The Steam Deck's Sudden Sellout: Inside the 2026 RAMaggedon Crisis

Introduction: When Handheld Gaming's Most Anticipated Device Disappears

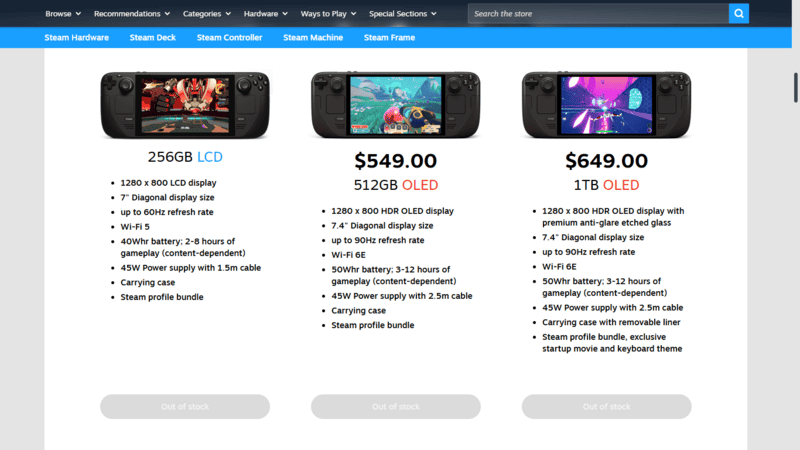

It happened quietly, almost without fanfare. You go to Valve's official Steam store, click on the Steam Deck, and hit an empty shelf. Every single model is gone. The 256GB Steam Deck LCD (being discontinued). The 512GB Steam Deck OLED. The 1TB Steam Deck OLED. All of them, vanished from inventory in early 2026.

On the surface, this looks like good news. Best-seller energy. Demand exceeding supply. The kind of problem every hardware maker dreams about, right? Except it probably isn't.

Just days before this complete sellout, Valve made a shocking announcement about its upcoming Steam Machine, Steam Controller, and Steam Frame. The company admitted something that sent ripples through the tech industry: RAM and storage shortages were forcing them to delay products and likely raise prices. They didn't explicitly blame the Steam Deck's disappearance on these same supply chain issues, but the timing is too perfect to be coincidental.

This is what some people in the industry are calling RAMaggedon. It's not a cute nickname. It describes a very real crisis unfolding in the hardware world right now, one driven by artificial intelligence companies hoarding memory chips to fuel their data centers. And the evidence suggests it might have finally claimed one of gaming's most beloved devices.

So what exactly happened? Why did the Steam Deck vanish? What does RAMaggedon actually mean for your ability to buy a handheld gaming PC? And most importantly, what does this tell us about the future of portable gaming hardware? Let's dig into the details, because this story is more complicated and more consequential than it first appears.

