Space X's 15,000 Starlink Gen 2 Satellites: What It Means [2025]

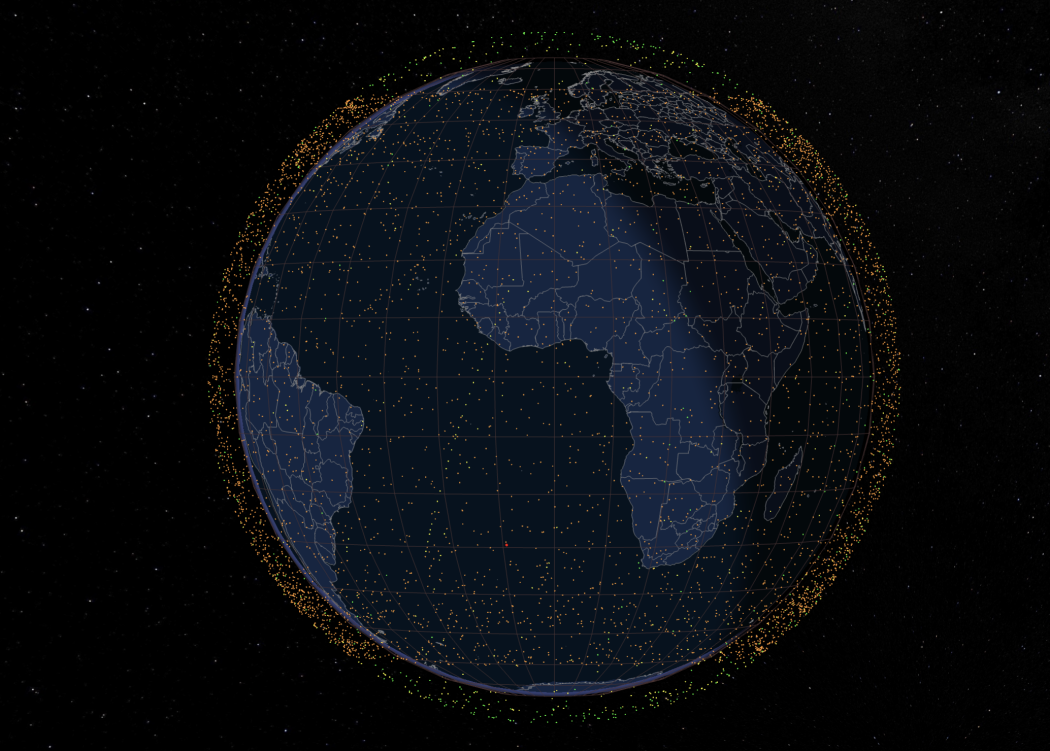

Space X just pulled off something most companies can only dream about. The FCC approved another 7,500 second-generation Starlink satellites, doubling the company's authorized Gen 2 constellation to 15,000 satellites. That's not a typo. Fifteen thousand.

If you're wondering what that actually means beyond the headline, you're asking the right question. This isn't just a bigger number. It's a fundamental shift in how global internet infrastructure works, who controls it, and what happens when one company gets this much orbital real estate.

Let's break down what just happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- Space X now has authorization for 15,000 Gen 2 Starlink satellites, up from the original 7,500 approved in December 2022

- The FCC expanded coverage capabilities to include fixed and mobile service across multiple frequency bands (Ku-, Ka-, V-, E-, and W-band)

- Mobile supplemental coverage is now approved globally, enabling direct-to-smartphone internet service like the T-Mobile partnership in the US

- Competition is escalating, with Viasat, Globalstar, and other operators filing formal objections to prevent market foreclosure

- A third mega-constellation is coming, with Space X requesting approval for another 15,000 mobile-optimized satellites, potentially totaling 30,000 satellites in orbit

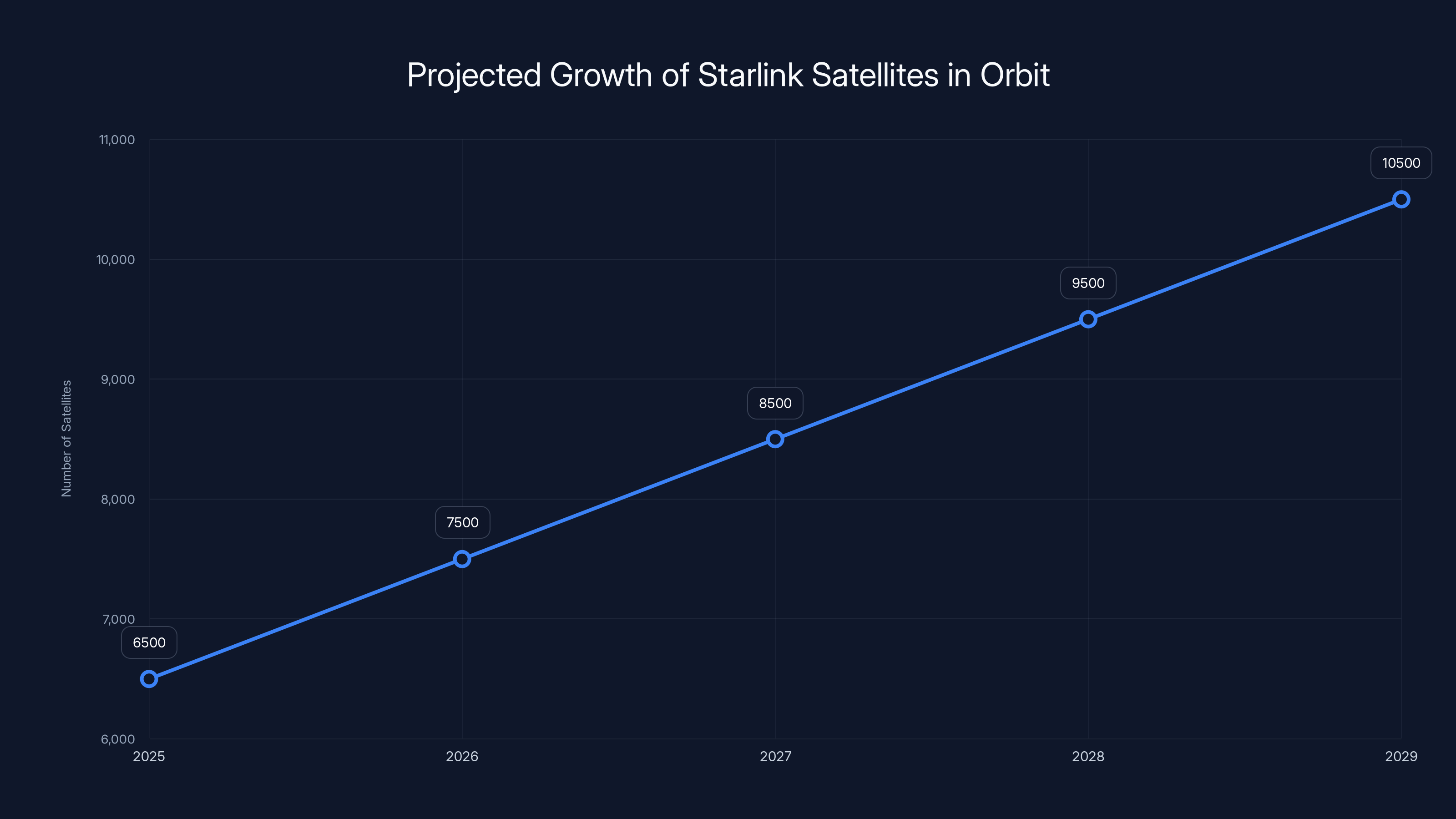

Starlink's satellite constellation is projected to grow steadily, potentially reaching over 10,000 satellites by 2029. Estimated data based on current deployment rates.

What Just Happened: The FCC's Latest Authorization

On January 2025, the FCC announced its decision to authorize Space X to construct, deploy, and operate an additional 7,500 second-generation Starlink satellites. This brings the total authorized Gen 2 constellation to 15,000 satellites worldwide.

The approval itself is a big deal, but what's buried in the FCC's technical order is even more significant. The commission waived several "obsolete requirements that prevented overlapping beam coverage and enhanced capacity." Translation: Space X can now do things with these satellites that the original 2022 authorization explicitly forbade.

