Space X Lowers Starlink Satellites: A Major Step Toward Space Safety

Here's the thing about space. It looks empty until you start putting thousands of objects into it. Then suddenly, you've got a problem.

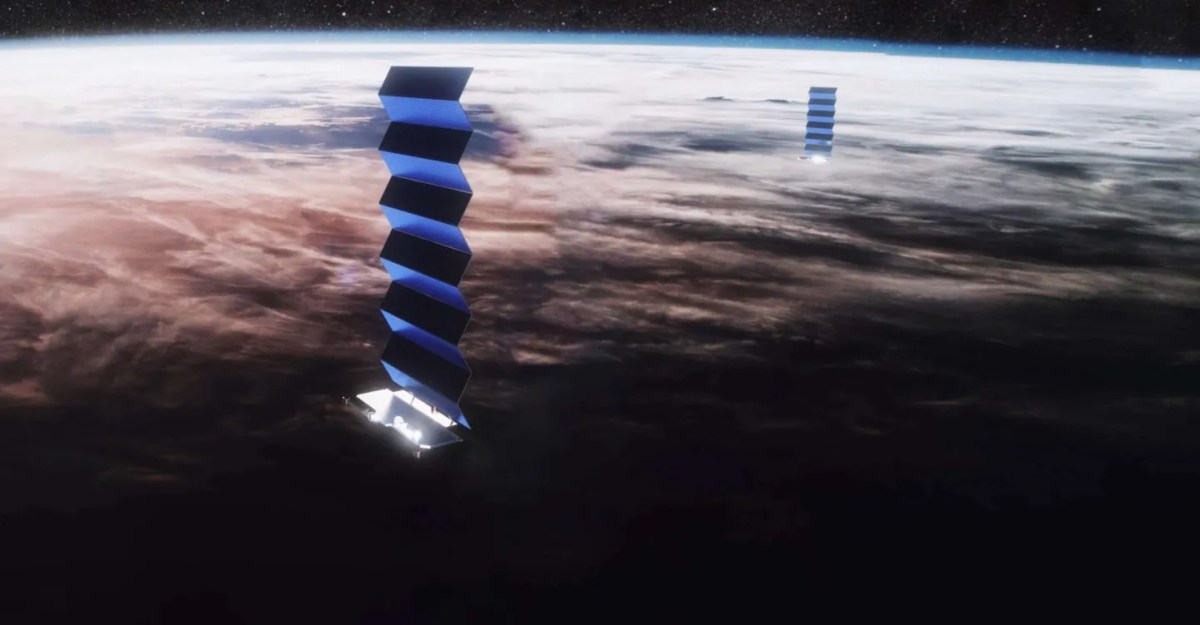

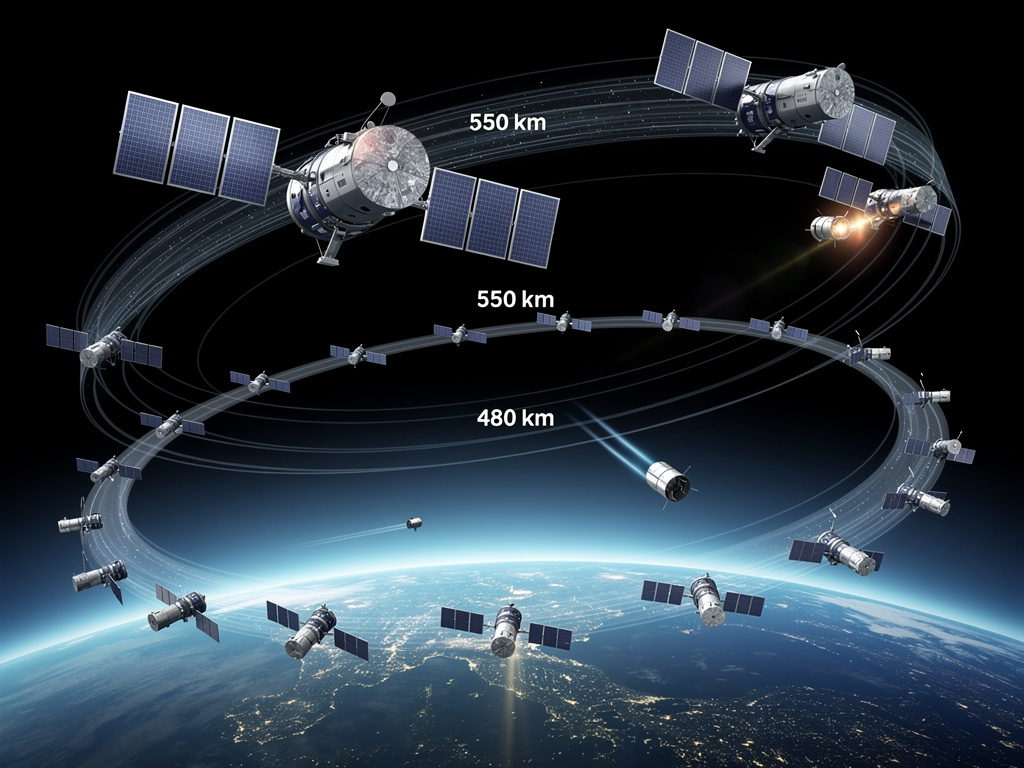

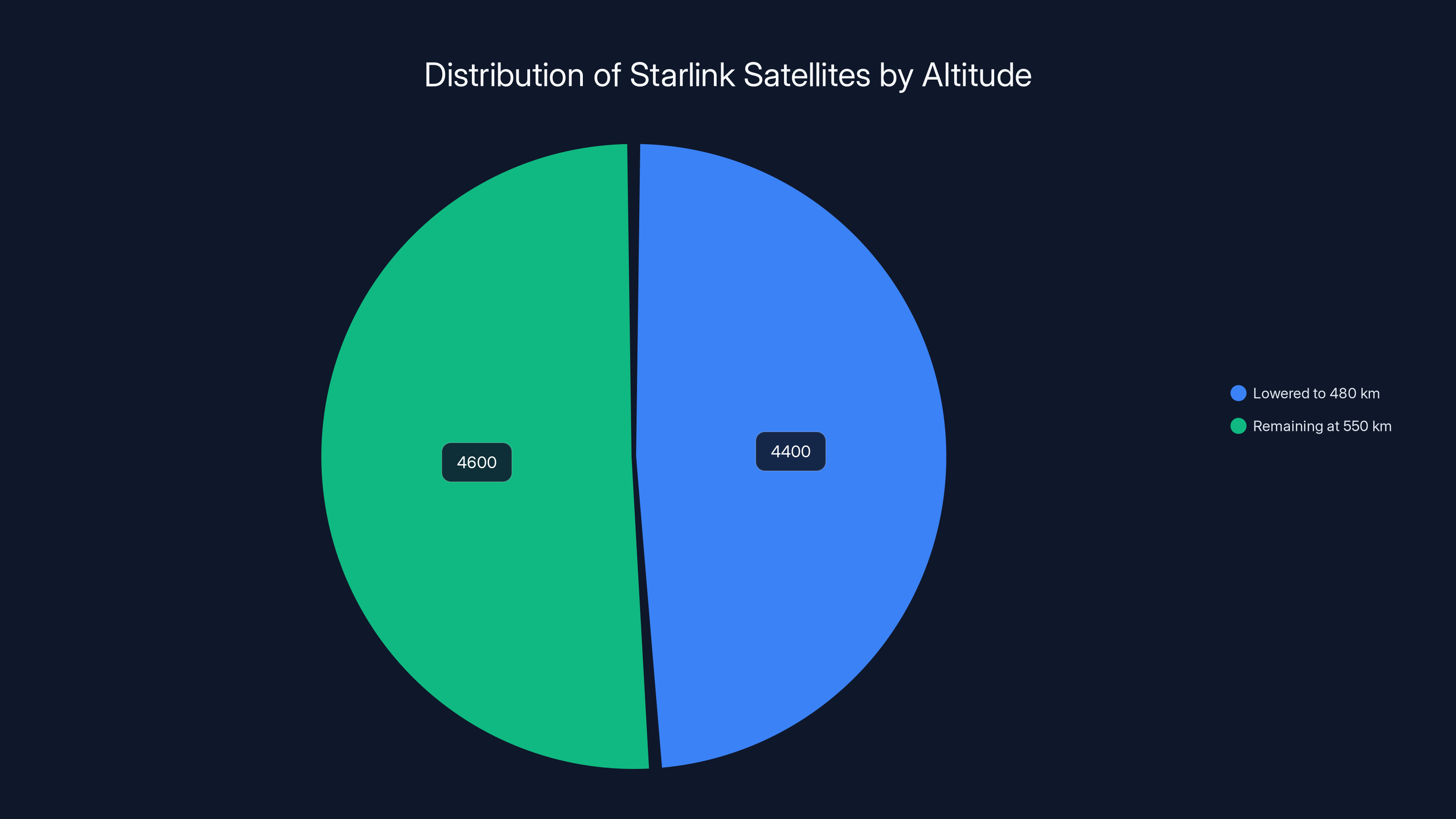

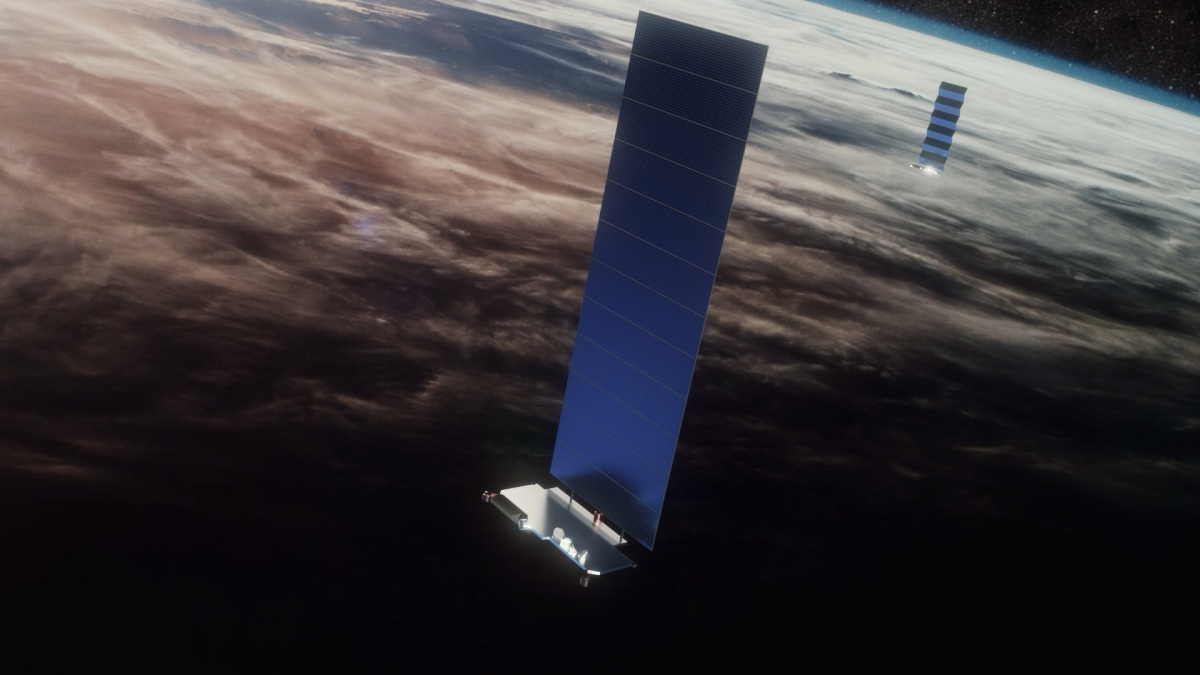

Space X just announced it's making a significant shift in how it operates its massive Starlink constellation, and the reason reveals just how crowded low Earth orbit is getting. After one of its Starlink satellites catastrophically failed and another barely avoided a collision with a Chinese satellite, the company is lowering the orbital altitude of approximately 4,400 of its 9,000-plus operating satellites. That's roughly half their fleet.

The move sounds simple on the surface. But understanding why this matters requires looking at what's actually happening 300 miles above your head, how many objects are up there, and what happens when they collide at orbital speeds.

Space X says it'll drop about 4,400 Starlink satellites from their current altitude of roughly 550 kilometers (341 miles) down to 480 kilometers (298 miles) over the coming months. Why the specific altitude? Because at that lower height, anything that breaks or stops working falls back to Earth much faster. It also puts them below where most other satellite constellations operate, reducing collision risk exponentially.