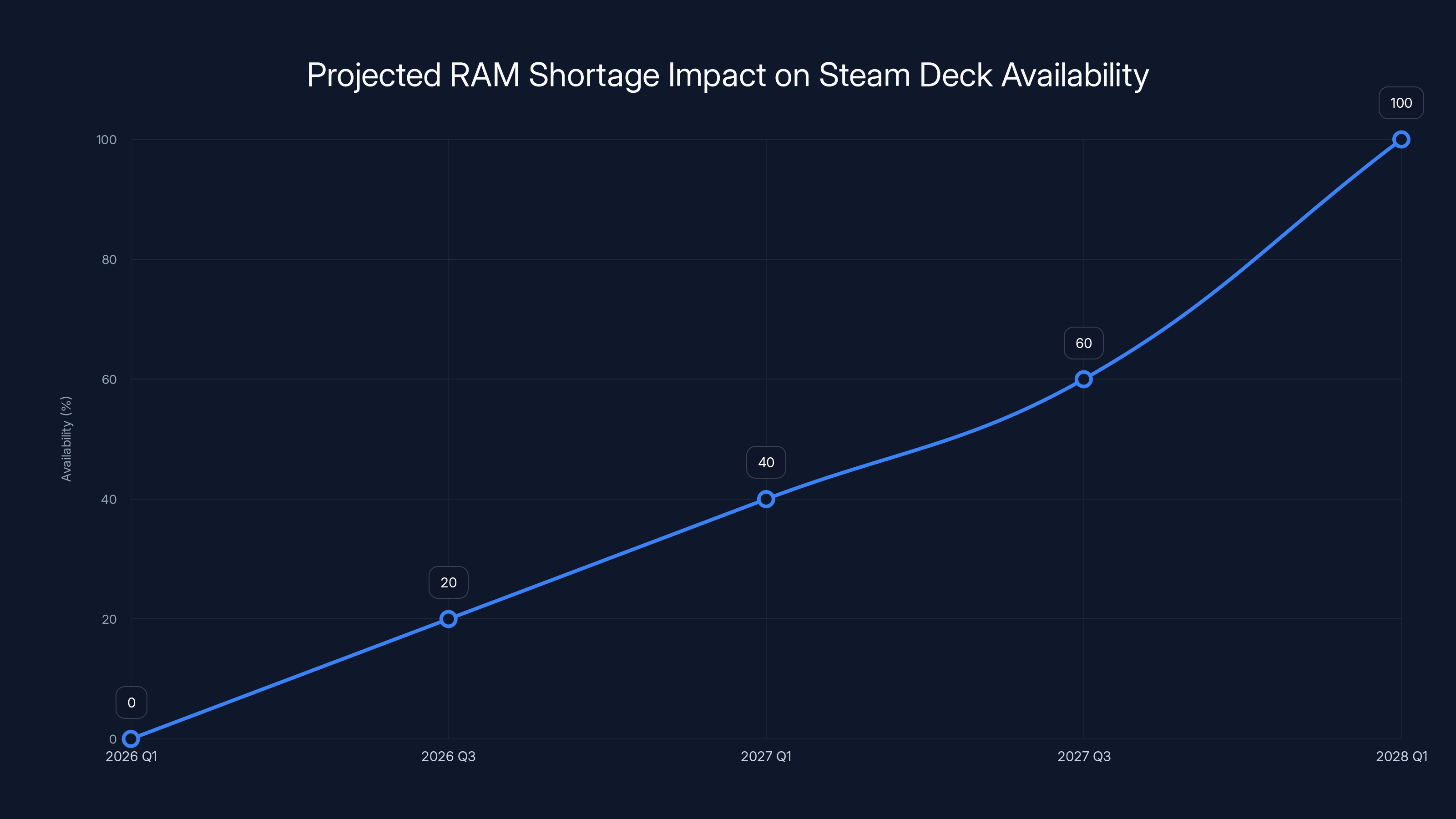

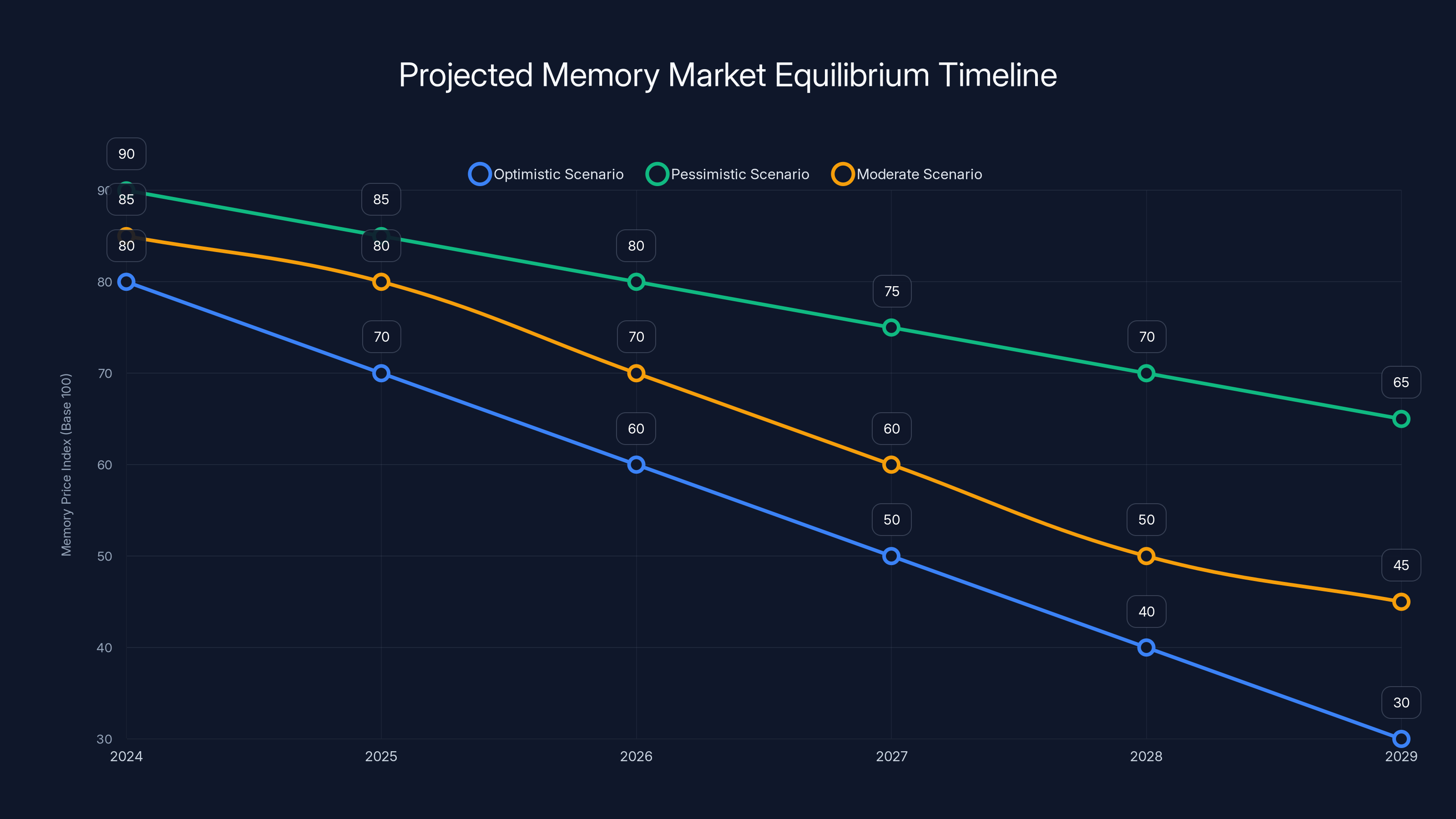

Estimated data suggests that Steam Deck availability may gradually improve from late 2026, reaching full availability by 2028 as memory production capacity expands.

Understanding RAMaggedon: How AI Created a Memory Crisis

RAMaggedon isn't some dramatic overstatement. It's a real market phenomenon driven by concrete economics and genuine supply constraints. Here's what's actually happening.

Artificial intelligence companies, led primarily by Open AI, Anthropic, Google Deep Mind, and various others, are building massive data centers to train and run large language models. These operations require absolutely staggering amounts of memory. We're talking thousands of GPUs, each with its own RAM requirements, multiplied across data centers that span entire facilities.

When you're training models like GPT-4 or running inference at the scale these companies operate, the memory requirements aren't measured in gigabytes. They're measured in terabytes. Your GPU might have 24GB of VRAM. A major AI training cluster needs orders of magnitude more than that, deployed across specialized hardware that consumers never see.