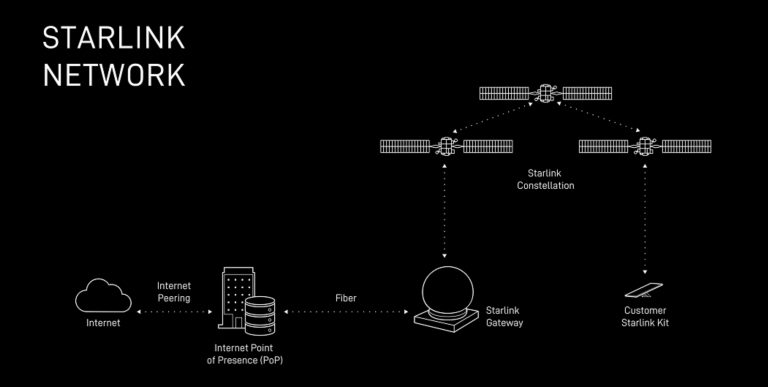

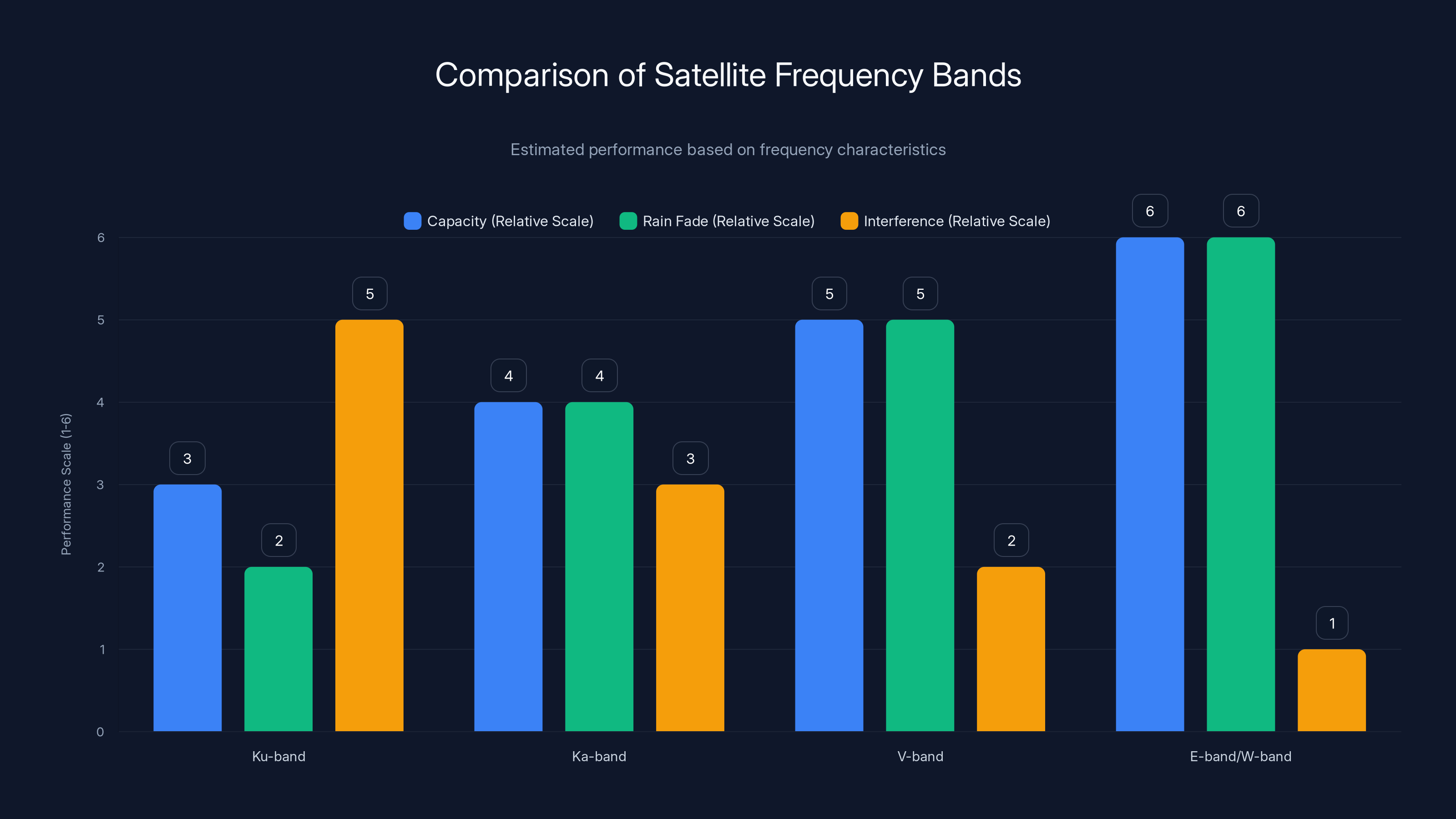

The company can now operate across five frequency bands simultaneously. Ku-band, Ka-band, V-band, E-band, and W-band. Each band serves different purposes. Ku and Ka are the primary broadband bands. V, E, and W are newer allocations that provide higher capacity but are more prone to rain fade. The ability to operate across all of them means Starlink satellites can now flexibly route traffic depending on demand and weather conditions.

But here's the constraint nobody's talking about: the approval came with altitude changes. Space X is required to lower approximately 4,400 of its existing satellites from 341 miles (550 kilometers) to 298 miles (480 kilometers) during 2026. Space X proposed this itself, arguing that lower altitudes mean less debris risk and faster deorbiting if something goes wrong. From an orbital mechanics perspective, that's solid reasoning. Lower orbits have shorter natural decay times. A satellite at 298 miles will naturally fall back to Earth in about 5 to 10 years if it goes silent. A satellite at 341 miles might take 15 to 20 years.

The FCC also authorized new orbital shells at altitudes ranging from 340 km to 485 km. This gives Space X significant flexibility in satellite placement. Different altitudes mean different coverage characteristics. Lower satellites have smaller coverage footprints but lower latency. Higher satellites cover more ground but add latency. Having multiple shells lets Space X optimize for both.

Mobile Broadband is Now Global

The original 7,500 Gen 2 satellites approved in December 2022 had a major limitation: they couldn't provide mobile service. The FCC restricted them to fixed satellite service only. That meant Starlink could provide home internet and business connectivity, but not direct-to-smartphone service.

In November 2024, the FCC reconsidered and approved Supplemental Coverage from Space (SCS) for the original 7,500 satellites. This opened the door for T-Mobile's partnership, where Starlink satellites fill coverage gaps when you're outside cellular range. You text via satellite. You don't need a special phone. It just works through your regular SCS-enabled device.

The new authorization extends this capability to all 15,000 Gen 2 satellites globally. Not just in the US. Not just for T-Mobile. Every satellite in the constellation can now provide both fixed and mobile service simultaneously.

Why does this matter? Because mobile broadband is the harder problem. Fixed broadband, you're sitting at a desk or building. The antenna points at the sky. The bandwidth budget is generous. Mobile service means you're holding a phone with a tiny antenna, moving around, going through obstacles. The power and data demands are completely different.

Globalsat had been providing handheld satellite phones for years through its dedicated satellites. Iridium pioneered the space. But those systems had major limitations. Coverage was inconsistent. Latency was high. Data speeds were glacial. Starlink's capability to provide modern broadband speeds to moving smartphones is genuinely novel. It changes what's possible.

T-Mobile isn't the only partner either. Starlink has deals with carriers in multiple countries. The authorization now extends those capabilities globally. For a country with poor terrestrial infrastructure, this is significant. Starlink becomes a viable backup network.