Let's unpack what this really means for space traffic, for the future of satellite internet, and for the bigger picture of how we're managing the final frontier.

The Space Debris Crisis Nobody Talks About

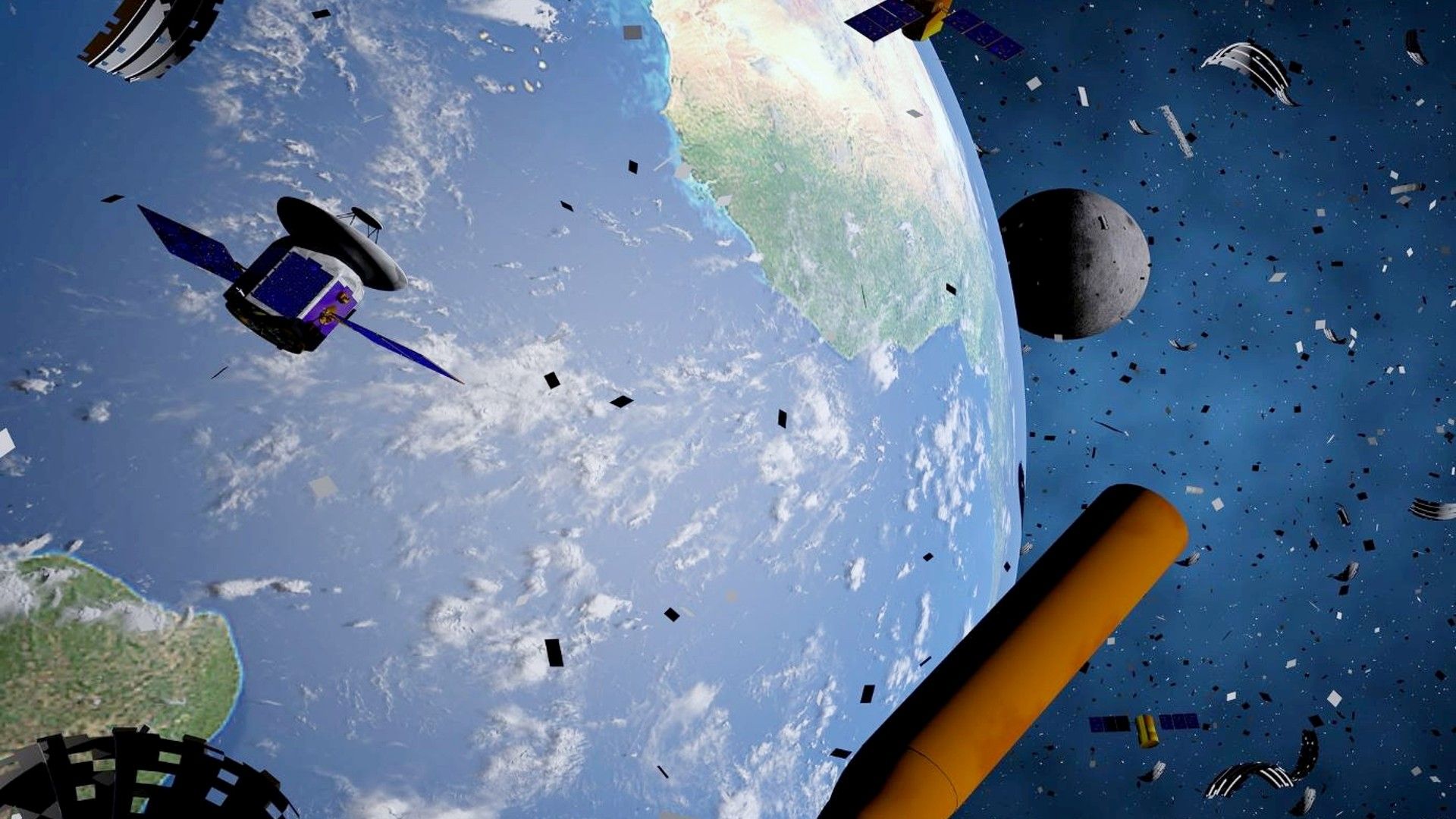

Space debris is one of the most dangerous invisible problems in orbit. Unlike a car accident, where two vehicles collide at maybe 60 miles per hour, satellites collide at velocities around 17,500 miles per hour. That's roughly 23 times the speed of a rifle bullet.

At those speeds, even a paint fleck can puncture a satellite. A lost screw becomes a projectile. Dead satellites become weapons. When two objects collide in orbit, they don't bounce apart like billiard balls. They shatter. And those shattered pieces become more projectiles, hitting other satellites and creating more debris in a cascading effect.

This phenomenon is called Kessler Syndrome, named after Donald Kessler, a NASA scientist who warned decades ago that space could become unusable if collisions continued unchecked. The scenario plays out like this: one collision creates hundreds of pieces of debris. Those pieces hit other satellites. That creates thousands of pieces. Then millions. Eventually, entire orbital regions become impassable.

We're not in full Kessler Syndrome territory yet. But we're moving in that direction faster than anyone expected.