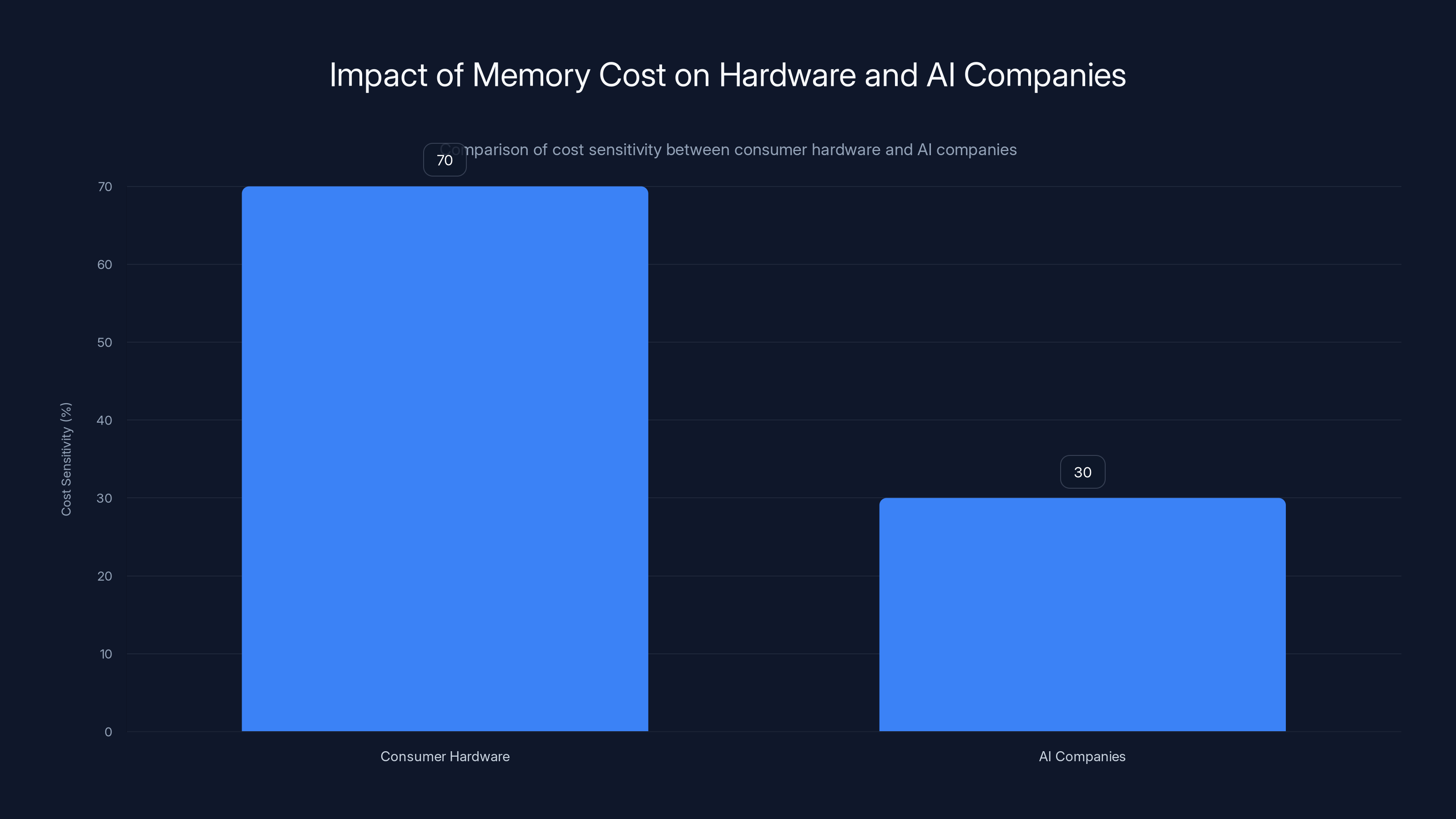

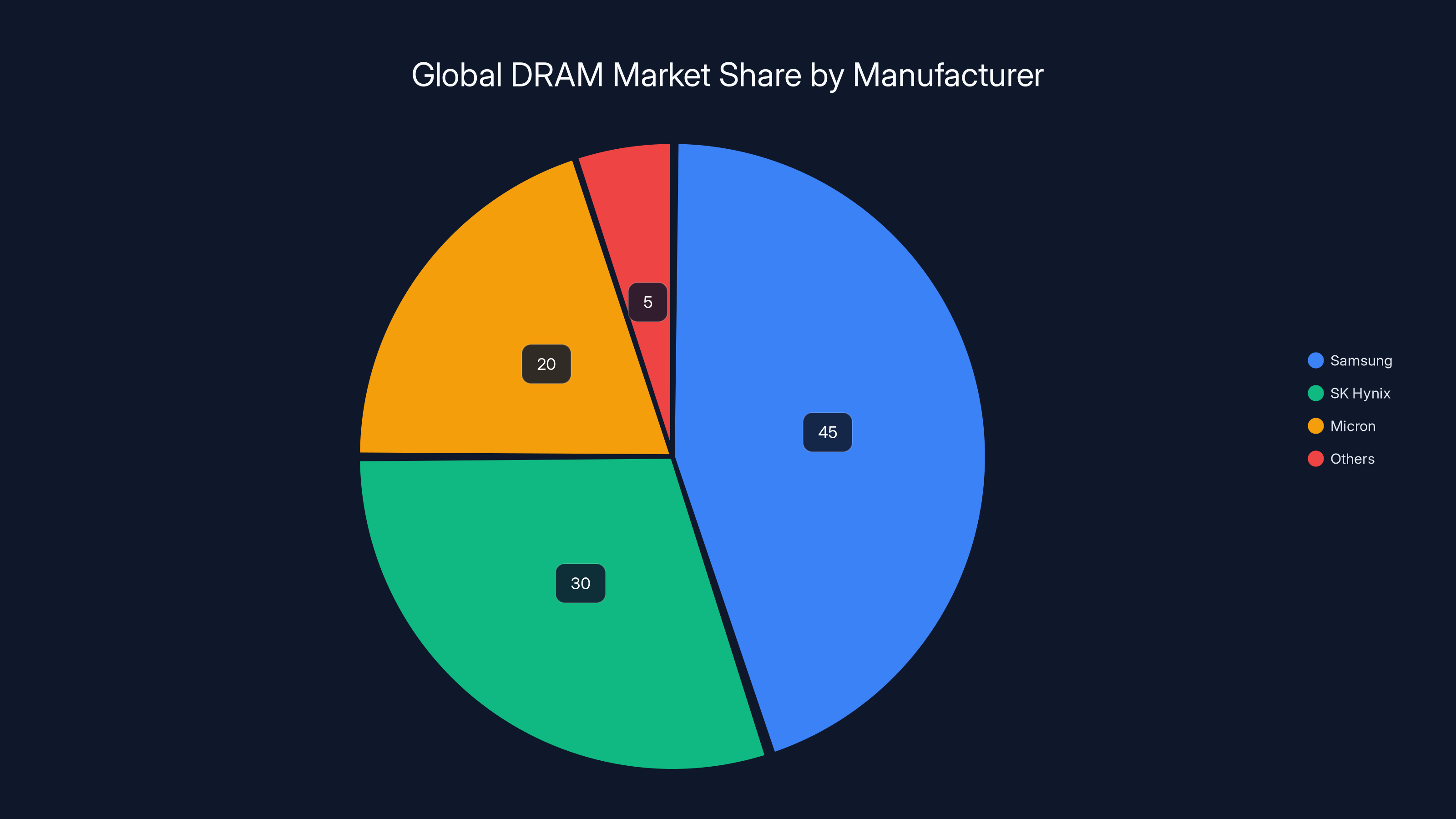

This creates a problem because DRAM (the RAM that powers servers, data centers, and yes, consumer devices) comes from a relatively small number of manufacturers. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron produce the vast majority of the world's RAM. These manufacturers have limited production capacity. They can't instantly build new fabs (fabrication plants). A new memory fab costs upwards of $10 billion and takes years to become operational.

So when AI companies need massive quantities of the latest, fastest memory, they're literally willing to buy entire production runs. They're contracting with manufacturers for guaranteed supply. They're paying premiums to jump the queue. They're doing what any rational actor would do: secure resources before competitors do.

For consumer hardware makers, this is a catastrophe. Suddenly, the memory that would have gone into 10,000 Steam Decks gets redirected to a single AI company's data center expansion. The cost of that memory also skyrockets. What Valve expected to pay

Think of it this way: the global memory market isn't that large. In 2024, DRAM revenue was roughly $30 billion annually. The AI industry, by comparison, is spending tens of billions on infrastructure. When you're acquiring that much hardware that fast, you distort the entire supply chain. Everyone else pays the price.

