark's Free VPN for Journalists: Protecting 100+ Media Outlets [2025]

- Discord's Age Verification Disaster: How a Privacy Policy Sparked Mass Exodus [2025]

- AI-Generated Music at Olympics: When AI Plagiarism Meets Elite Sport [2025]

![AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-ethics-tech-workers-and-government-surveillance-2025/image-1-1770935836435.jpg)