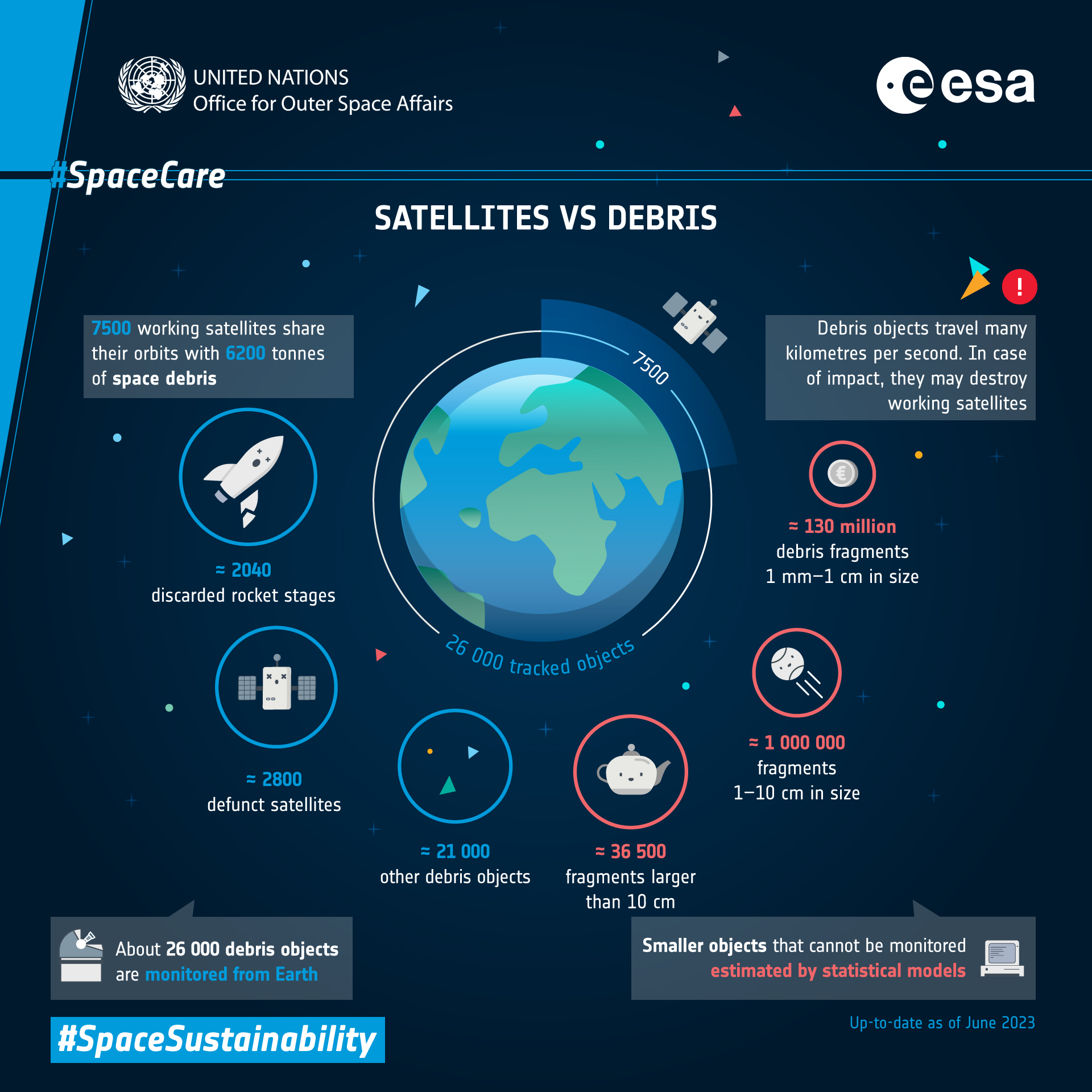

NASA tracks roughly 34,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than 10 centimeters. But the pieces they can't track—anything smaller than a softball—number in the millions. These tiny fragments are statistically almost as dangerous as the big ones because of orbital velocities.

When Space X says it's lowering satellites to reduce collision risk, it's not being dramatic. The numbers matter.