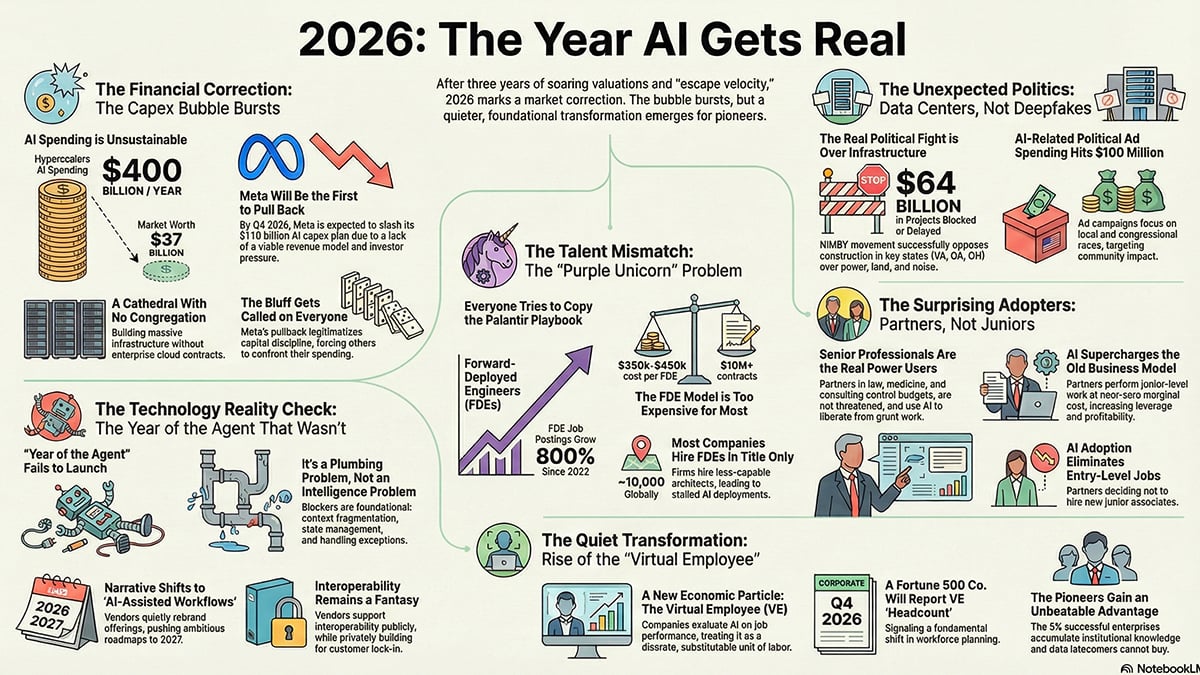

Consumer hardware companies are more sensitive to memory cost increases, impacting their margins significantly, whereas AI companies can absorb these costs due to higher margins and strategic priorities. Estimated data.

The Timeline: How Valve's Hardware Plans Fell Apart

Let's trace exactly what happened with Valve's plans, because the sequence matters.

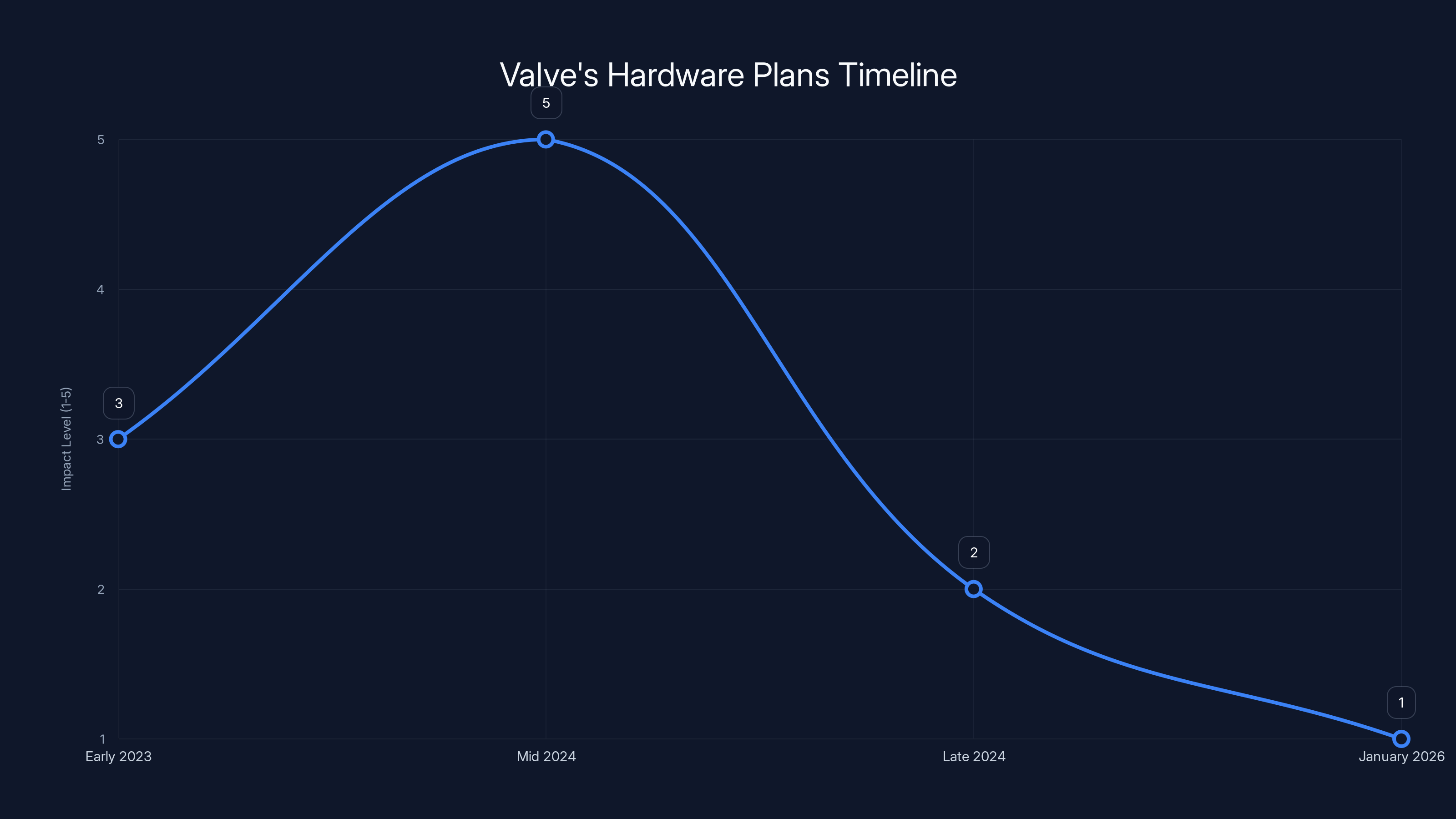

In 2023 and early 2024, Valve was seemingly unconcerned about supply chain issues. The Steam Deck had been a success by most measures. It wasn't setting the world on fire in terms of sales volume compared to something like the Nintendo Switch, but it had proven there was genuine demand for a full-featured PC gaming handheld. Valve was making plans to expand its hardware ecosystem.

By mid-2024, things started shifting. Nvidia and AMD both reported that data center GPU orders were exploding, driven by AI demand. This wasn't secret information. Any hardware analyst paying attention could see that AI companies were on a spending spree that made previous boom cycles look quaint. The AI capex boom was consuming silicon at rates the industry had never seen.

But here's what's interesting: Valve initially seemed to think it would be isolated from this. The company was still talking about the Steam Deck like it would continue on a normal upgrade cycle. OLED screens were rolling out. Performance remained solid. Supply seemed fine. Valve probably assumed that because the Steam Deck runs Linux and uses custom architectures, it would be insulated from the mainstream memory shortages affecting Windows PCs.