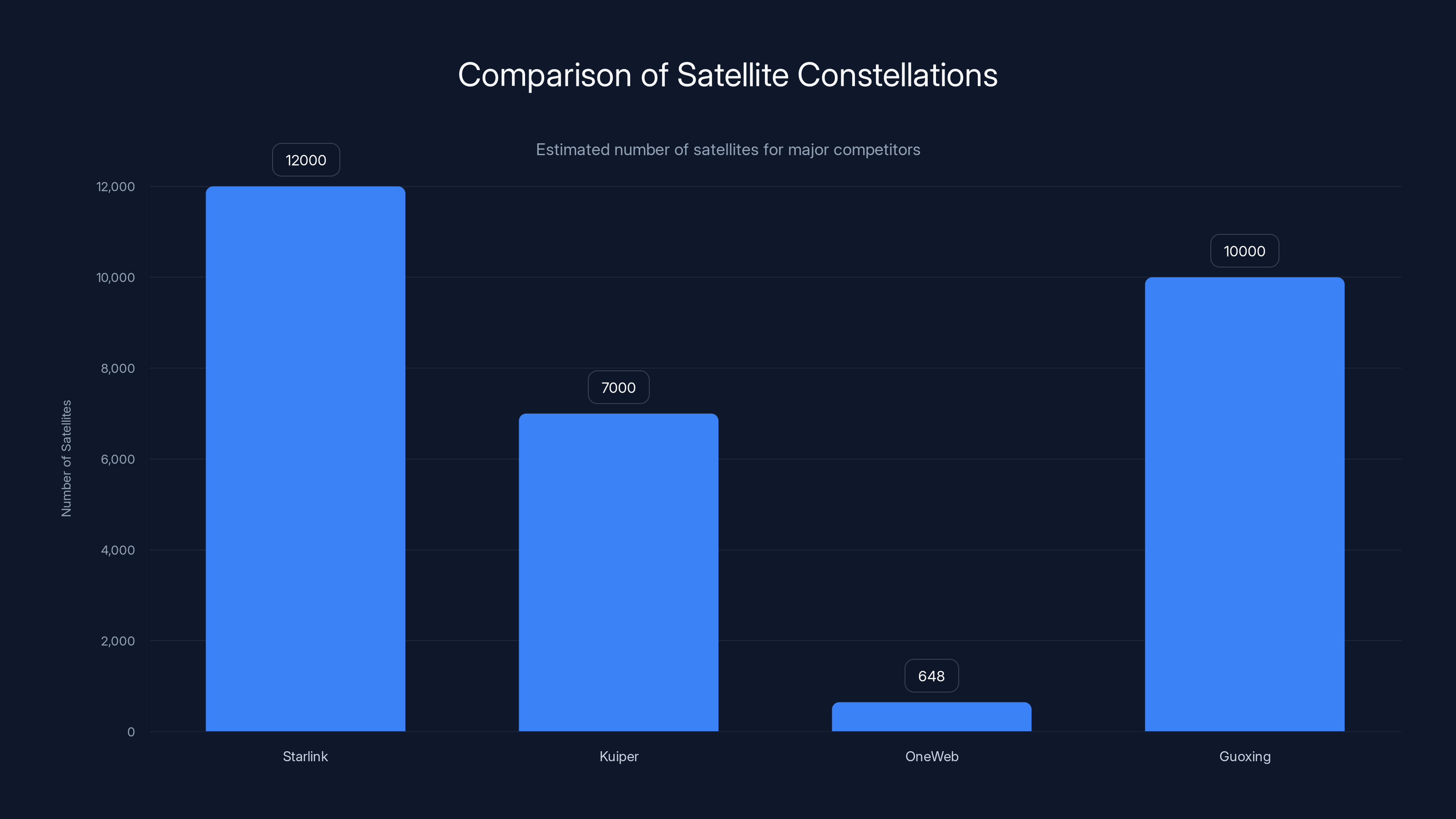

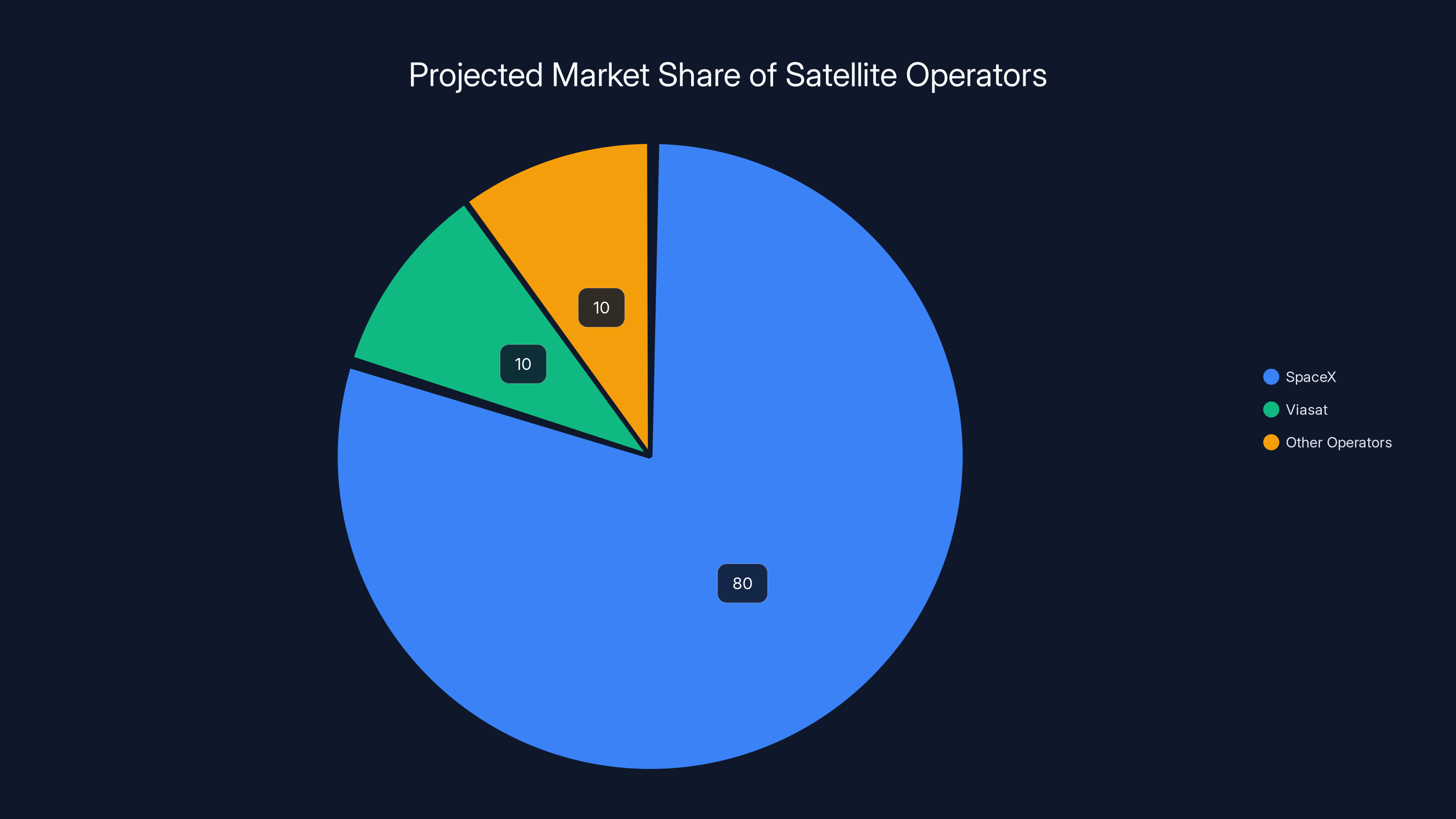

Starlink is projected to have the largest satellite constellation, with an estimated 12,000 satellites, giving it a significant first-mover advantage. (Estimated data)

The Spectrum Deal That Changes Everything

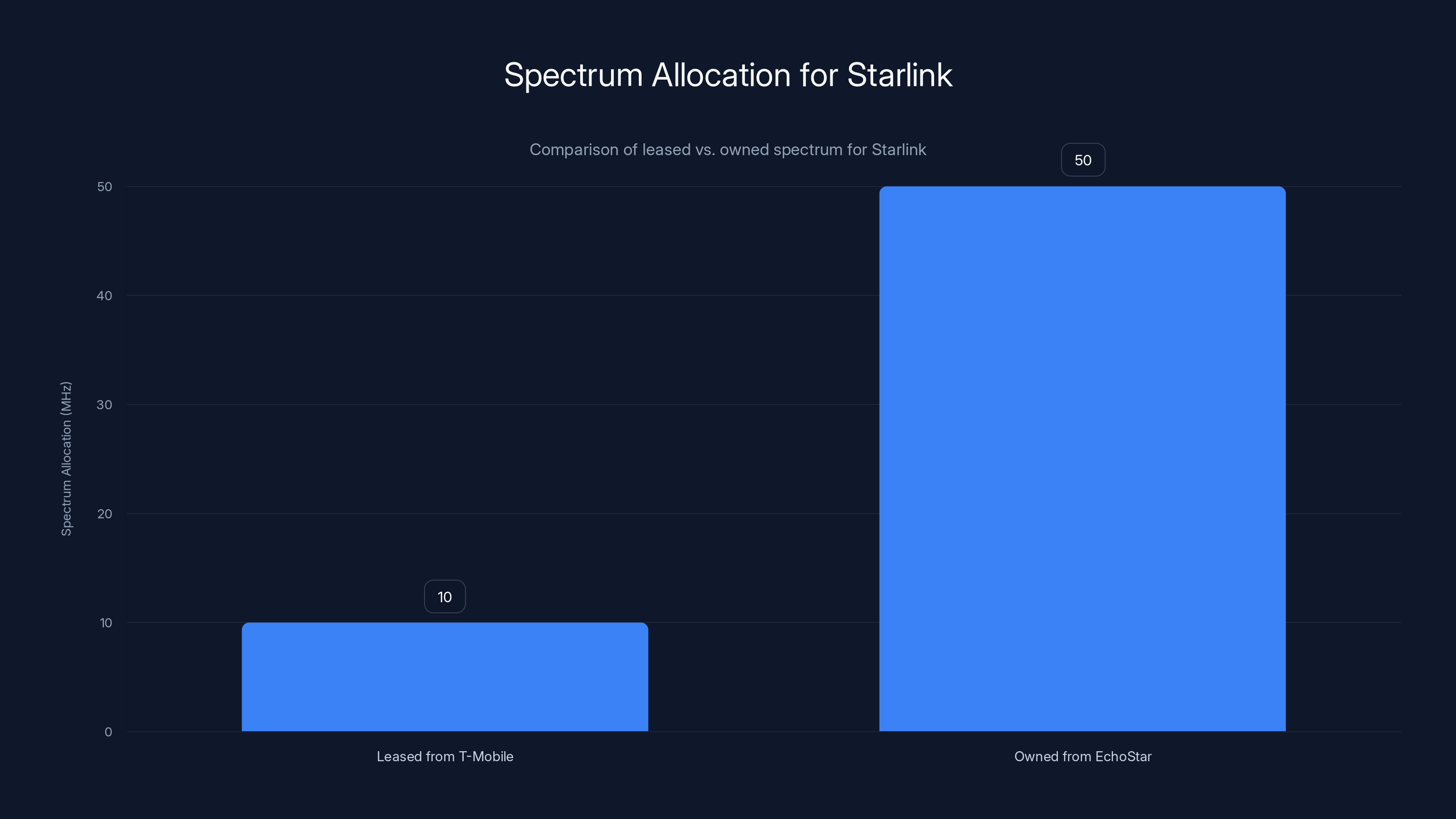

Space X recently closed a $17 billion deal to buy spectrum licenses from Echo Star. This wasn't a headline-grabbing acquisition. It was a fundamental restructuring of Starlink's operating model.