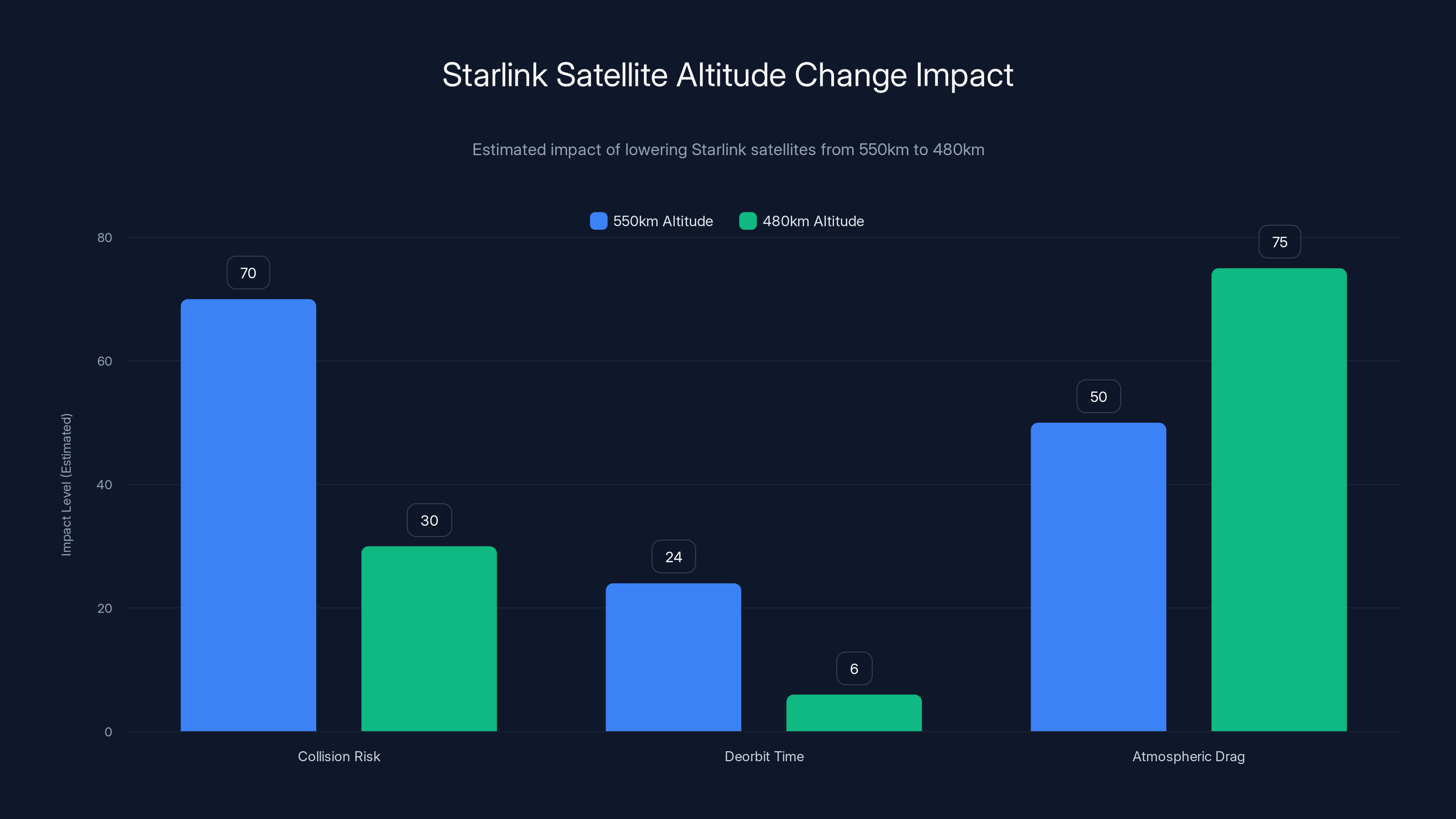

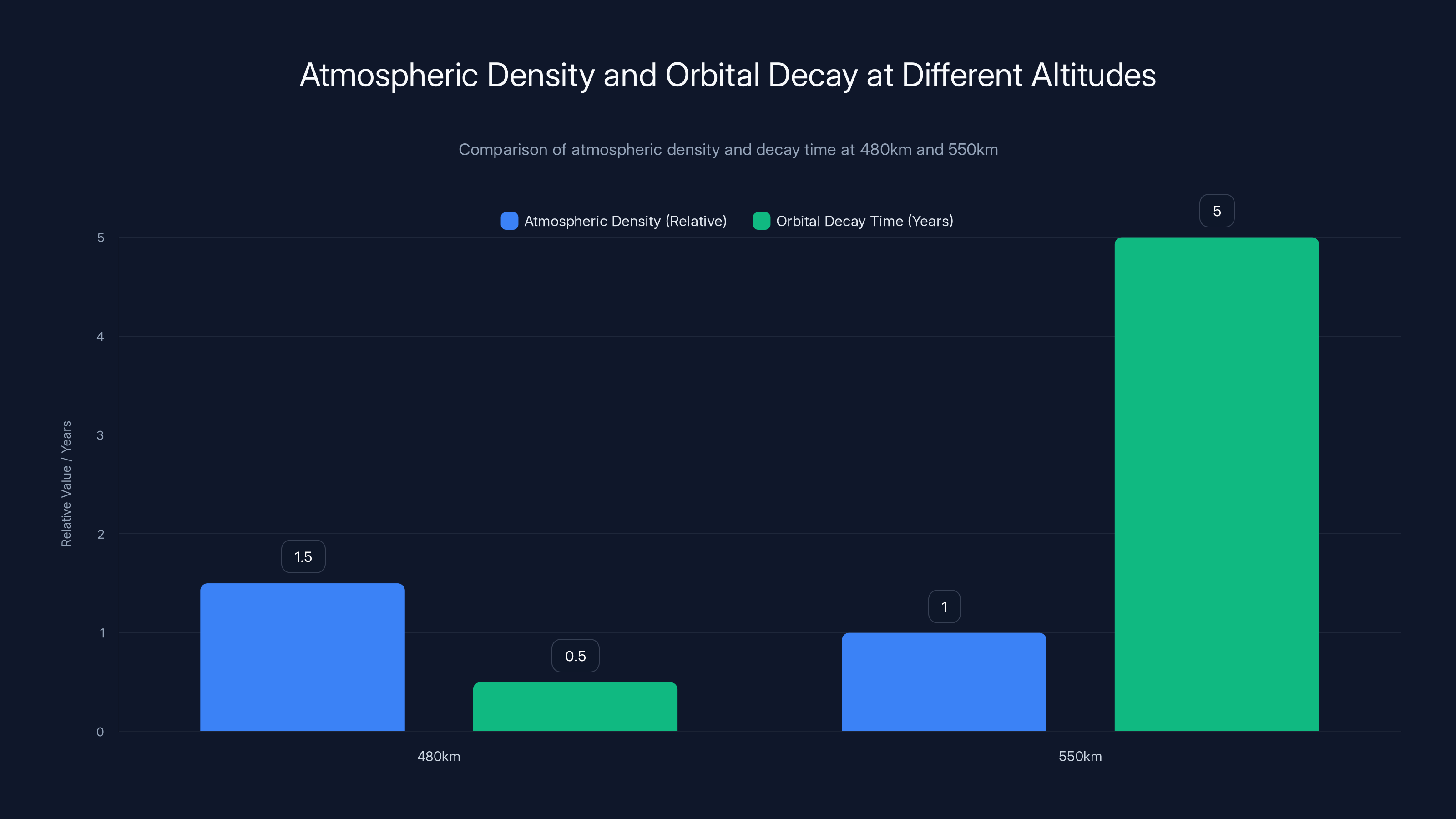

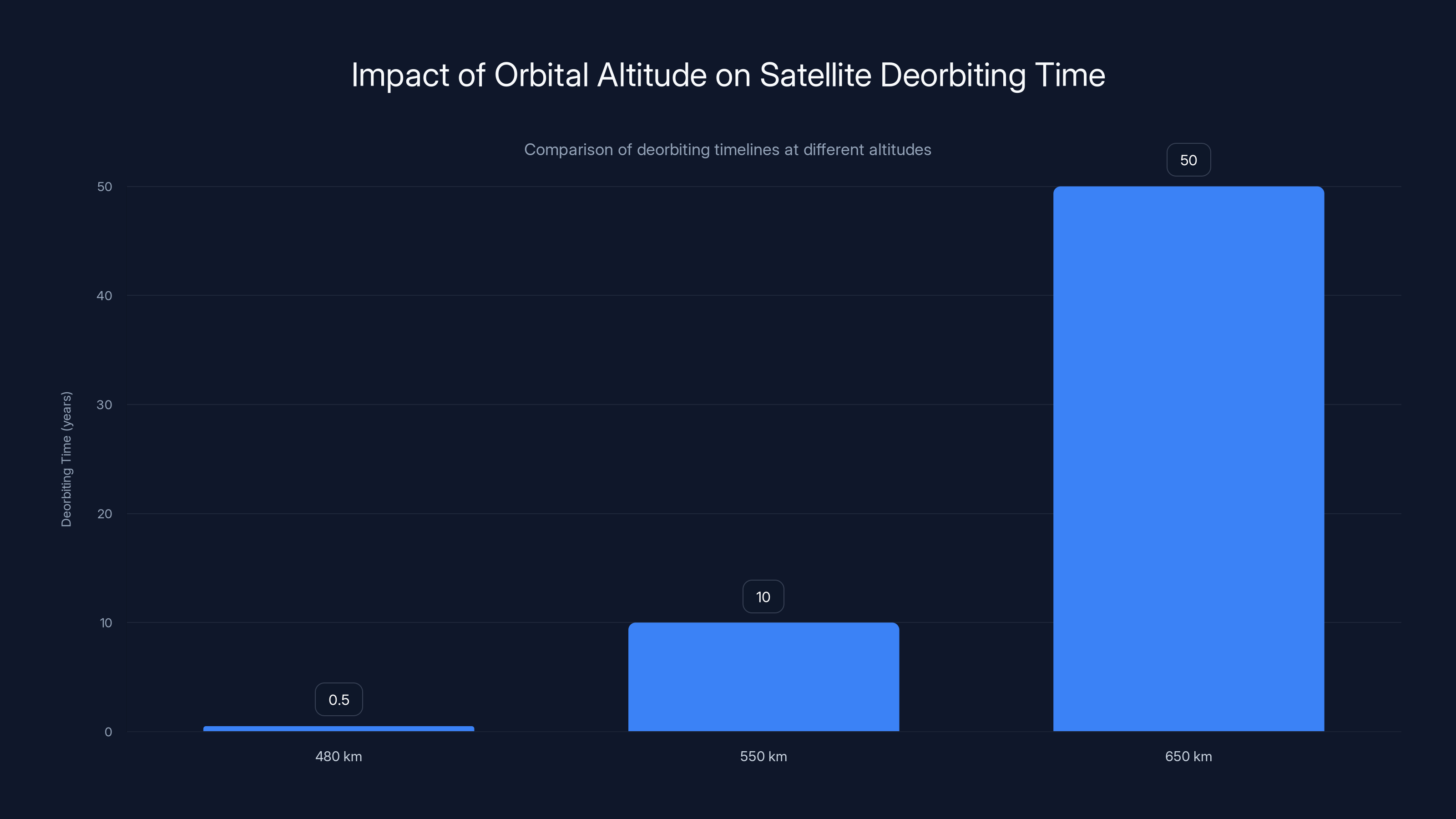

Lowering Starlink satellites to 480km significantly reduces collision risk and deorbit time due to increased atmospheric drag. (Estimated data)

Why 480 Kilometers Actually Matters

The difference between 550km and 480km might seem trivial. It's less than the distance between New York and Boston. But at orbital altitudes, it changes everything.

First, the deorbiting timeline. At 550km, a dead satellite takes years to naturally fall back to Earth. Natural atmospheric drag is extremely weak that high. At 480km, that timeline compresses dramatically. A satellite with no functioning engines falls back to Earth in weeks or months instead of decades. That's crucial because it means fewer years where an inactive, uncontrollable satellite can pose collision risks.

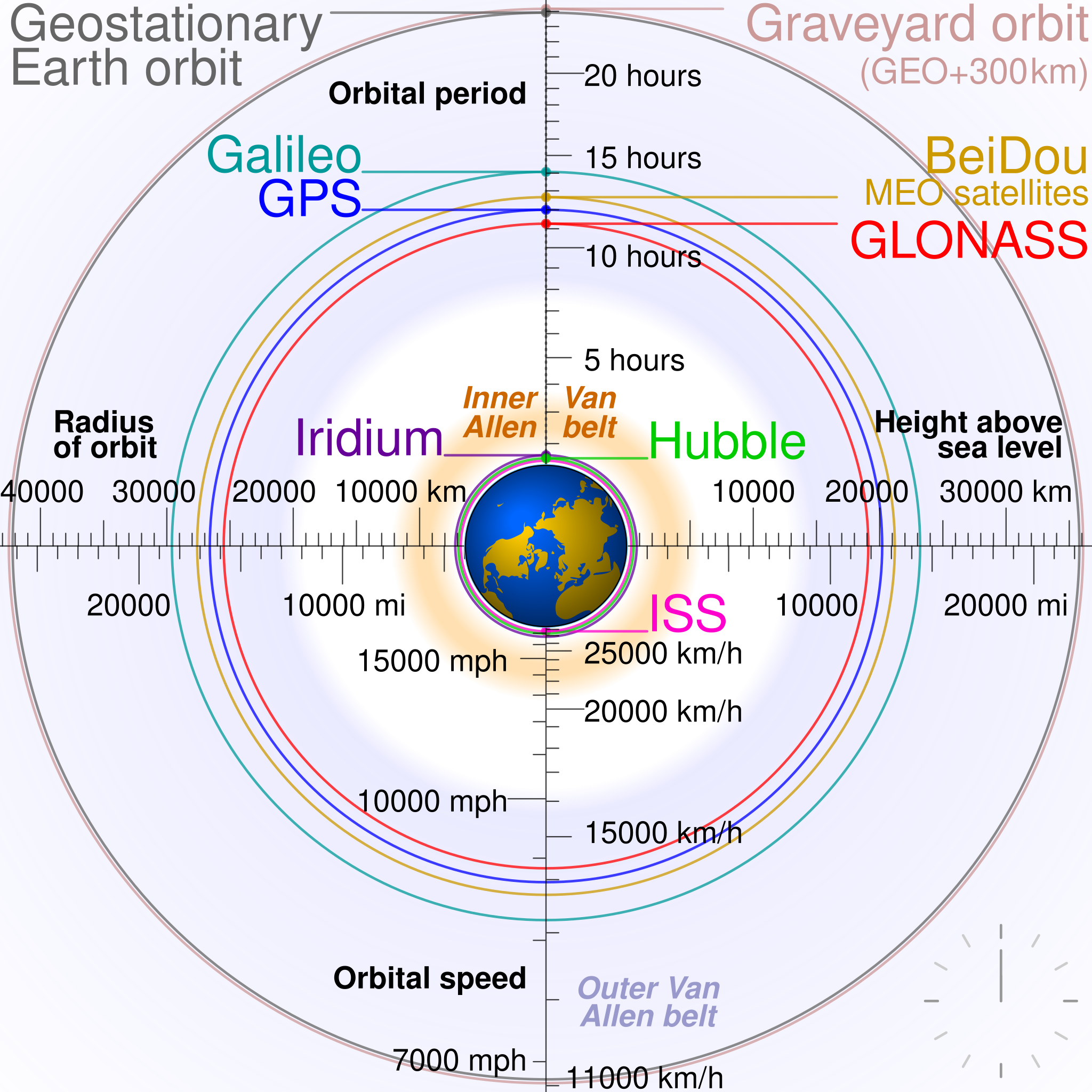

Second, the traffic patterns. Different altitudes host different satellite constellations. By moving Starlink satellites below the 500km threshold, Space X is physically separating its fleet from most other operational satellite networks. One Web's satellites operate at around 650km. European Space Agency projects and various government satellites cluster at different altitudes. This stratification reduces the likelihood of having to navigate around other massive constellations.

Third, the debris situation improves mathematically. Lower orbits decay faster naturally. Debris at 480km doesn't linger for centuries like debris at higher altitudes. It comes down in years rather than decades.

Michael Nicolls, Space X's VP of Starlink Engineering, explained it clearly: "The number of debris objects and planned satellite constellations is significantly lower below 500km." Translation: fewer things to hit you, and whatever you might hit doesn't stick around as long.