That assumption proved naive. Or maybe Valve was simply hoping the RAM situation would resolve itself. A lot of people in tech made that same bet.

By late 2024, the reality became undeniable. In December, Valve announced that it was discontinuing the Steam Deck LCD version. The official story was that the OLED model was superior, so why keep making the older version? But the timing suggests something else was happening behind the scenes. You discontinue your older, cheaper product when your supply chain is constrained. It lets you focus production on the more expensive (and more margin-friendly) OLED units.

Then came the January 2026 announcement about the Steam Machine and other hardware. Valve's statement was carefully worded, but the message was unmistakable: we're delaying new products because we can't secure memory components at prices that make sense. We're also going to have to raise prices because the memory we do secure is much more expensive than we anticipated.

Within days, every Steam Deck model on Valve's store hit out of stock. The 256GB LCD model being gone isn't surprising, since production was ending. But both OLED models vanishing simultaneously is the real signal. That suggests Valve pulled inventory deliberately, either to redirect components toward other projects or simply because they're out of stock and can't replenish at a price point that works.

Frame's price increase provides evidence of where this is heading. Framework, a company making modular laptops, announced in January 2026 that it was raising prices by up to

The question is whether Valve decides to accept lower margins and keep prices stable, or raises Steam Deck prices to maintain profitability. Given that Valve is a private company with no quarterly earnings pressure, they might choose to eat the cost. Or they might wait for the memory market to normalize before resuming significant production. Either way, consumers lose.

The Economics of Memory Shortage: Why AI Wins Every Time

Here's the brutal economic reality that nobody really wants to discuss: AI companies will always win in a memory shortage. The math is simple.

Suppose DRAM costs

Now suppose memory doubles in price to

Meanwhile, an AI company with a $500 million data center expansion needs a certain amount of memory to hit their training timelines and performance targets. They're not sensitive to per-unit cost the way a consumer hardware maker is. They care about total cost and whether the infrastructure generates ROI. If they need to pay 2x for memory to get online six months earlier, that might actually be the optimal choice because six months of inference revenue on a large language model can be worth billions.

This is the fundamental asymmetry. Consumer hardware makers operate on thin margins. A 30% increase in component costs either means raising prices (which kills demand) or shrinking margins (which kills profitability). AI companies operate on fat margins and don't have the same price sensitivity. If you're willing to pay 50% more for components, you get priority in the supplier queue. Consumer products get pushed back.

Add in one more factor: AI companies are often backed by enormous amounts of venture capital and tech giant money. Open AI has backing from Microsoft and others. Google is throwing resources at its own models. Amazon is investing heavily. These companies have deep pockets and can outbid anyone for components.

The result is inevitable. Consumer devices get de-prioritized. Prices rise. Some products get delayed indefinitely. Others never launch at all because the economics no longer work.

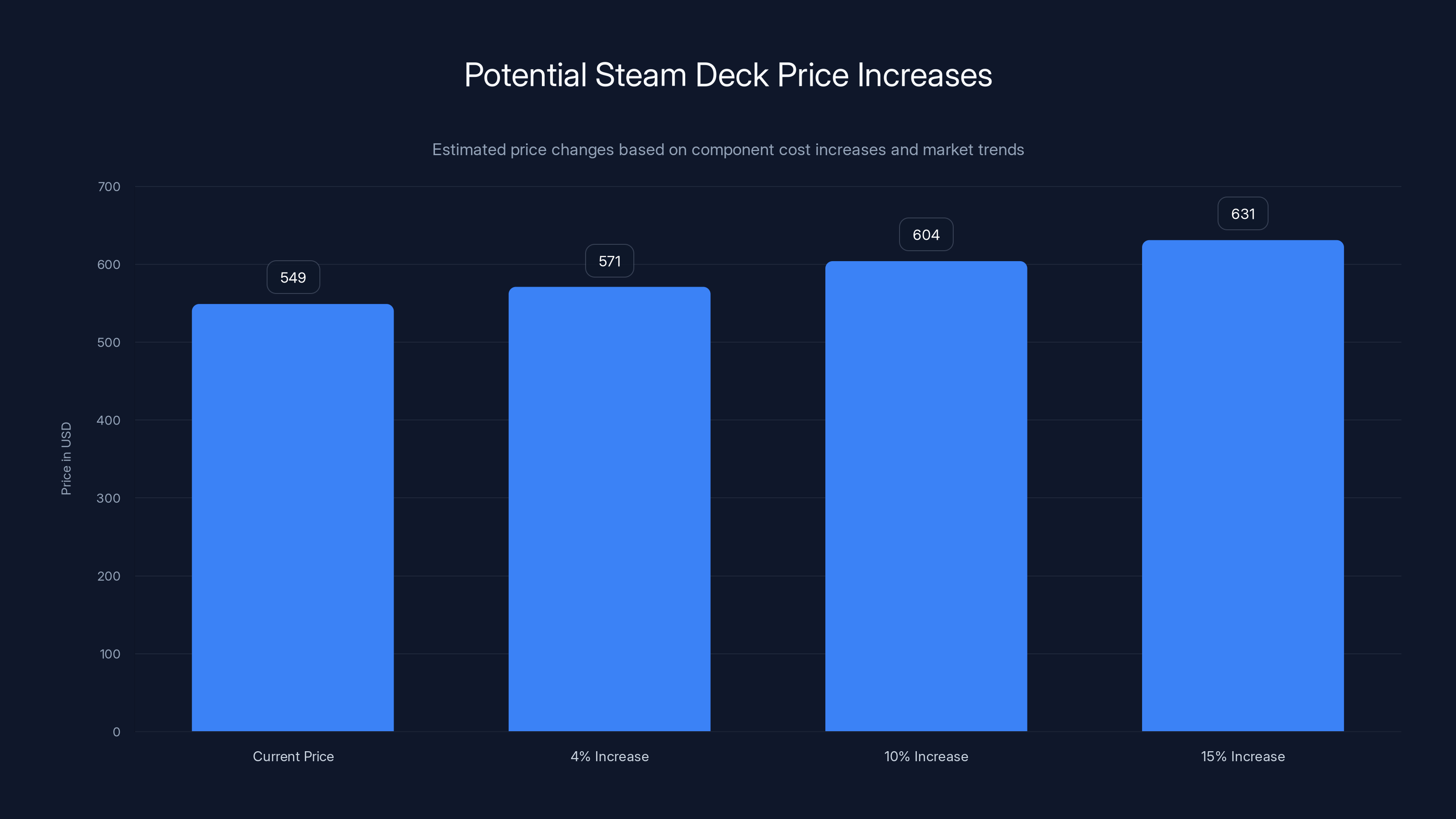

Estimated data suggests a 10-15% price increase for the Steam Deck OLED could raise its price to

Impact on Valve's Hardware Strategy

For Valve specifically, this situation is particularly complicated. Unlike traditional hardware makers that sell millions of units annually, Valve has always been cautious about hardware. The company is famous for its "three" problem (they can't count to three, hence the lack of Half-Life 3, Left 4 Dead 3, Portal 3, etc.). That same risk-averse culture extends to hardware.