Here's the setup. Starlink currently leases 10 MHz of mobile spectrum from T-Mobile to provide supplemental coverage in the US. That's a working partnership, but it makes Starlink dependent on T-Mobile's cooperation. Buying spectrum licenses from Echo Star gives Space X 50 MHz of mobile spectrum outright. Ownership, not a lease.

What does 50 MHz actually mean in practical terms? More capacity, primarily. Mobile networks allocate spectrum in chunks. More spectrum means more simultaneous users. It also means less reliance on terrestrial carriers for supplemental coverage. Starlink becomes a primary mobile service option, not just a backup.

The FCC Chairman, Brendan Carr, played a central role in pressuring Echo Star into selling these licenses to Space X. Carr has been a consistent supporter of Space X and Elon Musk, and has been critical of what he views as regulatory overreach by the Biden administration. In his announcement of the latest authorization, Carr stated that "the FCC has given Space X the green light to deliver unprecedented satellite broadband capabilities, strengthen competition, and help ensure that no community is left behind."

That language is important. It signals that the FCC's regulatory stance has shifted. Under the previous administration, satellite expansions faced more scrutiny around orbital debris, spectrum interference, and competitive impacts. That scrutiny hasn't disappeared, but it's clearly been recalibrated in Space X's favor.

The Competition Problem

None of this is happening in a vacuum. Other satellite operators are watching, and they're filing formal objections with the FCC.

Viasat filed a petition to deny the expansion just this week. Their argument is straightforward: Space X already dominates the satellite internet market. Giving them 15,000 additional satellites "would give it an even greater ability and incentive to foreclose other operators from accessing and using limited orbital and spectrum resources on a competitive basis."

That's not hyperbole. Starlink already has over 6,000 satellites in orbit. Add 15,000 more and you're talking about a constellation larger than everything else combined. Viasat specifically highlighted that Starlink's expansion would "generate insurmountable interference risks for other spectrum users and the customers they serve, preclude other operators from accessing and using scarce spectral and orbital resources on an equitable basis, and undermine and foreclose competition and innovation."

Globalstar also filed a petition to deny. Several other satellite operators raised formal objections. These aren't frivolous complaints. Spectrum is genuinely scarce. Orbital slots are genuinely limited. The interference risk from a mega-constellation is genuine.

But here's the political reality. FCC Chairman Carr is friendly to Space X. The current administration appears friendly to Space X. The competitive objections may be technically valid, but the regulatory winds are blowing in Starlink's favor. That doesn't mean the concerns are baseless. It means the FCC has decided to prioritize Space X's expansion goals over competitive concerns.

Space X's argument, which the FCC apparently accepts, is that global internet coverage is important enough to justify giving one company significant orbital dominance. Universal broadband access. That's the value proposition. Whether you buy that argument probably depends on whether you trust Space X to not abuse that dominance and whether you think there are other ways to achieve the same coverage goals.

The Third Constellation Question

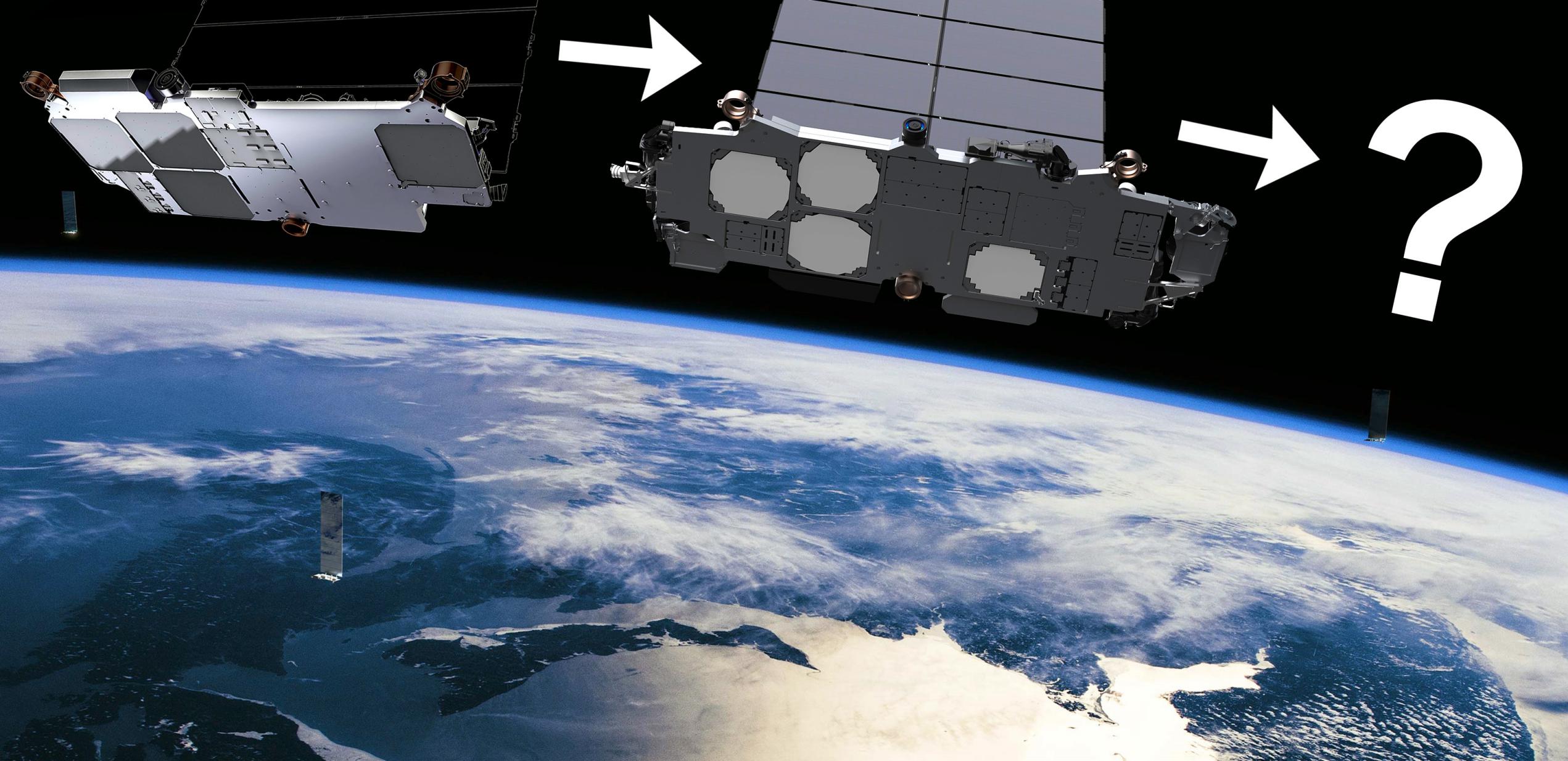

Remember that line about "another 15,000 satellites"? That wasn't speculation. Space X filed an official request with the FCC in September 2025 asking for authorization to launch yet another 15,000 satellites.

These satellites would be different. They're designed specifically for mobile service. Voice, texting, high-speed data. The form factors, power systems, and antenna configurations would all be optimized for direct-to-smartphone connectivity rather than fixed broadband.

If the FCC approves this request, Space X would be authorized to deploy 30,000 total satellites across two mega-constellations. Think about that number. Thirty thousand satellites in low Earth orbit, all operated by a single company.

For context, the entire history of spaceflight before 2020 had launched maybe 6,000 to 7,000 satellites total. Space X would be proposing to more than quadruple that in a single constellation.

The orbital mechanics of this scale are staggering. You're talking about satellite traffic management at a scale that doesn't currently exist. Collision avoidance becomes exponentially more complex. The amount of space debris generated by even 1% of these satellites failing becomes a genuine threat to other space operations.

This is why Viasat and other competitors are pushing back. At 15,000 satellites, Space X is the dominant player. At 30,000 satellites, Space X isn't just dominant. It's the entire market. Other players become peripheral.