The Recent Incidents That Triggered the Change

Space X didn't make this decision in a vacuum. Two specific events forced the company's hand.

First, one of its Starlink satellites catastrophically failed in orbit. Dead satellites don't fall immediately. Without propulsion, it became space junk. Now it's circling Earth uncontrollably, and any satellite flying nearby has to dodge it or accept collision risk. For a constellation of 9,000+ satellites, that's not acceptable.

Second, another Starlink satellite came dangerously close to colliding with a Chinese satellite. This wasn't just close in absolute terms. In space traffic terms, it was terrifyingly close. The conjunction warning came with minimal margin for error. If both satellites had been in slightly different positions, we might be talking about a catastrophic collision that created hundreds of pieces of new debris.

These weren't freak occurrences. They're indicators of a real problem: low Earth orbit is getting congested, and current practices aren't cutting it anymore.

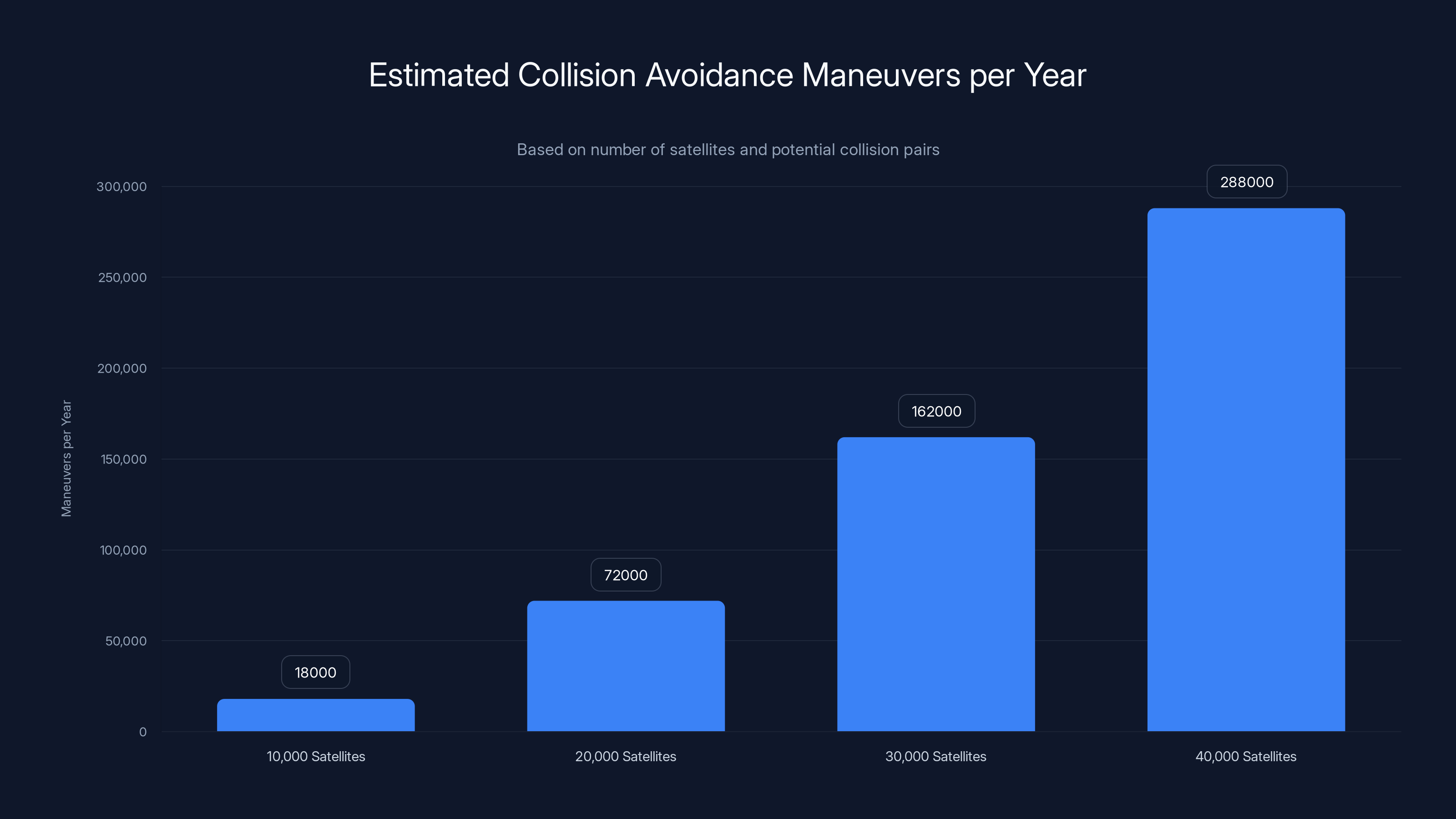

As the number of satellites increases, the number of collision avoidance maneuvers grows exponentially. Estimated data based on potential collision pairs.

How Many Satellites Are We Actually Talking About?

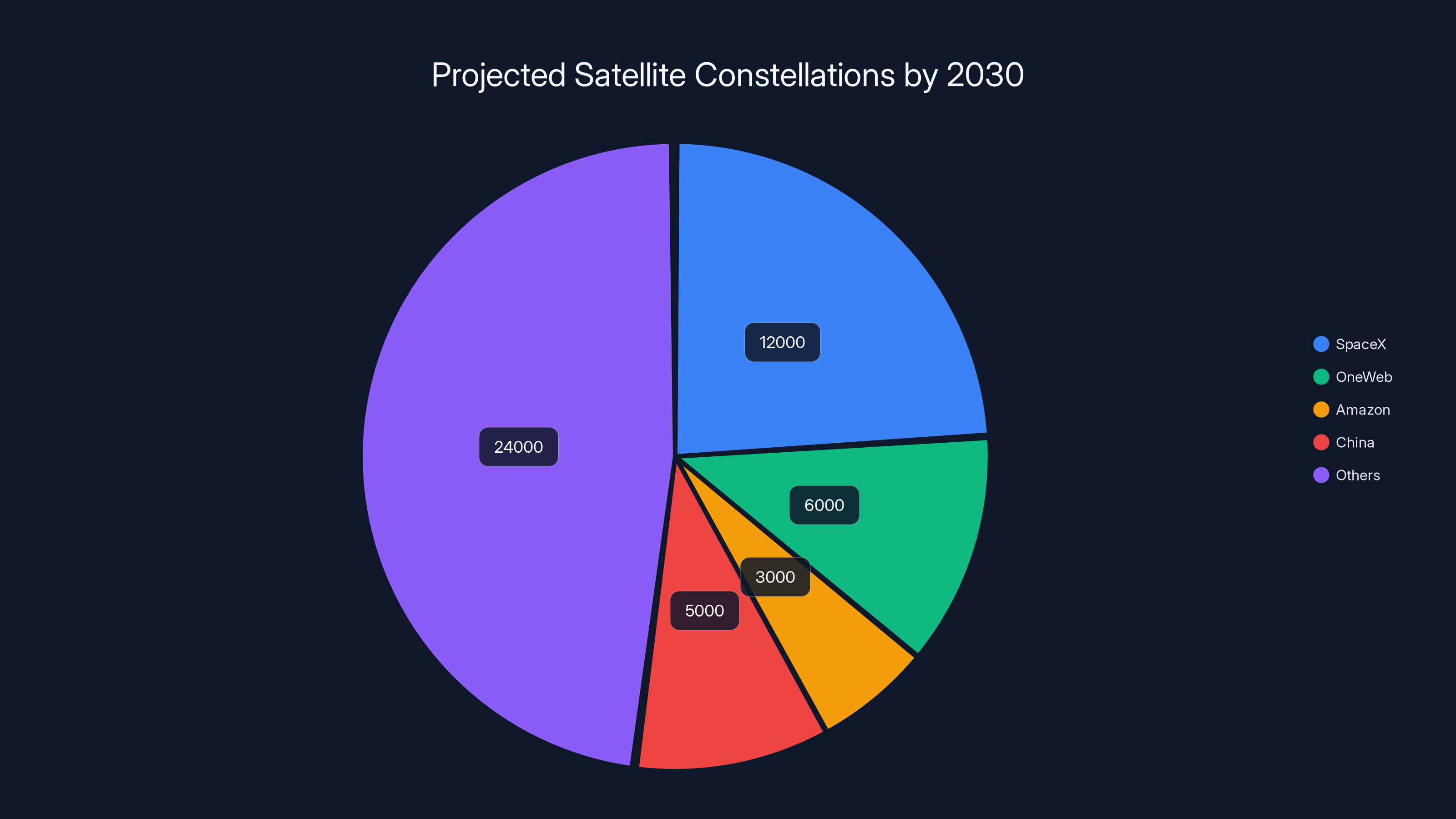

The numbers are staggering. Space X is lowering 4,400 satellites immediately. But this is just one company.

By the end of this decade, there could be anywhere from 50,000 to 70,000 satellites operating in low Earth orbit simultaneously. Space X wants roughly 12,000 Starlink satellites. One Web is building a constellation around 6,000 satellites. Amazon's Project Kuiper aims for 3,000+ satellites. China is building several constellations. The U. S. military has constellation projects. Europe has plans. India is launching its own satellite internet service.

Each constellation operates at different altitudes to avoid each other. At least in theory. In practice, that's increasingly complicated.

Imagine rush hour on I-95 between Boston and Washington. Now imagine that traffic pattern stacked at five different altitude levels, all moving at 17,500 miles per hour, with no traffic lights or speed limit enforcement, and if anything crashes, the debris creates more crashes. That's roughly what's happening in low Earth orbit right now.