The Steam Deck was a calculated bet. Valve believed there was enough demand to justify designing custom silicon, setting up manufacturing partnerships, and building supply chains. Early sales validated that belief, though actual numbers were always kept quiet. But this wasn't a "bet the company" situation. If the Steam Deck failed, Valve's core business (digital game distribution and licensing) would continue fine.

With that context, a prolonged memory shortage might not devastate Valve the way it would devastate, say, Nintendo or Sony. Valve can simply decide that launching the Steam Machine, Steam Controller, and Steam Frame isn't worth the trouble right now. They can pause Steam Deck production until component costs normalize. They can refocus on their core business, which is insanely profitable.

But that's bad news for consumers who were excited about Valve's hardware roadmap. The Steam Machine and Steam Frame both sounded like interesting products. A living room console-style device (Machine) and a modular PC (Frame) could have competed with traditional gaming hardware. But if Valve can't secure memory at reasonable prices, these products don't launch at all.

The bigger question is whether Valve raises Steam Deck prices to compensate for higher component costs. A

The Broader Hardware Industry Collateral Damage

Valve isn't alone. This memory shortage is impacting the entire consumer hardware ecosystem. And it's creating a perverse situation where the people paying the price are regular consumers, while the beneficiaries are a handful of enormous tech companies.

Dell, HP, Lenovo, and other PC makers are all facing the same pressures. Some are already raising prices. Others are reducing configurations or cutting corners on other components to offset memory costs. The consumer experience gets worse while prices go up. That's a brutal combination.

Smaller manufacturers are getting squeezed hardest. Framework's price increase is just the beginning. Any startup or mid-size company that doesn't have the scale or leverage of a Dell or HP is going to struggle. That means less innovation, fewer options, and reduced competition.

Gaming hardware is particularly affected because gaming-focused memory (both DRAM and NAND) has specific performance characteristics that command premium prices. A gaming laptop or handheld that skimps on memory to save costs will feel slow and sluggish. But premium memory is exactly what's scarce.

Mobile phones are facing similar pressures, though not as acute because phone manufacturers have more scale than handheld gaming makers. But even they're facing costs creeping up. Your next phone might be more expensive partly because AI companies consumed the memory intended for consumer electronics.

The timeline shows how Valve's hardware plans were impacted by external factors, with a peak in mid-2024 due to AI-driven demand for GPUs. Estimated data.

When Does the Memory Shortage End?

This is the question everyone's asking. When does RAMaggedon end? When do prices normalize? When can Valve resume normal Steam Deck production?

The honest answer is: nobody really knows. There are optimistic and pessimistic scenarios.

The optimistic scenario assumes that the AI boom is hitting some natural saturation point. Companies have built out the infrastructure they need (for now). Memory prices stabilize. Manufacturers adjust production to meet demand from both AI and consumer sectors. By late 2026 or 2027, supply and demand rebalance. Prices fall back to more reasonable levels. Valve resumes Steam Deck production. Life goes on.

This scenario assumes the current AI capex boom is cyclical, like previous technology boom-bust cycles. And historically, that's often true. During the mobile boom of 2010-2015, everyone was investing heavily. Then the growth slowed, overcapacity emerged, and prices came down. It happened with data centers, with GPU production, with SSD manufacturing. The cycle repeats.

The pessimistic scenario is that AI capex doesn't slow down. Instead, it keeps accelerating. Companies keep expanding data centers. Training runs keep getting bigger. New applications keep emerging that demand even more computation. Memory needs don't plateau—they keep growing. In that scenario, the shortage becomes structural and semi-permanent. Consumer hardware makes do with less, or prices just stay elevated indefinitely.

Some analysts split the difference. They think AI capex will peak sometime in the next 12-18 months, but given the scale of current investments, normalization will take years even after the peak. TSMC, Samsung, and others are building new fabs, but these things take time. By the time new capacity comes online, equilibrium might not arrive until 2028 or 2029.

For Valve and consumers waiting for Steam Deck availability, this ambiguity is paralyzing. Do you wait and hope supply returns and prices fall? Or do you buy now at inflated prices while you can? It's a classic market uncertainty problem, and there's no objectively correct answer.

Historical Precedent: When Shortages Reshape Markets

RAMaggedon isn't unprecedented. The PC industry has faced similar shortages before, and they've always reshaped the competitive landscape in surprising ways.

The most recent major shortage was the NAND flash shortage of 2017-2018. SSD prices skyrocketed because memory manufacturers couldn't keep up with demand. The result? Some manufacturers used cheaper, slower NAND in their drives. Others raised prices. Traditional hard drive makers suddenly became competitive again because SSDs got expensive. Some consumers bought HDDs instead. The entire storage market reorganized around the shortage.

When that shortage ended, the dynamics shifted back, but not entirely. The manufacturers who had adapted and survived gained market share. The ones who made bad choices during the shortage never fully recovered.

Similarly, the GPU shortage during the crypto boom of 2020-2021 reshaped the gaming GPU market. Gamers couldn't buy graphics cards. Prices went absurd. Some people switched to consoles. Others upgraded their CPUs and integrated graphics instead. AMD and Nvidia had to ration cards to gamers versus miners. The shortage ended, but it altered consumer behavior and company strategies in ways that persisted.

RAMaggedon could reshape the handheld gaming market similarly. If the shortage persists, consumers might accept lower-spec devices. They might buy Nintendo Switch instead of waiting for Steam Deck availability. Some might go back to phones for casual gaming. The market adjusts. When supply returns, those consumer preferences don't instantly revert.

For Valve, the real risk isn't the current shortage. It's that during this shortage, competitors grab market share that Valve can't reclaim later. Nintendo's next handheld will launch without supply constraints (because Nintendo has the scale and supply chain relationships). It'll be cheaper than a Steam Deck with higher memory costs. Consumers will buy it. Even when Steam Deck supply normalizes, some of those customers are locked into the Nintendo ecosystem.

Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron dominate the DRAM market, collectively holding 95% of the share. Estimated data.

The Price Question: Will Steam Deck Get More Expensive?

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: price. If Valve resumes Steam Deck production, will they raise prices?

The framework precedent suggests yes, at least in some form. Framework raised prices up to $460 across its product line. For laptops, that might be 20-30% increases in some configurations. That's substantial.

Valve has a few options:

First, they could raise prices proportionally to their component cost increases. If memory costs increased 40-50% and memory is 10% of total hardware cost, that's a 4-5% price increase to maintain margins. But if memory cost increases are combined with general supply chain inflation, the total increase could be 10-15%. A

Second, Valve could maintain current pricing and accept lower margins. Valve is private and profitable, so this is technically feasible. This would be a strategic choice to maintain market position and customer goodwill. Consumers would appreciate it, but investors (if Valve ever goes public) would hate it.

Third, Valve could reduce specifications while maintaining price. They could offer 256GB as the base model instead of 512GB. They could use slower memory. They could downgrade the display. This is essentially what happened with the Steam Deck LCD to OLED transition, though that was technically an upgrade. But the precedent exists—Valve is willing to iterate on specs in response to market conditions.