Will the FCC approve the third constellation? Based on current regulatory momentum, probably. FCC Chairman Carr seems committed to Space X expansion. But the process will be contentious. You'll see more formal objections. More technical analysis of interference risks. More arguments about competitive foreclosure.

The real question isn't whether Space X will get approval. It's whether the FCC will impose any meaningful conditions. Will they require Space X to lease spectrum to competitors? Will they impose interoperability requirements? Will they limit certain frequency bands? Or will the approval be essentially unencumbered?

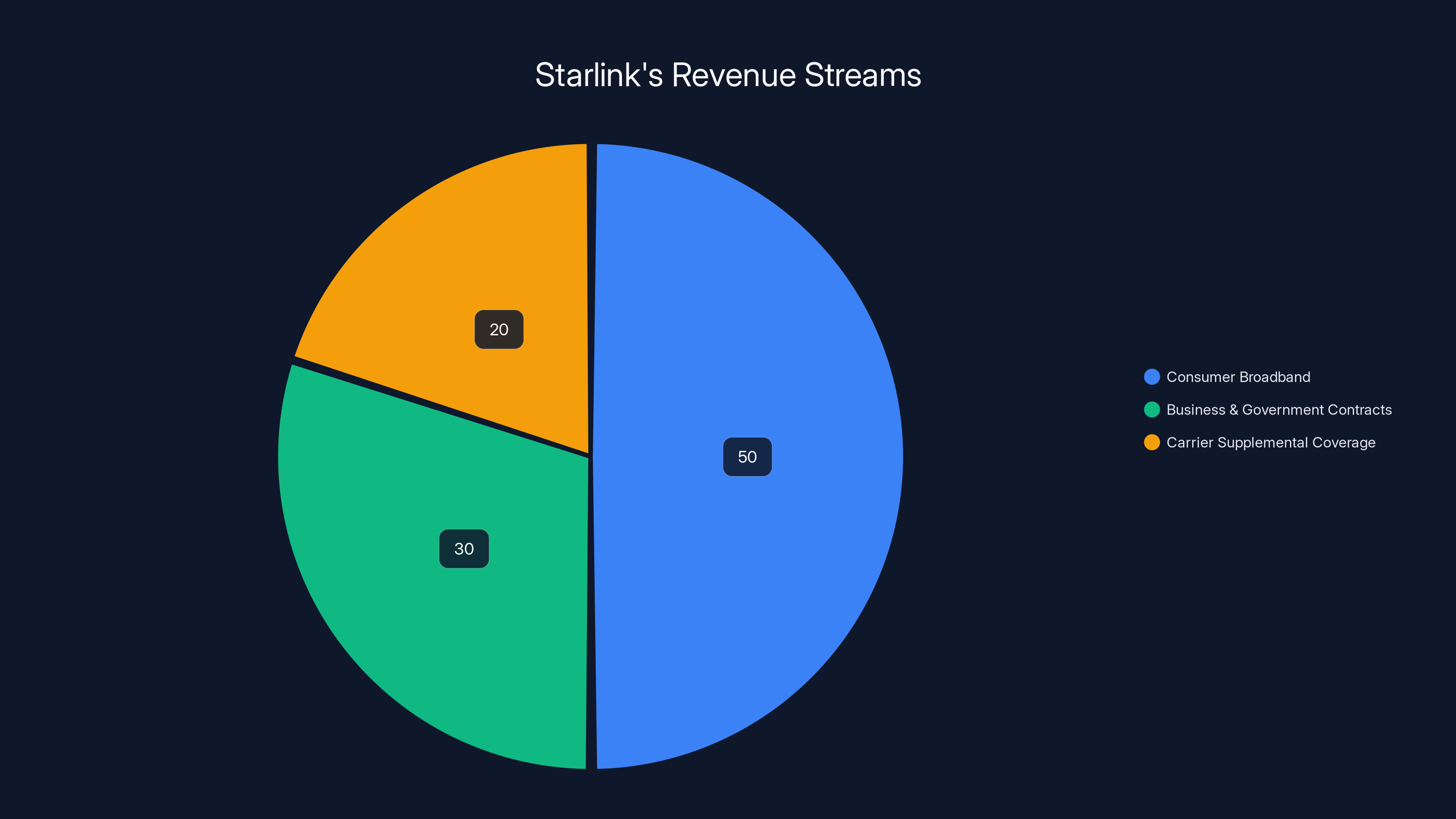

Consumer broadband is estimated to be the largest revenue stream for Starlink, followed by business and government contracts, and carrier supplemental coverage. Estimated data.

Orbital Mechanics and Altitude Considerations

Let's zoom in on the technical details of orbital altitude, because this is where the real constraints live.

Space X's satellites operate in low Earth orbit. The original constellation launched at approximately 550 kilometers altitude. The new authorization allows satellites between 340 and 485 kilometers.

Why does altitude matter so much? Everything in orbital mechanics scales with altitude. Higher orbits mean longer orbital periods. A satellite at 341 km completes an orbit roughly every 90 minutes. A satellite at 485 km might take 95 minutes. That seems trivial, but when you're managing coverage for a global constellation, orbital timing is critical.

Higher altitudes also mean larger coverage footprints. A satellite at 485 km can see a larger portion of Earth's surface than one at 341 km. That sounds better, but it comes with a cost: higher latency. The signal has farther to travel. Not a huge difference in absolute terms, but enough to matter for real-time applications.

The move to lower altitudes that Space X is proposing for existing satellites reflects lessons learned. Lower orbits mean faster deorbiting. If a satellite loses power, it naturally falls back to Earth in 5 to 10 years instead of 15 to 20 years. From an orbital debris perspective, that's significant.

Lower orbits also mean more frequent passes over the same location. That improves coverage consistency. But it also means you need more satellites to maintain continuous coverage. This is the fundamental trade-off in constellation design.

Space X's multi-shell authorization lets them optimize across these trade-offs. They can deploy satellites at different altitudes, each serving specific purposes. Lower shells for coverage. Higher shells for capacity and redundancy.

The physics here is important because it sets hard constraints on what's possible. You can't just approve 30,000 satellites without understanding the orbital mechanics. Each satellite occupies orbital space. Each one has a collision risk with every other satellite in nearby orbits. The maneuver complexity scales with the number of satellites in the constellation.

Space X has invested heavily in automated collision avoidance systems. Their satellites can autonomously perform maneuvers to avoid potential collisions with other satellites or debris. But the more satellites in orbit, the more constantly those systems are working.

Frequency Bands and Technical Capabilities

The technical order approving the constellation expansion includes a crucial detail: authorization to operate across multiple frequency bands simultaneously. Ku-band, Ka-band, V-band, E-band, and W-band.

Why multiple bands? Because they have different characteristics and different regulatory allocations.

Ku-band (12-18 GHz): The workhorse band for satellite communications. Global allocations, mature technology, proven performance. Starlink uses Ku-band for primary broadband delivery. The downside is congestion. Everyone uses Ku-band. Interference is a real concern, particularly from terrestrial networks operating in the same frequency range.

Ka-band (27-40 GHz): Higher capacity than Ku-band. Frequencies are more abundant. The tradeoff is rain fade. Ka-band signals are more easily attenuated by rain and atmospheric water vapor. That's why you typically see Ka-band used for secondary capacity or in regions with drier climates.

V-band (40-75 GHz): Even higher capacity. Even more rain fade. V-band is useful in specific geographic regions and for backhaul capacity, where the ability to transmit massive amounts of data over point-to-point links is more valuable than ubiquitous coverage.

E-band and W-band (70+ GHz): Ultra-high frequency bands used primarily for backhaul and inter-satellite links rather than ground connections. These bands can transmit enormous amounts of data, but the range is limited and atmospheric attenuation is severe.

Space X's constellation can now dynamically allocate traffic across these bands based on demand and atmospheric conditions. If Ka-band is saturated in a region, traffic can be routed to V-band. If a storm is causing rain fade on certain frequencies, the system can shift to different bands.

This flexibility is what the FCC was referring to when they said Space X could now provide "enhanced capacity" and that they were waiving "obsolete requirements that prevented overlapping beam coverage."

The original 7,500 Gen 2 authorization had more restrictive beam patterns. Satellites were essentially assigned to specific coverage areas. The new authorization lets satellites create overlapping coverage patterns, flexibly shifting capacity where it's needed.

This is computationally intensive. It requires sophisticated network management systems. But it's also what enables Starlink to potentially serve global demand without doubling the constellation size.