Space X's move to lower 4,400 satellites is basically the company saying: "We need to get out of the congested lane and move down to the less crowded one." It's a smart play, but it only works if other companies coordinate similarly.

The Technical Challenge of Lowering 4,400 Satellites

This sounds straightforward but it's not. Each satellite needs to be individually maneuvered to a new orbital altitude. That requires fuel. It requires precise calculations. It requires command and control capability for every single satellite.

Space X designed Starlink satellites with propulsion systems specifically for orbit-raising after launch and for deorbiting at end of life. Lowering the entire constellation to a new altitude uses some of this fuel budget, which means those satellites will eventually have less fuel for other maneuvers or for active deorbiting.

The company is essentially trading off some long-term fuel reserves for immediate safety improvements. Given the collision risk, it's the right trade-off. But it's also a reminder that nothing in space operations is simple or free.

The lowering operation will take months. Not all 4,400 satellites can be maneuvered simultaneously. Each maneuver requires precise timing to avoid conflicts with other satellites or debris. Space X has to sequence these moves carefully, coordinating with satellite tracking networks and other operators to ensure no collisions occur during the transition itself.

It's like changing lanes on the highway while traveling at 17,500 miles per hour. You have to do it carefully.

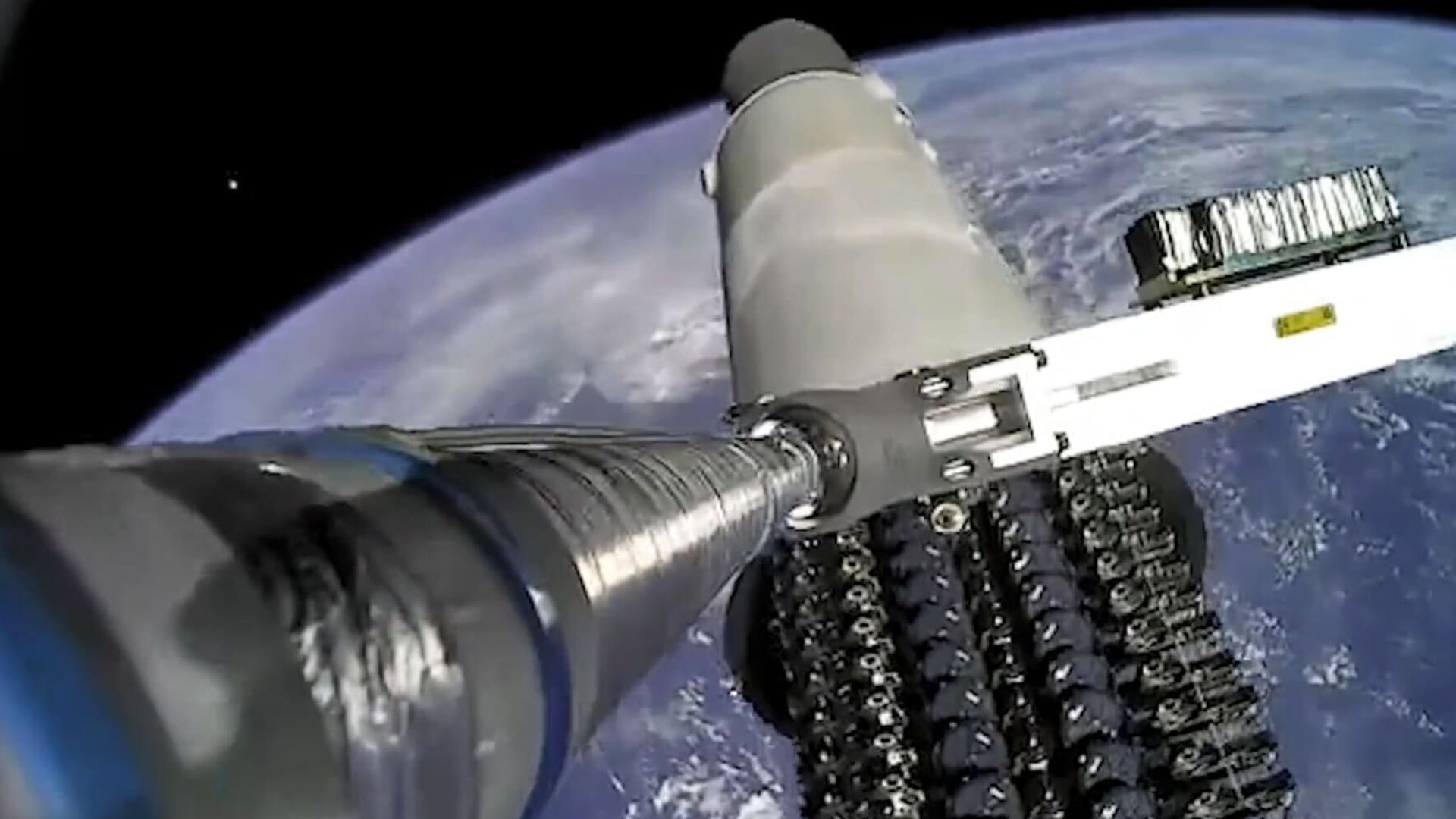

Space X's Launch Record: The Unprecedented Scale

Understanding why Space X is making this move requires understanding the scale of their operation. In 2025 alone, Space X conducted over 160 Falcon 9 missions. That's more than three launches per week. More than 120 of those missions carried Starlink satellites.

Compare that to the rest of the world. The entire space industry launches maybe 150-200 rockets per year total, globally. Space X is doing that in just Falcon 9 launches, and Falcon 9 is their "regular" workhorse. The Starship program adds even more launch capacity.

This unprecedented cadence is why Space X can move fast in orbit. It's also why they can take on a massive operational task like lowering 4,400 satellites. They have the launch infrastructure, the command and control systems, and the organizational discipline to manage it.

No other company at this scale could pull off this maneuver right now. That's partly why Amazon and One Web are moving more slowly with their constellation deployments. Launching is one thing. Operating thousands of objects in orbit simultaneously is another entirely.

At 480km, atmospheric density is 50% higher than at 550km, leading to significantly faster orbital decay (10-50x improvement). Estimated data.

What Happens to Satellites That Break: The Deorbiting Strategy

One of the biggest advantages of the lower altitude is faster deorbiting. When a satellite dies or fails catastrophically, you want it out of orbit as quickly as possible.

At 550km, this takes years. The satellite slowly descends due to atmospheric drag, but the process is glacial. Meanwhile, it's a hazard. If its electronics are still partially functional, you can't control it. If they're completely dead, you can't even boost it higher to deliberately deorbit it faster.

At 480km, atmospheric drag increases significantly. A dead satellite descends in weeks or months. That's the difference between "this will be a problem for the rest of the decade" and "this will be resolved in the near term."

For constellation operators, this is crucial. Imagine having to manage thousands of dead satellites lingering in orbit indefinitely. Now imagine that number growing because launches keep adding more satellites. You'd eventually end up with more dead satellites than active ones. That's the scenario Kessler Syndrome describes.

By moving to 480km, Space X is essentially accepting that satellites will have shorter operational lifespans but much faster deorbiting. That's a cleaner approach to space traffic management.

The Bigger Picture: Space Traffic Management Is Becoming Critical

This isn't just a Space X problem or even a satellite-internet problem. It's a systemic problem affecting the entire orbital economy.

Space agencies worldwide are now grappling with space traffic management. The FAA and U. S. Commerce Department have started regulating satellite operations. The European Space Agency is developing traffic management protocols. The International Telecommunication Union is trying to establish orbital coordination standards.

The problem is that space was never designed for this level of congestion. When the first satellites launched in the 1960s, nobody imagined there would ever be tens of thousands of them. Orbital mechanics were treated as an academic exercise, not a practical engineering problem.

Now we're discovering that orbital real estate is valuable and finite. Everyone wants it. But you can't just add an infinite number of objects without consequences.

Space X's move to lower its satellites is essentially a unilateral decision to improve its own safety posture. But it would be far better if the entire industry coordinated on altitude bands, deorbiting timelines, and collision avoidance protocols.

That coordination is starting to happen. But it's slow, and the problems are accelerating.

How Active Deorbiting Works

Most modern satellites, including Starlink, have propulsion systems for active deorbiting. When a satellite reaches end of life, it fires thrusters to slow itself down. This allows it to descend into the atmosphere deliberately rather than waiting for natural decay.

Active deorbiting is crucial because it lets operators control when and where a satellite comes down. Rather than an uncontrolled satellite potentially coming down over a populated area, you steer it to burn up over the ocean or a remote region.

Space X's satellites have fuel reserved specifically for this end-of-life burn. Lower orbit means less fuel is needed for the deorbiting burn itself, since you don't have to descend as far. This creates a efficiency gain that actually offsets some of the fuel cost of moving the entire constellation down.

However, there's a catch. Each Starlink satellite has a limited fuel budget. Using fuel to lower the orbit means less fuel is available for other purposes. Space X engineers had to calculate whether the safety benefits outweigh the long-term operational costs. Clearly, they decided the safety benefit justifies it.

By 2030, SpaceX, OneWeb, and Amazon will contribute significantly to the 50,000-70,000 satellites projected in low Earth orbit. Estimated data.

Collision Avoidance: The Cat-and-Mouse Game in Orbit

Let's talk about the scary part. How do you avoid colliding with 70,000 satellites, 34,000 pieces of tracked debris, and millions of pieces of untracked debris all traveling at 17,500 miles per hour?

You don't. Not completely. But you improve your odds.