Fourth, Valve could discontinue the Steam Deck entirely and focus on future products. This seems least likely given the investment Valve's already made, but it's theoretically possible. If making Steam Decks unprofitable at any price point, Valve might just exit the market.

My best guess? Valve probably raises prices 10-15% when they resume production, but tries to keep increases modest to avoid killing demand. They might also introduce a new baseline configuration (maybe a 256GB OLED) at a lower price point to capture price-sensitive customers.

The Steam Machine and Steam Frame: Delayed Indefinitely?

Valve's other hardware announcements deserve separate analysis because the economics work differently for different product categories.

The Steam Machine was supposed to be a console-style device for living rooms. Think of it as a powerful PC shrunk into a small form factor, running Steam OS, and optimized for couch gaming. The appeal was obvious: you get a real gaming device that connects to your TV, without the hassle of building a PC or buying a console.

But here's the problem: consoles are typically sold at a loss or minimal profit, with revenue coming from games and services. Sony and Microsoft have mastered this model. Valve's expertise is software (Steam) and game licensing, not hardware manufacturing at scale. A Steam Machine would need to be competitive with Play Station 5 and Xbox Series X on price. At current memory costs, that's incredibly difficult to achieve profitably.

Steam Frame was supposed to be a modular gaming PC where you could upgrade components over time. Framework proved there's demand for modularity and repairability. But again, modularity is expensive. It requires additional engineering, precise tolerances, and higher manufacturing costs per unit.

Both products seem like they're on indefinite hold. Valve's statement said they were "delaying" these devices due to supply chain and pricing issues, but that's probably diplomatic language for "we're not going to launch these at all unless the market conditions improve dramatically."

The cynical interpretation is that Valve used these announcements as cover for discontinuing the LCD Steam Deck. By talking about exciting new products that are temporarily delayed, Valve looked forward-thinking rather than retreating. But the reality might be that Valve is consolidating around the Steam Deck OLED and pausing new hardware expansion until better times.

Estimated data suggests that memory prices may stabilize by 2026-2029, with optimistic scenarios predicting earlier normalization. Estimated data.

What Happens to Steam Deck Users Right Now?

For people who already own a Steam Deck, this situation is... fine? The shortage doesn't affect existing devices. Your Steam Deck works exactly the same as it did before. Game compatibility continues improving. Valve keeps pushing software updates. The software ecosystem is actually in better shape now than it was two years ago.

The pain is for people wanting to buy a Steam Deck. If you've been thinking about picking one up, you can't. Not through Valve's official store, anyway. Third-party sellers on Amazon and eBay have inventory, but expect to pay premiums—sometimes 10-20% over MSRP. That's the secondary market arbitraging the shortage.

There's also the question of warranty and support. Buy from an authorized retailer, you get Valve's warranty and support. Buy from a third-party seller, you get whatever that seller offers, which might be nothing. For a device like this, that's a meaningful risk.

For people who were specifically waiting for Steam Machine or Steam Frame, the news is worse. Those products might not launch for years, if ever. That's a product roadmap gone.

The Bigger Picture: When Hardware Can't Keep Up With Software

RAMaggedon highlights a deeper problem in the tech industry: software and hardware development are increasingly misaligned.

Software is infinite and scalable. You can update a billion phones with a single software release. You can train a larger language model with the same hardware by just running it longer. Software scales to match the resources available.

Hardware is finite and constrained by physics and manufacturing capacity. You can't make memory chips faster than semiconductor physics allows. You can't build fabs overnight. You can't expand manufacturing capacity infinitely.

When AI companies demand vast quantities of memory to power their software (large language models), they're creating a physical constraint that propagates through the entire industry. Smaller companies and consumer products bear the brunt because they have less leverage.

This creates a structural problem. As AI becomes more important economically, it will consume more resources. It will get priority in the supply chain. Other industries and products will become secondary. We're going to see more RAMageddon-type situations with other materials and components.

The solution requires either: (A) AI companies use resources more efficiently, (B) manufacturing capacity increases dramatically, or (C) a combination of both. Right now, we're seeing some of both happening—companies are researching more efficient training methods, and manufacturers are expanding capacity—but it's slow.

Valve's situation is just the most visible symptom of a larger market reorganization where AI gets priority and consumer hardware gets the leftovers.

Recovery Timeline: The Realistic Outlook

Let me give you my best guess about timing, with the caveat that anyone claiming certainty about supply chains is overconfident.

Q2 2026 (near term): Steam Deck remains out of stock through Valve's store. Secondary market prices elevated. Valve makes no announcements about resumption dates because they don't have visibility into their memory supply.

Q3-Q4 2026 (medium term): Memory prices stabilize but remain elevated. Valve might resume limited production at higher price points. Expect $599+ for the base OLED model. New product launches (Machine, Frame) remain paused.

2027 (long term): New memory manufacturing capacity starts coming online (TSMC, Samsung, SK Hynix are all expanding). Prices trend downward but don't collapse. Valve might reduce prices slightly or maintain them. New products might get announced but won't launch immediately.

2028 (recovery): Market starts normalizing. Supply roughly matches demand. Prices fall to pre-shortage levels. Valve might finally launch new hardware if they choose to.

This is one plausible timeline. There are others. If AI capex keeps accelerating, everything gets pushed back by 12-24 months. If there's a recession, memory prices collapse faster. If there's a new geopolitical crisis affecting semiconductor fabs, everything gets worse.

The key assumption is that the AI boom eventually moderates. History suggests technology booms do moderate. But this one is unprecedented in scale and intensity, so historical precedent might not apply.

What This Means for Handheld Gaming's Future

Beyond the immediate Steam Deck situation, RAMaggedon has implications for the entire handheld gaming market.

Nintendo's next handheld will launch during this shortage. Nintendo has more manufacturing scale and leverage than Valve, so they'll get the memory they need. Their device will be cheaper than a current-gen Steam Deck (Nintendo's devices usually are). If the next Nintendo handheld is

Phones will continue to be viable gaming devices because phone makers have massive scale and are willing to pay premium prices for memory. A flagship phone has multiple gigabytes of RAM and might cost as much as a gaming PC, but consumers buy phones regardless. Gaming becomes a feature, not a primary purpose.

Purpose-built handhelds like Steam Deck exist in a weird middle ground. They're expensive enough that consumers expect them to be readily available. But they're not as scale-able as phones or traditional consoles. They're hit hardest by supply constraints.

The longer-term implication is that dedicated handheld gaming devices might become less viable as consumer products. If RAMaggedon-type shortages become regular occurrences (which they might, given ongoing AI expansion), companies might stop investing in these devices. Why launch a new handheld if you can't guarantee supply?

Valve built the Steam Deck as a premium product for enthusiasts willing to wait and accept some rough edges. If supply becomes unpredictable, even enthusiasts get frustrated. The product positioning becomes untenable.

The Regulatory Question: Should Governments Intervene?

Here's a question nobody's really asking yet, but probably should be: should governments intervene in component shortages?