Global Coverage Implications

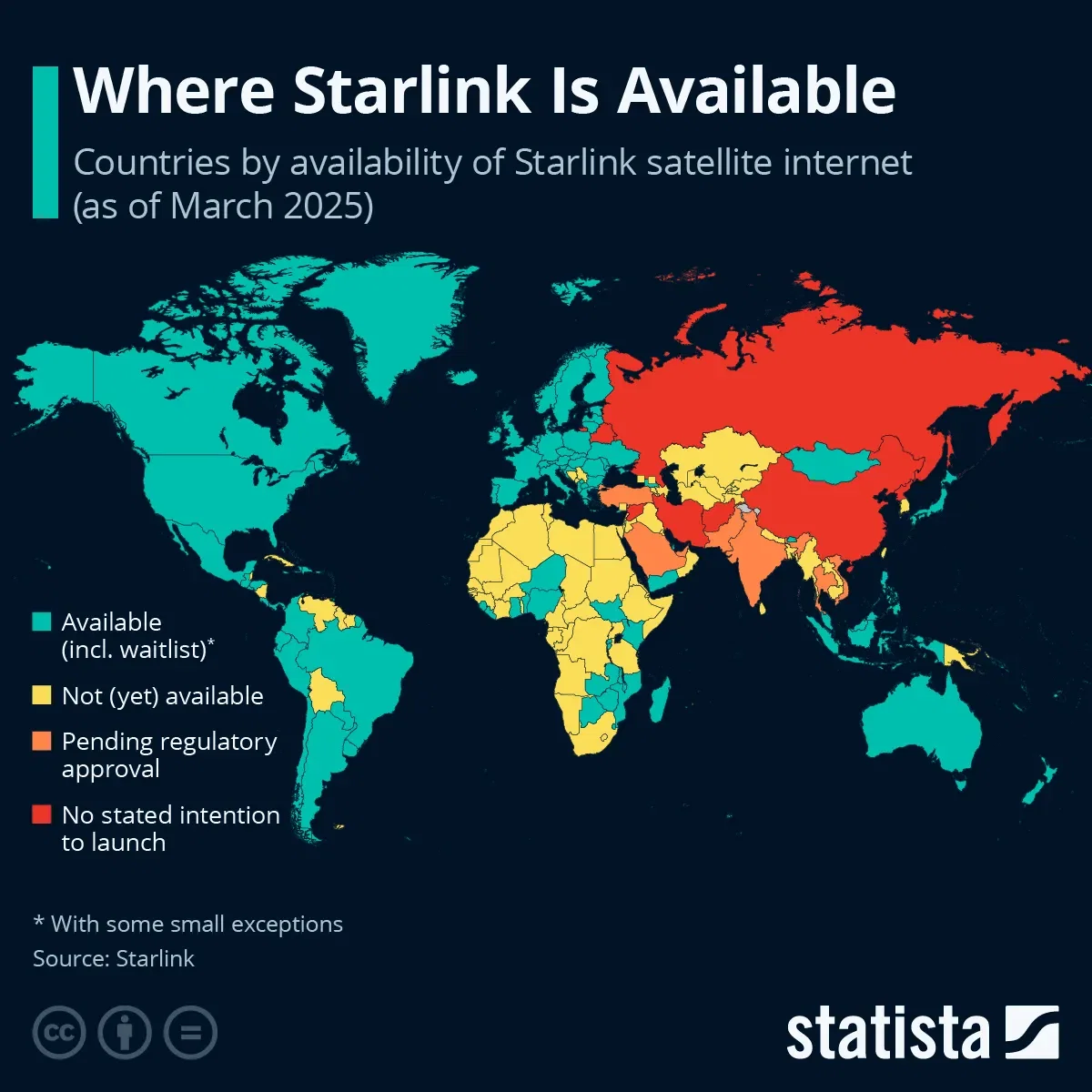

The authorization extends Starlink's mobile service capabilities worldwide. That's not a small thing.

In developed countries with mature terrestrial networks, Starlink becomes a redundancy option. If cellular networks go down, Starlink covers. If you're outside network coverage, Starlink covers. It's supplemental but valuable.

In developing countries with sparse terrestrial infrastructure, Starlink potentially becomes the primary broadband option. There's no need to build out extensive tower networks if satellite coverage is available. The infrastructure already exists. Space X's satellites are the network.

That has profound implications for digital equity. A small village that would take years to get terrestrial broadband can get satellite broadband today. The upside for global connectivity is significant.

The downside is dependency. If Space X is the primary internet provider in a region, they have significant power over digital access. Pricing, content moderation, service availability. All of that becomes centralized.

It also becomes geopolitical. Space X is a US company. Starlink satellites are managed from US ground stations. If international tensions arise, could Space X be pressured to restrict service in certain countries? Could foreign governments pressure Space X in other ways? These aren't hypothetical concerns. They're real governance questions that don't have obvious answers.

The FCC's approval of global mobile coverage doesn't address these issues. They're regulatory questions, not technical ones. But they'll become increasingly important as Starlink's service footprint expands.

Estimated data shows SpaceX could control 80% of the satellite market with 30,000 satellites, overshadowing competitors like Viasat.

What About Starlink Competitors?

Amazon is building Kuiper, a competing mega-constellation. Last public count had Kuiper at around 3,000 satellites approved, with plans for up to 7,000. That's barely a third of what Starlink will have when the Gen 2 constellation is complete.

One Web was building a competing constellation but ran out of money and was acquired by Bharti Global and the Indian government. It's still operating, but it's smaller than Starlink.

Viasat and Intelsat operate traditional geostationary satellites. They have excellent coverage and mature technology, but geostationary orbits are only 36,000 kilometers up. That means high latency, around 550 milliseconds round trip. Starlink's low Earth orbit latency is under 50 milliseconds. That's a fundamental performance advantage.

China is building its own mega-constellation called Guoxing. The details are less public, but reports suggest similar scale and capability to Starlink.

So there is competition. But Starlink's timeline advantage and FCC support means it will reach full scale first. By the time Amazon's Kuiper is fully deployed, Starlink will have an operational network that's two or three times larger.

The market will likely support multiple mega-constellations. Global bandwidth demand is enormous and growing. But Starlink's first-mover advantage and regulatory support give it a commanding position.

Orbital Debris and Space Safety Concerns

The FCC's original hesitation about approving the full Gen 2 constellation centered on orbital debris concerns. More satellites mean more potential collisions. More collisions mean more debris. More debris means higher collision risks for everyone.

This isn't abstract. In 2021, a Chinese anti-satellite test created thousands of debris fragments. In 2009, Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251 collided, generating thousands of additional debris pieces. These events matter because debris travels at orbital velocities. A 1-kilogram piece of debris traveling at 17,500 miles per hour carries the kinetic energy of a large explosive.

Space X's mitigation strategy focuses on three things. First, autonomous collision avoidance. Satellites actively detect and avoid potential collisions. Second, controlled deorbiting. At end of life, satellites are maneuvered to fall back to Earth rather than remaining in orbit as debris. Third, orbital altitude management. Lower orbits naturally decay faster, so debris from lower orbits poses less long-term risk.

The FCC seems satisfied that these measures are adequate. They approved the expansion without imposing additional debris mitigation requirements. Whether that's the right call depends on your risk tolerance and your trust in Space X's execution.

One concern that doesn't get enough attention: what happens if Space X goes bankrupt or stops maintaining the constellation? The autonomous collision avoidance systems require operational satellites. If Starlink suddenly becomes economically unviable and Space X abandons the network, 15,000 non-maneuvering satellites in orbit becomes a debris problem.

That's an edge case, but not an impossible one. Satellite internet is capital intensive and the competitive landscape is shifting. Space X has other revenue sources and Elon Musk's resources backing it, but companies fail. Government backup plans for constellation maintenance would be prudent, but I don't see that discussion happening at the FCC.

Space X is planning to lower 4,400 existing satellites in 2026, which does address the debris concern somewhat. Lower orbits decay naturally, meaning debris is eliminated faster. But 30,000 satellites is still an unprecedented orbital population. The long-term implications are hard to predict.

Space X's Business Model and Economics

Understanding why Space X is expanding this aggressively requires understanding the business model.

Starlink has three revenue streams. First, consumer broadband. Monthly subscriptions from residential customers. Second, business broadband. Government contracts, enterprise customers, maritime and aviation customers. Third, supplemental coverage. Revenue from carrier partnerships like T-Mobile.

Consumer broadband is the largest segment, but it's also the most competitive. Price pressure is inevitable as alternatives arrive. Starlink needs to hit scale quickly, establish customer lock-in, and establish brand loyalty before competition intensifies.

Business and government contracts are higher margin. The US military is a significant customer. Maritime and aviation industries pay premium prices for connectivity in remote areas. Establishing dominance in these segments requires network reliability and global coverage.

Carrier supplemental coverage is potentially huge. If every major mobile carrier globally is using Starlink for coverage gaps, that's recurring revenue. But it requires scale. One carrier using one satellite system isn't compelling. Global coverage with billions of potential customers is.

This explains the aggressive expansion. Space X isn't building 30,000 satellites because they're bored. They're building them because the addressable market is large enough to support that scale and because first-mover advantage in this market is worth enormous sums.

The economics of satellite internet are brutal. Launch costs are falling, thanks to Space X's reusable rockets, but constellation operation still requires significant ongoing expense. Satellite operations, ground stations, network management, customer support. A 15,000-satellite constellation probably requires annual operational budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Starlink is currently generating revenue from roughly 3 million subscribers globally. At

But operational costs probably consume a significant portion of that. Profitability in satellite internet is hard. The capital intensity is extreme and the competitive landscape is becoming more crowded.