Today, Space-Track.org provides tracking data from U. S. military sensors that monitor orbital objects. Satellite operators subscribe to services that analyze this data and predict future collision conjunctions. When a collision risk exceeds acceptable thresholds, the satellite operator maneuvers its satellite out of the way.

Space X does this regularly. Its Starlink satellites perform collision avoidance maneuvers multiple times per year. But as the number of satellites grows, the number of maneuvers grows exponentially.

Think about it mathematically. With 10,000 satellites in orbit, you have roughly 50 million possible pairs of satellites that could collide. Even if only 0.01% of those pairs pose collision risk in any given day, that's 5,000 potential conflicts per day. Across a constellation of 9,000 satellites, that means your satellites are constantly executing maneuvers.

This is unsustainable long-term. You can't keep burning fuel for endless collision avoidance maneuvers. Eventually, you run out.

By moving satellites to a less congested altitude, you reduce the number of potential conflicts. That's the strategy Space X is pursuing.

What This Means for Starlink Customers

If you're a Starlink customer, you might be wondering what this orbital reshuffle means for you.

The good news: almost nothing, in the immediate term. You'll see no service interruptions. Your latency won't change meaningfully. You'll get the same speeds you're currently getting. The satellites serving your location at any moment will change gradually as the constellation redistributes, but that happens transparently.

The medium-term implications are slightly more complex. Some Starlink satellites will be at the lower altitude, some will remain at higher orbits. This creates a mixed constellation. Space X likely did this deliberately, maintaining diversity in orbital altitudes to provide redundancy and coverage optimization.

The long-term implication is positive: your internet service becomes more reliable because the underlying infrastructure is safer. Fewer collisions mean fewer satellite losses, which means more consistent coverage and more predictable service levels.

From a customer perspective, this is Space X making invisible infrastructure improvements that increase reliability without changing your experience.

The Economics of Satellite Constellations

Running a satellite internet constellation is stunningly expensive. Each Starlink satellite costs roughly

Space X can sustain this because it's a privately held company with multiple revenue streams. The company doesn't need quarterly profits from Starlink to justify continued operation. Space X makes money from rocket launches, government contracts, and other ventures.

This gives Space X flexibility that other companies don't have. Amazon is publicly traded and accountable to shareholders. One Web is backed by investors expecting returns. For them, moving 4,400 satellites to a new altitude would require a much more complex business case.

This economic reality shapes space infrastructure development more than people realize. The companies with the most resources and the most flexibility set the norms. Space X is currently defining what responsible satellite constellation operation looks like.

SpaceX is lowering roughly half of its Starlink satellites to 480 km to reduce collision risk and ensure faster deorbiting of defunct satellites. Estimated data.

Regulatory Response and International Coordination

Governments are waking up to the space traffic problem, but they're moving slowly.

The FCC requires operators to deorbit satellites within 5 years of end of life. That sounds good until you realize that a satellite at 550km can take that long to naturally decay. So the regulation is barely binding.

New regulations are tightening. But regulation is hard when you're making it up as you go. Nobody anticipated this level of orbital congestion in the 1970s when current regulatory frameworks were written.

International coordination is even slower. Space law is governed by treaties signed in the 1960s, before any of this mattered. Updating international law requires unanimous agreement among dozens of countries with competing interests.

Meanwhile, the operational problem grows daily. Private companies are solving it faster than governments can regulate it. Space X lowering its satellites is a company making a unilateral safety decision because the government isn't forcing it to.

That's not sustainable long-term, but it's the current reality.

The Future: 70,000 Satellites and Beyond

If all current satellite constellation plans come to fruition by 2030, we'll have roughly 70,000 satellites in low Earth orbit. That's a 20x increase from today.

That level of congestion requires fundamentally different approaches to space traffic management. You can't manually plan collision avoidance for every pair. You need automated systems. You need real-time coordination. You need altitude management protocols.

Some of this is being developed. Space X is building out command and control infrastructure to manage larger constellations. Other companies are following suit. Industry groups are developing collision avoidance standards.

But there's an underlying tension: the more satellites you put in orbit, the more valuable that orbital real estate becomes. Congestion creates conflict. At some point, orbital regions will have hard capacity limits. Then what?

Possibly rate limiting. Possibly altitude restrictions. Possibly orbital slot auctions where operators pay for specific orbital zones. Possibly international agreements that limit constellation sizes.

We're entering uncharted territory. Space X's decision to lower its satellites is basically a decision to secure safety within the existing chaos. But chaos is inherently unstable.

Technical Details: Why 480km Is the Magic Number

There's nothing inherently magical about 480km. It's a strategic choice based on current constellation distributions and orbital mechanics.

About 500km is an informal boundary in the satellite industry. Below that, most operational constellations don't operate. Above that, you have more crowded lanes. By moving Starlink to 480km, the company is deliberately choosing the less crowded neighborhood.

The atmospheric density at 480km versus 550km matters enormously. The formula for atmospheric density varies exponentially with altitude. The density at 480km is roughly 50% higher than at 550km. That might not sound like much, but when you're talking about objects moving at orbital velocities, a 50% increase in drag produces enormous effects on orbital decay rates.

A satellite at 550km without propulsion takes years to decay. At 480km, it takes months. That's not a small difference. That's a 10-50x improvement in decay time depending on exact orbital characteristics.

Space X chose 480km specifically because it's below the crowded zone while still being high enough for stable long-term operations. Too low and atmospheric fluctuations become problematic. Too high and you're back in the congested zone.

Satellites at 480 km deorbit in months, significantly faster than those at 550 km or 650 km, reducing collision risk and debris longevity. Estimated data.

Space Weather and Orbital Dynamics

Here's a complication that doesn't get enough attention: space weather. The upper atmosphere expands and contracts based on solar activity.

During solar storms, the atmosphere puffs up. Satellites at 480km experience increased drag. In extreme cases, atmospheric drag can cause orbital decay that's faster than predicted. This has actually forced operators to perform unplanned orbit-raising maneuvers to keep satellites in safe orbits.

Conversely, during solar minimum when the sun is less active, the atmosphere contracts. Orbital decay slows. Satellites linger longer than expected.

This variability adds another layer of complexity to space traffic management. Operators have to maintain fuel margins to handle unexpected atmospheric changes. It's like flying an airplane with uncertain winds.

Space X's satellites at 480km will be more susceptible to space weather effects than at 550km. This was likely a factor in their engineering analysis. They probably decided that slightly faster decay from normal atmospheric drag is worth accepting the additional space weather variability.

The Role of Autonomous Systems in Space Traffic

Here's an interesting paradox. The more satellites you put in orbit, the harder it becomes to manually manage them. But the more satellites you have, the more critical it is to manage them well.

The solution being developed is autonomous collision avoidance. Instead of humans deciding whether a satellite needs to maneuver, autonomous systems analyze conjunction predictions and make decisions automatically.

Space X satellites already do this to some extent. They have onboard computers that can execute maneuvers based on ground command. But the decision-making happens on Earth.

Next-generation systems might involve onboard autonomy: satellites analyze predictions themselves and execute evasion maneuvers without waiting for ground command. This would dramatically increase response speed and reduce the computational load on ground systems.

But autonomous systems in space raise interesting questions. What if the autonomous system makes a bad decision? What if two satellites independently decide to maneuver and create a collision? These edge cases are why space operators are cautious about full autonomy.

Still, as congestion increases, full autonomy might become necessary. You can't coordinate 70,000 objects with ground-based control.

Economic Implications for Space Infrastructure

Space X's decision to lower 4,400 satellites has interesting economic implications.

First, it requires significant operational effort. Lowering that many satellites takes months and uses fuel. That's resources that could be deployed elsewhere.

Second, it signals commitment to long-term space responsibility. Companies that operate responsibly face fewer regulatory constraints and more social license to continue operations. Companies that don't face increasing restrictions.

Third, it puts competitive pressure on other operators. If Space X is operating responsibly, regulators will expect others to do the same. This could force competitors to undertake similar expensive modifications.

Fourth, it might extend Space X's competitive moat. If rivals don't have the operational capability to manage complex orbital maneuvers at scale, they're at a disadvantage. Space X's unmatched operational prowess becomes more valuable.

These aren't accidental consequences. They're likely part of Space X's calculus. The company isn't just solving a safety problem. It's positioning itself favorably in an emerging regulatory environment.

Environmental and Atmospheric Effects

Putting 70,000 satellites in orbit has environmental implications that deserve attention.

First, there's the reentry problem. As satellites deorbit, they burn up in the atmosphere. The materials don't disappear. They become particulates. Aluminum oxide is a major component of Starlink satellites, and some of it survives reentry as fine particles in the upper atmosphere.

At current volumes, this is negligible. At 70,000 satellites per generation (remember, satellites don't last forever), the cumulative particle load becomes measurable.

Second, there's the atmospheric chemistry question. The upper atmosphere is delicate. Adding significant amounts of material might have subtle effects on ozone chemistry and atmospheric dynamics. We're not sure yet. This is an active area of research.

Third, there's the light pollution problem. Satellites reflect sunlight and can appear as bright streaks in the night sky. This interferes with astronomical observations. Observatories worldwide have complained about Starlink satellites disrupting observations. Lowering satellites to 480km might actually make this worse because they're lower in the sky and appear brighter.

These environmental concerns aren't showstoppers. But they're real and they deserve serious consideration as space becomes more populated.

The Broader Vision: Space X and the New Space Economy

Space X isn't just building a satellite internet business. It's building infrastructure for a new economy.

In 10-20 years, orbit-to-ground logistics might be commonplace. Microsatellites might be manufacturing platforms. Space might be as much part of global commerce as the ocean.