Memory and storage chips are fundamental infrastructure now. They're as important to modern economies as steel, oil, and electricity were to previous eras. When one industry (AI) can monopsonize supply to the point where consumer devices can't be manufactured, that seems like a legitimate policy concern.

The U. S. government invested heavily in semiconductor manufacturing through the CHIPS Act, partly to address supply chain vulnerabilities. But that's a long-term infrastructure play, not a short-term solution to ongoing shortages.

Some economists argue for temporary restrictions on memory exports or allocations to ensure consumer hardware manufacturers maintain access. Others argue that's market intervention that would backfire. If the U. S. restricted memory sales to AI companies, those companies would just buy from other countries, and the global shortage would persist.

It's a genuine policy dilemma, and I don't see governments tackling it directly yet. They're focused on the long-term semiconductor infrastructure problem, not the immediate shortage dynamics.

For Valve and consumer hardware makers, government intervention isn't coming. They have to navigate RAMaggedon through market forces and their own supply chain management.

Conclusion: The New Normal for Hardware

The Steam Deck's vanishing from Valve's online store is a small event with large implications. It signals that the easy era of abundant, cheap hardware components is ending. We're entering a period where hardware makers will face regular supply constraints driven by competing industries' demands.

Valve built the Steam Deck as a premium handheld gaming device during relatively stable supply chain conditions. It was an impressive technical achievement, and it proved that consumers want full-featured gaming on portable hardware. But its launch occurred during a narrow window of opportunity that might have already closed.

If and when Valve resumes Steam Deck production, it'll likely be a different product: more expensive, possibly with reduced specifications, definitely with longer lead times and unpredictable availability. That's the new normal in hardware manufacturing, where artificial intelligence and other high-value applications can outbid consumer products for scarce resources.

For consumers, the immediate takeaway is simple: if you want a Steam Deck, you might need to wait months or pay secondary market premiums. For Valve, the question is whether it remains committed to hardware or pulls back and focuses on Steam (the software platform) where it has unique advantages. For the broader industry, RAMaggedon is a wake-up call that component shortages aren't temporary disruptions but potentially structural features of how hardware will be manufactured going forward.

The steam deck's fate over the next 12-24 months will tell us a lot about whether we're in a temporary crisis or a fundamental shift in how hardware gets made and distributed. And that shift, in turn, will reshape what devices get built and who gets to build them.

FAQ

What is RAMaggedon?

RAMaggedon refers to a severe shortage of RAM and DRAM components driven by artificial intelligence companies acquiring massive quantities of memory for data centers and training infrastructure. The shortage has created global supply constraints that impact consumer hardware manufacturers, driving up component costs and reducing product availability across the industry.

Why is the Steam Deck completely out of stock?

Valve's Steam Deck vanished from the company's online store in early 2026 as a direct result of the RAMaggedon memory shortage. Valve cannot secure sufficient memory components at prices that make manufacturing profitable, forcing the company to pause production. This directly impacts the Steam Deck's availability since the device requires significant memory for both storage and performance.

How is the AI industry causing the RAM shortage?

Large language model companies require enormous quantities of high-performance memory to build and operate data centers. Companies like Open AI and Anthropic are acquiring entire production runs of DRAM from manufacturers like Samsung and SK Hynix. Because manufacturing capacity is limited and takes years to expand, consumer hardware makers are pushed to the back of the queue and face dramatically elevated prices for the memory they can obtain.

When will the Steam Deck be back in stock?

There's no official timeline for Steam Deck availability. Based on current market trends, limited production might resume in mid-to-late 2026 at elevated price points, with more normal availability potentially arriving in 2027 or 2028 depending on how quickly memory manufacturing capacity expands and AI component demand moderates.

Will the Steam Deck get more expensive if Valve resumes production?

It's likely. Framework, a modular laptop manufacturer, raised prices up to

What about the Steam Machine and Steam Frame?

Both devices are indefinitely delayed due to supply chain and memory cost constraints. Valve announced these products in January 2026 but immediately cited supply issues as preventing launch. These products might never launch if memory remains expensive, as the economics for new hardware platforms become increasingly difficult to justify in a high-component-cost environment.

How does this shortage affect PC gaming more broadly?

All PC makers face similar pressures. Dell, HP, and others are raising prices, reducing configurations, or absorbing costs with thinner margins. Gaming laptops and high-end systems are hit harder because gamers specifically demand high-memory configurations. Smaller manufacturers lack the leverage to negotiate favorable component prices, reducing innovation and competition in the handheld and budget segments.

Should I buy a Steam Deck right now from secondary sellers?

It depends on your patience and budget. Official Valve pricing ($549 for OLED) is unavailable. Secondary sellers charge premiums, sometimes 10-20% above MSRP. You get no warranty coverage from Valve when buying third-party. If you want a Steam Deck urgently and can afford the premium, secondary markets are your only option. Otherwise, waiting might be wiser unless you expect significant price increases when Valve resumes official sales.

How long do technology component shortages typically last?

Historical precedent suggests 12-24 months from peak shortage to relative normalization, though full recovery takes longer. The 2017-2018 SSD shortage lasted roughly 18 months. The 2020-2021 GPU shortage stretched nearly two years. RAMaggedon appears to be more structural and could persist longer unless AI capex moderates significantly or manufacturing capacity expands faster than currently anticipated.

Could this shortage reshape the handheld gaming market permanently?

Yes. If Steam Deck unavailability persists, Nintendo's next handheld will launch with guaranteed availability and lower pricing. Consumers will buy Nintendo instead. Market share shifts become difficult to recover. Additionally, companies might reduce investment in dedicated handheld platforms if supply becomes unpredictable. Purpose-built gaming devices could become less viable as consumer products if RAMaggedon-type shortages become regular occurrences driven by competing industries' component demands.

Key Takeaways

- Steam Deck is completely out of stock due to RAM shortages driven by AI companies acquiring massive memory quantities for data centers

- RAMaggedon is structurally reshaping hardware markets as AI infrastructure demands outbid consumer devices for limited components

- Memory costs have increased 40-50%, forcing companies like Framework to raise prices substantially and Valve to pause production

- Recovery likely takes 12-24 months minimum, with normal availability possibly not arriving until 2027-2028 depending on AI capex moderation

- Upcoming hardware like Steam Machine and Steam Frame are indefinitely delayed, while Nintendo's next handheld will launch during the shortage with supply advantages

Related Articles

- Steam Machine 2026: Complete Guide to Valve's Living Room Console [2025]

- Nintendo Switch: The Console That Changed Gaming Forever [2025]

- StreamFast SSD Technology: The Future of Storage Without FTL [2025]

- Ayaneo Next 2 Handheld: Premium Gaming PC Price & Specs [2025]

- Best Gaming Laptops 2025: Top Picks for Every Budget

- PlayStation Portal: The PS5 Accessory That Changed Gaming in 2025

![Steam Deck Out of Stock 2026: What RAMaggedon Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/steam-deck-out-of-stock-2026-what-ramaggedon-means-2025/image-1-1770845776454.jpg)