Space X's expansion strategy is essentially a bet that they can achieve sufficient scale and market dominance to defend margins against competition. It's an aggressive strategy, but the alternative—building a smaller constellation and accepting a niche market—doesn't match Space X's ambitions or Elon Musk's tendencies.

Starlink's acquisition of 50 MHz from EchoStar significantly increases its spectrum capacity compared to the 10 MHz leased from T-Mobile, enhancing its ability to serve more users and reduce reliance on terrestrial carriers.

Timeline and Launch Cadence

Here's a practical question: when will all these satellites actually launch?

Space X launches roughly 22 Starlink missions per month when at full capacity. Each mission typically deploys 50 to 54 satellites. That's roughly 1,200 satellites per month at maximum rate. But that's not sustainable indefinitely. Space X also launches commercial missions, Starshield missions, and other government contracts. Starlink can't monopolize all launch capacity.

A realistic estimate is that Space X launches 8,000 to 10,000 Starlink satellites annually. At that rate, deploying another 7,500 satellites takes roughly 9 to 12 months. Deploying the additional 15,000 mobile-focused satellites takes another 18 to 24 months after that.

So realistically, we're looking at a 3 to 4-year timeline from today to have the full 30,000-satellite constellation operational. That's assuming no major launch failures, no supply chain disruptions, and no regulatory delays.

What could delay it? Launch vehicle availability is the biggest constraint. Space X is rapidly expanding production capacity for Starship, which can carry more satellites per launch than the current Falcon 9. Starship reaching full operational capability would dramatically accelerate deployment. But Starship isn't there yet.

Regulatory delays are possible but seem less likely given the current FCC leadership. Competitive objections and appeals could extend timelines, but the FCC has authority to ultimately override those objections.

The most likely scenario is deployment stretched across the next 4 to 5 years, with full constellation capability achieved by 2029 or 2030.

Geopolitical and Regulatory Context

Space X's satellite expansion doesn't happen in a political vacuum. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr's statements about regulatory harassment and his support for Starlink reflect broader Trump administration policies.

The regulatory environment for space technology became noticeably more permissive starting in late 2024. That's not inherently bad. Permissive regulations can accelerate beneficial innovation. But it also means fewer technical constraints and fewer competitive safeguards.

International dynamics matter too. The US has an interest in US companies dominating space infrastructure. China is building competing capabilities. Europe is discussing sovereign satellite networks. India is getting into the game. Essentially, space is becoming a strategic domain like semiconductors or AI.

Space X benefits from this geopolitical environment. US policymakers see Starlink as a US strategic asset. That translates to regulatory support and potentially government contracts. But it also means Starlink becomes entangled in geopolitics. International tensions could affect service availability.

The bottom line: Space X's expansion has geopolitical dimensions that go beyond pure technology or economics. Understanding the political context helps explain why approval happened so readily and why it might continue to happen readily even if technical objections are raised.

Consumer Impact and Service Implications

If you're considering Starlink service, what does this expansion mean for you?

Short term, not much changes. Starlink's existing constellation already covers most populated areas. If Starlink is available where you are today, more satellites won't dramatically improve service.

Medium term (next 2 to 3 years), you'll likely see improved coverage in remote areas. Capacity constraints in congested areas might ease as network density increases. Performance consistency should improve as the constellation fills out.

Long term (3 to 5 years), Starlink will have competition from Kuiper and other constellations. That will almost certainly drive down prices and improve service quality. The satellite internet market will look very different in 2030 than it does today.

For rural and remote areas currently lacking broadband, this expansion is genuinely important. Satellite internet isn't a perfect solution. Latency, weather sensitivity, and data limits compared to fiber are real downsides. But it's infinitely better than no internet.

For urban areas with terrestrial options, satellite remains a backup option, useful for redundancy but not typically the primary choice. That's unlikely to change even with more satellites.

The biggest impact might be in the developing world where terrestrial infrastructure is limited. Starlink becoming the de facto internet provider in some regions has implications for digital equity, economic development, and sovereignty.

This chart compares the relative capacity, rain fade, and interference of different satellite frequency bands. Higher values indicate greater capacity or more significant challenges. Estimated data based on typical characteristics.

What's Next: The Third Constellation Question

Space X's request for another 15,000 mobile-specific satellites is pending FCC review. If approved, the question becomes how these interact with the existing constellation.

The mobile-specific constellation would use different satellite designs optimized for handheld connectivity. Different antenna patterns, different power systems, different frequency emphasis. Operating alongside the existing broadband constellation, they'd provide complementary capabilities.

FCC approval of the third constellation is not guaranteed, but it's likely given current regulatory momentum. When it happens, Starlink will have the authorization for 30,000 satellites. Operational deployment would follow over the next 4 to 5 years.

That raises a question about sustainability. Can Space X actually operate 30,000 satellites? What does that require in terms of ground infrastructure, software systems, and operational personnel?

The answer is probably yes, but with caveats. Space X has experience with large-scale satellite networks. They've built sophisticated autonomous systems for collision avoidance and network management. The challenge is one of scale, not of fundamentally new capabilities.

But 30,000 satellites is unprecedented. There's no historical precedent for operating a network this size. Space X is pioneering new territory in space operations management.

Space Safety Standards and Industry Best Practices

One aspect that deserves more attention: are there sufficient industry standards for mega-constellation operations?

The ITU (International Telecommunication Union) has guidelines for satellite networks. The FCC has domestic rules. But coordinating standards across a global industry where multiple countries are building competing mega-constellations is complex.

Space X's collision avoidance capabilities are advanced, but there's no universal standard for how different constellations should interact in the same orbital regions. What happens if a Starlink satellite and a Kuiper satellite are on collision course? Whose software decides what maneuver to perform? How do you prioritize between US and international satellites?

These aren't hypothetical questions. They're governance issues that the space industry needs to resolve before mega-constellations become routine.

Some progress is happening. Organizations like the Space Data Association work on standardizing collision avoidance procedures. But progress is slow and regulatory fragmentation is high. The US has different rules than Europe, which has different rules than other countries.

Space X and other operators are essentially operating in a regulatory gray area, following their own best practices without universal standards. That's workable when there's one dominant operator. It becomes problematic when multiple large constellations are operating simultaneously.

The Bigger Picture: Infrastructure and Strategic Importance

Step back from the technical details. What's really happening here?

Space X is building global communications infrastructure. That's historically been the domain of government or heavily regulated corporations. Telephone companies, broadcasters, wireless carriers. All of them operate under significant regulatory oversight.

Space X is different. It's a private company building infrastructure at an unprecedented scale. The regulatory framework for that is still evolving.

The FCC's approval signals that the US government has decided private space infrastructure is acceptable and even desirable. That's a significant policy shift. It comes with both benefits and risks.

Benefits: innovation moves faster under private competition. Costs decline as companies optimize for efficiency. Global coverage becomes possible without requiring government investment. The US maintains strategic dominance in space technology.

Risks: private companies prioritize profit over public interest. Monopolistic behavior becomes possible if one company dominates too completely. Strategic infrastructure becomes dependent on private entities that could change policies, raise prices, or go bankrupt. Geopolitical competition becomes intensified as different countries support their respective space champions.

Neither outcome is predetermined. How Space X wields its dominance matters. How regulators respond to competitive concerns matters. Whether international standards for space operations develop matters.

The FCC's approval of 15,000 satellites is just one step in a longer story about how humanity's orbital infrastructure develops. The technical and regulatory decisions made over the next 3 to 5 years will shape that infrastructure for decades.

Key Lessons and Takeaways

Let's synthesize what you need to know.

First, scale matters. 15,000 satellites sounds like a number, but it represents an unprecedented expansion of orbital infrastructure. This constellation will shape global internet access for the next 20 to 30 years.

Second, regulatory environment changes fast. The shift from skepticism about mega-constellations to approval happened within 2 to 3 years. Policy environments can reverse quickly, but momentum currently favors Space X.

Third, competition is real but delayed. Amazon's Kuiper, Chinese systems, and European alternatives are coming. But Space X's first-mover advantage is substantial. The market will likely support multiple constellations, but Starlink will dominate market share.

Fourth, geopolitics matter. Space infrastructure is strategic infrastructure. Support for Space X expansion reflects US strategic interests. That's not necessarily wrong, but it's a factor in regulatory decisions.

Fifth, technical risks are manageable but not eliminated. Orbital debris, collision avoidance, electromagnetic interference. Space X has addressed these, but 30,000 satellites is new territory. Careful monitoring is warranted.

Sixth, consumer impact is real but unequal. Rural and remote areas benefit significantly. Urban areas with terrestrial options benefit moderately. Pricing and competition will improve for everyone, but satellite isn't a panacea.

FAQ

What exactly are Starlink Gen 2 satellites?