But that future only exists if orbital operations are sustainable and safe. If we descend into Kessler Syndrome, if debris becomes so prevalent that new satellite launches become impossible, we've collapsed that future.

Space X's decision to lower its satellites is actually a long-term bet on the value of orbital real estate. By making orbit safer and more stable, Space X is protecting the foundation of its long-term business strategy.

That's enlightened self-interest. But it's also aligned with broader societal interests. We all benefit from a safer orbital environment.

Key Factors to Watch Moving Forward

The lowering of 4,400 Starlink satellites is a major move, but it's not the final answer to space traffic management.

Watch for whether other operators follow suit. Amazon, One Web, and others will eventually face similar pressure to demonstrate responsible orbital practices. How they respond will shape the industry.

Watch for regulatory changes. As this issue gets more attention, governments will inevitably develop new rules. The question is whether they'll be smart rules that promote responsible operation, or blunt rules that stifle innovation.

Watch for international coordination failures. If countries develop conflicting standards, orbital traffic management becomes much harder. If they coordinate, it becomes manageable.

Watch for technological solutions. Better tracking systems, better collision avoidance algorithms, better deorbiting technologies. All of these are being developed.

Most importantly, watch for the consolidation of operators. In the long term, we probably can't sustain dozens of independent satellite operators all managing their own constellations independently. We'll either see consolidation or coordination. Probably both.

FAQ

What is the main reason Space X is lowering its Starlink satellites?

Space X is lowering approximately 4,400 of its 9,000+ Starlink satellites from 550km to 480km altitude primarily to reduce collision risk with other satellites and debris, and to enable faster deorbiting when satellites fail or reach end of life. After experiencing a catastrophic satellite failure and a near-miss collision with a Chinese satellite, the company determined that operating below the 500km threshold significantly reduces hazards in increasingly congested low Earth orbit.

How long will it take for Space X to lower all 4,400 satellites to the new altitude?

The lowering operation will take several months to complete. Space X cannot maneuver all 4,400 satellites simultaneously, as this would require precise coordination with satellite tracking networks, other orbital operators, and existing debris. Each satellite must be individually repositioned using its onboard propulsion system, with moves sequenced carefully to prevent any collisions during the transition itself.

Why is the 480km altitude specifically chosen?

The 480km altitude sits below the 500km threshold where most other operational satellite constellations operate, significantly reducing collision risk with competing mega-constellations like One Web and Amazon's Project Kuiper. More importantly, atmospheric density increases exponentially at lower altitudes, causing satellites at 480km to experience approximately 50% more atmospheric drag than at 550km. This compresses deorbiting timelines from years to months or weeks, dramatically reducing the duration that inactive satellites pose collision risks.

What is space debris and why is it such a serious problem?

Space debris consists of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments from past explosions and collisions orbiting Earth at approximately 17,500 miles per hour. At these velocities, even a paint fleck can puncture a satellite. NASA tracks roughly 34,000 pieces of debris larger than 10 centimeters, but millions of smaller, untracked fragments exist. When satellites collide, they shatter into hundreds of pieces, each becoming a new collision hazard in what scientists call Kessler Syndrome—a cascading effect where collisions create debris that causes more collisions.

How does Space X avoid collisions with other satellites and debris?

Space X receives conjunction predictions from Space-Track.org, which provides tracking data from U. S. military sensors monitoring orbital objects. When predicted collision risks exceed acceptable thresholds, Starlink satellites execute automated maneuvering burns to change their orbital velocity slightly. Starlink satellites perform these collision avoidance maneuvers multiple times per year. As orbital congestion increases, the frequency of these maneuvers grows exponentially, consuming fuel and shortening satellite lifespans.

Will lowering the satellites affect Starlink internet service quality for customers?

No, Starlink customers should experience no noticeable changes in service quality. The orbital repositioning happens gradually and transparently, with different satellites operating at the lower altitude while others remain at higher orbits. Latency, speeds, and coverage remain consistent throughout the transition. The primary benefit to customers is improved long-term reliability, as fewer collision risks mean fewer unexpected satellite losses and more predictable service levels.

How many satellites could eventually operate in low Earth orbit?

By the end of this decade, industry projections suggest 50,000 to 70,000 satellites could operate simultaneously in low Earth orbit. This represents approximately a 10x increase from current levels. Space X aims for roughly 12,000 Starlink satellites, One Web is building 6,000+ satellites, Amazon's Project Kuiper targets 3,000+ satellites, and multiple government and international efforts are launching additional constellations, all competing for orbital real estate.

What is Kessler Syndrome and should we be worried about it?

Kessler Syndrome, named after NASA scientist Donald Kessler, describes a cascading cascade effect where satellite collisions create debris that collides with other satellites, exponentially multiplying debris. While we're not in full Kessler Syndrome territory yet, we're moving toward higher collision frequencies. Space X's decision to lower its satellites addresses this risk by moving to a less congested altitude with faster debris decay. However, with 70,000 satellites potentially in orbit by 2030, Kessler Syndrome remains a serious long-term concern requiring aggressive space traffic management.

How does fuel use affect satellite lifespan?

Every maneuver—whether collision avoidance or orbital repositioning—burns propellant that each satellite carries for specific purposes: orbit adjustments after launch, collision avoidance throughout operation, and active deorbiting at end of life. Space X's decision to lower 4,400 satellites uses some of this fuel budget, slightly reducing reserves for future maneuvers. However, operating at 480km with faster natural decay means satellites need less fuel for the final deorbiting burn, offsetting some of this cost. Operators must carefully balance fuel allocation against operational needs.

What role does regulation play in space traffic management?

Government regulation is lagging operational reality. The FCC requires operators to deorbit satellites within 5 years of end of life, which barely constrains operators at 550km where natural decay takes years. Newer regulations are tightening, but regulatory frameworks were written in the 1960s and 70s, before mega-constellations became conceivable. Space X's decision to lower satellites is largely voluntary—the company is making a unilateral safety choice rather than responding to regulatory mandate. This dynamic reflects how private innovation sometimes outpaces government policy.

Conclusion

Space X's decision to lower 4,400 Starlink satellites might seem like a routine operational tweak. But it's actually a significant statement about the future of space operations and Space X's commitment to long-term orbital sustainability.

The company is essentially saying: we understand that low Earth orbit is a shared resource that's becoming congested. We're taking steps to reduce our contribution to the collision risk problem. We're moving below the crowded zones. We're enabling faster deorbiting. We're being a responsible operator.

This move also reveals the tension at the heart of the emerging space economy. On one hand, there's enormous value in orbital real estate. Satellite internet serves millions of people. Satellite technology enables GPS, weather forecasting, disaster response, and countless other critical services. On the other hand, orbit is finite. You can't add infinite satellites without consequences.

Space X's answer is to optimize aggressively. Manufacture satellites at scale. Launch at unprecedented frequency. Operate at extreme efficiency. Manage thousands of objects in space with precision. And when problems emerge, respond decisively with moves like lowering an entire constellation.

No other company currently has the operational capability to pull off what Space X just committed to doing. That's partly a technology advantage. But it's mostly an organizational capability advantage. Space X has built the infrastructure and developed the expertise to manage space operations at a scale that nobody else can match.

Will other operators follow suit? Will they lower their constellations? Will they match Space X's commitment to space safety? Probably eventually. But probably only after regulatory pressure forces them to.

The ideal outcome would be international coordination around optimal orbital altitudes, deorbiting standards, and collision avoidance protocols. That would be far more efficient than each operator making unilateral decisions.

But that's slow and hard. In the meantime, Space X is solving the problem through sheer operational excellence. That's not a sustainable long-term answer. But it buys time for the regulatory and diplomatic systems to catch up.

For now, that's how innovation works in space. Private companies move fast. Regulators follow. International treaties lag behind by decades. The result is a patchwork of voluntary standards, regulatory requirements, and corporate decisions.

It's not perfect. But it's working well enough to keep orbit functional. And moves like this—lowering satellites to safer altitudes, enabling faster deorbiting, reducing collision risk—are exactly what it takes to keep it that way.

The future of space is being written right now, with decisions made by engineers at Space X and other operators. Understanding these decisions, and understanding the orbital mechanics behind them, is essential to understanding the future of technology, communication, and humanity's relationship with space.

Space X is lowering its satellites. And in doing so, it's raising the bar for what responsible space operation looks like.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX is lowering approximately 4,400 Starlink satellites from 550km to 480km altitude over the coming months to reduce collision risk and enable faster deorbiting

- Lower altitudes experience exponentially greater atmospheric drag, compressing satellite decay timelines from years to months and significantly reducing debris persistence in orbit

- NASA tracks 34,000+ pieces of orbital debris larger than 10cm, with millions of smaller untracked fragments creating collision hazards at orbital velocities of 17,500 mph

- By 2030, projected satellite constellations could total 50,000-70,000 objects in low Earth orbit, requiring sophisticated space traffic management systems to prevent Kessler Syndrome

- SpaceX's unprecedented operational capability—160+ launches in 2025—enables complex constellation maneuvers that competitors lack, positioning the company as a leader in responsible space operations

Related Articles

- Samsung Freestyle Plus Projector: Brightness Specs Explained [2025]

- Best Gaming Laptops for School & Gaming [2026]

- Petkit's AI Wet Food Feeder & Smart Water Fountain [2025]

- How Arya.ag Stays Profitable While Commodity Prices Fall [2025]

- Dyson Vacuum Design Philosophy: Engineering Comfort & Power [2025]

- Brooks Promo Codes & Deals: Save 20% on Running Shoes [2025]