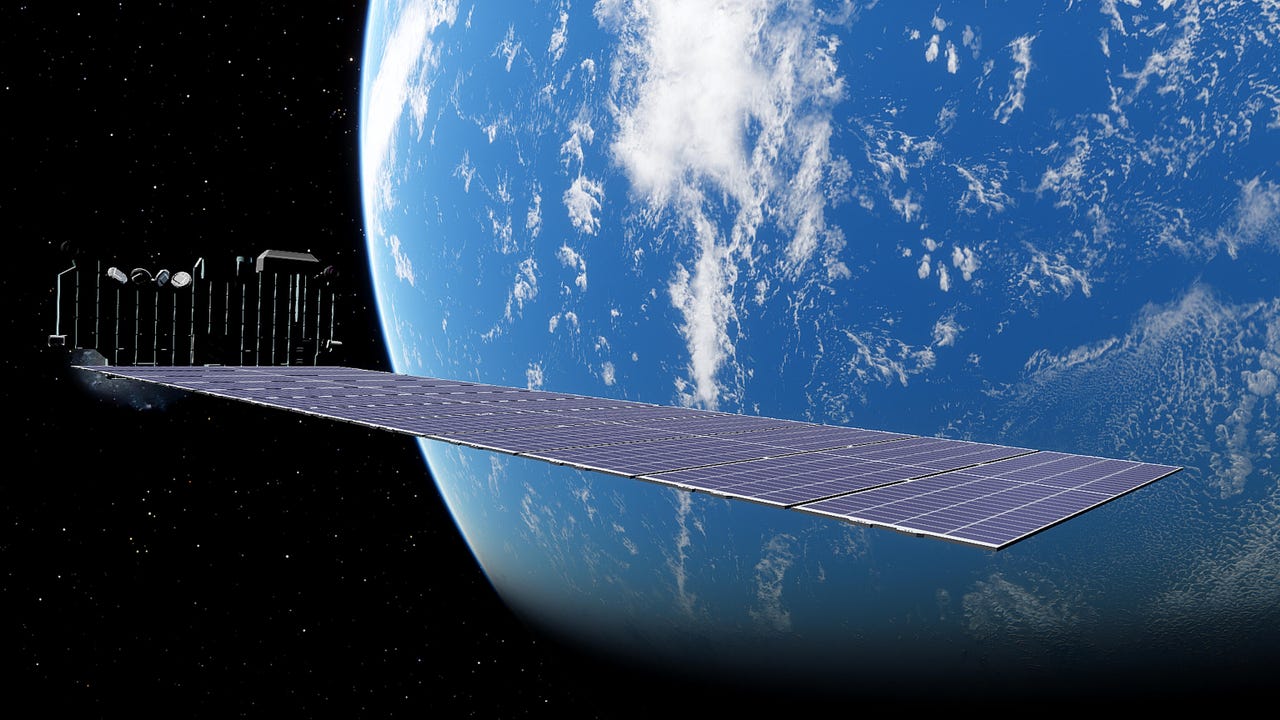

Gen 2 satellites are the second generation of Starlink's design. They're larger, more capable, and more efficient than the original satellites. They support multiple frequency bands simultaneously, enabling better capacity and flexibility. Each satellite weighs around 800 kilograms compared to earlier models, and they can operate across Ku-, Ka-, V-, E-, and W-band frequencies.

How many Starlink satellites are currently in orbit?

As of early 2025, Space X has deployed roughly 6,000 to 6,500 operational Starlink satellites in orbit. The new authorization for 15,000 additional Gen 2 satellites will significantly expand that number. Combined with the pending 15,000 mobile-specific satellites, Space X could have up to 30,000 authorized satellites, though actual deployment will take several years.

What's the difference between fixed service and mobile service from Starlink?

Fixed service means the antenna is stationary, typically on a rooftop or building. Mobile service means the antenna is moving, typically on a vehicle or in someone's hand. Mobile service is technically harder because the antenna must track satellites in motion, power constraints are tighter, and data demands are different. The new authorization extends Starlink's mobile capabilities globally, enabling direct-to-smartphone coverage.

How does Starlink handle collisions and space debris?

Space X uses autonomous collision avoidance systems on every satellite. Satellites detect potential collisions with debris or other satellites and perform automated maneuvers to avoid them. Additionally, Space X is lowering some existing satellites to lower orbits where they naturally decay faster, reducing long-term debris accumulation. The company also performs controlled deorbiting of satellites at end-of-life rather than leaving them as debris.

When will the new satellites launch?

Space X launches roughly 1,000 to 1,200 Starlink satellites annually, though this varies based on other mission priorities. At current rates, deploying the additional 7,500 Gen 2 satellites will take approximately 9 to 12 months. If the 15,000 mobile satellites are approved, the full constellation will take 3 to 4 years to deploy, with full operational capability expected around 2028 to 2030.

Why do other satellite operators oppose Starlink's expansion?

Competitors like Viasat and Globalstar argue that Starlink's dominance prevents fair competition for orbital slots and spectrum resources. With 15,000 authorized satellites, Starlink controls more orbital capacity than all other operators combined. Competitors worry about interference risks, limited access to spectrum, and the ability of smaller operators to compete effectively in this market.

What does the FCC's approval mean for internet access?

The approval enables global broadband coverage, including mobile service directly to smartphones. This has significant implications for rural areas, remote regions, and countries with limited terrestrial infrastructure. It also expands internet access options for maritime, aviation, and emergency services. However, it also means increased dependency on a single provider in regions with limited alternatives.

How much will Starlink service cost as the constellation expands?

Current Starlink pricing ranges from $120 per month for residential broadband to significantly higher rates for business service. As competition increases with Kuiper and other systems coming online, pricing pressure will likely develop. Pricing may decrease as capacity increases and competition intensifies, but Starlink will maintain price premiums for superior performance and coverage in remote areas.

What makes V-band and W-band important for Starlink's new authorization?

These higher frequency bands provide dramatically increased capacity compared to Ku and Ka bands. However, they suffer from greater rain fade and reduced range. By authorizing Starlink to operate across all five bands simultaneously, the FCC enabled dynamic traffic management where demand can be routed to available capacity based on atmospheric conditions and regional demand patterns.

Could Space X's satellite network fail or be abandoned?

Space X has sufficient financial resources and revenue to sustain the network, but catastrophic business failure is technically possible. If the constellation were abandoned, 30,000 non-maneuvering satellites would become a debris problem. This risk exists but is mitigated by Space X's financial position and the network's strategic importance to the US government, which provides some implicit guarantee of continuity.

Conclusion

Space X's FCC approval for 15,000 Gen 2 satellites represents a critical inflection point in global internet infrastructure development. This isn't just a bigger constellation. It's a fundamental shift in how global connectivity might be provisioned.

The technical capabilities are impressive. Multiple frequency bands, global mobile coverage, autonomous operations at scale. Space X has engineered real solutions to genuinely hard problems.

The business strategy is aggressive. With 15,000 authorized satellites already and another 15,000 potentially coming, Space X is betting on dominance. Build scale faster than competitors can respond. Establish lock-in with customers, carriers, and governments. Control the orbital infrastructure that the next generation of internet access depends on.

The regulatory environment enabled this. FCC leadership friendly to Space X, geopolitical factors favoring US space dominance, and arguably insufficient weight given to competitive and safety concerns. That's not necessarily wrong—Space X has genuinely addressed technical concerns and competition will arrive eventually. But it's worth acknowledging.

What happens next?

Watch for the FCC decision on the third constellation. If that gets approved, Starlink's dominance becomes nearly complete. Watch for international responses. China and Europe won't cede space infrastructure to Space X without building alternatives. Watch for competition from Kuiper and others to actually arrive and deliver service. And watch for actual customer experiences as the constellation fills out. Engineering excellence and regulatory approval matter, but real-world performance is what ultimately determines whether this infrastructure achieves its ambitions.

The satellites are launching. The infrastructure is being built. The implications will unfold over the next decade. What you need to know is that this expansion is real, it's unprecedented in scale, and it will reshape global internet access. Whether that's ultimately positive depends on execution, competition, and governance. All three remain to be determined.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX now has authorization for 15,000 Gen2 Starlink satellites with global mobile service capabilities

- FCC approval enables operation across five frequency bands (Ku, Ka, V, E, W) for dynamic capacity management

- Starlink's constellation is 2-3 times larger than all authorized competitors combined, establishing market dominance

- Third constellation (15,000 additional mobile-specific satellites) is pending FCC approval, potentially totaling 30,000 satellites

- Orbital debris concerns were addressed through altitude management, autonomous collision avoidance, and controlled deorbiting strategies

- Deployment timeline extends over 3-4 years with full operational capability expected by 2028-2030

- Competition from Amazon Kuiper, Chinese systems, and others will arrive but with significant time and resource disadvantage

- Global internet access in developing regions and remote areas will be substantially improved by full constellation deployment

![SpaceX's 15,000 Starlink Gen2 Satellites: What It Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-15-000-starlink-gen2-satellites-what-it-means-2025/image-1-1768007259571.jpg)